Abstract

The current report provides an updated review of sleep disturbance in posttraumatic stress disorder and anxiety-related disorders. First, this review provides a summary description of the unique and overlapping clinical characteristics and physiological features of sleep disturbance in specific DSM anxiety-related disorders. Second, this review presents evidence of a bidirectional relationship between sleep disturbance and anxiety-related disorders, and provides a model to explain this relationship by integrating research on psychological and neurocognitive processes with a current understanding of neurobiological pathways. A heuristic neurobiological framework for understanding the bidirectional relationship between abnormalities in sleep and anxiety-related brain pathways is presented. Directions for future research are suggested.

Subject terms: Psychology, Neuroscience

Introduction

Sleep is a vital physiological process, disruptions of which affect performance in multiple domains of functioning [1], including but not restricted to cognitive [2, 3], emotional [4], metabolic [5], and immunologic [6]. Focusing on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other anxiety-related disorders specifically, published research points to a bidirectional relationship between disturbances in sleep and anxiety-related disorders. Neurobiological research ranging from animal research to human neuroimaging and polysomnography-based research, alongside clinical treatment research, provide insights about this relationship, while also highlighting questions that remain to be answered. A heuristic neurobiological framework for this relationship is proposed to contribute to ongoing research in this area.

The study of sleep–wake regulation and the neurobiology of sleep disturbance in humans: an introductory overview

Both human and basic animal research have driven a surge in our understanding of sleep neurobiology in recent decades. In the 1950’s and 1960’s, researchers coined the terms REM and NREM sleep (REMS, NREMS) after observing that humans cycled through periods of sleep with unique electroencephalography (EEG) signatures combined with distinct eye movement patterns and muscle activity levels [7–9]. Since then, the field of sleep research has started to unravel the significance of sleep and its different visually scored stages (NREM N1, N2, N3, and REMS) for various essential functions, including but not limited to synaptic homeostasis [10, 11], cognitive function [2, 12], emotion regulation [4], memory processing and consolidation [10, 13–15], glucose metabolism [5], immunity [6], and more [1]. Since the mid-20th century as well, numerous studies have also established that circadian and homeostatic processes regulate sleep in humans [16, 17]. Although understanding the functional neuroanatomy of sleep regulation in humans is still impeded by the challenges of imaging the human brain during sleep, animal research has greatly advanced our grasp of sleep/wake neurocircuitry in mammals, and in combination with pharmacological, EEG, and imaging studies in humans, provides clues regarding the relevance of different brain nuclei and circuits in human sleep.

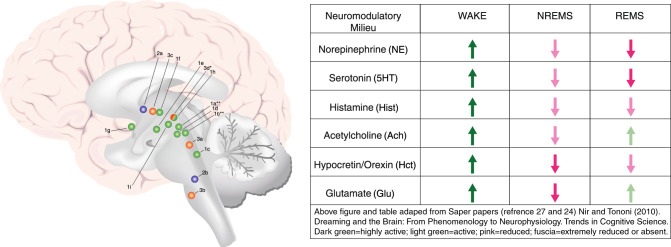

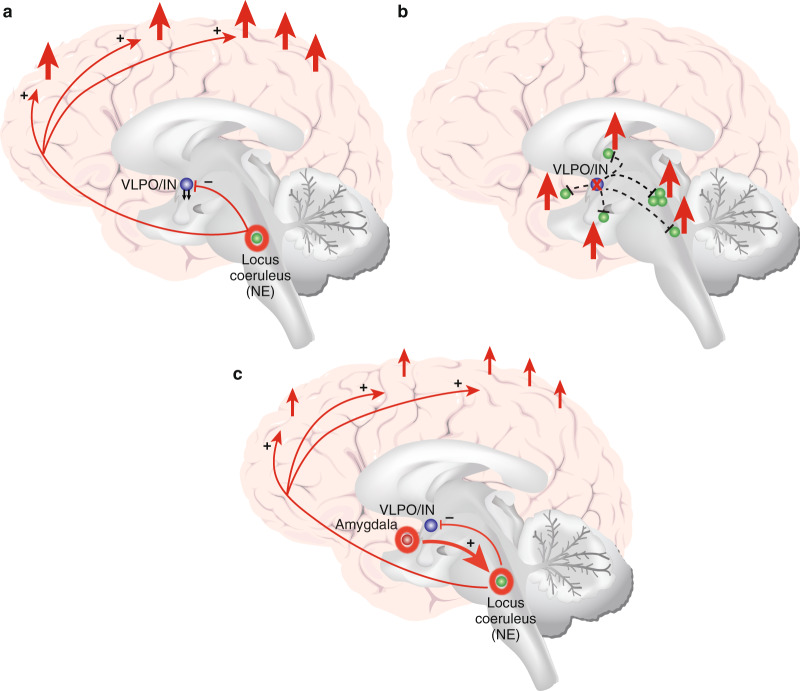

The existing research points to distinct nuclei and brain regions with prominent and preferential roles in promoting NREMS (which includes slow-wave sleep (SWS/N3 sleep), REMS, and the wake state. Although the most-recent evidence challenges the relative simplicity of sleep/wake neurocircuitry models developed in recent decades (e.g., see [18]), the extant research strongly indicates that specific brain regions and cell types are preferentially active in NREMS, REMS, and/or the wake state, and that these nuclei and cell types influence each other via positive and negative feedback mechanisms in the service of regulating sleep and wake. Figure 1 depicts a current understanding of important brain nuclei involved in NREMS, REMS, and wake regulation. Mutually inhibitory network interactions between NREMS promoting neurons in the ventrolateral preoptic area (VLPO in rodent model; intermediate nucleus (IN) in humans) and wake-promoting neurons in the brainstem and hypothalamus regulate sleep–wake rhythms in a fashion analogous to the engineering concept of a flip–flop switch [19–23]. This model was recently updated to emphasize the importance of fast neurotransmitters, glutamate and GABA [24]. In addition to the VLPO, GABAergic neurons in the medullary parafacial zone (PZ) are also critical for slow-wave sleep (SWS) homeostasis, shown by anatomic, electrophysiologic, chemogenetic and optogenetic studies in mice [25, 26]. For example, lesions in GABAergic neurons in PZ increased wakefulness by 50% and severely disrupted sleep, including a marked reduction of SWS [25]. Brain regions specifically or preferentially active during REMS have also been identified (Fig. 1). Of critical importance in the context of a discussion of anxiety disorders is that arousal/wake centers also broadly innervate the cerebral cortex, and the cerebral cortex reciprocally innervates arousal centers [24, 27]. This means that in the context of salient information to the cortex, for example from the amygdala, arousal may be elicited despite competing sleep-promoting signals from sleep-specific centers of the brain.

Fig. 1.

Important wake, NREM sleep, and REM sleep-regulating brain structures and/or nuclei, and associated neuromodulatory milieus. Wake-promoting regions, in green 1a–i; NREMS (including SWS) promoting regions in blue 2a–b; REM sleep-regulating regions in orange (3a–d). Wake (green): 1a: lateraldorsal tegmentum (LDT; Ach); 1b: pedunculopontine tegmentum (PPT; Ach); 1c: locus coeruleus (LC; NE); 1d: dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN; 5HT); 1e: tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN; Hist); 1f: hypocretin neurons of Lateral Hypothalamus (LH; Hct); 1g: cholinergic neurons of basal forebrain (BF; Ach); 1h: ventrolateral periaqueductal gray (vlPAG; DA); 1i: ventral tegmental area (VTA, DA). NREMS (blue): 2a: ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO; GABA, galanin; human homolog: intermediate nucleus (IN)); 2b: parafacial zone (PZ; GABA). REMS (orange): 3a: sublaterodorsal tegmental nucleus (SDT; Glu); 3b: ventral gigantocellular reticular nuclei (mediate REM-related muscle atonia; GABA/glycine); 3c: MCH neurons of lateral hypothalamus (LH; MCH/GABA); 3d: ventrolateral periaqueductal gray (vlPAG; GABA), *which is REM-suppressing. **LDT and PPT Ach neurons are also active during and may promote REMS, but may not play a central regulatory role

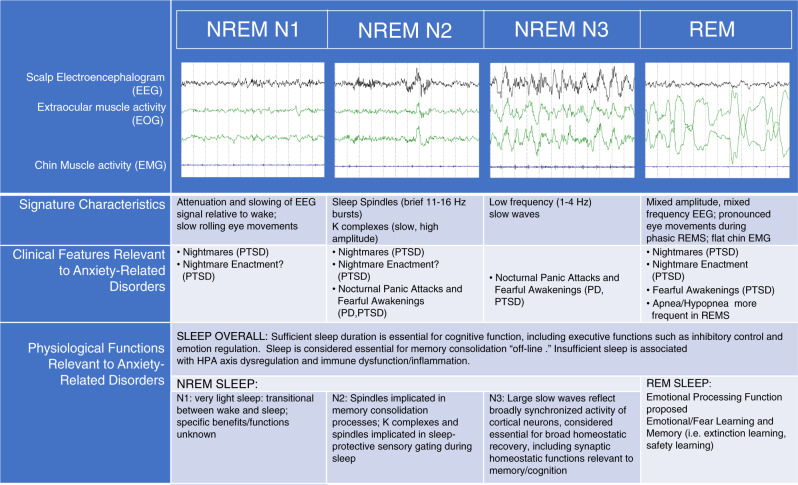

With respect to the study of sleep in psychiatric disorders, scalp-EEG-based measurement of cortical physiology remains the most-commonly utilized tool for studying the neurophysiology of sleep disturbance. Some researchers have also successfully probed the deeper functional neuroanatomy of human sleep disturbance in anxiety-related disorders utilizing neuroimaging techniques [28–30], but such studies are still relatively few. Figure 2 depicts the polysomnographic characteristics associated with different stages of sleep, along with a list of their associated clinical features and proposed or evidence-based functions, selected for their pertinence to anxiety disorders. Anxiety-disorder-related findings that will be discussed in greater detail in the following sections include reductions in sleep duration and sleep continuity, reductions in SWS, increases in lighter stages of sleep (NREM N1 and/or N2), and a variety of abnormalities in REMS, including disrupted REMS in anxiety subjects relative to controls. Based on the proposed functions of these various stages of sleep, one can infer numerous neurocognitive and psychological consequences relevant to anxiety, including disturbances in cognitive control, emotion regulation, memory consolidation, and emotional memory processing.

Fig. 2.

Polysomnographic characteristics of different sleep stages in humans, along with a list of their associated clinical features and proposed or evidence-based functions selected for their pertinence to anxiety disorders. Some studies have studied the effects of sleep overall (especially sleep duration) on performance in various domains, such as executive cognitive function and emotion regulation, whereas other studies have examined the role of specific sleep stages on performance of various functions more specifically

Neurobiology of anxiety-related disorders: a brief overview of neurocircuitry

An overview of the neurobiology of anxiety-related disorders must begin with a definition of these disorders. Given the ever-changing landscape of DSM-defined anxiety disorders, and given that all mental disorders may contain or produce a pronounced anxiety component (take paranoid schizophrenia, for example, in which patients may experience core psychotic symptoms resulting in profound and debilitating anxiety), we refer here to anxiety-related disorders as disorders in which fear and/or anxiety are considered primary and core features of the disorder. As such, we limit our detailed review of sleep disturbance to PTSD, Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Panic Disorder (PD), Social Phobia (SP), and Specific Phobias (SP). We also include obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) owing to its recent (DSM-IV) categorization as an anxiety disorder, because there are significant anxiety components to this disorder, and because we believe this will be of interest to readers.

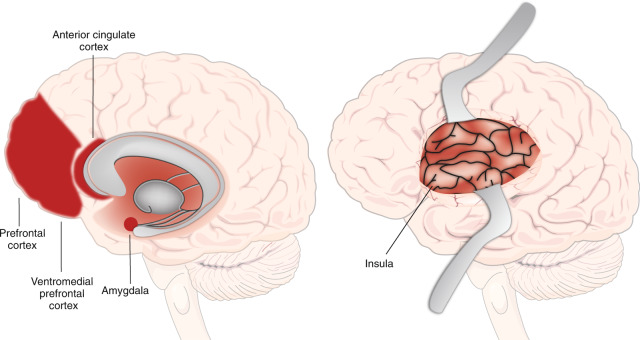

With these definitions in mind, neuroimaging research in humans has provided relatively greater insight (relative to sleep disturbance in humans) into the functional neuroanatomy and neurocircuitry of anxiety-related disorders [31–35]. Figure 3 depicts the main brain regions broadly implicated in anxiety-related disorders. The amygdala and insula, key structures involved in the processing of aversive stimuli and in the expression of fear and anxiety, most consistently display hyperactivation in (aversive) task-based neuroimaging studies of anxiety-related disorders (see Duval et al., [34] for a review including disorders of interest minus OCD). In contrast, the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) tends to display hypoactivation in anxiety-related disorders, especially PTSD and GAD, and treatment of anxiety-related disorders has been associated with increases in mPFC activation that relate to symptom improvement [34]. In addition, the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), with some exceptions, shows increased activation in anxiety-related disorders, which is thought to reflect the role of dACC in processing and expression of fear and anxiety. In contrast, the rostral ACC (rACC) is proposed to have a fear-modulating role based on neuroimaging findings. Functional connectivity studies in anxiety-related disorders generally indicate decreased connectivity between regions that modulate negative emotions (mPFC/rACC) and emotion-processing regions (amygdala, insula).

Fig. 3.

Important brain regions involved in fear, threat, and anxiety expression and modulation. Neuroimaging research indicates that the amygdala and insula are involved in the expression of fear, threat and anxiety. The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) is more involved in the processing and expression of anxiety and fear, whereas the rostral ACC (rACC) is more involved in their modulation. The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is involved in their modulation, especially the ventromedial PFC (vmPFC)

Other regions are considered to be relevant to anxiety-related disorders, some of which are less well understood or are associated with less consistent or broadly generalizable findings [34]. For example, the hippocampus is considered to play an emotion-modulating role in fear and anxiety, and often shows hyperactivation in imaging studies of anxiety-related disorders. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), implicated in emotion modulation and attention control, has shown patterns of hyper- and hypoactivation in anxiety-related disorders. Finally, the thalamus has been shown to display excess activation in task-based neuroimaging studies in PTSD, Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD), and SD relative to controls. The thalamus is also a key structure involved in the generation of SWS as well as the downregulation of sensory processing during sleep.

Anxiety and sleep circuitry: partially overlapping, intercommunicating neurocircuits

Although we describe two distinct sets of brain regions implicated in sleep/wake regulation and anxiety states, there is clear evidence of interaction between them, the extent and details of which are only beginning to be uncovered. There are obvious ways in which these communicate, including the aforementioned tight connection between the arousal centers and the cerebral cortex. This shared broad connectivity with the cerebral cortex provides a concrete neurobiological pathway for interconnectivity, but also provides an anatomical context for the cognitive hyperarousal that may link anxiety to sleep disturbance. In addition, the locus coeruleus, the main generator of norepinephrine in the central nervous system, plays both an important role in sleep/wake regulation as well as in anxiety-related processes through its inputs to and from the amygdala as well as the cerebral cortex. We will return to these neurobiological pathways later. A closer look at the clinical and sleep-physiological findings pertaining to the disorders of interest will create a phenomenological background for a subsequent discussion of these neurobiological pathways.

Sleep disturbance in anxiety-related disorders: a review of clinical features

The term “sleep disturbance” in published research on sleep and anxiety-related disorders refers to a range of subjective complaints, sleep disorder diagnoses, and alterations in subjective and objective measures of sleep when clinical samples are compared with controls. Several types of clinical sleep disturbance stand out in this literature; including DSM insomnia disorder diagnoses or symptoms per se, more broadly defined disturbances in subjective sleep quality as measured using various self-report surveys, nightmares, fearful awakenings, nocturnal panic attacks, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and abnormal movements during sleep ranging from periodic limb movements to dream enactment behaviors. Certain types of sleep disturbance are more common across anxiety-related disorders (e.g., insomnia and/or broadly defined subjective sleep quality disturbances [36–40] than others (e.g., nightmares) and individuals with anxiety-related disorders often experience more than one type of sleep disturbance. A recent comprehensive publication by Cox and Olatunji provides a highly informative review of sleep disturbance in anxiety-related disorders and the clinical features are given relatively brief review here, where we focus on elements that are less emphasized in that review [41].

Clinical features of sleep disturbance: PTSD

Subjective sleep disturbance is highly comorbid with PTSD and is often considered a “hallmark” feature of the disorder [42, 43]. Subjective sleep disturbance and recurrent nightmares are listed as diagnostic criteria with prevalence rates as high as 90% [36, 44–46]. It is therefore rare to encounter a patient with clinically significant non-sleep symptoms of PTSD who does not also report non-restorative and/or disrupted sleep, or distressing dreams. Sleep disturbance in PTSD may also be the most well-studied as compared with sleep disturbance in other anxiety-related disorders, and therefore may provide the best clues for understanding the sleep–anxiety relationship [41].

Although comorbid insomnia symptoms and poor subjective sleep quality are pervasive features of PTSD, nightmares stand out as a particularly unique feature of this disorder. Prevalence rates for nightmares vary widely, ranging from 19 to 96% [39, 47, 48], however ample research indicates that the prevalence of nightmares is significantly higher in individuals with PTSD than the general population [45, 49] and other psychiatric conditions [47, 48, 50, 51]. The wide range is likely attributable to differences in data collection methods, differences in study sample characteristics, and differences in trauma nightmare definitions. For example, most research uses retrospective measures, which are likely to underestimate nightmare frequency compared with prospective log assessments [52]. In addition, the definition of trauma nightmares has changed with various iterations of the DSM and varies widely across studies. Research has demonstrated higher rates of trauma nightmares in females compared with males [53, 54] and nightmares may be more frequent in the context of recent trauma compared with chronic PTSD [55].

In addition to the highly prevalent disturbances of insomnia and nightmares, it is now well-established that other sleep disturbances also occur following trauma and/or in PTSD [56–60]. For example, several studies have indicated that panicked awakenings from sleep with poor or no recall of dream content are common in PTSD [59]. Several studies have also reported increases in physical movement during sleep when compared with controls, including periodic leg movements [59] (although see Woodward et al. [61] reporting decreased movement in PTSD sleep). Nightmare enactment is also commonly reported in clinical practice, although prevalence rates are poorly established. Nightmare enactment has typically been observed in younger individuals and is more common immediately following trauma. However, most studies have been conducted in combat veterans, for whom age and time since trauma are difficult to disentangle (e.g., military personnel are exposed at a young age), and thus warrants study in other populations.

Based on the unique combination of sleep symptoms following trauma, Mysliwiec et al. [57, 62] have proposed a new disorder, “trauma-associated sleep disorder”. The proposed disorder encompasses disruptive nocturnal behaviors such as thrashing movements panic-like, or startled awakenings, and dream enactment that are proposed to occur out of both REM and NREM sleep. Further research is necessary to determine whether these sleep symptoms represent an early and severe form of sleep response to trauma that later evolves into the more typically described sleep presentation (e.g., insomnia and nightmares), or whether this trajectory is distinct, and possibly even related to neurodegenerative risk. For example, dream enactment is well-described in REM Behavior Disorder (RBD) and is considered a prodromal marker of Parkinson’s Disease. It remains to be seen whether dream enactment following trauma is unique or is related to the dream enactment characteristic of RBD.

Clinical features of sleep disturbance: GAD

GAD is the other anxiety-related disorder whose DSM diagnostic criteria specifically include sleep disturbance [46]. Despite the inclusion of sleep disturbance in the nosological definition, empirical investigations of sleep disturbance in GAD are relatively limited. Nonetheless, existing published research fairly consistently indicates that subjects with GAD report worse subjective sleep than healthy controls [41]. Sleep disturbance has been reported in up to 75% of individuals with GAD [63, 64]. Adults with GAD report poorer subjective sleep quality [65–67] and have been found to be more likely to have a sleep disorder (vaguely defined, as per chart review) when compared with control groups [68].

Clinical features of sleep disturbance: PD

The extant research has demonstrated that subjective sleep complaints are common in PD, with controlled studies indicating greater difficulties with sleep initiation, sleep maintenance, early morning awakenings and more general sleep quality disturbances in PD subjects than healthy controls [41, 69–73].

A PD-specific sleep disturbance that may overlap with panicked awakenings seen in PTSD are nocturnal panic attacks. Nocturnal panic attacks are characterized by abrupt awakenings from sleep with panic attack symptoms [74]. These can be distinguished from sleep terrors, which are a parasomnia involving severe autonomic arousal and fearful behavior during NREM sleep, and which are generally not recalled subsequently [75]. Although epidemiological studies have not been conducted, survey data indicate that lifetime prevalence rates for at least one nocturnal panic attack in individuals with PD are as high as 71% [74, 76–79]. Based on one report with a small sample, it appears that nocturnal panic attacks in PD emerge during the transition from lighter to deeper NREM sleep, either in visually scored N2 preceded by EEG slowing (indicating a transition to deeper sleep) or in early N3 sleep [80]. There is some evidence to suggest that individuals with PD and nocturnal panic suffer from higher rates of depression [80] and suicidality [81] compared with individuals with PD without nocturnal panic. Individuals with nocturnal panic may also suffer from more-frequent daytime panic attacks and greater somatic symptoms during daytime attacks [76]. These findings have led researchers to postulate that nocturnal panic attacks may represent a more severe variant of PD.

Clinical features of sleep disturbance: specific phobia and SAD

Limited research exists examining sleep disturbance in phobias and SAD [41]. To summarize, two studies using community samples found that the presence of phobias and SAD was associated with increased likelihood of having sleep disturbances, as measured by the PSQI [40] and WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WHO CIDI) [82].

Clinical features of sleep disturbance: OCD

Several studies have examined subjective sleep disturbance in adults with OCD. One study found no differences in sleep parameters when comparing an OCD and controls [83]. The second study found greater subjective reports of sleep disorders and poorer subjective sleep quality in individuals with OCD compared with healthy controls [84]. Similar to other anxiety-related disorders, greater OCD symptom severity may be associated with greater sleep disturbance severity; a cross-sectional study demonstrated that short sleep duration predicted OCD in a Korean community sample (Park et al. [85]) and another cross-sectional study found that greater OCD symptom severity was associated with shorter sleep duration and decreased sleep efficiency in 13 adults with an OCD diagnosis [86]. Conversely, Marcks et al. [87] failed to find an association between OCD diagnosis and sleep disturbance in a sample of primary care patients. In a nationally representative sample, Cox and Olatunji [41] found that individuals reporting insomnia symptoms reported increased OCD symptoms relative to those who did not.

Obstructive sleep apnea

Recently, there has been a growing interest in the relationship between OSA and anxiety-related disorders, particularly PTSD. OSA is a sleep disorder characterized by repeated upper airway obstruction during sleep, leading to breathing interruptions and sleep fragmentation [88]. The underlying pathophysiology of OSA is multifactorial and complex and may vary considerably across individuals. Important components of OSA pathophysiology include upper airway anatomy, the ability of upper airway dilator muscles to respond to respiratory challenges during sleep, arousal thresholds during sleep, the stability of the respiratory control system, and state-related changes in lung volume [89, 90]. Major risk factors for OSA include obesity, older age, male sex, smoking, and use of central nervous system depressants (e.g., alcohol). The apnea hypopnea index (AHI) is the number of apneas or hypopneas recorded per hour of sleep. The AHI is often used as a diagnostic tool and is a marker of OSA severity.

OSA prevalence rates appear to be higher in PTSD samples compared with the general population [91–99]. Greater PTSD symptom severity increases the risk of screening positive for OSA [91]. On the other hand, including both veteran and non-veteran studies, prevalence rates of OSA in PTSD vary considerably [92, 100–105]. Differences may result from differences in diagnostic criteria and sample characteristics such as sample size, sex, age, ethnicity, and health status compositions. It is also important to note that some studies generated prevalence estimates from samples specifically recruited for OSA-high-risk features (e.g., sleep disturbance), which is likely to artificially inflate prevalence estimates.

There is insufficient evidence to conclude that OSA rates in non-PTSD anxiety disorders differ relative to controls. One cross-sectional study using data from outpatient records of the Veteran Health Administration found that an OSA diagnosis increased the odds of having an anxiety disorder diagnosis in veterans [106]. With respect to PD, the majority of work elucidating associations between PD and OSA has been limited to case studies [107–109], studies with small sample sizes [110, 111], and studies without an appropriate control group [111]. To our knowledge, only one study has examined OSA prevalence rates in PD and GAD; this study was conducted in a community sample of OSA-high-risk participants and reported an OSA prevalence rate of 58.8% in PD and 57.1% in GAD [112]. Another study demonstrated that individuals with PD demonstrated significantly greater rates of microapneas during sleep than controls [110].

In summary, although high rates of OSA are reported in PTSD, these are not convincingly demonstrated in other anxiety-related disorders, and the mechanism explaining the relationship between OSA and PTSD remains to be clarified [98]. The increasingly high rates of obesity in veterans [113] and people with PTSD [114] may be a major factor contributing to this surge in OSA prevalence.

Physiological and functional neuroanatomical features of sleep disturbance in anxiety-related disorders

A number of polysomnography (PSG) studies along with a few neuroimaging studies have begun to identify physiological and functional neuroanatomical features that may underly the subjective complaints of sleep disturbance in anxiety-related disorders. We focus here on polysomnography-based studies, and also include a brief presentation of neuroimaging and neuroendocrine research. Of note, we do not discuss actigraphy-based findings in detail here, and instead focus on direct measures of physiology during sleep in anxiety disorders. Overall, actigraphy-based findings demonstrate objective sleep abnormalities in anxiety-related disorders, although there are inconsistencies in results within and across disorders [41, 84].

Sleep physiological findings: PTSD

Several studies, including two meta-analyses, now provide convincing evidence of PSG-measured sleep abnormalities in PTSD [41, 115, 116]. In a meta-analysis incorporating 20 studies, Kobayashi and colleagues found that PTSD was associated with more stage N1 percent, and lower SWS percent as compared with a mix of controls, including healthy subjects, trauma-exposed, or non-exposed [116]. Authors of a more-recent meta-analysis, which only incorporated 13 studies owing to more-restrictive inclusion criteria, and which incorporated new studies not reviewed by Kobayashi et al., also reported less SWS duration in PTSD as compared with a mix of controls [115]. The latter study found no differences in N1 or N2 sleep duration. On the other hand, they report that PTSD was associated with a reduction in PSG sleep continuity as compared with controls, as defined by a composite measure including sleep latency, sleep efficiency, and/or number of awakenings [115].

Needless to say, the above meta-analyses were performed in the context of inconsistencies in the literature. Some clinical studies observed no differences in PSG-based sleep measures in PTSD vs. control groups (all trauma exposed) [99, 117], whereas other studies have found reduced SWS, increased stage 1 sleep, reduced sleep efficiency, reduced sleep duration, and/or greater number of awakenings in PTSD relative to trauma-exposed [118] or healthy and depressed controls [119]. Inconsistencies have been attributed to moderating third variables such as age, sex [116, 120], comorbid diagnoses, and substance use disorders [116]. For example, the Kobayashi et al. meta-analysis also found an effect of PTSD on total sleep time (shorter in PTSD) in studies with male samples only. Finally, laboratory-based studies of PTSD subjects suggest that PTSD subjects may in fact sleep better in the supervised environment of the sleep laboratory. This may obfuscate differences in objective sleep quality in PTSD relative to controls.

In terms of REM sleep, both of the above-cited meta-analyses reported that PTSD was associated with greater REM density (REMD), an index of eye movements during REM sleep, than controls [115, 116]. The implications of REMD are not entirely clear, although some research indicates that REMD is an indicator of phasic hyperarousal during sleep. Interruptions or fragmentation of REMS have also been reported in PTSD and/or trauma survivors relative to controls [56, 121, 122], including PTSD-positive vs. PTSD-negative veterans [56], and PTSD-positive vs. normal healthy civilians [121]. In a subsample of a representative community-based sample Breslau et al. reported that more frequent arousals from REMS was associated with a history of lifetime PTSD [122]. Mellman and colleagues [123] have also found that REMS fragmentation in the early aftermath of trauma predicted subsequent development of PTSD symptoms. Complicating the REM/PTSD story, Mellman et al. [124] also reported that duration of PTSD was associated with higher REM percent, longer REM duration, and shorter REM latency. Mellman et al. [124] suggested that the linear association between REM parameters and the course of PTSD may reflect an adaptive process in chronic patients, as REM sleep is implicated in emotional processing. On the other hand, Ross suggests that this “reconstituted” REM sleep in chronic PTSD is actually pathological [125]. Richards et al. found longer duration of REMS in PTSD relative to exposed controls in women only [120]. Studies in animal models have fairly consistently demonstrated alterations in REMS in rodent models of acute and chronic stress, which may be relevant across anxiety-related disorders, but these have included both disruptions and prolongations of REMS. Altogether, these findings provoke ongoing interest in REMS but limited definitive conclusions about patterns of disturbance [126–131].

Although few neuroimaging studies have been performed to understand sleep disturbance in anxiety-related disorders, a number of studies have been conducted in PTSD. For example, Germain and colleagues [132] performed FDG PET imaging in military veterans with and without PTSD and found hypermetabolism in both wake and REM sleep in PTSD-positive, relative to PTSD-negative subjects, in regions involved in emotion expression and emotion regulation. These included the mPFC, the (right) amygdala, and hippocampus as well as brainstem regions overlapping with the raphe nuclei and (right) locus coeruleus. They also saw elevated activity in the thalamus in PTSD relative to controls. In another study, Germain and colleagues reported hyperactivity in NREMS in PTSD relative to control subjects, as well as increased elevation in NREMS relative to wake, in PTSD more than controls [29]. Although these reports indicate hyperarousal of both cortical and subcortical brain regions during sleep, other studies contribute to a more complex story with less straightforward interpretation [30, 133, 134].

Other approaches have been utilized to examine the evidence for physiological hyperarousal during sleep in PTSD by measuring peripheral indicators of neuroendocrine activity. Indices of hyperarousal such as nighttime excretion of norepinephrine metabolites and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity have indeed been associated sleep disturbance in PTSD [135–138].

Sleep physiological findings: GAD

Studies examining physiological sleep characteristics in GAD are limited and therefore it is difficult to draw conclusions [41]. Nonetheless, PSG-based differences in GAD vs. controls are reported. compared with control groups, individuals with GAD exhibit decreased sleep duration [139, 140], increased sleep onset latency [139], increased wake after sleep onset and reduced sleep efficiency [140], reduced NREM N2 sleep and reduced SWS [140]. Two studies found no differences in objective sleep efficiency between GAD and controls [139, 141]. A separate study found that individuals with GAD exhibit increased REM latency compared with individuals without GAD [141].

Sleep physiological findings: PD

Objective reports of PSG sleep abnormalities in PD are less clear. Some studies have found that individuals with PD exhibit decreased sleep efficiency [80, 142–144], increased onset latency [80, 142, 143], and reduced sleep duration [78, 80] compared with controls. Another study found no differences in PSG measures of sleep disturbance, despite subjective differences in sleep quality across a PD and control group [73]. A recent meta-analysis based on four studies concluded that PD is associated with poorer sleep efficiency and marginally significant longer sleep onset latency when compared with individuals without PD [115].

An older and small body of research exists examining sleep physiological characteristics in PD [41]. The existing literature has demonstrated decreased REM latency [142, 145], decreased number of REM periods [80], decreased REM density [145], increased stage 1% [146], decreased stage 2 duration [143], and deceased SWS % [78, 144]. Contrarily, Dube et al. [147] found no differences in sleep physiology when comparing PD to healthy controls.

Sleep physiological findings in OCD

A small number of studies have found differences in NREM sleep parameters in individuals with OCD compared with healthy controls [41]. More specifically, studies have reported decreased sleep duration [148, 149], reduced sleep efficiency [149, 150], and greater number of nocturnal and early morning awakenings [148–150] in individuals with OCD compared with healthy controls. Studies also indicate increased N1 sleep [148], decreased N2 sleep [148], and decreased SWS [148, 151] in individuals with OCD. There is also evidence of altered REM parameters in OCD, though results are mixed. Some studies have demonstrated reduced REM latency [148], higher REM density in the first REM period [149], and a trend towards reduced REM efficiency (p = 0.06; [148]) in individuals with OCD. In contrast, other studies have found no differences in REM parameters between OCD and control groups [86, 150]. A recent meta-analysis that combined data from PSG, self-report and observer reports found that sleep duration was also reduced in OCD relative to healthy controls [152].

Summary of Sleep Physiological Findings

In summary, published sleep-physiological studies overall indicate hyperarousal during sleep in anxiety disorders, with effects on sleep architecture and continuity that may impact some important functions of sleep. It is possible that publication bias has reduced the number of negative published results, favoring publications detecting differences between anxiety disorders and controls. On the flip-side, the generalized but subtle pattern of disruption may indicate that measuring hyperarousal during sleep is more complex than current methods are able to discern, and more sophisticated methods of measurement and analysis such as quantitative EEG analysis [120, 153–155] and brain imaging during sleep [156] are indicated.

Evidence for a bidirectional relationship between sleep disturbance and anxiety-related disorders

Most studies demonstrating high levels of sleep disturbance in anxiety-related disorders are cross-sectional, therefore the causal relationship between sleep disturbance and anxiety-related disorders cannot be discerned. However, a number of studies strongly indicate that sleep disturbance enhances risk for future anxiety-related disorders, especially PTSD, and there is also empirical evidence from human studies demonstrating that that anxiety-related disturbances can precede and increase risk for sleep disturbances. We briefly review studies indicating this bidirectional relationship here.

Prospective studies have convincingly demonstrated that sleep disturbance both prior to and following trauma is an important predictor of subsequent PTSD development [117, 157, 158]. Van Liempt and colleagues [159] found that nightmares, although not insomnia symptoms, prior to military deployment predicted PTSD subsequent to deployment. Furthermore, treatment research indicates that treatment of insomnia using standard cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) results in an improvement in daytime PTSD symptoms [160, 161], indicating that insomnia may be a driver of PTSD symptoms, which, when treated, results in a diminution of PTSD symptoms. A recent meta-analysis by Hertenstein et al. [162] also demonstrated that insomnia symptoms prospectively predicted anxiety symptoms in the short-term (12–24 months) and long-term (>24 months). In the other direction, Wright et al., cited above, found that PTSD symptoms 4 months after trauma did not predict insomnia symptoms at 12 months. In contrast, an interesting recent study used ecological momentary assessments of PTSD and insomnia symptoms and demonstrated that daytime anxiety predicted (temporally preceded) poorer sleep quality and efficiency, even when controlling for baseline PTSD symptoms [163]. This study also found that daytime PTSD symptoms and fear of sleep predicted subsequent nightmares. Findings from a large community-based sample of adolescents also showed that having any anxiety disorder was prospectively associated with an increased risk of insomnia [164]. In that study, insomnia did not predict the future development of anxiety disorder. Although our review is mostly focused on sleep and anxiety in adults, research in children and adolescents, when these disorders first present, may be particularly informative with respect to the chicken-and-egg question.

To our knowledge, studies that prospectively examine the relationship between sleep and non-PTSD anxiety disorders is limited. As described above, in a study in adolescents aged 13–17, anxiety disorder predicted future insomnia, whereas insomnia did not predict future anxiety [164]. One prospective study utilizing self-report measures found that sleep disturbance was associated with anxiety symptoms (though not GAD specifically) or a diagnosis of PD 4 years later [165]. CBT for GAD reduces sleep disturbance symptoms, but one study demonstrated that 33% of individuals had an insomnia disorder diagnosis and 63% had clinically significant sleep disturbance following treatment, indicating that insomnia is not a result of GAD alone, and/or that insomnia that may have resulted from GAD has taken on a life of its own, and is therefore unresponsive to GAD treatment. Several laboratory studies using total sleep deprivation paradigms have demonstrated that sleep deprivation increases the vulnerability to subsequent daytime panic attacks [166, 167]. It is not clear how these experimental results generalize to sleep disruption in the real world. Additional work has demonstrated that sleep disturbance symptoms persist following successful PD treatment [168, 169], which suggests that sleep disturbance is not a secondary symptom of PD or that sleep disturbance has become independent of original PD precipitants.

Explaining the relationship between sleep disturbance and anxiety-related disorders: psychological and psychophysiological models

Although the extant research indicates that sleep disturbances and anxiety-related processes mutually influence each other, the mechanisms through which this occurs is not yet clear. The dominant psychological and psychophysiological models of insomnia disorder certainly provide clues about these mechanisms.

Insomnia disorder is a sleep disorder characterized by subjective difficulties with sleep onset and/or sleep maintenance, despite adequate opportunity to sleep, with associated daytime impairment or distress [46]. A wealth of research has advanced our understanding of insomnia as a condition resulting from and reinforced by maladaptive, sleep-focused cognitions and maladaptive behaviors and coping strategies. Genetic and biological/physiological traits may predispose individuals to the development of insomnia, and physiological disturbances also result from maladaptive cognitions and behaviors. The interaction of cognitive, behavioral, and physiological factors all contribute to a vicious cycle of sleep disturbance and associated distress. The profound value of these models and testimony to their validity is that the CBT-I that is based on these models is the first-line therapy for insomnia disorder, with proven efficacy in insomnia alone and comorbid with a multitude of psychiatric and medical conditions [170, 171]. CBT-I has also demonstrated benefits for anxiety symptoms in several studies [161, 172].

The diathesis-stress model states that there are three interrelated and sequential factors involved in the pathogenesis of insomnia: predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors [173]. Predisposing factors are individual genetic, physiological, or psychological traits that produce differing levels of susceptibility for developing insomnia (e.g., sex, chronotype, genetic polymorphisms affecting arousal regulation or cognition). Precipitating factors are physiological, environmental, or psychological stressors that trigger the onset of disrupted sleep patterns and include factors ranging from physical injury, work-related stress, or a traumatic stressor. They may or may not be psychological in nature. Perpetuating factors are maladaptive strategies for coping with disrupted sleep that contribute to insomnia symptoms and result in chronic insomnia if sustained. They generally reflect efforts to compensate for insufficient nighttime sleep and are comprised of behaviors such as sleeping in on weekends, taking daytime naps, and increasing time in bed in an effort to obtain the desired amount of sleep. The perpetuating influence of the latter behaviors is explained by the stimulus-control model proposed by Bootzin [174], and is anchored in classical conditioning theory. Increased time in bed in the absence of actual sleep eventually results in increased frustration in bed (i.e., cognitive and physiological arousal), which effectively reduces the likelihood of sleep and results in a further perpetuation of wakefulness rather than sleep. Their perpetuating effect is enhanced by the fact that the compensatory mechanisms result in efforts to sleep at physiologically suboptimal times (i.e., in the absence of homeostatic and circadian pressures to sleep).

Cognitive models of insomnia focus on thoughts, beliefs, and/or feelings that may interfere with sleep and lead to maladaptive coping behaviors [175]. According to cognitive models of insomnia, excessive worry and rumination lead to arousal and distress, all of which precipitate and perpetuate insomnia symptoms [175]. Harvey hypothesized that insomnia is driven by inappropriate worry about sleep and sleep-related consequences. This worry subsequently leads to physiological arousal, selective attention to sleep-related threats (e.g., ambient noise), and the adoption of maladaptive safety behaviors. Another cognitive model proposed by Espie proposes that psychological and/or physiological stress leads to selective attention towards stressors, which inhibits the natural “de-arousal” that is necessary to initiate sleep [176].

Riemann and colleagues have advanced a hyperarousal model of insomnia that incorporates the elements of the above models while also emphasizing a fundamental contribution of genetic and physiological vulnerability to sleep/wake regulatory problems and to hyperarousal at a physiological as well as cognitive level. In their words, they conceptualize insomnia as “a final common pathway resulting from the interplay between a genetic vulnerability for an imbalance between arousing and sleep-inducing brain activity, psychosocial/medical stressors and perpetuating mechanisms including dysfunctional sleep-related behavior, learned sleep preventing associations, and other cognitive factors like tendency to worry/ruminate” [177]. They cite evidence indicating that hyperarousal processes from the molecular to higher system levels play a role in the pathophysiology of insomnia [177]. Several other researcher groups have demonstrated that hyperarousal in insomnia exists in cognitive (e.g., sleep-related worries [178, 179], somatic/physiologic (e.g., increased heart rate; [178, 179]), and cortical (e.g., high frequency EEG) [179] domains. Riemann et al. [177] have pointed out that while standard visual scoring of EEG has often failed to show differences between insomnia and controls, more sophisticated approaches to EEG analysis are pointing to subtle and dynamic features that distinguish good from poor sleepers. These methods are now often used in insomnia disorder research but have only been used in a small number of studies of sleep in anxiety-related disorders [120, 153, 154].

Altogether, research on insomnia provides strong evidence for an interplay between biological predispositions, sleep-disrupting life events, and maladaptive coping behaviors that result in cognitive and physiological hyperarousal, that then perpetuate the cycle of sleep disturbance. The model described by Riemann et al. proposes both cognitive-behavioral and neurobiological pathways through which biological and cognitive risk factors may lead to insomnia as well as anxiety disorders, that then positively reinforce sleep-disturbance in a vicious-cyclic pattern.

Applicability of the dominant insomnia models to PTSD

Consistent with the above models, a traumatic event amounts to a classic and severe insomnia “precipitating factor” that may result in disrupted sleep owing to a variety of factors [180]. From a psychological perspective, nighttime arousal that occurs immediately following trauma may be adaptive in settings of increased predatory threat (e.g., combat), or owing to one’s increased vulnerability when asleep [181, 182]. Unfortunately, whether initially adaptive or not, compensatory behaviors (e.g., naps) to compensate for nighttime sleep deficits will result in mistimed sleep, and therefore wakefulness in bed even in the absence of psychological distress, and thereby contribute to conditioned arousal. On top of this, nighttime trauma-related psychological distress, such as distressing trauma memories and ruminations, and frightful awakenings occurring either spontaneously or from nightmares, are likely to contribute to conditioned arousal in the sleep environment. Although the insomnia models emphasize sleep-related cognitions as a precipitant of hyperarousal, the essential ingredient is that worry in the bedroom, at night, and in the sleep environment precipitates hyperarousal. In this context, the application of insomnia models to PTSD is therefore straightforward, and the success of standard CBT-I for treating sleep disturbance in PTSD provides strong support for its relevance to PTSD [160].

Fear of sleep is common in PTSD and distinguishes sleep-related cognitions in PTSD from insomnia (in which individuals desire rather than fear sleep). Evidence suggests that fear of sleep is driven by both fear of having a nightmare and fear of the vulnerability that occurs during sleep [163, 183–185]. Fear of sleep may result in individuals avoiding sleep and/or in difficulties with sleep initiation. Some studies have elucidated an association between fear of sleep and insomnia symptoms [163, 185, 186], whereas other studies have found no such association [183]. One highly credible explanation for the latter findings is that over time, insomnia is no longer driven by fear of sleep and is instead maintained by a pattern of learned maladaptive coping behaviors that are no longer dependent on the initial precipitating causes [183].

Applicability of the dominant insomnia models to GAD

Cognitive and hyperarousal models of insomnia may be particularly applicable for insomnia pathogenesis in GAD. A cardinal feature of GAD is excessive cognitive activity, specifically worry and rumination. Although not performed specifically in GAD subject, one study demonstrated that sleep-related rumination was associated with both trait and state arousal in insomnia disorder [187]. Several studies have also demonstrated associations between worry, rumination, and sleep disturbance, though most of these studies are limited to undergraduate samples and results may not be generalizable [188–192]. On the other hand, some studies examining trait worry and rumination failed to find significant associations with sleep disturbance [193]. O’Kearney et al. [194] found that worry was associated with insomnia symptoms as measured by the ISI, but not specific sleep continuity parameters.

Applicability of Dominant Insomnia Models to PD

Within the insomnia model framework, nocturnal panic attacks can be considered a precipitating factor for insomnia, disrupting sleep, and contributing to sleep–environment arousal and fear of having another panic attack [79]. Repeated nocturnal panic attacks produce conditioned fear (e.g., hyperarousal) and avoidance of sleep [79], which results in the adoption of maladaptive sleep-related behaviors (e.g., sleeping in brightly lit and very loud environments to obtain rest but avoid deep sleep). Conditioned fear, avoidance of sleep, and maladaptive safety behaviors are perpetuating factors and maintain insomnia symptoms in the absence of nocturnal panic attacks.

Two studies have demonstrated the presence of insomnia symptoms in the absence of nocturnal panic attacks, suggesting that other factors may be involved in insomnia pathogenesis in PD [72, 195, 196]. Anxiety sensitivity—a tendency to experience excessive fear of anxiety-related sensations based on the fear that these sensations are harmful [197] has been associated with sleep onset difficulties in PD [198]. Anxiety sensitivity may amplify the conditioned hyperarousal characteristic of insomnia by leading to a hyper-focus on physiological symptoms. Related to this, two studies manipulating pre-sleep appraisal of sleep physiology support this theory by demonstrating that individuals with PD and nocturnal panic report more distress when they believe that physiological signals are abnormal [199, 200].

Contrasting with this idea of anxiety sensitivity, Craske and Tsao [74] also propose that nocturnal panic in PD is driven in part by fear of loss of vigilance. Evidence cited to support this model included studies demonstrating higher physiological and self-reported emotional reactivity to relaxation and imagery exercises, greater self-reports of panic attacks following relaxation and fatigue, and greater self-reported discomfort during relaxation exercises in individuals with PD and nocturnal panic compared with individuals with PD without nocturnal panic [80, 201, 202].

Applicability of dominant insomnia models to OCD

A recent study exploring associations between insomnia symptoms and OCD symptoms in an undergraduate sample found that insomnia symptoms were associated with obsessions, but not compulsions [203]. This finding suggests that similar to other anxiety-related disorders, hyperarousal and cognitive activity may be driving insomnia in individuals with OCD as obsessions are characterized by heightened arousal and compulsions serve to alleviate anxiety.

Summary

In summary, the above-described findings implicate fear, threat, and anxiety-related cognitions occurring at night or in the sleep environment, or in a trait-like fashion and therefore likely to occur at night, in sleep disturbance associated with anxiety-related disorders. Whether they are focused on anxiety about missed sleep (insomnia) or any other range of concerns may be less important than the fact that they reflect overall cognitive hyperarousal in the sleep environment and as such result in physiological arousal as well as all the downstream compensatory and conditioning phenomena typical of insomnia disorder. Overall, this reflects a transdiagnostic process, consistent with a transdiagnostic model of insomnia relevant across psychiatric disorders.

Affective and cognitive neuroscience of sleep inform the understanding of sleep disturbance in anxiety-related disorders: emotion regulation and emotional memory

Insomnia models satisfactorily explain many of the subjective sleep complaints and insomnia manifestations per se in anxiety-related disorders, but they do not fully or explicitly incorporate the effects of objective disruptions of sleep integrity on two aspects of brain functioning that may be elemental to the disorders discussed here: emotion regulation and emotional memory.

Sleep disturbance and emotion regulation

Emotion regulation generally refers to the ability to modulate emotional experiences in a way that is responsive to the context of a situation as well as an organism’s long-term objectives [187]. In anxiety disorders, emotion-regulatory problems manifest as the maladaptive expression of fearful and anxious emotions and emotional responses. Emotion regulation may be considered an aspect of cognitive executive function [4]. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) has been demonstrated to play an important role in emotion regulation [204, 205], and the frontal lobes may be particularly vulnerable to sleep loss. Gruber and Cassoff [4] recently published an informative review of empirical findings and a conceptual framework for understanding the importance of sleep for executive functioning and emotion regulation more specifically.

Related to this, it has been reported that deficits in cognitive inhibition (e.g.,“tuning out” irrelevant stimuli) [206] and emotion regulation [187] were associated with sleep-related rumination in individuals with insomnia disorder. Particular to GAD, one study found that difficulties with emotion regulation mediated the association between GAD diagnosis and insomnia symptoms [207]. A recent study in PD found that poorer performance on a cognitive inhibition task was associated with longer sleep onset latency and reduced sleep quality in individuals with PD [208].

A recent imaging study provides neurobiological evidence for the role of emotion regulation in the anxiety–sleep relationship. Pace-Schott et al. found that compared with GAD and insomnia disorder groups, a good sleeper group exhibited greater resting-state functional connectivity between the left amygdala and a bilateral region of the rACC. As described earlier, the rACC is part of a prefrontal network believed to exert top-down control over amygdala activity and may constitute an emotion-regulatory circuit. These findings support the idea that deficits in emotion regulation may play a role in both anxiety and insomnia pathogenesis [209].

These studies do not explain causal relationships, and do not necessarily distinguish between objective sleep disruption and insomnia symptoms/disorder per se, yet they provide evidence that deficits in cognitive functions, which may result from sleep disturbance or be a manifestation of an anxiety disorder, are mechanistically involved in the sleep-disturbance-anxiety disorder cycle.

Sleep and memory: relevance to anxiety-related disorders

A sizable body of research now provides strong evidence that sleep has an important role in memory consolidation [10, 11, 210–213]. The “off-line” state of sleep provides a unique opportunity to consolidate information considered relevant to the organism through the reinforcement of key synaptic connections in the relative absence of environmental inputs and high energy-expenditure needs [10]. Although the most-compelling evidence currently points to NREMS as the major driver of sleep-dependent memory consolidation, both NREMS and REMS have been shown to be relevant for consolidation of memory of various sorts [11, 210, 214]. Research on sleep in anxiety-related disorders, and PTSD in particular, has honed in on REMS as an important player in the processing of fearful, threatening, or distressing experiences in a way that results in selective and adaptive consolidation of emotional memories [215, 216].

Fear conditioning and related protocols in both animal models and human subjects constitute the dominant approach for studying the role of sleep and REMS in emotional learning relevant to anxiety-related disorders [13, 217, 218]. Fear conditioning involves the transformation of a neutral stimulus, such as a neutral visual image or context, into a frightening stimulus through its repetitive pairing with an aversive experience, such as an electric shock. Via classical conditioning, the neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus eliciting a fearful emotional response, usually measured using electrophysiology techniques such as skin conductance response or electromyography responses in humans. Once established, conditioned fear can be extinguished through subsequent repetitive presentation of the conditioned stimulus in the absence of the aversive stimulus. Modifications of the simplest fear-conditioning protocols exist, including addition of “safety” stimuli that are never paired with an aversive stimulus, the responses to which can be compared with conditioned fear responses to assess the subject’s ability to discriminate between fear and safety cues. Neuroimaging research indicates that fear extinction is mediated in large part by the mPFC, in particular the ventromedial PFC and rACC, which are structures implicated in anxiety-related disorders [13, 219].

Although findings are not entirely consistent across studies, which utilize different measures of REMS consolidation and/or different outcome measures, recent findings in humans indicate that intact REMS is important for adaptive extinction of conditioned fear, including retention of extinction over time, and the ability to distinguish between safety and fear signals [218, 220]. This has important implications for psychotherapies since extinction and safety learning are psychological models underlying psychotherapy for anxiety. Although not focused on REMS, there is indeed some evidence indicating that sleep may enhance the efficacy of phobia and SAD treatment [221]. Exposure therapy followed by a period of sleep is associated with decreases in heart rate [222], skin conductance [222], and self-reported fear [223] when confronted with the feared stimulus compared with sessions followed by wake. Poorer sleep at baseline was associated with poorer outcome following CBT treatment for SAD and more restful sleep following sessions was associated with a greater reduction in SAD symptoms [224].

Although fear conditioning is a form of implicit emotional learning, some researchers have also found REMS associations with declarative forms of emotional memory [14, 225, 226]. These studies may be most pertinent to PTSD, the symptoms of which revolve around a traumatic emotional memory and include persistent, intrusive emotional memories [227]. For example, Walker et al. found that higher REMS duration correlated with enhanced emotional, vs. neutral, recall in a nap paradigm involving recall for emotionally distressing vs. neutral images [225]. Walker and others have proposed an emotional processing function to REMS, wherein REMS enhances the declarative recall of emotional memories while diffusing the negative emotional valence [216]. On the other hand, several studies reported findings indicating that REMS in healthy subjected either heightened, or did not affect, the emotional tone associated with memories [15, 226, 228, 229]. Furthermore, a REM-deprivation study found that selective REMS deprivation did not impact emotional memory. Another study found that while sleep after learning did enhance emotional memory recall relative to a non-sleep group, selective REM deprivation had no impact on negative vs. neutral recall [230]. These varied findings leave researchers with many unanswered puzzles, and suggest that REM/NREM distinctions may be inadequate for pinpointing the complexities of sleep effects on emotional memory.

Sleep spindles deserve brief mention because sleep spindles reflect memory consolidation processes involving the coordinated oscillations of the thalamo-cortical circuitry, the hippocampus and the cerebral cortex that together result in the transfer of information from temporary storage in the hippocampus to more durable cortical storage [211, 231]. In a recent laboratory study in which subjects viewed a trauma film prior to either overnight sleep, a day of wake, or sleep deprivation, Kleim and colleagues [232] found that greater N2 sleep and more parietal spindles (13–15 Hz) in the sleep group were associated with fewer intrusive memories in the week following the laboratory exposure. They also found that increased N1, wake-after-sleep-onset, and REMD were associated with higher intrusions, and that sleep was protective relative to both the other groups. Although few studies have examined spindles in emotional memory, these findings may be relevant in the context of anxiety-related disorders, especially PTSD.

What about nightmares?

Nightmares continue to be an elusive and intriguing phenomenon, which have generated a host of theories regarding etiology and possible function. A long history of dream theory based primarily in psychoanalytic work, but also in peer-reviewed dream research, has espoused a psychological, sleep-protective, and/or emotional processing function for dreams [57, 233]. These theories are generally anchored in the notion that emotional dreams are REMS phenomena [234], that REMS is important for emotional processing (Walker, [212]; Walker & van der Helm, [216]), and that trauma nightmares result from a disruption in the normal emotional processing and consolidation functions of REMS [235–237]. These conceptualizations are grounded in compelling reasoning, but require bolstering by empirical evidence. Further, early research increasingly indicates that trauma nightmares are not an exclusively REMS phenomenon; nightmare awakenings occur out of both REM and NREM sleep [59, 238, 239].

In the context of REM sleep models, it has also been proposed that abnormally elevated adrenergic tone during REMS contributes to the distress of REMS dreams and/or awakenings from REMS [240]. Our current understanding of central nervous system pathways involved in sleep and arousal are generally consistent with this hypothesis: norepinephrine-generating locus coeruleus activity is low during normal sleep, and essentially absent during normal REMS. Excess activation of the locus coeruleus could perturb REMS. The hypothesis that excessive adrenergic tone during sleep contributes to nightmares seems reasonable and could apply regardless of sleep stage context. We are not aware of studies that have examined this hypothesis. Results from one recent study demonstrated that reduced respiratory sinus arrhythmia during sleep, a measure of parasympathetic tone, was a predictor of nightmare endorsement the following morning [241]. This may indicate that a disruption in the normal balance of parasympathetic vs. sympathetic tone contributes to nightmares, but is not direct evidence of enhanced sympathetic activity.

Despite our limited understanding of the neurobiology underlying the generation of nightmares, nightmares likely contribute to the maintenance of PTSD and sleep disturbance in a manner consistent with the insomnia processes discussed previously. Nightmares are likely to contribute to fear of sleep and sleep avoidance, factors that contribute to altered sleep-related behaviors and insomnia. Short et al. also demonstrated that daytime PTSD symptoms and fear of sleep were prospectively related to nightmares [163]. The effects of repeated activation of trauma-related thoughts during sleep are unknown, but one might speculate that they contribute to reinforcement of memory-containing neural networks (the PTSD “fear network”), thereby consolidating those memories in association with distressing emotions.

Abnormal movements during sleep: from muscle twitches to nightmare enactment

Abnormal movements during sleep in anxiety-related disorders are also poorly understood phenomena, and are primarily reported in PSTD, as opposed to other anxiety-related disorders. They are grouped together here because they involve abnormal motor behavior during sleep, rather than due to a clearly understood neurobiological overlap. Muscle twitching in the context of REMS atonia is normal phenomena, and there is even evidence that it plays a role in sensorimotor development [214]. However, indications that muscle movements are increased in PTSD relative to normal are consistent with the overall concept of hyperarousal during sleep. Carwile and colleagues proposed that RBD-like phenomena in PTSD (nightmare enactment) may be due to abnormalities in LC NE firing. However, in contrast with the idea that NE activity is elevated in REMS, they propose that it is a high “turnover” and resulting depletion of NE in the LC of PTSD patients that disrupts REM atonia, just like degeneration of LC neurons occurs in neurogenerative diseases [242]. Further research is clearly indicated to better understand the neurobiology of these phenomena and their implications for outcomes in anxiety-related disorders. Regardless of etiology, like other sleep-disrupting events described in this report, they are likely to contribute to the many downstream effects of objective sleep disturbance and the cycle of behavioral, cognitive, and physiological problems that characterize the sleep–anxiety relationship.

Sleep disturbance and anxiety-related disorders: underlying neuromodulatory context

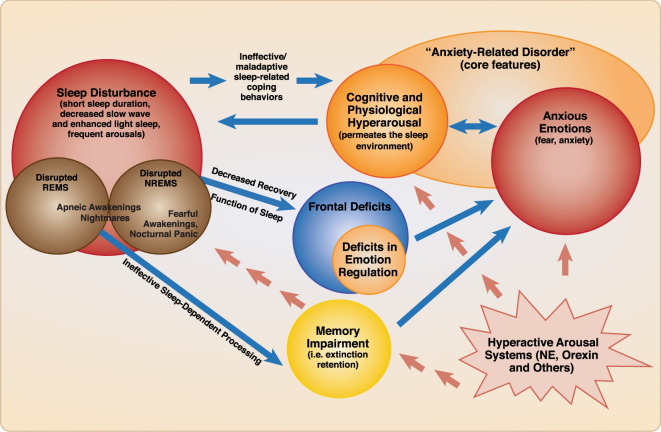

Figure 4 provides a schematic diagram modeling the psychological and neurocognitive factors that link sleep disturbance and anxiety-related disorders in a bidirectional fashion. This relationship occurs in the setting of heightened activity in known neuromodulatory pathways. Animal and pharmacology studies point to important neuromodulators, such as norepinephrine and hypocretin, that play an important role in this dynamic.

Fig. 4.

Schematic diagram including the psychological and neurocognitive factors that link sleep disturbance and anxiety-related disorders in a bidirectional fashion. Sleep disturbance, regardless of cause, may result in maladaptive sleep-related compensatory behaviors, resulting in sleep timing that is out-of-synchrony with sleep drive, and therefore wake time in bed. This results in hyperarousal (i.e., cognitive and emotional) in the sleep environment, promoting a vicious cycle of sleep disturbance, compensatory behaviors, hyperarousal cognitions and anxious emotions. Sleep disturbance also has deleterious effects on cognitive functions, due to insufficient sleep-dependent recovery of neural substrates that carry out said functions during wake; this results in widespread deficits including deficits in emotion regulation (i.e., reduced ability to modulate anxious emotions). Sleep disturbance also disrupts processes thought to be carried out during sleep, such as adaptive memory functions (e.g., fear extinction retention; safety learning); this also promotes or maintains anxiety/fear emotions. Anxious emotions and cognitive hyperarousal are mutually reinforcing, and feed back into the sleep disturbance cycle. The specific role of REMS and NREMS in recovery and sleep-dependent processes is a topic of investigation. The nature of mechanistic connections between anxiety-related events such as nightmares and panicked awakenings, and NREM or REM sleep-dependent processes, remains to be demonstrated with empirical evidence. At the very least, their promotion of cognitive hyperarousal and anxious emotions can be inferred from their contribution to sleep disruption and the fearful emotions they generate. A neuromodulatory milieu involving heightened arousal signals, e.g., norepinephrine, and/or hypocretin, drives and underlies this relationship

Major neuromodulators in sleep–wake regulation and anxiety-related disorders

Norepinephrine

Norepinephrine is released both peripherally (adrenal medulla) and in the central nervous system as a neurotransmitter and plays a central role in both sleep regulation and anxiety (See Fig. 1). Although its nearly exclusive CNS source, the locus coeruleus, seems to be too small to be captured by classic neuroimaging techniques (although see PET studies above and fMRI findings by Naegeli et al. [243] in PTSD), it is clearly central to anxiety- and fear-related processes in the CNS through its direct innervation of the amygdala and its inhibitory inputs to the VLPO, among a multitude of other projections (e.g., cerebral cortex). Normally, NE activity is high during wake, low during NREMS, and nearly completely quiescent during REMS [244]. Human studies have provided some evidence of elevated sympathetic tone and/or LC activity in anxiety-disordered sleep [29, 136, 245].

Pharmacological research has studied various noradrenergic blockers for treatment of anxiety-related disorders. For example, the selective alpha-1-adrenergic blocker prazosin has demonstrated benefits in multiple small to medium-sized RCTs for PTSD symptoms and trauma nightmares [246–248]. Disappointingly, a recent large RCT of prazosin for PTSD in veterans demonstrated no benefit relative to placebo and no benefit overall for either PTSD symptoms overall or for nightmares [249, 250]. One recent study indicates that higher baseline systolic blood pressure predicts greater therapeutic response to prazosin for nightmares and sleep disturbance [251]. Doxazosin, a medication with the same alpha-1 blocking effects of prazosin, but with a longer half-life, has shown some benefit in preliminary studies and is currently being studied as an alternative to prazosin [252]. Interestingly, it is thought that doxazosin is less able to cross the blood–brain barrier than prazosin. This raises questions about whether PTSD is associated with greater blood–brain barrier permeability, thus allowing entry of less lipophilic agents, or whether some of the CNS benefits are mediated via peripheral adrenergic nervous system responses. Finally, the alpha-2-agonist clonidine has shown some benefit in PTSD nightmares, however it has not been extensively studied [253].

Serotonin

The neurotransmitter serotonin (5-hydroxytryptophan, 5HT) is a neurotransmitter that has an important role in arousal (see Fig. 1) and which also plays an important role in the regulation of anxiety and mood states. It is produced in the dorsal raphe nucleus, which has broad axonal projections including projections to the VLPO (inhibitory) and the cerebral cortex. The arousal effect of 5HT is mediated in part by 5HT-2A receptor activity, based on animal studies as well as clinical research demonstrating that agents with high 5HT-2A blocking effects are sedating (i.e., trazodone, quetiapine, amitriptyline). Agents that selectively inhibit the reuptake of serotonin into neurons (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, (SSRI)) and thereby increase 5HT in the synapse, are first-line agents for anxiety and mood-related disorders, including all of the disorders described in this review. Serotonin levels are high during wake, low during NREMS and at their lowest during REMS [244]. One can therefore see how agents that enhance 5HT across 24 hours (SSRI’s and SNRI’s, which also block norepinephrine reuptake) might have untoward effects on sleep even if beneficial for anxiety. On the other hand, downregulation of 5HT-2A receptors with prolonged SSRI administration may be associated with resolution of initial activating effects of these drugs.

Histamine

The role of histamine in sleep/wake circuitry is demonstrated in basic research and is supported by the broad use, though limited controlled research, of various drugs with anti-histaminergic properties (e.g., trazodone, quetiapine, amitriptyline, doxepin, diphenhydramine, and cetirizine). It has been proposed that histamine release is under circadian control, and is released earlier than other neurotransmitters. Although circadian disruptions are a major topic that is hardly covered in this review, the possibility the role of circadian timing of histamine release may be relevant to early morning awakening in anxiety-related disorders. Anti-histamines are commonly used off-label for the treatment of anxiety, although evidence for specificity as an anxiolytic, as opposed to a sedating agent, is weak.

Acetylcholine

Acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter synthesized in several brain regions/nuclei, including the pedunculopontine tegmentum (pons), the lateraldorsal tegmentum (pons) and the basal forebrain and is also an important arousal neurotransmitter. In contrast to the other major neuromodulators described above, CNS cholinergic activity is normally high in both wake and REMS, although decreased in NREMS [244]. Walker and colleagues [212, 216] have postulated that elevated cholinergic activity in REMS, combined with maximal suppression of noradrenergic activity during this stage, contributes to the emotion and emotional memory processing function of REMS. Although this remains highly theoretical, Walker and colleagues propose that the memory-promoting function of acetylcholine in REMS acts to consolidate the declarative memories (an adaptive process) in the absence of the NE-promoted emotional “tag”.

Several other medications with effects on these neurotransmitters systems have been used to treat sleep disturbance in anxiety-related disorders. Trazodone, for example, is used widely in public health settings [254] despite limited controlled data on efficacy and is known to block receptors for histamine, serotonin (5HT-2A/2C), and alpha-adrenergic receptors, [255]. A recent study of cyclobenzaprine, a tricyclic molecule structurally similar to amitriptyline, which like trazodone blocks histamine, alpha-adrenergic, and serotonergic 5-HT2A receptors, was halted during a Phase III development trial because of inadequate separation from placebo for the primary sleep endpoint in military-related PTSD (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT03062540).

Dopamine

Dopamine, produced in the ventral tegmental area and the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray, is also an important arousal-promoting neurotransmitter. While mostly known for its central involvement in reward neurocircuitry and disorders of addiction, a recent study of quetiapine for PTSD lends some support for dopamine-receptor blockade in the treatment of anxiety-related disorders, and quetiapine is often used off-label for the treatment of insomnia [256, 257]. Quetiapine’s broad inhibition of multiple arousal-promoting neurotransmitters, including serotonin (5HT-2A), histamine, and NE (alpha-1) do raise questions about dopamine-specific mechanisms.

Hypocretin/orexin

The hypocretins, also known as orexins, including hypocretin-1 and 2, are neuropeptides with a well-established role in promoting and stabilizing arousal [258–260]. Recent publications present the growing evidence implicating the hypocretins in anxiety-related disorders, and the pathways through which they act [261, 262]. Hypocretin is produced in the hypothalamus, and hypocretin-producing neurons have widespread excitatory projections, including to the main wake-promoting centers (see Fig. 1a), the cerebral cortex, and the amygdala. Overall, the research indicates that hyperactivity of the orexin system contributes to anxiety-related behavior. While most research has been performed in animal models, one recent study demonstrated elevated CSF orexin in patients with PD. An interesting recent study found that hypocretin was related to panicked awakenings in a rodent model. These findings may be highly relevant to understanding nocturnal panic attacks and frightful awakenings in the context of PTSD and PD and deserve further study.

The dual-orexin antagonist suvorexant is FDA-approved for the treatment of insomnia. At present there are no published trials of hypocretin/orexin antagonists in anxiety-related disorders, though a few studies are underway. Theoretically, hypocretin/orexin antagonists would target more-discrete pathways than commonly used GABAergic hypnotics, and ideally would be suitable for individuals who demonstrate abnormally increased hypocretin activity [263]. There is preclinical evidence that orexin antagonism can block stress-induced sleep disturbance but have no effect on baseline autonomic and autonomic activity [264]. The implication is that it is possible to develop compounds that only affect stress-related over-activation of arousal pathways without interfering with normal activity in healthy individuals.

GABA

GABA receptors are ubiquitous in the CNS and GABA-mediated CNS inhibition has a huge role in sleep promotion through specific pathways. On the other hand, endogenous GABA-mediated promotion of sleep involves a targeted suppression of arousal-promoting nuclei, rather than a more global inhibition of the cerebral cortex (See Fig. 1). Despite some theoretical value of targeting GABAergic function in anxiety-related disorders, the potential for adverse effects (tolerance, dependence, cognitive side-effects, ataxia, respiratory depression) are substantial given widespread distribution of GABAergic inhibitory neurons in the brainstem, cerebellum, and cortex [265]. At least in PTSD, there is also limited evidence of diminished GABA brain activity [266]. Furthermore, GABA also plays a role in arousal through inhibition of inhibitory interneurons in the cerebral cortex. This may contribute to paradoxical disinhibition in response to GABAergic drugs in some individuals. Despite concerns, benzodiazepines have demonstrated benefits for anxiety symptoms, and their use continues to be widespread [267]. There are only a few published controlled studies focused on GABAergic hypnotics in PTSD [268, 269], and the extant evidence is insufficient for recommending a GABAergic approach.

The so-called non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists, or “z-drugs,” were developed to specifically target subtypes of the GABA-A receptor, with the aim of reducing adverse effects. One study of eszopiclone, for example, which targets the alpha-3 subunit specifically, provides preliminary evidence of benefit for both sleep disturbance and PTSD [269]. The advantages of z-drugs over the benzodiazepines in sleep disturbance in anxiety-related disorders has not been well-established.

The HPA axis and CRF