Abstract

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is characterized by apoptotic cell loss in the retinal vasculature. Lysyl oxidase propeptide (LOX-PP), released during LOX processing, has been implicated in promoting apoptosis in various diseased tissues. However, its role in the development and progression of DR is unknown. We investigated whether high glucose (HG) or diabetes alters LOX-PP expression and thereby influences AKT pathway and affects retinal endothelial cell survival. Rat retinal endothelial cells were grown in normal medium, normal medium and exposed to recombinant LOX-PP (rLOX-PP) or HG medium and examined for LOX-PP expression, AKT and caspase-3 activation. Similarly, rats intravitreally injected with rLOX-PP were examined for changes in retinal LOX-PP levels, AKT phosphorylation, and the number of acellular capillaries and pericyte loss compared with those of control diabetic and nondiabetic rats. Results indicate that HG up-regulates LOX-PP expression and reduces AKT activation. In addition, cells exposed to rLOX-PP alone exhibited increased apoptosis concomitant with decreased AKT phosphorylation. In retinas of diabetic rats, increased LOX-PP level, decreased AKT phosphorylation, and increased number of acellular capillaries and pericyte loss compared with those of nondiabetic rats were observed. Of interest, similar changes were noted in the retinas of rats injected with rLOX-PP. Findings from this study suggest that hyperglycemia-induced LOX-PP overexpression may contribute to retinal vascular cell loss associated with DR.

Diabetic retinopathy, the leading cause of blindness in the working age population,1, 2 is characterized by early vascular lesions such as the development of acellular capillaries (ACs) and pericyte loss (PL).3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Retinal vascular basement membrane thickening, a histologic hallmark of diabetic retinopathy,9, 10, 11, 12 has been shown to promote apoptosis and to contribute to retinal vascular cell loss.13, 14, 15 Lysyl oxidase (LOX), an extracellular enzyme responsible for cross-linking collagen and elastin molecules to form a stable extracellular matrix, has been implicated in promoting high glucose (HG)-induced apoptosis.16 Of interest, studies suggest that LOX-propeptide (PP), which results from the extracellular proteolytic biosynthetic processing of proenzyme (pro)-LOX, also plays a role in triggering apoptosis in various diseased tissues.17, 18, 19, 20 However, it is currently unknown whether LOX-PP is involved in HG-induced apoptosis and subsequently contributes to retinal vascular cell loss.

LOX-PP is derived from a 50-kDa proenzyme (pro-OX), which undergoes proteolytic cleavage, resulting in a 32-kDa active enzyme (LOX)21, 22 and a 18-kDa LOX-PP.23 Although the role of the mature LOX enzyme in extracellular matrix maturation is well established, the role of LOX-PP is less well understood. A key function of LOX-PP is suggested to be the maintenance of LOX in an inactive state.24 In addition, it has been postulated that glycosylation of the LOX-PP is required for ultimate optimal LOX enzyme activity.25 In addition, LOX-PP has also been shown to inhibit ras signaling through its ras recision function.26, 27, 28 Furthermore, LOX-PP has been shown to re-enter cells by micropinocytosis23 after which it binds to and inhibits several important signaling molecules.18, 29, 30

Studies indicate that LOX-PP can act as a pro-apoptotic factor. In pancreatic cells, LOX-PP was shown to compromise AKT activity,19, 31 and administration of LOX-PP reduced growth of tumors in a mouse xenograft model.19 In addition, ectopic overexpression of recombinant (r)LOX-PP suppressed the growth of breast cancer xenografts,17 and rLOX-PP administration led to prominent increases in apoptosis markers and reduced tumor volumes.17 In an in vitro study, LOX-PP was found to promote apoptosis and inhibit cell proliferation.20 In addition, exposure to rLOX-PP suppressed tumor growth by interfering with DNA repair pathways.18 These findings provide evidence that LOX-PP overexpression may trigger apoptosis. However, it is unknown whether LOX-PP promotes retinal vascular cell loss associated with diabetic retinopathy.

In the present study, we investigated whether HG alters LOX-PP expression, disrupts AKT activation, and promotes apoptosis in retinal endothelial cells. In addition, studies were conducted in vivo to determine whether LOX-PP levels were altered in the retinas of diabetic rats and whether intravitreal injections of rLOX-PP promoted retinal vascular lesions.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

In this study, endothelial cells from rat retinas (RRECs) were isolated as described32 and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), antimycotics, and antibiotics. RRECs were grown on coverslips and 35-mm dishes in normal (N; 5 mmol/L glucose) medium, or N medium + 30 mmol/L mannitol (N+Man) as osmotic control, or HG (30 mmol/L glucose) medium for 7 days until confluence. After cells became approximately 75% confluent, they were maintained in low-serum medium that contained 2% fetal bovine serum for 24 hours, then treated as described in each experiment to preclude serum-stimulated effects on AKT activation. To assess the effect of LOX-PP overexpression on cell viability, RRECs grown in serum-starved, N medium were exposed to 8 μg/mL purified rLOX-PP 24 hours before harvest. Of the four rLOX-PP doses tested (2, 4, 8, or 16 μg/mL), the dose of 8 μg/mL rLOX-PP was selected on the basis of promoting a similar increase in the number of apoptotic cells as that of cells grown in HG medium. Total protein from RRECs was isolated and subjected to Western blot (WB) analysis. Cells from the experimental groups were assayed for LOX-PP expression and AKT activation. In vitro experiments were performed independently four times.

Animals

All animal studies were performed according to the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Twenty-four male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were randomly assigned into four groups: non-diabetic wild-type (WT), diabetic, WT with intravitreal injections of rLOX-PP (WT+rLOX-PP IV), and WT with intravitreal injections of phosphate-buffered saline (WT+PBS IV). Intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin (55 mg/kg body weight) was performed to induce diabetes. Blood glucose levels were monitored 3 days after streptozotocin injection to confirm diabetes status in the animals. The diabetic animals were maintained for 16 weeks along with their controls. For each animal, blood glucose levels were monitored routinely (twice weekly) until the end of the study. Rats with blood glucose levels of 300 to 400 mg/dL were considered diabetic. To maintain hyperglycemia without ketoacidosis and severe loss of body weight in diabetic rats, neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin injections were administered as needed. All animals were sacrificed at the end of study, and retinal protein was isolated and examined for LOX-PP, AKT, and phospho- (p-)AKT protein expression by WB analysis.

rLOX-PP and PBS Intravitreal Injection

rLOX-PP, or PBS used as control, was administered every 3 days, for a total of three intravitreal injections. Animals were sacrificed 6 weeks after the last intravitreal injection. Intravitreal injections were performed as described previously.33 To determine the optimal dose of rLOX-PP in promoting retinal vascular cell loss, intravitreal injections of 1.25, 2.5, 5.0, or 10 μg/10 μL of rLOX-PP were performed in rat eyes. The dose of 5 μg/10 μL rLOX-PP was determined to be most optimal in exhibiting a similar increase in the number of ACs and PL as seen in the diabetic retinas. As such, 10 μL of freshly prepared 5.0 μg rLOX-PP or 1X PBS was administered per injection for in vivo experiments. Routine examinations performed during the course of the study showed no untoward effects from the intravitreal injections. From each animal, one eye was used for WB analysis, and retinal trypsin digestion was performed on the contralateral eye.

WB Analysis

In RRECs grown in N, N+Man, HG medium, or N+rLOX-PP, total protein was isolated. In parallel, retinas of WT, diabetic, WT+rLOX-PP IV, and WT+PBS IV rats were subjected to total protein isolation. Briefly, cells were subjected to PBS washes and lyzed in buffer that contained 10 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.5 (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mmol/L EDTA, and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich). Similarly, rat retinal protein was isolated by homogenizing the retina in the aforementioned lysis buffer. Lysates were then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C. Protein content in cell lysates and the retinal tissues was determined by the bicinchoninic acid protein assay method (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL). An equal amount of protein was loaded per lane and ran through electrophoresis together with molecular weight marker (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) in separate lanes on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. When electrophoresis was complete, the protein content was transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA) according to Towbin's procedure34 with the use of a semidry apparatus. After transfer was complete, the membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk for 2 hours in room temperature and incubated overnight at 4°C with anti–LOX-PP antibody, which also recognizes pro-LOX (dilution 1:500035; provided by P.C.T.), rabbit monoclonal p-AKT (Ser473) (dilution 1:2000; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), AKT (dilution 1:1000; Cell Signaling), or cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175) (dilution 1:250; Cell Signaling) antibodies in a solution of 5% bovine serum albumin dissolved in Tris-buffered saline that contained 0.1% Tween-20. The next day, the membrane was washed with 1X Tris-buffered saline that contained 0.1% Tween-20 and subsequently incubated with secondary antibody solution that contained anti-rabbit IgG, alkaline phosphatase-linked antibody (dilution 1:3000; Cell Signaling) for 1 hour at room temperature. The membrane was washed as described previously, subjected to chemiluminescent substrate (Immun-Star; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), and exposed to X-ray film (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).36 Equal loading of protein samples in the gel lanes was confirmed through Ponceau-S staining after transfer and by β-actin antibody (dilution 1:1000; Cell Signaling). Densitometric analysis of the chemiluminescent signal was performed at nonsaturating exposures and evaluated with ImageJ software version 1.52e (NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij).

Differential Dye Staining

Cells undergoing apoptosis were detected by the differential dye staining technique,37 which is based on the uptake of two fluorescent dyes, acridine orange and ethidium bromide.38 Cells were exposed to a solution that contained ethidium bromide and acridine orange, both at 25 μg/mL concentration, washed with PBS, fixed, mounted, visualized, and assessed under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Diaphot; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The number of apoptotic cells per field is shown as a percentage of the total number of cells in the field.38 Cells undergoing early and late stages of apoptosis manifest as bright green and orange, respectively, whereas normal cells manifest as uniformly dark green.

Retinal Trypsin Digestion

To analyze the effect of LOX-PP on retinal capillaries, retinal trypsin digestion technique was performed as described39 with minor modifications. Rat eyes were enucleated, and retinas were isolated and subsequently placed in glycine buffer overnight. The vascular network was isolated from the retina by subjecting the retina to 3% trypsin digestion. The capillary network was then mounted on a silane-coated slide and stained with periodic acid-Schiff and hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich). Periodic acid-Schiff stains the glycoprotein of the basement membrane pink, and hematoxylin stains the cellular nuclei dark blue. Ten random areas of the retinal vasculature were digitally captured with a fluorescence microscope (Nikon), and the images were analyzed for ACs and PL in each of the four groups. ACs, by definition, are capillaries that have lost both endothelial cells and pericytes, and they represent a tubular structure constituted of basement membrane. Typically, ACs become obliterated, appearing thinner with diminished capillary caliber and ultimately reaching a thread-like structure before complete obliteration. Pericytes, however, leave behind an empty shell of their nuclear body, which used to contain DNA and other nuclear material when they were live. These empty shells represent a tell-tale signature of diabetic retinopathy known as pericyte ghosts. AC and PL counts are based on these histologic criteria.

Statistical Analysis

Data are shown as means ± SD. Control group values were normalized to 100%, whereas other experimental groups were indicated as percentages of control. Normalized values were used to perform statistical analysis. One-way analysis of variance, followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test, was used to evaluate comparisons between the groups. Data showing P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

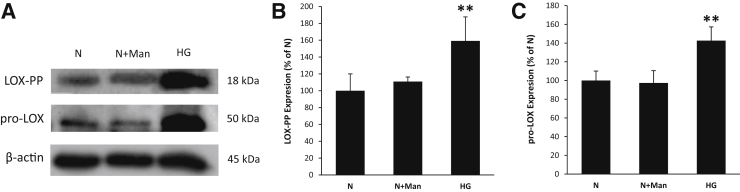

Effect of HG on LOX-PP and Pro-LOX Expression in RRECs

To determine the effects of HG on LOX-PP protein expression in RRECs, WB analyses were performed. Data indicated that LOX-PP protein levels were significantly increased in cells grown in HG medium compared with those of cells grown in N medium alone (Figure 1, A and B). To assess whether HG-induced LOX-PP up-regulation resulted from increased pro-LOX synthesis, the expression levels of pro-LOX were also measured in these cells. Similar to HG-induced LOX-PP up-regulation, pro-LOX protein levels were significantly higher in cells grown in HG medium than those of cells grown in N medium alone (Figure 1, A and C). Cells exposed to 30 mmol/L mannitol as osmotic control showed no change in LOX-PP or pro-LOX expression.

Figure 1.

High glucose (HG) up-regulated lysyl oxidase propeptide (LOX-PP) and proenzyme (pro)-LOX expression in endothelial cells from rat retinas (RRECs). A: Representative Western blot image shows that LOX-PP and pro-LOX expression was significantly increased in the HG condition. B and C: Graphical illustration of cumulative data shows HG significantly up-regulated LOX-PP (B) and pro-LOX (C) expression. Cells exposed to mannitol (Man) did not exhibit changes in LOX-PP or pro-LOX expression. Data are expressed as means ± SD. **P < 0.01 versus normal (N).

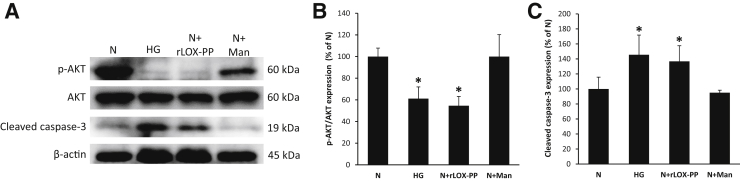

Effects of HG and rLOX-PP on AKT Activity in RRECs

To determine the effects of HG or rLOX-PP on RRECs, WB analyses were performed. Data indicated that the ratio of p-AKT to AKT was significantly decreased in cells grown in HG medium compared with that of cells grown in N medium (Figure 2, A and B). Of interest, cells grown in N medium and exposed to rLOX-PP for 24 hours exhibited a significant decrease in the ratio of p-AKT to AKT compared with that of cells grown in N medium alone (Figure 2, A and B). Cells exposed to 30 mmol/L mannitol as osmotic control showed no change in AKT activity.

Figure 2.

Up-regulation of lysyl oxidase propeptide (LOX-PP) compromised AKT activity in endothelial cells from rat retinas (RRECs). A: Representative Western blot image shows protein expression of phospho- (p-)AKT, total AKT, cleaved caspase-3, and β-actin in RRECs grown in normal (N) medium, high glucose (HG) medium, N medium exposed to recombinant (r)LOX-PP (N+rLOX-PP), or N medium exposed to mannitol (N+Man). B: Graphical illustration of cumulative data shows up-regulation of LOX-PP alone compromised AKT activation in RRECs. Cells exposed to mannitol did not exhibit changes in AKT activity. C: Graphical illustration of cumulative data shows cleaved caspase-3 expression was significantly increased in cells grown in HG and in cells grown in N medium exposed to rLOX-PP. No significant change in cleaved caspase-3 activity was observed in cells exposed to mannitol. Data are expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05 versus N.

Effects of HG and rLOX-PP on Cleaved Caspase-3 Activation in RRECs

WB analyses indicated that the protein levels of cleaved caspase-3 were significantly increased in RRECs grown in HG medium and in cells grown in N medium and exposed to rLOX-PP compared with those of cells grown in N medium alone (Figure 2, A and C). Cells exposed to 30 mmol/L mannitol as osmotic control showed no change in caspase-3 activation.

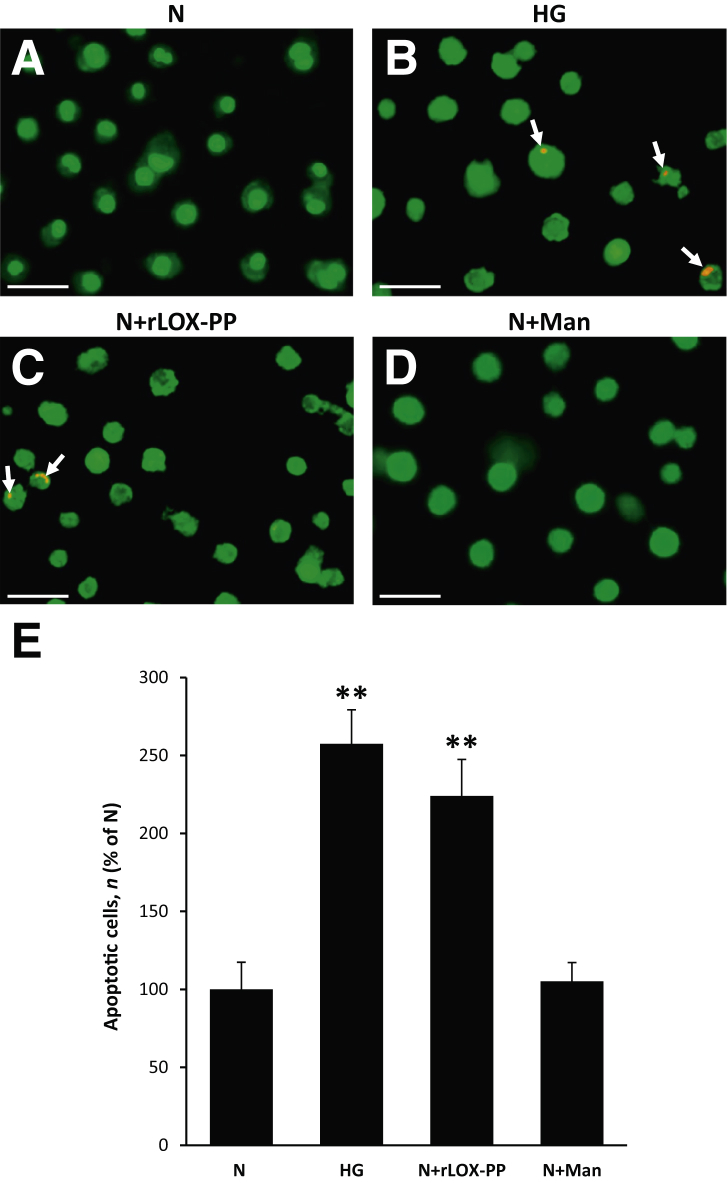

rLOX-PP Promotes HG-Induced Apoptosis in RRECs

Differential dye staining analysis indicated that cells grown in HG medium exhibited a significant increase in the number of apoptotic cells compared with that of cells grown in N medium (Figure 3). Of interest, cells grown in N medium and exposed to rLOX-PP for 24 hours resulted in a significant increase in the number of apoptotic cells compared with that of cells grown in N medium alone (Figure 3). No significant difference was found in the number of apoptotic cells in cells exposed to 30 mmol/L mannitol as osmotic control compared with that of cells grown in N medium (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Lysyl oxidase propeptide (LOX-PP) promoted apoptosis in endothelial cells from rat retinas (RRECs). A–D: Representative images of cells undergoing apoptosis (arrows): Normal (N) (A), high glucose (HG) (B), N exposed to recombinant LOX-PP (N+rLOX-PP) (C), and N exposed to mannitol (N+Man) (D). Differential staining assay showed a significant increase in the number of cells undergoing apoptosis in cells grown in HG condition and cells exposed to rLOX-PP compared with those grown in N medium. E: Graphical illustration of cumulative data shows up-regulation of LOX-PP alone promoted HG-induced apoptosis in RRECs. Cells exposed to mannitol exhibited no significant difference in the number of apoptotic cells compared with that of cells grown in N medium alone. Data are expressed as means ± SD. **P < 0.01 versus N. Scale bars = 50 μm.

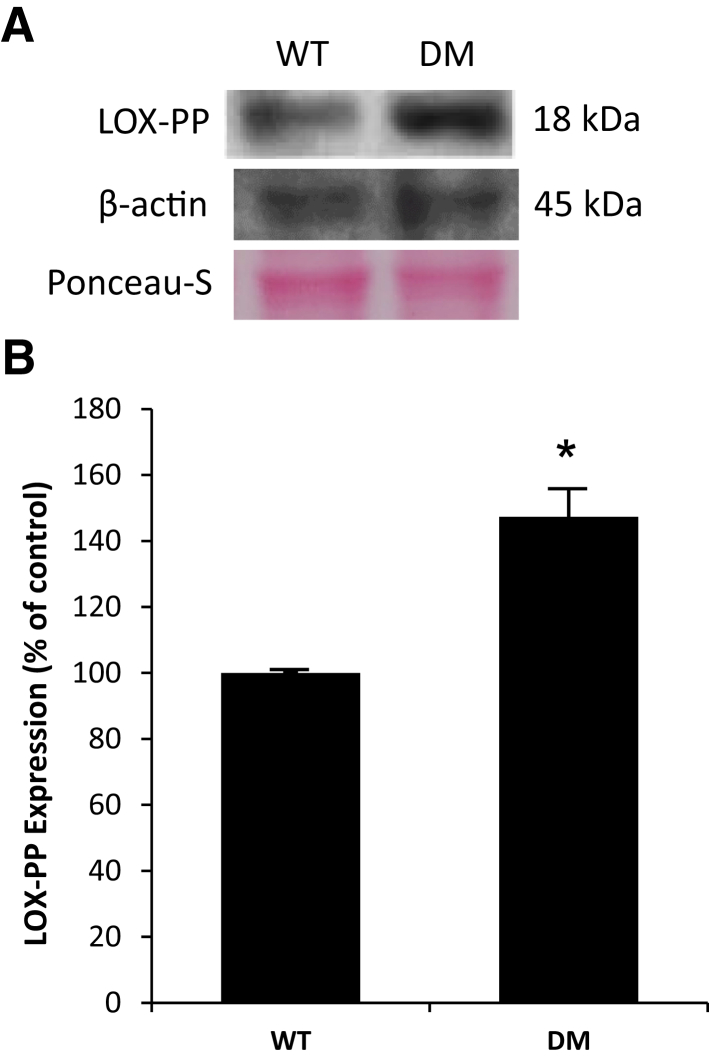

Effect of Diabetes on LOX-PP Expression in Rat Retinas

To assess LOX-PP protein level in diabetic rat retinas compared with nondiabetic rat retinas, WB analyses were performed. Data indicated that LOX-PP protein expression was significantly increased in the retinas of diabetic rats compared with that of nondiabetic rat retinas (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Lysyl oxidase propeptide (LOX-PP) expression was up-regulated in diabetic rat retinas. A: Representative Western blot image shows LOX-PP expression in the retinas of wild-type (WT) rats or diabetic (DM) rats. B: Graphical illustration of cumulative data shows LOX-PP expression was significantly increased in DM rat retinas. Data are expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05 versus WT.

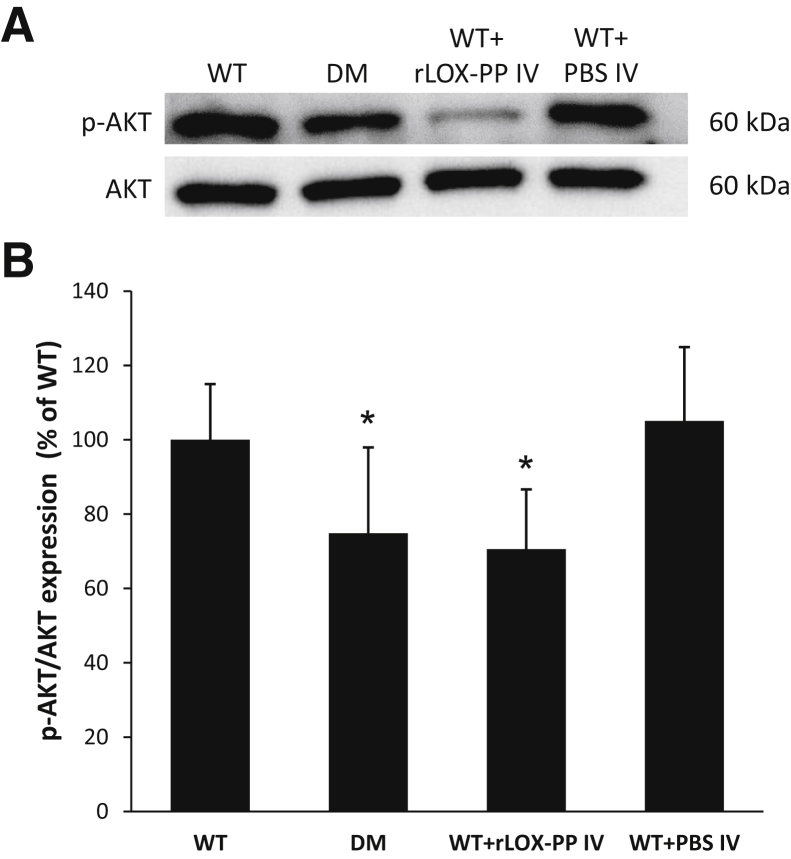

rLOX-PP Overexpression Compromises AKT Activation in Rat Retinas

To determine the effects of diabetes or rLOX-PP on AKT activation in the retinas of diabetic rats and those injected with rLOX-PP, WB analyses were performed. Data indicated that the ratio of p-AKT to AKT was significantly decreased in the retinas of diabetic rats (Figure 5). Of interest, the ratio of p-AKT to AKT was significantly decreased in retinas of nondiabetic rats intravitreally injected with rLOX-PP compared with those of nondiabetic control rats (Figure 5). Retinas of nondiabetic rats intravitreally injected with PBS showed no difference in the ratio of p-AKT to AKT compared with those of nondiabetic control rats (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Lysyl oxidase propeptide (LOX-PP) compromised AKT activation in rat retinas. A: Representative Western blot image shows protein expression of phospho- (p-)AKT, total AKT, and β-actin in retinas of wild-type (WT) rats, diabetic (DM) rats, WT rats intravitreally injected with recombinant LOX-PP (WT+rLOX-PP IV), and WT rats intravitreally injected with phosphate-buffered saline (WT+PBS IV). B: Graphical illustration of cumulative data shows LOX-PP could compromise AKT activation in rat retinas. Data are expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05 versus WT.

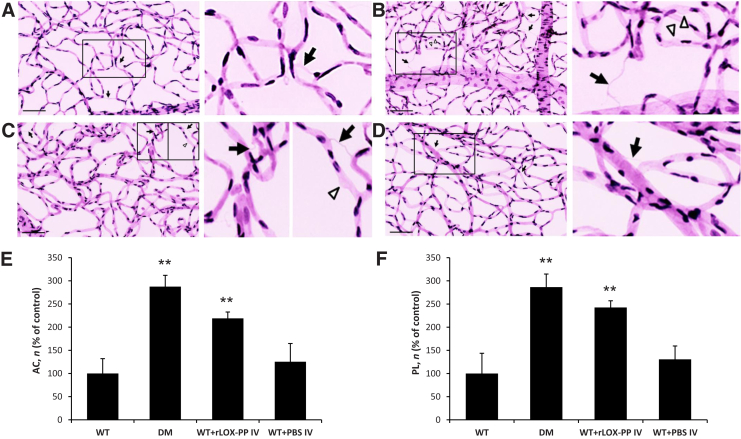

rLOX-PP Increases the Number of ACs and PL in Rat Retinas

As expected, the number of ACs and PL was increased in the retinas of diabetic rats (Figure 6). Of interest, nondiabetic rats intravitreally injected with rLOX-PP exhibited increased number of ACs and PL compared with those of nondiabetic controls (Figure 6). Retinas of nondiabetic rats intravitreally injected with PBS showed no difference in the development of ACs and PL compared with controls (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of recombinant lysyl oxidase propeptide (rLOX-PP) on the development of acellular capillaries (ACs) and pericyte loss (PL) in rat retinas. A–D: Representative retinal trypsin digest images showing retinal vascular networks of a control rat (A, left panel), diabetic (DM) rat (B, left panel), rat intravitreally injected with rLOX-PP (C, left panel), and rat intravitreally injected with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (D, left panel). LOX-PP administration promoted the development of ACs (arrows) and PL (arrowheads) associated with diabetic retinopathy. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification in the right column. E and F: Graphical illustration of cumulative data of the number of ACs (E) and PL (F) in four groups of rats: wild-type (WT), diabetic (DM), WT intravitreally injected with rLOX-PP (WT+rLOX-PP IV), and WT intravitreally injected with PBS (WT+PBS IV). Administration of rLOX-PP alone promoted the development of ACs and PL in rat retinas. **P < 0.01 versus WT. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Discussion

In this study, we show for the first time that HG-induced LOX-PP overexpression promotes apoptosis in RRECs. Because HG and diabetic conditions both increase LOX-PP levels, this finding is significant because it provides insight into a hitherto unknown mechanism for HG-induced apoptosis involving pro-LOX processing. Our findings indicate that RRECs grown in HG up-regulates LOX-PP expression and that increased LOX-PP level may compromise AKT activity in RRECs, thus contributing to apoptosis. Moreover, cells exposed directly to rLOX-PP exhibit significant increase in apoptosis as does retinas exposed to rLOX-PP by intravitreal injection. Importantly, in the retinas of diabetic rats, increased LOX-PP levels may contribute to compromised AKT activation.

In a previous study, direct application of rLOX-PP protein inhibited Ki-67 immuno-positive cells by approximately 50%, indicating the inhibitory action of rLOX-PP by decreased proliferation and possibly increased apoptosis.17 Increased apoptosis was confirmed through increased number of cells staining for active cleaved caspase-3, a marker for apoptosis, and increased number of cells positive for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling.17 In the present study, our findings in both in vitro studies that used RRECs exposed to rLOX-PP and in vivo studies that used intravitreal injections of rLOX-PP clearly indicate that LOX-PP promotes apoptosis by likely compromising AKT activity. Further studies are needed to better understand whether LOX-PP decreases Ras-mediated activation of extracellular signal regulated kinase 1 and 2 through inhibition of fibroblast growth factor-2 signaling.40

Previous studies in our laboratory and by others have shown that HG- or diabetes-induced increase in LOX contributes to retinal vascular basement membrane thickening and stiffening.36, 41 Because levels of LOX-PP are intrinsically coupled to levels of LOX from the processing of pro-LOX, it is plausible that the atrophic effects of overexpressed LOX-PP are acting simultaneously with, and possibly influenced by, the detrimental effects of changes in the retinal vascular basement membrane.

The observation that LOX-PP sensitizes pancreatic and breast cancer cells to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis is of considerable interest.19 Currently, it is unknown whether LOX-PP potentiates the effects of HG in promoting apoptosis by sensitizing retinal vascular cells to HG stress. It is unclear whether the mechanisms underlying the ability of LOX-PP to enhance the cytotoxic effects of doxorubicin in mediating apoptosis are operative for pro-apoptotic effects of glucose. One of the mechanisms by which LOX-PP sensitizes cells to DNA breakdown/fragmentation from ionizing radiation involves direct interference with DNA repair proteins.18 Because studies suggest involvement of DNA breakdown by HG, further investigation is necessary to examine whether this phenomenon is potentiated by LOX-PP. Although the mechanisms of action on how LOX-PP overexpression triggers apoptosis are not well known, a recent study reported that LOX-PP can hinder cell proliferation, cell migration, cell attachment and can promote apoptosis in the endothelial cell by possibly arresting the cell cycle in the S phase and by reducing the phosphorylation of extracellular signal regulated kinase 1 and 2.42 However, further studies are needed to better understand this mechanism. Overall, our findings suggest a novel mechanism for HG-induced apoptosis that involves LOX-PP, which may be a potential therapeutic target in preventing retinal vascular cell loss associated with diabetic retinopathy.

Footnotes

Supported by National Eye Institute NIH grants EY025528 and EY027082 (S.R.).

Disclosures: None declared.

References

- 1.Fong D.S., Aiello L., Gardner T.W., King G.L., Blankenship G., Cavallerano J.D., Ferris F.L., 3rd, Klein R., American Diabetes Association Retinopathy in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27 Suppl 1:S84–S87. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wild S., Roglic G., Green A., Sicree R., King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engerman R.L. Pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 1989;38:1203–1206. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.10.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammes H.P., Lin J., Renner O., Shani M., Lundqvist A., Betsholtz C., Brownlee M., Deutsch U. Pericytes and the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2002;51:3107–3112. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li W., Yanoff M., Liu X., Ye X. Retinal capillary pericyte apoptosis in early human diabetic retinopathy. Chin Med J (Engl) 1997;110:659–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizutani M., Kern T.S., Lorenzi M. Accelerated death of retinal microvascular cells in human and experimental diabetic retinopathy. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2883–2890. doi: 10.1172/JCI118746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Podesta F., Romeo G., Liu W.H., Krajewski S., Reed J.C., Gerhardinger C., Lorenzi M. Bax is increased in the retina of diabetic subjects and is associated with pericyte apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1025–1032. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64970-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunha-Vaz J., Bernardes R. Nonproliferative retinopathy in diabetes type 2. Initial stages and characterization of phenotypes. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2005;24:355–377. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beauchemin M.L., Leuenberger P.M., Babel J. Retinal capillary basement membrane thickness in spiny mice (Acomys cahirinus) with induced and spontaneous diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol. 1975;14:560–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloodworth J.M., Jr. Diabetic microangiopathy. Diabetes. 1963;12:99–114. doi: 10.2337/diab.12.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hainsworth D.P., Katz M.L., Sanders D.A., Sanders D.N., Wright E.J., Sturek M. Retinal capillary basement membrane thickening in a porcine model of diabetes mellitus. Comp Med. 2002;52:523–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy S., Ha J., Trudeau K., Beglova E. Vascular basement membrane thickening in diabetic retinopathy. Curr Eye Res. 2010;35:1045–1056. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2010.514659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beltramo E., Buttiglieri S., Pomero F., Allione A., D'Alu F., Ponte E., Porta M. A study of capillary pericyte viability on extracellular matrix produced by endothelial cells in high glucose. Diabetologia. 2003;46:409–415. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roy S., Lorenzi M. Early biosynthetic changes in the diabetic-like retinopathy of galactose-fed rats. Diabetologia. 1996;39:735–738. doi: 10.1007/BF00418547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beltramo E., Porta M. Pericyte loss in diabetic retinopathy: mechanisms and consequences. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:3218–3225. doi: 10.2174/09298673113209990022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim D., Roy S. American Diabetes Association; Arlington, VA: 2015. Downregulation of lysyl oxidase expression rescues retinal endothelial cells from high glucose-induced apoptosis [abstract #672-P] 75th American Diabetes Association Conference, June 5–9, 2015, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bais M.V., Nugent M.A., Stephens D.N., Sume S.S., Kirsch K.H., Sonenshein G.E., Trackman P.C. Recombinant lysyl oxidase propeptide protein inhibits growth and promotes apoptosis of pre-existing murine breast cancer xenografts. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bais M.V., Ozdener G.B., Sonenshein G.E., Trackman P.C. Effects of tumor-suppressor lysyl oxidase propeptide on prostate cancer xenograft growth and its direct interactions with DNA repair pathways. Oncogene. 2015;34:1928–1937. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Min C., Zhao Y., Romagnoli M., Trackman P.C., Sonenshein G.E., Kirsch K.H. Lysyl oxidase propeptide sensitizes pancreatic and breast cancer cells to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111:1160–1168. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng Y., Wang X., Wang H., Yan W., Zhang Q., Chang X. Expression of the lysyl oxidase propeptide in hepatocellular carcinoma and its clinical relevance. Oncol Rep. 2014;31:1669–1676. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sethi A., Wordinger R.J., Clark A.F. Focus on molecules: lysyl oxidase. Exp Eye Res. 2012;104:97–98. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith-Mungo L.I., Kagan H.M. Lysyl oxidase: properties, regulation and multiple functions in biology. Matrix Biol. 1998;16:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ozdener G.B., Bais M.V., Trackman P.C. Determination of cell uptake pathways for tumor inhibitor lysyl oxidase propeptide. Mol Oncol. 2016;10:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kagan H.M., Li W. Lysyl oxidase: properties, specificity, and biological roles inside and outside of the cell. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:660–672. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grimsby J.L., Lucero H.A., Trackman P.C., Ravid K., Kagan H.M. Role of lysyl oxidase propeptide in secretion and enzyme activity. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111:1231–1243. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palamakumbura A.H., Jeay S., Guo Y., Pischon N., Sommer P., Sonenshein G.E., Trackman P.C. The propeptide domain of lysyl oxidase induces phenotypic reversion of ras-transformed cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40593–40600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406639200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palamakumbura A.H., Sommer P., Trackman P.C. Autocrine growth factor regulation of lysyl oxidase expression in transformed fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30781–30787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu M., Min C., Wang X., Yu Z., Kirsch K.H., Trackman P.C., Sonenshein G.E. Repression of BCL2 by the tumor suppressor activity of the lysyl oxidase propeptide inhibits transformed phenotype of lung and pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6278–6285. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez-Morgan N., Kirsch K.H., Trackman P.C., Sonenshein G.E. The lysyl oxidase propeptide interacts with the receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase kappa and inhibits beta-catenin transcriptional activity in lung cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:3286–3297. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01426-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato S., Trackman P.C., Maki J.M., Myllyharju J., Kirsch K.H., Sonenshein G.E. The Ras signaling inhibitor LOX-PP interacts with Hsp70 and c-Raf to reduce Erk activation and transformed phenotype of breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:2683–2695. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01148-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palamakumbura A.H., Vora S.R., Nugent M.A., Kirsch K.H., Sonenshein G.E., Trackman P.C. Lysyl oxidase propeptide inhibits prostate cancer cell growth by mechanisms that target FGF-2-cell binding and signaling. Oncogene. 2009;28:3390–3400. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chronopoulos A., Trudeau K., Roy S., Huang H., Vinores S.A., Roy S. High glucose-induced altered basement membrane composition and structure increases trans-endothelial permeability: implications for diabetic retinopathy. Curr Eye Res. 2011;36:747–753. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2011.585735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tien T., Muto T., Barrette K., Challyandra L., Roy S. Downregulation of Connexin 43 promotes vascular cell loss and excess permeability associated with the development of vascular lesions in the diabetic retina. Mol Vis. 2014;20:732–741. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Towbin H., Staehelin T., Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hurtado P.A., Vora S., Sume S.S., Yang D., St Hilaire C., Guo Y., Palamakumbura A.H., Schreiber B.M., Ravid K., Trackman P.C. Lysyl oxidase propeptide inhibits smooth muscle cell signaling and proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chronopoulos A., Tang A., Beglova E., Trackman P.C., Roy S. High glucose increases lysyl oxidase expression and activity in retinal endothelial cells: mechanism for compromised extracellular matrix barrier function. Diabetes. 2010;59:3159–3166. doi: 10.2337/db10-0365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liegler T.J., Hyun W., Yen T.S., Stites D.P. Detection and quantification of live, apoptotic, and necrotic human peripheral lymphocytes by single-laser flow cytometry. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2:369–376. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.3.369-376.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGahon A.J., Martin S.J., Bissonnette R.P., Mahboubi A., Shi Y., Mogil R.J., Nishioka W.K., Green D.R. The end of the (cell) line: methods for the study of apoptosis in vitro. Methods Cell Biol. 1995;46:153–185. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61929-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuwabara T., Cogan D.G. Studies of retinal vascular patterns. I. Normal architecture. Arch Ophthalmol. 1960;64:904–911. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1960.01840010906012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vora S.R., Palamakumbura A.H., Mitsi M., Guo Y., Pischon N., Nugent M.A., Trackman P.C. Lysyl oxidase propeptide inhibits FGF-2-induced signaling and proliferation of osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7384–7393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang X., Scott H.A., Monickaraj F., Xu J., Ardekani S., Nitta C.F., Cabrera A., McGuire P.G., Mohideen U., Das A., Ghosh K. Basement membrane stiffening promotes retinal endothelial activation associated with diabetes. FASEB J. 2016;30:601–611. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-277962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nareshkumar R.N., Sulochana K.N., Coral K. Inhibition of angiogenesis in endothelial cells by Human Lysyl oxidase propeptide. Sci Rep. 2018;8:10426. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28745-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]