Abstract

Background

The choice of phosphate/nitrogen source and their concentrations have been shown to have great influences on antibiotic production. However, the underlying mechanisms responsible for this remain poorly understood.

Results

We show that nutrient-sensing regulator PhoP (phosphate regulator) binds to and upregulates most of genes (ery cluster genes) involved in erythromycin biosynthesis in Saccharopolyspora erythraea, resulting in increase of erythromycin yield. Furthermore, it was found that PhoP also directly interacted with the promoter region of bldD gene encoding an activator of erythromycin biosynthesis, and induced its transcription. Phosphate limitation and overexpression of phoP increased the transcript levels of ery genes to enhance the erythromycin production. The results are further supported by observation that an over-producing strain of S. erythraea expressed more PhoP than a wild-type strain. On the other hand, nitrogen signal exerts the regulatory effect on the erythromycin biosynthesis through GlnR negatively regulating the transcription of phoP gene.

Conclusions

These findings provide evidence that PhoP mediates the interplay between phosphate/nitrogen metabolism and secondary metabolism by integrating phosphate/nitrogen signals to modulate the erythromycin biosynthesis. Our study reveals a molecular mechanism underlying antibiotic production, and suggests new possibilities for designing metabolic engineering and fermentation optimization strategies for increasing antibiotics yield.

Keywords: Erythromycin biosynthesis, Antibiotics, Phosphate metabolism, PhoP regulator, Transcriptional regulation

Background

In actinomycetes, nitrogen and phosphate control of the biosynthesis of antibiotics, pigments, immunomodulators, and many other types of secondary metabolites is a well-known phenomenon [8, 13, 18, 21]. Regulatory network based on nitrogen regulator GlnR and phosphate regulator PhoP as well as the underlying mechanisms of how nutritional signals exert the regulatory effect on the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites have widely been investigated in Streptomyces. The Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) ΔglnR mutant strain was clearly affected with respect to antibiotic production. No production of the pigmented antibiotics actinorhodin and undecylprodigiosin was observed on solid medium and in liquid culture. Complementation with the glnR gene encoding nitrogen regulator restored the wild-type phenotype [17]. Moreover, a similar effect on antibiotic production was also reported for the GlnR protein of the rifamycin producer Amycolatopsis mediterranei. The deletion of the A. mediterranei glnR gene resulted in a reduced rifamycin production. The complementation of a S. coelicolor glnR mutant strain FS10 with the glnR gene of A. mediterranei led to an excessive production of undecylprodigiosin, while actinorhodin production was blocked [24]. Apparently, GlnR influences antibiotic production of A. mediterranei and S. coelicolor A3(2). It was indicated that GlnR is a global regulator with a dual-functional impact on nitrogen metabolism and related antibiotic production. However, it is unclear how the GlnR-mediated regulation is connected to antibiotic production. GlnR may be important for the induction of a general stress response, triggered by nutrient limitation, which finally activates antibiotic biosynthesis [24]. Recently, microarray analysis and chromatin immuno-precipitation (ChIP) identified thirty-six putative GlnR target genes with GlnR binding sites throughout the Streptomyces venezuelae genome. GlnR binds to the intergenic region between the divergently transcribed jadR1 and jadR2 genes, which encode transcriptional regulators that activate and repress, respectively, expression of the jadomycin biosynthetic genes [11].

The phosphate-sensing PhoR–PhoP system is also involved in regulating the production of actinorhodin in Streptomyces lividans [15] and undecylprodigiosin in S. coelicolor [14]. The biosynthesis of the antifungal polyene macrolide pimaricin in Streptomyces natalensis is very sensitive to phosphate concentration in the culture broth. Concentrations of inorganic phosphate as low as 2 mM drastically reduced pimaricin production. No transcripts for all the pimaricin biosynthesis (pim) genes including the pathway-specific positive regulator pimR could be detected at 10 mM phosphate. A PhoP-deleted mutant reveals increased pimaricin yield and is less sensitive to phosphate concentration. No putative PhoP-binding sequences were found in the promoter regions of any of the pim genes, suggesting that phosphate control of these genes is mediated indirectly by PhoR–PhoP [10]. Martin et al. have found that PhoP regulatory effect on antibiotic biosynthesis may be exerted through signaling cascades of PhoP-AfsS-AfsR-SARP (Streptomyces antibiotic regulatory proteins, such as ActII-orf4 and RedD) in Streptomyces [9]. The studies also observed that the expression of glnR gene and some other GlnR-regulated genes is repressed by PhoP in S. coelicolor [4, 9]. These findings reveal crosstalk between global regulators (PhoP, GlnR, and AfsR) in S. coelicolor that controls the expression of genes associated with secondary metabolite biosynthesis. However, no phosphate-related gene was found in the GlnR regulon, suggesting that GlnR has no direct effect on phosphate metabolism and demonstrating that the crosstalk between GlnR and PhoP is not reciprocal [16]. Interestingly, more recently, we found that GlnR negatively regulates the transcription of phoP gene in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. There appears to be reciprocal regulatory crosstalk between GlnR and PhoP in S. erythraea, unlike S. coelicolor and S. lividans [23].

The choice of nitrogen/phosphate source and their concentrations have a great influence on the erythromycin production in S. erythraea. Reeve et al. investigated the effect of glucose, nitrogen, and phosphorus sources on the timing and extent of erythromycin production [12]. High-phosphate cultures (10–100 mM) repressed erythromycin biosynthesis and the transcription of ery genes. The production of erythromycin and transcription of ery cluster genes were induced in low-phosphate cultures (< 1 mM). In the same study, the data demonstrated that NH4NO3 and other ammonium salts gave a considerable lag before growth started, and cultures grown on it produced no or low levels of erythromycin. No ery transcript could be detected in the ammonium grown culture. This conclusion was also supported by results of recent experiments, in which the erythromycin production was strongly inhibited by ammonium [1, 5]: These results suggest that ammonium and phosphate impact the transcription of ery cluster genes and that nitrogen/phosphate metabolism and biosynthesis of erythromycin are deeply interconnected. These observations provide evidence that S. erythraea may possess a molecular mechanism involving crosstalk between nitrogen/phosphate metabolism and erythromycin biosynthesis. However, the homologous gene for afsS was not found in the S. erythraea genome and no SARP was identified as being responsible for erythromycin biosynthesis. The underlying mechanisms of how nutritional signals exert the regulatory effect on the biosynthesis of erythromycin remain poorly understood.

In this study, we identified four putative PhoP-boxes (binding sites) in the promoter regions of sace_0712 encoding erythromycin esterase and operon eryBVI-BVII, as well as in the intergenic regions between the operons eryAI-G and eryBIV-BVII, eryBI and eryBIII-F involved in erythromycin biosynthesis. It was found that the phosphate-sensing PhoP, as an activator, strongly regulated the transcription of these genes (19 genes of all 22 genes in ery cluster) responding to phosphate availability. Moreover, PhoP directly also regulated the transcription of bldD, whose product was a key regulator of actinomycetes development and activated all genes of ery cluster [2]. Nitrogen signal exerts the regulatory effect on the transcription of ery cluster through GlnR negatively regulating the transcription of phoP gene. The results suggested that PhoP played an important role in the control of biosynthesis of erythromycin in response to environmental phosphate/nitrogen signals. Our findings reveal a novel molecular mechanism underlying the antibiotics production, and suggests new possibilities for designing metabolic engineering and fermentation optimization strategies for increasing antibiotics yield.

Results

Effect of phosphate on erythromycin production

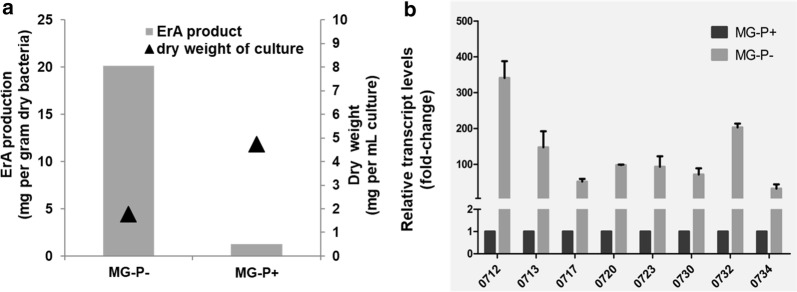

In S. erythraea, the erythromycin production and the levels of ery mRNAs were regulated by nitrogen/phosphate sources and their concentrations [12]. Recently, we found that phosphate regulator PhoP exerted positive control on phosphate metabolism and erythromycin biosynthesis [23]. To further investigate the effect of phosphate concentrations on biosynthesis of erythromycin, the S. erythraea wild-type strain NRRL2338 was grown in high-phosphate MG medium (MG-P+, 60 g/L starch, 60 mM glutamate, and 10 mM phosphate) and low-phosphate MG medium (MG-P−, 60 g/L starch, 60 mM glutamate, and 50 μM phosphate) for 3 days. Production of erythromycin (ErA) and accumulation of biomass were determined. As shown in Fig. 1a, production of erythromycin in low-phosphate MG medium is approximately 20-fold higher than that in high-phosphate MG medium. The high phosphate greatly repressed the biosynthesis of erythromycin. The transcription levels of genes in ery cluster in response to phosphate availability were examined. As expected, these genes were strongly induced during low-phosphate condition (Fig. 1b). The quantitative RT-PCR experiments indicated that transcript levels of all the transcript units (TUs) in the ery cluster significantly increased by above 100-fold. These results further demonstrated that phosphate limitation activated erythromycin production, thereby indicating the importance of phosphate source sensing/utilization in S. erythraea antibiotic production.

Fig. 1.

Effects of phosphate concentration on erythromycin (ErA) production and ery transcription. a ErA production and biomass yield of S. erythraea strain in low (40 μM (MG-P−) and high (10 mM, MG-P+) concentrations of phosphate in MG medium (50 g/L starch, 60 mM glutamate). b The transcriptional profiles of some genes in ery cluster responding to high (MG-P+) and low (MG-P−) phosphate

Identification of four binding sites of PhoP in the promoter regions of ery cluster

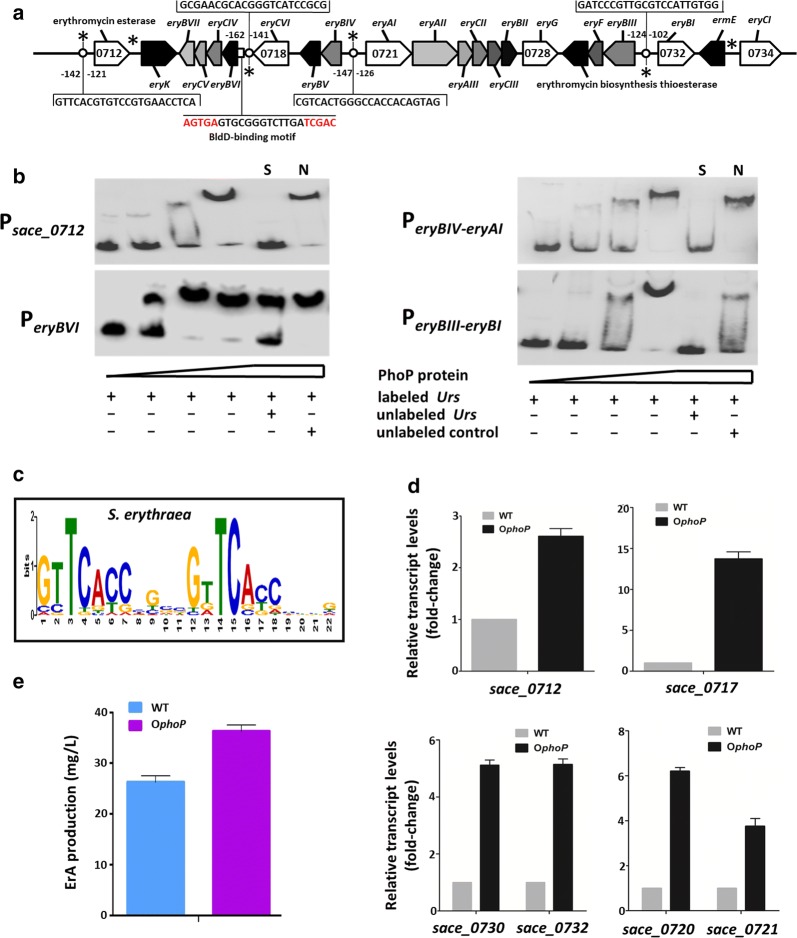

The organization of ery cluster was shown in Fig. 2a. There are six regulatory regions (marked with asterisk in Fig. 2a) in the ery cluster, including the promoter regions of sace_0712 gene, eryK gene, and operon eryBVI-BVII, as well as in the intergenic regions of eryBIV-eryAI, eryBIII-eryBI, and ermE-eryCI. In order to determine whether the PhoP protein binds directly to these regulatory regions of ery cluster, gradient EMSA assays were performed using purified His-PhoP protein. To verify the specificity of the binding, unlabeled specific probe (100-fold) or nonspecific competitor DNA (100-fold, salmon sperm DNA) was used. Obvious shift bands were observed in EMSA assays for sace_0712, eryBVI, eryBIV-eryAI, and eryBIII-eryBI following addition of His-PhoP (Fig. 2b). In S. erythraea, PhoP-binding motif (PHO-box) was identified [23]. The PHO-box is formed by two conserved direct repeats units (DRUs) of 11-nucleotides, with each one formed by an identical seven-nucleotide sequence (GtTCacc), followed by a four-nucleotide less-conserved tail region, and bound by a PhoP protein (Fig. 2c). Using MEME/MAST tools (http://meme.sdsc.edu) and the PREDetector software program, four putative PhoP-boxes were found in the regulatory regions of genes, including sace_0712 (two DRUs: GTTCACGTGTC CGTGAACCTCA), eryBVI (two DRUs: GCGAACGCACG GGTCATCCGCG), eryBIV-eryAI (two DRUs: CGTCACTGGGC CACCACAGTAG), and eryBIII-eryBI (two DRUs: GATCCCGTTGC GTCCATTGTGG) (Fig. 2a). The regulatory regions with the putative PhoP-boxes controlled six transcript units (Tus), sace_0712 gene, eryBVI operon (4 genes), eryBIV operon (3 genes), eryAI operon (7 genes), eryBIII operon (3 genes), eryBI gene. To further examine the regulatory effect of PhoP on transcription of ery genes in S. erythraea, we tried to construct phoP-deletion mutant and phoP overexpressed strain (OphoP). Regretfully, our attempts to delete phoP gene were unsuccessful. The OphoP and wild-type (WT) strains were grown at 30 °C in TSB media for 48 h. The overexpression of phoP resulted in a 2.5- to 14-fold (2.5-fold for sace_0712, 14-fold for eryBVI, fivefold for eryBIV, fivefold for eryAI, 6.2-fold for eryBI, and 3.7-fold for eryF of eryBIII operon) increase in induction of ery genes (Fig. 2d). These results demonstrated that PhoP exhibits a regulatory function as a transcriptional activator of ery cluster genes involved in biosynthesis of erythromycin by directly upregulating the expression of six TUs.

Fig. 2.

PhoP directly binds to promoter regions in ery genes cluster. a The cis-element analysis about the erythromycin biosynthetic gene cluster (ery). b EMSAs of His6-PhoP protein of S. erythraea with regulatory regions of sace_0712, eryBVI, eryBIV-eryAI, and eryBIII-eryBI; unlabeled specific probe (100-fold) (S) or nonspecific competitor DNA (100-fold, salmon sperm DNA) (N) was added. The concentrations of His6-PhoP protein in each lane from left to right was 0 µM, 0.2 µM, 0.4 µM, 0.8 µM, 0.8 µM, 0.8 µM. c The PHO box in S. erythraea. The height of each letter is proportional to the frequency of the base, and the height of the letter stack is the conservation in bits at that position. d The transcriptional profiles of ery genes in WT and PhoP-overexpressed strain (OphoP). The value for the transcription level in OphoP was a relative value compared to WT. e The ErA production of WT and OphoP strains in TSB medium for 3 days

To investigate the effect of PhoP on erythromycin production, the amount of erythromycin A (ErA) were determined in the OphoP and wild-type (WT) strains grown at 30 °C in TSB media for 3 days. We found that production of erythromycin in the OphoP strain increased by approximately 40% compared to the wild type strain (Fig. 2e).

The regulatory effect of nitrogen on erythromycin production is mediated by PhoP

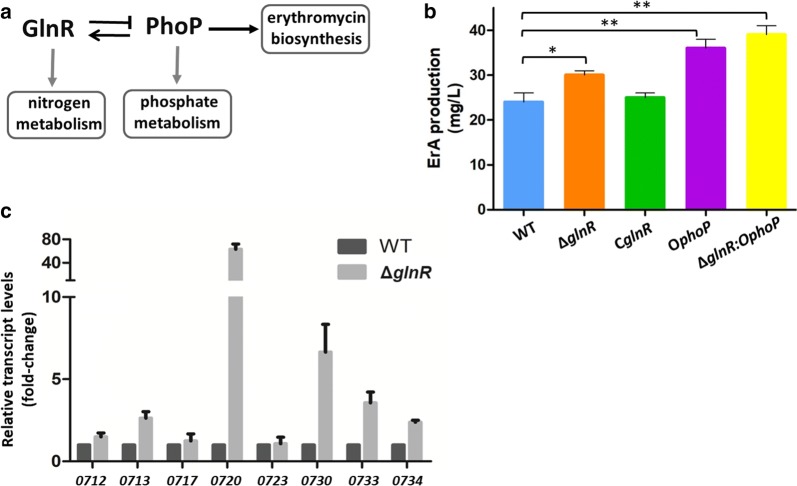

Nitrogen source and GlnR have a regulatory effect on the erythromycin production in S. erythraea [22]. However, it remains unclear how the GlnR-mediated nitrogen metabolism is connected to biosynthesis of erythromycin. No GlnR-binding motif was observed in the regulatory regions of ery cluster, indicating the effect of GlnR on erythromycin production was indirect. Our recent research demonstrated that S. erythraea revealed the reciprocal crosstalk between PhoP and GlnR: PhoP activated glnR transcription, whereas GlnR directly repressed phoP transcription [23], suggesting that the regulatory effect of nitrogen on erythromycin production may be mediated by PhoP (GlnR–PhoP-ery cascaded regulation) (Fig. 3a). As shown in Fig. 3b, when glnR was deleted, the titer of ErA increased to nearly 31 mg/L, nearly 23% higher than the value obtained in WT strain. The titer of ErA reversely reduced to the similar level with WT strain when the glnR was complemented to the null mutant (CglnR). ErA production of phoP-overexpressed ΔglnR (ΔglnR:OphoP) was further improved by 10% compared to the phoP-overexpressed strain (OphoP). To investigate the regulatory effects of GlnR on ery genes transcription in S. erythraea, the glnR-deleted mutant (ΔglnR) and wild type strain (WT) were cultivated in TSB media, cells harvested for RNA extraction at 72 h, and ery transcription analyzed using RT-PCR. Increases in transcription of most ery genes were observed in the ΔglnR mutant strain, indicating that ery cluster was repressed by GlnR (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

The regulatory effect of nitrogen on erythromycin production is mediated by PhoP. a GlnR–PhoP-ery cascaded regulation; b The ErA production of WT, ΔglnR, CglnR, OphoP, and ΔglnR:OphoP cultivated in TSB medium for 3 days. c The transcriptional profiles of ery cluster genes in WT and ΔglnR cultivated in TSB medium for 3 days. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

PhoP indirectly controls erythromycin biosynthesis by regulating the transcription of bldD

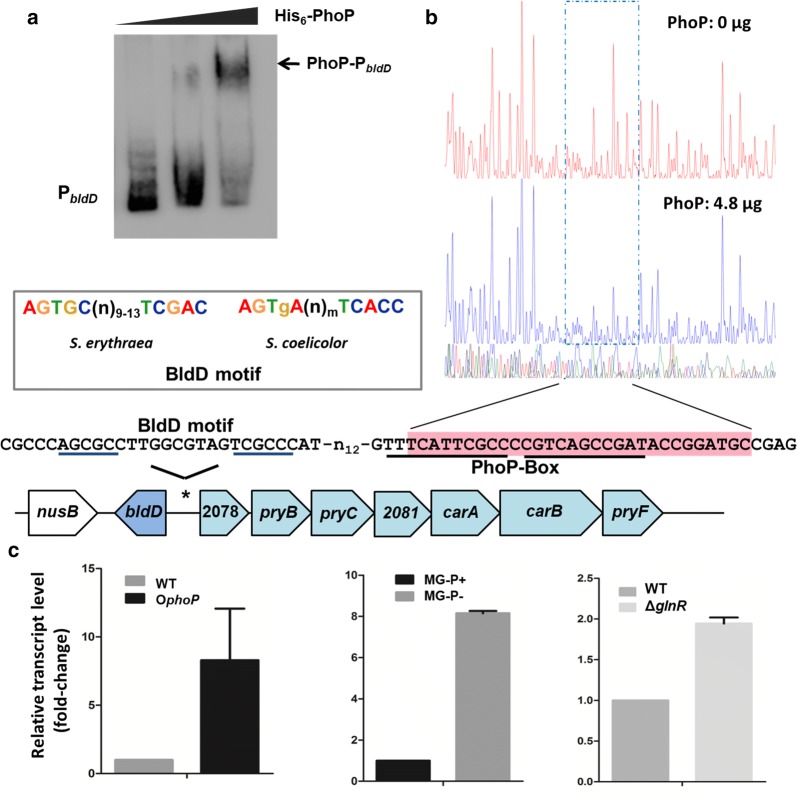

BldD, a key developmental regulator encoded by sace_2077, was found to be able to bind all the five main promoter regions in the ery cluster and promote erythromycin biosynthesis [2]. Interestingly, we found that PhoP bind directly to the promoter regions of bldD gene (Fig. 4a). To identify the exact DNA sequences that were protected by PhoP in the promoter region of bldD, a DNase I footprinting assay using purified recombinant His-PhoP and a fluorescent FAM-labeled probe was performed. With the addition of His-PhoP (4.8 μg), a clearly protected region of about 30 nt was detected (Fig. 4b). Within the protected region, the putative PhoP-box consisting of two PhoP-binding motif (TTTCATTCGCCCCGTCAGCCGAT) was observed. In S. erythraea the expression of bldD is controlled by BldD itself [2]. The putative BldD-binding site (AGCGC-n10-TCGCC) was identified in upstream of bldD gene; which was highly similar to the consensus AGTGC(n)9TCGAC and AGTgA(n)mTCACC (m = 0–16) deduced in S. erythraea and S. coelicolor [3]. BldD-binding site is located in close proximity to the PhoP-box (separated by 15 bp) (Fig. 4b). RT-PCR experiments showed that the overexpression of PhoP resulted in the induction of bldD (eightfold), indicating that PhoP activated bldD transcription (Fig. 4c). The transcriptional response of bldD gene in wild-type strain was investigated under high (10 mM, MG-P+) and low (40 μM, MG-P−) phosphate in MG medium. The bldD transcript level was significantly increased (about eightfold) in phosphate-limited medium (Fig. 4c). In addition, the ΔglnR strain also revealed twofold increase on transcription level of bldD. These observations suggested that PhoP indirectly controlled erythromycin biosynthesis by regulating the transcription of bldD.

Fig. 4.

PhoP regulates the transcription of bldD in S. erythraea. a Electrophoretic mobility shift assays of His-PhoP to promoter region of bldD by incubating the bio-labeled DNA with 1 µM protein and a 200-fold excess of nonspecific competitor DNA (sperm DNA). PbldD represented bio-labeled DNA sequence located in region from − 300 to + 50 of bldD gene. b The footprinting assay for promoter region of bldD with PhoP, and the pink solid rectangle refers to region protected by PhoP. Genetic organization of bldD and regulatory sequence were shown. The underline referred to the potential binding sites of BldD and PhoP. The consensus sequences of BldD binding motif in S. erythraea and S. coelicolor were shown inside the gray frame. c The transcriptional profiles of bldD gene in WT, glnR-deleted mutant (ΔglnR) and PhoP-overexpressed strain (OphoP). The transcriptional responses of bldD gene to high (MG-P+) and low (MG-P−) phosphate was also shown

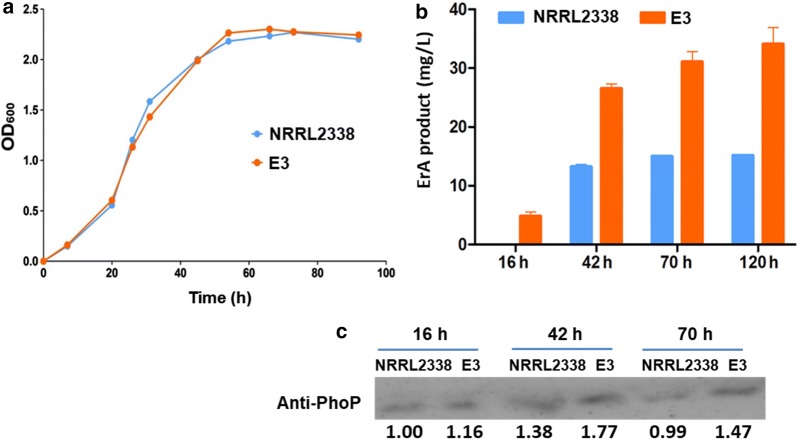

More PhoP protein was observed in high-yield S. erythraea strain

Finally, we examined the amount of PhoP protein in high-yield (HY) and low-yield (LY) strains of S. erythraea. An industrial S. erythraea strain E3 which has been widely used for erythromycin fermentation was employed as HY strain, while S. erythraea NRRL2338 as LY strain. Cultures of the LY and HY strains in a liquid, rich medium (TSB) were sampled at 16, 42, 70, and 120 h. The growth curves observed for HY and LY strains in TSB medium are presented in Fig. 5a. No change of growth in two strains was observed. Strain E3 produced erythromycin earlier (at 16 h) than strain NRRL2338, and yielded more erythromycin at each time point (Fig. 5b). We investigated the expression of PhoP in the HY and LY strains by using Western blots. Polyclonal anti-PhoP antibody detected PhoP in three lysates at 16 h, 42 h and 70 h which represented late lag phase, exponential growth phase, and stationary phase, respectively. The results demonstrated that high-yield strain contained higher abundance of PhoP than low-yield strain (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

High-yield S. erythraea strain contains higher abundance of PhoP protein. a The growth curves of high-yield strain E3 and low-yield strain NRRL2338 in TSB. b Titers of erythromycin of two strains in TSB. c Western blot of lysates (8 μg of total protein) of the E3 and NRRL2338 strains at 16 h, 42 h, and 70 h with polyclonal antibody for PhoP. The band intensities were quantified by densitometry using ImageJ software

Discussion

PhoP plays a key role in cross-talk of phosphate metabolism and erythromycin biosynthesis in S. erythraea

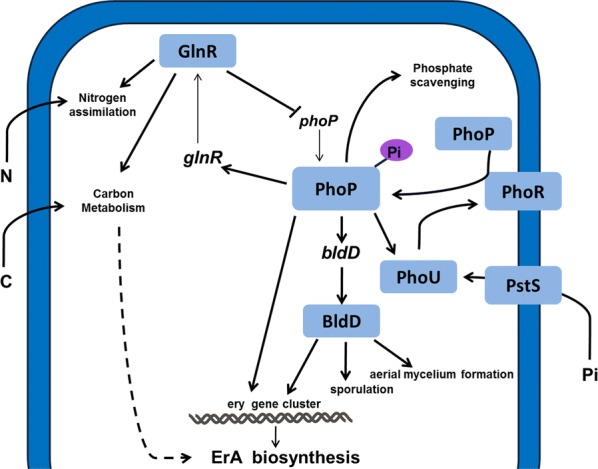

In the past decade, Martin group has proposed that PhoP plays a central role in primary and secondary metabolism in S. coelicolor. A complete nutrient-sensing signal transduction pathway, PhoP-AfsR-AfsS-SARP, was elucidated to demonstrate that the phosphate regulatory effect on secondary metabolism was exerted through interaction PhoP with AfsR and AfsS regulators [9]. However, the homologous gene for afsS was not observed in the S. erythraea genome and no pathway-specific SARP regulator was identified as being responsible for erythromycin biosynthesis. So far the signaling system of PhoP-AfsR-AfsS-ery, controlling expression of genes involved in secondary metabolism has not been found. In the present study, we demonstrated that the phosphate-sensing PhoP, as an activator, strongly and directly regulated six transcript units involved in erythromycin biosynthesis, including sace_0712 gene, eryBVI operon (4 genes), eryBIV operon (3 genes), eryAI operon (7 genes), eryBIII operon (3 genes), and eryBI gene. Most of ery cluster (19 genes of all 22 genes in ery cluster) were subject to regulation by PhoP, indicating that PhoP controlled biosynthetic cluster of erythromycin. Interestingly, PhoP directly also up-regulated the transcription of bldD, whose product was a key regulator of actinomycetes development and activated all genes of ery cluster [2]. Recent researches observed that overproducing strains showed lower expression level of bldD gene than wild-type strains, opposite to the ery genes [1, 5]. The regulatory effect of BldD on ery cluster remains still unclear. Phosphate limitation and overexpression of phoP increased the transcript levels of ery genes to enhance the erythromycin production. These observations demonstrated that PhoP exerted direct regulatory effect (PhoP-ery) or indirect regulatory effect mediated by BldD (PhoP-BldD-ery) on erythromycin biosynthesis. These findings revealed that PhoP played an important and central role in mediating the interplay between phosphate metabolism and secondary metabolism in S. erythraea by integrating phosphate signals to modulate the erythromycin biosynthesis (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The PhoP-mediated cross-talk of primary metabolism and erythromycin biosynthesis in S. erythraea. Thick arrows refer to positive regulation; the thin arrows refer to transcription; the lines ended by a perpendicular short line refer to negative regulation

On the other hand, BldD is a developmental transcription factor [2], and plays important roles in many diverse processes, sporulation, aerial mycelium formation, antibiotic production, and extracellular matrix in actinomycetes. Our data showed that PhoP directly activates expression of BldD, indicating that PhoP has an extensive function on many facets of the biological process, such as morphological differentiation and development, beyond the primary and secondary metabolisms.

PhoP mediates the regulatory effects of nutrients on erythromycin production in S. erythraea

The biosynthesis of erythromycin is also highly regulated by type and concentration of the nitrogen and carbon sources. However, not much is known on the actual mechanisms behind the observed effects on antibiotic formation, e.g. what the molecular mechanism is that underlies repression at high ammonia concentrations. In our previous studies we had identified phosphate regulator PhoP and nitrogen regulator GlnR in S. erythraea, and showed that PhoP and GlnR both collaboratively regulate the transcription of glnR and some nitrogen metabolism-related genes. Meanwhile, GlnR negatively controlled phosphate metabolism through its binding to the promoter of phoP-phoR, indicating that the two global regulators played reciprocal regulatory roles associated with nitrogen and phosphate metabolism in S. erythraea [22, 23]. More interestingly, GlnR directly regulated the transcription of three genes (gltA-2, citA, and citA4) which encode citrate synthase as the first enzyme of the TCA cycle. Acetyl-CoA is fed into the TCA cycle by citrate synthase, providing succinyl-CoA which can be converted to methymalonyl-CoA and propionyl-CoA as important precursors for erythromycin biosynthesis [7]. More recently, we found that GlnR regulates uptake and utilization of ABC-transported carbohydrates in actinomycetes, demonstrating that GlnR serves a role beyond nitrogen metabolism, and mediates critical functions in carbon metabolism and crosstalk of nitrogen- and carbon-metabolism pathways [6]. Taken together, nitrogen/carbon signals exert the regulatory effect on the erythromycin biosynthesis through GlnR negatively regulating the transcription of phoP gene (Fig. 6). It seems that the regulatory mechanism of erythromycin biosynthesis is much more complicated than expected, involving three global regulators (GlnR, PhoP, and BldD).

In conclusion, we found that phosphate-sensing regulator PhoP directly and indirectly activates the biosynthesis of erythromycin at the transcriptional level in S. erythraea. PhoP is well-positioned to link the nutritional status of the cell to the regulation of erythromycin production. These findings indicated a possible GlnR–PhoP–BldD-ery regulatory network in coordinating the primary nutrient metabolism and erythromycin biosynthesis responding to the nitrogen/phosphate sources availability, here provide a starting point for understanding the complex regulation of erythromycin biosynthesis. Our study reveals a molecular mechanism underlying the antibiotics production, and suggests new possibilities for designing new strategies for strain improvement and fermentation optimization strategies for increasing antibiotics yield.

Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The seeds of S. erythraea strains were grown on agar plates of the medium [10 g cornstarch, 10 g corn steep liquor, 3 g NaCl, 3 g (NH4)2SO4, 2 g CaCO3, and 20 g agar per liter of distilled H2O, pH 7.2] at 30 °C for sporulation. E. coli strains were grown at 37 °C in liquid or onto solid LB medium. All media were sterilized by autoclaving at 121 °C for 30 min. The EVANS and TSB media were described as the literatures [22, 23].

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain/plasmids | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. erythraea NRRL2338 | Used as parental strain, wild type | DSM 40517 |

| E. coli DH5α | F−Ø80d lacZΔM (lacZYA -argF)U169 deoR | Invitrogen |

| E. coli BL21(DE3)-6965 | The strain for expression of PhoP | This report |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | F′ompTr-Bm-B(λDE3) | This report |

| S. erythraea OphoP | The strain for over-expression of phoP, NRRL2338 integrated with pIB139-6965 | This report |

| S. erythraea ∆glnR | NRRL2338 glnR::tsr (glnR null mutant) | This report |

| S. erythraea CglnR | glnR complementary strain, ∆glnR carrying pIB-glnR | This report |

| S. erythraea ∆glnR: OphoP | The strain for over-expression of phoP, ∆glnR integrated with pIB139-6965 | This report |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET28a | Expression vector | Novagen |

| P6965 | pET28a derivative carrying phoP of S. erythraea | This report |

| pIB139 | Escherichia coli–S. erythraea integrative shuttle vector containing a strong constitutive | [20] |

| pIB139-6965 | pIB139 carrying an extra phoP for the gene overexpression | This report |

| pIB-glnR | pIB139 carrying an extra glnR for the gene overexpression | This report |

Overexpression and purification of PhoP protein

Escherichia coli cells transformed with p6965 plasmid, E. coli BL21 (DE3)-6965, were grown in LB medium at 37 °C in an orbital shaker (250 rpm.) to an OD600 of 0.6. The expression of phoP was induced by IPTG addition (0.1 mM final concentration) for 6–8 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice with PBS buffer (pH 8.0) and broken by ultrasonic cell crusher. Cell debris and membrane fractions were separated from the soluble fraction by centrifugation (45 min; 15,000 rpm; 4 °C). His-tagged PhoP (His6-PhoP) was purified by Ni–NTA Superflow columns (Qiagen, Germany). The protein presented a maximal peak of elution at around 250 mM imidazole (in 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, pH 8.0). Fractions containing His6-PhoP were pooled and dialyzed in Buffer D (50 mM Tris, 0.5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 20% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, pH 8.0) at 4 °C and stored at − 80 °C. The purified His6-PhoP protein was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Protein concentration was determined with BCA Protein Assay Kit with BSA as the standard.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

The putative promoter regions of the ery cluster genes and bldD gene (the upstream 350 bp from about − 300 to 50) were amplified by PCR using the primers listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. PCR products were labeled with biotin using a universal biotinylated primer (5′ biotin-AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG 3′). The biotin-labeled PCR products were identified by agarose gel electrophoresis and purified using a PCR Purification kit (Shanghai Generay Biotech Co., Ltd) as EMSA probes. The concentrations were determined with a microplate reader (Biotek, USA). EMSAs were carried out using a Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The binding reaction contained 10 mM Tris∙HCl pH 8.0, 25 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 0.01% Nonidet P40, 50 μg/mL poly[d(I-C)], 10% glycerol. Biotin-labeled DNA probes were incubated individually with varying amounts of PhoP protein at 25 °C for 20 min. For control groups, unlabeled specific probe (200-fold) or nonspecific competitor DNA (200-fold, sonicated salmon sperm DNA) was used. After binding, the samples are separated on a native PAGE gel in ice-bathed 0.5× Tris–borate-EDTA at 100 V and bands are detected by BeyoECL Plus. The amount of all DNA probes used in EMSA was about 1 pmol, and the protein’ amount was approximately 50 pmol.

Computional analysis

The MEME/MAST tools (http://meme.sdsc.edu) and the PREDetector software program were used to search GlnR/PhoP binding motif binding sites in the upstream region of ery genes in S. erythraea. The operon prediction of ery cluster genes and bldD was performed with MicrobesOnline database (http://www.microbesonline.org/operons/).

DNase I footprinting assay

The promoter region of bldD was PCR amplified with primers P2077F and P2077R (Additional file 1: Table S1), and the amplicon was cloned into the T-vector pUC18B-T (Shanghai Biotechnology Corporation, SBC). The obtained plasmids were used as templates for further preparation of biotin-labeled probes with universal primer primers bio-Tprimer (Additional file 1: Table S1). After agarose gel electrophoresis, the FAM-labeled probes were purified using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) and quantified with a NanoDrop 2000C (Thermo, USA). For each assay, 200 ng of each probe was incubated with different amounts of His-PhoP in a total volume of 40 µL in EMSA buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology, China). After incubation for 30 min at 25 °C, 10 µL of solution containing about 0.015 units DNase I (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and 100 nM freshly prepared CaCl2 was added, and the sample was further incubated for 1 min at 25 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding 140 µL DNase I stop solution (200 mM unbuffered sodium acetate, 30 mM EDTA, and 0.15% SDS). Samples were extracted with phenol/chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. The pellets were dissolved in 30 µL Milli-Q water. The preparation of the DNA ladder, electrophoresis, and data analysis were performed as previously described [19], except that the GeneScan-LIZ500 size standard (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used.

RNA preparation and real-time RT-PCR

Saccharopolyspora erythraea was grown for 2 days at 30 °C in seed medium. Next, 0.5 mL of the preculture was used to inoculate the TSB medium or modified Evans medium (30 mL). Samples were collected at different time points. Cell pellets were collected after 20 min of centrifugation at 3000 rpm. Total RNA was prepared using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The RNA integrality was analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and the RNA concentration was determined by microplate reader (BioTek, USA). Total RNA (1 μg) extracted from liquid cultures was reverse transcribed using a PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Shiga, Japan) for real-time RT-PCR, the DNase digestion was performed to remove genomic DNA before reverse transcription for 5 min at 42 °C. All procedures above are following the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR reactions were performed with primers listed in Additional file 1: Table S2. SYBR premix Ex Taq™ GC Kit (Perfect Real Time, Takara) was used for real-time RT-PCR, and about 100 ng cDNA was added in 20 μL volume of PCR reaction. The PCR was conducted using CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, USA) and the PCR conditions were 95 °C for 5 min; then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 60–64 °C for 30 s; and an extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

Erythromycin determination by HPLC

The high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) condition was as follows: mobile phase [(50 mM K2HPO4; pH 8.0): acetonitrile 50:50], detection wavelength (210 nm, UV–VIS SPD-20A, Shimadzu), chromatographic column (5 μm Inertsil ODS-SP, 4.6 × 250 mm, Shimadzu), and rate (0.8 mL/min). The fermentation samples were prepared by lyophilization and the following methanol-dissolving.

Western blot

The protein concentrations of the samples were determined using BCA Protein Assay Kit (TIANGEN) with BSA as the standard. Protein samples extracted by ultrasonication were separated by SDS–PAGE and then transferred to a PVDF membrane for 30 min at 100 V. The membrane was blocked at 24° C in 1× TBST (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20) containing 5% non-fat dry milk (NFDM) for 2 h. Then Anti-PhoP antibody diluted 1:15,000 in TBST/0.5%NFDM was used. After incubation at 4 °C for overnight, the blot was washed with TBST for 3 times. The membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1 μg/mL in TBST with 3% BSA) at ambient temperature for 2 h. The ECL system (CTB, USA) was used for signal detection according to the manufacturer in conjunction with a luminescent image analyzer, Bio-Imaging Systems (DNR Bio-Imaging Systems, ISRAEL).

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. The primers used for amplification of gene upstream regions in EMSAs. Table S2. The primers used in RT-qPCR.

Authors’ contributions

YX, L-LY, and B-CY designed research; YX, L-LY performed research; DY, XC and L-LY analyzed data; L-LY and B-CY wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFA0900404) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31730004).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ya Xu and Di You—co-first authors

Contributor Information

Ya Xu, Email: yokixu77@163.com.

Di You, Email: 030111115@mail.ecust.edu.cn.

Li-li Yao, Email: yaolili@mail.ecust.edu.cn.

Xiaohe Chu, Email: chuxhe@163.com.

Bang-Ce Ye, Email: bcye@ecust.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12934-019-1258-y.

References

- 1.Carata E, Peano C, Tredici SM, Ferrari F, Talà A, Corti G, Bicciato S, De Bellis G, Alifano P. Phenotypes and gene expression profiles of Saccharopolyspora erythraea rifampicin-resistant (rif) mutants affected in erythromycin production. Microb Cell Fact. 2009;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chng C, Lum AM, Vroom JA, Kao CM. A key developmental regulator controls the synthesis of the antibiotic erythromycin in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11346–11351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803622105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliot MA, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Leskiw BK. BldD is a direct regulator of key developmental genes in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:257–269. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.García R, Sola-Landa A, Martín JF. Phosphate control over nitrogen metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor: direct and indirect negative control of glnR, glnA, glnII and amtB expression by the response regulator PhoP. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3230–3242. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li YY, Chang X, Yu WB, Li H, Ye ZQ, Yu H, Liu BH, Zhang Y, Zhang SL, Ye BC, Li YX. Systems perspectives on erythromycin biosynthesis by comparative genomic and transcriptomic analyses of S. erythraea E3 and NRRL23338 strains. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:523. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao CH, Yao LL, Xu Y, Liu WB, Zhou Y, Ye BC. Nitrogen regulator GlnR controls uptake and utilization of non-phosphotransferase-system carbon sources in actinomycetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:15630–15635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508465112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao CH, Yao LL, Ye BC. Three genes encoding citrate synthases in Saccharopolyspora erythraea are regulated by the global nutrient-sensing regulators GlnR, DasR, and CRP. Mol Microbiol. 2014;94:1065–1084. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu G, Chater KF, Chandra G, Niu G, Tan H. Molecular regulation of antibiotic biosynthesis in streptomyces. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77(1):112–143. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00054-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin JF, Sola-Landa A, Santos-Beneit F, Fernandez-Martinez LT, Prieto C, Rodriguez-Garcia A. Cross-talk of global nutritional regulators in the control of primary and secondary metabolism in Streptomyces. Microb Biotechnol. 2011;4(2):165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendes MV, Tunca S, Anton N, Recio E, Sola-Landa A, Aparicio JF, Martin JF. The two-component phoR–phoP system of Streptomyces natalensis: inactivation or deletion of phoP reduces the negative phosphate regulation of pimaricin biosynthesis. Metab Eng. 2007;9:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pullan ST, Chandra G, Bibb MJ, Merrick M. Genome-wide analysis of the role of GlnR in Streptomyces venezuelae provides new insights into global nitrogen regulation in actinomycetes. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:175. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reeve LM, Baumberg S. Physisological controls of erythromycin production by Saccharopolyspora erythraea are exerted at least in part at the level of transcription. Biotechnol Lett. 1998;20:585–589. doi: 10.1023/A:1005357930000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rokem JS, Lantz AE, Nielsen J. Systems biology of antibiotic production by microorganisms. Nat Prod Rep. 2007;24(6):1262–1287. doi: 10.1039/b617765b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos-Beneit F, Rodríguez-García A, Martín JF. Overlapping binding of PhoP and AfsR to the promoter region of glnR in Streptomyces coelicolor. Microbiol Res. 2012;167:532–535. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sola-Landa A, Moura RS, Martín JF. The two-component PhoR–PhoP system controls both primary metabolism and secondary metabolite biosynthesis in Streptomyces lividans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(10):6133–6138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931429100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sola-Landa A, Rodrıguez-Garcıa A, Amin R, Wohlleben W, Martın JF. Competition between the GlnR and PhoP regulators for the glnA and amtB promoters in Streptomyces coelicolor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:1767–1782. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiffert Y, Supra P, Wurm R, Wohlleben W, Wagner R, Reuther J. The Streptomyce scoelicolor GlnR regulon: identification of new GlnR targets and evidence for a central role of GlnR in nitrogen metabolism in actinomycetes. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:861–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Wezel GP, McDowall KJ. The regulation of the secondary metabolism of Streptomyces: new links and experimental advances. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;28(7):1311–1333. doi: 10.1039/c1np00003a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Cen XF, Zhao GP, Wang J. Characterization of a new GlnR binding box in the promoter of amtB in Streptomyces coelicolor inferred a PhoP/GlnR competitive binding mechanism for transcriptional regulation of amtB. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:5237–5244. doi: 10.1128/JB.00989-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkinson CJ, Hughes-Thomas ZA, Martin CJ, Böhm I, Mironenko T, Deacon M, Wheatcroft M, Wirtz G, Staunton J, Leadlay PF. Increasing the efficiency of heterologous promoters in Actinomycetes. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;4:417–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu Y, Li YX, Ye BC. Lysine propionylation modulates the transcriptional activity of phosphate regulator PhoP in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Mol Microbiol. 2018;110:648–661. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao LL, Liao CH, Huang G, Zhou Y, Rigali S, Zhang B, Ye BC. GlnR-mediated regulation of nitrogen metabolism in the actinomycete Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2014;98:7935–7948. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5878-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yao LL, Ye BC. The reciprocal regulation of GlnR and PhoP in response to nitrogen and phosphate limitations in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Appl Environ Microb. 2016;82:409–420. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02960-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu H, Yao Y, Liu Y, Jiao R, Jiang W, Zhao G-P. A complex role of Amycolatopsis mediterranei GlnR in nitrogen metabolism and related antibiotics production. Arch Microbiol. 2007;188:89–96. doi: 10.1007/s00203-007-0228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. The primers used for amplification of gene upstream regions in EMSAs. Table S2. The primers used in RT-qPCR.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.