Abstract

Hypothetical Purchase Tasks (HPTs) simulate demand for a substance as a function of escalating price. HPTs are increasingly used to examine relationships between substance-related correlates and outcomes and demand typically characterized using a common battery of indices (Intensity, Omax, Pmax, Breakpoint, Elasticity). This review examines the relative sensitivity of the HPT indices. Reports were identified using the search term “purchase task” in PubMed and Web of Science. For inclusion, reports had to be original studies in English, examine relationships between HPT indices and substance-related correlates or outcomes, and appear in a peer-reviewed journal through December 2017. Indices were compared using effect sizes (Cohen’s d) and the proportion of studies in which statistically significant relationships were observed. The search identified 1,274 reports with 114 (9%) receiving full-text review and 82 (6%) meeting inclusion criteria. 41 reports examined alcohol, 34 examined cigarettes/nicotine products, and 10 examined other substances. Overall, statistically significant relationships between HPT indices and substance-related correlates and outcomes were most often reported for Intensity (88.61%, 70/79), followed by Omax (81.16%, 56/69), Elasticity (72.15%, 57/59), Breakpoint (62.12%, 41/66), and Pmax (48.08%; 25/52). The largest effect sizes were observed for Intensity (0.75 ± 0.04, CI 0.67–0.84) and Omax (0.64±0.04, CI 0.56–0.71), followed by Elasticity (0.44±0.04, CI 0.37–0.51), Breakpoint (0.30±0.03, CI 0.25–0.36), and Pmax (0.25±0.04, CI 0.18–0.33). Patterns were largely consistent across substances. In conclusion, HPTs can be highly effective in revealing relationships between demand and substance-related correlates and outcomes, with Intensity and Omax exhibiting the greatest sensitivity.

Keywords: hypothetical purchase tasks, purchase task, alcohol purchase task, cigarette purchase task, behavioral economics, substance use, addiction, substance use disorders

INTRODUCTION

Behavioral economics is a discipline that investigates decision-making processes using principles and methods of psychology and microeconomics (Bickel, DeGrandpre, & Higgins, 1993; Hursh, Galuska, Winger, & Woods, 2005; Reed, Galuska, & Kaplan, 2013). According to behavioral economic theory, behavior exists within an economic context in which commodities (i.e., reinforcers) compete for limited consumer resources (e.g., time, money, effort; Hursh & Roma, 2016). Behavioral economic approaches have been applied to the examination of demand for addictive substances. Addiction can be conceptualized as a condition wherein substances become overvalued compared to other reinforcers in a person’s life (Bickel et al., 2014; Higgins, Heil, & Lussier, 2004). This overvaluation is linked to increased consumption, craving, withdrawal, and relapse risk (Cook et al., 2010; Higgins, 1997; Leventhal et al., 2008, 2014; Zvolensky et al., 2009).

Hypothetical purchase tasks (HPT) are commonly used as an ethical and safe method to experimentally investigate the reinforcing value of substances, particularly the overvaluation of substances associated with substance misuse and addiction (Roma et al., 2017). HPTs require individuals to make choices about hypothetical commodities across a range of hypothetical prices in order to examine various dimensions of substance-related reinforcement including addiction potential (Bickel et al., 2014; Higgins et al., 2017a,b; Jacobs & Bickel, 1999; Vuchinich & Heather, 2003). For example, a cigarette purchase task asks smokers to estimate the number of cigarettes they would purchase and smoke in a 24-hour period across a progressively increasing range of monetary prices. Demand curves generated using HPTs have been demonstrated to correspond closely to those obtained when directly measuring actual consumption under controlled laboratory conditions (Amlung et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2016).

The primary dependent measures obtained using HPTs include an overall demand curve, five indices, and more recently, two latent factors that are derived from combining the individual indices. The overall demand curve depicts consumption within the designated time period across a range of escalating prices (MacKillop et al., 2008). The five indices are: Intensity (consumption at zero or minimal price; maximum consumption); Omax (maximum amount spent for the substance across all price points; maximum expenditure); Pmax (the price point associated with maximum expenditure); Breakpoint (the price point at which consumption is suppressed to zero); and Elasticity (overall sensitivity to increases in price) (Hursh & Roma, 2016). These indices detect related but nuanced aspects of the reinforcing value of substances and provide insights about the overvaluation of substances that contributes to problematic use and addiction. The two latent factors summarizing the five indices are Amplitude and Persistence (Aston et al., 2017; Bidwell et al., 2012; MacKillop et al., 2009). Amplitude typically includes Intensity and Omax and represents maximum consumption of the given substance and maximum expenditure for the substance. Persistence typically encompasses Pmax, Breakpoint, Elasticity, and to a lesser extent, Omax, and represents the sensitivity of consumption to increasing constraint (Bidwell et al., 2012; MacKillop et al., 2009; O’Connor et al., 2016). Although these latent factors appear to have predictive utility (Aston et al., 2017; O’Connor et al., 2016, but see Gonzalez-Roz et al., 2018), they are not yet reported regularly in the literature and thus are not examined as part of this review, including in those studies that otherwise met inclusion criteria for this review (e.g., Aston et al., 2017; Kiselica & Borders, 2013; O’Connor et al., 2016; Teeters et al., 2014).

HPTs are increasingly being used in substance use research to discern individual differences in risk factors for and markers of problematic use (e.g., dependence, comorbid psychiatric symptoms) in addition to response to clinical or regulatory interventions (Roma et al., 2017). For example, HPTs have been shown to be sensitive to individual differences in demand for alcohol among college students (Murphy et al., 2009), to individual differences in demand for cigarettes among those with versus without serious mental illness (MacKillop & Tidey, 2011), and to individual differences in demand for cigarettes varying in nicotine content among the general population of smokers (Smith et al., 2017) and vulnerable populations (Higgins et al., 2017a). Furthermore, HPTs have been shown to independently predict risk factors for continued smoking during pregnancy, above and beyond conventional predictors of quit success (Higgins et al., 2017b). Finally, HPT indices have been shown to be sensitive in assessing response to regulatory policy interventions, such as reducing nicotine content or increasing excise taxes on cigarettes (Smith et al., 2017; Grace et al., 2015b).

As use of HPTs increases, there is emerging recognition of the need to systematically validate and compare the relative sensitivity of the five commonly used HPT demand indices in assessing relationships between demand for substances and substance-related correlates and outcomes. We know of two systematic reviews on this general topic, although both were restricted to the Alcohol Purchase Task (APT) (Kiselica et al., 2016; Kaplan et al., 2018). Kiselica and colleagues separately compared the average effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) obtained for each of the five APT indices in relation to four different alcohol-related outcome measures: alcohol consumption, binge/heavy drinking, alcohol problems, and Alcohol Use Disorder symptoms. Results were consistent across the four outcome measures: Intensity produced larger effects sizes than each of the other indices except Omax and only Intensity demonstrated incremental utility in predicting outcomes above conventional measures of alcohol consumption. Kaplan and colleagues (2018) documented considerable variation across studies in how the APT was constructed, administered, and analyzed, underscoring the need to eliminate this methodological heterogeneity to develop best practices in using the APT, but did not examine the relative sensitivity of the indices.

To our knowledge, there have been no systematic reviews examining the relative sensitivity of the five HPT indices beyond the APT. As use of HPTs continues to grow, knowing whether the greater sensitivity of Intensity and Omax relative to other indices reported by Kiselica and colleagues (2016) is specific to the APT or whether this sensitivity extends to HPTs assessing other substances seems especially important and is thus the overarching purpose of this review. Further, Kiselica and colleagues (2016) examined only cross-sectional studies, thus excluding data from longitudinal, observational, and experimental studies. Knowing the relative sensitivity of the HPT indices to changes in substance-related outcomes over time in longitudinal/experimental studies is important information for researchers, policy makers, and clinicians alike. In order to address these gaps in this emerging literature, we examined HPT studies on alcohol, cigarettes, and other substances including cross-sectional and longitudinal/experimental studies in this review. Greater understanding of the relative sensitivity of HPT indices to detect substance-related correlates and outcomes across substances and different types of studies is important as use of this behavioral-economic approach to studying substance use grows and increasingly informs regulatory policy (Roma et al., 2017).

METHODS

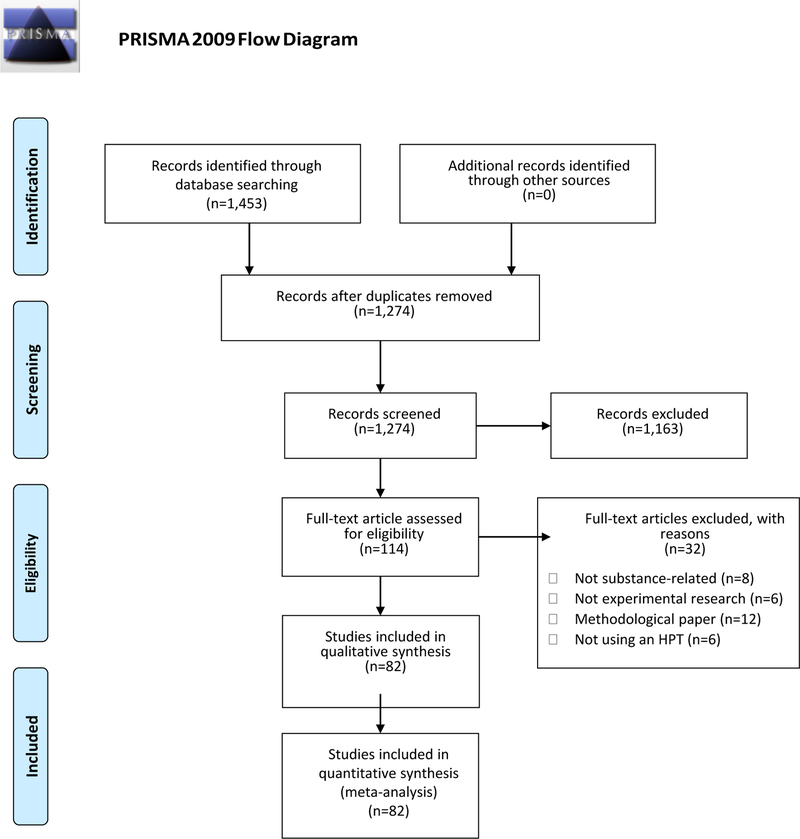

This review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009). Reports were identified using PubMed, the search engine of the U.S. National Library of Medicine, and Web of Science, a citation indexing service started by the Institute for Scientific Information. The term “purchase task” was entered into each search engine and articles were included if published online through December 31, 2017. All articles were reviewed for inclusion by three of the authors (I.Z., T.N., and A.K.), and discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion. Duplicates across databases were removed.

Criteria for inclusion were that reports had to (a) be in English; (b) appear in a peer-reviewed journal and be published online through December 31, 2017; (c) include an HPT focused on a substance; (d) examine relationships between HPT indices and their association with substance-related correlates and outcomes; and (e) be an original study reporting previously unpublished data.

Included articles were categorized by target substance (e.g., alcohol, cigarettes, other substances). Studies examining multiple substances (Hindocha et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2017; Strickland et al., 2016a, 2016b, 2017) were included in more than one substance category. Cross-sectional and longitudinal/experimental studies were included. Cross-sectional studies included those that examined correlations between demand and substance-related outcomes at one time point in the absence of any experimental manipulation. Longitudinal studies included those measuring demand (a) in observational studies using within-subject designs over time and/or (b) as part of an experimental manipulation. Given the focus of this review, distinctions were not drawn between derived and observed metrics for calculations of HPT indices, although this information is indicated in tables. This review included any index that was reported in the articles regardless of method of calculation.

Two methods were used to assess the relative sensitivity of the HPT indices. First, we compared the proportion of studies in which statistically significant relationships were reported between each of the five commonly used HPT indices (Intensity, Omax, Pmax, Breakpoint, Elasticity) and substance-related correlates and outcomes. If a study did not measure a particular HPT index or if an index was excluded from data analyses, it was not included in calculating the proportion of studies for that particular index.

Second, effect sizes were calculated for each of the HPT indices and substance-related correlates and outcomes collapsing across substances (alcohol, cigarettes, other substances) and then within each of those substance categories. We did not investigate different types of substance-related outcomes given the consistent pattern across outcomes reported by Kiselica and colleagues (2016). Cohen’s d was used as the measure of effect size due to its familiarity and ease of interpretation. Effect sizes were calculated for each study where (a) a statistically significant association (p < 0.05) was reported between one or more HPT index and substance-related correlates and outcomes and (b) enough information was included in the report to calculate an effect size. In those instances where a significant effect involving one or more HPT indices was reported, effect sizes were also calculated for all HPT indices for which sufficient information was reported to calculate an effect size. Whenever possible, effect sizes were computed based on the reported test statistic. In cases where an appropriate test statistic was not provided, effect sizes were computed based on descriptive statistics such as means and standard deviations (or standard errors) presented in tables or figures. Estimated average effect sizes and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated across studies and within study substance groups (alcohol, cigarettes/nicotine products, other substances) and study type groups (cross-sectional, longitudinal/experimental). Omnibus F Tests were conducted in order to test for statistically significant differences between mean effect sizes. The estimates for average effect sizes are based on a random effects meta-analysis model in which each study’s effect was weighted inversely proportional to its variance. A random effects model was used due to the assumption that there is significant heterogeneity of effect sizes across studies. Analyses were conducted using the software package Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA).

RESULTS

Search Results

The search identified 1,274 reports, of which 114 (9%, 114/1,274) were included for full-text review and 82 (6%, 82/1,274) met final inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Of the 1,274 reports identified, 1,163 (91%, 1,163/1,274) were excluded when review of title and abstract revealed no mention of an HPT. Of the 114 articles that underwent full-text review, 32 (28%, 32/114) were excluded for the following reasons: 6 (5%, 6/114) did not involve original research (e.g., systematic reviews, commentaries, etc.); 6 (5%, 6/114) examined purchase tasks using actual rather than hypothetical outcomes (the focus of this review is on HPTs); 8 (7%, 8/114) involved HPTs not assessing substance use (e.g., indoor tanning); and 12 (11%, 12/114) were methodological investigations (e.g., identifying criteria for non-systematic responding; testing different statistical models to derive indices).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Of the 82 articles that met final inclusion criteria, 43 (52%) reported cross-sectional studies (Amlung et al., 2013, 2015, 2017a, 2017b; Aston et al., 2015, 2017; Bertholet et al., 2015; Bidwell et al., 2012; Bruner & Johnson, 2014; Dennhardt et al., 2016; Farris et al., 2017a, 2017b; Gray & MacKillop, 2014; Gray et al., 2017; Herschl et al., 2012; Higgins et al., 2017b; Kiselica & Borders, 2013; Lemley et al., 2016; Luehring-Jones et al., 2016; MacKillop et al., 2008; MacKillop & Tidey, 2011; Morris et al., 2017; Murphy & MacKillop, 2006; Murphy et al., 2009, 2011, 2013, 2014; O’Connor et al., 2014, 2016; Pickover et al., 2016; Strickland & Stoops, 2017; Strickland et al., 2016a, 2016b, 2017; Teeters & Murphy, 2015; Teeters et al., 2014; Wahlstrom et al., 2012; Weinstock et al., 2016; Yurasek et al., 2011, 2013; MacKillop et al., 2014; Secades-Villa et al., 2018) and 39 (48%) were longitudinal/experimental studies (Amlung et al., 2012, 2014, 2015; Barnes et al., 2017; Berman & Martinetti, 2017; Bujarski et al., 2012; Bulley & Gullo, 2017; Chase et al., 2013; Collins et al., 2014; Dahne et al., 2017; Dennhardt et al., 2015; Gentile et al., 2012; Grace et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2015c; Higgins et al., 2017a; Johnson et al., 2017; MacKillop et al., 2007, 2012, 2016; Metrik et al., 2016; Murphy et al., 2015, 2016, 2017; Smith et al., 2017; Hindocha et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2017; Owens et al., 2015a, 2015b; Schlienz et al., 2014; Secades-Villa et al., 2016; Skidmore & Murphy, 2011; Smith et al., 2017; Snider et al., 2016, 2017; Tucker et al., 2016a, 2016b; Tucker et al., 2018; Vincent et al., 2017). Effect sizes for each HPT index overall, and separately for cross-sectional and longitudinal/experimental studies are included in Table 1. Among those 82 articles, 41 (50%, 41/82) articles investigated relationships between APT indices and alcohol-related correlates and outcomes (Amlung et al., 2012, 2013, 2015a, 2015b, 2016, 2017; Amlung & MacKillop, 2014; Berman & Martinetti, 2017; Bertholet et al., 2015; Bujarski et al., 2012; Bulley & Gullo, 2017; Dennhardt et al., 2015, 2016; Gentile et al., 2012; Gray & MacKillop, 2014; Herschl et al., 2012; Kiselica & Borders, 2013; Lemley et al., 2016, 2017; Luehring-Jones et al., 2016; MacKillop et al., 2009; Morris et al., 2017; Murphy et al., 2009, 2013, 2014 2015; Murphy & MacKillop, 2006; Owens et al., 2015a, 2015b; Skidmore & Murphy, 2011; Snider et al., 2016; Strickland et al., 2016; Strickland & Stoops, 2017; Teeters & Murphy, 2015; Teeters et al., 2014; Tucker et al., 2016a, 2016b; Wahlstrom et al., 2012; Weinstock et al., 2016; Yurasek et al., 2011, 2013); 34 (41%, 34/82) investigated relationships between Cigarette Purchase Task (CPT) indices and cigarette or other nicotine product-related correlates and outcomes (Barnes et al., 2017; Bidwell et al., 2012; Chase et al., 2013; Dahne et al., 2017; Farris et al., 2017a, 2017b; Grace et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2015c; Gray et al., 2017; Higgins et al., 2017a, 2017b; Hindocha et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2017; MacKillop et al., 2008, 2012, 2014, 2016; MacKillop & Tidey, 2011; Murphy et al., 2011, 2016, 2017; O’Connor et al., 2012, 2014, 2016; Peters et al., 2017; Schlienz et al., 2014; Secades-Villa et al., 2016, 2018; Smith et al., 2017; Snider et al., 2017; Strickland et al., 2016, 2017; Tucker et al., 2018); and 12 (15%, 12/82) investigated relationships between HPTs for other substances (e.g., cocaine, marijuana) and substance-related correlates and outcomes (Aston et al., 2015, 2017; Bruner & Johnson, 2014; Collins et al., 2014; Hindocha et al., 2017; Metrik et al., 2016; Peters et al., 2017; Pickover et al., 2016; Strickland et al., 2016a, 2016b; Strickland et al., 2017; Vincent et al., 2017). As noted above, significant associations in the five articles examining multiple substances were categorized by each substance examined (Hindocha et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2017; Strickland et al., 2016a, 2016b; 2017).

Table 1.

Effect Sizes for All Studies, Cross-sectional, and Longitudinal/Experimental Studies collapsed across all substances.

| Overall | Cross-sectional | Longitudinal/Experimental | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omnibus F Test Results: | F(4, 258) = 30.33 (p < 0.0001) | F(1, 159) = 28.81 (p < 0.0001) | F(4, 94) = 7.49 (p < 0.0001) | |||

| Index | Cohen’s d | 95% Confidence Intervals | Cohen’s d | 95% Confidence Intervals | Cohen’s d | 95% Confidence Intervals |

| Intensity | 0.75 | 0.67– 0.84 | 0.72 | 0.61– 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.67– 0.93 |

| Omax | 0.64 | 0.56– 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.49– 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.59– 0.84 |

| Elasticity | 0.44 | 0.37– 0.51 | 0.33 | 0.27– 0.39 | 0.58 | 0.45– 0.71 |

| Breakpoint | 0.30 | 0.25– 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.22– 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.25– 0.49 |

| Pmax | 0.25 | 0.18– 0.33 | 0.16 | 0.11– 0.21 | 0.35 | 0.17– 0.54 |

Overall Associations between HPT Indices and Substance-Related Correlates and Outcomes

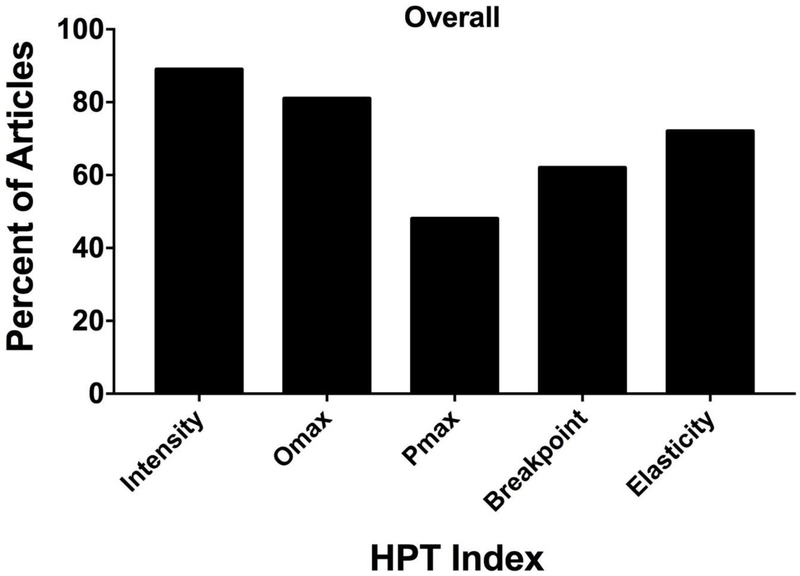

Across the 82 articles, statistically significant associations were most often reported for Intensity (88.61%, 70/79), followed by Omax (81.16%, 56/69), Elasticity (72.15%, 57/59), Breakpoint (62.12%, 41/66), and Pmax (48.08%; 25/52; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overall percentage of articles reporting significant associations between the 5 HPT indices and substance-related correlates and outcomes.

The largest effect sizes were observed for Intensity (0.75 ± 0.04, CI 0.67–0.84) and Omax (0.64±0.04, CI 0.56–0.71), followed by Elasticity (0.44±0.04, CI 0.37–0.51), Breakpoint (0.30±0.03, CI 0.25–0.36), and Pmax (0.25±0.04, CI 0.18–0.33). Omnibus F tests showed significant differences between overall mean effect sizes, and within cross-sectional and longitudinal/experimental studies (Table 1). For each set of effect sizes, there was a significant difference between means (p < 0.0001 for each). Similar results were observed when comparing average effect sizes and 95% CIs within cross-sectional and longitudinal/experimental studies. Based on the 95% confidence intervals, within the cross-sectional studies, Intensity and Omax had significantly greater mean effect sizes than each of the other indices, but their means did not differ significantly from each other; Elasticity was similar to Breakpoint but greater than Pmax; Breakpoint and Pmax did not differ significantly from each other. Within the longitudinal/experimental studies, Intensity and Omax again differed significantly from Breakpoint and Pmax but not from Elasticity or from each other; Elasticity, Breakpoint, and Pmax did not significantly differ from each other.

Associations between the Alcohol Purchase Task Indices and Alcohol-Related Correlates and Outcomes

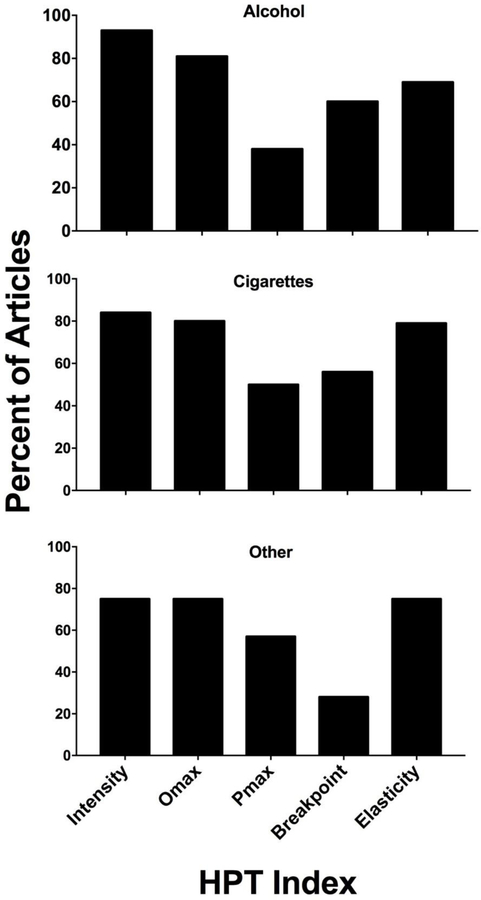

Associations between Alcohol Purchase Task (APT) indices and alcohol-related correlates and outcomes were reported in 41 articles (Amlung et al., 2012, 2013, 2015a, 2015b, 2016, 2017; Amlung & MacKillop, 2014; Berman & Martinetti, 2017; Bertholet et al., 2015; Bujarski et al., 2012; Bulley & Gullo, 2017; Dennhardt et al., 2015, 2016; Gentile et al., 2012; Gray & MacKillop, 2014; Herschl et al., 2012; Kiselica & Borders, 2013; Lemley et al., 2016, 2017; Luehring-Jones et al., 2016; MacKillop et al., 2009; Morris et al., 2017; Murphy et al., 2009, 2013, 2014 2015; Murphy & MacKillop, 2006; Owens et al., 2015a, 2015b; Skidmore & Murphy, 2011; Snider et al., 2016; Strickland et al., 2016b; Strickland & Stoops, 2017; Teeters & Murphy, 2015; Teeters et al., 2014; Tucker et al., 2016a, 2016b; Wahlstrom et al., 2012; Weinstock et al., 2016; Yurasek et al., 2011, 2013; Table 2). Broadly speaking, demographic, psychosocial, and psychiatric characteristics associated with risk for problematic alcohol use in addition to symptoms of Alcohol Use Disorder were examined in these articles. Additionally, five of these reports examined individual differences related to response to clinical interventions (Bujarski et al., 2012; Dennhardt et al., 2015; MacKillop & Murphy, 2007; Murphy et al., 2015; Tucker et al., 2016). Statistically significant associations between APT indices and alcohol-related correlates and outcomes were most frequently reported for Intensity (93%, 38/41), followed by Omax (81%, 30/37), Elasticity (69%, 25/36), Breakpoint (60%, 24/40), and Pmax (38%, 9/24; Figure 3, top panel).

Table 2.

Significant associations between PT indices and alcohol-related correlates and outcomes.

| Authors | Purpose | Substance | Significant Predictors | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amlung et al. (2012) | Examine the correspondence between choices for hypothetical and actual outcomes and the correspondence between estimated alcohol consumption and actual drinking behavior among 45 heavy-drinking adults (41 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • N/A | No significant findings relating to PT indices were reported (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Amlung et al. (2013) | Investigate the relationship between caffeine and alcoholic beverages (CAB), alcohol misuse, impulsivity traits, and demand among 316 regularly drinking college students (273 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity was associated with premeditation and positive urge impulsivity scores; Intensity and Omax were associated with sensation seeking impulsivity scores; Intensity, Omax, Breakpoint, and Elasticity were associated with negative urgency impulsivity scores and CAB use (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Amlung et al. (2015a) | Introduce area under the curve as a novel index of demand in PT among 207 college students with at least one heavy drinking episode in the past month (205 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO |

Intensity and Omax were significant predictors of weekly alcohol consumption and Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ) scores (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Amlung et al. (2015b) | Examine the effects of alcohol intoxication on alcohol demand and craving among 85 college students (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | • IntensityO • OmaxO • BreakpointO |

Increases in Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint were positively correlated with increases in craving after alcohol consumption (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, BreakpointO) | |

| Amlung et al. (2016) | Examine whether drinking-and-driving-related cognitions mediate the association between demand and drinking and driving among 147 young adult social drinkers (134 used in final analyses; 132 in Elasticity analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • ElasticityD |

Intensity was correlated with normative beliefs and perceived danger of drinking and driving; Omax and Elasticity were correlated with perceived personal limit; those who drive while intoxicated had higher Intensity and Omax and lower Elasticity (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Amlung et al. (2017) | Examine the relationship between concurrent smoking and overvaluation of alcohol among 121 non-treatment seeking drinkers (111 used in the final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity, Omax, and Elasticity were correlated with higher alcohol use disorder (AUD) severity and drinks per week; being a smoker predicted higher Omax, higher Breakpoint and lower Elasticity (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Amlung & MacKillop (2014) | Investigate the combined effects of acute stress and alcohol cues on craving, arousal, and behavioral economic measures among 90 adult heavy drinkers (84 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • BreakpointO |

Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint were higher after a stress test but decreased after neutral cue exposure; exposure to alcohol cues after a stress test increased Breakpoint; changes in responses to a choice procedure (alcohol now vs. money later) following stress vs. neutral cues were mediated by increases in Omax (Indices assessed: IntensityO, Omax O, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Berman & Martinetti (2017) | Address the effects of 2 academic variables (next-day course level and class size) on alcohol demand among 65 undergraduate students (59 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityD • OmaxD • PmaxD • ElasticityD |

Higher Intensity, Omax, Pmax, and lower Elasticity were associated with no constraint conditions (no classes); Elasticity was higher for smaller class sizes (Indices assessed: IntensityD, OmaxD, PmaxD, ElasticityD) |

| Bertholet et al. (2015) | Study the impact of drink price on hypothetical consumption and assess whether demand parameters were associated with alcohol use, alcohol use consequences, and problem severity in a general population samples among 5,520 young adult males (4,790 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

All indices were correlated with drinks per week, maximum number of drinks per occasion, monthly binge drinking, AUD criteria, and number of alcohol-related consequences (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Bujarski et al. (2012) | Assess medication effects of Naltrexone on the relative value of alcohol both before and after acute alcohol administration among 35 heavy drinking adult Asian Americans (32 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityD • OmaxD • PmaxD • BreakpointO |

Intensity and Omax were negatively correlated with Naltrexone; Naltrexone reduced Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint; Naltrexone and OPRM1 genotype interaction was significantly associated with Intensity; Higher Pmax and Breakpoint were associated with alcohol exposure (Indices assessed: IntensityD, OmaxD, PmaxD, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Bulley & Gullo (2017) | Examine the effect of episodic foresight on alcohol-related decision making among 52 undergraduates (48 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO | Intensity was associated with episodic future thinking (thinking about personally relevant future events to attenuate discounting of delayed rewards) and not with the control imagery condition (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Dennhardt et al. (2015) | Examine the impact of a brief substance use intervention on indices of substance reward value and whether baseline values and posttreatment change in these variables predict substance use outcomes among 97 heavy drinking college students (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • ElasticityD |

Intensity was correlated with alcohol and marijuana problems; Intensity and Omax were reduced after treatment, regardless of additional treatment condition; Intensity, Omax, and Elasticity were correlated with drinks per week and binge drinking; Elasticity increased after treatment, regardless of additional treatment condition (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, ElasticityD) |

| Dennhardt et al. (2016) | Examine the factors that contribute to risk for problematic drinking in a high-risk adult sample of 68 heavy drinking military veterans (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityD • OmaxD |

Intensity was associated with endorsing more social, coping-anxiety, coping-depression, and enhancement drinking motives; Omax was associated with social and enhancement drinking motives and physical problems relating to alcohol; Intensity and Omax were associated with interpersonal alcohol problems (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, ElasticityD) |

| Gentile et al. (2012) | Assess the effects of academic constraints on alcohol demand among 164 college students in one experiment and 59 students in another (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityD • ElasticityD |

Intensity was higher and Elasticity was lower in conditions with no academic constraints; Intensity was lower and Elasticity was higher for early class times and classes with exams compared to later class times (Indices assessed: IntensityD, OmaxD, PmaxD, ElasticityD) |

| Gray & MacKillop (2014) | Examine the relationship between demand and alcohol misuse, sex differences in demand, and the relationship between demand and impulsive personality traits among 787 adult smokers (720 used in final analyses, except for Elasticity, which included 684 participants) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Those with higher negative urgency had higher Intensity and Omax; Intensity, Omax, Breakpoint, and Elasticity were all correlated with Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test scores; males had higher Intensity and Omax and lower Elasticity than females (Indices assessed: IntensityO, Omax O, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Herschl et al. (2012) | Examine whether greater implicit (alcohol PT) and explicit drinking motivations would predict alcohol-related risk among 297 college binge drinkers (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO

• OmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity was correlated with age; males had higher Intensity and Omax; Intensity and Breakpoint were correlated with Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index scores; Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint correlated with Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test scores and predicted alcohol-related risk; Intensity, Omax and Elasticity were correlated with age of initiation (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Kiselica & Borders (2013) | Determine whether Intensity and Omax mediated the association between four facets of impulsivity and negative drinking outcomes among 247 college drinkers (202 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO |

Intensity was correlated with Urgency, Premeditation, and Sensation Seeking; Omax was correlated with Urgency; males reported higher Intensity and Omax; Intensity and Omax were correlated with more alcohol use and Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire scores (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO) |

| Lemley et al. (2016) | Assess relations between delay discounting, demand, and Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ) scores among 115 college drinkers (80 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityD • BreakpointO |

Intensity predicted higher scores on the YAACQ; males had higher Intensity and Breakpoint (Indices assessed: IntensityD, Omax D, PmaxD, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Lemley et al. (2017) | Examine the relationships between alcohol demand and money, alcohol, and sexual partner delay discounting among 108 college students (85 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityD | Intensity was a significant predictor of drinks per week in both typical and heaviest drinking weeks and a predictor of Sexual Risk Survey scores (Indices assessed: IntensityD, ElasticityD) |

| Luehring-Jones et al. (2016) | Extend previous research examining the effects of implicit associations and deficits in self-regulation on alcohol use among 36 college drinkers (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO, D • OmaxO • ElasticityD |

Intensity was associated with drinking consumption; Intensity was associated with implicit associations between alcohol and approach; Omax predicted drinks per day; interactions between delay discounting and implicit associations predicted Elasticity; alcohol and approach associations predicted Intensity and Elasticity (Indices assessed: IntensityO, D, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| MacKillop & Murphy (2007) | Examine if PT can predict drinking outcomes after a brief intervention among 67 college students (54 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Omax, Pmax, Breakpoint, and Elasticity predicted weekly alcohol use post-intervention; Omax and Breakpoint predicted heavy drinking at 6-month follow-up (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Morris et al. (2017) | Validate an alcohol PT and a questionnaire measure of proportionate alcohol reinforcement using an online sample among 976 MTurk users (844 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Males had higher Intensity; Intensity uniquely predicted Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) scores; Intensity, Omax, Breakpoint, and Elasticity were correlated with AUDIT scores; Omax, Breakpoint and Elasticity also predicted AUDIT scores but not uniquely (Indices assessed: IntensityO, Omax O, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Murphy et al. (2009) | Evaluate the reliability and validity of an alcohol PT among 38 college students (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO, D • OmaxO, D • ElasticityD |

Intensity, Omax, and Elasticity were correlated with weekly drinking and the Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (YAAPST) scores; Intensity predicted YAAPST scores after controlling for weekly drinking (Indices assessed: IntensityO, D, OmaxO, D, PmaxO, D, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Murphy et al. (2013) | Test whether symptoms of depression and PTSD are uniquely associated with elevated alcohol demand among 133 college students (no exclusions except only 93 used in Elasticity analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity and Elasticity were correlated with depressive symptoms; Intensity, Omax, and Elasticity were correlated with drinks per week and binge episodes; all indices were correlated with PTSD symptoms (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO,PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Murphy et al. (2014) | Examine the association between family history of alcohol misuse and individual differences in both alcohol demand and sensitivity of demand to next-day responsibilities among 207 college drinkers (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • BreakpointO |

Intensity, Omax, and change in Intensity were correlated with drinks per week; Drinkers with family history had smaller reductions in Intensity and Breakpoint if they had a next-day responsibility; Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint were correlated with Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire scores (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, BreakpointO) |

| Murphy et al. (2015) | Determine whether PT indices, measured before and after a brief alcohol intervention, predict treatment response among 133 heavy drinking college students (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO |

Intensity and Omax were positively correlated with typical weekly drinking and Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ) scores; Intensity and Omax were reduced immediately post-intervention; Intensity predicted drinks per week and YAACQ scores at 1-month follow up; reductions in Intensity and Omax post-intervention predicted drinking reductions at 1-month follow-up (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO) |

| Murphy & MacKillop (2006) | Evaluate the adequacy of the demand equation for describing alcohol consumption, the divergent validity of the indices and their associations to measures of alcohol use, and provide descriptive data on the impact of drink prices on students’ heavy episodic drinking among 267 college students (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO, D • OmaxO, D • BreakpointO |

Intensity and Omax were correlated with Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index scores; Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint were correlated with drinks per week and heavy drinking episodes per week; Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint differed between heavy vs. light drinkers (Indices assessed: IntensityO, D, OmaxO, D, PmaxO, D, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Owens et al. (2015a) | Determine whether a brief PT would be sensitive in detecting changes in demand after exposure to cues, whether cue-elicited changes in a brief PT were similar to those using a full PT, and distinguish differences between cue- elicited changes in demand and craving among 84 adult heavy drinkers (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • BreakpointO |

Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint were associated with craving and were higher after exposure to alcohol cues compared to neutral cues (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, BreakpointO) |

| Owens et al. (2015b) | Use a PT to determine if a personalized stress induction would increase demand compared to a neutral induction among 64 adult non-treatment seeking heavy drinkers (62 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity was associated with craving after neutral induction; those with higher income had greater Omax after stress induction; Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint were higher and Elasticity was lower following stress induction compared to neutral induction (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Skidmore & Murphy (2011) | Examine next-day academic responsibilities and drink price on reported alcohol consumption among 207 college students who reported heavy drinking (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Males had higher Intensity, lower Pmax, and lower Breakpoint compared to females; men had higher Intensity overall, although differences were smaller if there were next day responsibilities; Intensity and Omax were higher and Elasticity was lower for high sensation seeking drinkers; Intensity, Omax, Pmax, and Breakpoint were higher and Elasticity was lower when there were no academic responsibilities the following day (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Snider et al. (2016) | Examine the effects of engaging alcohol-dependent individuals in an Episode Future Thinking (EFT) group or Episodic Recent Thinking (ERT) group to examine effects on demand using 55 adults with alcohol dependence (37 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityD | Intensity was lower in the EFT group compared to the control ERT group (Indices assessed: IntensityD, ElasticityD) |

| Strickland et al. (2016b) | Provide support for the validity and generalizability of an exponentiated model for cocaine, alcohol, and cigarette PT among 40 cocaine using adults (37 used in final analyses) | Cocaine, Alcohol, and Cigarettes | • IntensityD • ElasticityD |

Alcohol Intensity and Elasticity were correlated with drinks per week, Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test scores, and AUD symptoms; males had higher alcohol Intensity and lower alcohol Elasticity than females (Indices assessed: IntensityD, ElasticityD) |

| Strickland & Stoops (2017) | Evaluate the stimulus selectivity of drug purchase tasks in 166 MTurk users (139 used in final analyses) | Alcohol and Cigarettes | • IntensityD • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Alcohol Intensity and Breakpoint were correlated with drinks per weeks, days drinking per week, past-month severity of binge drinking; alcohol Elasticity was negatively associated with the above measures (Indices assessed: IntensityD, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Teeters et al. (2014) | Examine whether elevated demand was associated with driving after drinking among 207 heavy drinking college students (no reports on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity and Omax were correlated with drinks per week; Intensity, Omax, and Elasticity were correlated with driving after drinking (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Teeters & Murphy (2015) | Examine the association between demand and drinking after driving; determine whether demand decreases in response to a hypothetical driving scenario; determine whether drivers who report drinking after driving show less of a reduction in demand after a driving scenario among 419 college students (no reports on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity, Omax, Breakpoint, and Elasticity predicted engaging in intoxicated driving; those endorsing intoxicated driving had less of a reduction across Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint from a standard PT to one involving a driving scenario (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Tucker et al. (2016a) | Evaluate which different behavioral economic measures were associated with drinking problem severity and outcomes of natural recovery attempts among 191 problem drinkers trying to quit drinking on their own (152 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • ElasticityD |

Higher Intensity predicted higher quantities of alcohol consumed, high scores on the Alcohol Dependence Scale, and fewer days well-functioning; higher Elasticity predicted lower quantities of alcohol consumed and more days well-functioning (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Tucker et al. (2016b) | Evaluate the predictive utility of an Alcohol-Savings Discretionary Expenditure index with multiple behavioral economic measures of impulsivity and self-control to predict outcomes of natural recovery attempts among 245 adult problem drinkers (175 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • N/A | No significant findings relating to PT indices were reported (Indices assessed: IntensityO, Omax O, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Wahlstrom et al. (2012) | Examine whether a certain genotype would moderate the relationship between alexithymia and a PT among 136 male college binge drinkers (120 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity was correlated with Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test scores; Intensity and Elasticity were correlated with alexithymia; those with the DRD2/ANKK1 TaqI A1+ allele type had higher Breakpoint; among those with an A1+ allele type, greater alexithymia predicted less Elasticity (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Weinstock et al. (2016) | Examine a gambling PT as a measure gambling using the behavioral economic model employed with the alcohol PT, using the alcohol PT for discriminant validity, for 73 adults across three groups: 28 adults with Gambling Disorder, 24 adults with AUD, and 21 healthy controls (no reports on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Those with AUD had higher Intensity, Omax, Pmax, and Breakpoint and lower Elasticity on the alcohol PT (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Yurasek et al. (2011) | Examine enhancement and coping drinking motives as mediators between demand and alcohol use and problems among 255 college drinkers (215 used in final analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity predicted enhancement and coping motives; Omax predicted enhancement motives; Intensity and Omax were correlated with binge drinking episodes and predicted alcohol use; Intensity and Omax were correlated with coping motives; Intensity, Omax, and Pmax were correlated with peak number of drinks; Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint were correlated with enhancement motives; Intensity, Omax, Breakpoint, and Elasticity were correlated with drinks per week and Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire scores (Indices assessed: IntensityO, Omax O, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Yurasek et al. (2013) | Investigate whether heavy drinking smokers would have greater demand for alcohol than heavy drinking non-smokers among 207 college drinkers (no reports on any exclusions from analyses) | Alcohol | • IntensityO • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Alcohol Intensity and Omax were correlated with nicotine dependence scores; smokers had higher Omax, Breakpoint, and Pmax; heavier smokers (7+ cigarettes per day) had higher Omax and Breakpoint; Elasticity was correlated with Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale scores; Intensity, Omax, and Elasticity were correlated with alcohol consumption; Intensity, Omax, Breakpoint, and Elasticity were correlated with Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire scores; all indices were correlated with smoking status (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

Note.

denotes when indices were observed from raw purchase task data

denotes when indices were derived from an equation.

Figure 3.

Percentage of articles reporting significant associations between the 5 HPT indices and substance-related correlates and outcomes within studies examining alcohol (top panel), cigarettes (middle panel), and other substances (bottom panel).

A similar pattern emerged when examining effect sizes. A large effect size was observed with Intensity (0.81 ± 0.05, CI 0.71–0.91). A moderate effect size was observed with Omax (0.62 ± 0.05, CI 0.53–0.71). Smaller effect sizes were observed with Elasticity (0.41 ± 0.05, CI 0.32–0.51), Breakpoint (0.34 ± 0.03, CI 0.29–0.39), and Pmax (0.15 ± 0.03, CI 0.09–0.21). Omnibus F tests showed significant differences between overall mean effect sizes, and within cross-sectional and longitudinal/experimental studies (Supplemental Table 1). For the sets of overall and cross-sectional effect sizes, there were significant differences between means (p < 0.0001 for each), but for the longitudinal effect sizes, the difference across all means was not significant (p = 0.19). Based on 95% confidence intervals for the overall mean effect sizes associated with each of the indices, Intensity and Omax had significantly greater mean effect sizes than each of the other indices but did not differ significantly from each other. Elasticity had significantly greater mean effect size than Pmax but not Breakpoint; Breakpoint produced larger effect sizes than Pmax. Similar patterns were observed across cross-sectional and longitudinal/experimental studies.

Associations between the Cigarette Purchase Task indices and Cigarette/Nicotine-Related Correlates and Outcomes

Associations between Cigarette Purchase Task (CPT) indices and cigarette/nicotine-related correlates and outcomes were reported in 34 articles (Barnes et al., 2017; Bidwell et al., 2012; Chase et al., 2013; Dahne et al., 2017; Farris et al., 2017a, 2017b; Grace et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2015c; Gray et al., 2017; Higgins et al., 2017a, 2017b; Hindocha et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2017; MacKillop et al., 2008, 2012, 2014, 2016; MacKillop & Tidey, 2011; Murphy et al., 2011, 2016, 2017; O’Connor et al., 2012, 2014, 2016; Peters et al., 2017; Schlienz et al., 2014; Secades-Villa et al., 2016, 2018; Smith et al., 2017; Snider et al., 2017; Strickland et al., 2016b, 2017; Tucker et al., 2018); (Table 3). Demographic, psychosocial, and psychiatric characteristics associated with increased risk for smoking in addition to symptoms of dependence and number of cigarettes smoked were examined in these articles. Additionally, 5 of these reports examined individual differences related to response to clinical interventions (Higgins et al., 2017b; MacKillop et al., 2016; Murphy et al., 2017; Schlienz et al., 2014; Secades-Villa et al., 2016) and 11 examined individual differences related to response to regulatory policy interventions (Grace et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2015c; Higgins, et al., 2017a; Hindocha et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2017; Murphy et al., 2016; O’Connor et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2017; Snider et al., 2017; Tucker et al., 2018). Statistically significant associations between CPT indices and cigarette/nicotine product-related correlates and outcomes were most often reported for Intensity (84%, 26/31), followed by Omax (80%, 20/25), Elasticity (79%, 26/33), Breakpoint (56%, 15/27), and Pmax (50%, 12/24; Figure 3, middle panel).

Table 3.

Significant associations between PT indices and individual differences relating to cigarettes.

| Authors | Purpose | Substance | Significant Predictors | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barnes et al. (2017) | Examine e-cigarettes’ abuse liability compared to conventional tobacco cigarettes under flavor and message conditions amenable to regulation among 62 adult smokers (36 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes and E-cigarettes (E-cigs) | • IntensityO • ElasticityD |

Intensity was higher for cigarettes than e-cigs; Elasticity was higher for menthol e-cig flavor with no warning message and unflavored e-cig with reduced exposure message than cigarettes; Elasticity across all e-cig conditions was higher than for cigarettes (Indices assessed: IntensityO, Omax O, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Bidwell et al. (2012) | Quantify the relationships between demand, cigarette consumption, and nicotine dependence among 138 adolescent smokers (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityO • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint were negatively correlated with motivation to quit; Omax was correlated with cigarettes per day; Omax, Pmax, and Elasticity were correlated with higher modified Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire scores; Omax, Pmax, Breakpoint, and Elasticity were correlated with breath carbon monoxide and urinary cotinine levels (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Chase et al. (2013) | Reproduce significant associations of a cigarette PT with nicotine dependence and contrast this to a novel chocolate PT among 287 smokers aged 18–25 (237 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityO • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint predicted dependence scores on the Cigarette Dependence Scale-5; All indices were correlated with dependence scores on Cigarette Dependences Scale-5 (Indices assessed: IntensityO, Omax O, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD)s |

| Dahne et al. (2017) | Examine the interaction between depressive symptoms and change in negative affect as a function of induced mood as a predictor of cigarette demand among 104 college smokers between the ages of 18 and 21 (73 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityO • BreakpointO • PmaxO |

Among those with a large change in negative affect, depressive symptoms were positively associated with Pmax and Breakpoint; among those with small changes in negative affect, depressive symptoms were positively associated with Intensity (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Farris et al. (2017a) | Examine the association between psychopathology and tobacco demand in 126 non-treatment seeking adult daily smokers (111 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityO • OmaxO • ElasticityD |

Smokers with an emotional disorder and smokers with 2 or more disorders had higher Intensity; Intensity and Omax were correlated with cigarettes per day and Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence scores; Smokers with any psychopathology had higher Intensity and Omax; smokers with a substance use disorder (SUD) had higher Intensity, Omax, and lower Elasticity (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Farris et al. (2017b) | Examine differences in demand and delay discounting and their association with smoking topography among 126 adult smokers with and without past-year psychopathology (107 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityO • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity and Omax were higher for smokers with psychopathology compared to those without; Omax was associated with number of puffs; Pmax, Breakpoint, and Elasticity were associated with inter-puff interval; for those with psychopathology, Elasticity was associated with time spent smoking (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Grace et al. (2015a) | Measure the cross-price elasticity of e-cigarettes and demand for cigarettes both in the presence and absence of e-cigarettes among 226 adults who never tried e-cigs (210 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes and E-cigs | • IntensityO • OmaxO • ElasticityD |

Intensity, Omax, and Elasticity were correlated with overall e-cig demand (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Grace et al. (2015b) | Assess the temporal stability of a PT before and after a tax increase among 226 adult smokers (210 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityD • OmaxO • Elasticity D |

Intensity and Omax were positively correlated and Elasticity was negatively correlated with cigarettes per day; Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence scores; Elasticity increased after tax increase (Indices assessed: IntensityD, OmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Grace et al. (2015c) | Examine whether price elasticities for smokers can predict changes in smoking after a tax increase among 357 adult smokers (211 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityO, D • OmaxO, D • ElasticityD |

Intensity and Omax were positively and Elasticity was negatively correlated with cigarettes per day; Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, Autonomy Over Smoking Scale, and Glover-Nilsson Smoking Behavior Questionnaire scores; Intensity and Omax were positively correlated and Elasticity was negatively correlated with change in cigarettes per day after tax increase (Indices assessed: IntensityO, D, OmaxO, D, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Gray et al. (2017) | Examine the neural correlates of tobacco demand among 44 non-treatment seeking male smokers (33 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • ElasticityD | Elasticity was negatively associated with activity in the left anterior insula (Indices assessed: ElasticityD) |

| Higgins et al. (2017a) | Examine how smokers with psychiatric disorders and other vulnerabilities to tobacco addiction respond to cigarettes with reduced nicotine content among 169 smokers from 3 vulnerable populations (with affective disorders, with opioid dependence, and Socioeconomically disadvantaged women; no report of any exclusions from analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityO • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO |

Intensity was higher for those with opioid dependence than women with low socioeconomic status; nicotine dose in the reduced content cigarettes was positively associated with Intensity, Omax, Pmax, and Breakpoint (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Higgins et al. (2017b) | Examine whether PT can distinguish between women with vs. without risk factors for continued smoking during pregnancy and predict differences in quit attempts among 95 pregnant smokers (93 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityO, D • OmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity and Omax were higher for those who smoked 10+ cigarettes per day (CPD) and for those with no pre-pregnancy quit attempts, Intensity and Omax distinguished between making quit attempts for those who smoked less than 10 CPD; Elasticity was lower for those who smoked 10+ CPD; Omax and Breakpoint were independent predictors of antepartum quit attempts (Indices assessed: IntensityO, D, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Hindocha et al. (2017) | Investigate how cannabis and tobacco, each alone and combined together, affected individuals’ demand for cannabis puffs and cigarettes among 24 adult recreational cannabis and tobacco co-users (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Cigarettes and Marijuana | • OmaxO • BreakpointO |

Acute administration of active cannabis decreased Omax and Breakpoint for cigarettes compared to placebo cannabis (Indices assessed: IntensityO, Omax O, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Johnson et al. (2017) | Examine cross-price elasticity of e-cigs and nicotine gum compared to cigarettes and their ability to decrease consumption of cigarettes among 400 adult M-Turk users (326 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes, E-cigs, and Nicotine Gum | • IntensityO • PmaxD • ElasticityD |

Intensity was higher and Elasticity was lower for e-cigs than cigarettes; Intensity and Pmax were lower and Elasticity was higher for cigarettes when e-cigs were offered concurrently; cross price elasticity was higher for e-cigs than cigarettes suggesting substitutability (Indices assessed: IntensityO, PmaxD, ElasticityD) |

| MacKillop et al. (2008) | Validate a cigarette PT in 33 college smokers (31 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityO, D • OmaxO, D |

Intensity and Omax were associated with Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence scores and cigarettes per day (Indices assessed: IntensityO, D, OmaxO, D, PmaxO, D, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| MacKillop et al. (2012) | Examine whether the subjective craving from acute withdrawal and exposure to tobacco cues dynamically increases the relative value of cigarettes among 41 nicotine dependent adults (33 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Deprivation increased Pmax and Breakpoint; tobacco cues reduced Elasticity (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| MacKillop et al. (2013) | Apply a behavioral economic approach to the relationship between the price of cigarettes and the probability of attempting smoking cessation among 1124 adult smokers (1070 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • Intensity | Intensity was associated with Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence scores (Indices assessed: IntensityO, BreakpointO) |

| MacKillop et al. (2016) | Investigate whether PT predicted response to contingent monetary rewards for abstinence among 338 adults with substance use disorders (SUD; no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityO • OmaxO • ElasticityD |

Intensity, Omax, and Elasticity predicted abstinence in the noncontingent voucher group (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| MacKillop & Tidey (2011) | Compare smokers with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders (SS) and control smokers (CS) on demand and delay discounting for 49 adult smokers (35 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityO • OmaxO |

The SS group had higher Intensity than CS group; Intensity and Omax were associated with Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence scores (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Murphy et al. (2011) | Evaluate the construct validity of a cigarette PT among 138 adolescent smokers (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityO • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity was associated with motivation to change; Intensity and Omax were associated with Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence scores; Intensity, Omax, Breakpoint, and Elasticity were correlated with cigarettes per day and modified Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire (MFTQ) scores; students with higher MFTQ scores reported higher Omax and Pmax; students with MFTQ scores above 6 had higher Intensity than those with no dependence and had higher Breakpoint than those with moderate dependence (MFTQ scores between 3–5; (Indices assessed: IntensityO, Omax O, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Murphy et al. (2016) | Quantify the substitutability of food and cigarettes, examine the cross-price elasticity of food and cigarettes, and examine associations between weight-related variables and weight efficacy after quitting smoking among 86 adult smokers (no report on exclusions from any analyses) | Cigarettes | • ElasticityD | For those with higher perceived ability to quit smoking without gaining weight, the cross-commodity elasticity for food was higher when the cost of cigarettes increased (i.e., they were more likely to increase food purchasing) and the cross-commodity elasticity for cigarettes was lower when the price of food increased (less likely to increase cigarette purchasing; (Indices assessed: ElasticityD) |

| Murphy et al. (2017) | Evaluate the effects of varenicline vs. nicotine replacement therapy on demand for cigarettes among smokers with SUD and whether demand predicted abstinence at 1- and 3-month follow-up among 110 adults with SUD (no report on exclusions from any analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityO • OmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity, Omax, and Elasticity were correlated with baseline cigarettes per day; Intensity, Omax, Breakpoint, and Elasticity were correlated with baseline Fagerström scores; Initial decrease in Intensity and Breakpoint was associated with increased likelihood of abstinence on quit day and predicted longest number of days of continuous abstinence at 1-month follow-up; reduced Intensity predicted greater likelihood of abstinence at 1-month follow-up and longest number of days of continuous abstinence at 3-month follow-up (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| O’Connor et al. (2012) | Examine how current smokers might respond to a ban on menthol cigarettes using 471 adolescent and adult smokers (453 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityD • OmaxD • ElasticityD |

Intensity, Omax, and Elasticity were associated with cigarettes per day; Intensity and Omax were higher and Elasticity was lower for preferred cigarette type (menthol vs. non-menthol); Elasticity was lower for those who were likely to use black market cigarettes (Indices assessed: IntensityD, OmaxD, ElasticityD) |

| O’Connor et al. (2014) | Explore how advertising affects demand for cigarettes and potential substitutes (e.g., snus, dissolvable tobacco, and medicinal nicotine) among 1,062 adult smokers (no report on exclusions from any analyses) | Cigarettes and alternative nicotine product | • IntensityD • ElasticityD |

Intensity was positively correlated with craving; higher Intensity and lower Elasticity were associated with Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence and Questionnaire for Smoking Urges scores; Intensity was higher for cigarettes compared to snus, dissolvables and lozenges; Elasticity was higher for snus than dissolvables and lozenges; Elasticity for cigarettes was correlated with cross-price elasticity for alternative products (Indices assessed: IntensityD, ElasticityD) |

| O’Connor et al. (2016) | Examine how PT indices relate to quit intentions and quit attempts among 3,001 adult daily cigarette smokers (1,1194 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • IntensityD • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

All indices were correlated with Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence scores (Indices assessed: IntensityD, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Peters et al. (2017) | Examine demand for cigarettes and marijuana independently and concurrently among 105 adult MTurk users who use both cigarettes and marijuana (82 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes and Marijuana | • ElasticityD | Elasticity for cigarettes was lower for males, lower for those with high nicotine dependence, and lower for those who smoked their first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking (Indices assessed: ElasticityD) |

| Schlienz et al. (2014) | Test the reinforcement-reduction hypothesis for varenicline among 60 adult treatment-seeking smokers (52 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes | • N/A | No significant findings relating to PT indices were reported (Indices assessed: IntensityD, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Secades-Villa et al. (2016) | Explore PT indices as predictors of smoking abstinence among participants receiving cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) combined with contingency management (CM) versus CBT alone among 168 adult smokers (159 used in final analyses) |

Cigarettes | • IntensityO • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity was correlated with years of smoking and breath carbon monoxide levels; Intensity, Omax, Breakpoint, and Elasticity were correlated with cigarettes per day; Omax, Pmax, Breakpoint, and Elasticity were correlated with SCID7 symptoms of dependence; all indices were correlated with Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale scores; Higher Elasticity was a significant predictor for more days of abstinence for those in the CBT & CM condition (Indices assessed: IntensityO, Omax O, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Secades-Villa et al. (2018) | Compare cigarette demand among 165 smokers with low and elevated depressive symptoms (no report of exclusions for any analyses) | Cigarettes | • BreakpointO

•ElasticityD |

Cigarettes per day and years of regular smoking predicted Breakpoint; depressive symptoms predicted Breakpoint; Elasticity was negatively correlated with nicotine dependence and depressive symptoms (Indices assessed: IntensityO, Omax O, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Smith et al. (2017) | Assess the impact of a reduction in the nicotine content of cigarettes on PT for reduced content cigarettes and usual brand cigarettes among 839 adult smokers (540–773 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes and Reduced Nicotine Content Cigarettes | • IntensityO • OmaxO • PmaxO • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity was lower for usual brand at 6-weeks and 24-hour abstinence visits; Omax was lower for usual brand at 6-weeks; Elasticity was lower at 24-hour abstinence visit for lower nicotine content cigarettes; Intensity, Omax, Pmax, and Breakpoint were lower at 6-weeks and 24-hour abstinence visits for lower nicotine content cigarettes (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Snider et al. (2017) | Examine how individuals purchase cigarettes and e-cigs alone and in combination as a function of price and the frequency with which they currently use e-cigs among 385 adult M-turk smokers who smoke 10+ cigarettes per day (38–104 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes and E-cigs | • ElasticityD | Elasticity was correlated with more frequent E-cig use in the cigarette only and the concurrent PT in that E-cig users had higher Elasticity for cigarettes alone than those who never used e-cigs (Indices assessed: IntensityD, ElasticityD) |

| Strickland et al. (2016b) | Provide support for the validity and generalizability of an exponentiated model for cocaine, alcohol, and cigarette PT among 40 cocaine using adults (39 used in final analyses) | Cocaine, Alcohol, and Cigarettes | • IntensityD • ElasticityD |

Cigarette Intensity was higher for those with higher Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence scores and those with lifetime cocaine use; cigarette Intensity and Elasticity were correlated with higher Drug Abuse Screening Test scores (Indices assessed: IntensityD, ElasticityD) |

| Strickland & Stoops (2017) | Evaluate the stimulus selectivity of drug purchase tasks among 66 MTurk users (46 used in final analyses) | Alcohol and Cigarettes | • IntensityD | Cigarette Intensity was positively correlated with cigarettes per day and Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence scores (Indices assessed: IntensityD, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Tucker et al. (2017) | Evaluate demand for very low nicotine content cigarettes (VLNC) when available independently or concurrently with regular cigarettes among 40 adult smokers (36 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes and VLNC | • IntensityO, D • OmaxO, D • PmaxO, D • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity and Elasticity were correlated with higher Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) scores; Intensity, Omax, and Pmax for regular cigarettes and Intensity for VLNC cigarettes were positively correlated with FTND scores; Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint were higher for regular cigarettes; Omax and Pmax for VLNC cigarettes was positively associated with cross price elasticity (Indices assessed: IntensityO, D, OmaxO, D, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

Note.

denotes when indices were observed from raw purchase task data

denotes when indices were derived from an equation.

A similar pattern emerged when examining effect sizes. Moderate effect sizes were observed with Intensity (0.70 ± 0.07, CI 0.56–0.85), Omax (0.66 ± 0.08, CI 0.50–0.81) and Elasticity (0.52 ± 0.06, CI 0.41–0.63). Smaller effect sizes were observed with Pmax (0.31 ± 0.07, CI 0.16–0.45), and Breakpoint (0.27 ± 0.04, CI 0.18–0.36). Omnibus F tests showed significant differences between overall mean effect sizes, and within cross-sectional and longitudinal/experimental studies (Supplemental Table 2). For each set of effect sizes, there were significant differences between means (p < 0.0001, p = 0.0005, p = 0.0007, respectively). Based on the 95% confidence intervals for the overall mean effect sizes, Intensity, Omax, and Elasticity had significantly greater mean effect sizes than Breakpoint but did not differ significantly from each other. Intensity and Omax but not Elasticity also had significantly greater mean effect sizes than Pmax. Similar patterns were observed across cross-sectional and longitudinal/experimental studies.

Associations between Other Substance Purchase Task indices and Substance-Related Correlates and Outcomes

Associations between Other Substance Purchase Task (OSPT) indices and substance-related correlates and outcomes were reported in 12 articles (Aston et al., 2015, 2017; Bruner & Johnson, 2014; Collins et al., 2014; Hindocha et al., 2017; Metrik et al., 2016; Peters et al., 2017; Pickover et al., 2016; Strickland et al., 2016a, 2016b; Strickland et al., 2017; Vincent et al., 2017; Table 4). Demographic, psychosocial, and psychiatric risk factors for problematic substance use were examined in these articles. One report examined individual differences related to response to a clinical intervention (Strickland et al., 2016b) and two reports examined individual differences related to response to regulatory policy (Hindocha et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2017). Statistically significant associations between OSPT indices and substance-related correlates and outcomes were most often reported for Intensity (75%, 9/12), Omax (75%, 6/8), Elasticity (75%, 9/12), followed by Pmax (57%, 4/7), and Breakpoint (29%, 2/7) (Figure 3, bottom panel).

Table 4.

Significant associations between Purchase Task indices and substance-related correlates and outcomes.

| Authors | Purpose | Substance | Significant Predictors | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aston et al. (2015) | Examine marijuana demand using a marijuana PT among 104 non-treatment seeking frequent using adults (99 used in final analyses) | Marijuana | • IntensityO •OmaxO • ElasticityD |

Intensity was correlated with age of initiation of regular use; Intensity and Omax were correlated with frequency of marijuana use; Intensity and Elasticity were associated with more DSM2 dependence symptoms; Intensity, Omax, and Elasticity were correlated with subjective craving (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Aston et al. (2017) | Determine whether metrics of reinforcement from a marijuana PT exhibit a latent factor structure that characterized demand among 99 regular (5 days/week) cannabis smokers (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Marijuana | • IntensityO | Intensity was associated with positive expectancies of use, craving severity, greater frequency of marijuana use, and DSM-IV dependence symptoms (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Bruner & Johnson (2014) | Examine the relation between demand metrics from a Cocaine PT and self-reported cocaine use among 86 cocaine-dependent individuals (74 used in final analyses) | Cocaine | • IntensityO, D • OmaxO, D • PmaxO, D • ElasticityD |

Intensity, Omax, Pmax, and Elasticity were correlated with money spent on cocaine daily and daily cocaine use; Pmax was correlated with cocaine purchased daily (Indices assessed: IntensityO, D, OmaxO, D, PmaxO, D, ElasticityD) |

| Collins et al. (2014) | Utilize the first marijuana PT to examine the relative reinforcing efficacy of marijuana among 61 young adult cannabis users (59 used in final analyses) | Marijuana | • IntensityO • OmaxO • PmaxO • ElasticityD |

Intensity and Omax were positively associated with marijuana use; Pmax and Elasticity were negatively associated with marijuana use (Indices assessed: IntensityO, D, OmaxO, D, PmaxO, D, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Hindocha et al., (2017) | Investigate how cannabis and tobacco, each alone and combined together, affected individuals’ demand for cannabis puffs and cigarettes among 24 adult recreational cannabis and tobacco co-users (no report on any exclusions from analyses) | Cigarettes and Marijuana | • N/A | No significant findings relating to Marijuana PT indices were reported (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Metrik et al. (2016) | Examine dimensions of marijuana’s incentive salience and compare cue reactivity-induced increases in craving and demand among 93 adult frequent marijuana users (no report on exclusions from any analyses) | Marijuana | • IntensityO • OmaxO • ElasticityD |

Intensity and Omax were correlated with cue-elicited craving; Intensity and Omax increased while Elasticity decreased after exposure to marijuana cues compared to neutral cues; Intensity significantly predicted attentional bias for marijuana vs. neutral words on a Stroop task (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Peters et al. (2017) | Examine demand for cigarettes and marijuana independently and concurrently among 105 adult MTurk users who use both cigarettes and marijuana (82 used in final analyses) | Cigarettes and Marijuana | • ElasticityD | Elasticity for marijuana was lower for those with high nicotine dependence; Elasticity was lower for women compared to men; For women, Elasticity for marijuana was higher when cigarettes were available compared to when only marijuana was available (Indices assessed: IntensityD, ElasticityD) |

| Pickover et al. (2016) | Introduce nonmedical use of prescription sedative/tranquilizer, stimulant, and opiate pain reliever PT, examine the relationship between demand and SUD symptoms, and examine sex differences among 393 college students (varying n’s used in final analyses depending on substance classification and missing data: 42–258) | Prescription Drugs | • IntensityO • OmaxO, D • PmaxO, D • BreakpointO • ElasticityD |

Intensity, Omax, Pmax, and Breakpoint were correlated with sedative and pain reliever use disorder symptoms; Omax and Pmax predicted pain reliever use disorder symptoms in males; Omax, Pmax, and Breakpoint were correlated with past year and life time use of sedatives; all indices were correlated with pain reliever use and stimulant use disorder symptoms, past year & life time use for stimulants and pain relievers (Indices assessed: IntensityO, OmaxO, PmaxO, BreakpointO, ElasticityD) |

| Strickland et al. (2016a) | Examine the online extension of regulation of craving tasks; a cocaine PT was administered to assess relationship between demand and craving in an Internet sample of 47 cocaine users (44 used in final analyses) | Cocaine | • N/A | No significant findings relating to PT indices were reported (Indices assessed: IntensityD, ElasticityD) |

| Strickland et al. (2016b) | Provide support for the validity and generalizability of an exponentiated model for cocaine, alcohol, and cigarette PT among 40 cocaine using adults (37 used in final analyses) | Cocaine, Alcohol, and Cigarettes | • IntensityD • ElasticityD |

Cocaine Intensity was correlated with weekly and lifetime cocaine use; cocaine Elasticity was correlated with alcohol and cigarette Elasticity; males had lower cocaine Elasticity than females (Indices assessed: IntensityO, ElasticityD) |