Clinically stable miscarriage patients presenting to the emergency department have baseline socioeconomic disadvantages and are less satisfied than those presenting to ambulatory clinics.

Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To quantitatively and qualitatively describe the patient experience for clinically stable patients presenting with miscarriage to the emergency department (ED) or ambulatory clinics.

METHODS:

We present a subanalysis of a mixed-methods study from 2016 on factors that influence miscarriage treatment decision-making among clinically stable patients. Fifty-four patients were evaluated based on location of miscarriage care (ED or ambulatory-only), and novel parameters were assessed including timeline (days) from presentation to miscarriage resolution, number of health system interactions, and number of specialty-based provider care teams seen. We explored themes around patient satisfaction through in-depth narrative interviews.

RESULTS:

Median time to miscarriage resolution was 11 days (range 5–57) (ED) and 8 days (range 0–47) (ambulatory-only). We recorded a mean of 4.4±1.4 (ED) and 3.0±1.2 (ambulatory-only) separate care teams and a median of 13 (range 8–20) (ED) and 19 (range 8–22) (ambulatory-only) health system interactions. Patients seeking care in the ED were younger (28.3 vs 34.0, odds ratio [OR] 5.8, 95% CI 1.8–18.7), more likely to be of black race (28.3 vs 34.0, OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.1–10.0), uninsured or insured through Medicaid (16 vs 6, OR 6.8, 95% CI 2.1–22.5), and more likely to meet criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder when compared with ambulatory-only patients (10 vs 3, OR 6.0, 95% CI 1.5–23.4). Patients valued diagnostic clarity, timeliness, and individualized care. We found that ED patients reported a lack of clarity surrounding their diagnosis, inefficient care, and a mixed experience with health care provider sensitivity. In contrast, ambulatory-only patients described a streamlined and sensitive care experience.

CONCLUSION:

Patients seeking miscarriage care in the ED were more likely to be socioeconomically and psychosocially vulnerable and were less satisfied with their care compared with those seen in the ambulatory setting alone. Expedited evaluation of early pregnancy problems, with attention to clear communication and emotional sensitivity, may optimize the patient experience.

Miscarriage, or early pregnancy loss, is a common pregnancy complication, affecting approximately one in five pregnancies in the United States.1,2 Most miscarriages occur within the first trimester,1 and potentially before the usual time of the first prenatal appointment. Patients with concerns about a potential miscarriage, perhaps prompted by bleeding after a positive pregnancy test, present for care in emergency departments (EDs) at a rate of approximately 500,000 each year in the United States.3 The health care setting in which a patient receives the evaluation, diagnosis, and management of an early pregnancy complication such as miscarriage can influence her experience.4 People often suffer stress and grief with miscarriage,5 and clinicians caring for these patients have the opportunity to mitigate, rather than exacerbate, these negative outcomes.6,7

Patients may choose the ED over the ambulatory setting for a variety of reasons, including access and affordability, level of perceived clinical urgency, or clinician recommendation.8 When a nonviable pregnancy is diagnosed in early pregnancy, a patient may wait for natural tissue expulsion or select active management with a procedure or medication. The choice between expectant or active management often hinges on how important the timing of the resolution of the miscarriage is to the patient.9 We therefore sought to characterize the timeline from presentation to resolution in patients with miscarriage seeking care in emergency and ambulatory settings, as well as patient satisfaction with miscarriage management among these two groups.

METHODS

We performed a secondary analysis of a convergent exploratory mixed-methods study: the Miscarriage Management Choice Study, which examined factors influencing miscarriage treatment decision-making among clinically stable patients, the primary results of which have been described previously.9 For this secondary analysis, we divided the study sample into two groups: those who sought care in the ED and those whose care was limited to the ambulatory setting (ambulatory-only). The ED group included patients treated exclusively in the ED, as well as patients initially seeking care in the ED who were later seen in ambulatory clinics.

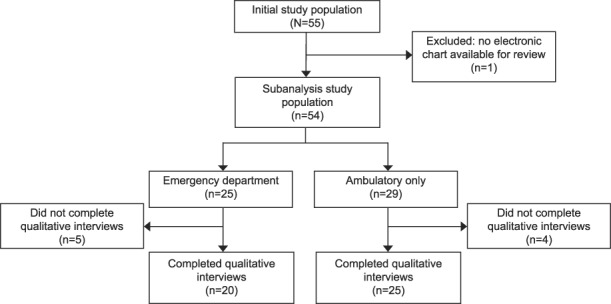

Fifty-five patients were recruited at the time of miscarriage diagnosis (after receiving a diagnosis, but before treatment) at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania from January 2014 to January 2015, from the hospital ED and outpatient clinical practices. Eligible participants were at least 18 year old and English-speaking, had ultrasound diagnosis of an anembryonic gestation or embryonic or fetal demise in the first trimester (5–12 completed weeks of gestation) confirmed by two clinicians, and were clinically stable with a closed cervical os. Participants completed validated baseline questionnaires that included demographics and psychometric measures, as well as open-ended, semi-structured interviews within 7 days of enrollment. We included 54 participants in this secondary analysis because one participant did not have electronic medical record data available for chart extraction (Fig. 1). All study activities were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pennsylvania.

Fig. 1. Study participant data flowchart.

Miller. Miscarriage Management Patient Experience. Obstet Gynecol 2019.

Forty-five interviews were required to reach thematic saturation around the outcome of interest (miscarriage management choice) from the primary study. Interview transcripts were entered into Nvivo 10, a qualitative software package, and coded using a modified grounded theory approach. Two researchers independently reviewed transcripts to create systematic coding categories; inter-coding reliability was assessed by comparing 20% of transcripts. The median kappa was 0.81 and agreement was 96%.

For this secondary analysis, quantitative outcomes included: time to miscarriage resolution (days from initial patient contact regarding early pregnancy concern at the study institution to final telephone or in-person health care system interaction during the observed pregnancy, including ultrasound or laboratory follow-up after medical management, or postoperative follow-up if indicated after surgical management); number of health care system interactions (defined as in-person or telephone encounters with a clinic or hospital service within the study institution, extracted from the electronic medical record); and number of care teams (distinct ambulatory clinics or hospital services). Data included in this analysis were limited to those recorded in the Penn Medicine electronic medical record.

We evaluated demographics and psychometric measures, including the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Perceived Stress Scale, and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian for all participants using standard descriptive statistics. For the baseline comparison of the ED and ambulatory-only groups, we used Pearson χ2 and Fisher exact tests to compare categorical scores, as well as t-tests and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables. Variables that differed with significance P<.10 were considered for a multivariable model using backwards selection. We used a Cox proportional-hazards model to describe the association of these predictors with the time to miscarriage resolution. All quantitative analyses were completed using Stata 14.2.

In our qualitative analysis, we first analyzed transcribed interview data across the entire cohort using a grounded theory approach along previously coded categories, or nodes, from the primary study. We selected all nodes relevant to patient experience and satisfaction (“accessing care,” “satisfaction and facilitation,” “provider interactions,” and “dissatisfaction and barriers”) and two researchers independently first identified and then agreed on themes of patient satisfaction that emerged from the transcript segments. We then stratified these data into ED and ambulatory-only groups to examine the differences in these themes.

RESULTS

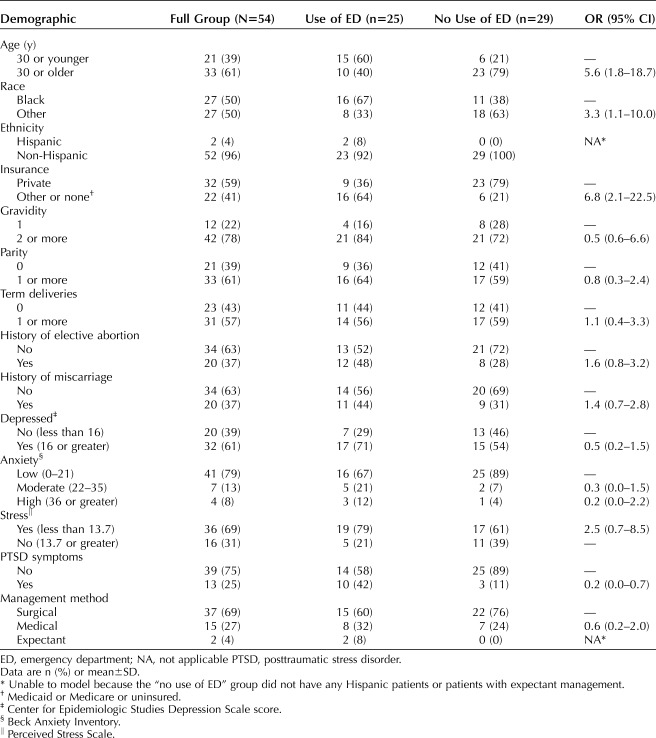

Our overall study population (N=54) was sociodemographically diverse. Most participants were parous (n=33, 61%). Patients seeking care in the ED were younger (28.3 vs 34.0, odds ratio [OR] 5.8, 95% CI 1.8–18.7), more likely to be of black race (16 vs 11, OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.1–10.0), and more likely to be without insurance or insured through Medicaid (16 vs 6, OR 6.8, 95% CI 2.1–22.5), compared with patients who did not seek care in the ED (Table 1). Additionally, patients using the ED were significantly more likely to meet criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (10 vs 3, OR 6.0, 95% CI 1.5–23.4; Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of Patients Presenting for Miscarriage Care by Emergency Department Use

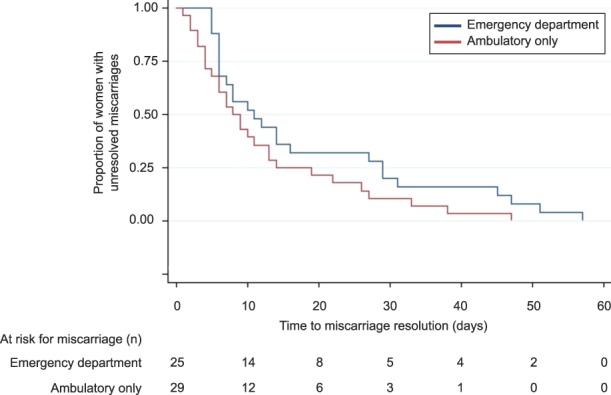

The ED and ambulatory-only patients had a median number of days to resolution of 11 (range 5–57) and 8 (range 0–47), respectively, after adjusting for age, race, and insurance (Fig. 2). During this period, we recorded a median of 13 (range 8–20) health care system interactions for ED patients and 19 (range 8–22) for ambulatory-only patients. Patients were exposed to an average of 4.4±1.4 (ED) and 3.0±1.2 (ambulatory-only) care teams, including obstetrics and gynecology general and specialty clinics, family medicine, internal medicine, radiology, ED, specialty consulting services, and more.

Fig. 2. Survival curves of time to miscarriage resolution for clinically stable patients seeking care in the emergency department or only in ambulatory settings.

Miller. Miscarriage Management Patient Experience. Obstet Gynecol 2019.

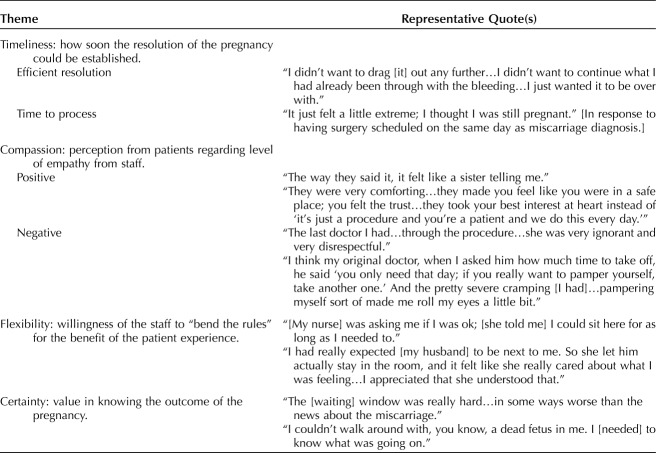

Across the entire cohort, qualitative analysis of satisfaction with miscarriage care revealed the following themes: the balance between certainty of diagnosis and timeliness of treatment, compassion, and individualized attention (Table 2). Participants valued being certain of the outcome of the pregnancy and found it difficult to wait for a final diagnosis. Although some participants valued a rapid resolution of the miscarriage, others needed time to process their diagnosis before initiating a treatment. Patients were sensitive to the level of compassion from their health care providers and had mixed experiences, some positive (“[I]t felt like a sister telling me”) and others negative (“[S]he was very ignorant and very disrespectful”). Similarly, patients valued health care providers' ability to tailor care to each individual, whether through emotional support or time to cope.

Table 2.

Aspects of Care Logistics Valued by Patients Undergoing Miscarriage Evaluation and Management in All Locations

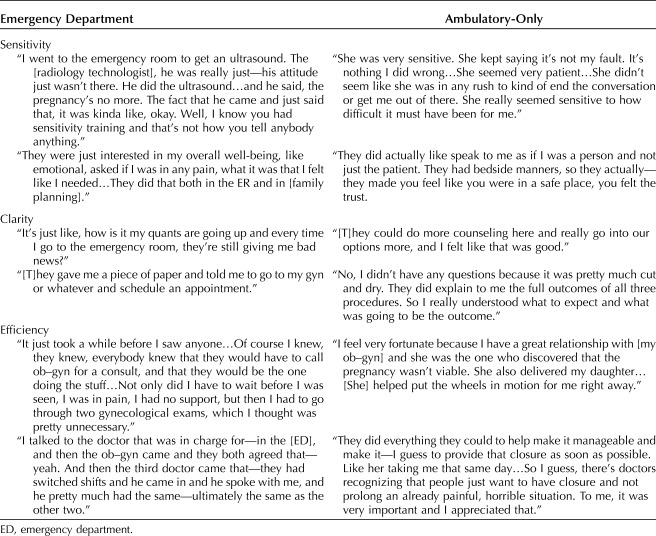

Our qualitative stratified analysis of ED and ambulatory-only locations of care revealed the following themes: clarity, efficiency, and sensitivity (Table 3). Ambulatory-only patients described a sense of clarity surrounding their diagnosis and treatment options, compared with patients who sought care in the ED. Similarly, the ambulatory-only patients observed a sense of efficiency in their care, describing the perceived benefit of same-day treatment options, whereas ED patients described multiple hand-offs and long wait times. Emergency department patients reported mixed experiences with health care provider sensitivity. One participant recounted her positive experience in the ED: “They were just interested in my overall well-being, like emotional, asked if I was in any pain, what it was that I felt like I needed.” Another described her negative interaction with a radiology technologist, saying, “His attitude just wasn't there.” The ambulatory-only group more consistently reported a sense of feeling cared for by their health care providers: “It was like they took your best interest at heart instead of, ‘it's just a procedure, and you're a patient, and we do this every day.’” Our analysis of these themes found that many ED patients reported a lack of clarity surrounding their diagnosis, inefficient care, and a mixed experience with health care provider sensitivity. In contrast, ambulatory-only patients often described a clearer, more streamlined, and sensitive care experience.

Table 3.

Aspects of Care Logistics Valued by Patients Undergoing Miscarriage Evaluation and Management, Stratified by Location

DISCUSSION

In this mixed-methods study, distinct profiles emerged between patients who sought miscarriage care through the ED and patients who sought care exclusively in the outpatient setting. Our observation that patients who presented to the ED were more likely to be young, black, and underinsured compared with patients who sought care only in ambulatory clinics is consistent with data from the general population in the United States: patients of lower socioeconomic status seek ED care more often than those of higher status.10 Our additional finding that ED patients were more likely to meet criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder reveals that this group was not only socioeconomically but also psychosocially vulnerable.

The ED patient experience was qualitatively associated with greater patient confusion and less satisfaction, similar to other qualitative studies of miscarriage care in the ED where patients reported poor communication, unfriendly environment, and a lack of emotional support.11,12 Participants who sought care in the ED had longer time to miscarriage resolution and a greater number of care teams involved in the miscarriage diagnosis and management. However, owing to the small sample size of this study and baseline differences in the study groups, which were not randomized, we were unable to test for significant differences in our study outcomes. Further study is needed to disentangle the causal relationship between socioeconomic and psychosocial status, use of the ED, and the patient miscarriage experience.

Strengths of our study include its mixed-methods approach, which offers a more in-depth understanding of the patient experience of miscarriage stratified by location of care. In addition, we used novel objective metrics with regard to the patient experience, including the quantification of care teams and health system interactions.

Our study has several limitations. First, the single-site design and English language requirement limit our generalizability; larger studies with geographic variability would be valuable to inform the best care for patients with concerning symptoms in early pregnancy. Second, several participants initiated pregnancy-related care outside of the study institution and self-referred to the study site before recruitment. Data from outside facilities were not part of the electronic medical record and therefore unavailable for extraction, which may have resulted in underestimates of the time to miscarriage resolution, number of health care interactions, and number of care teams. Third, psychosocial questionnaires were administered after the time of miscarriage diagnosis, which might have affected our ability to determine the directional relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder scores and ED exposure. However, given that the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian focuses on historical trauma, and that the groups did not differ on our measure of acute stress (Perceived Stress Scale), it is likely that this finding is related to chronic stress and was not a reaction to the miscarriage or their miscarriage care.

Miscarriage is associated with a negative psychological effect for many people, with clinically important symptoms of depression and anxiety in 22–41% of women in the first week after miscarriage,13 and the emotional experience of miscarriage can persist even after grief and depressive symptoms have resolved.14 Insufficient psychosocial support has been identified as a major gap in miscarriage care.15,16 Early pregnancy assessment units, which offer expedited evaluation of early pregnancy problems, with onsite ultrasound facilities and health care providers trained in both the clinical and emotional care of miscarriage, may optimize the patient experience.17 However, not all health systems include early pregnancy assessment units, and given that miscarriage treatment can be safely provided in EDs,18,19 this particularly vulnerable population undergoing miscarriage or possible miscarriage may warrant special attention. Previous research has demonstrated that the quality of miscarriage care improves when health care providers offer patients both medical information and emotional validation, and involve them in clinical decision-making,4,9,20–22 and caregivers can integrate these behaviors in the ED setting. Future studies should investigate whether specific interventions in the provision of miscarriage care, such as minimizing care teams, clarifying communication about diagnosis and treatment, and providing targeted emotional support, improve patients' experience.

Footnotes

Supported in part by R01 HD071920-01.

Financial Disclosure Andrea H. Roe, MD, MPH, received money paid to her institution for her role as the site PI for a Sebela Pharmaceuticals trial of an investigational copper IUD (VeraCept). The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

The authors thank C. Neill Epperson, MD, for her guidance with the psychosocial assessments.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal's requirements for authorship.

Peer reviews are available at http://links.lww.com/AOG/B618.

Figure.

No available caption

REFERENCES

- 1.Rossen LM, Ahrens KA, Branum AM. Trends in risk of pregnancy loss among US women, 1990–2011. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2018;32:19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X, Chen C, Wang L, Chen D, Guang W, French J. Conception, early pregnancy loss, and time to clinical pregnancy: a population-based prospective study. Fertil Steril 2003;79:577–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittels KA, Pelletier AJ, Brown DF, Camargo CA., Jr United States emergency department visits for vaginal bleeding during early pregnancy, 1993–2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:523.e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geller PA, Psaros C, Kornfield SL. Satisfaction with pregnancy loss aftercare: are women getting what they want? Arch Womens Ment Health 2010;13:111–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farren J, Mitchell-Jones N, Verbakel JY, Timmerman D, Jalmbrant M, Bourne T. The psychological impact of early pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod Update 2018;24:731–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellhouse C, Temple-Smith M, Watson S, Bilardi J. “The loss was traumatic…some healthcare providers added to that”: women's experiences of miscarriage. Women Birth 2019;32:137–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clement EG, Horvath S, McAllister A, Koelper NC, Sammel MD, Schreiber CA. The language of first-trimester nonviable pregnancy: patient-reported preferences and clarity. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:149–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, Long JA, Shannon R, Grande D. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schreiber CA, Chavez V, Whittaker PG, Ratcliffe SJ, Easley E, Barg FK. Treatment decisions at the time of miscarriage diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:1347–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang N, Stein J, Hsia RY, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Trends and characteristics of US emergency department visits, 1997–2007. JAMA 2010;304:664–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacWilliams K, Hughes J, Aston M, Field S, Moffatt FW. Understanding the experience of miscarriage in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs 2016;42:504–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baird S, Gagnon MD, deFiebre G, Briglia E, Crowder R, Prine L. Women's experiences with early pregnancy loss in the emergency room: a qualitative study. Sex Reprod Healthc 2018;16:113–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prettyman RJ, Cordle CJ, Cook GD. A three-month follow-up of psychological morbidity after early miscarriage. Br J Med Psychol 1993;66:363–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volgsten H, Jansson C, Svanberg AS, Darj E, Stavreus-Evers A. Longitudinal study of emotional experiences, grief and depressive symptoms in women and men after miscarriage. Midwifery 2018;64:23–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simmons RK, Singh G, Maconochie N, Doyle P, Green J. Experience of miscarriage in the UK: qualitative findings from the national women's health study. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:1934–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Punches BE, Johnson KD, Gillespie GL, Acquavita SA, Felblinger DM. A review of the management of loss of pregnancy in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs 2018;44:146–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsartsara E, Johnson MP. Women's experience of care at a specialised miscarriage unit: an interpretative phenomenological study. Clin Effect Nurs 2002;6:55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinariwala M, Quinley KE, Datner EM, Schreiber CA. Manual vacuum aspiration in the emergency department for management of early pregnancy failure. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:244–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schreiber CA, Creinin MD, Atrio J, Sonalkar S, Ratcliffe SJ, Barnhart KT. Mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of early pregnancy loss. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2161–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stratton K, Lloyd L. Hospital-based interventions at and following miscarriage: literature to inform a research-practice initiative. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2008;48:5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallace RR, Goodman S, Freedman LR, Dalton VK, Harris LH. Counseling women with early pregnancy failure: utilizing evidence, preserving preference. Patient Educ Couns 2010;81:454–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson A, Raine-Fenning N, Deb S, Campbell B, Vedhara K. Anxiety associated with diagnostic uncertainty in early pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017;50:247–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]