Abstract

Dientamoeba fragilis is a trichomonad parasite of the human intestine that is found worldwide. However, the biological cycle and transmission of this parasite have yet to be elucidated. Although its pathogenic capacity has been questioned, there is increasing evidence that clinical manifestations vary greatly. Different therapeutic options with antiparasitic drugs are currently available; however, very few studies have compared the effectiveness of these drugs. In the present longitudinal study, we evaluate 13,983 copro-parasitological studies using light microscopy of stools, during 2013–2015, in Terrassa, Barcelona (Spain). A total of 1150 (8.2%) presented D. fragilis. Of these, 739 episodes were finally analyzed: those that involved a follow-up parasitology test up to 3 months later, corresponding to 586 patients with gastrointestinal symptoms (53% under 15 years of age). Coinfection by Blastocystis hominis was present in 33.6% of the subjects. Our aim was to compare therapeutic responses to different antiparasitic drugs and the factors associated with the persistence of D. fragilis post-treatment. Gender, age, and other intestinal parasitic coinfections were not associated with parasite persistence following treatment. Metronidazole was the therapeutic option in most cases, followed by paromomycin: 65.4% and 17.5% respectively. Paromomycin was found to be more effective at eradicating parasitic infection than metronidazole (81.8% vs. 65.4%; p = 0.007), except in children under six years of age (p = 0.538). Although Dientamoeba fragilis mainly produces mild clinical manifestations, the high burden of infection means we require better understanding of its epidemiological cycle and pathogenicity, as well as adequate therapeutic guidelines in order to adapt medical care and policies to respond to this health problem.

Keywords: Dientamoeba fragilis, Metronidazole, Paromomycin, Therapy, Clinical efficacy, Parasites

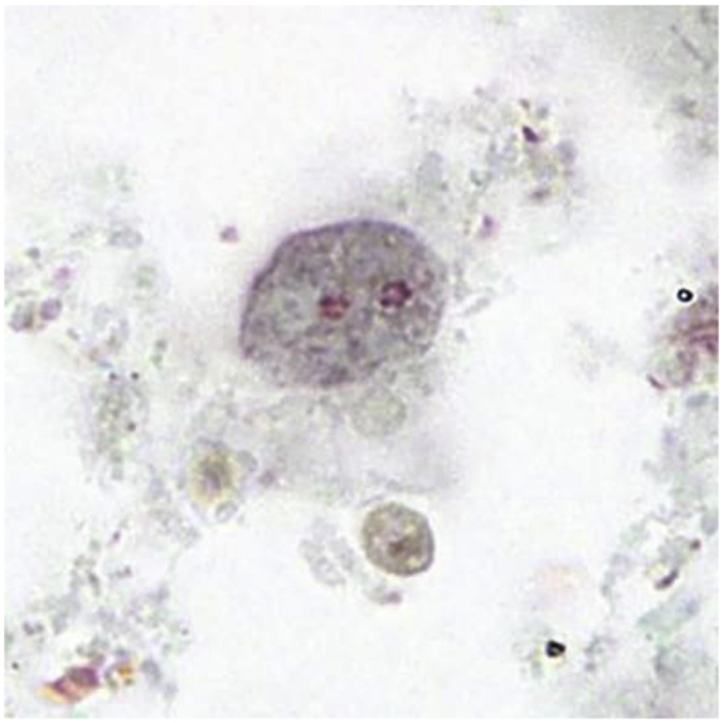

Graphical abstract

Figure: Binucleate form of a trophozoite of D. fragilis, stained with trichrome Image courtesy of DPDx (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Highlights

-

•

A high prevalence of D. fragilis was detected in individuals with gastrointestinal symptoms.

-

•

Paromomycin was more effective than metronidazole in the eradication of D. fragilis.

-

•

Persistence of infection by D. fragilis was not associated with age, gender or other parasitic coinfections.

1. Introduction

Dientamoeba fragilis is a non-flagellated trichomonad protozoan parasite which inhabits the human intestine and is found worldwide (Barratt et al., 2011). The prevalence of D. fragilis is very heterogeneous, depending on the geographical region and the diagnostic method used (Barratt et al., 2011; van Gestel et al., 2018), with highest levels of prevalence observed in high-income countries (Stark et al., 2016). In Europe, prevalence varies from 1.6% to 83% (González-Moreno et al., 2011; Preiss et al., 1990); in Spain, from 0.4% to 24% in children (Belda Rustarazo et al., 2008) and from 2% to 9% in adults (González-Moreno et al., 2011; Fernández-Suarez et al., 2015).

The transmission and biological cycle of D. fragilis have not been reported, although fecal–oral transmission is most probable (Munasinghe et al., 2013; Stark et al., 2016). In recent years, a cystic form of infection has been reported, which may explain how D. fragilis remains in the environment and could be a vehicle that mediates transmission between hosts (Stark et al., 2014).

In relation to the pathogenic capacity of D. fragilis, animal studies have reported the proposals of Kock (Munasinghe et al., 2013); while in humans an association has been detected between gastrointestinal symptoms, the presence of the parasite and improvements in clinical manifestations post-treatment (Stark et al., 2005; Banik et al., 2011; Barratt et al., 2011; Nagata et al., 2012). Meanwhile, some authors have not found clinical improvement after eradication of the parasite in feces (Johnson et al., 2004; Röser et al., 2014; Wong et al., 2018).

Clinical presentations vary from the absence of symptoms to gastrointestinal symptomatology mainly of abdominal pain and diarrhea (Miguel et al., 2018; Damien Stark et al., 2010). Some studies have related the clinical presentation of D. fragilis with the irritable bowel syndrome (Yakoob et al., 2010) and with eosinophilic colitis (Cuffari et al., 1998).

The principal diagnostic techniques used for the diagnosis of D. fragilis are light microscopy and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of DNA from stools together with subsequent sequencing. PCR has been reported to have the higher sensitivity of these two methods (van Gestel et al., 2018). However, the correlation between PCR and clinical signs and symptoms seems to be lower than for light microscopy (Stark et al., 2010a, Stark et al., 2010b).

Many therapeutic options for the treatment of infection by D. fragilis have been adopted in symptomatic cases. The main groups of antiparasitic drugs include: the nitroimidazoles, among which metronidazole and also secnidazole, tinidazole and ornidazole are of note (Banik et al., 2011; Girginkardeşler et al., 2003; Kurt et al., 2008; Röser et al., 2014; Stark et al., 2014); aminoglycosides, with paromomycin (Vandenberg et al., 2007; van Hellemond et al., 2012); hydroxyquinolines, such as iodoquinol and clioquinol (Spencer, 1979; Millet et al., 1983; Stark et al., 2010a, Stark et al., 2010b; Schure et al., 2013) and tetracyclines (Preiss et al., 1990). In vitro studies of antiparasitic drugs do not seem to correspond with clinical responses observed in humans (Chan et al., 1994; Nagata et al., 2012).

Eradication rates in studies of treatment effectiveness vary greatly. In addition, the percentage of spontaneous cures without treatment are elevated (almost 50%) (Stark et al., 2016). At a European level, eradication rates among children range from 49% to 100%, and from 57% to 98% in adults (van Gestel et al., 2018). Most studies of D. fragilis treatment are retrospective and have a small sample sizes (Nagata et al., 2012; Röser et al., 2014; van Gestel et al., 2018). Due to the scarcity of randomized comparative studies, there is little evidence indicating which adult or pediatric cases of D. fragilis should be treated, or what the treatment of choice and best therapeutic schedule are (Stark et al., 2016).

The aim of the present study was therefore to evaluate therapeutic responses to different antiparasitic drugs and to determine the factors which may be associated with persistence of D. fragilis infection.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study population

We performed a longitudinal study from 2013 to 2015 in the areas of the western Vallès Occidental and the Baix Llobregat, in the province of Barcelona, Spain. The study population included individuals who attended any of the nine primary health care centers or the Mutua de Terrassa hospital, and who underwent a parasitological stool study in response to gastrointestinal symptomatology. Of these individuals, those with a positive test for D. fragilis were selected for the study. Data were obtained from the results of the corresponding laboratories.

2.2. Data

Three stool samples per patient were collected on alternate days, in stool containers with sodium acetate–acetic acid–formaldehyde (SAF). They were processed by the centrifugal sedimentation technique and examined under a light microscope (Martín-Rabadán et al., 2010). We defined an episode as an infection by D. fragilis when an individual presented D. fragilis in at least one of the three samples. The study included episodes that were not treated with antiparasitic drugs as well as those that were followed by a parasitology test at some point up to three months after diagnosis. Persistence of D. fragilis infection was defined when the follow-up parasitology test was still positive for D. fragilis.

Sociodemographic data (age and gender) of the patients were collected from the electronic clinical history as well as their diagnostic data (parasitology results in stool samples, coinfections with other parasites, time to follow-up parasitology test) and the treatment administered (antiparasitic drug). In agreement with the 2017 treatment guidelines issued by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC-Centers for Disease Control, 2017), metronidazole (500–750 mg) was administered orally three times daily to adults and 30 mg/kg/day to children for 10 days; while oral paromomycin (25–35 mg/kg/day) was divided into three doses for 7 days in adults and children. Therapeutic failure or persistence was considered when D. fragilis was detected in the post-treatment test, while a negative test indicated eradication.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables were described using frequencies and percentages; quantitative variables using medians, means, and the interquartile range (IQR).

The chi-square or Fisher's exact test was used to assess the association between categorical variables and persistence; in the case of quantitative variables, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. In addition, the generalized estimation equation was used to determine the independent factors associated with persistence, and an exchangeable correlation structure was assumed for repeated episodes in a subject. The variance-covariance matrix of the regression parameter coefficients was estimated by a robust sandwich variance estimator. The type I error was set at 5%. The analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

2.4. Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethical Research Committee of the Fundació Docència I Recerca Mútua Terrassa, March 30, 2016 (Acta 03/2016).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive results

A total of 13,983 three-stool-sample tests were studied from the three-year period. D. fragilis was identified in 1150 episodes of infection (8.2%), and of these, 739 (64.3%) underwent a post-treatment parasitology test within the following three months and were included in the analysis. These 739 episodes of infection corresponded to 586 patients, 152 (25.9%) of whom presented more than one episode during the study period.

Women made up 52.6% (308/586) of the individuals studied, and the mean age of the study subjects was 12 (IQR: 6–46). Concerning coinfection with other intestinal parasites, Blastocystis hominis was observed in 33.6% (248/739) followed by Giardia lamblia in 4.2% (31/739). Metronidazole was administered in 65.4% (483/739) of the episodes of infection, while paromomycin was given in 17.5% (129/739), and 8.9% (66/739) received no treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients and D. fragilis episodes, coinfection and treatment.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Individuals characteristics (n = 586) | |

| Gender: Female | 308 (52.6%) |

| Age (year) | 12 (IQR:6; 46) |

| Episodes >1 | 152 (25.9%) |

| Coinfection (episodes n = 739) | |

| Blastocystis hominis | 248 (33,6%) |

| Giardia Lamblia | 31 (4.2%) |

| Enterobius vermicularis | 4 (0.5%) |

| Treatment (episodes n = 739) | |

| Metronidazole | 483 (65.4%) |

| Paromomycin | 129 (17.5%) |

| Others | 61 (8.3%) |

| Non-treatment | 66 (8.9%) |

| Persistence (episodes n = 739) | 250 (33.8%) |

IQR: interquartile range.

Some individuals presented several episodes of infection by D. fragilis during the study period: 21.2% of women and 16.9% of men, with no significant differences (p = 0.181). By age groups, the percentages were: 15.9% in individuals below 6 years of age, 21.9% in those aged from 6 to 14, and 18.9% in individuals aged 15 or over (p = 0.399).

3.2. Analysis of factors associated with the persistence of D. fragilis

D. fragilis persisted in 33.8% (250/739) of the episodes. Neither gender (p = 0.419) nor patient age (p = 0.107) was associated with persistence, and there was no statistical association between persistence and parasitic coinfection. However, we did observe that the longer the time between the first diagnosis and the post-treatment parasitology test, the greater the proportion of positive cases for D. fragilis: 27.4% in the first month, 34.2% in the second month and 40.4% in the third month (p = 0.012) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study variables related to persistence of D. fragilis.

| Variables | Persistence of D. fragilis | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.419 | |

| Female | 122/376 (32.4%) | |

| Male |

128/363 (35.3%) |

|

| Age (years) | 0.107 | |

| ≤5 | 43/155 (27.7%) | |

| 6–14 | 92/242 (38.0%) | |

| ≥15 | 115/342 (33.6%) | |

| Coinfection | ||

| Blastocystis hominis | 0.182 | |

| Yes | 92/248 (37.1%) | |

| No | 158/491 (32.2%) | |

| Giardia lamblia | 0.176 | |

| Yes | 7/31 (22.6%) | |

| No | 243/703 (34.3%) | |

| Enterobius vermicularis | 0.584 | |

| Yes | 1/4 (25.0%) | |

| No |

249/735 (33.9%) |

|

| Time until post-treatment control test (days) | 0.012 | |

| 0–30 | 49/179 (27.4%) | |

| 31–60 | 138/404 (34.2%) | |

| 61–90 | 63/156 (40.4%) | |

Our multivariate analysis to evaluate the possible factors associated with the eradication of D. fragilis included age, gender, treatment, coinfection with Blastocystis hominis and time from diagnosis to the follow-up parasitology test. Eradication was only associated with antiparasitic treatment in comparison with non-treated subjects, showing a greater probability of eradication with paromomycin (OR = 5.64, 95%CI: 2.51, 12.6), followed by metronidazole, (OR = 1.84, 95%CI: 1.10, 3.08), and other treatments (OR = 1.74, 95%CI: 0.90, 3.35) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with the eradication of D. fragilis.

| P- value | OR [95%CI] | |

|---|---|---|

|

Women |

0.834 |

1.04 [0.72; 1.46] |

| Age (years)a | ||

| ≤5 | 0.873 | 1.04 [0.65; 1.66] |

| 6-14 |

0.230 |

0.79 [0.54; 1.16] |

| Treatmenta | ||

| Paromomiycin | <0.001 | 5.64 [2.51; 12.6] |

| Metronidazole | 0.002 | 1.84 [1.10; 3.08] |

| Others |

0.098 |

1.74 [0.90; 3.35] |

|

Coinfection byBlastocystis hominis |

0.155 |

1.30 [0.91; 1.86] |

| Time until post-treatment control test (days)a | ||

| 0–30 | 0.091 | 1.61 [0.93; 2.78] |

| 31–60 | 0.639 | 1.11 [0.72; 1.68] |

Basal category; Age: ≥15, Treatment: Non-treatment, Time until test: 61–90 days.

3.3. Study of antiparasitic drugs

With regard to the therapy used, we observed that eradication was achieved in 65.4% of patients treated with metronidazole and 81.8% of those treated with paromomycin, both higher than for non-treated patients (48.5%) (p = 0.007 and p < 0.001, respectively). These eradication rates did not change when combined treatments were administered, as observed with the combination metronidazole plus mebendazole compared to metronidazole (70.8% versus 65.4% p = 0.378) or with paromomycin plus mebendazole compared to paromomycin (87.5% versus 81.8%, p = 0.580) (Table 4). Overall, paromomycin cured patients in 16.6% (95%CI: 7.9%, 25.1%; p < 0.001) more cases than metronidazole did. On analyzing the treatments by age group, this difference was not observed in individuals aged under six (Table 5).

Table 4.

Eradication rates of D. fragilis according to antiparasitic drug administered.

| Treatment | % |

|---|---|

| Metronidazole alone | 300/459 (65.4%) |

| Metronidazole + Mebendazole | 17/24 (70.8%) |

| Metronidazole (total) | 317/483 (65.6%) |

| Paromomycin alone | 99/121 (81.8%) |

| Paromomycin + Mebendazole | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Paromomycin (total) | 106/129 (82.2%) |

| Paromomycin + Metronidazole | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Tetracycline | 8/11 (72.7%) |

| Secnidazole | 0/2 (0%) |

| Tinidazole | 1/2 (50%) |

| Mebendazole | 9/20 (45%) |

| Clotrimoxazol | 3/6 (50%) |

| Non-treatment | 32/66 (48.5%) |

Table 5.

Percentage of D. fragilis eradication based on treatment and age group.

| Treatment | Age group |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤5 years | 6–14years | ≥15 years | |

| Metronidazole | 65/86 (75.6%) | 79/136 (58.1%) | 154/232 (66.5%) |

| Paromomycin | 28/39 (71.8%) | 37/44 (84.1%)* | 36/40 (90.0%)** |

| Others | 11/16 (68.8%) | 24/38 (63.2%) | 27/47 (57.4%) |

| Non-treatment | 8/14 (57.1%) | 101/24 (41.7%) | 10/23 (43.5%) |

| P-value | 0.538 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

Significant differences between metronidazole and paromomycin *(p = 0.007) **(p = 0.011).

When we reviewed the metronidazole treatment regimen used in each individual, we observed that in those who received the recommended dose and duration of treatment the eradication rate increased to 73%. Nonetheless, paromomycin continued to present a higher percentage of cure (p = 0.013). With metronidazole schedules of less than 10 days, the eradication rate was 64.5% (p = 0.199), considering only doses less than 500 mg/8 h, it was 71.8% (p = 0.97), and if both the dose and treatment duration were less than those recommended, the rate of eradication rate was 45.6% (p < 0.001) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Test results post treatment with metronidazole according to dose used.

| Treatment | Negative for D. fragilis | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metronidazole | Dose and duration recommendeda | 157/215 (73.0%) | |

| Duration<10 days | 71/110 (64.5%) | p = 0.199 | |

| Underdosage | 28/39 (71.8%) | p = 0.97 | |

| Duration<10 days and underdosage | 36/79 (45.6%) | p < 0,0001 |

CDC recommendation.

4. Discussion

The results of the present study show an elevated rate of D. fragilis infection in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms (approximately 8%) and a high rate of persistence of D. fragilis (33%) after having received treatment. Concerning treatment, we found that a broad range of antiparasitic drugs and schedules were used, with metronidazole and paromomycin the most commonly administered. Treatment with paromomycin presented higher rates of eradication of D. fragilis than metronidazole at all ages, except in subjects under six years of age.

International treatment guidelines (CDC-Centers for Disease Control, 2017) recommend metronidazole and paromomycin as first-line treatment together with iodoquinol (not marketed in our country). To date, studies of the effectiveness of treatment of D. fragilis have been small (most include fewer than 100 subjects), they tend to study a heterogeneous population (studies in children, children and adults and adults), and generally include retrospective case series (CDC-Centers for Disease Control, 2017; van Gestel et al., 2018). The eradication rates reported vary greatly, with elevated rates of therapeutic failure (up to 80%) (Nagata et al., 2012; Stark et al., 2014; van Gestel et al., 2018). With regard to the antiparasitic drugs used, metronidazole has been studied more frequently, with eradication rates ranging from 52% to 85% (Banik et al., 2011; Engsbro et al., 2012; Kurt et al., 2008; Röser et al., 2014; Schure et al., 2013; Damien Stark et al., 2010; van Hellemond et al., 2012). To the best of our knowledge, only one randomized, double-blind clinical trial with a placebo has been carried out in a pediatric population, and the results showed that metronidazole was no more effective than the placebo (Röser et al., 2014). Another randomized clinical study with a single dose of ornidazole showed this drug to be more effective than metronidazole (Kurt et al., 2008).

In relation to paromomycin, eradication rates from 80% to 100% have been reported (Simon et al., 1967; Vandenberg et al., 2006, 2007; Stark et al., 2010a, Stark et al., 2010b; van Hellemond et al., 2012) in retrospective case series. Our setting involved patients presenting gastrointestinal symptoms in the absence of other causes and always attributable to D. fragilis. The most frequent therapeutic option was metronidazole. The results of our study suggest a clear advantage of paromomycin in the treatment of infection by D. fragilis, which is consistent with the results of van Hellemond et al. (2012).

In the subgroup of children under six years of age, in the bivariate analysis, we observed that paromomycin presented lower rates of eradication than in subjects aged over six and was no more effective than metronidazole. These lower rates could be due to the different pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of paromomycin in small children. Some studies have reported possible underdosing when calculating the dose according to weight in pediatric populations and suggest that the dose be calculated based on body surface (Lack and Stuart-Taylor, 1997; Añez et al., 2016).

The schedules of dose and length of treatment are very heterogeneous in studies of the effectiveness of metronidazole in the treatment of D. fragilis (Banik et al., 2011; van Gestel et al., 2018). In the study by Banik et al. (2011), when they analyzed therapeutic failure, it was not associated with either the dose or treatment duration. In contrast, in our study, both the dose and treatment time were found to be associated with greater therapeutic failure, which was only significant when the two were combined. Thus, the dose showing the best results in our study was that of metronidazole 500–750 mg or 30 mg/kg/day in children orally three times daily for ten days, which is the schedule recommended by international guidelines (CDC-Centers for Disease Control, 2017).

Concerning coinfection with other parasites, we did not observe any relationship between the presence of other parasites and a worse response to treatment. In our case, neither was the addition of mebendazole to the treatment used associated with higher eradication rates, in contrast to some previous studies (Boga et al., 2016). Coinfection by B. hominis was the most frequently observed (33.6%), suggesting that it could have a similar epidemiology. Meanwhile, numerous studies have linked Enterobius vermicularis with the transmission of D. fragilis (Johnson et al., 2004; Girginkardeşler et al., 2008; Röser et al., 2014; Ögren et al., 2015). In our study, infection by E. vermicularis was low (0.5%), although no diagnostic test of choice was used for its diagnosis (Graham technique). The small number of individuals treated with mebendazole combined with paromomycin or metronidazole does not allow us to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of these treatment options.

The apparently high rate of eradication of the parasite without treatment may be explained by intermittent excretion of trophozoites in stools (Cartwright, 1999) a possible reduction in parasitic load not detectable by light microscopy, spontaneous eradication of the parasite (Röser et al., 2014) and/or a limitation of the diagnostic technique (D. Stark et al., 2010).

We also observed that one-fourth of the patients presented more than one infectious episode by D. fragilis and that the longer the time until the next parasitology test, the higher the rate of persistence. This fact is consistent with the results of the study by Röser et al. (2014). This phenomenon may have 2 explanations: the first is that eradication is not achieved, but instead there is a reduction, albeit not detectable by light microscopy, in parasitic load, and the longer the delay in the test the higher the probability of detecting the parasite; and the second is the possibility of new reinfection. Röser et al. (2014) reported similar results with the use of molecular biology (with high sensitivity for low parasitic loads) suggesting that the mechanism of reinfection was predominant.

The present study had a longitudinal observational design, limiting the generalizations that are valid from the results of the study of association and not causality. Clinical trials are needed to compare different antiparasitic drugs with a placebo to determine the real effectiveness of treatment and to determine the best therapeutic options to be implemented. The use of microscopic techniques (and not molecular biology) may have reduced the sensitivity, but we believe that this did not affect the overall value of the results, and the prevalence of D. fragilis found was in agreement with values described in other European countries (Cacciò, 2018).

The pathogenic capacity of infection by D. fragilis and its clinical manifestations vary widely, from asymptomatic cases or those with mild symptoms to chronic symptoms (Damien Stark et al., 2016; Miguel et al., 2018). Despite the considerable variability in symptomatology, with mainly asymptomatic or mild clinical manifestations, its high prevalence can generate a considerable disease load, leading to the use of many healthcare resources. In this sense, to date, Dientamoebiasis has been neglected (Garcia, 2016; Stark et al., 2016). In turn, the need to establish specific healthcare policies to tackle this reality is increasingly evident.

To the best of our knowledge, the sample in our study is one of the largest used to evaluate subjects with D. fragilis and the therapeutic response to different antiparasitic drugs. We show higher rates of eradication with paromomycin than with metronidazole. However, it is still necessary to develop new studies that evaluate the clinical–parasitology correlation and the efficacy of the different therapeutic options for the treatment of infection by D. fragilis.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out thanks to a grant from the Departament de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya, del 2017 dins del Pla Estratègic de Recerca i Innovació en Salut (PERIS) 2016–2020: modalitat intesificació professionals de la salut expedient SLT006/17/14.

References

- Añez A., Moscoso M., Garnica C., Ascaso C. Evaluation of the paediatric dose of chloroquine in the treatment of Plasmodium vivax malaria. Malar. J. 2016;15:371. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1420-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banik G.R., Barratt J.L.N., Marriott D., Harkness J., Ellis J.T., Stark D. A case-controlled study of Dientamoeba fragilis infections in children. Parasitology. 2011;138:819–823. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011000448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt J.L.N., Harkness J., Marriott D., Ellis J.T., Stark D. A review of Dientamoeba fragilis carriage in humans: several reasons why this organism should be considered in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal illness. Gut Microb. 2011;2:3–12. doi: 10.4161/gmic.2.1.14755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belda Rustarazo S., Morales Suárez-Varela M., Gracia Antequera M., Esteban Sanchis J.G. Enteroparasitosis en población escolar de Valencia. Atención Primaria. 2008;40:641–642. doi: 10.1016/S0212-6567(08)75701-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boga J.A., Rojo S., Fernández J., Rodríguez M., Iglesias C., Martínez-Camblor P., Vázquez F., Rodríguez-Guardado A. Is the treatment of Enterobius vermicularis co-infection necessary to eradicate Dientamoeba fragilis infection? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016;49:59–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciò S.M. Molecular epidemiology of Dientamoeba fragilis. Acta Trop. 2018;184:73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright C.P. Utility of multiple-stool-specimen ova and parasite examinations in a high-prevalence setting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999;37:2408–2411. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2408-2411.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC-Centers for Disease Control . 2017. CDC - Dientamoeba Fragilis - Resources for Health Professionals [WWW Document]https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/dientamoeba/health_professionals/index.html C.-C. for D.C. URL. accessed 7.25.19. [Google Scholar]

- Chan F.T., Guan M.X., Mackenzie A.M., Diaz-Mitoma F. Susceptibility testing of Dientamoeba fragilis ATCC 30948 with iodoquinol, paromomycin, tetracycline, and metronidazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1157–1160. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.5.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuffari C., Oligny L., Seidman E.G. Dientamoeba fragilis masquerading as allergic colitis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1998;26:16–20. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199801000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engsbro A.L., Stensvold C.R., Nielsen H.V., Bytzer P. Treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012;87:1046–1052. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Suarez J., Rodríguez-Guardado A., Boga Ribeiro J.A., Iglesias C., Rojo S., Fernández- Domínguez J. 25th Congress ECCMID. 2015. n.d. Diagnosis and epidemiological features of Dientamoeba fragilis infection. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia L.S. Dientamoeba fragilis, one of the neglected intestinal Protozoa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016;54:2243–2250. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00400-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girginkardeşler N., Coşkun S., Cüneyt Balcioğlu I., Ertan P., Ok U.Z. Dientamoeba fragilis, a neglected cause of diarrhea, successfully treated with secnidazole. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2003;9:110–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girginkardeşler N., Kurt O., Kilimcioğlu A.A., Ok U.Z. Transmission of Dientamoeba fragilis: evaluation of the role of Enterobius vermicularis. Parasitol. Int. 2008;57:72–75. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Moreno O., Domingo L., Teixidor J., Gracenea M. Prevalence and associated factors of intestinal parasitisation: a cross-sectional study among outpatients with gastrointestinal symptoms in Catalonia, Spain. Parasitol. Res. 2011;108:87–93. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E.H., Windsor J.J., Clark C.G. Emerging from obscurity: biological, clinical, and diagnostic aspects of Dientamoeba fragilis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004;17:553–570. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.3.553-570.2004. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurt ö., Girginkardeşler N., Balcioğlu I.C., Özbilgin A., Ok ü.Z. A comparison of metronidazole and single-dose ornidazole for the treatment of dientamoebiasis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008;14:601–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lack J.A., Stuart-Taylor M.E. Calculation of drug dosage and body surface area of children. Br. J. Anaesth. 1997;78:601–605. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Rabadán P., Martínez-Ruiz R., Cuadros J., Cañavate C. El laboratorio de microbiología ante las enfermedades parasitarias importadas. Enfermedades Infecc. Microbiol. Clínica. 2010;28:719–725. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel L., Salvador F., Sulleiro E., Sánchez-Montalvá A., Molina-Morant D., López I., Molina I. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of patients with Dientamoeba fragilis infection. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018;99:1170–1173. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet V., Spencer M.J., Chapin M., Stewart M., Yatabe J.A., Brewer T., Garcia L.S. Dientamoeba fragilis, a protozoan parasite in adult members of a semicommunal group. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1983;28:335–339. doi: 10.1007/BF01324950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munasinghe V.S., Vella N.G.F., Ellis J.T., Windsor P.A., Stark D. Cyst formation and faecal-oral transmission of Dientamoeba fragilis the missing link in the life cycle of an emerging pathogen. Int. J. Parasitol. 2013;43:879–883. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata N., Marriott D., Harkness J., Ellis J.T., Stark D. Current treatment options for Dientamoeba fragilis infections. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2012;2:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ögren J., Dienus O., Löfgren S., Einemo I.-M., Iveroth P., Matussek A. Dientamoeba fragilis prevalence coincides with gastrointestinal symptoms in children less than 11 years old in Sweden. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10096-015-2442-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preiss U., Ockert G., Brömme S., Otto A. Dientamoeba fragilis infection, a cause of gastrointestinal symptoms in childhood. Klin. Pädiatr. 1990;202:120–123. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1025503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röser D., Simonsen J., Stensvold C.R., Olsen K.E.P., Bytzer P., Nielsen H.V., Mølbak K. Metronidazole therapy for treating dientamoebiasis in children is not associated with better clinical outcomes: a randomized, double-blinded and placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2014;58:1692–1699. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schure J.M.A.T., de Vries M., Weel J.F.L., van Roon E.N., Faber T.E. Symptoms and treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis infection in children, a retrospective study. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2013;32:e148–150. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31827f4c20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M., Shookhoff H.B., Terner H., Weingarten B., Parker J.G. Paromomycin in the treatment of intestinal amebiasis; a short course of therapy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1967;48:504–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer M.J. Dientamoeba fragilis: an intestinal pathogen in children? Am. J. Dis. Child. 1979;133:390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark D., Barratt J., Chan D., Ellis J.T. Dientamoeba fragilis, the neglected trichomonad of the human bowel. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016;29:553–580. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00076-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark Damien, Barratt J., Ellis J., Roberts T., Marriott D., Harkness J. A review of the clinical presentation of dientamoebiasis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010;82:614–619. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark D., Barratt J., Roberts T., Marriott D., Harkness J., Ellis J. Comparison of microscopy, two xenic culture techniques, conventional and real-time PCR for the detection of Dientamoeba fragilis in clinical stool samples. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;29:411–416. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-0876-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark D., Barratt J.L.N., Roberts T., Marriott D., Harkness J.T., Ellis J. Activity of benzimidazoles against Dientamoeba fragilis (Trichomonadida, Monocercomonadidae) in vitro and correlation of beta-tubulin sequences as an indicator of resistance. Parasite Paris Fr. 2014;21:41. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2014043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark D., Beebe N., Marriott D., Ellis J., Harkness J. Prospective study of the prevalence, genotyping, and clinical relevance of Dientamoeba fragilis infections in an Australian population. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:2718–2723. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2718-2723.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gestel R., Kusters J.G., Monkelbaan J.F. A clinical guideline on Dientamoeba fragilis infections. Parasitology. 2018:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0031182018001385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hellemond J.J., Molhoek N., Koelewijn R., Wismans P.J., van Genderen P.J.J. Is paromomycin the drug of choice for eradication of Dientamoeba fragilis in adults? Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2012;2:162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg O., Peek R., Souayah H., Dediste A., Buset M., Scheen R., Retore P., Zissis G., van Gool T. Clinical and microbiological features of dientamoebiasis in patients suspected of suffering from a parasitic gastrointestinal illness: a comparison of Dientamoeba fragilis and Giardia lamblia infections. Int. J. Infect. Dis. IJID Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Infect. Dis. 2006;10:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg O., Souayah H., Mouchet F., Dediste A., van Gool T. Treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis infection with paromomycin. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2007;26:88–90. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000247139.89191.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Z.-W., Faulder K., Robinson J.L. Does Dientamoeba fragilis cause diarrhea? A systematic review. Parasitol. Res. 2018;117:971–980. doi: 10.1007/s00436-018-5771-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakoob J., Jafri W., Beg M.A., Abbas Z., Naz S., Islam M., Khan R. Blastocystis hominis and Dientamoeba fragilis in patients fulfilling irritable bowel syndrome criteria. Parasitol. Res. 2010;107:679–684. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1918-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]