Abstract

Previous research indicates that changes in housing wealth affect consumer spending on cars. We find that home equity extraction plays only a small role in this relationship. Consumers rarely use funds from equity extraction to purchase a car directly, even during the mid-2000s housing boom; this finding holds across three nationally representative household surveys. We find in credit bureau data that equity extraction does lead to a statistically significant increase in auto loan originations, consistent with equity extraction easing borrowing constraints in the auto loan market. This channel, though, accounts for only a tiny share of overall car purchases.

Keywords: Auto loans, auto sales, cash-out refinancing, home equity, home equity lines of credit, mortgage refinancing, motor vehicles

1. INTRODUCTION

House prices in the U.S. rose dramatically from 1998 to 2006 and then plunged thereafter, bottoming out in 2011. Several studies, which we review below, have connected the changes in housing wealth during this period to the patterns in consumer spending on other goods, in particular automobiles. Less is known, however, about how households deploy their home equity gains in order to purchase autos.

Narratives in the popular press suggest that it is quite common for households to use the proceeds from home equity extraction to fund auto purchases and that this practice was especially popular during the housing boom in the mid-2000s (e.g., Dash 2008, Harney 2015, Singletary 2007). The economics behind these narratives can seem a bit puzzling, however, as it is usually more cost effective for households to finance car purchases with auto loans than with home equity loans, even during housing booms. To better understand these narratives and assess how important home equity extraction actually is to funding auto purchases, in this paper we assess the two ways in which homeowners might use home equity to purchase cars. First, homeowners might use equity extraction proceeds directly to purchase cars outright. Second, households might use equity extraction proceeds indirectly to facilitate purchasing a car with an auto loan. In particular, credit-constrained households might use home equity proceeds to alleviate down payment constraints in the auto loan market or to pay down high-interest debt and thereby free up space in their budgets to take out an auto loan.

We find evidence that both pathways play some role in the relationship between house prices and car purchases, but neither pathway appears to have been a quantitatively important part of car purchases during the mid-2000s housing boom. We first show that very few households report purchasing cars primarily with funds from home equity lines of credit or the proceeds of cash-out refinancing, even during the housing boom years. This result is consistent across three nationally representative household surveys. We then use credit bureau data to explore whether home equity extraction indirectly supports car purchases by facilitating auto loans, and we find relatively strong evidence that this is the case. We explore the data a bit further and find that this relationship more likely reflects the role of equity extraction in easing down payment requirements in the auto loan market than an interaction between equity extraction and high-interest debt. But our estimates imply that the quantitative impact of home equity extraction on car purchases through the indirect auto loan channel is also quite small.

We use an event study setup in the analysis of the credit bureau data and identify the effects of home equity extraction on auto loan originations by looking for a discontinuous increase in auto loan originations shortly after equity extraction. The setup allows us to distinguish the role of equity extraction in easing auto loan credit constraints from other factors that might cause equity extraction and auto lending to move together, such as house prices and interest rates, and to assert that the relationship that we find between equity extraction and auto lending is likely causal.

Our results provide mixed support for studies in the existing literature that find that housing wealth primarily supported consumption during the 2000s by increasing the ability of households to borrow. Some patterns in the credit bureau data are consistent with this narrative, such as the stronger relationship we find between home equity extraction and subsequent auto loan origination for borrowers with low- to moderate credit scores than for other borrowers. However, individuals in the household surveys who report using home equity as the primary source of funds for purchasing a car do not appear to be particularly borrowing constrained. Because so few car purchases are funded through home equity, though, we hesitate to generalize too broadly about the implications of our findings for housing wealth and consumption.

Our results cast some doubt on the narrative that home equity extraction was an important source of funds for auto purchases during the housing boom in the mid-2000’s, but they do not imply that housing wealth was inconsequential for these purchases. The wealth effects of the changes in house prices could have been large, and some of the indirect effects of home equity extraction on auto purchases that we cannot explore in the data could also have been important. In the conclusion we discuss whether households may purchase other goods and services with home equity and free up space in a household balance sheet to buy a car.

2. RELATED LITERATURE

Our paper contributes to two literatures: (1) Studies of the relationship between house prices and consumption, and (2) studies of credit constraints in the auto loan market. Turning first to house prices and consumption, one key question in this vast literature is whether increases in house prices spur consumption primarily because households are wealthier (the wealth channel) or because lenders are willing to extend more credit to households after their house values rise (the borrowing constraints channel).1 The studies that have examined this relationship using data from the 2000s generally conclude that borrowing constraints are the more important of the two channels (e.g., Aladangady 2017, Bhuttta and Keys 2016, Cooper 2013, and Cloyne et al. 2017).

Consistent with this general finding, several studies also indicate that borrowing constraints in the mortgage market are an important part of the link between house prices and auto sales. Mian, Rao, and Sufi (2013) and Mian and Sufi (2014) find that the relationship between the changes in house prices and auto sales is strongest in zip codes where the share of the residents with high debt burdens or low incomes is high. Brown, Stein, and Zafar (2015) show that increases in house prices in the 2002 to 2006 period were associated with increases in borrowing on home equity lines of credit and auto loans; the response of auto debt to the changes in house prices was strongest for subprime borrowers. Gabriel, Iacoviello, and Lutz (2017) show that auto sales increased more between 2008 and 2010 in counties where California’s foreclosure prevention programs were especially successful in stabilizing house prices after the 2007–09 recession; they attribute this result to the rise in housing wealth, which eased credit constraints.

Other studies find that auto loan originations increase when changes in mortgage finance conditions allow more households to tap their home equity. Beraja et al. (2017) find that the drop in mortgage rates that ensued after the start of the Federal Reserve’s large-scale asset purchase program resulted in the largest increase in auto purchases in MSAs with highest median home equity. They also find that auto loan originations increased more for individuals that had a cash-out refinancing than a non-cash-out refinancing. Laufer and Paciorek (2016) find that looser credit standards on mortgage refinancing are associated with an increase in auto loan originations among subprime mortgage borrowers.

Our contribution to this literature is to ask whether households who experience large house price gains subsequently use home equity extraction to fund car purchases. Other than the Beraja et al. (2017) study, this particular question has not been investigated very thoroughly in the extant literature. We also consider whether the households who appear to purchase cars with home equity have characteristics that suggest borrowing constraints were a key factor in their choice of payment method.

Turning to the literature on credit constraints, several studies have documented that borrowing constraints are an important feature of the auto loan market, including Attanasio, Goldberg, and Kyriazidou (2008) and Adams, Einav, and Levin (2009); the latter study shows that minimum down payments matter a great deal to borrowers in the subprime auto loan market. Consistent with this result, Cooper (2010) finds in some waves of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics a positive relationship between home equity extraction and automobile costs, which include down payments on loans and leases.

A piece of empirical evidence that is commonly used to support the importance of borrowing constraints is the high contemporaneous sensitivity of auto purchases to predictable changes in income. Some studies demonstrate this sensitivity by using changes in mortgage market conditions, which affect the income that is available for non-housing purchases. For example, Agarwal et al. (2017) and DiMaggio et al. (2017) find an increase in auto loan originations after a drop in household mortgage payments due to the Home Affordable Modification Program and mortgage rate resets, respectively. DiMaggio et al. (2017) find a stronger response for homeowners with lower incomes and higher loan-to-value ratios. Other examples of predicable changes in income that appear to affect car sales contemporaneously include tax refunds (Adams, Einav, and Levin 2009, Souleles 1999); economic stimulus payments (Parker et al. 2013); an increase in the minimum wage (Aaronson, Agarwal, and French 2012); an increase in Social Security benefits (Wilcox 1989); and expansions of health insurance (Leininger, Levy, and Schanzenbach 2010). We add to this literature by documenting that car purchases are responsive to increases in available liquidity in the form of equity extraction. We believe that we are also the first authors to explicitly link an easing of borrowing constraints in the mortgage market to an easing of borrowing constraints in the auto loan market.

3. HOME EQUITY EXTRACTION AS A SOURCE OF FUNDS FOR CAR PURCHASES

We begin by measuring the share of auto purchases that are funded directly by home equity. Using household surveys, we define a car purchase as funded directly with home equity if a respondent indicates that she bought a new or used car and that home equity was a source of funding. Our analysis is based on three surveys: The Reuters/University of Michigan Survey of Consumers (Michigan Survey), the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), and the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE). As described in Appendix A, the three surveys ask about home equity extraction and auto purchases in different ways but nonetheless show a similar relationship between these two events.

As shown in Table 1, households rarely report using home equity to purchase cars. Results from the three surveys suggest that home equity extraction funds about 1 to 2 percent of both new and used car purchases. When we run these tabulations on the SCF and CE using only data for homeowners, as renters cannot have home equity, the shares of car purchases funded with home equity are only about ½ percentage point higher.2 The surveys show that households typically fund new car purchases with auto loans, which finance around 70 percent of new car purchases and a somewhat smaller share of used car purchases—around 40 to 50 percent. Cash or some other source of funds are used to finance the remaining 25 percent or so of new car purchases and 50 to 60 percent of used car purchases.3

Table 1.

Percent of Cars Purchased with Each Source of Funds

| New cars |

Used cars |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Funded with: | Michigan Survey | SCF | CE | Michigan Survey | SCF | CE |

| Home equity | 1 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 0.6 |

| Auto loan | 72 | 69 | 75 | 53 | 40 | 44 |

| Cash/other | 27 | 28 | 24 | 44 | 58 | 56 |

| Memo: | ||||||

| N | 830 | 1,864 | 14,385 | 1,062 | 2,118 | 36,718 |

Notes: Table excludes leases. Estimates from the Michigan Survey are based on data from 2003 to 2014. Estimates from the SCF are based on data from 2004, 2007, 2010, and 2013. Estimates from the CE are based on data from 1997 to 2012. Figures in the table are calculated with sample weights provided by each survey.

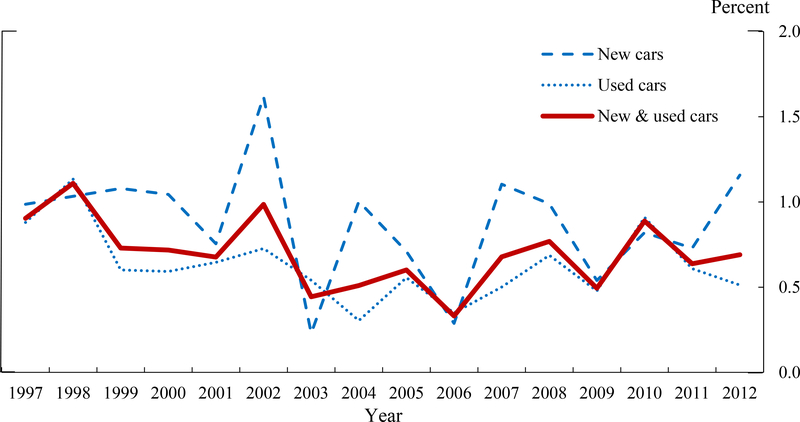

Although home equity appears to directly fund only a very small share of car purchases, its use might have picked up during the housing boom and then dropped off during the financial crisis. To assess this possibility, we calculated from the CE the share of car purchases funded by a home equity loan for each year between 1997 and 2012 (Figure 1). The share of cars purchased with home equity was low over the entire period; it averaged 0.7 percent both during the housing boom (1997 to 2006) and after it (2007 to 2012).4

Figure 1: Share of Cars Purchased with a Home Equity Loan.

Note: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Consumer Expenditure Survey. Figure shows the percent of car purchases for which the respondent cites a home equity loan as a source of financing. Shares are calculated with sample weights.

There are a few reasons why it may not be surprising that the share of car buyers that report home equity as the funding source, even during the housing boom, is so low. First, personal finance professionals would generally advise against using a home equity loan to purchase a car, as these loans extend maturities beyond the lengths typically recommended for cars and thus may increase the total interest paid by consumers (Singletary, 2008; The Wall Street Journal). Second, the transaction costs of extracting home equity with a second lien or mortgage refinancing generally exceed those of originating an auto loan; doing so only makes sense if the homeowner plans to extract a lot of equity at once and use much of it for another purpose. Third, the primary advantage to using home equity rather than an auto loan to finance a car purchase—the tax deductibility of the interest for loans up to $100,000—is most likely not relevant for the approximately one-third of homeowners who end up taking the standard deduction (Poterba and Sinai 2008).5 Finally, auto loans were an attractive financing choice during much of the housing boom period: Auto credit appears to have been widely available, and interest rates on new car loans were generally low and often heavily discounted by the manufacturers, especially for households with low credit risk.

So who uses home equity to buy cars? To answer this question and explore whether borrowing constraints are a factor, we compare the income, wealth, and credit history characteristics of households who purchase cars with home equity with those who purchase cars with auto loans or with cash or other means. We use data from the SCF for this exercise, and we limit the sample to homeowners who purchase new cars to eliminate the differences between homeowners and renters, and between new car purchasers and used car purchasers.

The comparisons, which are shown in Table 2, suggest that homeowners who report using home equity to buy a car do not appear to be lacking in terms of income, wealth, or access to credit. Among new car buyers, the table shows a clear ordering by method of funding an auto purchase: Households who use cash have the most wealth and access to credit, followed by households who use home equity and then households who use auto loans. Most of the differences among the three groups are statistically significant even with the very small sample of households who use home equity.

Table 2:

Summary Statistics for Homeowners who Buy New Cars

| Summary statistic: | Method of funding new car purchase |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cash/other | Home equity | Auto loans | |

| Median liquid assets (2013 dollars) | 42,134* | 21,909 | 10,500** |

| Median net worth (2013 dollars) | 1,057,283** | 598,906 | 291,000** |

| Median family income (2013 dollars) | 129,204 | 114,026 | 99,909 |

| Turned down for credit in past five years (Percent) | 7 | 15 | 20 |

| Did not apply b/c worried turned down for credit (Percent) | 2 | 2 | 10** |

| Avg. age of household head (Years) | 60** | 50 | 48 |

| College graduate (Percent) | 54 | 43 | 43 |

| Own stock directly (Percent) | 48 | 39 | 24 |

| Memo: | |||

| N | 992 | 29 | 686 |

Notes: Authors’ calculations from Survey of Consumer Finances data (2004, 2007, 2010, and 2013). Figures are calculated with sample weights. Figures in 2013 dollars are calculated with the Consumer Price Index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Asterisks denote the statistical significance of the summary statistics in each column from the estimates for those who purchase a car with home equity

denotes the 5 percent level and

is the 1 percent level.

Statistical significance is based on standard errors bootstrapped with 999 replicates drawn in accordance with the SCF sample design and adjusted for imputation uncertainty.

Beginning with wealth, the median of liquid assets is $42,000 for homeowners who purchase new cars with cash, $22,000 for those who use home equity, and $10,500 for those who use an auto loan.6 Likewise, median net worth is a bit greater than $1,000,000 for cash purchasers, nearly $600,000 for home equity purchasers, and nearly $300,000 for auto loan purchasers. The ordering of median income among the groups is the same as for wealth, but the differences are not statistically significant.

Turning to access to credit, the share of homeowners who purchase new cars and answered “yes” to the survey question “Was there any time in the past five years that you thought of applying for credit at a particular place, but changed your mind because you thought you might be turned down?” is low—only 2 percent for cash and home equity purchasers and 10 percent for auto loan purchasers. The share who answered “yes” to the survey question “In the past five years, has a particular lender or creditor turned down any request you made for credit?” is somewhat higher at 7 percent for cash purchasers, 15 percent for home equity purchasers, and 20 percent for auto loan purchasers. But the differences among the groups are not statistically significant for this measure. By both measures, homeowners who purchase new cars with home equity do not appear to be credit constrained.

Demographic characteristics that are correlated with credit access—age, education, and stockownership—similarly suggest that households who purchase new cars with home equity do not stand out as being credit constrained. Home equity purchasers are around 50 years old, on average, somewhat younger than cash purchasers (60 years old) and about the same age as auto loan purchasers. The share of home equity purchasers with a college education is about 43 percent, below the share of cash purchasers (54 percent) and about the same share as auto loan purchasers. The share of home equity purchasers that own stock is 39 percent, below the share of cash purchasers (48 percent) and above the share of auto loan purchasers (24 percent).

4. HOME EQUITY EXTRACTION AS A FACILITATOR OF AUTO LOANS

Although few households report directly using home equity to purchase a car, a larger number of households might indirectly use home equity to purchase a car by using the proceeds of a recent equity extraction to overcome down payment requirements or other credit constraints in the auto loan market. In this section, we use an event study set up to examine this indirect channel and estimate whether homeowners are more likely to take out an auto loan right after extracting home equity.7

As described in the literature review, a common way to detect the presence of borrowing constraints is to test whether auto purchases rise after a household receives a predictable boost in income. Using a similar logic, we use an event study setup to estimate the effect of home equity extraction on auto loan originations via the route of alleviating borrowing constraints in the auto loan market. Specifically, we measure the additional increase in the probability of originating an auto loan after home equity is extracted relative to the probability observed before equity is extracted.

The identification strategy of the event study setup assumes that the effects of common shocks to home equity extraction and auto loan originations—such as a wealth effect associated with a rise in house prices or a price effect associated with a change in interest rates—are equally relevant for auto loan originations before and after home equity is extracted. In contrast, when equity extraction facilitates an auto loan origination because it eases a constraint in the auto lending market, the auto loan origination must follow the extraction.

Our analysis uses credit bureau data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel (CCP).8 The panel is a randomly selected anonymized 5 percent sample of credit records from the credit bureau Equifax. The data include individuals’ credit scores, debt balances, payment histories, age, and geographic location (down to the Census block level). Individuals are followed over time with quarterly snapshots of their data, although the sample is periodically refreshed so that it remains representative of all individuals with a credit record and a social security number. We use data from 1999 to 2015, and for computational ease we select a 20 percent subsample; all told, our dataset is a 1 percent sample of the universe of credit records. An observation i in our sample is the data for a given individual in a given quarter.

We construct a sample of individuals who could plausibly have extracted equity at any time in an event window that spans three quarters before and three quarters after the quarter in which we observe the individual. Those individuals are borrowers who have mortgage debt and are current on that debt throughout the event window. For each event window we drop from the sample households who appear to have purchased a new residence (as determined by a change in the census block of residence from quarter-to-quarter) or who appeared to have been property investors (as determined by the presence of more than one first lien mortgage or home equity line of credit on the credit bureau file).9 The resulting dataset has approximately 31.7 million person-quarter observations.

Auto loan originations and home equity extractions are not directly reported in the CCP data, and so we infer these extensions of new credit from the number of open accounts for each borrower and their loan balances. For auto loans, we infer that a new loan was originated when the number of open auto loan accounts for a borrower increases from one quarter to the next or when the borrower’s total indebtedness on non-delinquent auto loans rises.10 As with mortgages, we do not count a balance increase on delinquent accounts as a loan origination because it may reflect overdue interest or fees being rolled into the loan balance.

To infer that a home equity extraction took place, we search our dataset for borrowers with mortgage debt in two consecutive quarters and with an increase in total mortgage debt of at least 5 percent (and at least $1,000) from the first to the second quarter. Because our dataset includes no borrowers who purchase new residences, appear to be property investors, or have a delinquent mortgage, none of the increases in mortgage balances in our dataset are associated with these activities. In addition, we flag apparent changes in the loan servicer, which can result in the reported balance on the loan dropping to zero for a quarter until the new servicer begins reporting to the credit bureau. In these cases, we replace the zero balance with the average of the balances from the prior and subsequent quarters and therefore do not record these servicing transfers as equity extractions.11 Data limitations preclude us from following a similar procedure for servicing transfers associated with auto loans.12

The reason we drop borrowers who purchase residences, are property investors, or are delinquent on their mortgages from our dataset—despite the fact that borrowers in these situations may extract home equity—is that retaining these borrowers would bias our estimates downward. The source of the bias is the uncertainty present in these situations about whether increases in mortgage balances imply that home equity was extracted. Therefore, keeping borrowers with these situations in our sample and assuming that all increases in mortgage balances are not equity extractions would bias downward the relationship we estimate between equity extraction and auto loan origination. We judge the simplest solution to be to drop these households entirely.

As a baseline, we use our final dataset to estimate equation (1) and determine the likelihood that an individual takes out an auto loan, conditional on whether she has extracted home equity recently or will do so in the near future. The dependent variable Autoi equals 1 if she originated an auto loan in the quarter associated with observation i and 0 otherwise. The independent variables include an intercept and a sequence of 7 indicator variables that correspond to the three quarters before the reference quarter associated with observation i (q = −3, −2, or −1), the reference quarter itself (q = 0), and the three quarters after the reference quarter (q = 1, 2, or 3). Each indicator variable equals 1 if the individual extracted home equity in that quarter and zero otherwise.

| (1) |

We estimate equation (1) as a linear probability model and report the coefficient estimates in the first column of Table 3. As indicated by the estimate of the intercept, about 3.6 percent of individuals who did not extract home equity at any point in the relevant seven quarter window originated an auto loan in the reference quarter. The estimates of the βq coefficients, when q < 0, measure the additional probability that an individual takes out an auto loan in the reference quarter if they extracted home equity q quarters ago; when q > 0, these estimates measure the additional probability that an individual takes out an auto loan in the reference quarter if they will extract home equity q quarters in the future. Individuals are about 1.1 percentage points more likely to take out an auto loan if they extracted home equity three or two quarters ago (β−3 and β−2). Individuals are 1.4 and 1.8 percentage points more likely to originate an auto loan if they extracted equity one quarter earlier or in the same quarter (β−1 and β0). Individuals are about 1.1 percentage points more likely to originate an auto loan if they will extract home equity either 1, 2, or 3 quarters in the future (β1, β2, and β3); estimates of these coefficients are essentially identical to those for β−3 and β−2.

Table 3:

Coefficient Estimates for Equations (1) through (4) and (6) Dependent variable: Indicator for originating an auto loan in the reference quarter

| Coefficients / standard errors for specifications |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| Constant | .036** | .037** | .049** | .048** | .049** |

| (.00003) | (.00003) | (.00021) | (.00020) | (.00021) | |

| Extracted before the reference quarter | |||||

| β-3 (q = −3) | .011** | .004** | .003** | .003** | .003** |

| (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | |

| β-2 (q = −2) | .011** | .004** | .002** | .002** | .002** |

| (.0003) | (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | |

| β-1 (q = −1) | .014** | .006** | .005** | .005** | .004** |

| (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | |

| Extracted during the reference quarter | |||||

| β0 (q = 0) | .018** | .010** | .009** | .009** | .009** |

| (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | |

| Extracted after the reference quarter | |||||

| β1 (q = 1) | .011** | .004** | .002** | .002** | .002** |

| (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | |

| β2 (q = 2) | .011** | .004** | .002** | .002** | .002** |

| (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | |

| β3 (q = 3) | .011** | .004** | .002** | .002** | .002** |

| (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | (.0004) | |

| Annual change in house prices in borrower’s zip code | .00007** | ||||

| (.000006) | |||||

| Uncollateralized debt paydown during the reference quarter | .005** | ||||

| (.0002) | |||||

| Uncollateralized debt paydown & extract during the reference | −.000003 | ||||

| quarter | (.0014) | ||||

| Other control variables: | |||||

| Borrower fixed effects? | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year fixed effects? | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Memo: | |||||

| R2 | .0005 | .07 | .07 | .07 | .07 |

| N | 31,700,439 | 31,700,439 | 31,700,439 | 22,982,245 | 31,700,439 |

Notes: Authors’ calculations from merged FRBNY CCP and CoreLogic data. Each column in the table shows the estimated coefficients from an ordinary least squares regression. Robust standard errors are displayed in parentheses underneath each coefficient. The dependent variable in each regression is an indicator variable for whether the individual originated an auto loan in the quarter of the observation. The regressions with individual fixed effects include 1,219,680 such intercepts. Two asterisks (**) denote that coefficient estimates are statistically significantly different from zero at the 1 percent level.

Estimates of all seven β coefficients are positive and statistically different from zero, indicating that individuals who have extracted home equity recently or will do so in the near future are more likely to take out an auto loan than are other individuals. This relationship may reflect factors such as rising housing wealth or low interest rates overall, which boost the likelihood of both equity extraction and auto loan origination, or characteristics of the borrowers that affect the likelihood of both activities.13

In addition, the β coefficients that correspond to subsets of the sample that extracted home equity during the reference quarter or one quarter before it are larger than the other β coefficients, consistent with equity extraction easing credit constraints in the auto loan market. As described earlier, our identification stems from the timing of events: if borrowers use the proceeds of home equity extraction to overcome credit constraints in the auto loan market, they cannot originate the auto loan before receiving home equity proceeds. Assuming that other factors that affect auto loan originations do not change systematically around the point of extraction, we interpret the incremental rise in the probability of originating an auto loan after the equity extraction as the causal effect of extraction on auto loan origination. In equation (1), the β−1 coefficient estimate is 0.3 percentage point higher than that for the other βs, and the estimate of β0 is 0.7 percentage point higher, yielding a total effect of 1.0 percentage point. The difference between the β0 and β−1 estimates is statistically significant, and the implied total effect is large relative to the 4 percent unconditional probability in this sample of originating an auto loan in a typical quarter.14 The magnitude of the effect that we measure is also similar to the increase in the probability of taking out an auto loan after equity extraction measured in Beraja et al. (2017).15

One possible concern with using this event study setup with these data is that quarterly observations may be too coarse to assert that home equity extractions predated the auto loan originations when both occurred in the same quarter. The results in Beraja et al. (2017) assuage this concern. In their credit bureau data—which unlike ours are measured at a monthly frequency—auto loan originations begin to rise in the month after equity extraction, with the peak occurring two months after the extraction.

Next, we add person fixed effects to the probability model to control for each individual’s innate probability of taking out an auto loan. Other than the intercept that now varies across individuals, this model, shown in equation (2), is the same as equation (1).

| (2) |

The coefficient estimates from this specification are shown in the second column of Table 3. The estimates of β−3, β−2, β1, β2, and β3 are around 0.4 percentage point, β−1 is 0.6 percentage point, and β0 is 1.0 percentage point. These β coefficient estimates are all about 0.7 percentage point below the corresponding estimates in equation (1), a comparison that indicates that individual heterogeneity explains much of the correlation between auto loan origination and home equity extraction. However, even with the addition of the fixed effects, individuals are still 0.8 percentage point more likely to originate an auto loan in the reference quarter if they extract home equity in that quarter or the one before it, and this increase remains statistically significant. So the conclusion that equity extraction eases borrowing constraints in the auto loan market is robust to the inclusion of person fixed effects.

In equation (3) we add year fixed effects to the model in equation (2) to capture omitted factors that vary over time but not individuals; examples of these factors might include the level of interest rates or the national unemployment rate, which affect both equity extraction and auto loan originations. Coefficient estimates from this specification are in the third column of Table 3.

| (3) |

The estimates of the β−3, β−2, β1, β2, and β3 coefficients are even lower in this specification than in equation (2)—by around 0.2 percentage point. Although the coefficient estimates are still statistically significantly different from zero, for practical purposes home equity extraction affects the probability of originating an auto loan in this specification only if the extraction occurs in the reference quarter or the quarter before it. The probability of originating an auto loan in the reference quarter is 0.7 percentage point higher if equity is extracted in the same quarter than if it is extracted in the next quarter, and the probability is 0.3 percentage point higher if equity is extracted one quarter earlier.16

Finally, in equation (4)) we add the one year change in a house price index for the borrower’s Zip code, ΔHPIi, to the model in equation (3). Changes in local house prices can vary considerably across the country and therefore are only partly captured by the year fixed effects. The Zip code house price indexes are from CoreLogic, and we are able to match these indexes to borrowers for 72 percent of the borrowers in the sample.17 We include this specification to take into account the tendency of some households to make a number of home price appreciation-related financial decisions at one time. If paying attention is costly, for example, households might react to an increase in house prices by extracting equity and originating an auto loan in the same quarter. In this case, it is the fixed cost of paying attention rather than the presence of borrowing constraints that explains the pattern of the relevant beta coefficient estimates in equations (1) through (3). Coefficient estimates from this house price augmented specification are in the fourth column of Table 3.

| (4) |

The estimate of γ indicates that the association of regional house price changes with auto loan originations is statistically significant but very small; the 0.00007 coefficient estimate means that even a fairly large one year house price increase of 19 percent (the 95th percentile of one year house price increases in our sample) is associated with an increase in the probability of originating an auto loan of only 0.1 percentage point. In a more flexible nonlinear specification (not shown), we allow γ to vary across six increments of house price increases and similarly find that living in a Zip code with the largest increase—a 10 percent or greater increase from the previous year—is associated with only a 0.1 percentage point increase in the probability of originating an auto loan.

Importantly, the estimates of the sequence of β coefficients are essentially unchanged in this specification relative to equation (3). As before, the coefficient estimates imply that borrowers are 0.7 percentage point more likely to originate an auto loan in the reference quarter if they extract home equity in the same quarter and 0.3 percentage point more likely to do so if they extract equity one quarter earlier. Similarly, characterizing house prices with the nonlinear transformation described above has little effect on the β coefficient estimates, and the same is true if we use three year changes in the regional house price indexes in place of one year changes.

The various robustness checks support our conclusion that the rise in auto loan originations that occurs during and shortly after a home equity extraction stems from an easing of credit constraints.

5. ADDITIONAL EVIDENCE OF BORROWING CONSTRAINTS IN THE AUTO LOAN MARKET

If home equity extraction boosts the likelihood of taking out an auto loan because it eases credit constraints in the auto loan market, we would expect the relationship to be stronger for borrowers with lower credit scores. We look for this corroborating evidence by adding variables to the event study probability model that allow the intercept and coefficients on the equity extraction time indicators to vary for six credit score categories, indexed by c.18 As in equation (3), this specification includes person and year fixed effects.

| (5) |

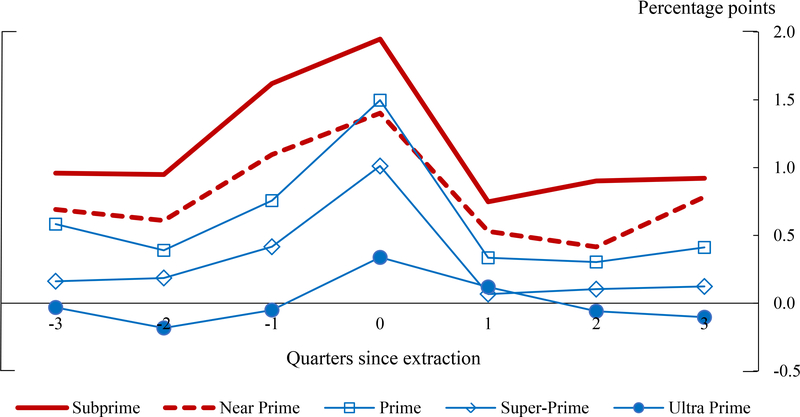

The βqc coefficient estimates are graphed in Figure 2.19 The probability of taking out an auto loan in the reference quarter is higher for borrowers in all of the credit score groups who extract home equity in the same quarter or one quarter earlier, but the magnitudes of the increases vary substantially. These probabilities are shown in the second column of Table 4. For comparison, the first column shows the probability that a borrower from each group originates an auto loan in the reference quarter if they extract home equity during the next quarter. As in the earlier exercises, this probability represents the rate at which borrowers take out an auto loan if they extract equity but do not face borrowing constraints. To gauge the contribution of the role of home equity in easing credit constraints for each group, column 3 shows the percent increase in the probability of originating an auto loan associated with having extracted equity before or during the reference quarter as opposed to after it.

Figure 2: Effect of Home Equity Extraction on the Probability of Originating an Auto Loan by Borrower Credit Risk Group and Quarter relative to Equity Extraction.

Note: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Equifax Consumer Credit Panel. Figure shows the βqc coefficient estimates from equation (4).

Table 4:

Probability of Auto Loan Origination by Credit Score Group and Timing of Home Equity Extraction

| Credit score group (risk score range) | Timing of home equity extraction |

Memo: Percent change in auto loan originations from extraction before or during vs. after the reference quarter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| After the reference quarter | Before or during the reference quarter | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Subprime (580–619) | .050 | .071 | 41% |

| Near prime (620–659) | .054 | .069 | 27% |

| Prime (660–699) | .057 | .073 | 28% |

| Super prime (700–759) | .057 | .070 | 23% |

| Ultra prime (760–850) | .058 | .058 | 1% |

Notes: Authors’ calculations from equation (5) estimated with FRBNY CCP data. The first column in the table shows estimates of α c + β1c for credit score groups 2 through 6. The second column shows estimates of α c + β1c + (β-1c − β1c)+ (β0c − β1c) for credit score groups 2 through 6. The estimates in the first and second columns also include the intercept generated by STATA’s areg procedure. The third column is the percent change of the second column from the first column. The credit score is the Equifax 3.0 risk score.

Individuals with subprime credit scores who extract home equity after the reference quarter have a 5.0 percent probability of originating an auto loan in the reference quarter. If these individuals instead extract equity during the reference quarter or the quarter before it, that probability is 7.1 percent, which represents a 42 percent increase in the probability of originating an auto loan. In contrast, individuals with the highest (ultra-prime) credit scores who extract home equity after the reference quarter have a 5.8 percent probability of originating an auto loan in the reference quarter, and that likelihood only edges up to 5.9 percent if the home equity extraction instead occurs during the same quarter or one quarter. In relative terms, borrowing constraints have barely any impact on the rate at which this group originates auto loans. For individuals with middle credit scores, extracting equity before or during the reference quarter increases the probability of originating auto loans between 22 and 27 percent. The larger effect observed for subprime individuals relative to other groups corroborates our conclusion that credit constraints underlie the relationship between equity extraction and auto loan originations identified by the event study.

Although our data do not reveal much about how home equity extraction eases credit constraints in the auto loan market, one theory we can test is whether borrowers who extract home equity appear to use the proceeds to pay down high-interest consumer debt. Bhutta and Keys (2016) show that credit card debt decreases only slightly after a home equity extraction, on average, but the decreases are larger and more persistent for individuals with lower credit scores. Such a maneuver could make a household a better credit prospect by reducing its credit utilization rate (which counts toward a borrower’s credit score) and its debt service relative to income (which might be a factor in auto loan underwriting).20 Independent of the lender’s determination, the borrower might feel a greater capacity to take out an auto loan after paying down higher-interest debt.

To look for evidence of consumer debt paydown, we construct an indicator variable CC_Payi that equals 1 if the individual pays down half or more of the existing uncollateralized consumer debt in the quarter associated with observation i, and it is set to 0 otherwise.21 We then assess whether individuals who took this action are more likely than other equity extractors to purchase cars. The exercise is shown as equation (6), which includes a term that interacts CC_Payi with an indicator of whether equity was extracted in the reference quarter.22 A positive and significant estimate of η would suggest that consumer debt paydown is part of the relationship between home equity extraction and auto loan originations.

| (6) |

The coefficient estimates for equation (6) (column 5, Table 3) show no detectable role for consumer debt paydown in the relationship between equity extraction and auto lending. The estimate of δ indicates the likelihood that an individual takes out an auto loan in the reference quarter rises 0.5 percentage point if she pays down uncollateralized debt in the same quarter, but the miniscule and insignificant estimate of η suggests this probability is essentially unaffected by whether she also extracts home equity in that quarter. More flexible specifications that interact leads and lags of credit card paydown with leads and lags of home equity extraction also find essentially no relationship between these factors.

This result is not surprising, as the existing literature suggests that the constraint most likely eased by equity extraction is down payment requirements. These studies identify down payments as a major credit constraint in the auto lending market (Adams, Einav, and Levin 2009) and find a relationship between equity extraction and increased spending on auto loan down payments (Cooper 2010).

6. HOW IMPORTANT IS HOME EQUITY EXTRACTION IN THE AUTO LOAN MARKET?

Having established that home equity extraction has a statistically significant effect on auto loan originations, we now ask whether equity extraction plays a quantitatively important role in aggregate auto loan originations. To begin, we first estimate in our data that around 3 million households extracted home equity each year in 2001 and 2002, and about 5 to 6 million households extracted equity annually in the peak housing boom years from 2003 to 2006.23 These estimates are consistent with the estimates of Canner, Dynan, and Passmore (2002) for the 2001 to 2002 period.24

To calculate the effect of these equity extractions on car purchases, we apply to the extraction volumes the coefficients from our preferred specification in equation (3), which imply that home equity extraction raises the probability of an auto loan origination by 0.9 percentage point. (This is the incremental probability of an auto loan origination in a given quarter associated with households who extract equity in the same quarter (β0 – β1 = 0.65) plus the incremental probability associated with those who extract equity in the preceding quarter (β−1 – β1 = 0.25)).25 Applying this 0.9 percentage point effect to 4.5 million equity extractions during the peak housing boom years suggests that home equity extraction facilitated about 40,000 auto loans per year during this period. By comparison, the number of auto loan originations in recent years has varied from a low of around 15 million in 2009 to a high of around 30 million in 2016.26 This comparison suggests that home equity extraction was likely not a quantitatively important factor in total auto loan originations or in the changes in loan originations during this period.

7. CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we demonstrate that home equity extraction does not appear to be the direct source of funding for many car purchases. Estimates from three nationally representative surveys indicate that very few households purchase cars directly with home equity. Further, the share of those who report doing so does not appear to vary with the housing cycle.

However, home equity extraction is associated with an increase in auto loan originations. Using an event study framework with credit bureau data, we show that home equity extraction increases the likelihood of originating an auto loan in a statistically significant and causal way. We also show that this increase is distinct from the effects of other factors that cause equity extractions and auto loan originations to move together, such as the changes in house prices and interest rates, and that the effect of home equity extraction on auto loan originations is more pronounced for borrowers with lower credit scores. Our results suggest that home equity extraction increases auto loan originations by easing down payment and other credit constraints in the auto loan market. In contrast, we find no evidence that equity extraction increases auto loan originations by allowing households to pay down high-interest debt and thereby free up space in their budgets for auto loan payments. Nonetheless, when we put the effects we estimate into the context of the U.S. auto loan market, the number of additional auto loan originations in recent years that we can attribute to home equity extraction is very small.

Our results cast doubt on the narrative that home equity extraction was an important source of funds for auto purchases during the housing boom in the mid-2000’s, but they do not imply that housing wealth was inconsequential for these purchases. At least two other (not mutually exclusive) channels contribute to the relationship between auto purchases and home equity. First, households are wealthier when their homes increase in value, and their demand for cars should also increase. Rising housing wealth may have boosted car purchases considerably, even if these households did not report purchasing cars directly with home equity; different types of wealth are, to some extent, interchangeable. For example, paying for other goods and services with home equity may free up balance sheet space to purchase a car with cash or an auto loan.

Second, home equity might indirectly facilitate auto loans if lenders are more willing to extend credit to households in neighborhoods with rising house prices. Home equity is typically not considered directly in the underwriting of auto loans, but lenders may take into account local economic conditions, which can be correlated with house prices. Alternatively, lenders may have an easier time raising capital in areas of the country that are booming. Households in these markets may also be more likely to retain their good credit standing when their income is disrupted, because they can more easily refinance their mortgages or sell their homes. Ramcharan and Crowe (2013) show that peer-to-peer lenders were less willing to extend unsecured credit to homeowners in areas with declining house prices; a similar dynamic may occur in the auto credit market, although we are not aware of any research on this topic.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kyle Coombs and Jimmy Kelliher for extraordinary research assistance and to Ben Keys and many Federal Reserve colleagues for helpful comments. The views in this paper are the authors’ alone and do not necessarily represent the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or its staff, or the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health. Brett McCully was supported by a fellowship from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (T32HD007545) for part of the duration of this project.

APPENDIX A: SURVEY DATA

A.1. The University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers (Michigan survey)

The Michigan survey data come from a special module that the Federal Reserve has sponsored three times per year since 2003. Survey respondents are asked if they purchased a car in the previous six months, and if so, whether they borrowed money to purchase the car or paid cash. If the answer is “cash,” respondents are asked whether the source of the cash was savings or investments, a home equity loan, a mortgage refinancing, or “somewhere else.”27 Respondents can cite multiple sources of the cash, although this is rare. We define the car purchase as a home equity extraction if the respondent identifies a home equity loan or mortgage refinancing as the source of the cash. We define the purchase as an auto loan if the respondent indicates that a car was purchased with borrowed money. We define all other purchases as cash/other. The data span the 2003 to 2014 period and include 2,388 purchases of new and used cars.

A.2. Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE)

In the CE, households are asked about the vehicles that they currently own. We focus on cars purchased in the survey year. For each car owned, households are asked whether any portion of the purchase price was financed.28 If so, they are asked whether the source of credit was a home equity loan. Households are not asked if the car was purchased with the proceeds from a cash-out refinancing, and so we will miss these purchases.

We define the purchase as a home equity extraction if the respondent identifies a home equity loan as a source of credit. We define the purchase as an auto loan if the respondent financed the purchase but does not indicate they used a home equity loan. We define all other purchases as cash/other. The data cover the 1997 to 2012 period and include 28,290 car purchases.

A.3. Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF)

In the SCF, like in the CE, households are asked about the cars that they own at the date of the interview. We focus on cars that were likely purchased recently. For used cars, the date of purchase is known from a survey question, and we select cars purchased during the survey year. For new cars, we must deduce the date of purchase, because the survey asks only about the model year of the car. We define a new car as recently purchased if its model year corresponds to the survey year or the subsequent year. Most new car purchases covered by this definition will have occurred during the survey year, although some of these purchases will have occurred during the previous calendar year. The reason is that new models are introduced during the previous calendar year and are not fully phased out until the subsequent calendar year. For the same reason, our definition will miss the small volume of new cars still being sold from earlier model years.29

The definitions described above yield a sample of car purchases from the SCF that have occurred mostly within a year of the interview. Taking advantage of this relatively short lookback window, we match households’ recent car purchases to the answers from separate questions asked about outstanding auto loan balances and recent activities with home mortgages. Unlike the CE, the SCF does not ask households whether their cars were purchased with home equity, and so we infer these purchases when an SCF respondent both appears to have purchased a car recently and reports having used the proceeds from a recently originated cash-out refinancing, second or third lien, or HELOC to buy a car.30 If a household does not appear to have used home equity but does report having an auto loan outstanding, we assume the car was purchased with an auto loan. All other purchases are defined as cash/other.

One potentially important consequence of using the definitions described above is that households who buy the newest models early in the model year are likely overrepresented in our SCF sample of new car purchases. And, as noted earlier, we also miss a few purchases of older car models. All told, these factors may bias upward some of the sample statistics on new car buyers, such as average income and wealth, because new car prices decline over the course of the model year (Aizcorbe, Bridgman, and Nalewaik, 2009) and can drop when newer models are introduced.31 These price dynamics suggest that households who buy new cars immediately upon the model release are likely more affluent than those who purchase later in the model year.

We use data from the 2004, 2007, 2010, and 2013 surveys, which include 3,929 purchases of new and used cars.

Footnotes

Berger, Guerrieri, Lorenzoni, and Vavra (forthcoming) provide a recent treatment of the channels between house prices and consumption.

In the CE: Home equity was used by 1.0 percent of homeowners who bought a new car and 1.3 percent who bought a used car. In the SCF: Home equity was used by 2.7 percent of homeowners who bought a new car and 2.5 percent who bought a used car.

The shares presented in Table 1, which are based on transaction counts, change only slightly if they are instead based on dollars spent. SCF tabulations indicate that the average purchase price was around $25,000 for cars funded with auto loans or home equity, and $29,000 for cars purchased with cash; the median values were even closer at $24,000 or $25,000 for all three funding methods.

The pattern does not appear to be substantively different for households identified in the CE as living in California, Arizona, Nevada, and Florida (states with particularly high rates of home price appreciation during the housing boom). The share of cars purchased with home equity in these states averaged 0.4 percent from 1997 to 2006 and 0.8 percent from 2007 to 2012. These tabulations are based on smaller samples than the overall shares.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 suspends the tax deductibility of this interest from 2018 to 2026. Under the provisions of the law, the interest on home equity loans is only tax deductible if the loan is collateralized by a loan “used to buy, build or substantially improve the taxpayer’s home that secures the loan.” See https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/interest-on-home-equity-loans-often-still-deductible-under-new-law for a summary of the changes.

Liquid assets are defined as checking, savings, and money market accounts, and call accounts at brokerages.

Other papers that have used similar event study approaches include Benmelech, Guren, and Melzer (2017) and Beraja et al. (2017).

See Lee and van der Klaauw (2010) for more information on the FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel.

Census blocks are the smallest unit of geography that the Census Bureau uses to tabulate decennial data. Generally blocks are quite small; in urban areas, for example, a census block often corresponds to a city block.

The auto loan field in credit bureau data includes auto leases as well as loans collateralized by both new and used vehicles. Our auto loan origination definition follows the definitions used in The Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, available at https://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/hhdc.html, and the code was generously provided by FRBNY staff. We build on their work by excluding balance increases associated with delinquent loans. The starting point for our home equity extraction code is Bhutta and Keys (2016), which is available on the American Economic Review web site at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20140040. We build upon these authors’ work by excluding balance increases associated with delinquent loans and by addressing servicing transfers. We thank all these authors for their generosity in providing their code.

Adjusting for servicing transfers reduces the number of equity extractions by approximately 11 percent in 1999–2001, and by 1 to 6 percent in 2002–2015.

At the time this paper was written, the CCP contained individual records for each loan (“tradelines”) for mortgages and HELOCs but not for auto loans.

Parker (2017), for example, links the propensity of households to increase spending in response to the arrival of predictable, lump sum payments to persistent household traits.

Specifically, an F-test rejects at the 1 percent level the hypotheses that β0 and β1 are equal.

See Figure 7 in Beraja, Fuster, Hurst, and Vavra (2017).

We also ran a specification with quarter-year fixed effects; the results were essentially the same as the year fixed effects specification.

This match rate is consistent with that found in Bhutta and Keys (2016). See p. 1749 of that paper for more discussion.

The credit scores on the CCP are Equifax 3.0 risk scores, which range from 280 to 850 and are roughly comparable to FICO credit scores. Our score ranges are as follows: Deep subprime, 280–579; subprime, 580–619; near prime, 620 to 659; prime, 660 to 699; super-prime, 700 to 759; and ultra-prime, 760 to 850. We thank Hank Korytkowski for help in determining these ranges. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (2012) provides a comparison of the different types of credit scores.

We omit borrowers with “deep subprime” credit scores from Figure 2 because the very few households in this category who own homes likely have credit scores too low to qualify for additional mortgage credit.

Replacing $10,000 in credit card debt with $10,000 in mortgage debt, for example, would net a household $250 in savings per month, assuming a thirty year fixed rate mortgage at a rate of 4 percent and a monthly minimum payment requirement of 3 percent on the credit card debt.

Uncollaterized consumer debt is defined as total balances on credit cards issued by banks and consumer finance companies and on retail cards as well as uncollateralized consumer installment loans.

Specifications that interact credit card paydown and home equity extraction with credit score category also find essentially no relationship between these factors. We also established that our results are robust to using an indicator variable for whether the individual paid down at least a fourth of their existing uncollateralized debt in the quarter associated with observation i.

Our sample is a 1 percent extract of all credit bureau records, so we multiply our sample estimates by 100 to scale them up to the national level. One complication is that about three-fourths of the home equity extractions that we observe in the credit bureau records are co-signed loans, in which case the loan observed for a borrower in the sample also belongs to another borrower that is most likely outside the sample. To account for this, we assign each co-signed loan a weight of 0.5 when we scale up the estimates.

Canner, Dynan, and Passmore (2002) find that 4.6 percent of a sample of 2,240 homeowners surveyed by the Michigan Survey of Consumers had engaged in a cash-out refinancing in 2001 or the first half of 2002. They note that multiplying that fraction by the total number of U.S. homeowners at that time leads to an estimated 4.9 million cash-out refinancings in 2001 and the first half of 2002 (an annual rate of around 3 million).

We rounded these estimates to 0.7 and 0.3, respectively, in the earlier discussion of the regression results.

See Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Origination Activity,” https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-credit-trends/auto-loans/origination-activity/, and Equifax, “Quarterly U.S. Consumer Credit Trends,” https://investor.equifax.com/~/media/Files/E/Equifax-IR/reports-and-presentations/events-and-presentation/consumer-credit-trends-report-q1–2017-revised-pdf.pdf.

According to the Michigan survey staff, some respondents who purchase autos with home equity appear to consider these purchases as funded with “borrowed” money rather than “cash.” If so, the survey instrument will miss some car purchases funded by home equity extraction. The survey staff catch many of these instances and recode the answers as cash/home equity. We do not think that this aspect of the question structure leads to a significant understatement of home equity funded purchases because the Michigan results are in line with the results from the other two surveys, which have different question structures.

The CE asks households a separate set of questions about the vehicles they purchased during the reference period. Our analysis is based on the set of questions about vehicles owned (in the EOVB files) because these data include questions about how the purchases were financed.

In the 2013 SCF, for example, our definition would include new cars from the 2013 or 2014 model years, about 75 to 80 percent of which likely occurred in 2013 and 20 to 25 percent in 2012. Our definition misses new cars from the 2012 or earlier model years that were purchased in 2013, a volume that is likely only about 3 percent of the new car sales in our sample. These estimates are based on monthly sales by model year from JD Power and Associates and are adjusted to reflect the fact that SCF interviews are conducted from April of the survey year to the following February. Dettling et al. (2015) document that auto sales in the SCF line up well with the NIPA aggregates once the timing and model year issues are taken into account.

We consider the origination of a cash-out refinancing or second lien to be recent if it occurred in the survey year or in the year prior. We include the prior year because, as described earlier, our sample of recent vehicle purchases likely includes some cars purchased in the previous year, and because there may be a lag between the cash-out refinance and the purchase of the car. We assume that a HELOC funded a recent car purchase if the proceeds of the most recent draw were used for a car. The SCF does not ask when that draw took place; depending on the timing, our definition could either understate or overstate the share of vehicle purchases funded with HELOCs.

The SCF and CE samples also miss vehicles purchased during the calendar year but sold (or scrapped) before the date of the survey. We assume, given our short lookback period, that this bias is small.

Contributor Information

Brett A. McCully, Email: bmcully@ucla.edu, UCLA Department of Economics.

Karen M. Pence, Email: Karen.Pence@frb.gov, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Daniel J. Vine, Email: Daniel.J.Vine@frb.gov, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

LITERATURE CITED

- Aaronson Daniel, Agarwal Sumit, and French Eric. (2012) “The Spending and Debt Response to Minimum Wage Hikes.” American Economic Review, 102(7), 3111–3139. [Google Scholar]

- Adams William, Einav Liran, and Levin Jonathan. (2009) “Liquidity Constraints and Imperfect Information in Subprime Lending.” American Economic Review, 99(1), 49–84. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal Sumit, Amromin Gene, Ben-David Zahi, Chomsisengphet Souphala, Piskorski Tomasz, and Seru Amit. (2017) “Policy Intervention in Debt Renegotiation: Evidence from the Home Affordable Modification Program.” Journal of Political Economy. 125(3), 654–712. [Google Scholar]

- Aizcorbe Ana, Bridgman Benjamin, and Nalewaik Jeremy. (2009) “Heterogeneous Car Buyers: A Stylized Fact.” Economics Letters, 109(1), 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Aladangady Aditya. (2017) “Housing Wealth and Consumption: Evidence from Geographically Linked Microdata.” American Economic Review, 107(11), 3415–3446. [Google Scholar]

- Attanasio Orazio, Goldberg Pinelopi, and Kyriazidou Ekaterini. (2008) “Credit Constraints in the Market for Consumer Durables: Evidence from Micro Data on Car Loans.” International Economic Review, 49(2), 401–436. [Google Scholar]

- Benmelech Efraim, Guren Adam, and Melzer Brian T.. (2017) “Making the House a Home: The Stimulative Effect of Home Purchases on Consumption and Investment.” NBER Working Paper No. 23570. [Google Scholar]

- Berger David, Guerrieri Veronica, Lorenzoni Guido, and Vavra Joseph. (Forthcoming) “House Prices and Consumer Spending.” Review of Economic Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Beraja Martin, Fuster Andreas, Hurst Erik, and Vavra Joseph. (2017) “Regional Heterogeneity and Monetary Policy.” NBER Working Paper No. 23270. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta Neil, and Keys Benjamin J.. (2016) “Interest Rates and Home Equity Extraction During the Housing Boom.” American Economic Review, 106(7), 1742–1774. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Meta, Stein Sarah, and Zafar Basit. (2015) “The Impact of Housing Markets on Consumer Debt: Credit Report Evidence from 1999 to 2012.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 47(S1), 175–213. [Google Scholar]

- Canner Glenn, Dynan Karen E., and Passmore Wayne. (2002) “Mortgage Refinancing in 2001 and Early 2002.” Federal Reserve Bulletin, 88, 469–481. [Google Scholar]

- Cloyne James, Huber Kilian, Ilzetzki Ethan, and Kleven Henrik. (2017) “The Effect of House Prices on Household Borrowing: A New Approach.” NBER Working Paper No. 23861. [Google Scholar]

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2012) “Analysis of Differences between Consumer- and Creditor-Purchased Credit Scores.” http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201209_Analysis_Differences_Consumer_Credit.pdf

- Cooper Daniel. (2010) “Did Easy Credit Lead to Overspending? Home Equity Borrowing and Household Behavior in the Early 2000s.” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Public Policy Discussion Paper No. 09–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Daniel. (2013) “House Price Fluctuations: The Role of Housing Wealth as Borrowing Collateral.” Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(4), 1183–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Dash Eric. (2008) “Auto Industry Feels the Pain of Tight Credit,” New York Times, May 27, 2008, A-1 [Google Scholar]

- Dettling Lisa J., Devlin-Foltz Sebastian J., Krimmel Jacob, Pack Sarah J., and Thompson Jeffrey P.. (2015) “Comparing Micro and Macro Sources for Household Accounts in the United States: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2015–086. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 10.17016/FEDS.2015.086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio Marco, Kermani Amir, Keys Benjamin J., Piskorski Tomasz, Ramcharan Rodney, Seru Amit, and Yao Vincent. (2017) “Interest Rate Pass-Through: Mortgage Rates, Household Consumption, and Voluntary Deleveraging.” American Economic Review, 107(11), 3550–3588. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel Stuart A., Iacoviello Matteo M., and Lutz Chandler. (2017) “A Crisis of Missed Opportunities? Foreclosure Costs and Mortgage Modification During the Great Recession.”

- Harney Kenneth. (2015) “Boom in Equity Allows Homeowners to Cash in and Even Cash Out.” The Washington Post, September 29, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Laufer Steven and Paciorek Andrew. (2016) “The Effects of Mortgage Credit Availability: Evidence from Minimum Credit Score Lending Rules” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2016–098. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 10.17016/FEDS.2016.098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Donghoon, and van der Klaauw Wilbert. (2010) “An Introduction to the FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports No. 479. [Google Scholar]

- Leininger Lindsay, Levy Helen, and Schanzenbach Diane. (2010) “Consequences of SCHIP Expansions for Household Well-Being.” Forum for Health Economics and Policy, 13(1), 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mian Atif, Rao Kamalesh, and Sufi Amir. (2013) “Household Balance Sheets, Consumption, and the Economic Slump.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(4), 1687–1726. [Google Scholar]

- Mian Atif and Sufi Amir. (2014) “House Price Gains and U.S. Household Spending from 2002 to 2006.” NBER Working Paper No. 20152. [Google Scholar]

- Parker Jonathan A. (2017) “Why Don’t Households Smooth Consumption? Evidence from a 25 Million Dollar Experiment.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 9(4), 153–183. [Google Scholar]

- Parker Jonathan A., Souleles Nicholas S., Johnson David S., and McClelland Robert. (2013) “Consumer Spending and the Economic Stimulus Payments of 2008.” American Economic Review, 103(6), 2530–2553. [Google Scholar]

- Poterba James, and Sinai Todd. (2008) “Tax Expenditures for Owner-Occupied Housing: Deductions for Property Taxes and Mortgage Interest and the Exclusion of Imputed Rental Income.” American Economic Review, 98(2), 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ramcharan Rodney, and Crowe Christopher. (2013) “The Impact of House Prices on Consumer Credit: Evidence from an Internet Bank.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 45(6), 1085–1115. [Google Scholar]

- Singletary Michelle. (2007) “Loan Loser: Home-Financing a Car.” The Washington Post, March 18, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Souleles Nicholas S. (1999) “The Response of Household Consumption to Income Tax Refunds.” American Economic Review, 89(4), 947–58. [Google Scholar]

- The Wall Street Journal. “How to Finance an Auto Purchase” in How-to Guide: Personal Finance available at http://guides.wsj.com/personal-finance/buying-a-car/how-to-finance-an-auto-purchase/

- Wilcox David. (1989) “Social Security Benefits, Consumption Expenditures, and the Life Cycle Hypothesis.” Journal of Political Economy, 97(2), 288–304. [Google Scholar]