Abstract

Research on filoviruses has historically focused on the highly pathogenic ebola- and marburgviruses. Indeed, until recently, these were the only two genera in the filovirus family. Recent advances in sequencing technologies have facilitated the discovery of not only a new ebolavirus, but also three new filovirus genera and a sixth proposed genus. While two of these new genera are similar to the ebola- and marburgviruses, the other two, discovered in saltwater fishes, are considerably more diverse. Nonetheless, these viruses retain a number of key features of the other filoviruses. Here, we review the key characteristics of filovirus replication and transcription, highlighting similarities and differences between the viruses. In particular, we focus on key regulatory elements in the genomes, replication and transcription strategies, and the conservation of protein domains and functions amongst the viruses. Additionally, using computational analyses we were able to identify potential homology and functions for some of the genes of the novel filoviruses with previously unknown functions. Although none of the newly discovered filoviruses have yet been isolated, initial studies of some of these viruses using minigenome systems have yielded insights into their mechanisms of replication and transcription. In general, the Cuevavirus and proposed Dianlovirus genera appear to follow the transcription and replication strategies employed by the ebola- and marburgviruses, respectively. While our knowledge of the fish filoviruses is currently limited to sequence analysis, the lack of certain conserved motifs and even entire genes necessitates that they have evolved distinct mechanisms of replication and transcription.

Keywords: Ebola virus, Marburg virus, filoviruses, nonsegmented negative sense RNA viruses, genome replication and transcription

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Filoviruses belong to the group of nonsegmented negative sense (NNS) RNA viruses. In the past, research mainly focused on the most prominent members of the filovirus family, Ebola virus (EBOV) and Marburg virus (MARV) both of which are highly pathogenic for humans [1, 2]. EBOV and MARV are genetically distinct and belong to different filovirus genera, Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus (Fig. 1a). With the advent of high-throughput sequencing technology, the filovirus family has expanded. Newly discovered filoviruses that have not been associated with outbreaks in humans yet include Bombali virus (BOMV), a proposed new member of the Ebolavirus genus [3], Lloviu virus (LLOV) [4–6], Měnglà virus (MLAV) [7, 8], and some fascinating fish filoviruses whose genome organization is very different from the “conventional” filovirus genomes [9] (Fig. 1b). Among these novel filoviruses, LLOV, MLAV, and the fish filoviruses XTīlăng and Huángjiāo viruses (XILV and HUJV, respectively) are genetically distinct from ebola- and marburgviruses and have been, or will be, assigned to distinct filovirus genera [6] (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1. Comparison of filovirus genomes.

(a) A phylogenic tree of the indicated filoviruses was performed by aligning the L protein sequences using the Geneious Prime software. Labeled arcs indicate the officially assigned filovirus genera [6], with the exception of the “Dianloviruses” genus which has been proposed but not yet accepted. BOMV was added to the Ebolavirus genus, although it has not been assigned officially to the genus, (b) Schematics of filovirus genomes. Each filovirus genus is represented by the prototypical virus. Schematics are depicted to scale. Leader and trailer sequences are indicated by black bars, with missing sequence information indicated by squiggly lines. Genes are depicted as colored bars with lighter portions indicating open reading frames (ORFs). Homologous genes are colored similarly. Since the LLOV VP24 and L genes appear to form a bicistronic transcript, the untranslated region separating the VP24 and L ORFs is colored by stripes. For XILV and HUJV, genes with no homology to genes of other filoviruses and no known function are indicated in brown with lighter portions indicating ORFs. Sites of gene overlaps are indicated by black arrows. Intergenic regions are in white. Sites of cotranscriptional mRNA editing are indicated by asterisks. BDBV, Bundibugyo virus; BOMV, Bombali virus; EBOV, Ebola virus; GP, glycoprotein; HUJV, Huángjiāo virus; L, large protein; LLOV, Lloviu virus; MARV, Marburg virus; MLAV, Měnglà virus; NP, nucleoprotein; ORE, open reading frame; RAW, Ravn virus; RESTV, Reston virus; sGP, soluble glycoprotein; ssGP, small soluble glycoprotein; SUDV, Sudan virus; TAFV, Taï Forest virus; XILV, Xīlăng virus.

In line with the proposed chiropteran origin of the previously identified filoviruses, some of the new filoviruses were discovered when their RNA was found in different bat species: BOMV RNA was isolated from little free-tailed bats (Chaerephon pumilus) and Angolan free-tailed bats (Mops condylurus) in Sierra Leone and Kenya [3, 10], LLOV RNA was isolated from Schreiber’s long-fingered bats (Miniopterus schreibersii) in Spain and Hungary [4, 5], and MLAV RNA was isolated from a bat of the genus Rousettus in China [7]. In contrast, RNA from the newly discovered XILV and HUJV was isolated from saltwater fishes, the striated frogfish (Antennarius striatus) and the greenfin horse-faced filefish (Thamnaconus septentrionalis), respectively, in the South and East China Seas [9]. While most of the known marburg- and ebolaviruses cause disease in humans, the pathogenic potential of the newly discovered filoviruses is not known. Of note, none of these viruses have been isolated from either an animal host or human patients - the available sequence information is based on viral RNA extracted from bats or fish and is, with the exception of BOMV, incomplete with various amounts of terminal genomic sequences missing (Fig. 1b).

The unexpected geographic and genetic diversity of filoviruses raises concerns about unpredictable outbreaks caused by the new members of the family. Having a thorough understanding of the filoviral genome replication mechanisms, including identifying similarities and differences in the replication strategies of the various filoviruses, will be instrumental for designing and developing countermeasures in order to be prepared for potential outbreak scenarios. Here, we provide an overview of filovirus genome replication and mRNA transcription strategies with a focus on the differences between filovirus genera. In addition to highlighting recent data regarding filoviruses, we also suggest novel functions and potential homology for some of the XILV and HUJV genes based on computational analyses.

2. Marburg- and ebolavirus replication cycle – a brief overview

2.1. Structure of marburg- and ebolavirus particles

Typically, marburg- and ebolavirus particles are filamentous in shape, but their shape can also be pleomorphic [11–14] (Fig. 2). The viral particles are enwrapped by a host-derived membrane covered with protrusions which are formed by the sole viral surface protein, the glycoprotein (GP). During passage through the infected cell, the GP precursor is proteolytically cleaved into two covalently linked subunits, GP1,2,, that are inserted in the viral membrane as trimers (reviewed in [15, 16]). The inner leaflet of the viral membrane is lined with the matrix protein, viral protein 40 (VP40). VP40 drives viral budding and particle formation, and is able to assemble virus-like particles in the absence of other viral proteins (reviewed in [15, 17, 18]). VP40 gives marburg- and ebolavirus particles their typical filamentous shape. The inner core of the marburg- and ebolavirus particles is the so-called nucleocapsid, a ribonucleoprotein complex that is composed of the viral RNA genome and five associated viral proteins, nucleoprotein (NP; encapsidates the RNA genome), VP35 (cofactor of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase), VP30 (transcription activator), VP24 (nucleocapsid maturation factor), and large protein (L; catalytic subunit of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase), of which three - NP, VP35, and VP24 - are essential for the formation of mature nucleocapsids [14, 19–26] (Fig. 7). The nucleocapsid contains all the viral components required for genome replication and transcription. A more detailed description of the nucleocapsid and its components is provided in chapter 5.1.

Fig. 2. Scheme of filovirus particle.

The cell membrane-derived envelope (outer gray oval) is studded with viral glycoprotein trimers (yellow lollipops). The assembly of the matrix protein VP40 (blue) into long, filamentous particles imparts the filovirus particles with their namesake virion shape. The viral nucleocapsid consists of the negative sense genome (black line) enwrapped in the nucleoprotein (NP, pink spheres) along with the polymerase cofactor VP35 (green spheres), the transcription factor VP30 (dark gray spheres), the nucleocapsid protein VP24 (red spheres), and the catalytic polymerase subunit L (light gray ring with appendices). Based on the structure of the vesicular stomatitis virus L protein [132], the filoviral L is hypothetically shown as a ring with an appendage formed by three globular domains.

2.2. The filoviral replication cycle

Filovirus entry is a complex, multi-step process which is very well reviewed in [16]. Briefly, attachment of marburg- and ebolavirus particles to the cell occurs through interaction of the GP1 subunit with various host cell factors, including C-type lectins and glycosaminoglycans, or through interaction of phosphatidylserine on the outer leaflet of the viral membrane with phosphatidylserine receptors, such as members of the Tyro3, Axl, and Mer (TAM) and T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain (TIM) families of receptors (reviewed in [16]). Following attachment, the dominant uptake mechanism of the viral particles seems to be macropinocytosis [27–29]. In the endosomes, GP1,2 is processed by cathepsins [30]. This cleavage step exposes the receptor binding site on GP1 and facilitates binding of GP1,2 to the filovirus receptor, endosomal membrane protein Niemann Pick C1 (NPC1) [31, 32]. Similar to marburg- and ebolavirus glycoproteins, LLOV and MLAV glycoproteins are able to use NPC1, including human NPC1, as an entry receptor [7, 33, 34]. This not only confirms the close relationship of these viruses to marburg- and ebolaviruses but also shows their ability to infect human cells. It is not yet known whether XILV and HUJV use NPC1 as an entry receptor. The low sequence similarity of the putative XILV and HUJV glycoproteins with mammalian filovirus glycoproteins opens the possibility that the mechanism of entry is divergent. Dramatic structural rearrangements of GP1,2 precede GP2-driven fusion of the viral and the endosomal membranes (reviewed in [15]). Following fusion, the nucleocapsid is released into the cytoplasm of the infected cell where the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase consisting of L and VP35 starts to sequentially transcribe the viral genes using the encapsidated viral genome as a template (Fig. 3). For the ebolaviruses and LLOV, transcription is assisted by the transcription factor VP30. The role of VP30 in marburgvirus transcription is less well understood. This early or “primary” transcription is exclusively faciliated by the viral proteins that were brought into the cell [17, 25, 35]. Each filoviral gene is flanked by transcription start and stop signals that determine the beginning and the end of the transcribed mRNA. During transcription, the viral polymerase enters the genome at a single binding site at the genomic 3’ end and scans for the transcription start signal of the first gene. It then proceeds along the RNA template by stopping and reinitiating at each gene junction, resulting in the synthesis of mainly monocistronic mRNAs [36–38] (Fig. 3). Viral transcription includes the addition of a 5’ cap and a poly(A) tail to the nascent mRNAs by the viral polymerase. The viral mRNAs are then translated by the cellular translation machinery. Viral protein synthesis is the prerequisite for both replication to amplify the viral genomes and secondary transcription to produce more viral mRNA [17] (Fig. 3). During genome replication, the viral polymerase synthesizes a full-length complementary copy of the negative sense RNA genome, the positive sense antigenome, which in turn serves as the template for the production of more genomes (Fig. 3) [38, 39]. Similar to the genome, the antigenome is encapsidated by the nucleocapsid proteins. The antigenome is a mere replication intermediate – only genomes serve as templates for transcription and are packaged into viral particles. Viral RNA synthesis and nucleocapsid assembly take place within viral inclusions that are formed in the cytoplasm of the infected cell [17, 35, 40–42]. Mature marburg- and ebolavirus nucleocapsids are transported from the inclusions to the sites of budding at the plasma membrane via an actin-dependent mechanism [43, 44]. For EBOV, it has been shown that three proteins - NP, VP35, and VP24 - are sufficient to mediate this process [23]. The final step of the viral replication cycle, budding of the assembled virions, is mainly driven by matrix protein VP40 via hijacking components of the cellular endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT). During this process, GP1,2 is targeted to VP40-enriched membranes that enwrap the arriving nucleocapsids in a directional manner (reviewed in [17]).

Fig. 3. Hypothetical model of Ebola virus genome replication and transcription.

(1) EBOV nucleocapsids are released into the cytoplasm of the infected cells after fusion of the viral and the endosomal membranes. The incoming nucleocapsids consist of the NP-RNA complex (NP, pink spheres), VP35 (green spheres), L (light gray ring with appendices), VP24 (red spheres), and contain mostly phosphorylated EBOV VP30 (dark gray spheres). Based on the structure of the vesicular stomatitis virus L protein [132], EBOV L is hypothetically shown as a ring with an appendage formed by three globular domains. (2) The nucleocapsids are released into the cytoplasm of the infected cells where primary transcription occurs. The viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase formed by the catalytic polymerase subunit L and the cofactor VP35 initiates mRNA synthesis. VP35 binds to NP and redirects L to the NP-RNA complex. VP30 acts as a transcription activator and must be dephosphorylated to be functional. Dephosphorylation of VP30 is carried out by cellular phosphatases (dark blue sphere) interacting with the nucleocapsid. Since VP24 condensates the nucleocapsids, we hypothesize that transcription-competent nucleocapids contain no or only small amounts of VP24. (3) L caps the 5’ ends of the mRNAs and methylates the caps. Polyadenylation of the nascent mRNAs occurs through polymerase stuttering. The GP mRNA is cotranscriptionally edited by polymrase stuttering as indicated by the “+A” in the GP transcript. Dissociation of the viral polymerase at the gene borders results in a transcript gradient. (4) The viral mRNAs are translated by the cellular translation machinery. (5) This enables secondary transcription that requires newly synthesized viral proteins. (6) Phosphorylation of VP30 diminishes its function in viral transcription and helps to initiate viral genome replication. VP40 (blue) and VP24 inhibit viral RNA synthesis. VP35 serves as a chaperone to prevent NP from aggregation. Genome replication involves the synthesis of a positive sense antigenome (blue line) that serves as a replication intermediate. (7) VP24 is involved in nucleocapsid condensation and shifts the viral replication cycle towards assembly and budding. Binding of phosphorylated VP30 to NP ensures packaging of VP30 into virions. Fully assembled nucleocapsids are transported by an actin-dependent transport mechanism to the budding sites. Note that there are signficant differences to Marburg virus transcription as explained in the text.

This review focuses on filovirus genome replication and transcription and does not cover entry, assembly, and budding. Excellent overviews of these steps of the viral replication cycle are provided in [15–17]. Despite following the general strategies employed by NNS RNA viruses to replicate and transcribe their genomes, filoviruses have evolved many unique features that will be described in this review. We will also summarize what is known about genome replication and transcription of the newly discovered filoviruses.

3. Tools to study filovirus replication and transcription

3.1. Minigenomes

Transfection-based minigenome systems for NNS RNA viruses are useful tools to identify and characterize both cis-acting signals in the viral RNA genome and protein factors required for genome replication and transcription (reviewed in [45, 46]). The first filovirus minigenome systems were established for MARV and EBOV in 1998 and 1999, respectively, and for Reston virus (RESTV) in 2005 [47–50]. More recently, chimeric minigenome systems have been created for the novel filoviruses LLOV [51, 52] and MLAV [7] (see chapter 6 for more information on these minigenomes). Currently, the development of minigenome systems for the fish filoviruses is hindered by the significant lack of terminal genomic sequences. Since work with filoviruses requires the highest biosafety level (BSL-4), minigenome systems, which enable molecular biological studies under low biosafety level conditions, have been crucial for the analysis of the replication cycle of these viruses.

Filoviral minigenomes are truncated versions of the viral genomes and typically contain the 3’ and 5’ genome ends flanking a reporter gene. The genome ends contain all regulatory elements required for encapsidation, replication, and transcription initiation. The reporter gene is additionally flanked by the viral transcription start and stop signals that govern the initiation and termination of mRNA synthesis by the viral polymerase [38, 39, 46, 53]. Genetic manipulation of any aspect of the minigenomes, including any regulatory element or the reporter gene, is easy since the minigenome cDNA is contained within a plasmid. Expression plasmids encoding the viral proteins required for transcription and genomic replication are co-transfected along with the minigenome plasmid (Fig. 4a). Inside the cells, the minigenome and the viral genes are transcribed from their plasmids by a DNA-dependent RNA polymerase. In most systems, the minigenomes are under the control of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter (reviewed in [46, 53]). RNA polymerase I- and II-driven minigenome systems have also been described [50, 54]. It is of utmost importance that the minigenomes have the correct genome ends after being transcribed by the DNA-dependent RNA polymerase. While some DNA-dependent RNA polymerases, including the T7 RNA polymerase and RNA polymerase I, start transcription at a defined position and generate transcripts with precise 5’ ends, other polymerases, including RNA polymerase II, do not. Generation of precise 3’ ends is generally difficult. To overcome these issues, the minigenomes are flanked by ribozyme sequences in the plasmid backbone. Commonly, the hepatitis delta ribozyme is used to generate 3’ ends and a hammerhead ribozyme is used to generate defined 5’ ends, if required [55–57]. Transcription and replication of the minigenome by the viral polymerase complex assembled in the transfected cells lead to the production of replicated and transcribed minigenome RNA, and reporter gene expression (Fig. 4a). The generated RNA products can be analyzed and quantified by Northern blot analysis, primer extension analysis (a method to analyze initiation of RNA synthesis [58]), and RT-PCR (reviewed in [38, 39, 46, 53]). Minigenome systems have been instrumental in identifying the viral proteins required for genome replication and transcription, studying the function of these proteins, and analyzing regulatory elements on the genome as described below in more detail. An in-depth description of technical tips for the use of filovirus minigenome systems can be found at https://blog.addgene.org/minigenomes-a-safe-way-to-study-dangerous-viruses.

Fig. 4. Tools to study filovirus replication and transcription.

(a) Filovirus minigenome systems involve transfecting cells with expression plasmids encoding the minigenome and the filovirus proteins required for transcription and replication. In most systems, the minigenome is transcribed by ectopically expressed T7 RNA polymerase (T7). There are also minigenome systems in which the minigenome is transcribed by RNA polymerase I (po1I) or RNA polymerase II (po1II). If the expressed nucleocapsid proteins (NP, VP35, L, and VP30) accept the minigenome RNA as a template for replication and transcription, this can be monitored by reporter gene expression, (b) Supplementing the minigenome system with expression plasmids encoding GP, VP40, and VP24 results in the release of single-round infectious virus-like particles (iVLPs) which consist of minigenome nucleocapsids which are packaged and released from the cells similar to viral particles. (c) Filovirus rescue systems involve transfecting cells with a plasmid encoding the full-length viral antigenome along with expression plasmids encoding the nucleocapsid proteins. The nucleocapsid proteins will drive replication of the antigenome, leading to the production of viral genomes. The viral genomes will then be replicated and transcribed, which results in the expression of all viral proteins and production of more genomes. Virus rescue will proceed similarly to infection, with infectious particle assembly, egress, and release.

Filoviral minigenomes typically contain a single gene (monocistronic minigenomes), but minigenomes with several genes encoding distinct reporter proteins have also been used. In these minigenomes, the genes are separated by filovirus-specific gene borders [59–63]. Co-transfection of expression plasmids encoding VP40, GP, and VP24 in addition to plasmids encoding the minigenome and L, NP, VP35, and VP30 results in the assembly and budding of infectious virus-like particles (iVLPs), allowing the study of additional steps in the viral replication cycle, including virus assembly, budding, entry, and primary transcription [25, 64, 65] (Fig. 4b). A variant of this approach, dubbed the transcription- and replication-competent virus-like particle (trVLP) system, encodes the VP40, GP, and VP24 genes in addition to a reporter gene within a tetracistronic minigenome, obviating the need to co-transfect additional plasmids encoding these genes [66].

Various minigenome-based systems have been developed to investigate different aspects of the filoviral replication cycle (reviewed in [46, 53]). The main drawback of the minigenomes is their considerably shorter length compared to the full viral genomes, which might influence different steps of the viral replication cycle, including virus entry, RNA encapsidation, RNA elongation, assembly, and budding. Additionally, the viral protein concentrations and ratios in transfected cells are different from those in infected cells, which might affect the results obtained with minigenome, iVLP, and trVLP systems. This highlights the need to confirm results obtained from these reductionist minigenome-based systems using authentic viral infection.

3.2. Recombinant viruses

Recombinant filoviruses can be generated by transfecting cells with a plasmid containing the full-length cDNA of the viral genome in the antigenomic (+) sense orientation along with plasmids encoding L, NP, VP35, and VP30 [53, 67] (Fig. 4c). Similar to the minigenome system, the viral antigenomic RNA is transcribed from the plasmid in the transfected cells, and the nucleocapsid and polymerase components are expressed. If the antigenomic RNA is recognized as a template for replication by the viral proteins, viral genomic RNA is produced than can then be replicated and transcribed, leading to the production of all viral proteins, and eventually to viral particle formation [45, 68]. Using these virus rescue systems, it is possible to introduce mutations into viral genes or cis-acting elements and to insert additional transcription units into the viral genome, including genes encoding fluorescent proteins. To date, rescue systems have been developed for EBOV, MARV, and RESTV (first descriptions: [69–71]). A thorough overview of the generation and application of recombinant filoviruses is beyond the scope of this article and has been reviewed elsewhere [53, 72].

4. Filovirus genomes

Filovirus genomes consist of a single negative sense RNA molecule which contains a variable number of monocistronic genes in a linear order. The genes are flanked by conserved gene start (GS) and gene end (GE) signals that either overlap or are separted by short intergenic regions (IRs). Located at the filoviral genome ends are the 3’ leader (Le(−)) and the 5’ trailer (Tr(−)). The Le(−) is defined as the sequence upstream of the GS signal of the first gene and the Tr(−) as the sequence downstream of the GE signal of the last gene (Fig. 1b). Both the genomic Le(−) and the antigenomic Tr(+) contain important regulatory elements for replication and transcription as described in chapters 4.1 and 4.2.

Until recently, filovirus genomes were believed to be signficantly longer than the genomes of other NNS RNA viruses (around 19 kb). While this is still true for the mammalian filoviruses, the genomes of the fish filoviruses are considerably shorter (about 17 and 15 kb; Fig. 1b). This genetic diversity is also reflected in the gene number. Ebola- and marburgvirus genomes contain seven genes in a linear order (3’ NP-VP35-VP40-GP-VP30-VP24-L) (Fig. 1b). This gene arrangement is also found with LLOV and MLAV [4, 7], whereas the XILV and HUJV genomes are different, with the XILV genome containing ten open reading frames (ORFs) and the HUJV containing six [6, 9] (Fig. 1b). The XILV genome was initially reported to encode NP, VP40, VP30, and L homologs, two putative glycoproteins, and four proteins with unknown functions [6, 9]. There were no reported homologs for VP35 or VP24 encoded in the XILV genome. HUJV, on the other hand, was reported to encode NP, GP, and L homologs, with no clear homologs to VP35, VP40, VP30, or VP24. Thus, three of the six HUJV genes were reported to encode proteins of unknown function [6, 9] (Fig. 1b). Additional analysis of the XILV and HUJV ORFs with previously unassigned homologs and potential functions is presented in chapter 7. These analyses strongly suggest that ORF2 of the XILV genome encodes a VP35 homolog (Fig. 1b).

4.1. Filoviral replication promoters

The filoviral genomic and antigenomic replication promoters are located at the 3’ end of the genome and antigenome, respectively [58, 73–76]. Serial passaging of EBOV-infected cells led to the generation of defective interfering particles that contained 155 nucleotides of the 3’ end of the genome fused to 176 nucleotides of the 5’ end, indicating that the genomic and antigenomic replication promoters are contained in these regions [77]. NNS RNA viral polymerases enter the genomes and antigenomes exclusively at the 3’ promoter regions. It is not understood how the filoviral polymerase recognizes the promoter and gets access to the RNA template. However, as described in chapter 5, only viral RNA that is complexed with NP and other nucleocapsid proteins is accepted as a template for replication and transcription. It has been shown for other NNS RNA viruses that purified viral polymerase is capable of initiating replication in the absence of NP using short RNA templates [78–81]. Based on these observations, it is conceivable that encapsidation of the extreme 3’ ends of filoviral genomes and antigenomes is not required for initiation of RNA synthesis whereas efficient RNA elongation requires a properly packaged NP-RNA template.

Genomic replication promoter

The filoviral genomic replication promoters are not well studied - there is only experimental data available for EBOV and MARV. Both the MARV and EBOV genomic replication promoters are bipartite in nature [73, 74]. The first promoter element (PE) resides within the Le(−), which is 55 nucleotides in length for EBOV and 48 nucleotides for MARV, and is separated from the second PE by a short spacer region. For EBOV, the spacer consists of the GS signal of the first gene and the following 12 nucleotides (Fig. 5a). In the case of MARV, the two promoter elements are separated by the GS signal only (Fig. 5a). Whereas the sequence of the spacer is irrelevant, its length has to be divisible by six to allow efficient replication [73, 74]. The first PE has not been thoroughly mapped for any filovirus. Limited mutational analysis of the EBOV Le(−) showed that clusters of mutations affecting nucleotides 44–55 decreased replication activity in a minigenome system to non-detectable levels, indicating that this part of the Le(−) is important for replication [73]. Computer predictions suggest that marburgvirus, ebolavirus, and LLOV Le(−) regions adopt an internal hairpin structure (Fig. 5b). Since the first 13–23 nucleotides of the ebola- and marburgvirus genome termini show a high degree of complementary, the Le(−) has also the potential to form a panhandle structure with complementary sequences in the Tr(−) region [82, 83]. Formation of the internal leader hairpin was experimentally confirmed using in vitro transcribed MARV and EBOV Le(+) RNAs. For technical reasons, the analyzed RNAs were in positive sense orientation and not encapsidated with NP [73, 74]. Panhandle structure formation between the Le(−) and Tr(−) was observed using in vitro transcribed EBOV negative sense minigenome RNA. These studies were also performed with non-encapsidated RNA [83]. Mutations in the Le(−) hairpin region that interfered with stable secondary structure formation did not dramatically affect replication efficiency of EBOV minigenomes [82]. Also, clustered compensatory mutations of nucleotides 10–13 that changed the primary sequence but restored the secondary structure eliminated minigenome replication activity, indicating that secondary structure formation per se is not sufficient to support replication [73]. Together, these data suggest that formation of the internal Le(−) hairpin structure is not a prerequisite for efficient replication. Mutations in the Tr(−) region that affected panhandle structure formation with the Le(−) led to a decrease in minigenome activity and were prohibitive for viral rescue, indicating that the respective nucleotides in the Tr(−) are required for efficient replication [83]. Since the mutated nucleotides are also part of the antigenomic replication promoter located in the Tr(+) region of the antigenomes (see below, antigenomic replication promoter) and are involved in the interaction with cellular host factors that might promote viral replication [83], interpretation of these data is difficult.

Fig. 5. Filovirus genomic replication promoters.

(a) An alignment of the leader regions, initial gene start (GS) signals, and the untranslated regions (UTR) of the first gene of filovirus genomes was performed manually. GS signals are indicated in bold and underlined. Spacer regions in the ebolavirus promoters, located between the GS signal and the second promoter element, are indicated by outlined gray boxes. Hexamers in the second promoter element containing a uridine residue in the second position followed by two purines are indicated in yellow, while other hexamers containing a uridine in the second position are indicated in gray. Translation start anticodons are indicated by green boxes. The asterisks indicate experimentally determined replication promoter structures. (b) RNA secondary structures for the 3’ ends of the EBOV, MARV, and LLOV genomes, predicted using the RNAfold web server (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAWebSuite/RNAfold.cgi), are illustrated in negative sense RNA orientation. Numbers indicate the first and last nucleotide of the stem-loop structures. The LLOV sequence used in this analysis was appended with the four 3’ terminal nucleotides of the EBOV sequence (3’ GCCU). The second stem-loop structure is formed by the GS signal of the first gene, the NP gene, by base-pairing with downstream sequences. The location of the NP GS sequence in the stem-loop is marked in red. Abbreviations of virus names are explained in the legend to Figure 1.

The putative internal Le(−) hairpin could also serve a different purpose. Recent studies of the replication initiation mechanisms of EBOV, Sudan virus (SUDV), and RESTV revealed that regardless of the identity of the 3’ terminal nucleotide(s), the viral polymerase initiates replication accurately opposite the first C residue of a highly conserved motif (3’ CCUGUG) which is typically located at position 2 of the genomes and antigenomes, respectively [58] (Fig. 5a). Even if additional nucleotides are added to the 3’ end of the CCUGUG motif, the polymerase still initiates replication internally opposite the first C residue of this motif. If this C residue is replaced with a U residue (which reflects the 3’ end the MARV genome), replication is not initiated [58]. This unusual replication initiation mechanism leads to heterogeneous ebolavirus genome ends with a 3’ overhang that is not templated by the complementary strand. The 3’ overhang is usually a single G or A residue, but a small fraction of genomes and antigenomes has extended 3’ ends [58, 84]. A possible mechanism for the addition of the non-templated 3’ terminal nucleotide(s) is back-priming in which the 3’ end of the viral RNA folds into a hairpin structure and the internal RNA sequence is elongated by the viral polymerase [58]. So it is conceivable that the predicted internal Le(−) hairpin is utilized by the viral polymerase to add the non-templated 3’ nucleotide(s). This unusual heterogeneity of ebolavirus genome ends might help to avoid detection of viral RNA by cellular RNA sensors, such as RIG-I-like receptors, whose binding to double-stranded RNA is impaired by 3’ overhangs [85, 86].

The second PE of the EBOV and MARV replication promoters resides within the 3’ untranslated region (negative sense orientation) of the NP gene and consists of a stretch of nucleotide hexamers, three for MARV and eight for EBOV, in which every sixth nucleotide is a uridine residue, usually followed by two purine residues (NURRN2) (Fig. 5a). The minimal requirement for EBOV and MARV replication is a stretch of three of these hexamers with the EBOV promoter gaining strength when more hexamers are present [73, 74]. This unusual replication promoter structure is conserved among all marburg- and ebolaviruses and is also found at the 3’ end of the LLOV genome (Fig. 5a). Of note, a NURRN2 hexamer is also part of all filovirus GS signals with the exception of the fish filoviruses.

Thorough analysis of the promoter structures is not yet possible for some of the more recently discovered filoviruses, including MLAV, XILV, and HUJV, because of the lack of significant sequence information at both ends of their genomes [7, 9]). The LLOV Tr(−) region is also lacking significant sequence information [4]. The Le(−) and Tr(−) sequences of MLAV have not yet been published, but the first GS signal has a filovirus-typical structure, and the untranslated region of the MLAV NP gene contains a putative second PE (Fig. 5a). Although it appears that the GS signal for the first gene is present in the XILV genome, poor conservation of the the Le(−) and second PE leaves many questions (Fig. 5a). Does XILV have an extended Le(−) sequence? Or is the XILV Le(−) merely poorly conserved? Why is the proposed second PE so different? For this last question, there remains an intriguing possible explanation. When looking at the second PE of XILV, it contains only a single NURRN2 motif (Fig. 5a). It is noteworthy, however, that XILV has a somewhat divergent GS signal which does not include the NURRN2 sequence. Thus, it is conceivable that the XILV second PE contains other sequences that serve as elements of the viral replication promoter.

The only other NNS RNA virus family with a bipartite promoter structure are the paramyxoviruses [87–89]. In contrast to filovirus genomes, the length of paramyxovirus genomes is a multiple of six. This hexameric genome length results from each NP protomer in the NP-RNA complex interacting with exactly six nucleotides. Consequently, each nucleotide has a defined position within the binding groove of the NP protomers [89, 90]. This ability to precisely position the nucleotides in the NP-RNA complex determines the paramyxovirus promoter structure. The first PE has a minimum length of 12 nucleotides and is positioned at NP protomers 1 and 2 (starting from the 3’ end). The second promoter element is defined by the presence of one or two conserved nucleotides (usually C or GC) at the same position in three consecutive NP protomers. Proper spacing of the two PEs places them at the same vertical face of the NP-RNA helix [90].

Although marburg- and ebolavirus genome lengths are not a multiple of six, six seems to be a magic number for these viruses. The bipartite replication promoters follow the “rule of six”, and similar to the paramyxovirus nucleocapsids, each MARV and EBOV NP protomer interacts with six nucleotides in the NP-RNA complex (more detail in chapter 5). The length of the MARV Le(−) is divisible by six (48 nts) as is the length of the filoviral GS signals (12 nts). Although the ebolavirus Le(−) is not divisible by 6 (55 nts), the unusual replication initiation strategy excludes the first nucleotide from the promoter, making the part of the Le(−) region that is accessed by the polymerase divisible by six (54 nts) (Fig. 5a) [58].

Antigenomic replication promoter

The filoviral antigenomic replication promoters are poorly defined. Per definition, they are located at the 3’ end of the antigenomes and are complementary to the 5’ ends of the genomes. Sequence comparison suggests that the overall structure of the antigenomic and genomic replication promoters is similar [73, 74]. Indeed, EBOV defective interfering copy-back type particles and copy-back MARV minigenomes in which the leader region was replaced with a complementary copy of the trailer were readily replicated [47, 77]. Removal of the first 25 nucleotides of the EBOV Tr(+) region (i.e. the last 25 nucleotides of the genome) reduced replication activity of negative sense minigenomes to a single round, confirming that these nucleotides are an essential part of the antigenomic promoter [58, 76]. The single-round replicating minigenomes were still able to initiate replication and transcription from the genomic promoter, indicating that the trailer region is not required for these processes. Rescue of full-length EBOV clones lacking the last 56 nucleotides of the genome was not successful, confirming the importance of this region for viral replication [83]. Similar to the Le(−) regions, the Tr(+) regions are also predicted to form RNA secondary structures, resulting either in internal Tr(+) hairpins or in panhandle structures formed with complementary regions in the Le(+) [82, 83, 91, 92]. It is likely that the filoviral antigenomic replication promoters are also bipartite in nature as the 3’ ends of the marburg- and ebolavirus antigenomes contain clusters of hexameric NURRN2 motifs downstream of Tr(+) [73].

An important difference between the genomic and antigenomic promoters is that the antigenomic promoters do not drive transcription. Studies on the replication promoters of other NNS RNA viruses revealed that the antigenomic promoters are stronger than the genomic promoters, leading to more efficient amplification of the genomic RNA during replication. This difference in promoter strength can be attributed to two mechanisms: firstly, nucleotide differences between the genomic and antigenomic promoter regions and secondly, competing replication and transcription activity at the genomic promoter [93–96]. There are currently no comparative studies on the relative strength of the filoviral genomic and antigenomic promoters. It has been shown, though, that transcription-deficient MARV minigenomes replicate more efficiently than transcription-competent minigenomes, supporting the idea of competing replication and transcription activity at the genomic promoter [74].

4.2. cis acting elements involved in filovirus transcription

Transcription promoter

The structure of the filoviral transcription promoters has not been elucidated yet, but analogous to other NNS RNA viruses, it must be located in the Le(−) region, upstream of the first GS signal. Indeed, MARV copy-back minigenomes, in which the leader region including the first GS signal has been replaced by a complementary copy of the trailer, are replicated but not transcribed [47]. Similarly, deletions in the trailer region abolish antigenome replication, but do not affect transcription [75, 76]. Since there is a single entry site for the polymerase at the 3’ end of the genome, the polymerase cannot initiate transcription internally if it falls off the template. For this reason, the promoter-proximal genes are more frequently transcribed than the promoter-distal genes, leading to a transcription gradient (Fig. 3) [97, 98].

Gene start (GS) signals

With the possible exception of a single LLOV bicistronic gene, each filovirus gene is flanked by conserved GS and GE signals (Figs. 1b and 6a). After the polymerase has accessed the NP-RNA template at the 3’ end, it scans the genome sequence for the first GS signal to initiate transcription of the first gene. The first nucleotide of all filoviral GS signals is a cytidine residue, and consequently all filoviral mRNAs start with a guanosine (Fig. 6a). This seems to be important for mRNA capping (see chapter 5.4, Transcription-specific functions of L). The 12-nucleotide stretch that comprises the GS signals of most of the filoviruses is fairly well conserved (Fig. 6a). A unique feature of filovirus GS signals is that they are predicted to adopt RNA hairpin structures [97, 99]. With the exception of the hairpin formed by the GS signal of the EBOV NP gene (Fig. 5a; see chapter 5.4, The role of VP30 in filovirus transcription), it remains to be determined if these RNA secondary structures are of functional relevance.

Fig. 6. Filovirus gene start and end signals, and gene borders.

(a) Alignments of all gene start (GS) and gene end (GE) sequences of the indicated viruses were performed using Clustal Omega. Logo plots were created using WebLogo version 2.8.2 (https://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi). Sequences are shown in negative sense orientation, with five additional nucleotides downstream and upstream of the GS and GE signals, respectively. For the fish filoviruses, GS and GE borders we predicted based on homology to corresponding sequences in the other filoviruses, with the exception of the HUJV GS signals which were predicted by identifying a similar sequence found upstream multiple genes, (b) Gene borders in filovirus genomes. Gene borders with overlapping GS-GE sequences are indicated with “overlap” (in red), gene borders with intergenic regions (IRs) are indicated with the length of the IRs (short IRs in orange, intermediate IRs in blue, and long IRs in green), and gene borders with unclear or possibly lacking GS or GE sequences are indicated with “unclear” (gray). The EBOV VP24 gene has two GE signals, resulting in two different gene borders (VP24-L and VP24-L alt.). As the GS sequences for HUJV are speculative and divergent from the other filoviruses, the proposed gene borders are indicated with the length of the IR colored as the other IRs with a question mark. Examples of overlapping gene borders are also shown. Filovirus overlapping gene borders are all structured similarly: these overlaps begin with the GS signal of the downstream gene (green line), followed by an overlap region consisting of the end of the GS signal and the beginning of the GE signal of the upstream gene (overlap sequence colored in red), and are followed by the end of the GE signal (red line). The EBOV VP35-VP40 gene border is shown as a representative of mammalian filovirus gene border overlaps. The XILV VP35-VP40 gene border is shown as a representative of XILV gene border overlaps. Abbreviations of virus names are explained in the legend to Figure 1.

The consensus sequence of the GS signal for ebolaviruses, marburgviruses, LLOV, and MLAV is 3’ C1UNCUUN7UAAUU12. The main difference between these sequences is that ebolaviruses have a preference for a cytidine residue at position 7 in this motif, whereas the marburgviruses, LLOV, and MLAV prefer a purine residue (Fig. 6a). Despite significant differences in sequence and genome organization, XILV has a fairly similar GS sequence of 3’ C1UUCCCG7UUAUU12. In contrast, nothing resembling the conserved filovirus GS signals, including the XILV GS signals, is present upstream any of the HUJV ORFs. Computer-assisted search of the HUJV noncoding regions for conserved motifs identified a highly conserved 14 nucleotide sequence upstream of the NP ORF, ORF3, and the GP ORF (3’ C1GGGUUUNUANUAU14; Fig. 6a). Somewhat similar sequences are observed upstream of ORF5 and the L ORF, although differences are noteworthy. A lack of this motif upstream of ORF1 could be due to missing sequence at the 3’ end of the genome.

Gene end (GE) signals

After transcription initiation and capping, the polymerase moves along the template and elongates the mRNA until it reaches the first GE signal. The GE signals are highly conserved across the different filoviral genera and end with a stretch of 5–6 uridine residues (Fig. 6a). These induce stuttering of the polymerase, leading to the addition of a poly(A) tail at the 3’ end of the mRNAs [100]. There are few variations in the filoviral GE signals, including in the highly divergent fish filoviruses (Fig. 6a).

Gene borders and intergenic regions (IRs)

Filovirus transcription follows the typical stop-start mechanism of NNS RNA viruses. After terminating transcription at the GE signal of the upstream gene, the polymerase scans for the GS signal of the next gene. The EBOV polymerase is able to scan for GS signals in both directions of the GE signal [62]. Most of the filoviral GS and GE signals contain a conserved 3’ UAAUU pentamer, allowing for gene overlaps in which the 3’ UAAUU sequence is shared by the GS signal of the downstream gene and the GE signal of the upstream gene, requiring the polymerase to scan slightly upstream of the GE signal for the next GS signal (Fig. 6a and b). For XILV, this conserved sequence is one nucleotide different; a 3’ UUAUU pentamer is conserved in all GS and GE signals. Although the HUJV GE signals contain a conserved UAAUU pentamer, this sequence is not present in the putative HUJV GS signals, suggesting that typical filoviral gene overlaps cannot occur (Fig. 6a and b). The gene overlaps are as efficient in transcription initiation and termination as the GS and GE signals that are separated by IRs [62]. While the marburg- and ebolavirus genomes contain one to three gene overlaps, the MLAV and LLOV genomes contain four, and XILV takes it to the extreme with all genes overlapping (Fig. 6b). It seems that the VP24 and L ORFs of LLOV are not separated by GE and GS signals, indicating that VP24 and L are produced from a single mRNA (Fig. 6b) [4]. The mechanism by which such a bicistronic transcript could serve as a template for the expression of both genes remains unclear.

While some of the filovirus genes overlap, others are separated by diverse IRs which vary both in length and sequence. Except a single long IR in each of the ebola- and marburgvirus genomes (97–149 nts), the IRs are quite short (4 to 9 nts) (Fig. 6b). The non-overlapping gene borders for LLOV and MLAV are also short, with no long IRs (Fig. 6b). Based on the proposed GS signals in the HUJV genome, there would be no overlapping genes. All genes would be separated by IRs of short (4 nts) and intermediate (14 and 27 nts) length IRs (Fig. 6b).

Mutational analysis of the EBOV IRs indicated that they are involved in transcription regulation. However, the main regulators of transcript levels are the untranslated regions of the viral genes [61–63, 101]. If the viral polymerase fails to recognize the GS and GE signals, this leads to the production of readthrough mRNAs which are present in EBOV- and MARV-infected cells [63, 98]. Readthrough transcription occurs independently of the structure of the gene borders. The sequential transcription of the viral genes is highly regulated. If the polymerase is unable to terminate transcription of a gene because the GE signal is destroyed, it cannot reinitiate transcription at the following gene, even if the GS signal of this gene is intact [62].

4.3. Untranslated regions (UTRs)

The ORFs of filoviral genes, particularly the mammalian filovirus genes, are flanked by unusually long untranslated regions (UTRs) (Fig. 1b). The upstream UTRs of the EBOV, LLOV, MARV, and MLAV genes are on average 214, 275, 131, and 157 nts in length, and the average length of the downstream UTRs is 298, 372, 476, and 399 nts, respectively. In analogy to cellular mRNAs, it is conceivable that the filoviral UTRs play a regulatory role at mRNA level, for example in mRNA stabilization and translation. Indeed, the 5’ UTR of the EBOV L mRNA encodes a small, upstream ORF (uORF) that overlaps with the L ORF. This uORF controls L translation by diminishing ribosome initiation at the L AUG start codon. However, in the event of cellular stress, when translation of capped mRNA is impaired, the uORF is required to maintain translation of the L mRNA [101]. Meanwhile, the UTRs of the fish filoviruses are conspicuously shorter, with the downstream UTRs of XILV ORF8 and HUJV ORF3 as well as the upstream and downstream UTRs of the HUJV GP gene being the exceptions (Fig. 1b).

5. Filovirus replication and transcription

5.1. Nucleocapsid

A common feature of all NNS RNA viruses is that naked viral RNA is not accepted as a template for replication and transcription [45]. Only viral genomes and antigenomes that are complexed with the viral nucleocapsid proteins, forming the helical nucleocapsid, are recognized as templates for viral RNA synthesis and, in the case of the genomes, will be packaged into virions. Five of the seven marburg- and ebolavirus structural proteins are associated with the nucleocapsid. These are NP, VP35, VP30, VP24, and L [14, 19–21, 40, 102–105]. An overview of the multiple interactions of these proteins is provided in [106]. Though not identical, the MARV and EBOV nucleocapsids show striking architectural homology. The core of the nucleocapsids is a left-handed NP-RNA helix (Fig. 7a). VP35 and VP24 are required for the formation of complete nucleocapsids in addition to NP (Fig. 7b, right and c). The mature EBOV nucleocapsids have an average pitch of 74 Å and 11.9 or 12.9 subunits per turn and are slender and longer than the MARV nucleocapsids which have an average pitch of 77 Å and 14.8 or 15.8 subunits per turn [22].

Fig. 7. Cryo-EM reconstructions of the EBOV and MARV nucleocapsids.

(a) Cryo-EM reconstruction of the EBOV NP-RNA helix using a truncated version of NP (NP1-450 + RNA). Single NP molecule in orange, RNA in red. Scale bar, 20 Å. Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature: Nature 563(7729):137–140, Cryo-EM structure of the Ebola virus nucleoprotein-RNA complex at 3.6 Å resolution, Sugita, Y., Matsunami, H., Kawaoka, Y., Noda, T., and Wolf, M., © authors, 2018. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-018-0630-0. (b) Comparison of cross-sections of EBOV nucleocapsid-like structures. Left, structure of purified EBOV NP1-450 helices; right, structure of EBOV VLPs produced in cells expressing NP, VP24, VP35, and VP40. In light gray are two nucleocapsid subunits. Scale bars, 50 Å. Adapted from Extended Data Fig. 7 in [22]. Courtesy of John Briggs, MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, UK. (c) Structure of EBOV and MARV nucleocapsids from intact viruses. i, iv, Visualizations of the EBOV (i) and MARV nucleocapsid helix (iv) as determined by subtomogram averaging. Adjacent rungs are in dark and light gray; a single subunit is highlighted in pink. ii, v, Subunit densities of EBOV (ii) and MARV nucleocapsids (v). NP densities are in cyan and blue, the small outer protrusions are in orange, and the large outer protrusions in purple. Green density is extra disordered density in the MARV nucleocapsid. Gray densities show other subunits on the same rung; densities from adjacent rungs are transparent. RNA density is in yellow. iii, vi, Molecular models of NP and VP24 fitted into the EM densities of EBOV (iii) and MARV nucleocapsid subunits (vi). The two NP models are in blue and cyan while the two VP24 models are shown in orange and purple. Scale bars, 20 Å. Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature: Nature 551(7680):394-397, Structure and assembly of the Ebola virus nucleocapsid, Wan, W., Kolesnikova, L., Clarke, M., Koehler, A., Noda, T., Becker, S., and Briggs, J. A. G., © authors, 2017. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature24490.

Because viral particles for any of the new members of the filovirus family have not yet been isolated, the virion structures are not known. However, based on gene homology, it is very likely that the composition of the BOMV, LLOV, and MLAV particles is similar to that of the known filoviruses, whereas it is difficult to predict the structures of XILV and HUJV particles because of considerable differences in their gene composition (Fig. 1b and chapter 7).

5.2. Filovirus proteins involved in RNA synthesis

Using minigenome systems that allow the separation of genome replication and transcription, it was shown that three nucleocapsid proteins, NP, VP35, and L, are sufficient to mediate MARV and EBOV replication (Fig. 3). NP encapsidates the viral RNA to form the template for the polymerase complex composed of L, the catalytic subunit of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and its cofactor VP35 [38, 47, 48, 107].

NP

All NNS RNA viruses have a helical nucleocapsid with an NP-RNA core. NP-RNA complex formation is driven by NP self-aggregation [108, 109]. This is also true for filoviruses. Both NP aggregation and NP-RNA complex formation are mediated by the amino-terminal parts of EBOV NP (aa 1–450; total length: 739 aa) and MARV NP (aa 1–390; total length: 695 aa) [14, 19, 21, 110–115] (Fig. 7a and b, left). Crystal structure and high-resolution reconstruction analyses provided a deeper insight into the structure of the EBOV and MARV NP-RNA complexes [22, 114–120]. The amino-terminal NP core folds into two lobes. Self-assembly of the NP core leads to the formation of a left-handed helical tube. The RNA cleft is located on the outside of the NP helix between the N- and C-terminal lobes (Fig. 7a). Each NP protomer in the helix interacts with 6 nucleotides [14, 21, 116]. This interaction occurs through hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions between the NP core and the RNA backbone, and is RNA sequence-independent [116].

VP35

The NP-RNA complex alone is not a functional template for genome replication. Both EBOV and MARV NPs interact with the polymerase cofactor VP35 which is the homolog to the phosphoproteins (P) of other NNS RNA viruses [114, 115, 118, 119, 121]. VP35-NP interaction is not only required for nucleocapsid formation but is also crucial for viral RNA synthesis. Similar to the NNS RNA virus P proteins, VP35 forms homo-oligomers (trimers in the case of MARV, and trimers and tetramers in the case of EBOV) through a coiled-coil motif located in the N-terminal part of the protein [122–125]. Homo-oligomerization is essential for VP35’s function in replication and transcription [123, 126]. Both EBOV and MARV VP35 proteins interact with the catalytic polymerase subunit L to form the functional polymerase complex [103, 107, 121, 126, 127]. It is believed that VP35 serves as a bridge to connect L with the NP-RNA complex [103, 127]. VP35 also interacts with NP to keep it in a monomeric, RNA-free state [114, 115, 118, 119]. This chaperon function of VP35 might help to prevent premature and unspecific RNA binding (cellular RNA instead of viral RNA), or it might be used as a mechanism to temporarily unpack the viral RNA template to make it available to the polymerase complex. The NP binding domain within VP35 that facilitates NP chaperoning is conserved among all filoviruses [115] with the exception of XILV and HUJV (Fig. 8b). This is perhaps not surprising given the weak homology of XILV VP35 to other filovirus VP35 proteins and the lack of a clear VP35 homology in HUJV (Figs. 1b and 9). For more information regarding possible VP35 functional homologs in XILV and HUJV, see chapter 7.

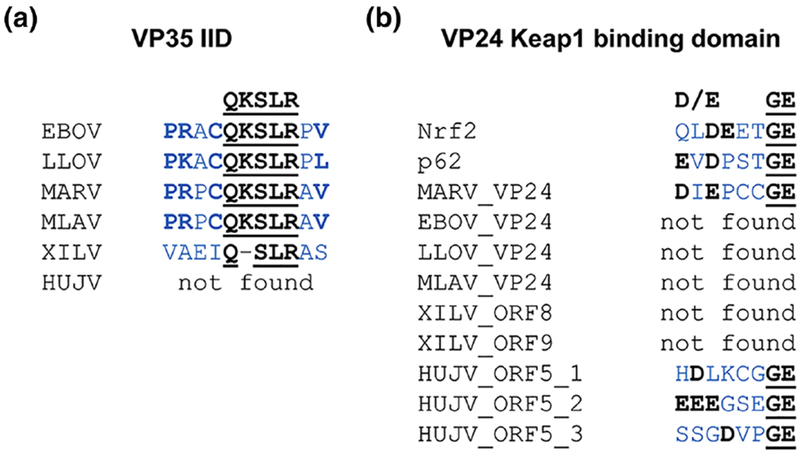

Fig. 8. Conserved regions in filovirus proteins.

Alignments of key conserved motifs in filovirus proteins involved in replication and transcription, (a) NP, (b) VP35, (c) VP30, and (d) L, were performed manually. Alignment of the L protein motifs include similar motifs in the L proteins of other NNS RNA viruses. Motif names or functions are indicated above. Critical residues of conserved filovirus motifs are shown above alignments and are indicated in bold and underlined. Similar amino acids to the conserved motifs are in black but not bold or underlined and dissimilar amino acids are in gray. Surrounding amino acids not part of the consensus sequence are in blue with conserved sequences in bold. Amino acids highlighted in magenta and blue indicate a divergence between the mammalian filoviruses and the other NNS RNA viruses, including XILV and HUJV. Sequences in which no similar motifs were found are indicated with “not found”. Instances where similar motifs were found in different proteins (e.g. in (c)), are indicated by including the divergent viral gene name. Instances where multiple potential motifs were identified in the same protein are indicated with an underscore and number. Abbreviations of filovirus names are explained in the legend to Figure 1. BDV, Borna disease virus; HeV, Hendra virus; MV, measles virus; NDV, Newcastle disease virus; NiV, Nipah virus; PRNTase, GDP polyribonucleotidyl-transferase; RABV, rabies virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SAM, S-adenosyl-methionine; VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus.

Fig. 9. Conserved domains in XILV and HUJV proteins.

XILV and HUJV proteins were searched for homology to other filovirus proteins and for the presences of key conserved domains that are known to be important for different aspects of filovirus replication. Domain searches were performed using protein BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE=Proteins), ELM (http://elm.eu.org/), Paircoil2 (http://cb.csail.mit.edu/cb/paircoil2/paircoil2.html), ScanProsite (https://prosite.expasy.org/scanprosite/), SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/). and manually. Each (a) XILV and (b) HUJV gene is listed with the discovered domains, including the location of the domain as indicated by amino acid number, and any predicted or suggested homology to ebola- and marburgvirus proteins. Proteins are colored as in Figure 1, with the exceptions of HUJV 0RF3 and 0RF5 which are here colored similarly to VP35 and VP30, respectively. Abbreviations of filovirus names are explained in the legend to Figure 1. MTase,methy ltransferase.

L

The catalytic subunit of the viral polymerase, L, interacts with VP35 to form the functional polymerase complex [47, 48, 103, 121, 126, 127]. Though associated with the nucleocapsid, L is not required for nucleocapsid formation, but it is indispensable for replication and transcription. The VP35 binding site resides within the amino-terminal part of L [103, 121, 126, 127]. EBOV L also interacts with VP30 [128], but VP30 is not required for RNA synthesis activity [107]. EBOV L has also the potential to homo-oligomerize [127]. Similar to the L proteins of other NNS RNA viruses, the filovirus L proteins have various enzymatic activities required for RNA synthesis and mRNA processing that are contained within six conserved regions (I-VI) [91, 92, 129–131]. Cryo-EM structure analysis of the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) L showed that the protein is organized in distinct domains; the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase domain (contains regions I-III), the capping domain (contains regions IV and V), the connector domain, the methyltransferase domain (region VI), and a carboxy-terminal domain that is variable among the NNS RNA viruses [132]. The catalytic center of the RNA polymerase domain contains a highly conserved GDN motif. Amino acid exchanges within this motif render the polymerase inactive, as shown for EBOV, RESTV, and MARV L [51, 54, 107, 130, 133]. A recently established in vitro polymerase assay for EBOV showed that the polymerase uses Mg2+ ions as catalytic cofactors for RNA synthesis. The aspartic acid of the GDN motif within the catalytic domain likely coordinates the interaction with the metal ions [107]. The amino acid sequences surrounding the active center are identical in most filovirus L proteins except for the fish viruses, which appear to be more similar to other NNS RNA viruses (Fig. 8d, Catalytic domain (GDN motif)). Another domain of the L protein found in all filoviruses is the KEKE motif (Fig. 8d, Template binding), which is involved in positioning and binding of the RNA template [92, 129, 134], and is also conserved across the filoviruses. All NNS RNA viruses encode L, and it is the best conserved protein among these viruses [129, 135].

Negative regulators of viral RNA synthesis: VP24 and VP40

VP24 is the only filovirus protein for which there is no homolog among the other NNS RNA viruses and, intriguingly, there does not appear to be a VP24 homolog in the fish filoviruses either (Fig. 1b). For a long time, the function of VP24 was obscure, and it was considered to be a minor matrix protein. It is now known that VP24 plays a crucial role in the formation of mature, transport-competent nucleocapsids [23–25, 136]. In addition to NP and VP35, VP24 is an essential structural component of the nucleocapsid complex and indispensable for the assembly of rigid and condensed nucleocapsids [19–21, 24, 137] (Figs. 3 and 7b and c). VP24 is not required for genome replication and transcription which implies that there is a structural difference between replication-competent nucleocapsids that lack or contain only small amounts of VP24 and condensed nucleocapsids that contain VP24 [66, 138]. A model based on cryo-electron tomography and subtomogram averaging suggests that the NP-RNA helix in a semi-condensed state recruits VP24 and VP24-VP35 to complete condensation [22]. According to this model, the NP:VP24:VP35 stoichiometry in the condensed nucleocapsids is 2:2:1, whereby VP24 and VP24-VP35 form alternating small and large protrusions [14, 21, 22] (Fig. 7b, right and c).

Overexpression of VP24 in MARV, EBOV, and LLOV minigenome systems had a negative effect on minigenome activity [52, 64, 75, 139]. This inhibitory effect is likely due to premature VP24-driven nucleocapsid condensation which interferes with the movement of the polymerase along the RNA template [66]. The MARV and EBOV VP40 matrix proteins have also been shown to block minigenome activity [64, 75, 140] (Fig. 3). The role of VP24 and VP40 in viral RNA synthesis has not been studied for other filoviruses.

VP30

The fifth viral protein associated with marburg- and ebolavirus nucleocapsids is VP30 [102, 103]. Its function during viral transcription is discussed in chapter 5.4, The role of VP30 in filovirus transcription.

5.3. Inclusions

The marburg- and ebolavirus nucleocapsids form large inclusions in the infected cells. These viral inclusions are the sites of viral RNA synthesis, nucleocapsid formation, and nucleocapsid maturation [13, 35, 40, 41, 43, 44, 141, 142]. Inclusion formation in infected cells has also been observed for other NNS RNA viruses. Recent work on viral inclusions in rabies virus- and VSV-infected cells shows that the viral inclusions have the characteristics of liquid droplets formed by phase separation, similar to stress granules, P bodies, and other cellular RNA-protein complexes [143, 144]. Given that EBOV inclusions show some of the features characteristic of liquid organelles as observed by live-cell imaging (e.g. they fuse and form larger spheres) [35], it is tempting to assume that the filovirus inclusions, too, are distinct liquid organelles. However, this has not yet been experimentally shown. In EBOV infected cells, cellular proteins involved in RNA regulation and translation form distinct granules that are sequestered within the viral inclusions, but are separate from them, supporting the idea of liquid-liquid phase separation [42]. The functional relevance of these inclusion-bound granules is not clear. It is not known whether the sequestration of distinct cellular protein granules is unique for ebolaviruses or also occurs during infection with other filoviruses. Similar to MARV and EBOV, the LLOV nucleocapsid proteins form inclusions when expressed in cells [51]. Given the high degree of similarity regarding the genome organization and encoded viral proteins of filoviruses (with exception of the fish filoviruses), it is likely that both filoviral nucleocapsid structure and inclusion formation are conserved. The fish filoviruses are clearly distinct from the other filoviruses; neither encodes a homolog to VP24, and HUJV additionally does not encode clear homologs to VP35 or VP30 (Figs, 1b and 9). It would be highly interesting to explore if the differences in the genome organization of these viruses are also reflected in significant structural and functional differences compared to the more “conventional” mammalian filoviruses, including whether these viruses form inclusions upon infection.

5.4. Transcription-specific functions of filoviral proteins

While the protein requirements for viral genome replication and transcription overlap, there are also some key differences, including differences between the filovirus genera. Similar to filovirus genome replication, transcription requires encapsidation of the genome by NP. In addition to VP35 and L, the transcription factor VP30 is involved in filovirus transcription, although there are significant differences in the requirement for VP30 between the different filovirus genera. Nothing is yet known about XILV and HUJV transcription.

Transcription-specific functions of L

Shortly after transcription initiation, the nascent mRNA chain is capped by the viral polymerase [145]. Although EBOV mRNAs are capped [59], there is not much known about the filoviral capping mechanisms. The L protein of the closely related VSV uses an unconventional mechanism to add the m7Gppp cap to the 5’ ends of the viral mRNAs which involves various enzymatic activities, including a guanosine 5-triphosphatase, a GDP polyribonucleotidyl-transferase (PRNTase), and a dual methyltransferase (MTase) activity [135, 146, 147]. The PRNTase activity depends on a His1227-Arg1228 (HR) amino acid motif in domain V of VSV L that is also found in the L proteins of other NNS RNA viruses, including all filoviruses, suggesting that the unusual VSV capping mechanism is conserved among NNS RNA viruses (Fig. 8d, PRNTase) [146]. The MTase domain, which is another conserved activity of most NNS RNA virus polymerases, includes a GxGxG motif and catalytic K-D-K-E tetrad [148], and is found in all filoviral L proteins (Fig. 8d, SAM binding domain and MTase tetrad (K-D-K-E)). Functional analysis of the MTase activity of filoviral L has only been performed for SUDV L. The C-terminal domain of SUDV L containing region VI is able to transfer methyl groups to the guanine N7 position of the cap when RNA substrates are used that start with a 2’O-methylated guanosine residue. However, substrates starting with methylated adenosine residues are not accepted [131]. This matches beautifully with the conserved filovirus GS signals – all filovirus mRNAs start with a guanosine residue (Fig. 6a). SUDV L is also able to methylate the ribose 2Ό position of the first guanosine residue of the RNA substrate, but only if the substrate is longer than 30 nts [131]. This is reminiscent of VSV for which it was shown that capping only occurs when the nascent mRNA reaches a length of 31 nts [149]. Martin and colleagues propose the following model: SUDV transcription starts with the synthesis of an approximately 30-nt long uncapped transcript which remains bound to the PRNTase domain until the non-methylated cap guanosine is added. Following addition of the guanosine cap to the nascent RNA, two methyl groups are added to the cap by the MTase domain of L. The GxGxG motif within the MTase domain binds S-adenosyl-L-methionine which is the source of the methyl groups added to the guanosine RNA cap. The first methylation step, 2Ό methylation of the first nucleotide of the nascent mRNA (GpppGm), is catalyzed via the surrounding K-D-K-E tetrad. Following 2Ό methylation, N7 methylation of the cap guanosine (mGpppGm) is mediated by the same MTase domain [131]. In addition to cap methylation, SUDV L has an unconventional internal adenosine-specific 2O-MTase activity that is cap-independent and might play a role for epigenetic control mechanisms or RNA packaging [131].

RNA editing

Ebolaviruses increase the coding capacity of the GP gene by cotranscriptional editing, resulting in the synthesis of multiple GP mRNA species [150–153]. The editing site within the GP gene contains a stretch of seven uridine residues that are transcribed into adenosine residues during transcription. The full-length membrane-bound GP1,2 is only expressed if an additional, non-templated adenosine residue is incorporated into the nascent mRNA strand (8A version), resulting in a frame shift [150, 151]. If the mRNA is not edited (7A version), a soluble form of GP, sGP, is expressed that lacks the membrane anchor [154]. It has been suggested that GP mRNA editing is required for downregulating GP1,2 expression in order to reduce its cytotoxic effects [69, 155]. The 7U stretch is also used as a cryptic transcription termination and polyadenylation site. About 40% of the synthesized EBOV GP mRNAs are prematurely terminated at the 7U stretch [156]. Approximately a quarter of the remaining 60% of the mRNAs contain a single non-templated adenosine residue, resulting in GP1,2 expression [150, 152]. A mechanistic study on EBOV editing revealed that VP30 is involved in this process. According to the proposed model, an RNA hairpin is formed upstream of the editing site in the nascent GP mRNA, leading to polymerase stuttering. VP30 is required to overcome this hairpin, similar to its proposed function during transcription initiation at the NP gene GS signal (see below, The role of VP30 in filovirus transcription) [157].

Editing is not restricted to mRNA synthesis but also occurs during EBOV replication. A common cell culture adaptation is the insertion of a uridine residue at the GP gene editing site (8U mutant) that leads to predominant expression of membrane-bound GP1,2 and increased cytotoxicity [155, 158, 159]. This 8U cell culture adaptation was also observed for SUDV [153]. Intriguingly, the 8U mutant reverts back to the 7U wildtype in animal models of EBOV infection [153, 158, 159]. Follow-up studies showed that recombinant EBOV clones overexpressing GP1,2 were attenuated in a guinea pig infection model, possibly due to GP1,2-induced premature cell death. This suggests that controlled GP1,2 expression is an important virulence factor in EBOV infection [155]. The reversion back to the 7U wildtype was less pronounced in a nonhuman primate infection model for SUDV, indicating that the different ebolavirus species might use distinct strategies to modulate GP expression [153].

Besides the ebolaviruses, only LLOV uses mRNA editing to express membrane-bound GP1,2 [33, 34]. The GP ORFs of marburgviruses, MLAV, and the fish filoviruses are open and each only encode a single version of GP1,2 that does not require transcriptional editing (Fig. 1b). While RNA editing has mostly been studied in the context of EBOV, a recent deep sequencing analysis of RNA from cells and non-human primates infected with MARV Angola revealed novel editing sites in the NP and L ORFs, potentially resulting in novel forms of these proteins [98]. It is currently unknown whether cotranscriptional editing is a pan-filovirus feature or if it is only conserved within a subset of the filovirus family.

The role of VP30 in filovirus transcription

Marburg- and ebolavirus VP30 proteins share some structural and functional features with the M2–1 proteins of the pneumoviruses but are not found in other NNS RNA viruses [160–163]. As mentioned above, they are associated with the nucleocapsid [102, 103]. While MARV and EBOV have the same protein requirements for genome replication, there are differences in the transcription strategies of these viruses regarding VP30 as outlined below.

The role of Ebola virus VP30 in transcription

In addition to NP, VP35, and L, ebolavirus transcription requires the transcription activator VP30 (Fig. 3) [48–50]. EBOV VP30 is a single-stranded RNA binding protein that forms hexamers and interacts with NP, VP35, and L [105, 128, 164–171]. It contains an unusual C3H1 Zinc binding motif that is required for transcriptional activity and RNA binding [166, 168, 172]. Although VP30 is tightly associated with the nucleocapsid complex, it is not essential for nucleocapsid formation [14, 21]. VP30 is involved in various steps of EBOV transcription. During transcription initiation of the first gene, the NP gene, VP30 is required to overcome an RNA hairpin structure adopted by the NP GS signal with downstream located sequences (Fig. 5b). Disruption of this secondary structure renders EBOV minigenome transcription VP30-independent [59, 171]. If transcription does not proceed beyond the first GS signal, none of the other viral mRNAs can be synthesized. It has been proposed that VP30 forms a ternary complex with the Le(−) RNA and the EBOV polymerase through interaction with VP35 to stabilize the transcription initiation complex and prevent the polymerase from falling off the template due to destabilization caused by the RNA hairpin [168]. VP30 is also involved in later steps of the viral transcription cycle [173, 174]. It has been proposed that it acts as a reinitiation factor at the internal gene boundaries [174]. However, transcription reinitiation in a bicistronic minigenome system occurred independently of VP30, although the internally located GS signals are also predicted to adopt hairpin structures [59]. It has also been suggested that VP30 is involved in the switch from transcription to replication [167, 173]. Finally, VP30 is required for GP mRNA editing, as described above in the mRNA editing section [157]. The transcriptional activity of EBOV VP30 depends on its phosphorylation state (Fig. 3). Phosphorylation of VP30 occurs at serine and threonine residues mainly located in the N-terminal domain of the protein [164, 175]. Non-phosphorylated or hypo-phosphorylated VP30 enhances transcription, whereas the phosphorylated form is transcriptional inactive. Phosphorylation of VP30 interferes with its ability to interact with NP, VP35, and RNA, and excludes VP30 from the transcription complex. This leads to enhanced replication activity which can be carried out without VP30 (Fig. 3) [167, 168, 176]. The presence of hypo-phosphorylated VP30 is crucial for the EBOV replication cycle. Intriguingly, NP recruits the cellular phosphatase PP2A-B56 through a B56 binding motif (Fig. 8a, PP2A-B56 binding domain). This leads to VP30 dephosphorylation and transcriptional activitation [177]. The PP2A-B56 binding domain within NP is conserved in all the filoviruses, with the possible exception of HUJV which does not encode a clearly identifiable VP30 homolog. Blocking the activity of cellular phosphatases involved in VP30 dephosphorylation has therapeutical potential because hyper-phosphorylated VP30 is transcriptional inactive. Indeed, phosphatase inhibitors interfere with EBOV replication [164, 175, 177].

Crystal structure analysis showed that the C-terminal domain of VP30 interacts with a peptide within the C-terminal domain of NP [105, 170, 171]. This interaction is crucial for VP30 activity and seems to be highly regulated. Mutational analysis in one study suggested that the VP30-NP binding affinity has to be in an optimal range. Mutants that resulted in too high or too low binding affinities did not perform well in the minigenome system [170]. Another study suggested that even minimal VP30-NP binding is sufficient to support transcriptional activity. This study also showed that the NP-VP30 interaction is required for the early activities of VP30 which are to overcome the RNA hairpin structure at the first GS signal [171]. The VP30-interacting peptide in NP contains a PPxPxY motif that is conserved across all mammalian filoviruses (Fig. 8a, VP30 binding) [170, 171]. The cellular ubiquitin ligase RBBP6 contains the same binding motif and is able to sequester VP30, leading to reduced transcriptional activity [178]. As for the fish filoviruses, XILV NP contains a handful of slightly less conserved VP30-binding motifs, and HUJV NP lacks any similar motif (Fig. 8a, VP30 binding). The absence of these motifs in HUJV NP is perhaps not surprising since the virus lacks a clear VP30 homolog.

The role of Marburg virus VP30 in transcription

Although there is a high degree of structural homology between MARV and EBOV VP30 proteins, the role of VP30 in MARV transcription is less clear. Similar to EBOV VP30, MARV VP30 is phosphorylated and binds to NP and VP35 [103, 104, 170, 179]. While VP30 is an essential component of the EBOV minigenome system and enhances transcriptional activity at least 50-fold, MARV VP30 is dispensable for minigenome activity and increases reporter gene activity only moderately [47, 64, 133, 179]. Despite this difference in the minigenome systems, MARV VP30 is essential for viral gene expression and for the rescue of full-length viral clones [70, 180]. Similar to EBOV VP30, the phosphorylation state of MARV VP30 determines its function in the minigenome system, and treatment of MARV-infected cells with phosphatase 1 inhibitors reduced viral titers [179]. Crystal structure analysis revealed a striking conformational similarity of the EBOV and MARV VP30-NP complexes [170]. Interestingly, the binding affinity of the MARV VP30-NP complex is lower compared to EBOV [170]. It remains to be determined whether this difference has functional consequences.

6. Replication and transcription of novel filoviruses