Abstract

Background and Aims:

Obesity is still a major health issue worldwide and bariatric surgeries are now considered one of the most effective ways to manage morbid obesity. Women who are obese in their reproductive age appear to be representing the majority of the patients seeking bariatric surgeries, accounting for (80%). The aim of this study is to assess women's awareness level of obstetric and gynecological impact of bariatric surgery on their health.

Settings and Design:

A cross-sectional study was conducted using an online survey.

Methods:

Online survey was used to collect data which was distributed through social media. Questions regarding the level of knowledge were included along with sociodemographic characteristics of the population.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software was used to conduct the statistics analysis.

Results:

The survey elicited a total of (457) valid responses that were analyzed. The majority of responses were from married women (66.3%). Most common age group where those from (15 to 24) years. However, nearly about three-quarters of participants were found to have poor knowledge (73.1%) and only small percentage had a good level of knowledge (3.3%) and the rest of the participants were in the moderate group. Further analysis showed that good knowledge was among those who have consulted a physician, underwent bariatric surgery, whom source of information was the internet, and whom had more than one source.

Conclusion:

The level of knowledge regarding the obstetric and gynecological impact among females was found to be poor in the eastern region of Saudi Arabia.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, eastern region, gynecological impact, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Obesity is still a major health issue worldwide and the number of affected individuals is in rise.[1,2] It is defined as body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2, and it can affect individuals of all ages, including women of reproductive age.[3] A national multistage survey that was conducted in Saudi Arabia showed that women have a higher obesity rate than men, accounted for (33.5% and 24.1%, respectively) and the overall obesity rate was (28.7%).[4] Unfortunately, dieting and behavioral modifications are relatively ineffective in patients with morbid obesity. Until now, surgical intervention “Bariatric surgeries” is the only effective approach for long-term treatment of morbid obesity.[1,2] It is estimated that about (340,768) bariatric surgeries were performed globally in 2011, of which (7000) were done in Saudi Arabia.[5]

Women who are obese in their reproductive age appeared to be representing the majority of the patients seeking bariatric surgeries accounting for (80%).[1] Obesity is considered the leading cause of comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus type II, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis and obstructive sleep apnea.[4] It is well known that maternal obesity is associated with increased risks of adverse pregnancy events on both mother and fetus. For instance, gestational diabetes, hypertension, miscarriage, macrosomia, congenital malformations, preterm birth, stillbirth and operative deliveries.[6,7] In addition, obesity and overweight play a role in polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and menstrual disturbance.[8] Studies have shown reformative menstrual cycles and resolution of hirsutism after bariatric surgeries for patients who were diagnosed with PCOS.[9,10] Furthermore, multiple studies have reported a decrease in the risk of macrosomia, large for gestational age, gestational diabetes and hypertension in women who have underwent bariatric procedures.[6,11,12] However, increase risk of small for gestation was noticed.[6,13] Studies have shown improved fertility and sexual desire after bariatric surgery,[14] though these surgeries might negatively affect the efficacy of some contraceptive methods.[15,16,17]

There are different types of bariatric surgeries that are known to cause specific nutritional deficiencies.[18] Restrictive surgeries such as, laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB) has often increased the risk of folate and thiamin deficiency. Malabsorptive procedures such as, Biliopancreatic diversion (BPD) have risk of vitamin A, D and E deficiencies. While phylloquinone, iron, thiamin, folate, calcium and vitamin D deficiencies are commonly seen in patients post Roux-Y gastric Bypass (RYGB).[18] These deficiencies can cause serious neonatal adverse events. For instance, visual impairment, intracranial hemorrhage, neurological and developmental impairment and neural tube defects[18,19] primary care physician play an important role in caring for patient post-operatively to optimize their conditions afterward in order to gain the most benefits of the surgery.[20]

In the literature, and as far as we know, there are no articles regarding the awareness of the obstetrical and gynaecological impact of Bariatric surgeries. Thus, the aim of this study was to assess the level of awareness, and knowledge of the obstetrical and gynaecological impact of Bariatric surgeries among women in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia.

Methods

Subjects

This is a cross-sectional study targeting women whose residence is in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Women who live in other provinces, male gender and illiterate women were excluded. The sample size was calculated by Epi info application and planned to be minimum of (384) and it was increased to (460) to compensate for incomplete surveys, and missing data. Three responses were excluded due to incomplete data and inappropriate answers, which left (457) responses for analysis. The sample size was calculated with frequency of (50%) at precision of (5) and (95%) confidence interval.

The questionnaire

The questionnaire included many variables to reach the targeted objectives of the study. Quantitative variables were age, height and weight. Categorical variables were marital status, educational level, occupation, history of bariatric surgery and information source about bariatric surgeries. While dependent variables included knowledge and awareness level. The Questionnaire was written after extensive research in the literature and it included 14 close ended questions regarding obstetric and gynecological impact of bariatric surgeries to establish women awareness and knowledge about these effects.

Data collection

The data collection took place over 1 month period from February until March 2019 and the survey was closed to avert further responses when the calculated sample size was achieved. The questionnaire was designed as an online survey distributed through social media. Furthermore, the questionnaire was tested by a group of 15 women to see the language and general exactitude of the questions and modifications were done accordingly.

Data analysis

The collected data was stored in an Excel sheet and the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software was used to conduct the statistical analysis. Frequency tables along with graphs were used to demonstrate the characteristics of the participants.

Defining knowledge level of the obstetric and gynecological impact of bariatric surgery, respondents were divided into three groups depending on the number of correct answers. Good knowledge 10 answers, poor knowledge 5 answers and moderate knowledge 6 and 9. The associations between age, marital status, educational level, BMI, history of bariatric surgery, having previous consultation with physician regarding bariatric surgery and the source of information with level of awareness were assessed using Chi-square test, and P value of 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The ethical approval was obtained from the research committee in Imam Abdulrahman bin Faisal University for doing a cross-sectional study in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia using an online survey. In addition, the online survey contained a statement explaining the nature and the purpose of the study to gain consent. The participants were invited through a welcoming message clarifying that only females of the eastern province can participate in the study.

Results

A total of (457) responses were included in the analysis. The majority of responses were from married women (66.3%), (30.2%) were single, (2.8%) were separated and (0.7%) were widows. Regarding the employment status; (24.9%) were students, (25.6%) were employed in non-healthcare fields, (6.1%) were employed in the health care field, (6.3%) were retired and (37%) were unemployed. The mean height and weight among participants were (1577 cm and 6919 kg, respectively). Other socio-demographic characteristics (Age, BMI and educational level) are displayed in [Table 1].

Table 1.

Summary of rates of selected socio-demographic characteristics among participants

| Character | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 15-24 | 30.4% (n=139) |

| 25-34 | 26.3% (n=120) |

| 35-44 | 25.2% (n=115) |

| 45-54 | 14% (n=64) |

| More than 55 | 4.2% (n=19) |

| Body mass index (BMI) | |

| Underweight | 7.9% (n=36) |

| Normal BMI | 30.9% (n=141) |

| Overweight | 25.4% (n=116) |

| Obesity class I | 20.4% (n=93) |

| Obesity class II | 8.3% (n=38) |

| Obesity class III | 7.2% (n=33) |

| Educational level | |

| Elementary school | 0.9% (n=4) |

| Intermediate school | 5% (n=23) |

| High school | 20.4% (n=93) |

| University (bachelor and above) | 73.7% (n=337) |

The most common age group of whom have undergone bariatric procedures is (25-44) years and this relation was found to be statistically significant (P value = 0.003). Other correlations between marital status, BMI, and educational level in patients whom underwent bariatric procedures did not show any significant statistical values.

Although about (9%) of the respondents reported that they have consulted a physician regarding bariatric procedures, only (3.5%) had actually undergone one. Gastric sleeve was the most common procedure, followed by gastric bypass and gastric balloon, see [Table 2]. In those women who have consulted a physician, (51.2%) have agreed that the physician have explained the side effects and discussed the possible complications of the intervention.

Table 2.

Number of participants underwent bariatric surgery and frequency of the types of procedures

| Item | % (n) |

|---|---|

| History of undergoing bariatric surgeries | |

| Yes | 3.5% (n=16) |

| No | 96.5% (n=441) |

| Type of surgeries | |

| Gastric balloon | 0.4% (n=2) |

| Gastric band | 0.2% (n=1) |

| Gastric sleeve | 1.8% (n=8) |

| Gastric bypass | 0.9% (n=4) |

| No surgery | 96.5% (n=441) |

| More than one | 0.2% (n=1) |

Many respondents (29.8%) reported that online websites and social media were their main source of information regarding bariatric surgeries and only (2.2%) proclaimed that physicians were their source. Moreover, (16%) had the information from friends and family and (16.6%) retrieved their information from multiple sources, while one third of the participants (35.4%) did not attempt searching for any information.

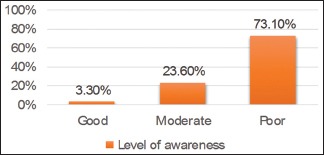

Regarding the awareness level, nearly about three quarters of participants were found to have poor knowledge (73.1%) and only small percentage are those with good level of knowledge (3.3%) and the rest of the participants were in the moderate group, [Graph 1]. Further analysis found that good knowledge was among those who have consulted a physician, underwent bariatric surgery, whom source of information was the internet and whom had more than one source (P value = 0.000). In addition to that, students’ level of awareness was higher than other groups (P value = 0.031). However, further analysis regarding awareness level and its relation to age, BMI, marital status and educational level did not show any statistical significance.

Graph 1.

Level of awareness among participants

Generally, there were poor knowledge among the participants regarding the rate of macrosomia, congenital anomalies and vitamin deficiencies after undergoing bariatric procedures as they reported that they do not know, responses are presented in [Table 3].

Table 3.

Participants’ responses to questions related to bariatric surgery effects

| Item | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Do the pregnant women need a nutrition specialist follow up after bariatric surgeries? | |

| Yes | 58.2 (n=266) |

| No | 2.6% (n=12) |

| I do not know | 39.2% (n=179) |

| Do the rates of macrosomia decreases after bariatric surgeries? | |

| Yes | 10.3% (n=47) |

| No | 9.8% (n=45) |

| I do not know | 79.9% (n=365) |

| Are foetuses of women who underwent bariatric surgeries are of increase risk of vitamin deficiency ? | |

| Yes | 21% (n=96) |

| No | 9.6% (n=44) |

| I do not know | 69.4% (n=317) |

| Do bariatric surgeries increase the rates of congenital anomalies? | |

| Yes | 3.7% (n=17) |

| No | 19.9% (n=91) |

| I do not know | 76.4% (n=349) |

| Do the rates of abortion get lower after bariatric surgeries? | |

| Yes | 12.5% (n=57) |

| No | 9.0% (n=41) |

| I do not know | 77.2% (n=353) |

| Dose women with polycystic ovary disease patients improve after bariatric surgeries? | |

| Yes | 37.0% (n=169) |

| No | 3.5% (n=16) |

| I do not know | 59.5% (n=272) |

Discussion

Bariatric surgeries induce tremendous responses on women's health.[21] The research hypothesis is that women in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia have a good level of knowledge about the effects of weight reduction surgeries on their health. Literature showed that the knowledge regarding obesity and bariatric surgeries are still low among health care practitioners.[22] The general population is not expected to have a better knowledge than health field workers.

Our study results indicate a poor knowledge among the majority of the targeted population. However, participants who have undergone bariatric surgery have more knowledge than the general population and health care workers. This is similar to the literature, where doctors in Greece were found to have poor knowledge regarding bariatric surgeries.[22] Students in different specialties in our study had a better knowledge. Moreover, in a study done targeting final year medical students in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia which tested their knowledge regarding obesity and bariatric surgeries found that they have a low level of knowledge.[23]

However, in a study done in 2019, assessing patient's perception of their primary care doctors regarding their opinions, support and knowledge about bariatric surgery. The results showed that most of the patients perceived their doctors as supportive and knowledgeable.[24]

In Turkey, Sertac et al. has conducted a study to assess the level of knowledge regarding obesity, BMI and bariatric surgery. The results have shown that a minimum number of respondents (13.4%) knew what BMI was and were aware of their own BMI. Surprisingly, (15.1%) of the sample had never heard about bariatric surgeries before. On the other hand, those who have heard about bariatric surgeries, did not know the details about the types, techniques and complications of surgery. In the same study, television was the main source of information for the studied population.[25] However, in our community, internet and social media were the main sources of information. Although there was no significant coloration between BMI and the level of knowledge in this study, unexpectedly people who have normal BMI have better knowledge than people with high BMI.

Regarding participants’ response to those questions used to assess their knowledge, when asked about the indication of bariatric surgeries, near half of the participants (41.1%) agreed that BMI more than 40 without having chronic diseases is an indication for bariatric surgeries. However, only (36.3%) of participants answered “yes” that having BMI of more than 35 along with a chronic disease is also an indication for bariatric surgeries. Worldwide, an individual with BMI more than 40 without chronic diseases or with BMI of more than 35 with a chronic disease would be eligible to undergo such intervention.[21]

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), women should postpone pregnancy for at least (12-18) months post bariatric surgeries to prevent consequences of rapid weight loss.[26] In our study, about one third of the respondents (33.3%) thought that a period ranged from (12-18) months post-surgery would be appropriate, and (0.7%) felt that getting pregnant within first year would be fine and (66.1%) reported that they do not know. Therefore, Patient should be well educated regarding contraception after surgery, primary care physician can help in developing appropriate contraceptive strategy.[27]

In perspective to the question about the need of nutritionist visit during pregnancy post bariatric surgery, the research team excluded it from the analysis due to insufficient evidence.[19]

Benefits and complication of these interventions is not only limited to women, but individuals of general population are also affected. Early assessment and long term monitoring of different post-operative changes and complications can be carried out by a primary care physician as a part of a multidisciplinary team along with surgeons, dietitians and other physicians involved in patient care.[28]

In conclusion, our results indicate a poor level of knowledge regarding the obstetric and gynecological impact of bariatric surgeries among females in the eastern region of Saudi Arabia. It is highly recommended to implant awareness programs targeting the general population and females in particular. It is also recommended to improve the quality of physician's education to bariatric clinic visitors.

Limitation

There was no similar studies that assess the knowledge of the effects of bariatric surgeries in this country, so there was a difficulty in comparing our results with other studies which have similar population characteristic and background.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen M, Pories W, Fahrbach K, et al. Bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–37. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spyropoulos C, Kehagias I, Panagiotopoulos S, Mead N, Kalfarentzos F. Revisional bariatric surgery. Arch Surg. 2010;145:173. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaska L, Kobiela J, Abacjew-Chmylko A, Chmylko L, Wojanowska-Pindel M, Kobiela P, et al. Nutrition and pregnancy after bariatric surgery. ISRN Obes. 2013;2013:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2013/492060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Memish Z, El Bcheraoui C, Tuffaha M, Robinson M, Daoud F, Jaber S, et al. Obesity and associated factors — Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E174. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchwald H, Oien D. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg. 2013;23:427–36. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0864-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson K, Cnattingius S, Näslund I, Roos N, Trolle Lagerros Y, Granath F, et al. Outcomes of pregnancy after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:814–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kjaer M, Nilas L. Pregnancy after bariatric surgery-A review of benefits and risks. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92:264–71. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrmann D. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1223–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jamal M, Gunay Y, Capper A, Eid A, Heitshusen D, Samuel I. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass ameliorates polycystic ovary syndrome and dramatically improves conception rates: A 9-year analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:440–44. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butterworth J, Deguara J, Borg C. Bariatric surgery, polycystic ovary syndrome, and infertility. J Obes. 2016;2016:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2016/1871594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aricha-Tamir B, Weintraub A, Levi I, Sheiner E. Downsizing pregnancy complications: A study of paired pregnancy outcomes before and after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:434–9. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke AE, Bennett WL, Jamshidi RM, Gilson MM, Clark JM, Segal JB, et al. Reduced incidence of gestational diabetes with bariatric surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lesko J, Peaceman A. Pregnancy outcomes in women after bariatric surgery compared with obese and morbidly obese controls. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:547–54. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318239060e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marceau P, Kaufman D, Biron S, Hould F, Lebel S, Marceau S, et al. Outcome of pregnancies after biliopancreatic diversion. Obes Surg. 2004;14:318–24. doi: 10.1381/096089204322917819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerrits E, Ceulemans R, van Hee R, Hendrickx L, Totté E. Contraceptive treatment after biliopancreatic diversion needs consensus. Obes Surg. 2003;13:378–82. doi: 10.1381/096089203765887697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deitel M. Pregnancy after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 1998;8:465–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham Y, Wilkes S, Mansour D, Small P. Contraceptive needs of women following bariatric surgery. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2014;40:241–44. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2014-100959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jans G, Matthys C, Bogaerts A, Lannoo M, Verhaeghe J, Van der Schueren B, et al. Maternal micronutrient deficiencies and related adverse neonatal outcomes after bariatric surgery: A systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2015;6:420–9. doi: 10.3945/an.114.008086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelizzo G, Calcaterra V, Fusillo M, Nakib G, Ierullo A, Alfei A, et al. Malnutrition in pregnancy following bariatric surgery: Three clinical cases of fetal neural defects. Nutr J. 2014;13:59. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Busetto L, Dicker D, Azran C, Batterham R, Farpour-Lambert N, Fried M, et al. Practical recommendations of the obesity management task force of the European association for the study of obesity for the post-bariatric surgery medical management. Obes Facts. 2017;10:597–632. doi: 10.1159/000481825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The role of bariatric surgery in improving reproductive health. 2015;17:1–10. Available from: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/ guidelines-research-services/guidelines/sip17/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zacharoulis D, Bakalis V, Zachari E, Sioka E, Tsimpida D, Magouliotis, D, et al. Current knowledge and perception of bariatric surgery among Greek doctors living in Thessaly. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2017;11:138–45. doi: 10.1111/ases.12436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nawawi A, Arab F, Linjawi H, Fallatah H, Alkhaibari R, Jamal W. An evaluation of knowledge regarding surgical treatment of obesity among final year medical students and recent graduate physicians from King Abdulaziz University. Med Ed Publish. 2017;1:1–16. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312957036 . [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kallies K, Borgert A, Kothari S. Patient perceptions of primary care providers’ knowledge of bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:S153. doi: 10.1111/cob.12297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sertaç AG, Tonguç UY, Turgay Ş, Oktay Y, Sertaç K, Nihat ZU, et al. Obesity and bariatric surgery awareness in the Kocaeli province, a leading industrial city in Turkey. Turk J Surg. 2018;34:165–8. doi: 10.5152/turkjsurg.2018.3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin: Bariatric surgery and pregnancy 105. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1405–13. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ac0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jagadesham V, Sloan M, Ackroyd R. Bariatric surgery: Implications for primary care. Br J Med Med Res. 2014;64:384–5. doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X680797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore M, Hopkins J, Wainwright P. Primary care management of patients after weight loss surgery. BMJ. 2016;352:i945. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]