Abstract

Objective:

To examine the factor structure of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders-Parent Report (SCARED-P) in young children and elucidate normative levels of parent-reported anxiety using a nationally representative sample of parents of children ages 5-12 years living in the United States.

Method:

The 41-item SCARED-P was administered to parents of 1,570 youth who were selected to match the U.S. population on key demographic variables. SCARED-P model fit and mean score differences by age, race/ethnicity, and sex were assessed.

Results:

SCARED-P model fit and subscale reliability appeared almost identical in younger children (ages 5-8) and older children (ages 9-12), although model fit for a five-factor model was poor in both groups. Symptoms of generalized anxiety increased from age 5 to 12, while symptoms of separation anxiety disorder decreased. Parents reported significantly more symptoms of social anxiety in females than males. No significant differences by race/ethnicity were found for mean levels of anxiety or model fit.

Conclusions:

The SCARED-P shows some utility as an anxiety screening instrument in a representative sample of U.S. youth as young as 5-years-old, but caution should be used when interpreting subscale scores.

Keywords: anxiety, children, measurement, SCARED

Anxiety disorders peak in prevalence during childhood, with a median age of onset around 6 years and one-third of youth meeting diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder by age 14 (Merikangas et al., 2010). Anxiety in youth is associated with significant psychosocial impairment (Langley et al., 2004) and places youth at risk for the development of future psychopathology (Pine et al., 1998). Thus, the ability to identify anxiety quickly and easily in childhood is critical. Although structured and semi-structured clinical interviews can be used to diagnose anxiety disorders in youth (e.g., Kaufman et al., 1997), these interviews require trained interviewers and are time-intensive. Consequently, questionnaires are frequently used to assess anxiety symptoms in community and clinical settings. Several such questionnaires exist, including the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., 1997, 1999). Although the SCARED is widely used and demonstrated to be one of the best measures of anxiety symptoms (Myers & Winters, 2002), to our knowledge, no large-scale, nationally-representative study of SCARED scores and factor structure has yet been done with youth in the United States. Further, the SCARED has been primarily validated for use with children ages 8-18, yet the median age of onset of anxiety disorders is age 6. Therefore, research evaluating the utility of the SCARED in younger children is needed. This brief report examines normative levels of parent-reported child anxiety and factor structure of the SCARED-Parent Report (SCARED-P) in a sample of 1,570 parents or guardians of 5-12-year-olds across the U.S. This work is important for elucidating normative levels and clustering of anxiety symptoms in the general U.S. population of children as young as 5-years-old.

The SCARED assesses different types of anxiety based on DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria. Specifically, the SCARED screens for symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), separation anxiety disorder (SAD), social phobia (SP; now termed social anxiety disorder), panic disorder/significant somatic symptoms (PD), and school avoidance (SA). While SA is not a DSM diagnosis, it is significantly impairing for children and families. Of note, diagnostic criteria for these anxiety disorders did not change considerably between DSM-IV and DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013); therefore, the SCARED remains pertinent today. The SCARED includes both a child version (i.e., child self-report on anxiety symptoms, SCARED-C) and an identical parent version (i.e., parent-report on child’s symptoms, SCARED-P). Child and parent reports correlate modestly (Birmaher et al., 1997; Su et al., 2008). While child self-reports may be most useful for older children and adolescents who have the language and insight to report on their symptoms, parent reports may be most useful for younger children who may not yet have this language or insight.

A 38-item version of the SCARED-C was originally normed using a sample of 341 U.S. youths ages 9-18 years (82% white) recruited from a mood/anxiety outpatient clinic; the corresponding 38-item SCARED-P was normed using 300 parents of these youths (Birmaher et al., 1997). In a subsequent study, 41-item versions of the SCARED-C and SCARED-P, which included three additional items reflecting social anxiety, were re-normed using a separate sample of 191 outpatient U.S. youths ages 9-18 years (71% white) and 166 parents (Birmaher et al., 1999). In this second sample, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) yielded a five-factor structure of the SCARED-C and SCARED-P with good internal consistency (α=.78-.87). These factors reflect the symptoms described above (i.e., GAD, SAD, PD, SP, SA). A total cut-off score of 25 (out of 82) resulted in acceptable sensitivity (71%) and specificity (61-71%) for suggesting a probable diagnosis of anxiety disorder. The SCARED-C and SCARED-P are reliable in terms of internal consistency and test-retest reliability (e.g., Birmaher et al., 1997, 1999; Boyd et al., 2003; Hale et al., 2005). The SCARED can discriminate well between anxiety and other psychiatric disorders (Birmaher et al., 1997, 1999) and correlates significantly with other measures of childhood anxiety, including the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (Isolan et al., 2011).

Birmaher and colleagues (1997, 1999) initially validated the SCARED using a clinical sample of anxious youth living in the U.S., but subsequent research has examined the SCARED in larger, more nationally-representative samples of youth across the world (e.g., Muris et al., 1999; Muris et al., 2002; Hale et al., 2005; Su et al., 2008; Isolan et al., 2011). A meta-analysis of 12 international studies that conducted EFA and/or confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine SCARED-C factor structure in clinical and community samples of youth (ages 7-19) showed that eight studies found support for the five-factor solution proposed by Birmaher and colleagues, three found a four-factor solution (GAD, SAD, PD, SP), and one found a three-factor solution (GAD, PD, SP) (Hale et al., 2011). Thus, while most studies do support the original five-factor structure, there is some variability. Notably, the largest studies included in this meta-analysis (n=1340-1975) were conducted in The Netherlands (Hale et al., 2005), Italy (Crocetti et al., 2009), and China (Su et al., 2008). These studies all found support for a five-factor SCARED-C structure that held up across age and sex (Hale et al., 2005; Crocetti et al., 2009; Su et al., 2008), as well as race/ethnic group (Hale et al., 2005). Conversely, the largest community study conducted in the U.S. included 515 youth ages 8-13 and supported a four-factor structure (Wren et al., 2007). This structure differed between Hispanic youth and the full sample (Wren et al., 2007).

The aim of this brief report is to elucidate normative levels of anxiety in U.S. children based on parent report and identify whether the SCARED-P is useful for examining anxiety in children as young as 5-years-old. To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale, nationally-representative study of the SCARED in the United States, which is important for identifying normative levels of anxiety in U.S. youth. Further, most existing international large-scale studies have only examined the psychometric properties of the SCARED-C, which is problematic because the SCARED-P is frequently used in research and clinical settings and some research suggests that the factor structure of the SCARED-P differs from that of the SCARED-C (Wren et al., 2007). Finally, almost all prior studies have been conducted in children ages 8 and older, with the exception of two studies in The Netherlands that included some 7-year-olds (Muris et al., 2001, 2004). Given that the median age-of-onset for anxiety disorders is around age 6 (Merikangas et al., 2010), research evaluating the SCARED in younger samples is needed.

To address these limitations, we first assessed mean levels of parent-reported anxiety symptoms in a nationally representative sample of U.S. children ages 5-12 and examined how mean levels differ by age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Aligning with prior literature examining differences in SCARED scores by age, sex, and race/ethnicity, we hypothesized that symptoms of SAD would decrease across age (Isolan et al., 2011; Su et al., 2008), symptoms of GAD would increase across age (Isolan et al., 2011; Hale et al., 2005; Su et al., 2008), females would show higher levels of SP compared to males (Isolan et al., 2011; Hale et al., 2005; Su et al., 2008; Hale et al., 2011), and mean levels of anxiety would be consistent across race/ethnicity (Hale et al., 2005). Second, we examined the five-factor structure and convergent validity of the SCARED-P in this sample and examined differences in five-factor structure by age and race/ethnicity. We also conducted an exploratory bifactor analysis, given recent research suggesting that most of the SCARED score variance can be accounted for by a general factor, potentially rendering the subscales relatively unreliable (DeSousa et al., 2014).

Method

Sample

A sample of 1,570 parents/guardians of children ages 5-12 years (Mage=8.63 years, SD=2.35; 46.8% female) was recruited from all 50 states and the District of Columbia to be nationally representative of the current U.S. population. The sample was originally recruited for a larger study examining psychometric properties of an instrument assessing parent management training skills (Lindhiem et al., 2019). The sample of parents/guardians reporting on their child’s anxiety symptoms was 63.7% female and 78.7% white. The mean age of the parents/guardians was 41.5 years (SD=10.6 years; Range=20–82 years). Approximately half of these parents/guardians were employed full-time (52.0%), 10.8% were employed part-time, 18.9% considered themselves homemakers, 14.9% were unemployed, retired, or disabled, and 2.0% were students. Approximately two-thirds (68.2%) were currently married, 15.5% were never married, and 11.3% were separated or divorced. Most parents/guardians (96.5%) completed high school or GED, 37.5% completed some college, 22.6% completed four years of college, and 14.3% completed post-graduate education. Median total family income over the previous year was $50,000-$59,999. Key demographic variables are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Information (N = 1,570)

| Child Age – M (SD) | 8.6 (2.4) |

| Child Sex (Female) | 46.8% |

| Child Race/Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 59.2% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11.2% |

| Hispanic | 18.5% |

| Other | 11.1% |

| Parent Age – M (SD) | 41.5 (10.6) |

| Parent Sex (Female) | 63.7% |

| Parent/Guardian Race | |

| White | 78.7% |

| Black or African American | 13.9% |

| Asian | 3.4% |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2.6% |

| Other | 6.1% |

| Parent/Guardian Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin | 16.2% |

| Mexican, Mexican American, Chicano | 7.6% |

| Puerto Rican | 3.1% |

| Other | 5.6% |

| Parent/Guardian Education | |

| High school or higher | 96.5% |

| Some college or higher | 74.4% |

| Marital Status – % Married | 68.2% |

| Family Income | |

| Less than $10,000 | 6.0% |

| $10,000 – $29,999 | 20.0% |

| $30,000 – $49,999 | 20.3% |

| $50,000 – $69,999 | 16.6% |

| $70,000 – $99,999 | 17.4% |

| $100,000 and above | 19.8% |

| US Region of Current Residence | |

| Northeast | 18.3% |

| Midwest | 24.3% |

| South | 37.0% |

| West | 20.4% |

Procedure

As part of the larger study, YouGov administered the SCARED-P and Pediatric Emotional Distress Scale (PEDS; Saylor et al., 1999) to a nationally representative sample of parents/guardians of children ages 5-12 years. YouGov is a survey company that uses a panel of over 1.2 million U.S. residents to administer online surveys. Participants on YouGov panels are recruited through internet advertising, email, partner contracts, random digit dialing, and mail using voter registration. Participants who respond to these recruitment efforts have agreed to be contacted to complete assessments for which they are relevant. YouGov has collected a large amount of demographic information from the panelists in prior surveys, thus data could be collected on a national sample that is representative of the U.S. population on key demographic variables (Lindhiem et al., 2019). Links to the survey were emailed to YouGov panelists. The response rate to the emailed survey link for this study was 52.8%. Participants received $25 in compensation for completing all questionnaires.

Measures

Each parent/guardian was asked to complete the 41-item SCARED-P (Birmaher et al., 1999), which assesses current symptoms of GAD, SAD, PD, SP, and SA using a 3-point Likert scale. The SCARED-P is a reliable and valid measure for assessing symptoms of anxiety in 8-19-year-olds (Birmaher et al., 1997, 1999).

The PEDS (Saylor et al., 1999) is a screening measure for youth exposed to trauma. The 21-item parent-report rating scale has three factors – Anxious/Withdrawn, Fearful, and Acting Out – that have good internal consistency and acceptable test-retest and interrater reliability (Saylor et al., 1999). Although this measure was not designed to screen for anxiety disorders, the Anxious/Withdrawn factor includes items that generally map on to anxiety, especially GAD, including “Seems worried,” “Complains about aches and pains,” and “Seems to be easily startled.” The Fearful factor includes items that map on to SAD, including “Refuses to sleep alone” and “Clings to adults/doesn’t want to be alone.” Thus, we hypothesized that the Fear factor would correlate most highly with the SCARED-P SAD subscale and the Anxious/Withdrawn factor would correlate most highly with the GAD subscale.

Analyses

Multivariate analyses of variance with Bonferroni adjustments and post-hoc tests were conducted to examine differences in SCARED-P scores by child age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Item frequencies, percentile scores, and internal consistency estimates (Cronbach α) were also calculated. Validity estimates were conducted using the PEDS, the only other measure of anxiety-related behaviors collected in the study.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using Mplus 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2018) to examine model fit for the five-factor model (five correlated factors). Differences in five-factor structure were examined by age bin (5-6, 7-8, 9-10, 11-12 years), a method consistent with prior work examining age differences in psychopathology (e.g., Merikangas et al., 2010), and by race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other). Although there are currently no widely agreed-upon rules for adequate sample size in CFA (Schmitt, 2011), our overall sample size fits widely-used rules of thumb (e.g., Gorsuch, 1983) and is more than three times the size of even the most conservative rules (e.g., Hatcher, 1994). Further, each age bin had an adequate sample size to fit these conservative guidelines (age 5-6: n=388; 7-8: n=331; 9-10: n=430; 11-12: n=421). An exploratory bifactor analysis was also conducted, following evidence supporting the bifactor model using the SCARED-C (DeSousa et al., 2014). In a bifactor model, the commonality of scale items is shared by the general factor and then the contribution of each item to distinct subfactors is calculated (Reise, 2012).

Full information maximum likelihood estimates were used, although there was no missing SCARED-P data. Four fit statistics were used to evaluate overall fit of each model: the chi-square (χ2) statistic, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). The CFI and TLI are incremental fit indices, assessing how much improvement the proposed model makes relative to the model with uncorrelated variables. The CFI and TLI range from 0 to 1, with values larger than .95 indicating acceptable model fit. RMSEA and SRMR are absolute fit indices. RMSEA values less than .08 indicate acceptable model fit. Generally, an SRMR less than .10 indicates acceptable fit, but it indicates good fit when less than .05.

Within the bifactor model, the factor loadings of the general (first) factor were compared with the loadings of the subsequent factors to determine the extent to which each item reflects the general factor versus a separate factor. Given that the SCARED was originally normed in a clinical sample of youth, the bifactor model was also run in a subset of the sample with SCARED-P total scores ≥25 to examine whether the general factor is diminished, and specific factors more pronounced, when restricted to youth with higher levels of anxiety.

Results

Mean raw SCARED-P subscales scores by age can be found in Figure 1; standard scores by age can be found in Figure 2. Percentile scores can be found in Tables 2 and 3. Approximately 12% of the sample had total scores at 25 or above (Table 4), which is considered the cut-off score warranting further clinical evaluation (Birmaher et al., 1999). The most frequently endorsed item was, “My child doesn’t like to be with people he/she doesn’t know well” (51.2%). The five items endorsed most frequently (>40%) were part of the SP or SAD subscales. The five items endorsed least frequently (<9%) were part of the PD subscale (Table 5).

Figure 1.

Mean levels of raw SCARED-P subscale scores by age group. Standard errors are represented in the figure by the error bars attached to each line. Note that maximum scores differ for each subscale (Generalized Anxiety = 18, Social Phobia = 14, Separation Anxiety = 16, Panic Disorder = 26, School Avoidance = 8).

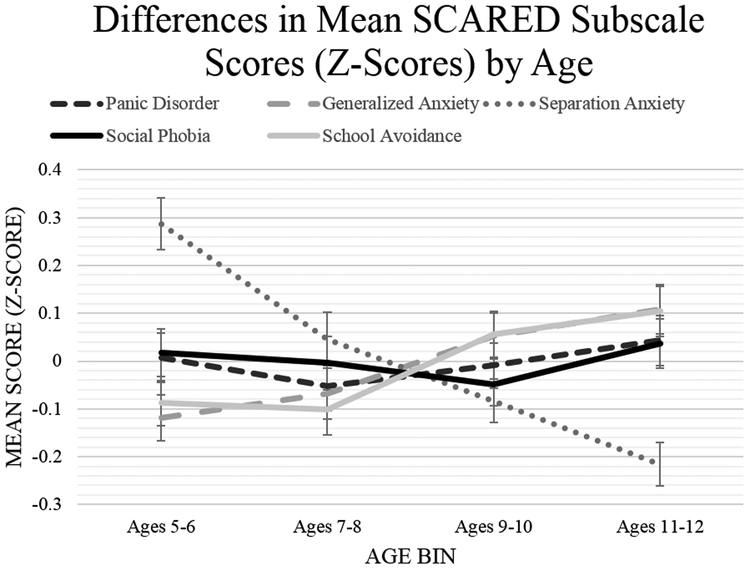

Figure 2.

Mean levels of SCARED-P standardized subscale scores by age group. Standard errors are represented in the figure by the error bars attached to each line.

Table 2.

Raw SCARED-P Total Score – Percentile Distribution by Age

| SCARED-P Total Scores | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentile | Full Sample (N = 1,570) |

Ages 5 – 8 (n = 719) |

Ages 9 – 12 (n = 851) |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 50 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 75 | 15 | 16 | 15 |

| 90 | 27 | 27 | 27 |

| 95 | 38 | 37 | 38 |

| 98 | 44 | 43 | 47 |

| 99 | 54 | 47 | 55 |

Note. Maximum Total Score = 82.

Table 3.

Raw SCARED-P Subscale Scores – Percentile Distributions (Full Sample)

| SCARED-P Subscale Scores (Full Sample) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentile | Generalized Anxiety |

Social Phobia | Separation Anxiety |

Panic Disorder/ Somatic Symptoms |

School Avoidance |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 50 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 75 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 90 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 3 |

| 95 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 4 |

| 98 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 14 | 5 |

| 99 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 17 | 6 |

Note. Maximum Scores: Generalized anxiety = 18, Social phobia = 14, Separation anxiety = 16, Panic Disorder/Somatic Symptoms = 26, School Avoidance = 8.

Table 4.

Percentage of Youths above SCARED-P Clinical Cutoff

|

Age group (years) |

% ≥25 on SCARED-P Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | |

| 5-6 | 13.66% | 16.33% | 10.94% |

| 7-8 | 9.97% | 8.33% | 11.92% |

| 9-10 | 11.86% | 9.64% | 14.92% |

| 11-12 | 12.83% | 14.29% | 11.37% |

| Total | 12.17% | 12.10% | 12.24% |

Table 5.

SCARED-P Item Frequencies (% of participants endorsing each item)

| Item (subscale) | % |

|---|---|

| My child doesn’t like to be with people he/she doesn’t know well. (SP) | 51.2 |

| My child feels shy with people he/she doesn’t know well. (SP) | 47.8 |

| My child doesn’t like to be away from his/her family. (SAD) | 43.6 |

| My child follows me wherever I go. (SAD) | 43.3 |

| My child is shy. (SP) | 43.3 |

| My child worries about other people liking him/her. (GAD) | 40.6 |

| It is hard for my child to talk with people he/she doesn’t know well. (SP) | 39.1 |

| My child feels nervous with people he/she doesn’t know well. (SP) | 37.4 |

| My child worries about how well he/she does things. (GAD) | 37.4 |

| My child is afraid to be alone in the house. (SAD) | 37.2 |

| When my child gets frightened, his/her heart beats fast. (PD) | 30.8 |

| My child feels nervous when he/she is with other children or adults and he/she has to do something while they watch him/her. (SP) | 30.0 |

| My child worries about being as good as other kids. (GAD) | 28.4 |

| My child is a worrier. (GAD) | 27.8 |

| My child is nervous. (GAD) | 27.5 |

| My child feels nervous when he/she is going to parties, dances, or any place where there will be people that he/she doesn’t know well. (SP) | 27.5 |

| My child worries that something bad might happen to his/her parents. (SAD) | 26.8 |

| My child worries about sleeping alone. (SAD) | 26.5 |

| My child gets scared if he/she sleeps away from home. (SAD) | 26.1 |

| My child worries about things working out for him/her. (GAD) | 24.5 |

| My child worries about what is going to happen in the future. (GAD) | 23.6 |

| My child worries about things that have already happened. (GAD) | 21.3 |

| My child gets headaches when he/she is at school. (SA) | 20.4 |

| My child has nightmares about something bad happening to him/her. (SAD) | 18.9 |

| My child worries about going to school. (SA) | 18.6 |

| My child gets stomachaches at school. (SA) | 16.6 |

| My child has nightmares about something bad happening to his/her parents. (SAD) | 16.6 |

| When my child feels frightened, it is hard for him/her to breathe. (PD) | 12.3 |

| My child gets really frightened for no reason at all. (PD) | 12.1 |

| When my child gets frightened, he/she feels like throwing up. (PD) | 10.6 |

| People tell me that my child worries too much. (GAD) | 9.8 |

| My child is afraid of having anxiety (or panic) attacks. (PD) | 9.7 |

| My child is scared to go to school. (SA) | 9.6 |

| When my child gets frightened, he/she feels like things are not real. (PD) | 9.3 |

| When my child gets frightened, he/she feels like he/she is going crazy. (PD) | 8.3 |

| When my child gets frightened, he/she sweats a lot. (PD) | 8.3 |

| My child gets shaky. (PD) | 8.1 |

| When my child gets frightened, he/she feels like passing out. (PD) | 7.5 |

| People tell me that my child looks nervous. (PD) | 7.4 |

| When my child gets frightened, he/she feels like he/she is choking. (PD) | 7.4 |

| When my child gets frightened, he/she feels dizzy. (PD) | 6.9 |

Note. SP=social phobia; GAD=generalized anxiety; SA=school avoidance; PD=panic disorder; SAD=separation anxiety.

For the multivariate analyses of variance, no significant two- or three-way interactions between age group, sex, and child race/ethnicity were found on SCARED-P total score or subscale scores (Wilks’ Λ=.96-.99, ps>.05). However, main effects of age group, sex, and race/ethnicity were found (ps<.001). Collapsing across gender and race/ethnicity, significant differences by age group were found for the SCARED-P GAD subscale (F(3,1569)=6.38, p<.001), SAD subscale (F(3,1569)=8.24, p<.001), and SA subscale (F(3, 1569)=5.03, p=.002). Post-hoc pair-wise comparison tests with Bonferroni corrections revealed significantly higher levels of parent-reported GAD scores in youth ages 11-12 compared to youth ages 5-6 (p=.009). Youth ages 7-8, 9-10, and 11-12 had significantly lower levels of parent-reported SAD scores compared to youth ages 5-6 (ps≤.008), and youth ages 11-12 had significantly lower levels of parent-reported SAD scores compared to youth ages 7-8 (p=.001). Finally, youth ages 11-12 showed significantly higher levels of parent-reported SA scores compared to youth ages 5-6 (p=.039) and youth ages 7-8 (p=.032). Collapsing across age group and race, parents/guardians reported significantly higher scores on the SP subscale scores for females than males (F(1,1569)=14.60, p<.001). Scores on all other subscales and the total score were not significantly different for females and males. Collapsing across age group and sex, post-hoc pair-wise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections revealed no significant differences by race/ethnicity for any SCARED-P subscale or total score (ps>.120), despite the significant main effect of race/ethnicity.

Reliability

Across the entire sample, the internal consistency of the total score was high (Cronbach α=0.95). Internal consistencies of the subscale scores were also good: SP (α=.87), GAD (α=.87), SAD (α=.80), PD (α=.93), SA (α=.76).

Internal consistency in younger and older children was also compared. In youth ages 5-8 years, reliability was good: SCARED-P total (α=0.95), GAD (α=.87), SAD (α=.79), SP (α=.88), PD (α=.93), SA (α=.79). In youth ages 9-12, reliability was very comparable: SCARED-P total (α=0.95), GAD (α=.88), SAD (α=.80), SP (α=.87), PD (α=.93), SA (α=.73).

Convergent Validity

The PEDS Fear scale correlated significantly with the SCARED-P total score (r=.65, p<.001) and all subscale scores (rs=.38-.70, ps<.001), and correlated most strongly with the SAD subscale (r=.70, p<.001). The PEDS Anxious/Withdrawn scale correlated significantly with the SCARED-P total score (r=.76, p<.001) and all subscale scores (rs=.44-.77, ps<.001), but correlated more strongly with the PD subscale (r=.77, p<.001) than the GAD subscale (r=.67, p<.001). Correlations were almost identical in older children (ages 9-12) and younger children (ages 5-8).

Factor Analysis

Five-factor model.

Overall, the five-factor model did not provide a good fit for this data (Table 6). Although the SRMR for the multigroup CFA was acceptable (.07), the CFI (0.80), TLI (.78), and RMSEA (.08) were below the conventional cut-offs for good model fit. Subsequent investigation suggested that the hypothesized factor structure was not a good fit for any of the age bins, thus model fit was poor for older children as well as younger children. Model fit did not improve when including only the 12% of the sample with SCARED total scores ≥25 (χ2(df)=1598(769), CFI=0.67, TLI=0.65, RMSEA=0.08, SRMR=0.09).

Table 6.

Five-Factor Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) – Age Differences

| Age Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fit Statistic | 5-6 (n=388) |

7-8 (n=331) |

9-10 (n=430) |

11-12 (n=421) |

Multi-Group CFA (Configural Model) |

| χ2 (df) | 2573 (769)** | 2628 (769)** | 2567 (769)** | 3102 (769)** | 10872 (3076)** |

| RMSEA | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| CFI | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.80 |

| TLI | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.78 |

| SRMR | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

Note. χ2 = Chi-Square; df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual.

p<.001 (significant χ2 values indicate poor model fit).

We also tested whether the five-factor structure of the SCARED-P differed by race/ethnicity (Table 7). Omnibus testing suggested that the hypothesized five-factor structure did not fit across racial/ethnic groups as a whole (multigroup CFA χ2(df)=10773(769), CFI=.80, TLI=.78, RMSEA=.08, SRMR=.07). Results suggested that the hypothesized structure may perform slightly better for Non-Hispanic Whites (χ2(df)=3984(769), CFI=.84, TLI=.83, RMSEA=.07, SRMR=.06) than other racial groups; however, the model still falls short of conventional model fit indices.

Table 7.

Five-Factor Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) – Race/Ethnicity Differences

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fit Statistic |

Non-Hispanic White (n=927) |

Non-Hispanic Black (n=175) |

Hispanic (n=290) |

Other (n=173) |

Multi-Group CFA (Configural Model) |

| χ2 (df) | 3984 (769)** | 2299 (769)** | 2485 (769)** | 2006 (769)** | 10774 (3076)** |

| RMSEA | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| CFI | 0.84 | 0.72 | 0.77 | 0.74 | 0.80 |

| TLI | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.78 |

| SRMR | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

Note. χ2 = Chi-Square; df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual.

p<.001 (significant χ2 values indicate poor model fit).

Bifactor model.

In the full sample, the exploratory bifactor model revealed a strong eigenvalue of the first factor (15.28) relative to subsequent factors (2nd factor=3.31, 3rd=1.75, 4th=1.54, 5th=0.99, 6th=0.96), with strong loadings of almost all items on the general factor that made extracting specific factors quantitatively dubious.

In youth with clinically significant anxiety (i.e., SCARED-P total scores ≥25), the general factor was diminished (eigenvalue of the 1st factor=8.50, 2nd=3.80, 3rd=2.30, 4th=2.10, 5th=1.49, 6th=1.43). In this subsample, items appeared to factor more appropriately into five factors, though model fit was still poor for this bifactor model with five group factors (χ2(df)=1065.6(625), CFI=.82, TLI=.77, RMSEA=.05, SRMR=.06) and only two factors – a separation anxiety factor and social anxiety factor – resembled the original SCARED factors. The other three factors included intermixed GAD, PD, and SA items.

Discussion

This study examined mean levels of SCARED-P scores in a nationally representative sample of U.S. children ages 5-12 and is the first to examine the SCARED-P in children as young as 5. Results provide insight into normative levels of parent-reported anxiety in the U.S. population of children. Around 12% of youth had SCARED-P scores above the clinical cut-off (Birmaher et al., 1999), which falls in the range (~3-15%) of the estimated prevalence of anxiety disorders in 5-10-year-olds (Cartwright-Hatton, McNicol, & Doubleday, 2006).

As hypothesized, mean levels of parent-reported scores on the separation anxiety subscale tended to decrease from age 5 to 12, while mean levels of scores on the generalized anxiety subscale and school avoidance subscale tended to increase. This aligns with prior work using the SCARED (e.g., Hale et al., 2005; Isolan et al., 2011). Mean scores on the school avoidance subscale were generally low, which could reflect the limited number of items on this subscale (n=4) but could also reflect relatively low rates of school refusal, with only around 1-5% of school-age children engaging in school refusal (Burke & Silverman, 1987; King & Bernstein, 2001). Further, school avoidance often reflects other anxiety symptoms, such as separation anxiety, social anxiety, or generalized anxiety (King & Bernstein, 2001). Interestingly, in the current sample, standard scores on the school avoidance subscale appeared to track closely with standard scores on the generalized anxiety subscale across ages (Figure 2). This may be because several of the items on the school avoidance subscale can also be seen as symptoms of GAD. For example, one SA item, “My child worries about going to school,” could represent a worry associated with GAD. Additionally, two SA subscale items ask about stomachaches and headaches, two common physical symptoms associated with GAD.

The most frequently endorsed items on the SCARED-P were part of the social and separation anxiety subscales, while the least frequently endorsed items were part of the panic disorder subscale. This is not surprising, given that concerns with peers are prominent in childhood, especially late childhood, and that the median age-of-onset for separation anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder is around age 7 and 13, respectively, while the median age-of-onset for panic disorder is around age 24 (Kessler et al., 2005). Interestingly, the most frequently endorsed item (“My child doesn’t like to be with people he/she doesn’t know well”) was the same item endorsed most frequently by a sample of 111 African-American adolescents (Boyd et al., 2003). As hypothesized, parents/guardians also reported more symptoms on the social phobia subscale for females than males. Although sex differences in rates of social anxiety disorder tend to appear around age 13 (Bittner et al., 2007), work with community samples and previous work validating the SCARED suggests that preadolescent and adolescent females report more symptoms of social anxiety than males (Spence, 1997; Isolan et al., 2011; Hale et al., 2005; Su et al., 2008; Hale et al., 2011). Finally, mean SCARED-P total score and subscale scores did not differ by race/ethnicity when correcting for multiple comparisons, which aligns with prior work (Hale et al., 2005).

Confirmatory factor analysis suggested that the hypothesized five-factor structure of the SCARED-P was not a good fit for the data across the full sample or for any of the age or race/ethnicity groups. The nearly identical poor fit across age groups could argue that the structure of anxiety does not change dramatically between ages 5 and 12, and also suggests that the SCARED-P is not necessarily more valid for children over age 8 than under age 8. Findings may reflect the absence of a five-factor structure of anxiety in younger children. Alternatively, a five-factor structure of anxiety in younger children could exist, but these factors may look different from the factors that can be tested using the SCARED-P items, as this measure was originally created for an older age group. Notably, poor model fit in the current study might also be specific to parent-reported anxiety, and a significant limitation of the current study was that we did not collect child self-reports of anxiety. Though it was beyond the scope of this brief report to test alternative models using EFA (with the exception of the bifactor analysis), researchers should note that while the five-factor structure is most widely-used and well-replicated, some prior work has found support for a three-factor solution (Boyd et al., 2003) or four-factor solution (Muris et al., 2002; Ogliari et al., 2006; Wren et al., 2007) to the SCARED.

Although SCARED-P model fit was poor across ages, the five factors had good internal consistency across ages (α=.76-.93). In addition, the five factors significantly correlated with fear and anxiety factors from the PEDS in both younger children (5-8 years) and older children (9-12 years). As hypothesized, the PEDS Fear subscale correlated most strongly with the SCARED-P SAD subscale. Unexpectedly, the PEDS Anxious/Withdrawn subscale correlated most strongly with the PD subscale, although it also correlated strongly with the GAD subscale. Both the PD subscale and PEDS Anxious/Withdrawn subscale include items that address physiological symptoms associated with anxiety, which could help explain the high correlation. Notably, the PEDS Fear scale and the PEDS Anxious/Withdrawn scale correlated significantly with all SCARED-P subscale scores, which could support current interpretations that either the SCARED-P is not well suited to differentiate anxiety subtypes in young children or anxiety subtypes are not well-differentiated in young children. Although the PEDS was not designed to screen for anxiety disorders, these results provide some support for the reliability and convergent validity of the SCARED-P in children as young as 5-years-old.

Interestingly, the exploratory bifactor analysis strongly suggested that the SCARED-P is a good indicator of clinically significant distress broadly speaking. This was indicated by the strong eigenvalue of the first factor relative to subsequent factors and the strong loadings of majority of the items on the general factor. That the general factor was diminished when analyses were limited to only those with clinically significant symptoms further supports this conclusion. This aligns with results from a previous bifactor analysis of the SCARED using a sample of 2420 9-18-year-olds in Brazil (DeSousa et al., 2014). DeSousa et al. (2014) found that after controlling for the common variance of the general factor (almost 64%), SCARED subscale scores provided little reliable information. The SCARED is a widely used measure of childhood anxiety and this is likely to remain the case; that said, it is important for investigators to be aware that the hypothesized subscales in the SCARED may not be empirically distinguished, especially for ages 5-12.

Findings also converge with what is known about normative clustering of anxiety symptoms in younger children outside the domain of the SCARED. For example, findings are comparable to prior work examining the structure of anxiety symptoms in a community sample of 698 8-12-year-olds using the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (Spence, 1997). Although Spence (1997) found support for a six-factor model of anxiety (reflecting panic, social anxiety, separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, obsessive-compulsive problems, and physical fears), the model with the best fit included a higher order anxiety factor. Further, the percentage of variance unique to the first-order factors was relatively small (7-34%), suggesting that the largest proportion of variance in anxiety symptoms in this sample was attributable to a higher order anxiety factor. Additionally, intercorrelations between first-order factors were higher for younger children than older children, suggesting that anxiety subtypes may become more differentiated with age. Even among clinical samples of youth with anxiety disorders, research has shown a considerable degree of fluctuation in the diagnostic status of the specific anxiety disorder examined in young ages (Beesdo, Knappe, & Pine, 2009). Further, there is substantial inter-anxiety comorbidity in youth, with significant associations between almost all anxiety disorders (Beesdo, Knappe, & Pine, 2009). Generally, current findings fit with prior research indicating that specific subtypes of anxiety may not be well-differentiated in young children. Nonetheless, research suggests that anxiety symptoms in general can be reliably measured in children as young as 5 years of age (Snyder et al., 2009), and the SCARED-P may be a useful instrument for broadly measuring these symptoms.

Results also fit in with what is known about normative levels of anxiety in younger children. Although it may seem surprising that more 5-6-year-olds had total SCARED-P total scores above threshold than any other age group, this is consistent with what is known about changes in normative anxiety levels during early childhood. Longitudinal research with community samples of early school-age children suggests that normative levels of anxiety symptoms actually decrease over development (e.g., Cooper-Vince, Chan, Pincus, & Comer, 2014; Keenan, Feng, Hipwell, & Klostermann, 2009; Kertz, Sylvester, Tillman, & Luby, 2018). Kertz et al. (2018) recently found that almost 65% of their sample showed linear declines in anxiety symptoms between the ages of 5 and 12 years. Additionally, the high percentage of 5-6-year-olds above threshold on the SCARED-P (14%) may be driven by high scores on the separation anxiety subscale, which is unsurprising given that normative levels of separation anxiety have been found to decrease between the ages of 6 and 12 years (Keenan et al., 2009). It should also be noted that we did not collect any data on impairment of anxiety symptoms. Thus, it is impossible to say what percentage of 5-6-year-olds with SCARED-P scores above threshold would actually be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. Though mean levels of anxiety might decline over this 5-12-year period, there also appears to be significant variability in individual trajectories, especially for younger children (e.g., Kertz et al. 2018; Feng, Shaw, & Silk, 2008; Broeren, Muris, Diamantopoulou, & Baker, 2013). This variability, with symptoms often remitting over time, could also support the interpretation that anxiety subtypes are not well-differentiated in this age group. While current results may broadly align with longitudinal work, the current study was cross-sectional, thus we cannot speak to within-person changes in SCARED-P scores across early childhood.

Additional study limitations are worth noting. First, although we report mean levels of the five SCARED-P subscales, readers should be mindful that these five subscales were not empirically distinguished. Additionally, no data were collected on clinical diagnoses in this sample; thus, it is impossible to know how many youths were diagnosed with anxiety disorders and how the SCARED might function differently for youth with anxiety disorders. Finally, we constrained analyses to two forms of factor analysis: CFA and bifactor analysis. We chose to fit our data to a bifactor model as an exploratory analysis in response to prior work showing support for this model of the SCARED (DeSousa et al., 2014). Researchers have noted that bifactor models tend to overfit to data (Bonifay & Cai, 2017; Reise, Kim, Mansolf, & Widaman, 2016). Yet, the bifactor approach for understanding the psychometrics of an assessment scale is useful in providing estimates of the extent to which a given set of items measures a general domain as well as distinct sub-domains (e.g., distinct domains of anxiety) (Reise, Moore, & Haviland, 2010; Rodriguez, Reise, & Haviland, 2016). The purpose of these analyses was not to demonstrate psychometric superiority of a bifactor scoring approach to the SCARED, but rather to highlight the relatively poor specific factor loadings. Indeed, in keeping with best practice (e.g., Bonifay, Lane, & Reise, 2017), we did not highlight any particular model based upon model fit alone.

Overall, this brief report provides insight into what may be considered normative levels of parent-reported anxiety in a nationally representative sample of 5-12-year-olds living across the United States. The data presented in this brief report may be useful for clinicians who are trying to determine whether a child’s level of total anxiety is normative. Findings support use of the SCARED-P in children under age 8, though caution should be paid when interpreting subscale scores.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by NICHD grant R21HD090145 awarded to O.L.

Footnotes

The authors declare they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K, Knappe S, & Pine DS (2009). Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatric Clinics, 32(3), 483–524. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, Cully M, Balach L, Kaufman J, & Neer SM (1997). The screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): Scale construction and psychometric characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(4), 545–553. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, & Baugher M (1999). Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a replication study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(10), 1230–1236. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifay W, & Cai L (2017). On the complexity of item response theory models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 52(4), 465–484. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2017.1309262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifay W, Lane SP, & Reise SP (2017). Three concerns with applying a bifactor model as a structure of psychopathology. Clinical Psychological Science, 5(1), 184–186. doi: 10.1177/2167702616657069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd RC, Ginsburg GS, Lambert SF, Cooley MR, & Campbell KD (2003). Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): psychometric properties in an African-American parochial high school sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(10), 1188–1196. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200310000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broeren S, Muris P, Diamantopoulou S, & Baker JR (2013). The course of childhood anxiety symptoms: Developmental trajectories and child-related factors in normal children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(1), 81–95. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9669-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke AE, & Silverman WK (1987). The prescriptive treatment of school refusal. Clinical Psychology Review, 7(4), 353–362. 10.1016/0272-7358(87)90016-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright-Hatton S, McNicol K, & Doubleday E (2006). Anxiety in a neglected population: Prevalence of anxiety disorders in pre-adolescent children. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(7), 817–833. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Vince CE, Chan PT, Pincus DB, & Comer JS (2014). Paternal autonomy restriction, neighborhood safety, and child anxiety trajectory in community youth. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35(4), 265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti E, Hale WW III, Fermani A, Raaijmakers Q, & Meeus W (2009). Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) in the general Italian adolescent population: A validation and a comparison between Italy and The Netherlands. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(6), 824–829. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSousa DA, Zibetti MR, Trentini CM, Koller SH, Manfro GG, & Salum GA (2014). Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders: Are subscale scores reliable? A bifactor model analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(8), 966–970. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Shaw DS, & Silk JS (2008). Developmental trajectories of anxiety symptoms among boys across early and middle childhood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(1), 32. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch RL (1983). Factor analysis (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Hale WW, Crocetti E, Raaijmakers QA, & Meeus WH (2011). A meta-analysis of the cross-cultural psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(1), 80–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale WW, Raaijmakers Q, Muris P, & Meeus WIM (2005). Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) in the general adolescent population. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(3), 283–290. doi: 10.1007/s10578-015-0589-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher L (1994). A Step-by-Step Approach to Using the SAS® System for Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Isolan L, Salum GA, Osowski AT, Amaro E, & Manfro GG (2011). Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) in Brazilian children and adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(5), 741–748. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao UMA, Flynn C, Moreci P, … & Ryan N (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Feng X, Hipwell A, & Klostermann S (2009). Depression begets depression: Comparing the predictive utility of depression and anxiety symptoms to later depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(9), 1167–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02080.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertz SJ, Sylvester C, Tillman R, & Luby JL (2017). Latent class profiles of anxiety symptom trajectories from preschool through school age. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2017.1295380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King NJ, & Bernstein GA (2001). School refusal in children and adolescents: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(2), 197–205. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200102000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley AK, Bergman RL, McCracken J, & Piacentini JC (2004). Impairment in childhood anxiety disorders: Preliminary examination of the child anxiety impact scale–parent version. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 14(1), 105–114. 10.1089/104454604773840544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhiem O, Vaughn-Coaxum RA, Higa J, Harris JL, Kolko DJ, & Pilkonis PA (2019). Development and validation of the Knowledge of Effective Parenting Test (KEPT) in a Nationally Representative Sample. Psychological Assessment. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/pas0000699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, … & Swendsen J (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Dreessen L, Bögels S, Weckx M, & van Melick M (2004). A questionnaire for screening a broad range of DSM-defined anxiety disorder symptoms in clinically referred children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 813–820. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Merckelbach H, Kindt M, Bögels S, Dreessen L, van Dorp C, … & Snieder N (2001). The utility of Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) as a tool for identifying children at high risk for prevalent anxiety disorders. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 14, 265–283. 10.1080/10615800108248357 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Merckelbach H, Ollendick T, King N, & Bogie N (2002). Three traditional and three new childhood anxiety questionnaires: Their reliability and validity in a normal adolescent sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(7), 753–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Merckelbach H, Van Brakel A, & Mayer AB (1999). The revised version of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED-R): further evidence for its reliability and validity. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 12(4), 411–425. doi: 10.1080/10615809908249319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén B (2015). Mplus. The comprehensive modelling program for applied researchers: user’s guide, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Myers K, & Winters NC (2002). Ten-year review of rating scales. II: Scales for internalizing disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(6), 634–659. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, & Ma Y (1998). The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of general psychiatry, 55(1), 56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP (2012). The rediscovery of bifactor measurement models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 47(5), 667–696. 10.1080/00273171.2012.715555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Kim DS, Mansolf M, & Widaman KF (2016). Is the bifactor model a better model or is it just better at modeling implausible responses? Application of iteratively reweighted least squares to the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 51(6), 818–838. 10.1080/00273171.2016.1243461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Moore TM, & Haviland MG (2010). Bifactor models and rotations: Exploring the extent to which multidimensional data yield univocal scale scores. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92, 544–559. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2010.496477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A, Reise SP, & Haviland MG (2016a). Applying bifactor statistical indices in the evaluation of psycho- logical measures. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98, 223–237. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2015.1089249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor CF, Swenson CC, Stokes Reynolds S, & Taylor M (1999). The Pediatric Emotional Distress Scale: A brief screening measure for young children exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 28(1), 70–81. 10.1207/s15374424jccp2801_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt TA (2011). Current methodological considerations in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 29(4), 304–321. 10.1177/0734282911406653 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Bullard L, Wagener A, Leong PK, Snyder J, & Jenkins M (2009). Childhood anxiety and depressive symptoms: Trajectories, relationship, and association with subsequent depression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38(6), 837–849. doi: 10.1080/15374410903258959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence SH (1997). Structure of anxiety symptoms among children: a confirmatory factor-analytic study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(2), 280 10.1037/0021-843X.106.2.280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L, Wang K, Fan F, Su Y, & Gao X (2008). Reliability and validity of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED) in Chinese children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(4), 612–621. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wren FJ, Berg EA, Heiden LA, Kinnamon CJ, Ohlson LA, Bridge JA, … & Bernal MP (2007). Childhood anxiety in a diverse primary care population: parent-child reports, ethnicity and SCARED factor structure. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(3), 332–340. 10.1097/chi.0b013e31802f1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]