Abstract

Introduction

The Consortium for the early identification of Alzheimer's disease–Quebec (CIMA-Q) created a research infrastructure to recruit, characterize, and track disease progression in individuals at risk of dementia.

Methods

CIMA-Q established standardized clinical, neuropsychological, neuroimaging, blood (plasma, serum, RNA, genomic DNA), cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and cerebrospinal fluid collection protocols. These data and biological materials are available to the research community.

Results

In phase 1, 115 persons with subjective cognitive decline, 88 with mild cognitive impairment, 31 with early probable Alzheimer's disease, and 56 older adults with no worries nor impairments received detailed clinical and cognitive evaluations as well as blood and peripheral blood mononuclear cells collections. Among them, 142 underwent magnetic resonance imaging, 29 a 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography, and 60 a lumbar puncture.

Discussion

CIMA-Q provides procedures and resources to identify early biomarkers and novel therapeutic targets, and holds promise for detecting cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease.

Keywords: Consortium for the early identification of Alzheimer's disease-Quebec, CIMA-Q, Clinical cohort, Alzheimer's disease, Mild cognitive impairment, Subjective cognitive decline, Biomarker, Early diagnosis, Cryopreserved PBMNC

Highlights

-

•

Well-ascertained cohort of 290 community-dwelling elderly individuals in Quebec.

-

•

Large number of individuals with subjective cognitive decline studied longitudinally.

-

•

Clinical, neuropsychology, neuroimaging, and biomaterials available for Alzheimer's disease studies.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is currently diagnosed at the dementia stage, when the brain has already suffered severe damage and when symptoms impact the individual's autonomy. This late diagnosis poses major challenges in understanding the cause and developing disease-modifying therapies. Efforts devoted toward implementing large integrative studies are needed to provide high impact research that fills these knowledge gaps. It is generally agreed that, to make significant discoveries, scientists require access to sizable cohorts, databases, and high-quality biological materials from well-characterized patients at all stages of the disease, including the preclinical/prodromal phases. Ideally, such studies should allow data to be pooled and compared with other similarly harmonized national and international cohorts.

It is now well recognized that persons with AD develop amyloid plaques and Tau-containing neurofibrillary tangles as early as 20 years, for the former, and 15 years, for the latter, before the diagnosis of dementia [1]. However, the diagnosis of AD at a very early stage is far from being fully realized. Individual with the disease experience a specific set of very mild cognitive impairments (MCI) which is now considered as a valid target to study prodromal AD [2].

Neuroimaging studies have identified several biomarkers that have proven to be relevant in the diagnosis and assessment of AD and MCI patients [2], [3], [4]. The relationship between MRI measurements and pathophysiological changes in AD has been well researched, and hippocampal atrophy on MRI has been correlated with confirmatory pathological findings [5], [6]. Moreover, hippocampus and entorhinal cortex atrophy has some predictive value to identify MCI progressing to dementia due to AD [7], [8], [9], [10], [11] and MRI can track amyloid and tau propagation [12]. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning can also track pathological brain changes. For instance, fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography shows metabolism reductions and longitudinal decline in the posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, parietotemporal cortex, and frontal cortex of patients with AD [13]. The wealth of studies on biomarkers measured with MRI and PET has led to incorporating these approaches in the new diagnostic criteria for AD and MCI [2], [3], [4], [14]. Although amyloid-targeting PET imaging has been shown sensitive to the diagnostic of AD, it proved logistically and financially out of reach for the first phase of the Consortium for the early identification of Alzheimer's disease–Quebec (CIMA-Q) study. Functional MRI (fMRI) studies have reported that persons with a genetic risk for AD [15] or with early MCI [16], [17] show larger task-related brain activation (i.e., hyperactivation) than healthy older adults. Unlike most other cohorts, CIMA-Q has included a task-related fMRI sequence as hyperactivation might represent a very early marker of the disease.

The preservation of biomaterials from well-ascertained individuals is necessary to investigate and establish biological biomarkers that can help in the diagnosis of the disease. Ideally, these biomaterials should be obtained from longitudinal studies of incipient AD so that early biomarkers can be established. Currently, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has provided sensitive assessments for the levels of 40 or 42 amino acid long amyloid beta peptides (Aβ40, Aβ42), Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios, which have a good concordance with PET imaging of Aβ in live individuals, and of full-length or phosphorylated Tau protein [18]. Decreased Aβ42 and elevated total or phosphorylated Tau levels in the CSF have been shown to be useful predictors of clinical progression [18], [19]. However, there is still a strong need to identify additional biological biomarkers of the earliest AD stages, not only in the CSF, but also in the blood. Finally, cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNC) can be reprogrammed into human-induced pluripotent stem cells, which then can be differentiated into neurons and other brain cell types to investigate underlying molecular mechanisms of the disease [19], [20].

Objective cognitive impairment in persons with MCI can differentiate those suffering from the early signs of AD from those who will remain stable [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. In addition, neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as depression, apathy, anxiety, and sleep disturbances, are predictive of future cognitive decline [26], [27], [28], [29]. Although promising, the results from these previous studies have limitations. First, in many cases, the design was retrospective and did not distinguish between the reference standard to diagnose dementia and the predictive tests. Second, most studies with MCI included a relatively short follow-up period. This is problematic to identify very early markers. There is some evidence that MCI might be preceded by a phase of subjective cognitive decline (SCD) that corresponds to the earliest behaviorally detectable phase of AD [14]. Hence, including persons with SCD in prospective cohorts should contribute to pinpointing markers that precede the MCI phase. Recently, a set of criteria for SCD has been proposed whereby SCD relies on the presence of memory complaints accompanied by worries [30]. However, a larger number of prospective multidimensional studies are needed to better characterize SCD as a preclinical stage of AD.

Finally, it has been proposed that late-onset sporadic AD develops when a combination of genetic and environmental risk factors surpasses the self-repair capacity of the brain. Numerous risk factors have been highlighted and many of them are potentially modifiable. Health factors (e.g., cardiovascular diseases or metabolic conditions) [31], [32], [33], [34] and lifestyle habits (e.g., education, physical activity, diet, social engagement) [35], [36], [37], [38] have been associated to cognitive decline and dementia and will be measured in the CIMA-Q cohort.

The CIMA-Q focuses on accruing clinical, neuropsychological, and neuroimaging data, and preserving biomaterials with a special attention given to SCD individuals, in the hope that this cohort will provide valuable tools to identify early biomarkers of AD.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

The CIMA-Q is a multicenter longitudinal, parallel group study (for organizational structure see Supplementary Material A, Figure A1). In its initial phase, the CIMA-Q cohort is composed of 290 participants: 31 with mild AD, 88 with MCI, 115 with SCD, and 56 age-matched controls (CTL). Volunteers were recruited from participating memory clinics, advertisements in electronic media, ads posted in the community, and among participants from the NuAge population study from Montreal, Sherbrooke or Quebec City (Province of Quebec, Canada).

All participants underwent clinical evaluations and psychometric testing. Blood was collected, separated, and stored as plasma, serum, RNA extraction, or buffy coat from each participant. Participants could also consent to optional tests which included MRI, PET, CSF collection, cryopreservation of their PBMNC to eventually produce induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) and iPSC-differentiated cell types. They could also consent to postmortem brain retrieval. In addition, consent was obtained to be contacted for participation in other related studies led by CIMA-Q members. The percentage of individuals that received optional procedures were as follows: MRI 49%, PET 10%, CSF collection 21%, stem cell study 100%, brain donation 77%. All participants accepted future study participation.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Clinical diagnosis by expert physicians was verified via standardized checklists using accepted criteria. Diagnostic criteria for AD and MCI was based on the NIA/AA [4], [14]. MCI individuals were subdivided into early and late stages based on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and AD Neuroimaging Initiative criteria [2], and we sought to recruit a sufficient number of participants in each subgroup to examine this factor. SCD categorization relied on the criteria from the Subjective Cognitive Decline Initiative [30], [39], CTL participants were recruited based on strict inclusion criteria and from the same community. Furthermore, we ensured as much as possible that sociodemographic characteristics were similar in CTL as in MCI and SCD. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for each subject group are detailed in Supplementary Material B (Tables B1a to B1c).

Our objective was for the cohort to reflect the type of participants seen in an everyday primary care clinical setting (for SCD and MCI) and memory clinics (for AD), so participants with concomitant medications and comorbidities such as mild depression or mild cardiovascular diseases could be included if they fell within the accepted parameters stated by the diagnostic criteria. Individuals were eligible to participate if fluent in either French or English to reflect the two official languages in Canada. Volunteers were not prevented from participating in other clinical projects if it did not interfere with their participation in this cohort; the case being, this information was recorded. A lower age limit of 65 years was established to exclude patients with early-onset AD, but no upper age limit was set. Individuals were excluded if life expectancy at screening was estimated by the medical team to be less than three years.

2.3. Assessments and procedures

The study schedule (Supplementary Material C, Figure C1) and the assessment procedures are detailed in Supplementary Material C. All measures are listed in Table 1. A telephone prescreening interview (visit 00) was conducted during which the project was explained, verbal informed consent was obtained, exclusion/inclusion criteria were reviewed. Moreover, the Telephone Mini–Mental State Examination (T-MMSE) [40] and the presence of a memory complaint with or without worries were documented [30]. Visit 01 (screening/baseline) includes a standardized clinical evaluation and questionnaires to measure health, lifestyle, cognitive complaints, clinical expression, functional impact, and emotional and behavioral symptoms. As a complement to the subject's evaluation, an informant was asked to complete at-home questionnaires. At visit 02, blood samples were obtained under fasting conditions (Supplementary Material C, Table C1). The subjects were then given a snack followed by a standardized neuropsychological and neuropsychiatric evaluation conducted by a CIMA-Q–certified psychometrician. The MRI session consists of anatomical, pathological, and vascular imaging, as well as connectivity/functional imaging sequences. For a subgroup of participants, a task-related activation sequence was done last in which they were asked to encode a series of images of familiar objects as well as their position. Participants who agreed to partake in the PET protocol were scanned using intravenous 18FDG tracer. For subjects who had accepted to undergo a lumbar puncture for CSF collection, a neurologist obtained 10–15 mL of fluid per Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative/American Alzheimer Disease Centers recommendations in a subsequent visit [9]. Finally, at time of death, the Douglas-Bell Canada Brain Bank staff stands ready to coordinate the extraction of the brain at the nearest autopsy room for those individuals who consented to the ultimate portion of the study. One hemisphere is being fixed and stored in formalin, and the other is sectioned in thick serial sections which are frozen and then kept at −80°C until use. A collaborating neuropathologist performs the neuropathological assessment.

Table 1.

Clinical, cognitive, neuropsychiatric measures and neuroimaging sequences

| Clinical evaluation session | |||

| Cognition and function | Reserve and expertise | Psychiatric SX and sleep | Physical health |

| MoCA | Bartrés-Faz reserve | Apathy inventory (informant) | Frailty index |

| Stroop D-KEFS™ | Questionnaire on bilingualism | NPI-Q | Physical self-maintenance scale |

| T-MMSE | NUTRITION | PHQ-9 | Medication use |

| Logical memory subtest (WMS) | MNA® (short) | Stop-bang | Hachinski ischemic scale |

| ADCS-ADL | Charlson comorbidity index | ||

| Blood puncture (50 ml) | |||

| Neuropsychological & neuropsychiatric evaluation session | |||

| Memory | Executive functions | Psychiatric SX and sleep | Cognitive complaint |

| Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test | Trail A and B | Geriatric Depression Scale | Cognitive change index |

| Face-Name association | Digit symbol | Geriatric Anxiety Index | QAM (short) |

| Envelope test | Alpha span (short) | Apathy Inventory (participant) | Lifestyle |

| Memoria Free and Cued recall | Hayling | Epworth Sleepiness Scale | VLS questionnaire |

| Perception | Language | Insomnia Severity Index | |

| Object decision subtest (BORB) | Boston naming test | Sleep length/quality questionnaire | |

| Line orientation subtest (BORB) | Animal fluency | ||

| Magnetic resonance imaging sequences | |||

| Anatomical imaging | Pathological imaging | Vascular imaging | Connectivity/functional imaging |

| 3D T1w | PD/T2w | FLAIR; T2* | 30-direction DTI; resting state BOLD; task-related activation |

Abbreviations: MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; D-KFES, Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System™; T-MMSE, Telephone Mini–Mental State Examination; WMS, Wechsler memory scale; SX, symptoms; NPI-Q, Neuropsychiatry Inventory; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; MNA, Mini-Nutritional Assessment; BORB, Birmingham Object Recognition Battery; ADCS-ADL, Alzheimer's Disease Co-operative Study-Activities of Daily Living; QAM, Self-reported Memory Questionnaire; VLS, Victoria longitudinal study; 3DTIw, 3D T1-weighted magnetic resonance imagery; PD/T2w, proton density, T2-weighted magnetic resonance imagery; FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; T2*, T2-star–weighted magnetic resonance imagery; DT, diffusion tensor imaging; BOLD, blood oxygenation-level-dependant imagery.

2.4. Follow-up

As CIMA-Q is a longitudinal study, our goal is to collect data and to identify future diagnosis in successive time points for participants with SCD and MCI. The current follow-up interval for full assessment is every two years. The two-year follow-up includes the clinical, neuropsychological and neuropsychiatric evaluations, blood draw, and neuroimaging for all MRI-compatible participants. In addition, CTL, MCI, and SCD are contacted by phone within three months of their 1-year testing anniversary for a brief interim phone assessment. This interim contact includes a T-MMSE, self-report for health and lifestyle, questionnaires about functional impairment, mood and sleep, medication use and updates of medical history in the last year. The main goals of this interim contact are to foster retention, to identify those who would have received a clinical diagnosis of dementia or other severe diseases during their first follow-up year, to get information on those who might move in the following year and to collect health data that might be useful to identify causes for eventual dropouts.

2.5. Quality control procedures

Rigorous quality control procedures were established for data, neuroimaging, and biological material and are detailed in Supplementary Material D along with the methods for processing biological samples.

2.6. Ethical aspects

CIMA-Q research activities comply with Good Clinical Practice guides and requirements from the funding agencies. The study has received approval from the coordinating ethics committee of the Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Montréal. Participants gave their written informed consent before enrollment in the study and for the different components of the project. All information collected during the study is deidentified and databased in the Longitudinal Online Research and Imaging System (LORIS). Deidentification procedures are described in Supplementary Material E.

2.7. Database, access, and statistical considerations

LORIS is a powerful web-based database architecture [41], where data can be consolidated within a central repository and then made available to the entire network for download. The integrated nature of LORIS facilitates multimodality cross-analyses.

The number of participants recruited is sufficient to allow detection of a small-to-medium effect size for a group difference (i.e., estimated effect size that can be detected with this N is about d' = .46). Considering that a large effect size is expected between AD and CTL and that a medium effect size is expected between MCI and AD, this should be sufficient for most of the research questions that our group is likely to address. In addition, with a 15% progression rate to dementia and a drop-out rate of about 7%, we expect to identify about 27 MCI progressors at their first follow-up two years later (even though we are aware that progression rate might not be linear), which should allow sufficient power to detect a medium-size group difference between progressor and stable MCI. CIMA-Q complies with the principles of open science. All data and biological materials are available to the research community to address research questions on aging and dementia on authorization by the User Access Committee. The procedure is detailed in http://www.cima-q.ca/. Access is limited to CIMA-Q members but membership is open to all scientists interested in AD research.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical, neuropsychological, and neuroimaging data

Table 2 shows the sociodemographic characteristics and performance on the MoCA for the 290 participants enrolled in the four groups. In total, 142 study participants were scanned with MRI (Supplementary Material F, Table F1). Scanned participants had a mean age of 73.6 years, 30 were CTL, and 67% were female. 112 participants completed the task-relation activation condition. Morphometry, diffusion tractography, resting state, and task-based fMRI analyses will be reported separately. Note that fifteen additional participants were tested for clinical and neuropsychological assessment but were excluded from the CIMA-Q cohort because they did not meet inclusion/exclusion criteria based on the cognitive testing. Their demographic and biological characteristics were nevertheless reported.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics, MoCA performance, and recruitment source

| AD | MCI | SCD | CTL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 31 | 88 | 115 | 56 |

| Age | 77.6 ± 6.8 | 76.3 ± 5.9 | 72.6 ± 5.0 | 73.4 ± 6.2 |

| Sex (% female) | 52 | 51 | 72 | 70 |

| Education (years) | 15.2 ± 4.6 | 14.8 ± 3.6 | 14.9 ± 3.5 | 15.4 ± 3.7 |

| MoCA score | 19.3 ± 4.3 | 24.5 ± 2.0 | 28.1 ± 1.3 | 28.2 ± 1.5 |

| Recruitment source | ||||

| Community (%) | 20 | 71 | 92 | 94 |

| Memory clinics (%) | 80 | 29 | 8 | 6 |

Abbreviations: n, number of participants; AD, Alzheimer's disease; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; SCD, subjective cognitive decline; CTL, healthy control; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

3.2. Biomaterials

3.2.1. Cryopreserved PBMNC

Cryopreserved PBMNC can be reprogrammed into iPSC, which will then serve to generate different neuronal cell types involved in AD. All individuals except one, agreed to the generation of iPSC from their blood cells. PBMNC were obtained from 302 individuals among those who agreed to this portion of the project (287 from the cohort and 15 from excluded participants). On average 12 million PBMNCs were obtained per patient but the numbers of total cells ranged from 2 to 48 million cells. There was no significant correlation between the numbers of cells obtained and the age, sex, or clinical classification of the subjects. These numbers are sufficient for the generation of pluripotent stem cells by Sendai viral infections. Presently several iPSC lines have been obtained, differentiated into neurons, and characterized from three normal individuals and three patients with AD [42]. These cryopreserved PBMNC will provide cellular models to investigate underlying molecular mechanisms of diseases, identify novel therapeutic targets, and to assess novel drug treatments against AD.

3.2.2. Blood RNA, serum, plasma, and DNA

The absorbance ratio 260/280 for RNA extracted from the blood of 301 individuals was between 1.9 and 2.1 indicating a fairly pure RNA sample with little contaminants. Bioanalyzer analyses of the RNA integrity number ranged in values between 7 and 10 confirming pure RNA samples with little degradation. A yield of approximately 4 μg was obtained from each patient. There was a weak negative association between RNA yield and age (Spearman rank correlation r = −0.1227, P = .0382) but not with sex or clinical classification. Genomic DNA was extracted from the buffy coat fraction and quality was confirmed with OD260/280 ratios of 1.8–2.0 and PCR amplification of random genes. RNA, serum, plasma, and DNA are aliquoted and stored at −80°C (Supplementary Material D, 3. Biological samples).

3.3. AD-related biological features

3.3.1. Apo E genotyping

The APOE-ε3 allele, at a 76.57% frequency, was the most abundant allele present in the 303 individuals who accepted this portion of the project (288 in cohort and 15 excluded from the cohort), whereas APOE-ε2 and APOE-ε4 alleles are more rare at 16.17% and 7.27%, allele frequencies, respectively (Supplementary Material G, Tables G1–G3). Consistently, 60.40% of the 303 individuals had genotypes of APOE-ε3/3, followed by 21.45% APOE-ε3/4, 10.89% APOE-ε2/3, 4.95% APOE-ε4/4, 1.32 % APOE-ε2/2, and 1% APOE-ε2/4. These are very close to genotype distribution previously observed in normolipidic subjects [43].

As observed by others, this distribution of APOE genotypes and allele frequency were different within the clinical groups (Tables 3 and 4). The APOE-ε3 allele frequency decreased gradually from CTL, SCD, early MCI, late MCI (lMCI) to AD, which display the lowest amount of APOE-ε3 alleles. The levels were significantly lower in the lMCI (χ2 = 5.88, P = .015) and AD (χ2 = 9.474, P = .002) compared with CTL (Tables 3 and 4, and Supplementary Material G). As expected, the opposite was true for the APOE-ε4 allele (χ2 = 9.583, P = .002 for lMCI and χ2 = 11.75, P = .001 for AD). Interestingly, there were no difference between lMCI and AD, consistent with the current belief that most of these lMCI stand in an early phase of AD. The APOE-ε2 genotype and allele frequency does not differ as a function of group (Tables 3 and 4 and Supplementary Material G). This is supportive of the proposed protective role of APOE-ε2. Differences in APOE genotype was not associated with differences in either age or cognitive performances measured by the T-MMSE or MoCA test (Table 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of APOE frequencies within diagnostic groups

| Group | ε2, ε3, ε4 (2 df) |

ε2 (1 df) |

ε3 (1 df) |

ε4 (1 df) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | P | χ2 | P | χ2 | P | χ2 | P | |

| SCD (n = 114) | 1.361 | 0.506 | 0.472 | 0.513 | 0.965 | 0.326 | 0.246 | 0.620 |

| eMCI (n = 65) | 2.973 | 0.226 | 0.642 | 0.423 | 2.440 | 0.118 | 1.122 | 0.290 |

| lMCI (n = 22) | 11.35 | 0.003 | 0.126 | 0.722 | 5.882 | 0.015 | 9.583 | 0.002 |

| AD (n = 31) | 13.30 | 0.001 | 0.067 | 0.796 | 9.474 | 0.002 | 11.75 | 0.001 |

NOTE. Chi-square test (with or without Yates correction) was used to compare allele frequencies in SCI, eMCI, lMCI, and AD with control (n = 56).

Bold values indicate P < 0.05.

Abbreviations: n, number of participants; APOE, apolipoprotein E; SCD, subjective cognitive decline; eMCI, early mild cognitive impairment; lMCI, late mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer's dementia, df, degrees of freedom; p, probability value; χ2, chi-squared distribution.

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics and APOE ε4 carrier status within diagnostic groups

| 0 ε4 | 1 ε4 | 2 ε4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTL | |||

| n (%) | 45 (80.4) | 10 (17.9) | 1 (1.8) |

| Age | 73.65 ± 6.03 | 72.08 ± 7.34 | 68.90 ± 0 |

| T-MMSE | 25.0 ± 1.18 | 25.0 ± 1.05 | 26.0 ± 0 |

| MoCA | 27.8 ± 1.53 | 28.5 ± 1.27 | 29.0 ± 0 |

| SCD | |||

| n (%) | 88 (77.2) | 24 (21.1) | 2 (1.8) |

| Age | 72.92 ± 5.33 | 71.15 ± 3.54 | 69.95 ± 1.91 |

| T-MMSE | 24.6 ± 1.52 | 24.9 ± 1.08 | 24.5 ± 2.12 |

| MoCA | 27.7 ± 1.47 | 28.2 ± 1.24 | 29.0 ± 1.41 |

| eMCI | |||

| n (%) | 46 (70.8) | 16 (24.6) | 3 (4.6) |

| Age | 76.42 ± 6.23 | 73.40 ± 4.83 | 74.6 ± 3.81 |

| T-MMSE | 24.2 ± 1.36 | 24.1 ± 1.63 | 25.3 ± 0.58 |

| MoCA | 24.7 ± 1.88 | 24.8 ± 1.42 | 26.3 ± 1.15 |

| lMCI | |||

| n (%) | 11 (50.0) | 8 (36.4) | 3 (13.6) |

| Age | 78.4 ± 4.04 | 77.9 ± 7.41 | 78.7 ± 8.93 |

| T-MMSE | 22.7 ± 2.24 | 22.5 ± 1.07 | 21.0 ± 3.61 |

| MoCA | 22.1 ± 2.17 | 23.1 ± 2.10 | 22.7 ± 1.53 |

| AD | |||

| n (%) | 15 (48.4) | 10 (32.3) | 6 (19.4) |

| Age | 78.4 ± 6.72 | 75.3 ± 7.49 | 78.7 ± 6.14 |

| T-MMSE | 20.7 ± 2.52 | 21.5 ± 2.95 | 20.2 ± 2.04 |

| MoCA | 18.3 ± 4.23 | 20.1 ± 4.84 | 19.0 ± 3.69 |

| Other | |||

| n (%) | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Age | 74.3 ± 7.68 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| T-MMSE | 23.9 ± 2.10 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| MoCA | 23.3 ± 3.44 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

NOTE. Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

Abbreviations: n, number of participants; APOE, apolipoprotein E; CTL, control; SCD, subjective cognitive decline; eMCI, early mild cognitive impairment; lMCI, late mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer's dementia; T-MMSE, Telephone Mini–Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, SD, standard deviation.

3.3.2. CSF Aβ38, Aβ40, Aβ42, and total Tau levels

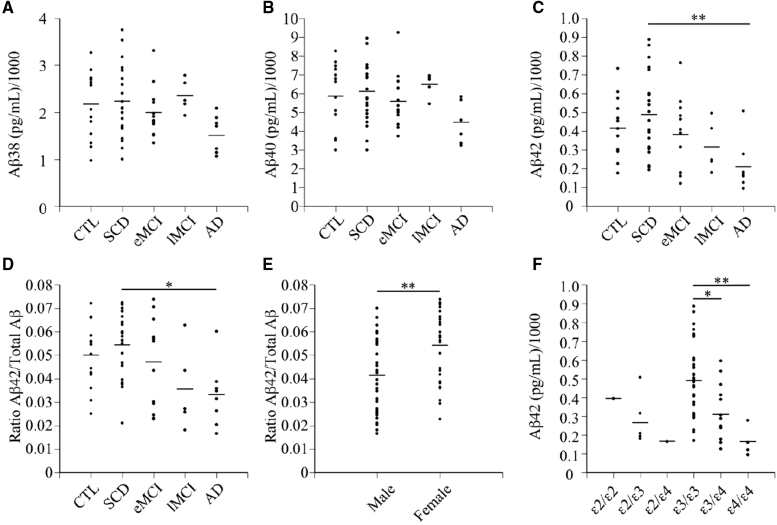

ELISA analyses of the levels of Aβ38, Aβ40, and Aβ42 in CSF indicated a slightly lower level of Aβ38 in individuals with AD relative to the other groups (Fig. 1A), but no change in Aβ40 (Fig. 1B). Significantly lower levels of Aβ42 and Aβ42/total Aβ were observed in AD relative to SCD (Fig. 1C and D). Aβ levels did not correlate with age, however, Aβ42/total Aβ levels were significantly higher in females than males (Fig. 1E). Aβ42 levels were also significantly lower in the CSF of individuals with APOE-ε3/4 and APOE-ε4/4 genotypes (Fig. 1F). Finally, CSF Aβ42 concentrations were positively correlated with MoCA scores (r2 = 0.13, P = .0025).

Fig. 1.

Amyloid beta (Aβ) concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid samples from the CIMA-Q cohort. (A) Aβ38, (B) Aβ40, and (C) Aβ42 in pg/ml of the CSF from control (CTL) individuals and individuals with subjective cognitive decline (SCD), early mild cognitively impaired (eMCI), late MCI, and Alzheimer's disease (AD). Each dot represents one individual in the category. (D–F) Ratios of Aβ42 over total Aβ (Aβ38+Aβ40+Aβ42) in each category of subjects (D), stratified into males and females (E) or per APOE genotype (F) for all subjects studied. Kruskal-Wallis statistical tests were used to analyze Aβ concentrations between diagnostic categories. The horizontal bars represent the mean. Each point represents one or several overlapping data from the individuals assessed. The Mann-Whitney statistical test was used to analyze Aβ42/total Aβ between sexes. The Kruskal-Wallis statistical test was used to analyze Aβ42 concentration between APOE genotypes. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; pg/mL, picogram/milliliter; CIMA-Q, Consortium for the early identification of Alzheimer's disease-Quιbec; APOE E, apolipoprotein E; P, probability value.

In contrast to the Aβ levels, total CSF Tau protein levels did not vary as a function of the group categories (Fig. 2A). However, CSF Tau protein levels increased slightly with age (Fig. 2B) and were lower in females than males (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Total Tau concentration in cerebrospinal fluid samples from the CIMA-Q cohort. (A) Total Tau levels in pg/mL of the CSF from control (CTL) individuals and individuals with subjective cognitive decline (SCD), early mild cognitively impaired (eMCI), late MCI, and Alzheimer's disease (AD) individuals and (B) expressed relative to the age of subjects or (C) relative to males and females. Each dot represents one subject. The Kruskal-Wallis statistical tests were used to analyze total Tau levels between diagnostic categories. A Spearman correlation was used to analyze total Tau levels versus age. The horizontal bars in (A) and (C) represent the mean. Each point represents one or several overlapping data from the individuals assessed. The Mann Whitney test was used to analyze total Tau concentrations between sexes. Abbreviations: pg/mL, picogram/milliliter; CIMA-Q, Consortium for the early identification of Alzheimer's disease-Québec; R, correlation coefficient; P, probability value.

4. Discussion

A consortium has been established in Quebec to support high-quality AD research. CIMA-Q has created a registry that contains longitudinal examinations in multiple domains at various stages of the disease, from the preclinical, prodromal to early AD stage. Combining well-defined measures of neuroimaging, cognitive, and biological information for each individual will permit an accurate assessment of the contribution and interaction between different levels of disease expression and allow identifying early disease markers. The follow-up will support studies looking at the predictive diagnostic value of these different markers. The comprehensive assessment of lifestyle factors and health conditions will allow determining the role of modifiable factors on the progression of symptoms, in interaction with genetic and epigenetic ones. Because our primary objective is the inclusion of pre-symptomatic AD, the presence of other neurodegenerative diseases was used as an exclusion criteria. This might reduce our ability to identify cases with mixed etiology. However, participants were not excluded because of vascular or metabolic comorbidity that make them at risk of AD, which allows inclusion of cases with mixed vascular AD.

There are differences and similarities between the CIMA-Q study and other major current cohorts which include SCD and MCI. Contrary to CIMA-Q, Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative [9] is not a trial-ready cohort and focuses more on AD than on the prodromal stages. The SCIENCe cohort [44] is an SCD cohort only and hence, does not cover the full spectrum of AD. The Canadian consortium on neurodegeneration in aging cohort, COMPASS-ND, focuses on the dementia stages of the diseases [45]. No other cohort has cryopreserved PBMNC ready to develop novel iPSC cell lines from well-ascertained sporadic AD and normal individuals. Finally, given the cultural and linguistic context in Quebec, one innovative feature of CIMA-Q is that it includes a significant proportion of bilingual participants (French and English) tested in their native language with a well-validated battery.

CIMA-Q created a remarkable opportunity to bring together expertise that is otherwise dispersed; to identify, share, and test cutting-edge hypotheses within and across domains; to develop harmonization and quality control procedures to ensure that the highest quality of information is gathered. It will generate findings that will enable the identification of key tools to improve early diagnosis and prognosis, and to put forward novel prevention strategies for AD. Quality controlled network of MRI and PET platforms will enable standardized state-of-the-art acquisitions to allow the discovery of sensitive and specific imaging phenotypes predictive of progression to clinically probable AD.

CIMA-Q will also catalyze translation research on dementia. Having access to biological samples that are tied to outstanding subject ascertainment, high-level imaging data, and neuropsychology results will facilitate research projects that cross the field of basic and clinical science. Integrated and harmonized tools and procedures will in addition support and facilitate the conduct of nationwide multicentric studies related to AD. CIMA-Q will be supportive of evaluative projects relevant to the early characterization and diagnosis of AD. CIMA-Q will also foster substantial collaboration between memory clinics and support networking activities to link all levels of cognitive assessments throughout Quebec. We hope to harmonize initiatives from the “Quebec Alzheimer Plan” [46] and CIMA-Q resources, allowing for cost-efficient and state-of-the-art evaluative research for persons at risk of cognitive decline, with minimal cognitive impairment, or with early dementia. Our work will also allow a coordinated provincewide network for neuroimaging for aid in clinical diagnosis in AD. Finally, this work will contribute research recommendations [47] and updates to clinical practice guidelines.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: Prodromal evaluations of older individuals are necessary to identify presymptomatic biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease (AD) in the hope of treating these individuals before the onset of dementia.

-

2.

Interpretation: The Consortium for the early identification of Alzheimer's Disease-Quebec (CIMA-Q) cohort of 290 well-ascertained individuals focused on longitudinal clinical, neuropsychological, and neuroimaging assessments, and on collection of blood-derived biomaterials of elderly individuals.

-

3.

Future directions: The study will provide the necessary baseline to initiate studies on the identification of early biomarkers of AD. It will provide rare access to a significant number of well-characterized subjective cognitive decline individuals. Furthermore, the CIMA-Q study generated an unprecedented biobank of cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cell culture, which can be reprogrammed into pluripotent stem cells and pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons or other brain cell types for the biological study of the underlying causes of AD.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Isabelle Lussier, Isabel Arsenault, and Anne Morinville for their help in preparing the manuscript. Thanks to Annie-Kim Gilbert, Andréanne Parent, Anne Morinville, Céline Fouquet, Isabel Arsenault, Karine Thorn, Christine St-Pierre and the physicians, nurses and other staff members involved in assessing participants, in data entry and quality control and in the implementation of CIMA-Q. They would like to gratefully acknowledge the work of Ana Sofia Correia (set up of SOP standard operating procedures for the collection and processing of blood samples and cryopreservation of PBMNC), Andrea Hébert Losier (collection of biomaterials), Benedicte Foveau (DNA extractions, Apo E genotypes, analyses of Apo E data), and Marie-Lyne Fillion (collection of biomaterials, ELISA assays and analyses for Aß levels in CSF, coordination of the biobank). Thanks to Lynn Maynard and Jennifer Valdivias for English revision of the manuscript.

CIMA-Q is supported by the Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé (FRQS) -Pfizer Innovation Program [grant numbers #27239 to all authors], the Quebec Network for Research on aging, a network supported by the FRQS, the Fondation Courtois (NeuroMod project; grant to Belleville), the Consortium for the Neurodegeneration associated with Aging (CCNA/CCNV; grant CAN #137794) and CIHR (grant #154265 to Belleville). Members of the funding agencies are part of CIMA-Q advisory boards but their role is that of an observer and hence they have no control on decisions, content or management of CIMA-Q. S.B. holds a Canada Research Chair on Cognitive Neuroscience of Aging and Brain Plasticity. S.D. is a Research Scholar from the Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé (#30801). F.C. is a Research Scholar from the Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé (#253895 and #26936).

Members of the CIMA-Q group: Pierre Bellec, Sylvie Belleville, Christian Bocti, Frédéric Calon, Howard Chertkow, Louis Collins, Stephen Cunnane, Simon Duchesne, Pierrette Gaudreau, Serge Gauthier, Sébastien S. Hébert, Carol Hudon, Marie-Jeanne-Kergoat, Andréa C. LeBlanc, Nicole Leclerc, Naguib Mechawar, Natalie Philips, Jean-Paul Soucy, Thien Thanh Dang Vu, Louis Verret, Juan Manuel Villalpando.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: S.D. is officer and shareholder in True Positive Medical Devices Inc., which will provide morphometric analyses of MRIs for the CIMA-Q project.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2019.07.003.

Contributor Information

Sylvie Belleville, Email: sylvie.belleville@umontreal.ca.

Consortium for the Early Identification of Alzheimer's disease-Quebec (CIMA-Q):

Pierre Bellec, Sylvie Belleville, Christian Bocti, Frédéric Calon, Howard Chertkow, Louis Collins, Stephen Cunnane, Simon Duchesne, Pierrette Gaudreau, Serge Gauthier, Sébastien S. Hébert, Carol Hudon Marie-Jeanne-Kergoat, Andréa C. LeBlanc, Nicole Leclerc, Naguib Mechawar, Natalie Philips, Jean-Paul Soucy, Thien Thanh Dang Vu, Louis Verret, and Juan Manuel Villalpando

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Bateman R.J., Xiong C., Benzinger T.L., Fagan A.M., Goate A., Fox N.C. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease. New Engl J Med. 2012;367:795–804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert M.S., DeKosky S.T., Dickson D., Dubois B., Feldman H.H., Fox N.C. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jack C.R., Jr., Albert M.S., Knopman D.S., McKhann G.M., Sperling R.A., Carrillo M.C. Introduction to the recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2011;7:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKhann G.M., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., Hyman B.T., Jack C.R., Jr., Kawas C.H. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashburner J., Csernansky J.G., Davatzikos C., Fox N.C., Frisoni G.B., Thompson P.M. Computer-assisted imaging to assess brain structure in healthy and diseased brains. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Csernansky J.G., Hamstra J., Wang L., McKeel D., Price J.L., Gado M. Correlations between antemortem hippocampal volume and postmortem neuropathology in AD subjects. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18:190–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herholz K. PET studies in dementia. Ann Nucl Med. 2003;17:79–89. doi: 10.1007/BF02988444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klunk W.E., Engler H., Nordberg A., Wang Y., Blomqvist G., Holt D.P. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer's disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:306–319. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mueller S.G., Weiner M.W., Thal L.J., Petersen R.C., Jack C.R., Jagust W. Ways toward an early diagnosis in Alzheimer's disease: the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) Alzheimer's Dement. 2005;1:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coimbra A., Williams D.S., Hostetler E.D. The role of MRI and PET/SPECT in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:629–647. doi: 10.2174/156802606776743075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jagust W., Gitcho A., Sun F., Kuczynski B., Mungas D., Haan M. Brain imaging evidence of preclinical Alzheimer's disease in normal aging. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:673–681. doi: 10.1002/ana.20799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jack C.R., Jr., Dickson D.W., Parisi J.E., Xu Y.C., Cha R.H., O'Brien P.C. Antemortem MRI findings correlate with hippocampal neuropathology in typical aging and dementia. Neurology. 2002;58:750–757. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.5.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosconi L., Mistur R., Switalski R., Tsui W.H., Glodzik L., Li Y. FDG-PET changes in brain glucose metabolism from normal cognition to pathologically verified Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:811–822. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-1039-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sperling R.A., Aisen P.S., Beckett L.A., Bennett D.A., Craft S., Fagan A.M. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bookheimer S.Y., Strojwas M.H., Cohen M.S., Saunders A.M., Pericak-Vance M.A., Mazziotta J.C. Patterns of brain activation in people at risk for Alzheimer's disease. New Engl J Med. 2000;343:450–456. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008173430701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickerson B.C., Salat D.H., Bates J.F., Atiya M., Killiany R.J., Greve D.N. Medial temporal lobe function and structure in mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:27–35. doi: 10.1002/ana.20163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clement F., Belleville S. Compensation and disease severity on the memory-related activations in mild cognitive impairment. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:894–902. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blennow K., Zetterberg H. Biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease: current status and prospects for the future. J Intern Med. 2018;284:643–663. doi: 10.1111/joim.12816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansson O., Seibyl J., Stomrud E., Zetterberg H., Trojanowski J.Q., Bittner T. CSF biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease concord with amyloid-β PET and predict clinical progression: A study of fully automated immunoassays in BioFINDER and ADNI cohorts. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:1470–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taoufik E., Kouroupi G., Zygogianni O., Matsas R. Synaptic dysfunction in neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental diseases: an overview of induced pluripotent stem-cell-based disease models. Open Biol. 2018;8 doi: 10.1098/rsob.180138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tabert M.H., Manly J.J., Liu X., Pelton G.H., Rosenblum S., Jacobs M. Neuropsychological prediction of conversion to Alzheimer disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:916–924. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dierckx E., Engelborghs S., De Raedt R., Van Buggenhout M., De Deyn P.P., Verte D. Verbal cued recall as a predictor of conversion to Alzheimer's disease in Mild Cognitive Impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:1094–1100. doi: 10.1002/gps.2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell J., Arnold R., Dawson K., Nestor P.J., Hodges J.R. Outcome in subgroups of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is highly predictable using a simple algorithm. J Neurol. 2009;256:1500–1509. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ewers M., Walsh C., Trojanowski J.Q., Shaw L.M., Petersen R.C., Jack C.R., Jr. Prediction of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease dementia based upon biomarkers and neuropsychological test performance. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:1203–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belleville S., Fouquet C., Hudon C., Zomahoun H.T.V., Croteau J. Neuropsychological measures that predict progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's type dementia in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2017;27:328–353. doi: 10.1007/s11065-017-9361-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Modrego P.J., Ferrandez J. Depression in patients with mild cognitive impairment increases the risk of developing dementia of Alzheimer type: a prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1290–1293. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.8.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer K., Di Iulio F., Varsi A.E., Gianni W., Sancesario G., Caltagirone C. Neuropsychiatric predictors of progression from amnestic-mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease: the role of depression and apathy. J Alzheimer's Dis JAD. 2010;20:175–183. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmer K., Berger A.K., Monastero R., Winblad B., Backman L., Fratiglioni L. Predictors of progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;68:1596–1602. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260968.92345.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potvin O., Lorrain D., Forget H., Dube M., Grenier S., Preville M. Sleep quality and 1-year incident cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults. Sleep. 2012;35:491–499. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jessen F., Amariglio R.E., van Boxtel M., Breteler M., Ceccaldi M., Chetelat G. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2014;10:844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan Z.S., Beiser A.S., Vasan R.S., Roubenoff R., Dinarello C.A., Harris T.B. Inflammatory markers and the risk of Alzheimer disease: the Framingham Study. Neurology. 2007;68:1902–1908. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000263217.36439.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitmer R.A. Type 2 diabetes and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2007;7:373–380. doi: 10.1007/s11910-007-0058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duron E., Hanon O. Hypertension, cognitive decline and dementia. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;101:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s1875-2136(08)71801-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laurin D., David Curb J., Masaki K.H., White L.R., Launer L.J. Midlife C-reactive protein and risk of cognitive decline: a 31-year follow-up. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1724–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGuinness B., Craig D., Bullock R., Passmore P. Statins for the prevention of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:Cd003160. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003160.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saczynski J.S., Pfeifer L.A., Masaki K., Korf E.S., Laurin D., White L. The effect of social engagement on incident dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:433–440. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Angevaren M., Aufdemkampe G., Verhaar H.J., Aleman A., Vanhees L. Physical activity and enhanced fitness to improve cognitive function in older people without known cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:Cd005381. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005381.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Livingston G., Sommerlad A., Orgeta V., Costafreda S.G., Huntley J., Ames D. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet (London, England) 2017;390:2673–2734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molinuevo J.L., Rabin L.A., Amariglio R., Buckley R., Dubois B., Ellis K.A. Implementation of subjective cognitive decline criteria in research studies. Alzheimer's Dement. 2017;13:296–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newkirk L.A., Kim J.M., Thompson J.M., Tinklenberg J.R., Yesavage J.A., Taylor J.L. Validation of a 26-point telephone version of the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2004;17:81–87. doi: 10.1177/0891988704264534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Das S., Zijdenbos A.P., Harlap J., Vins D., Evans A.C. LORIS: a web-based data management system for multi-center studies. Front Neuroinform. 2011;5:37. doi: 10.3389/fninf.2011.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foveau B., Correia A.S., Hebert S.S., Rainone S., Potvin O., Kergoat M.J. Stem cell-derived neurons as cellular models of sporadic Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;67:893–910. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poirier J., Davignon J., Bouthillier D., Kogan S., Bertrand P., Gauthier S. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1993;342:697–699. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91705-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slot R.E.R., Verfaillie S.C.J., Overbeek J.M., Timmers T., Wesselman L.M.P., Teunissen C.E. Subjective Cognitive Impairment Cohort (SCIENCe): study design and first results. Alzheimer's Res Ther. 2018;10:76. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0390-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chertkow H., Borrie M., Whitehead V., Black S., Feldman H.H., Gauthier S. The comprehensive assessment of neurodegeneration and dementia: Canadian cohort study. Can J Neurol Sci. 2019;46:499–511. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2019.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bergman H. Meeting the Challenge of Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders: A Vision Focused on the Individual, Humanism, and Excellence. Report of the Committee of Experts for the Development of an Action Plan on Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders. La Dir des Commun du ministère de la Santé des Serv sociaux du Québec. 2009:137 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gauthier S., Patterson C., Gordon M., Soucy J.P., Schubert F., Leuzy A. Commentary on “Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease.” A Canadian perspective. Alzheimer's Dement. 2011;7:330–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.