Abstract

Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP) is characterized by recurrent transient peripheral vasospasm and lower nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability in the cold. We investigated the effect of nitrate-rich beetroot juice (BJ) supplementation on 1) NO-mediated vasodilation, 2) cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC) and skin temperature (Tsk) following local cooling, and 3) systemic anti-inflammatory status. Following baseline testing, 23 individuals with RP attended four times, in a double-blind, randomized crossover design, following acute and chronic (14 days) BJ and nitrate-depleted beetroot juice (NDBJ) supplementation. Peripheral Tsk and CVC were measured during and after mild hand and foot cooling, and during transdermal delivery of acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside. Markers of anti-inflammatory status were also measured. Plasma nitrite concentration ([nitrite]) was increased in the BJ conditions (P < 0.001). Compared with the baseline visit, thumb CVC was greater following chronic-BJ (Δ2.0 flux/mmHg, P = 0.02) and chronic-NDBJ (Δ1.45 flux/mmHg, P = 0.01) supplementation; however, no changes in Tsk were observed (P > 0.05). Plasma [interleukin-10] was greater, pan endothelin and systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP) were reduced, and forearm endothelial function was improved, by both BJ and NDBJ supplementation (P < 0.05). Acute and chronic BJ and NDBJ supplementation improved anti-inflammatory status, endothelial function and blood pressure (BP). CVC following cooling increased post chronic-BJ and chronic-NDBJ supplementation, but no effect on Tsk was observed. The key findings are that beetroot supplementation improves thumb blood flow, improves endothelial function and anti-inflammatory status, and reduces BP in people with Raynaud’s.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This is the first study to examine the effect of dietary nitrate supplementation in individuals with Raynaud’s phenomenon. The principal novel findings from this study were that both beetroot juice and nitrate-depleted beetroot juice 1) increased blood flow in the thumb following a cold challenge; 2) enhanced endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilation in the forearm; 3) reduced systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and pan-endothelin concentration; and 4) improved inflammatory status in comparison to baseline.

Keywords: antioxidants, blood flow, nitrate

INTRODUCTION

Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP) is characterized by recurrent transient vasospasm of the fingers and/or toes in response to a cold or stressful stimulus (66) which causes discomfort and pain. Administration of NO donors, such as the organic nitrate, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), can improve blood flow in those with cold sensitivity (32) and RP (1). Reduced NO bioavailability has been implicated in the etiology of RP. Although GTN can improve blood flow in RP (1), chronic GTN administration produces a tolerance and diminishing vasodilatory effect (54). Moreover, organic nitrates (i.e., GTN and isosorbide mononitrate) can provoke deleterious side effects, such as headaches (66). Alternative long-term therapies to improve blood flow in RP warrant investigation.

Topical application of inorganic nitrate on the forearm and fingers of individuals with RP can increase blood flow (64) and may counter the vasoconstrictor effects of the endothelins which are elevated in RP (10). Leafy green vegetables and beetroot have a particularly high concentration of inorganic nitrate (8), and their vasodilatory effects can improve cardiovascular health (24). Dietary inorganic nitrate supplementation has been shown to improve skin blood flow (47) and microvascular function (39), and to lower blood pressure (BP) in healthy individuals (68) and those with hypertension (39), peripheral arterial disease (41), and heart failure (69). Promisingly, oral ingestion of inorganic nitrate does not appear to cause the same side effects or tachyphylaxis (57) reported for organic nitrates.

The efficacy of dietary inorganic nitrate supplementation is considered NO-mediated and evoked through the stepwise reduction of nitrate to nitrite, and finally, nitrite to NO (52). After oral consumption dietary inorganic nitrate is absorbed into the circulation, concentrated in the saliva, and converted to nitrite via anaerobic bacteria on the dorsum of the tongue (15). This nitrite is then swallowed (4) and absorbed into the circulation, where it acts as a storage pool for subsequent NO production. The reduction of nitrite to NO is expedited in conditions of acidosis and hypoxia (13), as seen in the digital vasculature in RP (66). The enterosalivary pathway is considered a complementary system for NO synthesis (50), which becomes increasingly important when the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) system is deficient, such as when individuals with RP are exposed to the cold (62).

Consumption of beetroot juice (BJ) can lower BP to a greater extent than an equimolar dose of an inorganic nitrate salt (36), suggesting that other components of BJ might interact with nitrate to elicit additive or synergistic effects on vascular function. The antioxidant (67) properties of BJ may be important, as attenuated NO-mediated vasodilation in inflammatory conditions is partly due to elevated oxidative stress (21, 49, 65). As RP is characterized by systemic oxidative stress and inflammation (6, 29), BJ may have a beneficial effect by increasing both NO and antioxidants (21). BJ may therefore offer an inexpensive and safe intervention to reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, to enhance peripheral blood flow and rewarming, and to mitigate pain following a local cold challenge in RP.

This study investigated the effects of acute and chronic BJ and nitrate-depleted BJ (NDBJ) supplementation on 1) cutaneous blood flow, rewarming and pain sensation following a local cold challenge, 2) inflammatory biomarkers, and 3) endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilation and BP in individuals with RP. We hypothesized that, compared with NDBJ, BJ would increase plasma nitrate ([nitrate]) and nitrite ([nitrite]) concentration, lower inflammation, and improve BP, endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilation, cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC), and peripheral skin rewarming following a local cold challenge.

METHODS

Participants

Individuals were recruited if they had primary or secondary RP, were at least 18 yr old, and were willing and able to provide consent for participation in the study. Individuals were excluded if they had known renal impairment (estimate of glomerular filtration rate < 30 ml/min); uncontrolled hypertension; were taking organic nitrates, nicorandil, or thiazolidinidiones; had experienced a myocardial or cerebrovascular event in the previous 3 mo; were a current smoker (any smoking event within the last 3 mo); or if they had any other serious medical condition which would interfere with data interpretation or participant safety. Participants taking phosphodiesterase inhibitors were asked to refrain from using them for the duration of the study. Mouthwash was prohibited for the duration of the study and for at least 1 wk before the first visit as reduction in the oral microflora is known to alter nitrate metabolism (27). Additionally, participants were asked to avoid caffeine and alcohol for 3 and 24 h before testing, respectively. Finally, participants were asked to record what they ate before each visit and replicate this where possible for the 24 h before arriving at the laboratory for subsequent testing.

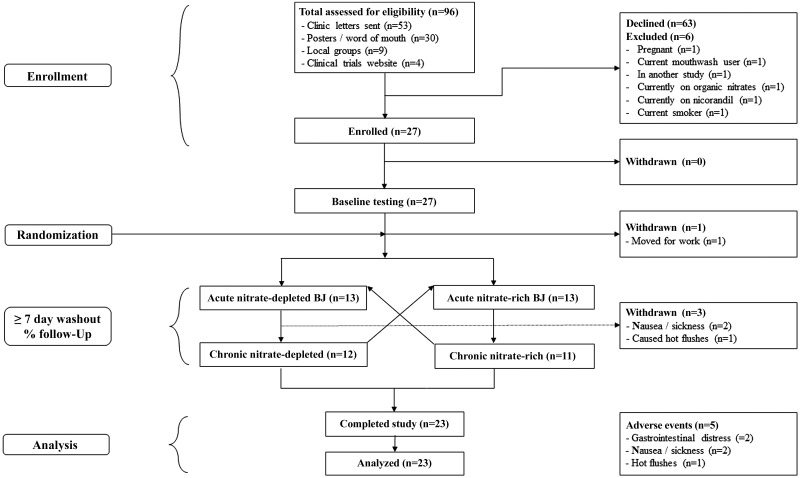

Twenty-seven participants were recruited (see Table 1) from a clinical database of individuals with RP from the Rheumatology Department, Queen Alexandra Hospital (Portsmouth, UK). Posters, word of mouth, and local interest groups were also targeted for recruitment. All participants provided written informed consent, and their flow through the trial is shown in Fig. 1. Ethical approval was granted by the Hampshire B NRES Committee (17/SC/0148), and this double-blind, randomized, crossover trial was registered on the ClinicalTrials.gov website (ID NCT03129178).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n = 23)

| Characteristics | Mean or % |

|---|---|

| Age | 64.3 ± 15.3 yr |

| Female | 83% |

| Raynaud's duration | 29.8 ± 23.9 yr |

| Secondary Raynaud's | 39.1% |

| Scleroderma | 17.4% |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | 17.4% |

| Systemic lupus | 8.7% |

| Mixed connective tissues disorder | 4.3% |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4.3% |

| Height | 1.7 ± 0.1 m |

| Mass | 64.3 ± 10.5 kg |

| Baseline systolic BP | 134.0 ± 18.6 mmHg |

| Baseline diastolic BP | 83.2 ± 10.2 mmHg |

| Number of 30+ min of exercise per week | 4.3 ± 2.5 |

| Portions of fruit and vegetables per day | 5.6 ± 2.7 |

| Mini Mental State Exam | 28.9 ± 0.9 |

Data are presented as means ± SD or as a % unless otherwise stated from participants who completed the trial. A number of individuals presented with two diseases specifically relating to secondary Raynaud’s Phenomenon. Mini Mental State Exam ranges from 0 to 30; we used a cut of 18 to determine capacity to consent.

Fig. 1.

Participant flow through the trial.

Preexperimental Tests

Following enrollment into the study, a letter was sent to each participant’s General Practitioner (GP), to inform them of their participation within the trial. Participants who did not want their GP informed (n = 1) were provided with the GP letter. Participants were given the opportunity to ask any questions they may have after reading the participant information sheet. A standard medical history and clinical examination were undertaken, which included height, body mass, ankle-brachial pressure index, and venous blood samples. Seated resting BPs (6 on each arm, mean of last 3 recorded) were performed using an automated BP monitor (Omron M5, Omron, Milton Keynes, UK). Participants then undertook a test of microvascular endothelial function (iontophoresis) in an ambient temperature of 23°C, followed by a cold challenge in an ambient temperature of 30°C (both described below) as baseline measures.

During the first visit, concealed allocation was used by an independent researcher to randomize participants to begin either the BJ or NDBJ arm of the study. Specifically, a computer program (https://www.randomizer.org) was utilized to randomly allocate study numbers to treatment order. The appropriate bottles of BJ were placed in a sealed opaque envelope. Participants were then provided with instructions and their first acute dose to take away with them. It was estimated that 25 individuals with RP were needed to achieve a moderate to large effect size in a pilot study (30). Therefore, we aimed to recruit 30 individuals with RP to account for a 15% dropout rate.

Protocol and Outcome Measures

For visits 2 and 4 (the acute supplementation visits), participants were instructed to ingest an acute dose of 140 mL of either BJ (delivering 12.4 mmol of inorganic nitrate) or NDBJ [delivering 0.1 mmol of inorganic nitrate (Beet It, James Whites Drinks Ltd.)] 1.5 h before arriving at the laboratory. We previously reported that both the BJ and NDBJ have similar antioxidants and polyphenol content (59). On arrival at the laboratory, participants rested for 10 min. Resting seated BP was then measured 5 times, with the mean of the last 3 recorded. A ~20-mL venous blood sample was then drawn from the antecubital fossa. The iontophoresis derived measures of microvascular endothelial function conducted at baseline were then repeated in ambient conditions (23°C), followed by a cold challenge in an ambient temperature of 30°C (both described below). Visits 3 and 4 (after the crossover period) were separated by at least 7 days to allow washout, and all visits were conducted at the same time of day (±1 h) in a counterbalanced order. Visits 3 and 5 (the chronic supplementation visits) were identical in nature to visits 2 and 4, but followed chronic supplementation of 70 mL/day of either BJ or NDBJ for 13 days with 140 mL consumed on the day of testing. Participants, if requested, were reminded to take the juice via text message or voice mails.

Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome measure was change in cutaneous blood flow and rewarming following a local cold challenge. Secondary outcome measures included endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilation, pain, inflammatory biomarkers, and BP.

Microvascular endothelial function test.

Individuals were acclimated for a minimum of 30 min in an ambient temperature of 23.2 ± 0.4°C before acetylcholine (ACh) and sodium nitroprusside (SNP) being delivered transdermally via iontophoresis to three sites in the following order: 1) volar aspect of the left forearm, 2) middle phalanx of the middle finger of the left hand, and 3) dorsal aspect of the left foot as previously described (17).

Briefly, following cleaning of the skin surface with water for injection, two Perspex rings were attached to the skin with one acting as an anode, and the other as the cathode. These electrodes were connected to the iontophoresis controller (MIC 2, Moor Instruments, UK). Both chambers had an 8-mm inner diameter. The anode chamber was filled with ~0.5 mL of ACh (Braun, Melsungen, Germany), with a 1% concentration dissolved in water for injection. The cathode chamber was filled with ~0.5 mL of SNP (Sigma-Aldrich) with a 0.01% concentration dissolved in water for injection. The protocol for electrical pulses included: four at 25 μA, followed by a single pulse of 50 μA, 100 μA, 150 µA, and 200 µA. These pulses lasted for 20 s with 120-s intervals between each pulse where no current was applied. An interval of 5 min was given between testing each site (forearm, finger, and foot).

Laser Doppler probes (VP1T/7, Moor Instruments), connected to a perfusion monitor (Moor VMS-LDF, Moor Instruments) were used to assess skin blood flow. Data were recorded using an acquisition system (Powerlab, AD Instruments, Australia) and software (LabChart 7, AD Instruments, Australia). The laser Doppler probes were secured in the Perspex rings before the iontophoresis protocol on the forearm, finger, dorsal foot, and on the corresponding site on the contralateral limb (to differentiate between local and systemic responses). Skin blood flow responses were expressed as CVC (CVC = skin flux/MAP; flux/mmHg). The average skin blood flow for both ACh and SNP was calculated over the final 20 s of the intervals between each successful pulse (i.e., 100–120 s post each pulse) (17). Maximal skin blood flow, taken at the highest point which was not always following the final pulse, and area under the curve (AUC) were calculated for each participant. Skin temperature (Tsk) was recorded with skin thermistors (Grants Instruments, Cambridge, UK) placed next to the Perspex chambers. BP was measured on the contralateral arm to the site of iontophoresis using an automated BP monitor (Omron M5, Omron, Milton Keynes, UK) before and after each iontophoresis protocol to calculate mean arterial pressure (MAP).

Cold sensitivity test.

The cold sensitivity test used in this study has been comprehensively described elsewhere (17). Testing took place in a climatic-controlled chamber at an air temperature of 29.6 ± 0.87°C. Participants were asked to remove their shoes and socks, and rest in a semirecumbent position for 15 min. Those capable of cycling (n = 20) were asked to cycle on an ergometer (Tunturi, T6, Turku, Finland) between 20 and 50 W for 12 min as this has been shown to improve the reliability of the test by removing central vasoconstrictor tone (18). Participants were then asked to rest in a semirecumbent position for a minimum of 5 min while resting toe temperature and blood flow were recorded.

The participants placed their foot (n = 21/23 right foot) into a plastic bag (to keep it dry) and immersed into 15.02 ± 0.01°C water to the point of their mid-malleoli for 2 min. Following the immersion period, the bag was removed and the rate of toe skin rewarming and blood flow were recorded while the participant was semirecumbent. This procedure was then repeated on the hand (mean temperature; 14.95 ± 0.02°C: n = 22/23 right hand), following 5 min seated rest. During the rewarming the arm was supported.

Skin blood flow was assessed using a laser Doppler probe (VP1T/7, Moor Instruments, UK) secured to the great toe pads during foot immersion and on the pads of the thumbs during hand immersion. Analysis of skin blood flow was conducted using minute averages before, during, and after immersion (i.e., rewarm period) and expressed as CVC. CVC was analyzed between conditions at the following time points: preimmersion, and during 5 and 10 min of rewarming following removal from the water.

Tsk was measured using an infrared camera (A320G, FLIR Systems, UK) and in accordance with the protocol described by Moreira et al. (53). The camera lens was positioned 1.0 m away from the sole of the participant’s foot and the palm of the hand and the spot analysis function on the FLIR software (FLIR Systems) was used to analyze the surface temperature on the pads of the toes/fingers immediately before immersion and at the end of each minute during the 10-min rewarm. The thumb, mean finger (mean of all 5), great toe, mean toe, and coldest toe Tsk were analyzed between conditions and across time at multiple time points: preimmersion and 5 and 10 min into the rewarming period. Within our laboratory, the coefficient of variation for the cold sensitivity test for finger and toe Tsk is 2.7% and 8.7%, respectively (17). MAP was calculated from BP measured using an automated blood pressure monitor (Omron M5, Milton Keynes, UK) on the left arm before each immersion and following both rewarming periods.

Both thermal comfort and sensation were measured using a 20-cm scale [0 = very cold/uncomfortable; 10 = neutral; 20 = very hot/comfortable; modified from Zhang et al. (70)] and recorded before immersion, during immersion, and every 2 min of the rewarming period. Pain sensation was assessed using a numerical rating scale for pain [0 no pain, 10 unimaginable, unspeakable pain (19)] at the same time points.

Biochemical Analysis

Venous blood (and saliva where blood could not be taken, n = 2) samples were taken and processed before testing on each study visit. Blood samples for plasma [nitrate] and [nitrite] were taken in lithium heparin tubes and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes for assessment of oxidative stress and inflammatory markers. The blood and saliva samples were placed in a chilled (4°C) centrifuge and spun at 4,500 g for 10 min immediately following collection. Once spun, the plasma and saliva were pipetted into aliquots with a link anonymized code. The samples were then placed in a −80°C freezer until subsequent analysis. Plasma and saliva samples were analyzed for [nitrate] and [nitrite] using a Sievers NO analyzer (Sievers NOA 280i, Analytix, Durham, UK), via a modification of the ozone chemiluminescence technique previously described by Bateman et al. (3). Plasma [peroxiredoxin-4] and [thioredoxin-1] were quantified using in-house ELISAs developed using commercially available antigens and antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The human SOD3 antigen and rabbit antiserum directed against human [superoxide dismutase-3] were developed as previously described (26). A cytometric bead array technique was used to quantify plasma interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-10 on a BD C6 Accuri Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, Berkshire, UK). [Pan endothelin] was quantified using commercially available DuoSet ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK).

Qualitative Analysis

Semistructured interviews were conducted to examine the acceptability of the supplement and the testing procedures. Specifically, semistructured interviews explored participants’ experiences of the study procedures and consumption of BJ. At the time of the interviews, both the interviewer and participants were still blinded to the treatment order. A total of 10 semistructured interviews were necessary to reach a point of data saturation (i.e., where no new information was provided by the participants). Interviews were conducted by a researcher with experience in qualitative research methods. Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed through thematic analysis as outlined by Braun and Clarke (7). A deductive process was used throughout the analysis, where transcripts were reviewed and direct quotations were used to establish initial codes for each question posed. Codes were then grouped together to create themes based on identified similarities. Coding of transcripts relied on a reflexive process, where themes were constantly compared with initial codes and the data set as a whole.

Data Analysis

As previously reported with iontophoresis (17), some individuals had high skin resistance which meant that not all pulses could be delivered to the forearm, fingers, and feet. Where participants had incomplete data sets (current response curves), the number of pulses analyzed was the same within individual for each visit (17).

The distribution of data was assessed using descriptive methods (skewness, outliers, and distribution plots) and inferential statistics (Shapiro-Wilk test). Where normal distribution was violated nonparametric analyses were performed. For the cold sensitivity test, statistical differences were assessed using 5 × 3 repeated-measures ANOVAs [condition (baseline, acute BJ, chronic BJ, acute NDBJ, and chronic NDBJ supplementation) × time (preimmersion, 5 min, 10 min)] for mean toe, coldest toe, great toe, mean finger, coldest finger, and thumb Tsk, and thumb and great toe skin blood flows. For the endothelial function test, maximum CVC, AUC, and Tsk were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVAs (baseline, acute BJ, chronic BJ, acute NDBJ, and chronic NDBJ supplementation). Plasma [nitrate] and [nitrite] were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA, and all other biomarkers were analyzed using Friedman tests. Where appropriate, post hoc tests were conducted using pairwise comparisons with least significant differences. Where data were not normally distributed Friedman tests were used with Wilcoxon follow ups. Data are presented as mean (SD) or as median and 25th and 75th percentiles unless otherwise stated. Statistical analysis was performed on SPSS version 24 (Chicago, IL), and statistical difference and trends toward significance were accepted as two-tailed P < 0.05 and P < 0.1, respectively. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed thematically.

RESULTS

Twenty-seven individuals consented to take part in the trial, and 23 completed the study. A detailed analysis of participant recruitment and withdrawal is shown in Fig. 1. We report 5 adverse events. Of the 4 participants who withdrew, 1 withdrew to relocate for work, 1 reported hot flushes, and 2 reported nausea and sickness (all outside of the laboratory). One of these adverse events was related to the intervention and the other two may have been related to the intervention. Two participants reported gastrointestinal distress which was tolerable for the duration of the study. Participant-reported adherence to the supplementation protocol was excellent, with only one participant reporting missing 1 day during the chronic supplementation period. All participants reported avoiding mouthwash during the testing periods. Numerous participants reported red stools and beeturia as with previous studies (17, 58–60). The full data set for this trial has been made available as Supplemental Material on our University repository (https://doi.org/10.17029/f9c6af22-d8f5-4989-9cf1-1422b9467010).

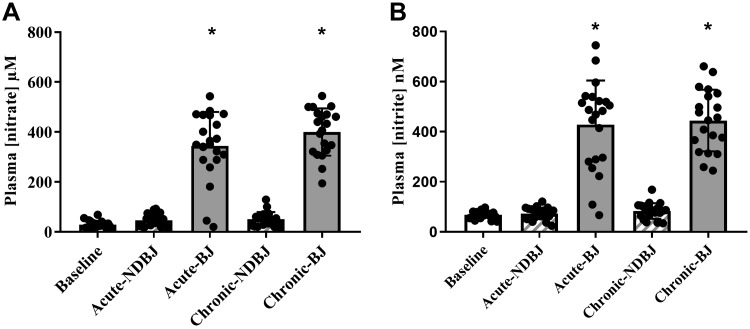

Plasma [Nitrate] and [Nitrite]

Supplementation with BJ significantly increased plasma [nitrate] (P < 0.001; Fig. 2) and [nitrite] (P < 0.001; Fig. 2). Post hoc analysis revealed a statistically significant rise in plasma [nitrate] between acute NDBJ and acute BJ supplementation (43 ± 25 µM; 339 ± 146 µM; P < 0.001, respectively) and chronic NDBJ and chronic BJ supplementation (52 ± 29 µM; 397 ± 96 µM; P < 0.001, respectively) and plasma [nitrite] between acute NDBJ and acute BJ supplementation (69 ± 23 nM; 428 ± 187 nM; P < 0.001, respectively) and chronic NDBJ and chronic BJ supplementation (87 ± 31 nM; 428 ± 117 nM; P < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 2). There were no differences between acute and chronic NDBJ (P > 0.05) and acute and chronic BJ (P > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Mean (SD) plasma [nitrate] (A) and [nitrite] (B) in the baseline, acute nitrate-depleted (acute-NDBJ), nitrate-rich (acute-BJ) beetroot juice, and chronic nitrate-depleted (chronic-NDBJ) and nitrate-rich (chronic-BJ) beetroot juice supplementation conditions (n = 21). *P < 0.001, significantly different from acute-NDBJ and chronic-NDBJ and baseline. Plasma [nitrate] and [nitrite] were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA.

Cold Sensitivity Test

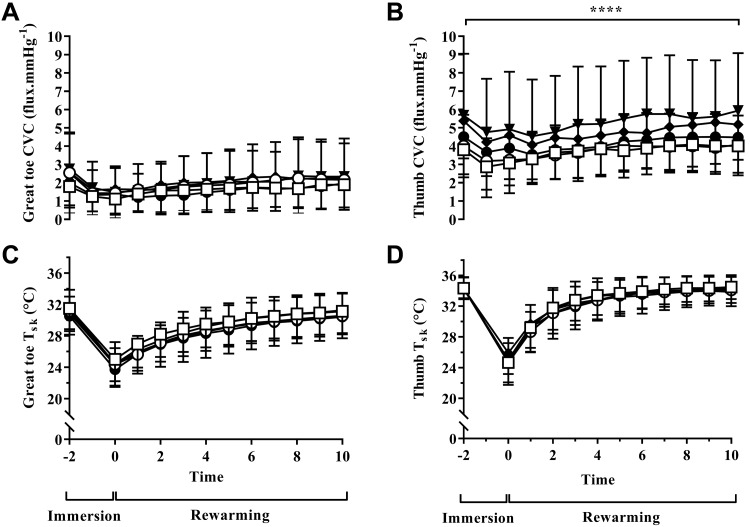

A significant difference in CVC was observed between the visits for supplement (P = 0.01), time (P = 0.01), but not their interaction (P = 0.52) in the thumb (see Fig. 3B). Follow-up tests revealed increased thumb CVC between baseline and chronic NDBJ (2.0 flux/mmHg, P = 0.02) and chronic BJ (1.45 flux/mmHg, P = 0.01). Chronic supplementation resulted in a greater thumb CVC than acute supplementation for both the NDBJ (1.9 flux/mmHg, P = 0.03) and BJ (1.3 flux/mmHg, P = 0.01; see Fig. 3B) conditions. No differences were seen in the great toe CVC (all P ≥ 0.05; see Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Mean ± SD great toe cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC) (A), thumb CVC (B), great toe skin temperature (C) and thumb skin temperature (Tsk) (D) for baseline (open squares), acute nitrate-depleted beetroot juice (NDBJ) (open circles), acute nitrate-rich beetroot juice (BJ) (closed circles), chronic NDBJ (closed triangles) and chronic BJ (closed diamonds) supplementation conditions. *P < 0.05 significant difference in four places within B: 1) baseline to chronic-NDBJ, 2) baseline to chronic-BJ, 3) acute-NDBJ and chronic-NDBJ, and 4) acute-BJ and chronic-BJ (n = 23). Data were analyzed using 5 × 3 repeated-measures ANOVAs [condition (baseline, acute-BJ, chronic-BJ, acute-NDBJ and chronic-NDBJ supplementation) × time (pre immersion, 5 min, 10 min)] for mean toe, coldest toe, great toe, mean finger, coldest finger and thumb Tsk, thumb, and great toe skin blood flows.

Tsk of the toes (great toe, coldest toe, and mean toe temperature) and fingers (thumb, coldest finger, and mean finger temperature) was not altered by acute or chronic supplementation with BJ or NDBJ (P > 0.05 for all comparisons; Fig. 3, C and D). Tsk of the toes and fingers were not different when split for disease type (data not shown, P > 0.05).

Thermal comfort, sensation. and pain.

There were no differences in thermal sensation, thermal comfort, or pain sensation for the hand at any time point during the cold sensitivity test between visits (P < 0.05). In the foot, there were no differences between conditions for thermal sensation or pain sensation at any time point. Although thermal comfort was similar before immersion, it was perceived differently during immersion (P < 0.05), immediately after immersion (P = 0.004), and during rewarming (P = 0.02). During immersion, participants reported feeling more thermally comfortable in the baseline condition compared with the acute-NDBJ (P = 0.04; Table 2) and chronic-BJ supplementation conditions (P = 0.006; Table 2). Thermal comfort was also greater following acute- compared with chronic-NDBJ supplementation (P = 0.001) during immersion. Immediately after immersion, participants felt less thermal comfort compared with baseline in all the other conditions (acute NDBJ, P = 0.003; acute BJ, P = 0.03; chronic NDBJ, P = 0.002; and chronic BJ, P = 0.002; Table 2). During the rewarming phase, the baseline condition was reported as more thermally comfortable than either the acute NDBJ (P = 0.03; Table 2) or the chronic BJ (P = 0.008; Table 2) conditions.

Table 2.

Thermal sensation, thermal comfort and pain in the foot and hand during the cold sensitivity test at baseline, nitrate-depleted (NDBJ), and nitrate-rich (BJ) beetroot juice supplementation conditions

| Condition | n | Preimmersion | During Immersion | Immediately After Immersion | Average Rewarm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foot | |||||

| Thermal sensation | |||||

| Baseline | 21 | 11.8 ± 4.0 | 4.4 ± 2.6 | 7.6 ± 4.3 | 11.0 ± 2.9 |

| Acute NDBJ | 21 | 12.7 ± 4.2 | 3.8 ± 2.2 | 5.4 ± 2.9 | 9.7 ± 3.1 |

| Acute BJ | 21 | 12.4 ± 4.8 | 3.7 ± 2.6 | 5.6 ± 2.4 | 10.5 ± 3.2 |

| Chronic NDBJ | 21 | 13.3 ± 3.8 | 4.6 ± 3.2 | 5.5 ± 3.2 | 10.5 ± 2.7 |

| Chronic BJ | 21 | 11.9 ± 4.2 | 3.9 ± 2.3 | 5.2 ± 2.6 | 9.7 ± 3.4 |

| Thermal comfort | |||||

| Baseline | 21 | 13.0 ± 5.3 | 9.1 ± 5.0 | 11.2 ± 4.1 | 13.2 ± 3.6 |

| Acute NDBJ | 21 | 12.6 ± 4.2 | 7.1 ± 5.4† | 7.5 ± 4.0† | 11.3 ± 3.8† |

| Acute BJ | 21 | 13.0 ± 5.2 | 7.6 ± 4.4 | 9.2 ± 3.9† | 12.1 ± 3.7 |

| Chronic NDBJ | 21 | 13.1 ± 5.1 | 7.5 ± 4.3‡ | 7.4 ± 3.0† | 12.2 ± 3.5 |

| Chronic BJ | 21 | 12.7 ± 5.0 | 6.6 ± 4.6† | 8.2 ± 4.5† | 11.1 ± 3.6† |

| Pain | |||||

| Baseline | 20 | 0.2 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 1.7 | 1.0 ± 1.7 | 0.2 ± 0.6 |

| Acute NDBJ | 20 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 1.3 | 0.7 ± 1.3 | 0.2 ± 0.6 |

| Acute BJ | 20 | 0.2 ± 0.8 | 0.7 ± 1.3 | 0.7 ± 1.3 | 0.3 ± 0.8 |

| Chronic NDBJ | 20 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 1.7 | 0.8 ± 1.7 | 0.9 ± 2.7 |

| Chronic BJ | 20 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | 0.2 ± 0.6 |

| Hand | |||||

| Thermal sensation | |||||

| Baseline | 21 | 13.2 ± 2.4 | 4.1 ± 2.9 | 6.0 ± 3.6 | 11.5 ± 2.8 |

| Acute NDBJ | 21 | 13.8 ± 3.3 | 3.6 ± 2.2 | 5.6 ± 2.9 | 12.1 ± 3.2 |

| Acute BJ | 21 | 13.6 ± 2.5 | 3.4 ± 2.3 | 5.8 ± 2.7 | 12.1 ± 3.9 |

| Chronic NDBJ | 21 | 13.9 ± 3.4 | 3.9 ± 3.0 | 5.1 ± 3.7 | 11.9 ± 3.2 |

| Chronic BJ | 21 | 13.7 ± 2.4 | 3.6 ± 2.2 | 5.8 ± 2.7 | 12.2 ± 3.2 |

| Thermal comfort | |||||

| Baseline | 21 | 13.7 ± 4.5 | 6.2 ± 4.5 | 9.3 ± 4.7 | 13.4 ± 3.8 |

| Acute NDBJ | 21 | 15.1 ± 4.0 | 6.8 ± 5.3 | 8.0 ± 4.3 | 12.6 ± 3.7 |

| Acute BJ | 21 | 14.8 ± 3.9 | 7.3 ± 4.4 | 8.4 ± 4.1 | 13.1 ± 3.2 |

| Chronic NDBJ | 21 | 14.6 ± 4.1 | 7.2 ± 4.3 | 6.7 ± 3.9 | 12.9 ± 3.0 |

| Chronic BJ | 21 | 15.6 ± 3.5 | 6.4 ± 4.5 | 8.4 ± 3.9 | 13.5 ± 3.5 |

| Pain | |||||

| Baseline | 20 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.2 ± 0.6 |

| Acute NDBJ | 20 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 1.3 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 0.2 ± 0.6 |

| Acute BJ | 20 | 0.2 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 1.3 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 0.3 ± 0.8 |

| Chronic NDBJ | 20 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 1.7 | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 0.9 ± 2.7 |

| Chronic BJ | 20 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.2 ± 0.6 |

Data are presented as means ± SD. Average rewarm is the mean over the last 8 min of rewarming.

Significantly different from baseline (P < 0.05);

significantly different from acute NDBJ (P < 0.05).

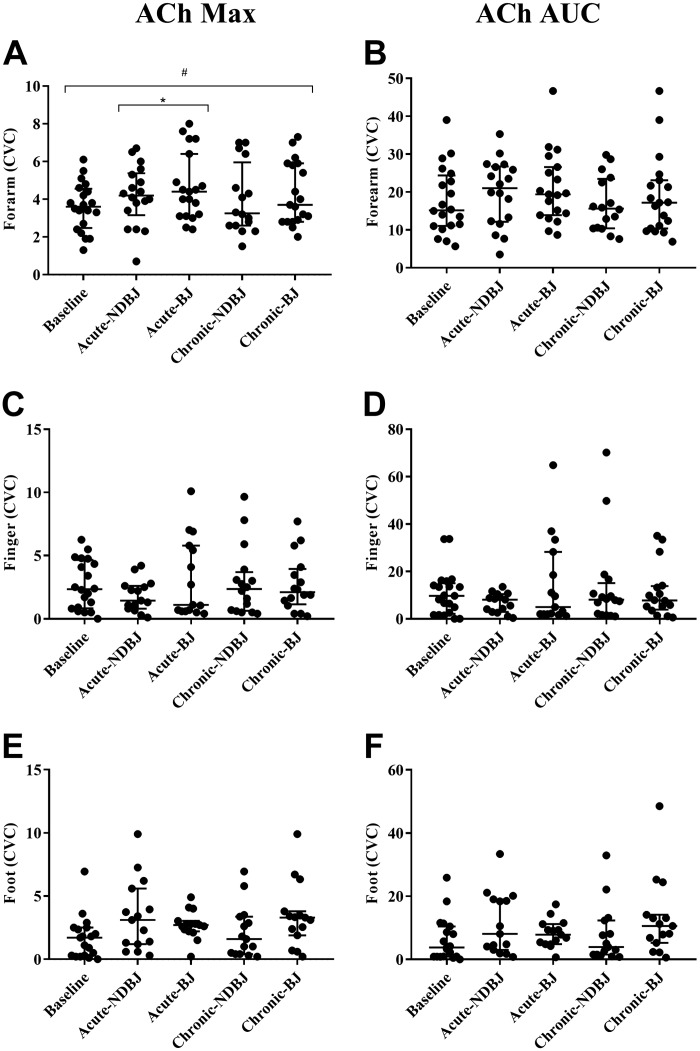

Microvascular Endothelial Function

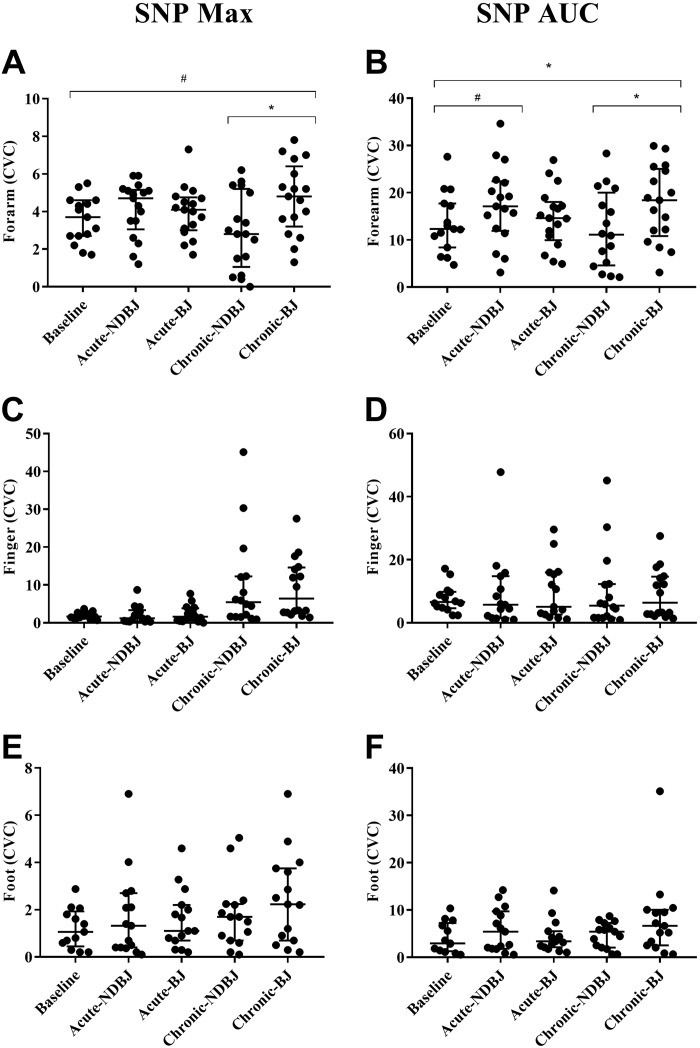

Endothelial-dependent and -independent function was significantly different between the visits for supplement in the forearm for Ach Max (P = 0.05), SNP Max (P = 0.02), and SNP AUC (P = 0.03) but not ACh AUC (P = 0.21). Post hoc tests revealed that, compared with baseline, acute-BJ increased CVC with ACh (Max, P = 0.02) and chronic-BJ increased CVC with SNP (Max, P = 0.05). Chronic-BJ supplementation was also found to significantly increase CVC with SNP (Max, P = 0.001; and AUC, P = 0.02) compared with NDBJ. Trends toward a significant increase in CVC compared with baseline were also seen with chronic-BJ with ACh (Max P = 0.07) and SNP (AUC, P = 0.09) and acute-NDBJ with SNP (AUC, P = 0.08).

The responses to ACh and SNP were similar during all five visits on the finger (ACh Max, P = 0.67; ACh AUC, P = 0.84; SNP Max, P = 0.80; SNP AUC; P = 0.95) and foot (ACh Max, P = 0.10; ACh AUC, P = 0.25; SNP Max, P = 0.21; SNP AUC, P = 0.52) (see Figs. 4 and 5, respectively, and Supplemental Table S1 (https://doi.org/10.17029/efb3d969-11e9-41f7-8187-2107ea8e789d).

Fig. 4.

Data are presented as median and interquartile range (25 and 75 percentiles) for maximum cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC) (A, C, E) and for area under the curve (AUC) (B, D, F). Significant difference is depicted with a * (P < 0.05) and trends with a # (P < 0.10). For the endothelial function test, maximum CVC and AUC were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVAs [baseline, acute nirate-rich beat juice (BJ), chronic BJ, acute nitrate-depleted beet juice (NDBJ), and chronic NDBJ supplementation]. Where data were not normally distributed Friedman tests were used with Wilcoxon follow ups. Max, maximum.

Fig. 5.

Data are presented as median and interquartile range (25 and 75 percentiles) for maximum cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC) (A, C, E) and area under the curve (AUC) (B, D, F). Significant difference is depicted with a * (P < 0.05) and trends with a # (P < 0.10). For the endothelial function test, maximum CVC and AUC were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVAs [baseline, acute nitrate-rich beat juice (BJ), chronic BJ, acute nitrate-depleted beet juice (NDBJ), and chronic NDBJ supplementation]. Where data were not normally distributed Friedman tests were used with Wilcoxon follow ups. Max, maximum.

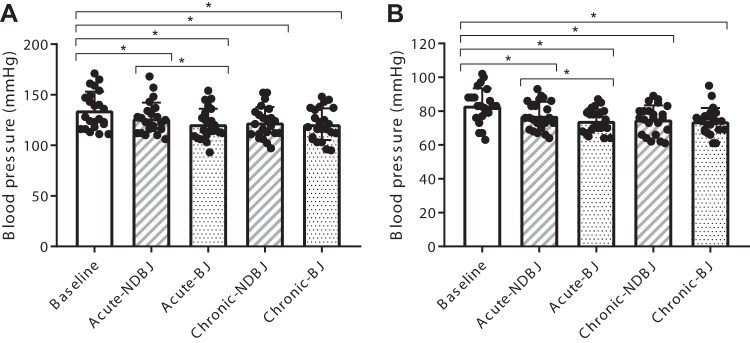

Blood Pressure

Systolic and diastolic BP were different across time (SBP; P < 0.001, DBP; P < 0.001). Compared with acute NDBJ, acute BJ significantly reduced systolic BP (127 ± 16 mmHg versus 121 ± 16 mmHg, P = 0.01) and diastolic BP (77 ± 8 mmHg versus 74 ± 7 mmHg; P = 0.03). This effect was not present with chronic supplementation for either systolic BP (NDBJ: 122 ± 15 mmHg; BJ: 121 ± 16 mmHg, P = 0.43) or diastolic BP (NDBJ: 75 ± 8 mmHg; BJ: 74 ± 8 mmHg, P = 0.49). Compared with baseline, both NDBJ and BJ reduced systolic BP (acute NDBJ: 8.0 ± 11 mmHg, P = 0.02; acute BJ: 13.6 ± 10.8 mmHg, P < 0.001; chronic NDBJ: 12 ± 14 mmHg, P < 0.001; and chronic BJ: 14 ± 11 mmHg, P < 0.001) and diastolic BP (acute NDBJ: 6 ± 8 mmHg, P = 0.02; acute BJ: 9 ± 7 mmHg, P < 0.001; chronic NDBJ: 8 ± 9 mmHg, P < 0.001; and chronic BJ: 9 ± 7 mmHg, P < 0.001) (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Systolic (A) and diastolic (B) diastolic blood pressure for baseline, acute (acute-NDBJ) and chronic (chronic-NDBJ) nitrate-depleted beetroot juice (NDBJ) and acute (acute-BJ) and chronic (chronic-BJ) nitrate-rich beetroot juice (BJ) supplementation conditions. Data are presented as means ± SD *P < 0.05, significantly different from corresponding brackets (n = 23). Data were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA.

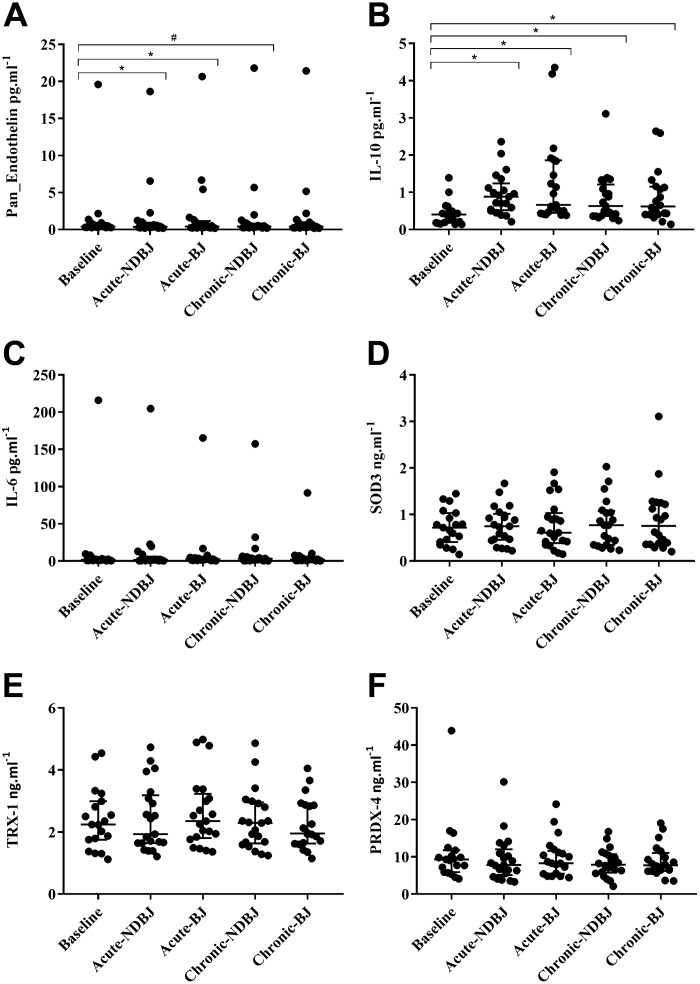

Cytokines and Redox Markers

Pan-endothelin concentration ([Pan endothelin]) was reduced after supplementation with BJ (P = 0.03; Fig. 7A). Acute NDBJ (P = 0.01) and BJ (P = 0.04) resulted in higher [pan-endothelin] compared with baseline. There was a trend for an increase with chronic NDBJ (P = 0.07) but not chronic BJ (P = 0.18; Fig. 7A). BJ supplementation altered plasma concentrations of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 (P < 0.001; Fig. 7B) with IL-10 increasing in all four experimental conditions compared with baseline (acute NDBJ, P < 0.001; acute BJ, P < 0.001; chronic-NDBJ, P = 0.001; and chronic-BJ, P = 0.002; Fig. 7B) but did not alter IL-6 (P = 0.97; Fig. 7C) between conditions. Plasma [SOD3], (P = 0.18; Fig. 7D), TRX-1, (P = 0.11; Fig. 7E), and PRDX-4 (P = 0.28; Fig. 7F) did not differ between visits. IL-10 was significantly higher than baseline for all time points for primary but not secondary RP (P < 0.001) (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Median and interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles) for pan-endothelin (A), IL-10 (B), IL-6 (C), SOD3 (D), TRX-1 (E), and PRDX-4 (F) at baseline, acute (acute-NDBJ), and chronic (chronic-NDBJ) nitrate-depleted beetroot juice (NDBJ) and acute (acute-BJ) and chronic (chronic-BJ) nitrate-rich beetroot juice (BJ) supplementation conditions. *P < 0.05, significantly different from baseline; #trending toward significance (P = 0.07) (n = 21). Friedman tests were used to assess main effects and where appropriate, post hoc tests were conducted using pairwise comparisons with least significant differences.

Qualitative Interviews

Semistructured exit interviews were conducted with 10 participants. Several recruitment strategies were used (as described in methods), and participants recommended that similar strategies be used to recruit participants in the future with the additional use of social media suggested for future trials. Most participants (n = 20) experienced symptoms of RP in their hands, with three individuals stating that they felt greater discomfort in their feet. Overall, participants said that the study was a positive experience. One participant indicated the BJ made her feel ill. However, this participant decided to continue with the study and did not withdraw. None of the participants were sure they had felt any positive health benefits as a result of the juice, during any of the sessions. One participant indicated she felt as though the juice “...opened up her blood vessels,” but this was deemed as neither a positive or negative reaction to the juice. Most participants did not enjoy drinking the juice, with only one participant indicating that he enjoyed it. Participants mentioned the juice had an unpleasant taste, with some individuals complaining it tasted metallic, too sweet, and had a thick composition. Despite the negative reaction to the juice, most individuals indicated they simply adjusted to the juice. Nearly all individuals said they would wait to find out the results of the study before purchasing the juice or discussing it with other individuals. One individual said he would happily purchase it and recommend it highly to his friends and family.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine the effect of dietary nitrate supplementation in individuals with RP. Specifically, we examined the effects of supplementation with BJ on cutaneous blood flow, rewarming, and pain sensation following a local cold challenge, and inflammatory biomarkers, antioxidant enzymes, endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilation, and BP in individuals with RP compared with baseline and NDBJ. The principal novel findings from this study were that both BJ and NDBJ 1) increased blood flow in the thumb following a cold challenge; 2) enhanced endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilation in the forearm; 3) reduced systolic BP, diastolic BP, and [pan-endothelin]; and 4) improved inflammatory status in comparison to baseline. These findings suggest acute and chronic BJ and NDBJ supplementation have the potential to reduce inflammatory status and improve aspects of vascular function in individuals with RP.

Plasma [Nitrate] and [Nitrite]

Plasma [nitrate] and [nitrite] were elevated following acute and chronic BJ supplementation compared with NDBJ. This elevation in circulating plasma [nitrite] represents an increase in the potential for nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-independent NO generation, with NOS-dependent NO generation attenuated in conditions of increased oxidative stress (21, 49, 65) such as in RP (6, 29). Hypoxic and acid environments are known to increase conversion of nitrite to NO (13), and since the digital vasculature is more hypoxic and acidic in RP (1) increased plasma [nitrite] following BJ supplementation had the potential to increase blood flow and rewarming compared with NDBJ.

Cold Sensitivity Test

In individuals with cold sensitivity, acute BJ does not improve skin temperature or blood flow in the hands or feet (17). However, an increased skin blood flow in the thumb in individuals with RP following chronic supplementation of BJ and NDBJ was observed in the current study. No effect in the feet was observed, which may at least in part be due to divergent mechanisms of vascular control in the hands and feet (55). Thumb skin blood flow was higher before immersion and stayed higher during and following immersion in both chronic supplementation protocols indicating this effect is likely due to the antioxidant content of beetroot as opposed to nitrate content of BJ, and the elevations in [nitrate] and [nitrite] given the comparable responses in the BJ and NDBJ conditions. Indeed, some antioxidant and polyphenol compounds found in the BJ/NDBJ have previously been shown to have vasodilatory properties such as chlorogenic acid (56), quercetin (16), and caffeic acid (45), and this may at least in part explain why we see changes in blood flow in both types of juice. The observed improvement in skin blood flow did not however translate into increased skin temperature. Although the increase in skin temperature following the cold challenge is due to cutaneous blood flow in healthy controls, individuals with poor peripheral blood flow rewarm passively in a warm environment (14). Therefore, it could be that, although CVC was increased in the small area under the laser Doppler probe, the overall increase in skin blood flow was not large enough to translate into a statistical or clinically meaningful change in skin temperature (i.e., 0.5°C) (2).

Thermal Comfort, Sensation, and Pain

Neither BJ nor NDBJ altered thermal sensation or comfort in the hand or feet during the cold sensitivity test, which is similar to previous findings in cold-sensitive individuals (17). Thermal comfort of the foot was, however, reduced during cooling and in the subsequent rewarming period following BJ supplementation, despite Tsk being the same. Since thermal comfort was not altered before immersion, BJ may have altered the perception of cooled skin although not to a level where increased pain was reported. Thermal sensation and particularly thermal comfort are subjective, and some participants struggled to decide on a number to report, especially when their foot was numb. The apparent decrease in comfort could be a function of being more familiar with the scales and therefore being able to respond more promptly at a time of dynamic activation of the cutaneous thermoreceptors which is critical for perception of comfort (14). Given CVC increased in the thumb and thermal sensation was not worse there could be a site-specific effect that is linked to alterations in blood flow. Most participants reported RP symptoms in the hands and not their feet, so an increased CVC in the hand with no changes in thermal sensation may be a positive outcome; however, this warrants further investigation.

Endothelial Function

Individuals with RP exhibit cutaneous microvascular dysfunction which manifests as reduced finger blood flow in all environmental conditions compared with controls (28). Some of this dysfunction is due to impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation (43). The effect of nitrate supplementation on endothelial function has been examined in numerous cohorts such as healthy individuals (47), cold-sensitive individuals (17), obese individuals (37), and individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (25), and has been reviewed elsewhere (46). The dose appears to be important (46); however, comparison of acute vs. chronic supplementation has yet to be examined in any population. Neither BJ nor NDBJ altered microvascular endothelial function in the fingers or the foot. However, improvements in endothelium-independent (SNP) and -dependent (ACh) vasodilation were observed in the forearm following chronic BJ supplementation. Potential explanations for the change in SNP-induced smooth muscle cell function following chronic supplementation could be due to a suppression in eNOS-derived NO (11) and/or nitrite-mediated inhibition of NADPH-derived superoxide, leading to increased bioavailability of NO (22). Collectively, such effects might explain the enhanced responsiveness to the exogenous NO donor, SNP. Collectively, such effects might explain the enhanced responsiveness to an exogenous NO donor. Chronic BJ also increased cutaneous vasodilation in the forearm to ACh administration compared with chronic NDBJ, suggesting that the elevated nitrite, NO, and/or their intermediates may have evoked additional vasodilatory effects from those elicited by the antioxidants in BJ. Improvements in forearm arm blood flow suggest that the effects of BJ and NDBJ are systemic (31). Iontophoresis on the foot and fingers was not always possible due to high skin resistance meaning that the sample size was compromised, which may explain why no effect was observed at these sites. Conversely, it may be that nitrite levels were not increased sufficiently to improve digital microvascular function. However, given the increased blood flow following hand cooling, this seems implausible.

Endothelins are a family of peptides that cause vasoconstriction and thus antagonize the actions of NO. Although acute BJ and NDBJ reduced plasma concentrations of pan-endothelin compared with baseline (Fig. 5), chronic BJ and NDBJ did not alter plasma [pan-endothelin] which suggests that divergent mechanisms may underpin changes in endothelial function after acute and chronic BJ and NDBJ supplementation. RP is associated with elevated [endothelin-1] (10), which can lead to chronic pain (61) and may also explain why endothelial function is impaired (38). However, our cohort did not appear to have impaired endothelial function at baseline compared with healthy controls (17). Therefore, we cannot preclude a larger effect in individuals with overt endothelial dysfunction. Our cohort, however, self-reported high levels of physical activity (4.3 ± 2.5 bouts of >30 min/wk). Regular exercise is a key stimulus for promoting endogenous NO production via shear stress-induced activation of endothelial NOS (9). This may explain, in part, why additional nitrate via the enterosalivary pathway failed to show an additional benefit between BJ versus NDBJ, and perhaps a more sedentary cohort of participants may have benefited. IL-10, on the other hand, increased across all time points and, therefore, may play a larger role in mediating the changes in vascular function after acute and chronic BJ and NDBJ supplementation in individuals with RP.

Blood Pressure

The present data also demonstrated a reduction in both systolic and diastolic BP in all conditions compared with baseline. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that NDBJ can reduce BP. Explanations for this reduction in BP are multifactorial. A well-recognized phenomenon of BP trials is that BP appears to fall across time, and, as such, caution should be taken with interpreting these findings. However, there are other active ingredients in BJ, including antioxidants and polyphenols (59, 67) such as batalins, gallic acid, chlorogenic acid, and quercetin [see Shepherd et al. (59) for further detail], some of which are vasoactive (16, 45, 56). Supplements rich in antioxidants have also been shown to improve redox balance and improve vascular function (44). The reported reduction in [pan-endothelin] (Fig. 5A), with and without elevations in plasma [nitrite] (Fig. 2B), may have contributed to the improved endothelial function and reduced systolic and diastolic BP observed in the current study. There was also a small additional reduction in both systolic and diastolic BP after acute BJ compared with acute NDBJ supplementation. This can be explained, at least in part, by shifts in the oral microbiome reducing capacity following nitrate supplementation (33), meaning that the effect could be larger with acute versus chronic supplementation. This effect may also have been larger if BP was measured at 2.5 h after ingestion, to match peak plasma [nitrite] (68). Previously published studies in clinical populations that have observed a reduction in BP after BJ supplementation have also not used a true placebo, meaning that the antioxidant content was unlikely matched between conditions (5, 42), as was the case in the present study, and thus the effect of antioxidant/polyphenol-rich BJ on BP needs to be examined in more detail and rigor.

Cytokines and Antioxidant Enzymes

BJ is rich in antioxidants and polyphenols (58); however, the effects of BJ supplementation on systemic redox balance and inflammation have not been reported. There is some evidence to suggest that individuals suffering with Raynaud’s phenomenon have elevated systemic levels of inflammation and oxidative stress (6, 29). One previous study used exercise as a model to induce acute oxidative stress and inflammation, and reported no effect of 3 days of BJ (~210 mg) on [ROS] or [IL-10] versus an isocaloric placebo in healthy individuals (12). In the current study, we report that both 1 day and 2 wk of supplementation with BJ and NDBJ increased plasma [IL-10], but did not alter [IL-6]. An increase in plasma [IL-10] suggests that both BJ and NDBJ induced an anti-inflammatory effect in this population. The mechanism/s for this effect and whether it would remain after supplementation ceased or if individuals would need to continue supplementing daily is unclear. Post hoc analysis in our study revealed statistical differences in [IL-10] for primary but not secondary RP. Although we are not powered to detect these changes, future studies should examine the potential ergogenic effect of beetroot juice supplementation at different levels of disease severity and, in particular, inflammatory status. Two weeks of supplementation with BJ did not alter the concentration of markers of oxidative stress (PRDX-4, TRX-1, and SOD3). PRDX-4 and TRX-1 are endogenous antioxidant enzymes, which are secreted into the extracellular environment (i.e., plasma) in response to elevated intracellular oxidative stress; while SOD3 is an extracellular antioxidant enzyme anchored to the membrane of cells to eliminate superoxide anions (i.e., ROS) directly within the extracellular space. A growing body of evidence now supports a role for PRDX, TRX, and SOD3 in regulating the inflammatory response (23, 34, 35). Although these markers were unaltered following 2 wk of supplementation in the present study, this does not preclude the possibility that longer-term supplementation with BJ or NDBJ may reduce these and other markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in this population.

Qualitative Interviews

Participants’ accounts support the statistical findings from this study that blood flow increased in the hands, with one participant stating they felt their “blood vessels open up.” One participant suggested that they felt ill, which coincides with the reported adverse events including headaches and hot flushes. It is theoretically possible this may be due to increased blood flow to the brain (40) and increased skin perfusion (47), which may lead to side effects in a similar way to organic nitrates (66). Conversely, one participant was happy to recommend the juice and enjoyed the taste. Two individuals with scleroderma reported gastrointestinal distress; however, this may be related to their condition (20). Larger trials are needed to establish rates of adverse effects following BJ supplementation.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Work

A strength of this research was its robust experimental design (double-blind, randomized, crossover trial). Several limitations do, however, warrant discussion. First, the qualitative interviews were conducted between 2 and 12 wk following participants’ completion of the study, which may limit the accuracy of recall in some cases. We may also have missed the peak BP effects as BP was taken at 1.5 h after ingestion. The sample size was relatively small and nonhomogeneous, including a spread of primary and secondary conditions. As a consequence, it was not possible to examine differences between these groups to determine whether one group may potentially benefit more from BJ supplementation. NO responsiveness and metabolism are known to be reduced in older individuals (51, 63); we therefore cannot preclude that the effect seen in this study would be larger in a group of younger individuals with primary RP. A larger definitive trial, examining the efficacy of BJ supplementation, is therefore needed in individuals with RP. Given these results it appears that BJ supplementation may indeed offer an inexpensive intervention to improve endothelial (dys)function in individuals with RP.

Conclusions

This is the first study to examine the effect of dietary nitrate supplementation on extremity rewarming, endothelial function, and BP in individuals with RP. We show that both BJ and NDBJ increased blood flow in the thumb following a cold challenge; improved endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilation in the forearm; and reduced systolic and diastolic BP in comparison to baseline. These effects appear to be linked, at least in part, to reduced inflammatory markers. Efficacy trials are warranted to verify these findings.

GRANTS

We gratefully acknowledge the funding from the University of Portsmouth and James White Drinks Ltd. All other authors declare no conflict of interest. This research was supported by the the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre.

DISCLAIMERS

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service (NHS), the NIHR or the Department of Health.

DISCLOSURES

M. Gilchrist received funding from James White Drinks Ltd for development of the placebo. No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by any of the other authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.I.S., J.T.C., S.J.B., S.Y.-M., M.G., P.G., Z.L.S., and C.M.E. conceived and designed research; A.I.S., J.T.C., A.J.W., H.M., D.W., P.G., H.C.M., and C.M.E. performed experiments; A.I.S., J.T.C., S.J.B., N.C.B., A.J.W., H.M., D.W., P.G., H.C.M., and C.M.E. analyzed data; A.I.S., J.T.C., S.J.B., N.C.B., A.J.W., S.Y.-M., M.G., P.G., Z.L.S., H.C.M., and C.M.E. interpreted results of experiments; A.I.S. and C.M.E. prepared figures; A.I.S., S.Y.-M., M.G., P.G., Z.L.S., H.C.M., and C.M.E. drafted manuscript; A.I.S., J.T.C., S.J.B., N.C.B., A.J.W., S.Y.-M., M.G., H.M., D.W., P.G., Z.L.S., H.C.M., and C.M.E. edited and revised manuscript; A.I.S., J.T.C., S.J.B., N.C.B., A.J.W., S.Y.-M., M.G., H.M., D.W., P.G., Z.L.S., H.C.M., and C.M.E. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the participants who volunteered to take part in this. We also thank the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network for adopting this study onto their portfolio, and the research nurses (Rheumatology Department, Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth; Paula White and Marie White) who supported participant recruitment. We acknowledge help with data collection/analysis from Freyja Haigh.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson ME, Moore TL, Hollis S, Jayson MI, King TA, Herrick AL. Digital vascular response to topical glyceryl trinitrate, as measured by laser Doppler imaging, in primary Raynaud’s phenomenon and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 41: 324–328, 2002. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bach AJ, Stewart IB, Minett GM, Costello JT. Does the technique employed for skin temperature assessment alter outcomes? A systematic review. Physiol Meas 36: R27–R51, 2015. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/36/9/R27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bateman RM, Ellis CG, Freeman DJ. Optimization of nitric oxide chemiluminescence operating conditions for measurement of plasma nitrite and nitrate. Clin Chem 48: 570–573, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamin N, O’Driscoll F, Dougall H, Duncan C, Smith L, Golden M, McKenzie H. Stomach NO synthesis. Nature 368: 502, 1994. doi: 10.1038/368502a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berry MJ, Justus NW, Hauser JI, Case AH, Helms CC, Basu S, Rogers Z, Lewis MT, Miller GD. Dietary nitrate supplementation improves exercise performance and decreases blood pressure in COPD patients. Nitric Oxide, 48: 22–30, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biondi R, Coaccioli S, Lattanzi S, Puxeddu A, Papini M. Oxidant/antioxidant status in patients with Raynaud’s disease. Clin Ter 159: 77–81, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3: 77–101, 2006. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryan NS, Hord NG. Dietary nitrate and nitrites: the physiological context for potential health benefits. In: Food, Nutrition, and the Nitric Oxide Pathway: Biochemistry and Bioactivity, edited by Bryan NS. Lancaster, PA: DEStech Publications, 2010, p. 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buga GM, Gold ME, Fukuto JM, Ignarro LJ. Shear stress-induced release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells grown on beads. Hypertension 17: 187–193, 1991. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.17.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bunker CB, Goldsmith PC, Leslie TA, Hayes N, Foreman JC, Dowd PM. Calcitonin gene-related peptide, endothelin-1, the cutaneous microvasculature and Raynaud’s phenomenon. Br J Dermatol 134: 399–406, 1996. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb16221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlström M, Liu M, Yang T, Zollbrecht C, Huang L, Peleli M, Borniquel S, Kishikawa H, Hezel M, Persson AEG, Weitzberg E, Lundberg JO. Cross-talk Between Nitrate-Nitrite-NO and NO Synthase Pathways in Control of Vascular NO Homeostasis. Antioxid Redox Signal 23: 295–306, 2015. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clifford T, Bowman A, Capper T, Allerton DM, Foster E, Birch-Machin M, Lietz G, Howatson G, Stevenson EJ. A pilot study investigating reactive oxygen species production in capillary blood after a marathon and the influence of an antioxidant-rich beetroot juice. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 43: 303–306, 2018. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2017-0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cosby K, Partovi K, Crawford JH, Patel RP, Reiter CD, Martyr S, Yang BK, Waclawiw MA, Zalos G, Xu X, Huang KT, Shields H, Kim-Shapiro DB, Schechter AN, Cannon RO, Gladwin MT. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodiltaes the human circulation. Nat Med 9: 1498–1505, 2003. doi: 10.1038/nm954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davey M, Eglin C, House J, Tipton M. The contribution of blood flow to the skin temperature responses during a cold sensitivity test. Eur J Appl Physiol 113: 2411–2417, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00421-013-2678-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duncan C, Dougall H, Johnston P, Green S, Brogan R, Leifert C, Smith L, Golden M, Benjamin N. Chemical generation of nitric oxide in the mouth from the enterosalivary circulation of dietary nitrate. Nat Med 1: 546–551, 1995. doi: 10.1038/nm0695-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egert S, Bosy-Westphal A, Seiberl J, Kürbitz C, Settler U, Plachta-Danielzik S, Wagner AE, Frank J, Schrezenmeir J, Rimbach G, Wolffram S, Müller MJ. Quercetin reduces systolic blood pressure and plasma oxidised low-density lipoprotein concentrations in overweight subjects with a high-cardiovascular disease risk phenotype: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Br J Nutr 102: 1065–1074, 2009. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509359127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eglin CM, Costello JT, Bailey SJ, Gilchrist M, Massey H, Shepherd AI. Effects of dietary nitrate supplementation on the response to extremity cooling and endothelial function in individuals with cold sensitivity. A double blind, placebo controlled, crossover, randomised control trial. Nitric Oxide 70: 76–85, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eglin CM, Golden FS, Tipton MJ. Cold sensitivity test for individuals with non-freezing cold injury: the effect of prior exercise. Extrem Physiol Med 2: 16, 2013. doi: 10.1186/2046-7648-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreira-Valente MA, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Jensen MP. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain 152: 2399–2404, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forbes A, Marie I. Gastrointestinal complications: the most frequent internal complications of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 48, Suppl 3: iii36–iii39, 2009. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Förstermann U, Sessa WC. Nitric oxide synthases: regulation and function. Eur Heart J 33: 829–837, 2012. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao X, Yang T, Liu M, Peleli M, Zollbrecht C, Weitzberg E, Lundberg JO, Persson AEG, Carlström M. NADPH oxidase in the renal microvasculature is a primary target for blood pressure-lowering effects by inorganic nitrate and nitrite. Hypertension 65: 161–170, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerrits EG, Alkhalaf A, Landman GW, van Hateren KJ, Groenier KH, Struck J, Schulte J, Gans RO, Bakker SJ, Kleefstra N, Bilo HJ. Serum peroxiredoxin 4: a marker of oxidative stress associated with mortality in type 2 diabetes (ZODIAC-28). PLoS One 9: e89719, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilchrist M, Winyard PG, Benjamin N. Dietary nitrate--good or bad? Nitric Oxide 22: 104–109, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilchrist M, Winyard PG, Aizawa K, Anning C, Shore A, Benjamin N. Effect of dietary nitrate on blood pressure, endothelial function, and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med 60: 89–97, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gottfredsen RH, Tran SM-H, Larsen UG, Madsen P, Nielsen MS, Enghild JJ, Petersen SV. The C-terminal proteolytic processing of extracellular superoxide dismutase is redox regulated. Free Radic Biol Med 52: 191–197, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.10.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Govoni M, Jansson EÅ, Weitzberg E, Lundberg JO. The increase in plasma nitrite after a dietary nitrate load is markedly attenuated by an antibacterial mouthwash. Nitric Oxide 19: 333–337, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenstein D, Gupta NK, Martin P, Walker DR, Kester RC. Impaired thermoregulation in Raynaud’s phenomenon. Angiology 46: 603–611, 1995. doi: 10.1177/000331979504600707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gualtierotti R, Ingegnoli F, Griffini S, Grovetti E, Borghi MO, Bucciarelli P, Meroni PL, Cugno M. Detection of early endothelial damage in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon. Microvasc Res 113: 22–28, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hertzog MA. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res Nurs Health 31: 180–191, 2008. doi: 10.1002/nur.20247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holowatz LA, Thompson-Torgerson CS, Kenney WL. The human cutaneous circulation as a model of generalized microvascular function. J Appl Physiol (1985) 105: 370–372, 2008. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00858.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hope K, Eglin C, Golden F, Tipton M. Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate and the peripheral thermal responses in normal and cold-sensitive individuals. Microvasc Res 91: 84–89, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyde ER, Luk B, Cron S, Kusic L, McCue T, Bauch T, Kaplan H, Tribble G, Petrosino JF, Bryan NS. Characterization of the rat oral microbiome and the effects of dietary nitrate. Free Radic Biol Med 77: 249–257, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iversen MB, Gottfredsen RH, Larsen UG, Enghild JJ, Praetorius J, Borregaard N, Petersen SV. Extracellular superoxide dismutase is present in secretory vesicles of human neutrophils and released upon stimulation. Free Radic Biol Med 97: 478–488, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jin D-Y, Chae HZ, Rhee SG, Jeang K-T. Regulatory role for a novel human thioredoxin peroxidase in NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem 272: 30952–30961, 1997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jonvik KL, Nyakayiru J, Pinckaers PJ, Senden JM, van Loon LJ, Verdijk LB. Nitrate-Rich Vegetables Increase Plasma Nitrate and Nitrite Concentrations and Lower Blood Pressure in Healthy Adults. J Nutr 146: 986–993, 2016. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.229807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joris PJ, Mensink RP. Beetroot juice improves in overweight and slightly obese men postprandial endothelial function after consumption of a mixed meal. Atherosclerosis 231: 78–83, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kahaleh MB, LeRoy EC. Vascular factors in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. In: Systemic Sclerosis: Scleroderma. Chichester: Wiley, 1988, p. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kapil V, Khambata RS, Robertson A, Caulfield MJ, Ahluwalia A. Dietary nitrate provides sustained blood pressure lowering in hypertensive patients: a randomized, phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Hypertension 65: 320–327, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly J, Fulford J, Vanhatalo A, Blackwell JR, French O, Bailey SJ, Gilchrist M, Winyard PG, Jones AM. Effects of short-term dietary nitrate supplementation on blood pressure, O2 uptake kinetics, and muscle and cognitive function in older adults. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 304: R73–R83, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00406.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kenjale AA, Ham KL, Stabler T, Robbins JL, Johnson JL, Vanbruggen M, Privette G, Yim E, Kraus WE, Allen JD. Dietary nitrate supplementation enhances exercise performance in peripheral arterial disease. J Appl Physiol (1985) 110: 1582–1591, 2011. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00071.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kerley CP, Cahill K, Bolger K, McGowan A, Burke C, Faul J, Cormican L. Dietary nitrate supplementation in COPD: an acute, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Nitric Oxide 44: 105–111, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khan F, Belch JJ. Skin blood flow in patients with systemic sclerosis and Raynaud’s phenomenon: effects of oral L-arginine supplementation. J Rheumatol 26: 2389–2394, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khan F, Ray S, Craigie AM, Kennedy G, Hill A, Barton KL, Broughton J, Belch JJ. Lowering of oxidative stress improves endothelial function in healthy subjects with habitually low intake of fruit and vegetables: a randomized controlled trial of antioxidant- and polyphenol-rich blackcurrant juice. Free Radic Biol Med 72: 232–237, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koltuksuz U, Özen S, Uz E, Aydinç M, Karaman A, Gültek A, Akyol O, Gürsoy MH, Aydin E. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester prevents intestinal reperfusion injury in rats. J Pediatr Surg 34: 1458–1462, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(99)90103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lara J, Ashor AW, Oggioni C, Ahluwalia A, Mathers JC, Siervo M. Effects of inorganic nitrate and beetroot supplementation on endothelial function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr 55: 451–459, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-0872-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levitt EL, Keen JT, Wong BJ. Augmented reflex cutaneous vasodilatation following short-term dietary nitrate supplementation in humans. Exp Physiol 100: 708–718, 2015. doi: 10.1113/EP085061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li H, Förstermann U. Uncoupling of endothelial NO synthase in atherosclerosis and vascular disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol 13: 161–167, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 7: 156–167, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nrd2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Minson CT, Holowatz LA, Wong BJ, Kenney WL, Wilkins BW. Decreased nitric oxide- and axon reflex-mediated cutaneous vasodilation with age during local heating. J Appl Physiol (1985) 93: 1644–1649, 2002. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00229.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moncada S, Higgs A. The L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway. N Engl J Med 329: 2002–2012, 1993. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moreira DG, Costello JT, Brito CJ, Adamczyk JG, Ammer K, Bach AJE, Costa CMA, Eglin C, Fernandes AA, Fernández-Cuevas I, Ferreira JJA, Formenti D, Fournet D, Havenith G, Howell K, Jung A, Kenny GP, Kolosovas-Machuca ES, Maley MJ, Merla A, Pascoe DD, Priego Quesada JI, Schwartz RG, Seixas ARD, Selfe J, Vainer BG, Sillero-Quintana M. Thermographic imaging in sports and exercise medicine: A Delphi study and consensus statement on the measurement of human skin temperature. J Therm Biol 69: 155–162, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Needleman P, Johnson EM Jr. Mechanism of tolerance development to organic nitrates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 184: 709–715, 1973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Norrbrand L, Kölegård R, Keramidas ME, Mekjavic IB, Eiken O. No association between hand and foot temperature responses during local cold stress and rewarming. Eur J Appl Physiol 117: 1141–1153, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00421-017-3601-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ochiai R, Jokura H, Suzuki A, Tokimitsu I, Ohishi M, Komai N, Rakugi H, Ogihara T. Green coffee bean extract improves human vasoreactivity. Hypertens Res 27: 731–737, 2004. doi: 10.1291/hypres.27.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Omar SA, Artime E, Webb AJ. A comparison of organic and inorganic nitrates/nitrites. Nitric Oxide 26: 229–240, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shepherd AI, Gilchrist M, Winyard PG, Jones AM, Hallmann E, Kazimierczak R, Rembialkowska E, Benjamin N, Shore AC, Wilkerson DP. Effects of dietary nitrate supplementation on the oxygen cost of exercise and walking performance in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. Free Radic Biol Med 86: 200–208, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shepherd AI, Wilkerson DP, Dobson L, Kelly J, Winyard PG, Jones AM, Benjamin N, Shore AC, Gilchrist M. The effect of dietary nitrate supplementation on the oxygen cost of cycling, walking performance and resting blood pressure in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A double blind placebo controlled, randomised control trial. Nitric Oxide 48: 31–37, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shepherd AI, Wilkerson DP, Fulford J, Winyard PG, Benjamin N, Shore AC, Gilchrist M. Effect of nitrate supplementation on hepatic blood flow and glucose homeostasis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized control trial. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 311: G356–G364, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00203.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith TP, Haymond T, Smith SN, Sweitzer SM. Evidence for the endothelin system as an emerging therapeutic target for the treatment of chronic pain. J Pain Res 7: 531–545, 2014. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S65923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tanaka A, Yamazaki M, Saito M, Oh-I T, Watanabe Y, Tsuboi R. Highly sensitive high-pressure liquid chromatography with ultraviolet light method detected the reduction of serum nitrite/nitrate levels after cold exposure in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Dermatol 39: 889–890, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tschudi MR, Barton M, Bersinger NA, Moreau P, Cosentino F, Noll G, Malinski T, Lüscher TF. Effect of age on kinetics of nitric oxide release in rat aorta and pulmonary artery. J Clin Invest 98: 899–905, 1996. doi: 10.1172/JCI118872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tucker AT, Pearson RM, Cooke ED, Benjamin N. Effect of nitric-oxide-generating system on microcirculatory blood flow in skin of patients with severe Raynaud’s syndrome: a randomised trial. Lancet 354: 1670–1675, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wadley AJ, Veldhuijzen van Zanten JJCS, Aldred S. The interactions of oxidative stress and inflammation with vascular dysfunction in ageing: the vascular health triad. Age (Dordr) 35: 705–718, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9402-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wigley FM. Clinical practice. Raynaud’s Phenomenon. N Engl J Med 347: 1001–1008, 2002. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp013013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wootton-Beard PC, Ryan L. Combined use of multiple methodologies for the measurement of total antioxidant capacity in UK commercially available vegetable juices. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 67: 142–147, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s11130-012-0287-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wylie LJ, Kelly J, Bailey SJ, Blackwell JR, Skiba PF, Winyard PG, Jeukendrup AE, Vanhatalo A, Jones AM. Beetroot juice and exercise: pharmacodynamic and dose-response relationships. J Appl Physiol (1985) 115: 325–336, 2013. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00372.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zamani P, Rawat D, Shiva-Kumar P, Geraci S, Bhuva R, Konda P, Doulias PT, Ischiropoulos H, Townsend RR, Margulies KB, Cappola TP, Poole DC, Chirinos JA. Effect of inorganic nitrate on exercise capacity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 131: 371–380, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang H, Huizenga C, Arens E, Wang D. Thermal sensation and comfort in transient non-uniform thermal environments. Eur J Appl Physiol 92: 728–733, 2004. doi: 10.1007/s00421-004-1137-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]