Abstract

Vitamin D exerts several immunological functions in addition to its homeostatic functions on calcium and bone metabolism. Current data show that relative vitamin D deficiency (< 75 nmol/l 25-hydroxyvitamin D) as well as acquired seasonal vitamin D deficiency (< 50 nmol/l) are frequent in Germany. As confirmed by our own data, UV exposure plays a major role for maintenance of vitamin D status, e.g., in patients with UV-triggered diseases, vitamin D deficiency is more frequent, even throughout the year. The beneficial impact of vitamin D on immune functions is highlighted by epidemiologic, genetic, and experimental evidence. In the past years, numerous publications have presented associations between vitamin D deficiency, on the one hand, and severity and prevalence of allergic asthma in children and adults, on the other hand.

Keywords: Key words vitamin D, calcitriol, immunomodulation, B cells

German version published in Allergologie, Vol. 34, No. 11/2011, pp. 538-542

Introduction

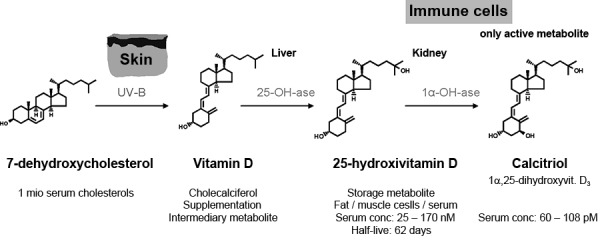

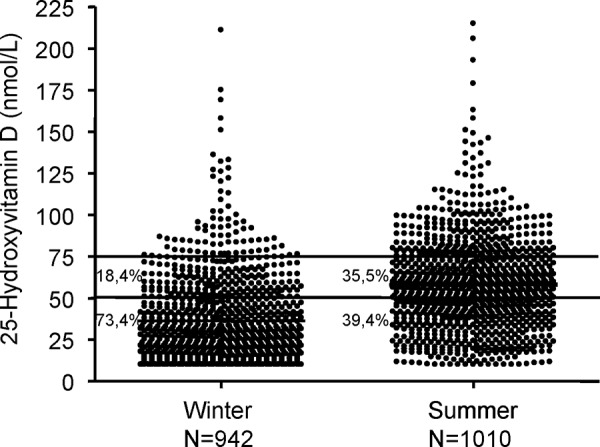

Vitamin D is a steroid hormone produced by the human body from 7-dehydrocholesterol when exposure to UV radiation is present [20]. After enzymatic hydroxylation, it is available in its active form 1α25-hydroxyvitamin D (also called calcitriol) (Figure 1) [20]. It is essential for bone homeostasis as it promotes the resorption of nutritional calcium in the intestine and the kidney [19]. Although today the nutritional situation in the general population is very good, a relative vitamin D deficiency can occur, particularly in winter. A report by Hinzpeter et al. [18], for example, shows that in more than 80% of Germans the daily vitamin D intake with nutrition is below the recommended dose of 5 mg/day. Accordingly, more than 55% of Germans have a relative vitamin D deficiency (serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D < 50 nmol/l) [18]. Current research shows an increasing frequency of relative vitamin D deficiency over the past decade despite the widespread use of vitamin D supplementation [27]. It is very probable that an insufficient UV exposition due to indoor working and increasing use of sunscreens plays an important role [27]. Our own investigation in more than 1,900 patients from Berlin [16] showed that in summer a relative vitamin D deficiency was present in 39.4% of the investigated patients and in winter, where there is only little UV radiation, this rate was as high as 73.4% (Figure 2) [16]. In the human body, vitamin D is mainly produced by UV radiation biosynthesis [21]. In autoimmune patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus, who have to avoid UV exposure due to its disease-promoting effects, a relative vitamin D deficiency is present in 85.7% of patients, even in the summer months, and in winter this rate increases to 97.1% [16]. These data underline that a relative vitamin D deficiency is frequent in Germany, particularly in individuals whose daily exposure to UV radiation is limited due to various reasons.

Figure 1. Vitamin D is a secosteroid hormone.

Figure 2. Relative vitamin D deficiency is frequent nowadays.

Vitamin D and immune system

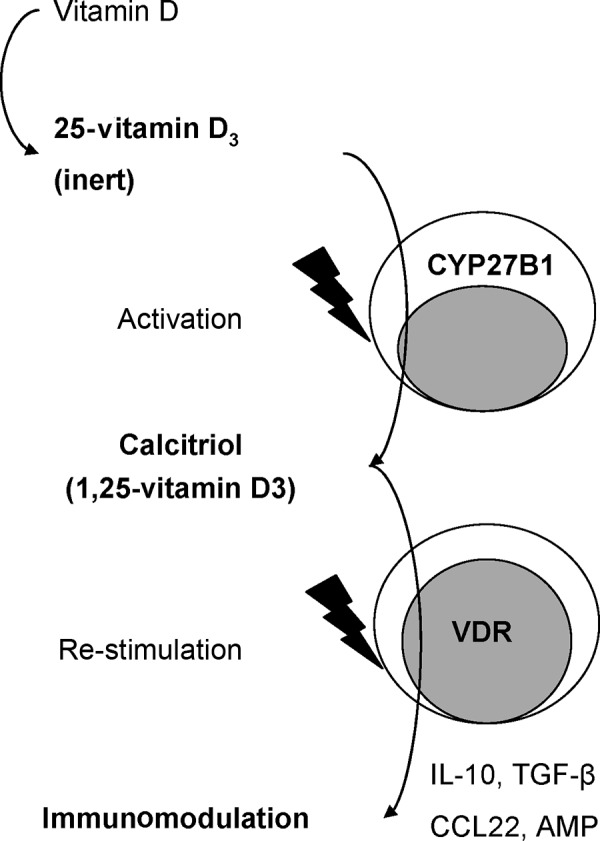

Extensive investigation has suggested an immunomodulatory effect of vitamin D [2, 5, 13, 31]. It also seems to play a role in allergic diseases like allergic bronchial asthma [24, 26]. Epidemiological data show that in the northern parts of the USA a higher prevalence of allergic diseases is present than in the southern parts where there is more UV radiation [7]. Numerous reports suggest a relationship between vitamin D deficiency and the prevalence of allergic diseases as well as a relationship with the severity of allergic asthma and a hyperreactive bronchial system in children, adolescents [6, 9], and adults [25]. Maternal vitamin D supplementation was shown to reduce the prevalence of juvenile wheezing in 3-year-old children [8]. However, the existing data is not unambiguous [22, 40]. It is thought that vitamin D deficiency increases glucocorticoid resistance, as an increased glucocorticoid consumption in the body and a reduced pulmonary function could be shown in vitamin D-deficient children and adults [37, 38]. Furthermore, gene analyses support the hypothesis that vitamin D plays a role in the pathogenesis of allergic asthma. For example, point mutations in the vitamin D receptor gene with a possible loss of function were found in two independent cohorts in the USA [33, 34], but not in a comparable German cohort [39]. The therapeutic use of vitamin D is limited by its hypercalcemic side effects. Nevertheless, the administration of 2 × 0.25 mg calcitriol p.o. for 7 days resulted in an improvement of glucocorticoid resistance in asthma patients, probably due to the induction of IL-10 producing regulatory Tr1 cells [42]. In parallel, increased IL-10 serum concentrations were measured in patients with congestive heart failure after supplementation with 2,000 IU of vitamin D [36]. Also, in patients with multiple sclerosis, an increase of the TGF-β production by CD4 T-helper cells could be detected after the administration of 1,000 IU/day of vitamin D [28], and after high-dose vitamin D supplementation even positive effects on disease severity could be demonstrated [23]. Vitamin D can act directly on immune cells, like antigen-presenting cells, but also on T and B lymphocytes [1, 29, 31]. Among the numerous possible effects are an altered, pro-tolerogenic activation of dendritic cells [3] or the regulation of the humoral immune response [12]. Our own investigation showed that vitamin D, on the one hand, inhibits IgE production, e.g., in B cells [14] and, on the other hand, induces the tolerogenic cytokine IL-10 (Figure 3) [15]. Interestingly, B cells can independently produce active calcitriol [15] so that immunoregulatory effects on B cells can also be obtained by supplementation of the precursor form. In a first clinical investigation, we could demonstrate that the supplementation of 2,000 IU of vitamin D in winter significantly increases the vitamin D concentration, and that this does not negatively (i.e., in the sense of an immunosuppression) influence a robust recall response, as measured by peripheral immune responses at the T cell and B cell level [17]. Our further investigation showed that even a supplementation of up to 8,000 IU during the winter months results in the normalization of the vitamin D level without having side effects, while immune cells are specifically modulated (Drozdenko et al., unpublished data).

Figure 3. Autocrine calcitriol synthesis and effects in immune cells.

Vitamin D analogs

Due to its hypercalcemic effects, the therapeutic use of vitamin D is limited [2, 29]. Thus, synthetic derivatives have been developed in which the calcium-mobilizing effects are dissociated from the immunologic effects. These kinds of calcitriol analogs are already being used in clinical practice for the topic therapy of psoriasis vulgaris (a chronic inflammatory skin disease) [29]. The exact molecular mechanism of these derivatives has not yet been fully elucidated, but cell-specific effects have been described. The calcitriol analog ZK191784, for example, does not have calcium-resorbing effects on intestinal mucosal cells [32], but it has anti-inflammatory effects on T cells [43]. Our own investigation shows that in a murine model the systemic IgE response could be reduced by systemic treatment with a low-calcemic calcitriol analog [12]. Even very structurally different derivatives can be immunologically effective; the calcitriol derivative BXL-219, for example, prevents experimentally induced Type 1 diabetes [4], and another derivative, ZK156979, inhibits experimental colitis [11]. In conclusion, these data underline the complex effect of vitamin D receptors on the immune response. Future data will demonstrate the therapeutic benefit of derivatives for the treatment of immune-mediated diseases in humans.

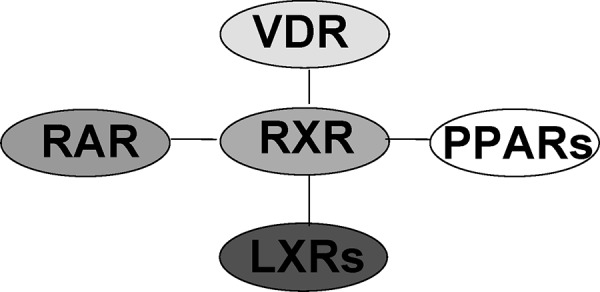

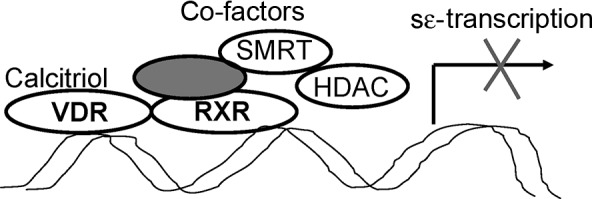

Nuclear hormone receptor ligands control IgE response

Vitamin D binds to its receptor (VDR) in the cytosol, and after translocation of this calcitriol-VDR complex into the cell nucleus, numerous genes are activated or inhibited [13]. In earlier investigations we could show that vitamin D is not the only nuclear hormone receptor ligand inhibiting IgE production. Other members of this family have the same effect: retinoids [41], liver X receptor ligands [14, 30], and PPARs [10, 35] (Figure 4). Recently, we could confirm these in-vitro findings in the mouse model [12]. This may be the basis for an innovative therapeutic approach to use vitamin D in the treatment of allergic diseases. The fact that vitamin D inhibits the transcription factor NFκB, which is essential for the switching of the IgE isotype class, seems to play an important role in the mechanism [14]. Our further investigation demonstrated that the vitamin D receptor can inhibit the switching of the isotype class to IgE directly in the IgE switch promoter (e-germline promoter) by recruiting inhibitory molecules (Figure 5) [30]. Future studies will have to clarify whether this leads to a stable or unstable modulation of the allergic immune response, and how this could be used for the prevention or treatment of allergic diseases.

Figure 4. Family of nuclear hormone receptors.

Figure 5. Inhibition of IgE isotype class switching by interaction of the vitamin D receptor in the e-germline promoter.

Conclusion and perspectives

Vitamin D deficiency is very common in higher latitudes and can be relevant for the development of osteoporosis and immunologic diseases as vitamin D can have numerous protective and immunomodulatory effects. Vitamin D or its precursors might be beneficial for the prevention and therapy of diseases with a modified immune response, and this potential should be investigated in future clinical studies.

References

- 1. Adams JS Chen H Chun R Ren S Wu S Gacad M Nguyen L Ride J Liu P Modlin R Hewison M Substrate and enzyme trafficking as a means of regulating 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D synthesis and action: the human innate immune response. J Bone Miner Res. 2007; 22: V20–V24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adams JS Hewison M Unexpected actions of vitamin D: new perspectives on the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008; 4: 80–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adorini L Tolerogenic dendritic cells induced by vitamin D receptor ligands enhance regulatory T cells inhibiting autoimmune diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003; 987: 258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adorini L Amuchastegui S Corsiero E Laverny G Le Meur T Penna G Vitamin D receptor agonists as anti-inflammatory agents. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2007; 3: 477–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adorini L Penna G Control of autoimmune diseases by the vitamin D endocrine system. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008; 4: 404–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brehm JM Celedón JC Soto-Quiros ME Avila L Hunninghake GM Forno E Laskey D Sylvia JS Hollis BW Weiss ST Litonjua AA Serum vitamin D levels and markers of severity of childhood asthma in Costa Rica. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009; 179: 765–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Camargo CA Clark S Kaplan MS Lieberman P Wood RA Regional differences in EpiPen prescriptions in the United States: the potential role of vitamin D. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007; 120: 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Camargo CA Rifas-Shiman SL Litonjua AA Rich-Edwards JW Weiss ST Gold DR Kleinman K Gillman MW Maternal intake of vitamin D during pregnancy and risk of recurrent wheeze in children at 3 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007; 85: 788–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chinellato I Piazza M Sandri M Peroni DG Cardinale F Piacentini GL Boner AL Serum vitamin D levels and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in children with asthma. Eur Respir J. 2011; 37: 1366–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dahten A Koch C Ernst D Schnöller C Hartmann S Worm M Systemic PPARgamma ligation inhibits allergic immune response in the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2008; 128: 2211–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Daniel C Schlauch T Zügel U Steinmeyer A Radeke HH Steinhilber D Stein J 22-ene-25-oxa-vitamin D: a new vitamin D analogue with profound immunosuppressive capacities. Eur J Clin Invest. 2005; 35: 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hartmann B Heine G Babina M Steinmeyer A Zugel U Radbruch A Targeting the vitamin D receptor inhibits the B cell-dependent allergic immune response. Allergy. 2010; epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13. Hayes CE Nashold FE Spach KM Pedersen LB The immunological functions of the vitamin D endocrine system. Cell Mol Biol. 2003; 49: 277–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heine G Anton K Henz BM Worm M 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits anti-CD40 plus IL-4-mediated IgE production in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 2002; 32: 3395–3404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heine G Niesner U Chang HD Steinmeyer A Zügel U Zuberbier T Radbruch A Worm M 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) promotes IL-10 production in human B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008; 38: 2210–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heine G Lahl A Müller C Worm M Vitamin D deficiency in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus is prevalent throughout the year. Br J Dermatol. 2010; 163: 863–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heine G Drozdenko G Lahl A Unterwalder N Mei H Volk H-D Dörner T Radbruch A Worm M Efficient tetanus toxoid immunization on vitamin D supplementation. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011; 65: 329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hintzpeter B Mensink GB Thierfelder W Müller MJ Scheidt-Nave C Vitamin D status and health correlates among German adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008; 62: 1079–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Holick MF Resurrection of vitamin D deficiency and rickets. J Clin Invest. 2006; 116: 2062–2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holick MF Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357: 266–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hollis BW Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels indicative of vitamin D sufficiency: implications for establishing a new effective dietary intake recommendation for vitamin D. J Nutr. 2005; 135: 317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hyppönen E Sovio U Wjst M Patel S Pekkanen J Hartikainen AL Järvelinb MR Infant vitamin d supplementation and allergic conditions in adulthood: northern Finland birth cohort 1966. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004; 1037: 84–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kimball SM Ursell MR O’Connor P Vieth R Safety of vitamin D3 in adults with multiple sclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007; 86: 645–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lange NE Litonjua A Hawrylowicz CM Weiss S Vitamin D, the immune system and asthma. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2009; 5: 693–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li F Peng M Jiang L Sun Q Zhang K Lian F Litonjua AA Gao J Gao X Vitamin D deficiency is associated with decreased lung function in Chinese adults with asthma. Respiration. 2011; 81: 469–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Litonjua AA Weiss ST Is vitamin D deficiency to blame for the asthma epidemic? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007; 120: 1031–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Looker AC Pfeiffer CM Lacher DA Schleicher RL Picciano MF Yetley EA Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status of the US population: 1988-1994 compared with 2000-2004. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008; 88: 1519–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mahon BD Gordon SA Cruz J Cosman F Cantorna MT Cytokine profile in patients with multiple sclerosis following vitamin D supplementation. J Neuroimmunol. 2003; 134: 128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. May E Asadullah K Zügel U Immunoregulation through 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its analogs. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2004; 3: 377–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Milovanovic M Heine G Hallatschek W Opitz B Radbruch A Worm M Vitamin D receptor binds to the ε germline gene promoter and exhibits transrepressive activity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 126: 1016–1023, 1023.e1-1023.e4.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mora JR Iwata M von Andrian UH Vitamin effects on the immune system: vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008; 8: 685–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nijenhuis T van der Eerden BCJ Zügel U Steinmeyer A Weinans H Hoenderop JGJ van Leeuwen JP Bindels RJ The novel vitamin D analog ZK191784 as an intestine-specific vitamin D antagonist. FASEB J. 2006; 20: 2171–2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Poon AH Laprise C Lemire M Montpetit A Sinnett D Schurr E Hudson TJ Association of vitamin D receptor genetic variants with susceptibility to asthma and atopy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004; 170: 967–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Raby BA Lazarus R Silverman EK Lake S Lange C Wjst M Weiss ST Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms with childhood and adult asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004; 170: 1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rühl R Dahten A Schweigert FJ Herz U Worm M Inhibition of IgE-production by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands. J Invest Dermatol. 2003; 121: 757–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schleithoff SS Zittermann A Tenderich G Berthold HK Stehle P Koerfer R Vitamin D supplementation improves cytokine profiles in patients with congestive heart failure: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006; 83: 754–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Searing DA Zhang Y Murphy JR Hauk PJ Goleva E Leung DY Decreased serum vitamin D levels in children with asthma are associated with increased corticosteroid use. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 125: 995–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sutherland ER Goleva E Jackson LP Stevens AD Leung DY Vitamin D levels, lung function, and steroid response in adult asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010; 181: 699–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wjst M Variants in the vitamin D receptor gene and asthma. BMC Genet. 2005; 6:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wjst M The vitamin D slant on allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2006; 17: 477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Worm M Krah JM Manz RA Henz BM Retinoic acid inhibits CD40 + interleukin-4-mediated IgE production in vitro. Blood. 1998; 92: 1713–1720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xystrakis E Kusumakar S Boswell S Peek E Urry Z Richards DF Adikibi T Pridgeon C Dallman M Loke TK Robinson DS Barrat FJ O’Garra A Lavender P Lee TH Corrigan C Hawrylowicz CM Reversing the defective induction of IL-10-secreting regulatory T cells in glucocorticoid-resistant asthma patients. J Clin Invest. 2006; 116: 146–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zügel U Steinmeyer A Giesen C Asadullah K A novel immunosuppressive 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 analog with reduced hypercalcemic activity. J Invest Dermatol. 2002; 119: 1434–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]