Key Points

A mixed methods study of surveys, interviews, and focus groups raises concerns about the state of the adult hematology workforce.

Hematology/oncology fellowship program directors, fellows, and practicing clinicians offer different strategies to address these problems.

Abstract

The current demand for adult hematologists in the United States is projected to exceed the existing supply. However, no national study has systematically evaluated factors affecting the adult hematology workforce. In collaboration with the American Society of Hematology (ASH), we performed a mixed methods study consisting of surveys from the annual ASH In-Service Exam for adult hematology/oncology fellows from 2010 to 2016 (8789 participants); interviews with graduating or recently graduated adult hematology/oncology fellows in a single training program (8 participants); and 3 separate focus groups for hematology/oncology fellowship program directors (12 participants), fellows (12 participants), and clinicians (10 participants) at the 2016 ASH annual meeting. In surveys, the majority of fellows favored careers combining hematology and oncology, with more fellows identifying oncology, rather than hematology, as their primary focus. In interviews with advanced-year fellows, mentorship emerged as the single most important career determinant, with mentorship opportunities arising serendipitously, and oncology faculty perceived as having greater availability for mentorship than hematology faculty. In focus group discussions, hematology, particularly benign hematology, was viewed as having poorer income potential, research funding, job availability, and job security than oncology. Focus group participants invariably agreed that the demand for clinical care in hematology, particularly benign hematology, exceeded the current workforce supply. Single-subspecialty fellowship training in hematology and the creation of new clinical care models were offered as potential solutions to these workforce problems. As a next step, ASH is conducting a national, longitudinal study of the adult hematology workforce to improve recruitment and retention in the field.

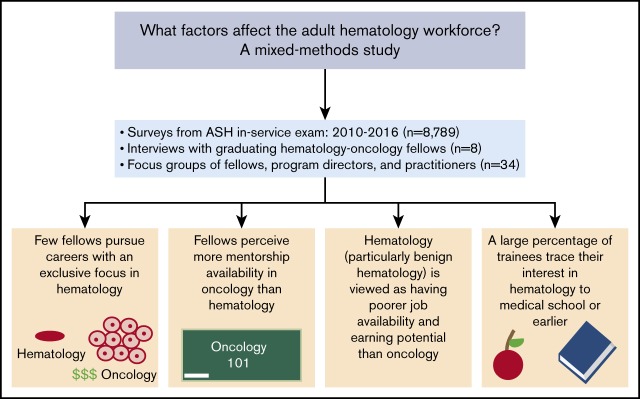

Visual Abstract

Introduction

In recent years, the American Society of Hematology (ASH) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute have expressed concern that the supply of trained hematologists in the United States has been falling short of the increased demand for patient care.1-3 A landmark study commissioned by the American Society of Clinical Oncology predicted that by 2020, the growth in demand for hematology/oncology services would far outpace the growth in supply of new providers entering the workforce.4,5 A 2015 survey administered to over 6000 ASH members engaged in clinical practice indicated that, of 689 respondents, 13% planned to retire in the next 5 years, with more than one-half of respondents’ practices engaged in recruiting new physicians (ASH and Readex Research, unpublished survey of practice-based hematologists, 2015). Workforce deficits in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and in the hematology research workforce, particularly in benign hematology, have also been predicted.6-8

According to the American Medical Association Physicians Masterfile database, each year from 2004 to 2010, the number of physicians identifying as hematologists was far outnumbered by the number of medical oncologists.9 Although the number of fellows seeking dual hematology and oncology training and certification rose during this time frame, those pursuing single-subspecialty training in either subspecialty dropped, with the number of oncology-only fellows being double or triple that of hematology-only trainees. A 2003 survey of hematology/oncology fellowship program directors estimated that <6% of graduates of adult training programs pursued careers in benign hematology.10

In an ASH survey of practice-based hematologists (2017), 74% of practicing hematologists indicated that the volume or complexity of benign hematology patients in clinical practice exceeded or would eventually exceed what could be accommodated by the current workforce supply, whereas almost one-third of respondents characterized prospective job candidates as being inadequately trained in benign hematology.11 Other data suggest that these workforce problems are restricted to adult, rather than pediatric, hematology, with the latter being affected by geographic disparities in the number of available providers and an expansion of advanced practice providers over recent years.12-14

Large-scale surveys have identified several factors in the adult hematology workforce that may be contributing to these trends in the selection of careers focused in hematology vs oncology and in academics vs private practice. These factors include clinical and research exposures during medical school, residency, and fellowship, in addition to concerns about lifestyle, financial compensation, research funding, mentorship, and hiring potential.15,16 To date, no national study has systematically evaluated these factors in the adult hematology workforce, a requisite step for improving the supply-and-demand ratio of hematologists and, ultimately, access to hematology care.

In other fields facing similar threats of workforce shortages, qualitative or mixed methods studies have yielded unique insights into specific factors guiding the career decision-making process.17,18 To better understand these factors and their potential impact on the adult hematology workforce, we performed a mixed methods study in collaboration with ASH, consisting of survey data from the annual ASH In-Service Exam for adult hematology/oncology fellows; interviews with graduating adult hematology/oncology fellows; and a series of focus group discussions conducted at the 58th annual ASH meeting in 2016 that included program directors of adult hematology/oncology fellowships, practicing adult hematologists, and adult hematology/oncology fellows from across the United States.

Methods

Overall study design

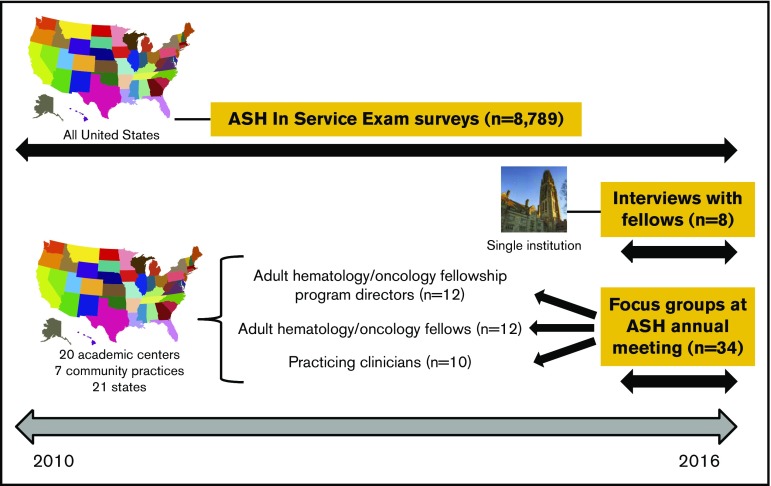

The overall study design is shown in Figure 1. There were 3 distinct phases of data collection:

Survey data from the annual ASH In-Service Exam (2010-2016) for first to fourth year fellows in adult hematology/oncology training programs in the United States, consisting of multiple choice questions.

Interviews with graduating adult hematology/oncology fellows at a single academic institution in the northeastern United States.

Three separate focus group discussions with adult hematology/oncology fellowship program directors or associate program directors, practicing clinicians who self-identified as hematologists or hematologists/oncologists, and adult hematology/oncology fellows conducted at the 58th annual ASH meeting in San Diego, CA, in 2016.

Figure 1.

Overview of study design. The objectives of this study were to: (1) identify factors that influenced adult fellows to choose careers in hematology and oncology; (2) define the timing during the course of medical and graduate education when trainees decide to pursue careers in hematology and oncology; and (3) identify trends in preferences and plans for practice after fellowship. Data were obtained from 3 sources: (1) ASH In-Service Exam surveys, administered annually to all adult hematology and hematology/oncology fellows in the United States from 2010 to 2016, with a total of 8789 participants during the study period; (2) interviews with graduating and recently graduated adult hematology/oncology fellows at a single hematology/oncology fellowship program in the northeastern United States (n = 8); and (3) 3 focus groups held at the ASH annual meeting in December 2016, involving program directors (n = 12), adult hematology/oncology fellows (n = 12), and practicing adult hematology/oncology clinicians (n = 10) from a mix of academic centers and community programs in 21 states.

ASH In-Service Exam survey questions

The ASH In-Service Exam is a 1-day test administered annually to fellows in all adult hematology and hematology/oncology training programs in the United States, for the purposes of programmatic and self-assessment in hematology. Each year, the examination concludes with a set of survey questions asking fellows about their career interests in hematology and oncology, their preferred types of jobs after fellowship, and other motivating professional factors; survey questions are shown in supplemental Table 1. With few exceptions, the survey questions have remained constant each year for almost a decade. We compiled and analyzed yearly ASH In-Service Exam survey data from 2010 to 2016, with a total of 8789 respondents over the study period.

Interviews with graduating hematology/oncology fellows

Semistructured interviews lasting between 30 and 90 minutes were conducted with hematology/oncology fellows in an adult hematology/oncology training program at a single academic institution in the northeastern United States (with which several of the authors of this paper were affiliated) in mid-2016. Participating fellows were in their last year of training or had graduated within the preceding year. All interviews were conducted by 1 investigator (N.W.) who received training in qualitative interview techniques prior to the first interview. Interview questions prompted fellows to reflect on their clinical and research exposures before and during fellowship, mentorship opportunities, factors that shaped their career decision-making processes, and impressions of careers in hematology and oncology; interview questions are shown in supplemental Table 2. Interviews were recorded using an iPhone and the recordings transcribed with the permission of the participants. Interview transcripts were reviewed independently by N.W. and A.I.L. according to Miles et al19; themes emerging from each interview were identified and agreed upon. Institutional review board exemption was obtained for this portion of the study.

Focus group discussions at the 2016 ASH annual meeting

Three focus group discussions, each lasting 2 hours, were held during the 58th annual ASH meeting in San Diego, CA, in December 2016. One was open to adult fellowship program directors and associate program directors and another to practicing clinicians who self-identified as hematologists or hematologists/oncologists; for these sessions, e-mail invitations were sent to prospective participants across the United States using e-mail addresses obtained from ASH databases. A third focus group was open to hematology/oncology fellows in adult training programs in the United States; for this session, prospective participants were identified through e-mails sent to fellowship program directors asking them to recommend fellows who they felt would be willing to participate and provide thoughtful commentary. Each focus group discussion was led by 2 investigators (N.W. and either N.A.P. or A.I.L.) who received training in conducting focus groups beforehand. Participants were asked to comment on such varied topics as individual career trajectories, major or minor career-defining or career-shaping factors, perceptions about hematology as a field, job opportunities in hematology, scope of clinical practice in hematology, adequacy of fellowship training for clinical practice in hematology, and factors that might improve recruitment to or retention in hematology; representative focus group questions are shown in supplemental Tables 3-5. All sessions were video-recorded. Dialogue for the fellowship program directors’ session was transcribed; poor sound quality precluded transcription of the other focus group sessions although detailed notes were taken by the interviewer and 1 investigator during those sessions. Two investigators (N.W. and A.I.L.) performed content analysis, and themes from all focus group discussions were identified and agreed upon by both.

Results

ASH In-Service Exam survey data, 2010-2016

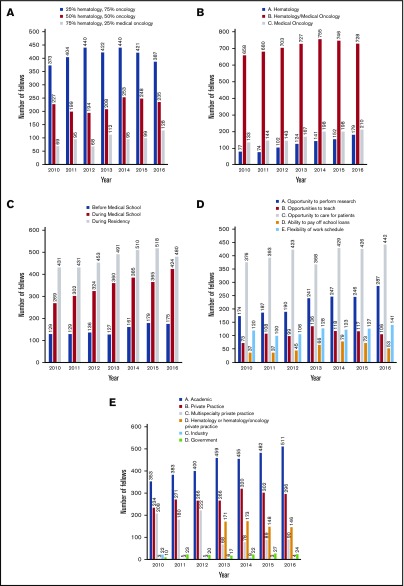

The results of ASH In-Service Exam survey questions from 2010 to 2016, administered to 8789 fellows in adult hematology and hematology/oncology training programs in the United States, are shown in Figure 2. Slightly over one-quarter of respondents were first-year fellows, with the remainder roughly evenly distributed between second and advanced-year fellows. The total number of fellows who completed the survey increased by 42.4% between the first and last year of the study, reflecting an overall increase in the number of trainees (data not shown). The majority of fellows favored careers that combined hematology and oncology and envisioned medical oncology as comprising ≥50% of their efforts (Figure 2A). The percentage of all fellows who identified hematology, rather than oncology, as their primary focus was consistently below the percentage of oncology-leaning fellows, although over time, the gap between these 2 groups shortened (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Survey data from the ASH In-Service Exam for hematology and hematology/oncology fellows, 2010-2016. (A) Anticipated percentage of eventual career practice comprised by hematology versus oncology. (B) Anticipated primary career focus. (C) Timing of when fellows made decisions to pursue careers in hematology and oncology. (D) Most critical factor in making decisions about choice of subspecialty. (E) Anticipated employment settings after completion of fellowship (asterisk [*] denotes missing data for years 2011 and 2012).

The ASH In-Service Exam survey also asked questions about when trainees decided on their subspecialties and what some of the motivating factors were in those decisions. Approximately 40% of fellows decided on their subspecialty during residency, whereas one-quarter to one-third decided during medical school, and ≤15% decided before medical school (Figure 2C). Patient care, followed by research opportunities, comprised the top 2 most common motivating factors in guiding fellows’ career decisions (Figure 2D). Approximately 40% of fellows planned on going into academic medicine after fellowship whereas ≥40% planned on private practice careers (Figure 2E).

Interviews with fellows

Interviews were performed with 8 adult hematology/oncology fellows at a single academic institution, addressing their career interests and perceptions of careers in hematology. At the time the interviews were conducted, this program’s curriculum was structured such that focused hematology training largely occurred during the second year of training; a T32 training grant offering protected research time in hematology was available. Of the 8 fellows interviewed, 5 were in their senior year of training, whereas 3 had just graduated. Five were female. Three held dual MD and PhD degrees. Most were planning on an academic career, with 2 specifically pursuing careers in malignant or benign hematology. Most interviewees were able to identify seminal, career-defining experiences prior to medical school that shaped both their professional development and their overall interest in hematology and/or oncology. In general, fellows were not strongly differentiated at the start of their fellowships with respect to either hematology or solid tumor oncology, but by the end of their first year, 6 had decided to pursue careers in solid tumor oncology owing to increased clinical exposure and research opportunities in the field.

Trainees’ career decisions and perceptions of hematology revolved around 6 major themes: mentorship, serendipity, clinical exposure and teaching, intellectual interest, lifestyle, and financial factors. Representative quotes supporting these themes are shown in Table 1. Mentorship emerged as the single most important career determinant, although mentorship opportunities tended to occur serendipitously, with fellows identifying more availability of mentorship among faculty in medical oncology than in hematology. Trainees viewed hematology as having a less desirable work/life balance than solid tumor oncology, and their experiences on the inpatient hematology services caused some of them to feel burned out. Fellows also viewed hematology as having lower earning potential and fewer funding opportunities in comparison with medical oncology. Despite these negative perceptions, however, many fellows commented that hematology cases involved more complex and challenging disease pathology than medical oncology.

Table 1.

Hierarchical themes identified in fellows’ interviews as having an impact on guiding individual career decisions

| Theme | Interpretation | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Mentorship | Mentorship is the single most important factor guiding fellows’ career decisions | • On the single most important factor in choosing a career: “I would definitely say mentors.” |

| • “Mentors play a huge role because you want to be like them. The cases you see, the change of life, and stuff like that.” | ||

| • “When it comes down to choosing specifically between heme and onc, I think a lot of it comes down to the availability of the mentorship … that’s essentially what makes anybody go into anything.” | ||

| Serendipity | Many mentorship opportunities and career-defining factors occur serendipitously | • “It was serendipitous that I got a good job in a lab that studies cancer right after college at the NIH.” |

| • “The fact that I found someone here who had an interest in [my particular field of] research was completely happenstance.” | ||

| • “I went to a lot of different clinics and I felt like [1 attending] really taught me. He really offered to mentor me and give me good research projects … It was random from me picking attendings to go to their clinics.” | ||

| Clinical exposure and teaching | The distribution of clinical exposure to inpatient and outpatient hematology and oncology may impact fellows’ interests | • “We don’t start thinking about hematology until our second year. By second year, you already have your preferences so you are primarily exposed just to oncology and you don’t have hematology exposure. By the time you are doing hematology you have already picked stuff and you are already thinking about your project… You kind of decide on oncology early on and you don’t really think about hematology and then you get burned out during 6 months [of continuous hematology] and you just really don’t want to do that.” |

| • “So much more time in terms of [fellowship] training months is dedicated toward medical oncology. If you really want someone to go into heme, then [the way our fellowship program is structured] is not really a great way to personalize your fellowship.” | ||

| • From a fellow going into oncology: “I did a fair amount of inpatient hematology. My outpatient experience was more in medical oncology. I think that’s also what made a difference. Inpatient, you see more of the sick patients, and you get caught up with their day-to-day issues … whereas outpatient you really get to focus more on the disease, the onc part of things.” | ||

| Intellectual interest | Regardless of career plans, fellows view hematology as an intellectually interesting and complex field | • “I actually think hematologists are considered to be much smarter than medical oncologists in general.” |

| • “I think the [hematology] patients are much more complex, more acute … With the benign [hematology] I just think it’s a mystery, it’s cool.” | ||

| • “I think [in] hematology you need to be smarter” [than in oncology]. | ||

| • “This is going to sound weird, but I really liked hematology more … [even though] realistically thinking, for the rest of your life, the field is just not for me.” | ||

| Lifestyle factors | Fellows view hematologists as having a worse work-life balance than solid tumor oncologists | • “I think in hematology, the work-life balance is just more towards work because of the acuity of the patients … You see the acute leukemics that come in in the middle of the night, whereas, in oncology, I feel like there’s a better work-life balance.” |

| • “I think being forced to go into the hospital on call for every single acute leukemic whether they were stable or not absolutely discouraged me from going into heme.” | ||

| • “All hematology attendings, they are definitely burned out … They are working from 7:00 AM until really, really late … If you are starting a family and having a kid, it is really hard to imagine that you are going to be able to do that. I think it’s better in oncology.” | ||

| Financial factors | Fellows view hematology as having lower earning and funding potential than solid tumor oncology | • “Benign heme is kind of the one that takes a lot of time and isn’t that well reimbursed.” |

| • “My impression is that hematologists … tend to be less well-funded than oncology departments … They don’t have as many people, they don’t have as much stuff, they don’t have as much support.” |

Six overarching themes were identified: mentorship, serendipity, clinical exposure and teaching, intellectual interest, lifestyle factors, and financial factors. Representative quotes are shown for each theme.

heme, hematology; lab, laboratory; NIH, National Institutes of Health; onc, oncology.

Focus groups

Three focus groups addressing topics pertinent to the hematology workforce were assembled at the 58th annual ASH meeting in San Diego, CA, in 2016: 1 for adult hematology/oncology fellowship program directors or associate program directors (12 participants), another for adult hematology/oncology fellows at all stages of training (12 participants), and a third for practicing adult hematologists/oncologists (10 participants). Participants came from a variety of institutions, cancer centers, and practices, representing a total of 21 states and all geographic regions in the United States (a complete list of participants is included in “Acknowledgments”). Participating program directors and fellows were a diverse group with varying research and clinical interests, whereas the practitioners’ group consisted of individuals from both academic- and community-based programs who were identified as spending ≥80% of their time in clinical care. Information regarding demographics, training, and subspecialty certification of participants is included in supplemental Table 6.

Several themes emerged from the focus group discussions; these are shown in Table 2, with supporting quotes from the fellowship program directors’ session. Invariably, all participants believed that the demand for clinical care in hematology, particularly benign hematology, was greater than the current workforce supply; this perspective was shared by fellowship program directors and associate program directors, fellows, and practicing hematologists alike, at both research- and community-oriented practices. Participants differed in their view of how many current fellows leaned toward hematology compared with solid tumor oncology, although at every training program, the number of fellows with a specific interest in benign hematology was very small. Compared with solid tumor oncology, hematology and, in particular, benign hematology, was viewed as having poorer income potential and research funding opportunities, with lower job availability and job security as well.

Table 2.

Themes identified in focus group discussions about the hematology workforce with adult hematology/oncology fellowship program directors

| Theme | Interpretation | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Demand for hematology services | There is a perception that the demand for clinical care in hematology, particularly benign hematology, exceeds the current workforce supply | • “I was told recently that we had 600 new patient referrals in 6 months for benign hematology. That’s 100 new patients per month and I think there are 5 of us with variable numbers of clinics. And so you can do the math. There is a need for benign hematologists.” |

| • “[Our institution is] seeing this huge influx of [hematology] consults and outpatient referrals because the [organization] doesn’t want the nurse-practitioner to be wasting their time working at anemia or thrombosis and anticoagulation management so they’re coming to us actually. So we’ve had to create a rapid access clinic and a lot of new infrastructure to manage this influx. I don’t know if this is all going to change with the new administration. There is a need, and the workload is there.” | ||

| • “Within my practice, the hematology practice has grown exponentially while oncology is staying stable.” | ||

| • On the clinical workload in benign hematology: “We all need help.” | ||

| Trainee interest in hematology vs solid tumor oncology | The numbers of fellows interested in hematology vs solid tumor oncology vary according to institution, but invariably only a small number are interested specifically in benign hematology | • “The biggest problem that we have been having is actually retaining and maintaining people for growing … benign hematology. Malignant hematology has not held much [of a] problem, at least for our institution.” |

| • “Way back when I first worked … we didn’t have too much trouble tracking fellows to malignant … but benign has … much more of a challenge.” | ||

| • “[A] small minority [of our fellows] consider hematology, which is surprising because we have 1 of the largest, I would say most vibrant hematology faculty and research program diversity around the country.” | ||

| • “We do not turn out a lot of hematologists, I think in part because we don't actually have a full-time coagulation … faculty right now …. We [do] have a large hemoglobinopathy program. We keep trying to get people interested in sickle cell and sickle cell care to even join faculty and it’s been a really tough sell for a lot of people and that’s definitely been a real problem.” | ||

| • “The fellows who opt to train in hematology comprise probably anywhere from 30% to 50% of our fellows.” | ||

| • “I would say 50% of our fellows are interested in malignant hematology and about 1 or 2 also in benign hematology.” | ||

| Job availability and security | Hematology is perceived as having lower job availability and security compared with solid tumor oncology | • “I think the problem with general hematology is that … even fellows that are very well trained in general hematology are very concerned about job opportunities down the road, [whereas] they see job security in solid tumor oncology.” |

| • “I have fellows that would love to do hematology. And I could train them to be a hematologist, but then they could not find jobs.” | ||

| • “People do want to become hematologists. They love it…. They love hematology, but ultimately they are told by program directors, by peers, by other people that they cannot make a career on this.” | ||

| • “So if the jobs [in hematology] exist, the message with the trainees is that they don’t exist. That’s a big problem.” | ||

| • “There’s mixed messages that either there will not be a job for me or somebody else who is not a hematologist will be able to do my job…. And so it’s hard to reconcile these mixed messages.” | ||

| Financial factors | Hematology, particularly benign hematology, is perceived as being associated with a lower income potential, with fewer research funding opportunities, than solid tumor oncology | • “[The fellows] love heme because of all of the things that we’ve talked about, but the financial and other pressures are preventing them from doing that.” |

| • “Naturally, we’ve got a huge push for cancer. So you’re not going to get your CEO and all those people to say, ‘We’re going to put more money in hematology’ … Because they know that the money [comes] from cancer.” | ||

| • “I think also that funding is not available [in benign hematology]. So I think we should really come up with ideas on how to improve that and have more funding to benign hematology. Because that’s not where the money is.” | ||

| • “One of the challenges is … that at the end of the day it comes to money, and I think a lot of that is also funding. It becomes a circular problem where our benign hematologists are really mostly doing clinical practice. And they’re so overwhelmed with the clinical workload… Overcoming that, getting critical mass [so that benign hematologists are] able to do research is important, but getting them to do that really probably also has to do with funding. With oncologists, there’s a fair amount of funding through trials, through different malignancy-oriented research [opportunities] that don’t exist in the same way for benign hematology.” | ||

| • “There’s fewer ways to offset the salary for a benign hematologist than there is an oncologist. They all just have investigator-sponsored trials, they offset their salaries, get thrown in more administrative things, but [to] say there’s a job for a benign hematologist [with] 10 [clinics] a week is not necessarily an appealing thing to give somebody.” | ||

| Timing of career decisions | Trainees may develop an interest in hematology at any point along their training pathway, although some fellows switch from hematology to solid tumor oncology during fellowship | • “[An interest in hematology] starts in medical school and it goes through residency.” |

| • “Something happens during fellowship that changes people who passionately wanted to do hematology into [saying], ‘Well solid tumor isn’t that bad and I could do that and still do some hematology on the side.’ That’s what happens during fellowship.” | ||

| • “I think the people who choose to do benign hematology choose early from medical school and from residency based on ventures for laboratory based and academics…. I can identify [those interested in benign hematology] from moment 1…. They don’t waver from that. It’s … the malignant people [who] may decide to do solid tumors.” | ||

| • “I think that a disproportionate number of [fellowship] applicants are interested in malignant hematology and then during fellowship they see the landscape a little bit more clearly and get switched to solid tumor oncology.” | ||

| Single-subspecialty training in hematology | Single-subspecialty training in hematology may improve the hematology workforce, although this may not be universally feasible | • “If we had a program that could dissect out heme-only and really offer the curriculum that does not require them to be exposed to the solid tumor biology of having a combined heme/onc program, I think we’d be more successful in training really good heme malignancies as well as nonmalignant heme folks who might want to do everything short of transplant.” |

| • “If we could … stop telling our fellows that they cannot choose hematology only, I think those proportionate people would want to single board [in hematology]. Benign hematology is very different in many respects than solid oncology.” | ||

| • When asked how to produce more trainees in hematology if provided with unlimited resources: “I would create a fellowship program solely for heme.” | ||

| • When asked how to produce more trainees in hematology if provided with unlimited resources: “I’d go the clinician route and create a track for the fellows who want to be excellent hematologists out in the community and lead teams with physician extenders out in the community.” | ||

| • “We asked our institution if they would support the addition of 2 additional fellows for [a] hematology-only program. Two per year, so we have 4 total for a 2-year hematology fellowship…. We’re already way above our debt-to-resident ratio cap and absolutely not …. It’ll never happen.” | ||

| New care models for clinical practice in hematology | There is a demand for new care models to support community-based hematology practices | • “We have 4 hematologists in my practice [in the community] and 10 oncologists, and we hematologists see benign and malignant; the oncologists see only solid tumor. But there’s very few that I’m aware of, programs that are like that outside of the university setting. So that’s where I would see the future of hematology going, is somehow being able to incorporate clinical hematology into more community settings, because that’s what the fellows want to do, that’s what they enjoy doing… So we need to have more jobs like I have which is where I’m a hematologist in the community.” |

| • “All of the big cancer centers are now diving into the community and eating up all of these community hospitals, and we have a lot of places that we’re struggling to figure out what should the training be there, who should be taking care of those patients, and I think that would be a great opportunity to have programs that are affiliated with a bigger academic place, but really train people to interface and be in those communities.” | ||

| • “It’s been interesting, because we do a lot of outreach in [a certain geographic] area, and there are several places where we send an oncologist 1 day and a hematologist the other day, and the hematologist is always twice as busy as the oncologist.” | ||

| • “We’re an academic fellowship. And all of our fellows we expect are going to stay in academics. We don’t have a clinician-clinician pathway, but we’re really thinking about do we need to create this? And then how are we going to fund it, because our fellows’ 2 years of research is all on training grants. We’ll actually have to create [a] funding mechanism for a clinician-clinician pathway. But we might have to do that if the pressures continue.” |

Seven themes were identified: demand for clinical hematology services, trainee interest in hematology vs solid tumor oncology, perceptions of job availability and security, financial factors, timing of career decisions, the prospect of single-subspecialty training in hematology, and the creation of new care models for clinical practice in hematology. Representative quotes are shown for each theme.

CEO, chief executive officer.

Participants had differing responses upon being asked when in the course of their training they developed an interest in hematology; some thought that this began early, during medical school or residency, whereas others thought that critical career decisions did not take place until midway through fellowship. Some indicated that fellows who were initially hematology-bound shifted their interests to medical oncology during fellowship for unclear reasons. Strong mentorship and role modeling were key to stimulating career interest as early as medical school but were perceived as being comparatively lacking in hematology compared with medical oncology. There was a perception that fellowship training experiences placed a disproportionate emphasis on medical oncology, with the hematology portion of training being largely focused on malignant rather than benign hematology. Fellowship program directors and practicing physicians expressed concern about whether current hematology/oncology fellows were being adequately trained for clinical practice in hematology.

Some program directors thought that hematology as a field should reclaim “ownership” over certain endeavors that used to be exclusively under its purview (eg, laboratory medicine, coagulation, thrombosis). Some wondered whether discussions about the hematology workforce should include both benign and malignant hematology, the latter having been ceded over to medical oncology at some academic centers. Some suspected that the historical merger of hematology and medical oncology fellowship programs disproportionately benefited solid tumor oncology at the expense of hematology. Single-subspecialty training in hematology was brought up by many participants as a possible solution to these problems, although some challenged the feasibility and universality of this approach. Program directors and practitioners also thought that there was a demand for new clinical care models for practice in hematology, including systems-based hematology and novel reimbursement structures to support benign hematology in community practices. All participants believed that ASH could play a major role in supporting these issues and that a systematic study of the US hematology workforce should be undertaken.

Discussion

Fellows’ perceptions of careers in hematology

Using a combination of ASH In-Service Exam survey data, qualitative interviews with adult hematology/oncology fellows, and focus group discussions with fellowship program directors, fellows, and practicing adult hematologists, we found that there are widespread concerns about the present and future state of the hematology workforce shared by many individuals in the field. The biggest threats appear to be to benign hematology, with quantitative and qualitative analyses suggesting only small numbers of fellows entering the workforce in benign hematology despite a high clinical demand at academic centers and community practices alike. Of interest, both a 2003 survey study of hematology/oncology fellowship program directors and a 2018 single-institution study of former hematology/oncology fellows found only 5% to 6% of fellows to be interested in careers in benign hematology, indicating that the workforce problem in benign hematology has been longstanding.10,16

In the ASH In-Service Exam surveys, more fellows consistently identified medical oncology over hematology as a primary career focus. In interviews and focus groups, hematology/oncology fellows perceived hematology as a field associated with reduced job availability and security, lower earning potential, fewer research funding opportunities, and a less favorable work/life balance compared with medical oncology. Nationally, objective data regarding the availability of jobs in benign and malignant hematology, both in academics and in private practice, as well as average salaries associated with these positions, are currently lacking. The unavailability of this information is a consistent source of concern for the fellows, program directors, and practicing hematologists who were interviewed for this study and is critical to guide trainees to make informed decisions about their plans for practice after completion of fellowship.

Timing of development of trainees’ career interests and implications for early recruitment

ASH In-Service Exam surveys and qualitative data suggest that hematology/oncology fellows make decisions about their career interests at all stages of their training: before medical school, during medical school and residency, and after starting their fellowships. An unexpectedly large percentage of trainees trace their interests in hematology or oncology to medical school or earlier, whereas critical career decisions and sometimes career changes also occur during fellowship. In the surveys, patient care and research opportunities represent 2 major factors guiding trainees’ career decisions, whereas in fellows’ interviews and focus group discussions, mentorship emerges as the single most important career determinant. These data suggest that early exposure to hematology mentors and clinical rotations may be key for the recruitment of trainees into the field.

In interviews and focus group discussions, there is a general impression that trainees drawn to benign hematology may have different motivating factors than those interested in malignant hematology or solid tumor oncology. Hematology/oncology fellowship programs are often perceived as placing greater emphasis on medical oncology rather than hematology training, with practicing physicians raising the concern that current graduates may be inadequately prepared for real-world clinical practice in hematology. Some fellowship program directors believe that the merging of hematology and medical oncology training may disproportionately benefit medical oncology over hematology. Currently, the American Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) specifies that for combined hematology/oncology fellowships, 12 months of clinical training should be dedicated to neoplastic diseases including hematologic malignancies, whereas 6 months should be devoted to benign hematology and 1 month to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. However, it is uncertain how exactly different fellowships implement these requirements.20 Taken together, these observations highlight a need for a systematic review of fellows’ educational experiences to ensure that clinical requirements for combined hematology/oncology training programs are not being implemented in ways that jeopardize hematology as a field.

Single-subspecialty training in hematology

In focus group discussions, the prospect of expanding the number of single-subspecialty training programs in hematology is offered by many fellowship directors as a potential solution to the workforce problem, although the feasibility and necessity of this is challenged by some. The conceptual linkage of hematology with medical oncology traces back several decades, when the fields were historically viewed as 1 discipline, with expertise in both fields being critical to managing bone marrow suppression and other hematologic complications of chemotherapeutic treatment regimens.21 In the 1970s, investigators with an interest in medical oncology began to distinguish themselves from those specializing in thrombosis and other nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Of interest, a recent study from Johns Hopkins, which has a combined hematology/oncology fellowship program with an option for single-subspecialty training in either discipline, has observed a high rate of recruitment to and retention in hematology among fellows who pursue the hematology-only training pathway.22

According to ACGME data, the number of fellows in combined adult hematology/oncology fellowship training programs in the United States has grown steadily over the last several years, with 1414 fellows in 2010 compared with 1745 fellows during the 2017-2018 academic year, representing a total of 149 programs. During this same time period, the number of single-subspecialty training programs in hematology dropped from 3 to 2 and the number of oncology training programs from 9 to 7, indicating that the vast majority of fellowship training takes place in combined hematology/oncology settings. Our focus group data, combined with the greater number of programs available for single boarding in oncology, suggest that the overall output of these programs may be heavily skewed toward medical oncology. Interestingly, trends from the American Board of Internal Medicine demonstrate that, from 2011 to 2018, the number of certificates given for oncology boarding was higher than for hematology boarding (mean of 426 per year for hematology, vs 559 per year for oncology).23

Anecdotally, the concept of single-boarding in oncology has long been accepted at many training programs as a viable career option, but there are no data documenting the number of fellows who initially enroll in combined hematology/oncology fellowship programs and subsequently decided to truncate their training and single-board in either subspecialty. The negative perceptions of hematology to which fellows are exposed during their training, as identified during our interviews and focus group sessions, suggest that fellows may be dissuaded from pursuing hematology-focused training.

An expansion in the number of standardized single-subspecialty training programs in hematology might attract different candidates than the current combined application pool and potentially become a powerful intervention to bolster the hematology workforce. However, the feasibility of implementing such programs is unclear and associated with multiple challenges, including the paucity of faculty with specific expertise in benign hematology at some centers, and the fact that many combined hematology/oncology program directors are board-certified only in medical oncology (50 of 144 as of 2019, compared with 13 program directors certified in hematology alone) and may therefore be less familiar with the requirements for implementing single-boarding options in hematology. Also, although more fellows in the ASH In-Service Exam surveys consistently identify medical oncology, rather than hematology, as their primary career focus, the gap for the 2016 year is smaller than for other years, and our qualitative data indicate that individuals are divided as to whether their concerns about the hematology workforce extend to malignant hematology, as several training programs appear to be quite successful at recruiting fellows interested in malignant hematology. The potential implications of these disparate trends on the development of single-subspecialty fellowship training in hematology, and on the overall hematology workforce, are uncertain.

New clinical care and reimbursement models in hematology

In addition to increasing the number of single-boarding programs in hematology, many focus group participants advocate for the development of new clinical care models to support those with clinical expertise in hematology, both in academia and in the community. One such initiative is the development of alternative career pathways in hematology, including the implementation of systems-based hematology programs under the direction of hematologists who navigate through multiple different clinical care systems.1 Another is the creation of novel reimbursement models for benign hematology in community practices. Although practicing clinicians universally endorse a high demand for clinical expertise in benign hematology in the community, it is uncertain whether revenue generated by patient care alone can sustain such a level of subspecialization in the community without supplemental funding from chemotherapy and other treatments used in malignant hematology and solid tumor oncology. Given the repeated concerns from fellows in our focus groups and surveys about reimbursement for hematologists, particularly benign hematologists, future studies to formally evaluate the feasibility of new reimbursement systems and systems-based hematology programs are warranted.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to this study. One is the potential for sampling error; only 1 institution was selected for interviewing fellows whose perspectives might have been shaped by factors unique to that institution. Additional interviews at other institutions would be helpful in this regard. In our focus group discussions, we attempted to minimize sampling error by including participants from a broad array of institutions and geographies, although there was an overrepresentation of east coast programs in all 3 focus group sessions. Lastly, the different types of data collection methods used distinct inclusion and exclusion criteria, which limited to some extent the ability to directly compare and contrast some of the findings from these different sources.

A call to arms for a hematology workforce study

In summary, through quantitative and qualitative data, we find ample evidence of widespread concerns about the current and future status of the hematology workforce in the United States, particularly in benign hematology. In our current era of a growing shortage of adult hematologists to care for patients with complex medical conditions and to train the next generation of young hematologists, the time is ripe to ask critical questions to address these problems. In response to our study findings, ASH is embarking on a multiyear study of the US hematology workforce to assess the current and future state of hematology as a profession and in clinical practice, research, and training, with the goal of preserving and furthering the field.

Supplementary Material

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the numerous individuals who generously dedicated their time to participate in the discussions comprising this manuscript: Hanny Al-Samkari, Dana-Farber Cancer Center, Boston, MA; Nadia Ali, Rutgers, New Brunswick, NJ; Kamila Cisak, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY; Jennifer Cultrera, Florida Cancer Specialists & Research Institute, Eustis, FL; William DeRosa, Regional Cancer Care Associates, Morristown, NJ; Reed Drews, Beth Israel Deaconess, Boston, MA; Jennifer Faig, Beth Israel Deaconess, Boston, MA; Jason Freed, Beth Israel Deaconess, Boston, MA; Joanne Filiko-O’Hara, Jefferson, Philadelphia, PA; Morie Gertz, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN; Mark Heaney, Columbia, New York, NY; Irene May-ling Hutchins, Scripps, San Diego, CA; Maria Juarez, Baylor Scott & White Cancer Institute of Dallas, Duncanville, TX; Goetz Kloecker, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY; Ann LaCasce, Dana-Farber Cancer Center, Boston, MA; Ang Li, University of Washington, Seattle, WA; Michael Linenberger, University of Washington, Seattle, WA; Sam Merrill, Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, MD; Julianna Perez-Botero, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN; Tabraiz Mohammed, Mercy Rockford, Huntley, IL; Barbara Pro, Northwestern, Chicago, IL; Rakhi Naik, Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, MD; Taizo Nakano, University of Colorado, Denver, CO; Taral Patel, Zangmeister Cancer Center, Columbus, OH; Lori Rosenstein, Gundersen Health, La Crosse, WI; Appalanaidu Sasapu, University of Arkansas, Little Rock, AR; Charles Schiffer, Wayne State, Detroit, MI; Deva Sharma, Vanderbilt, Nashville, TN; Mark Sloan, Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA; R. Alejandro Sica, University of Illinois, Chicago, IL; Raymond Thertulien, 21st Century Oncology, Ashville, NC; Ligeng Tian, Virginia Oncology Associates, Newport, VA; Chaitra Ujjani, Georgetown, Washington, DC; and Pankit Vachhani, Roswell Park, Buffalo, NY.

Authorship

Contribution: A.I.L. conceived and designed the study; A.I.L., N.W., K.K., J.M., M.H., and R.R. helped to recruit study participants; N.W. conducted interviews with graduating hematology/oncology fellows; N.W., A.I.L., and N.A.P. led focus group discussions; A.I.L. and N.W. performed content analysis for the focus groups; A.I.L., E.A.L., and D.S. wrote the manuscript; A.I.L. and D.S. created the figures and visual abstract; and all authors reviewed the analysis and final manuscript..

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Deva Sharma, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, 777 Preston Research Building, 2220 Pierce Ave, Nashville, TN 37232-6307; e-mail: devaji@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Wallace PJ, Connell NT, Abkowitz JL. The role of hematologists in a changing United States health care system. Blood. 2015;125(16):2467-2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Majhail NS, Mau LW, Chitphakdithai P, et al. National survey of hematopoietic cell transplantation center personnel, infrastructure, and models of care delivery. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(7):1308-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhawale T. Post-fellowship career decision-making in a changing hematology practice landscape. Hematologist. 2015;12(3):3998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, Bruinooge S, Goldstein M. Future supply and demand for oncologists: challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3(2):79-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang W, Williams JH, Hogan PF, et al. Projected supply of and demand for oncologists and radiation oncologists through 2025: an aging, better-insured population will result in shortage. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(1):39-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoots WK, Abkowitz JL, Coller BS, DiMichele DM. Planning for the future workforce in hematology research. Blood. 2015;125(18):2745-2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soffer E, Hoots WK. Challenges facing the benign hematology physician-scientist workforce: identifying issues of recruitment and retention. Blood Adv. 2018;2(3):308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gajewski JL, LeMaistre CF, Silver SM, et al. Impending challenges in the hematopoietic stem cell transplantation physician workforce. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(12):1493-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkwood MK, Kosty MP, Bajorin DF, Bruinooge SS, Goldstein MA. Tracking the workforce: the American Society of Clinical Oncology workforce information system. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(1):3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Todd RF III, Gitlin SD, Burns LJ; Committee On Training Programs . Subspeciality training in hematology and oncology, 2003: results of a survey of training program directors conducted by the American Society of Hematology. Blood. 2004;103(12):4383-4388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Society of Hematology . American Society of Hematology survey of practice-based hematologists (unpublished).

- 12.American Board of Pediatrics . Pediatric Physicians Workforce Data Book, 2015-2016. Chapel Hill, NC: American Board of Pediatrics; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Althouse LA, Stockman JA III. Pediatric workforce: a look at pediatric hematology-oncology data from the American Board of Pediatrics. J Pediatr. 2006;148(4):436-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hord J, Shah M, Badawy SM, et al. ; American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Workforce Advisory Taskforce . The American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology workforce assessment: part 1-current state of the workforce. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(2): [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horn L, Koehler E, Gilbert J, Johnson DH. Factors associated with the career choices of hematology and medical oncology fellows trained at academic institutions in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(29):3932-3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall AL, Jenkins S, Mikhael J, Gitlin SD. Determinants of hematology-oncology trainees’ postfellowship career pathways with a focus on nonmalignant hematology. Blood Adv. 2018;2(4):361-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long T, Chaiyachati K, Bosu O, et al. Why aren’t more primary care residents going into primary care? A qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(12):1452-1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beattie S, Crampton PES, Schwarzlose C, Kumar N, Cornwall PL. Junior doctor psychiatry placements in hospital and community settings: a phenomenological study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e017584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed.. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) . ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Hematology and Medical Oncology (Subspecialty of Internal Medicine). ACGME-Approved Focused Revision: June 9, 2019. Chicago, IL: ACGME; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wailoo K. Drawing Blood: Technology and Disease Identity in Twentieth-Century America. The Henry E. Sigerist Series in the History of Medicine. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naik RP, Marrone K, Merrill S, Donehower R, Brodsky R. Single-board hematology fellowship track: a 10-year institutional experience. Blood. 2018;131(4):462-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Board of Internal Medicine . Number of Candidates Certified Annually by the American Board of Internal Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: American Board of Internal Medicine; 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.