Abstract

This study aimed to obtain possible materials for future antimicrobial food packaging applications based on biodegradable bacterial cellulose (BC). BC is a fermentation product obtained by Gluconacetobacter xylinum using food or agricultural wastes as substrate. In this work we investigated the synergistic effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) and propolis extracts deposited on BC. ZnO NPs were generated in the presence of ultrasounds directly on the surface of BC films. The BC-ZnO composites were further impregnated with ethanolic propolis extracts (EEP) with different concentrations.The composition of raw propolis and EEP were previously determined by gas-chromatography mass-spectrometry (GC-MS), while the antioxidant activity was evaluated by TEAC (Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity). The analysis methods performed on BC-ZnO composites such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), thermo-gravimetrically analysis (TGA), and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) proved that ZnO NPs were formed and embedded in the whole structure of BC films. The BC-ZnO-propolis films were characterized by SEM and X-ray photon spectroscopy (XPS) in order to investigate the surface modifications. The antimicrobial synergistic effect of the BC-ZnO-propolis films were evaluated against Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Candida albicans. The experimental results revealed that BC-ZnO had no influence on Gram-negative and eukaryotic cells.

Subject terms: Biomaterials, Biomaterials

Introduction

Microbiological contamination represents a continuous issue in applications that require sterile conditions. The constant adaptation of microorganism to different environmental conditions generated in the last century infection agents resistant to drugs or antibiotics1–3. Thus, numerous research studies have been directed towards manufacturing of new drugs on one hand, or materials with strict requests in terms of environment safety on the other.

Nowadays, the design of antibacterial or antimicrobial materials implies several important aspects, such as: (i) the use of cheap raw materials and agricultural or food wastes; (ii) facile synthesis and processing method; (iii) biocompatible properties in the case of medical or food applications; (iv) reduced impact on the environment at the end of the life span; (v) manufacturing of biodegradable products.

Bacterial cellulose (BC) results from the fermentation processes of different biomass residues in the presence of Gluconacetobacter xylinum assigned as Acetobacter xylinum bacteria4. Its remarkable properties such as high retention of water, high mechanical and thermal resistance, and crystalline structure due to the 3D irregular disposal of BC nanofibers5 made it suitable for different industrial fields.

Thus, BC and BC composite materials have gained a lot of attention not only in water splitting or waste treatment applications6,7, proton conducting membranes8, supercapacitors, solar cells and transparent displays9,10 but also in the field of wound dressings11,12, food packaging13–16, tissue engineering17,18 and superabsorbent in agriculture applications to improve the pedoclimate conditions for arid soils19.

The development of BC-based materials involved also antimicrobial applications, although pristine BC has no antimicrobial properties. For this reason, considerable effort has been made to modify BC in order to increase such characteristics. These methods include grafting of aldehyde groups on the surface20, modification with different inorganic nanoparticles that exhibit antimicrobial properties (ZnO, TiO2, CuO, Ag nanoparticles, etc.)21,22 or immobilization of different peptides12,23. Furthermore, recent studies involved the tailoring of various polymer films or commercially food packages with essential oils which are known as natural antimicrobial agents and rated as safe for medical and food applications by European Union24,25.

Inorganic material ZnO was involved in numerous commercial applications related to electronic and optical devices, coatings and dyes, cosmetics, drugs, photocatalytic degradation processes of organic dyes for wastewater treatment26–29, due to its wide bandgap (3.4 eV), large excitation of binding energy (60 meV), and high thermal stability30.

In food engineering applications, ZnO NPs has gained much attention in research studies due to its intrinsic antimicrobial properties and low toxicity to human body15,31,32.

It is well known, that the nanocomposites of BC with ZnO NPs shows antibacterial activity. Until now several techniques were employed for enhancing the antibacterial properties of BC films such as: (a) immersion of BC films into aqueous dispersion of commercial ZnO NPs; (b) generation of ZnO NPs by hydrothermal or sol-gel processes using zinc(II) acetate or zinc(II) nitrate as precursor in the presence of BC films33–35; (c) ZnO NPs deposit on BC dry and wet films by matrix-assisted-pulsed-light-evaporation (MAPLE)36.

Also, the extracts of essential oils such as curcumin, eugenol or thymol were used to induce antimicrobial properties of food packages against bacterial strains and extend the life time of food products25,37–39.

It is well known that propolis is a natural resinous bee product with more than 300 components produced by bees to seal and protect their hive against pathogenic agents40,41. Based on these characteristics, propolis extracts were used until now to study their biological effect in terms of antimicrobial materials42 or biomedical implants43.

Thus, the novelty of this work was to use biodegradale BC films modified with ZnO NPs and EEP using propolis from Dolj County, Romania for possible applications as food packaging with antimicrobial properties. The motivation for designing such materials was based on the simplicity of the coating/deposition methods compared to other studies44 and on the use of biodegradable organic matrix support, which can easily be obtained using agricultural or cheap food wastes45. Also, this study was related to the investigation of the synergistic effect between ZnO NPs and EEP in terms of antimicrobial properties against prokaryotic cells of E. coli, B. Subtilis, and eukaryotic cells of C. albicans strains, effect which was not taken into consideration until know to our knowledge.

Experimental

Materials

Bacterial cellulose (BC) was obtained in Mass Transfer Laboratory of University Politehnica of Bucharest by employing a modified method of Hestrin - Schramm [MHS] culture medium with 2% wt. carbon source using wastes of forest fruits in a static culture at 28 °C for 7 days46. The BC pieces were microbiologically inactivated in an aqueous solution of NaOH 0,5 N at 90 °C for 1 hour and then rinsed repeatedly with deionized water until neutral pH. Raw propolis produced by Apis mellifera carnica bee specie was purchased from local beekeepers of Dolj County, Romania and used without further purification. Zinc acetate (Sigma-Aldrich), ammonia (25 wt.%) (Sigma-Aldrich), ethanol (96% vol.) (Redox) were used as such. Escherichia Coli (K12-MG1655)., B. subtilis Spizizenii Nakamura (ATCC 6633), Candida albicans (ATCC10231) were selected from the strain collection of Chemical and Biochemical Engineering Department of University Politehnica of Bucharest.

Methods

Ultrasound-assisted synthesis of ZnO NPs

In a 50 mL round flask 0.07 g of zinc acetate and 20 mL of distilled water were added. Ammonia (25% wt.) was further added until a pH of 11 was reached. The reactions were kept for 2 min at temperature of 60 °C immersed in ultrasonic bath at two different frequencies of 40 kHz, respectively 100 kHz. The samples were encoded ZnO-40 US and ZnO-100 US. For comparison ZnO NPs were obtained after 2 min of continuous stirring by conventional method (without ultrasounds) in the absence of BC keeping the rest of the parameters, constant.

Ultrasound synthesis of BC-ZnO films

The purified BC was cut in small slices with dimensions of 4 × 3 cm. Thus, 22 g of BC (98 % wt. moisture) were stirred in a solution of zinc acetate (0.4987 g) previously dissolved in 143 mL of distilled water. Ammonia (25 % wt.) was added until pH = 11 was reached in order to obtain the ZnONPs on the surface of the BC structure. The reactions were performed considering the same frequencies as for blank ZnO (Section 2.2.1). The BC-ZnO films were dried until constant mass and further cut into discs with diameter of 6 mm.

Preparation of propolis extracts

Four different concentrations of propolis aliquots(3.5 % wt, 7 % wt., 11 % wt, and 15 % wt assigned as EEP1, EEP2, EEP3, respectively EEP4) were prepared using raw propolis and ethanol (96 % vol.) as solvent by continuous stirring for 24 hours. The clear yellowish-orange alcoholic extracts were recovered after centrifugation and used as such to modify the BC-ZnO films.

Preparation of BC-ZnO-propolis films

BC-ZnO discs were impregnated with propolis extracts in three sequential steps (deposition of 1 μL of EEP/step) in order to cover the whole surface of the BC-ZnO substrates.

Characterization

A FEI Quanta Inspect F scanning electron microscope (SEM) coupled with an energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) detector was used for the morphological investigation of the BC-ZnO composite materials; in order to achieve conductive surfaces, the samples were coated with a thin layer of gold (few nm) by DC sputtering.

The as-prepared composites were subjected to thermal analysis in the 20–1000 °C temperature range, in air, with the help of a Shimadzu DTG-60 equipment.

The formation of ZnO layer and organic propolis deposited on BC substrate were analyzed by XPS EnviroESCATM (SPECSTM Surface NanoAnalysis GmbH) equipped with monochromatic Aluminum Kα excitation (hν = 1486.7 eV). The measurements were performed at 1mbar in inert atmosphere of Argon after fixing the samples with Carbon tape on standard plate. Sample deconvolution was carried out using C 1 s hybridization peak at 285.0 eV.

The antioxidant activity of the propolis samples was evaluated using DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) free radical neutralization assay according to47 with slight modifications (described in Supplementary Information).

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis was performed on a Clarus 680 Perkin Elmer gas chromatograph equipped with a MS TurboMass-Perkin Elmer detector. The chromatographic column used for the analysis of propolis extracts was Elite 35 –MS (35% Diphenyl/65% Dimethyl polysiloxane, 30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. × 0.25 μm film thickness). Helium (99.999% purity), the carrier gas, was introduced at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The propolis samples were analyzed by keeping a strict temperature regime of the chromatographic column: first at 100 °C for 2 min, then increased to 200 °C with 10 °C/min and further kept at 200 °C for 2 min. In the end, the temperature was raised with 5 °C/min to 280 °C and kept at this temperature for 9 min/sample. The samples (2 μL) were injected in split mode at 250 °C.

The antimicrobial tests were performed using the disc diffusion method. The discs used in antimicrobial experiments have controlled dimensions (diameter 6 mm ± 0.2, and thickness of 0.2 mm ± 0.05) and their sterilization was performed using UV lamp (UVGL-58, Multiband UV, UVP, U.S.A.) at 254 nm for 30 minutes. For bacterial strains Nutrient Agar was used (Carl Roth GmbH + Co.KG), while for yeast strain PDA (Potato-Dextrose-Agar - Carl Roth GmbH + Co.KG) was chose as culture media. The whole culture media were sterilized by autoclaving (Raypa), at 121 °C for 20 min. The plates were inoculated using cell depletion technique with 0.1 mL cell suspension with concentration 0.5 ± 0.1 OD (at 600 nm) followed by incubation at specific temperature (37 °C for all strains) for 72 h.

Results and Discussions

Morphological characterization

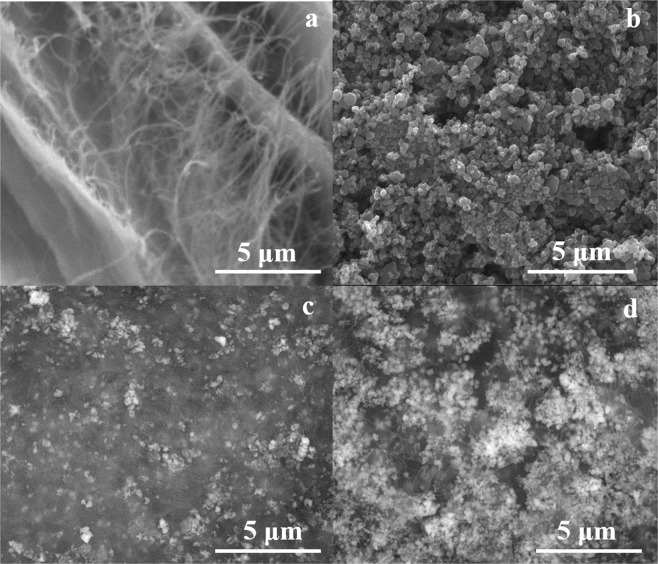

The first step in our research study was to investigate the morphology of unmodified BC films (Fig. 1a), respectively ZnO NPs obtained in the absence of BC and ultrasounds (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

SEM micrographs of BC films (a), ZnO NPs (b), BC-ZnO-40US (c), and BC-ZnO-100US (d).

The BC films presented an irregular distribution of the cellulose fibers confirming the porous areas of the membranes according to literature data48.

Research data related to unconventional methods used for the synthesis of nanoparticles revealed that there is a strong connection between controlled sizes and antimicrobial activity49.

In our case, in the absence of ultrasounds the inorganic ZnO structures had different sizes and shapes (Fig. 1b), while in the case of the assisted-ultrasound synthesis method, at 40 kHz (BC-ZnO-40US), the inorganic nanoparticles appear uniformly distributed due to a reduced growth effect of the particles50 (Fig. 1c). By analysing few tens of quasi-spherical particles in the case of each sample, particle diameters in the range 70 ÷ 90 nm were determined for 40 and 100 kHz frequency respectively, most of the time being gathered as aggregates with sizes up to 1 μm. The presence of ultrasounds allows a better control of the obtaining process of relatively monodisperse inorganic nanoparticles50 and the application of ultrasounds determined the entrapment of ZnO NPs not only on the surface of the BC films, but also in the porous parts of the membranes forming agglomerated structures between the irregular fibers (Fig. 1c). The increase of frequency (100 kHz) during the deposition of the inorganic particles led to a higher amount of ZnO NPs deposited on the surface and larger agglomerates embedded deeper down in the BC structure for BC-ZnO-100US films (Fig. 1d).

EDX analysis on BC-ZnO films

The formation of ZnO on the BC films was confirmed by EDX analysis (Fig. 2). As expected, the composite films obtained at 100 kHz registered almost a double amount of metallic element on their surface (12.73 wt.%), compared to those obtained at 40 kHz (7.25 wt.%) which are in agreement with the results attained by SEM analyses. The carbon signals belong to the BC natural polymer. Moreover, in order to demonstrate the homogeneous distribution of inorganic phase on the surface of BC substrate, compositional maps (Fig. 2b) were recorded for atoms of interest: C as representative for BC and Zn for ZnO, O being common for both of them. As it can be observed, in both cases, Zn concentration does not show significant gradients from one area to another, thus confirming an uniform distribution of the inorganic particles on BC surface.

Figure 2.

EDX analysis performed on both types of composite films obtained at 40 kHz, respectively 100 kHz: (a) spectra and elemental composition and (b) elemental mapping.

TGA analysis of BC-ZnO films

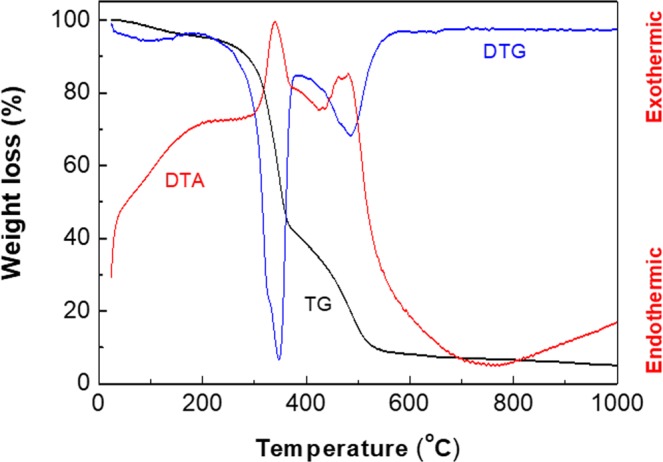

The BC-ZnO composite films were investigated in order to evaluate the thermal behavior of the hybrid materials and the ZnO NPs loading on the BC membrane.

In Fig. 3 the thermo-gravimetric (TG, DTG), respectively the differential thermal analysis only for BC-ZnO-100US is presented, since the thermal behaviour of our two samples obtained at different frequencies was similar. The first temperature range, from room temperature to 200 °C, are characterized by minor weight loss (5%) and can be explained by the endothermic removal of moisture adsorbed on the surface of the samples.

Figure 3.

Thermal analysis of BC modified with ZnO.

In the second stage, an accentuated weight loss occurs between 200 and 380 °C, which can be attributed to the exothermic decomposition of BC membrane (Fig. 3).

In this temperature range, the weight loss of the composites was 57 % for BC-ZnO-40US, respectively 62 % for BC-ZnO-100US. The final significant weight loss stage was registered between 380 °C and 580 °C for both samples and associated with an exothermic effect which ca be assigned either to a more crystalline form of BC having a better thermostability or to a mixing effect, the mineral phase on the surface of BC fibre enhancing their thermal properties. After complete removal of the gas generating components, the total amount of the inorganic particles remaining in the samples was around 5% wt.

XPS analysis of the BC-ZnO-propolis composites

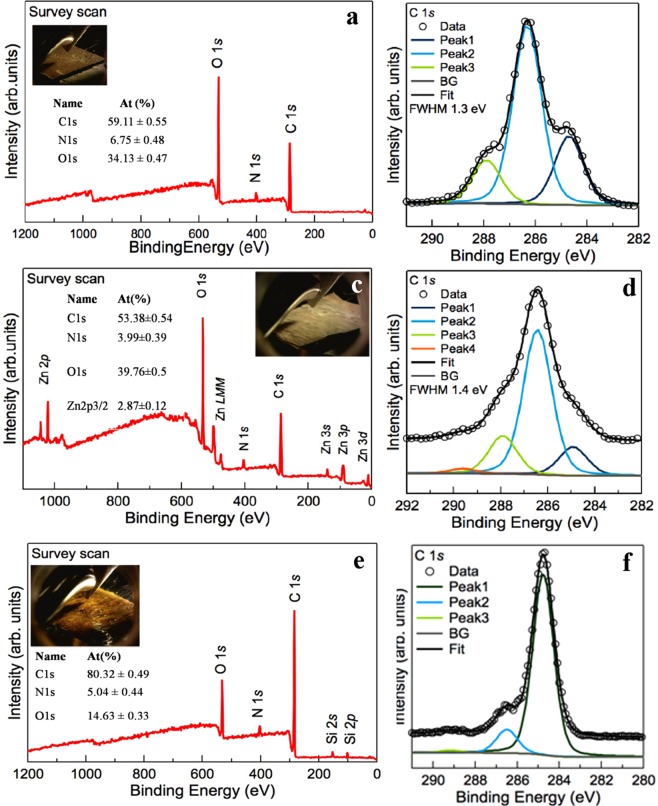

In order to obtain more informationson the chemistry of the pristine and modified BC, high-resolution spectra were performed.As expected, signals for carbon, nitrogen and oxigen were registered for all samples.

At the binding energy of 285.0 eV,C1s was assigned to un-oxidiezed carbon atom from C-H, C-C, respectively C=Cgroups. The signals registered at 286.5 eV and 288 eV were attributed to C-O single bond and C=O double bond. The composition of pristine BC (Fig. 4a) and BC-ZnO films (Fig. 4c) (Taokaew et al., 2015)51 is mostly formed by carbon (aproximatley 53÷60%), while in the case of BC-ZnO-propolis films (Fig. 4e) it reaches around 80%. In this study, our purpose was to use pristine BC without any supplimentary purifications (except the ones mentioned in Section 2.1). For this reason, N1s scans were also performed on all samples. The signals registered at 400 eV were assigned to free amine (H2N-C) and amide (O=C-N-C) groups which are coming from residual proteins of bacteria in the case of pristine BC (Fig. 4a) and from propolis organic components (Fig. 4e). For the samples modified with inorganic particles the XPS spectra for ZnO was registered at 1021 eV, thus confirming the presence of ZnO layer on the surface of the BC film (Fig. 4c). One can notice that the peaks from ZnO overlapp the peaks of Zn metal which was also confirmed by other literature studies(assigned as Zn2p3/2 spectrum) (Al-Gaashani et al., 201352; Biesinger et al., 201053). In the case of BC-ZnO-propolis composite materials XPS analysis revealed that the BC-ZnO films were completely covered with a layer of propolis and few disruptures appear in the material (silica signals coming from the standard substrate were registered) (Fig. 4e).

Figure 4.

XPS survey over the surface of: (a) BC; (c) BC-ZnO, (e) BC-ZnO-propolis films, respectively deconvolution of C1s peak (b,d,f).

Antioxidant properties of propolis

The antioxidant activity of ethanolic extracts of propolis was determined using the DPPH method (as described in Supplementary information). Samples containing raw propolis and EEP with lowest concentration of propolis (3.5% wt.) were evaluated. The results for radical scavenging activity (RSA) indicate that the solid sample of propolis and EEP (3.5% wt.) are slightly similar: 64.25% for raw propolis and 57.78% respectively. These results indicate a high antioxidant activity, sustained by the increased content of polyphenols and flavonoids54,55 also confirmed by GC-MS analysis (Table S1 Supplementary information).

Antimicrobial results

The microorganisms selected in this study were both saprophytic and pathogenic, with a large spreading in human body and natural environment.Candida albicans is a pathogenic yeast and represents a common member of the human gut flora56. Bacillus subtilis, is a Gram-positive, catalase-positive bacterium, which forms spores; it is also found in soil and the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants57. Escherichia coli is a Gram-negativebacteria which can be found in contaminated water or food58 and human body. Its pathogenic effect has increased lately due to the abuse of antibiotics, which determined the increase of bacteria resistance59.

Thus, our purpose involved the use of ZnO and EEP as an alternative to commercial antibiotics in order to prevent the enhancement of the bacteria resistance.

The blank EEP solutions (deposited on filter paper) were studied in order to evaluate their antibacterial effect against pathogen Gram-negative bacteria and yeast, respectively on saprophyte Gram-positive bacteria. The results indicate a minimum inhibition concentration (MIC) smaller than 0.438 mg/mL for all EEP solutions tested (Figs. S1–S3 - Supplementary information).

In Table 1, the antimicrobial activity is presented for all samples to highlight a possible synergistic effect between all the components of the hybrid materials. In the first step, antimicrobial studies were performed for EEP deposited on pure BC films while using ethanol on BC films as control sample. As it can be observed, in the case of EEP the antimicrobial effect decreases in the order B. subtilis > C. albicans > E. coli. In the case of ZnO particles, regardless of the ultrasound frequency used to obtain BC-ZnO composites, the antimicrobial effect was noticed only in the case of B. subtilis. At reduced frequency, the two components (EEP and ZnO) induced a synergistic effect upon Gram positive bacteria (B. subtilis) and yeast (C. albicans) compared to Gram negative (E. coli) bacteria which are not sensitive to this synergistic effect. The increase of the frequency level for the synthesis of ZnO particles in the presence of BC substrate did not improved the antimicrobial activity considering the synergistic effect except for C. albicans at higher concentrations of EEP (EEP3, respectively EEP4).

Table 1.

Antimicrobial activity of composite films against E. coli, B. subtilis, C. albicans.

| Composite film code with EEP concentration | E. coli | B. subtilis | C. albicans | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IZ, mm | MIC, mg/mL | IZ, mm | MIC, mg/mL | IZ, mm | MIC, mg/mL | |

| BC -ETOH (control) | 2 ± 0.05 | 1.89 | 0 (+) | >1.89 | 2 ± 0.07 | 1.89 |

|

BC-EEP1 (control) (S1*) |

3 ± 0.1 | 1.3 | 8 ± 0.25 | <0.44 | 3 ± 0.15 | 1.3 |

|

BC-EEP2 (control) (S2*) |

1.5 ± 0.05 | >0.8 | 9 ± 0.35 | <0.44 | 4 ± 0.25 | 0.44 |

|

BC- EEP3 (control) (S3*) |

0 (+) | >1.89 | 8 ± 0.22 | <0.44 | 4 ± 0.25 | 0.44 |

|

BC- EEP4 (control) (S4*) |

5 ± 0.25 | 0.44 | 12 ± 0.05 | < 0.44 | 7 ± 0.1 | <0.44 |

| BC-ZnO-40 (control) | 0 (+) | >1.89 | 4 ± 0.13 | 0.44 | 0 (−) | >1.89 |

| BC-ZnO-40-EEP1 (F1S1*) | 0 (+) | >1.89 | 5 ± 0.15 | 0.44 | 0 (+) | >1.89 |

|

BC-ZnO-40-EEP2 (F1S2*) |

0 (+) | >1.89 | 8 ± 0.25 | <0.44 | 1 ± 0.05 | >0.8 |

|

BC-ZnO-40-EEP3 (F1S3*) |

0 (+) | >1.89 | 4 ± 0.05 | 0.44 | 3 ± 0.35 | 1.3 |

|

BC-ZnO-40-EEP4 (F1S4*) |

0 (+) | >1.89 | 4 ± 0.35 | 0.44 | 2 ± 0.05 | 1.89 |

| BC-ZnO-100 (control) | 0 (+) | >1.89 | 4 ± 0.15 | 0.44 | 0 (+) | >1.89 |

|

BC-ZnO-100-EEP1 (F2S1*) |

0 (+) | >1.89 | 4 ± 0.25 | 0.44 | 0 (+) | >1.89 |

|

BC-ZnO-100-EEP2 (F2S2*) |

0 (+) | >1.89 | 7 ± 0.15 | <0.44 | 0 (+) | >1.89 |

|

BC-ZnO-100-EEP3 (F2S3*) |

0 (+) | >1.89 | 3 ± 0.25 | 0.44 | 5 ± 0.15 | 1.3 |

|

BC-ZnO-100-EEP4 (F2S4*) |

0 (+) | >1.89 | 2 ± 0.15 | 0.44 | 4 ± 0.25 | 1.89 |

*Assigned codes for BC-ZnOfilms impregnated with EEP solutions from Supplementary information.

Due to a larger inhibition zone (IZ) of EEP2 compared to EEP3, respectively EEP4, the diffusion of EEP with lower concentration from BC-ZnO-propolis films is higher. The diffusion phenomenon is evidenced by yellowish area surrounding the BC-ZnO-propolis films in Fig. S4, respectively Fig. S7 for both types of composite films BC-ZnO-40US (assigned as F1 in Supplementary information), and BC-ZnO-100US (assigned as F2 in Supplementary information). In the same time, the diffusion is also confirmed by mass inhibition phenomenon proved by clear areas corresponding to IZ (Figs. S4 and S7). In this case, the MIC value for B. subtilis was found 0.438 mg/mL (Table 1).

The BC-ZnO composite films modified with different concentrations of EEP did not show inhibition against the E. coli strain, the MIC for these probes being higher than 1.89 mg/mL corresponding to EEP4. Thus, in this case, for Gram-negative bacteria our films require a higher concentration of propolis (Table 1). Furthermore, the synergistic effect of BC modified with both EEP and ZnO did not influenced the growth of E. coli (Table 1) regardless of the EEP concentration or the frequency applied for inorganic particles synthesis (Figs. S5, respectively S8 – Supplementary information). This behavior could be attributed to the thick and continuous organic pellicle of propolis extracts that inhibit the diffusion of ZnO.

For the eukaryotic cells, C. albicans, the ZnO nanoparticles alone did not manifest antimicrobial effect, but in the interaction with EEP, at higher concentrations, EEP3 forBC-ZnO-40US, respectively EEP4 for BC-ZnO-100US, the antimicrobial effect is present with a significant IZ (Table 1). In the case of BC-ZnO-40US film the MIC value was 0.8 mg/mL, respectively 1.3 mg/mL for BC-ZnO-100US film. These results indicated that the film BC-ZnO-100US has a higher antimicrobial activity against C. albicans (as shown in Fig. S6 compared to Fig. S9).

The antimicrobial activity of propolis is determined by the presence of phenolic components such as flavonoids60. The antimicrobial effect of propolis is based mostly on the cell membranes degradation that led to a loss of potassium ions and finally to the cell autolysis55,61. Quercetin is a flavonoid often found in all types of propolis that determines the increasing of the membrane’s permeability causing the cell material loss62. In these circumstances bacterial motility is reduced to zero, and also membrane transport ability and capacity to synthesis adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is lost.

Our study revealed that propolis had a stronger influence upon the Gram-positive bacteria compared to Gram-negative and eukaryote cells. In general, natural extracts have normally a higher activity against Gram-positive bacteria than Gram-negative bacteria59, thus confirming our results. Gram-negative bacteria and eukaryote cells are more resistant than the Gram-positive due to a more complex chemical structure of the surrounding layers. The cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria contains polysaccharide, which has an important role in the antigenicity, toxicity and pathogenicity of the microorganisms. Furthermore, these bacteria also possess a higher lipid amount compared to Gram-positive bacteria63. Thus, the endotoxin (a lipopolysaccharide complex) is responsible for the diminished antimicrobial effect of the propolis or ZnO NPs or both, acting as a self-preserving mechanism of the cell.

Phenolic acids such as ferulic (compounds found in our samples – Table S1 - Supplementary information) and gallic acids disturb both the cell membranes of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The effect consists in the changes of cell surface hydrophobicity and charging of the cell wall, which also is responsible for the leakage of cytoplasmic content64. The caffeic acid derivative has a similar effect on Candida cytoplasmatic membrane65. Another possible effect on the C. albicans cell wall can be attributed to caffeic acid derivatives that interact with 1,3-β-glucan synthase enzyme66.

The results obtained in this study showed that the antimicrobial activity of propolisis related to the total phenol content of the EEP extracts as shown in Table S1 (Supplementary information).

Nevertheless, the effectiveness of bee’s products depends on differences regarding the chemical composition of the product, bee species and the pedoclimatic conditions of the region63. Thus, our study could be considered as an alternative to develop composite materials with selective antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria and yeast due to a synergistic effect between ZnO particles and EEP.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have obtained eco-friendly biodegradable BC films modified with ZnO NPs by ultrasound-assisted synthesis method impregnated with EEP solutions for possible future applications in food packaging with antimicrobial properties.

The BC-ZnO-propolis films have been characterized to evidence the deposition of ZnO, respectively EEP and their morphologic aspect by SEM, TGA, EDX, XPS. The composition of raw propolis and EEP solutions were determined by GC-MS, while the antioxidant activity was evaluated by DPPH method.

For the antimicrobial tests the BC-ZnO-propolis films were put onto culture media inoculated with E. coli, B. subtilis, and C. albicans. E. coli has proved to be highly resistant to the synergistic effect of both ZnO NPs and EEP concentration in all cases.

The synergistic effect between ZnO NPs and EEP acts upon B. subtilis at lower concentrations of EEP (EEP2) correlated with 40 kHz frequency applied for the synthesis of ZnO NPs, while in the case of C. albicans, the synergistic effect was more pronounced at enhanced concentration of EEP (EEP3) and higher ultrasound frequency (100 kHz).

Unexpectedly, the synergistic effect was diminished at the highest concentration of EEP for both BC-ZnO-40-EEP4 and BC-ZnO-100-EEP4 due to the formation of a compact pellicle of propolis organic compounds that acted like a barrier in the diffusion process of ZnO NPs.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

CB acknowledges for financial support from Executive Unit for Financing Higher Education, Research, Development and Innovation (UEFISCDI) through project Smart Scaffolds Built on Biocellulose 3D Architecture or Artificial Electrospun Templates for Hard Tissue Engineering (ScaBiES), PN-III-P1-1.1-TE-2016-0871 (contract number 66/2018). The authors gratefully acknowledge University Politehnica of Bucharest for financial support through PubArt - Program for supporting publication of articles and scientific communications.

Author contributions

Alexandra Mocanu - have made substantial contributions to the conception of the article; design of the work; biomaterial production; results interpretation. Gabriela Isopencu - have made substantial contributions to the conception of the article; antimicrobial and antioxidant analysis; results interpretation. Cristina Busuioc - SEM, TGA analysis; results interpretation; substantially revised it. Oana-Maria Popa – GS-MS analysis; results interpretation. Paul Dietrich – XPS analysis; results interpretation. Liana Socaciu-Siebert - XPS analysis; results interpretation.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-54118-w.

References

- 1.Dzotam JK, Touani FK, Kuete V. Antibacterial activities of the methanol extracts of Canarium schweinfurthii and four other Cameroonian dietary plants against multi-drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2016;23:565–570. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gavaldà L, Pequeño S, Soriano A, Dominguez MA. Environmental contamination by multidrug-resistant microorganisms after daily cleaning. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:776–778. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muller MP, et al. Antimicrobial surfaces to prevent healthcare-associated infections: a systematic review. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2016;92:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian D, Shen F, Hu J, Renneckar S, Saddler JN. Enhancing bacterial cellulose production via adding mesoporous halloysite nanotubes in the culture medium. Carbohyd Polym. 2018;198:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah N, Ul-Islam M, Khattak WA, Park JK. Overview of bacterial cellulose composites: A multipurpose advanced material. Carbohyd Polym. 2013;98:1585–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dal’Acqua N, et al. Hydrogen photocatalytic production from the self-assembled films of PAH/PAA/TiO2 supported on bacterial cellulose membranes. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 2018;43:15794–15806. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.06.176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dal’Acqua N, et al. Characterization and Application of Nanostructured Films Containing Au and TiO2 Nanoparticles Supported in Bacterial Cellulose. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2015;119:340–349. doi: 10.1021/jp509359b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogalsky S, et al. New proton conducting membrane based on bacterial cellulose/polyaniline nanocomposite film impregnated with guanidinium-based ionic liquid. Polymer. 2018;142:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2018.03.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng S, et al. Flexible polypyrrole/cobalt sulfide/bacterial cellulose composite membranes for supercapacitor application. Synthetic Met. 2016;222:285–292. doi: 10.1016/j.synthmet.2016.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ummartyotin S, Juntaro J, Sain M, Manuspiya H. Development of transparent bacterial cellulose nanocomposite film as substrate for flexible organic light emitting diode (OLED) display. Industrial Crops and Products. 2012;35:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.06.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanyang, M. L., Sapun, S. N., Jawaid, M., Mohammad, F. & Salit, M. S. Bacterial Nanocellulose Applications for Tissue Engineering, in Nanocellulose and Nanohydrogel Matrices. John Wiley and Sons Inc. (2017).

- 12.Sulaeva I, Henniges U, Rosenau T, Potthast A. Bacterial cellulose as a material for wound treatment: Properties and modifications. A review. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33:1547–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiulan I, Frone AN, Panaitescu DM, Nicolae CA, Trusca R. Surface properties, thermal, and mechanical characteristics of poly(vinyl alcohol)–starch-bacterial cellulose composite films. J Appl Polym Sci. 2018;135:45800. doi: 10.1002/app.45800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padrão J, et al. Bacterial cellulose-lactoferrin as an antimicrobial edible packaging. Food Hydrocolloid. 2016;58:126–140. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi L-E, et al. Synthesis, antibacterial activity, antibacterial mechanism and food applications of ZnO nanoparticles: a review. Food Addit Contam A. 2014;31:173–186. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2013.865147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stroescu, M., Isopencu, G., Busuioc, C. & Stoica-Guzun, A Antimicrobial Food Pads Containing Bacterial Cellulose and Polysaccharides, in Cellulose-Based Superabsorbent Hydrogels, ed. by Mondal MIH. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 1–36 (2018).

- 17.Ahn S-J, et al. Characterization of hydroxyapatite-coated bacterial cellulose scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Biotechnol Bioproc E. 2015;20:948–955. doi: 10.1007/s12257-015-0176-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torgbo S, Sukyai P. Bacterial cellulose-based scaffold materials for bone tissue engineering. Appl Mater Today. 2018;11:34–49. doi: 10.1016/j.apmt.2018.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demitri C, Scalera F, Madaghiele M, Sannino A, Maffezzoli A. Potential of Cellulose-Based Superabsorbent Hydrogels as Water Reservoir in Agriculture. International Journal of Polymer Science. 2013;2013:6. doi: 10.1155/2013/435073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stumpf TR, Yang X, Zhang J, Cao X. In situ and ex situ modifications of bacterial cellulose for applications in tissue engineering. Mater Sci Eng C. 2018;82:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.11.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Oliveira Barud HG, et al. A multipurpose natural and renewable polymer in medical applications: Bacterial cellulose. Carbohyd Polym. 2016;153:406–420. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu C, Yang D, Wang Y, Shi J, Jiang Z. Fabrication of antimicrobial bacterial cellulose–Ag/AgCl nanocomposite using bacteria as versatile biofactory. J Nanopart Res. 2012;14:1084. doi: 10.1007/s11051-012-1084-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malheiros PS, et al. Immobilization of antimicrobial peptides from Lactobacillus sakei subsp. sakei 2a in bacterial cellulose: Structural and functional stabilization. Food Packaging Shelf. 2018;17:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.fpsl.2018.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muriel-Galet V, et al. Development of antimicrobial films for microbiological control of packaged salad. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012;157:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valero D, et al. The combination of modified atmosphere packaging with eugenol or thymol to maintain quality, safety and functional properties of table grapes. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2006;41:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2006.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coleman, V. A. & Jagadish, C. Chapter 1 - Basic Properties and Applications of ZnO, in Zinc Oxide Bulk, Thin Films and Nanostructures, ed. by Jagadish C and Pearton S. Elsevier Science Ltd, Oxford, pp. 1–20 (2006).

- 27.Djurišić AB, Chen X, Leung YH, Man Ching Ng A. ZnO nanostructures: growth, properties and applications. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:6526–6535. doi: 10.1039/c2jm15548f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moezzi A, McDonagh AM, Cortie MB. Zinc oxide particles: Synthesis, properties and applications. Chem Eng J. 2012;185-186:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.01.076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mu L, Sprando RL. Application of Nanotechnology in Cosmetics. Pharmaceutical Res. 2010;27:1746–1749. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearton SJ, Norton DP, Ip K, Heo YW, Steiner T. Recent progress in processing and properties of ZnO. Progress in Materials Science. 2005;50:293–340. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2004.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Díez-Pascual AM, Díez-Vicente AL. High-Performance Aminated Poly(phenylene sulfide)/ZnO Nanocomposites for Medical Applications. ACS Appl Mater Inter. 2014;6:10132–10145. doi: 10.1021/am501610p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pei X, et al. Effects of dietary zinc oxide nanoparticles supplementation on growth performance, zinc status, intestinal morphology, microflora population, and immune response in weaned pigs. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2019;99:1366–1374. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.9312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costa SV, Gonçalves AS, Zaguete MA, Mazon T, Nogueira AF. ZnO nanostructures directly grown on paper and bacterial cellulose substrates without any surface modification layer. Chem Comm. 2013;49:8096–8098. doi: 10.1039/c3cc43152e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foresti ML, Vázquez A, Boury B. Applications of bacterial cellulose as precursor of carbon and composites with metal oxide, metal sulfide and metal nanoparticles: A review of recent advances. Carbohyd Polym. 2017;157:447–467. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hussein MZB, Yahaya AH, Ling PLC, Long CW. Acetobacter xylenium as a shape-directing agent for the formation of nano-, micro-sized zinc oxide. J Mater Sci. 2005;40:6325–6328. doi: 10.1007/s10853-005-3686-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dinca V, et al. MAPLE-based method to obtain biodegradable hybrid polymeric thin films with embedded antitumoral agents. Biomedical microdevices. 2014;16:11–21. doi: 10.1007/s10544-013-9801-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Avila-Sosa R, Gastélum-Franco MG, Camacho-Dávila A, Torres-Muñoz JV, Nevárez-Moorillón GV. Extracts of Mexican Oregano (Lippia berlandieri Schauer) with Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity. Food Bioprocess Tech. 2010;3:434–440. doi: 10.1007/s11947-008-0085-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mostafa AA, et al. Antimicrobial activity of some plant extracts against bacterial strains causing food poisoning diseases. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2018;25:361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Papadimitriou A, et al. Innovative material containing the natural product curcumin, with enhanced antimicrobial properties for active packaging. Mater Sci Eng C. 2018;84:118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kubiliene L, et al. Alternative preparation of propolis extracts: comparison of their composition and biological activities. BMC Complem Altern M. 2015;15:156. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0677-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silici S, Kutluca S. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of propolis collected by three different races of honeybees in the same region. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2005;99:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siripatrawan U, Vitchayakitti W. Improving functional properties of chitosan films as active food packaging by incorporating with propolis. Food Hydrocolloid. 2016;61:695–702. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ambi A, et al. Are Russian propolis ethanol extracts the future for the prevention of medical and biomedical implant contaminations? Phytomedicine. 2017;30:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valderrama Solano AC, de Rojas Gante C. Two Different Processes to Obtain Antimicrobial Packaging Containing Natural Oils. Food Bioprocess Tech. 2012;5:2522–2528. doi: 10.1007/s11947-011-0626-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dobre ML, Stoica-Guzun A. Antimicrobial Ag-Polyvinyl Alcohol-Bacterial Cellulose Composite Films. J Biobased Mater Bio. 2013;7:157–162. doi: 10.1166/jbmb.2013.1272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stoica-Guzun A, Stroescu M, Jipa I, Dobre L, Zaharescu T. Effect of γ irradiation on poly(vinyl alcohol) and bacterial cellulose composites used as packaging materials. Radiation Physics and Chemistry. 2013;84:200–204. doi: 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2012.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalogeropoulos N, Konteles SJ, Troullidou E, Mourtzinos I, Karathanos VT. Chemical composition, antioxidant activity and antimicrobial properties of propolis extracts from Greece and Cyprus. Food Chem. 2009;116:452–461. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.02.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Retegi A, et al. Bacterial cellulose films with controlled microstructure–mechanical property relationships. Cellulose. 2010;17:661–669. doi: 10.1007/s10570-009-9389-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng Q, Li C, Pavlinek V, Saha P, Wang H. Surface-modified antibacterial TiO2/Ag+ nanoparticles: Preparation and properties. Appl Surf Sci. 2006;252:4154–4160. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2005.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shaik, S., Sonawane, S. H., Barkade, S. S. & Bhanvase, B. Synthesis of Inorganic, Polymer, and Hybrid Nanoparticles Using Ultrasound, in Handbook of Ultrasonics and Sonochemistry. Springer Singapore, Singapore, pp 457-490 (2016).

- 51.Taokaew, S., Phisalaphong, M., & Newby, B-mZ. Modification of bacterial cellulose with organosilanes to improve attachment and spreading of human fibroblasts. Cellulose22, 2311–2324 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Al-Gaashani, R., Radiman, S., Daud, A. R., Tabet, N., & Al-Douri, Y. XPS and optical studies of different morphologies of ZnO nanostructures prepared by microwave methods. Ceramics International39(3), 2283–2292 (2013).

- 53.Biesinger, M. C, Lau, L. W. M. & Gerson, A. R. Resolving surface chemical states in XPS analysis of first row transition metals, oxides and hydroxides: Sc, Ti, V, Cu and Zn. Appl Surf Sci257, 887–898 (2010).

- 54.Haghdoost NS, Salehi TZ, Khosravi A, Sharifzadeh A. Antifungal activity and influence of propolis against germ tube formation as a critical virulence attribute by clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Journal de Mycologie Médicale. 2016;26:298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nina N, et al. Chemical profiling and antioxidant activity of Bolivian propolis. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2016;96:2142–2153. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gow NAR, Yadav B. Microbe Profile: Candida albicans: a shape-changing, opportunistic pathogenic fungus of humans. Microbiology. 2017;163:1145–1147. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McKenney PT, Driks A, Eichenberger P. The Bacillus subtilis endospore: assembly and functions of the multilayered coat. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;11:33. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siripatrawan U, Vitchayakitti W, Sanguandeekul R. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of Thai propolis extracted using ethanol aqueous solution. Int J Food Sci Tech. 2013;48:22–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2012.03152.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rahman MM, Richardson A, Sofian-Azirun M. Antibacterial Activity of Propolis and Honey Against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2010;4:1872–1878. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boukraa L, Sulaiman SA. Rediscovering the Antibiotics of the Hive. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2009;4:206–213. doi: 10.2174/157489109789318505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bellik, Y. & Boukraâ, L. Beneficial effects of propolis for health and chronic diseases. Nova Science Publishers, New York (2012).

- 62.Mirzoeva OK, Grishanin RN, Calder PC. Antimicrobial action of propolis and some of its components: the effects on growth, membrane potential and motility of bacteria. Microbiol Res. 1997;152:239–246. doi: 10.1016/S0944-5013(97)80034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morais M, Moreira L, Feás X, Estevinho LM. Honeybee-collected pollen from five Portuguese Natural Parks: Palynological origin, phenolic content, antioxidant properties and antimicrobial activity. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:1096–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Borges A, Ferreira C, Saavedra MJ, Simões M. Antibacterial Activity and Mode of Action of Ferulic and Gallic Acids Against Pathogenic Bacteria. Microb Drug Resist. 2013;19:256–265. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2012.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sung WS, Lee DG. Antifungal action of chlorogenic acid against pathogenic fungi, mediated by membrane disruption. Phys Appl Chem. 2010;82:219–226. doi: 10.1351/PAC-CON-09-01-08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ma C-M, et al. Synthesis, anti-fungal and 1,3-β-d-glucan synthase inhibitory activities of caffeic and quinic acid derivatives. Bioorgan Med Chem. 2010;18:7009–7014. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.