Despite alkylpyrazines' contribution to flavor and their commercial value, the synthesis mechanisms of alkylpyrazines by microorganisms remain poorly understood. This study revealed the substrate, intermediates, and related enzymes for the synthesis of 2,5-dimethylpyrazine (2,5-DMP), which differ from the previous reports about the synthesis of 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine (TTMP). The synthesis mechanism described here can also explain the production of 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine (TMP). The results provide insights into an alkylpyrazine’s synthesis pathway involving l-threonine-3-dehydrogenase as the catalytic enzyme and l-threonine as the substrate.

KEYWORDS: alkylpyrazine; synthesis mechanism; 2,5-dimethylpyrazine; 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine; Bacillus subtilis

ABSTRACT

Alkylpyrazines are important contributors to the flavor of traditional fermented foods. Here, we studied the synthesis mechanisms of 2,5-dimethylpyrazine (2,5-DMP) and 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine (TMP). Substrate addition, whole-cell catalysis, stable isotope tracing experiments, and gene manipulation revealed that l-threonine is the starting point involving l-threonine-3-dehydrogenase (TDH) and three uncatalyzed reactions to form 2,5-DMP. TDH catalyzes the oxidation of l-threonine. The product of this reaction is l-2-amino-acetoacetate, which is known to be unstable and can decarboxylate to form aminoacetone. It is proposed that aminoacetone spontaneously converts to 2,5-DMP in a pH-dependent reaction, via 3,6-dihydro-2,5-DMP. 2-Amino-3-ketobutyrate coenzyme A (CoA) ligase (KBL) catalyzes the cleavage of l-2-amino-acetoacetate, the product of TDH, into glycine and acetyl-CoA in the presence of CoA. Inactivation of KBL could improve the production of 2,5-DMP. Besides 2,5-DMP, TMP can also be generated by Bacillus subtilis 168 by using l-threonine and d-glucose as the substrates and TDH as the catalytic enzyme.

IMPORTANCE Despite alkylpyrazines' contribution to flavor and their commercial value, the synthesis mechanisms of alkylpyrazines by microorganisms remain poorly understood. This study revealed the substrate, intermediates, and related enzymes for the synthesis of 2,5-dimethylpyrazine (2,5-DMP), which differ from the previous reports about the synthesis of 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine (TTMP). The synthesis mechanism described here can also explain the production of 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine (TMP). The results provide insights into an alkylpyrazine’s synthesis pathway involving l-threonine-3-dehydrogenase as the catalytic enzyme and l-threonine as the substrate.

INTRODUCTION

Alkylpyrazines are a class of nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds with alkyl groups on the side chain (Fig. 1A). These compounds generally have pleasant nutty, roasted and toasted flavor characteristics at low odor thresholds (1, 2). Thus, alkylpyrazines are regarded as important aroma compounds and contribute to the unique aroma in raw, thermally processed or fermented foods. Besides aroma contribution, alkylpyrazines also play an important role in the pharmaceutical industry. 2,3,5,6-Tetramethylpyrazine (TTMP) is the active ingredient in the medicinal plant Ligusticum wallichii and has been used to treat several diseases (3, 4). In addition, TTMP can serve as the precursor for synthesizing several other biological materials of value (5, 6). 2,5-Dimethylpyrazine (2,5-DMP) can be oxidized to form 5-methylpyrazine-2-carboxylic acid, which is the intermediate in the synthesis of an antilipolytic drug (7).

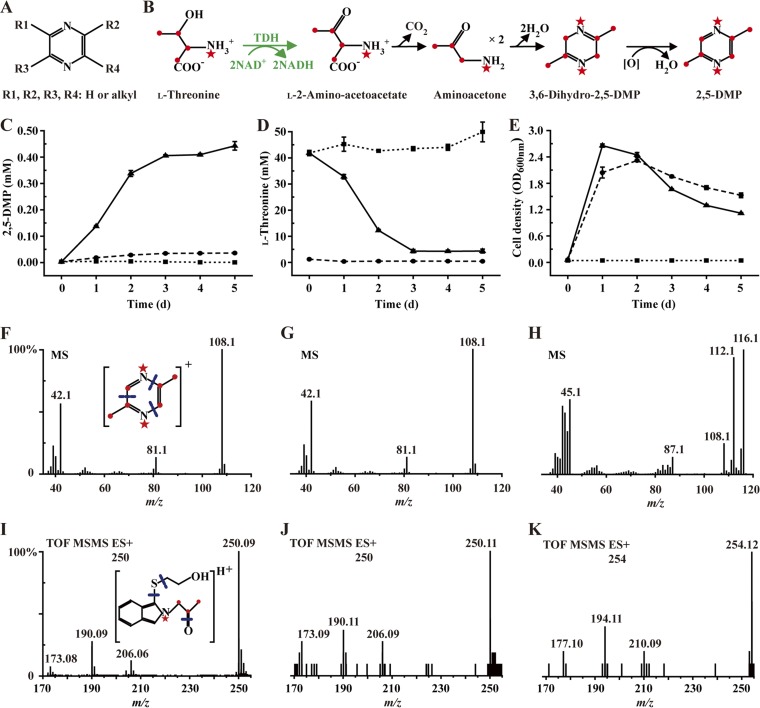

FIG 1.

2,5-Dimethylpyrazine (2,5-DMP) is derived from the metabolism of l-threonine probably via aminoacetone. (A) Structural formula of alkylpyrazine. (B) Proposed formation pathway of 2,5-DMP by Bacillus subtilis (36). ●, 13C; ★, 15N. (C to E) Concentrations of 2,5-DMP (C) and l-threonine (D) and cell growth (E) over the time course of cultivation of B. subtilis 168. ■, LB supplemented with l-threonine; ●, B. subtilis 168 in LB; ▲, B. subtilis 168 in LB supplemented with l-threonine. (F to H) The MS spectrum of 2,5-DMP analyzed by GC-MS. (F) 2,5-DMP standard. (G) B. subtilis 168 in LB supplemented with l-threonine. (H) B. subtilis 168 in LB supplemented with l-[U-13C,15N]threonine. (I to K) The MS spectrum of the aminoacetone derivative analyzed by UPLC-ESI/Q-TOF-MS. (I) Aminoacetone standard. (J) B. subtilis 168 in LB supplemented with l-threonine. (K) B. subtilis 168 in LB supplemented with l-[U-13C,15N]threonine.

Due to the unique aroma contribution of alkylpyrazines, synthesis mechanisms of these compounds in thermally processed foods, such as roasted beef (8), seeds (9), peanuts (10), etc., have been studied. There are two widely accepted mechanisms for the formation of alkylpyrazines in thermally processed foods. One pathway is the Maillard model system. At high temperature (usually above 100°C), free amino acids and the reductones (α-dicarbonyls) that are derived either from the Maillard reaction or the caramelization of carbohydrates, can be converted to α-aminocarbonyls via Strecker degradation. Then α-aminocarbonyls can be condensed to form alkylpyrazines (11–15). In addition, in the Maillard model system, peptides can replace free amino acids to produce alkylpyrazines (16–18). The other widely accepted pathway is ammonia/acyloin reaction, which involves ammonia (released from amino acids) and α-hydroxycarbonyls. α-Hydroxycarbonyls, which can also be derived from caramelization of carbohydrates, can be converted to α-aminocarbonyls with the presence of ammonia and then to alkylpyrazines (19). These two synthesis mechanisms of alkylpyrazines require carbohydrates. In fact, when the carbohydrates are absent, alkylpyrazines can also be generated. Shu found that individual hydroxyl amino acids such as serine and threonine can form alkylpyrazines at high temperature (20).

Dozens of alkylpyrazines have been found in traditional fermented foods, such as Chinese Baijiu (Chinese liquor) (21–23) and soybean-based (24–26) and cocoa bean-based (27, 28) fermented foods. The fermentative condition for traditional fermented foods is standard temperature and pressure, and alkylpyrazines in fermented foods may be produced by microorganisms. Only one alkylpyrazine’s (TTMP) synthesis pathway has been described clearly to date. First, microorganisms metabolize glucose to produce pyruvate by glycolysis. Then pyruvate is converted to acetoin (3-hydroxy-2-butanone) catalyzed by α-acetolactate synthase and α-acetolactate decarboxylase (29–34). As a kind of acyloin, acetoin can react with ammonium (or ammonia) to generate α-hydroxyimine. Subsequently, α-hydroxyimine is converted to 2-amino-3-butanone, which can be condensed spontaneously to form TTMP (32, 33, 35, 36). Thus, carbon and nitrogen sources of TTMP are derived from glucose and free amine, respectively.

2,5-DMP is a valuable alkylpyrazine that be detected in some traditional fermented foods. Bacillus subtilis can accumulate 2,5-DMP by using l-threonine as the substrate (24, 36). In addition, a synthesis pathway from l-threonine to 2,5-DMP has been proposed (Fig. 1B) (36, 37). First, l-threonine is dehydrogenated to form l-2-amino-acetoacetate, and then l-2-amino-acetoacetate is decarboxylated to form aminoacetone. Aminoacetone could be subsequently condensed to 3,6-dihydro-2,5-DMP, and the latter compound can be dehydrogenated to form 2,5-DMP. However, it is not yet clear whether the proposed synthesis pathway is active and what the characteristics of the reactions are.

In this work, we studied the synthesis mechanism of 2,5-DMP using B. subtilis 168, which is the model organism of Bacillus species. B. subtilis can synthesize 2,5-DMP by using l-threonine as the substrate via aminoacetone. The reaction from l-threonine to l-2-amino-acetoacetate is an enzyme catalytic reaction, which is catalyzed by l-threonine-3-dehydrogenase (TDH) (GenBank accession no. NP_389581). l-2-Amino-acetoacetate can spontaneously decarboxylate to form aminoacetone. The reaction from aminoacetone to 2,5-DMP is a pH-dependent nonenzymatic reaction. Inactivation of 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate coenzyme A (CoA) ligase (KBL [GenBank accession no. NP_389582]) improved 2,5-DMP production. More interestingly, this synthesis mechanism can also explain the synthesis of 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine (TMP), another important alkylpyrazine.

RESULTS

2,5-Dimethylpyrazine is derived from the metabolism of l-threonine probably via aminoacetone.

A highly 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine (TTMP)-producing strain has been selected previously from Chinese traditional high-temperature Daqu which is the starter for producing Chinese Baijiu. This strain, identified as Bacillus subtilis XZ1124 (38), can also produce 2,5-dimethylpyrazine (2,5-DMP) and 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine (2,3,5-TMP). B. subtilis XZ1124 could produce 0.20 mM 2,5-DMP after 26 mM l-threonine was consumed (carbon recovery rate of 1.5%), while 0.01 mM 2,5-DMP was produced without l-threonine addition (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). B. subtilis 168, the model strain of the Bacillus genus, was also found that can produce 2,5-DMP, especially after the addition of l-threonine. As shown in Fig. 1C to E, 0.44 mM 2,5-DMP was produced by B. subtilis 168 after 37 mM l-threonine was consumed (carbon recovery rate of 2.3%), while only 0.03 mM 2,5-DMP was produced by B. subtilis 168 cultured in LB medium. l-Threonine concentration in sterile LB medium was changeless (Fig. 1D), which revealed the structure stability of l-threonine. These phenomena suggest that B. subtilis may produce 2,5-DMP by using l-threonine as the substrate. Since genetic manipulation of B. subtilis 168 is feasible, B. subtilis 168 was used in subsequent experiments.

The synthesis pathway of 2,5-DMP from l-threonine was proposed in 1999 (36). As shown in Fig. 1B, l-threonine is initially dehydrogenated to form l-2-amino-acetoacetate, and l-2-amino-acetoacetate undergoes decarboxylation to generate aminoacetone. Then aminoacetone can be cyclized to form 3,6-dihydro-2,5-DMP, which is subsequently dehydrogenated to form 2,5-DMP (Fig. 1B). Thus, l-2-amino-acetoacetate derived from l-threonine may lead to the formation of aminoacetone, 3,6-dihydro-2,5-DMP and finally to 2,5-DMP. However, only the standards of l-threonine and aminoacetone were commercially available. So, whether the l-threonine is the substrate and whether aminoacetone is the intermediate for synthesizing 2,5-DMP were studied initially in this study.

Whole-cell catalysis of strain B. subtilis 168 with l-threonine as the sole substrate was performed. As shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material, after 48 h of incubation, B. subtilis 168 produced 0.27 mM 2,5-DMP by using l-threonine as the sole substrate. In contrast, no 2,5-DMP was produced in catalysis system in the absence of l-threonine or B. subtilis 168. Then, isotopic tracing experiments were performed. B. subtilis 168 was cultivated in LB medium supplemented with l-threonine (8.4 mM) or l-[U-13C,15N]threonine (8.4 mM). After 3 days of cultivation, the culture solution of B. subtilis 168 was analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Peaks which have the same retention time with 2,5-DMP standard (at 13.5 min) were both detected in culture broths of LB medium supplemented with l-threonine or l-[U-13C,15N]threonine (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). However, 2,5-DMP detected in l-threonine addition medium presented a molecular ion at m/z 108 ([M]) (Fig. 1F and G). Meanwhile, 2,5-DMP detected in l-[U-13C,15N]threonine addition medium presented a molecular ion at m/z 116 ([M]+8) (Fig. 1H), which means six carbon atoms and two nitrogen atoms of 2,5-DMP were isotope labeled. Combined with the results of whole-cell catalysis, we confirmed that l-threonine can be the sole substrate for production of 2,5-DMP by B. subtilis.

Aminoacetone in the culture broth of B. subtilis 168 was analyzed by ultraperformance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) after derivatization with o-phthalaldehyde (OPA) and mercaptoethanol (39). The derivatization reaction of aminoacetone is shown in Fig. S4 in the supplemental material. When B. subtilis 168 was cultivated by using LB medium supplemented with l-threonine, an aminoacetone derivative could be detected in the culture broth (retention time at 12.3 min) with the molecular ion at m/z 250 (Fig. 1I and J; Fig. S2). In contrast, when B. subtilis 168 was cultivated by using LB medium supplemented with isotope-labeled l-[U-13C,15N]threonine, the aminoacetone derivative could be detected in the culture broth with the molecular ion at m/z 254 (Fig. 1K). These phenomena suggest that aminoacetone is the intermediate in the formation of 2,5-DMP by B. subtilis.

l-Threonine-3-dehydrogenase (TDH) undergoes the catalytic function in the formation of 2,5-DMP from l-threonine.

It was reported that TDH oxidizes l-threonine with NAD+ as an electron acceptor and forms 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate (l-2-amino-acetoacetate) (40–42), which is unstable and may undergo spontaneous decarboxylation to aminoacetone (43, 44). So, whether TDH undergoes the catalytic function from threonine to aminoacetone for the synthesis of 2,5-DMP was studied. We overproduced a putative TDH from B. subtilis 168 and partially purified it using a HisTrap column (Fig. 2A; see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Enzyme activity of TDH was conducted by measuring the NADH formation rate (absorbance at 340 nm [see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material]). In addition, the concentration of purified TDH was also measured by using the Bradford method (45). In the end, the specific activity of TDH from B. subtilis 168 was calculated to be 0.15 U/mg. In order to detect the catalytic product of TDH, the reaction solution inoculated with TDH, l-threonine, and NAD+ was analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and UPLC-MS in the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode after derivatization with OPA and mercaptoethanol (Fig. S4). Two compounds with elution times of 3.9 and 4.2 min were detected. As expected, the compound eluting at 4.2 min at UPLC-MS is consistent with the aminoacetone derivative (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the peak representing 2,5-DMP, which had an elution time of 3.9 min at GC-MS, was also detected, although the area of 2,5-DMP was lower than detection limit of the 2,5-DMP calibration curve (Fig. 2B).

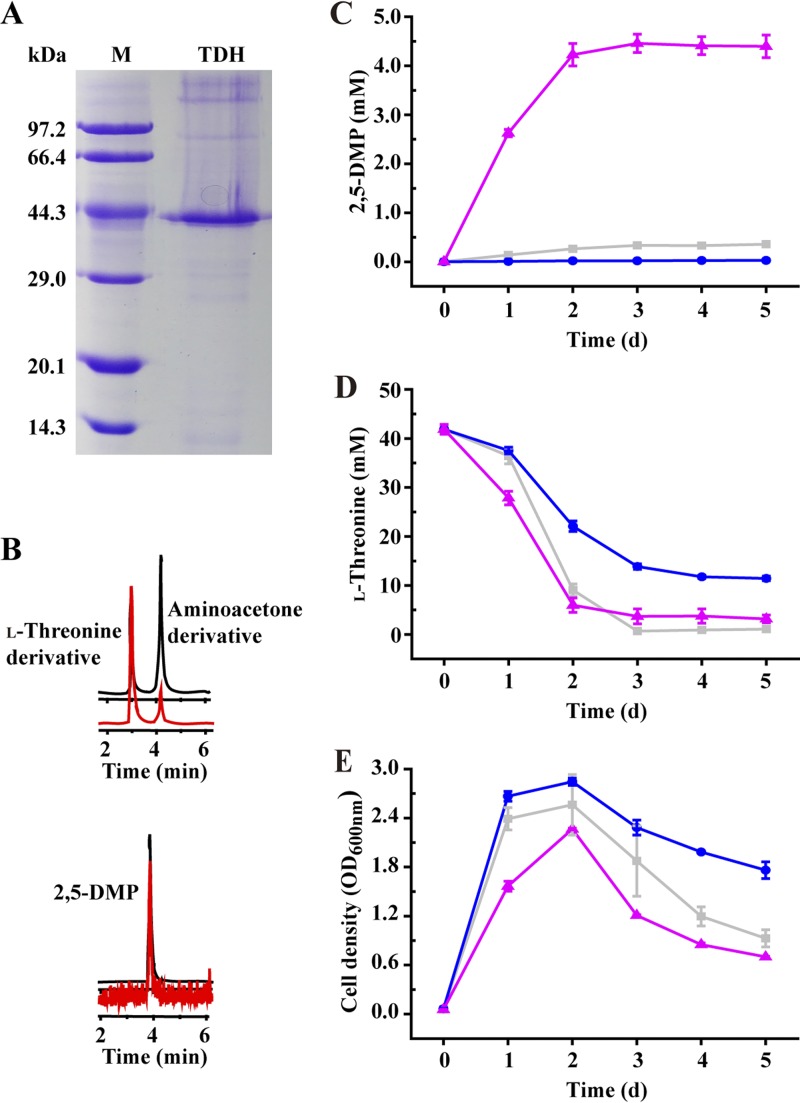

FIG 2.

l-Threonine-3-dehydrogenase (TDH) is the key enzyme for the synthesis of 2,5-DMP in B. subtilis using l-threonine as the substrate. (A) SDS-PAGE of the purified TDH. M, marker. (B) Detection of the l-threonine derivative, aminoacetone derivative, and 2,5-DMP in the TDH-catalyzed l-threonine system by UPLC-TQ-S-MS in the MRM mode. (C to E) Concentrations of 2,5-DMP (C) and l-threonine (D) and cell growth (E) over the time course of cultivation of B. subtilis 168 derivatives. ■, B. subtilis 168/pMA0911; ●, B. subtilis 168 Δtdh; ▲, B. subtilis 168 Δtdh/pMA0911-tdh.

B. subtilis 168 TDH inactivation and complement strains were constructed (see Fig. S7A, C, F, and G in the supplemental material). Cultivation experiments were carried out by using the constructed strains B. subtilis 168/pMA0911, B. subtilis 168 Δtdh, and B. subtilis 168 Δtdh/pMA0911-tdh. As shown in Fig. 2C to E, after 5 days of cultivation, 0.36 mM 2,5-DMP was produced from the control strain B. subtilis 168/pMA0911, with an l-threonine consumption of 41 mM. However, tdh mutant strain B. subtilis 168 Δtdh displayed only 0.03 mM 2,5-DMP production, with similar cell density and l-threonine consumption. When the tdh gene was reintroduced into the tdh mutant strain on a plasmid under a constitutive promoter, in the resulting strain, B. subtilis 168 Δtdh/pMA0911-tdh, the production of 2,5-DMP increased, from 0.03 mM to 4.40 mM (Fig. 2C).

Based on these results, it can be concluded that TDH undergoes the catalytic function in the formation of 2,5-DMP from l-threonine. In addition, the reaction from aminoacetone to 2,5-DMP may be nonenzymatic.

Conversion from aminoacetone to 2,5-DMP is a pH-dependent nonenzymatic reaction.

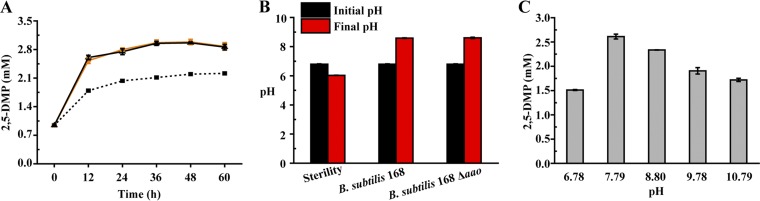

Previous studies demonstrated that aminoacetone can dimerize and dehydrate spontaneously to generate 3,6-dihydro-2,5-DMP, which oxidizes easily to 2,5-DMP (46, 47). These studies indicate that aminoacetone could generate 2,5-DMP by a nonenzymatic reaction. However, another report described that there is an aminoacetone oxidase (AAO) (GenBank accession no. ACA52024) in Streptococcus that catalyzes the condensation of two molecules of aminoacetone to form 3,6-dihydro-2,5-DMP, which subsequently oxidizes to form 2,5-DMP (48). A putative AAO in B. subtilis 168 (GenBank accession no. WP_003229222), which has 45% protein sequence identity to the corresponding AAO from Streptococcus, was recognized. We subsequently constructed an aao mutant strain B. subtilis 168 Δaao (Fig. S7E and I). To study whether the putative AAO catalyzes aminoacetone to 2,5-DMP, strains B. subtilis 168 Δaao and B. subtilis 168 were cultured in LB medium supplemented with 9 mM aminoacetone hydrochloride. As shown in Fig. 3A, the concentration of 2,5-DMP produced by B. subtilis 168 Δaao was similar to that by B. subtilis 168, suggesting that the putative AAO is not responsible for production of 2,5-DMP. However, the 2,5-DMP concentration in B. subtilis 168 or B. subtilis 168 Δaao culture medium was higher than that in sterile culture medium (Fig. 3A). As shown in Fig. 3B, although the initial pH was similar (pH 6.80), the final pHs of the media differed among the different strains and no-strain cultures. Thus, it is reasonable to postulate that the improved pH resulted from strain fermentation may work for the increased concentration of 2,5-DMP. We constructed a batch reaction in test tubes containing 5 ml LB medium supplemented with 9 mM aminoacetone hydrochloride at different pH values. As shown in Fig. 3C (and Table S1 in the supplemental material), more 2,5-DMP was obtained when the LB broth pH was approximately 7.79. Thus, we concluded that conversion from aminoacetone to 2,5-DMP might be a pH-dependent nonenzymatic reaction.

FIG 3.

The conversion from aminoacetone to 2,5-DMP is a pH-dependent nonenzymatic reaction. (A) The formation of 2,5-DMP in different systems. ■, LB supplemented with aminoacetone; ●; B. subtilis 168 Δaao in LB supplemented with aminoacetone; ▲, B. subtilis 168 in LB supplemented with aminoacetone. (B) The initial and final pHs in LB containing aminoacetone with different strains or no strain. (C) Formation of 2,5-DMP from aminoacetone in LB at different initial pHs.

2-Amino-3-ketobutyrate CoA ligase (KBL) can decrease 2,5-DMP production by directing 2,5-DMP production intermediate to glycine.

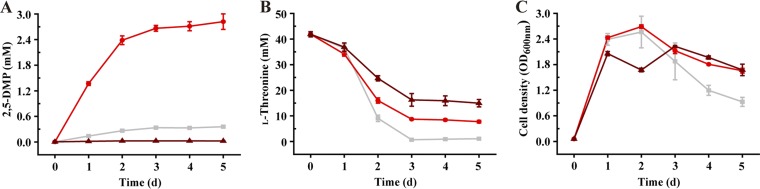

KBL acts in catalyzing the 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate, the product of TDH, to glycine and acetyl-CoA, with the participation of cofactor CoA (49). Thus, we speculate KBL could also participate in the production of 2,5-DMP. In this study, the kbl mutant and complement strains were constructed (Fig. S7B, D, F, and H). Cultivation experiments were carried out by using the constructed strains B. subtilis 168/pMA0911, B. subtilis 168 Δkbl, and B. subtilis168 Δkbl/pMA0911-kbl. Surprisingly, the kbl mutant strain (B. subtilis 168 Δkbl) displayed higher 2,5-DMP production (2.82 mM; carbon recovery rate of 17%) than the control strain B. subtilis 168/pMA0911 (0.36 mM; carbon recovery rate of 1.7%), while the consumption of l-threonine (34 to 40 mM) and cell growth (highest optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 2.4) were not strikingly different between the two strains (Fig. 4A to C). Reintroduction of the gene kbl into B. subtilis 168 Δkbl (B. subtilis 168 Δkbl/pMA0911-kbl) on a plasmid under a constitutive promoter resulted in an obvious decrease in the production of 2,5-DMP (0.03 mM) (Fig. 4C). Thus, according to our data combined with previous reports (50), KBL decreases the accumulation of 2,5-DMP with l-threonine as the substrate in B. subtilis.

FIG 4.

2-Amino-3-ketobutyrate CoA ligase (KBL) can decrease the accumulation of 2,5-DMP by B. subtilis. (A to C) Concentrations of 2,5-DMP (A) and l-threonine (B) and cell growth (C) over the time course of cultivation of B. subtilis 168 derivatives. ■, B. subtilis 168/pMA0911; ●, B. subtilis 168 Δkbl; ▲, B. subtilis 168 Δkbl/pMA0911-kbl.

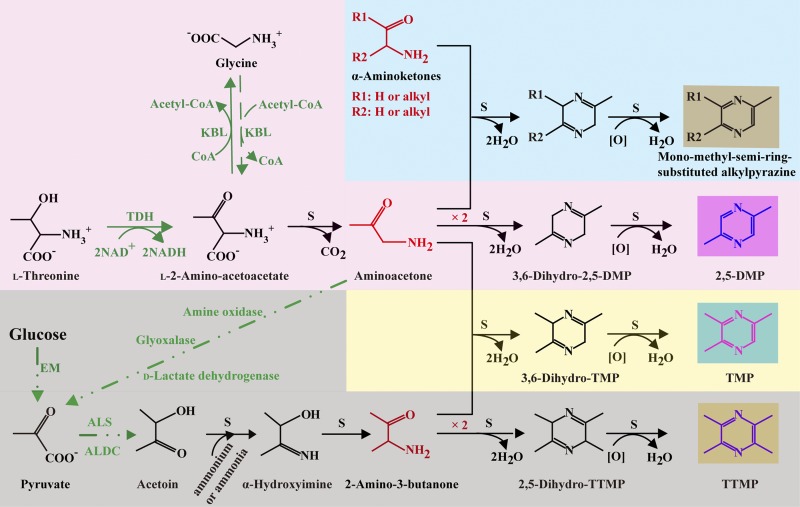

The synthesis mechanism of 2,5-DMP can also explain the production of 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine (TMP).

In this study, the 2,5-DMP synthesis mechanism of B. subtilis has been examined. This synthesis mechanism can explain the production of a class of alkylpyrazines containing a mono-methyl-semicyclic ring theoretically. 2,5-DMP consists of two mono-methyl-semicyclic rings and can be produced using l-threonine as the synthesis substrate. TTMP consists of two dimethyl-semicyclic rings and can be produced using d-glucose as the synthesis substrate. Thus, TMP, which consists of one mono-methyl-semicyclic ring and one dimethyl-semicyclic ring, may be produced with l-threonine and d-glucose as synthesis substrates.

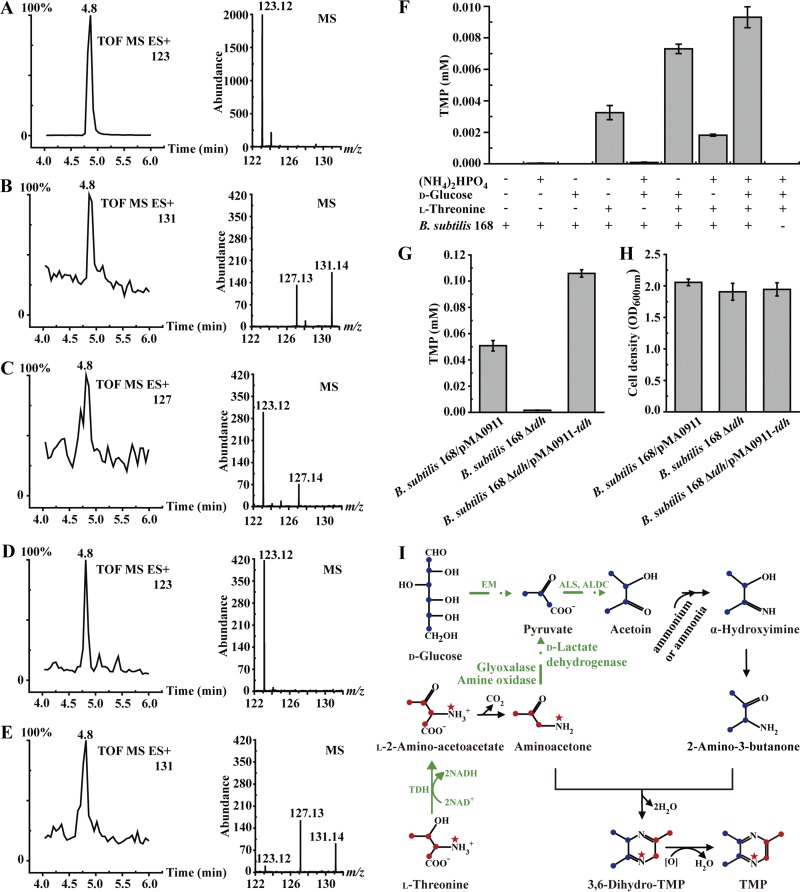

In this study, stable isotope tracing experiments by using l-[U-13C,15N]threonine and/or d-[U-13C]glucose were conducted to detect whether l-threonine and d-glucose are the substrates for synthesizing TMP. As shown in Fig. 5A, the molecular ion of non-isotope-labeled TMP standard is 123. Culture medium (LB medium) supplemented with (NH4)2HPO4, l-[U-13C,15N]threonine, and d-[U-13C]glucose and inoculated with B. subtilis 168 (fermentation for 3 days) yielded a molecular ion of TMP at m/z 131 (Fig. 5B). Moreover, when (NH4)2HPO4, l-threonine and [U-13C]-d-glucose were added to LB medium, a molecular ion of TMP at m/z 127 (Fig. 5C) appeared. When (NH4)2HPO4, l-threonine, and d-glucose were added to LB medium, only the molecular ion of TMP at m/z 123 (Fig. 5D) appeared. Thus, the mono-methyl-semicyclic ring of TMP, containing three carbon atoms and one nitrogen atom, comes from l-threonine. The dimethyl-semicyclic ring of TMP, containing four carbon atoms and one nitrogen atom, comes from d-glucose and (NH4)2HPO4. Nevertheless, when l-[U-13C,15N]threonine and d-glucose were added, the molecular ion at m/z 131 also appeared (Fig. 5E), suggesting that l-threonine can be catabolized to form a d-glucose catabolism intermediate and thus can produce TMP in the absence of d-glucose.

FIG 5.

Synthesis mechanism of 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine (TMP) in B. subtilis. (A to E) The chromatogram and MS spectrum of TMP analyzed by UPLC-ESI/Q-TOF-MS. (A) TMP standard. (B) B. subtilis 168 in LB containing (NH4)2HPO4 supplemented with l-[U-13C,15N]threonine and d-[U-13C]glucose. (C) B. subtilis 168 in LB containing (NH4)2HPO4 supplemented with l-threonine and d-[U-13C]glucose. (D) B. subtilis 168 in LB containing (NH4)2HPO4 supplemented with l-threonine and d-glucose. (E) B. subtilis 168 in LB containing (NH4)2HPO4 supplemented with l-[U-13C,15N]threonine and d-glucose. (F) The production of TMP in LB supplemented with different substrates by B. subtilis 168. (G and H) TMP production (G) and cell growth (H) in LB supplemented with l-threonine, d-glucose, and (NH4)2HPO4 by B. subtilis 168 derivatives. (I) Proposed synthesis pathway of TMP in B. subtilis. ●, 13C; ★, 15N; EM, Embden-Meyerhof pathway; TDH, l-threonine-3-dehydrogenase; ALS, α-acetolactate synthase; ALDC, α-acetolactate decarboxylase.

In addition, whole-cell catalytic experiments were conducted in 10-ml centrifuge tubes containing 42 mM l-threonine and/or 56 mM d-glucose and/or 23 mM (NH4)2HPO4. Concentrations of TMP in samples were determined by using UPLC-MS in MRM mode. As shown in Fig. 5F, the reaction system containing l-threonine, d-glucose, and (NH4)2HPO4 displayed the highest TMP production (0.009 mM). In the absence of l-threonine in the reaction, the concentration of TMP was essentially negligible. In contrast, when l-threonine was the only substrate in the reaction system, 0.003 mM TMP was detected. These results were consistent with the stable isotope tracing experiments and indicated that ammonium salt, l-threonine, and d-glucose can be substrates for the synthesis of TMP, and l-threonine plus ammonium salt can also produce TMP in the absence of d-glucose.

Based on the above results, a semicycle of TMP can be derived from l-threonine. Thus, TDH may play a crucial role in the synthesis of TMP. To detect whether TDH in B. subtilis 168 participates in the synthesis of TMP, the B. subtilis strains 168/pMA0911, 168 Δtdh, and 168 Δtdh/pMA0911-tdh were cultured in LB medium supplemented with l-threonine, d-glucose, and (NH4)2HPO4. As shown in Fig. 5G and H, after 2 days of cultivation at 37°C, the tdh mutant strain B. subtilis 168 Δtdh displayed a sharp decrease in the concentration of TMP (TMP concentration of 0.0002 mM) compared with that of the control strain B. subtilis 168/pMA0911 (TMP concentration of 0.05 mM). Moreover, when the tdh gene was reintroduced to the tdh mutant strain, the resulting B. subtilis strain, 168 Δtdh/pMA0911-tdh, regained the capability of TMP accumulation (0.1 mM). These results suggest that TDH contributes to the formation of TMP with l-threonine as a substrate.

Combining previous reports, a putative synthesis mechanism of TMP is proposed (Fig. 5I). l-Threonine, d-glucose, and ammonium salt are substrates or l-threonine plus ammonium salt are the substrates for the formation of TMP in B. subtilis 168. In the synthesis mechanism of TMP, TDH, which catalyzes the dehydrogenation of l-threonine, is an essential enzyme for synthesizing TMP. Therefore, the synthesis mechanism of 2,5-DMP can also explain the production of TMP by B. subtilis 168.

DISCUSSION

Alkylpyrazines are a class of vital flavoring constituents in traditional fermented foods, such as Chinese Baijiu, soy sauce, and cheese, which are famous models as tractable microbial ecosystems (51, 52). Multiple flavor constituents are the quality indicator of fermented foods and are produced by microorganisms. Thus, researchers have completed multispecies studies to investigate the synthesis pathway of flavor compounds from microorganisms. Omics, an emerging bioinformatic approach, can only be used to investigate the microbial function that has been already known (53). It is essential to study the previously unknown synthesis pathway of flavor compounds by using culturable methods.

Several studies focused on the formation of 2,5-dimethylpyrazine (2,5-DMP) and 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine (TMP) through the Maillard reaction. Lancker et al., found more 2,5-DMP and TMP would be produced from Maillard reactions by using glucose, methylglyoxal, or glyoxal as the carbon source and dipeptides with lysine at N terminus as the nitrogen source (16, 17). Scalone et al. found oligopeptides can also be the substrates for 2,5-DMP production (18). Guo et al. described l-theanine and glucose as being potential substrates for the 2,5-DMP formation during Oolong tea manufacturing processes (15). High-intensity roasted procedures, such as 130°C for 2 h or 180°C for 90 min, are indispensable for these pyrazine-forming reactions described above. However, traditional fermented foods are manufactured under normal temperature and pressure. Thus, microorganisms might play roles in the production of alkylpyrazines in traditional fermented food.

B. subtilis can produce 2,5-DMP by using l-threonine as the substrate. After stable isotope tracing of l-threonine, genetic manipulation and enzyme catalysis, we found that there are two main steps involved in 2,5-DMP formation. The former step is the conversion from l-threonine to aminoacetone catalyzed by l-threonine-3-dehydrogenase (TDH), and the latter pathway is the cyclization and oxidation from aminoacetone to 2,5-DMP, which are nonenzymatic reactions. These are similar with many other heterocyclic compounds, such as 2,3,4,5-tetrapyrazine, rubrolone tropolone alkaloids and artemisinin, which are also formed through the combination of enzymatic and nonenzymatic reactions (54, 55).

In bacteria, l-threonine can be catabolized by threonine dehydratase, threonine aldolase and threonine dehydrogenase (56). In addition, threonine can be assimilated into cellular constituent by protein synthetase. Thus, limited aminoacetone was produced from l-threonine, and it might be the reason why the carbon recovery rate from l-threonine to 2,5-DMP is less than 3% in the wild-type strain of B. subtilis (Fig. 1C). However, conversion from aminoacetone to 2,5-DMP is a nonenzymatic reaction, and this reaction can occur over a range of conditions (data not shown). The carbon recovery rate we detected from aminoacetone to 2,5-DMP reached to 60% to 70% under neutral condition at 37°C (Table S1). Thus, although the concentration of 2,5-DMP is limited, the production of 2,5-DMP from l-threonine by B. subtilis is expected. Recent studies found that 2,5-DMP produced by Bacillus showed strong antifungal activity, which might be the physiological importance of 2,5-DMP production for microorganisms (57, 58).

As shown above, we found the reaction from aminoacetone to 2,5-DMP is nonenzymatic. However, it is difficult for us to determine whether the nonenzymatic reaction occurred inside or outside the cell. Aminoacetone can be detected in the culture broth (Fig. 1), and the higher pH that resulted from B. subtilis fermentation facilitated the formation of 2,5-DMP from aminoacetone (Fig. 3), whereas the intracellular pH of Bacillus is relatively stable. Thus, we speculate that the reaction from aminoacetone to 2,5-DMP might happen outside the cell. Therefore, the electron acceptor during oxidation of 3,6-dihydro-2,5-DMP (the direct product from aminoacetone cyclization) to 2,5-DMP might be oxygen. Aminoacetone can be exported by the bacterial excretion system, cell membrane damage, or cell lysis (59). Whole-cell catalysis of B. subtilis 168 showed that the conversion rate from l-threonine to 2,5-DMP improved over time, probably due to the improved aminoacetone concentration resulted from cell membrane damage or cell lysis.

Both TTMP and 2,5-DMP are formed by a spontaneous condensation reaction from α,β-carbonyl-amino compounds. Thus, it is reasonable to speculate that the other structurally similar compound, TMP, is also formed by the same condensation reaction. TMP consists of a monomethyl and a dimethyl semi-ring, which are constituent parts of 2,5-DMP and TTMP, respectively. The synthesis mechanism of TTMP and 2,5-DMP, including synthesis strain, substrate, and intermediates, may also explain the production of TMP (Fig. 5I). TTMP is synthesized by using d-glucose as the substrate and acetoin as the intermediate. 2,5-DMP can be derived from the metabolism of l-threonine via aminoacetone. Thus, aminoacetone and acetoin might be intermediates for the synthesis of TMP (60). In addition, aminoacetone can be converted into pyruvate via methylglyoxal catalyzed by amine oxidase, glyoxalases and d-lactate dehydrogenase (61–64). Then pyruvate can be converted into acetoin by α-acetolactate synthetase and α-acetolactate decarboxylase, which explained the phenomenon why B. subtilis cultured in medium in the absence of glucose can also produce TMP (Fig. 5E and F).

Alkylpyrazines are important flavor compounds in traditional fermented foods. Chinese Baijiu, a fermented beverage produced by a unique complex process involving the saccharification and spontaneous fermentation by using cereals such as sorghum, barley and pea as raw materials, has a wide variety of alkylpyrazines (21–23, 65). Until now, 19 alkylpyrazines have been identified in Baijiu (23) and 11 of these are mono-methyl-semi-ring-containing alkylpyrazines, including 2-methylpyrazine, 2,5-DMP, 2,6-DMP, TMP, 2-ethyl-5-methylpyrazine, 2-ethyl-6-methylpyrazine, 2,5-dimethyl-3-ethylpyrazine, 3,5-dimethyl-2-ethylpyrazine, 2,5-dimethyl-3-isobutylpyrazine, 2-butyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazine, and 2,5-dimethyl-3-pentylpyrazine (23). As this study has described, TDH is the functional enzyme used to synthesize the mono-methyl-semi-ring of alkylpyrazines, and all TDH-containing microorganisms in the Baijiu-brewing environment (66) might affect the synthesis of these compounds. The phylogenetic distribution of TDH among eight genera of Baijiu-brewing microorganisms (66) is presented in Fig. S8 in the supplemental material. Seven of these bacterial genera, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Lactobacillus, Klebsiella, Pantoea, Kroppenstedtia, and Acinetobacter, and one fungal genus, Aspergillus, were found to have the TDH enzyme. This study provides more knowledge about the flavor source of traditional fermented foods.

Both 2,5-DMP and TMP are flavor compounds of commercial potential. Systematic metabolic engineering could be an effective strategy for the high production of 2,5-DMP (and TMP) from l-threonine. In this study, the inactivation of KBL, which catalyzes a 2,5-DMP production intermediate to glycine, enhanced the production of 2,5-DMP (from 0.36 mM to 2.82 mM), while the carbon recovery rate of 2,5-DMP from l-threonine improved from 1.7% to 17% (Fig. 4). Thus, genetic manipulation strategies may work on improving the titer and yield of 2,5-DMP, like many other secondary metabolites produced by B. subtilis (67).

In this study, the synthesis mechanisms of 2,5-DMP and TMP by B. subtilis have been described (Fig. 6). This provides information about what and how microorganisms may participate in the formation of alkylpyrazines in traditional fermented foods and proposes a possibility for higher-efficiency production of alkylpyrazine by using microorganisms. More synthesis pathways of alkylpyrazine need to be studied.

FIG 6.

Proposed synthesis mechanisms of alkylpyrazines (2,5-DMP, TMP, 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine [TTMP], and alkylpyrazines containing a monomethyl semi-ring) in B. subtilis. EM, Embden-Meyerhof pathway; TDH, l-threonine-3-dehydrogenase; KBL, 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate CoA ligase; ALS, α-acetolactate synthase; ALDC, α-acetolactate decarboxylase; S, spontaneous reaction under standard temperature and pressure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms, plasmids, and medium.

All the microorganisms and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli JM109 was used to maintain and amplify plasmids. E. coli BL21(DE3) was used as a host strain for protein expression. B. subtilis XZ1124 (38) was isolated from the high-temperature Daqu and has been deposited in China Center for Type Culture Collection (CCTCC M208157). Plasmid pET-28a was used for protein expression in E. coli BL21(DE3), and pMA0911 was used for gene complementation in the gene mutant strain. The medium used for gene manipulation was Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (5 g/liter yeast extract, 10 g/liter tryptone, and 10 g/liter NaCl). Kanamycin, ampicillin, and spectinomycin were used at concentrations of 50, 100, and 100 μg/ml, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| BL21(DE3) | F− ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm me131 λ(DE3) | Laboratory stock |

| JM109 | e14- (mcrA) endA1 recA1 hsdR17 (rk− mk+) (lac-proAB) lacIqZ M15 relA1 | Laboratory stock |

| BL21(DE3)/pET-28a-tdh | Recombinant strain for TDH overexpression | This work |

| B. subtilis | ||

| XZ1124 | Wild type | 38 |

| 168 | ΔtrpC2 | BGSC |

| 168 Δtdh | 168 mutant obtained by deletion of tdh | This work |

| 168 Δkbl | 168 mutant obtained by deletion of kbl | This work |

| 168 Δaao | 168 mutant obtained by deletion of aao | This work |

| 168/pMA0911 | 168 with pMA0911 | This work |

| 168 Δtdh/pMA0911-tdh | 168 Δtdh with pMA0911-tdh | This work |

| 168 Δkbl/pMA0911-kbl | 168 Δkbl with pMA0911-kbl | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET-28a | oripBR322 laclq T7P, replicates in E. coli (Kanr) | Novagen |

| pET-28a-tdh | pET-28a derivative for TDH overexpression | This work |

| p7S6 | pMD18-T containing lox71-spc-lox66 cassette | 59 |

| pMA0911 | pMA5 derivative, PHpall ColE1 repB, replicates in E. coli (Ampr) or B. subtilis (Kanr) | Laboratory stock |

| pMA0911-tdh | pMA0911 derivative for gene tdh complementation | This work |

| pMA0911-kbl | pMA0911 derivative for gene kbl complementation | This work |

Kanr, kanamycin resistant; Ampr, ampicillin resistant; spc, spectinomycin resistance gene.

Chemicals and molecular biology reagents.

l-Threonine, isotope-labeled l-threonine, 2,5-dimethylpyrazine (2,5-DMP), 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine (TMP), and casein acid hydrolysate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, China). Isotope-labeled d-glucose was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. Yeast extract, tryptone, and agar were obtained from Oxoid (Hampshire, England). Aminoacetone hydrochloride was purchased from Shu-Ya (Shanghai, China). OPA reagent (concentrated) (o-phthalaldehyde and 3-mercaptopropionic acid in borate buffer) was purchased from Agilent (Beijing, China). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade methanol and acetonitrile were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Shanghai, China). Other chemical reagents were provided by the China National Pharmaceutical Group Corporation (Shanghai, China).

All primers used in this work were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) and are shown in Table 2. FastDigest restriction enzymes were bought from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Shanghai, China), and other molecular biology reagents were purchased from TaKaRa Biotechnology (Dalian, China).

TABLE 2.

Primers and PCR details used in this studya

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| tdh-f | CGCCGGATCCATGCAGAGTGGAAAGATGAAAGC | Amplification of tdh for construction of pET-28a-tdh |

| tdh-r | CGCCAAGCTTTTATGGAATTAAAATTACTTTTCCGC | |

| tdh-f1 | GGAGCGATTTACATATGATGCAGAGTGGAAAGATG | Amplification of tdh for construction of pMA0911-tdh |

| tdh-r2 | CGACTCTAGAGGATCCTTATGGAATTAAAATTACTTTTCCG | |

| kbl-f1 | GGAGCGATTTACATATGATGACGAAGGAATTTGAG | Amplification of kbl for construction of pMA0911-kbl |

| kbl-r2 | CGACTCTAGAGGATCCTTACAATAGCTGGAGCTCCTTTGCC | |

| spc-f | TACCGTTCGTATAGCATACATT | Amplification of spc for the deletion of genes |

| spc-r | TACCGTTCGTATAATGTATGCT | |

| Δtdh-f1 | TCAAAACGAACCTTCCAGTC | Amplification of upstream regions flanking tdh for deletion of tdh |

| Δtdh-r2 | AATGTATGCTATACGAACGGTATCAGGAATGGGAACTTCAGTC | |

| Δtdh-f3 | AGCATACATTATACGAACGGTAATTACCCATCAGTTTCCATTAG | Amplification of downstream regions flanking tdh for deletion of tdh |

| Δtdh-r4 | ATATGCTCCGGCTCTTCAAG | |

| Δtdh-f5 | GCTCAGCGGAGTTGTCATTG | Nested PCR for amplification of fused fragments for deletion of tdh |

| Δtdh-r6 | GGCGCAAATAATCGATCAGC | |

| Δkbl-f1 | GATCAATGGGCACGTCAGAG | Amplification of upstream regions flanking kbl for deletion of kbl |

| Δkbl-r2 | AATGTATGCTATACGAACGGTAAGCTGTTTTATGTCTTGCCA | |

| Δkbl-f3 | GCATACATTATACGAACGGTAAGAATTCGCACGATTATAACAGC | Amplification of downstream regions flanking kbl for deletion of kbl |

| Δkbl-r4 | TCACTTCCTGAATGATATCC | |

| Δkbl-f5 | GTTCAGCGGCATCGTAGAGG | Nested PCR for amplification of fused fragments for deletion of kbl |

| Δkbl-r6 | CGTACAGAATTTGTCACAGC | |

| Δaao-f1 | TATAAAGCACGACCAGCCCT | Amplification of upstream regions flanking aao for deletion of aao |

| Δaao-r2 | AATGTATGCTATACGAACGGTAGCCGATTACGATTACGTCAT | |

| Δaao-f3 | AGCATACATTATACGAACGGTATCATTACTCTTTAAATCTCT | Amplification of downstream regions flanking aao for deletion of aao |

| Δaao-r4 | AACAACATTAACAATCCGGC | |

| Δaao-f5 | TTCAAAATCAAGAATGTCGC | Nested PCR for amplification of fused fragments for deletion of aao |

| Δaao-r6 | AGTAAAAAGAGCACTGTCAC | |

| Δtdh-f | CTCATAAAAGTGAAAGCCGC | Amplification of tdh deletion fragment for verification of tdh deletion |

| Δtdh-r | AACTGATCAACTGAGACACC | |

| Δkbl-f | CAAAAAGTCATTCAGCTATC | Amplification of kbl deletion fragment for verification of kbl deletion |

| Δkbl-r | GGCTTTTCCCTTTGCTACAG | |

| Δaao-f | CTGGCGTGTTGCTGATAGAT | Amplification of aao deletion fragment for verification of aao deletion |

| Δaao-r | GTGACAAGGGCGGAGGTAAT | |

| tdh-F | GATTAAATTAATCGTGGAGCCTCGC | Amplification of tdh fragment for verification of tdh deletion |

| tdh-R | TGTAAATGTACCCGCAATCGTTCTC | |

| kbl-F | ATGACGAAGGAATTTGAGTT | Amplification of kbl fragment for verification of kbl deletion |

| kbl-R | TTACAATAGCTGGAGCTCCTTTGC | |

| aao-F | TTAAATAGACCATCCCCAGAATCC | Amplification of aao fragment for verification of aao deletion |

| aao-R | GGCTGTCAGGAGAAATAACACCCC |

Restriction sites used in this study are shown in bold.

Stable isotope tracing experiments.

Stable isotope tracing experiments were conducted in test tubes (150 mm by 15 mm) containing 5 ml of LB medium supplemented with membrane filtration-sterilized l-[U-13C,15N]threonine (8.4 mM) and/or d-[U-13C]glucose (11 mM). After 3 days of aerobic cultivation of B. subtilis 168 at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm, samples were withdrawn for detection of isotope-labeled compounds. The detection of aminoacetone and TMP was performed by a Waters UPLC-ESI/Q-TOF-MS system equipped with a Waters BEH C18 column (100 mm by 2.1 mm, 1.7-μm particle). Detection of 2,5-DMP was performed by GC-MS (Agilent 6890 gas chromatograph equipped with an Agilent 5975 mass-selective detector). Detection methods are described in the supplemental material in detail.

Cultivation experiments.

Cultivation experiments were conducted in 250-ml shake flasks containing 50 ml of LB medium supplemented with membrane filtration-sterilized l-threonine (42 mM) or aminoacetone (9 mM) as the substrate to study the production of 2,5-DMP by B. subtilis and its derivatives. LB medium supplemented with membrane filtration-sterilized l-threonine (42 mM), d-glucose (56 mM), and (NH4)2HPO4 (23 mM) as the substrates was used to study the formation of TMP by B. subtilis derivatives. B. subtilis and its derivatives were inoculated into medium by 1% and cultured aerobically at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Experiments were conducted in triplicates.

Whole-cell catalysis experiments.

B. subtilis strain 168 was cultured in 250-ml shake flasks containing 50 ml LB medium supplemented with l-threonine (42 mM). After 24 h of aerobic cultivation at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm, cells were collected by centrifugation at 4°C with 10,000 g for 5 min, and then cells were washed twice by sterilized 0.85% NaCl and resuspended to OD600 of 30. For 2,5-DMP production, the catalytic mixture consisted of 800 μl buffer solution (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.85% NaCl, pH 8.60), 100 μl l-threonine (0.42 M) and 100 μl cells (OD600 of 30), while a mixture with cells absent and one with l-threonine absent were the controls. For TMP production, the catalytic mixture consisted of 750 μl buffer solution (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.85% NaCl, pH 8.60), 50 μl l-threonine (0.84 M), 50 μl d-glucose (1.12 M), 50 μl (NH4)2HPO4 (0.46 M), and/or 100 μl cells (OD600 of 30). These experiments were performed in 10-ml centrifuge tubes, and cells were incubated aerobically at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Experiments were conducted in triplicates.

Expression, purification, and catalysis of TDH.

PrimerSTAR Max DNA polymerase was used for PCR. Gene tdh was cloned by using genomic DNA of B. subtilis 168 as the template. Then the tdh fragment and pET-28a were digested by BamHI and HindIII. The digested plasmid pET-28a and gene fragment tdh were ligated by using T4 DNA ligase, forming recombinant plasmid pET-28a-tdh. Then E. coli BL21(DE3) was transformed by pET-28a-tdh for protein expression. The vector pET-28a-tdh isolated from E. coli BL21(DE3) was sequenced by Talen (Wuxi, China). The primers and details of the PCR used in this study are shown in Table 2.

The recombinant E. coli BL21(DE3)/pET-28a-tdh strain was grown in LB medium containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. When the OD600 of the culture reached 0.6, 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) was added to induce protein expression at 17°C with shaking at 200 rpm for a further 12 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 min, washed twice with 0.85% NaCl solution (centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min), suspended with buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0), and subsequently disrupted by sonication in ice water. Then supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 4°C with 10,000 × g for 30 min. The purification of TDH was completed by elution with a gradient ratio of buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 M imidazole, pH 8.0) by using an ATKA purifier supplemented with a HisTrap HP affinity column (5 ml) (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Purified TDH was detected though sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

The TDH activity was assayed by measuring the formation of NADH (absorbance at 340 nm) in a 200-μl reaction mixture. The reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 10.0), 10 mM l-threonine, and 2 mM NAD+ was warmed up for 10 min at 37°C. The reaction was started by adding 0.16 mg purified TDH. One unit of TDH activity was defined as the amount of enzyme needed to reduce 1 μM NAD+ per min at 37°C. The concentration of TDH was measured by Bradford method (45) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Enzyme assays were performed in triplicates.

A catalytic mixture of 1 ml containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 10.0), 10 mM l-threonine, 2 mM NAD+ and 0.8 mg TDH was incubated at 37°C with shaking 200 rpm for 4 h. The reaction system after derivatization with OPA and mercaptoethanol (39) was analyzed by a Waters UPLC-MS system in MRM mode equipped with a Waters BEH C18 column (100 mm by 2.1 mm, 1.7-μm particle). Detection methods are given in detail in the supplemental material.

Mutant and complement strain construction.

Genes were amplified by PCR by using the genomic DNA of B. subtilis 168 as the template, and PrimerSTAR Max DNA polymerase was used for PCR. Taq PCR master mix (DNA polymerase) was used for verification of gene deletion and complementation by PCR.

Gene knockout was performed as described previously with minor modification (68). Upstream and downstream regions (approximately 1,000 bp) flanking the target gene tdh were amplified by PCR. The lox71-spc-lox66 cassette was amplified by PCR with plasmid p7S6 as the template. Purified PCR products were fused by one-step fusion PCR and nested PCR. The nested PCR products were directly used to transform B. subtilis 168 competent cells. The desired transformants were directly screened on LB plates containing antibiotic (100 μg/ml spectinomycin) and were verified by PCR. Gene manipulation of kbl and aao was consistent with that of tdh.

Gene complementation was performed as follows. Plasmid pMA0911, digested by NdeI and BamHI, and amplified gene tdh were ligated by using an In-Fusion HD cloning kit, and the ligation product, pMA0911-tdh, was transformed into E. coli JM109 for plasmid cloning. Subsequently vector pMA0911-tdh isolated from E. coli JM109 was sequenced by Talen (Wuxi, China) and transformed to B. subtilis 168 Δtdh. The desired transformants were directly screened on LB plates containing antibiotic (50 μg/ml kanamycin) and were verified by PCR. Gene manipulation of kbl was consistent with that of tdh. The preparation of B. subtilis 168 competent cells and gene fragment or plasmid transformation were performed according to the methods described by Spizizen (69).

Quantitative analysis methods.

The cell density was measured by monitoring the absorbance at 600 nm. The concentration of 2,5-DMP was measured by using a Waters UPLC I-class system equipped with a Waters BEH C18 column (100 mm by 2.1 mm, 1.7-μm particle) and a UV detector. The concentration of l-threonine was measured by using an HPLC (Agilent 1200) system equipped with an Agilent SB-C18 column (250 mm by 4.6 mm, 5-μm particle) and a UV detector. The samples were automatically derivatized with OPA reagent (concentrated) (o-phthalaldehyde and 3-mercaptopropionic acid in borate buffer) by programming the autosampler (Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Then the concentration of TMP was measured by a Waters UPLC-TQ-S-MS system in MRM mode equipped with a Waters BEH C18 column (100 mm by 2.1 mm, 1.7-μm particle). Yield was calculated as the ratio from the conversion rate to the theoretical maximum conversion rate. The detailed conditions for detection are described in the supplemental material.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31701578 and 31530055), the National First-Class Discipline Program of Light Industry Technology and Engineering (LITE2018-12), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (JUSRP11840).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01807-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Masuda H, Mihara S. 1988. Olfactive properties of alkylpyrazines and 3-substituted 2-alkylpyrazines. J Agric Food Chem 36:584–587. doi: 10.1021/jf00081a044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Müller R, Rappert S. 2010. Pyrazines: occurrence, formation and biodegradation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 85:1315–1320. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2362-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho WK, Wen HL, Lee CM. 1989. Tetramethylpyrazine for treatment of experimentally induced stroke in Mongolian gerbils. Stroke 20:96–99. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang B, You J, Qiao Y, Wu Z, Liu D, Yin D, He H, He M. 2018. Tetramethylpyrazine attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiomyocyte injury via improving mitochondrial function mediated by 14–3-3γ. Eur J Pharmacol 832:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang YJ, Zhao W, Li HM. 2011. Novel tandem biotransformation process for the biosynthesis of a novel compound, 4-(2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine-1)-4′-demethylepipodophyllotoxin. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:3023–3034. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03047-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou P, Du S, Zhou L, Sun Z, Zhuo LH, He G, Zhao Y, Wu Y, Zhang X. 2019. Tetramethylpyrazine-2′O-sodium ferulate provides neuroprotection against neuroinflammation and brain injury in MCAO/R rats by suppressing TLR-4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 176:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmid A, Dordick JS, Hauer B, Kiener A, Wubbolts M, Witholt B. 2001. Industrial biocatalysis today and tomorrow. Nature 409:258–268. doi: 10.1038/35051736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cerny C, Grosch W. 1993. Quantification of character-impact odour compounds of roasted beef. Z Lebensm Unters Forch 196:417–422. doi: 10.1007/BF01190805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu S, Xu T, Akoh CC. 2014. Effect of roasting on the volatile constituents of Trichosanthes kirilowii seeds. J Food Drug Anal 22:310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith AL, Barringer SA. 2014. Color and volatile analysis of peanuts roasted using oven and microwave technologies. J Food Sci 79:C1895–C1906. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koehler PE, Odell GV. 1970. Factors affecting the formation of pyrazine compounds in sugar-amine reactions. J Agric Food Chem 18:895–898. doi: 10.1021/jf60171a041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amrani-Hemaimi M, Cerny C, Fay LB. 1995. Mechanisms of formation of alkylpyrazines in the Maillard reaction. J Agric Food Chem 43:2818–2822. doi: 10.1021/jf00059a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang HI, Hartman TG, Rosen RT, Ho CT. 1993. Formation of pyrazines from the Maillard reaction of glucose and glutamine-amide-15N. J Agric Food Chem 41:2112–2115. doi: 10.1021/jf00035a054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwang HI, Hartman TG, Rosen RT, Lech J, Ho CT. 1994. Formation of pyrazines from the Maillard reaction of glucose and lysine-α-amine-15N. J Agric Food Chem 42:1000–1004. doi: 10.1021/jf00040a031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo X, Song C, Ho CT, Wan X. 2018. Contribution of l-theanine to the formation of 2,5-dimethylpyrazine, a key roasted peanutty flavor in Oolong tea during manufacturing processes. Food Chem 263:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.04.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Lancker F, Adams A, De Kimpe N. 2010. Formation of pyrazines in Maillard model systems of lysine-containing dipeptides. J Agric Food Chem 58:2470–2478. doi: 10.1021/jf903898t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Lancker F, Adams A, De Kimpe N. 2012. Impact of the N-terminal amino acid on the formation of pyrazines from peptides in Maillard model systems. J Agric Food Chem 60:4697–4708. doi: 10.1021/jf301315b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scalone GLL, Lamichhane P, Cucu T, De Kimpe N, De Meulenaer B. 2019. Impact of different enzymatic hydrolysates of whey protein on the formation of pyrazines in Maillard model systems. Food Chem 278:533–544. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shu CK. 1998. Pyrazine formation from amino acids and reducing sugars, a pathway other than Strecker degradation. J Agric Food Chem 46:1515–1517. doi: 10.1021/jf970999i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shu CK. 1999. Pyrazine formation from serine and threonine. J Agric Food Chem 47:4332–4335. doi: 10.1021/jf9813687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan W, Qian MC. 2005. Headspace solid phase microextraction and gas chromatography-olfactometry dilution analysis of young and aged Chinese “Yanghe Daqu” liquors. J Agric Food Chem 53:7931–7938. doi: 10.1021/jf051011k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan W, Qian MC. 2006. Characterization of aroma compounds of Chinese “Wuliangye” and “Jiannanchun” liquors by aroma extraction dilution analysis. J Agric Food Chem 54:2695–2704. doi: 10.1021/jf052635t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan W, Xu Y, Zhang Y. 2007. Characterization of pyrazines in some Chinese liquors and their approximate concentrations. J Agric Food Chem 55:9956–9962. doi: 10.1021/jf071357q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Besson I, Creuly C, Gros JB, Larroche C. 1997. Pyrazine production by Bacillus subtilis in solid-state fermentation on soybeans. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 47:489–495. doi: 10.1007/s002530050961. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dajanta K, Apichartsrangkoon A, Chukeatirote E. 2011. Volatile profiles of thua nao, a Thai fermented soy product. Food Chem 125:464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.09.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoon KH, Chang YI, Lee GH. 2013. Characteristic aroma compounds of cooked and fermented soybean (Chungkook-Jang) inoculated with various bacilli. J Sci Food Agric 93:85–92. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zak DL, Ostovar K, Keeney PG. 1972. Implication of Bacillus subtilis in the synthesis of tetramethylpyrazine during fermentation of cocoa beans. J Food Sci 37:967–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1972.tb03717.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lima LJ, Almeida MH, Nout MJ, Zwietering MH. 2011. Theobroma cacao L., “The Food of the Gods”: quality determinants of commercial cocoa beans, with particular reference to the impact of fermentation. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 51:731–761. doi: 10.1080/10408391003799913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Celińska E, Grajek W. 2009. Biotechnological production of 2,3-butanediol—current state and prospects. Biotechnol Adv 27:715–725. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ji XJ, Huang H, Ouyang PK. 2011. Microbial 2,3-butanediol production: a state-of-the-art review. Biotechnol Adv 29:351–364. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao Z, Xu P. 2007. Acetoin metabolism in bacteria. Crit Rev Microbiol 33:127–140. doi: 10.1080/10408410701364604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao Z, Hou X, Lyu X, Xi L, Zhao J. 2014. Accelerated green process of tetramethylpyrazine production from glucose and diammonium phosphate. Biotechnol Biofuels 7:106. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-7-106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y, Jiang Y, Li X, Sun B, Teng C, Yang R, Xiong K, Fan G, Wang W. 2018. Systematic characterization of the metabolism of acetoin and its derivative ligustrazine in Bacillus subtilis under micro-oxygen conditions. J Agric Food Chem 66:3179–3187. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carroll AL, Desai SH, Atsumi S. 2016. Microbial production of scent and flavor compounds. Curr Opin Biotechnol 37:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rizzi GP. 1988. Formation of pyrazines from acyloin precursors under mild conditions. J Agric Food Chem 36:349–352. doi: 10.1021/jf00080a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larroche C, Besson I, Gros JB. 1999. High pyrazine production by Bacillus subtilis in solid substrate fermentation on ground soybeans. Process Biochem 34:667–674. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(98)00141-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silva-Junior EA, Ruzzini AC, Paludo CR, Nascimento FS, Currie CR, Clardy J, Pupo MT. 2018. Pyrazines from bacteria and ants: convergent chemistry within an ecological niche. Sci Rep 8:2595. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20953-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu BF, Xu Y, Fan WL. 2010. High-yield fermentative preparation of tetramethylpyrazine by Bacillus sp. using an endogenous precursor approach. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 37:179–186. doi: 10.1007/s10295-009-0661-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh SP, Gardinali PR. 2006. Trace determination of 1-aminopropanone, a potential marker for wastewater contamination by liquid chromatography and atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-mass spectrometry. Water Res 40:588–594. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boylan SA, Dekker EE. 1981. l-Threonine dehydrogenase. Purification and properties of the homogeneous enzyme from Escherichia coli K-12. J Biol Chem 256:1809–1815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcus JP, Dekker EE. 1993. pH-dependent decarboxylation of 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate, the unstable intermediate in the threonine dehydrogenase-initiated pathway for threonine utilization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 190:1066–1072. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shimizu Y, Sakuraba H, Kawakami R, Goda S, Kawarabayasi Y, Ohshima T. 2005. l-Threonine dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3: gene cloning and enzymatic characterization. Extremophiles 9:317–324. doi: 10.1007/s00792-005-0447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laver WG, Neuberger A, Scott JJ. 1959. α-Amino-β-keto-acids. Part II. Rates of decarboxylation of the free acids and the behaviour of derivatives on titration. J Chem Soc 0:1483–1491. doi: 10.1039/JR9590001483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elliott WH. 1960. Aminoacetone formation by Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem J 74:478–485. doi: 10.1042/bj0740478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krems IJ, Spoerri PE. 1947. The pyrazines. Chem Rev 40:279–358. doi: 10.1021/cr60126a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robacker DC, Aluja M, Bartelt RJ, Patt J. 2009. Identification of chemicals emitted by calling males of the Sapote fruit fly, Anastrepha serpentina. J Chem Ecol 35:601–609. doi: 10.1007/s10886-009-9631-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molla G, Nardini M, Motta P, D'Arrigo P, Panzeri W, Pollegioni L. 2014. Aminoacetone oxidase from Streptococcus oligofermentans belongs to a new three-domain family of bacterial flavoproteins. Biochem J 464:387–399. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidt A, Sivaraman J, Li Y, Larocque R, Barbosa JA, Smith C, Matte A, Schrag JD, Cygler M. 2001. Three-dimensional structure of 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate CoA ligase from Escherichia coli complexed with a PLP-substrate intermediate: inferred reaction mechanism. Biochemistry 40:5151–5160. doi: 10.1021/bi002204y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marcus JP, Dekker EE. 1993. Threonine formation via the coupled activity of 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate coenzyme A lyase and threonine dehydrogenase. J Bacteriol 175:6505–6511. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6505-6511.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolfe BE, Dutton RJ. 2015. Fermented foods as experimentally tractable microbial ecosystems. Cell 161:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu Y, Tramper J. 2013. Koji—where East meets West in fermentation. Biotechnol Adv 31:1448–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.García-Cañas V, Simó C, Herrero M, Ibáñez E, Cifuentes A. 2012. Present and future challenges in food analysis: foodomics. Anal Chem 84:10150–10159. doi: 10.1021/ac301680q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yan Y, Yang J, Yu Z, Yu M, Ma YT, Wang L, Su C, Luo J, Horsman GP, Huang SX. 2016. Non-enzymatic pyridine ring formation in the biosynthesis of the rubrolone tropolone alkaloids. Nat Commun 7:13083. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Czechowski T, Larson TR, Catania TM, Harvey D, Brown GD, Graham IA. 2016. Artemisia annua mutant impaired in artemisinin synthesis demonstrates importance of nonenzymatic conversion in terpenoid metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:15150–15155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611567113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Willetts AJ, Turner JM. 1970. Threonine metabolism in a strain of Bacillus subtilis. Biochem J 117:27P–28P. doi: 10.1042/bj1170027pb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen H, Xiao X, Wang J, Wu L, Zheng Z, Yu Z. 2008. Antagonistic effects of volatiles generated by Bacillus subtilis on spore germination and hyphal growth of the plant pathogen Botrytis cinerea. Biotechnol Lett 30:919–923. doi: 10.1007/s10529-007-9626-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haidar R, Roudet J, Bonnard O, Dufour MC, Corio-Costet MF, Fert M, Gautier T, Deschamps A, Fermaud M. 2016. Screening and modes of action of antagonistic bacteria to control the fungal pathogen Phaeomoniella chlamydospora involved in grapevine trunk diseases. Microbiol Res 192:172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rahhal DA, Turner JM, Willetts AJ. 1967. The role of aminoacetone in l-threonine metabolism by Bacillus subtilis. Biochem J 103:73P. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dickschat JS, Wickel S, Bolten CJ, Nawrath T, Schulz S, Wittmann C. 2010. Pyrazine biosynthesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Eur J Org Chem 2010:2687–2695. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201000155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Green ML, Elliott WH. 1964. The enzymic formation of aminoacetone from threonine and its further metabolism. Biochem J 92:537–549. doi: 10.1042/bj0920537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Green ML, Lewis JB. 1968. The oxidation of aminoacetone by a species of Arthrobacter. Biochem J 106:267–270. doi: 10.1042/bj1060267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cooper RA, Anderson A. 1970. The formation and catabolism of methylglyoxal during glycolysis in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett 11:273–276. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(70)80546-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kosmachevskaya OV, Shumaev KB, Topunov AF. 2015. Carbonyl stress in bacteria: causes and consequences. Biochemistry (Mosc) 80:1655–1671. doi: 10.1134/S0006297915130039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao T, Chen S, Li H, Xu Y. 2018. Identification of 2-hydroxymethyl-3,6-diethyl-5-methylpyrazine as a key retronasal burnt flavor compound in soy sauce aroma type Baijiu using sensory-guided isolation assisted by multivariate data analysis. J Agric Food Chem 66:10496–10505. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b03980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang X, Du H, Zhang Y, Xu Y. 2017. Environmental microbiota drives microbial succession and metabolic profiles during Chinese liquor fermentation. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e02369-17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02369-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu Q, Zhi Y, Xu Y. 2019. Systematically engineering the biosynthesis of a green biosurfactant surfactin by Bacillus subtilis 168. Metab Eng 52:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yan X, Yu HJ, Hong Q, Li SP. 2008. Cre/lox system and PCR-based genome engineering in Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:5556–5562. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01156-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spizizen J. 1958. Transformation of biochemically deficient strains of Bacillus subtilis by deoxyribonucleate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 44:1072–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.10.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.