Abstract

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), defined as a pathological expansion of the largest artery in the abdomen, is a common vascular disease that frequently leads to death if rupture occurs. Once diagnosed, clinicians typically evaluate the rupture risk based on maximum diameter of the aneurysm, a limited metric that is not accurate for all patients. In this study, we worked to evaluate additional distinguishing factors between growing and stable murine aneurysms toward the aim of eventually improving clinical rupture risk assessment. With the use of a relatively new mouse model that combines surgical application of topical elastase to cause initial aortic expansion and a lysyl oxidase inhibitor, β-aminopropionitrile (BAPN), in the drinking water, we were able to create large AAAs that expanded over 28 days. We further sought to develop and demonstrate applications of advanced imaging approaches, including four-dimensional ultrasound (4DUS), to evaluate alternative geometric and biomechanical parameters between 1) growing AAAs, 2) stable AAAs, and 3) nonaneurysmal control mice. Our study confirmed the reproducibility of this murine model and found reduced circumferential strain values, greater tortuosity, and increased elastin degradation in mice with aneurysms. We also found that expanding murine AAAs had increased peak wall stress and surface area per length compared with stable aneurysms. The results from this work provide clear growth patterns associated with BAPN-elastase murine aneurysms and demonstrate the capabilities of high-frequency ultrasound. These data could help lay the groundwork for improving insight into clinical prediction of AAA expansion.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This work characterizes a relatively new murine model of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) by quantifying vascular strain, stress, and geometry. Furthermore, Green-Lagrange strain was calculated with a novel mapping approach using four-dimensional ultrasound. We also compared growing and stable AAAs, finding peak wall stress and surface area per length to be most indicative of growth. In all AAAs, strain and elastin health declined, whereas tortuosity increased.

Keywords: abdominal aortic aneurysm, biomechanics, elastin, four-dimensional ultrasound, murine model

INTRODUCTION

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a pathological condition characterized by a dilation of the abdominal aorta, usually in the infrarenal region (22, 24). It is a relatively common disease affecting ∼1.4% of the population between 50 and 84 yr of age in the United States, or 1.1 million people (11). Although dilation itself is often asymptomatic, the major concern is aneurysm rupture when severe internal hemorrhaging causes 90% of rupture patients to die before reaching the hospital (32). If an AAA is detected before rupture, clinicians must decide whether to treat the aneurysm or watch and wait. Treatment via open surgical intervention has a relatively high mortality rate, whereas endovascular repair can lead to future complications such as endoleaks (43). Alternatively, surveilling the AAA can be risky given the lethal nature of rupture and the psychological harm an aneurysm diagnosis can cause (2), leading to a challenging risk assessment. The most recent clinical guidelines from the Society for Vascular Surgery primarily use the maximum diameter of the AAA to assess risks (11), but many aneurysms rupture before reaching the upper threshold, and many more would likely not rupture until well after that diameter (7). Given the ambiguity regarding overall intervention criteria, finding more robust and accurate metrics for rupture risk assessment is a clear unmet clinical need (25, 27, 39).

Under the assumption that a rapidly growing AAA is one that will eventually rupture (7), the driving motivation of this study is to identify differences between growing and stable AAAs as a corollary for rupture risk assessment. Specifically, we use a relatively new murine model of growing and stable aneurysms to assess metrics indicating AAA progression. The BAPN-elastase murine model, first published in 2017 (31), uses topical elastase to create an AAA and adds β-aminopropionitrile (BAPN) to the drinking water to promote continued aneurysm growth. Elastase breaks down medial elastin and causes an inflammatory response (28), leading to the formation of a stable AAA when applied topically (28, 31). Yet when BAPN, a lysyl oxidase (LOX) inhibitor that prevents cross-link formation within and between elastin and collagen (41), is also given continuously to the animal, a chronic, growing AAA is created (31). Thus, comparing elastase only and BAPN + elastase treatments enables us to assess aneurysm stability. Moreover, BAPN alone, without active elastase, has been found to have no effect on the aortic size or histology (31). Therefore, BAPN combined with heat-inactivated elastase (sham) can be evaluated as a negative control, accounting for surgical effects and providing insight into the impact of LOX inhibition alone.

We also further develop and novelly apply ultrasound imaging techniques to characterize in vivo aortic geometry and kinematics. Through the use of four-dimensional ultrasound (4DUS), we collect serial cine loops of two-dimensional (2D) brightness mode (B-mode)-like images slice by slice over a prescribed distance, followed by reconstruction of the data to visualize volume changes throughout the cardiac cycle. This murine imaging technique was originally developed and validated for cardiac applications (12, 42), but it can also be used for vascular imaging in both healthy and diseased states (10). This technique allows us to estimate advanced geometric indices such as vessel tortuosity and surface area and biomechanical metrics such as arterial strain and stress. By identifying the relationships between these indices and AAA growth in mice, the hope is to eventually advance aneurysm rupture risk assessment beyond maximum diameter, an effort of significant interest to the field (6, 13, 16, 17, 19, 21, 23, 32, 35). Furthermore, the initial work with this murine model focused on quantifying diameter and inflammation (31), whereas here we provide key additional insight by longitudinally characterizing additional aortic metrics with translationally relevant imaging approaches. Although the findings from these experiments will eventually need to be compared with clinical data, this study does improve our understanding of aneurysm disease by providing greater insight into why some AAAs expand whereas others remain stable.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental design overview.

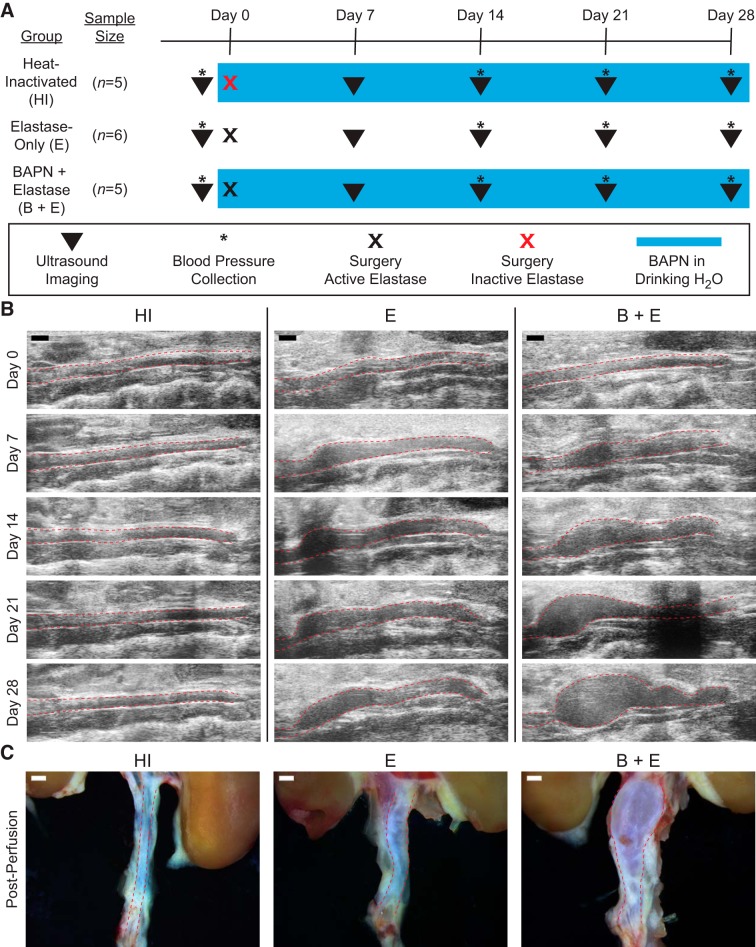

Ten-week-old male C57BL/6J mice (Jackson, Bar Harbor, ME) were randomized into three experimental groups across two cohorts to study stable aneurysms, growing aneurysms, and sham procedure controls (Fig. 1A). Specifically, both the stable elastase-only group (E; n = 6) and the growing BAPN-elastase group (B + E; n = 5) underwent topical peri-adventitial elastase application to induce aneurysms (28, 47). In addition, the BAPN-elastase group received 0.2% BAPN fumarate (A3134; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in the drinking water throughout the study, beginning 2 days before surgery (31). As a negative control, a heat-inactivated (HI) group (n = 5) also underwent surgery and received BAPN in the drinking water, but the topical elastase applied was inactivated by heating to 100°C for 30 min before use (31). All animals were monitored with ultrasound imaging (Fig. 1B) for 4 wk after surgery, after which mice were euthanized by isoflurane overdose and bilateral pneumothorax. After perfusion with agarose, the aorta and kidneys were harvested from each animal (Fig. 1C) and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (28908; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) for histological analysis. All animal procedures were approved by the Purdue Animal Care and Use Committee.

Fig. 1.

Experimental groups and methods. A: timing schematic showing weekly imaging (▼), blood pressure collection (*), and experimental differences between groups. Schematic also denotes surgery with 5 mg/mL active elastase (black x) and heat-inactivated (HI) elastase (red x), and ongoing β-aminopropionitrile (BAPN) placed in drinking water (blue box), with normal drinking water for the elastase-only (E) group. B: weekly ultrasound images demonstrating HI as an aorta of healthy size, E as a stable aneurysm, and BAPN-elastase (B + E) as a growing aneurysm. C: gross anatomy images from representative animals after agarose perfusion. Red dashed lines in B and C indicate aorta boundary. Scale bar, 1 mm for all images.

Surgical procedure.

Animals were anesthetized with 1–3% isoflurane in 225 mL/min room air and underwent an open laparotomy. Approximately 4 mm of the infrarenal aorta was exposed from the surrounding supportive tissue through blunt dissection. Five microliters of porcine elastase (E7885; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at a concentration of 5 mg/mL was applied to the adventitial surface via a micropipette and allowed to remain for 5 min before flushing with 1 mL of saline solution three times. The abdomen was closed with sutures in the muscle and skin layers, ∼0.075 mg/kg buprenorphine was administered as an analgesic, and the animals were monitored for signs of distress during recovery.

Weekly monitoring.

We conducted weekly ultrasound imaging on anesthetized animals (1–3% isoflurane, 0.8 L/min medical-grade air) post-surgery for 4 wk as well as at baseline before surgery. For each imaging session, a Vevo 2100 system (FujiFilm VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada) with a 32-to 55-MHz frequency transducer (MS550D; 40-MHz center frequency) was used to collect standard B-mode images in long axes, along with ECG-gated kilohertz visualization (EKV) reconstructions showing a cine loop from systole to diastole. In addition, motion mode (M-mode) images were acquired in the middle of the aneurysm. 4DUS was also acquired by collecting serial 2D EKV loops in short axes every 200 µm at a frame rate of 700 Hz, beginning at the left renal vein and extending to the aortic trifurcation. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were estimated at baseline and at 2, 3, and 4 wk using a tail-cuff measurement system (CODA-HT2; Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). We followed the manufacturer’s instructions similarly to published (46) and validated (15) protocols, placing conscious animals on a heated stage within a restraining tube. After an acclimation period, systole and diastole were identified at least 20 times by the software when the animals were still, and the measurements were averaged to estimate each animal’s systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

Histology and immunohistochemistry.

After fixation, gross cuts were made every 2 to 3 mm along the infrarenal aorta, embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm-thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Movat’s pentachrome (MPC). Additional slides were stained for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; primary: rabbit anti-mouse, ab5694, Abcam; secondary polymer: MP-7451, Vector), developed with 3,3′diaminobenzidine (DAB; reddish brown; SK-4105, Vector), and counterstained with Gill’s II hematoxylin (light blue). We quantified the MPC histology in two ways. First, the medial layer (purple) and adventitial layer (yellow) were outlined in ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD) to obtain average thickness measurements by using the perimeter as a circumference and assuming a circular vessel. Second, we employed a semiquantitative elastin scoring methodology (Supplemental Fig. S1; supplemental material for this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9466496) using one image within each quadrant of the aorta taken at ×40 magnification. Four blinded reviewers scored randomized images on a scale of 1 to 5, where 5 corresponded to healthy elastin sheets present, 3 corresponded to degraded or unhealthy elastin fragments present, and 1 corresponded to no elastin present. All four individuals’ scores were averaged for each image.

Ultrasound image analysis.

Using the systolic frame of the serial 2D EKV short-axis loop at every imaging time point, we calculated the maximum cross-sectional area of the aortic lumen, from which the diameter was estimated as a maximum effective diameter (VevoLab; FujiFilm VisualSonics). Using multiple cardiac cycles of M-mode ultrasound, we measured both systolic (Dsys) and diastolic (Ddia) diameters near the middle of the aneurysm in triplicate. The average of the measurements was used to calculate Green-Lagrange circumferential cyclic strain (Eθθ) (9, 21):

| (1) |

Serial EKV images were reconstructed and interpolated using MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) to produce a four-dinensional (4D) data set with isotropic voxels. These data were loaded into SimVascular (44), and the lumen of each vessel was manually segmented at systole and diastole to create two distinct three-dimensional (3D) models of each. The centerlines from these 3D models were automatically estimated in SimVascular and loaded back into MATLAB with the models to calculate tortuosity, surface area, and circumferential strain using a custom script. Tortuosity was quantified as the diastolic centerline length divided by the Cartesian distance between the highest and lowest point. For strain, at every z-slice of the models equal to 0.05 mm, the area of the lumen at diastole and systole was extracted and converted to diameters for use in Eq. 1. To quantitatively compare between experimental groups, we estimated average strain within a predetermined region of interest (ROI). For animals with AAAs, a band 1 mm in height was placed at the maximum diameter, excluding regions of user-identified immense tortuosity or rapid expansion/contraction. Because the HI group had relatively constant aortic diameters, a band 4 mm in height halfway between the iliac trifurcation and the left renal vein was used to estimate where inactivated elastase was surgically applied. This 4-mm ROI was also used for the baseline data from the E and B + E groups since maximum diameter is arbitrary for these data as well. We also calculated the circumferential component of the Cauchy stress tensor, or hoop stress, by using the Law of Laplace for thin-walled cylinders (σθ) (30) using systolic blood pressure (p), maximum effective radius from ultrasound (r), and wall thickness from histology (t).

| (2) |

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed in Prism (version 8.1.0; GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Unless otherwise noted, a two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Tukey tests was performed with an overall type I error rate of α = 0.05.

RESULTS

Combination of elastase and BAPN reproducibly leads to continually expanding AAAs.

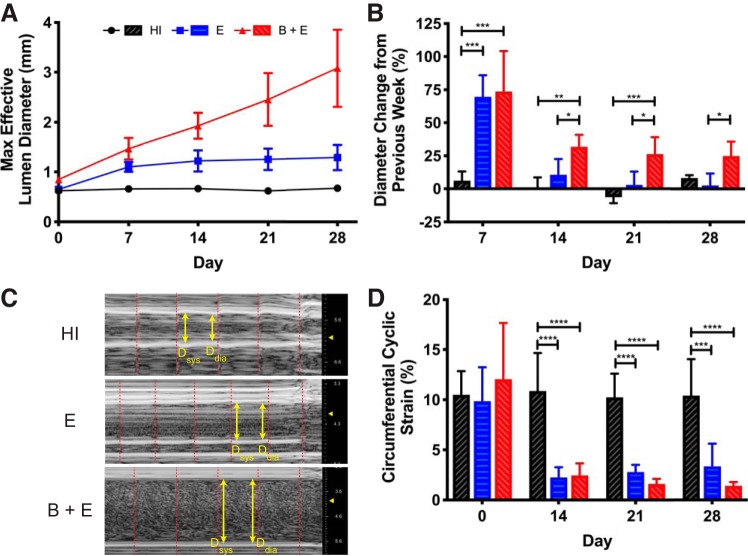

The maximum effective diameter confirmed the creation of growing AAAs, stable AAAs, and an age-matched control (Fig. 2A). The B + E mouse aortae continued to expand throughout the study, growing to 364% (SD 93) of their original size at the study end point. E mouse aortae dilated but plateaued at 198% (SD 38) of their original size, while the HI mouse aortae remained approximately the same size. The AAA growth rates (Fig. 2B) revealed that the E and B + E groups expanded rapidly in the first week. Then, starting at day 14, the growth rate of E mice was not significantly different than that of the HI group, whereas the B + E group growth rate was substantially greater than the E group rate (P < 0.05). Overall, the HI group can be considered a negative control with aortae at a normal size. Conversely, the E group developed stable aneurysms by day 14, and the B + E group developed continually expanding AAAs. Because the E group takes up to 14 days to stabilize, we focused our analysis on days 14, 21, and 28.

Fig. 2.

Simple ultrasound quantification. A: maximum effective diameter of aortic lumen calculated from short-axis ultrasound each week demonstrates 3 distinct experimental groups based on aortic size. Heat-inactivated (HI) group (SD smaller than marker size) remains a healthy size, whereas elastase with or without β-aminopropionitrile (BAPN) is enlarged. B: %change in lumen diameter from the previous week demonstrates that, beginning on day 14, BAPN causes significantly more growth than elastase only (P < 0.05). In addition, the elastase-only (E) group is significantly indistinguishable from the HI control after initial expansion. Because the E group takes ≤14 days to become a stable abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), analysis focuses on days 14, 21, and 28. C: day 21 representative M-mode ultrasound images (units in mm), with arrows designating sample systolic and diastolic points and dashed lines bounding cardiac cycles. D: Green-Lagrange circumferential cyclic strain calculated from M-mode measurements reveals reduction of strain with elastase application (P < 0.001). *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001.

Strain reduction after elastase application.

Aneurysmal vessels appeared to pulsate less than vessels in control mice (Fig. 2C). Consequently, circumferential strain based on M-mode images decreased significantly for both the E and B + E groups (P < 0.001; Fig. 2D). All three groups had similar mean baseline strain values of ∼10%. Once elastase was applied, regardless of whether the aneurysm was growing, there was a reduction in mean strain below 5%, whereas the HI group remained above 10%.

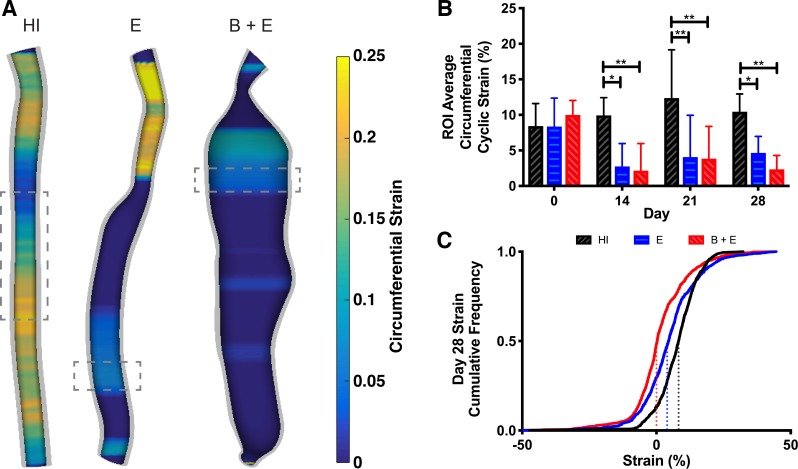

Taking advantage of our 4DUS data, we calculated circumferential strain every 0.05 mm along the aorta (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. S2). From these maps, strain appeared heterogenous, but with overall lower strain values in aneurysmal regions and higher values in healthy regions. The ROI-averaged strain values (Fig. 3B) were similar to the values from M-mode (Fig. 2D). Significant reductions in strain were noted in both groups where elastase was applied. To fully describe the distribution of strain values along the entire infrarenal aorta, we generated a cumulative frequency plot for all animals on day 28 (Fig. 3C). By fitting a sigmoidal curve and estimating the inflection point, corresponding to the median strain value for each group, all three groups have significantly different inflection points (P < 0.0001). The HI group had the largest median strain value (8.3%), followed by the E group (4.0%), and then the B + E group shifted the farthest left (0.0%).

Fig. 3.

Cyclic strain by z-slice from 4-dimensional ultrasound (4DUS). A: visualization of strain at systole for representative animals on day 28. Values outside of the color bar bounds are represented as the respective minimum or maximum. Dashed boxes represent areas averaged for groupwise comparison in B. Four-millimeter height for heat-inactivated (HI) group and 1 mm for elastase-only (E) and β-aminopropionitrile-elastase (B + E) groups. B: average strain values from the region of interest (ROI) in each animal reveal that strain decreases once elastase is applied (P < 0.05), but no difference can be detected between growing and stable aneurysms. C: distribution of all strain values along infrarenal aorta for all animals on day 28 is shown as a cumulative frequency plot. Inflection point from sigmoidal fit corresponding to median strain value is significantly different for all 3 groups (P < 0.05), with HI = 8.3%, E = 4.0%, and B + E = 0.0%.*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01.

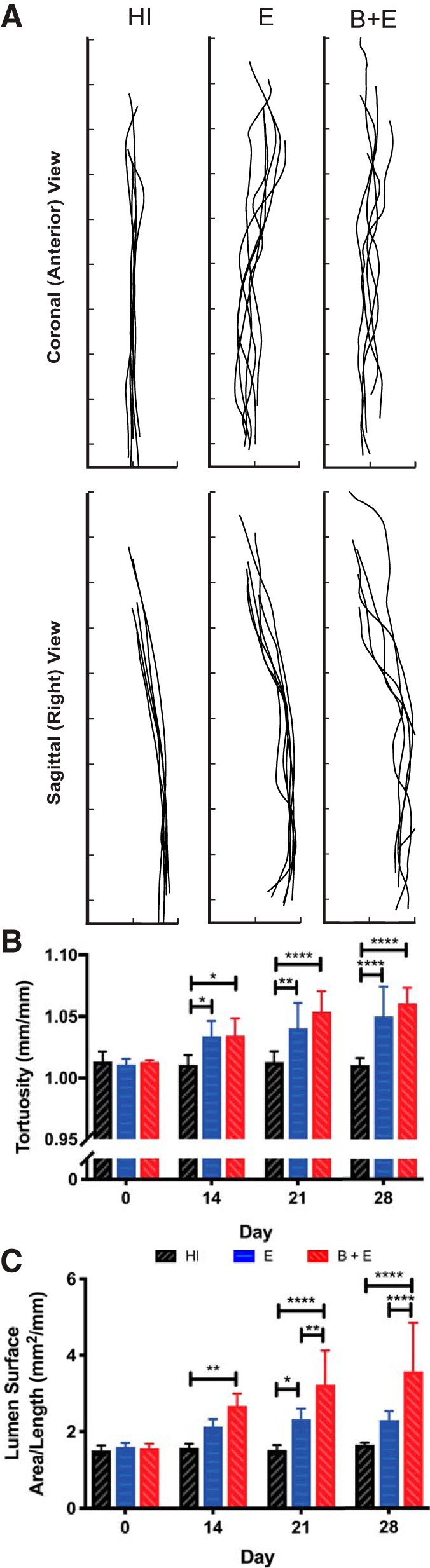

3D models reveal increased tortuosity and surface area in aneurysms.

Vessel centerlines appeared more heterogeneous and tortuous for the two AAA groups compared with control (Fig. 4A). Quantitatively (Fig. 4B), whereas the HI group was not perfectly straight (tortuosity = 1), the AAA groups were significantly more tortuous on days 14, 21, and 28 (P < 0.05). Although the E and B + E groups were not significantly different from one another, it appears that B + E mice could be trending toward higher tortuosity at later time points.

Fig. 4.

Geometric indices from 3-dimensional (3D) models. A: qualitative depiction of aorta centerlines on day 28. Interval spacing, 2 mm. B: quantitative measure of diastolic aorta tortuosity (centerline length/height) over time showing that groups with abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) are more tortuous. C: longitudinal measurements of surface area of diastolic aortic lumen divided by centerline length showing that the β-aminopropionitrile-elastase (B + E) group always had increased surface area/length once aneurysmal (P < 0.01). *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ****P ≤ 0.0001. E, elastase only; HI, heat inactivated.

Dividing the diastolic lumen surface area by centerline length, the B + E group had a significantly greater surface area per length metric than the HI control at all aneurysmal time points (P < 0.01; Fig. 4C). It was also significantly greater than the stable aneurysm group on days 21 and 28 (P < 0.01). Although the average surface area per length of the E group was greater than the average of the control at all aneurysmal time points, it was significant only on day 21 (P < 0.05).

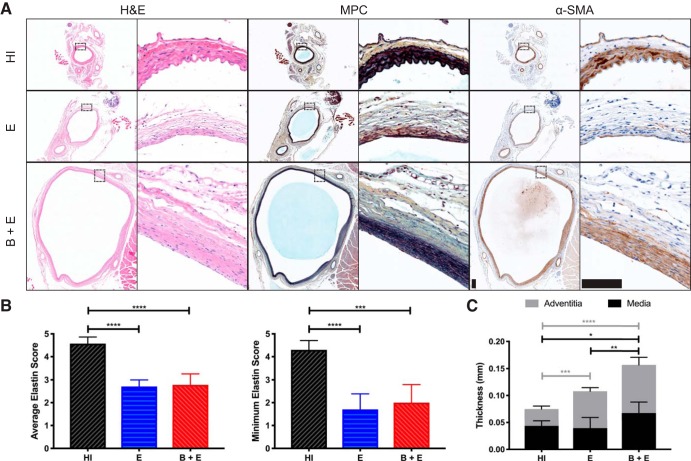

AAA formation corresponds with elastin degradation and collagen deposition.

The HI samples stained with MPC revealed healthy, black elastin organized in four lamellar units (Fig. 5A). The α-SMA staining confirmed that much of the purple medial layer in the MPC images comprised smooth muscle cells. There was also a yellow band of adventitial collagen surrounding this medial layer in all slides. In some mice in the E group, the medial layer seemed to almost disappear, showing little smooth muscle cell or elastin. In other mice in both the E and B + E groups, the medial layer was present, but the elastin layers did not have their quintessential healthy waviness. Instead, elastin fibers appeared small, linear, and scattered throughout the media.

Fig. 5.

Histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC). A: hemotoxin and eosin (H & E), Movat’s Pentachrome (MPC), and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) staining at ×4 (left) and ×40 (right) magnifications. Scale bar, 0.1 mm for all images. B: results of semiquantitative scoring analysis, where 5 = healthy elastin sheets present, 3 = degraded elastin fragments present, and 1 = elastin not present. Averaging all 4 quadrants (left) and using the minimum quadrant score (right) both reveal decreased elastin content in elastase-only (E) and β-aminopropionitrile-elastase (B + E) groups (P < 0.001). C: aortic wall thickness from histology, as defined by medial and adventitial layers. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001. HI, heat inactivated.

Overall elastin health was represented by the average semiquantitative score among all four quadrants (Fig. 5B, left). The worst level of degradation, represented by the minimum quadrant, showed similar trends between groups (Fig. 5B, right). Specifically, these data revealed significantly lower elastin scores for the groups with AAAs, both average and minimum scores (P < 0.001). E and B + E average quadrant scores had similar groupwise means of 2.7 (SD 0.3) and 2.8 (SD 0.5) out of 5, respectively. For minimum quadrant scores, although the difference was not significant, the E group had a mean of 1.7 (SD 0.7), whereas the B + E group mean was 2.0 (SD 0.4). From the average thickness measurement, we found that the average transmural thickness increased with aortic diameter (Fig. 5C). The medial thickness increased for the B + E group compared with the control (0.07 μm, SD 0.02 vs. 0.04 μm, SD 0.01, P < 0.05), and increased levels of collagen were also present in the adventitia of both AAA groups compared with control (E: 0.07 μm, SD 0.01; B + E: 0.09 μm, SD 0.01; HI: 0.03 μm, SD 0.01, P < 0.001). Additionally, effective radius measurements from histology and day 28 ultrasound images were significantly correlated (Pearson’s r = 0.93, P < 0.0001; Supplemental Fig. S4), demonstrating consistency.

Wall stress estimation reveals increased stress in growing AAAs.

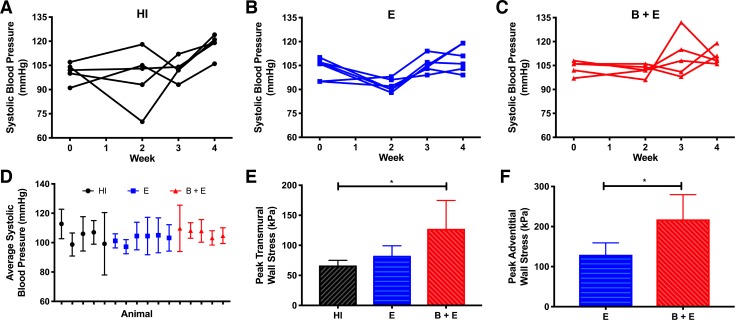

The systolic blood pressure (SBP) for each animal varied over time (Fig. 6, A–C). The time-averaged SBP did not reveal any trends between animals or groups (Fig. 6D) but was used for calculating wall stress for each animal to reduce noise. With the use of the average transmural thickness, the animals in the B + E group had higher transmural stress compared with mice in the HI group (P < 0.05; Fig. 6E). However, with the use of the thickness of only the adventitia instead of the whole wall, significantly higher stress was found in the B + E group compared with the E group (P < 0.05; Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6.

Peak hoop stress. A–C: systolic blood pressure over time for each group. D: systolic blood pressure averaged over time for each animal. E and F: peak hoop stress calculated with pressure from D, maximum effective radius from ultrasound, and transmural (E) or adventitial (F) thickness from histology. If adventitia is assumed to carry most of the load due to elastin degradation in the media, adventitial thickness should be used, and the β-aminopropionitrile-elastase (B + E) group has significantly greater hoop stress than the elastase-only (E) group (*P < 0.05). HI, heat inactivated.

DISCUSSION

The ability to distinguish between growing and stable AAAs remains an important unmet clinical need. In this study, we used a relatively new murine model using traditional and advanced volumetric ultrasound techniques. Our work demonstrated the capabilities of high-frequency 4DUS, especially when in vivo circumferential strain was estimated. This technique, combined with traditional M-mode analysis, revealed decreased strain in aneurysmal vessels. Our analysis also found these AAAs to be more tortuous and to have increased elastin fragmentation, an expected finding given the application of elastase. The addition of BAPN with the elastase, despite only having marginal effects on the aforementioned metrics, did cause significantly larger diameters, increased surface area per length, and increased wall stress compared with elastase-only aneurysms. Taken together, the addition or withholding of BAPN did allow for a comparison between growing and stable AAAs, respectively, using a number of biomechanical and geometric parameters assessed via high-frequency ultrasound.

The combination of BAPN with peri-adventitial, topical elastase treatment in mice (31) repeatably produced fusiform AAAs in the infrarenal aorta, the site most commonly found in humans (22, 24). In addition, compared with previous elastase-induced aneurysm models in rats (1) and mice (38), the BAPN-elastase model is surgically easier and promotes chronic growth beyond the initial inflammation and expansion that topical elastase alone creates (3). Our maximum AAA diameter results were almost identical to previous reports of the effects of topical elastase (31, 47) and the combination of BAPN plus elastase (31). The observed growth patterns suggest that initial expansion is dependent upon elastase application, but ongoing AAA growth is correlated with LOX inhibition. Because cross-linking is known to be reduced due to BAPN (41), the aorta continues to grow, and a chronic AAA model can be established. We also confirmed that BAPN by itself at a concentration of 0.2% had negligible effects on the vasculature, similar to the initial study (31). Specifically, in relation to diameter, the HI group remained at a constant, nonaneurysmal size throughout our study. Biomechanical and geometric characteristics were not affected by BAPN alone, as the HI group did not change from baseline. Histological images of the HI group also appeared within normal limits. Therefore, the HI group can indeed be considered a healthy negative control for this study.

In both animal models and human AAA patients, strain is becoming a metric of increased interest. Our results show a reduction in strain in elastase-induced aneurysms, as demonstrated previously with M-mode ultrasound (21, 35) and biomechanical testing (19). Additionally, the growing aneurysms we created had similarly reduced strain to the stable aneurysms (P > 0.05), with mean values <5%. This finding suggests that strain, although interesting, may not be a distinguishing factor between expanding and stable AAAs. However, multiple studies have proven strain to be heterogeneous in AAAs in both humans (26) and mice (10), highlighting the value of strain mapping compared with a single-point estimate. Emerging methodologies using speckle tracking (4, 13, 26) and/or a direct deformation approach (5) seek to create true strain maps, but these approaches require higher-resolution imaging and substantial computational power. As an alternative, we estimated circumferential strain slice by slice from 4DUS (Fig. 3), a process that can be completed in <1 h by trained users. Although results in some areas near aneurysmal shoulder regions or locations of increased tortuosity are inaccurate (i.e., below zero), likely due to segmentation artifacts or out-of-plane motion, the results from this 4DUS strain calculation likewise reveal noticeable heterogeneity in strain throughout the aorta for both healthy and aneurysmal aortae. Furthermore, a ROI approach helped improve the comparison between the three groups by reducing noise (Fig. 3B and Supplemental Fig. S5). To assess our volume-based strain analysis, ROI-averaged data were compared with M-mode results, revealing similar values (Figs. 2D and 3B). Although a comparison to region-based speckle tracking would also be interesting, M-mode makes similar assumptions to our approach and provides the most direct comparison of average circumferential strain. This suggests that both techniques can provide strain estimates, but the volumetric analysis provides data from substantially more axial locations compared with M-mode. Previous studies have also reported on aneurysm strain, but they either use the linear definition of strain (6) or are limited to a 2D analysis (6, 17), limiting their applicability for comparison with our results. In summary, our 4DUS strain calculation technique is a simple, computationally inexpensive method capable of obtaining Green-Lagrange strain estimates at many points along the infrarenal aorta.

The other biomechanical metric evaluated in this study, peak circumferential wall stress, is important since aortic rupture occurs when this wall stress exceeds the strength of the wall (25). Although finite element analysis (FEA) is a popular approach to estimating wall stress, the results are highly dependent upon accurate material properties and constitutive model assumptions (37). We instead used the Law of Laplace, which, although assuming a perfect, thin-walled cylinder where the stress distribution is uniform throughout, is a clinically relevant approach that allows for a quick estimation of circumferential stress based on the available pressure, thickness, and maximum diameter data. Because our analysis showed that AAA wall thickness was not constant, evaluating wall stress may be more representative and beneficial than maximum diameter alone. Our analysis also revealed that the E and B + E groups did not possess functional elastin, indicating that the collagen of the adventitia was the component of the aortic wall that was experiencing nearly all of the stress. Following this logic and with the use of the thickness of the adventitia rather than the whole wall, the Laplacian assumption of a single-layer, thin-walled vessel should be valid, and the data suggest increased stress in growing AAAs (Fig. 6F), a finding that aligns with published work in humans using both the Law of Laplace (23) and FEA (16, 32). As others are currently working on demonstrating (33, 36, 45), wall stress could become more clinically relevant once current imaging limitations prohibiting noninvasive wall thickness measurements are overcome in the future (14).

In addition to biomechanical information, our 4DUS imaging technique and creation of 3D models allowed for analysis of mouse-specific geometric indices. Recently, a study was published describing a decision tree algorithm using geometric indices as inputs and AAA rupture as the output (34). The findings suggested that various tortuosity metrics and surface area are significant indicators of AAA rupture (34). Our study did not find differences in tortuosity between growing and stable AAAs, but it did find significant differences in the surface area per length metric. Although it may have diluted the impact of small, localized E AAAs compared with HI control, we divided the surface area by centerline length to control for interanimal differences in the length of the aortic models. Although surface area is in many ways a function of maximum diameter, surface area offers a more holistic view correlating with both the size of the AAA and the length of aorta that is aneurysmal, an approach that our data suggest is useful when volumetric imaging is available.

Although we sought to evaluate large scale metrics of AAA growth, it is also important to understand the microscopic differences. One of the reasons for use of the elastase model is that elastin is clearly degraded in human AAAs (8). Our findings are similar to previous studies that found a correlation between aortic diameter, decreased elastin, and increased collagen content (40), in addition to the loss of a recognizable intimal layer (27). The first paper reporting on the elastase-BAPN model described elastin fragmentation, loss of smooth muscle cell order, and large amounts of collagen deposition in an elastase-only group, with exaggerated findings in a BAPN + elastase group (31). Although we observed many of the same factors and did not observe much of a difference between the E and B + E groups, there were some notable discrepancies from the previously published work (31). Specifically, the smooth muscle cells seemed to retain their layered order even without the elastin in both groups, and thick medial layers full of smooth muscle cells were frequently observed in the B + E group. This thicker medial layer was expected, as cross-linking is inhibited by BAPN. In addition, some regions of the aorta in the E group appeared to have no discernable media layers. In both groups where there was a medial layer, the elastin was obviously not functional; however, it is not clear whether the observed elastin is old degraded elastin, or new, immature de novo elastin. Additional analysis is needed at more time points to quantify the origin of the elastin and truly understand the implications of both treatment groups on the extracellular matrix.

The present study does have limitations. Although this study did not seek to understand the role of intraluminal thrombus or atherosclerosis, this is a predominant feature of many AAAs (24) that was not present in most of the murine aneurysms we observed. However, it would be reasonable to assume that elastase concentration is related to AAA diameter, and very large aneurysms with slow flow may be more likely to develop intraluminal thrombus. Therefore, this model could potentially be used to evaluate such lesions in future studies. Furthermore, the B + E model also does not produce AAA rupture within 4 wk, but it is a good choice for understanding AAA expansion, which itself is correlated with rupture (7, 29). Finally, our 4DUS strain methodology also has limitations. Specifically, we assumed that strain is uniform around the circumference, the aorta is moving only in the radial direction throughout the cardiac cycle, and the aorta centerline is orthogonal to the ultrasound beam. Although these assumptions are not entirely true, all three are also used during analysis of M-mode ultrasound data, an approach that has been used clinically (18, 20). Improved in vivo imaging strategies capable of producing data where the full 3D strain tensor can be quantified will be needed to truly overcome these limitations.

In summary, the results from this study suggest that strain decreased, tortuosity increased, and elastin health declined in aneurysmal aortae. Furthermore, growing AAAs had increased surface area per length and peak wall stress compared with their stable counterparts. These findings support the use of B + E murine AAAs when rapidly expanding aneurysms are studied and demonstrate the value of high-frequency ultrasound capabilities. In addition to longer time course studies, future advances in imaging and computation tools and the deployment of commercial 4DUS systems may help to translate these findings. Although much work will need to be done in the future to provide clinical risk assessment alternatives to maximum AAA diameter, this research helps improve our understanding of the effects of BAPN, demonstrates the use of 4DUS in characterizing elastase-induced AAAs, and provides evidence for the utility of stress and strain quantification in experimental aneurysms.

GRANTS

This research was funded in part by American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant 14SDG18220010 (to C. J. Goergen) and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Grant DGE-1333468 (to A. G. Berman).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.J.R., A.G.B., and C.J.G. conceived and designed research; D.J.R. performed experiments; D.J.R. analyzed data; D.J.R., A.G.B., and C.J.G. interpreted results of experiments; D.J.R. prepared figures; D.J.R. drafted manuscript; D.J.R., A.G.B., and C.J.G. edited and revised manuscript; D.J.R., A.G.B., and C.J.G. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We graciously acknowledge Arvin Soepriatna for assistance with strain visualization and Drs. Sherry Voytik-Harbin and Charles Babbs for constructive feedback. Additionally, we acknowledge the assistance of the Purdue University Histology Research Laboratory, a core facility of the National Institutes of Health-funded Indiana Clinical & Translational Science Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anidjar S, Salzmann JL, Gentric D, Lagneau P, Camilleri JP, Michel JB. Elastase-induced experimental aneurysms in rats. Circulation 82: 973–981, 1990. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.82.3.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bath MF, Sidloff D, Saratzis A, Bown MJ; UK Aneurysm Growth Study Investigators . Impact of abdominal aortic aneurysm screening on quality of life. Br J Surg 105: 203–208, 2018. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhamidipati CM, Mehta GS, Lu G, Moehle CW, Barbery C, DiMusto PD, Laser A, Kron IL, Upchurch GR Jr, Ailawadi G. Development of a novel murine model of aortic aneurysms using peri-adventitial elastase. Surgery 152: 238–246, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bihari P, Shelke A, Nwe TH, Mularczyk M, Nelson K, Schmandra T, Knez P, Schmitz-Rixen T. Strain measurement of abdominal aortic aneurysm with real-time 3D ultrasound speckle tracking. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 45: 315–323, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyle JJ, Soepriatna A, Damen F, Rowe RA, Pless RB, Kovacs A, Goergen CJ, Thomopoulos S, Genin GM. Regularization-Free Strain Mapping in Three Dimensions, With Application to Cardiac Ultrasound. J Biomech Eng 141: 011010, 2019. doi: 10.1115/1.4041576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brekken R, Bang J, Ødegård A, Aasland J, Hernes TAN, Myhre HO. Strain estimation in abdominal aortic aneurysms from 2-D ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol 32: 33–42, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown PM, Zelt DT, Sobolev B. The risk of rupture in untreated aneurysms: the impact of size, gender, and expansion rate. J Vasc Surg 37: 280–284, 2003. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmo M, Colombo L, Bruno A, Corsi FRM, Roncoroni L, Cuttin MS, Radice F, Mussini E, Settembrini PG. Alteration of elastin, collagen and their cross-links in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 23: 543–549, 2002. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castle PE, Scheven UM, Crouch AC, Cao AA, Goergen CJ, Greve JM. Anatomical location, sex, and age influence murine arterial circumferential cyclic strain before and during dobutamine infusion. J Magn Reson Imaging 49: 69–80, 2019. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cebull H, Soepriatna A, Boyle J, Rothenberger S, Goergen C. Strain mapping from 4D ultrasound reveals complex remodeling in dissecting murine abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Biomech Eng 141: 060907, 2019. doi: 10.1115/1.4043075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaikof EL, Dalman RL, Eskandari MK, Jackson BM, Lee WA, Mansour MA, Mastracci TM, Mell M, Murad MH, Nguyen LL, Oderich GS, Patel MS, Schermerhorn ML, Starnes BW. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 67: 2–77.e2, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damen FW, Berman AG, Soepriatna AH, Ellis JM, Buttars SD, Aasa KL, Goergen CJ. High-frequency 4-dimensional ultrasound (4DUS): a reliable method for assessing murine cardiac function. Tomography 3: 180–187, 2017. doi: 10.18383/j.tom.2017.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derwich W, Wittek A, Pfister K, Nelson K, Bereiter-Hahn J, Fritzen CP, Blase C, Schmitz-Rixen T. High resolution strain analysis comparing aorta and abdominal aortic aneurysm with real time three dimensional speckle tracking ultrasound. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 51: 187–193, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2015.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farotto D, Segers P, Meuris B, Vander Sloten J, Famaey N. The role of biomechanics in aortic aneurysm management: requirements, open problems and future prospects. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 77: 295–307, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng M, Whitesall S, Zhang Y, Beibel M, D’Alecy L, DiPetrillo K. Validation of volume-pressure recording tail-cuff blood pressure measurements. Am J Hypertens 21: 1288–1291, 2008. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fillinger MF, Marra SP, Raghavan ML, Kennedy FE. Prediction of rupture risk in abdominal aortic aneurysm during observation: wall stress versus diameter. J Vasc Surg 37: 724–732, 2003. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fromageau J, Lerouge S, Maurice RL, Soulez G, Cloutier G. Noninvasive vascular ultrasound elastography applied to the characterization of experimental aneurysms and follow-up after endovascular repair. Phys Med Biol 53: 6475–6490, 2008. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/22/013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gamble G, Zorn J, Sanders G, MacMahon S, Sharpe N. Estimation of arterial stiffness, compliance, and distensibility from M-mode ultrasound measurements of the common carotid artery. Stroke 25: 11–16, 1994. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.25.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vande Geest JP, Sacks MS, Vorp DA. The effects of aneurysm on the biaxial mechanical behavior of human abdominal aorta. J Biomech 39: 1324–1334, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goergen CJ, Johnson BL, Greve JM, Taylor CA, Zarins CK. Increased anterior abdominal aortic wall motion: possible role in aneurysm pathogenesis and design of endovascular devices. J Endovasc Ther 14: 574–584, 2007. doi: 10.1177/152660280701400421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goergen CJ, Azuma J, Barr KN, Magdefessel L, Kallop DY, Gogineni A, Grewall A, Weimer RM, Connolly AJ, Dalman RL, Taylor CA, Tsao PS, Greve JM. Influences of aortic motion and curvature on vessel expansion in murine experimental aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 270–279, 2011. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.216481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo DC, Papke CL, He R, Milewicz DM. Pathogenesis of thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1085: 339–352, 2006. doi: 10.1196/annals.1383.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall AJ, Busse EF, McCarville DJ, Burgess JJ. Aortic wall tension as a predictive factor for abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture: improving the selection of patients for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Vasc Surg 14: 152–157, 2000. doi: 10.1007/s100169910027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hameed I, Isselbacher EM, Eagle KA. Aortic aneurysms. In: Comprehensive Cardiovascular Medicine in the Primary Care Setting, edited by Toth P and Cannon C. Totowa, NJ: Humana, 2011, p. 391–409. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humphrey JD, Holzapfel GA. Mechanics, mechanobiology, and modeling of human abdominal aorta and aneurysms. J Biomech 45: 805–814, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karatolios K, Wittek A, Nwe TH, Bihari P, Shelke A, Josef D, Schmitz-Rixen T, Geks J, Maisch B, Blase C, Moosdorf R, Vogt S. Method for aortic wall strain measurement with three-dimensional ultrasound speckle tracking and fitted finite element analysis. Ann Thorac Surg 96: 1664–1671, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kontopodis N, Tzirakis K, Ioannou CV. The obsolete maximum diameter criterion, the evident role of biomechanical (pressure) indices, the new role of hemodynamic (flow) indices, and the multi-modal approach to the rupture risk assessment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Vasc Dis 11: 78–83, 2018. doi: 10.3400/avd.ra.17-00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laser A, Lu G, Ghosh A, Roelofs K, McEvoy B, DiMusto P, Bhamidipati CM, Su G, Zhao Y, Lau CL, Ailawadi G, Eliason JL, Henke PK, Upchurch GR Jr. Differential gender- and species-specific formation of aneurysms using a novel method of inducing abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Surg Res 178: 1038–1045, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.04.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Ballard DJ, Jordan WD Jr, Blebea J, Littooy FN, Freischlag JA, Bandyk D, Rapp JH, Salam AA; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study #417 Investigators . Rupture rate of large abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients refusing or unfit for elective repair. JAMA 287: 2968–2972, 2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.22.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Z, Kleinstreuer C. A new wall stress equation for aneurysm-rupture prediction. Ann Biomed Eng 33: 209–213, 2005. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-8979-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu G, Su G, Davis JP, Schaheen B, Downs E, Roy RJ, Ailawadi G, Upchurch GR Jr. A novel chronic advanced stage abdominal aortic aneurysm murine model. J Vasc Surg 66: 232–242.e4, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.07.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maier A, Gee MW, Reeps C, Pongratz J, Eckstein HH, Wall WA. A comparison of diameter, wall stress, and rupture potential index for abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture risk prediction. Ann Biomed Eng 38: 3124–3134, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martufi G, Satriano A, Moore RD, Vorp DA, Di Martino ES. Local Quantification of Wall Thickness and Intraluminal Thrombus Offer Insight into the Mechanical Properties of the Aneurysmal Aorta. Ann Biomed Eng 43: 1759–1771, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parikh SA, Gomez R, Thirugnanasambandam M, Chauhan SS, De Oliveira V, Muluk SC, Eskandari MK, Finol EA. Decision tree based classification of abdominal aortic aneurysms using geometry quantification measures. Ann Biomed Eng 46: 2135–2147, 2018. [Erratum in: Ann Biomed Eng 47: 332, 2019.] doi: 10.1007/s10439-018-02116-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips EH, Yrineo AA, Schroeder HD, Wilson KE, Cheng JX, Goergen CJ. Morphological and biomechanical differences in the elastase and AngII apoE(−/−) rodent models of abdominal aortic aneurysms. BioMed Res Int 2015: 1–12, 2015. doi: 10.1155/2015/413189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polzer S, Gasser TC. Biomechanical rupture risk assessment of abdominal aortic aneurysms based on a novel probabilistic rupture risk index. J R Soc Interface 12: 20150852, 2015. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2015.0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polzer S, Gasser TC, Bursa J, Staffa R, Vlachovsky R, Man V, Skacel P. Importance of material model in wall stress prediction in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Med Eng Phys 35: 1282–1289, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pyo R, Lee JK, Shipley JM, Curci JA, Mao D, Ziporin SJ, Ennis TL, Shapiro SD, Senior RM, Thompson RW. Targeted gene disruption of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (gelatinase B) suppresses development of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest 105: 1641–1649, 2000. doi: 10.1172/JCI8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raut SS, Chandra S, Shum J, Finol EA. The role of geometric and biomechanical factors in abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture risk assessment. Ann Biomed Eng 41: 1459–1477, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0786-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakalihasan N, Heyeres A, Nusgens BV, Limet R, Lapière CM. Modifications of the extracellular matrix of aneurysmal abdominal aortas as a function of their size. Eur J Vasc Surg 7: 633–637, 1993. doi: 10.1016/S0950-821X(05)80708-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith-Mungo LI, Kagan HM. Lysyl oxidase: properties, regulation and multiple functions in biology. Matrix Biol 16: 387–398, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0945-053X(98)90012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soepriatna AH, Damen FW, Vlachos PP, Goergen CJ. Cardiac and respiratory-gated volumetric murine ultrasound. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 34: 713–724, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s10554-017-1283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenhalgh RM, Brown LC, Powell JT, Thompson SG, Epstein D, Sculpher MJ; United Kingdom EVAR Trial Investigators . Endovascular versus open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. N Engl J Med 362: 1863–1871, 2010. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Updegrove A, Wilson NM, Merkow J, Lan H, Marsden AL, Shadden SC. SimVascular: an open source pipeline for cardiovascular simulation. Ann Biomed Eng 45: 525–541, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1762-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Disseldorp EM, Petterson NJ, Rutten MC, van de Vosse FN, van Sambeek MR, Lopata RG. Patient specific wall stress analysis and mechanical characterization of abdominal aortic aneurysms using 4D ultrasound. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 52: 635–642, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2016.07.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y, Thatcher SE, Cassis LA. Measuring Blood Pressure Using a Noninvasive Tail Cuff Method in Mice. In: The Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System, edited by Thatcher SE. New York: Humana, 2017, p. 69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yrineo AA, Adelsperger AR, Durkes AC, Distasi MR, Voytik-Harbin SL, Murphy MP, Goergen CJ. Murine ultrasound-guided transabdominal para-aortic injections of self-assembling type I collagen oligomers. J Control Release 249: 53–62, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]