To the Editor—We read with interest the article by Zerbato et al [1] on the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) reservoir harbored in naive CD4+ T cells (TN cells). We would like to share our genetic evidence that TN cells harbor a substantial fraction of the intact reservoir to reinforce the message that TN cells may play a central role in shaping the reservoir in comparison with central memory CD4+ T cells (TCM cells).

We sorted TN cells (defined as CD45RA+, CCR7+, CD27+) and TCM cells (defined as CD45RA−, CCR7+, CD27+) from CD3+CD8− peripheral blood mononuclear cells of 2 chronically HIV-1–infected donors who were virally suppressed on antiretroviral therapy (ART) for 2 years. We measured total HIV DNA and amplified HIV proviruses at limiting dilution in each subset. We sequenced a total of 365 and 227 near-full-length proviruses in subjects 1 and 2, respectively, as described [2]. All proviruses with an intact envelope (n = 159) in subject 1 were CCR5-tropic while the majority of evaluable proviruses (n = 106) in subject 2 were CXCR4-tropic.

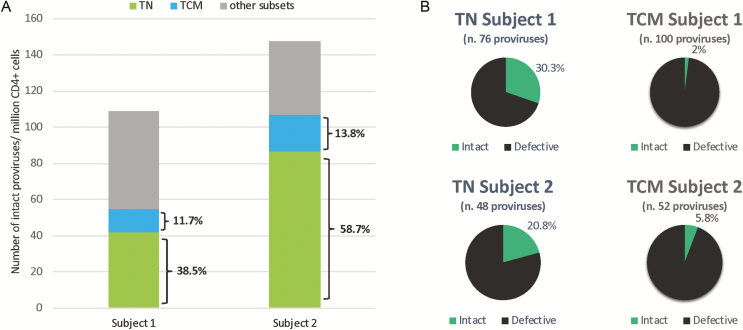

Consistent with Zerbato et al [1] and previous reports [3–5], total HIV DNA was higher in TCM cells (4583 and 3717 HIV/million cells for subjects 1 and 2) than in TN cells (654 and 1236, respectively). After proviral sequencing of sorted subsets, we calculated the contribution of intact proviruses/million CD4+ cells by these 2 subsets. Even though the HIV DNA levels were higher in TCM cells for both subjects, the contribution of intact proviruses by TN cells was far greater than by TCM cells, representing 38.5% and 58.7% of the intact reservoir (Figure 1A). Similarly, the percentages of intact proviruses were also higher in TN cells than in TCM cells (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Genetic evidence that naive T cells contribute significantly to the replication-competent reservoir. A, The number of intact proviruses per million CD4+ T cells for both subjects was determined after 2 years on suppressive ART. By sorting PBMCs into TN cells (green), TCM cells (blue), and other subsets (gray), the numbers of intact proviruses in all of the subsets were determined. TN cells contributed more intact proviruses than TCM cells. B, The percentages of intact (teal) and defective (black) proviruses within the 2 subsets are shown. Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; TCM, central memory CD4+ T cells; TN, naive CD4+ T cells.

These findings could explain why the authors found equal or even higher levels of HIV RNA in TN than in TCM cells after latency reversal, even if the level of total HIV DNA was significantly higher in TCM cells.

Notably, these 2 subjects represent 2 classes of chronic infection based on viral tropism and clinical evolution, yet both showed a prominent contribution of TN cells to the reservoir, consistent with Zerbato et al [1]. Specifically, subject 1 had a protracted CD4+ cells decline with only CCR5-tropic proviruses and a nadir of 295 CD4+ cells/µLafter 21 years of infection, while subject 2 had more rapid progression with a majority of CXCR4-tropic proviruses and a nadir of 0 CD4+ cells/µL after 6 years of infection.

We do agree with the authors that the role of TN cells has been underestimated so far because of the low integration level of HIV DNA in this subset.

TN and TCM cells likely experience different selection pressures, which lead to differences in proviral decay and preservation of intact proviruses within TN cells. The potential for TCM cells to differentiate into effector memory cells may explain their less prominent contribution to the intact reservoir. A limitation of our study is that we cannot prove what fraction of TN cells are truly naive. Due to the longer life span of TN cells and their potential to convert into more differentiated T cells, TN cells may play a crucial role in maintaining and replenishing the HIV reservoir in patients on ART.

Notes

Financial support. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants 1UM1AI26617, R01 AI120011, and R21AI_143564).

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Zerbato JM, McMahon DK, Sobolewski MD, Mellors JW, Sluis-Cremer N. Naive CD4+ T cells harbor a large inducible reservoir of latent, replication-competent HIV-1. Clin Infect Dis 2019. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pinzone MR, VanBelzen DJ, Weissman S, et al. Longitudinal HIV sequencing reveals reservoir expression leading to decay which is obscured by clonal expansion. Nat Commun 2019; 10:728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chomont N, El-Far M, Ancuta P, et al. HIV reservoir size and persistence are driven by T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation. Nat Med 2009; 15:893–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hiener B, Horsburgh BA, Eden JS, et al. Identification of Genetically Intact HIV-1 Proviruses in Specific CD4+ T Cells from Effectively Treated Participants. Cell Rep 2017; 21:813–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dai J, Agosto LM, Baytop C, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus integrates directly into naive resting CD4+ T cells but enters naive cells less efficiently than memory cells. J Virol 2009; 83:4528–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]