Abstract

A method for isolation of exosomes from tumor cell supernatants or cancer patients’ plasma is presented. Tumor-derived exosomes (TEX) are defined as a subset of extracellular vesicles (EVs) sized at 30–150nm and originating from multivesicular bodies (MVBs). The method utilizes size exclusion chromatography (SEC) for recovery of exosomes from cell line supernatants or cancer patients’ plasma. The recovered exosomes are morphologically intact, aggregate-free and functionally competent. Their molecular content parallels that of the parent tumor cells, and they carry various immunoregulatory ligands known to modulate functions of immune cells. All exosomes isolated from tumor cell lines are TEX, while those isolated from plasma of cancer patients have to be fractionated into TEX and non-TEX. Mini-SEC allows for exosome isolation and recovery in quantities sufficient for molecular profiling, functional studies and, in case of plasma, for further fractionation into TEX and non-TEX. The mini-SEC method can also be used for comparative studies of the exosome content in serial specimens of cancer patients’ body fluids.

Keywords: exosomes, TEX, exosome isolation, size exclusion chromatography

Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are produced by all cells. EVs vary in origins, size and molecular cargos they transport. Exosomes are a subset of small EVs (30–150nm in diameter) formed by membrane invaginations in multivesicular bodies (MVBs) of parent cells. Exosomes are released upon fusion of an MVB with the cell surface membrane as spherical membrane-bound vesicles that circulate freely and are found in all body fluids (Hessvik and Llorente, 2018). They carry a rich cargo of proteins, lipids, glycans and nucleic acids and mediate intercellular communication (Milane et al., 2015). Tumor cells produce and release large quantities of exosomes into the tumor microenvironment (TME). Hypoxia, low pH and elevated metabolic activity characterizing the TME favor exosome production and release (Ludwig et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2011). The molecular/genetic cargo of tumor-derived exosomes (TEX) acquired and packaged in the endocytic compartment of the tumor cell resembles or mimics that of the parental cell (Kucharzewska et al., 2013). Molecularly and topographically, TEX are miniature approximations of the paternal tumor cells. It is because of this similarity to parent tumor cells that TEX have become potentially promising candidates for a “liquid biopsy.” The possibility of using circulating TEX in place of tumor itself for cancer diagnosis, prognosis or evaluating responses to cancer therapy has generated enormous interest and initiated efforts for testing and validating the use of exosomes as a liquid biopsy.

The SEC method we describe and call “mini-SEC” has been extensively used for TEX studies in our laboratory. It lends itself well to a high-throughput, inexpensive and time-sensitive testing of numerous small volumes (1mL) of pre-cleared supernatant or plasma samples delivered to short (10 cm) SEC columns set up in a row on the bench and eluted in tandem with PBS at pH7.0. Exosomes are recovered in the void volume and undergo extensive characterization to determine their protein content, morphology, numbers of exosomes, concentration, and the composition of their molecular cargos. The method allows for a rapid (20 min), reliable and reproducible recovery of non-aggregated, morphologically-intact, and functionally-competent exosomes. The yield of exosomes recovered from cancer patient’s plasma ranges from (60–120µg protein/mL plasma and is sufficient for subsequent studies of their protein or miRNA contents.

Basic Protocol 1: Isolation of tumor-derived exosomes (TEX) from culture supernatants

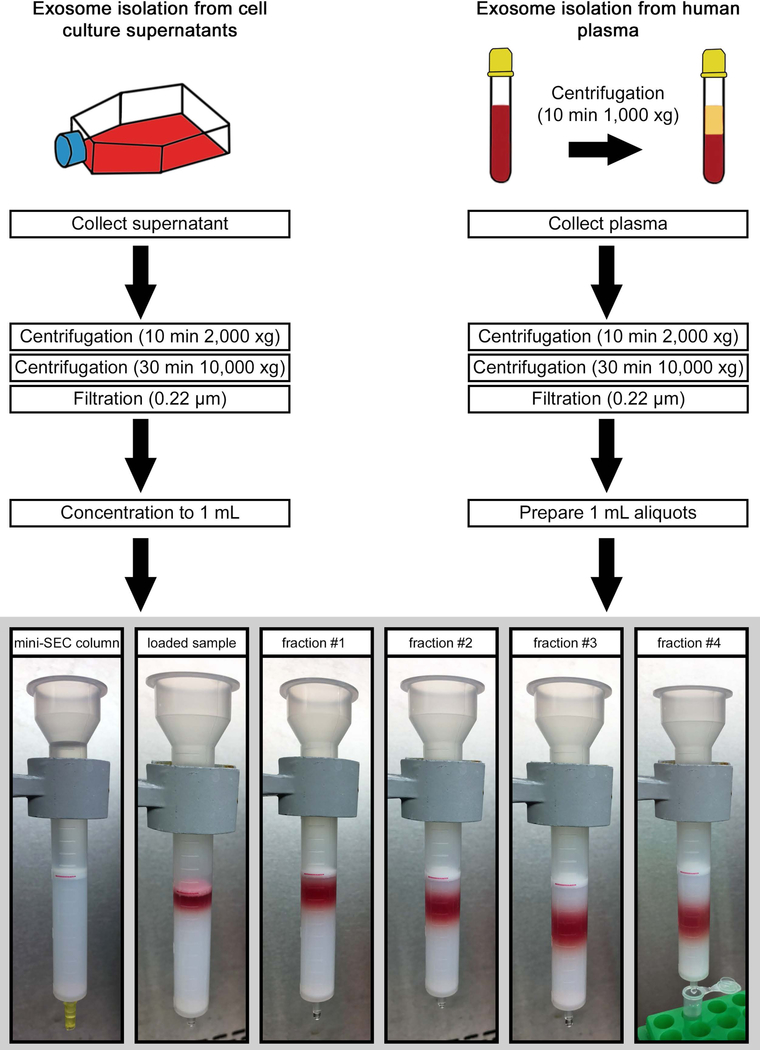

This protocol describes a series of procedures necessary for isolation of exosomes from supernatants of tumor cell lines or from plasma of cancer patients. Exosomes isolated from supernatants are TEX, while those isolated from plasma or other body fluids are mixtures of exosomes derived from a variety of normal cells but are enriched in TEX (Ludwig et al., 2019; Theodoraki et al., 2018). The protocol starts with methods describing the harvesting of tumor cell supernatants, followed by the pre-clearing of supernatants aimed at the removal of cell debris, apoptotic bodies and large microvesicles. The subsequent filtration step further clarifies the supernatant for SEC by removing bacteria, mitochondrial fragments and larger EVs as previously reported (Muller et al., 2014). Aliquots of pre-cleared supernatants are delivered to the column and exosomes are eluted with PBS. The experimental set up is described step by step in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2:

Schema and experimental set up for isolation of exosomes from supernatants or plasma. The red line is added for visual orientation and marks the 10mL mark of the column which equates 6cm of column height. Column is filled with 10 ml of Sepharose 2B with an additional 30µm filter added on top. 1 mL aliquot of pre-cleared and concentrated supernatant is loaded, followed by elution with PBS. 1 mL fractions are collected. For this size/diameter column, fraction #4 is enriched in exosomes and is collected in a microcentrifuge tube.

Materials List

Cell lines

- Human or murine tumor cell lines used for exosome studies should be authenticated to confirm their cellular origin. They have to be Mycoplasma negative. The following cell lines have been used in experiments described in this manuscript.

- UMSCC47 human HPV(+) head and neck cancer cells (obtained from Dr. Thomas Carey; University of Michigan Cancer Center)

- PCI-13 HPV(−) human head and neck cancer cells (established and maintained in our laboratory)

- Mel526 human metastatic melanoma cells (obtained from Walter J. Storkus; Department of Immunology, University of Pittsburgh)

- U-251 human glioblastoma cells (Sigma # 09063001)

- SVEC4-10 murine lymphendothelial cells (ATCC® CRL-2181)

RPMI-1640 Medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, cat. # R0883)

Corning™ Regular Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, cat. # MT35011CV)

Penicillin Streptomycin Solution (Corning, Corning, NY, USA, cat. # 30-002-CI)

TrypLE™ Express Enzyme (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. # 12605036)

Ethanol 200 Proof (Decon Labs, Inc., King of Prussia, PA, USA, cat. # 2701)

Lonza™ BioWhittaker™ Phosphate Buffered Solution (PBS) (Lonza Inc., Williamsport, PA, cat. # BW17-516F)

Exosome-depleted fetal bovine serum (FBS - See Reagents and Solutions)

Culture medium (See Reagents and Solutions) Sterile filtered base medium supplemented with 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin and 10% (v/v) exosome-depleted and heat-inactivated FBS

Sepharose (See Reagents and Solutions)

Equipment

Millex 0.22 µm sterile syringe filter units (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, cat. # SLGP033RS)

BD Syringes, 60 mL (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA, cat. # 309653)

Vivacell 100 concentrators (100,000 MWCO, Sartorius, Stonehouse, UK, cat. # VC1042)

Vivacell 20 concentrators (100,000 MWCO, Sartorius, cat. # VC2042)

Econo-Pac® Chromatography Columns (20mL bed volume, 1.5×12cm; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA, cat. # 7321010)

1.5 mL Fisherbrand™ Premium Microcentrifuge Tubes (Fisher Scientific, cat. # 05-408-129)

Nalgene™ Rapid-Flow™ Sterile Disposable Filter Units with PES Membrane (Fisher Scientific, cat. # 09-741-02)

Eisco Premium Lab Metalware Set (Fisher Scientific, cat. # 501042880)

Falcon™ 50 mL Conical Centrifuge Tubes (Fisher Scientific, cat. # 14-432-22)

Falcon™ 15 mL Conical Centrifuge Tubes (Fisher Scientific, cat. # 14-959-70C)

150 cm2 BD Falcon™ Tissue Culture Treated Flasks (Fisher Scientific, cat. # 08-772-48)

Optima™ L-100 XP Ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA)

Sorvall™ Legend RT Centrifuge (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

Sorvall™ LYNX 6000 Superspeed Centrifuge (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

Protocol steps

-

1

Seeding protocol

-

2

Culture 2.5 × 106 UMSCC47 cells in 150cm2 cell culture flasks using 25mL of DMEM supplemented with 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin and 10% (v/v) exosome-depleted and heat-inactivated FBS at 37°C and in the atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air

-

3

For exosome isolation, adjust the number of seeded cells to reach confluency after approximately 36h of cultivation. The cells are therefore 50% subconfluent and 50% confluent within the 72h period of cultivation. Details were recently published by our group (Ludwig et al., 2019). The seeding is cell line-dependent; for most common cancer cell lines between 2.5 × 106 and 4 × 106 of seeded cells works best.

Collection and pre-clearing of tumor cell supernatants

-

4

Collect cell culture supernatant in a 50mL falcon tube at 72h after seeding

-

5

Centrifuge cell culture supernatant at room temperature (RT) for 10min at 2000 x g (removal of cell debris and larger apoptotic bodies)

-

6

Transfer supernatant to a new falcon tube and spin at 4°C for 30min at 10,000 x g (removal of large microvesicles and smaller apoptotic bodies)

-

7

Filtrate supernatant using a 50mL syringe and a 0.22µm bacterial filter (removal of smaller microvesicles in the size of 200–500nm)

NOTE: Supernatants can be stored overnight at 4°C. Centrifugation and filtration should be performed before storage.

-

8

Concentrate 25mL aliquots of supernatants to 1mL by using Vivacell 100 concentrators at 2,000xg in preparation for mini-SEC purification.

NOTE: Alternatively, instead of Vivacell 100 concentrators, Vivaspin 20 columns can be used. The column volume is only 20mL, and they are, therefore, suitable for smaller volumes of supernatants. Larger supernatant volumes can be concentrated by Vivaspin 20 by constantly adding the supernatant during the spinning process.

HINT: Spin columns can be used up to five times by adding 10mL of 70% ethanol after concentrating the sample and spinning at 2000xg for 10min. Pipet ethanol up and down to clean the membrane of the column. Remove ethanol and add 50mL of PBS in the upper compartment and fill the lower compartment with water. Store spin columns at 4°C. After first usage, the membranes of the columns should not get dry at any time.

-

9

Mini-SEC

9. Prepare home-made Econo-Pac® Chromatography Columns by marking the 10mL scale with a marker and removing the cap from the lower side of the column.

NOTE: Alternatives to the columns used in this protocol are commercially available from different companies. It is possible to reproduce the results presented in this communication using a different column type, but re-optimization of the procedure is required. The re-optimization includes the characterization of exosomes in various fractions to subsequently identify the fraction which is most highly enriched in exosomes.

-

10

Mount the column onto a rack above a 50mL falcon tube used as a waste container.

Sepharose settles down when stored. Swirl Sepharose to get a homogenous mix.

-

11

Add Sepharose to the column up to the 10 mL mark.

Keep the volume of added Sepharose at the 10mL mark by continuously adding the Sepharose suspension. Close the opening of the column with a stopper as soon the settled Sepharose reaches 10mL level. This is a critical step. The exosome preparation is highly dependent on the quality of the column bed. It is mandatory to avoid air bubbles in the column bed. Building up the column slowly ensures a homogenous distribution of Sepharose beads in the column.

-

12

Once the column is complete, carefully place the porous frit on top using tweezers

-

13

Flush the column gently by adding 10mL of PBS and wait until it stops dripping

NOTE: During the isolation process, the mini-SEC column should not get dry. We recommend performing the mini-SEC steps soon after column preparation.

-

14

Place 1mL of the concentrated supernatant on the mini-SEC column and wait until it stops dripping

-

15

Add 1mL of PBS to the column to elute fraction #1. When it stops dripping, add another 1mL of PBS to elute fraction #2. Repeat this one more time to elute fraction #3. (These are “waste” fractions.)

-

16

Replace waste container by a 1.5mL microcentrifuge tube and harvest fraction #4 by adding another 1mL of PBS. Fraction #4 is enriched in exosomes.

Completion of this procotol results in TEX isolated from cell culture supernatants. The recovered TEX are non-aggregated and show the typical vesicular morphology, as illustrated in Fig. 3B. The size of TEX ranges from 30–150nm (Fig. 3C). Fraction #4 contains approximately 100μg of protein, depending on a tumor cell line. However, samples isolated from non-malignant cell lines generally contain less protein (Fig. 3A). The molecular cargo of the recovered TEX reflects the cargo composition of the parent cells. Fig. 3D and E show the similarities between TEX and their parent cells by comparing their content of pro-angiogenic markers. TEX isolated by mini-SEC are functionally competent as seen in co-incubation assays with Jurkat cells. TEX stimulated apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3F). Functional studies are described in detail in Supporting Protocol 2.

Fig. 3:

Characterization of TEX derived from cell culture supernatants. (A) The yield of exosomes in fraction #4 was measured by using a BCA protein assay (See Supporting Protocol 1). Total exosomal protein (µg) in fraction #4 was found to be higher for exosomes derived from cancer cell lines (grey bars) compared to exosomes derived from normal cells (white bars). Values are expressed as means ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. (B) TEM image of isolated and negatively-stained PCI-13-derived exosomes. (C) Size distribution of PCI-13-derived exosomes measured by qNano according to Supporting Protocol 1. (D) The angiogenesis antibody arrays (Supporting Protocol 1) show comparative protein analysis of UMSCC47 cell lysate (200µg protein; upper array) and exosomes produced by UMSCC47 cells (200µg protein; lower array) (E) Quantification of the arrays shown in D using ImageJ. (F) TEX-induced apoptosis of CD8+ Jurkat cells. Data from experiments in which CD8+ Jurkat cells were co-incubated with increasing protein levels of TEX isolated from supernatants of U251 cells (See Supporting Protocol 2). Values are expressed as means ± SEM. (Figures 3D and E originally appeared in Ludwig N, Yerneni SS, Razzo BM, Whiteside TL. Exosomes from HNSCC Promote Angiogenesis through Reprogramming of Endothelial Cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16(11):1798–808.)

Basic Protocol 2: Isolation of TEX-enriched exosomes from plasma samples

Mini-SEC can be adapted to operate as a rapid method for isolation of exosomes from larger volumes of human plasma. The pre-clearing steps are the same as those used for the isolation of exosomes from cell culture supernatants. The same mini-SEC-based separation will be used for the isolation of exosomes from plasma samples, which ensures the comparability of supernatant- and plasma-derived exosomes.

Materials List

Plasma of cancer patients: Peripheral venous blood samples were collected from patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Blood specimen from normal donors served as control. Informed consent from all individuals was obtained and the study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Pittsburgh (IRB # 991206). The blood samples were delivered to the laboratory and processed as described below.

Equipment

Falcon™ 50 mL Conical Centrifuge Tubes (Fisher Scientific, cat. # 14-432-22)

Millex 0.22 µm sterile syringe filter units (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, cat. # SLGP033RS)

BD Syringes, 3 mL (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA, cat. # 309657)

1.5 mL Fisherbrand™ Premium Microcentrifuge Tubes (Fisher Scientific, cat. # 05-408-129)

Centrifuge 5415 D (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany)

Protocol steps

Processing and pre-clearing of blood samples

-

1

Centrifuge peripheral venous blood samples at 1,000xg for 10min at RT and separate the plasma from blood components

-

2

Centrifuge plasma at RT for 10min at 2000xg

-

3

Transfer supernatant to a new tube and spin at 4°C for 30min at 10,000xg

-

4

Filter the supernatant using a 0.22µm bacterial filter

NOTE: Either fresh or frozen plasma can be utilized for exosome isolation. Frozen 1mL plasma aliquots can be stored at −80°C or lower.

Mini-SEC

-

5

Prepare columns as described above (9) and load 1mL of pre-cleared plasma on the column. Proceed as described for exosome isolation from cell culture supernatants.

Completion of Basic Protocol 2 results in the purification of exosomes from plasma samples. As described above for exosomes derived from cell line supernatants, plasma-derived exosomes isolated by mini-SEC show typical vesicular morphology. Cancer patient derived exosomes (Pt1 – Pt4) are enriched in immunosuppressive proteins compared to exosomes from normal donors (NC) (Fig. 4C) and suppress proliferation of CD4+ T cells in vitro (Fig. 4D) and induce apoptosis of activated CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4E). The vesicles recovered in fractions #3 may be larger than 150nm and those in fraction 5 tend to aggregate, as shown in Fig. 4A. Exosomes in fraction #4 are non-aggregated and contain relatively few “contaminating” plasma proteins. Characterization of exosomes and functional studies which are presented in Fig. 4 are described in detail in Support Protocol 1 and 2.

Fig. 4:

Characterization of TEX derived from plasma of cancer patients. (A) TEM of fractions #3, #4, and #5 recovered after miniSEC of plasma obtained from a patient with AML. (B) Protein contents in fractions recovered after SEC. An aliquot (50μL) of each fraction was separated by SDS-PAGE gels, stained with Coomassie blue and analyzed by WBs. CD9 is used as an exosome marker. (C) Western blot analysis of exosomes isolated from plasma of 4 AML patients (Pt1 – Pt4) and a normal donor (NC). Each lane was loaded with 10μg exosome protein (D) Proliferation of CFSE+ CD4+ T cells is inhibited by exosomes isolated from plasma of normal donors or HNSCC patients. (E) Apoptosis in CD8+ Jurkat cells is induced by exosomes of normal donors and HNSCC patients. Figures 4A, B, C and D printed by permission of Springer Nature: Springer ebook Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Methods and Protocols, Methods in Molecular Biology by Paolo Fortina et al. (eds.) in the chapter “Isolation of Biologically Active Exosomes from Plasma of Patients with Cancer” by Chang-Sook Hong, Sonja Funk, and Theresa L. Whiteside, copyright 2017.

Basic Protocol 3: Separation of TEX-enriched exosomes from non-malignant exosomes

The mini-SEC method isolates total exosomes from plasma. These exosomes are a mix of vesicles derived from different cells. Although exosomes isolated from plasma of cancer patients are enriched in TEX, additional separation and further enrichment in TEX might be obtained by immune capture. T cell-derived exosomes represent a substantial proportion (up to 50%) of total exosomes isolated from cancer patients’ plasma (Theodoraki et al., 2018), and removal of CD3(+) exosomes leaves behind an exosome fraction highly enriched in TEX. The two exosome fractions: one enriched in TEX, the other containing only CD3(+) exosomes are recovered and characterized. The recovery of T cell-derived CD3(+) exosomes provides an opportunity to inquire about the functional attributes of T cells in the tumor microenvironment.

Immune capture of CD3(+) exosomes is readily accomplished by using commercially-available anti-CD3 mAbs (Theodoraki et al., 2018). The procedure involves streptavidin-labeled beads coated with biotinylated anti-CD3 mAbs for capture of CD3(+) exosomes, as illustrated in Figure 5. The optimal ratio of anti-CD3 mAbs to exosomes to beads has to be determined in preliminary experiments. CD3(+) Jurkat cell line produces masses of CD3(+) exosomes and can be utilized for preliminary titration experiments. We used exosome protein concentrations from 5–20µg, anti-CD3 mAb dilutions ranging from 1:10 to 1:50 depending on the Ab protein level in a vial and 10–100µL of MBL beads for capture of CD3(+) exosomes. The optimal combination of 10µg exosome protein, 1:50 dilution of anti-CD3 mAb and 50µL of beads worked best (Theodoraki et al., 2018).

Fig. 5:

Immune capture of CD3(+) exosomes and detection of the exosome cargo by on-bead flow cytometry. (A) After exosome isolation from plasma via mini-SEC, immune capture with anti-CD3 biotinylated antibody on beads can be used to separate CD3(+) from uncaptured CD3(–) exosomes. (B) Surface markers carried by CD3(+) exosomes can be detected by on-bead flow cytometry. Non-captured CD3(–) exosomes can be captured on beads using biotinylated ant-CD63 antibody for detection. (Figures 5A and B adapted from Theodoraki, M., Hoffmann, T. K. and Whiteside, T. L. (2018), Separation of plasma-derived exosomes into CD3(+) and CD3(-) fractions allows for association of immune cell and tumor cell markers with disease activity in HNSCC patients. Clin Exp Immunol, 192: 271–283.).

Materials List

ExoCap™ Streptavidin Kit (MBL International,Woburn, MA, USA, cat. # MEX-SA)

Biotin anti-human CD3 antibody (clone: Hit3a; Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA, cat. # 300303

MagRack 6 (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Marlborough, MA, USA, cat. # 28948964)

1.5 mL Fisherbrand™ Premium Microcentrifuge Tubes (Fisher Scientific, cat. # 05-408-129)

Protocol steps

Exosome capture on magnetic beads

Isolate exosomes from human plasma as described in Basic Protocol 2 (Steps 1–5)

Determine exosome protein concentration in fraction #4 by BCA as described below

Place fraction #4 exosomes in a 1.5mL microfuge tube adjusting the concentration to 10µg exosome protein in 100µL PBS

Co-incubate with biotin-labeled anti-CD3 mAb (1:50) for 2h at RT

Add a 50µL aliquot of beads and incubate for 2h at RT

Remove the uncaptured fraction using a magnet and transfer exosomes to a new microfuge tube

Wash the captured exosome fraction 3x with dilution buffer provided by the ExoCap™ kit

Using this capture method results in CD3(+) exosomes bound to the MBL beads and CD3(−) exosomes suspended in PBS (Fig. 5A). Both exosome fractions can be used for marker detection by on-bead flow cytometry. However, CD3(−) exosomes are first captured on magnetic beads coated with anti-CD63 mAbs and are recovered on a magnet. Exosomes in both fractions can then be stained with fluorescence-conjugated detection mAbs of choice and analyzed by flow cytometry as previously reported (Theodoraki et al., 2018). Additionally, both exosome fractions can be analyzed by immunoblotting or studied for functions. Removal of beads might be necessary depending on the downstream application.

Support protocols

Support protocol 1: Characterization of exosomes

Isolated exosomes or immunocaptured exosome subsets should be characterized to confirm that they fit the exosome definition as specified by the current ISEV guidelines (Théry et al., 2019). The following assays are recommended: protein levels, TEM images, size distribution and particle concentration, and cargo analysis by immunoblots and/or flow cytometry.

Materials list

Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, cat. # 23225)

TEM Copper Grids (200 Mesh, Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA, cat# G200TT-CU)

Uranyl acetate (Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA, cat# 22400)

0.5mL 100KDa Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter Units (EMD Millipore, cat. # UFC510096)

Centrifuge 5415 D (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany)

Transmission electron microscope JEOL JEM1011 (JEOL, Inc., Peabody, MA)

qNano (Izon, Cambridge, MA)

Lane Marker Reducing Sample Buffer (5X, Thermo Scientific, cat. # 39000)

Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ Gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., cat. # 456-1084)

Immobilon®-P Transfer Membranes (EMD Millipore, cat. # IPVH00010)

Anti-TSG101 (1:500, abcam, cat. # ab30871)

Anti-PD-L1 (1:500, Santa Cruz, cat. # sc-19090)

Anti-PD-1(1:500, R&D Systems, cat. # MAB1086)

Anti-TGF-β1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling, cat. # 3711)

Anti-CD9 (1:500, Abcam, cat. # ab65230)

Human Angiogenesis Array Kit (R&D Systems Inc., cat. # ARY007)

Exosome protein levels

Isolate TEX from cell culture supernatants or plasma following Basic Protocol 1 or Basic Protocol 2, respectively.

Determine protein concentrations by using a BCA protein assay following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Isolate TEX from cell culture supernatants or plasma following Basic Protocol 1 or Basic Protocol 2, respectively.

Use freshly isolated exosomes and keep them on ice until TEM imaging

Pipet TEX on a copper grid coated with 0.125% Formvar in chloroform

Stain with 1% (v/v) uranyl acetate in ddH2O.

Visualize TEX and their morphology and diameters are noted as is TEX aggregation or clumping.

Tunable resistive pulse sensing (TRPS)

Use freshly isolated TEX from cell culture supernatants or plasma following Basic Protocol 1 or Basic Protocol 2, respectively, and keep them on ice until qNano measurements

The size distribution and concentrations of the particles in isolated exosome fractions can be analyzed using TRPS by qNano (Izon, Cambridge, MA) according to the manufacturers’ recommendation.

Representative results are shown in Figure 3C. Samples were measured using following conditions: NP#49607, stretch 45.64mm, voltage 0.7V and two pressure steps 3–7mbar. The particle calibration (Part#: CRC100b, mean diameter: 114nm, dilution: 1:1000) was measured directly after the experimental sample under identical conditions. Data recording and analysis were performed using the Izon software (version 3.2).

Western blot analysis

Use freshly isolated TEX from cell culture supernatants or plasma following Basic Protocol 1 or Basic Protocol 2, respectively.

Concentrate TEX to 5μg in 20μL using 0.5mL 100K Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters at 2000xg.

Add Lane Marker Reducing Sample Buffer to your sample

Heat denature sample at 90°C for 5–10min

Let samples cool and load the gel sample wells

Transfer into an Immobilon membrane

Analyze with antibodies of exosomal markers, such as CD9 or TSG101, and other cancer-related markers following common Western Blot protocols. A list of antibodies which we used in this study can be found in the materials list.

Angiogenesis antibody arrays

Isolate TEX from cell culture supernatants or plasma following Basic Protocol 1 or Basic Protocol 2, respectively.

Measure protein concentration of your sample as described above in Supporting Protocol 1.

The concentration of the sample might be required depending on the amount of protein. Use 0.5 mL 100K Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters at 2,000xg for concentration.

The relative levels of human angiogenesis–related proteins in TEX or their parent cell lines can then be measured using a Human Angiogenesis Array Kit (R&D Systems Inc.) according to the manufacturers’ protocols.

Analyze data with the ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

Support protocol 2: Examples of functional assays

After collection of fraction #4 by mini-SEC (Basic Protocol 1 or Basic Protocol 2), TEX can be characterized for functions by co-incubation with immune or other target cells. Here we provide information for different methodologies and downstream applications, which can be utilized to study the recovered TEX.

Materials List

Whole blood of normal donors

Falcon™ 50 mL Conical Centrifuge Tubes (Fisher Scientific, cat. # 14-432-22)

Ficoll® Paque Plus (Millipore Sigma, cat. # 17-1440-03)

Lonza™ BioWhittaker™ Phosphate Buffered Solution (PBS) (Lonza Inc., cat. # BW17-516F)

RPMI-1640 Medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, cat. # R0883)

Corning™ Regular Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, cat. # MT35011CV)

Penicillin Streptomycin Solution (Corning, Corning, NY, USA, cat. # 30-002-CI)

L-Glutamine (Fisher Scientific, cat. # 25030081)

150 cm2 BD Falcon™ Tissue Culture Treated Flasks (Fisher Scientific, cat. # 08-772-48)

CD4+ T Cell Isolation Kit, human (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA, cat. # 130-096-533)

CD8+ T Cell Isolation Kit, human (Miltenyi Biotec, cat. # 130-096-495)

AutoMACS cell separator (Miltenyi Biotec)

CellTrace™ Blue Cell Proliferation Kit (Thermo Scientific, cat. # C34568)

Accuri flow cytometer (BD Bioscience)

FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences, cat. # 556547)

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell (PBMC) Isolation and Culture

-

1

Collect human venous blood sample in heparinized vials and mix with sterile PBS (pH 7.4) by gently inverting the tube several times (1:1 v/v)

-

2

Fill 15 mL of Ficoll Paque in a 50mL centrifuge tube

-

3

Gently layer 35mL of the diluted blood on the top of Ficoll Histopaque using a pipette

NOTE: The layering should be done very slowly avoiding a mixture of blood and Ficoll Paque

-

4

Centrifuge tubes for 20 min at 1200xg at 4 °C with the break function turned off

-

5

Immediately aspirate the buffy coat (~10 ml) (PBMCs) which is formed in the interphase between Histopaque and plasma

-

6

Transfer to a new tube and wash three times (100xg for 10 min) with 50mL of sterile PBS

-

7

Resuspend PBMCs in RPMI supplemented with 10% (v/v) exosome-depleted FBS, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM/L l-glutamine and plate for 2–3 h to remove plastic-adherent monocytes

-

8

Determine cell number

NOTE: Isolation from 10mL of blood leads to an approximate yield of 107 to 108 PBMCs.

Primary CD4(+) and CD8(+) T Cell Isolation

Isolate PBMCs as described above in Support Protocol 2

Perform cell separation by using negative isolation kits for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells on an autoMACS cell separator following the manufacturer’s instructions

NOTE: Approximate yield of cells from 5×107 of PBMCs ranges from 1×107 to 2×107 CD4(+) or CD8(+) cells.

CFSE-Based Proliferation Assay with CD4(+) T Cells

Isolate primary CD4(+) T cells as described above in Support Protocol 2

Label cells with 1.5µM of CSFE with 0.1% BSA in PBS for 10 min at 37°C

Quench staining with an equal volume of exosome-depleted FBS followed by two washed with RPMI

Activate CFSE-labeled CD4(+) T cells at a ratio of 105 cells/100μL in a 96-well plate with CD3/28 (i.e., plate-bound CD3 and CD28 in solution, 2 μg/mL) and IL-2 (i.e., 150 IU/mL, PeproTech) for 24 h. Also, resting CFSE+ T cells were plated at the same concentration as controls

Incubate 105 CFSE-labeled CD4(+) T cells with 2–3μg of TEX in 50μL PBS (See Basic Protocol 1 or Basic Protocol 2) or no exosomes (50μL PBS)

Determine proliferation using flow cytometry after 4 or 5 days of incubation

Annexin V-based apoptosis assays with CD8(+) Jurkat cells

Seed 105 CD8(+) Jurkat cells per well of a 48-well plate in exosome-depleted RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/L) for 24 h at 37°C

Freshly isolate TEX from cell culture supernatants or plasma following Basic Protocol 1 or Basic Protocol 2, respectively

Add a curve with different concentrations of TEX from a stock solution with 1 µg/µL and create the appropriated controls (RPMI 10%, PBS control, positive control and non-activated cells) (Author suggestion: concentrations between 1 – 50 µg of total exosomal protein)

Incubate 37 °C for 6–24 hours

Measure apoptosis after 24 h of co-culture at 37°C using Annexin V assays and an Accuri flow cytometer

REAGENTS AND SOLUTIONS:

Culture medium: Sterile filtered base medium supplemented with 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin and 10% (v/v) exosome-depleted and heat-inactivated FBS

Exosome-depleted fetal bovine serum (FBS): Ultracentrifuge FBS for 3h at 100,000xg or purchase exosome-depleted medium

Sepharose: Wash Sepharose x 3 with 500mL PBS before column preparation. Sepharose has to settle down for at least 4h between washing steps

Sepharose™ CL-2B (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden, cat. # 17-0140-01)

COMMENTARY

BACKGROUND INFORMATION:

Early studies of TEX recovered from supernatants of tumor cell lines indicated that such TEX carried various immuno-suppressive proteins and inhibited functions of immune cells in vitro and in vivo in murine tumor models (Wieckowski et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2012). TEX were shown to directly deliver suppressive signals to immune cells or indirectly mediate immune suppression by promoting expansion and functions of regulatory T cells (Treg) or myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) (Webber et al., 2010; Mrizak et al., 2015; Szajnik et al., 2010). These observations provided a strong rationale for considering TEX as contributors to tumor-induced immune suppression, which is held responsible, at least in part, for tumor escape from the host immune system (Whiteside, 2013). More recent studies indicate that TEX are also engaged in re-programming of non-malignant cells in the TME, converting them into cells promoting tumor growth (Ludwig et al., 2018).

The rapidly emerging role of TEX as potential cancer biomarkers and as carriers of tumor-derived suppressive signals modulating functions of immune cells has led to a rapid development of methods for their isolation and characterization. Ultracentrifugation at 100,000×g for 2–3h followed by sucrose density gradient centrifugation to recover purified exosomes floating at the density of 1.13–1.19 g/mL has been widely used for exosome isolation (Théry et al., 2006). Today, high-speed ultracentrifugation remains widely used as the “classical” method for obtaining exosomes. However, ultracentrifugation pellets not only exosomes but other EVs as well. It is a time-consuming, laborious, analytical method that even with more recently implemented modifications (Boriachek et al., 2018) is not applicable to high-throughput processing of specimens that are to be used for biomarker studies or immune monitoring. Aside from a risk for protein complex formation and a vesicle loss due to aggregation, methods relying on ultracentrifugation and density gradient exosome separation may lead to a loss of biological functions, as commented by us and others (Boriachek et al., 2018; Muller et al., 2014; Gardiner et al., 2016). Various other methods are available for TEX isolation, including polyethylene glycol-mediated precipitation, microfluidics, immunoaffinity capture-based technologies, size exclusion chromatography (Tauro et al., 2012; Taylor et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2010) and many proprietary commercially available procedures. Most of these methods were developed by utilizing EVs in supernatants of cultured cell lines. This is because in a cell culture, the origin of EVs can be determined and because relatively simple chemical composition of most culture media facilitates isolation of vesicles devoid of ‘contaminating’ proteins, lipids and sugars. Consequently, much of what we currently know about TEX comes from studies of tumor cell line supernatants. Studies of TEX in patients’ plasma represent a major challenge, because body fluids contain a mix of EVs produced by many different tissue and hematopoietic cells and because of the presence of a broad variety of “contaminating” plasma proteins, which interfere with isolation and characterization of exosomes.

TEX are produced in excess by tumor cells, and they represent a prominent component of total exosomes in cancer patients’ plasma (Sharma et al., 2018). Levels of exosomes are elevated in cancer patients’ plasma relative to those in healthy donors’ plasma (Ludwig et al., 2018). These exosomes are enriched in immunosuppressive ligands, such as PD-L1, TGF-β1, FasL or TRAIL known to be carried by TEX, and to suppress functions of immune cells (Hong et al., 2017). Further, levels of exosomes in cancer patients’ plasma appear to correlate with disease activity, cancer progression and with patients’ responses to therapy (Ludwig et al., 2017; Hong et al., 2014). Thus, levels of TEX-enriched exosomes in cancer patients’ plasma emerge as a potentially clinically-relevant biomarker for cancer and impose the need for establishing criteria for their reliable recovery and for consistency in testing their biological activity upon isolation.

Among various technologies for exosome isolation, size exclusion chromatography (SEC) has been introduced some years ago as a favorable method for recovery of “clean” exosomes from cell supernatants or plasma (Chen et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2011; Tauro et al., 2012). We and others have reported on the use of SEC to isolate vesicles from human plasma or platelet concentrates and commented on advantages of SEC over other isolation methods (Welton et al., 2015; Böing et al., 2014; de Menezes-Neto et al., 2015). The underlying principle of the SEC-based methodology is described in Fig. 1. It allows for consistent recovery of vesicles that are in large part, although not completely, depleted of plasma components such as albumin, immunoglobulins and other proteins, are structurally intact and functionally competent (Hong et al., 2016). In cancer patients, these vesicles are highly enriched in TEX (Sharma et al., 2018). The recovery of vesicles that are structurally intact and functionally active is an important advantage of SEC-based isolation. It has been suggested that TEX interacting with immune cells deliver reprogramming signals upon a direct contact with the cell surface rather than via internalization (Hwang and Ki, 2011). The integrity of isolated exosomes and their purity may be of key importance for such surface receptor-mediated information transfer. The formation of exosomal aggregates or an excess of non-exosomal “contaminants” on the TEX membrane could interfere with their signaling functions. Therefore, testing of the ability of SEC-purified exosomes to alter functions of primary human T cells or NK cells in co-cultures is an important advantage of this isolation method.

Fig. 1:

Illustration of the SEC principle. (A) The column bed consists of Sepharose beads. Very small molecules (blue) enter pores in the gel, equilibrating between the gel and the moving buffer, and so travel slowly and are eluted later. Medium sized molecules (green) enter some pores in the gel, equilibrating between the gel and the moving buffer. Large molecules (red) enter few pores in the gel, and so travel rapidly and are eluted sooner. (B) Schematic illustration of the mini-SEC column showing larger molecules being eluted faster followed by medium sized and smaller molecules which enter the pores of the Sepharose beads. (C) Graph describing the time-dependent elution of small, medium sized and large molecules.

CRITICAL PARAMETERS AND TROUBLESHOOTING:

Mini-SEC can be adapted to operate as a rapid method for isolation of exosomes from larger volumes of human plasma. The small-scale columns can be set up side-by-side allowing for processing of multiple 1mL aliquots of plasma in parallel (Hong et al., 2016). Alternatively, larger columns can be used for higher plasma volumes, but only after the columns are properly calibrated for exosome recovery. Optimization of the isolation procedure relative to the column size is a critical step for SEC. The Coomassie blue staining which is presented in Fig. 4B illustrates the optimization process for mini-SEC. The exosome marker CD9 is mostly present in fraction #4, indicating the enrichment in exosomes. As described above for exosomes derived from cell line supernatants, plasma-derived exosomes isolated by mini-SEC show typical vesicular morphology. Cancer patient derived exosomes (Pt1 – Pt4) are enriched in immunosuppressive proteins compared to exosomes from normal donors (NC) (Fig. 4C) and suppress proliferation of CD4+ T cells in vitro (Fig. 4D) and induce apoptosis of activated CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4E). Functional studies which are presented in Fig. 4 are described in detail in Support Protocol 2. The vesicles recovered in fractions #3 may be larger than 150nm and those in fraction 5 tend to aggregate, as shown in Fig. 4A. Exosomes in fraction #4 are non-aggregated and contain relatively few “contaminating” plasma proteins.

The most likely difficulties are to be expected with: (a) the selection of the different conditions, specifically the column size for SEC of exosomes, if different from those described and (b) selection and titration of mAbs for flow cytometry or separation of CD3(+) and CD3(−) exosomes. The recommendations for handling these steps and potential solutions were discussed in the above text (Basic Protocol 1 and Basic Protocol 3). The importance of consistent cell culture conditions for Basic Protocol 1 has been discussed by us before (Ludwig et al., 2019).

UNDERSTANDING RESULTS:

This protocol provides specific examples to illustrate how different specimens were processed and to indicate what results should be expected. The examples are informative and applicable to real-life situations. The Commentary summarizes criteria for result interpretation and the rationale for exosome isolation and fractionation into distinct subsets.

TIME CONSIDERATIONS:

Basic Protocol 1 and 2

Preparation and running of the mini-SEC columns takes about 20–30 min depending on the number of columns. Basic Protocol 1 and 2 represent time-saving over ultracentrifugation protocols, which are commonly used. Pre-clearing of the supernatants or human plasma takes 45 min including all centrifugation steps. Please note that processing of cell culture supernatants adds 60 min for concentration of the samples and a 72h incubation time which is necessary for exosome generation by the cell line.

Basic Protocol 3

The separation into CD3(+) and CD3(−) requires 5 hours in total, which includes 4.5 hours of incubation time.

Support Protocol 1

The time consideration for the characterization of TEX differs depending on the performed assays. The BCA requires 40 min, TEM requires 30–40 min per sample and TRPS requires 1–2 hours per sample. Western blots/arrays are generally 2 day protocols, the time consideration highly depends on the laboratory’s individual protocols.

Support Protocol 2

Isolation of PBMCs requires 3.5 hours including incubation times. The magnetic cell separation and seeding add about 1.5 additional hours. The time considerations for the CFSE assay depends on the incubation time. CFSE-labeling only requires 30 min, followed by a 4–5 day incubation time. Flow cytometric and data analysis requires 1.5 hours. Apoptosis assays require 30 min for cell seeding and treatment, followed by 6–24 hours of incubation and 2 hours for performing the assay, analyze apoptosis by flow cytometry and analyze the data.

Acknowledgements

The reported studies were supported in part by NIH grants R01-CA168624 and R21-CA204644 to TLW. N. Ludwig was supported by the Leopoldina Fellowship LPDS 2017-12 from German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. J.H. Azambuja was supported by the Programa de Doutorado Sanduíche no Exterior (PDSE) 88881.188926/2018-01 from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES). M-N Theodoraki was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (research fellowship no. TH2172/1-1).

References

- Böing AN, van der Pol E, Grootemaat AE, Coumans FAW, Sturk A, and Nieuwland R 2014. Single-step isolation of extracellular vesicles by size-exclusion chromatography. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles 1:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boriachek K, Islam MN, Möller A, Salomon C, Nguyen NT, Hossain MSA, Yamauchi Y, and Shiddiky MJA 2018. Biological Functions and Current Advances in Isolation and Detection Strategies for Exosome Nanovesicles. Small 14:1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Skog J, Hsu C, Lessard R, Balaj L, Wurdinger T, Carter B, Breakefield X, Toner M, and Irimia D 2010. Microfluidic isolation and transcriptome analysis of serum microvesicles. Lab Chip 10:505–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Guo J, Yang M, Zhu X, and Cao X 2011. Chemokine-Containing Exosomes Are Released from Heat-Stressed Tumor Cells via Lipid Raft-Dependent Pathway and Act as Efficient Tumor Vaccine. The Journal of Immunology 186:2219–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner C, Vizio D. Di, Sahoo S, Théry C, Witwer KW, Wauben M, and Hill AF 2016. Techniques used for the isolation and characterization of extracellular vesicles: Results of a worldwide survey. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles 5:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessvik NP, and Llorente A 2018. Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 75:193–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong C-S, Funk S, Muller L, Boyiadzis M, and Whiteside TL 2016. Isolation of biologically active and morphologically intact exosomes from plasma of patients with cancer. Journal of extracellular vesicles 5:29289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong C-S, Muller L, Whiteside TL, and Boyiadzis M 2014. Plasma exosomes as markers of therapeutic response in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Frontiers in immunology 5:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong CS, Sharma P, Yerneni SS, Simms P, Jackson EK, Whiteside TL, and Boyiadzis M 2017. Circulating exosomes carrying an immunosuppressive cargo interfere with cellular immunotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Scientific Reports 7:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I, and Ki D 2011. Receptor-mediated T cell absorption of antigen presenting cell- derived molecules. Front Biosci 16:411–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharzewska P, Christianson HC, Welch JE, Svensson KJ, Fredlund E, Ringnér M, Mörgelin M, Bourseau-Guilmain E, Bengzon J, and Belting M 2013. Exosomes reflect the hypoxic status of glioma cells and mediate hypoxia-dependent activation of vascular cells during tumor development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110:7312–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig N, Razzo BM, Yerneni SS, and Whiteside TL 2019. Optimization of cell culture conditions for exosome isolation using mini-size exclusion chromatography (mini-SEC). Experimental Cell Research 378:149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig N, Yerneni SS, Razzo BM, and Whiteside TL 2018. Exosomes from HNSCC Promote Angiogenesis through Reprogramming of Endothelial Cells. Molecular Cancer Research 16:1798–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig S, Floros T, Theodoraki M-N, Hong C-S, Jackson EK, Lang S, and Whiteside TL 2017. Suppression of Lymphocyte Functions by Plasma Exosomes Correlates with Disease Activity in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 23:4843–4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Menezes-Neto A, Sáez MJ, Lozano-Ramos I, Segui-Barber J, Martin-Jaular L, Ullate JME, Fernandez-Becerra C, Borrás FE, and del Portillo HA 2015. Size-exclusion chromatography as a stand-alone methodology identifies novel markers in mass spectrometry analyses of plasma-derived vesicles from healthy individuals. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles 4:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milane L, Singh A, Mattheolabakis G, Suresh M, and Amiji MM 2015. Exosome mediated communication within the tumor microenvironment. Journal of Controlled Release 219:278–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrizak D, Martin N, Barjon C, Jimenez-Pailhes AS, Mustapha R, Niki T, Guigay J, Pancré V, De Launoit Y, Busson P, et al. 2015. Effect of nasopharyngeal carcinoma-derived exosomes on human regulatory T cells. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 107:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller L, Hong CS, Stolz DB, Watkins SC, and Whiteside TL 2014. Isolation of biologically-active exosomes from human plasma. Journal of Immunological Methods 411:55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P, Ludwig S, Muller L, Hong CS, Kirkwood JM, Ferrone S, and Whiteside TL 2018. Immunoaffinity-based isolation of melanoma cell-derived exosomes from plasma of patients with melanoma. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles 7:1435138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szajnik M, Czystowska M, Szczepanski MJ, Mandapathil M, and Theresa L 2010. Tumor-Derived Microvesicles Induce, Expand and Up-Regulate Biological Activities of Human Regulatory T Cells (Treg). PLoS ONE 5:e11469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauro BJ, Greening DW, Mathias RA, Ji H, Mathivanan S, Scott AM, and Simpson RJ 2012. Comparison of ultracentrifugation, density gradient separation, and immunoaffinity capture methods for isolating human colon cancer cell line LIM1863-derived exosomes. Methods 56:293–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D, Zacharias W, and Gercel-Taylor C 2011. Exosome Isolation for Proteomic Analyses and RNA Profiling. Methods in Molecular Biology 728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodoraki M-N, Hoffmann TK, and Whiteside TL 2018. Separation of plasma-derived exosomes into CD3(+) and CD3(−) fractions allows for association of immune cell and tumour cell markers with disease activity in HNSCC patients. Clinical and experimental immunology 192:271–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théry C, Amigorena S, Raposo G, and Clayton A 2006. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Current protocols in cell biology Chapter 3: Unit 3.22. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18228490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, Antoniou A, Arab T, Archer F, Atkin-Smith GK, et al. 2019. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles 8:1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber J, Steadman R, Mason MD, Tabi Z, and Clayton A 2010. Cancer Exosomes Trigger Fibroblast to Myofibroblast Differentiation. Cancer Research 70:9621–9631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welton JL, Webber JP, Botos LA, Jones M, and Clayton A 2015. Ready-made chromatography columns for extracellular vesicle isolation from plasma. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles 4:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside TL 2013. Immune Responses to Cancer: Are They Potential Biomarkers of Prognosis? Frontiers in Oncology 3:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieckowski E, Visus C, Szajnik M, Szczepanski M, Storkus W, and Whiteside T 2009. Tumor-Derived Microvesicles Promote Regulatory T Cell Expansion and Induce Apoptosis in Tumor-Reactive Activated CD8+ T Lymphocytes. J Immunol 183:3720–3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Ruffner M, Kim S-H, and Robbins P 2012. Plasma-derived MHCII+ exosomes from tumor-bearing mice suppress tumor antigen-specific immune responses. Eur J Immunol 42:1778–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]