Abstract

Pneumonia is responsible for more deaths in the United States than any other infectious disease. Severe pneumonia is a common cause of acute respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Despite the introduction of effective antibiotics and intensive supportive care in the 20th century, death rates from community-acquired pneumonia among patients in the intensive care unit remain as high as 35%. Beyond antimicrobial treatment, no targeted molecular therapies have yet proven effective, highlighting the need for additional research. Despite some limitations, small animal models of pneumonia and the mechanistic insights they produce are likely to continue to play an important role in generating new therapeutic targets. Here we describe the development of an innovative mouse model of pneumococcal pneumonia developed for enhanced clinical relevance. We first reviewed the literature of small animal models of bacterial pneumonia that incorporated antibiotics. We then did a series of experiments in mice in which we systematically varied the pneumococcal inoculum and the timing of antibiotics while measuring systemic and lung-specific end points, producing a range of models that mirrors the spectrum of pneumococcal lung disease in patients, from mild self-resolving infection to severe pneumonia refractory to antibiotics. A delay in antibiotic treatment resulted in ongoing inflammation and renal and hepatic dysfunction despite effective bacterial killing. The addition of fluid resuscitation to the model improved renal function but worsened the severity of lung injury based on direct measurements of pulmonary edema and lung compliance, analogous to patients with pneumonia and sepsis who develop ARDS following fluid administration.

Keywords: acute lung injury, ARDS, pneumococcus, pneumonia, sepsis

INTRODUCTION

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) affects 200,000 patients each year with high associated morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide, including in low-resource settings (45, 63). ARDS is commonly caused by bacterial pneumonia, for which the most frequent responsible pathogen is Streptococcus pneumoniae (56). Patients recognized to have pneumonia are uniformly treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics within 1–2 h of presenting for medical care (25). However, much of the work done with bacterial pathogens in animal models has not included the use of antibiotics. Notably, treatment of serious pneumococcal infections with effective antibiotics releases large quantities of bacterial cell wall products over a short time and has been shown to produce a wave of inflammation that can worsen organ injury (41, 76, 77).

As part of our research designed to model ARDS in mice and to study the effects of tobacco product exposure on acute infection-related lung injury, our goal was to develop a clinically relevant mouse model of pneumococcal pneumonia. After reviewing the substantial literature on animal models of bacterial pneumonia, we found few manuscripts that provided methodological insights into model development to meet the specific needs of investigators. Herein we present our results in developing a mouse pneumococcal model incorporating antibiotic and fluid therapy that we hope will be helpful to other investigators studying sepsis, pneumonia, and ARDS in preclinical models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult 8–10-wk-old female C57BL/6 mice were ordered from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD) and housed in pathogen-free housing. Female mice were used for consistency with prior experiments involving tobacco smoke, in which female mice were found to fight less during smoke exposure (21, 23). Furthermore, it was our goal to develop a reliable model that was robust to possible hormonal effects that have commonly biased researchers away from the use of female animals. Animals were cared for in accordance with NIH guidelines by the Laboratory Animal Resource Center of the University of California, San Francisco, and all experiments were conducted under protocols approved by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Group size was determined to ensure adequate statistical power based on our extensive experience with the models of acute lung injury (16, 21, 38).

Bacterial Infection, Antibiotic Administration, and Microbiology

S. pneumoniae serotype 19F [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 49619, Manassas, VA] was grown in brain-heart broth (Becton Dickinson 237500, Sparks, MD) and harvested at the mid-log phase [optical density (OD) 0.50 at 600 nm]. To improve reliability across experiments, all cultures were derived from aliquots of a single bacterial expansion frozen at −80°C in 30% glycerol. Once OD 0.5 was reached, the bacterial culture was spun at 4,000 revolutions/min (2,700 g) and resuspended in PBS at different dilutions. Mice were anesthetized deeply with isoflurane and inoculated intranasally with 50 μL of bacterial solution. In some experiments, ceftriaxone (150 mg/kg ip) was administered. Postmortem bacterial titers of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), blood, and spleen minced in 5 mL PBS were measured by serial dilution and plaque counting on sheep blood agar plates.

Oxygenation Measurements During the Experiments

Pulse oximetry was measured using the MouseOx+ cervical collar system (Starr Life Sciences), as we have done in prior studies (21). The mean arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) during 5 min of recording was calculated for each time point.

Lung Injury End Points

Mice underwent overdose of ketamine and xylazine, bilateral thoracotomy, and exsanguination by right ventricular puncture. The lungs were removed and homogenized in 1 mL PBS, and samples of blood, lung homogenate, and homogenate supernatant were weighed before and after desiccation. Systemic hemoglobin and hematocrit were measured with a Hemavet 950 cell counter (Drew Scientific Inc., Waterbury, CT). Another fraction of homogenate was assayed for hemoglobin concentration, and the blood volume of the lung was calculated, permitting assessment of the excess extravascular lung water (i.e., pulmonary edema in the interstitial and air spaces above the level in normal mice of the same size), and wet-to-dry ratio as in prior work (22, 73). In other mice, after exsanguination, the trachea was cannulated, and the lungs were lavaged twice with 250 μL of PBS. BAL cell count was measured with a Coulter counter, cytospin preparations of BAL fluid were made and stained with Hema 3 solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and 400 cells/mouse were analyzed at ×100 magnification and classified as neutrophils, lymphocytes, or monocytic cells. BAL protein was measured with the BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For histology, the lungs were fixed by intratracheal installation of 1 mL 4% paraformaldehyde followed by overnight fixation, dehydration, paraffin embedding, and staining of 4-μm sections with hematoxylin-eosin. In some experiments, mice under deep sedation with ketamine received the neuromuscular blocking agent pancuronium (0.1 mg/kg ip) followed by tracheal cannulation (20-gage cannula). Mice were then ventilated using the Flexivent system (Version 8.0, Scireq, Montreal, Canada), and dynamic lung compliance was measured three times per animal and averaged.

Measurement of Protein Biomarkers of Inflammation and Lung Injury

Cytokines were measured using a Magpix (Luminex) with a 20-plex kit (Mouse Magnetic 20-Plex, Thermo Fisher Scientific). For the analysis, values that were undetectable were treated as having a value of zero. Log transformation was used for airspace cytokines given the large variability within groups. Values below the level of detection were treated as zero post-log transformation rather than −1.

Statistical Analyses

Comparisons between two groups were done with unpaired t test or Mann–Whitney U test (when data were not normally distributed). Comparisons of more than two groups were made with ANOVA (followed by Tukey’s or Dunnett’s multiple comparisons tests) or Kruskal–Wallis (followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test). In cases of missing data, a mixed-effects model was used. Survival analysis was done with log rank test with test for trend where appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis and graph production were done with Prism (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Strain Selection

We selected the ATCC 49619 strain of pneumococcus because it is invasive and allowed us to study the spectrum of disease from overwhelming sepsis/bacteremia to localized self-resolving pneumonia. When harvested at the mid-log phase growth and stored in 30% glycerol, 200 μL of frozen pneumococcus stock inoculated into 25 mL of broth yields an optical density (OD) of 0.5 in 4 h ± 30 min. Harvesting at a precise OD is the best method to ensure a reliable inoculum, and even 15 min too early or too late can lead to substantial variability in severity. Notably, the pneumococcus undergoes autolysis when it passes a certain density threshold, so cultures left longer than 6–8 h can be expected to have decreasing live bacteria despite a high OD.

Methods for Inoculation

Options for inoculating bacteria into the lungs of mice include direct intratracheal instillation, intranasal inoculation, and, less commonly, nebulization (27). Having used both intratracheal and intranasal techniques for a variety of infectious pathogens (21–23, 73) we elected to pursue the latter because in our experience, intranasal inoculation is faster, easier to learn, requires less anesthesia (isoflurane rather than ketamine/xylazine), and results in a more reliable lung injury. Key principles in optimizing the intranasal method include achieving a deep plane of anesthesia, in which the respiratory rate drops with a corresponding increase in tidal volume, and alternating the mouse’s position during these deep inspiratory efforts (as isoflurane wears off) so that the left and right mainstem bronchi take turns pointing toward the floor, helping to balance the distribution of the aspirated bacterial load throughout multiple lung lobes. Using volumes up to 50 μL (and preoxygenating during isoflurane induction), the procedure itself is well tolerated, with less than 1/500 mice experiencing prolonged apnea and death.

Systemic and Pulmonary Findings

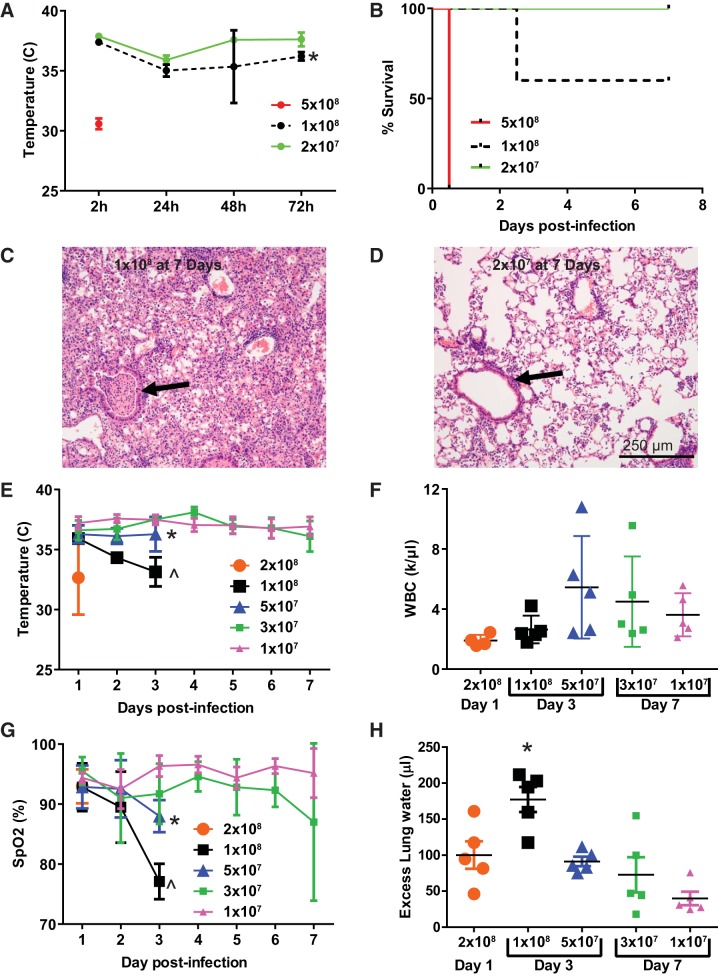

As shown in Fig. 1, immunocompetent mice inoculated with pneumococcus experienced dose-dependent hypothermia (Fig. 1A) and decreased survival (Fig. 1B). Within 4 h of being inoculated with 5 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU), mice became moribund, and lungs at necropsy were found to be grossly hemorrhagic (data not shown). Mice inoculated with 1 × 108 CFU had ~60% survival out to 7 days, whereas 2 × 107 CFU resulted in 100% survival. Histological analysis of mice infected with 1 × 108 CFU at 7 days postinfection (Fig. 1C) revealed large areas of lung consolidation associated with bronchial obstruction by inflammatory exudate (arrow), alveolar septal edema, and pleomorphic alveolar, interstitial, and perivascular cellular inflammation. In contrast, 2 × 107 CFU by 7 days produced patchy areas of mild inflammation, minimal alveolar septal edema, and no areas of frank consolidation (Fig. 1D). Thus, as in clinical medicine, pneumococcal airspace disease in mice results in a range of outcomes from overwhelming sepsis and death to self-resolving pneumonia.

Fig. 1.

Streptococcus pneumoniae dose response. A: mice inoculated intranasally with between 2 × 107 and 5 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU) of S. pneumoniae developed hypothermia. Data are mean ± SD; n = 5 per dosing group. *P = 0.0025 compared with 2 × 107 by repeated measures ANOVA. B: S. pneumoniae caused between 0% and 100% mortality across this inoculation range; P = 0.0004 for log rank test for trend. C: histology (hematoxylin-eosin) at 7 days in survivors of 1 × 108 CFU reveals severe lobar pneumonia with airway occlusion by inflammatory exudate (arrow). D: at lower doses, airways were consistently patent (arrow), and a more modest inflammatory infiltrate was observed. E: S. pneumoniae causes hypothermia at doses greater than 3 × 107 CFU. *P = 0.0007, ^P < 0.0001 compared with 1 × 107 over the first 3 days postinfection by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. F: leukopenia was most pronounced at early time points and doses greater than 5 × 107 CFU. P = 0.16 for ANOVA. G: arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) tended to decline in a dose-dependent manner for the first 72 h postinfection. *P = 0.04, ^P < 0.006 compared with 1 × 107 over the first 3 days postinfection by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. H: pulmonary edema as measured by excess extravascular lung water (in the interstitial and alveolar spaces) mirrored the changes in oxygenation. Overall ANOVA P = 0.0002; *P = 0.03 compared with 2 × 108, P = 0.01 compared with 5 × 107, P = 0.002 compared with 3 × 107, P < 0.0001 compared with 1 × 107 by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. WBC, white blood cell.

To better characterize this spectrum, we repeated a pneumococcal dose-response experiment with different euthanization time points depending on the dose to avoid excessive mortality in any group: the highest dose at 24 h, midrange doses at 3 days, and the lowest doses at 7 days. As expected, higher doses were associated with more severe hypothermia and peripheral leukopenia (Fig. 1, E and F), whereas low doses caused no discernible hypothermia or leukopenia. Notably, the most severe lung injury (as assessed by arterial hypoxemia, Fig. 1G, and excess lung water, Fig. 1H) occurred with midrange doses. Doses exceeding 1 × 108 CFU tended to result in higher mortality before severe lung injury could develop, likely in part because of low intravascular filling pressures associated with shock.

Pneumococcal Pneumonia with Antibiotics

There are two main reasons to use antibiotic therapy while studying bacterial infections in animals: 1) to reduce variance associated with overwhelming infection and 2) to better model human disease for patients under medical care.

Prior research.

A PubMed search for animal models of bacterial pneumonia in which antibiotics were administered revealed ~500 publications, the most relevant of which are summarized in Table 1. As can be readily appreciated from the table, the pathogens, host species, and antibiotic regimens that have been employed over the last 70 years have been diverse. For pneumococcal pneumonia models in mice employing ceftriaxone (a cephalosporin commonly used in human pneumococcal disease), there was a range of doses from 5 mg/kg to 200 mg/kg at dosing intervals of ~12 h (47, 66). Because our pneumococcal strain had intermediate susceptibility to penicillin (32), we elected to use a dose of 150 mg/kg ceftriaxone dosed intraperitoneally every 12 h. The next issue to address was the timing of antibiotic therapy. As is shown in Table 1, there is high variability for the timing of antibiotic administration relative to pathogen inoculation. Remarkably, one of the most thorough studies on the effect of delaying the initiation of antibiotics was published in 1947, in which white rats infected with Klebsiella pneumoniae had an initial dose of sulfa antibiotics at 6, 9, 12, or 18 h, with 94% survival at 6 h falling to 0% at 18 h (65).

Table 1.

Summary of animal models of pneumonia employing antibiotics

| Reference No. | Year | Pathogen (Strain, If Specified) | Host Species | Abx Type/Route & Dose | Abx Time Postinoculation | Purpose of Abx | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (65) | 1947 | K. pneumonia | White rats | Sulfadiazine enteral | 6, 9, 12, or 18 h | Effect on survival and pathogen clearance | 94% Survival at 6 h, 60% at 12, 0% at 18; active phagocytosis in situ leading to clearance |

| (2) | 1977 | S. pneumoniae (ATCC 6303) | Sprague-Dawley rats | Tetracycline 50 mg/kg ip | −1, 4, 12, or 24 h | Effect on pathogen clearance | Late (24 h) administration of this bacteriostatic antibiotic did not favorably impact bacterial clearance; possible importance of accumulation of pneumococcal polysaccharide |

| (55) | 1993 | P. aeruginosa (G348) | Neutropenic mice | Sparfloxacin enteral | At 12 h and then q12 h | Therapeutic synergy | Suboptimal dosing of Abx + antiflagellar Ab had best outcome |

| (47) | 1994 | S. pneumoniae (Penicillin-sensitive and resistant strains) | Neutropenic Swiss mice | Ceftriaxone 5, 10, 25, 50 mg/kg sc | At 3 h and then q12 h | Abx efficacy | For penicillin-resistant strains, 50 mg/kg with 75% survival; Abx t1/2 1.4 h |

| (66) | 1996 | S. pneumoniae (serotypes 23F and 14, with and without cephalosporin resistance) | Neutropenic Swiss mice | Ceftriaxone 100–200 mg/kg ip | At 3 h and then q12 h | Abx efficacy | >80% survival with 200 mg/kg even with cephalosporin-resistant strain; prevention of bacteremia with a single dose at either 100 or 200 mg/kg when given 3 h after inoculation; Abx t1/2 1.7 h |

| (27) | 1996 | S. pneumoniae (NNP-4) nebulized | C57BL/6 mice | Ampicillin 200 mg/kg sc | 1 h | Model development | This Abx regimen resulted in clearance from the lung but persistent pneumococcal carriage in the nasopharynx |

| (31) | 1997 | A. baumannii (SAN-94040) | 3 strains of neutropenic mice | Imipenem? 50 mg/kg ip | At 3 h and up to 3 doses at q8 h | Model development (abx PK and efficacy) | Imipenem concentrations remained above the MIC for 2 h after the last dose |

| (13) | 1998 | S. pneumoniae (ATCC 6303) | Wistar rats | Penicillin 200,000 units im | 12, 24, or 36 h | Therapeutic synergy | 0% mortality with penicillin beginning at 12 h, 60% with first dose at 24 h, 90% for 36 h; combination of partial liquid ventilation (perfluorocarbon) and Abx with best outcomes |

| (80) | 2000 | S. pneumoniae (strain not specified) | CD-1 mice | Ceftriaxone 20 mg/kg ip | 18 h | Therapeutic synergy | Improved survival and lung vascular permeability with combination of Abx and IL-10; IL-10 without Abx accelerated bacterial dissemination to the bloodstream; model studied out to 8 days |

| (12) | 2001 | S. pneumoniae (Pn4241) | BALB/c mice | Ampicillin 0.2 mg/kg sc (subcurative dose) | 3 h | Therapeutic synergy | Mice treated with IVIG and Abx with best microbiologic outcomes |

| (35) | 2003 | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) E. coli (ATCC 25922) | Wistar rats | Cefotiam 100 mg/kg (route not specified) | At 4 h then twice a day × 4 days | Simulation of clinical trial conditions (all received Abx) | Improved survival and reduced bacterial burden in lung with anti-TNF Ab in setting of Abx administration; greater effect with E. coli than with S. aureus; model studied out to 96 h |

| (62) | 2003 | S. pneumoniae (ATCC 6303) | BALB/c mice | Ceftriaxone 20 mg/kg ip | At 24 h | Therapeutic synergy | Ceftriaxone alone with better outcomes (survival and lung bacterial load) than ceftriaxone + anti-TNF Ab; model studied out to 2 wk |

| (5) | 2004 | S. pneumoniae (ATCC 6303) | Swiss Webster mice | Moxifloxacin or levofloxacin 50 mg/kg sc | At 35 h then twice a day × 5 days | Abx efficacy | Temp < 30°C used as euthanasia criterion based on high likelihood of death within 24 h; moxifloxacin with better survival |

| (54) | 2005 | S. pneumoniae (ATCC 6303); aerosolized bacteria | Neutropenic C57BL/6 mice | Ertapenem 2–50 mg/kg ip | Multiple | Abx efficacy | Aerosolized bacterial model developed as a more indolent model hypothesized (53) to allow better studies of the treatment of pneumonia as compared with septicemia |

| (75) | 2006 | K. pneumoniae (virulent and nonvirulent strains) | BALB/c mice | Ampicillin/gentamicin 320/16 mg/kg im | At 15 h, then three times a day × 5 days | To prolong the model beyond 1 wk | MRI used to follow mice noninvasively over time with image-based inflammation index |

| (33)* | 2009 | S. pneumoniae 7 days after influenza A | BALB/c mice | Ampicillin (amp), clindamycin (clinda), or azithromycin (azith) 200 (amp), 30–120 (clinda), or 5–10 (azith) mg·kg−1·day−1 ip | Variable (after pneumonia was detected by imaging) | Clinically relevant model of postviral bacterial pneumonia | Lower survival with β-lactam antibiotic despite more effective bacterial killing; β-lactam use was associated with higher lung inflammatory cytokines (hypothesized to be due to greater release of cell wall components) |

| (3) | 2010 | K. pneumoniae (B5055) | BALB/c mice | Amoxicillin/clavulinic acid reported “20 μg/mL” ip | 24 h | Therapeutic synergy | Less lung inflammation with combination of curcumin and Abx |

| (48)* | 2010 | L. pneumophila (NUL1 strain) | A/J mice | Pazufloxacin 2.5 mg/kg ip | At 24 h, then twice a day | Therapeutic synergy | Combination of Abx and sivelestat (inhibitor of neutrophil elastase) with best survival, lowest day 2 BAL inflammation, and lung bacterial load; neutrophil elastase activity at day 2: 5.6 ± 3 mM untreated vs. 14.3 ± 7 with Abx alone |

| (34)* | 2011 | S. pneumoniae following Influenza A | BALB/c | Multiple | Variable (after pneumonia detected by imaging) | Abx efficacy | Replication of a 2009 study showing that cell wall disruptive drugs (ampicillin, vancomycin) had worse lung inflammation despite better bacterial killing than protein synthesis inhibitors (clindamycin and azithromycin); this effect not seen in TLR2−/− (receptor for cell wall components) |

| (78) | 2011 | S. pneumoniae (ATCC 6303) | C57BL/6 mice | Ceftriaxone 20 mg/kg ip | At 8 or 24 h, then bid | Therapeutic synergy | Combination of Abx and tissue factor pathway inhibitor with lowest activation of coagulation in lung and plasma |

| (11) | 2011 | S. pneumoniae (ATCC 6303) | BALB/c mice | Moxifloxacin 10 mg/kg im | At 6 h, then 24, 48, 72 h | Therapeutic synergy | Combination of Abx and anti-RAGE Ab with best survival, lung histology, lowest lung inflammatory cytokines |

| (28) | 2011 | E. cloacae | Wistar rats (with and without neutropenia) | Cefepime/amikacin 60 mg/kg bid/25 mg/kg daily ip | At 6 h, then for 30 h total | Model development (reliability) | Most reliable model of pneumonia was produced with a combination of immunosuppression (cyclophosphamide-induced leukopenia) and Abx |

| (30) | 2013 | P. aeruginosa | Swiss mice | Multiple sc | At 2 h, then q8 h | Abx efficacy | Efficacy of ceftolozane |

| (8) | 2013 | P. aeruginosa (PA01, PDO300) | BALB/c mice | Ceftazidime 1 g/kg ip | At 2 h only, euth 4 h | Therapeutic synergy | Combination of Abx and simple sugars (to inhibit adhesion) with lowest bacterial loads and lung inflammation |

| (20)* | 2014 | S. pneumoniae following influenza A | BALB/c | Ampicillin 100 mg/kg ip q12 h × 5 days | Variable (after pneumonia detected by imaging) | Therapeutic synergy | High rate of death with ampicillin alone despite bacterial clearance; combination of Abx and glucocorticoids with improved survival, lowest BAL protein and inflammation |

| (29)* | 2014 | MRSA (ATCC 33591) | Swiss mice | Linezolid 80 mg/kg sc or vancomycin 110 mg/kg sc | At 2 h, then q12 h × 3 days | Abx efficacy | Similar efficacy of bacterial killing with linezolid and vancomycin; lower lung TNF-α, IL-1β, and myeloperoxidase with linezolid compared with vancomycin; hypothesized to be due to less cell wall components released because of different mechanism of action |

| (44)* | 2014 | S. pneumoniae (AMRI-SP1, ATCC 49619) | BALB/c mice | Levofloxacin, ceftriaxone 150 or 50 mg/kg iv, alone or in combination | At 18 h, then q6 h × 3 doses | Abx synergy | Better bacterial killing and less lung inflammation, decreased myeloperoxidase with combination of levofloxacin and ceftriaxone; ceftriaxone monotherapy with higher lung TNF-α than no Abx |

| (4) | 2014 | K. pneumoniae (B5055) | BALB/c mice | Clarithromycin enteral, 30 mg/kg | At 12 h | Therapeutic synergy | Reduced neutrophil influx with combination of curcumin and Abx |

| (49) | 2014 | S. pneumoniae (strain PN36) | C57BL/6 mice | Ampicillin (amp) or moxifloxacin (moxi) 20 mg/kg ip (amp) or 100 mg/kg ip (moxi) | At 24 h, then q12 h | Abx efficacy | Greater reduction in lung bacterial load with moxifloxacin; no difference in lung histology/inflammation |

| (81)* | 2014 | S. aureus (ATCC 25904) | C57BL/6 mice | Oxacillin 400 mg/kg ip | At 30 min, then four times a day | Therapeutic synergy | Combination of Abx and dexamethasone with higher lung bacterial loads but improved lung histology, BAL inflammation (cell count, TNF-α, KC, IL-6) |

| (6) | 2015 | Influenza A followed 7 days later by MRSA | C57BL/6 mice | Linezolid or vancomycin 80 mg/kg ip or 100 mg/kg ip, respectively |

At 6 h | Abx efficacy | Linezolid with slightly lower lung bacterial load and BAL inflammation (neutrophil count, KC, TNF-α, IL-1β) |

| (37)* | 2015 | P. aeruginosa (UNC-D) | BALB/c mice (± neutropenia) | Meropenem 1–1.7 g·kg−1·day−1 sc | At 3 h, then q8 h | Model development | Immunocompetent mice: Abx reduced bacterial load in the lungs but did not improve survival and was associated with more severe lung pathology: Neutropenic mice: Abx improved survival |

| (1) | 2016 | E. coli (O6:K2:H1, ATCC 19138) | C57BL/6 mice | Ciprofloxacin 0.2 mg/kg ip | At 1 h | Therapeutic synergy | Combination of Abx and aspirin-triggered Resolvin D1 with lowest lung bacterial load, alveolar edema; BAL endotoxin and neutrophil counts reduced by combination but not Abx alone |

| (74) | 2016 | S. pneumoniae (ATCC 6303) | BALB/c mice | Ceftriaxone 10 mg/kg ip | At 60 and 72 h | Therapeutic synergy | Combination of Abx and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition with best survival and lowest lung bacterial load, BAL neutrophils, TNF-α, CXCL1, CCL2 |

| (69) | 2016 | P. aeruginosa (PAR005) | Neutropenic ICR mice | Piperacillin (pip)/tazobactam or colistin 10 mg iv (pip) or 2,800 units iv (colistin) | Pretreatment | Abx efficacy | Colistin more effective microbiologically and with survival and lung edema |

| (23) | 2018 | S. pneumoniae (ATCC 49619) | C57BL/6 mice | Ceftriaxone 150 mg/kg ip | At 12 h then 12 h for 3 doses | Model development | Mice exposed to cigarette smoke had improved survival after pneumococcal inoculation without Abx. With Abx, smoking exposure had no survival benefit and was associated with increased lung injury |

Ab, antibody; A. baumannii, Acinetobacter baumannii; Abx, antibiotics; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; E. cloacae, Enterobacter cloacae; E. coli, Escherichia coli; euth, euthanization; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; KC, murine homolog of interleukin-8; K. pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae; L. pneumophila, Legionella pneumophila; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; PK, phamacokinetics; P. aeruginosa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; q12 h, every 12 h; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation endproducts; S. aureus, Staphylococcus aureus; S. pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae; TLR2, Toll-like receptor 2. Abbreviations for routes: ip, intraperitoneal; sc, subcutaneous; im, intramuscular.

Results consistent with an inflammatory effect of antibiotics that liberate bacterial cell wall components.

Dose- and time-dependent effects on systemic and pulmonary variables.

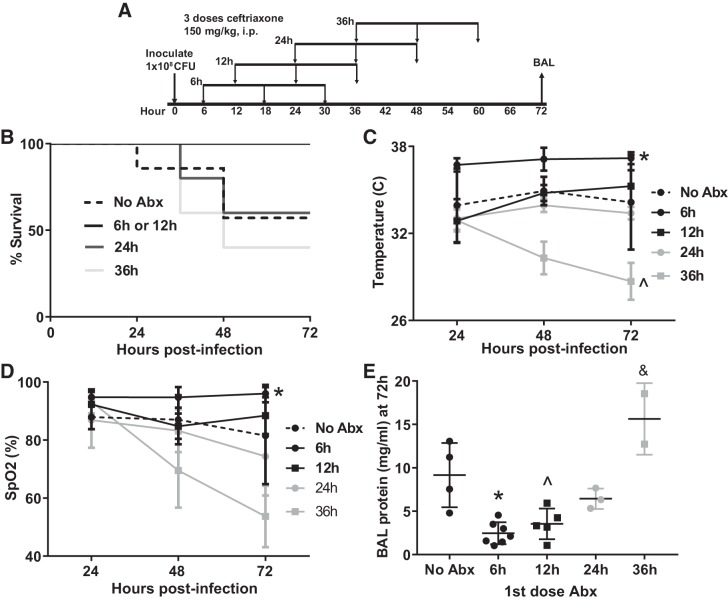

We selected the 1 × 108 CFU dose because this regimen caused the greatest degree of lung injury while mostly allowing survival through 48–72 h. We administered 3 doses of ceftriaxone beginning at 6, 12, 24, or 36 h after inoculation (Fig. 2A) followed by euthanization at 72 h for bronchoalveolar lavage. As seen in Fig. 2, B–E, mice treated with antibiotics beginning 6 h after inoculation had nearly normal body temperature and 100% survival at 72 h, modestly increased BAL protein, and arterial oxygen saturations in the high 90s. Delaying the first dose of antibiotics was associated with a trend toward lower survival, more severe hypothermia, arterial hypoxemia, and higher BAL protein. Interestingly, mice treated with antibiotics 36 h after inoculation fared worse on all counts than mice that did not receive any antibiotics at all. This result was unexpected but consistent with multiple other studies (see Table 1 footnote) that suggest that antibiotics (such as β-lactams and vancomycin) that liberate bacterial cell wall components result in more severe inflammation.

Fig. 2.

Influence of timing of first dose of antibiotics on the model. A: schematic depicting experimental procedures. Mice were inoculated with 1 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU) Streptococcus pneumoniae followed by 3 doses of ceftriaxone beginning at 6, 12, 24, or 36 h postinfection. B: there was a trend toward decreased survival as antibiotics (Abx) were delayed (n = 5–7 mice/group). P = 0.07 by log rank test. C: mice treated with antibiotics beginning at 6 h were significantly less hypothermic than untreated mice. Surprisingly, initiation of antibiotics 36 h postinfection caused more severe hypothermia than was observed without antibiotics. *P = 0.0005, ^P = 0.005 compared with no antibiotics by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. D: arterial hypoxemia was most severe in mice treated beginning 36 h postinfection. *P = 0.009 compared with no Abx by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Significant mortality in the 36-h group reduced statistical power at 72 h. SpO2, arterial oxygen saturation. E: bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) protein mirrored oxygenation with a 36-h delay in antibiotics causing higher BAL protein 72 h postinfection than in untreated mice. *P = 0.0009, ^P = 0.007, &P = 0.016 compared with no Abx by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test.

We then repeated the experiment with a 7-day end point, administering the first dose of antibiotics at 18, 24, or 30 h postinfection, to determine which interval provided the best long-term survival while also generating severe lung injury. For this experiment we continued dosing antibiotics for 5 total doses (Fig. 3A). With an 18-h delay, we achieved nearly 100% survival at 48 h and 50% survival at 7 days. Notably, delaying antibiotics further than 18 h tended to produce more severe hypothermia (Fig. 3D) and worse survival (Fig. 3B) without more severe arterial hypoxemia (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Fine-tuning the antibiotic regimen to optimize 7-day survival. A: schematic depicting experimental procedures. Mice were inoculated with 1 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU) Streptococcus pneumoniae and then received 5 doses of ceftriaxone beginning 18, 24, or 30 h later. B: mice administered the first dose of antibiotics 18 h postinfection had 50% survival at 7 days. n = 10 mice per group. P = 0.23 for log rank test for trend. C: arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) was similar across the 3 cohorts. Data are mean ± SD; P = 0.53 by ANOVA. D: body temperature trended lower with progressive delays in initiation of antibiotics. P = 0.11 by Kruskal–Wallis test.

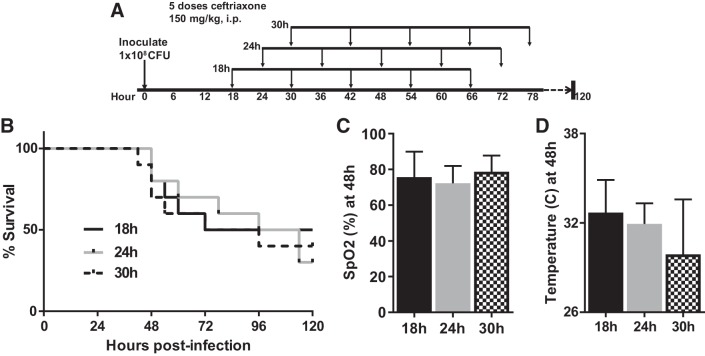

To extend the model beyond 48 h without significant mortality within the groups, we next compared 1 × 108 CFU with a 25% reduction in bacterial load (7.5 × 107 CFU) while instituting ceftriaxone beginning at 18 h (Fig. 4A). This dose reduction yielded ~80%–90% survival at 96 h (Fig. 4B). We then characterized systemic inflammation and lung injury in this model in more detail. Most mice became mildly hypothermic (34°C–35°C, Fig. 4C), and those few mice that dropped below 30°C tended to die within 12 h, consistent with a prior report that concluded that severe hypothermia in mouse models of bacterial infection might be used as a humane euthanasia end point (5). Peripheral leukopenia occurred at 48 h with substantial recovery by 96 h (Fig. 4D). Pulmonary edema, as measured by excess extravascular lung water (Fig. 4E) and wet-dry ratio (Fig. 4F), was significantly elevated at 48 h and remained elevated at 96 h, demonstrating a substantial and durable acute lung injury. Similarly, low peripheral arterial oxygen saturation persisted throughout the entire 4-day period (Fig. 4G). BAL protein declined significantly between 48 and 96 h postinjury but remained elevated substantially above normal. Similarly, the number of cells obtained by BAL declined between 48 and 96 h postinfection (Fig. 4I), and there was a trend toward increased lymphocytic inflammation (Fig. 4J).

Fig. 4.

Reducing the bacterial inoculum to improve 96-h survival while maintaining a moderately severe lung injury. A: schematic depicting experimental procedures. Mice were inoculated with either 1 × 108 or 7.5 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) Streptococcus pneumoniae and then treated with 5 doses of ceftriaxone beginning 18 h postinfection. B: survival was ~80% at 96 h in the lower-dose group (*by log rank, n = 29–40 per group). C: mice were hypothermic between 24 and 96 h postinfection. *P < 0.0001, ^P = 0.0001, &P = 0.01 by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. D: peripheral leukopenia resolves between 48 and 96 h postinfection. *P < 0.0001 by unpaired t test. E: excess lung water (ELW), a measure of edema in the interstitial and alveolar spaces, remained elevated above baseline at 48 and 96 h postinfection. *P = 0.0024, ^P = 0.0099 by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. F: wet-dry ratio was similarly increased at 48 and 96 h postinfection. *P < 0.0001 by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. G: mean arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) remained in the high 80s during the entire 96 h postinfection, though the standard deviation was high. P = 0.33 by Kruskal–Wallis. H: bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) protein peaked at 48 h postinfection and remained significantly above baseline at 96 h. *P < 0.0001 compared with no infection (No Infxn) and 96 h, ^P = 0.0194 compared with No Infxn by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. I: BAL cellularity declined significantly between 48 and 96 h postinfection; *P = 0.0303 by Mann–Whitney. J: composition of BAL cellularity was mostly neutrophils and monocyte/macrophages at both time points, though there was a trend for an increase in lymphocytes between 48 and 96 h postinfection, from 0.5% to 3.7%, P = 0.12 by Mann–Whitney. WBC, white blood cell.

Lung pathology.

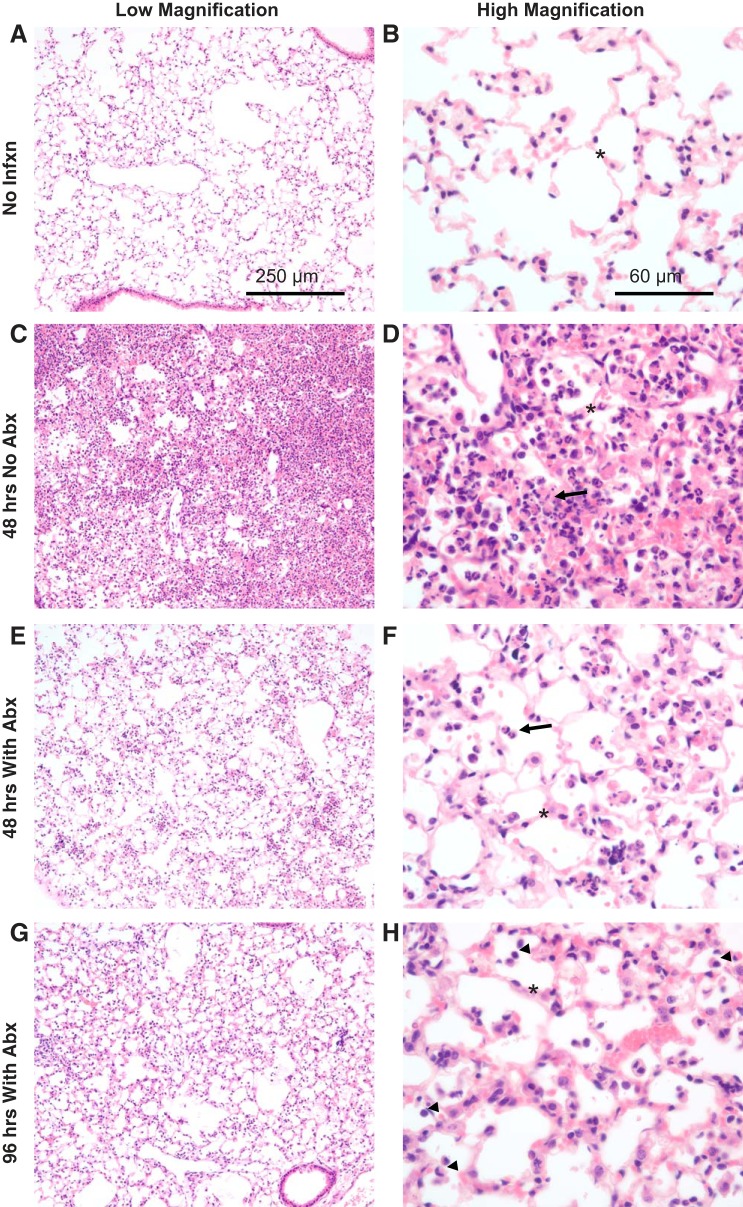

Histologically, at 48 h postinfection without antibiotics, a dense inflammatory infiltrate was observed (Fig. 5C), with higher-power images revealing alveolar wall edema and airspace clusters of neutrophils, monocytic cells, and debris (Fig. 5D). When antibiotics were initiated at 18 h, inflammation was reduced but still substantial, with alveolar wall edema and scattered neutrophils and monocytes (Fig. 5, E and F). By 96 h after infection, mice treated with antibiotics had less pronounced neutrophilic airspace inflammation, with mostly monocytic cells and increasing numbers of lymphocytes (Fig. 5H).

Fig. 5.

Histological evidence of lung injury. A–H: representative photomicrographs from the lungs of mice inoculated with 7.5 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) Streptococcus pneumoniae followed by ceftriaxone beginning 18 h later. Alveolar septal thickness (asterisks) is greatest at 48 h without antibiotics (Abx), but it remains abnormal at 48 and 96 h in antibiotic-treated mice. Inflammation is primarily neutrophilic at 48 h with or without antibiotics (arrows); by 96 h postinfection, increasing numbers of monocytic and lymphocytic cells are identified (arrowheads). No Infxn, no infection.

Proinflammatory biological responses.

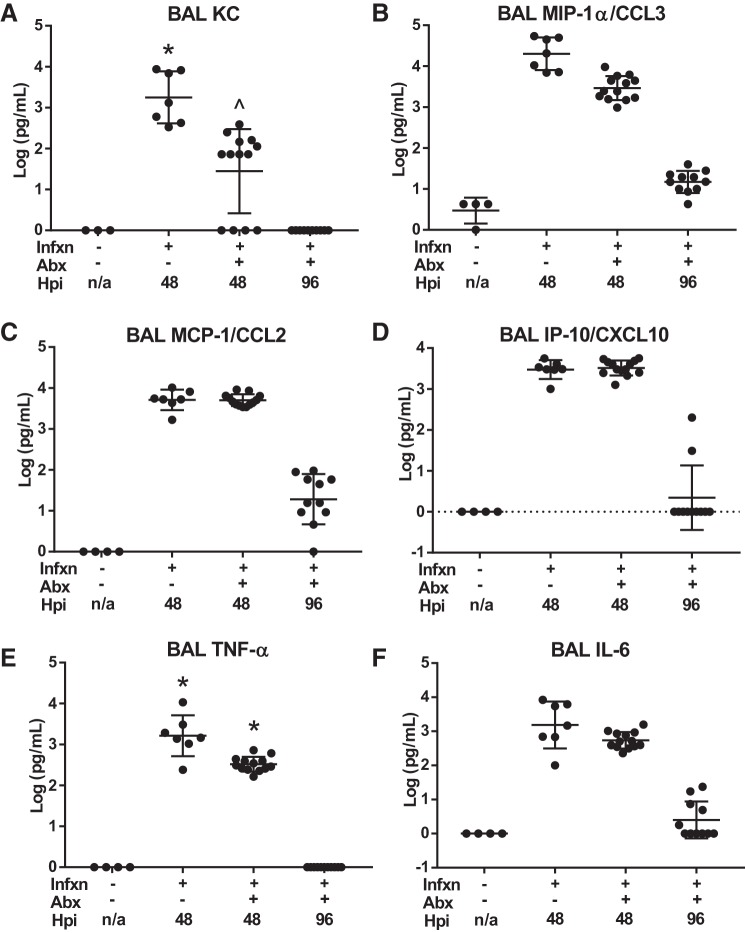

BAL cytokine and chemokine expression during these time points paralleled the histological findings. Airspace neutrophil chemokines murine homolog of interleukin-8 (KC) and macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) were reduced by an order of magnitude with antibiotic treatment by 48 h postinfection, and then decline further to near-normal levels by 96 h (Fig. 6, A and B). In contrast, the monocyte chemokines MCP-1 and interferon-γ-induced protein 10 (IP-10) were not affected at 48 h by antibiotics but declined by nearly 3 orders of magnitude between 48 and 96 h (Fig. 6, C and D). The inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 both tended to be reduced by antibiotic therapy at 48 h, and both declined to near-normal levels by 96 h (Fig. 6, E and F). Taken together, the data from the antibiotic-treated pneumonia model are consistent with persistent high-protein pulmonary edema during a period of rapidly resolving acute airspace inflammation.

Fig. 6.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cytokine expression. A: level of KC (murine homologue of IL-8, a potent neutrophil chemokine) in BAL at 48 h was significantly reduced with antibiotic (Abx) treatment but was still elevated above noninfected controls. By 96 h, BAL KC had returned to baseline in the antibiotic-treated model. *P = 0.0044 compared with −Infxn, −Abx; ^P = 0.03 compared with +Infxn −Abx by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. B: BAL MIP-1α/CCL3 was also higher in untreated infected mice at 48 h and declined substantially by 96 h but remained elevated relative to uninfected mice. P < 0.004 for all comparisons by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. C: monocyte chemokine MCP-1/CCL2 was markedly elevated in BAL 48 h postinfection but did not differ with respect to antibiotics (P < 0.0001 for both injured groups compared with uninfected mice by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). By 96 h, levels declined by 2 orders of magnitude but remained slightly elevated above baseline (P < 0.0001). D: similarly, the monocyte chemokine IP-10/CXCL10 was elevated at 48 h regardless of antibiotics (P < 0.0001 for both injured groups compared with uninfected mice, by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test), declining rapidly by 96 h. E: BAL TNF-α was significantly higher without antibiotic treatment at 48 h but rapidly declined to baseline by 96 h. *P < 0.0001 compared with all other groups by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. F: in contrast, BAL IL-6 was not significantly different at 48 h with respect to antibiotic therapy (P < 0.0001 for both infected groups at 48 h relative to uninfected groups by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Abx, antibiotics; Infxn, infection.

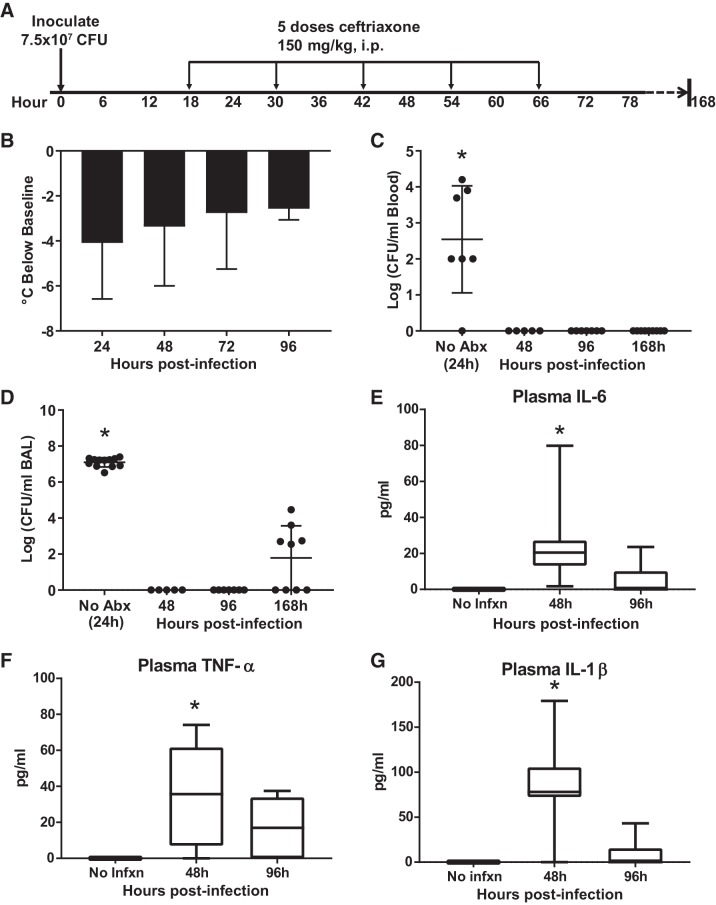

Despite the downward trend in inflammatory BAL cytokines during the first 96 h postinfection, the persistent mild hypothermia (Fig. 4B) raised the question of whether the antibiotic regimen was effective in sterilizing the airspaces and blood. We repeated the experiment with antibiotics administered beginning at 18 h and sacrificing mice at 48, 96, and 7 days (168 h) as shown in Fig. 7A. Mice were again found to be hypothermic as shown by departure from baseline temperature (Fig. 7B). Mice not treated with antibiotics had high levels of blood and airspace bacteria at 24 h postinfection, while antibiotic-treated mice had no detectable pneumococci at 48 and 96 h in blood or BAL, the latter time point notably 30 h after the last dose of ceftriaxone (Fig. 7, C and D). By 7 days postinfection (and over 4 days after the last dose of antibiotics), approximately half of the mice had detectable bacteria in BAL, though the hemolytic zone around colonies grown on blood agar plates was not present, suggesting the presence of bacteria other than the pneumococcus (data not shown). Thus, the antibiotic regimen appears to be highly effective. Systemic cytokines previously linked to endotoxin-induced hypothermia in mice were measured in plasma (7). Plasma IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β were elevated compared with baseline at 48 h postinfection, declining to near-normal levels by 96 h.

Fig. 7.

Persistent hypothermia and systemic inflammation despite bacterial clearance. A: schematic depicting experimental procedures. Mice were inoculated with 7.5 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) Streptococcus pneumoniae and then treated with 5 doses of ceftriaxone beginning 18 h postinfection. Mice were euthanized at 96 or 168 h (4 or 7 days) postinfection. B: persistent hypothermia depicted as mean departure from preinfection temperature (± SD), n = 8–24 mice per time point. P = 0.24 by ANOVA. C: bacteremia resolved within 48 h in antibiotic-treated mice. Blood cultures remained negative 7 days postinfection, more than 4 days after the completion of antibiotics. *P = 0.0015 compared with 48 h, P = 0.0004 compared with 96 h, P = 0.0002 compared with 168 h, by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. D: airspace pneumococci were cleared by 48 h postinfection and remained sterile at 96 h. About half of the mice had low levels of detectable bacteria 7 days postinfection, though these did not appear to be pneumococci based on the absence of hemolysis. *P = 0.003 compared with 48 h, P < 0.0001 compared with 96 h, P = 0.003 compared with 168 h, by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. E: plasma IL-6 was significantly elevated 48 h postinfection (*P = 0.04 compared with no infection, P = 0.04 compared with 96 h, by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). F: plasma TNF-α was significantly increased 48 h postinfection (*P = 0.025 compared with no infection, by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). G: plasma IL-1β was elevated at 48 h (*P = 0.001 compared with no infection, P = 0.0003 compared with 96 h, by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Abx, antibiotics; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; Infxn, infection.

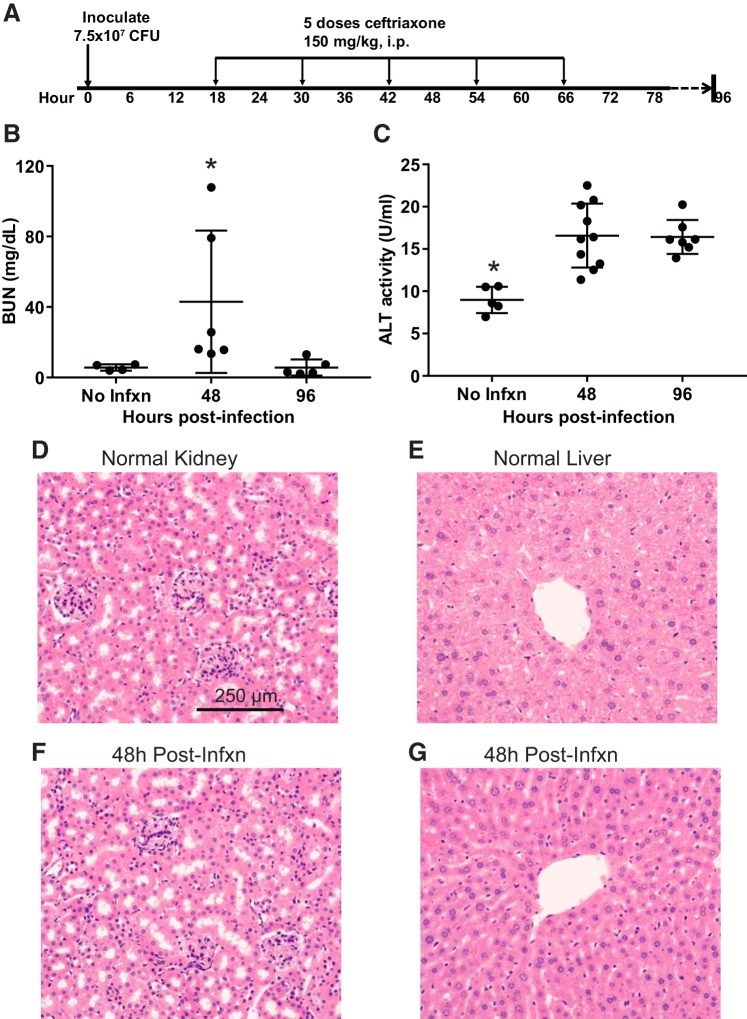

Clinical relevance for renal and liver dysfunction.

Patients suffering from severe pneumonia commonly have evidence of multiorgan injury (25), including acute kidney injury (diagnosed by increased blood urea nitrogen and creatinine) and hepatic dysfunction (diagnosed by increases in the plasma concentrations of the hepatic enzymes aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase). The long-lasting hypothermia and systemic cytokine elevations that we observed despite antibiotic therapy raised the question of whether similar abnormalities might be detectable in mice. As shown in Fig. 8, the level of blood urea nitrogen (Fig. 8B) and alanine aminotransferase both significantly increased compared with baseline at 48 h postinfection. As in patients with sepsis, minimal histological changes were found (Fig. 8, D–G) despite evidence of organ dysfunction/injury (79).

Fig. 8.

Evidence of renal and hepatic dysfunction. A: Schematic depicting experimental procedures. Mice were inoculated with 7.5 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) Streptococcus pneumoniae and then treated with 5 doses of ceftriaxone beginning 18 h postinfection followed by euthanization at 48 or 96 h. B: level of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was increased above baseline at 48 h postinfection, declining back to baseline by 96 h; *P = 0.05 compared with no infection (No Infxn), P = 0.009 compared with 96 h by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. C: alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was significantly increased above baseline at 48 and 96 h postinfection. *P = 0.0004 compared with 48 h, P = 0.001 compared with 96 h by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. D and F: hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)-stained sections of renal cortex reveals grossly normal glomeruli and tubules 48 h postinfection. E and G: H&E stained sections of liver parenchyma 48 h postinfection show no evidence of significant centrilobular necrosis or other histologic abnormalities.

Pneumococcal Pneumonia Treated with Antibiotics and Fluids

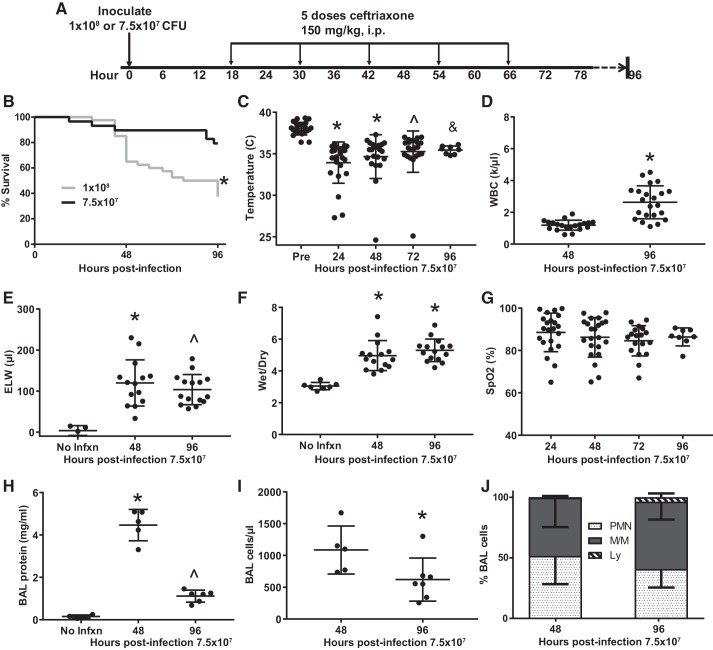

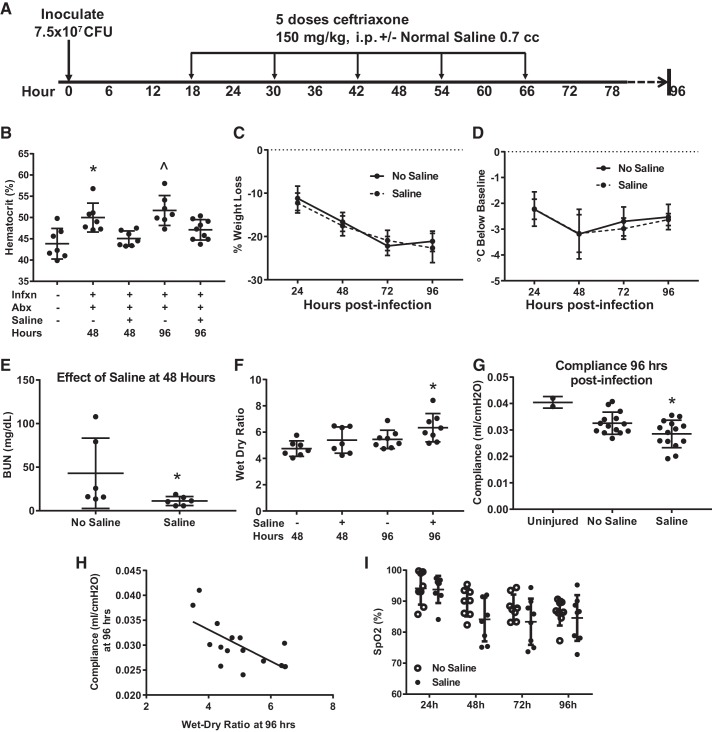

Current guidelines for managing severe infections in patients make a strong recommendation for fluid resuscitation (61). However, an alveolar-capillary barrier damaged by severe pneumonia will facilitate more translocation of intravascular fluid into the airspaces, potentially worsening the severity of gas exchange abnormalities and reducing compliance of the lung. Thus, we next incorporated crystalloid resuscitation into the model, as shown in Fig. 9A. Hemoconcentration associated with infection was largely reversed by fluid resuscitation (Fig. 9B). Interestingly, mice treated with fluids had no change in weight loss (Fig. 9C) or hypothermia (Fig. 9D). The reduction in blood urea nitrogen by fluids (Fig. 9E) suggests that the resuscitation improved renal blood flow and solute clearance. However, mice treated with fluids had more pulmonary edema as measured by wet-dry ratio at 96 h (Fig. 9F). Furthermore, dynamic lung compliance, measured using the Flexivent system after neuromuscular blockade, was significantly reduced by fluid administration (Fig. 9G), in keeping with the strong relationship between wet-dry ratio and compliance shown in Fig. 9H. Finally, arterial oxygen saturation trended lower in fluid-resuscitated mice, though this fell short of statistical significance (Fig. 9I).

Fig. 9.

Fluid resuscitation increases lung edema and worsens lung compliance. A: schematic depicting experimental procedures. Mice were inoculated with 7.5 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) Streptococcus pneumoniae and then treated with 5 doses of ceftriaxone beginning 18 h postinfection and then every 12 h × 5, with euthanization at 48 or 96 h. Half of the mice also received 700 μL ip of normal saline with each dose of antibiotics. B: saline treatment reversed hemoconcentration at 48 and 96 h, *P = 0.0046 vs. uninfected, P = 0.03 vs. saline at 48 h, by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; ^P = 0.0003 vs. uninfected, P = 0.037 vs. saline at 96 h. C and D: saline administration did not significantly affect weight loss or hypothermia. Not significant by repeated measures ANOVA. E: mice treated with saline had normalized blood urea nitrogen (BUN), consistent with correction of renal hypoperfusion; *P = 0.026 by Mann–Whitney. F: saline treatment compared with no saline increased lung edema at 96 h as measured by wet-dry ratio. *P = 0 0.05 by Mann–Whitney. G: lung dynamic compliance at 96 h was significantly reduced by saline administration, *P = 0.047 by unpaired t test. H: lung compliance and wet-dry ratio were inversely correlated, Spearman r = −0.62, P = 0.02. I: there was a trend for lower arterial oxygenation between 24 and 96 h in fluid-resuscitated mice. SpO2, arterial oxygen saturation. P = 0.12 for group effect in repeated measures ANOVA. Abx, antibiotics; Infxn, infection.

DISCUSSION

Outcomes from severe pneumonia and other life-threatening infections have improved over the past several decades, largely due to improvements in supportive care (25). Importantly, of over 100 potential therapeutics that have improved survival in mouse models of sepsis, none has shown efficacy in large randomized controlled clinical trials. This impressive and expensive failure has appropriately inspired many researchers to question the value of animal models in this area of medicine (17, 59, 68). In response, several authors have proposed revising rodent models to more closely model the supportive care that sick patients receive (14, 40, 59, 60, 72). Common suggestions among these proposals include the use of clinically relevant human pathogens, effective antibiotics, and fluid resuscitation, so that animals survive the initial wave of bacterial burden and the associated cytokine storm and hemodynamic stress.

Reviewing the literature on animal models of pneumonia incorporating the use of antibiotics, we identified ~50 articles published since 1947, of which the most relevant are found in Table 1. The purpose of antibiotic use in these studies varied but could generally be classified into either 1) assessing the efficacy of a particular antibiotic or dosing regimen in regards microbiological end points, or 2) testing for therapeutic synergy (an experimental therapeutic molecule given with or without antibiotics). As we were developing a bacterial pneumonia model with improved clinical relevance, we could not find a single reference that varied parameters of antibiotic timing, pathogen load, and fluid resuscitation in a way that facilitated understanding of how these methodologic variables affected the model.

Choice of Pathogen

Broadly speaking, a model of infectious pneumonia requires that a bacterial species is capable of replication and causing lung injury in vivo. Thus, either a virulent pathogen must be used or the host must be weakened first so that organisms that normally lack virulence in that species can establish a foothold. As shown in Table 1, researchers seeking to induce pneumonia in mice with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter cloacae have commonly first made mice neutropenic with cytotoxic chemotherapy. In contrast, more virulent bacterial species such as Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and S. pneumoniae readily establish serious lung infections in a variety of mouse strains. We selected an invasive strain of S. pneumoniae because of the high associated morbidity in patients resulting from translocation from the lung into the systemic circulation. We elected to inoculate intranasally under isoflurane anesthesia given the speed and reliability of these methods.

In our work with the ATCC 49619 strain without antibiotic therapy, it has been our consistent observation that the best predictor of death is systemic bacterial spread rather than the severity of pneumonia or gas exchange abnormalities. Using the 108 dose without antibiotics, we observed that mice either 1) developed worsening hypothermia and died around day 3 (in association with high burdens of bacteria in spleen and blood), or 2) recovered with steadily improving health (weight gain, temperature recovery, oxygenation, sterilization of cultures of blood and spleen) through at least day 7 (23). Thus, with this dose, the outcome is stochastic: recovery or death from overwhelming infection. At substantially lower doses (107 or lower), no mice progressed to develop worsening hypothermia or high-grade bacteremia, although histological evidence of pneumonia could be clearly demonstrated at day 7 (Fig. 1D). Notably, the inoculation dose required to produce severe pneumonia with the ATCC 49619 strain we used was high relative to another commonly used pneumococcal strain, ATCC 6303, which has been shown to induce lethal disease with inocula of 104–105 CFU (5, 62). Researchers most interested in studying mechanisms of early protective innate immunity may wish to utilize this strain instead.

The Use of Antibiotics in Animal Models of Pneumonia

Much has been learned over the last 50 years about innate immune responses to bacterial infections using animal models. Researchers most interested in early protective innate immune mechanisms and pathogen-host interactions would likely not be interested in using antibiotics that promptly kill the pathogen of interest. However, for researchers interested in modeling the clinical syndrome of sepsis in patients, we agree with consensus recommendations (39, 57) to incorporate the most salient aspects of care these patients receive, namely antibiotic and fluid therapy. Many patients die from organ dysfunction that persists despite pathogen eradication, and we believe that improved models of this clinical scenario are needed to inform both mechanistic study and therapeutic discovery.

Antibiotic Timing and Dose

As can readily be appreciated by reviewing Table 1, there has been considerable variability in antibiotic dosing and timing. We selected ceftriaxone because the ATCC 49619 strain has intermediate susceptibility to penicillin and because ceftriaxone is a first-line agent for treating serious pneumococcal infections in patients, including meningitis and pneumonia. In addition, ceftriaxone has favorable pharmacokinetics, permitting dosing every 12 h (66). As for timing, we, like others, found that there is a balance between allowing the infection to become established before antibiotics so that lung injury occurs but not waiting so long that the animal succumbs to overwhelming infection. One unexpected finding from this research was that mice treated with antibiotics more than 24 h postinfection had evidence of more severe organ injury than mice that did not receive antibiotics at all. Notably, Majhi and colleagues (44), using the same pneumococcal strain, found that ceftriaxone administration 18 h postinfection increased lung levels of TNFα compared with no antibiotic use. Similarly, Lawrenz et al. (37) reported that meropenem use during P. aeruginosa pneumonia reduced bacterial load but did not improve survival and was associated with more severe lung pathology. Why might this be?

Several studies (29, 33, 34) using either S. pneumoniae and S. aureus have reported that antibiotics that disrupt the bacterial cell wall (beta-lactams, vancomycin) result in worse survival and higher inflammation than antibiotics that inhibit protein synthesis (azithromycin, clindamycin, linezolid). One of these studies demonstrated that mice deficient in the molecular receptor for bacterial cell wall components (Toll-like receptor 2, TLR2) did not show this differential effect (29). Taken together with studies that demonstrate therapeutic synergy between beta-lactam antibiotics and immune suppression with either glucocorticoids (20, 81) or neutrophil elastase inhibition (48), the data suggest that rapid bacterial cell lysis induced by beta-lactam antibiotics unleashes a wave of inflammation that can add to organ injury and systemic illness. Given that broad-spectrum beta-lactam antibiotics are universally prescribed to patients presenting to care with suspected infection, we think that this is an important characteristic to incorporate into animal models of pneumonia. This feature of the model might be used to develop novel adjunctive therapeutics that can blunt this wave of inflammation in a more targeted fashion than glucocorticoids.

Fluid Resuscitation

Although strong evidence for the quantity and timing of fluids in sepsis is lacking, fluid resuscitation is universally recommended for patients presenting with severe infections (61). Because pneumonia damages the alveolar-capillary barrier, Starling forces dictate that higher filtration pressure in the lung capillaries will produce greater alveolar flooding, gas exchange abnormalities, and lung stiffness (9). In patients with pneumonia, this translates to increasing the risk that ARDS and progressive respiratory failure will develop. Indeed, a large randomized controlled trial has demonstrated that giving less fluids to patients with ARDS after they are out of shock improved oxygenation and reduced time on the ventilator (82). Although several groups have developed models of abdominal sepsis with fluid and antibiotic resuscitation (51, 58, 71), much less research has been done with mouse models of pneumonia and fluid resuscitation. As we report here, fluid resuscitation in our model of pneumonia increases lung edema and reduces lung compliance. This feature of the model might be used to understand the effects of different fluid types and to delineate dynamic changes in barrier integrity over time.

End Points and Timing

Finally, we have attempted to study clinically meaningful end points in this model, including survival, lung inflammation, oxygenation, compliance, body temperature dysregulation, and inflammatory cytokine analysis in the airspaces and peripheral blood (Table 2). Oxygenation, as measured by cervical pulse oximetry in freely moving animals, is an especially attractive modality given its potential for repeated testing over days. Unfortunately, although it is reproducible over time in individual animals, the within-group variability of the measurement is moderately high in bacterial pneumonia in our experience, requiring large numbers of mice to ensure consistent results.

Table 2.

Summary of experimental end points

| Experimental End Point | Clinical Correlate | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic WBC | Systemic WBC | Leukopenia may occur during overwhelming infection in immunocompetent patients. |

| Temperature | Temperature | In mouse models of bacterial sepsis, the severity of hypothermia is predictive of bacterial load and death (5, 23). This may be partly due to standard housing conditions for mice, which maintain ambient temperature below their thermoneutral zone (18). |

| SpO2 | SpO2 | Repetitive noninvasive measurement of arterial hypoxemia in freely moving mice provides an important physiologic end point; however, within-group variability necessitates large n for adequate statistical power. |

| Excess lung water | Pulmonary edema | Volume measurement of edema in the interstitial and alveolar spaces above the average for a mouse of a given size. Requires measurement of lung and blood hemoglobin; assumes no significant alveolar hemorrhage. |

| Wet-dry ratio | Pulmonary edema | Simpler method for measurement of lung edema; reduced by processes that increase the dry weight of the lung (e.g., high airspace protein concentration), meaning that it can lead to an underestimate of lung edema. |

| BAL protein | Not typically measured | Increased by high alveolar-capillary barrier permeability and frequently used in animal studies as an overall indicator of lung injury. However, BAL protein concentration is also increased by effective alveolar fluid clearance, meaning that measurement must be interpreted in the context of other end points. |

| BAL cellularity/differential | BAL cellularity/differential | Infrequently used clinically but can be helpful in determining the etiology of lung injury (e.g., lymphocyte predominant vs. neutrophil predominant). Dynamic temporally as tissue inflammation transitions to resolution. |

| Lung histology | Lung pathology | Rarely obtained clinically, especially early in disease processes. Labor-intensive but important end point in animal studies, provides context for other end points. |

| Lung compliance | Lung compliance | Measured following neuromuscular blockade in mice, compliance is an independent risk factor for death in ARDS (52) and is a component of the Murray Lung Injury Score (50). |

| Chemokines/cytokines | Biomarkers | Promise for improving clinical trial design by reducing heterogeneity in sepsis and ARDS (46). Increasing numbers of targeted therapeutics are available for research and clinical trials (e.g., IL-6, IL-1, TNF-α signaling). |

| Bacteremia | Bacteremia | Independent risk factor for death during pneumonia caused by the pneumococcus and other pathogens (19, 43). |

| BUN | BUN | Neither BUN nor creatinine distinguishes renal hypoperfusion states from true kidney damage. The same problem confronts clinical medicine and clinical trials. |

| ALT | ALT | Commonly increased in moderate-severe sepsis in patients (25) and previously demonstrated in models of abdominal sepsis in mice (71). Although centrilobular necrosis, portal inflammation, steatosis, hepatocellular apoptosis, and cholangitis have been described in patients dying of sepsis, up to a third of these patients may have no discernible histologic injury despite laboratory abnormalities (36). |

Abx, antibiotics; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; SpO2, arterial oxygen saturation; WBC, white blood cells.

By adjusting the dose of bacteria and the timing of antibiotics, it is possible to achieve nearly 100% survival at various time intervals after bacterial inoculation. This approach affords the opportunity to study both the development and resolution of lung injury. Importantly, focusing on the resolution phase may allow for the development of therapeutics that can hasten organ repair and recovery, a critical need for survivors of severe pneumonia who often languish in intensive care units with multiorgan dysfunction.

Limitations

For practical reasons (cost and availability), we used a single strain of young healthy female mice. The important influence of background strain has been extensively discussed in literature, including effects on the innate immune response to various pathogens (72). Investigators have demonstrated differences in the innate immune response to bacterial pneumonia in older mice, with increased neutrophil accumulation in the airspaces following challenge with S. pneumoniae (83), S. aureus, and K. pneumoniae (15), though the opposite has been reported with P. aeruginosa (10). Although age-dependent increases in mortality have been identified with several rodent sepsis models, including cecal ligation and puncture and endotoxemia, results with pneumonia have been mixed (70). Interestingly, aged mice do have increased susceptibility to hypothermia after endotoxin and cecal ligation and puncture (26, 64), with the severity of hypothermia predictive of both plasma IL-6 levels and later mortality (64). Similarly, Maddens and colleagues (42) reported age-dependent severity of septic acute kidney injury in mice using a model of uterine ligation and inoculation of E. coli. Thus, the relatively mild decreases in renal and hepatic function identified in our young mice might be more pronounced in older mice.

The use of high-dose pneumococcus inoculations does not exactly recapitulate the typical course of pneumococcal pneumonia in patients, in which an infection grows gradually from small numbers of organisms, overcoming successive waves of host defense over a period of many hours to a few days. In young healthy mice, low-dose infections are rapidly cleared, even without antibiotics. A possible alternative approach, used as we have documented in Table 1 with less virulent pathogens, would be to induce immunosuppression and then use a much smaller pneumococcal inoculum.

Similarly, the administration of fluids by intraperitoneal route over several days does not precisely mirror the treatment of patients, who by some clinically recommended guidelines receive 30 mL/kg bolus intravenous fluids within 1 or 2 h of arrival in the emergency department (25). Given the wave of inflammation that may be precipitated by beta-lactam-induced lysis of pneumococci, it is conceivable that the proximity of the initial dose of antibiotics and abrupt increase in hydrostatic pressure following bolus intravenous fluids makes the alveolar-capillary barrier especially susceptible to increased extravasation of edema fluid into the airspaces. Although the placement of venous catheters in mice can be onerous, it is possible to administer bolus fluids and give antibiotics by retro-orbital injection, an approach we are now developing.

Conclusions

In summary, we provide a review of prior studies employing antibiotics in murine models of pneumonia, efforts that began over 70 years ago (Table 1). In addition, we carried out a series of mouse experiments in which we systematically varied the infectious load, the timing of antibiotics, and fluid resuscitation, with the goal of demonstrating how this model of pneumococcal pneumonia can be adapted to study clinical end points that have relevance to critically ill patients with acute respiratory failure (Table 2). Although animal models have inherent and important limitations, it is our hope that improved mouse models with enhanced clinical relevance may expedite the testing of novel therapies targeting the development and resolution of severe pneumonia and the acute respiratory distress syndrome, including both pulmonary and systemic consequences.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant 1P50CA180890 and the Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products. Additional support was provided by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01-HL-51854, R37-HL-51856, R01-HL-134828, and U54-HL-147127. R. H. Croze also received support from National Institute of General Medical Sciences Training Grant T32-GM-008440 (PI: Judith Hellman). O. Bernard received support from the Fonds de dotation de recherche en santé respiratoire (FRSR), 2016 tender issued jointly with The Fondation du Souffle (FdS).

DISCLAIMERS

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.E.G., O.B., C.S.C., and M.A.M. conceived and designed research; J.E.G., O.B., L.C., R.H.C., J.T.R., N.N., X.W., J.A., and X.F. performed experiments; J.E.G., O.B., and R.H.C. analyzed data; J.E.G., O.B., L.C., R.H.C., C.S.C., and M.A.M. interpreted results of experiments; J.E.G. and O.B. prepared figures; J.E.G. and O.B. drafted manuscript; J.E.G., O.B., R.H.C., J.T.R., N.N., C.S.C., and M.A.M. edited and revised manuscript; J.E.G., O.B., L.C., R.H.C., J.T.R., N.N., X.W., J.A., X.F., C.S.C., and M.A.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Hanjing Zhuo for assistance with statistical analysis. We also thank Dr. Rachel Chambers for guidance on pneumococcal strain selection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdulnour RE, Sham HP, Douda DN, Colas RA, Dalli J, Bai Y, Ai X, Serhan CN, Levy BD. Aspirin-triggered resolvin D1 is produced during self-resolving gram-negative bacterial pneumonia and regulates host immune responses for the resolution of lung inflammation. Mucosal Immunol 9: 1278–1287, 2016. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansfield MJ, Woods DE, Johanson WG Jr. Lung bacterial clearance in murine pneumococcal pneumonia. Infect Immun 17: 195–204, 1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bansal S, Chhibber S. Curcumin alone and in combination with augmentin protects against pulmonary inflammation and acute lung injury generated during Klebsiella pneumoniae B5055-induced lung infection in BALB/c mice. J Med Microbiol 59: 429–437, 2010. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.016873-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bansal S, Chhibber S. Phytochemical-induced reduction of pulmonary inflammation during Klebsiella pneumoniae lung infection in mice. J Infect Dev Ctries 8: 838–844, 2014. doi: 10.3855/jidc.3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bast DJ, Yue M, Chen X, Bell D, Dresser L, Saskin R, Mandell LA, Low DE, de Azavedo JC. Novel murine model of pneumococcal pneumonia: use of temperature as a measure of disease severity to compare the efficacies of moxifloxacin and levofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48: 3343–3348, 2004. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.9.3343-3348.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhan U, Podsiad AB, Kovach MA, Ballinger MN, Keshamouni V, Standiford TJ. Linezolid has unique immunomodulatory effects in post-influenza community acquired MRSA pneumonia. PLoS One 10: e0114574, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanqué R, Meakin C, Millet S, Gardner CR. Hypothermia as an indicator of the acute effects of lipopolysaccharides: comparison with serum levels of IL1β, IL6 and TNFα. Gen Pharmacol 27: 973–977, 1996. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)02141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bucior I, Abbott J, Song Y, Matthay MA, Engel JN. Sugar administration is an effective adjunctive therapy in the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 305: L352–L363, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00387.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calfee CS, Matthay MA. Nonventilatory treatments for acute lung injury and ARDS. Chest 131: 913–920, 2007. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen MM, Palmer JL, Plackett TP, Deburghgraeve CR, Kovacs EJ. Age-related differences in the neutrophil response to pulmonary pseudomonas infection. Exp Gerontol 54: 42–46, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christaki E, Opal SM, Keith JC Jr, Kessimian N, Palardy JE, Parejo NA, Tan XY, Piche-Nicholas N, Tchistiakova L, Vlasuk GP, Shields KM, Feldman JL, Lavallie ER, Arai M, Mounts W, Pittman DD. A monoclonal antibody against RAGE alters gene expression and is protective in experimental models of sepsis and pneumococcal pneumonia. Shock 35: 492–498, 2011. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31820b2e1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Hennezel L, Ramisse F, Binder P, Marchal G, Alonso JM. Effective combination therapy for invasive pneumococcal pneumonia with ampicillin and intravenous immunoglobulins in a mouse model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45: 316–318, 2001. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.316-318.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickson EW, Heard SO, Chu B, Fraire A, Brueggemann AB, Doern GV. Partial liquid ventilation with perfluorocarbon in the treatment of rats with lethal pneumococcal pneumonia. Anesthesiology 88: 218–223, 1998. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199801000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Efron PA, Mohr AM, Moore FA, Moldawer LL. The future of murine sepsis and trauma research models. J Leukoc Biol 98: 945–952, 2015. doi: 10.1189/jlb.5MR0315-127R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esposito AL, Pennington JE. Effects of aging on antibacterial mechanisms in experimental pneumonia. Am Rev Respir Dis 128: 662–667, 1983. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.128.4.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang X, Abbott J, Cheng L, Colby JK, Lee JW, Levy BD, Matthay MA. Human mesenchymal stem (stromal) cells promote the resolution of acute lung injury in part through lipoxin A4. J Immunol 195: 875–881, 2015. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fink MP. Animal models of sepsis. Virulence 5: 143–153, 2014. doi: 10.4161/viru.26083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganeshan K, Chawla A. Warming the mouse to model human diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol 13: 458–465, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Vidal C, Fernández-Sabé N, Carratalà J, Díaz V, Verdaguer R, Dorca J, Manresa F, Gudiol F. Early mortality in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: causes and risk factors. Eur Respir J 32: 733–739, 2008. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00128107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghoneim HE, McCullers JA. Adjunctive corticosteroid therapy improves lung immunopathology and survival during severe secondary pneumococcal pneumonia in mice. J Infect Dis 209: 1459–1468, 2014. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gotts JE, Abbott J, Fang X, Yanagisawa H, Takasaka N, Nishimura SL, Calfee CS, Matthay MA. Cigarette smoke exposure worsens endotoxin-induced lung injury and pulmonary edema in mice. Nicotine Tob Res 19: 1033–1039, 2017. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gotts JE, Abbott J, Matthay MA. Influenza causes prolonged disruption of the alveolar-capillary barrier in mice unresponsive to mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 307: L395–L406, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00110.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gotts JE, Chun L, Abbott J, Fang X, Takasaka N, Nishimura SL, Springer ML, Schick SF, Calfee CS, Matthay MA. Cigarette smoke exposure worsens acute lung injury in antibiotic-treated bacterial pneumonia in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 315: L25–L40, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00405.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gotts JE, Matthay MA. Sepsis: pathophysiology and clinical management. BMJ 353: i1585, 2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Habicht GS. Body temperature in normal and endotoxin-treated mice of different ages. Mech Ageing Dev 16: 97–104, 1981. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(81)90037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iizawa Y, Kitamoto N, Hiroe K, Nakao M. Streptococcus pneumoniae in the nasal cavity of mice causes lower respiratory tract infection after airway obstruction. J Med Microbiol 44: 490–495, 1996. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-6-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacolot A, Judel C, Chaumais MC, Louchahi K, Nicolas P, Marchand S, Petitjean O, Mimoz O. Animal model methodology: immunocompetent or leucopenic rats, which is the best? Results from a model of experimental pneumonia due to derepressed cephalosporinase-producing Enterobacter cloacae. Chemotherapy 58: 129–133, 2012. doi: 10.1159/000337061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacqueline C, Broquet A, Roquilly A, Davieau M, Caillon J, Altare F, Potel G, Asehnoune K. Linezolid dampens neutrophil-mediated inflammation in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-induced pneumonia and protects the lung of associated damages. J Infect Dis 210: 814–823, 2014. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacqueline C, Roquilly A, Desessard C, Boutoille D, Broquet A, Le Mabecque V, Amador G, Potel G, Caillon J, Asehnoune K. Efficacy of ceftolozane in a murine model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute pneumonia: in vivo antimicrobial activity and impact on host inflammatory response. J Antimicrob Chemother 68: 177–183, 2013. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joly-Guillou ML, Wolff M, Pocidalo JJ, Walker F, Carbon C. Use of a new mouse model of Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia to evaluate the postantibiotic effect of imipenem. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41: 345–351, 1997. doi: 10.1128/AAC.41.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jorgensen JH, Doern GV, Ferraro MJ, Knapp CC, Swenson JM, Washington JA. Multicenter evaluation of the use of Haemophilus test medium for broth microdilution antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Streptococcus pneumoniae and development of quality control limits. J Clin Microbiol 30: 961–966, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karlström A, Boyd KL, English BK, McCullers JA. Treatment with protein synthesis inhibitors improves outcomes of secondary bacterial pneumonia after influenza. J Infect Dis 199: 311–319, 2009. doi: 10.1086/596051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karlström A, Heston SM, Boyd KL, Tuomanen EI, McCullers JA. Toll-like receptor 2 mediates fatal immunopathology in mice during treatment of secondary pneumococcal pneumonia following influenza. J Infect Dis 204: 1358–1366, 2011. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karzai W, Cui X, Mehlhorn B, Straube E, Hartung T, Gerstenberger E, Banks SM, Natanson C, Reinhart K, Eichacker PQ. Protection with antibody to tumor necrosis factor differs with similarly lethal Escherichia coli versus Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia in rats. Anesthesiology 99: 81–89, 2003. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koskinas J, Gomatos IP, Tiniakos DG, Memos N, Boutsikou M, Garatzioti A, Archimandritis A, Betrosian A. Liver histology in ICU patients dying from sepsis: a clinico-pathological study. World J Gastroenterol 14: 1389–1393, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lawrenz MB, Biller AE, Cramer DE, Kraenzle JL, Sotsky JB, Vanover CD, Yoder-Himes DR, Pollard A, Warawa JM. Development and evaluation of murine lung-specific disease models for Pseudomonas aeruginosa applicable to therapeutic testing. Pathog Dis 73: ftv025, 2015. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftv025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JS, Su X, Rackley C, Matthay MA, Gupta N. Priming with endotoxin increases acute lung injury in mice by enhancing the severity of lung endothelial injury. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 294: 165–172, 2011. doi: 10.1002/ar.21244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis AJ, Lee JS, Rosengart MR. Translational sepsis research: spanning the divide. Crit Care Med 46: 1497–1505, 2018. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewis AJ, Seymour CW, Rosengart MR. Current murine models of s epsis. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 17: 385–393, 2016. doi: 10.1089/sur.2016.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lutsar I, Friedland IR, Jafri HS, Wubbel L, Ahmed A, Trujillo M, McCoig CC, McCracken GH Jr. Factors influencing the anti-inflammatory effect of dexamethasone therapy in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. J Antimicrob Chemother 52: 651–655, 2003. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maddens B, Vandendriessche B, Demon D, Vanholder R, Chiers K, Cauwels A, Meyer E. Severity of sepsis-induced acute kidney injury in a novel mouse model is age dependent. Crit Care Med 40: 2638–2646, 2012. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182591ebe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Magret M, Lisboa T, Martin-Loeches I, Máñez R, Nauwynck M, Wrigge H, Cardellino S, Díaz E, Koulenti D, Rello J; EU-VAP/CAP Study Group . Bacteremia is an independent risk factor for mortality in nosocomial pneumonia: a prospective and observational multicenter study. Crit Care 15: R62, 2011. doi: 10.1186/cc10036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Majhi A, Adhikary R, Bhattacharyya A, Mahanti S, Bishayi B. Levofloxacin-ceftriaxone combination attenuates lung inflammation in a mouse model of bacteremic pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae via inhibition of cytolytic activities of pneumolysin and autolysin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58: 5164–5180, 2014. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03245-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matthay MA, Zemans RL, Zimmerman GA, Arabi YM, Beitler JR, Mercat A, Herridge M, Randolph AG, Calfee CS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 5: 18, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meyer NJ, Calfee CS. Novel translational approaches to the search for precision therapies for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med 5: 512–523, 2017. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30187-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moine P, Vallée E, Azoulay-Dupuis E, Bourget P, Bédos JP, Bauchet J, Pocidalo JJ. In vivo efficacy of a broad-spectrum cephalosporin, ceftriaxone, against penicillin-susceptible and -resistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae in a mouse pneumonia model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 38: 1953–1958, 1994. doi: 10.1128/AAC.38.9.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morinaga Y, Yanagihara K, Araki N, Yamada K, Seki M, Izumikawa K, Kakeya H, Yamamoto Y, Yamada Y, Kohno S, Kamihira S. In vivo efficacy of sivelestat in combination with pazufloxacin against Legionella pneumonia. Exp Lung Res 36: 484–490, 2010. doi: 10.3109/01902141003728874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Müller-Redetzky HC, Wienhold SM, Berg J, Hocke AC, Hippenstiel S, Hellwig K, Gutbier B, Opitz B, Neudecker J, Rückert J, Gruber AD, Kershaw O, Mayer K, Suttorp N, Witzenrath M. Moxifloxacin is not anti-inflammatory in experimental pneumococcal pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother 70: 830–840, 2015. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murray JF, Matthay MA, Luce JM, Flick MR. An expanded definition of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis 138: 720–723, 1988. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.3.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]