Abstract

Background and Aims

Although hypernodulating phenotype mutants of legumes, such as soybean, possess a high leaf N content, the large number of root nodules decreases carbohydrate availability for plant growth and seed yield. In addition, under conditions of high air vapour pressure deficit (VPD), hypernodulating plants show a limited capacity to replace water losses through transpiration, resulting in stomatal closure, and therefore decreased net photosynthetic rates. Here, we used hypernodulating (nod4) (282.33 ± 28.56 nodules per plant) and non-nodulating (nod139) (0 nodules per plant) soybean mutant lines to determine explicitly whether a large number of nodules reduces root hydraulic capacity, resulting in decreased stomatal conductance and net photosynthetic rates under high air VPD conditions.

Methods

Plants were either inoculated or not inoculated with Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens (strain BR 85, SEMIA 5080) to induce nitrogen-fixing root nodules (where possible). Absolute root conductance and root conductivity, plant growth, leaf water potential, gas exchange, chlorophyll a fluorescence, leaf ‘greenness’ [Soil Plant Analysis Development (SPAD) reading] and nitrogen content were measured 37 days after sowing.

Key Results

Besides the reduced growth of hypernodulating soybean mutant nod4, such plants showed decreased root capacity to supply leaf water demand as a consequence of their reduced root dry mass and root volume, which resulted in limited absolute root conductance and root conductivity normalized by leaf area. Thereby, reduced leaf water potential at 1300 h was observed, which contributed to depression of photosynthesis at midday associated with both stomatal and non-stomatal limitations.

Conclusions

Hypernodulated plants were more vulnerable to VPD increases due to their limited root-to-shoot water transport capacity. However, greater CO2 uptake caused by the high N content can be partly compensated by the stomatal limitation imposed by increased VPD conditions.

Keywords: Legume, nitrogen content, nodules, root efficiency, water demand, water flow

INTRODUCTION

The successful colonization of terrestrial environments by plants depended on robust and efficient root systems for water uptake, a resistant xylem tissue for long-term transport, as well as a dynamic stomatal behaviour for tight regulation of gas exchange (Boyce, 2005; Kenrick and Strullu-Derrien, 2014; Brodribb and McAdam, 2017).

Overall, there is a tendency towards considerably greater water loss rate (in a 100: 1 ratio) in relation to CO2 uptake rate (Nobel, 2009). Thereby, constantly changing environmental growth conditions result in a two-fold problem. On one hand, stomatal opening is needed for CO2 uptake, which boosts photosynthesis, whereas plants need to optimize stomatal aperture control to reduce water loss. Moreover, plants need an efficient water uptake and transport system to replace water lost through transpiration. Nevertheless, due to increased vapour pressure deficit (VPD) associated with high irradiance levels, many plant species are unable to supply leaf water demand fully, leading to so-called ‘photosynthesis depression’, namely a steep drop in photosynthesis rates due to both stomatal and non-stomatal limitations at midday (Pathre et al., 1998; Brodribb and Holbrook, 2004; Adachi et al., 2010; Brodribb et al., 2015; Gu et al., 2017a).

The plant water transport system includes both anatomical traits and the network assembly of the xylem, which govern the size and architecture of the root system as well as the physical limits of water flow within plants and, therefore, dictate accessibility to underground water for transport (Brodribb et al., 2015). Although morphology, anatomy and aquaporin activity of the root system are crucial in determining its efficiency, root size dictates the effective volume of soil that can be explored by plants (Comas et al., 2013; Brodribb et al., 2015).

Nitrogen (N) is another key component of plant growth and yield, because it is essential for the synthesis of important molecules, such as chlorophylls, proteins, nucleic acids, metabolites and various enzymatic cofactors (Lawlor, 2002; Tegeder and Masclaux-Daubresse, 2017). Legume plants include many important crop species, such as soybean, peanuts, beans and medics, which have the capacity to establish an effective symbiosis with nitrogen-fixing microorganisms. Such associations are economically and environmentally important because they can help to reduce the use of mineral fertilizers, and hence decrease greenhouse gas emissions (Graham and Vance, 2003; Lambers et al., 2008; Peoples et al., 2009; Biswas and Gresshoff, 2014; Nemenzo-Calica et al., 2016).

The most widely known association between nitrogen-fixing organisms and vascular plants involves soil bacteria of the family Rhizobiaceae (i.e. Allorhizobium, Azorhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, Mesorhizobium, Rhizobium, Sinorhizobium), also known as rhizobia (Ferguson et al., 2013). Such microorganisms use an enzyme complex termed nitrogenase to reduce atmospheric N2 into a nitrogen form (i.e. ammonia) that plants can utilize (Ferguson et al., 2010). The rhizobia invade the roots of compatible legume plants and develop specialized root structures called nodules, where nitrogen fixation occurs (Corby, 1971; Mathews et al., 1989; Mortier et al., 2012; Gresshoff et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015; Ferguson et al., 2019).

Symbiotic N2-fixing microorganisms are effective carbon and energy sinks (Song et al., 1995; Sulieman, 2011; Mortier et al., 2012; Santi et al., 2013). To regulate this economically and environmentally important symbiosis, legumes evolved a systemic signalling mechanism called ‘autoregulation of nodulation’ (AON) to control nodule numbers (Caetano-Anollés and Gresshoff, 1991; Ferguson et al., 2019). The AON pathway begins in response to the initial rhizobia infection events, with the production of CLAVATA3/endosperm surrounding region‐related (CLE) peptides. In soybean, these peptides are GmRIC1 and GmRIC2 (Reid et al., 2011). The AON CLE peptides are produced in the roots, post-translationally modified (Corcilius et al., 2017; Hastwell et al., 2018) and transported to the shoot where they are detected by a leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase, termed GmNARK in soybean. CLV2/SYM29 and KLAVIER are suggested to form a heterodimeric complex with NARK to detect the CLE peptides, with mutations in either NARK or its dimerization partners resulting in hypernodulation (see Ferguson et al., 2019; Hastwell et al., 2018). Therefore, mutants displaying a hypernodulating phenotype, caused by genetic alterations of the AON circuit, can produce high N availability, while a large fraction of the carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis is allocated to supply the nutritional requirements of rhizobia, negatively affecting growth and yield of the host plants. In fact, it has been observed that hypernodulating soybean plants have reduced root biomass, while yield is unaffected (Streeter, 1980; Song et al., 1995). Furthermore, under increased atmospheric water demand (i.e. high air VPD), hypernodulating plants could show a limited capacity to replace water loss through transpiration, resulting in stomatal closure, and hence decreased photosynthetic rates. Under such conditions, the competition for carbohydrates between the host plant and nodules can be exacerbated, leading to further decreases in plant growth and seed yield.

We hypothesized that hypernodulating soybean mutants show limited root system capacity to meet leaf water demand under high air VPD conditions due to reduced root system size, which results in both depression of photosynthesis at midday and decreased plant growth. Thus, we undertook an investigation using hypernodulating (nod4) and non-nodulating (nod139) soybean mutant lines to answer the following questions: (i1) Do hypernodulating soybean plants have reduced root biomass? (2) Do hypernodulating soybean plants show decreased absolute root hydraulic conductance and root hydraulic conductivity? (3) How does hypernodulation in soybean plants affect leaf gas exchange and growth?

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Plant material, growth conditions and inoculation

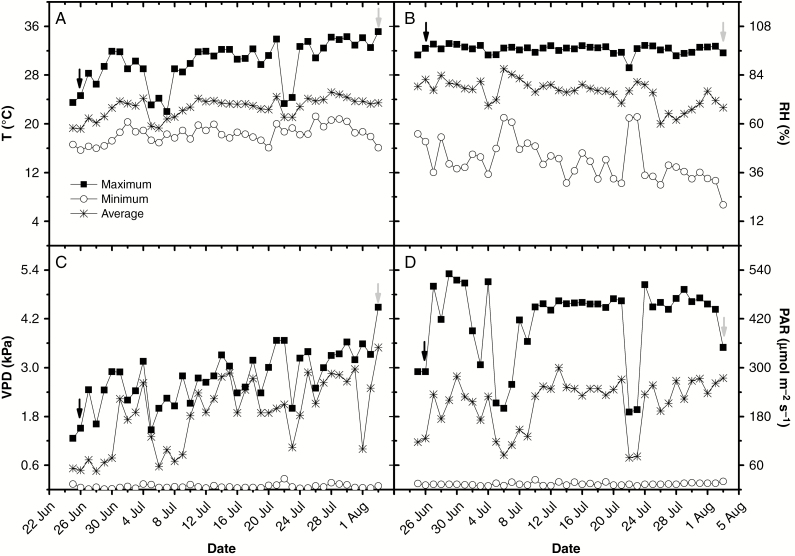

Soybean mutants nod4 (hypernodulation, GmNARK minus; Reid et al., 2011) and nod139 genotype (no nodulation; GmNFR5 minus; Indrasumunar et al., 2010) were grown under a greenhouse (50 % solar light interception) in 0.28-L pots containing commercial substrate (Basaplant) without N (see Supplementary Data Table S1). Micrometeorological variables [i.e. photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), air temperature and relative humidity inside the greenhouse] were monitored using Watchdog data loggers (Spectrum Technologies, USA). Maximum PAR was 500 µmol m−2 s−1 between 1200 and 1400 h, while maximum, minimum and average temperatures were 35, 15 and 25 °C, respectively. Maximum, minimum and average relative humidity were 100, 20 and 60 %, respectively. Regarding VPD, the maximum, minimum and average values of VPD were 4.5, 0.5 and 2.5 kPa, respectively (Fig. 1). Plants were watered to field capacity twice a day.

Fig. 1.

Daily air temperature – T (A), relative humidity – RH (B), air vapour pressure deficit – VPD (C) and photosynthetically active radiation – PAR (D):maximum, minimum and average values throughout the experiment. Arrows indicate sowing (black) and measurement (grey) days.

Soybean seeds were either inoculated (nod4 inoc and nod139 inoc) or non-inoculated (control – nod4 ctr and nod139 ctr) with Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens (strain BR 85, SEMIA 5080, see Araujo et al., 2018) obtained from the Embrapa Agroecologia collection. Soybean seeds were sterilized in 92 % ethanol for 3 min, treated with 5 % sodium hypochlorite for 5 min and then washed ten times with distilled water. Thereafter, seeds were inoculated using 100 g inoculum per 50 kg of soybean seeds. Thirty-seven days after sowing, six plants from each treatment were used to measure absolute root hydraulic conductance and conductivity, gas exchange, chlorophyll a fluorescence, growth traits, leaf water potential, leaf ‘greenness’ [Soil Plant Analysis Development (SPAD) reading] and nitrogen content, as described below.

Root nodule number

Thirty-seven days after sowing, the number of nodules was visually determined. Thereafter, nodules were dried in a forced-air ventilation oven at 70 °C for 72 h and weighed to determine nodule dry mass.

Root hydraulic conductance (absolute) and conductivity

Absolute root hydraulic conductance (K) was measured by pressurizing the roots using a Scholander chamber (Jackson et al., 1996). For this, plants had their shoots removed under water to avoid embolism, leaving about 5 cm of the basal stem. The root system was immersed in a bowl containing water, which was placed into the Scholander chamber. To obtain root conductance, an initial pressure of 0.05 MPa was applied for 60 s to the entire root system to both stabilize water flow and remove remaining gas bubbles from the xylem. Thereafter, the pressure was gradually increased (0.1, 0.2, 0.3 and 0.4 MPa) every 4 min. In the Scholander chamber, it was assumed that there was a balance between the negative pressure in the xylem and the pressure that forced water from the cells to xylem vessels. Sap obtained at each pressure was collected and weighed on a precision balance (±0.001-g precision). Sap flow was expressed in kilograms of water and plotted against the pressures applied (MPa), so that the slope of the curve was the K value (kg H2O s−1 MPa−1) (see Supplementary Data Fig. S1). Absolute root conductance was normalized by root dry mass (KRM), leaf area (KLA) and root volume (KRV) to obtain root hydraulic conductivity (Becker et al., 1999). Absolute root hydraulic conductance and root conductivity variables were measured on three consecutive days (eight plants per day – two plants of each treatment). Plants were maintained for 1 h in a climate-controlled room (25 °C, 65 % humidity and 300 µmol m−2 s−1) before starting the measurements. These procedures were required to avoid large fluctuations in root conductivity during the measurements (Henzler et al., 1999).

Gas exchange and leaf water potential measurements

Net photosynthetic rates (A), stomatal conductance (gs), intracellular CO2 concentration (Ci), transpiration rates (E), leaf-to-air VPD (VPDair-leaf) and leaf temperature were measured at both 0800 and 1300 h using a Li-Cor 6400XT portable photosynthesis system (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NB, USA). The system incorporated a CO2 controller which was used to set the CO2 concentration inside the Li-Cor cuvette at 400 μL L−1. The 6-cm2 cuvette was fitted with a red–blue light source (6400-02B) so that PAR was maintained at 1000 μmol m−2 s−1 for all measurements. The Li-Cor cuvette block temperature was similar to air temperature to account for the influence of leaf temperature on gas exchange variables. In addition, the flow rate was kept at 300 μmol m−2 s−1. Gas exchange measurements were performed on six plants per treatment, on the central leaflet of the 3rd leaf (fully expanded) below the plant apex.

Leaf water potential (Ψleaf) was measured immediately after leaf excision at 1300 h using a pressure chamber (Model 1000, PMS Instrument Co., Albany, OR, USA), according to Schölander et al. (1965). Measurements were performed on the same leaves used for the gas-exchange and chlorophyll a fluorescence measurements as described below.

Chlorophyll a fluorescence parameters

Photochemical efficiency was assessed from chlorophyll a fluorescence using a Pocket PEA chlorophyll fluorimeter (Hansatech, King’s Lynn, UK). Instant light fluorescence response curves were measured on the same attached leaflets used for the gas exchange measurements, using a non-modulated plant efficiency analyser fluorometer (Pocket PEA, Plant Efficiency Analyzer, Hansatech). The sensor unit consisted of an array of ultra-bright red LEDs optically filtered to a peak wavelength of 650 nm, which is readily absorbed by the leaf chloroplasts, with a maximum intensity of 3500 μmol m−2 s−1 at the sample surface. The LEDs are focused via lenses onto the leaf surface to provide uniform illumination over the area of leaf exposed by the leaf clip (4 mm diameter). The leaflets were dark-adapted for 30 min to turn the reaction centres into an ‘open’ (oxidized Quinone A) status (Bolhár-Nordenkampf et al., 1989). After dark-adaptation for 30 min, and an increase in actinic light, some key chlorophyll a fluorescence parameters were obtained: Fv/Fm, a parameter widely used to indicate the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II; Fv/Fo, the proportionality of the water oxidation activity on the donor side of photosystem II; and photosynthetic performance index (PI), which represents the energy cascade processes from the first absorption events until the reduction of plastoquinone (Strasser et al., 2004).

Growth analysis

Thirty-seven days after sowing, leaf area was measured using a leaf-area meter (Li-3100, Li-Cor) and plant height was determined for six plants. Thereafter, total root volume was estimated by immersing the roots in a 2-L graduated cylinder containing a known volume of distilled water and measuring the volume of water displaced after root-system immersion in the water. Shoots and roots were then placed in separate paper bags, labelled and dried in a forced-air ventilation oven at 70 °C for 72 h. Subsequently, root, stem, leaf and dry mass were determined. Plant total dry mass was then calculated (root dry mass + stem dry mass + leaf dry mass).

N content and SPAD readings

Dried leaves were weighed and then ground in a Wiley mill with 20 mesh sieve (Thomas Wiley Mini-Mill Cutting Mill, Swedesboro, NJ, USA). The ground material was solubilized to determine N content according to the Kjeldahl semi-micro method (Malavolta et al., 1997). SPAD readings were measured on the same intact leaflets used for gas-exchange and chlorophyll a fluorescence measurements and on the same days, between 0800 and 1000 h. Six SPAD readings were averaged in the same sampled leaflet using a Minolta SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter (Minolta Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

A completely randomized design with six replicates was used. Measured and calculated parameters were analysed using a one-way ANOVA (P ≤ 0.05), followed by the Tukey test for mean comparisons. Gas exchange parameters were analysed using a two-way ANOVA at P = 0.05 to evaluate differences between treatments and times (hours), followed by the Tukey test for comparisons of means between times for each treatment or between treatments for each time. A 95 % confidence level was used for all tests. Phenotypic correlations among the variables were also estimated using R software (R Core Team, 2016). Differences between photosynthetic rates and stomatal conductance values obtained at 0800 and 1300 h (designated as ΔA and Δgs, respectively) were calculated for phenotypic correlation analyses.

RESULTS

Number of nodules

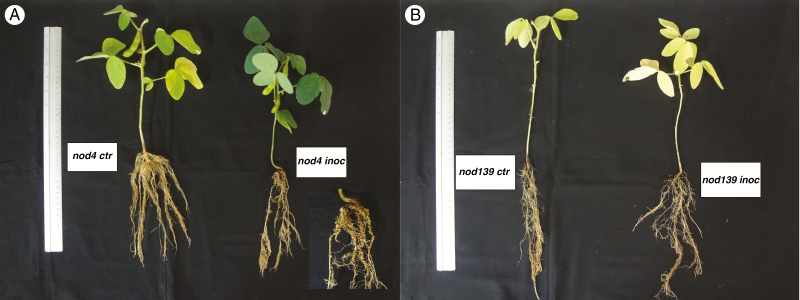

The nod4 inoc plants had an average number of 282.33 ± 28.59 nodules, which weighed 0.16 ± 0.03 g (dry weight). Nodules were not found in the other treatments (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Nodule number and dry mass in hypernodulating (nod4) and non-nodulating (nod139) soybean mutant lines either inoculated (nod4 inoc and nod139 inoc) with Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens (strain BR 85, SEMIA 5080) or non-inoculated (control – nod4 ctr and nod139 ctr)

| Treatment | Number of nodules | Nodule dry mass (g) |

|---|---|---|

| nod139 ctr | 0 | – |

| nod139 inoc | 0 | – |

| nod4 ctr | 0 | – |

| nod4 inoc | 282.33 ± 28.56 | 0.16 ± 0.03 |

Values are mean ± s.e. (n = 6).

Fig. 2.

Hypernodulating (nod4, A) and non-nodulating (nod139, B) soybean mutant lines either inoculated (nod4 inoc and nod139 inoc) with Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens (strain BR 85, SEMIA 5080) or non-inoculated (control – nod4 ctr and nod139 ctr). Below (left side) is an overview of the root system of nod4 inoc mutant, highlighting the high number of nodules on the proximal root zone.

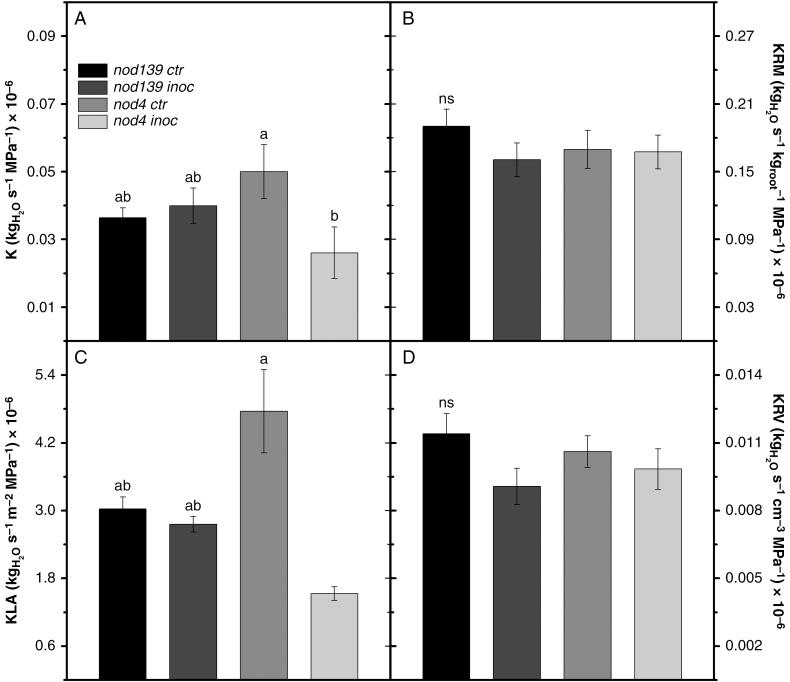

Root hydraulic conductance (absolute) and conductivity

Hypernodulation (nod4 inoc plants) reduced absolute root hydraulic conductance (K) compared to the non-inoculated control (~52 %, Fig. 3A). Non-significant trends for both increased and decreased K values in nod139 (control and inoculated) compared to nod4 ctr and nod4 inoc, respectively, were observed (Fig. 3A). The nod139 treatments showed similar K values. Similarly, normalization of the absolute root conductance resulted in reduced KLA in nod4 inoc compared to their non-inoculated counterparts (~61 % lower, Fig. 3C), without significant differences between nod139 treatments and nod4 ctr (Fig. 3C). On the other hand, normalization of absolute root hydraulic conductance (i.e. root hydraulic conductivity) resulted in similar values for KRM (Fig. 3B) and for KRV (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Root conductance – K (A) and K parameterized by root dry mass – KRM (B), leaf area – KLA (C) and root volume – KRV (D) in hypernodulating (nod4) and non-nodulating (nod139) soybean mutant lines either inoculated (nod4 inoc and nod139 inoc) with Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens (strain BR 85, SEMIA 5080) or non-inoculated (control – nod4 ctr and nod139 ctr). Values are mean ± s.e. (n = 6); means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey test at P = 0.05; ns, no significant difference.

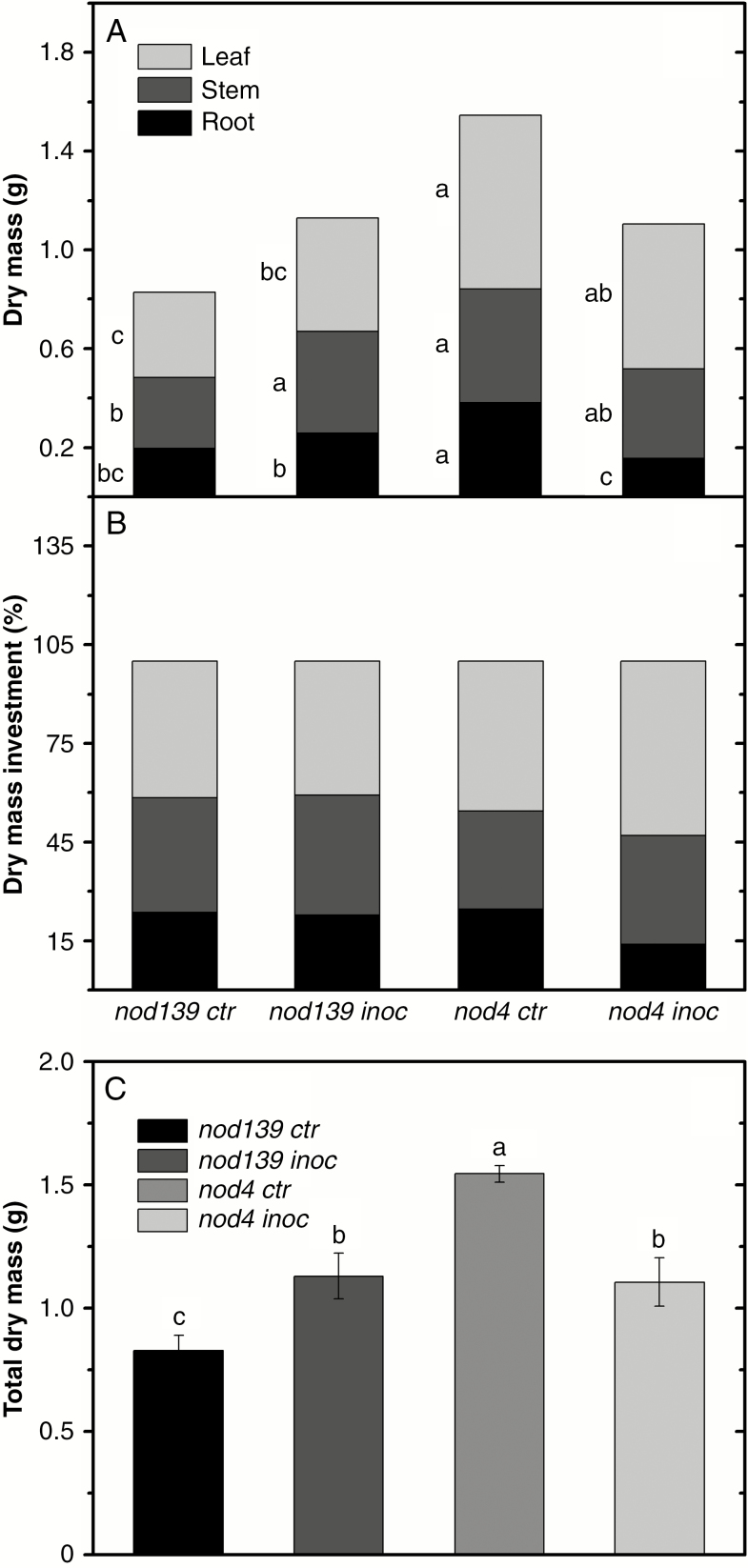

Growth traits

The nod4 inoc plants had the smallest root dry mass value, which was about 21, 48 and 59 % of that of nod139 ctr, nod139 inoc and nod4 ctr plants, respectively (Fig. 4A). On the other hand, nod139 ctr had lower stem mass than nod139 inoc (~29 %) and nod4 ctr (~36 %) plants, but similar stem mass to nod4 inoc plants (Fig. 4A). The nod4 ctr plants had greater leaf mass than the nod139 plants (i.e. 71 % and 53 % more than control and inoculated plants, respectively), as well as a non-significant trend towards greater leaf mass than nod4 inoc plants (17 %, Fig. 4A). The nod4 inoc plants had less biomass allocation to the roots (only 13 % of the total plant biomass), while other treatments showed root mass investments of between 22 % and 24 % of total plant biomass (Fig. 4B). However, nod4 inoc plants had greater biomass allocation to the leaves (investment of 52 % of the total plant biomass), while nod4 ctr had less biomass allocation to the stem (investment of 29 %, Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Biomass partitioning (A), dry mass investment (B) and total dry mass (C) in hypernodulating (nod4) and non-nodulating (nod139) soybean mutant lines either inoculated (nod4 inoc and nod139 inoc) with Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens (strain BR 85, SEMIA 5080) or non-inoculated (control – nod4 ctr and nod139 ctr). Values are mean ± s.e. (n = 6); means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey test at P = 0.05.

The nod4 ctr plants had greater total dry mass than nod139 ctr, nod139 inoc and nod4 inoc plants (34 %, 28 % and 28 %, respectively) (Fig. 4C). The two inoculated treatments had similar total dry mass, which were greater than nod139 ctr plants (Fig. 4C).

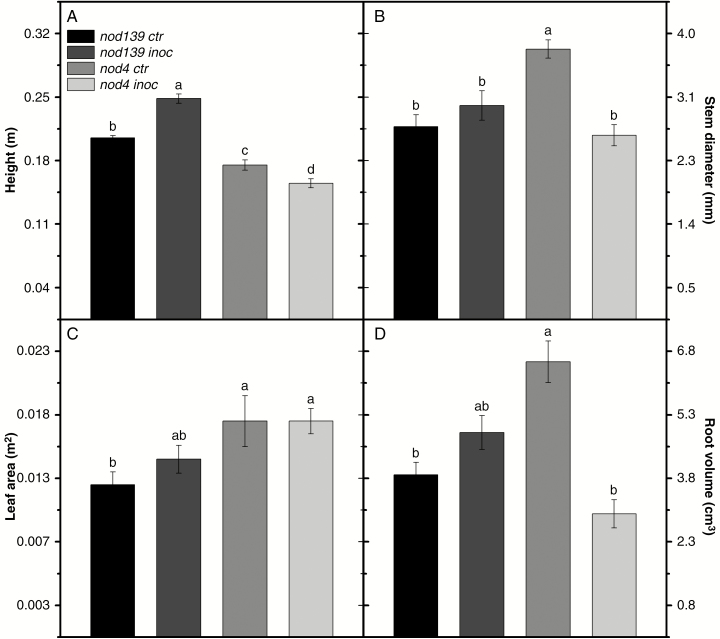

The nod139 inoc plants were the tallest followed by nod139 ctr, nod4 crt and nod4 inoc plants (the last was the shortest; Fig. 5A). On the other hand, nod4 ctr plants had greater stem diameter than nod139 ctr, nod139 inoc and nod4 ctr plants (40 %, 26 % and 47 %, respectively), without significant differences among other treatments (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Plant height (A), stem diameter (B), leaf area (C) and root volume (D) in hypernodulating (nod4) and non-nodulating (nod139) soybean mutant lines either inoculated (nod4 inoc and nod139 inoc) with Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens (strain BR 85, SEMIA 5080) or non-inoculated (control – nod4 ctr and nod139 ctr). Values are mean ± s.e. (n = 6); means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey test at P = 0.05.

Both nod4 treatments had greater leaf area than nod139 ctr plants, as well as non-significant trends towards greater leaf areas than nod139 inoc plants, which, in turn, had greater leaf areas than their respective non-inoculated treatments (nod139 ctr plants) (Fig. 5C). The nod4 ctr plants had greater root volume than nod139 ctr and nod4 inoc plants (70 % and 123 %, respectively), and a non-significant trend of greater root volume than nod139 inoc plants (34 %, Fig. 5D). The nod139 inoc plants had a non-significant trend for greater root volume than nod139 ctr and nod4 inoc plants (Fig. 5D).

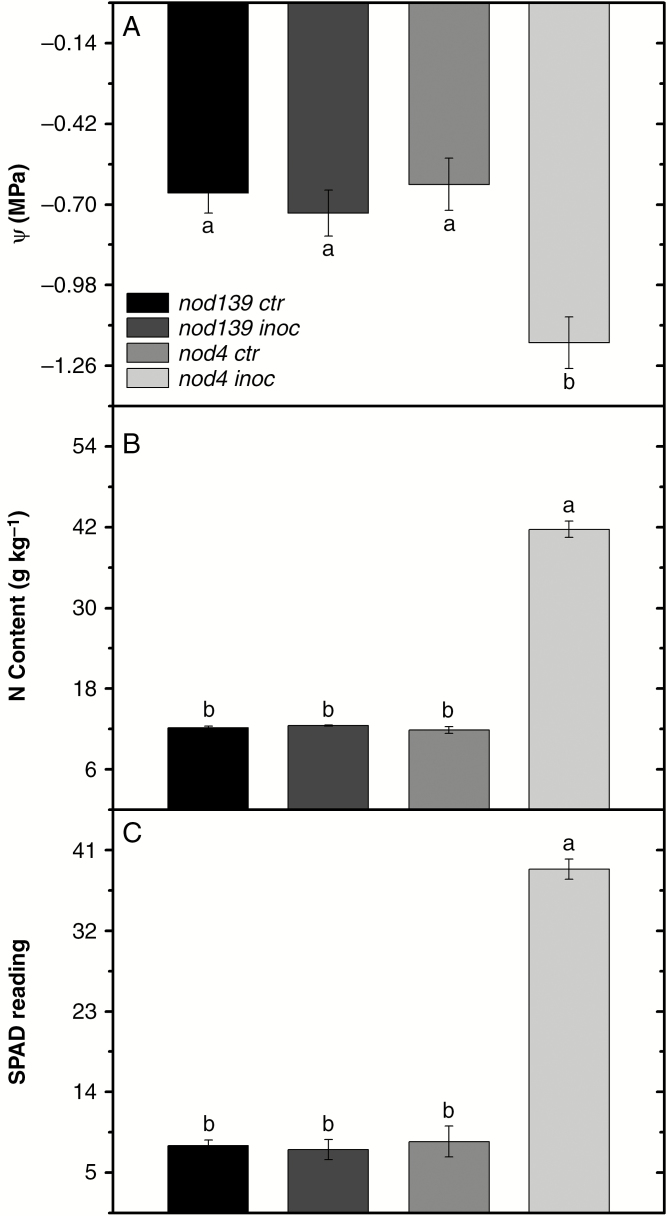

Ψw, N content and SPAD readings

Hypernodulation (nod4 inoc plants) showed decreased leaf Ψw at 1300 h in relation to nod139 ctr (78 %), nod139 inoc (61 %) and nod4 ctr (90 %) plants (Fig. 6A). The nod4 inoc plants had greater N content and higher SPAD readings than the other treatments (240 % and 400 %, respectively; Fig. 6B, C).

Fig. 6.

Leaf water potential - Ψleaf (A), nitrogen content (B) and SPAD reading (C) in hypernodulating (nod4) and non-nodulating (nod139) soybean mutant lines either inoculated (nod4 inoc and nod139 inoc) with Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens (strain BR 85, SEMIA 5080) or non-inoculated (control – nod4 ctr and nod139 ctr). Values are mean ± s.e. (n = 6); means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey test at P = 0.05.

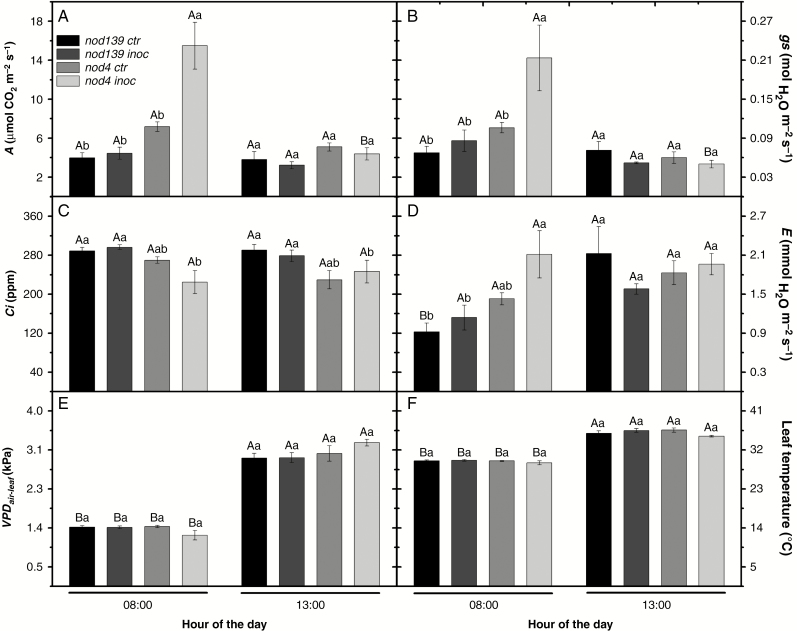

Gas exchange parameters

The nod4 inoc plants had greater photosynthetic rates at 0800 h (15.49 µmol CO2 m−2 s−1) than the nod139 treatments (290 % and 248 % higher than ‘control’ and ‘inoculated’ plants, respectively) and nod4 ctr plants (115 % higher) (Fig. 7A). However, gas exchange traits of nod4 inoc plants were greatly reduced at 1300 h (252 %), whereas other treatments had similar A values at 1300 h to those at 0800 h (Fig. 7A). There were no significant differences among treatments at 1300 h. Stomata conductance (gs) values followed a similar pattern observed for A (Fig. 7B). At 0800 h, the nod4 inoc plants had greater gs than nod4 ctr plants (530 %) and both nod139 treatments (413 % and 208 % in relation to ‘control’ and ‘inoculated’ plants, respectively). However, gs was greatly reduced in nod4 inoc plants at 1300 h than at 0800 h (770 %). No significant differences among treatments were observed at 1300 h (Fig. 7B). The nod4 inoc plants had lower Ci values than both nod139 treatments at both time points (Fig. 7C) Nonetheless both nod4 inoc and nod139 inoc had similar Ci values than the respective non-inoculated treatments (Fig. 7C), while overall no significant differences were found between time periods for the same treatments. Regarding the transpiration rates, the nod4 inoc plants had greater E values than nod139 treatments (130 % and 84 % of ‘control’ and ‘inoculated’ plants, respectively), and a non-significant trend towards higher E values than nod4 ctr plants (47 % higher) at 0800 h (Fig. 7D). On the other hand, nod139 ctr plants had increased E values at 1300 h compared to at 0800 h (56 % higher), and similar non-significant trends were also observed in both nod139 inoc and nod4 ctr plants. However, nod4 inoc plants had similar E values at both time periods (Fig. 7D), although no significant differences among treatments were observed at 1300 h. Similar responses were observed for VPDair–leaf and leaf temperature (Fig. 7E, F), i.e. there were no significant differences among treatments at both times but the greatest values were observed at 1300 h. Increases of 130 % and 23 % were observed for VPDair–leaf and leaf temperature, respectively (Fig. 7E, F).

Fig. 7.

Variation in net photosynthesis rate – A (A), stomatal conductance – gs (B), intracellular [CO2] – Ci (C), transpiration rates – E (D), air-to-leaf vapour deficit pressure – VPDair-leaf (E) and leaf temperature (F) in hypernodulating (nod4) and non-nodulating (nod139) soybean mutant lines either inoculated (nod4 inoc and nod139 inoc) with Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens (strain BR 85, SEMIA 5080) or non-inoculated (control – nod4 ctr and nod139 ctr). Values are mean ± s.e. (n = 6); means followed by the same letter are not significantly different between times for the same treatment (upper case) or between treatments for the same time (lower case) according to Tukey test at P = 0.05. Environmental conditions at 0800 h and 1300 h were: photosynthetically active radiation,100 and 435 µmol m−2 s–1; air temperature, 21.6 and 32.2 °C; relative humidity, 70.2 and 26.7 %; and air vapour pressure deficit, 0.76 and 3.53 kPa, respectively.

Chlorophyll a fluorescence variables

No significant differences in Fv/Fm were found among treatments at 0800 h. However, nod4 inoc plants had the greatest Fv/Fm values at 1300 h (Table 2), which were similar to those at 0800 h. On the other hand, nod139 treatments and nod4 ctr plants had significant decreases in Fv/Fm (12 %) at 1300 h than at 0800 h (Table 2). Likewise, nod4 inoc plants had similar Fv/Fo between times and the greatest Fv/Fo at 1300 h, whereas the other treatments had significant reductions of around 40 % at 1300 h than at 0800 h (Table 2). In addition, although nod4 inoc plants had decreased PI at 1300 h (34 %), this treatment had the highest PI at both times (Table 2).

Table 2.

Photosystem II maximum quantum yield (Fv/Fm), proportionality of the water oxidation complex activity on the donor side of photosystem II (Fv/Fo) and photosynthetic index (PI) variables from chlorophyll a fluorescence measurements in hypernodulating (nod4) and non-nodulating (nod139) soybean mutant lines either inoculated (nod4 inoc and nod139 inoc) with Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens (strain BR 85, SEMIA 5080) or non-inoculated (control – nod4 ctr and nod139 ctr).

| Treatment | 0800 h | 1300 h |

|---|---|---|

| F v /F m | ||

| nod139 ctr | 0.80 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.72 ± 0.02 Bb |

| nod139 inoc | 0.81 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.72 ± 0.02 Bb |

| nod4 ctr | 0.82 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.72 ± 0.03 Bb |

| nod4 inoc | 0.84 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.81 ± 0.01 Aa |

| F v /F o | ||

| nod139 ctr | 4.17 ± 0.37 Aa | 2.57 ± 0.20 Bb |

| nod139 inoc | 4.43 ± 0.30 Aa | 2.69 ± 0.25 Bb |

| nod4 ctr | 4.72 ± 0.14 Aa | 2.74 ± 0.38 Bb |

| nod4 inoc | 5.21 ± .0.32 Aa | 4.49 ± 0.31 Aa |

| PI | ||

| nod139 ctr | 0.45 ± 0.09 Ab | 0.15 ± 0.04 Ab |

| nod139 inoc | 0.46 ± 0.09 Ab | 0.19 ± 0.04 Ab |

| nod4 ctr | 1.08 ± 0.28 Ab | 0.25 ± 0.10 Ab |

| nod4 inoc | 6.54 ± 0.73 Aa | 4.32 ± 0.83 Ba |

Values are mean ± s.e. (n = 6; means followed by the same letter are not significantly different between times for the same treatment (upper case) or between treatments for the same time (lower case) according to Tukey test at P = 0.05.

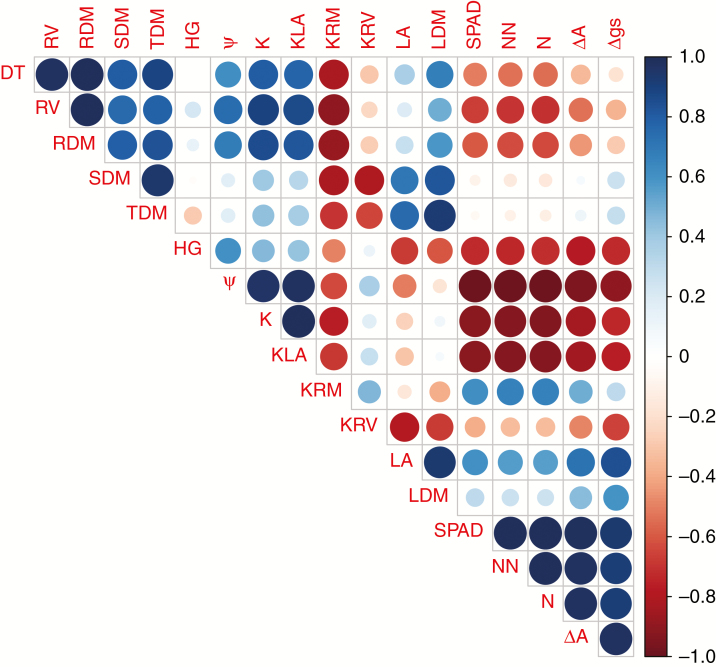

Phenotypic correlation factors

The number of nodules had strong negative correlations with Ψleaf (r2 = −0.98), K (r2 = −0.93) and KLA (r2 = −0.92), as well as negative correlations with plant height (r2 = −0.73), root volume (r2 = −0.70) and root dry mass (r2 = −0.63) (Fig. 8). On the other hand, the number of nodules had strong positive correlations with N content (r2 = 0.99), SPAD reading (r2 = 0.99), ΔA (r2 = 0.98) and Δgs (r2 = 0.91) (Fig. 8). Similarly, there was a strong positive correlation between N content and SPAD reading (r2 = 0.99). Root volume and root dry mass had high positive correlations with both K (r2 = 0.90 and 0.86, respectively) and KLA (r2 = 0.86 and 0.83, respectively) (Fig. 8). Similarly, Ψleaf had positive correlations with both root volume (r2 = 0.75) and root dry mass (r2 = 0.69), whereas Ψleaf had strong negative correlations with ΔA (r2 = −0.95) and Δgs (r2 = −0.89) (Fig. 8). K had negative correlations with N content (r2 = −0.93), SPAD reading (r2 = −0.92), ΔA (r2 = −0.83) and Δgs (r2 = −0.73). Finally, KLA had negative correlations with ΔA (r2 = −0.85) and Δgs (r2 = –0.77) as well as a strong positive correlation with Ψleaf (r2 = 0.97) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Estimates of phenotypic correlation among traits measured in hypernodulating (nod4) and non-nodulating (nod139) soybean mutant lines either inoculated with Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens (strain BR 85, SEMIA 5080) or non-inoculated (control). The traits assessed were root volume (RV), root dry mass (RDM), stem dry mass (SDM), total dry mass (TDM), plant height (HG), leaf water potential (Ψ), root conductance (K), K parameterized by leaf area, root dry mass and root volume (KLA, KRM and KRV, respectively), leaf area (LA), leaf dry mass (LDM), SPAD reading, number of nodules (NN), nitrogen content (N), and differences between photosynthetic rates and stomatal conductance values obtained at 0800 h and 1300 h (ΔA and Δgs, respectively). Areas of the circles show the value of corresponding Spearman correlation coefficients. Correlation values are presented in the upper panel in circles; positive correlations are displayed in blue and negative correlations in red. Colour intensity (light to dark) and the size of the circle (small to big) are proportional to the correlation coefficients (0 to 1 for the positive coefficient and 0 to −1 for the negative coefficient.

DISCUSSION

Nitrogen-fixing microorganisms play an essential role in both ecological and agricultural systems, providing cheaper and more efficient N supply for legume-based crops than mineral N fertilizers (Zahran, 1999; Biswas and Gresshoff, 2014; Silva Júnior et al., 2018). However, nodules are strong carbohydrate sinks, so that nodules can decrease sugar translocation to root cells, reducing root system growth (Streeter, 1980; Mortier et al., 2012; Ferguson et al., 2014, 2019). We initially hypothesized that hypernodulation (caused by the absence of AON) could greatly increase carbohydrate translocation to the nodules and therefore decrease translocation to the root system. As predicted, nod4 inoc plants had reduced root dry mass and root investment, as well as reduced root volume compared to the other treatments (Figs 4A, B and 5D), which was associated with a larger number of nodules (Table 1, Fig. 8).

Canopy photosynthetic performance depends on, among other things, an optimal balance between water loss through transpiration and water uptake and transport by the root system (Brodribb and Holbrook, 2004; Gu et al., 2017a). Although root size does not necessarily determine hydraulic efficiency, overall, large root systems exploit a larger soil volume, improving water supply to the shoot (Blum, 2011). Although hypernodulation (nod4 inoc treatment) apparently did not change hydraulic properties as observed by the similar root conductivity values normalized by root traits (i.e. KRM and KRV, Fig. 3B, D), a reduced root system associated with a large number of nodules in nod4 inoc plants decreased absolute root conductance (K, Figs 3A and 8). In addition, the roots’ capacity to balance leaf water demand was decreased due to low root hydraulic conductivity normalized by leaf area (KLA, Figs 3C and 8), which is further supported by the decreased root/shoot ratio (60 %) in this treatment (see Supplementary Data Fig. S2). Indeed, leaf area can serve as a useful way to normalize absolute root conductance, thereby providing an estimate of the efficiency of the roots to provide water to the leaves (Meinzer et al., 1995; Tyree et al., 1998). Interestingly, the highest number of nodules in nod4 inoc plants were located on the proximal root zone (Fig. 2), which is a region of less efficient water uptake due to its pronounced hydrophobicity (Zarebanadkouki et al., 2014, 2016). Therefore, the high number of nodules did not affect root hydraulic properties, i.e. KRM and KRV (Fig. 3).

Elevated atmospheric demand for water, i.e. increased air VPD, which is associated with high temperature and low relative humidity, can decrease leaf water status in response to limited water transport through the plant, resulting in stomatal closure, especially in isohydric species (McAdam and Brodribb, 2015; Gu et al., 2017b; Sinclair et al., 2017). Such stomatal closure limits CO2 uptake causing depression of photosynthesis at midday (Adachi et al., 2010; Brodribb et al., 2015; Gu et al., 2017a). Indeed, reduced root capacity (K and KLA, Fig. 3A, C) observed in nod4 inoc plants resulted in decreased Ψleaf when water demand (VPD) was highest (Figs 6A and 8), inducing a strong reduction of gs at 1300 h (Fig. 7B). In addition, ΔA and Δgs were positively correlated with Ψleaf (Fig. 8), indicating severe reductions in both A and gs at 1300 h in response to the decreased leaf water status. Note that a negative correlation between gs and Ψleaf has been reported for C3 plants (Kudoyarova et al., 2007), indicating that higher gs values at 0800 h in nod4 inoc plants could contribute to reduce Ψleaf at 1300 h. However, gs values were similar at 1300 h among treatments, with reduced Ψleaf further supporting the evidence for limited root-to-shoot water transport capacity in nod4 inoc plants.

Increased gs observed in nod4 inoc plants at 0800 h could be associated with reduced Ci values, as gs declines in response to increasing intracellular [CO2] (Messinger et al., 2006), which further explains the reduced gs values observed in the other treatments (Fig. 7B). The reduced Ci observed in nod4 inoc plants was associated with greater photosynthetic efficiency, which in turn increased CO2 uptake. Because intracellular [CO2] depends on both photosynthetic rates and stomatal conductance, decreased Ci values associated with stomatal closure in nod4 inoc plants was expected. However, Ci values were similar between times in all treatments, although a non-significant trend towards decreased Ci values was observed in nod139 inoc and nod4 ctr plants (Fig. 7C). Therefore, stomatal and non-stomatal limitations of photosynthesis were likely to occur especially in nod4 inoc plants. In fact, non-stomatal limitations have been suggested to occur in C3 plants at gs values close to 0.05 mol H2O m−2 s−1, without concomitant decreases in Ci, which may be associated with decreased Rubisco activity, as well as impaired ATP synthesis and, in turn, ATP-limited regeneration of RuBP (Flexas and Medrano, 2002).

Considerable variation in stomatal conductance in soybean genotypes has been reported under field conditions, with some genotypes reducing gs, while others did not show an apparent stomatal response under increased air VPD (Gilbert et al., 2011). Although gs decreased at 1300 h in nod139 inoc plants compared with at 0800 h, leaf transpiration rates were similar between times, whereas increased E occurred in nod139 ctr plants, as well as non-significant trends towards increased E in nod139 inoc and nod4 ctr plants (Fig. 7D). These responses correlate to both increases in PAR and decreases in gs, particularly in nod4 inoc plants (and non-significant trends in nod139 inoc and nod4 ctr plants), contributing to the elevated leaf temperature observed in all treatments (Fig. 7F). Together, these changes increased VPDair-leaf, which is the main driving force for plant transpiration (E = gs.VPDair-leaf) (Buckley, 2004; Nobel, 2009).

Treatments with low N content (e.g. nod139 ctr, nod139 inoc and nod4 ctr plants) had the lowest gs values (Figs 6B and 7B, respectively). In fact, reduced stomatal aperture has been reported in N-stressed plants, which can be associated with abscisic acid (ABA) metabolism (Radin et al., 1990). In addition, N deficiency can decrease root conductivity linked to both decreased amounts of aquaporins and its regulation by post-translational modifications (Ishikawa-Sakurai et al., 2014). Nevertheless, reduced K, KLA and gs were observed in nod4 inoc plants (greater N content) due to the direct effects of an elevated number of nodules on root capacity (Fig. 8).

The nod4 inoc plants showed higher N content, resulting in higher SPAD readings due to the strong positive correlation between these variables (Fig. 8), as previously reported by Torres-Netto et al. (2005). In addition, higher SPAD reading and N content indicate higher chlorophyll content (Torres-Netto et al., 2005; Croft et al., 2017). Therefore, higher leaf N content, and hence higher chlorophyll and levels of proteins involved in photosynthetic electron transport, will increase the efficiency of primary photochemistry reactions, as well as photosynthetic capacity (Evans, 1989; Torres-Netto et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2016; Croft et al., 2017). In fact, under low irradiance conditions (i.e. at 0800 h, 100 µmol m−2 s−1), N-deficient treatments (nod139 ctr and nod4 ctr plants) showed similar Fv/Fm and Fv/Fo to nod4 inoc plants (Table 2). However, increased irradiance (at 1300 h) resulted in reduced photochemical efficiency in the N-deficient treatments as observed through Fv/Fm and Fv/Fo (in nod139 ctr and nod4 ctr plants, Fv/Fm decreased 10 % and 12 %, and Fv/F0 decreased 38 % and 42 %, respectively). This was probably due to lower chlorophyll content as a consequence of the decreased N content and SPAD values (Fig. 6B, C). On the other hand, hypernodulation (nod4 inoc plants) decreased PI at 1300 h (34 %) (Table 2). PI combines three steps of photosynthetic activity of photosystem II: the contribution to PI of the active reactive centre density on a chlorophyll basis, the contribution to PI of the light reactions for primary photochemistry (Fv/Fo, i.e. performance due to trapping probability), and the contribution to PI of the dark reactions, i.e. performance due to electron-transport probability (Strasser et al., 2000, 2004; Thach et al., 2007). Thus, this variable is a highly sensitive parameter that has been used to quantify the effects of several types of stress on plant species (De Ronde et al., 2004). Therefore, nod4 inoc plants had higher photosynthetic rates at 0800 h, probably associated with a greater investment in both proteins involved in photosynthetic electron transport, as well as in Calvin cycle enzymes (especially Rubisco) due to greater N availability (Evans, 1989; Lawlor, 2002; Sun et al., 2016). However, in addition to stomatal limitations, decreased Ψleaf caused by hypernodulation at 1300 h resulted in non-stomatal limitations of photosynthesis associated with the photochemical pathway, as reflected by PI, which decreased by 34 % (Table 2).

Greater N availability provided by hypernodulation could result in increased growth in nod4 inoc plants, as biomass production depends on N to synthesize several molecules, such as chlorophylls and Rubisco, as well as proteins, nucleic acids and various enzymatic cofactors (Lawlor, 2002; Tegeder and Masclaux-Daubresse, 2017). However, the nod4 inoc plants had reduced total biomass associated with reduced height and stem diameter, as well as lower root volume and root dry mass than the respective non-inoculated treatments (Figs 4 and 5). Such responses were associated with a greater number of nodules, which are strong carbohydrate sinks, decreasing sugar translocation to the root cells (Streeter, 1980). Indeed, nitrogen fixation and the assimilation of ammonia requires large amounts of photosynthates to support the increased respiratory burden of nodulated roots and to provide the carbon skeletons required for the synthesis of the organic forms of nitrogen, which are exported from the nodule to the leaves and pods (Coker and Schubert, 1981). In many cases, these costs may represent 15–35 % of the total photosynthetic capacity of the host plant (Schubert and Ryle, 1980).

In addition, hypernodulation caused depression of photosynthesis at midday associated with reduced total root ability to provide water to evaporating tissues (Fig. 8). Interestingly, nod4 inoc plants showed similar leaf area values to nod4 ctr plants due to greater investment in this tissue (52 % of total biomass, Fig. 4B). Furthermore, Bradyrhizobium inoculation promoted changes in growth traits in a cultivar-dependent manner, as nod139 inoc plants tended to have higher growth traits and total dry mass values, whereas opposite patterns were observed in nod4 inoc plants (Figs 2 and 3). Therefore, because nodulation events were not found in nod139 inoc plants (Table 1, Fig. 2), other components in the inoculum rather than Bradyrhizobium or other biochemical functions of the Bradyrhizobium inoculum (such as phytohormome production) probably caused these responses in this treatment.

In summary, our results confirmed our initial hypothesis that hypernodulating soybean nod4 inoc mutants have a decreased root capacity to supply leaf water demand, as supported by the strong negative correlation between the number of nodules and K, KLA and Ψleaf (Fig. 8), although the root hydraulic conductivity normalized by root traits was not affected (e.g. KRM and KRV, Fig. 3B, D). Decreased root capacity is associated with a reduced root system as shown by decreased root dry mass and root volume, possibly due to greater sugar demand by the nodules, which are strong carbohydrate sinks (Coker and Schubert, 1981; Schubert and Ryle, 1980). Collectively, these responses resulted in depression of photosynthesis at midday, which can further exacerbate the competition for carbohydrates between nodules and root cells, reducing plant growth. However, photosynthetic rates among treatments at 1300 h were similar to that of other treatments, suggesting that the daily fixation rate could be higher due to the greater CO2 uptake during the morning. Therefore, although hypernodulated plants were more vulnerable to VPD increases, greater CO2 uptake caused by the high N content is partly compensated for by the stomatal limitation imposed by increased VPD conditions.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Table S1: Substrate composition used in the experiment. Fig. S1: Relationship between exudate flow and applied pressure for hypernodulating and non-nodulating soybean mutant lines either inoculated with Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens or non-inoculated. Fig. S2: Root-to-shoot ratios in hypernodulating and non-nodulating soybean mutant lines either inoculated with Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens or non-inoculated.

FUNDING

Funding for this research was provided through grants from CAPES to E.C.S.L. Funding from FAPERJ (grants E-26/202.323/2017, W.P.R.; E-26/202.759/2018, E.C.) and CNPq (fellowships awarded 300996/2016, E.C.) are also gratefully acknowledged.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Robert Michael Boddey and Dr Ana Paula Guimarães (Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation/Agrobiologia) for supplying Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens inoculants. We also thank Professor Richard Ian Samuels (Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense) for English-language review. The authors have no competing interests to declare. E.C.S.L., F.A.M.M.A.F. and E.C. designed the study. E.C.S.L., W.P.R., K.R.F., J.A.M.F., J.R.S. and F.A.M.M.A.F. performed the experiment. E.C.S.L., W.P.R., J.R.S., M.M.A.G. and E.C. analysed the data. W.P.R., J.R.S., M.M.A.G., P.M.G. and E.C. wrote the manuscript. All the authors revised the manuscript.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adachi S, Tsuru Y, Kondo M, et al. 2010. Characterization of a rice variety with high hydraulic conductance and identification of the chromosome region responsible using chromosome segment substitution lines. Annals of Botonay 106: 803–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo KEC, Vergara C, Guimarães AP, et al. 2018. Changes in 15N natural abundance of biologically fixed N2 in soybean due to shading, rhizobium strain and plant growth stage. Plant and Soil 426: 419–428. [Google Scholar]

- Becker P, Tyree MT, Tsuda M. 1999. Hydraulic conductances of angiosperms versus conifers: similar transport sufficiency at whole-plant level. Tree Physiology 19: 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas B, Gresshoff PM. 2014. The role of symbiotic nitrogen fixation in sustainable production of biofuels. International Journal of Molecular Science 15: 7380–7397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum A. 2011. Plant breeding for water-limited environments. London: Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce KC. 2005. The evolutionary history of roots and leaves. In: Holbrook NM, Zwieniecki MA, eds. Vascular transport in plants. San Diego: Elsevier, 479–500. [Google Scholar]

- Bolhár-Nordenkampf HR, Long SP, Baker NR, Oquist G, Schreibers U, Lecher EG. 1989. Chlorophyll fluorescence as a probe of the photosynthetic competence of leaves in the field: a review of current instrumentation. Functional Ecology 3: 497–514. [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb TJ, Holbrook NM. 2004. Diurnal depression of leaf hydraulic conductance in a tropical tree species. Plant, Cell and Environment 27: 820–827. [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb TJ, McAdam SAM. 2017. Evolution of the stomatal regulation of plant water content. Plant Physiology 174: 639–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb TM, Holloway-Phillips M-M, Bramley H. 2015. Improving water transport for carbon gain in crops. In: Sadras VO, Calderini D, eds. Crop physiology. Oxford: Academic Press, 251–281. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TN. 2004. The control of stomata by water balance. New Phytologist 168: 275–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano-Anollés G, Gresshoff PM. 1991. Plant genetic control of nodulation. Annual Review of Microbiology 45: 345–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas LH, Becker SR, Cruz VMV, Byrne PF, Dierig DA. 2013. Root traits contributing to plant productivity under drought. Frontiers in Plant Science 4: 442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker GT, Schubert KR. 1981. Carbon dioxide fixation in soybean roots and nodules. I. Characterization and comparison with N2 fixation and composition of xylem exudate during early nodule development. Plant Physiology 67: 691–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corby HDL. 1971. The shape of leguminous nodules and the color or leguminous roots. Plant and Soil 35: 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Corcilius L, Hastwell AH, Zhang MB, et al. 2017. Arabinosylation modulates the growth-regulating activity of the peptide hormone CLE40a from soybean. Cell Chemical Biology 24: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft H, Chen JM, Luo X, Bartlett P, Chen B, Staebler RM. 2017. Leaf chlorophyll content as a proxy for leaf photosynthetic capacity. Global Change Biology 23: 3513–3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ronde JA, Cress WA, Kuger GHJ, Strasser RJ, Van Staden J. 2004. Photosynthetic response of transgenic soybean plants, containing an Arabidopsis P5CR gene, during heat and drought stress. Journal of Plant Physiology 161: 1211–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. 1989. Photosynthesis and nitrogen relationships in leaves of C3 plants. Oecologia 78: 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson BJ, Indrasumunar A, Hayashi S, et al. 2010. Molecular analysis of legume nodule development and autoregulation. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 52: 61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson BJ, Lin M-H, Gresshoff PM. 2013. Regulation of legume nodulation by acidic growth conditions. Plant Signaling and Behavior 8: 234261–234265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson BJ, Li D, Hastwell AH, et al. 2014. The soybean (Glycine max) nodulation-suppressive CLE peptide, GmRIC1, functions interspecifically in common white bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), but not in a supernodulating line mutated in PvNARK. Plant Biotechnology Journal 12: 1085–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson BJ, Mens C, Hastwell AH, et al. 2019. Legume nodulation: the host controls the party. Plant Cell and Environment 42: 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Medrano H. 2002. Drought-inhibition of photosynthesis in C3 plants: stomatal and non-stomatal limitation revisited. Annals of Botany 89: 183–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert ME, Holbrook NM, Zwieniecki MA, Sadok W, Sinclair TR. 2011. Field confirmation of genetic variation in soybean transpiration response to vapor pressure deficit and photosynthetic compensation. Field Crop Research 124: 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Graham PH, Vance CP. 2003. Legumes: importance and constraints to greater use. Plant Physiology 131: 872–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresshoff PM, Hayashi S, Biswas B, et al. 2014. The value of biodiversity in legume symbiotic nitrogen fixation and nodulation for biofuel and food production. Joural of Plant Physiology 172: 128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Zhou Z, Li Z, et al. 2017. a Photosynthetic properties and potentials for improvement of photosynthesis in pale green leaf rice under high light conditions. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu D, Wang Q, Otieno D. 2017b Canopy transpiration and stomatal responses to prolonged drought by a dominant desert species in Central Asia. Water 9: 404. [Google Scholar]

- Hastwell AH, Corcilius L, Williams JT, Gresshoff PM, Payne RJ, Ferguson BJ. 2018. Triarabinosylation is required for nodulation‐suppressive CLE peptides to systemically inhibit nodulation in Pisum sativum. Plant Cell and Environment 42: 188–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henzler T, Waterhouse RN, Smyth AJ, et al. 1999. Diurnal variations in hydraulic conductivity and root pressure can be correlated with the expression of putative aquaporins in the roots of Lotus japonicas. Planta 210: 50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indrasumunar A, Kereszt A, Searle I, et al. 2010. Inactivation of duplicated Nod-Factor Receptor 5 (NFR5) genes in recessive loss-of-function nonnodulation mutants of allotetraploid soybean (Glycine max L Merr). Plant and Cell Physiology 51: 201–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa-Sakurai J, Hayashi H, Murai-Hatano M. 2014. Nitrogen availability affects hydraulic conductivity of rice roots, possibly through changes in aquaporin gene expression. Plant and Soil 379: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MB, Davies WJ, Else MA. 1996. Pressure-flow relationships, xylem solutes and root hydraulic conductance in flooded tomato plants. Annals of Botany 77: 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kudoyarova GR, Vysotskaya LB, Cherkozyanova A, Dodd IC. 2007. Effect of partial rootzone drying on the concentration of zeatin-type cytokinins in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L) xylem sap and leaves. Journal of Experimental Botany 58: 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenrick P, Strullu-Darrien C. 2014. The origin and early evolution of roots. Plant Physiology 166: 570–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambers H, Chapin FSIII, Pons JL. 2008. Plant physiological ecology. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor DW. 2002. Carbon and nitrogen assimilation in relation to yield: mechanisms are the key to understanding production systems. Journal of Experimental Botany 370: 773–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malavolta E, Vitti GC, Oliveira AS. 1997. Avaliação do estado nutricional de plantas: Princípios e aplicações, Potafós, Piracicaba. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews A, Carroll BJ, Gresshoff PM. 1989. Development of Bradyrhizobium infection in supernodulating and non-nodulating mutants of soybean (Glycine max [L] Merrill). Protoplasma 150: 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- McAdam SAM, Brodribb TM. 2015. The evolution of mechanisms driving the stomatal response to vapor pressure deficit. Plant Physiology 167: 833–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinzer FC, Goldstein G, Jackson P, Holbrook NM, Guttiérrez MV, Cavelier J. 1995. Environmental and physiological regulation of transpiration in tropical forest gap species: the influence of boundary layer and hydraulic properties. Oecologia 101: 514–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messinger SM, Buckely TN, Mott KA. 2006. Nitrogen can improve the rapid response of photosynthesis to changing irradiance in rice (Oryza sativa L) plants. Plant Physiology 140: 771–778.16407445 [Google Scholar]

- Mortier V, Holsters M, Goormachtig S. 2012. Never too many? How legumes control nodule numbers. Plant Cell and Environment 35: 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemenzo-Calica P, Indrasumunar A, Scott P, Dart P, Gresshoff PM. 2016. Nodulation and symbiotic nitrogen fixation in the biofuel legume tree Pongamia pinnata. Atlas Journal of Biology 274–291. [Google Scholar]

- Nobel PS. 2009. Physicochemical and environmental plant physiology, 4th edn Amsterdam: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pathre U, Sinha AK, Shirke PA, Sane PV. 1998. Factors determining the midday depression of photosynthesis in trees under monsoon climate. Trees 12: 472–481. [Google Scholar]

- Peoples MB, Brockwell J, Herridge DF, et al. 2009. The contributions of nitrogen-fixing crop legumes to the productivity of agricultural systems. Symbiosis 48: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team 2016. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Available from URL http://wwwr-projectorg/ [Google Scholar]

- Radin JW. 1990. Responses of transpiration and hydraulic conductance to root temperature in nitrogen- and phosphorus-deficient cotton seedlings. Plant Physiology 92: 855–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid DE, Ferguson BJ, Gresshoff PM. 2011. Inoculation and nitrate-induced CLE peptides of soybean control NARK-dependent nodule formation. Molecular Plant Microbe Interations 24: 606–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi C, Bogusz D, Franche C. 2013. Biological nitrogen fixation in non-legume plants. Annals of Botany 111: 743–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schölander PF, Hammel HT, Hemingsen EA, Bradstreet ED. 1965. Hydrostatic pressure and osmotic potentials in leaves of mangroves and some other plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of American 51: 119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert KR, Ryle GJA. 1980. The energy requirements for nitrogen fixation in nodulated legumes. In: Summerfield RJ, Bunting H, eds, Advances in legume science. Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Carroll BJ, Gresshoff PM, Herridge DF. 1995. Field assessment of supernodulating genotypes of soybean for yield, N2 fixation and benefit to subsequent crops. Soil and Environmental Biochemistry 27: 563–569. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Júnior EB, Favero VO, Xavier GR, Boddey RM, Zilli JE. 2018. Rhizobium inoculation of cowpea in Brazilian cerrado increases yields and nitrogen fixation. Agronomy Journal 110: 722–727. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair TR, Devi J, Shekoofa A, et al. 2017. Limited-transpiration response to high vapor pressure deficit in crop species. Plant Science 260: 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser RJ, Srivastava A, Tsimilli-Michael M. 2000. The fluorescent transient as a tool to characterise and screen photosynthesic samples. In: Yunus M, Pathre U, Mohanty P, eds. Probing photosynthesis: mechanisms, regulation and adaptation. London: Taylor and Francis, 445–483. [Google Scholar]

- Strasser RJ, Srivastava A, Tsimilli-Michael M. 2004. Analysis of the chlorophyll a fluorescence transient. In: Govindjee Papageorgiou G, eds. Advances in photosynthesis and respiration chlorophyll fluorescence: a signature of photosynthesis. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 321–362. [Google Scholar]

- Streeter JG. 1980. Carbohydrates in soybean nodules. Plant Physiology 66: 471–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulieman S. 2011. Does GABA increase the efficiency of symbiotic N2 fixation in legumes? Plant Signaling and Behavior 6: 32–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Ye M, Peng S, Li Y. 2016. Nitrogen can improve the rapid response of photosynthesis to changing irradiance in rice (Oryza sativa L) plants. Scientific Reports 6: 31305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegeder M, Masclaux‐Daubresse C. 2017. Source and sink mechanisms of nitrogen transport and use. New Phytologist 217: 35–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thach LB, Shapcott A, Schmidt S, Critchley C. 2007. The OJIP fast fluorescence rise characterizes Graptophyllum species and their stress responses. Photosynthesis Research 94: 423–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres Netto A, Campostrini E, Oliveira JG. Bressan-Smith RE. 2005. Photosynthetic pigments, nitrogen, chlorophyll a fluorescence and SPAD-502 readings in coffee leaves. Scientia Horticlturae 104: 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Tyree MT, Velez V, Dalling JW. 1998. Growth dynamics of root and shoot hydraulic conductance in seedlings of five neotropical tree species: scaling to show possible adaptation to differing light regimes. Oecologia 114: 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahran HH. 1999. Rhizobium-legume symbiosis and nitrogen fixation under severe conditions and in an arid climate. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 63: 968–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarebanadkouki M, Kroener E, Kaestner A, Carminati A. 2014. Visualization of root water uptake: Quantification of deuterated water transport in roots using neutron radiography and numerical modeling. Plant Physiology 166: 487–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarebanadkouki M, Meunier F, Couvreur V, Cesar J, Javaux M, Carminati A. 2016. Estimation of the hydraulic conductivities of lupine roots by inverse modeling of high-resolution measurements of root water uptake. Annals of Botany 188: 853–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li K, Chen L, et al. 2015. microRNA167c-directed regulation of the auxin response factors, GmARF8a and GmARF8b, is required for soybean (Glycine max L) nodulation and lateral root development. Plant Physiology 168: 984–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.