Abstract

Background and Aims

The perennial C4 grass Urochloa humidicola is widely planted on infertile acidic and waterlogging-prone soils of tropical America. Waterlogging results in soil anoxia, and O2 deficiency can reduce nutrient uptake by roots. Interestingly, both nutrient deficiencies and soil waterlogging can enhance root cortical cell senescence, and the increased gas-filled porosity facilitates internal aeration of roots. We tested the influence of nutrient supply and root-zone O2 on root traits, leaf nutrient concentrations and growth of U. humidicola.

Methods

Plants were grown in pots in a completely randomized design under aerated or stagnant deoxygenated hydroponic conditions and six nutrient regimes, with low to high concentrations of all essential elements, for 28 d in a controlled-temperature greenhouse. The standard acid solution (SAS) used was previously designed based on infertile acidic soils of the tropical America savannas, and step increases in the concentration of SAS were used in aerated or deoxygenated 0.1 % agar solution, which mimics changes in gas composition in waterlogged soils. Measurements included shoot and root growth, root porosity, root anatomy, radial O2 loss, and leaf tissue nutrient concentrations.

Key Results

Shoot dry mass was reduced for plants in stagnant compared with aerated conditions at high, but not at low, levels of mineral nutrition. In low-nutrition stagnant solution, roots were shorter, of greater porosity and had smaller radial thickness of the stele. Suberized lamellae and lignified sclerenchyma, as well as a strong barrier to radial O2 loss, were documented for roots from all treatments. Leaf nutrient concentrations of K, Mg and Ca (but not N, P and S) were higher in aerated than in stagnant conditions.

Conclusions

Under low-nutrient conditions, plant growth in stagnant solution was equal to that in aerated solution, whereas under higher-nutrient regimes growth increased but dry mass in stagnant solution was less than in aerated solution. Slow growth in low-nutrient conditions limited any further response to the low O2 treatment, and greater porosity and smaller stele size in roots would enhance internal O2 movement within roots in the nutrient-limited stagnant conditions. A constitutive barrier to radial O2 loss and aerenchyma facilitates O2 movement to the tips of roots, which presumably contributes to maintaining nutrient uptake and the tolerance of U. humidicola to low O2 in the root-zone.

Keywords: Tropical forage grass, Urochloa humidicola, mineral nutrition, waterlogging tolerance, root:shoot ratio, root anatomy, root porosity, root radial oxygen loss, leaf tissue nutrient concentrations

INTRODUCTION

Waterlogged soils are very low in O2 and levels of some macronutrients can also be low owing to dilution, leaching and, in the case of N, denitrification (Trought and Drew, 1980a; Drew, 1991; Elzenga and van Veen, 2010). Roots suffer O2 deficiency when in waterlogged soil, a condition that can be relieved by formation of aerenchyma to provide a low-resistance path for internal O2 movement along the roots (Armstrong, 1979). In addition to aerenchyma, many waterlogging-tolerant species also form a barrier in the outer part of the root to restrict radial O2 loss (ROL) to the rhizosphere (Armstrong, 1979; Colmer, 2003a; Yamauchi et al., 2018). Nevertheless, root tissue O2 deficits can impede the uptake and translocation of nutrients, at least in non-wetland species (Trought and Drew, 1980a; Atwell and Steer, 1990; Gibbs et al., 1998; Colmer and Greenway, 2011). Shoot tissue nutrient (especially N) concentrations are often reduced by low O2 or waterlogged conditions (Kuiper et al., 1994; Huang et al., 1995; Wiengweera et al., 1997; Wiengweera and Greenway, 2004; Smethurst et al., 2005; Pang et al., 2006; Shabala et al., 2014; Herzog et al., 2016). It has been suggested that increased nutrient availability might counteract the deleterious effect of low O2 on plant growth (Day, 1987; Huang et al., 1995; Xie et al., 2009).

Aerenchyma, the large gas-filled spaces that form in the cortex of roots of many species, enables O2 movement from shoots into and along roots and thus aerobic respiration by root cells (Armstrong, 1979). Aerenchyma formation is triggered by ethylene, which increases within roots in waterlogged soils (Yamauchi et al., 2018). Aerenchyma can also be induced in roots, at least of the non-wetland species Zea mays, under aerobic conditions by a shortage of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium or sulphate (Drew et al., 1989; Bouranis et al., 2003; Fan et al., 2003; Postma and Lynch, 2011). Under waterlogged conditions, the internal supply of O2 to the roots is essential for nutrient uptake and translocation (Gibbs et al., 1998) because respiration generates the ATP required to fuel the membrane-bound H+-ATPase pumps needed to establish the H+ electrochemical gradient used to drive secondary energy-dependent ion transport (Armstrong and Drew, 2002; Colmer and Greenway, 2011). In addition, aerenchyma formation reduces the number of cells per unit root volume and thus reduces the metabolic costs of root exploration for limited resources, which can be of adaptive value in nutrient-deficient conditions (Fan et al., 2003; Lynch and Brown, 2008). A trade-off resulting from aerenchyma formation may be reduced radial transport of nutrients due to the reduction in living cortical tissue (Hu et al., 2014).

Perennial Urochloa species (syn. Brachiaria spp., Torres-Gonzalez and Morton, 2005) are widely planted as tropical forage grasses, especially in regions of tropical America dominated by low-fertility acidic soils (Rao et al., 1993; Miles et al., 2004). Extensive areas of tropical America are, however, not only nutrient-poor but also prone to episodes of waterlogging (Hirabayashi et al., 2013). Waterlogging-tolerant genotypes of Urochloa humidicola have been planted in extensive wet regions of tropical America dedicated to livestock production; the waterlogging tolerance of these plants is associated with traits contributing to internal aeration of the roots (Cardoso et al., 2013, 2014; Jiménez et al., 2015).

The aim of this study was to test the influence of nutrient supply on the responses of U. humidicola to stagnant deoxygenated conditions in the root zone, compared with aerated controls. We used a low-ionic-strength nutrient solution designed to simulate the activities of macronutrients that limit plant growth on infertile acidic soils of the tropical America savannas (Wenzl et al., 2003), as used previously in experiments on Urochloa grasses (Rao et al., 2006; Wenzl et al., 2006; Arroyave et al., 2013); here we call this solution the ‘standard acid solution’ (SAS). This solution was used at the recommended level (SAS) and also used when increased in concentration in several steps to obtain a dose-response curve (see Materials and Methods). Having a range of concentrations of SAS can reflect the extremely variable nutrient conditions among acidic soils (Rao et al., 1993; Uexküll and Mutert, 1995; Zech et al., 1997), and was also of importance to test for capacity to support plant growth in aerated and stagnant deoxygenated agar solutions. Thus, the SAS solutions of various concentration levels were combined with the deoxygenated stagnant agar method to impose root-zone O2 deficiency (Wiengweera et al., 1997). Dissolved agar (0.1 % w/v) prevents convection and, with pre-flushing with N2 gas to purge O2, this provides a deoxygenated stagnant nutrient solution that can mimic the changes in gas composition (low O2 and elevated ethylene) that occur in waterlogged soils (Wiengweera et al., 1997). The lack of convection in the stagnant 0.1 % agar solution, however, means that ions move to the roots via diffusion or mass flow with transpiration, so that if the nutrients are too dilute the zones adjacent to roots then become too depleted and nutrient deficiencies can occur (Wiengweera et al., 1997). This localized depletion of nutrients adjacent to roots contrasts with the situation in aerated solutions with turbulent mixing.

We therefore tested the response of U. humidicola to increased concentrations of the purpose-designed nutrient solution (SAS; Wenzl et al., 2003), both in stagnant deoxygenated agar solution and aerated solution, to assess possible interactions between mineral nutrition, root aeration and growth of U. humidicola. The following hypotheses were tested: (1) increased levels of nutrients improve growth in both stagnant low-O2 and aerated root-zone conditions; (2) low-nutrient conditions will increase the gas-filled porosity of roots and in turn improve tolerance of stagnant low-O2 conditions, although (3) if growth under low-nutrient conditions is already only modest, then further reductions in growth under stagnant low-O2 conditions would be limited. Defining the SAS–dose response curves in combination with the deoxygenated stagnant agar is essential for the development of a phenotyping method suitable for evaluation of plant waterlogging tolerance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material and growth conditions

Vegetative propagules (containing one leaf and one node) of Urochloa humidicola cv. ‘Tully’ were harvested from 11-week-old plants grown in potting mix in a glasshouse (34/19 °C day/night air temperatures) located in Perth, Western Australia. This cultivar was chosen as it is widely grown in extensive wetland zones in the American tropics (Keller-Grein et al.,1998).These propagules were transferred into acidic (pH ~4.2; eight vegetative propagules per pot) low-ionic-strength nutrient solution (SAS; Wenzl et al., 2003) in aerated 4.5-L pots for 7 d, during which new growth of roots and leaves occurred. Plants were held by foam in holes in the lid of each pot. The SAS solution has been used to evaluate the adaptation of Urochloa species to acid soils (Wenzl et al., 2006). Plants were then transferred to 4.5-L pots (four plants per pot; the other two plants were used for initial harvests and the remaining two were discarded based on growth performance) containing either aerated (controls) or stagnant deoxygenated 0.10 % (w/v) agar nutrient solution of five concentrations (SAS×1, SAS×2, SAS×5, SAS×10, SAS×20). For comparative purposes, there was also a modified Hoagland solution (e.g. McDonald et al., 2001a) treatment, as this more common nutrient solution had been used to grow various species in stagnant deoxygenated agar (e.g. McDonald et al., 2001b, 2002; Garthwaite et al., 2003). In summary, the experimental design was 2 aeration treatments × 6 nutrient solution compositions × 3 replicates; harvests (sampings) were taken at 0 (initial) and after 28 d of treatments.

The SAS contained (in µm): 500 NO3−, 50 NH4+, 300 K+, 300 Ca2+, 150 Mg2+, 160 Na+, 5.0 H2PO4−, 286 SO42−, 5.0 Fe-EDTA, 1.0 Mn2+, 1.0 Zn2+, 0.20 Cu2+, 6.0 H3BO3, 5.0 SiO32−, 0.0010 MoO42− and 332.4 Cl−; HCl was used to adjust the pH to 4.2 (Wenzl et al., 2003). In addition, 0.0010 µm Ni2+ was added to the SAS solution. Modified Hoagland’s solution contained (in mm): 3.95 K+, 1.50 Ca2+, 0.40 Mg2+, 0.625 NH4+, 4.375 NO3−, 1.90 SO42−, 0.20 H2PO4−, 0.20 Na+ and 0.10 H4SiO4, and the micronutrients (in µm) 50 Cl−, 25 H3BO3, 2.0 Mn2+, 2.0 Zn2+, 1.0 Ni2+, 0.50 Cu2+, 0.50 MoO42− and 50 Fe-EDTA. The modified Hoagland solution also contained 2.5 mm MES and the pH was adjusted to 6.5 with KOH. An additional 2.5 mm NH4NO3 was added to the modified Hoagland solution when containing 0.10 % agar (to prevent any possible diffusion limitation for N supply; cf. Wiengweera et al., 1997), but no additional NH4NO3 was added to the aerated modified Hoagland solution as bubbling with air resulted in continuous mixing of the solution. SAS×20 solutions contained greater concentrations of all nutrients than the modified Hoagland solution except for those of P, Mo and Ni. (For ease of comparison these nutrient solutions are listed in Supplementary Data Table S1.) The stagnant solutions contained dissolved agar at 0.10 % (w/v) to prevent convection, and these solutions were pre-flushed with high-purity N2 gas to purge O2 before the plants were inserted. This stagnant medium with low O2 and accumulation of ethylene in the roots simulates the changes in gas composition that occur in waterlogged soils; they are better than, for example, N2-flushed solutions, in which ethylene is purged with consequences for plant acclimation, such as less development of root gas-filled porosity (Wiengweera et al., 1997). Nutrient solution in each pot was renewed weekly, during which process care was taken to avoid mixing in O2 when syphoning these solutions from the preparation tanks into each individual pot, after which the lid holding the plants was immediately placed onto the new pot. The experiment was conducted in a temperature-controlled glasshouse with natural sunlight during March and April 2017 in Perth (Australia) at 30/25 °C day/night air temperatures. Pots were arranged in a completely randomized design and re-randomized each week when the nutrient solutions were renewed.

Radial O2 loss along roots

We measured ROL along intact roots when in an O2-free medium using root-sleeving platinum electrodes (Armstrong and Wright, 1975). Briefly, after 25–26 d of treatments, plants with intact root systems were each inserted into a Perspex chamber filled with deoxygenated solution containing 0.10 % (w/v) agar, 5.0 mm KCl and 0.50 mm CaSO4. The shoot base was held by wet cotton wool in a hole in a rubber lid fitted to the top of each chamber, so that the roots were in the O2-free medium and the shoot was in air. For one plant per treatment, ROL was measured along one root (80–150 mm in length) at positions 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80 and 90 mm from the root apex (centre of the platinum cylinder at these distances). The objective was to compare plants from aerated versus stagnant treatments (with one replicate from each nutrient level; the time-consuming nature of these measurements prohibited evaluation of all replicates for each nutrient regime) to determine whether roots of U. humidicola possess a barrier to ROL and whether any such barrier is constitutive or inducible (cf. Colmer, 2003b, for rice). In roots from aerated treatments, measurements were restricted to up to 40 mm behind the apex only, owing to lateral roots preventing the further movement of the cylindrical electrode along the root. Measurements were taken at 30 °C with PAR at shoot height of 150 µmol m–2 s–1. Diameters of the roots at each position were measured using digital callipers.

Root porosity

Porosity (%, gas volume per unit root volume) was measured for root samples after 27 d of treatments by determining root buoyancy before and after vacuum infiltration with water using the procedure by Raskin (1983), and the modified equations by Thomson et al. (1990). Four to five representative roots (~100 mm in length) were excised from one plant from each pot, lateral roots were excised, and main axes were used in the measurements. One out of the four plants in each pot was used for this measurement.

Harvests

Harvests (plant samplings) were conducted at 0 and after 28 d of treatments. Briefly, two plants from each pot were sampled (for both harvests two pooled plants per replication were used for analysis) and both were divided into green and dead leaves, stems and roots. One of the other two plants in each pot had previously been used for measurements of root porosity, or for root ROL measurements (see above). Maximum root length and the total numbers of roots (all roots on these cuttings were nodal/adventitious roots) and stems were recorded. Roots and the stem base were rinsed three times, for 1 min each time, in 1.5 mm CaSO4. Stems and leaves were rinsed with deionized water for several seconds. Samples were oven-dried at 60 °C for 3 d and dry weights were determined. Two pooled plants per replicate were used for samplings and the mean, expressed on a per plant basis, was used for each replicate. The shoot relative growth rate was calculated from the dry mass data taken at the initial and final harvests, using the formula given by Hunt (1978).

Leaf tissue nutrient concentration analyses

Oven-dried leaf samples were ground to a fine powder using an automated tissue homogenizer (2010 Geno/Grinder, SPEX Sample Prep, Metuchen, USA). Subsamples of ~250 mg were digested with boiling HNO3 and HClO4 and appropriate dilutions of the digestates were analysed for P, K, Ca, Mg and S using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, Perkin Elmer, MA, USA). Nitrogen concentrations in the dry leaf powders were determined using an automated nitrogen–carbon analyser (Sercon, Crewe, UK). Lucerne (Medicago sativa) and spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves were used as reference tissues for confirmation of the reliability of the analyses.

Root anatomy

One randomly selected root (~100 mm in length) was excised from one plant from each pot, preserved in 1.6 % (v/v) paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, and stored at 4 °C. Segments (10 mm long) were excised from roots at distances of 45–55 mm behind the apex and then embedded in 5 % (w/v) agar in warm water. Cross-sections were obtained by cutting the agar blocks using a vibrating microtome (Vibratome 3000 Sectioning System, The Vibratome Company, St Louis, MO, USA). Adhered agar was removed by treating cross-sections with clearing solution (85 % lactic acid saturated with chloride hydrate) for 1 h at 70 °C (Lux et al., 2005) and the sections were then washed several times with deionized water. Cell wall suberization was visualized by staining cross-sections with 0.01 % (w/v) Fluorol Yellow 088 in polyethylene glycol–glycerol for 1 h (Brundrett et al., 1991) and viewing them under UV light (Axioscope2 plus, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany; excitation G365, emission LP397). Cell wall aldehyde groups of lignin were visualized by staining root cross-sections with phloroglucinol-HCl for several minutes (Jensen, 1962). Syringyl groups of lignin were visualized by treating root cross-sections successively with 1 % (w/v) KMnO4, 12 % HCl and a concentrated solution of ammonia for the Mäule reaction (Kutscha and Gray, 1972). These cross-sections were viewed under white light microscope (Axioscope2 plus, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). All cross-sections were photographed with a Zeiss AxioCam digital camera. Root diameter, root cross-sectional area and the diameter (thickness) of the stele ~50 mm behind the apex were determined using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA).

Statistical analyses

Two-way ANOVA was used to test for statistical differences between the aeration and nutrition treatments for the different variables measured. The post-ANOVA Duncan test evaluated differences between the means of the various treatments. Statistical analyses were carried out using the Agricolae library of the statistical software R (Mendiburu, 2014).

RESULTS

Growth of Urochloa in aerated or stagnant solutions with increasing nutrient concentrations

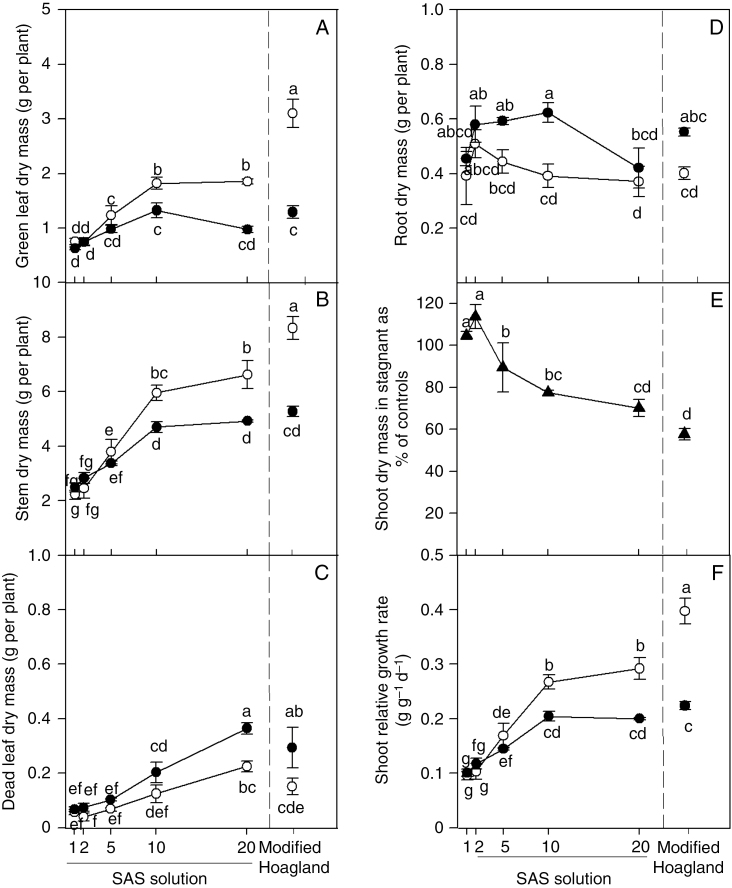

In aerated conditions, green leaf dry mass increased 2.4-fold and stem dry mass 3-fold from the lowest to the highest SAS concentrations; the increases were progressive with the exceptions of the increments from SAS×1 to SAS×2 and from SAS×10 to SAS×20 (Fig. 1A, B). In stagnant conditions, green leaf dry mass increased 2.1-fold and stem dry mass 1.9-fold from plants in SAS×1 to the maximum values attained by the plants in the SAS×10 and SAS×20 solutions, respectively (Fig. 1A, B). Both green leaf dry mass and stem dry mass were similar for the plants in the two aeration treatments when at low nutrient supply, but when the nutrient concentrations had been increased to SAS×10 and SAS×20 both the leaf and stem dry masses were higher for plants in aerated solution than for those in stagnant solution (P < 0.001; Fig. 1A, B). Dead leaf dry mass reached maximum values in SAS×20 treatments, being 0.23 g per plant in aerated and 0.36 g per plant in stagnant conditions, representing 12 and 37 %, respectively, of the amount of green leaves (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Plants of U. humidicola grown in aerated (open symbols) or deoxygenated stagnant (black symbols) solutions for 4 weeks at different nutrient concentrations. SAS solutions: 1, SAS×1; 2, SAS×2; 5, SAS×5, etc. Modified Hoagland solution was included as an additional treatment for comparison. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences across all treatments (P < 0.05, Duncan test).

Root dry mass was, overall, not significantly affected by increasing nutrient concentrations in either aerated or stagnant growth conditions (P = 0.06; Fig. 1D), but for SAS×10 root dry mass was higher for plants in stagnant than in aerated conditions (P < 0.001; Fig. 1D). Shoot dry mass of U. humidicola under stagnant conditions, expressed as the percentage of controls (aerated conditions), decreased from 113 % in SAS×2 to 70 % in SAS×20 plants (Fig. 1E). Shoot relative growth rate was, on average across the SAS nutrient regimes, 1.3-fold higher for plants in aerated conditions in comparison with those in stagnant conditions. Shoot relative growth rate increased 3.1-fold in aerated and 2-fold in stagnant solutions from SAS×1 to SAS×20 treatments (Fig. 1F).

Comparison of these growth parameters for plants in SAS×20 with those in modified Hoagland solution shows that in aerated conditions the plants in the modified Hoagland solution had greater green leaf dry mass (Fig. 1A) and stem dry mass (Fig. 1B) than plants in SAS×20. However, in stagnant treatments there were no significant differences for either green leaf dry mass or stem dry mass between plants in the modified Hoagland solution and SAS×20 treatments (Fig. 1A, B). Dead leaf and root dry masses did not differ between plants in the modified Hoagland solution and SAS×20 either in aerated or stagnant conditions (Fig. 1C, D).

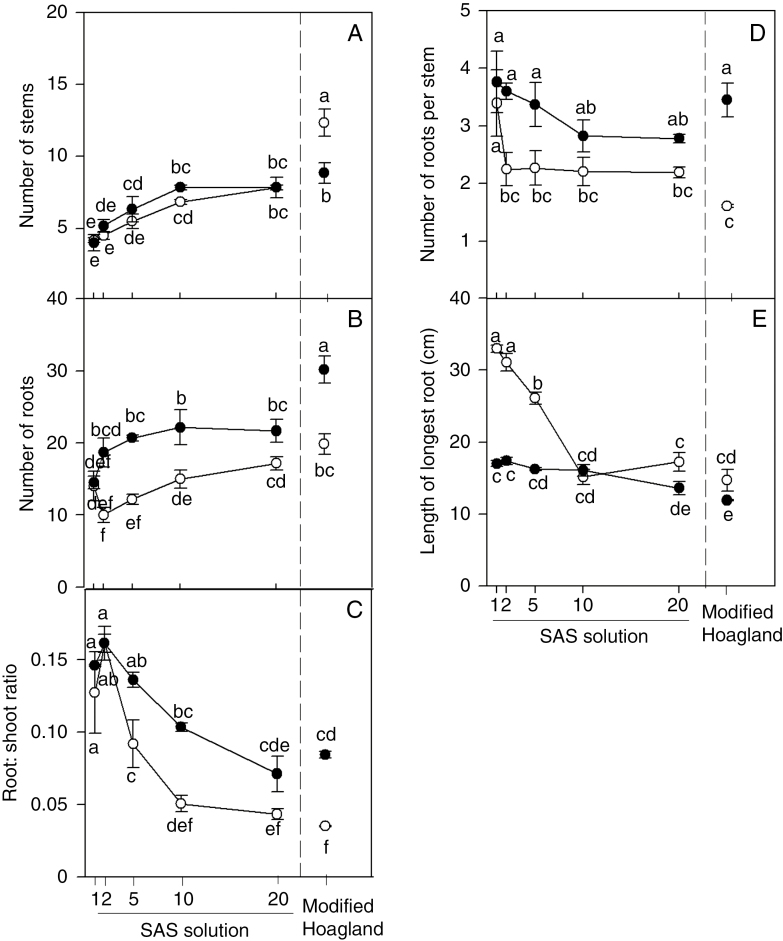

The number of stems increased, with a similar response for plants in aerated or stagnant conditions, when the nutrient concentration increased (Fig. 2A). Averaged across the SAS nutrient regimes, the total number of roots was 1.4-fold higher for plants in stagnant conditions in comparison with those in aerated conditions (Fig. 2B), and the number of roots per stem was 1.3-fold higher for plants in the stagnant conditions (Fig. 2D). By contrast, the longest root was on average 33 % shorter for plants in stagnant conditions than those in the aerated solutions. Root:shoot ratio was higher in plants in stagnant than in aerated conditions for plants in SAS×5 and SAS×10 (P < 0.001; Fig. 2C). In both aerated or stagnant conditions, root:shoot ratio tended to decrease with increasing nutrient concentration in the solution (Fig. 2E). In either aerated or stagnant conditions, increased nutrient concentrations decreased the length of the longest root, from 33 (SAS×1) to 17 cm (SAS×20) in aerated conditions and from 17 (SAS×1) to 14 cm (SAS×20) in stagnant conditions (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Plants of U. humidicola grown in aerated (open symbols) or deoxygenated stagnant (black symbols) solutions for 4 weeks at different nutrient concentrations. SAS solutions are as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05, Duncan test).

Plants in modified Hoagland solution had a greater number of stems than plants in the SAS×20 treatment when aerated, but there was no difference between plants in these nutrient solutions when in stagnant conditions (Fig. 2A). By contrast, the number of roots did not differ for plants in the modified Hoagland solution and SAS×20 when both were aerated, but root numbers were higher in the modified Hoagland solution than in the SAS×20 treatment when both were stagnant (Fig. 2B). The root:shoot ratio, the number of roots per stem and the length of the longest root did not differ between plants in the modified Hoagland solution and SAS×20 treatments when either aerated or stagnant (Fig. 2C–E).

Root porosity and anatomy

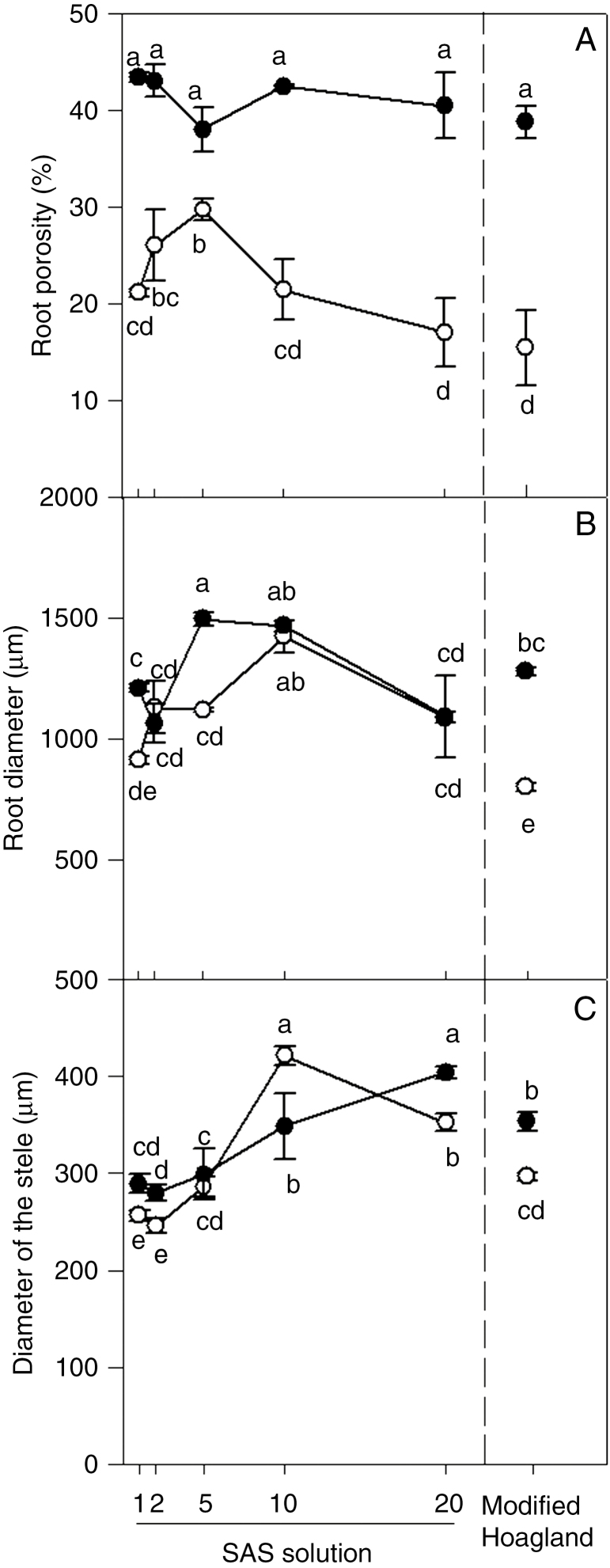

Porosity of roots in the SAS treatments was on average 1.8-fold greater in stagnant conditions (42 % gas volume/root volume) when compared with roots from aerated conditions (23 % gas volume/root volume) (Fig. 3A). In stagnant conditions, root porosity was not influenced by increasing the nutrients supplied (P = 0.3; Fig. 3A). In aerated conditions, however, root porosity initially increased from 21 % in SAS×1 to 30 % in SAS×5 and then decreased to 17 % in SAS×20 (Fig. 3A). Comparison of plants in SAS×20 with those in modified Hoagland solution showed no differences in root porosity either in aerated or stagnant conditions (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Plants of U. humidicola grown in aerated (open symbols) or deoxygenated stagnant (black symbols) solutions for 4 weeks at different nutrient concentrations. SAS solutions are as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05, Duncan test).

Root diameter was affected by aeration treatment and by nutrient concentration in the solution (both P < 0.001; Fig. 3B); diameters tended to increase with nutrient concentration and then decrease again at the highest nutrient levels (SAS×20). The diameter of roots in aerated conditions varied from 910 µm in SAS×1 to 1421 µm in SAS×10 and in stagnant treatments from 1062 µm in SAS×2 to 1495 µm in SAS×5. Root diameters were equal or larger for plants in stagnant versus aerated conditions. The thickness (i.e. diameter) of the stele was higher in roots in stagnant compared with aerated conditions, with the exceptions of SAS×5 and SAS×10 (Fig. 3C). The thickness of the stele tended to increase in both aerated and stagnant conditions when the nutrient supply was increased (Fig. 3C). Comparison of plants in SAS×20 with those in modified Hoagland solution showed that root diameter was similar for plants in stagnant conditions, but in aerated conditions root diameter was smaller in modified Hoagland solution than in the SAS×20 treatment (Fig. 3B). The thickness of the stele was also lower in roots grown in the aerated modified Hoagland solution compared with those in the aerated SAS×20 treatment (Fig. 3C).

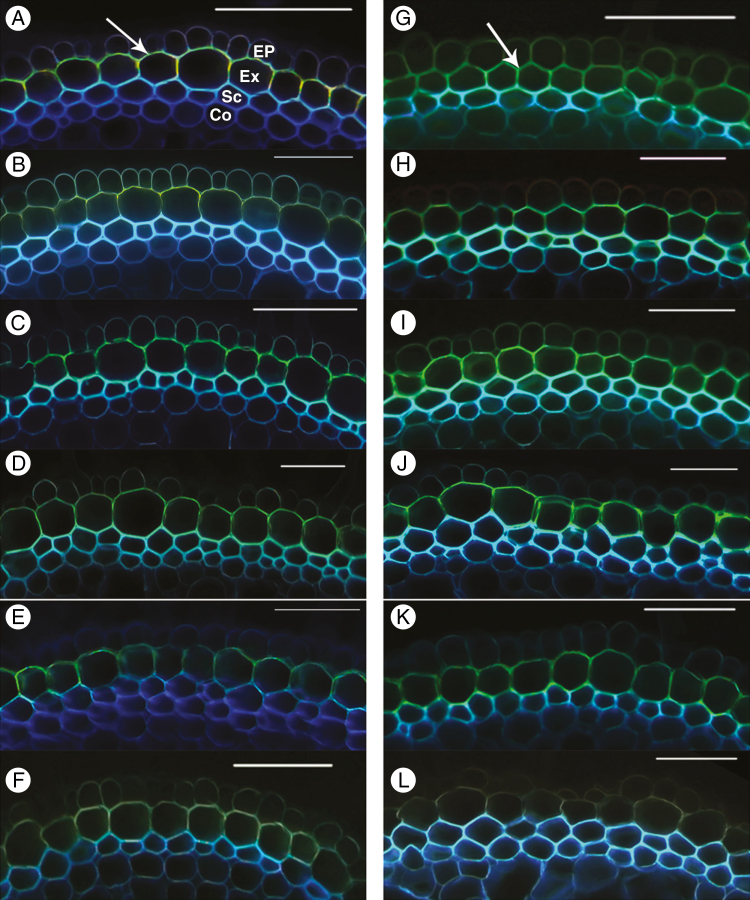

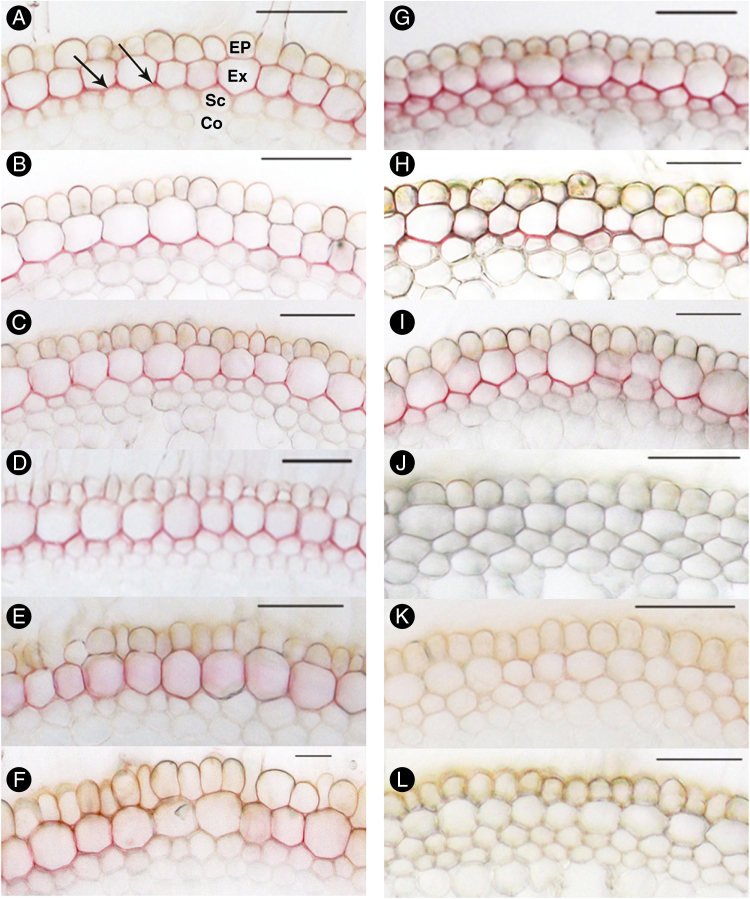

Suberin deposition, detected by yellow–green fluorescence in cross-sections stained with Fluorol Yellow 088, was evident in the exodermis of roots of plants grown in either aerated or stagnant treatments (Fig. 4). Major differences in suberin deposition in the exodermis were not evident in roots from the different SAS treatments (Fig. 4A–E, G–K). Roots of plants grown in modified Hoagland solution exhibited the faintest yellow fluorescence in both aerated and stagnant conditions (Fig. 4F, L).

Fig. 4.

Development of suberin lamellae of U. humidicola grown in aerated (left column, A–F) or deoxygenated stagnant solutions (right column, G–L) for 4 weeks at different nutrient concentrations (A, G, SAS×1; B, H, SAS×2; C, I, SAS×5; D, J, SAS×10; E, K, SAS×20; F, L, modified Hoagland solution). Cross-sections were made at 50 mm behind the apex, stained with Fluorol Yellow 088 and viewed under UV illumination. The suberin deposition in exodermal cells is indicated by a yellow–green colour; arrows in (A) and (G) point to examples. Ep, epidermis; Ex, exodermis; Sc, sclerenchyma; Co, cortical cells. Scale bars = 100 µm.

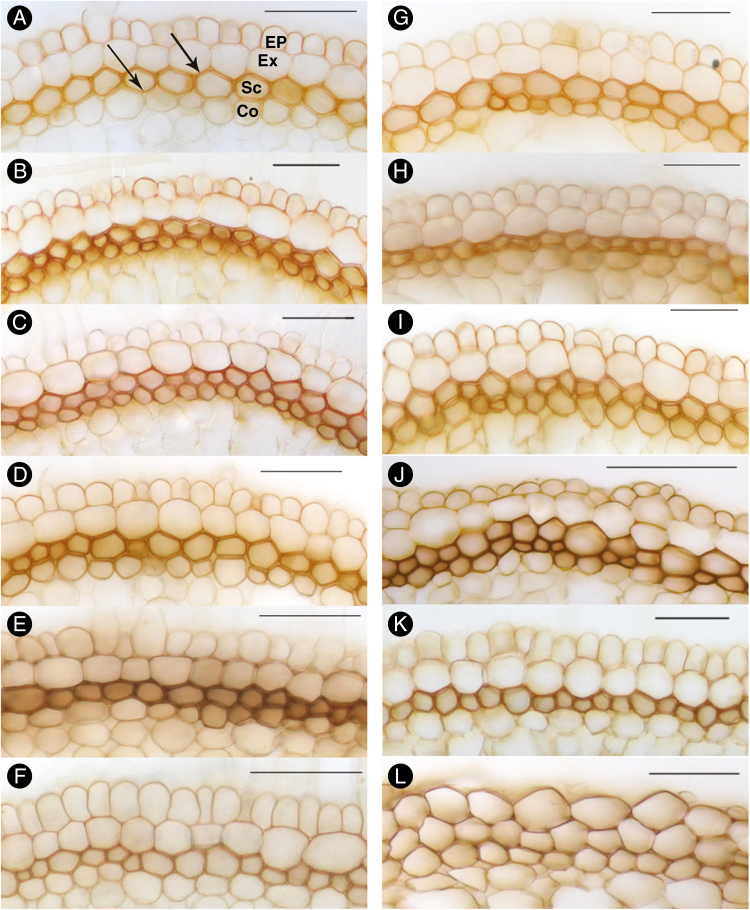

Aldehyde groups of lignin, indicated by orange/red staining with phloroglucinol-HCl, were detected in the exodermis of roots of plants grown in either aerated or stagnant treatments (Fig. 5). In aerated conditions, lignin deposits were present in the exodermis of roots from all nutrient level treatments (Fig. 5A–F). However, under stagnant conditions deposition of lignin in the exodermis determined by the phloroglucinol-HCl method was only evident in the lower nutrient level treatments (SAS×1, SAS×2 and SAS×5; Fig. 5G–L). By contrast, syringyl groups of lignin, indicated by brown staining with the Mäule reaction (Kutscha and Gray, 1972), were evident, in this case, in the sclerenchyma layer of roots grown in either aerated or stagnant conditions and at all nutrients levels (Fig. 6). The faintest brown colour was evident in sclerenchyma of roots of plants grown in either aerated or stagnant modified Hoagland solution (Figs 6F, L). No differences in the endodermis were evident for deposition of suberin and lignin between plants grown in aerated or stagnant conditions at the different nutrient levels (Supplementary Data Fig. S1).

Fig. 5.

Lignin deposition in the outer part of the root of U. humidicola grown in aerated (left column, A–F) or deoxygenated stagnant solutions (right column, G–L) for 4 weeks at different nutrient concentrations (A, G, SAS×1; B, H, SAS×2; C, I, SAS×5; D, J, SAS×10; E, K, SAS×20; F, L, modified Hoagland solution). Cross-sections were made at 50 mm behind the apex, and aldehyde groups of lignin were stained red with phloroglucinol-HCl; arrows in (A) point to examples. Ep, epidermis; Ex, exodermis; Sc, sclerenchyma; Co, cortical cells. Scale bars = 100 µm.

Fig. 6.

Development of lignified sclerenchyma of U. humidicola grown in aerated (left column, A–F) or deoxygenated stagnant solutions (right column, G–L) for 4 weeks at different nutrient concentrations (A, G, SAS×1; B, H, SAS×2; C, I, SAS×5; D, J, SAS×10; E, K, SAS×20; F, L, modified Hoagland solution). Cross-sections were made at 50 mm behind the apex, and syringyl groups of lignin were stained orange/brown with KMnO4 and HCl; arrows in (A) point to examples. Ep, epidermis; Ex, exodermis; Sc, sclerenchyma; Co, cortical cells. Scale bars = 100 µm.

Rates of ROL from along intact roots

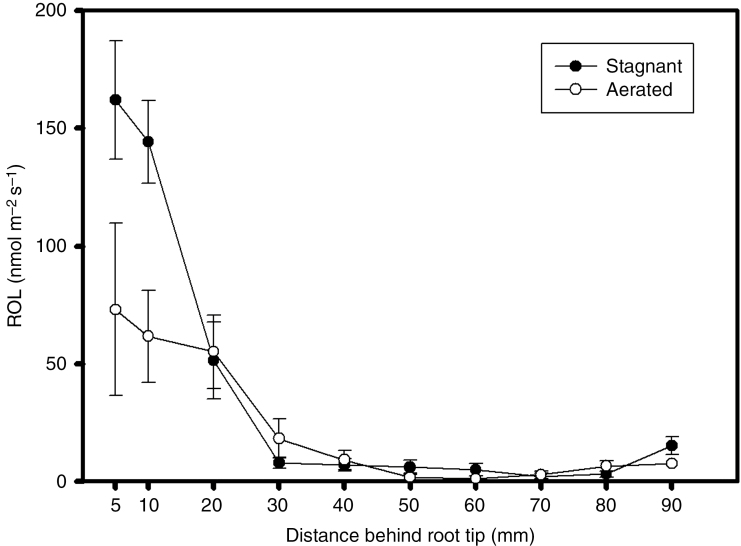

The overall pattern of ROL did not differ between roots of plants grown in either aerated or stagnant nutrient solutions, although the rates of ROL at both 5 and 10 mm behind the apex were on average 2.3-fold higher for roots of plants grown in stagnant than for those in aerated conditions. Nevertheless, for roots of plants grown in either aerated or stagnant conditions the rates of ROL were highest at 5 and 10 mm behind the apex and decreased at more basal positions along the roots, with very low rates at 30 mm and beyond from the apex (Fig. 7). These patterns of decreasing ROL as the root-sleeving electrode was moved towards the root–shoot junction (the source of the O2) and the low rates along these basal zones indicate presence of a tight barrier to ROL (cf. Colmer, 2003a). The rates of ROL from the various individual roots of plants grown at different nutrient levels in either aerated or stagnant conditions are shown in Supplementary Data Figs S2 and S3.

Fig. 7.

Profiles of radial O2 loss (ROL) along intact adventitious roots of U. humidicola grown in aerated or deoxygenated stagnant solutions for 4 weeks at different nutrient concentrations. Roots were of similar length (~130 mm) and data are the means of one plant from each of the nutrient treatments (six replicates ± s.e.) for each aeration treatment.

Leaf nutrient concentrations

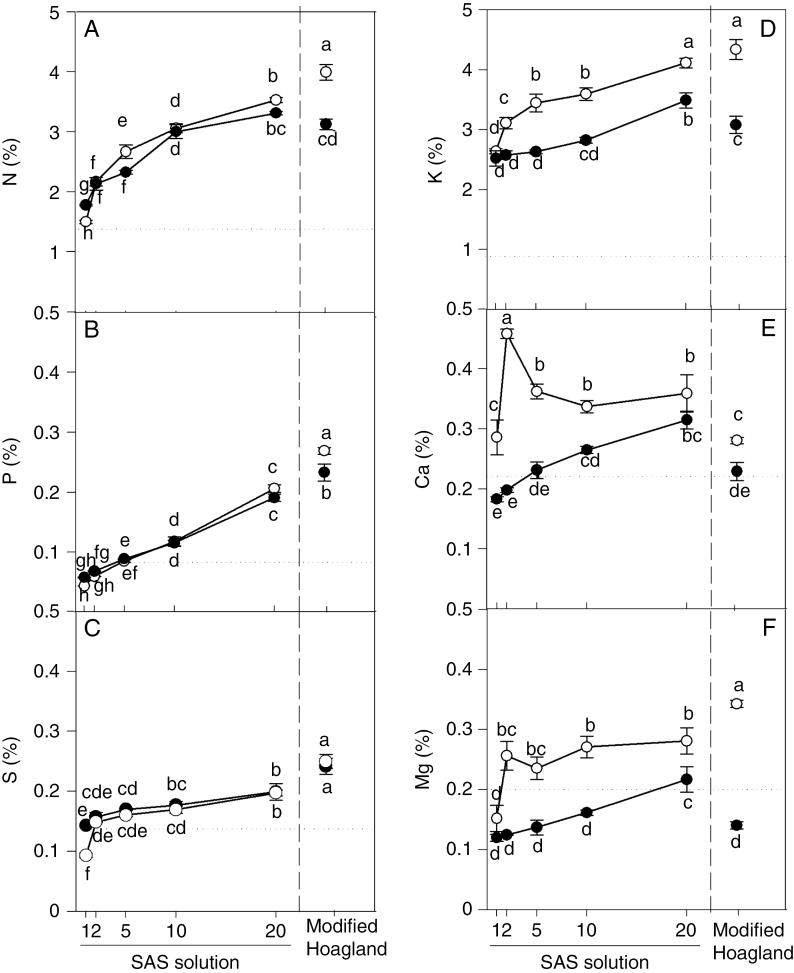

The leaf tissue concentrations of all nutrients increased from the lowest to the highest SAS solutions, irrespective of the aeration condition (Fig. 8A–F). The increases in tissue concentrations of nutrients for plants in SAS×1 to SAS×20 in aerated conditions were in the range of 1.2-fold to 5.2-fold and in stagnant conditions from 1.4-fold to 3.2-fold. For the plants in the series of SAS solutions, the concentrations of N in leaves of plants grown under stagnant conditions did not differ significantly from those in aerated conditions, with the exception of the SAS×1 and SAS×5 treatments (Fig. 8A). Similarly, the concentration of P in leaves did not differ between aerated and stagnant SAS series treatments (Fig. 8B) and the concentration of S only differed in SAS×1 treatments (Fig. 8C). The concentrations of K and Mg in leaves across the SAS treatments were higher in plants grown in aerated than in stagnant conditions, with the exception of the SAS×1 treatment (Fig. 8D, F). Likewise, the concentration of Ca in leaves in SAS solutions was higher in aerated than in stagnant plants, with the exception of the SAS×20 treatments (Fig. 8E).

Fig. 8.

Concentrations of nutrients in leaves (% dry mass) of plants of U. humidicola grown in aerated (open symbols) or deoxygenated stagnant (black symbols) solutions for 4 weeks at different nutrient concentrations. SAS solutions are as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Horizontal dotted lines refer to the critical deficiency leaf concentrations for the tropical C4 grass Andropogon spp., which have been used (here and by others) as a reference for U. humidicola. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05, Duncan test).

In control conditions, the concentrations of N, P, S and Mg in leaves of plants in modified Hoagland solution were higher than in any of the SAS treatments (Fig. 8A–C, F) and the concentration of K in leaves did not differ between modified Hoagland solution and SAS×20 (Fig. 8D), whereas the concentration of Ca was lower in leaves of plants in modified Hoagland solution than in any of the SAS treatments, with the exception of SAS×1 (Fig. 8E). In stagnant conditions, the concentration of N in leaves was similar between modified Hoagland solution and SAS×20 and the concentrations of K, Ca and Mg were lower in leaves of plants in modified Hoagland solution than in those in SAS×20 (Fig. 8A, D–F), whereas the concentrations of P and S were higher in leaves of plants in modified Hoagland solution than in SAS×20 (Fig. 8B, C).

DISCUSSION

This study documents significant interactions between nutrient supply and root-zone O2 availability with respect to the growth of the waterlogging-tolerant perennial C4 grass U. humidicola. In regard to the hypotheses tested, growth increased as the mineral nutrient supply was increased in both the stagnant low-O2 and aerated conditions; however, the response was greater in aerated solution and so growth in stagnant conditions as a percentage of the aerated control decreased as nutrients increased. Thus, the apparent tolerance of stagnant conditions, assessed as the percentage of aerated controls, was greater in low-nutrient conditions, in which modest growth persisted, whereas the high growth potential in high-nutrient conditions was impeded. By analogy, inherently fast-growing genotypes of wheat exposed to a stagnant root-zone suffered more of a reduction in growth than inherently slow-growing genotypes (McDonald et al., 2001b). Indeed, plants with low growth rates may have an adaptive advantage in stressful habitats (Lambers and Poorter, 1992). Noteworthy also was that root gas-filled porosity was relatively high in all stagnant treatments irrespective of nutrient supply, whereas in aerated conditions even for the waterlogging-tolerant U. humidicola, which develops some ‘constitutive’ porosity, the nutrient level had a significant influence on this important root trait. Below we discuss the morphological and physiological adaptations of U. humidicola, and the implications of our findings for phenotyping to select superior genotypes of this forage grass for waterlogging-prone environments.

In either aerated or stagnant solutions, the leaf tissue concentrations of nutrients (N, P, K, Mg, Ca and S) tended to increase when the nutrient solution concentration increased (Fig. 8). The concentrations of the cations K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ were significantly higher in plants in aerated solution than in stagnant solution (Fig. 8D–F). Hypoxia in the root zone can inhibit the uptake and transport of nutrients (Armstrong and Drew, 2002), but this varies between plant species according to their waterlogging tolerance (Colmer and Greenway, 2011). Ion accumulation in wheat shoots was severely inhibited when roots were in anaerobic solutions, with K+ being the most affected, NO3−, PO43− and Mg2+ intermediate and Ca2+ least affected (Trought and Drew, 1980b). Likewise, substantial reductions in net uptake of K+ by roots in low-O2 solutions have been reported in sensitive cereal genotypes, while lower or no reduction was exhibited by more waterlogging-tolerant genotypes [e.g. wheat (Wiengweera and Greenway, 2004) and barley (Pang et al., 2006)].

Under stagnant conditions in SAS×1 and SAS×2 treatments, the concentrations of P and Ca in leaves (Fig. 8B, E) were below the critical concentrations for P of 0.08 % and Ca of 0.21 % (for the tropical C4 grass Andropogon spp., used as a reference for U. humidicola; Salinas and Saif, 1989; Rao et al., 1998). Likewise, under stagnant conditions in all SAS treatments except for SAS×20, the concentration of Mg in leaves was lower (Fig. 8F) than the critical concentration of 0.20 % (Salinas and Saif, 1989; Rao et al., 1998). Notwithstanding the lower concentrations of P, Ca and Mg in leaf tissues of plants grown at either SAS×1 or SAS×2 in stagnant solution, growth was not significantly different from that in the respective aerated controls (Fig. 1A, B); i.e. under these low-fertility conditions the stagnant conditions did not impose additional limitations on growth. However, under stagnant conditions and high nutrition, plants with similar concentrations of N, P and S in leaves achieved ~50 % of the shoot dry mass produced by aerated controls (Supplementary Data Fig. S4). This reduction in growth in the stagnant conditions when high nutrients were supplied, compared with aerated controls, might be due mainly to the lower K, Ca and/or Mg concentrations in leaves of plants in the stagnant treatment in comparison with those in aerated conditions (Fig. 8).

Shoot dry mass was significantly higher in plants in aerated than in stagnant conditions when grown in high-nutrition solutions (SAS×10, SAS×20, modified Hoagland solution) but not in low-nutrition solutions (SAS×1, SAS×2, SAS×5; Fig. 1A, B). A positive growth response was observed up to SAS×10. Interestingly, senescence of older leaves also increased under the higher-nutrient regimes (Fig. 1C). Leaf nutrient analyses revealed that P, Ca and Mg were the most likely limiting nutrients for plant growth in the low-ionic-strength nutrient solutions. Phosphorus mainly but also Ca and Mg are well recognized as limiting plant growth in target soils from infertile tropical savannas (Rao et al., 1993). Under conditions of high Al and the low-nutrient solution SAS×1, uptake of P and Mg were affected more than other nutrients in Urochloa ruziziensis and Urochloa decumbens genotypes (Wenzl et al., 2003). Wenzl et al. (2003) found that only under nutrient-limited conditions a clear interspecific difference in Al sensitivity was evident; Al stress induced greater differences in growth under nutrient-limited conditions than nutrient-sufficient conditions in the sensitive but not the tolerant species. Comparatively, in the present study, the waterlogging-tolerant U. humidicola was not further adversely affected by waterlogging stress when grown in low-nutrient conditions; however, further studies are needed to evaluate waterlogging-sensitive genotypes under such conditions.

Root porosity in SAS treatments was on average 1.8-fold greater in plants grown under stagnant conditions (42 % gas volume/root volume) compared with aerated solutions (23 %) (Fig. 3A). However, for plants in the stagnant treatment there was no significant response of root porosity to the levels of nutrients (Fig. 3A). In contrast to our study, an increase from half- to full-strength nutrient solution reduced the percentage of aerenchyma produced in roots of wheat in flooded sand (Huang et al., 1994). Interestingly, such reductions in the percentage of aerenchyma in roots of wheat were smaller in the waterlogging-tolerant genotype in comparison with the sensitive genotype (Huang et al., 1994). Aerenchyma is a constitutive trait in roots of U. humidicola under aerated conditions and its proportion is further increased under waterlogging conditions (Cardoso et al., 2013, 2014; Jiménez et al., 2015; this study). Evaluations of root porosity in wetland and non-wetland species have indicated that species with low root porosity (~10 %) under drained conditions had the greatest potential to further increase root porosity under stagnant conditions; however, plants with higher constitutive root porosity (25–30 %) exhibited less potential to change (Justin and Armstrong, 1987; Visser et al., 2000). Therefore, as stagnant conditions already increased root porosity to 42 % in U. humidicola, a further increase due to a shortage of nutrients (Drew et al., 1989; Bouranis et al., 2003; Fan et al., 2003; Postma and Lynch, 2011) is unlikely to occur. This amount of porosity in roots of U. humidicola is similar to that found in rice (e.g. Colmer, 2003b) and is in the upper part of the range for wetland species (Justin and Armstrong, 1987).

In aerated conditions, root porosity reached a maximum of 30 % in SAS×5 treatments and decreased to 17 % in higher-nutrient SAS×20 treatments (Fig. 3A). Increases in aerenchyma formation under low-nutrient conditions have been demonstrated for roots of Z. mays, and, unlike the situation during waterlogging, the aerenchyma formation in roots of nutrient-deficient plants was not due to enhanced accumulation of ethylene in roots (Drew et al., 1989). Increased aerenchyma formation under low-nutrient conditions could be stimulated by low K causing the activation of caspase-like proteases that lead to programmed cell death (Shabala, 2011). Moreover, low-K soils had greater effects on aerenchyma formation in roots of Z. mays than low-N and low-P soils (Postma and Lynch, 2011). Previous studies of the interaction of nutrition and aerenchyma formation under aerated (or drained) conditions have focused on the non-wetland species Z. mays (see Introduction section and references above). This study of U. humidicola shows that nutrient deprivation can also increase the porosity of roots in a waterlogging-tolerant wetland plant in addition to the relatively high ‘constitutive’ porosity in these roots, under well-aerated conditions.

For roots in stagnant solutions, porosity and diameter were each similar between plants in SAS×1 and SAS×20 treatments (Fig. 3A, B), whereas the diameter of the stele (and its relative proportion to the root cross-section; Supplementary Data Fig. S5) was lower in SAS×1 than in SAS×20 treatments (Fig. 3C). The stele is a low-porosity tissue with high diffusive resistance to O2 (Armstrong and Beckett, 1987). Thus, a narrower stele represents a reduced length of the radial diffusion path of O2 into the centre of the stele. Moreover, energy-dependent nutrient transport into the xylem occurs within the stele; furthermore, O2 consumption rate is greater in the stele than in the cortical tissue (Armstrong and Beckett, 1987; Armstrong et al., 1991; Aguilar et al., 2003). So, a narrower stele in plants grown under stagnant low-nutrition treatments compared with stagnant high nutrition treatments could result in a reduction in O2 consumption along the roots and consequently an increased amount of O2 being able to diffuse to the root tip to enable respiration and thus root growth and nutrient uptake.

The length of the longest root was shorter in stagnant than in aerated treatments (Fig. 2E). Under stagnant conditions, root length is determined by the internal capacity to transport O2 to the root tip to support growth (Armstrong, 1979). Roots of wheat in aerated solution had rates of extension >2-fold greater than those in stagnant solution and reliant on internal O2 movement (Wiengweera and Greenway, 2004). Likewise, barley roots grown in stagnant solutions stopped growing after reaching ~80 mm in length due to the O2 concentration in the root tip being close to zero (Kotula et al., 2015); O2 consumed or lost radially along the longitudinal diffusion path results in a curvilinear decline in O2 concentration with distance from the source at the root–shoot junction (Armstrong, 1979). In stagnant solutions, the length of the longest root was 1.3-fold greater in SAS×1 than in SAS×20 (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, the root:shoot ratio (dry mass basis) was higher in stagnant than in aerated conditions and also higher at low (SAS×1, SAS×2, SAS×5) compared with high (SAS×20) nutrient concentrations (Fig. 2C). Higher root:shoot ratios under low-nutrient conditions is an adaptive response since root growth contributes to ‘exploring’ for nutrients. Under stagnant conditions, the higher root:shoot ratio was achieved mainly through an increased number of roots, from 14 in aerated to 20 in stagnant plants (Fig. 2B). This increase in the number of adventitious roots could be stimulated by increased ethylene accumulation in roots under stagnant conditions (cf. Visser et al., 1996). The higher number of roots, of greater gas-filled porosity, which facilitates O2 diffusion, would contribute to the waterlogging tolerance of U. humidicola.

Suberized exodermis and lignified sclerenchyma were evident in roots in both aerated and stagnant treatments (Figs. 4–6). No noticeable changes in yellow fluorescence from suberin deposition were found between roots from the various SAS nutrient treatments, but less intense yellow fluorescence was observed in roots from modified Hoagland solution (Fig. 4). Similarly, lignified sclerenchyma was detected in all treatments by the brown staining of cross-sections with the Mäule reaction, being less intense in modified Hoagland solution (Fig. 6). Lignin depositions within exodermal cell walls were detected by the phloroglucinol-HCl staining method in roots from all nutrient treatments in aerated conditions but not in high-nutrient stagnant treatments (SAS×10, SAS×20 and modified Hoagland solution; Fig. 5J–L). The negative reaction of lignin staining in the high-nutrient stagnant condition could be due to the low sensitivity of phloroglucinol to initial lignin development and/or specificity of the stain for certain lignin groups (Jensen, 1962; Kutscha and Gray, 1972; Ullrich, 1955).

The formation of suberized exodermis and/or lignified sclerenchyma in the outer part of the root can restrict ROL from roots to the rhizosphere and thus increase longitudinal O2 diffusion towards the apex (Armstrong, 1979; Kotula et al., 2009; Abiko et al., 2012). Deposition of both lignin and suberin in the outer part of the root in either aerated or stagnant conditions in all aeration and nutrient treatments was consistent with presence of a barrier to ROL (Fig. 7). Patterns of ROL decreased with distance behind the root tip, indicating a high resistance to O2 diffusion between the porous cortex and the exterior of the root in U. humidicola grown either in aerated or stagnant solutions (Fig. 7). Higher rates of ROL at 5 and 10 mm from the apex of roots grown in stagnant solution when compared with roots from aerated solution would have mainly resulted from the greater gas-filled porosity (Fig. 3A) and a lesser number of laterals (data not shown) in the stagnantly grown roots, as the roots selected for analysis were of similar lengths. This reflects a reduced impedance within roots for O2 to diffuse along the roots to the apex. To the best of our knowledge, the presence of a barrier to ROL in U. humidicola is reported here for the first time.

Conclusions

Our results show that U. humidicola in low-nutrient conditions has limited growth and that imposition of a stagnant root zone had no further detrimental effect. Roots with capacity for internal O2 transport likely contributed to enabling shoot growth at levels comparable to the aerated controls in these low-nutrient conditions. The shoot dry mass production of U. humidicola increased as the concentration of the nutrient solution was increased in both the aerated and stagnant conditions (up to SAS×10 in stagnant solution); however, in the high-nutrient regimes the shoot dry mass in aerated controls was greater than in the stagnant conditions. Thus, the adverse effect of a deoxygenated stagnant root zone, expressed as a percentage of the control, was most evident in the higher-nutrient regimes. We therefore recommend that phenotyping for waterlogging tolerance in this species should be conducted under conditions of adequate rather than low nutrient availability, so that differences in growth in response to root-zone O2 treatments, such as those revealed by the stagnant deoxygenated agar method, can be elucidated.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Fig. S1: examples of deposition of suberin and lignin in root endodermis. Fig. S2: longitudinal profile of ROL from intact adventitious roots of Urochloa humidicola grown in aerated solutions for 4 weeks at different nutrient concentrations. Fig. S3: longitudinal profile of ROL from intact adventitious roots of Urochloa humidicola grown in stagnant solutions for 4 weeks at different nutrient concentrations. Fig. S4: shoot dry mass in relation to nutrient concentration in leaves of plants of U. humidicola grown in aerated or deoxygenated stagnant solutions for 4 weeks. Fig. S5: plants of U. humidicola grown in aerated or deoxygenated stagnant solutions for 4 weeks at different nutrient concentrations. Table S1: nutrient concentrations in SAS and modified Hoagland solution used in the present study.

FUNDING

J.C.J. is grateful to COLCIENCIAS (Colombian government) for a PhD scholarship grant and to The University of Western Australia for a reduced-fees scholarship.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Steve Hughes from the Australian Pastures Genebank for providing seeds and Ly Le and John Quealy for assistance during the harvest process. The authors acknowledge use of the Australian Microscopy & Microanalysis Research Facility at the Centre for Microscopy, Characterisation & Analysis, The University of Western Australia, a facility funded by the University, State and Commonwealth Governments. We thank Michael Smirk for support with leaf nutrient measurements.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abiko T, Kotula L, Shiono K, Malik AI, Colmer TD, Nakazono M. 2012. Enhanced formation of aerenchyma and induction of a barrier to radial oxygen loss in adventitious roots of Zea nicaraguensis contribute to its waterlogging tolerance as compared with maize (Zea mays ssp. mays). Plant, Cell and Environment 35: 1618–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar EA, Turner DW, Gibbs DJ, Armstrong W, Sivasithamparam K. 2003. Oxygen distribution and movement, respiration and nutrient loading in banana roots (Musa spp. L.) subjected to aerated and oxygen-depleted environments. Plant and Soil 253: 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong W. 1979. Aeration in higher plants. In: Woolhouse HW, ed. Advances in botanical research, Vol. 7 London: Academic Press, 225–332. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong W, Beckett PM. 1987. Internal aeration and the development of stelar anoxia in submerged roots: multi-shelled mathematical model combining axial diffusion of oxygen in the cortex with radial losses to the stele, the wall layers and the rhizosphere. New Phytologist 105: 221–245. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong W, Drew MC. 2002. Root growth and metabolism under oxygen deficiency. In: Waisel Y, Eshel A, Kafkafi U, eds. Plant roots: the hidden half, 3rd edn. New York: Marcel Dekker, 729–761. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong W, Wright EJ. 1975. Radial oxygen loss from roots: the theoretical basis for the manipulation of flux data obtained by the cylindrical platinum electrode technique. Physiologia Plantarum 35: 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong W, Justin SHFW, Beckett PM, Lythe S. 1991. Root adaptation to soil waterlogging. Aquatic Botany 39: 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyave C, Tolrà R, Thuy T, Barceló J, Poschenrieder C. 2013. Differential aluminum resistance in Brachiaria species. Environmental and Experimental Botany 89: 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Atwell BJ, Steer BT. 1990. The effect of oxygen deficiency on uptake and distribution of nutrients in maize plants. Plant and Soil 122: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bouranis DL, Chorianopoulou SN, Siyiannis VF, Protonotarios VE, Hawkesford MJ. 2003. Aerenchyma formation in roots of maize during sulphate starvation. Planta 217: 382–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundrett MC, Kendrick B, Peterson CA. 1991. Efficient lipid staining in plant material with sudan red 7B or fluorol yellow 088 in polyethylene glycol-glycerol. Biotechnic & Histochemistry 66: 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso JA, Rincón J, Jiménez JC, Noguera D, Rao IM. 2013. Morpho-anatomical adaptations to waterlogging by germplasm accessions in a tropical forage grass. AoB Plants 5: plt047. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso JA, Jiménez JC, Rao IM. 2014. Waterlogging-induced changes in root architecture of germplasm accessions of the tropical forage grass Brachiaria humidicola. AoB Plants 6: plu017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colmer TD. 2003a Long-distance transport of gases in plants: a perspective on internal aeration and radial oxygen loss from roots. Plant, Cell and Environment 26: 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Colmer TD. 2003b Aerenchyma and an inducible barrier to radial oxygen loss facilitate root aeration in upland, paddy and deep-water rice (Oryza sativa L.). Annals of Botany 91: 301–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colmer TD, Greenway H. 2011. Ion transport in seminal and adventitious roots of cereals during O2 deficiency. Journal of Experimental Botany 62: 39–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day FP. 1987. Effects of flooding and nutrient enrichment on biomass allocation in Acer rubrum seedlings. American Journal of Botany 74: 1541–1554. [Google Scholar]

- Drew MC. 1991. Oxygen deficiency in the root environment and plant mineral nutrition. In: Jackson MB, Davies DD, Lambers H, eds. Plant life under oxygen deprivation. The Hague: SPB Academic Publishers, 303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Drew MC, He CJ, Morgan PW. 1989. Decreased ethylene biosynthesis and induction of aerenchyma by nitrogen- or phosphate-starvation in adventitious roots of Zea mays L. Plant Physiology 91: 266–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzenga JTM, Van Veen H. 2010. Waterlogging and plant nutrient uptake. In: Mancuso S, Shabala S, eds. Waterlogging signaling and tolerance in plants. Heidelberg: Springer, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fan MS, Zhu JM, Richards C, Brown KM, Lynch JP. 2003. Physiological roles for aerenchyma in phosphorus-stressed roots. Functional Plant Biology 30: 493–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthwaite AJ, von Bothmer R, Colmer TD. 2003. Diversity in root aeration traits associated with waterlogging tolerance in the genus Hordeum. Functional Plant Biology 30: 875–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J, Turner DW, Armstrong W, Darwent MJ, Greenway H. 1998. Response to oxygen deficiency in primary maize roots. I. Development of oxygen deficiency in the stele reduces radial solute transport to the xylem. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 25: 745–758. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog M, Striker GG, Colmer TD, Pedersen O. 2016. Mechanisms of waterlogging tolerance in wheat – a review of root and shoot physiology. Plant, Cell and Environment 39: 1068–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirabayashi Y, Mahendran R, Koirala S, et al. 2013. Global flood risk under climate change. Nature Climate Change 3: 816–821. [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Henry A, Brown KM, Lynch JP. 2014. Root cortical aerenchyma inhibits radial nutrient transport in maize (Zea mays). Annals of Botany 113: 181–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Johnson JW, NeSmith DS, Bridges DC. 1994. Growth, physiological and anatomical responses of two wheat genotypes to waterlogging and nutrient supply. Journal of Experimental Botany 45: 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Johnson JW, NeSmith DS, Bridges DC. 1995. Nutrient accumulation and distribution of wheat genotypes in response to waterlogging and nutrient supply. Plant and Soil 173: 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt R. 1978. Plant growth analysis. London: Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen WA. 1962. Botanical histochemistry. San Francisco: Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez JC, Cardoso JA, Dominguez M, Fischer G, Rao I. 2015. Morpho-anatomical traits of root and non-enzymatic antioxidant system of leaf tissue contribute to waterlogging tolerance in Brachiaria grasses. Grassland Science 61: 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Justin SHFW, Armstrong W. 1987. The anatomical characteristics of roots and plant response to soil flooding. New Phytologist 106: 465–495. [Google Scholar]

- Keller-Grein G, Mass BL, Hanson J. 1998. Natural variation in Brachiaria and existing germoplasm collections. In: Miles JW, Maass BL, do Valle CB, eds. Brachiaria: biology, agronomy and improvement. Cali: CIAT, 18–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kotula L, Ranathunge K, Schreiber L, Steudle E. 2009. Functional and chemical comparison of apoplastic barriers to radial oxygen loss in roots of rice (Oriza sativa L.) grown in aerated or deoxygenated solution. Journal of Experimental Botany 60: 2155–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotula L, Clode PL, Striker GG, et al. 2015. Oxygen deficiency and salinity affect cell-specific ion concentrations in adventitious roots of barley (Hordeum vulgare). New Phytologist 208: 1114–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper PJC, Walton CS, Greenway H. 1994. Effect of hypoxia on ion uptake by nodal and seminal roots of wheat. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 32: 267–276. [Google Scholar]

- Kutscha NP, Gray JR. 1972. The suitability of certain stains for studying lignification in balsam fir, Abies balsamea L. Mill. Technical Bulletin, Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station, no. 53. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald MP, Galwey NW, Colmer TD. 2001a Waterlogging tolerance in the tribe Triticeae: the adventitious roots of Critesion marinum have a relatively high porosity and a barrier to radial oxygen loss. Plant, Cell and Environment 24: 585–596. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald MP, Galwey NW, Ellneskog-Staam P, Colmer TD. 2001b Evaluation of Lophopyrum elongatum as a source of genetic diversity to increase the waterlogging tolerance of hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum). New Phytologist 151: 369–380. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald MP, Galwey NW, Colmer TD. 2002. Similarity and diversity in adventitious root anatomy as related to root aeration among a range of wetland and dryland grass species. Plant, Cell and Environment 25: 441–451. [Google Scholar]

- Mendiburu F. 2014. Agricolae: statistical procedures for agricultural research. R package version 1.1–8 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=agricolae (October 2017).

- Miles JW, Do Valle CB, Rao IM, Euclides VPB. 2004. Brachiaria grasses. In: Moser LE, Burson LE, Sollenberger LE, eds Warm season (C4) grasses. Agronomy Monograph, American Society of Agronomy, no. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Lambers H, Poorter H. 1992. Inherent variation in growth rate between higher plants: a search for physiological causes and ecological consequences. Advances in Ecological Research 23: 187–261. [Google Scholar]

- Lux A, Morita S, Abe J, Ito K. 2005. An improved method for clearing and staining free-hand sections and whole-mount samples. Annals of Botany 96: 989–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JP, Brown KM. 2008. Root strategies for phosphorus acquisition. In: White PF, Hammond JP, eds. The ecophysiology of plant-phosphorus interactions. Springer Science + Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Pang JY, Newman I, Mendham N, Zhou M, Shabala S. 2006. Microelectrode ion and O2 fluxes measurements reveal differential sensitivity of barley root tissues to hypoxia. Plant, Cell and Environment 29: 1107–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postma JA, Lynch JP. 2011. Root cortical aerenchyma enhances the growth of maize on soils with suboptimal availability of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Plant Physiology 156: 1190–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao IM, Zeigler RS, Vera R, Sarkarung S. 1993. Selection and breeding for acid-soil tolerance in crops. BioScience 43: 454–465. [Google Scholar]

- Rao IM, Kerridge PC, Macedo MCM. 1998. Requerimientos nutricionales y adaptación a los suelos ácidos de especies de Brachiaria. In: Miles JW, Maass BL, do Valle CB, eds. Brachiaria: biology, agronomy and breeding. Cali: CIAT, 58–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rao I, Miles JW, García R, Ricaurte J. 2006. Selección de híbridos de Brachiaria con resistencia a aluminio. Pasturas Tropicales 28: 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin I. 1983. A method for measuring leaf volume, density, thickness, and internal gas volume. American Society for Horticultural Science 18: 698–699. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas JG, Saif SR. 1989. Requerimientos nutricionales de Andropogon gayanus. In: Toledo JM, Vera RR, Lascano CE, Lenné JM, eds. Andropogon gayanus Kunth: un pasto para los suelos ácidos del trópico. Cali: CIAT, 105–165. [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S. 2011. Physiological and cellular aspects of phytotoxicity tolerance in plants: the role of membrane transporters and implications for crop breeding for waterlogging tolerance. New Phytologist 190: 289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S, Shabala L, Barcelo J, Poschenrieder C. 2014. Membrane transporters mediating root signalling and adaptive responses to oxygen deprivation and soil flooding. Plant, Cell and Environment 37: 2216–2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smethurst CF, Garnett T, Shabala S. 2005. Nutritional and chlorophyll fluorescence responses of lucerne (Medicago sativa) to waterlogging and subsequent recovery. Plant and Soil 270: 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson CJ, Armstrong W, Waters I, Greenway H. 1990. Aerenchyma formation and associated oxygen movement in seminal and nodal roots of wheat. Plant, Cell and Environment 13: 395–403. [Google Scholar]

- Trought MCT, Drew MC. 1980a The development of waterlogging damage in wheat seedlings (Triticum aestivum L.) I. Shoot and root growth in relation to changes in the concentrations of dissolved gases and solutes in the soil solution. Plant and Soil 54: 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Trought MCT, Drew MC. 1980b The development of waterlogging damage in young wheat plants in anaerobic solution cultures. Journal of Experimental Botany 31: 1573–1585. [Google Scholar]

- Torres González AM, Morton CM. 2005. Molecular and morphological phylogenetic analysis of Brachiaria and Urochloa (Poaceae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 37: 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uexküll HR, Mutert E. 1995. Global extent, development and economic impact of acid soils. Plant and Soil 171: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich J. 1955. Vergleichende Untersuchungen über Verholzung und Verholzungsreaktionen. Berichte Deutschen Botanischen Gesellschaft 68: 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Visser EJW, Bogemann GM, Blom CWPM, Voesenek LACJ. 1996. Ethylene accumulation in waterlogged Rumex plants promotes formation of adventitious roots. Journal of Experimental Botany 47: 403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Visser EJW, Colmer TD, Blom CWPM, Voesenek LACJ. 2000. Changes in growth, porosity, and radial oxygen loss from adventitious roots of selected mono- and dicotyledonous wetland species with contrasting types of aerenchyma. Plant, Cell and Environment 23: 1237–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzl P, Mancilla LI, Mayer JE, Albert R, Rao IM. 2003. Simulating infertile acid soils with nutrient solutions: the effects on Brachiaria species. Soil Science Society of America Journal 67: 1457–1469. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzl P, Arango A, Chaves AL, et al. 2006. A greenhouse method to screen brachiariagrass genotypes for aluminum resistance and root vigor. Crop Science 46: 968–973. [Google Scholar]

- Wiengweera A, Greenway H. 2004. Performance of seminal and nodal roots of wheat in stagnant solution: K+ and P uptake and effects of increasing O2 partial pressures around the shoot on nodal root elongation. Journal of Experimental Botany 55: 2121–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiengweera A, Greenway H, Thomson CJ. 1997. The use of agar nutrient solution to simulate lack of convection in waterlogged soils. Annals of Botany 80: 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Ren B, Li F. 2009. Increased nutrient supply facilitates acclimation to high-water level in the marsh plant Deyeuxia angustifolia: the response of root morphology. Aquatic Botany 91: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi T, Colmer TD, Pedersen O, Nakazono M. 2018. Regulation of root traits for internal aeration and tolerance to soil waterlogging-flooding stress. Plant Physiology 176: 1118–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zech W, Senesi N, Guggenberger G, et al. 1997. Factors controlling humification and mineralization of soil organic matter in the tropics. Geoderma 79: 117–161. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.