Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the associations between intraocular pressure (IOP) measurements obtained by different tonometric methods and rates of visual field loss in a cohort of glaucoma patients followed over time.

Design

Prospective observational cohort study.

Participants

This study included 213 eyes of 125 glaucomatous patients that were followed for an average of 2.4 ± 0.6 years.

Methods

At each visit, IOP measurements were obtained using Goldmann applanation tonometer (GAT), Ocular Response Analyzer (ORA) corneal-compensated IOP (IOPcc), and ICare rebound tonometer (RBT). Rates of visual field loss were assessed by Standard Automated Perimetry (SAP) mean deviation (MD). Linear mixed models were used to investigate the relationship between mean IOP by each tonometer and rates of visual field loss over time, while adjusting for age, race, central corneal thickness, and corneal hysteresis (CH).

Main Outcome Measures

Strength of associations (R2) between IOP measurements from each tonometer and rates of SAP MD change over time.

Results

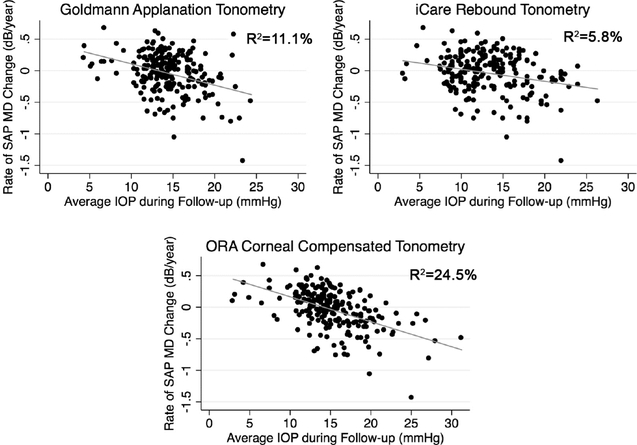

Average values for mean IOP over time measured by GAT, ORA and RBT were 14.4 ± 3.3, 15.2 ± 4.2, and 13.4 ± 4.2 mmHg, respectively. Mean IOPcc had the strongest relationship with SAP MD loss over time (R2=24.5%), and was significantly different from the models using mean GAT IOP (R2 =11.1%; 95% confidence interval (CI) of the difference: 6.6% to 19.6%) and mean RBT IOP (R2=5.8%; 95% CI of the difference: 11.1% to 25.0%).

Conclusions

Mean ORA IOPcc was more predictive of rates of visual field loss than mean IOP obtained by GAT or RBT. By correcting for corneal-induced artifacts, IOPcc measurements may present significant advantages for predicting clinically relevant outcomes in glaucoma patients.

PRÉCIS

In a longitudinal cohort study, corneal-compensated intraocular pressure measurements obtained by the Ocular Response Analyzer performed better in predicting rates of visual field loss than measurements from Goldmann and rebound tonometry.

INTRODUCTION

Glaucoma is a progressive optic neuropathy characterized by degeneration of retinal ganglion cells, resulting in a characteristic appearance of the optic disc and concomitant pattern of visual field loss.1 Although most glaucoma patients show some evidence of disease progression if followed long enough, the rate of deterioration can be highly variable among them. Detecting patients at high risk for fast progression is essential, as it will dictate management decisions.

High intraocular pressure (IOP) is the main risk factor associated with glaucoma progression2–4 and Goldmann applanation tonometry (GAT) is still considered the gold-standard for assessing IOP in clinical practice. However, several studies have shown that many glaucoma patients may present progressive damage despite relatively low GAT IOPs, while others may remain stable despite elevated IOP levels measured with this instrument.5, 6 The dependency of GAT measurements on corneal properties may explain, at least in part, these findings.7 In eyes with thick corneas, GAT IOP measurements tend to be overestimated, while underestimation may occur in eyes with thin corneas.8,9

In order to overcome GAT limitations, other tonometers have been proposed, such as the Ocular Response Analyzer (ORA, Reichert, Inc.). The ORA incorporates measurements of corneal biomechanics in calculations of a “corneal-compensated” IOP, or IOPcc. The corneal biomechanics parameters are obtained by studying the behavior of the cornea once it is subject to pressure by an air jet pulse while monitored by infrared cameras.10 Previous studies have shown that IOPcc measurements seem to be less influenced by central corneal thickness compared to GAT.8, 11 Another tonometric method, rebound tonometry, has also been suggested to be less affected by corneal thickness, although this issue remains of considerable debate in the literature.12, 13 The ICare Rebound Tonometer (RBT, Tiolat, Oy) is a hand-held, lightweight, contact tonometer that has the advantage of being portable and not requiring topical anesthetic.

There have been many studies in the literature comparing IOP measurements obtained by different forms of tonometry and their relationship with corneal properties.7, 12 However, the ultimate value of IOP measurements resides in their ability to predict clinically relevant outcomes in glaucoma, such as risk for visual field progression. Therefore, although IOP comparisons among instruments may provide information about their comparability and agreement, the best method to assess and compare their utility is to investigate how well their measurements are associated with clinically relevant outcomes in the disease, such as rates of visual field progression.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the relationship between IOP measurements obtained by GAT, ORA and ICare with rates of visual field progression in a cohort of glaucoma patients followed over time.

METHODS

This was a longitudinal observational cohort study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and the institutional review board and human subjects committee approved all methods. All methods adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects and the study was conducted in accordance with the regulations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

At each visit during follow-up, participants underwent a comprehensive ophthalmologic examination including review of medical history, best-corrected visual acuity, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, gonioscopy and IOP measurements using GAT, ORA and ICare in a randomized sequence. Trained technicians performed the IOP measurements. Subjects also underwent visual field testing at each visit using standard automated perimetry (SAP) with the Swedish Interactive Threshold Algorithm (SITA) Standard with 24–2 strategy of the Humphrey Field Analyzer II-i, model 750 (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, CA). A minimum of 4 reliable visual field tests (≤33% fixation losses and ≤15% false-positive errors) was required for inclusion in this study. In addition, visual fields were reviewed and excluded in the presence of artifacts such as eyelid or rim artifacts, learning effect, or abnormalities that could indicate diseases other than glaucoma. Participants had central corneal thickness (CCT) measurements obtained at the baseline visit by a trained technician using ultrasound pachymeter Pachette GDH 500 (DGH Technology, Inc., Philadelphia, PA).

The study included patients diagnosed with primary open-angle glaucoma. Eyes were classified as glaucomatous if they had two or more repeatable glaucomatous visual field defects at baseline, defined as a pattern standard deviation with P<0.05, or a Glaucoma Hemifield Test result outside normal limits, and corresponding optic nerve damage. Subjects were excluded if they presented any other ocular or systemic disease that could affect the optic nerve or the visual field. Subjects were followed every 6 months.

Goldmann Applanation Tonometry

The IOP was measured using GAT model AT 900® (Haag-Streit International, Koniz, Switzerland). GAT obtains the IOP indirectly based on the Imbert-Fick principle, which states that the pressure within a sphere is approximately equal to the external force needed to flatten a portion of the sphere divided by the area of the sphere that is flattened.14 The GAT instrument used for this study was checked monthly to confirm proper calibration.

Ocular Response Analyzer

The ORA (Reichert Technologies, Inc., Depew, NY, USA) is a noncontact tonometer that measures IOP by applanation of the cornea with a pulse of air.15 Three measurements were obtained at each visit for each eye, and the average of the measurements per eye was considered for analysis. The device provides a waveform score to reflect the quality of measurements. Only measurements associated with a waveform score greater than 5 were considered for inclusion. The ORA principles of operation have been described elsewhere.8, 15 In brief, at the moment the air reaches the cornea, it exerts an inward pressure that leads to corneal applanation, and then to corneal concavity. Milliseconds later, the airflow ceases and the outward rebound of the cornea leads to a second corneal applanation. P1 represents the pressure of applanation on inward corneal motion and P2 the pressure of applanation on outward motion of the cornea.15 The average of P1 and P2 is reported as the Goldmann correlated IOP (IOPg), whereas the difference between the two applanation pressures is the corneal hysteresis (CH) parameter. From these parameters, ORA uses a proprietary calculation to obtain a measure of IOPcc or corneal-compensated IOP.15

ICare Rebound Tonometry

The RBT (Tiolat, Oy, Helsinki, Finland) is a form of dynamic applanation tonometry that uses the impact rebound principle to measure IOP. Details of the instrument’s mechanisms have been described elsewhere.16 The main advantages of RBT are its portability and the ability to measure IOP without requiring topical anesthetic or staining, thereby reducing the possibility of damaging the corneal surface and cross-contamination.

Statistical Analysis

Rates of visual field loss were evaluated by the parameter mean deviation (MD) over time through linear mixed models.17 Details of the use of these models have been previously described.18 Briefly, in linear mixed models, the average evolution of the outcome variable (i.e., SAP MD) is described using a linear function of time, and random intercepts and random slopes introduce subject and eye-specific deviations from this average evolution. The model can account for the fact that different eyes can have different rates of visual field loss over time, while also accommodating correlations between both eyes of the same individual. Slopes for individual eyes were estimated by best linear unbiased predictions.

We then investigated the association between mean IOP measurements over time obtained by each tonometer and rates of MD loss over time. Multivariable models were constructed to adjust for potentially confounding factors, such as age, race, CCT and CH. The strength of association between mean IOP measurements by a tonometer and rates of visual field loss was assessed by the R2 for the linear model. Values of R2 for the different linear models for each tonometer were then compared and statistically significant differences were determined by a bootstrap resampling procedure. Bootstrap resampling was performed at the patient level to account for correlations from both eyes of the same subject. We also investigated the association between mean IOP measurements obtained by each tonometer and rates of visual field index (VFI) loss over time.

All statistical analyses were performed using the commercially available software Stata, version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). The alpha level (type I error) was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

This study included 213 eyes of 125 glaucomatous patients followed for an average of 2.4 ± 0.6 years (range, 1.3 to 3.7 years). Included eyes had a mean of 7.4 SAP tests (range 4 to 15) performed during follow-up. Table 1 shows baseline clinical and demographic information for eyes included in the study. Average values of mean IOP over time measured by GAT, ORA IOPcc, and RBT were 14.4 ± 3.3, 15.2 ± 4.2, and 13.4 ± 4.2 mmHg, respectively. Average baseline CCT was 536.3 ± 43.1 μm and average CH was 9.5 ± 1.8 mmHg.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects included in the study

| Parameter | 213 Eyes of 125 Patients |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 68.0 ± 11.3 |

| Gender, n (%) female | 60 (48.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 77 (61.6) |

| African American | 34 (27.2) |

| Asian | 9 (7.2) |

| Other | 5 (4.0) |

| Mean IOPGAT, mmHg | 14.4 ± 3.3 |

| Mean IOPRBT, mmHg | 13.4 ± 4.2 |

| Mean IOPCC, mmHg | 15.2 ± 4.2 |

| CCT, μm | 536.3 ± 43.1 |

| Baseline CH, mmHg | 9.5 ± 1.8 |

| Baseline SAP 24–2 MD, dB | −3.7 ± 5.5 |

| SAP 24–2 MD at the end of follow-up, dB | −4.0 ± 5.7 |

| Baseline SAP 24–2 VFI, % | 90.2 ± 15.3 |

| SAP 24–2 VFI at the end of follow-up, % | 89.4 ± 15.8 |

| Baseline SAP 24–2 PSD, dB | 4.4 ± 3.7 |

| SAP 24–2 PSD at the end of follow-up, dB | 4.6 ± 3.8 |

IOPGAT = intraocular pressure measured by Goldmann applanation tonometer; IOPRBT = intraocular pressure measured by ICare rebound tonometer; IOPCC = intra-ocular pressure with corneal compensation measured by Ocular Response Analyzer; CCT = central corneal thickness; μm = micrometers; CH = corneal hysteresis; SAP = standard automated perimetry; MD = mean deviation; VFI = visual field index; PSD = pattern standard deviation.

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise noted.

Table 2 shows the effect of mean IOP obtained by each tonometer on rates of SAP MD loss. Higher mean IOP measurements provided by GAT, RBT, and ORA IOPcc were significantly associated with faster rates of visual field loss over time. For GAT, each 1 mmHg higher mean IOP during follow-up was associated with a 0.04 dB/year faster loss in MD (P=0.013), whereas for ORA IOPcc the corresponding number was 0.05 dB/year (P<0.001) and for RBT, 0.02 dB/year (P=0.037). Baseline CH had a significant effect on rates of SAP MD progression over time, with each 1 mmHg lower CH associated with 0.09 dB/year faster loss (P=0.001). Older eyes also were at increased risk for faster progression with 0.02 dB/year faster loss for each year older (P<0.001). The associations between race and CCT with rates of SAP MD change over time were not statistically significant in this sample. Table 2 also shows the results of the multivariable models adjusting for age, race, CCT, and CH. IOP measurements from all three tonometers were significantly associated with faster rates of SAP MD loss in multivariable models.

Table 2.

Results of univariable and multivariable models* assessing the association of each intraocular pressure parameter with rates of standard automated perimetry mean deviation change over time

| Parameter | Univariable Models | Multivariable Models | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (CI) | P-Value | Coefficient (CI) | P-Value | |

| Mean IOPGAT, per 1 mmHg higher | −0.04 (−0.06 to −0.01) | 0.013 | −0.03 (−0.06 to 0.00) | <0.026 |

| Mean IOPRBT, per 1 mmHg higher | −0.02 (−0.05 to 0.00) | 0.037 | −0.03 (−0.06 to −0.01) | <0.004 |

| Mean I0PCC, per 1 mmHg higher | −0.05 (−0.07 to −0.02) | <0.001 | −0.04 (−0.07 to −0.01) | <0.002 |

| Baseline age, per 1 year older | −0.02 (−0.02 to −0.01) | <0.001 | N/A | N/A |

| Race, African American | −0.14 (−0.33 to 0.06) | 0.161 | N/A | N/A |

| Baseline CH, per 1 mmHg lower | −0.09 (−0.14 to −0.03) | 0.001 | N/A | N/A |

| CCT, per 100 μm thinner | −0.07 (−0.14 to 0.28) | 0.499 | N/A | N/A |

Each multivariable model evaluated the association between rates of visual field loss and mean intraocular pressure (IOP) obtained by a specific tonometer, while adjusting for baseline age, race, baseline CH and CCT.

CI = confidence intervals; IOPGAT = intraocular pressure measured by Goldmann applanation tonometer; IOPRBT = intraocular pressure measured by ICare rebound tonometer; IOPCC = Ocular Response Analyzer corneal-compensated intraocular pressure; CH = corneal hysteresis; CCT = central corneal thickness.

Figure 1 shows the relationship between slopes of change in SAP MD and mean IOP measured by the three instruments. ORA IOPcc had the strongest association with rates of visual field loss (R2 =24.5%), which was significantly different from the association observed for GAT IOP [R2=11.1%; 95% confidence interval (CI) of the difference: 6.6% to 19.6%] and RBT IOP (R2=5.8%; 95% CI of the difference: 11.1% to 25.0%) models. Comparison between R2 values from models using RBT IOP and GAT IOP showed no statistically significant difference (95% CI of the difference: −0.4% to 12.8%).

Figure 1.

Scatterplot illustrating the relationship between rates of change in standard automated perimetry mean deviation (MD) and intraocular pressure (IOP) measurements obtained by Goldmann applanation tonometry, ocular response analyzer corneal-compensated tonometry and iCare rebound tonometry.

Similar results were obtained for analysis performed with VFI (Table 3, available at www.aaoiournal.org). ORA IOPcc also had the strongest association with rates of visual field loss measured with VFI (R2=29.3%), compared to GAT IOP (R2=16.6%) and RBT IOP (R2=10.4%).

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrated significant associations between IOP measurements obtained by different tonometers and glaucomatous visual field progression. However, mean IOPcc measurements had a significantly stronger value in predicting rates of visual field loss over time than those obtained by GAT or RBT. This finding suggests that by taking into account information on corneal biomechanics, IOPcc may be more predictive of clinically relevant outcomes in glaucoma. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective longitudinal study to compare the association between IOP obtained by different tonometers and rates of visual field loss in glaucoma.

Although GAT has long been considered the gold standard in clinical practice, it is well known that its measurements can be impacted by corneal properties. Cornea-induced artifacts decrease the ability of GAT-measured IOP to predict glaucomatous damage. This was clearly shown by the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS), where many individuals with high GAT-measured IOP but thick corneas had low risk of developing glaucoma over time; whereas many individuals with low GAT IOP but thin corneas had high risk of progression.19 However, the impact of corneal properties on tonometric artifacts does not seem to be related only to thickness. A study by Liu and Roberts20 attempted to quantitatively analyze the influence of corneal biomechanical properties on GAT measurements through a mathematical model. They demonstrated that variations in the elasticity of the cornea within a range predicted to occur in a normal population would result in an error of IOP measurement as high as 17mmHg, an effect that was even higher than the one induced by variations in corneal thickness. The ORA-measured IOPcc attempts to correct for corneal biomechanical properties besides thickness. As such, IOPcc would represent a measurement that is less affected by corneal artifacts, as shown in a previous study.21 Even though a lower impact of corneal artifacts has been already previously demonstrated for IOPcc,11,12 the ultimate benefit of such measurements in clinical practice can only be demonstrated by investigating their association with clinically relevant outcomes. In our study, we showed that IOPcc measurements had a stronger association with rates of visual field loss over time compared to GAT IOP, with R2 of 24. 5% versus 11.1%, respectively, for the association with rates of MD change. IOPcc explained more than two times the variance of rates of change in our sample compared to GAT, and this most likely represents the fact that IOPcc measurements are more closely related to the true IOP measurements in the eye.

Previous longitudinal studies have shown that lower CH values are related to faster glaucoma progression. 18, 22, 23 However, it is still unclear why CH might be related to risk of glaucoma development and progression. It has been hypothesized that CH might be a surrogate biomarker to the biomechanical properties of tissues located posteriorly in the eye, such as lamina cribrosa and peripapillary sclera. According to this hypothesis, a low CH would increase the risk for glaucomatous damage possibly by being associated with a reduced capacity of relevant posterior ocular structures in dampening IOP peaks or fluctuations.24–29 It is possible that the higher predictive ability of IOPcc measurements in our study is related to the fact that this parameter incorporates information derived from CH. In fact, formulas used to calculate CH and IOPcc are similar. CH is obtained by subtracting the IOP measurements obtained at the inward (P1) and outward (P2) applanation states with the ORA, or simply, P1-P2. IOPcc measurements are also derived from a subtraction of the applanation pressures, but by using a correction factor obtained from studies of eyes undergoing LASIK refractive surgery. The correction factor was the value that minimized the difference between IOP pre- and post-LASIK surgery. By generating the IOPcc measurement, the idea was to minimize the impact of cornea-induced artifact on IOP.

Our study also investigated IOP measurements obtained by rebound tonometry. The RBT is a simple, portable and quick to use tonometer, which does not require anesthesia. Unfortunately, RBT measurements had the worst performance among the studied methods to predict visual field progression, with R2 of only 5.8%, or over 4 times lower than that obtained for IOPcc. Although the relative weak predictive value of RBT may be related to corneal artifacts, the fact that its predictive value was also lower than that of GAT, although without reaching statistical significance, indicates that other factors may also be playing a role.

It is important to note that although IOPcc had the strongest value in predicting rates of visual field progression in our study, the R2 for the association with rates of MD change was still only 24.5%, that is, approximately three quarters of the variance in the rates of change still remained unexplained by IOPcc. This is likely related to several factors, including noise and variability in both tonometric and visual field measurements, as well as the role of other risk factors. In addition, a limitation of our study is that we only investigated the value of mean IOP measurements over time, obtained from a limited number of office visits. A more comprehensive assessment of IOP peaks and fluctuations over the 24h period and in the long-term would likely have resulted in a better predictive value. At each visit, IOP was measured once with GAT as opposed to 3 times with ORA. In contrast to GAT measurements, the examiner has no control about whether ORA IOP measurements reflect the systolic or diastolic IOP. Therefore, the manufacturer has recommended to take an average of 3 ORA measurements to dilute this effect. Taking 3 measurements may have rendered ORA mean IOP measurements more precise in relation to taking only one measurement as done with GAT. However, this was needed to counterbalance the potential increase in ORA variability resulting from the effects of ocular pulse amplitude, and the design of our study directly reflects how these instruments are generally used in clinical practice.

Another potential limitation of our study is that we did not consider the effect of reductions of IOP in relation to pre-treatment levels or the potential effects of different treatment strategies on risk of progression. However, previous studies provide strong support for mean IOP as an important risk factor for progression.30,31 Also, our study design replicates a scenario that is commonly seen in clinical practice when treatment decisions have to be made without knowledge of pretreatment IOP. Although relatively short, the follow-up period was the same for all devices, and we were able to identify statistically significant differences within the limited time frame of the study, both on analyses performed with MD as well as VFI. However, future investigations should attempt to evaluate the relationship between IOP measured by these tonometers over a longer time frame, as well as using other structural and functional parameters to monitor progression.

In conclusion, IOPcc measurements were more strongly associated with rates of visual field progression in glaucoma patients as compared to GAT and RBT. By correcting for corneal-induced artifacts, IOPcc measurements may present significant advantages for predicting clinically relevant outcomes in glaucoma patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health/National Eye Institute grant EY021818 (F.A.M); fellowship grant from Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) 233829/2014-8 (A.D.-F.).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure(s):

Bianca N. Susanna: none; Nara G. Ogata: none; Fábio B. Daga: none; Carolina N. Susanna: none; Alberto Diniz-Filho: none; Felipe A. Medeiros: Alcon Laboratories (C, F, R), Bausch & Lomb (F), Carl Zeiss Meditec (C, F, R), Heidelberg Engineering (F), Merck (F), Allergan (C, F), Sensimed (C), Topcon (C), Reichert (C, R).

REFERENCES

- 1.Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA 2014;311 (18): 1901–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration.The AGIS Investigators. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;130(4):429–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien C, Schwartz B, Takamoto T. Intraocular pressure and the rate of visual field loss in chronic open-angle glaucoma. American journal of ophthalmology 1991;111 (4):491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leske MC, Heijl A, Hyman L, et al. Predictors of long-term progression in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Ophthalmology 2007;114(11):1965–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliver JE, Hattenhauer MG, Herman D, et al. Blindness and glaucoma: a comparison of patients progressing to blindness from glaucoma with patients maintaining vision. American journal of ophthalmology 2002;133(6):764–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulzer M, Drance SM, Douglas GR. A comparison of treated and untreated glaucoma suspects. Ophthalmology 1991;98(3):301–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J, Roberts CJ. Influence of corneal biomechanical properties on intraocular pressure measurement: quantitative analysis. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery 2005;31 (1):146–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medeiros FA, Weinreb RN. Evaluation of the influence of corneal biomechanical properties on intraocular pressure measurements using the ocular response analyzer. Journal of glaucoma 2006;15(5):364–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitacre MM, Stein R. Sources of error with use of Goldmann-type tonometers. Survey of ophthalmology 1993;38(1):1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glass DH, Roberts CJ, Litsky AS, Weber PA. A Viscoelastic Biomechanical Model of the Cornea Describing the Effect of Viscosity and Elasticity on Hysteresis. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2008;49(9):3919–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ouyang P-B, Li C-Y, Zhu X-H, Duan X-C. Assessment of intraocular pressure measured by Reichert Ocular Response Analyzer, Goldmann Applanation Tonometry, and Dynamic Contour Tonometry in healthy individuals. International Journal of Ophthalmology 2012;5(1): 102–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jorge JM, Gonzalez-Meijome JM, Queiros A, et al. Correlations between corneal biomechanical properties measured with the ocular response analyzer and ICare rebound tonometry. J Glaucoma 2008;17(6):442–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chui W-s, Lam A, Chen D, Chiu R The Influence of Corneal Properties on Rebound Tonometry. Ophthalmology 2008;115(1):80–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldmann H, Schmidt T. [Applanation tonometry]. Ophthalmologica 1957; 134(4):221–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luce DA. Determining in vivo biomechanical properties of the cornea with an ocular response analyzer. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery 2005;31(1):156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies LN, Bartlett H, Mallen EA, Wolffsohn JS. Clinical evaluation of rebound tonometer. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2006;84(2):206–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medeiros FA, Alencar LM, Zangwill LM, et al. The Relationship between Intraocular Pressure and Progressive Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Loss in Glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2009;116(6):1125–33.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang C, Tatham AJ, Abe RY, et al. Corneal Hysteresis and Progressive Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Loss in Glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon MO, Beiser JA, Brandt JD, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: baseline factors that predict the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120(6):714–20; discussion 829–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu J, Roberts CJ. Influence of corneal biomechanical properties on intraocular pressure measurement: quantitative analysis. J Cataract Refract Surg 2005;31 (1 ):146–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medeiros FA, Weinreb RN. Evaluation of the influence of corneal biomechanical properties on intraocular pressure measurements using the ocular response analyzer. J Glaucoma 2006;15(5):364–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Moraes CV, Hill V, Tello C, et al. Lower corneal hysteresis is associated with more rapid glaucomatous visual field progression. J Glaucoma 2012;21(4):209–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medeiros FA, Meira-Freitas D, Lisboa R, et al. Corneal hysteresis as a risk factor for glaucoma progression: a prospective longitudinal study. Ophthalmology 2013; 120(8): 1533–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burgoyne CF, Downs JC, Bellezza AJ, et al. The optic nerve head as a biomechanical structure: a new paradigm for understanding the role of IOP-related stress and strain in the pathophysiology of glaucomatous optic nerve head damage. Prog Retin Eye Res 2005;24(1):39–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigal IA, Flanagan JG, Ethier CR. Factors influencing optic nerve head biomechanics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005;46(11):4189–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson CS, Mian SI, Moroi S, et al. Role of corneal elasticity in damping of intraocular pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007;48(6):2540–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J, He X. Corneal stiffness affects IOP elevation during rapid volume change in the eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2009;50(5):2224–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L, Albon J, Jones H, et al. Collagen microstructural factors influencing optic nerve head biomechanics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56(3):2031–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lanzagorta-Aresti A, Perez-Lopez M, Palacios-Pozo E, Davo-Cabrera J. Relationship between corneal hysteresis and lamina cribrosa displacement after medical reduction of intraocular pressure. Br J Ophthalmol 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medeiros FA, Brandt J, Liu J, et al. IOP as a risk factor for glaucoma development and progression. In: Weinreb RN, Brandt JD, Garway-Heath DF, Medeiros FA, eds. Intraocular Pressure: Reports and Consensus Statements of the 4th Global AIGS Consensus Meeting on Intraocular Pressure The Hague, the Netherlands: Kugler; 2007:59–74. WGA Consensus Series 4. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leske MC, Heijl A, Hussein M, et al. Factors for glaucoma progression and the effect of treatment: the early manifest glaucoma trial. Archives of ophthalmology 2003;121 (1 ):48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.