Abstract

Objective:

To estimate the rates of suicide and self-harm among recent immigrants and to determine which immigrant-specific risk factors are associated with these outcomes.

Methods:

Population-based cohort study using linked health administrative data sets (2003 to 2017) in Ontario, Canada which included adults ≥18 years, living in Ontario (N = 9,055,079). The main exposure was immigrant status (long-term resident vs. recent immigrant). Immigrant-specific exposures included visa class and country of origin. Outcome measures were death by suicide or emergency department visit for self-harm. Cox proportional hazards estimated adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results:

We included 590,289 recent immigrants and 8,464,790 long-term residents. Suicide rates were lower among immigrants (n = 130 suicides, 3.3/100,000) than long-term residents (n = 6,354 suicides, 11.8/100,000) with aHR 0.3, 95% CI, 0.2 to 0.3. Male–female ratios in suicide rates were attenuated in immigrants. Refugees had 2.1 (95% CI, 1.3 to 3.6; rate 6.1/100,000) and 2.8 (95% CI, 2.5 to 3.2) times the likelihood of suicide and self-harm, respectively, compared with nonrefugee immigrants. Self-harm rate was lower among immigrants (n = 2,256 events, 4.4/10,000) than long-term residents (n = 68,039 events, 9.7/10,000 person-years; aHR 0.3; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.3). Unlike long-term residents, where low income was associated with high suicide rates, income was not associated with suicide among immigrants and there was an attenuated income gradient for self-harm. Country of origin-specific analyses showed wide ranges in suicide rates (1.4 to 9.9/100,000) and self-harm (1.8 to 14.9/10,000).

Conclusion:

Recent immigrants have lower rates of suicide and self-harm and different sociodemographic predictors compared with long-term residents. Analysis of contextual factors including immigrant class, origin, and destination should be considered for all immigrant suicide risk assessment.

Keywords: immigrants, suicide, self-harm, refugees

Abstract

Objectif:

Estimer les taux de suicide et d’automutilation chez les immigrants récents et déterminer quels facteurs de risque propres aux immigrants sont associés à ces résultats.

Méthodes:

Une étude de cohorte dans la population utilisant des ensembles de données de santé administratives couplées (2003-2017) en Ontario, Canada. Des adultes ≥ 18 ans habitant en Ontario (n = 9 055 079). L’exposition principale était le statut d’immigrant (résident de longue durée c. immigrant récent). Les expositions propres aux immigrants incluaient la catégorie de visa et le pays d’origine. Les mesures des résultats étaient le décès par suicide ou une visite au service d’urgence pour automutilation. Les hasards proportionnels de Cox ont servi à estimer les rapports de risque ajustés (RRa) et les intervalles de confiance (IC) à 95 %.

Résultats:

Nous avons inclus 590 289 immigrants récents et 8 464 790 résidents de longue durée. Les taux de suicide étaient plus faibles chez les immigrants (n = 130 suicides, 3,3/100 000) que chez les résidents de longue durée (n = 6354 suicides, 11,8/100 000) avec un RRa de 0,3 et un IC à 95 % de 0,2 à 0,3. Les rapports hommes-femmes des taux de suicide étaient atténués chez les immigrants. Les réfugiés avaient 2,1 fois (IC à 95 % 1,3 à 3,6; taux 6,1/100 000) et 2,8 fois (IC à 95 % 2,5 à 3,2) la probabilité du suicide et de l’automutilation, respectivement, comparé aux immigrants non réfugiés. Le taux d’automutilation était plus faible chez les immigrants (n = 2256 occurrences, 4,4/10 000) que chez les résidents de longue durée (n = 68 039 occurrences, 9,7/10 000 années-personnes; RRa 0,3; IC à 95 % 0,3 à 0,3). Contrairement aux résidents de longue durée, le revenu élevé à l’échelle du quartier était associé à des taux de suicide élevés chez les immigrants et il y avait une tranche de revenu atténuée pour l’automutilation. Les analyses spécifiques du pays d’origine indiquaient de vastes écarts des taux de suicide (1,4-9,9/100 000) et d’automutilation (1,8-14,9/10 000).

Conclusion:

Les immigrants récents ont des taux plus faibles de suicide et d’automutilation, et des prédicteurs sociodémographiques différents comparativement aux résidents de longue durée. L’analyse des facteurs contextuels, dont la catégorie d’immigrant, l’origine et la destination devrait être envisagée pour toute évaluation des risques de suicide chez les immigrants.

Introduction

As the number of immigrants and refugees continues to grow worldwide, so too does our attention to mental health outcomes of these populations.1 Globally, suicide is a leading cause of preventable and premature death.2 Attempted suicide and other self-harm behavior are common reasons for visiting an emergency department (ED) and for hospitalization.3–5 Sociodemographic risk factors have been identified for suicide and suicide-related behavior including male sex (suicide), female sex (self-harm), middle age (suicide), early adulthood (self-harm), low income, and being unmarried.6–10 Emerging evidence suggests that immigrant youth in Canada are at lower risk of suicide and self-harm compared with native-born,11 but the converse has been reported among adult immigrants in other industrialized countries.1,12,13 Immigrants to Canada may experience good mental health outcomes due to the “healthy immigrant effect”14,15—that is, immigrants arrive in better health than their native-born counterparts—and Canada’s immigration policies that select for a large proportion of immigrants who are able to contribute to Canada’s economy. However, immigrants to Canada may have more difficulty accessing mental healthcare services as outpatients.16,17 Suicide and self-harm rates in adult immigrants to Canada are not known, and analysis of contextual factors related to immigration and suicide-related behavior is scant among immigrants to Western countries.14,18 Substantial heterogeneity in rates of mental illness within immigrant populations exists, and traditional risk factors for mental illness and other poor health outcomes apply differently to immigrants than to native-born populations.19–22

Suicide rates in Canada are 11 to 12 per 100,000 population, and 45 Canadians are hospitalized each day for self-inflicted injuries.23,24,25 Despite suicide prevention campaigns and increased investment in mental health awareness, support, and treatment, these deaths and injuries continue to occur with little improvement over time.11,26,27 Since these outcomes are considered preventable to some extent, there are opportunities to develop targeted interventions for suicide and self-harm prevention in specific at-risk populations.

Immigration can be a stressful time with major changes to an individual or family that may impact well-being. Immigrants, especially those who come as refugees, may face social marginalization with existing support networks broken, underemployment, or economic hardship, which could act as suicide and self-harm risk factors.28 Conversely, they may encounter hope, opportunity, and success following settlement, which may, in turn, result in lower suicide and self-harm rates.

Canada has one of the highest rates of foreign-born in the world (21.9%), second only to Australia.29 The majority (∼60%) of immigrants to Canada come through an economic class visa, granted for individuals and their families who have skills and ability to contribute to Canada’s economy (e.g., skilled workers). A subset of these include business class immigrants (∼2% of immigrants) who are individuals and their families who may obtain permanent residence based on their ability to become economically established in Canada (e.g., investors, entrepreneurs, self-employed people). Family class immigrants (sponsored by family members already in Canada) make up approximately 30% of immigrants, followed by the smallest group, refugees (10%).29 Ontario, Canada’s most populous province (∼13 million persons) receives half of Canada’s immigrants who come from over 150 source countries and almost all settle in urban areas. Thus, Ontario is an ideal setting to study heterogeneity in mental health outcomes in immigrant populations.29

Understanding how immigration and immigration-related factors are associated with suicide and self-harm risk has been recognized as a research priority30 and is important for optimizing health service delivery and immigrant settlement supports. The objectives of this study were to estimate the rates of suicide and self-harm among adult recent immigrants compared to long-term residents of Canada and to determine which immigrant-specific risk factors are associated with suicide and self-harm. We hypothesized that while immigrants will have a lower risk of suicide and self-harm compared with long-term residents, sociodemographic predictors of suicide and self-harm in immigrants will be different from the general population. We also expect to identify high-risk immigrants by country of origin and refugee status who might require specialized interventions that consider the context of their immigration.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a population-based cohort study of suicide and ED visits for self-harm among long-term resident adults living in Ontario between 2003 and 2012 and among recent immigrants who arrived during this period. Individuals were identified through records from Ontario’s health registry, the Registered Persons Database (RPDB). Health care in Canada is publicly funded through provincial ministries of health at no personal cost to individuals for most physician and hospital services. Public funding extends to immigrants who have obtained permanent residency (i.e., naturalized citizens) within 3 months of arrival. We linked records using unique, encoded identifiers from multiple health and other administrative databases available at ICES.

Data Sources

We used the Immigration Refugee and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) Permanent Resident Database to obtain immigration information. The IRCC Permanent Resident Database contains individual-level data on all immigrants who landed (i.e., migrated directly to and received permanent residence) in Ontario since 1985 and includes immigration (i.e., immigration class, country of birth, and landing date) and nonimmigration (i.e., education, marital status) characteristics. The IRCC Permanent Resident database has an overall linkage rate of 86% obtained using probabilistic and deterministic record linkage with some variability by region of origin.31 We used the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System to ascertain visits to EDs for self-harm and the Ontario Registrar General Vital Statistics—Deaths (ORGD) registry to ascertain suicides. Sociodemographic information including age, sex, and postal code were obtained from the RPDB and linked to Statistics Canada’s Postal Code Conversion File to obtain area-based information including neighborhood-level income and rurality.

Study Population

We included all adults (18 years and older) alive, living in Ontario, and eligible for provincial health care as of the study index date. Individuals who had missing sex or an invalid health card number required for database linkages were excluded. Recent immigrants were included if they had an IRCC record and their first date of provincial health insurance eligibility occurred between April 1, 2003, and December 31, 2012. For recent immigrants, the index date was the date they first obtained eligibility for provincially funded health care. For long-term residents, the index date was a randomly chosen date from a uniform distribution between April 1, 2003, and December 31, 2012. We then excluded individuals with IRCC records with a date of landing between 1985 (start of database) and 2003 to exclude immigrants who had been in Canada for longer than 10 years.

Individuals were followed for self-harm from their study entry until their first self-harm event, death, loss of provincial health insurance eligibility, or end of study (March 31, 2017). Individuals were followed for suicide from their study entry until death, loss of provincial health insurance eligibility, or end of study for which there is suicide data available (December 31, 2014). Having a self-harm event did not preclude individuals from being followed for a suicide event.

Exposure Variables

Immigration status (visa class) was the main exposure variable and included refugees, economic class, business class, and family class immigrants. Other immigration-related covariates included region of birth and country of birth. Sociodemographic characteristics included age, sex, neighborhood-level income quintile measured at the dissemination area level (neighborhoods of 400 to 700 persons), rurality measured using the Rurality Index of Ontario.32 Neighborhood-level measures of socioeconomic status (e.g., income) have been associated with mental health system use and outcomes.33,34 For immigrants ≥22 years on arrival, education and marital status were also measured. Marital status and education are not available in existing linked databases for long-term residents and were therefore not included in adjusted models.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures were both completed suicides and self-harm visits to an ED, analyzed separately. Suicide was ascertained from validated codes using ORGD where the cause of death was from suicide (ICD-9 codes: E950-E959).35 Self-harm was ascertained through the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System database with an ICD-10 discharge code of X60-X84, Y10-Y19, or Y28.

Analysis

For each covariate level, the number of individuals, percentage of individuals, and rates of each outcome were assessed separately for recent immigrants and long-term residents. We described the method of suicide and self-harm stratified by sex for recent immigrants and long-term residents. Unadjusted and adjusted survival curves were constructed for each class of immigrants. Multivariable adjusted survival curves were constructed using the corrected group prognosis method and included adjustment for age, sex, neighborhood-level income, and rurality.36

To examine country-specific patterns of self-harm and suicide, funnel plots were constructed plotting the rate of the outcome versus the person-years of follow-up for all countries. Separate funnel plots with 95% and 99% confidence intervals (CIs) were constructed with (1) the overall recent immigrant rate and (2) the long-term resident rate as comparison groups.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to examine the time to first event. Self-harm and suicide were analyzed by separate models. We examined the association between recent immigrant status (vs. long-term resident) and each outcome adjusting for age, sex, neighborhood-level income, and rurality. We then examined the multivariable-adjusted association between each covariate and each outcome for recent immigrants and long-term residents separately. Among immigrants only, we examined the association between immigrant class and each outcome controlling for age, sex, neighborhood-level income, and rurality. Income was modeled as a time-varying covariate in all analyses. Analyses were conducted in SAS Enterprise Guide Version 6.1.

ICES is a prescribed entity under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act. Section 45 authorizes ICES to collect personal health information, without consent, for the purpose of analysis or compiling statistical information with respect to the management of, evaluation or monitoring of, the allocation of resources to, or planning for all or part of the health system. Projects conducted under section 45, by definition, do not require review by a research ethics board. This project was conducted under section 45 and approved by ICES’ Privacy and Compliance Office. Cell sizes <6 were suppressed to ensure nonidentification and meet institutional policy which resulted in collapsing of some categories and not presenting rates of self-harm or suicide for select countries.

Results

There were 590,289 recent immigrants and 8,464,790 long-term residents included (Supplemental Figure 1). Among immigrants, 58,082 (9.8%) were refugees, 289,108 (49.0%) were family class immigrants, and 243,099 (41.1%) were business or economic class immigrants. Demographic characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table 1. Notably, immigrants had larger proportions in the younger age categories, in lower neighborhood-level income quintiles, and in urban areas. The largest proportion of immigrants was from South Asia (31.8%) followed by East Asia (25.9%). Upon landing in Canada, the majority (73.0%) of immigrants were married and 43.4% had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Cohort.

| Socio-demographic variable | Immigrants (N = 590,289) | Long-term residents (N = 8,464,790) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Immigration status (visa class) | ||||

| Business | 6,728 | 1.1 | — | — |

| Economic | 236,371 | 40.0 | — | — |

| Refugee | 58,082 | 9.8 | — | — |

| Family | 289,108 | 49.0 | — | — |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 317,055 | 53.7 | 4,325,659 | 51.1 |

| Men | 273,234 | 46.3 | 4,139,131 | 48.9 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18 to 29 | 211,689 | 35.9 | 1,637,024 | 19.3 |

| 30 to 49 | 279,954 | 47.4 | 3,067,583 | 36.2 |

| 50 to 64 | 64,377 | 10.9 | 2,130,627 | 25.2 |

| 65+ | 34,269 | 5.8 | 1,629,556 | 19.3 |

| Neighborhood-level income quintile | ||||

| Quintile 1 (lowest) | 208,847 | 35.4 | 1,491,988 | 17.6 |

| Quintile 2 | 138,190 | 23.4 | 1,641,662 | 19.4 |

| Quintile 3 | 105,378 | 17.9 | 1,677,272 | 19.8 |

| Quintile 4 | 79,249 | 13.4 | 1,769,245 | 20.9 |

| Quintile 5 (highest) | 51,684 | 8.8 | 1,822,954 | 21.5 |

| Missing | 6,941 | 1.2 | 61,669 | 0.7 |

| Rurality | ||||

| Urban | 567,847 | 96.2 | 5,664,691 | 66.9 |

| Rural | 16,720 | 2.8 | 2,683,296 | 31.7 |

| Missing | 5,722 | 1.0 | 116,803 | 1.4 |

| Region of birth | ||||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 33,048 | 5.6 | — | — |

| East Asia and Pacific | 153,072 | 25.9 | — | — |

| Europe and Central Asia | 76,139 | 12.9 | — | — |

| Central and South America | 35,073 | 5.9 | — | — |

| Caribbean and Bermuda | 25,344 | 4.3 | — | — |

| Middle East and North Africa | 69,679 | 11.8 | — | — |

| South Asia | 187,436 | 31.8 | — | — |

| North America | 10,473 | 1.8 | — | — |

| Missing | 25 | 0.0 | — | — |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 430,687 | 73.0 | — | — |

| Single | 82,785 | 14.0 | — | — |

| Separated/widowed/divorced | 26,238 | 4.4 | — | — |

| Missing/<22 years at indexa | 50,579 | 8.6 | — | — |

| Education | ||||

| Secondary or less | 183,190 | 31.0 | — | — |

| Anything less than bachelors | 100,571 | 17.0 | — | — |

| Bachelors or higher | 255,999 | 43.4 | — | — |

| Missing/<22 years at indexa | 50,529 | 8.6 | — | — |

aImmigrants age <22 years at index assigned to missing.

Suicide

There were 130 suicides among recent immigrants (crude rate: 3.3/100,000 person-years) and 6,354 suicides among long-term residents (crude rate: 11.8/100,000 person-years). Suicide rates among immigrant men were 4.4/100,000 person-years versus 18.2/100,000 among long-term resident men. Suicide rates among immigrant women were 2.5/100,000 person-years versus 5.7/100,000 among long-term resident women (Table 2). In the adjusted models, immigrants had lower rates of suicide compared with long-term residents (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]: 0.27; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.32; Table 3). While risk of suicide was associated with being male, there was a stronger association between being male and suicide among long-term residents than immigrants (long-term resident men vs. women aHR: 3.19; 95% CI, 3.01 to 3.38); immigrant men vs. women (aHR: 1.84; 95% CI, 1.29 to 2.62). Middle age and low neighborhood-level income quintile were associated with suicide risk among long-term residents but not among immigrants. Within immigrants, refugees had 2.1 times the likelihood (95% CI, 1.3 to 3.6) of suicide compared with economic class immigrants.

Table 2.

Number and Rates of Suicide and Self-Harm among Immigrants and Long-Term Residents by Sociodemographic Characteristics.

| Socio-demographic variable | Suicide | Self-Harm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immigrants (N =130) | Long-term residents (N = 6,354) | Immigrants (N =2,256) | Long-term residents (N = 68,039) | |||||

| N | Rate/100K (CI) | N | Rate/100K (CI) | N | Rate/10K (CI) | N | Rate/10K (CI) | |

| Immigration status (visa class) | NA | |||||||

| Business | Combined with other economic | — | — | 34 | 5.22 (3.61 to 7.29) | — | — | |

| Economic | 46 | 2.77 (2.03 to 3.70) | — | — | 540 | 2.60 (2.38 to 2.83) | — | — |

| Refugee | 23 | 6.12 (3.88 to 9.18) | — | — | 396 | 8.09 (7.31 to 8.93) | — | — |

| Family | 61 | 3.26 (2.50 to 4.19) | — | — | 1,286 | 5.26 (4.98 to 5.56) | — | — |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Women | 52 | 2.46 (1.83 to 3.22) | 1,581 | 5.73 (5.45 to 6.02) | 1,429 | 5.20 (4.93 to 5.48) | 35 405 | 9.86 (9.76 to 9.96) |

| Men | 78 | 4.36 (3.45 to 5.45) | 4,773 | 18.21 (17.69 to 18.73) | 827 | 3.55 (3.32 to 3.80) | 32 634 | 9.58 (9.48 to 9.69) |

| Age (y) | ||||||||

| 18 to 29 | 50 | 3.54 (2.63 to 4.67) | 1,034 | 9.76 (9.17 to 10.37) | 1,346 | 7.35 (6.96 to 7.76) | 22 497 | 16.28 (16.07 to 16.49) |

| 30 to 49 | 54 | 2.88 (2.16 to 3.76) | 2,855 | 13.84 (13.34 to 14.36) | 752 | 3.09 (2.87 to 3.32) | 30 334 | 11.30 (11.17 to 11.43) |

| 50 to 64 | 17 | 4.11 (2.40 to 6.59) | 1,598 | 11.76 (11.19 to 12.35) | 108 | 1.99 (1.63 to 2.40) | 11 192 | 6.26 (6.15 to 6.38) |

| 65+ | 9 | 4.44 (2.03 to 8.43) | 867 | 9.61 (8.98 to 10.27) | 50 | 1.87 (1.39 to 2.46) | 4,016 | 3.52 (3.41 to 3.63) |

| Neighborhood-level income quintile | ||||||||

| Quintile 1 (lowest) | 59b | 3.97 (3.00 to 5.16) | 1,523 | 16.17 (15.37 to 17.00) | 793 | 4.35 (4.05 to 4.66) | 19 239 | 15.86 (15.64 to 16.09) |

| Quintile 2 | 24 | 2.58 (1.66 to 3.84) | 1,354 | 12.93 (12.25 to 13.64) | 578 | 4.79 (4.41 to 5.20) | 14 517 | 10.70 (10.53 to 10.87) |

| Quintile 3 | 14 | 2.02 (1.10 to 3.39) | 1,235 | 11.52 (10.88 to 12.18) | 412 | 4.56 (4.13 to 5.02) | 12 321 | 8.83 (8.67 to 8.99) |

| Quintile 4 | 21 | 4.10 (2.54 to 6.27) | 1,096 | 9.72 (9.15 to 10.31) | 297 | 4.43 (3.94 to 4.97) | 11 281 | 7.66 (7.52 to 7.80) |

| Quintile 5 (highest) | 12 | 3.61 (1.87 to 6.31) | 1,084 | 9.32 (8.77 to 9.89) | 163 | 3.75 (3.20 to 4.37) | 10 054 | 6.62 (6.49 to 6.75) |

| Missing | Combined missingb | 62 | 20.67 (15.85 to 26.50) | 13 | 3.54 (1.88 to 6.05) | 627 | 16.24 (15.00 to 17.57) | |

| Rurality | ||||||||

| Urban | 123 | 3.26 (2.71 to 3.89) | 4,052 | 11.22 (10.88 to 11.57) | 2,155 | 4.39 (4.21 to 4.58) | 44 706 | 9.53 (9.44 to 9.62) |

| Rural | 7b | 5.50 (2.21 to 11.33)b | 2,158 | 12.65 (12.12 to 13.19) | 92 | 6.69 (5.39 to 8.20) | 21 556 | 9.72 (9.59 to 9.85) |

| Missing | Combined missingb | 144 | 21.81 (18.40 to 25.68) | 9 | 3.24 (1.48 to 6.15) | 1,777 | 20.95 (19.99 to 21.95) | |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 83 | 2.92 (2.33 to 3.62) | — | — | 1,405 | 3.80 (3.60 to 4.00) | — | — |

| Single | 24 | 4.40 (2.82 to 6.54) | — | — | 297 | 4.19 (3.73 to 4.70) | — | — |

| Separated/widowed/divorced | 6 | 3.51 (1.29 to 7.63) | — | — | 69 | 3.11 (2.42 to 3.94) | — | — |

| Missing/<22 years at indexa | 17 | 4.91 (2.86 to 7.86) | — | — | 485 | 10.85 (9.91 to 11.86) | — | — |

| Education | ||||||||

| Secondary or less | 45 | 3.88 (2.83 to 5.19) | — | — | 755 | 4.94 (4.60 to 5.31) | — | — |

| Anything less than bachelors | 30 | 4.42 (2.98 to 6.31) | — | — | 406 | 4.62 (4.18 to 5.10) | — | — |

| Bachelors or higher | 38 | 2.21 (1.56 to 3.03) | — | — | 611 | 2.75 (2.53 to 2.97) | ||

| Missing/<22 years at indexa | 17 | 4.91 (2.86 to 7.87) | — | — | 484 | 10.84 (9.90 to 11.85) | — | — |

aImmigrants age <22 years at index assigned to missing.

bCombined with missing to prevent back-calculation of small cell sizes as per institutional policy.

Table 3.

Cox Proportional Hazards Regression of Suicide and Self-Harm Among All Cohort and Stratified by Immigrant Status.

| Socio-demographic variable | Suicide | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Cohort | Long-term residents | Immigrants | ||

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) | |

| Immigrant (Ref: Long-term resident) | 0.28 (0.24 to 0.34) | 0.27 (0.23 to 0.32) | — | — |

| Immigration status (visa class) (Ref: Economic) | ||||

| Refugee | — | — | 2.13 (1.26 to 3.63) | |

| Family | — | — | 1.11 (0.71 to 1.73) | |

| Sex (Ref: Women) | ||||

| Men | 3.14 (2.97 to 3.33) | 3.19 (3.01 to 3.38) | 1.84 (1.28 to 2.63) | |

| Age (years) (Ref: 18 to 29) | ||||

| 30 to 49 | 1.49 (1.39 to 1.60) | 1.53 (1.42 to 1.65) | 0.81 (0.54 to 1.21) | |

| 50 to 64 | 1.30 (1.20 to 1.40) | 1.31 (1.21 to 1.42) | 1.17 (0.67 to 2.03) | |

| 65+ | 1.10 (1.01 to 1.21) | 1.12 (1.02 to 1.22) | 1.10 (0.51 to 2.38) | |

| Neighborhood-level income quintile (Ref: Quintile 1) | ||||

| Quintile 2 | 0.76 (0.70 to 0.82) | 0.76 (0.70 to 0.82) | 0.71 (0.43 to 1.16) | |

| Quintile 3 | 0.68 (0.63 to 0.73) | 0.68 (0.63 to 0.73) | 0.40 (0.21 to 0.78) | |

| Quintile 4 | 0.53 (0.49 to 0.58) | 0.53 (0.49 to 0.57) | 1.10 (0.67 to 1.81) | |

| Quintile 5 | 0.54 (0.50 to 0.58) | 0.53 (0.49 to 0.57) | 1.40 (0.80 to 2.47) | |

| Rurality (Ref: urban) | ||||

| Rural | 1.12 (1.07 to 1.18) | 1.12 (1.06 to 1.18) | 1.43 (0.57 to 3.61) | |

| Self-Harm | ||||

| Immigrant (Ref: Long-term resident) | 0.46 (0.44 to 0.48) | 0.33 (0.31 to 0.34) | — | — |

| Immigration status (visa class) (Ref: Economic) | ||||

| Business | — | — | 2.00 (1.41 to 2.85) | |

| Refugee | — | — | 2.82 (2.47 to 3.22) | |

| Family | — | — | 1.83 (1.64 to 2.05) | |

| Sex (Ref: Women) | ||||

| Male | 0.93 (0.92 to 0.94) | 0.94 (0.92 to 0.95) | 0.76 (0.69 to 0.83) | |

| Age (years) (Ref: 18 to 29) | ||||

| 30 to 49 | 0.71 (0.70 to 0.72) | 0.73 (0.71 to 0.74) | 0.51 (0.47 to 0.56) | |

| 50 to 64 | 0.40 (0.39 to 0.41) | 0.41 (0.40 to 0.42) | 0.26 (0.21 to 0.31) | |

| 65+ | 0.22 (0.21 to 0.23) | 0.22 (0.21 to 0.23) | 0.24 (0.18 to 0.31) | |

| Neighborhood-level income quintile (Ref: Quintile 1) | ||||

| Quintile 2 | 0.68 (0.66 to 0.69) | 0.67 (0.65 to 0.68) | 0.99 (0.89 to 1.10) | |

| Quintile 3 | 0.54 (0.53 to 0.56) | 0.53 (0.52 to 0.54) | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.08) | |

| Quintile 4 | 0.46 (0.45 to 0.47) | 0.45 (0.44 to 0.46) | 0.87 (0.76 to 0.99) | |

| Quintile 5 | 0.41 (0.40 to 0.42) | 0.40 (0.39 to 0.41) | 0.80 (0.68 to 0.94) | |

| Rurality (Ref: urban) | ||||

| Rural | 1.06 (1.04 to 1.07) | 1.05 (1.04 to 1.07) | 1.57 (1.27 to 1.93) | |

aAdjusted for age, sex, neighborhood-level income, rurality, and immigrant models adjusted for visa class, age, sex, neighborhood-level income, and rurality.

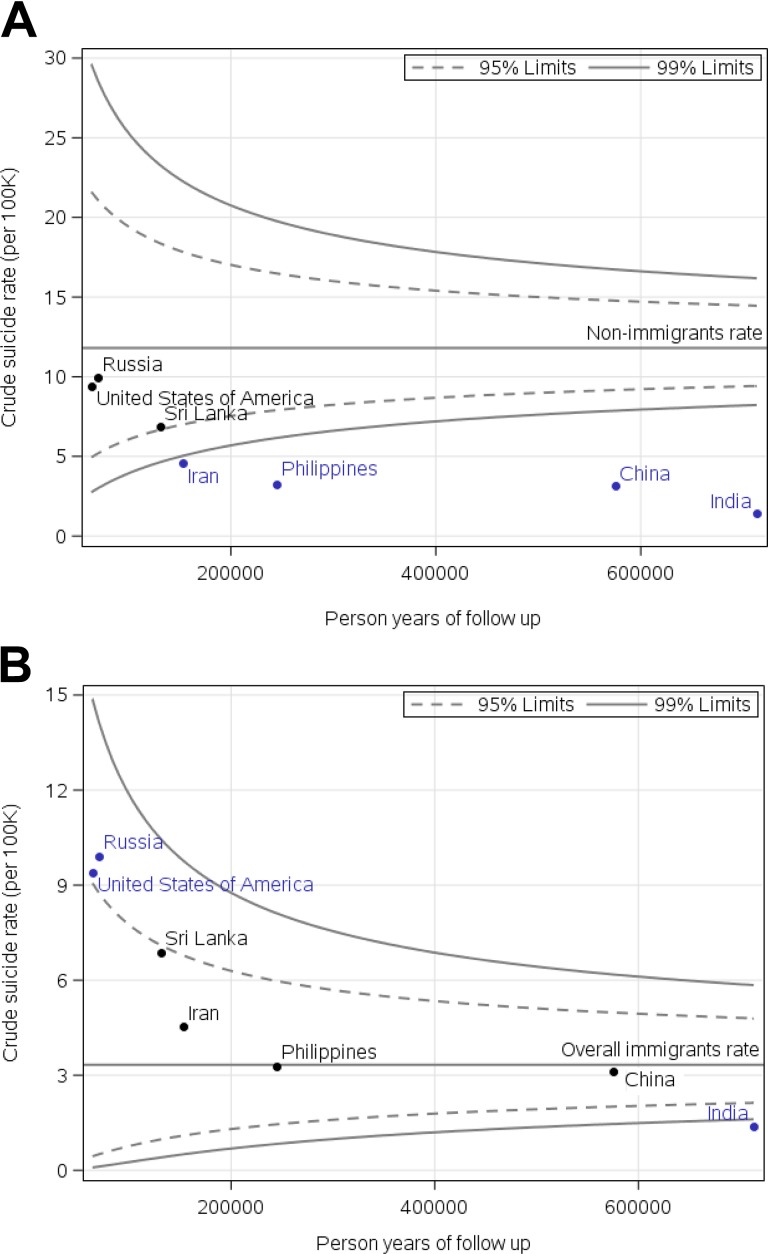

Figure 1A shows a funnel plot of the crude suicide rates in immigrants by country of origin for countries with at least six events referenced against the long-term resident population. Suicide rates in immigrants from every country were lower than the long-term resident rate. Figure 1B shows a similar funnel plot instead referenced to the rate of the immigrant population. Immigrants from Russia and the United States had suicide rates significantly higher than the general immigrant population, and immigrants from India had rates lower than the general immigrant population.

Figure 1.

Funnel plots of crude rates for suicide by country referenced to overall nonimmigrant rate (A) and overall immigrant rate (B).

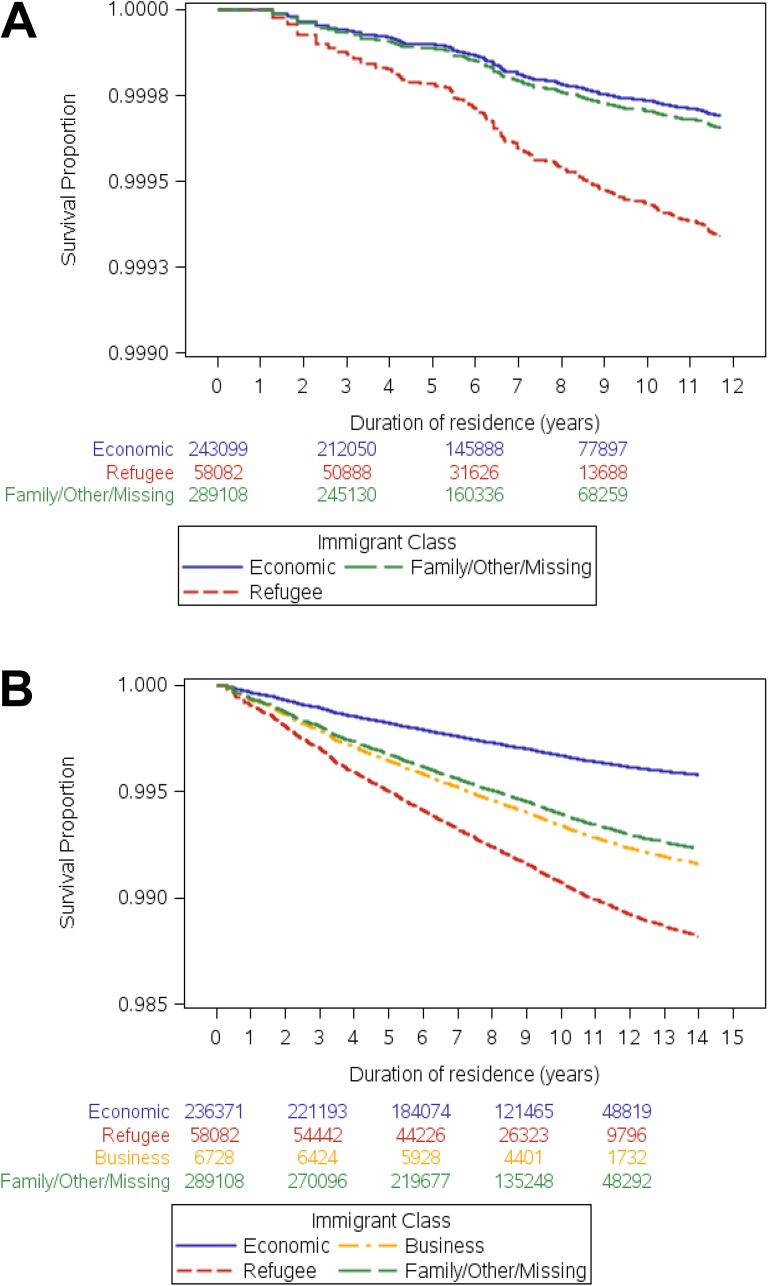

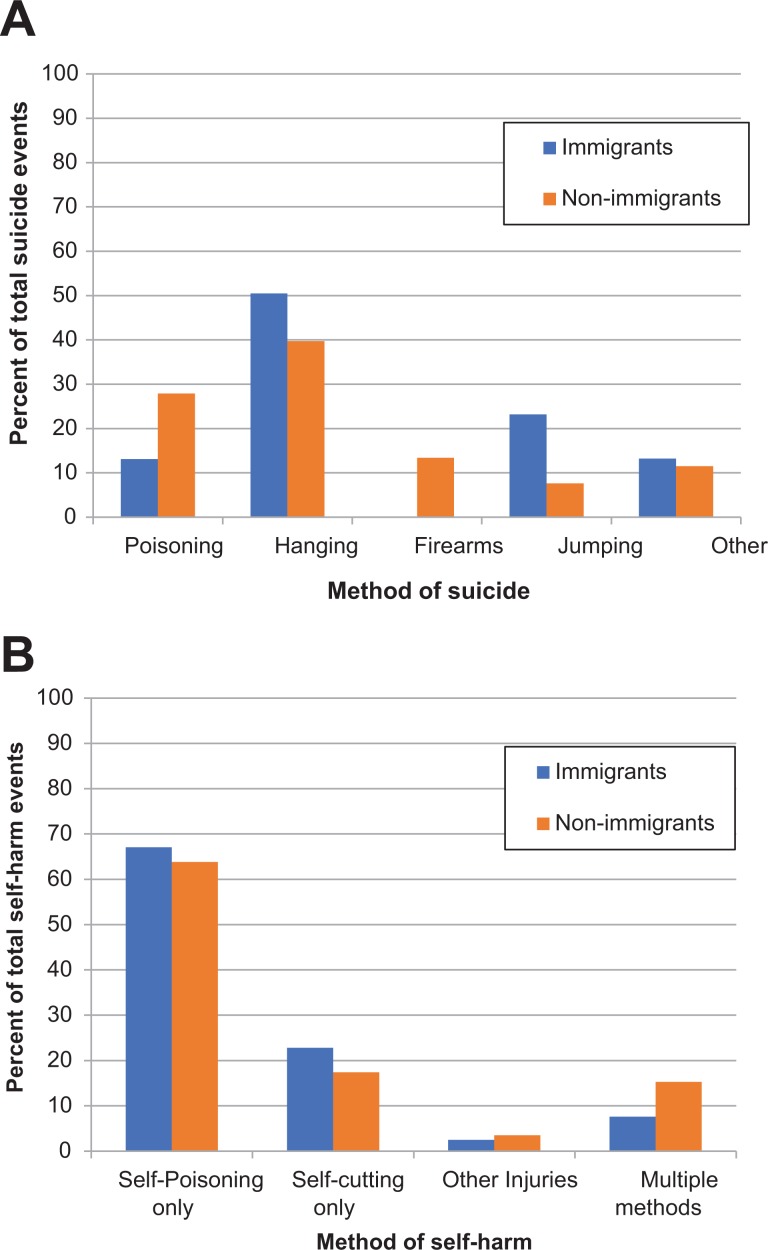

Figure 2A shows the adjusted survival curve for suicide among immigrants. The pattern of the time to suicide was linear and similar between immigrant groups. Suicide events did not start until at least 1 year after arrival. Among immigrants, hanging was responsible for 50.5% of suicides versus 39.7% of suicides in long-term residents. Suicide by firearms occurred in 13.4% (603) of cases among long-term residents but was rare among immigrants (<6 events; Figure 3A).

Figure 2.

Adjusted survival curves for suicide (A) and self-harm (B) stratified by class of immigrants.a,b Numbers represent persons at-risk of event for each corresponding time period.

aAdjusted for age, sex, neighborhood-level income quintile, and rurality; bToo few events to plot Business class for (A), suicide.

Figure 3.

Method of suicide (A) and self-harm (B) by immigrant status. Only suicides occurring prior to fiscal year 2013 were classified into methods since this was no longer recorded in the available databases afterward. Suicide by firearms is suppressed and added to other for immigrants since N < 6.

Self-Harm

Immigrants had 2,256 self-harm events (crude rate: 4.4/10,000 person-years), and long-term residents had 68,039 self-harm events (crude rate: 9.7/10,000 person-years). The self-harm rate among immigrant men was 3.6/10,000 person-years versus 9.6/10,000 person-years in long-term resident men. The self-harm rate among immigrant women was 5.2/10,000 person-years versus 9.9/10,000 person-years (Table 2). In adjusted models, immigrants had lower rates of self-harm compared with long-term residents (aHR: 0.32; 95% CI, 0.31 to 0.34; Table 3). Self-harm was associated with being female in both immigrants and long-term residents with a stronger association among immigrant females. Young age (18 to 29 years) was associated with risk of self-harm in both immigrants and long-term residents. While neighborhood-level income quintile was inversely associated with self-harm risk among long-term residents, the strength of this relationship was attenuated among immigrants (long-term residents Q5 Incidence rate ratio [IRR]: 0.40; 95% CI, 0.39 to 0.41; immigrants Q5 IRR: 0.80; 95% CI, 0.68 to 0.94). Among immigrants, refugees had the highest risk of self-harm (aHR: 2.82; 95% CI, 2.47 to 3.22). The adjusted survival curve for self-harm among immigrants is shown in Figure 2B. The time to first self-harm event was linear across all immigrant classes.

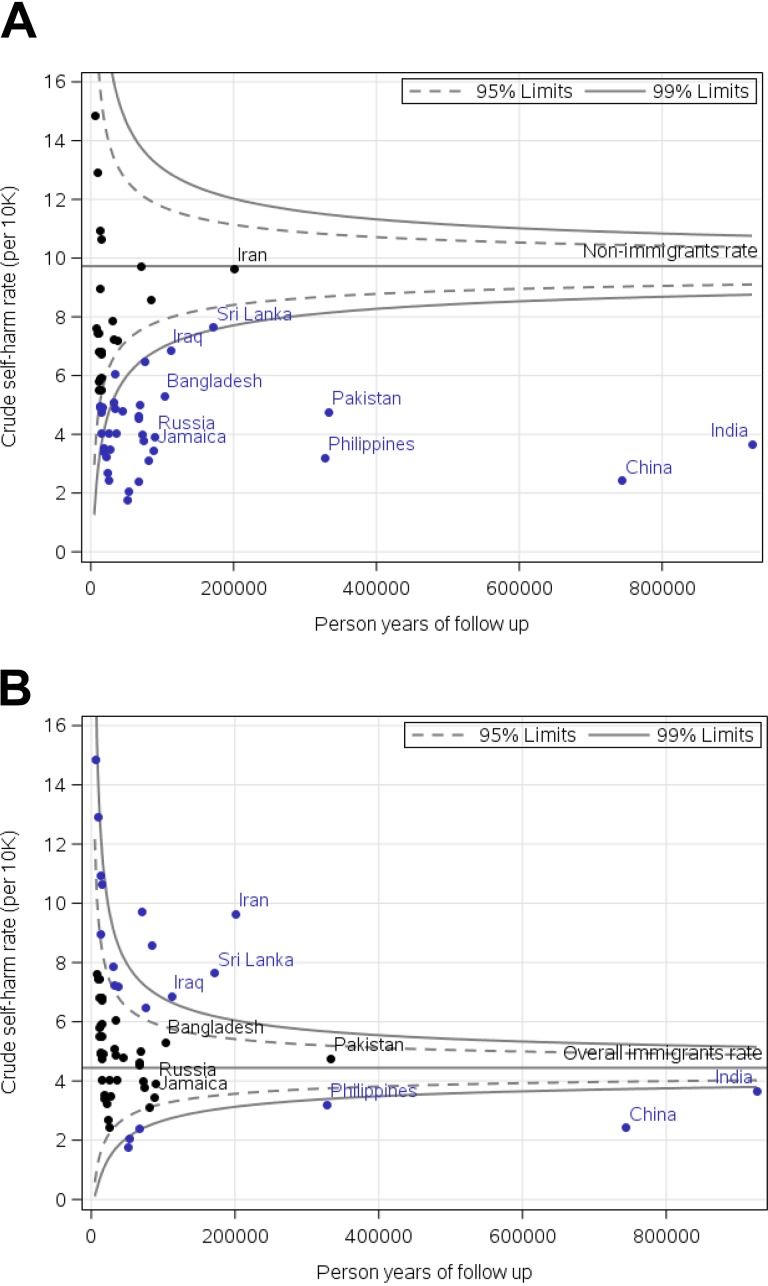

Figure 4A shows a funnel plot for the crude rates of self-harm by country. There was no country of origin for which immigrants had higher rates of self-harm compared with long-term residents (long-term resident self-harm rate 9.7/10,000 person-years, 95% CI, 9.65 to 9.80). Compared with the overall immigrant rate, rates of self-harm were higher in immigrants from Iran, Sri Lanka, Iraq, the United States, the United Kingdom, Afghanistan, Turkey, and Dominican Republic and lower in immigrants from India, China, Nigeria, and Lebanon (Figure 4B). Most immigrants (67.1%) and long-term residents (63.8%) presented to the emergency room for self-harm with self-poisoning (Figure 3B). A smaller proportion of immigrants who presented with self-harm later died by suicide compared with long-term residents (0.58% vs. 1.38%) and a smaller proportion of immigrants were admitted to hospital from their ED visit for self-harm compared with long-term residents (40.3% vs. 47.7%; Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Rates of suicide and self-harm using direct standardization are shown in Supplemental Table 3.

Figure 4.

Funnel plots of crude rates for self-harm by country referenced to overall nonimmigrant rate (A) and overall immigrant rate (B).

Interpretation

We showed that suicide and self-harm rates in adult recent immigrants to Canada are substantially lower than rates in long-term residents. Refugees are at higher risk than nonrefugee immigrants for suicide and self-harm, and there is a considerable variability in both suicide and self-harm rates by country of origin. Importantly, we report predictors of suicide and self-harm in recent immigrants are different than in long-term residents; the suicide and self-harm risk factors—higher risk in men, the middle-aged and elderly, and those with lower socioeconomic status—are not observed or observed in an attenuated fashion among immigrants. The country-specific variability in our outcomes suggests that suicide and self-harm interventions to reduce these poor outcomes should consider one’s country of origin.

Existing population-based registry studies on immigrant suicide and self-harm compared with native-born populations have had variable results which largely depend on the region or class of immigrants entering a given country or their sex and age.10,37,38 First-generation male immigrants to Norway have lower rates of suicide than native Norwegians, but there are no differences in rates of suicide between female immigrants and female native Norwegians.39,40 Immigrants to Sweden have lower rates of completed suicide13 but similar rates of suicide attempts compared with nonimmigrants.41 Australian immigrants also have lower suicide rates than native-born but immigrants bring their native country risk of suicide with them.20 Male asylum seekers in the Netherlands have higher rates of suicide compared with native Dutch, and both male and female asylum seekers have higher rates of hospital-related suicide behavior than native-born.42 Foreign-born in Brazil also have higher rates of suicide compared with native Brazilians.43 Taken together, these studies suggest recognizing contextual factors in the receiving country (e.g., proportion of population of immigrants, health system accessibility and structure, local stigma, immigration and settlement policies, local settlement support services) and immigration characteristics (e.g., refugee status, time since immigration, native country suicide rate) is important for understanding the heterogeneity in the literature and for understanding suicide risk among immigrants more broadly.

Canada’s immigration selection and settlement policies, which target healthy and highly educated individuals, with high labor force participation44 may confer protection from suicide among immigrants. Certain sociocultural factors in foreign-born individuals including reduced risk-taking behaviors,45–47 familial and social support systems that promote healthy living and a sense of well-being,48,49 and high concentrations of immigrants in urban neighborhoods where Canadian migrants settle50,51 may explain the lower relative suicide and self-harm rates observed among immigrants in our study.

Similar to the current findings, a recent Norwegian registry-based study showed that the strength of the association between sex and suicide rates among immigrants was attenuated owing to the relatively low rates of suicide among male immigrants.39,52 However, ours is the first to show no association between suicide and age and neighborhood-level income. Khan et al.53 have shown that the effect of neighborhood-level income on premature mortality is attenuated among immigrants. They attributed this to the healthy immigrant effect and higher relative educational attainment in immigrant populations living in poorer neighborhoods. This blunted income effect and the protective effects of urban living may be related to high concentrations of immigrants in neighborhoods where immigrants settle allowing for increased social and settlement supports. It is also important to note the strong age and sex effects for self-harm predominantly for 18- to 29-year-old immigrants. These self-harm events in young people, which comprise 60% of all events, may reflect greater familial acculturative stress as these immigrants emerge from adolescence.1 Familial acculturative stress can influence psychiatric outcomes including depression and suicidal ideation, specifically among immigrants.54

Globally, there is a wide variation in in-country rates of suicide. Sri Lanka, Lithuania, and Guyana have some of the highest suicide rates (29 to 35/100,000 population), whereas several Caribbean and Middle Eastern countries have the lowest suicide rates (<3/100,000 population).24 There is some evidence to suggest that immigrants bring their home country risk of suicide with them following migration, but this has not been studied in immigrants to Canada for at least three decades.1,55–57 While only being an immigrant from Russia and the United States conferred a higher risk of suicide compared with the overall immigrant rate, we reported high rates of self-harm in immigrants from countries with relatively low in-country suicide rates, including Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Afghanistan. This suggests immigrants to Canada may not all retain their home-country risk of self-harm and suicide and the relatively high proportion of refugees from these countries may counter the low in-country suicide rates.

Hanging was the most frequently used method for suicide in both immigrant and long-term resident populations. Suicide by firearm by immigrants to Canada is almost nonexistent, suggesting this may be a native-born phenomenon, where easier access to firearms may contribute to suicide fatalities.

Strengths and Limitations

Some limitations to this study warrant consideration. We were limited by data availability to understand the suicide and self-harm behavior context. For example, we did not have data on a history of prior mental illness or self-harm in the country of origin prior to migration. We did not have data on social and family support networks and language proficiency which could shed light on protective factors. Immigration status for migrants prior to 1985 could not be identified in available databases, and therefore, we could only examine long-term residents living for greater than 18 years in Canada rather than nonimmigrants. Linkage of immigration data was not as good in immigrants from East Asian populations due to commonness of surnames and therefore may underestimate the true prevalence of suicide in this population.31 Self-harm not leading to an ED visit was not captured in health records. Results may not be generalizable to temporary or undocumented immigrants and refugees seeking asylum without permanent residency status as these immigrants are not currently linkable with existing databases.

Strengths of this study include the use of population-level data sets with validated codes for suicide and self-harm with large sample sizes and almost complete provincial coverage.35,58 Detailed immigration information including visa class and country of origin with systematic and uniform data collection distinguishes this study from other small cohort studies relying on self-report59 or other population-based immigrant suicide studies that lack detailed immigration data.39 Results are generalizable to other countries (e.g., UK, Australia) with a similarly large and heterogeneous immigrant population.

Implications

Recent immigrants have lower rates of suicide and self-harm compared with Canadian-born individuals. Sociodemographic factors that conventionally predict suicide and self-harm do not apply universally to recent immigrants, suggesting potential mediating effects of immigration selection, education level, and early social and settlement supports. Understanding contributing protective factors for suicide and self-harm in immigrant populations is important. Given the heterogeneity in risk of suicide and self-harm by country of origin and ongoing global migration, monitoring suicide and self-harm rates as new risk groups emerge with analyses of contextual factors is imperative.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, 856851_Supplemental_Figure for Suicide and Self-Harm in Recent Immigrants in Ontario, Canada: A Population-Based Study by Natasha Ruth Saunders, Maria Chiu, Michael Lebenbaum, Simon Chen, Paul Kurdyak, Astrid Guttmann and Simone Vigod in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, 856851_Supplemental_Tables for Suicide and Self-Harm in Recent Immigrants in Ontario, Canada: A Population-Based Study by Natasha Ruth Saunders, Maria Chiu, Michael Lebenbaum, Simon Chen, Paul Kurdyak, Astrid Guttmann and Simone Vigod in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Natasha Ruth Saunders and Maria Chiu are co-principal authors.

Author Contributions: N. Saunders and M. Lebenbaum conceptualized and designed the study, interpreted the results, drafted the initial manuscript, revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. M. Chiu conceptualized and designed the study, interpreted the results, revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. S. Vigod, P. Kurdyak, and A. Guttmann interpreted the results, revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. S. Chen had access to and analyzed the data, interpreted the results, revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data Sharing: The data set from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. Data-sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the data set publicly available, but access may be granted to those who meet prespecified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS. The full data set creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Simone Vigod reports receiving authorship royalties from UpToDate Inc., outside the submitted work. No other competing interests were declared.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) and Immigration, Refugees Citizenship Canada (IRCC). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of CIHI or IRCC. Michael Lebenbaum is supported by a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship. Astrid Guttmann is supported by a Canadian Institute for Health Research Applied Chair in Reproductive and Child Health Services and Policy Research.

ORCID iD: Natasha Ruth Saunders, MD, MSc  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4369-6904

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4369-6904

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Forte A, Trobia F, Gualtieri F, et al. Suicide risk among immigrants and ethnic minorities: a literature overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):E1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Suicide fact sheet. World Health Organization; 2016 [Cited 2016 June 14] Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs398/en/.

- 3. Carr MJ, Ashcroft DM, Kontopantelis E, et al. The epidemiology of self-harm in a UK-wide primary care patient cohort, 2001-2013. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hawton K, Haw C, Casey D, et al. Self-harm in Oxford, England: epidemiological and clinical trends, 1996-2010. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(5):695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perera J, Wand T, Bein KJ, et al. Presentations to NSW emergency departments with self-harm, suicidal ideation, or intentional poisoning, 2010-2014. Med J Aust. 2018;208(8):348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Biddle L, Brock A, Brookes ST, et al. Suicide rates in young men in England and Wales in the 21st century: time trend study. BMJ. 2008;336(7643):539–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fedyszyn IE, Erlangsen A, Hjorthoj C, et al. Repeated suicide attempts and suicide among individuals with a first emergency department contact for attempted suicide: a prospective, nationwide, Danish register-based study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(6):832–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Skegg K. Self-harm. Lancet. 2005;366(9495):1471–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Windfuhr K, While D, Hunt IM, et al. Suicide and accidental deaths in children and adolescents in England and Wales, 2001-2010. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(12):945–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johansson LM, Sundquist J, Johansson SE, et al. Suicide among foreign-born minorities and Native Swedes: an epidemiological follow-up study of a defined population. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(2):181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saunders NR, Lebenbaum M, Stukel TA, et al. Suicide and self-harm trends in recent immigrant youth in Ontario, 1996-2012: a population-based longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e014863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bauwelinck M, Deboosere P, Willaert D, et al. Suicide mortality in Belgium at the beginning of the 21st century: differences according to migrant background. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(1):111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Di Thiene D, Alexanderson K, Tinghog P, et al. Suicide among first-generation and second-generation immigrants in Sweden: association with labour market marginalisation and morbidity. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(5):467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elamoshy R, Feng C. Suicidal ideation and healthy immigrant effect in the Canadian population: a cross-sectional population based study. Int J Environ Res public Health. 2018;15(5):E848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McDonald JT, Kennedy S. Insights into the ‘healthy immigrant effect’: health status and health service use of immigrants to Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(8):1613–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saunders NR, Gill PJ, Holder L, et al. Use of the emergency department as a first point of contact for mental health care by immigrant youth in Canada: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2018;190(40):E1183–E1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saunders NR, Lebenbaum M, Lu H, et al. Trends in mental health service utilisation in immigrant youth in Ontario, Canada, 1996-2012: a population-based longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(9):e022647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hansson EK, Tuck A, Lurie S, et al. Rates of mental illness and suicidality in immigrant, refugee, ethnocultural, and racialized groups in Canada: a review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(2):111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vigod SN, Bagadia AJ, Hussain-Shamsy N, et al. Postpartum mental health of immigrant mothers by region of origin, time since immigration, and refugee status: a population-based study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(3):439–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burvill PW. Migrant suicide rates in Australia and in country of birth. Psychol Med. 1998;28(1):201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ikram UZ, Mackenbach JP, Harding S, et al. All-cause and cause-specific mortality of different migrant populations in Europe. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(7):655–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saunders NR, Macpherson A, Guan J, et al. Unintentional injuries in children and youth from immigrant families in Ontario, Canada: a population-based cross-sectional study. CMAJ Open. 2017;5(1):E90–E96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ten leading causes of death, by sex and geography, 2009—Ontario. Statistics Canada; 2015. [Cited 2017 February 23] Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/84-215-x/2012001/tbl/t019-eng.htm.

- 24. Suicide rates. Data by country. World Health Organization; 2012 [Cited 2016 June 14] Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.MHSUICIDE?lang=en.

- 25. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Health Indicators 2011. Ottawa, Canada: CIHI; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rhodes AE, Bethell J, Carlisle C, et al. Time trends in suicide-related behaviours in girls and boys. Can J psychiatry. 2014;59(3):152–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bridge JA, Greenhouse JB, Weldon AH, et al. Suicide trends among youths aged 10 to 19 years in the United States, 1996-2005. JAMA. 2008;300(9):1025–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen W, Hall BJ, Ling L, et al. Pre-migration and post-migration factors associated with mental health in humanitarian migrants in Australia and the moderation effect of post-migration stressors: findings from the first wave data of the BNLA cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(3):218–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Immigration and ethnocultural diversity: Key results from the 2016 Census. Statistics Canada; 2018 [Cited 2018 July 25] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025b-eng.htm.

- 30. Colucci E, Too LS, Minas H. A suicide research agenda for people from immigrant and refugee backgrounds. Death Stud. 2017;41(8):502–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chiu M, Lebenbaum M, Lam K, et al. Describing the linkages of the immigration, refugees and citizenship Canada permanent resident data and vital statistics death registry to Ontario’s administrative health database. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kralj B. Measuring rurality—RIO2008_BASIC: Methodology and results: OMA Economics Department; Toronto, Canada; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Durbin A, Moineddin R, Lin E, et al. Examining the relationship between neighbourhood deprivation and mental health service use of immigrants in Ontario, Canada: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(3):e006690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ivert AK, Svensson R, Adler H, et al. Pathways to child and adolescent psychiatric clinics: a multilevel study of the significance of ethnicity and neighbourhood social characteristics on source of referral. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Mental Health. 2011;5(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gatov E, Kurdyak P, Sinyor M, et al. Comparison of vital statistics definitions of suicide against a coroner reference standard: a population-based linkage study. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(3):152–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ghali WA, Quan H, Brant R, et al. Comparison of 2 methods for calculating adjusted survival curves from proportional hazards models. JAMA. 2001;286(12):1494–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Patel K, Kouvonen A, Close C, et al. What do register-based studies tell us about migrant mental health? A scoping review. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Johansson LM, Sundquist J, Johansson SE, et al. The influence of ethnicity and social and demographic factors on Swedish suicide rates. A four year follow-up study. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997;32(3):165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Puzo Q, Mehlum L, Qin P. Rates and characteristics of suicide by immigration background in Norway. PloS One. 2018;13(9):e0205035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Puzo Q, Mehlum L, Qin P. Suicide among immigrant population in Norway: a national register-based study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(6):584–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vazsonyi AT, Mikuska J, Gassova Z. Revisiting the immigrant paradox: Suicidal ideations and suicide attempts among immigrant and non-immigrant adolescents. J Adolesc. 2017;59:67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Goosen S, Kunst AE, Stronks K, et al. Suicide death and hospital-treated suicidal behaviour in asylum seekers in the Netherlands: a national registry-based study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bando DH, Brunoni AR, Fernandes TG, et al. Suicide rates and trends in Sao Paulo, Brazil, according to gender, age and demographic aspects: a joinpoint regression analysis. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2012;34(3):286–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liebig T. Jobs for immigrants: labour market integration in Norway. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers. Paris, France: OECD Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xiang H, Yu S, Zhang X, et al. Behavioral risk factors and unintentional injuries among U.S. immigrant adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(11):889–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sordo L, Indave BI, Vallejo F, et al. Effect of country-of-origin contextual factors and length of stay on immigrants’ substance use in Spain. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(6):930–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chau K, Baumann M, Kabuth B, et al. School difficulties in immigrant adolescent students and roles of socioeconomic factors, unhealthy behaviours, and physical and mental health. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chadwick KA, Collins PA. Examining the relationship between social support availability, urban center size, and self-perceived mental health of recent immigrants to Canada: a mixed-methods analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:220–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Macdonnell JA, Dastjerdi M, Bokore N, et al. Becoming resilient: promoting the mental health and well-being of immigrant women in a Canadian context. Nurs Res Pract. 2012;2012:576586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Facts & Figures 2015: Immigration Overview—permanent residents—Annual IRCC updates. 2015. [Cited 2017 July 6] Available from: http://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/2fbb56bd-eae7-4582-af7d-a197d185fc93?_ga=2.177922405.1187136379.1499268237-455880055.1499268237.

- 51. Pan SW, Carpiano RM. Immigrant density, sense of community belonging, and suicidal ideation among racial minority and white immigrants in Canada. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(1):34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Puzo Q, Mehlum L, Qin P. Socio-economic status and risk for suicide by immigration background in Norway: a register-based national study. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;100:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Khan AM, Urquia M, Kornas K, et al. Socioeconomic gradients in all-cause, premature and avoidable mortality among immigrants and long-term residents using linked death records in Ontario, Canada. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(7):625–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lane R, Miranda R. The effects of familial acculturative stress and hopelessness on suicidal ideation by immigration status among college students. J Am Coll Health. 2018;66(2):76–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Voracek M, Loibl LM. Consistency of immigrant and country-of-birth suicide rates: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scand. 2008;118(4):259–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Westman J, Sundquist J, Johansson LM, et al. Country of birth and suicide: a follow-up study of a national cohort in Sweden. Arch Suicide Res. 2006;10(3):239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kliewer EV, Ward RH. Convergence of immigrant suicide rates to those in the destination country. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127(3):640–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bethell J, Rhodes AE. Identifying deliberate self-harm in emergency department data. Health Rep. 2009;20(2):35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Clarke DE, Colantonio A, Rhodes AE, et al. Pathways to suicidality across ethnic groups in Canadian adults: the possible role of social stress. Psychol Med. 2008;38(3):419–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, 856851_Supplemental_Figure for Suicide and Self-Harm in Recent Immigrants in Ontario, Canada: A Population-Based Study by Natasha Ruth Saunders, Maria Chiu, Michael Lebenbaum, Simon Chen, Paul Kurdyak, Astrid Guttmann and Simone Vigod in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental Material, 856851_Supplemental_Tables for Suicide and Self-Harm in Recent Immigrants in Ontario, Canada: A Population-Based Study by Natasha Ruth Saunders, Maria Chiu, Michael Lebenbaum, Simon Chen, Paul Kurdyak, Astrid Guttmann and Simone Vigod in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry