Mushrooms are sources of food and medicine and provide abundant nutrients and bioactive compounds. However, most of the edible mushrooms cannot be cultivated commercially due to the limited understanding of basidioma development. From winter mushroom (Flammulina velutipes; also known as Enokitake), one of the most commonly cultivated mushrooms, we identified a novel transcription factor, PDD1, positively regulating basidioma development. PDD1 increases expression during basidioma development. Artificially increasing its expression promoted basidioma formation and dramatically increased mushroom yield, while reducing its expression dramatically impaired its development. In its PDD1 overexpression mutants, mushroom number, height, yield, and biological efficiency were significantly increased. PDD1 regulates the expression of some genes that are important in or related to basidioma development. PDD1 is the first identified transcription factor with defined functions in mushroom development among commercially cultivated mushroom species, and it might be useful in mushroom breeding.

KEYWORDS: sexual development, HMG-box, basidioma, Flammulina velutipes

ABSTRACT

Most of the edible mushrooms cannot be cultivated or have low yield under industrial conditions, partially due to the lack of knowledge on how basidioma (fruiting body) development is regulated. From winter mushroom (Flammulina velutipes), one of the most popular industrially cultivated mushrooms, a transcription factor, PDD1, with a high-mobility group (HMG)-box domain was identified based on its increased transcription during basidioma development. pdd1 knockdown by RNA interference affected vegetative growth and dramatically impaired basidioma development. A strain with an 89.9% reduction in the level of pdd1 transcription failed to produce primordia, while overexpression of pdd1 promoted basidioma development. When the transcriptional level of pdd1 was increased to 5 times the base level, the mushroom cultivation time was shortened by 9.8% and the yield was increased by at least 33%. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis revealed that pdd1 knockdown downregulated 331 genes and upregulated 463 genes. PDD1 positively regulated several genes related to fruiting, including 6 pheromone receptor-encoding genes, 3 jacalin-related lectin-encoding genes, FVFD16, and 2 FVFD16 homolog-encoding genes. PDD1 is a novel transcription factor with regulatory function in basidioma development found in industrially cultivated mushrooms. Since its orthologs are widely present in fungal species of the Basidiomycota phylum, PDD1 might have important application prospects in mushroom breeding.

IMPORTANCE Mushrooms are sources of food and medicine and provide abundant nutrients and bioactive compounds. However, most of the edible mushrooms cannot be cultivated commercially due to the limited understanding of basidioma development. From winter mushroom (Flammulina velutipes; also known as Enokitake), one of the most commonly cultivated mushrooms, we identified a novel transcription factor, PDD1, positively regulating basidioma development. PDD1 increases expression during basidioma development. Artificially increasing its expression promoted basidioma formation and dramatically increased mushroom yield, while reducing its expression dramatically impaired its development. In its PDD1 overexpression mutants, mushroom number, height, yield, and biological efficiency were significantly increased. PDD1 regulates the expression of some genes that are important in or related to basidioma development. PDD1 is the first identified transcription factor with defined functions in mushroom development among commercially cultivated mushroom species, and it might be useful in mushroom breeding.

INTRODUCTION

Basidiomata (fruiting bodies) of many fungi in the Basidiomycota phylum have long been used as foods due to their desirable taste and rich nutrient content. Some species are also capable of producing secondary metabolites with special biological activities, such as antitumor or immunomodulating activities, and are also medicine sources (1, 2). However, among about 2,300 edible fungal species, only 100 are industrially cultivated (3, 4), mainly due to the lack of sufficient knowledge on the requirements of basidioma development.

The major understanding of mechanisms of basidioma development was obtained from studies in two model species, Schizophyllum commune and Coprinopsis cinerea, from which several important transcription factors regulating basidioma development were identified. Some transcription factors regulate early events of basidioma development (5, 6). For example, inactivation of S. commune c2h2, encoding a transcription factor with a Cys2His2 zinc finger domain, resulted in the arrest of dikaryotic hyphae at the aggregation stage (7). Several transcription factors, including hom2 (encoding a transcription factor with a homeodomain), bri1 (encoding a protein with a Bright DNA-binding domain), fst4 (encoding a zinc finger transcription factor), and the WC-1–WC-2 blue light receptor complex in S. commune, are required for the initiation of basidioma development, and their deletion resulted in the loss of basidioma formation (7, 8). The late stages of basidioma development are regulated by several other transcription factors. For example, deletion of fst3 (encoding a zinc finger transcription factor), gat1 (encoding a transcription factors with a GATA-type zinc finger domain), or hom1 (encoding a transcription factor with a homeodomain) in S. commune increased mushroom numbers but reduced the basidioma size (7, 8). All of the findings described above promote a certain degree of understanding of an elaborate regulatory network in basidioma development.

However, the knowledge on mechanisms of basidioma development in nonmodel mushrooms is very limited, especially in commercially cultivated species, such as Flammulina velutipes, Lentinula edodes, Pleurotus spp., Auricularia spp., and Agaricus bisporus, which together supply around 85% of the world’s edible mushrooms (9). These cultivated mushrooms differ from the model species in phylogeny, culture conditions, and hereditary properties (10–14). In addition, although homologs of the transcription factors mentioned above are present in the commercially cultivated mushroom species, on the basis of our analysis of published transcriptomic data (5, 6), most of their expression patterns are different from those of their homologs in the two model mushrooms, in which their expression levels correlate with the fruiting process. For example, the homologs of fst4 and bri1 in F. velutipes did not show transcriptional increases in primordia and mature basidiomata relative to the vegetative growth stage, as shown previously in S. commune (8). In S. commune, fst3, hom2, c2h2, and gat1 showed increased levels of transcription in primordia and mature basidiomata compared to the vegetative growth stage (8), but genes encoding their homologs in F. velutipes exhibited decreased transcription in those stages (15, 16). This indicates that different transcriptional regulatory networks of basidioma development might exist in the commercially cultivated mushrooms.

Winter mushroom (F. velutipes; also known as golden needle mushroom or Enokitake) is one of the most widely industrially cultivated mushrooms in the world; it has enormous economic benefits and produces secondary metabolites with health promotion functions (17–20). F. velutipes has a simple life cycle, with both vegetative growth and basidioma development stages as seen with other dikaryotic fungi of the Basidiomycota phylum (13). Due to its convenient conditions for basidioma induction, the availability of complete genome sequence and transcriptomic data at different developmental stages, and its mature genetic manipulation methods (21–24), F. velutipes has been regarded as a model for decoding the mechanisms of basidioma development in cultivated mushrooms (21).

In this study, by screening F. velutipes transcriptomic data and following genetic approaches, we identified the transcription factor PDD1, a high-mobility group (HMG)-box-containing protein, as a newly recognized regulator of basidioma development.

RESULTS

pdd1 increases expression during basidioma development.

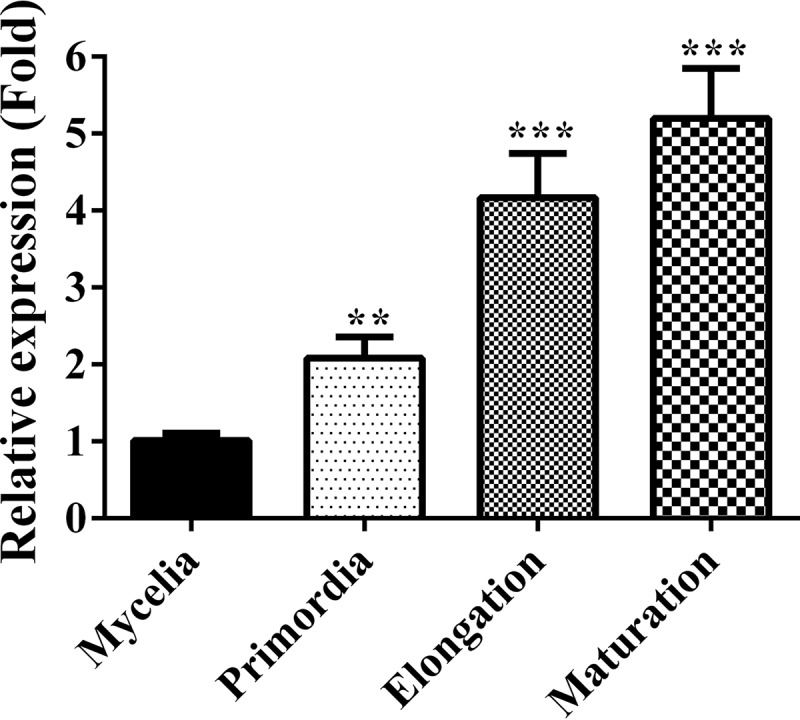

To find transcription factors that regulate basidioma development in F. velutipes, transcripts in mycelia at the vegetative growth stage, in primordia, in elongating basidiomata, and in mature basidiomata were analyzed by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) (15, 16). The transcriptional profile of a particular gene, namely, gene 3188, attracted our attention. We renamed gene 3188 pdd1 (primordia development defect 1) (GenBank accession no. MG264427) based on the phenotype of its knockdown mutants (see below). The transcriptional level of pdd1 in primordia was significantly higher than that in mycelia at the vegetative growth stage and continuously increased with basidioma development. This expression pattern was confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 1, pdd1 transcriptional levels in primordia, elongating basidiomata, and mature basidiomata were 2-fold (P = 0.0027, n = 3), 4-fold (P = 0.0007, n = 3), and 5-fold (P = 0.0004, n = 3) that in mycelia at the vegetative growth stage, respectively. This transcriptional profile suggests that PDD1 might play a role in basidioma development.

FIG 1.

Transcript levels of pdd1 at different development stages in the wild type (F19). RNA was extracted from the vegetative mycelia growing in composted sawdust substrate, from primordia, from basidiomata at the elongation stage, and from the basidiomata at maturation stage. The transcript levels of pdd1 were measured by qPCR and normalized to the transcript level of the β-actin gene. The expression level of pdd1 at each stage was calculated relative to the transcript level of pdd1 at the mycelial growth stage according to the 2−ΔΔCT method. Results shown are means of three biological replicates. Standard deviations are indicated with error bars. The significant levels were calculated by t test and are marked as follows: *, 0.01 < P < 0.05; **, 0.001 < P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001. Pprimordia = 0.0027, n = 3; Pelongation basidiomata = 0.0007, n = 3; Pmature basidiomata = 0.0004, n = 3.

Structure and phylogenetic analysis of the PDD1 protein.

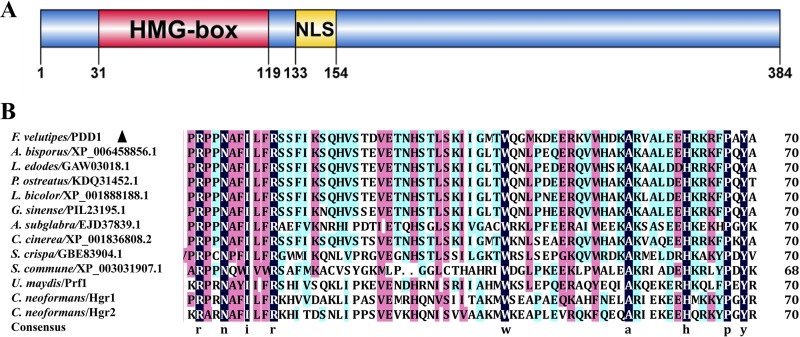

The coding sequence of the pdd1 gene is 1,204 bp, containing an open reading frame of 1,155 bp, interrupted by one intron of 49 bp (see File S1 in the supplemental material) and encodes a protein with 384 amino acid residues (File S2). Domain prediction performed with SMART (25, 26) showed that the PDD1 protein has only one functional domain, the HMG-box DNA-binding domain (SM000398). A nuclear localization signal (NLS) was found in PDD1 based on cNLS Mapper analysis (27) (Fig. 2A). The existence of both the HMG-box domain and the NLS indicates that PDD1 is probably a transcription factor.

FIG 2.

PDD1 domain organization and sequence conservation in the HMG-box domain regions among PDD1 orthologs. (A) Domain organization of PDD1 protein. A HMG-box domain and a nuclear localization signal (NLS) were predicted in PDD1 protein by SMART (25, 26) and cNLS Mapper (27), respectively. (B) Sequence alignment of the HMG-box domain regions in orthologs of PDD1 from different fungi of the Basidiomycota phylum. A. bisporus, Agaricus bisporus var. bisporus H97; A. subglabra, Auricularia subglabra TFB-10046 SS5; C. cinerea, Coprinopsis cinerea okayama7#130; C. neoformans, Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans JEC21; F. velutipes, Flammulina velutipes L11; G. sinense, Ganoderma sinense ZZ0214-1; L. bicolor, Laccaria bicolor S238N-H82; L. edodes, Lentinus edodes; P. ostreatus, Pleurotus ostreatus PC15; S. crispa, Sparassis crispa; S. commune, Schizophyllum commune H4-8; U. maydis, Ustilago maydis 521.

Homologs of PDD1 are widely present in Basidiomycota, including industrial mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus, A. bisporus, L. edodes, Auricularia subglabra, and Sparassis crispa), wild mushrooms (Ganoderma sinense and Laccaria bicolor), the model basidiomycete species (C. cinerea and S. commune), the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans, and the plant fungal pathogen Ustilago maydis. The conserved regions are located in the HMG-box domain (Fig. 2B).

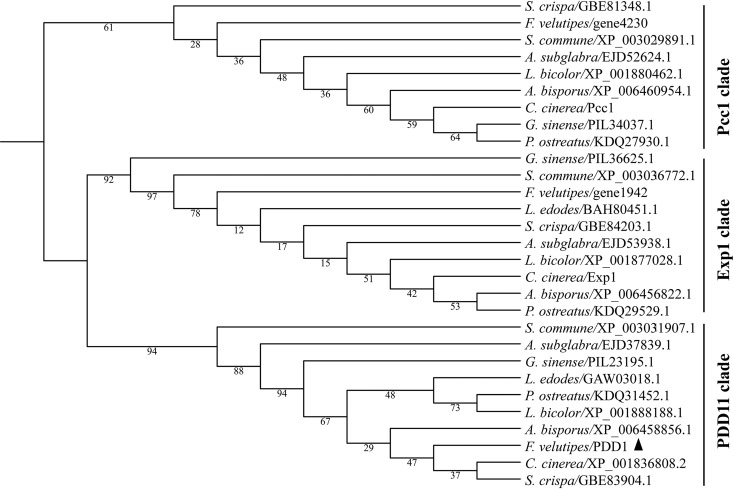

A phylogenetic analysis was conducted with the HMG-box motif sequences of all HMG-box motif-containing proteins (a total of 204 proteins) in 10 fungal species, including 6 industrial mushrooms (F. velutipes, P. ostreatus, A. bisporus, L. edodes, A. subglabra, and S. crispa), 2 wild mushrooms (G. sinense and L. bicolor), and 2 model mushrooms (C. cinerea and S. commune), representing 10 different families of Agaricomycetes. The maximum-likelihood tree showed that all of the HMG-box proteins were clearly separated into different clades (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). All analyzed fungal species had HMG-box proteins in the clade where PDD1 was located, but none of them were previously reported. Among the HMG-box proteins in Agaricomycetes, only C. cinerea Exp1 and Pcc1 were reported previously to be involved in basidioma development (28–30). However, Exp1, Pcc1, and PDD1 were separated into three different clades.

To show in simple terms the phylogenetic relationships among Exp1, Pcc1, and PDD1, a smaller phylogenetic tree containing only 29 proteins, including Exp1, Pcc1, and PDD1 and closely related homologs, was generated (Fig. 3). The maximum-likelihood tree showed that Exp1, Pcc1, and PDD1 were clearly separated into three different clades. To easily distinguish them, we named three clades: the Exp1 clade, Pcc1 clade, and PDD1 clade. In F. velutipes, Exp1 and Pcc1 have their own orthologs encoded by gene 1942 and gene 4230, respectively. This analysis indicates that PDD1 is a novel HMG-box protein and that its orthologs widely exist in the species of Agaricomycetes.

FIG 3.

Phylogenic analysis of HMG-box-containing proteins in fungi of the Agaricomycetes class. The HMG-box motif sequences of HMG-box-containing proteins were extracted with CDD (32) and aligned with ClustalX1.83 (61). The maximum-likelihood tree was then constructed with model LG+G4 using IQ-TREE (62). Numbers next to the branches indicate bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates. A. bisporus, Agaricus bisporus var. bisporus H97; A. subglabra, Auricularia subglabra TFB-10046 SS5; C. cinerea, Coprinopsis cinerea okayama7#130; F. velutipes, Flammulina velutipes L11; G. sinense, Ganoderma sinense ZZ0214-1; L. bicolor, Laccaria bicolor S238N-H82; L. edodes, Lentinus edodes; P. ostreatus, Pleurotus ostreatus PC15; S. crispa, Sparassis crispa; S. commune, Schizophyllum commune H4-8. The solid triangle indicates F. velutipes PDD1 protein.

As reported previously, HMG-box proteins are subdivided into the SOX-TCF_HMG-box, MATA_HMG-box, and HMGB-UBF_HMG-box superfamilies (31). HMG-box proteins in the PDD1 clade and Pcc1 clade belong to the MATA_HMG-box superfamily whereas proteins in the Exp1 clade belong to the HMGB-UBF_HMG-box superfamily based on the results of analysis performed with CDD (32).

Generation of mutants for pdd1 overexpression and knockdown.

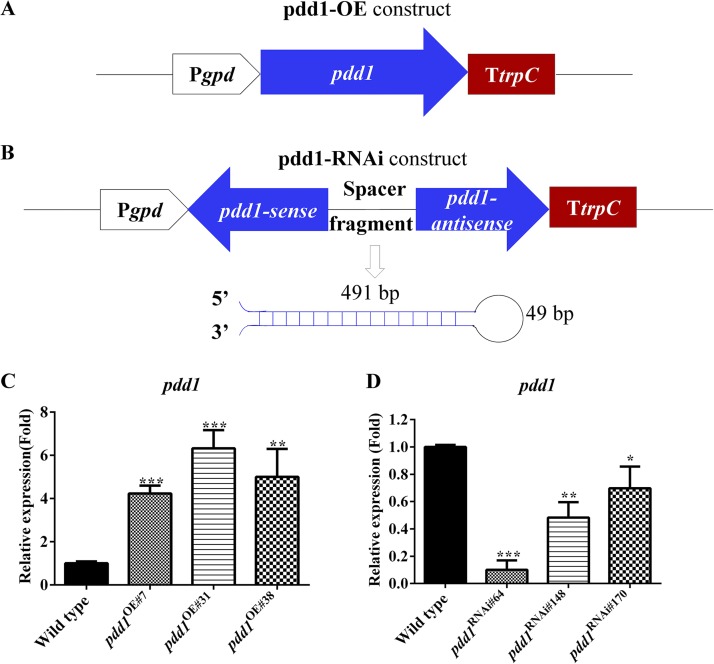

To reveal the function of pdd1 in F. velutipes, pdd1 overexpression vector pdd1-OE and pdd1 knockdown vector pdd1-RNAi (pdd1-RNA interference) were constructed (Fig. 4). Binary vector pBHg-BCA1, the promoter of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase with the first exon and intron (Pgpd) (33) and the terminator of trpC (TtrpC) (34, 35) were used to construct pdd1-OE and pdd1-RNAi. The pdd1 overexpression vector was completed by introducing a copy of pdd1 flanked by Pgpd and TtrpC (Fig. 4A). The pdd1 RNAi vector was constructed to produce a hairpin RNA to induce the degradation of target mRNA (36). It contains two 491-bp complementary regions separated by a 49-bp spacer fragment (the intron adjacent to the second exon of pdd1). The fragment starting at nucleotide 683 and extending to nucleotide 1173 in the second exon of pdd1 was used as the sense sequence (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Construction of mutants for pdd1 overexpression and knockdown. (A and B) Schematic representations of pdd1 overexpression and knockdown constructs. The promoter of gpd and terminator of trpC used in the construction are shown with a white empty arrow and a red rectangle, respectively. The blue arrows represent the opening reading frame of pdd1 (A) and the sense and antisense sequence of the second exon of pdd1 (B). In the RNAi construction, the complemented sense and antisense sequence can form a hairpin. The loop of the hairpin is shown as a black line. (C and D) Transcript levels of pdd1 in the wild-type strain (C and D), pdd1 overexpression strains (C), and pdd1 knockdown strains (D). RNA was extracted from the mycelia cultured on cellophane-covered CYM agar at 25°C for 7 days. Transcript levels of pdd1 were measured by qPCR. The expression of pdd1 was normalized to the transcript level of the β-actin gene and calculated relative to the transcript level in the wild type according to the 2−ΔΔCT method. Results shown are means of three biological replicates. Standard deviations are indicated with error bars. The significant levels were calculated by t test and are marked as follows: *, 0.01 < P < 0.05; **, 0.001 < P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001. Ppdd1OE#7 = 0.0001, n = 3; Ppdd1OE#31 = 0.0004, n = 3; Ppdd1OE#38 = 0.0059, n = 3; Ppdd1RNAi#64 = 0.00002, n = 3; Ppdd1RNAi#148 = 0.0014, n = 3; Ppdd1RNAi#170 = 0.0297, n = 3.

The vectors were introduced into a dikaryotic wild-type (WT) strain of F. velutipes. Three pdd1 overexpression mutants, pdd1OE#7, pdd1OE#31, and pdd1OE#38, were obtained, and their pdd1 transcript levels were found to have increased by 4-fold, 6-fold, and 5-fold, respectively, compared to the wild type (Ppdd1OE#7 = 0.0001, n = 3; Ppdd1OE#31 = 0.0004, n = 3; Ppdd1OE#38 = 0.0059, n = 3) (Fig. 4C). Three pdd1 knockdown mutants, pdd1RNAi#64, pdd1RNAi#148, and pdd1RNAi#170, were obtained in which pdd1 transcript levels were decreased by 89.9%, 51.8%, and 30.2%, respectively, compared to the wild type (Ppdd1RNAi#64 = 0.00002, n = 3; Ppdd1RNAi#148 = 0.0014, n = 3; Ppdd1RNAi#170 = 0.0297, n = 3) (Fig. 4D). The six strains mentioned above were used in the study described here.

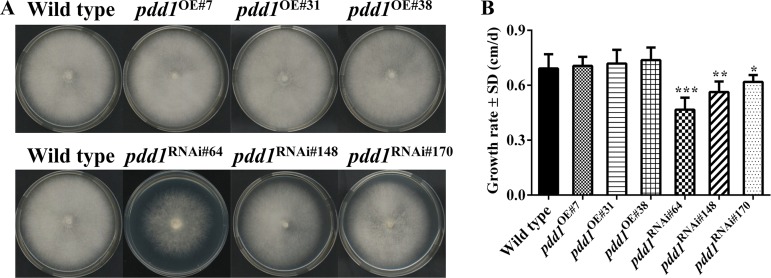

PDD1 positively regulates vegetative growth.

When grown on CYM medium (0.2% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 0.2% [wt/vol] tryptone, 1% [wt/vol] maltose, and 2% [wt/vol] glucose), none of the three pdd1 overexpression strains displayed significant differences from the wild-type strain in colony growth, mycelial density, or colony color (Fig. 5A). However, the mycelia in the colonies of pdd1 knockdown strains were sparser than those in the colonies of the wild-type colonies. The colony growth rates of knockdown strains were significantly lower than those of the wild-type strain (Fig. 5B). The growth rates of pdd1 knockdown strains were reduced by 30.9% ± 6.5%, 18.3% ± 5.8%, and 10.4% ± 3.7% in pdd1RNAi#64, pdd1RNAi#148, and pdd1RNAi#170, respectively, relative to the wild type (Ppdd1RNAi#64 = 0.00003, n = 6; Ppdd1RNAi#148 = 0.0016, n = 6; Ppdd1RNAi#170 = 0.0233, n = 6). The effects of pdd1 knockdown on colony growth were correlated with the expression level of pdd1.

FIG 5.

Effects of pdd1 overexpression and knockdown on mycelial growth on agar plates. (A) Mycelial plugs (diameter [d] = 5 mm) of the wild-type (F19) strain, pdd1 overexpression strains, and pdd1 knockdown strains were inoculated onto the center of CYM plates and cultured at 25°C for 7 days. The colony of each plate was then documented by photography. (B) Growth rates of the wild-type strain and pdd1 overexpression and knockdown mutants. The colony edge was marked every 24 h, and the growth rates of the wild-type strain, pdd1 overexpression strains, and pdd1 knockdown strains were calculated. Values shown are means of results from three biological replicates. Standard deviations (SD) are indicated with error bars. The significant levels were calculated by t test and are marked as follows: *, 0.01 < P < 0.05; **, 0.001 < P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001. Ppdd1OE#7 = 0.7792, n = 6; Ppdd1OE#31 = 0.5783, n = 6; Ppdd1OE#38 = 0.2911, n = 6; Ppdd1RNAi#64 = 0.00003, n = 6; Ppdd1RNAi#148 = 0.0016, n = 6; Ppdd1RNAi#170 = 0.0233, n = 6.

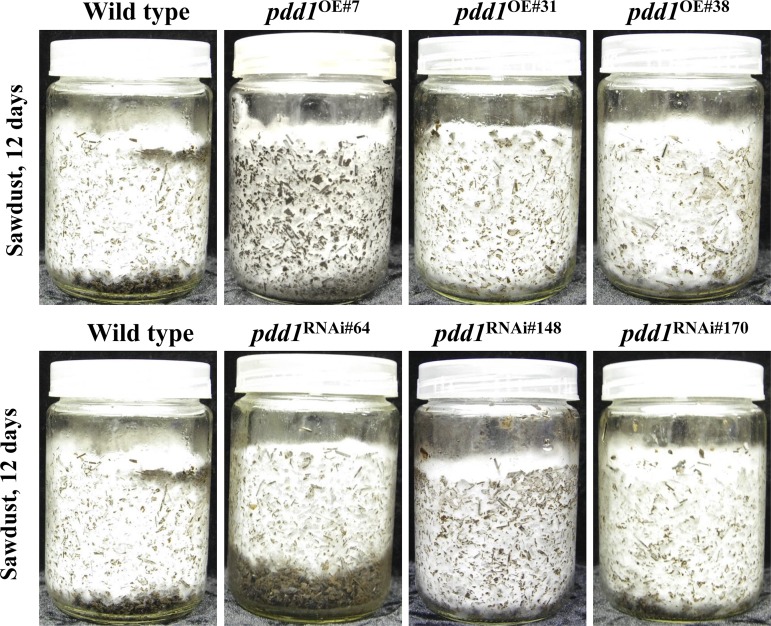

The effects of pdd1 overexpression or knockdown on the vegetative growth of different strains were also analyzed under a condition mimicking that used for F. velutipes industrial production. All strains were inoculated on the surface of the composted sawdust substrate (SM) contained in the culture vessels. Strains were grown at 25°C, and mycelia grew toward the bottom of the vessels. After 12 days, when the mycelia of the wild type occupied 90% of the sawdust substrate, the mycelia of the pdd1 overexpression strains had already reached the bottom of the vessels, completely occupying the substrate (Fig. 6). However, the mycelia of pdd1RNAi#64 occupied only two-thirds of the sawdust substrate. The mycelia of pdd1RNAi#64 took 7 days longer to cover the entire sawdust substrate than the mycelia of the wild type (Fig. 6). The results described above together indicate that PDD1 positively regulates hyphal growth of F. velutipes.

FIG 6.

Effects of pdd1 overexpression and knockdown on mycelial growth in composted sawdust substrate. Strains were inoculated into the culture vessels, each containing 150 ± 5 g composted sawdust substrate. Images of each strain were captured after 12 days of growth at 25°C. Strains included the wild type, pdd1 overexpression strains (pdd1OE#7, pdd1OE#31, and pdd1OE#38), and pdd1 knockdown strains (pdd1RNAi#64, pdd1RNAi#148, and pdd1RNAi#170).

PDD1 positively regulates basidioma development.

Basidioma development was observed in the composted sawdust substrate. After 21 days of culture, the mycelial mats on the medium surface were scraped off to stimulate basidioma development. The primordia in the wild type appeared after 6 days of stimulation (on day 27 after inoculation). Primordia appeared 1 day earlier in the pdd1 overexpression strains than in the wild type, and more primordia were formed with the pdd1 overexpression strains than with the wild type. The optimal time for basidioma harvest in the wild type was day 41, while the pdd1 overexpression strains took only 37 days to reach the same stage (Fig. 7). On day 41, basidiomata of the pdd1 overexpression strains were already aged and their stipes had turned brown, which did not appear at the early stage of basidioma development and which dramatically affects the commercial value. Thus, overexpression of pdd1 could shorten the cultivation time by 9.8% (4 days).

FIG 7.

PDD1 positively regulates basidioma development in F. velutipes. Cultures from half a CYM plate growing each strain were punched into mycelial plugs (diameter [d] = 60 mm). The plugs were inoculated into the culture vessels, each containing 150 ± 5 g composted sawdust substrate. Images of basidioma development were captured on days 27, 37, and 41 after inoculation. Strains included the wild type, pdd1 overexpression strains (pdd1OE#7, pdd1OE#31, and pdd1OE#38), and pdd1 knockdown strains (pdd1RNAi#64, pdd1RNAi#148, and pdd1RNAi#170).

In contrast, the basidioma development in the pdd1 knockdown strains was dramatically impaired. None of them had formed primordia by day 27 after inoculation, the time at which the wild type had formed abundant primordia. On day 41, the pdd1RNAi#148 and pdd1RNAi#170 strains were seen to have produced only a few basidiomata, and they were much smaller size than those produced by the wild type. The pdd1RNAi#64 strain, which had the lowest level of pdd1 expression, had not formed any primordia even after 41 days of cultivation (Fig. 7).

The same experiment was independently repeated three times with six bottles used for each strain each time, and the results were consistent (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). These results together indicate that PDD1 positively regulates basidioma development.

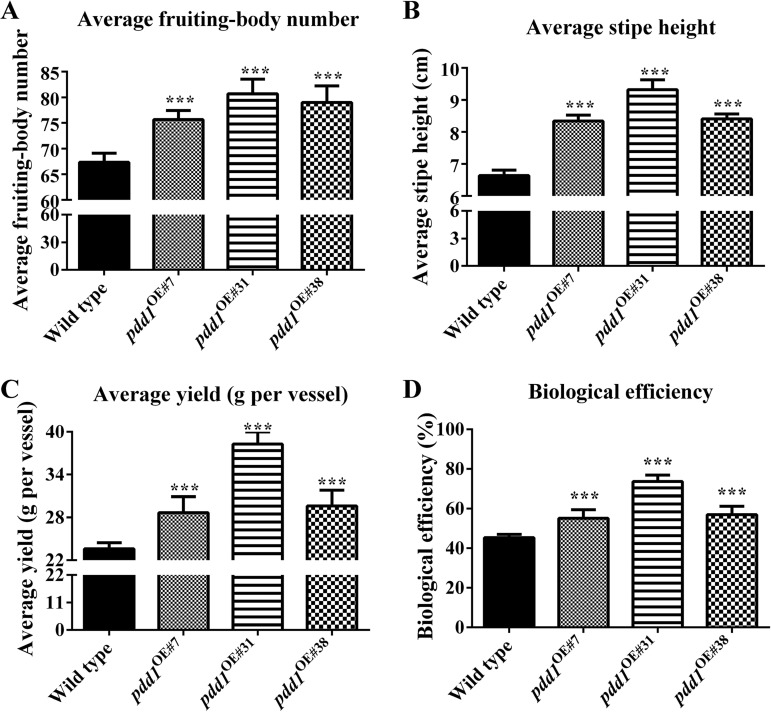

Overexpression of pdd1 increases yield.

Basidiomata were harvested from the bottles of all the strains at the time that had been found to be optimal for the wild-type strain (at day 41). As shown in Fig. 8A, all three pdd1 overexpression strains produced significantly more basidiomata than the wild type. For the first experiment, the average number of basidiomata in the wild type was 67 per vessel, while the average basidioma numbers in the pdd1OE#7, pdd1OE#31, and pdd1OE#38 strains were 75, 80, and 79 per vessel, respectively.

FIG 8.

Effects of pdd1 overexpression on mushroom yield. Basidiomata were harvested on day 41 after inoculation. To mimic the industrial production of F. velutipes, the basidiomata which grew out of the vessel were harvested and analyzed. (A) Average number of basidiomata. (B) Average stipe height. (C) Average yield. (D) Biological efficiency. Results shown are means of six biological replicates. Standard deviations are indicated with error bars. The significant levels were calculated by t test and marked as follows: *, 0.01 < P < 0.05; **, 0.001 < P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001. In average numbers of basidiomata, Ppdd1OE#7 = 9.0587E−06, n = 6; Ppdd1OE#31 = 2.09715E−06, n = 6; Ppdd1OE#38 = 1.48962E−05, n = 6. In average stipe height of basidiomata, Ppdd1OE#7 = 1.31567E−08, n = 6; Ppdd1OE#31 = 4.16545E−09, n = 6; Ppdd1OE#38 = 3.61873E−09, n = 6. In average yield and biological efficiency, Ppdd1OE#7 = 0.000432355, n = 6; Ppdd1OE#31 = 4.10493E−09, n = 6; and Ppdd1OE#38 = 9.34623E−05, n = 6.

The stipe heights of the pdd1 overexpression strains (pdd1OE#7, pdd1OE#31, and pdd1OE#38) were also significantly increased compared to those of the wild type. For the first experiment, the average height of basidiomata in the wild type was 6.64 ± 0.16 cm, while the average heights of basidiomata in the pdd1OE#7, pdd1OE#31, and pdd1OE#38 strains were 8.34 ± 0.19 cm, 9.32 ± 0.31 cm, and 8.41 ± 0.16 cm, respectively (Fig. 8B).

Consequently, the yield and biological efficiency (BE) were significantly increased in these pdd1 overexpression strains relative to the wild type (Fig. 8C and D). As shown in Fig. 8C, the average yields of the wild-type, pdd1OE#7, pdd1OE#31, and pdd1OE#38 were 23.58 ± 0.87 g, 28.66 ± 2.25 g, 38.28 ± 1.72 g, and 29.62 ± 2.19 g, respectively. The highest yield appeared in the stain with the highest level of pdd1 expression, i.e., the pdd1OE#31 strain, in which the yield of basidiomata had increased by 62.31% relative to the wild type, with the highest biological efficiency of 73.61% ± 3.30%.

The yield and biological efficiency increases in pdd1 overexpression strains were consistently seen in three independently repeated experiments (Table S2), among which the yield was increased at least by 33% in the pdd1OE#31 strain.

PDD1 acts as a transcriptional regulator.

In order to understand the regulatory role of PDD1, transcriptomic profiles of the wild type and the pdd1RNAi#64 strain (the pdd1 knockdown strain with the lowest level of pdd1 expression) were comparatively analyzed by RNA-seq. The mycelia were harvested from composted sawdust substrate on day 26, 1 day before primordium formation in the wild-type strain. The genes which were upregulated by more than 2-fold or downregulated by 50% in response to the pdd1 knockdown were defined as differentially regulated genes corresponding to the pdd1 knockdown. Based on these criteria, 331 genes were downregulated and 463 genes were upregulated by the pdd1 knockdown (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). Among the 794 differentially expressed genes, most were annotated as “hypothetical proteins” and their functions had not been previously investigated. However, some differentially expressed genes were associated with basidioma development based on previous reports (37–39). These genes can be divided into three groups: jacalin-related lectin-encoding genes, putative pheromone receptor-encoding genes, and genes encoding FVFD16 and FVFD16 homologs.

PDD1 positively regulates three jacalin-related lectin genes.

The level of expression of jacalin-related lectin-encoding gene Fv-JRL1 was reduced in response to the pdd1 knockdown. According to the results of a previous study (39), Fv-JRL1 positively regulates basidioma development; its transcriptional level was dramatically increased in the primordial stage relative to its expression in the vegetative mycelia, and Fv-JRL1 knockdown severely impaired basidioma development. We found that two genes, gene 10415 and gene 10856, encoding Fv-JRL1 homologs, were also downregulated in the pdd1 knockdown (Data Set S1). Further qPCR analysis using the gene encoding β-actin as the reference gene was conducted to analyze their transcripts in mycelia after the induction of basidioma development. The results showed that the transcriptional levels of Fv-JRL1, gene 10415, and gene 10856 were significantly reduced in the pdd1 knockdown strain compared to the wild type (Fig. 9A). The same RNA samples were analyzed by qPCR using a second reference gene, gpd (encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), and the results were similar (Fig. S2).

FIG 9.

Transcriptional responses of basidioma development-related genes to pdd1 knockdown. Transcript levels of genes encoding (A) jacalin-related lectin (Fv-JRL1, gene 10415, and gene 10856), (B) putative pheromone regulators (FvSTE3.1, FvSTE3.5, FvSTE3.s3, FvSTE3.s4, FvSTE3.s5, and FvSTE3.s6), and (C) FVFD16 and its homologs (FVFD16, gene 2632, and gene 543) were determined in the wild type (F19) and pdd1 knockdown strain pdd1RNAi#64 by qPCR. The expression of indicated genes was normalized to the transcript level of the β-actin gene and calculated relative to the transcript level of the wild type according to the 2−ΔΔCT method. Results shown represent means of results from three biological replicates. Standard deviations are indicated with error bars. The significant levels were calculated by t test and marked as follows: *, 0.01 < P < 0.05; **, 0.001 < P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001. PFv-JRL1 = 0.00383817, n = 3; Pgene 10415 = 8.18691E−05, n = 3; Pgene 10856 = 0.002016353, n = 3; PFvSTE3.1 = 0.002060162, n = 3; PFvSTE3.5 = 0.007959895, n = 3; PFvSTE3.s3 = 0.002370431, n = 3; PFvSTE3.s4 = 0.001617543, n = 3; PFvSTE3.s5 = 0.002459571, n = 3; PFvSTE3.s6 = 0.000248924, n = 3; PFVFD16 = 0.000222852, n = 3; Pgene 2632 = 0.00031644, n = 3; Pgene 543 = 0.000794393.

PDD1 positively regulates six genes encoding pheromone receptors or pheromone-receptor-like proteins.

Pheromone receptors are important regulators of sexual development in fungi. The putative pheromone regulators belong to the STE superfamily of PR (pheromone receptors) encoded by the MAT-B locus, which, together with the MAT-A locus, forms mating-type loci in basidiomycetes (40, 41). Mating type loci regulate the formation of dikaryons and also determine basidioma initiation (42).

Six genes, encoding putative pheromone receptors, were downregulated in the pdd1 knockdown strain based on the RNA-seq analysis. FvSTE3.1 and FvSTE3.2 were pheromone receptors; the others (FvSTE3.s3, FvSTE3.s4, FvSTE3.s5, and FvSTE3.s6) were pheromone-receptor-like proteins (38). Further qPCR analysis performed using β-actin and gpd as the reference genes also showed that the transcriptional levels of six genes were reduced in the pdd1 knockdown strain compared to the wild-type strain in mycelia after the induction of basidioma development (Fig. 9B; see also Fig. S2), indicating that these putative pheromone-receptor-encoding genes are regulated by PDD1.

PDD1 positively regulates FVFD16 and its two homologs.

FVFD16 was reported to be related to differentiation of basidioma and was named “F. velutipes fruiting body differentiation” (37). FVFD16 and two FVFD16 homolog-encoding genes (gene 2632 and gene 543) were downregulated in response to pdd1 silencing, based on the RNA-seq data (Data Set S1) and on further confirmation by qPCR, using β-actin and gpd as the reference genes, respectively (Fig. 9C; see also Fig. S2).

DISCUSSION

The PDD1 gene could be an important reference gene for mushroom breeding.

Although some transcription factors with regulatory function in basidioma development have been found in studies of the two model species S. commune and C. cinerea, some of their orthologs in industrially cultivated mushrooms did not display expression patterns correlating with basidioma development, suggesting that fungi in the phylum Basidiomycota have diverse regulatory mechanisms in basidioma development. Here, from one of the most widely cultivated basidiomycete fungi, F. velutipes (9), we identified the HMG-box-containing transcription factor PDD1 as a novel regulator of basidioma development on the basis of the following lines of evidence: (i) transcription of pdd1 was highly induced during the development of basidiomata; (ii) pdd1 overexpression promoted the development of basidiomata and shortened the cultivation time, while the basidioma development was dramatically impaired by pdd1 knockdown; and (iii) some genes, related to basidioma development, were positively regulated by PDD1. When the transcription level of pdd1 was increased 5-fold by gene overexpression, the cultivation time was able to be shortened by 4 days (9.8%) and the yield could be increased by at least 33%. The yield increase should be mainly attributable to the increases in the number and the height of basidiomata. Commercial cultivation of F. velutipes requires maintaining a lower temperature during basidioma development, and the cost for cooling the growth chambers is very high. The shorter cultivation time will reduce the production cost. As the pdd1 overexpression strain develops faster than the wild type and its harvesting time in this study was later than its optimal time, the increase in yield should not be as high as the level in the data from our experiment under the real commercial production conditions. Nevertheless, increases in the number and height of basidiomata should definitely increase yield and PDD1 could be an important reference gene for mushroom breeding.

PDD1 is a novel transcription factor in mushrooms.

PDD1 is a transcription factor with a HMG-box domain. HMG-box-domain-containing proteins are abundant in eukaryotes (43). The members of this group of proteins are involved in diverse biological processes, such as sex determination (44, 45), cell differentiation (46, 47), and stress responses (48, 49). Two HMG-box-containing proteins involved in mushroom basidioma development, Pcc1 and Exp1, have been found in C. cinerea (28–30). Our phylogenetic analysis performed with amino acid sequences in the HMG-box motif demonstrated that PDD1 is not an ortholog of either Pcc1 or Exp1. Although both Pcc1 and PDD1 are members of the family of MATA_HMG-box proteins, they are distributed into two different clades. Thus, the orthologs of PDD1, Pcc1, and Exp1 cluster in three different clades. Both Pcc1 and Exp1 have their own orthologs in F. velutipes, and the PDD1 ortholog is also present in C. cinerea (Fig. 3). In addition, Pcc1 and Exp1 differ from PDD1 in their expression patterns and in their regulated developmental stages during basidioma development (15, 16, 28, 30). Thus, they should play different roles in basidioma development.

To date, only three PDD1 homologs have been previously reported in fungi of the Basidiomycota phylum, including Prf1 in U. maydis and Hgr1 and Hgr2 in C. neoformans (50, 51). PDD1 displays 30% amino acid identity with the first homolog, Prf1 (38% coverage), and they share 34.78% identity in their HMG-box domain regions (93% coverage) by protein BLAST (52). The other two homologs are Hgr1 and Hgr2 in C. neoformans (50). PDD1 displays 30.66% amino acid identity with the entire sequence of Hgr1 (58% coverage), and they share 37.5% identity in their HMG-box domain regions (100% coverage). PDD1 displays 30.92% amino acid identity with the entire sequence of Hgr2 (55% coverage), and they share 34.72% identity in their HMG-box domain regions (100% coverage). Interestingly, these PDD1 homologs are all involved in sexual development. Prf1 is required for basal transcriptional responses to pheromones in U. maydis (53). Hgr1 and Hgr2 are required in filamentation and spore production in the sexual development of C. neoformans, respectively (50). Thus, although the level of identity between PDD1 and each of these known proteins is low, there might be some functional similarity.

Nevertheless, the roles of PDD1 homologs in basidioma development were not previously reported. Thus, PDD1 is a novel regulator in basidioma development in the phylum Basidiomycota.

PDD1 might play a more important role in basidioma development than other HMG-box-containing proteins.

In F. velutipes, there are 26 genes encoding HMG-box-containing proteins (see Data Set S2 in the supplemental material). Among these predicted HMG-box-containing proteins, only 8 have nuclear localization signals. Based on our RNA-seq analysis, only four of them showed a dramatic transcriptional response to the treatment inducing basidioma development, and pdd1 is the most highly upregulated gene (15, 16). Therefore, PDD1 might be important for basidioma development in F. velutipes.

The regulatory mechanisms of PDD1 in basidioma development.

This study revealed the mechanisms by which PDD1 regulates basidioma development. First, PDD1 likely controls basidioma development through regulating the expression of genes encoding jacalin-related lectins. In Sclerotium rolfsii, the interaction of lectin with the cell wall-associated putative endogenous receptor promotes the aggregation of mycelia to form sclerotial bodies (54). In F. velutipes, jacalin-related lectin-encoding gene Fv-JRL1 and the two corresponding homolog-encoding genes were upregulated dramatically at the primordium formation stage. Fv-JRL1 promotes hyphal growth and basidioma development (39). Lectin-encoding genes have also been previously shown to be associated with basidioma development in several other fungi (55). Production of lectins might help the aggregation of mycelia for basidioma formation. The failure in primordium formation in the pdd1 knockdown mutant pdd1RNAi#64 might have been due to a reduction in lectin production. Second, PDD1 might exert its influence on basidioma development through regulating a pheromone pathway. The response by specific pheromone receptors to pheromone triggers the formation of dikaryons (56) and initiates the formation of basidiomata in fungi of the Basidiomycota phylum (57). Regulation of these genes suggests a role for PDD1 in the mating process. The PDD1 homolog Prf1 in U. maydis regulates mating by activating the expression of pheromone-inducible genes (51, 53, 58). Thus, PDD1 might play a role similar to that played by Prf1 in the mating system through regulating the pheromone response. During basidioma development, their transcript levels were increased (15, 16), suggesting their involvement in basidioma formation, and PDD1 might control the basidioma development by regulating the expression of these genes. In addition, PDD1 might promote basidioma development by activating the expression of FVFD16 and its homologs. FVFD16 has a transcriptional profile correlating with basidioma differentiation (37). The downregulated expression of FVFD16 and its homologs in response to pdd1 knockdown suggests their involvement in PDD1-regulated mechanisms. In addition to the genes described above, PDD1 also regulates many other genes with unknown function, which might also influence basidioma development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

Dikaryotic strain F19 and monokaryotic strain L11 of F. velutipes and binary vector pBHg-BCA1 were provided by Fujian Edible Fungi Germplasm Resource Collection Center of China (15, 16). F. velutipes strains were routinely maintained on CYM medium (0.2% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 0.2% [wt/vol] tryptone, 1% [wt/vol] maltose, and 2% [wt/vol] glucose) at 25°C (59). The composted sawdust substrate, which contained 52.5% cottonseed hulls, 25% wheat bran, 15% sawdust, 5% corn flour, 2% gypsum, and 0.5% ground limestone, was adjusted to a total moisture content of 61% and used to produce basidiomata (16). Escherichia coli DH5α was used for propagation of plasmids, and Agrobacterium tumefaciens AGL-1 was used for transferring the plasmids into F. velutipes.

Identification of pdd1 in F. velutipes.

The sequence of the pdd1 gene was obtained from the genome of F. velutipes monokaryotic strain L11 (GenBank accession no. MG264427; BioProject 191865).

Sequence alignments and phylogenetic analyses.

The amino acid sequences of the HMG-box contained in F. velutipes were predicted from the genome of monokaryotic strain L11 (data not shown), and the other protein sequences were obtained from the NCBI database (60). The HMG-box motif sequences of HMG-box-containing proteins were extracted using CDD (32) and aligned using Clustal X 1.83 (61). The maximum-likelihood tree was then constructed using IQ-TREE (62).

Plasmid construction and fungal transformation.

Binary vector pBHg-BCA1 was used to construct the pdd1 overexpression plasmid and the RNAi plasmid. Schematic representations of pdd1 overexpression and RNAi constructs are shown in Fig. 4A and B, respectively. In both plasmids, the promoter of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-encoding gene gpd (Pgpd) and the terminator of indole-3-glycerol phosphate synthase-encoding gene trpC (TtrpC) were used to control expression of pdd1 or the sense and antisense sequences of pdd1 (33–35).

For constructing the overexpression plasmid, Pgpd and TtrpC were first amplified by PCR with primer pairs Pgpd-F/R and TtrpC-F/R from the genomic DNA of strain L11 and plasmid pCSN44 (Fungal Genetics Stock Center, www.fgsc.net/; University of Kansas Medical Center), respectively. The open reading frame of pdd1 (1,204 bp) was then amplified by PCR with primers pdd1-F and pdd1-R from the genomic DNA of strain L11. These three fragments were inserted into pBHg-BCA1 by homologous recombination (ClonExpress MultiS one-step cloning kit; Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The obtained overexpression plasmid was designated pdd1-OE.

To construct the pdd1 RNAi plasmid, Pgpd and TtrpC were first obtained as described above. Then a 491-bp antisense sequence of pdd1 was amplified from F. velutipes L11 by PCR with primers pdd1-antisense-F and pdd1-antisense-R. The three fragments described above were inserted into pBHg-BCA1 to form vector pre-pdd1-RNAi. After that, the sense sequence linked with the spacer (540 bp) was amplified from F. velutipes L11 by PCR with primers pdd1-sense-F and pdd1-sense-R, digested using BamHI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA), and ligated into pre-pdd1-RNAi to form the final pdd1-RNAi vector. This construct was used to generate a double-stranded RNA (hairpin), which was comprised of two 491-bp complementary regions (sense sequence and antisense sequence) separated by a 49-bp spacer fragment (the intron adjacent to the second exon of pdd1) to induce the degradation of target mRNA (36). The primers used in vector construction are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers for plasmid construction

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Pgpd-F | CAGATCCCCCGAATTATTCGAGCTCGGTACAGTCGTG | Amplification of Pgpd fragment used in pdd1 overexpression and RNAi plasmids |

| Pgpd-R | AGAAAGAGTGGACCTGTAAAATGGTGAGCAAGAC | |

| pdd1-F | TTTACAGGTCCACTCTTTCTCAGCCTACTACGACCA | Amplification of pdd1 fragment used in pdd1 overexpression plasmids |

| pdd1-R | AAGTGGATCCTCAAAATGCAAGGCCACTACCT | |

| TtrpC-F | TGCATTTTGAGGATCCACTTAACGTTACTGAAATCA | Amplification of TtrpC fragment used in pdd1 overexpression and RNAi plasmids |

| TtrpC-R | AATTAACGCCGAATTCATGCCTGCAGGTCGAGAAAG | |

| pdd1-antisense-F | CATTTTACAGGTCATGGGCCCATGTTCCAAGTCGGGTTTAAAGGC | Amplification of pdd1 antisense fragment for the construction of pre-pdd1-RNAi |

| pdd1-antisense-R | GAGGACTTACCGTCAAGAAAGAACCCACCGTTG | |

| pdd1-sense-F | TTTCTTGACGGTAAGTCCTCACTTCATCGTCTCGATG | Amplification of pdd1 sense fragment linked with the spacer for the construction of pdd1-RNAi |

| pdd1-sense-R | CAGTAACGTTAAGTGGATCCATGTTCCAAGTCGGGTTTAAAGGC | |

| Pgpd-detect-F | AACCGCCATCTTCCACACTT | Verification of the two entire constructions Pgpd-pdd1OE-TtrpC and Pgpd-pdd1RNAi-TtrpC |

| TtrpC-detect-F | AACACCATTTGTCTCAACTCCG | |

The two plasmids pdd1-OE and pdd1-RNAi were transformed into F. velutipes dikaryotic strain F19 via A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation according to the previously reported protocol (59, 63), with minor modification. First, the A. tumefaciens strains containing pdd1-OE or pdd1-RNAi were coincubated with a F. velutipes mycelial pellet (FMP) in the inducing medium (59, 63) for 6 h at 25°C. The FMPs were obtained by cutting the mycelia grown on CYM media into small plugs with a hole punch (diameter = 5 mm). Second, after cocultivation, the treated FMPs were washed with the inducing medium three times to remove A. tumefaciens and then transferred onto CYM selection medium containing 12.5 μg ml−1 hygromycin B and 300 mM cefotaxime. The plates were incubated at 25°C for 2 to 3 weeks until colonies of transformants formed. The transformants were then transferred onto CYM medium containing 25 μg ml−1 hygromycin B eight times. The transformants were verified by PCR with primers Pgpd-detect-F and TtrpC-detect-R. The primers used for transformant verification are shown in Table 1.

Total DNA extraction.

DNA was extracted from F. velutipes mycelia, which were cultured on cellophane-covered CYM agar at 25°C for 7 days, using a modified CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) approach (64).

Measurement of hyphal growth rate.

The mycelia plug (diameter = 5 mm), which was punched from the wild-type strain or the pdd1 mutants, was inoculated onto the center of the CYM plates (diameter = 60 mm) and grown at 25°C. After 3 days of growth, the colony edge was marked as the origin. The colony edge was then marked every 24 h in the following 4 days, and the hyphal growth rate was calculated as the average colony extension per day. This experiment was repeated three times independently.

Basidioma cultivation and phenotypic analysis of mutants.

The basidioma cultivation was performed according to previously reported methods (21, 65) with minor modification. The mycelial plugs (diameter = 5 mm), which were punched from the wild-type strain or the pdd1 mutants, were inoculated on the CYM plates (diameter = 60 mm) and cultured at 25°C for 5 days. After 5 days, a colony from half of a CYM plate was cut into small squares (side length = 5 mm) and inoculated into a culture vessel containing 150 ± 5 g (wet weight) composted sawdust substrate. The vessels were incubated at 25°C and 60% humidity in the dark. After 19 days, when the mycelia of all strains completely occupied the culture vessel, the mycelial mat on the surface of the medium was scraped by the use of a sterilized scalpel. Basidioma development was then induced by shifting the cultivation condition to a lower temperature (15°C), higher humidity (95%), and constant light exposure. This condition was maintained until the basidiomata were harvested.

To mimic the industrial production of F. velutipes, basidiomata with stipes extending from the vessel were harvested and their fresh weight was used to record the yield of each vessel. Biological efficiency (BE) was calculated for each strain using the following formula: percent BE = (weight of fresh basidiomata/weight of dry substrate) × 100 (66, 67). All the results were obtained by measuring basidiomata harvested from six vessels for each strain, and the average values were then calculated. The experiments were independently repeated three times.

RNA extraction.

For RNA extraction from mycelia grown on agar plates, mycelial plugs (diameter = 5 mm) were inoculated on the center of cellophane-covered CYM agar plates and incubated at 25°C for 7 days in the dark. Mycelia were then collected for RNA extraction. Each strain was prepared in three biological replicates. For RNA extraction from mycelia grown in composted sawdust substrate (SM), the mycelia of each strain from 6 vessels were mixed for RNA extraction.

RNA extractions were performed following previously described methods (16). The harvested mycelia were freshly frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground into a fine powder. Total RNA extraction was performed according to the standard TRIzol protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The cDNAs were synthesized from 2 μg total RNA using a cDNA synthesis kit (FastQuant RT kit [with gDNase]; Tiangen, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Gene expression analysis by qPCR.

RNA extracts from three independent replicates were used for qPCR analysis. qPCR was performed on a CFX96 multicolor real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with SYBR green detection (Kapa SYBR FAST qPCR kits; Kapa Biosystems, Boston, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each cDNA sample was analyzed in triplicate, and the average threshold cycle (CT) value was calculated. The expression levels of genes were normalized to the expression level of β-actin or gpd in F. velutipes. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT threshold cycle calculation (68). The significance of the differences between two samples was evaluated by an unpaired two-tailed Student's t test using GraphPad Prism 7.0, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered to represent significance. Gene-specific primers used for qPCR are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers for qPCR

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Target | Size of the target (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q-FvActin-F | CACCATGTTCCCTGGTATTG | β-actin | 106 |

| Q-FvActin-R | CACCAATCCAGACAGAGTATTT | ||

| Q-Fvgpd-F | CACGACAAGTTCGGTATTG | gpd | 142 |

| Q-Fvgpd-R | CAGTCGAGGAAGGAATGA | ||

| Q-pdd1-F | TCAGCAATGCGTCTGACACG | pdd1 | 120 |

| Q-pdd1-R | CGTTCATGTTCCAAGTCGGGT | ||

| Q-Fv-JRL1-F | CTGACAAAGGCAGAGTAAC | Fv-JRL1 | 142 |

| Q-Fv-JRL1-R | CCTTGACGATGGAGATAGA | ||

| Q-gene10415-F | TGTCATCAAAGAGTCGGATA | Gene 10145 | 129 |

| Q-gene10415-R | TTGACGAGGGAGAGAGA | ||

| Q-gene10856-F | AGGGCTGTCATCAAAGAG | Gene 10856 | 129 |

| Q-gene10856-R | GAGAGAGAGAGAGGTGAGA | ||

| Q-FVFD16-F | AGGTTGCTGCTGTTAGT | FVFD16 | 103 |

| Q-FVFD16-R | AACAGGAGGAGTGTGATG | ||

| Q-gene543-F | GACATCGTCAAGAACATCAA | Gene 543 | 122 |

| Q-gene543-R | AATCCCGGAACCAAGAA | ||

| Q-gene2632-F | CCTCCTGTTCAACCTGAT | Gene 2632 | 104 |

| Q-gene2632-R | TGACCGTAAGAAGAACCC | ||

| Q-FvSTE3.s4-F | GCTGACATTGCCTTCAC | FvSTE3.s4 | 134 |

| Q-FvSTE3.s4-R | AGGGAAGCGGGAATAAG | ||

| Q-FvSTE3.1-F | CCTTTGCTGCCCATTTAG | FvSTE3.1 | 132 |

| Q-FvSTE3.1-R | CCGATGCTGTGTATGAAAG | ||

| Q-FvSTE3.5-F | AGATCTGGCGTGGTATTT | FvSTE3.5 | 129 |

| Q-FvSTE3.5-R | CCTTCCGGTAATTCTTCTTG | ||

| Q-FvSTE3.s6-F | GCAAAGCCATCTACCAAG | FvSTE3.s6 | 125 |

| Q-FvSTE3.s6-R | GCCTGTGGAGAACTAAGA | ||

| Q-FvSTE3.s5-F | CGTTCTCGTTTGCTGATG | FvSTE3.s5 | 114 |

| Q-FvSTE3.s5-R | TCGGATGAAGATGAGGTATG | ||

| Q-FvSTE3.s3-F | GTCTTCGGTGGTTACAAAG | FvSTE3.s3 | 135 |

| Q-FvSTE3.s3-R | CTCGACACCTGTTTCTTAAC | ||

RNA sequencing.

RNA was extracted on day 26, 1 day before primordium appearance for the wild type, from mixed mycelia from six vessels containing composted sawdust substrate (SM) as the growth medium.

The transcriptomic profiles of the wild-type (WT) strain and the pdd1 knockdown strain (pdd1RNAi#64) were comparatively analyzed by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). The cDNA library was constructed using an RNA Library Prep kit for Illumina (NEB, USA) and was assessed by the use of an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. The two samples (WT_SM and pdd1RNAi_64_SM) were sequenced using the BGIseq-500RS platform (Beijing Genomics Institute, Wuhan, China).

After sequencing, each sample on average generated 24,081,093 clean reads after filtering low-quality ones, and these reads were mapped to the genome of strain L11 (GenBank accession no. APIA00000000; BioProject 191865) using HISAT (69) and Bowtie2 (70) tools. Gene expression levels were estimated by the use of RNA-seq by expectation-maximization (RSEM), and the normalized number of transcript fragments per kilobase per million (FPKM) mapped reads was calculated. The transcript level of a gene was determined by calculating the FPKM, and those with a FPKM value of less than 5 in all samples were regarded as low-expression-level genes and excluded from the study. GO (Gene Ontology; http://www.geneontology.org) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) were used in the gene function annotation.

Genes with log2|fold change| levels of ≥1.0 and FDR (false-discovery-rate) values of <0.001 in comparisons between the wild-type strain and pdd1 knockdown mutant pdd1RNAi#64 were considered to be differentially expressed. For confirming the RNA-seq data, the transcript levels of randomly selected genes in WT_SM and pdd1RNAi_64_SM were verified by qPCR on a CFX96 multicolor real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and a SYBR green detection system (Kapa SYBR Fast qPCR kits; Kapa Biosystems, Boston, MA, USA), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Key Basic Research Program of China (2014CB138302 to S.L.).

We declare that we have no conflicts of interests in relation to the work described.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01735-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wasser SP. 2017. Medicinal mushrooms in human clinical studies. Part I. Anticancer, oncoimmunological, and immunomodulatory activities: a review. Int J Med Mushrooms 19:279–317. doi: 10.1615/IntJMedMushrooms.v19.i4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ren L, Perera C, Hemar Y. 2012. Antitumor activity of mushroom polysaccharides: a review. Food Funct 3:1118–1130. doi: 10.1039/c2fo10279j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boa E. 2004. Wild edible fungi: a global overview of their use and importance to people. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang S-T, Miles PG. 2004. Mushrooms: cultivation, nutritional value, medicinal effect, and environmental impact, 2nd ed CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morin E, Kohler A, Baker AR, Foulongne-Oriol M, Lombard V, Nagy LG, Ohm RA, Patyshakuliyeva A, Brun A, Aerts AL, Bailey AM, Billette C, Coutinho PM, Deakin G, Doddapaneni H, Floudas D, Grimwood J, Hildén K, Kües U, LaButti KM, Lapidus A, Lindquist EA, Lucas SM, Murat C, Riley RW, Salamov AA, Schmutz J, Subramanian V, Wösten HAB, Xu J, Eastwood DC, Foster GD, Sonnenberg ASM, Cullen D, de Vries RP, Lundell T, Hibbett DS, Henrissat B, Burton KS, Kerrigan RW, Challen MP, Grigoriev IV, Martin F. 2013. Genome sequence of the button mushroom Agaricus bisporus reveals mechanisms governing adaptation to a humic-rich ecological niche. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:4146–4148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206847109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang M, Gu B, Huang J, Jiang S, Chen Y, Yin Y, Pan Y, Yu G, Li Y, Wong BHC, Liang Y, Sun H. 2013. Transcriptome and proteome exploration to provide a resource for the study of Agrocybe aegerita. PLoS One 8:e56686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohm RA, de Jong JF, de Bekker C, Wösten HAB, Lugones LG. 2011. Transcription factor genes of Schizophyllum commune involved in regulation of mushroom formation. Mol Microbiol 81:1433–1445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohm RA, de Jong JF, Lugones LG, Aerts A, Kothe E, Stajich JE, de Vries RP, Record E, Levasseur A, Baker SE, Bartholomew KA, Coutinho PM, Erdmann S, Fowler TJ, Gathman AC, Lombard V, Henrissat B, Knabe N, Kües U, Lilly WW, Lindquist E, Lucas S, Magnuson JK, Piumi F, Raudaskoski M, Salamov A, Schmutz J, Schwarze F, vanKuyk PA, Horton JS, Grigoriev IV, Wösten HAB. 2010. Genome sequence of the model mushroom Schizophyllum commune. Nat Biotechnol 28:957–963. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Royse DJ, Baars J, Tan Q. 2017. Edible and medicinal mushrooms: technology and applications. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matheny PB, Curtis JM, Hofstetter V, Aime MC, Moncalvo J-M, Ge Z-W, Yang Z-L, Slot JC, Ammirati JF, Baroni TJ, Bougher NL, Hughes KW, Lodge DJ, Kerrigan RW, Seidl MT, Aanen DK, DeNitis M, Daniele GM, Desjardin DE, Kropp BR, Norvell LL, Parker A, Vellinga EC, Vilgalys R, Hibbett DS. 2006. Major clades of Agaricales: a multilocus phylogenetic overview. Mycologia 98:982–995. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang S-T. 2008. Overview of mushroom cultivation and utilization as functional foods, p 1–33. In Cheung PCK. (ed), Mushrooms as functional foods. Wiley and Sons, Inc, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srivilai P, Loutchanwoot P. 2009. Coprinopsis cinerea as a model fungus to evaluate genes underlying sexual development in basidiomycetes. Pak J Biol Sci 12:821–835. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2009.821.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelkmans JF, Lugones LG, Wösten HAB (ed). 2015. Fruiting body formation in basidiomycetes. Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simchen G. 1966. Fruiting and growth rate among dikaryotic progeny of single wild isolates of Schizophyllum commune. Genetics 53:1151–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu F, Wang W, Chen B-Z, Xie B-G. 2015. Homocitrate synthase expression and lysine content in fruiting body of different developmental stages in Flammulina velutipes. Curr Microbiol 70:821–828. doi: 10.1007/s00284-015-0791-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang W, Liu F, Jiang Y, Wu G, Guo L, Chen R, Chen B, Lu Y, Dai Y, Xie B. 2015. The multigene family of fungal laccases and their expression in the white rot basidiomycete Flammulina velutipes. Gene 563:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Bao L, Liu D, Yang X, Li S, Gao H, Yao X, Wen H, Liu H. 2012. Two new sesquiterpenes and six norsesquiterpenes from the solid culture of the edible mushroom Flammulina velutipes. Tetrahedron 68:3012–3018. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2012.02.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Bao L, Yang X, Li L, Li S, Gao H, Yao X, Wen H, Liu H. 2012. Bioactive sesquiterpenoids from the solid culture of the edible mushroom Flammulina velutipes growing on cooked rice. Food Chem 132:1346–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.11.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Bao L, Yang X, Guo H, Dai H, Gao H, Yao X, Zhang L, Liu H. 2012. New cuparene-type sesquiterpenes from Flammulina velutipes. Helv Chim Acta 95:261–267. doi: 10.1002/hlca.201100289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tao Q, Ma K, Yang Y, Wang K, Chen B, Huang Y, Han J, Bao L, Liu X, Yang Z, Yin W, Liu H. 2016. Bioactive sesquiterpenes from the edible mushroom Flammulina velutipes and their biosynthetic pathway confirmed by genome analysis and chemical evidence. J Org Chem 81:9867–9877. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park Y-J, Baek JH, Lee S, Kim C, Rhee H, Kim H, Seo J-S, Park H-R, Yoon D-E, Nam J-Y, Kim H-I, Kim J-G, Yoon H, Kang H-W, Cho J-Y, Song E-S, Sung G-H, Yoo Y-B, Lee C-S, Lee B-M, Kong W-S. 2014. Whole genome and global gene expression analyses of the model mushroom Flammulina velutipes reveal a high capacity for lignocellulose degradation. PLoS One 9:e93560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto T, Yamada M, Sekiya S, Okuhara T, Taguchi G, Inatomi S, Shimosaka M. 2010. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of the vegetative dikaryotic mycelium of the cultivated mushroom Flammulina velutipes. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 74:2327–2329. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JK, Park YJ, Kong WS, Kang HW. 2010. Highly efficient electroporation-mediated transformation into edible mushroom Flammulina velutipes. Mycobiology 38:331–335. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2010.38.4.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi L, Chen D, Xu C, Ren A, Yu H, Zhao M. 2 May 2017, posting date Highly-efficient liposome-mediated transformation system for the basidiomycetous fungus Flammulina velutipes. J Gen Appl Microbiol doi: 10.2323/jgam.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P. 2015. SMART: recent updates, new developments and status in 2015. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D257–D260. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Letunic I, Bork P. 2018. 20 years of the SMART protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res 46:D493–D496. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kosugi S, Hasebe M, Tomita M, Yanagaw H. 2009. Systematic identification of cell cycle-dependent yeast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins by prediction of composite motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:10171–10176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900604106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murata Y, Fujii M, Zolan ME, Kamada T. 1998. Molecular analysis of pcc1, a gene that leads to A-regulated sexual morphogenesis in Coprinus cinereus. Genetics 149:1753–1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murata Y, Kamada T. 2009. Identification of new mutant alleles of pcc1 in the homobasidiomycete Coprinopsis cinerea. Mycoscience 50:137–139. doi: 10.1007/S10267-008-0454-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muraguchi H, Fujita T, Kishibe Y, Konno K, Ueda N, Nakahori K, Yanagi SO, Kamada T. 2008. The exp1 gene essential for pileus expansion and autolysis of the inky cap mushroom Coprinopsis cinerea (Coprinus cinereus) encodes an HMG protein. Fungal Genet Biol 45:890–896. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soullier S, Jay P, Poulat F, Vanacker J-M, Berta P, Laudet V. 1999. Diversification pattern of the HMG and SOX family members during evolution. J Mol Evol 48:517–527. doi: 10.1007/pl00006495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marchler-Bauer A, Bo Y, Han L, He J, Lanczycki JC, Lu S, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, Lu F, Marchler GH, Song JS, Thanki N, Wang Z, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Zheng C, Geer LY, Bryant SH. 2017. CDD/SPARCLE: functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D200–D203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuo C-Y, Chou S-Y, Huang C-T. 2004. Cloning of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene and use of the gpd promoter for transformation in Flammulina velutipes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 65:593–599. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1635-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sekiya S, Yamada M, Shibata K, Okuhara T, Yoshida M, Inatomi S, Taguchi G, Shimosaka M. 2013. Characterization of a gene coding for a putative adenosine deaminase-related growth factor by RNA interference in the basidiomycete Flammulina velutipes. J Biosci Bioeng 115:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim S, Ha B-S, Ro H-S. 2015. Current technologies and related issues for mushroom transformation. Mycobiology 43:1–8. doi: 10.5941/MYCO.2015.43.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hannon GJ. 2002. RNA interference. Nature 418:244–251. doi: 10.1038/418244a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim D-Y, Azuma T-N. 1999. Cloning of a gene specifically expressed during early stage of fruiting body formation in Flammulina velutipes. Korean J Mycol 27:187–190. http://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/JAKO199903040131785.page. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang W, Lian L, Xu P, Chou T, Mukhtar I, Osakina A, Waqas M, Chen B, Liu X, Liu F, Xie B, van Peer AF. 2016. Advances in understanding mating type gene organization in the mushroom forming fungus Flammulina velutipes. G3 (Bethesda) 6:3635–3645. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.034637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu YP, Chen RL, Long Y, Li X, Jiang YJ, Xie BG. 2016. A jacalin-related lectin regulated the formation of aerial mycelium and fruiting body in Flammulina velutipes. Int J Mol Sci 17:1884–1810. doi: 10.3390/ijms17121884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maia TM, Lopes ST, Almeida J, Rosa LH, Sampaio JP, Gonçalves P, Coelho MA. 2015. Evolution of mating systems in basidiomycetes and the genetic architecture underlying mating-type determination in the yeast Leucosporidium scottii. Genetics 201:75–89. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.177717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kües U. 2015. From two to many: multiple mating types in Basidiomycetes. Fungal Biol Rev 29:126–166. doi: 10.1016/j.fbr.2015.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raudaskoski M, Kothe E. 2010. Basidiomycete mating type genes and pheromone signaling. Eukaryot Cell 9:847–859. doi: 10.1128/EC.00319-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bustin M. 2001. Revised nomenclature from high mobility group (HMG) chromosomal proteins. Trends Biochem Sci 26:152–153. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01777-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang T, Hou C-C, She Z-Y, Yang W-X. 2013. The SOX gene family: function and regulation in testis determination and male fertility maintenance. Mol Biol Rep 40:2187–2194. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bergstrom DE, Young M, Albrecht KH, Eicher EM. 2000. Related function of mouse SOX3, SOX9, and SRY HMG domains assayed by male sex determination. Genesis 28:111–124. doi:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nemeth MJ, Curtis DJ, Kirby MR, Garrett-Beal LJ, Seidel NE, Cline AP, Bodine DM. 2003. Hmgb3: an HMG-box family member expressed in primitive hematopoietic cells that inhibits myeloid and B-cell differentiation. Blood 102:1298–1306. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koopman P. 2010. HMG domain superfamily of DNA-bending proteins: HMG, UBF, TCF, LEF, SOX, SRY and related proteins. eLS. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, United Kingdom: 10.1002/9780470015902.a0002325.pub2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kwak KJ, Kim JY, Kim YO, Kang H. 2007. Characterization of transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing high mobility group B proteins under high salinity, drought or cold stress. Plant Cell Physiol 48:221–231. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antosch M, Mortensen SA, Grasser KD. 2012. Plant proteins containing high mobility group box DNA-binding domains modulate different nuclear processes. Plant Physiol 159:875–883. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.198283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mead ME. 2015. Unraveling the transcription network regulating sexual development in the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. PhD thesis. University of Wisconsin—Madison, Madison, WI. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hartmann HA, Krüger J, Lottspeich F, Kahmann R. 1999. Environmental signals controlling sexual development of the corn smut fungus Ustilago maydis through the transcriptional regulator Prf1. Plant Cell 11:1293–1305. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.7.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson M, Zaretskaya I, Raytselis Y, Merezhuk Y, McGinnis S, Madden TL. 2008. NCBI BLAST: a better Web interface. Nucleic Acids Res 36:W5–W9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hartmann HA, Kahmann R, Bolker M. 1996. The pheromone response factor coordinates filamentous growth and pathogenicity in Ustilago maydis. EMBO J 15:1632–1641. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swamy BM, Bhat AG, Hegde GV, Naik RS, Kulkarni S, Inamdar SR. 2004. Immunolocalization and functional role of Sclerotium rolfsii lectin in development of fungus by interaction with its endogenous receptor. Glycobiology 14:951–957. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luan R, Liang Y, Chen Y, Liu H, Jiang S, Che T, Wong B, Sun H. 2010. Opposing developmental functions of Agrocybe aegerita galectin (AAL) during mycelia differentiation. Fungal Biol 114:599–608. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fowler TJ, Mitton MF, Rees EI, Raper CA. 2004. Crossing the boundary between the Bα and Bβ mating-type loci in Schizophyllum commune. Fungal Genet Biol 41:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kothe E. 2001. Mating-type genes for basidiomycete strain improvement in mushroom farming. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 56:602–612. doi: 10.1007/s002530100763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brefort T, Müller P, Kahmann R. 2005. The high-mobility-group domain transcription factor Rop1 is a direct regulator of prf1 in Ustilago maydis. Eukaryot Cell 4:379–391. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.2.379-391.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin Y-J, Huang L-H, Huang C-T. 2013. Enhancement of heterologous gene expression in Flammulina velutipes using polycistronic vectors containing a viral 2A cleavage sequence. PLoS One 8:e59099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.NCBI Resource Coordinators. 2017. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D12–D17. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chenna R, Sugawara H, Koike T, Lopez R, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG, Thompson JD. 2003. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res 31:3497–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trifinopoulos J, Nguyen L-T, Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2016. W-IQ-TREE: a fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 44:W232–W235. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen X, Stone M, Schlagnhaufer C, Romaine CP. 2000. A fruiting body tissue method for efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Agaricus bisporus. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:4510–4513. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.10.4510-4513.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Peer AF, Park S-Y, Shin P-G, Jang K-Y, Yoo Y-B, Park Y-J, Lee B-M, Sung G-H, James TY, Kong W-S. 20 July 2011, posting date Comparative genomics of the mating-type loci of the mushroom Flammulina velutipes reveals widespread synteny and recent inversions. PLoS One doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuo C-Y, Chou S-Y, Hseu R-S, Huang C-T. 2010. Heterologous expression of EGFP in Enoki mushroom Flammulina velutipes. Bot Stud 51:303–309. https://ejournal.sinica.edu.tw/bbas/content/2010/3/Bot513-03.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harith N, Abdullah N, Sabaratnam V. 2014. Cultivation of Flammulina velutipes mushroom using various agro‑residues as a fruiting substrate. Pesq Agropec Bras 49:181–188. doi: 10.1590/S0100-204X2014000300004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xie C, Gong W, Yan L, Zhu Z, Hu Z, Peng Y. 2017. Biodegradation of ramie stalk by Flammulina velutipes: mushroom production and substrate utilization. AMB Express 7:171. doi: 10.1186/s13568-017-0480-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2015. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods 12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10:R25–R34. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.