Abstract

Skeletal muscle satellite cells (SC) play an important role in muscle repair following injury. The regulation of SC activity is governed by myogenic regulatory factors (MRF), including MyoD, Myf5, myogenin, and MRF4. The mRNA expression of these MRF in humans following muscle damage has been predominately measured in whole muscle homogenates. Whether the temporal expression of MRF in a whole muscle homogenate reflects SC-specific expression of MRF remains largely unknown. Sixteen young men (23.1 ± 1.0 yr) performed 300 unilateral eccentric contractions (180°/s) of the knee extensors. Percutaneous muscle biopsies from the vastus lateralis were taken before (Pre) and 48 h postexercise. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis was utilized to purify NCAM+ muscle SC from the whole muscle homogenate. Forty-eight hours post-eccentric exercise, MyoD, Myf5, and myogenin mRNA expression were increased in the whole muscle homogenate (~1.4-, ~4.0-, ~1.7-fold, respectively, P < 0.05) and in isolated SC (~19.3-, ~17.5-, ~58.9-fold, respectively, P < 0.05). MRF4 mRNA expression was not increased 48 h postexercise in the whole muscle homogenate (P > 0.05) or in isolated SC (P > 0.05). In conclusion, our results suggest that the directional changes in mRNA expression of the MRF in a whole muscle homogenate in response to acute eccentric exercise reflects that observed in isolated muscle SC.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The myogenic program is controlled via transcription factors referred to as myogenic regulatory factors (MRF). Previous studies have derived MRF expression from whole muscle homogenates, but little work has examined whether the mRNA expression of these transcripts reflects the pattern of expression in the actual population of satellite cells (SC). We report that MRF expression from an enriched SC population reflects the directional pattern of expression from skeletal muscle biopsy samples following eccentric contractions.

Keywords: fluorescence-activated cell sorting, mRNA expression, myogenic regulator factors, satellite cell

INTRODUCTION

Postmitotic, adult skeletal muscle has the capacity for extensive regeneration and repair. Resident muscle stem cells, referred to as satellite cells (SC), located on the periphery of the muscle fiber, are primarily responsible for mediating this process (29, 53). Following stimulation, SC exit quiescence and progress through the myogenic program, governed by a network of transcription factors collectively referred to as the myogenic regulatory factors (MRF). The upregulation of the MRF Myf5 and MyoD induce activation and/or proliferation of SC (14, 24), whereas differentiation is driven by the upregulation of myogenin and MRF4 (15, 52), ultimately resulting in the contribution of nuclei to existing myofibers to aid in repair and adaptation.

The time course of SC activation through differentiation has previously been described in humans following acute bouts of resistance exercise (6, 40) or in response to eccentric contraction-induced muscle damage (33).The majority of these studies measured mRNA expression of the MRF in whole muscle (i.e., homogenate from a muscle biopsy) as an indication of SC activity and progression through the myogenic program (45). Previous descriptions of MRF expression derived from whole muscle are assumed to be meaningful for our understanding of SC biology, but whether whole muscle expression patterns are reflective of SC-specific expression is unclear. It is possible that non-SC MRF gene expression could contribute to whole muscle MRF expression, limiting the interpretation of whole-muscle MRF expression (43). The limitations of using mRNA expression from whole muscle samples as a surrogate of cell-specific responses has recently been highlighted (20, 37, 38). Miller and colleagues (37) suggest that mRNA expression derived from mixed sources, as a measure identifying a highly regulated sequence of events, such as those found in the myogenic program, may be inaccurate. Furthermore, Kirby et al. (23) determined that the predominant source of MRF RNA may be myonuclear, and not muscle, SC. There appears to be a marked paucity in the literature regarding whether MRF typically derived from whole muscle samples are indeed a reflection of what is occurring in the muscle resident SC pool itself.

Flow cytometry has been used to successfully purify cell populations from a mixed cell sample. In humans, multiple studies have used different criteria to sort muscle SC, including Pax7 (33), the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) (19, 41, 42, 48, 50), and more recently CD82 (2). However, few have used flow sorting to assess mRNA expression in an enriched population of muscle SC before any cell culture passages that may alter gene expression. Furthermore, little work has been done to verify whether the expression of MRF mRNA in whole muscle is reflective of the pattern of expression in enriched SC. Therefore, we proposed to examine whether MRF expression, in isolated SC following eccentric contractions, is representative of whole muscle samples.

METHODS

Participants.

Sixteen healthy young men (23.0 ± 1.0 yr; means ± SE) who were recreationally active were recruited to participate in the study. Participants were required to complete a routine screen and health questionnaire. Exclusion criteria included smoking, diabetes, the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and/or statins, and history of respiratory disease and/or any major orthopedic disability. Participants were told to refrain from exercising throughout the time course of the study. The study was approved by the Hamilton Health Sciences Integrated Research Ethics Board (project approval no. 12-330) and conformed to the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants gave their informed written consent before being enrolled in the study.

Eccentric muscle damage protocol.

Maximal isokinetic unilateral muscle-lengthening contractions of the quadriceps were performed using a Biodex dynamometer (Biodex-System 3, Biodex Medical Systems, Inc.) at 180°/s. For each participant, one leg was selected randomly to perform the exercise protocol described below. Movement at the shoulders, hips, and thigh were restrained with straps to isolate the knee extensors during the protocol. Immediately before the intervention, participants underwent a brief familiarization with the equipment, involving 5–10 submaximal lengthening contractions of the leg to be exercised. Participants were required to perform 30 sets of 10 maximal knee extensions with a 1-min rest between sets, for a total of 300 lengthening contractions. During each set, investigators provided verbal encouragement for the participants to complete and exert maximal force during each contraction. This protocol has been used previously to induce a significant level of skeletal muscle damage (5) and has been shown to elicit a significant SC response across multiple populations (10, 33).

Muscle biopsy sampling.

Forty-eight hours postexercise, participants arrived at the laboratory in the rested, fasting state. After an (~10 h) overnight fast, percutaneous needle biopsies were taken from the vastus lateralis in the exercise leg (Exercised; EX) and the non-exercise leg (Control; CTL) under local anesthetic using a 5-mm Bergstrom needle adapted for manual suction (7). Following collection, the sample was dissected free of adipose and connective tissue, divided into separate pieces for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; CTL: 88.9 ± 7.4 mg muscle tissue; EX: 92.0 ± 7.2 mg muscle tissue) and for direct RNA extraction from the whole muscle homogenate (CTL: 29.3 ± 1.4 mg muscle tissue; EX: 35.9 ± 3.4 mg muscle tissue). The muscle piece to be used for whole muscle homogenate mRNA extraction was immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. The muscle sample to be used for FACS was immediately placed in sterile ice-cold 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 10 mM, pH 7.4) for subsequent processing.

FACS and flow cytometry.

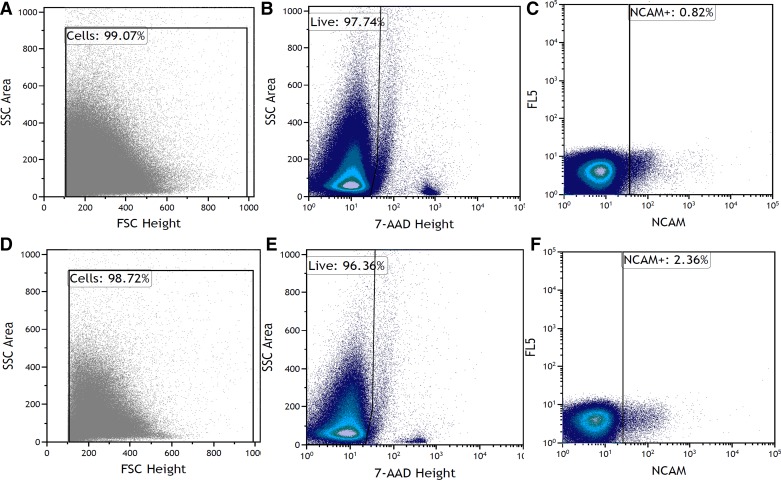

CTL and EX muscle biopsy tissue was prepared for FACS analysis using methods similar to published methods (1, 13, 35). After weighing, muscle samples were washed briefly with sterile ice-cold PBS to remove visible blood, and PBS was removed by suction. Samples were then aligned in a 3.5-mm tissue culture plate in a culture hood under sterile conditions. Using filter pipette tips throughout the process, 250 µL of a collagenase-dispase solution (10 mg/mL collagenase B, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany; 2.4 U/mL dispase, GIBCO/Invitrogen) was added to the plate, and the sample was mechanically dissociated through mulching. When adequately mulched, 500 µL of the collagenase-dispase solution was added to the plate, and the sample was transferred for 5 min in an incubator at 37°C. After removal from the incubator, the mixture was manually triturated through a 5- and 1-mL plastic serological pipette to further disrupt the tissue. The slurry was then filtered dropwise through a sterile 70-µm cell strainer (Sigma-Aldrich), which was pre-wet with 4% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 1× PBS, into a 50-mL conical bottom tube. The filter was then flushed with 20 mL of the 4% BSA in 1× PBS solution, to minimize the loss of cells to the filter. The cells were then filtered a second time through a pre-wet sterile 40-µm cell strainer (Sigma-Aldrich) and again flushed with 20 mL of 4% BSA in 1× PBS into a 50-mL conical bottom tube. The mixture was then centrifuged at 300 g for 8 min to obtain a pellet containing mononuclear cells. The pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of ice-cold sterile 1× PBS, and a 10-μL sample was taken for an unstained control population. Cells were then repelleted and resuspended in 2 mL of anti-human NCAM primary antibody [cell supernatant from hybridoma cells obtained from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB), University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA]. After incubation for 45 min in the dark on ice (with a gentle agitation every 10 min), cells were pelleted and washed twice with ice-cold 0.5% BSA in 1× PBS. Cells were then pelleted and resuspended in 2 mL of the appropriate secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 647; 1:500, Invitrogen) for 20 min in the dark on ice (with a gentle agitation every 10 min). After incubation in the secondary antibody, cells were then pelleted and washed several times before being resuspended in 0.5% BSA in 1× PBS before cell sorting. Mouse IgG CompBeads (BD, San Jose, CA) were used for compensation, and the viability dye 7-AAD (1:10, Beckman Coulter) was added in samples to exclude dead cells. A MoFlo XDP Cell Sorter was used to analyze/sort samples, and Kaluza software (Beckman Coulter, Mississauga, ON) was used for analysis. Purity checks for NCAM expression after sorting was performed. Optical alignments and fluidics of the cytometer (using Flow-Check fluorospheres, Beckman Coulter) were verified daily, and optimum instrument settings were verified (SPHERO Ultra Rainbow Fluorescent Particles, Spherotech) daily by a trained technician. Gating strategies were optimized through multiple experiments, including an unstained control for every sample as well as a secondary only. The NCAM+ population was distinct from the NCAM− population. Additionally, the gates were set to include only viable cells through 7-AAD staining. The population of interest exhibited characteristics of wide side- and forward-scatter, which has been observed previously (33). The SC pool may exhibit various cytoplasmic and/or organelle volume depending on activity status (11). Evidence also suggests that NCAM expression may be heterogenous among cell populations (9), and thus repeated running of controls throughout the study helped ensure the consistency of our gating strategy. Representative NCAM+ cell sorting via flow cytometry of the skeletal muscle biopsy can be found in Fig. 1, A–C (representative of Pre) and Fig. 1, D–F (representative of Post; 48 h post-eccentric contractions) as a flow plot.

Fig. 1.

Representative NCAM+ population in skeletal muscle biopsy sorted via flow cytometry. Forward scatter (FSC; x-axis) and side scatter (SSC; y-axis) were used to select a population of cells with 7-AAD viability dye to exclude nonviable cells. NCAM+-viable cells are represented in AF647 channel (x-axis) against a dump channel (y-axis). Cell populations representative of before exercise (A–C) and 48 h post-eccentric exercise (D–F) are shown.

Myogenic properties of the sorted cells.

To confirm that the sorted cells were indeed muscle SC, we costained the NCAM+ cell population with antibodies against Pax7 (neat; cell supernatant from cells obtained from the DSHB) and desmin (ab6322, 1:500, Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Mononuclear cells were isolated from muscle biopsies, and then FACS-sorted NCAM+ cells were pelleted and then resuspended in 30 µL of 1× PBS. The cells were then transferred onto Poly-Prep Slides (poly-l-lysine-coated glass slides, Sigma-Aldrich) and then cytospun (StatSpin Cytofuge 2, IRIS International, Chatsworth, CA) at a low speed for 6 min for immunocytochemistry of Pax7 and/or desmin expression. In brief, following two 3-min gentle washes in 1× PBS, the slides were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min followed by three 5-min washes in PBS. Slides were then blocked with 5% goat serum in 1% BSA for 30 min. The block was tipped off, before the application of the primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Following three 5-min washes in 1× PBS, slides were incubated with an appropriate secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 594; 1:500, in 1% BSA, Molecular Probes/Invitrogen). Slides were then treated with DAPI (1:20,000, Sigma-Aldrich) for nuclear staining and then washed with 1× PBS. Stained slides were viewed with a Nikon Eclipse 90i Microscope (Nikon Instruments, Inc., Melville, NY), and images were captured and analyzed using NIS Elements 4.0 software (Nikon Instruments).The mononuclear cell preparation served as an additional confirmation that the sorted NCAM+ cells were indeed satellite cells (Pax7+) and of myogenic lineage (desmin+). These experiments were performed in a mix of the CTL (before eccentric contractions; Pre) and EX leg (48 h following eccentric contractions) for NCAM+/Pax7+ (n = 4) and NCAM+/desmin+ in a subset of participants (n = 2).

RNA isolation from the whole muscle homogenate.

RNA was isolated from muscle using the TRIzol method. All samples were homogenized with 1 mL of TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies, Burlington, ON), in Lysing Maxtrix D tubes (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH), with a FastPrep-24 Tissue and Cell Homogenizer (MP Biomedicals) for a duration of 40 s at a setting of 6 m/s. Following a 5-min room temperature incubation, homogenized samples were stored at −80°C for 1 mo until further processing. After thawing on ice, 200 µL of chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON) was added to each sample, mixed vigorously for 15 s, incubated at room temperature for 5 min, and spun at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The RNA (aqueous) phase was purified using an E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit 1 (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration (ng/mL) and purity (260/280) were determined with a Nano-Drop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockville, MD).

RNA isolation from isolated human SC.

Cells were isolated via FACS into sterile 1.5-mL tubes that had been coated overnight with 4% BSA in 1× PBS. Following sorting, the cells were spun down at 300 g for 8 min, and then washed with ice cold 1 × PBS. The cells were then repelleted, PBS aspirated, and 1 mL of TRIzol Reagent was added, and then the cells were lysed using repetitive pipetting. The cells were incubated for 5 min, before the addition of 200 µL of chloroform, and was mixed via pipetting. The sample was then incubated for 10 min, before being spun down at 12,000 g for 10 min. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new sterile 1.5-ml tube, and a 1:1 ratio of ice-cold isopropanol. The addition of 15 µg GlycoBlue Coprecipitant (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to the solution, followed by a brief mix by pipetting and then a 10-min incubation. The RNA (aqueous) phase of the sorted cells was then purified using the ReliaPrep RNA cell miniprep system (Promega Corp., Madison, WI), following the manufacturer's instructions pertaining to small cell numbers. RNA concentration (ng/ml) and purity (260/280) were determined with a Nano-Drop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Reverse transcription.

Samples were reverse transcribed within 48 h of RNA isolation using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in 20-μl reaction volumes, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using an Eppendorf Mastercycler epGradient Thermal Cycler (Eppendorf, Mississauga, ON) to obtain cDNA for gene expression analysis.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

All quantitative (q) PCR reactions were run in duplicate in 25-µl volumes containing RT Sybr Green qPCR Master Mix (Qiagen Sciences, Valencia, CA), prepared with the epMotion 5075 Eppendorf automated pipetting system, and carried out using an Eppendorf Realplex2 Master Cycler epgradient. Primers are listed in Table 1 and were resuspended in 1× TE buffer (10 mM Tris·HCl and 0.11 mM EDTA) and stored at −20°C before use. Changes in mRNA gene expression were analyzed using the 2−∆Ct method, as previously described (47a). Briefly, Ct values were first normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH (Table 1); qRT-PCR reactions were carried out using the Eppendorf Mastercycler ep realplex2 real-time PCR System. mRNA values are expressed as total mRNA expression (means ± SE, arbitrary units). To verify validity of the housekeeper, it was determined that GAPDH was not different between CTL and EX (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Primer sequences for quantitative real-time PCR analysis

| Gene Name | Forward Primer Sequence (5′-3′) | Reverse Primer Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | CCTCCTGCACCACCAACTGCTT | GAGGGGCCATCCACAGTCTTCT |

| Myf5 | ATGGACGTGATGGATGGCTG | GCGGCACAAACTCGTCCCCAA |

| MyoD | GGTCCCTCGCGCCCAAAAGAT | CAGTTCTCCCGCCTCTCCTAC |

| Myogenin | CAGTGCACTGGAGTTCAGCG | TTCATCTGGGAAGGCCACAGA |

| MRF4 | CCCCTTCAGCTACAGACCCAA | CCCCCTGGAATGATCGGAAAC |

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Myf5, myogenic factor-5; MyoD, myogenic determination factor; MRF4, myogenic regulatory factor-4.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaStat 3.1.0 analysis software (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Comparisons of MRF gene expression between the CTL and EX (48 h post-eccentric exercise) muscle samples were performed with Student’s t test within each sample type (i.e., whole muscle or sorted NCAM+ cells).

RESULTS

Participant demographics and response to eccentric contraction-induced muscle damage.

Participant characteristics are listed in Table 2. Following 300 eccentric contractions at 48 h postexercise, force production was 260 ± 21 N·m compared with 302 ± 21 N·m at the Pre time point (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Anthropometric data

| Healthy Young Men (n = 16) | |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | 23 ± 1 |

| Body mass, kg | 82 ± 3 |

| Height, m | 1.79 ± 0.01 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.9 ± 0.89 |

Whole muscle mRNA expression.

In whole muscle, MyoD, Myf5, and myogenin mRNA expression were significantly increased at 48 h (~1.4-, ~4.0-, ~1.7-fold, respectively) following the single bout of eccentric contractions compared with Pre (Fig. 2, P < 0.05). There were no significant changes in MRF4 expression from Pre to 48 h postexercise (~0.9-fold, P > 0.05) in the whole muscle sample.

Fig. 2.

Myogenic regulatory factor (MRF) changes 48 h following eccentric damage in both isolated purified NCAM+ cells and a whole muscle (W.M) homogenate. Shown are MyoD (A and E, respectively), Myf5 (B and F, respectively), MRF4 (C and G, respectively), and myogenin (D and H, respectively) mRNA expression. Data are normalized to GAPDH. Values are means ± SE and reported as arbitrary units (a.u). *Significantly different compared with Pre (P < 0.05).

Isolated muscle SC mRNA expression.

In isolated muscle SC, MyoD, Myf5, and myogenin mRNA expression were significantly increased at 48 h (~19.3-, ~17.5-, ~58.9-fold, respectively) following the single bout of eccentric contractions compared with Pre (Fig. 3, P < 0.05). There was no significant change in MRF4 gene expression from Pre to 48 h postexercise (~4.0-fold, P > 0.05) in isolated muscle SC.

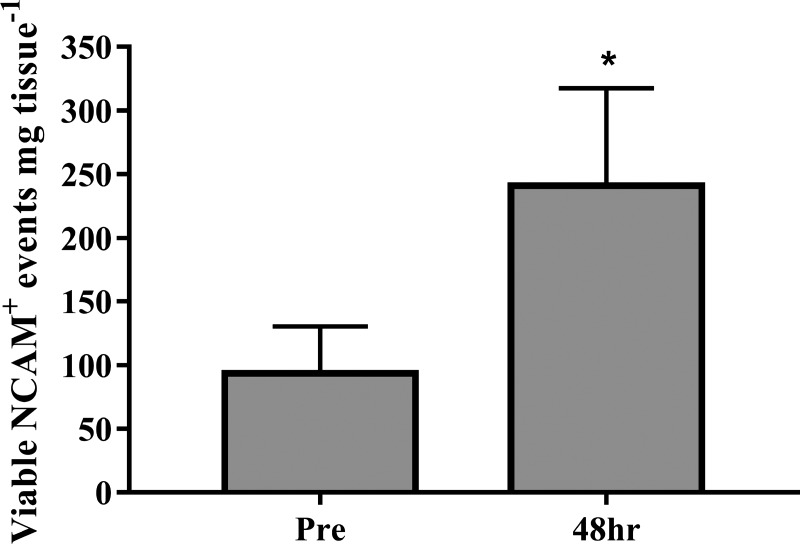

Fig. 3.

NCAM+ events/mg of fresh muscle tissue assessed via flow cytometry before (Pre) and 48 h (Post) after a bout of eccentric contraction-induced muscle damage. *Post was significantly different compared with Pre (P < 0.05).

SC content and population verification.

The number of NCAM+ cells/mg of fresh muscle tissue was analyzed via flow cytometry before (Pre) and 48 h after the bout of eccentric contraction induced muscle damage. The number of NCAM+ cells/mg increased by ~148% 48 h hours (241.2 ± 76.2 viable NCAM+ events/mg tissue) following damage compared with Pre (93.6 ± 36.7 viable NCAM+ events/mg tissue, P < 0.05, Fig. 3).

To confirm the NCAM+ population as human muscle SC, we performed a series of confirmation experiments utilizing immunohistochemistry. NCAM+ cells were sorted via FACS and then subsequently stained with Pax7. In identifying NCAM+ cells sorted (n = 4; 1,159 total cells counted), 93.1% of the NCAM+ cells were also positive for Pax7. Furthermore, to ensure that these cells were of myogenic lineage, we performed similar confirmatory experiments with NCAM+ cells sorted via FACS and then subsequently stained with desmin (a marker of myogenic commitment). Of NCAM+ cells sorted (n = 2; 117 SC counted), 94.8% of the NCAM+ cells were also positive for desmin.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we observed that following eccentric contractions, the MRF mRNA expression profile in whole muscle reflects that in FACS-enriched muscle SC. Therefore, we suggest that mRNA MRF expression from whole muscle reflects the muscle SC-specific expression of MRF in human skeletal muscle.

To investigate whether the increase in MRF mRNA expression in a whole muscle homogenate reflected that of isolated human muscle SC, we chose to induce muscle damage via eccentric muscle contractions. We are confident that our protocol was a sufficient stimulus to cause muscle damage with a significant ~15% reduction in force of the knee extensor muscle group 48 h postexercise. Similar protocols have induced significant muscle damage measured by creatine kinase, Z-band disruption, and force loss (5, 12, 31). Also, eccentric contractions are effective stimuli at inducing expansion of the muscle SC pool (10, 16, 17, 31, 32) and are also associated with changes in MRF expression from whole muscle (32, 39). While we did not quantify the SC pool via immunohistochemistry methods, NCAM+ events/mg tissue increased to ~150% of baseline as quantified using FACS. Furthermore, previous studies that did quantify the NCAM population in skeletal muscle sections have observed a significant increase in the SC pool following similar protocols (49).

SC are indispensable for the repair and/or regeneration of damaged muscle (25, 30, 47). Progression through the myogenic program is a highly orchestrated process controlled by the MRF, guiding SC from activation through proliferation and eventual differentiation (53). We observed that changes in mRNA expression of the MRFs (i.e., MyoD, Myf5, myogenin, and MRF4) occur in both a whole muscle homogenate and isolated SC following eccentric damage in humans. A visible increase in mRNA expression was observed in both isolated and/or enriched SCs and a whole muscle homogenate, lending credence to the notion that whole muscle MRF mRNA expression may reflect what is occurring specifically in SC. We highlight that no direct statistical comparison was made between the increase in MRF mRNA expression in isolated SC and the increase observed in the whole muscle homogenate. This is attributable to the notion that there may be a relatively heterogenous population of SC, in various stages of the myogenic program, found in both the FACs-enriched and the whole muscle homogenate. Additionally, the change in the mRNA expression of the purified cell population would be much larger in scale than that found within the whole muscle homogenate, impacting the variability in the comparison. This precludes direct statistical comparisons between the whole muscle homogenate and the isolated cells. Furthermore, the purpose of the present study was to simply observe whether the change in whole muscle mRNA expression is reflective of the expression measured in isolated SC. Together, our results suggest that the changes observed in MRF mRNA expression following eccentric exercise in a whole muscle homogenate is comparable to that of sorted SC in vivo humans.

MyoD, Myf5, and myogenin mRNA all increased in both whole muscle and isolated SC 48 h following eccentric contractions. Furthermore, no change in MRF4 mRNA expression was observed in either the whole muscle and isolated SC in response to the eccentric exercise session. The lack of change in MRF4 mRNA expression during post-exercise recovery can likely be explained by the specific timing of the muscle biopsy sampling. We have previously shown that MRF4 does not become significantly elevated following eccentric damage until 72 h postexercise in healthy young men (32). Additionally, recent work by Rodgers et al. (46) has suggested that there may be a systemic response to injury, with the signals from one damaged part of the body causing alterations to the SC pool in other parts. A shift of a subpopulation of SC into GAlert, a cellular state that may exhibit an enhanced ability to activate and to assist in tissue repair, has been observed in noninjured tissue (46). This work was performed in a mouse muscle injury model that was induced by intramuscular injection of BaCl2. Future work should address whether there is an impact on the transition of SC to GAlert and subsequent MRF expression following the initial biopsy in the nonexercised leg (Pre) in humans.

To our knowledge, this is the first assessment of MRF mRNA expression in isolated human muscle SC immediately following muscle biopsy sampling. While other studies have successfully sorted human SC via FACS utilizing similar criteria (i.e., NCAM positivity), the methodology used in those papers have incorporated extended culturing periods (19), thus precluding them from being assessed for mRNA expression similar to that found in vivo. Previous methodologies have utilized the FACS-based isolation of SC using Pax7 from fresh human tissue (33), but due to the nuclear location of Pax7 and the nature of the fixation process, the RNA from these cells may have been degraded during fixation or made resistant to extraction (18, 28).

Verification that the sorted NCAM+ population was indeed SC was assessed via Pax7 staining following the sort, where we observed that ~93% of the NCAM+ population was also Pax7+. Previous studies using immunohistochemistry-based SC quantification with either Pax7 or NCAM yielded similar results (26, 27, 51), and some studies have observed slight variations in SC quantification dependent on the marker used, which is thought to be due to differences in expression of Pax7 and NCAM during various stages of the myogenic program (8, 22). SC quantification using the different antibodies has yielded quantification within ~5% of each other (33). The small discrepancy between the NCAM+ and the Pax7+ populations is in line with enumeration data observed previously (26, 27, 36), which typically report an elevated NCAM+ content compared with Pax7 in a muscle cross section. NCAM positivity has been used extensively as a SC marker; however, it is also known to label degenerating muscle fibers and nerve endplates (21, 34, 44). NCAM is considered an excellent candidate for SC identification and quantification (26, 33, 49), but we performed additional immunohistochemistry to verify the population that was sorted. Myogenic commitment of NCAM+ muscle SC was verified using the muscle-specific intermediate filament protein desmin, which is known to be an early marker of myogenic lineage commitment (3). Desmin has previously been shown in different subpopulations of human SC (including those already committed to differentiation and those that are not) derived from muscle biopsies (4). We observed that of the NCAM+ cells, 94.8% were desmin positive, suggesting a similar level of commitment to the myogenic lineage observed when Pax7 has been used as a criterion for FACS (33). Taken together, these verification steps indicate that the isolated NCAM+ cells were largely an isolated population of muscle SC. By extension, we are confident that gene expression of MRFs in the NCAM+ population is derived from an isolated population of muscle SC.

We report that MRF gene expression from isolated NCAM+ SC in human muscle reflects the directional pattern of expression from whole muscle biopsy samples. Our findings support the notion that whole muscle MRF mRNA expression is a suitable reflection of SC-specific gene expression.

GRANTS

G. Parise was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Grant (1455843), and J. P. Nederveen was supported by an NSERC Canada Graduate Scholarship (CGS-D).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.P.N., S.A.F., J.M.B., T.S., S.J., and G.P. conceived and designed research; J.P.N., S.A.F., J.M.B., T.S., S.J., C.M., B.R.M., and D.K. performed experiments; J.P.N., S.A.F., J.M.B., T.S., and G.P. analyzed data; J.P.N., S.A.F., J.M.B., S.J., C.M., B.R.M., D.K., and G.P. interpreted results of experiments; J.P.N. and J.M.B. prepared figures; J.P.N., T.S., and C.M. drafted manuscript; J.P.N., S.A.F., J.M.B., T.S., S.J., C.M., B.R.M., D.K., and G.P. edited and revised manuscript; J.P.N., S.A.F., J.M.B., T.S., S.J., C.M., B.R.M., D.K., and G.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The NCAM 5B8 hybridoma cells were deposited by T. M. Jessell, J. Dodd, and S. Brenner-Morton; the Pax7 hybridoma cells were developed by A. Kawakami. The cells were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, created by the National Institute of Child Health and Development of the National Institutes of Health and maintained at the University of Iowa, Department of Biology (Iowa City, IA). The authors also thank Minomi Subapanditha and Dr. Sheila Singh for technical assistance with flow cytometry and FACS analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander CM, Puchalski J, Klos KS, Badders N, Ailles L, Kim CF, Dirks P, Smalley MJ. Separating stem cells by flow cytometry: reducing variability for solid tissues. Cell Stem Cell 5: 579–583, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander MS, Rozkalne A, Colletta A, Spinazzola JM, Johnson S, Rahimov F, Meng H, Lawlor MW, Estrella E, Kunkel LM, Gussoni E. CD82 is a marker for prospective isolation of human muscle satellite cells and is linked to muscular dystrophies. Cell Stem Cell 19: 800–807, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bär H, Strelkov SV, Sjöberg G, Aebi U, Herrmann H. The biology of desmin filaments: how do mutations affect their structure, assembly, and organisation? J Struct Biol 148: 137–152, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baroffio A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Gabbiani G, Bader CR. Heterogeneity in the progeny of single human muscle satellite cells. Differentiation 59: 259–268, 1995. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1995.5940259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaton LJ, Tarnopolsky MA, Phillips SM. Variability in estimating eccentric contraction-induced muscle damage and inflammation in humans. Can J Appl Physiol 27: 516–526, 2002. doi: 10.1139/h02-028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellamy LM, Joanisse S, Grubb A, Mitchell CJ, McKay BR, Phillips SM, Baker S, Parise G. The acute satellite cell response and skeletal muscle hypertrophy following resistance training. PLoS One 9: e109739, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergström J. Percutaneous needle biopsy of skeletal muscle in physiological and clinical research. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 35: 609–616, 1975. doi: 10.3109/00365517509095787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ten Broek RW, Grefte S, Von den Hoff JW. Regulatory factors and cell populations involved in skeletal muscle regeneration. J Cell Physiol 224: 7–16, 2010. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capkovic KL, Stevenson S, Johnson MC, Thelen JJ, Cornelison DD. Neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) marks adult myogenic cells committed to differentiation. Exp Cell Res 314: 1553–1565, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cermak NM, Snijders T, McKay BR, Parise G, Verdijk LB, Tarnopolsky MA, Gibala MJ, Van Loon LJ. Eccentric exercise increases satellite cell content in type II muscle fibers. Med Sci Sports Exerc 45: 230–237, 2013. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318272cf47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chargé SB, Rudnicki MA. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol Rev 84: 209–238, 2004. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarkson PM, Hubal MJ. Exercise-induced muscle damage in humans. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 81, Suppl: S52–S69, 2002. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200211001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conboy MJ, Cerletti M, Wagers AJ, Conboy IM. Immuno-analysis and FACS sorting of adult muscle fiber-associated stem/precursor cells. Methods Mol Biol 621: 165–173, 2010. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-063-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper RN, Tajbakhsh S, Mouly V, Cossu G, Buckingham M, Butler-Browne GS. In vivo satellite cell activation via Myf5 and MyoD in regenerating mouse skeletal muscle. J Cell Sci 112: 2895–2901, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornelison DD, Olwin BB, Rudnicki MA, Wold BJ. MyoD(−/−) satellite cells in single-fiber culture are differentiation defective and MRF4 deficient. Dev Biol 224: 122–137, 2000. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crameri RM, Langberg H, Magnusson P, Jensen CH, Schrøder HD, Olesen JL, Suetta C, Teisner B, Kjaer M. Changes in satellite cells in human skeletal muscle after a single bout of high intensity exercise. J Physiol 558: 333–340, 2004. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.061846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dreyer HC, Blanco CE, Sattler FR, Schroeder ET, Wiswell RA. Satellite cell numbers in young and older men 24 hours after eccentric exercise. Muscle Nerve 33: 242–253, 2006. doi: 10.1002/mus.20461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evers DL, Fowler CB, Cunningham BR, Mason JT, O’Leary TJ. The effect of formaldehyde fixation on RNA: optimization of formaldehyde adduct removal. J Mol Diagn 13: 282–288, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoedt A, Christensen B, Nellemann B, Mikkelsen UR, Hansen M, Schjerling P, Farup J. Satellite cell response to erythropoietin treatment and endurance training in healthy young men. J Physiol 594: 727–743, 2016. doi: 10.1113/JP271333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hornberger TA, Carter HN, Hood DA, Figueiredo VC, Dupont-Versteegden EE, Peterson CA, McCarthy JJ, Camera DM, Hawley JA, Chaillou T, Cheng AJ, Nader GA, Wüst RC, Houtkooper RH. Commentaries on Viewpoint: The rigorous study of exercise adaptations: Why mRNA might not be enough. J Appl Physiol (1985) 121: 597–600, 2016. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00509.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Illa I, Leon-Monzon M, Dalakas MC. Regenerating and denervated human muscle fibers and satellite cells express neural cell adhesion molecule recognized by monoclonal antibodies to natural killer cells. Ann Neurol 31: 46–52, 1992. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishido M, Uda M, Kasuga N, Masuhara M. The expression patterns of Pax7 in satellite cells during overload-induced rat adult skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 195: 459–469, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2008.01905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirby TJ, Patel RM, McClintock TS, Dupont-Versteegden EE, Peterson CA, McCarthy JJ. Myonuclear transcription is responsive to mechanical load and DNA content but uncoupled from cell size during hypertrophy. Mol Biol Cell 27: 788–798, 2016. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-08-0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitzmann M, Carnac G, Vandromme M, Primig M, Lamb NJC, Fernandez A. The muscle regulatory factors MyoD and myf-5 undergo distinct cell cycle-specific expression in muscle cells. J Cell Biol 142: 1447–1459, 1998. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.6.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lepper C, Partridge TA, Fan CM. An absolute requirement for Pax7-positive satellite cells in acute injury-induced skeletal muscle regeneration. Development 138: 3639–3646, 2011. doi: 10.1242/dev.067595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindström M, Thornell LE. New multiple labelling method for improved satellite cell identification in human muscle: application to a cohort of power-lifters and sedentary men. Histochem Cell Biol 132: 141–157, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00418-009-0606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackey AL, Kjaer M, Charifi N, Henriksson J, Bojsen-Moller J, Holm L, Kadi F. Assessment of satellite cell number and activity status in human skeletal muscle biopsies. Muscle Nerve 40: 455–465, 2009. doi: 10.1002/mus.21369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masuda N, Ohnishi T, Kawamoto S, Monden M, Okubo K. Analysis of chemical modification of RNA from formalin-fixed samples and optimization of molecular biology applications for such samples. Nucleic Acids Res 27: 4436–4443, 1999. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mauro A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 9: 493–495, 1961. doi: 10.1083/jcb.9.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCarthy JJ, Mula J, Miyazaki M, Erfani R, Garrison K, Farooqui AB, Srikuea R, Lawson BA, Grimes B, Keller C, Van Zant G, Campbell KS, Esser KA, Dupont-Versteegden EE, Peterson CA. Effective fiber hypertrophy in satellite cell-depleted skeletal muscle. Development 138: 3657–3666, 2011. doi: 10.1242/dev.068858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKay BR, De Lisio M, Johnston AP, O’Reilly CE, Phillips SM, Tarnopolsky MA, Parise G. Association of interleukin-6 signalling with the muscle stem cell response following muscle-lengthening contractions in humans. PLoS One 4: e6027, 2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKay BR, O’Reilly CE, Phillips SM, Tarnopolsky MA, Parise G. Co-expression of IGF-1 family members with myogenic regulatory factors following acute damaging muscle-lengthening contractions in humans. J Physiol 586: 5549–5560, 2008. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.160176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKay BR, Toth KG, Tarnopolsky MA, Parise G. Satellite cell number and cell cycle kinetics in response to acute myotrauma in humans: immunohistochemistry versus flow cytometry. J Physiol 588: 3307–3320, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.190876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mechtersheimer G, Staudter M, Möller P. Expression of the natural killer (NK) cell-associated antigen CD56(Leu-19), which is identical to the 140-kDa isoform of N-CAM, in neural and skeletal muscle cells and tumors derived therefrom. Ann NY Acad Sci 650: 311–316, 1992. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb49143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Megeney LA, Kablar B, Garrett K, Anderson JE, Rudnicki MA. MyoD is required for myogenic stem cell function in adult skeletal muscle. Genes Dev 10: 1173–1183, 1996. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mikkelsen UR, Langberg H, Helmark IC, Skovgaard D, Andersen LL, Kjaer M, Mackey AL. Local NSAID infusion inhibits satellite cell proliferation in human skeletal muscle after eccentric exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 107: 1600–1611, 2009. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00707.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller BF, Konopka AR, Hamilton KL. The rigorous study of exercise adaptations: why mRNA might not be enough. J Appl Physiol (1985) 121: 594–596, 2016. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00137.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller BF, Konopka AR, Hamilton KL. Last Word on Viewpont: On the rigorous study of exercise adaptations: Why mRNA might not be enough? J Appl Physiol (1985) 121: 601, 2016. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00505.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nederveen JP, Joanisse S, Snijders T, Thomas ACQ, Kumbhare D, Parise G. The influence of capillarization on satellite cell pool expansion and activation following exercise-induced muscle damage in healthy young men. J Physiol 596: 1063–1078, 2018. doi: 10.1113/JP275155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nederveen JP, Snijders T, Joanisse S, Wavell CG, Mitchell CJ, Johnston LM, Baker SK, Phillips SM, Parise G. Altered muscle satellite cell activation following 16 wk of resistance training in young men. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 312: R85–R92, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00221.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pisani DF, Clement N, Loubat A, Plaisant M, Sacconi S, Kurzenne JY, Desnuelle C, Dani C, Dechesne CA. Hierarchization of myogenic and adipogenic progenitors within human skeletal muscle. Stem Cells 28: 2182–2194, 2010. doi: 10.1002/stem.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pisani DF, Dechesne CA, Sacconi S, Delplace S, Belmonte N, Cochet O, Clement N, Wdziekonski B, Villageois AP, Butori C, Bagnis C, Di Santo JP, Kurzenne JY, Desnuelle C, Dani C. Isolation of a highly myogenic CD34-negative subset of human skeletal muscle cells free of adipogenic potential. Stem Cells 28: 753–764, 2010. doi: 10.1002/stem.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Psilander N, Damsgaard R, Pilegaard H. Resistance exercise alters MRF and IGF-I mRNA content in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985) 95: 1038–1044, 2003. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00903.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rafuse VF, Polo-Parada L, Landmesser LT. Structural and functional alterations of neuromuscular junctions in NCAM-deficient mice. J Neurosci 20: 6529–6539, 2000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06529.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roberts MD, Dalbo VJ, Kerksick CM. Postexercise myogenic gene expression: are human findings lost during translation? Exerc Sport Sci Rev 39: 206–211, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodgers JT, King KY, Brett JO, Cromie MJ, Charville GW, Maguire KK, Brunson C, Mastey N, Liu L, Tsai C-R, Goodell MA, Rando TA. mTORC1 controls the adaptive transition of quiescent stem cells from G0 to G(Alert). Nature 510: 393–396, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nature13255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambasivan R, Yao R, Kissenpfennig A, Van Wittenberghe L, Paldi A, Gayraud-Morel B, Guenou H, Malissen B, Tajbakhsh S, Galy A. Pax7-expressing satellite cells are indispensable for adult skeletal muscle regeneration. Development 138: 3647–3656, 2011. doi: 10.1242/dev.067587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47a.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 3: 1101–1108, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scott IC, Tomlinson W, Walding A, Isherwood B, Dougall IG. Large-scale isolation of human skeletal muscle satellite cells from post-mortem tissue and development of quantitative assays to evaluate modulators of myogenesis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 4: 157–169, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s13539-012-0097-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snijders T, Nederveen JP, McKay BR, Joanisse S, Verdijk LB, van Loon LJC, Parise G. Satellite cells in human skeletal muscle plasticity. Front Physiol 6: 283, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trapecar M, Kelc R, Gradisnik L, Vogrin M, Rupnik MS. Myogenic progenitors and imaging single-cell flow analysis: a model to study commitment of adult muscle stem cells. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 35: 249–257, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s10974-014-9398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Verdijk LB, Koopman R, Schaart G, Meijer K, Savelberg HH, van Loon LJ. Satellite cell content is specifically reduced in type II skeletal muscle fibers in the elderly. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E151–E157, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00278.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Rivera AJ. Temporal expression of regulatory and structural muscle proteins during myogenesis of satellite cells on isolated adult rat fibers. Dev Biol 164: 588–603, 1994. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yin H, Price F, Rudnicki MA. Satellite cells and the muscle stem cell niche. Physiol Rev 93: 23–67, 2013. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]