Abstract

Background

Oomycetes are pathogens of mammals, fish, insects and plants, and the potato late blight agent Phytophthora infestans and the oil palm and cocoa infecting pathogen Phytophthora palmivora cause economically impacting diseases on a wide range of crop plants. Increasing genomic and transcriptomic resources and recent advances in oomycete biology demand new strategies for genetic modification of oomycetes. Most oomycete transformation procedures rely on geneticin-based selection of transgenic strains.

Results

We established N-acetyltransferase AAC(3)-I as a gentamicin-based selectable marker for oomycete transformation without interference with existing geneticin resistance. Strains carrying gentamicin resistance are fully infectious in plants. We further demonstrate the usefulness of this new antibiotic selection to super-transform well-characterized, already fluorescently-labelled P. palmivora strains and provide a comprehensive protocol for maintenance and zoospore electro-transformation of Phytophthora strains to aid in plant-pathogen research.

Conclusions

N-acetyltransferase AAC(3)-I is functional in Phytophthora oomycetes. In addition, the substrate specificity of the AAC(3)-I enzyme allows for re-transformation of geneticin-resistant strains. Our findings and resources widen the possibilities to study oomycete cell biology and plant-oomycete interactions.

Keywords: Oomycete, Counter-selection, Aminoglycoside, N-acetyltransferase, Specificity

Background

Oomycetes are filamentous microbes that grow as saprotrophs or as pathogens of a wide range of hosts from various lineages such as insects, fish, mammals including humans, and plants [1, 2]. Diseases caused by members of the plant-pathogenic oomycete genus Phytophthora have a strong economic footprint and therefore have received extensive attention over the past decades. For instance, late blight of tomato and potato due to infection with Phytophthora infestans, a member of clade 1 [3, 4], is responsible for billion-dollar losses yearly [5]. Similarly, the broad-host-range tropical species Phytophthora palmivora from clade 4 [3, 4] triggers disease on economically relevant crops including cocoa, mango, papaya, rubber tree, oil palm and many Citrus species [6, 7]. In addition, some Phytophthora are detrimental to natural ecosystems. For example, Phytophthora ramorum is threatening tanoak and other oak species in California and Oregon [8], and Phytophthora cinnamomi causes disease on multiple trees across the world, such as chestnut, oak, Eucalyptus and Banksia [9]. Most of these species are spreading beyond their original geographic area due to international trade and climate change [2, 10].

Phytophthora infection relies on the production of flagellate zoospores that reach host tissues by chemo- and electrotaxis [11]. Adhering zoospores encyst and germinate. Then, the germ tube rapidly differentiates into an appressorium-like structure to enable host penetration [12]. Following is a biotrophic stage characterized by oomycete hyphae growing extracellularly with no damage to host cells, and differentiating digit-like structures termed haustoria to deliver effectors [11, 13]. Biotrophy is then followed by a more detrimental stage, termed necrotrophy, causing death to host tissues. The oomycete completes its lifecycle by differentiating sporangia which produce new zoospores, further spreading the infection [14, 15].

Genomic [16–18], transcriptomic [15, 19], proteomic and metabolomic [20, 21] resources have been obtained to help deciphering the molecular basis of oomycete virulence. Genetic manipulation of oomycetes has gained increasing interest with the study of their molecular weaponry and the modalities of host tissue colonization [22–26]. At least four methods have been successfully applied to transform oomycetes: liposome-mediated protoplast transformation [27], microprojectile bombardment [28], Agrobacterium-mediated transformation [29, 30] and electroporation [31]. By contrast, only a handful of vectors are commonly used for delivery and genomic integration of transgenes in oomycetes. Most of them carry the Bremia lactucae Ham34 constitutive promoter [32] and native promoters are rarely used [25, 33]. The selection of oomycete transformants relies on the aminoglycoside antibiotics geneticin (G418) or hygromycin B [27].

Aminoglycosides antibiotics are synthesized by bacteria from the genera Streptomyces and Micromonospora [34]. They bind to the prokaryotic ribosomal decoding site, thereby reducing the fidelity of protein synthesis and ultimately killing susceptible bacteria [35]. The isolation of aminoglycoside-inactivating enzymes has widened their usage in basic research to assist with bacterial transformation. In addition, some antibiotic/enzyme combinations have been successfully used for the selection of transfected eukaryotic cells [36, 37]. Enzymatic inactivation of aminoglycosides can be achieved through acetylation, adenylylation, and phosphorylation [38] and several enzyme classes exist for each of these modifications. For instance, four classes of N-acetyltransferases inactivate aminoglycosides by acetylation of the 1-, 3-, 2′- and 6′-amino groups, respectively, conferring partially overlapping aminoglycoside resistance profiles [38].

Here we demonstrate that the aminoglycoside gentamicin arrests P. palmivora and P. infestans growth in vitro. The N-acetyltransferase AAC(3)-I confers gentamicin resistance, but retains geneticin (G418) susceptibility in P. palmivora. We generated Gateway compatible pTOR vectors for gentamicin-based selection to super-transform G418-resistant P. palmivora. This enabled fluorescent labelling of multiple cellular compartments and structures. Our findings and materials extend antibiotic selection as well as genetic manipulation possibilities for oomycetes.

Results

Gentamicin inhibits P. palmivora and P. infestans growth in vitro

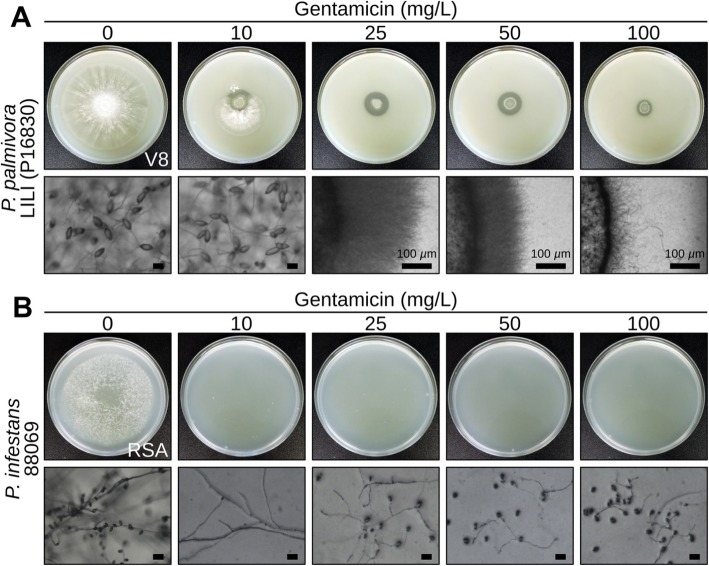

To expand the possibilities for antibiotic selection after transformation we surveyed P. infestans and P. palmivora for their susceptibility to carbenicillin, chloramphenicol, cefotaxime, gentamicin, rifampicin, spectinomycin and tetracycline. While most antibiotics were not effective in limiting mycelial growth (Additional file 1: Figure S1), P. palmivora and P. infestans were both susceptible to gentamicin (Fig. 1). A concentration of 10 mg/L gentamicin (Fig. 1a) limited P. infestans hyphal growth and inhibited sporangia formation. By contrast, some P. palmivora colonies were still able to grow and produce sporangia at this concentration (Fig. 1b). At 100 mg/L gentamicin, development of both oomycete species was fully arrested at the germinating cyst stage (Fig. 1a-b). Thus, gentamicin-100 is a robust and reproducible inhibitor of mycelial growth on V8 and RSA agar growth media.

Fig. 1.

Gentamicin impairs growth of wild-type and G418-resistant Phytophthora palmivora and Phytophthora infestans strains in vitro. a-b) Representative pictures of 5-day-old P. palmivora LILI (accession P16830) grown on V8 (a) or 10-day-old P. infestans isolate 88,069 grown on RSA (b). Plates were supplemented with 0, 10, 25, 50 or 100 mg/L gentamicin. Scale bar is 30 μm

Gentamicin is a reliable selectable marker for P. palmivora

To determine whether gentamicin-based selection could be used on G418-resistant Phytophthora, we assessed growth of transgenic P. palmivora and P. infestans strains carrying the neomycin phosphotransferase (nptII) resistance gene on vegetable V8 juice agar plates containing 100 mg/L gentamicin (Fig. 2a-b). We found that the growth of transgenic P. infestans (Fig. 2a) and P. palmivora (Fig. 2b) strains expressing tdTomato was impaired on selective plates containing gentamicin. Thus, the nptII gene does not confer resistance to gentamicin.

Fig. 2.

Gentamicin is a reliable selectable marker for Phytophthora (a-b) Representative pictures of 5-day-old transgenic P. palmivora LILI (c) or 10-day-old transgenic P. infestans (d) carrying a construct for constitutive expression of the tdTomato fluorescent protein. Plates were grown on V8 or RSA, respectively, and supplemented or not with 100 mg/L gentamicin. c Representative pictures of 5-day-old transgenic P. palmivora LILI transformed with a gentamicin-based pTOR vector, grown on V8 plates containing either no antibiotic (left), 100 mg/L gentamicin (middle) or 100 mg/L geneticin (G418, right). d Representative pictures of infectious hyphae from a gentamicin-resistant P. palmivora strain expressing a constitutive Lifeact:mCitrine reporter, 24 h after infection of a Nicotiana benthamiana leaf. Arrowheads indicate haustoria. Scale bar is 10 μm

To determine whether gentamicin can be used as a selectable marker for P. palmivora, we generated a set of pTOR-Gateway vectors carrying the aminoglycoside 3-N-acetyltransferase I (aac(3)-I or aacC1) gene from Pseudomonas aeruginosa [39] as a replacement for nptII (Additional file 1: Table S1). Using an improved electroporation approach (Supporting Protocol), we transformed the wild-type P. palmivora strain LILI with a pTORGm43GW vector carrying a construct for constitutive expression of an actin-labelling Lifeact:mCitrine reporter under control of the Ham34 promoter. Transformants grew on V8 medium containing gentamicin (Fig. 2c), suggesting that Hsp70pro-driven aacC1 expression efficiently detoxified gentamicin. Furthermore, the growth of gentamicin-resistant P. palmivora strains on V8 plates supplemented with G418 was attenuated (Fig. 2c), confirming that aacC1 does not confer cross-resistance to G418. In addition, gentamicin-resistant P. palmivora strains were able to infect Nicotiana benthamiana leaves and formed intracellular haustoria (Fig. 2d), suggesting that expression of the AAC (3)-I enzyme does not impair the virulence of these strains. Taken together, gentamicin is a reliable selectable marker for P. palmivora.

Gentamicin-based vectors for super-transformation of G418-resistant Phytophthora strains

Next, we assessed the possibility to perform dual selection using both G418 and gentamicin (Fig. 3). To that end, we transformed the G418-resistant P. palmivora LILI-YKDEL strain [15, 40] with vectors carrying the aacC1 gene in addition to a construct for constitutive expression of either an actin-labelling Lifeact:mScarlet-I fluorescent reporter (Fig. 3a-b) or a cytoplasmic tdTomato and a nuclear-localized mTFP1 fluorescent protein (Fig. 3c-d). All regenerated transformants were able to grow on V8 medium containing both G418 and gentamicin and expressed the different reporter genes in their respective subhyphal compartments (Fig. 3b, d). Hence, pTOR-Gateway vectors carrying a gentamicin resistance cassette allow for super-transformation of G418-resistant transgenic P. palmivora strains.

Fig. 3.

Gentamicin-based pTOR vectors enable super-transformation of G418-resistant P. palmivora strains. a A transgenic P. palmivora LILI-YKDEL strain was transformed with a gentamicin-based vector carrying a construct for constitutive expression of a Lifeact:mScarlet-I reporter. b Representative pictures of hyphae grown axenically on V8 plate containing 100 mg/L gentamicin and G418. c The same strain was transformed with a gentamicin-based vector carrying a construct for constitutive expression of a nuclear-localized mTFP1 in addition to a cytoplasmic tdTomato marker. d Representative pictures of hyphae grown axenically on V8 plate containing 100 mg/L gentamicin and G418. Arrowheads indicate nuclei. Scale bar is 10 μm

Discussion

Here we document that gentamicin is a robust selectable marker for P. palmivora that can be used for transformation of wild-type and G418-resistant strains. Many aminoglycosides are primarily used as bactericidal antibiotics. They inhibit protein synthesis by binding to the A-site on the 16S ribosomal RNA of the 30S bacterial ribosome [41, 42]. Besides its activity in prokaryotes, gentamicin selection was used as an efficient selectable marker in eukaryotic plants such as Petunia hybrida [43] and Nicotiana tabacum [44]. Efficient gentamicin-based selection was also reported for Arabidopsis thaliana [43] and, more recently, for the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha [45], although no mechanism of action has been proposed so far. In addition, a bifunctional enzyme conferring resistance to both gentamicin and tobramycin was used for selection of N. tabacum transplastomic lines [46], taking benefit of the prokaryotic translational apparatus of chloroplasts [47]. The low affinity of aminoglycosides for eukaryotic ribosomes is due to differences at two key nucleotides of the ribosomal RNA that occupy the ribosome decoding centre [48, 49]. However, a few aminoglycosides bind to eukaryotic ribosomes are thus are used in nonsense suppression therapy to suppress translation termination at in-frame premature termination codons [50]. Whether gentamicin binds to oomycete ribosomes or mitochondrial ribosomes (mitoribosomes) remain to be determined. Indeed, studies of hybrid bacterial ribosomes containing a decoding site mimicking the human mitochondrial 12S rRNA showed altered protein translation fidelity in the presence of aminoglycosides, suggesting aminoglycosides can interfere with mitoribosomes function [51]. In addition, gentamicin may interfere with other key metabolic processes. For instance, some reports suggest that gentamicin may suppress the ADP ribosylation factor (ARF)-dependent protein trafficking [52].

We found that the nptII selectable marker expressed by G418-resistant P. palmivora strains does not confer resistance to gentamicin, and that growth of P. palmivora strains carrying the aacC1 selectable marker was arrested on V8 plates containing G418, but not gentamicin. Our data are consistent with the specificity of these aminoglycoside processing enzymes. The gene aacC1 [39] used in this study encodes the AMINOGLYCOSIDE 3-N-ACETYLTRANSFERASE I (AAC(3)-I), which has narrow substrate specificity and can only acetylate gentamicin, astromicin and sisomicin [38]. The nptII gene derived from the Tn5 transposon encodes the AMINOGLYCOSIDE 3′-PHOSPHOTRANSFERASE II (APH(3′)-II) which can phosphorylate kanamycin, G418 and gentamicin B, but not members of the gentamicin C complex [38]. Gentamicin C constitutes 80% of the gentamicin sulphate preparations [53] and has more potent antimicrobial activity than the remaining 20% of so-called minor components (mostly gentamicins A, B and X) [54]. Considering substrate specificities of the APH(3′)-II and AAC(3)-I enzymes and composition of the gentamicin antibiotic was crucial for the success of double selection approaches in this study.

Under natural conditions, fungi and oomycetes are often associated with a broad range of bacteria and inter-kingdom communication has been shown [55–57]. While it cannot be excluded that bacterial associations with P. palmivora may provide host range or environmental benefits, our data suggests that P. palmivora strains obtained after several rounds of cultivation on V8 medium containing a mixture of bactericidal and bacteriostatic antibiotics are still capable of readily infecting N. benthamiana. Future work will investigate whether such isolates perform worse on less compatible hosts and whether they are indeed axenic or still have antibiotic resistant bacteria associated with them.

Conclusions

In this study we highlight the usefulness of gentamicin-based selectable marker in oomycetes. We provide evidence for the functionality of the N-acetyltransferase AAC(3)-I in Phytophthora, and demonstrate that it enables super-transformation of well-characterized, G418-resistant strains. We take advantage of these findings to develop a versatile toolbox of gentamicin-based pTOR-Gateway vectors that expand the possibilities to study oomycete cell biology. In addition, we report that gentamicin-based selection does not alter oomycete virulence. Hence, our findings and resources will enhance the study of oomycete biology as well as plant-oomycete interactions.

Methods

Plants and microbial strains and growth conditions

P. palmivora growth conditions, maintenance and zoospore production were described elsewhere [25]. P. infestans growth conditions, maintenance and zoospore production were described elsewhere [58]. P. palmivora strain P16830 (LILI) was isolated from infected oil palm samples harvested in Tumaco Occidental Zone, Colombia [59] and has been obtained from the World Oomycete Genetic Resource collection (https://phytophthora.ucr.edu/). ITS ribosomal sequence can be found under Genbank accession GQ398157. P. infestans strain 88,069 (race 1.3.4.7) was isolated from the Netherlands [60] and obtained from The Sainsbury Laboratory, Norwich, UK. Import and maintenance of P. palmivora and P. infestans are covered by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) plant health licence 114614/208745/4.

N. benthamiana is a laboratory cultivar obtained from The Sainsbury Laboratory, Norwich, UK. Its origin dates back to a collection from the Granites site in central Australia which was sent to the United States in 1939 [61]. Growth conditions were described previously [15]. P. palmivora, P. infestans and N. benthamiana were grown and maintained at the Sainsbury Laboratory (SLCU, United Kingdom).

Plasmid construction

Gentamicin resistance cassette were PCR-amplified from pDONR207 (Invitrogen) vector using the primers GmR_F (5′-ATGTTACGCAGCAGCAACGA-3′) and Hsp70-GmR_IFR (5′-TGGTCGGTCATTTCGAACCCCAGAGTCCCGCTTAGGTGGCGGTACTTGGG-3′). The partial Hsp70 promoter sequence spanning from HpaI restriction site to the beginning of the resistance cassette coding sequence was PCR-amplified from pTORKm43GW using the forward primer Hsp70_IFF (5′-TTATTTAATTTGGTTAACAAATCGGTTTTCGTCGCAAATAGGG-3′) and Hsp70-GmR_R (5′-TCGTTGCTGCTGCGTAACATGCGAAACGGGGCCCTTGTGT-3′). Final amplicons were generated by overlap extension PCR [62] and cloned into a pTORKm43GW by In-Fusion cloning (Clontech, Palo Alto, USA).

Cleaning up of Phytophthora strains

Bacteria growing on Phytophthora cultivation plates hamper normal zoospore release and electroporation. To establish axenic P. palmivora, we harvested zoospores from a bacteria-contaminated plate and used 10 μL volume of the spore suspension to spot inoculate a new plate containing rifampicin (Rif), cefotaxime (Ctx) and spectinomycin (Spec). After 5-day incubation at 25 °C, an agar plug was taken from fresh P. palmivora outgrowth on a Rif/Ctx/Spec plate and subcultured onto a new Rif/Ctx/Spec plate. Mycelia and zoospores produced from these plates were checked for absence of bacterial contamination by inoculation of LB medium with mycelium plugs or zoospore suspension (Supplemental Method). Clean plates were used for further propagation and zoospore electroporation.

Generation of transgenic Phytophthora palmivora

Transgenic Phytophthora palmivora were obtained by zoospore electro-transformation using the method from Huitema et al. (2011) with the following modifications: for electroporation, 680 μl of high concentration (> 106 zoospores/ml), high mobility zoospore suspension was mixed with 80 μl of 10× modified Petri’s solution and 40 μl (20–40 μg) of plasmid DNA. Electroporation settings were as follows: voltage 500 V, capacitance 50 μF, resistance 800 Ω. After electroporation, zoospore suspensions were diluted with clarified V8 medium to 5 mL and incubated at 25 °C for 6 h on a rocking shaker. The encysted zoospore suspension was plated on a 15 cm diameter plate with selective medium containing appropriate antibiotics. Transformants were transferred to fresh selective plates up to 10 days after transformation. A detailed procedure can be found in the Supplemental Method.

Confocal microscopy

Confocal laser scanning microscopy images were acquired with a Leica SP8 laser-scanning confocal microscope equipped with a 25×0.95 numerical aperture (NA) objective (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). A white-light laser was used for excitation at 477 nm for mTFP1 visualisation, 488 nm for mWasabi visualisation, at 514 nm for mCitrine visualisation and at 543 nm for the visualisation of tdTomato. Fluorescence acquisition was done sequentially. Pictures were analysed with ImageJ software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) and plugin Bio-Formats (https://imagej.net/Bio-Formats).

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Figure S1. Growth habit of wild-type P. palmivora and P. infestans strains on several antibiotics. (A-B) Representative pictures of 5-day-old P. palmivora isolate LILI (accession P16830) grown on V8 (A) or 10-day-old P. infestans isolate 88,069 grown on RSA (B). Plates were supplemented with 100 mg/L of either carbenicillin, chloramphenicol, cefotaxime, rifampicin, spectinomycin or tetracycline. Scale bar is 30 μm. Table S1. Gentamicin-based pTOR-Gateway vectors. Gentamicin resistance conferred by the aacC1 gene is indicated by the letter G, in addition to the previously described naming conventions. Supporting protocol. Step-by-step protocol for electro-transformation of Phytophthora palmivora zoospores.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Thomas Torode (SLCU, Cambridge) for proofreading the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- aac(3)-I or aacC1

aminoglycoside 3-N-acetyltransferase I

- AAC(3)-I

AMINOGLYCOSIDE 3-N-ACETYLTRANSFERASE I

- APH(3′)-II

AMINOGLYCOSIDE 3′-PHOSPHOTRANSFERASE II

- ARF

ADP ribosylation factor

- G418

geneticin

- mTFP1

monomeric Teal Fluorescent Protein 1

- nptII

neomycin phosphotransferase

- YKDEL

Yellow Fluorescent Protein containing a C-terminal ER retention signal (YFP:KDEL)

Authors’ contributions

E. E. conceived the experimental strategy, conducted experiments, acquired data, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. T.Y. and L.S. conducted experiments, acquired data and analyzed data. S. S. acquired funding, conceived the experimental strategy, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Gatsby Charitable Foundation (GAT3395/GLD) and by the Royal Society (UF160413). Funding bodies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. Empty plasmids generated during the current study are available in the Addgene (www.addgene.org/) plasmid repository, under accession numbers 112902 to 112906. Final (recombined) plasmids generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Furthermore, the microbial strains P. palmivora strain P16830 and P. infestans strain 88069 are available.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Edouard Evangelisti, Email: edouard.evangelisti@slcu.cam.ac.uk.

Temur Yunusov, Email: temur.yunusov@slcu.cam.ac.uk.

Liron Shenhav, Email: liron.shenhav@slcu.cam.ac.uk.

Sebastian Schornack, Email: sebastian.schornack@slcu.cam.ac.uk.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12866-019-1642-0.

References

- 1.Phillips AJ, Anderson VL, Robertson EJ, Secombes CJ, van West P. New insights into animal pathogenic oomycetes. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Derevnina L, Petre B, Kellner R, Dagdas YF, Sarowar MN, Giannakopoulou A, et al. Emerging oomycete threats to plants and animals. Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol Sci. 2016;371:20150459. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooke DEL, Drenth A, Duncan JM, Wagels G, Brasier CM. A molecular phylogeny of Phytophthora and related oomycetes. Fungal Genet Biol. 2000;30:17–32. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2000.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang X, Tyler BM, Hong C. An expanded phylogeny for the genus Phytophthora. IMA Fungus. 2017;8:355–384. doi: 10.5598/imafungus.2017.08.02.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nowicki M, Foolad MR, Nowakowska M, Kozik EU. Potato and tomato late blight caused by Phytophthora infestans : an overview of pathology and resistance breeding. Plant Dis. 2011;96:4–17. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-05-11-0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savita GSV, Nagpal A. Citrus diseases caused by Phytophthora species. GERF Bull Biosci. 2012;3:18–27. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torres G. A., Sarria G. A., Martinez G., Varon F., Drenth A., Guest D. I. Bud Rot Caused byPhytophthora palmivora: A Destructive Emerging Disease of Oil Palm. Phytopathology. 2016;106(4):320–329. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-15-0243-RVW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grünwald NJ, Garbelotto M, Goss EM, Heungens K, Prospero S. Emergence of the sudden oak death pathogen Phytophthora ramorum. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sena K, Crocker E, Vincelli P, Barton C. Phytophthora cinnamomi as a driver of forest change: implications for conservation and management. For Ecol Manag. 2018;409:799–807. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2017.12.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher MC, Henk DA, Briggs CJ, Brownstein JS, Madoff LC, McCraw SL, et al. Emerging fungal threats to animal, plant and ecosystem health. Nature. 2012;484:186–194. doi: 10.1038/nature10947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardham AR. Cell biology of plant-oomycete interactions. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Judelson HS, Blanco FA. The spores of Phytophthora: weapons of the plant destroyer. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:47–58. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang S, Welsh L, Thorpe P, Whisson SC, Boevink PC, Birch PRJ. The Phytophthora infestans haustorium is a site for secretion of diverse classes of infection-associated proteins. MBio. 2018;9:e01216-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01216-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Attard A, Gourgues M, Callemeyn-Torre N, Keller H. The immediate activation of defense responses in Arabidopsis roots is not sufficient to prevent Phytophthora parasitica infection. New Phytol. 2010;187:449–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evangelisti E, Gogleva A, Hainaux T, Doumane M, Tulin F, Quan C, et al. Time-resolved dual transcriptomics reveal early induced Nicotiana benthamiana root genes and conserved infection-promoting Phytophthora palmivora effectors. BMC Biol. 2017;15:39. doi: 10.1186/s12915-017-0379-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haas BJ, Kamoun S, Zody MC, Jiang RHY, Handsaker RE, Cano LM, et al. Genome sequence and analysis of the Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Nature. 2009;461:393–398. doi: 10.1038/nature08358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamour KH, Mudge J, Gobena D, Hurtado-Gonzales OP, Schmutz J, Kuo A, et al. Genome sequencing and mapping reveal loss of Heterozygosity as a mechanism for rapid adaptation in the vegetable pathogen Phytophthora capsici. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2012;25:1350–1360. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-02-12-0028-R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ali SS, Shao J, Lary DJ, Kronmiller BA, Shen D, Strem MD, et al. Phytophthora megakarya and Phytophthora palmivora, closely related causal agents of cacao black pod rot, underwent increases in genome sizes and gene numbers by different mechanisms. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9:536–557. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evx021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jupe J, Stam R, Howden AJM, Morris JA, Zhang R, Hedley PE, et al. Phytophthora capsici-tomato interaction features dramatic shifts in gene expression associated with a hemi-biotrophic lifestyle. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R63. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-6-r63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feussner I, Polle A. What the transcriptome does not tell - proteomics and metabolomics are closer to the plants’ patho-phenotype. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2015;26:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Resjö S, Brus M, Ali A, Meijer HJG, Sandin M, Govers F, et al. Proteomic analysis of Phytophthora infestans reveals the importance of Cell Wall proteins in pathogenicity. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2017;16:1958–1971. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M116.065656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang Y, Tyler BM. Efficient disruption and replacement of an effector gene in the oomycete Phytophthora sojae using CRISPR/Cas9. Mol Plant Pathol. 2016;17:127–139. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kots K, Meijer HJG, Bouwmeester K, Govers F, Ketelaar T. Filamentous actin accumulates during plant cell penetration and cell wall plug formation in Phytophthora infestans. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:909–920. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2383-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ah-Fong Audrey M. V., Kagda Meenakshi, Judelson Howard S. Methods in Molecular Biology. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2018. Illuminating Phytophthora Biology with Fluorescent Protein Tags; pp. 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evangelisti E, Shenhav L, Yunusov T, Le Naour-Vernet M, Rink P, Schornack S. Centrin-anchored hydrodynamic shape changes underpin active nuclear rerouting in branched hyphae of an oomycete pathogen. bioRxiv. 2019. 10.1101/652255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Wang S, Boevink PC, Welsh L, Zhang R, Whisson SC, Birch PRJ. Delivery of cytoplasmic and apoplastic effectors from Phytophthora infestans haustoria by distinct secretion pathways. New Phytol. 2017;216:205–215. doi: 10.1111/nph.14696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Judelson HS, Tyler BM, Michelmore RW. Transformation of the oomycete pathogen, Phytophthora infestans. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1991;4:602–607. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-4-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cvitanich C, Judelson HS. Stable transformation of the oomycete, Phytophthora infestans, using microprojectile bombardment. Curr Genet. 2003;42:228–235. doi: 10.1007/s00294-002-0354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vijn I, Govers F. Agrobacterium tumefaciens mediated transformation of the oomycete plant pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Mol Plant Pathol. 2003;4:459–467. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2003.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu D, Navet N, Liu Y, Uchida J, Tian M. Establishment of a simple and efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transformation system for Phytophthora palmivora. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:204. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0825-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huitema E, Smoker M, Kamoun S. A straightforward protocol for electro-transformation of Phytophthora capsici zoospores. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;712:129–135. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-998-7_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ah-Fong AMV, Judelson HS. Vectors for fluorescent protein tagging in Phytophthora: tools for functional genomics and cell biology. Fungal Biol. 2011;115:882–890. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Attard A, Evangelisti E, Kebdani-Minet N, Panabières F, Deleury E, Maggio C, et al. Transcriptome dynamics of Arabidopsis thaliana root penetration by the oomycete pathogen Phytophthora parasitica. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:538. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farouk F, Azzazy HME, Niessen WMA. Challenges in the determination of aminoglycoside antibiotics, a review. Anal Chim Acta. 2015;890:21–43. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2015.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hermann T. Aminoglycoside antibiotics: old drugs and new therapeutic approaches. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1841–1852. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7034-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pietrzak M, Shillito RD, Hohn T, Potrykus I. Expression in plants of two bacterial antibiotic resistance genes after protoplast transformation with a new plant expression vector. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:5857–5868. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.14.5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Becker D, Kemper E, Schell J, Masterson R. New plant binary vectors with selectable markers located proximal to the left T-DNA border. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;20:1195–1197. doi: 10.1007/BF00028908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaw KJ, Rather PN, Hare RS, Miller GH. Molecular genetics of aminoglycoside resistance genes and familial relationships of the aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:138–63. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8385262%0A. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC372903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Wohlleben W, Arnold W, Bissonnette L, Pelletier A, Tanguay A, Roy PH, et al. On the evolution of Tn 21-like multiresistance transposons: sequence analysis of the gene (aacC1) for gentamicin acetyltransferase-3-I (AAC (3)-I), another member of the Tn 21-based expression cassette. MGG Mol Gen Genet. 1989;217:202–208. doi: 10.1007/BF02464882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rey T, Chatterjee A, Buttay M, Toulotte J, Schornack S. Medicago truncatula symbiosis mutants affected in the interaction with a biotrophic root pathogen. New Phytol. 2015;206:497–500. doi: 10.1111/nph.13233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kotra LP, Haddad J, Mobashery S. Aminoglycosides: perspectives on mechanisms of action and resistance and strategies to counter resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3249–3256. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.12.3249-3256.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tenson T, Mankin A. Antibiotics and the ribosome. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:1664–1677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayford MB, Medford JI, Hoffman NL, Rogers SG, Klee HJ. Development of a plant transformation selection system based on expression of genes encoding gentamicin Acetyltransferases. Plant Physiol. 2008;86:1216–1222. doi: 10.1104/pp.86.4.1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carrer H, Staub JM, Maliga P. Gentamycin resistance in Nicotiana conferred by AAC (3)-I, a narrow substrate specificity acetyltransferase. Plant Mol Biol. 1991;17:301–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00039510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ishizaki K, Nishihama R, Ueda M, Inoue K, Ishida S, Nishimura Y, et al. Development of gateway binary vector series with four different selection markers for the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tabatabaei I, Ruf S, Bock R. A bifunctional aminoglycoside acetyltransferase/phosphotransferase conferring tobramycin resistance provides an efficient selectable marker for plastid transformation. Plant Mol Biol. 2017;93:269–281. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0560-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tiller N, Bock R. The translational apparatus of plastids and its role in plant development. Mol Plant. 2014;7:1105–1120. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssu022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Recht MI, Douthwaite S, Puglisi JD. Basis for prokaryotic specificity of action of aminoglycoside antibiotics. EMBO J. 1999;18:3133–3138. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lynch SR, Puglisi JD. Structural origins of aminoglycoside specificity for prokaryotic ribosomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;306:1037–1058. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keeling KM, Xue X, Gunn G, Bedwell DM. Therapeutics based on stop codon Readthrough. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2014;15:371–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fosso MY, Li Y, Garneau-Tsodikova S. New trends in the use of aminoglycosides. Med Chem Commun. 2014;5:1075–1091. doi: 10.1039/C4MD00163J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin L, Wagner MC, Cocklin R, Kuzma A, Harrington M, Molitoris BA, et al. The antibiotic gentamicin inhibits specific protein trafficking functions of the Arf1/2 family of GTPases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:246–254. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00450-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vydrin AF, Shikhaleev IV, Makhortov VL, Shcherenko NN, Kolchanova NV. Component composition of gentamicin sulfate preparations. Pharm Chem J. 2003;37:448–450. doi: 10.1023/A:1027372416983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weinstein MJ, Wagman GH, Oden EM, Marquez JA. Biological activity of the antibiotic components of the gentamicin complex. J Bacteriol. 1967;94:789–790. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.3.789-790.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chee KH, Newhook FJ. Relationship of micro-organisms to sporulation of Phytophthora cinnamomi rands. N Z J Agric Res. 1966;9:32–43. doi: 10.1080/00288233.1966.10418115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kong P, Lee BWK, Zhou ZS, Hong C. Zoosporic plant pathogens produce bacterial autoinducer-2 that affects Vibrio harveyi quorum sensing. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;303:55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01861.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kemen E. Microbe-microbe interactions determine oomycete and fungal host colonization. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2014;20:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fawke S, Torode TA, Gogleva A, Fich EA, Sørensen I, Yunusov T, et al. Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 6 controls filamentous pathogen interactions and cell wall properties of the tomato and Nicotiana benthamiana leaf epidermis. New Phytol. 2019;223:1547–1559. doi: 10.1111/nph.15846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Torres GA, Sarria GA, Varon F, Coffey MD, Elliott ML, Martinez G. First report of bud rot caused by Phytophthora palmivora on African oil palm in Colombia. Plant Dis. 2010;94:1163. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-94-9-1163A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van West P, De Jong AJ, Judelson HS, Emons AMC, Govers F. The ipiO gene of Phytophthora infestans is highly expressed in invading hyphae during infection. Fungal Genet Biol. 1998;23:126–138. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1998.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bally J, Jung H, Mortimer C, Naim F, Philips JG, Hellens R, et al. The rise and rise of Nicotiana benthamiana : a Plant for all Reasons. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2018;56:405–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080417-050141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bryksin AV, Matsumura I. Overlap extension PCR cloning: a simple and reliable way to create recombinant plasmids. Biotechniques. 2010;48:463–465. doi: 10.2144/000113418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Figure S1. Growth habit of wild-type P. palmivora and P. infestans strains on several antibiotics. (A-B) Representative pictures of 5-day-old P. palmivora isolate LILI (accession P16830) grown on V8 (A) or 10-day-old P. infestans isolate 88,069 grown on RSA (B). Plates were supplemented with 100 mg/L of either carbenicillin, chloramphenicol, cefotaxime, rifampicin, spectinomycin or tetracycline. Scale bar is 30 μm. Table S1. Gentamicin-based pTOR-Gateway vectors. Gentamicin resistance conferred by the aacC1 gene is indicated by the letter G, in addition to the previously described naming conventions. Supporting protocol. Step-by-step protocol for electro-transformation of Phytophthora palmivora zoospores.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. Empty plasmids generated during the current study are available in the Addgene (www.addgene.org/) plasmid repository, under accession numbers 112902 to 112906. Final (recombined) plasmids generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Furthermore, the microbial strains P. palmivora strain P16830 and P. infestans strain 88069 are available.