Abstract

A fusion between fibronectin 1 (FN1) and activin receptor 2A (ACVR2A) has been reported previously in isolated cases of the synovial chondromatosis. To analyse further and validate the findings, we performed FISH and demonstrated recurrent FN1-ACVR2A rearrangements in synovial chondromatosis (57%), and chondrosarcoma secondary to synovial chondromatosis (75%), showing that FN1 and/or AVCRA2 gene rearrangements do not distinguish between benign and malignant synovial chondromatosis. RNA sequencing revealed the presence of the FN1-ACVR2A fusion in several cases that were negative by FISH suggesting that the true prevalence of this fusion is potentially higher than 57%. In soft tissue chondromas, FN1 alterations were detected by FISH in 50% of cases but no ACVR2A alterations were identified. RNA sequencing identified a fusion involving FN1 and fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) in a case of soft tissue chondroma and FISH confirmed recurrent involvement of both FGFR1 and FGFR2. These fusions were present in a subset of soft tissue chondromas characterised by grungy calcification a feature reminiscent of phosphaturic mesenchymal tumour. However, unlike the latter, fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) mRNA expression was not elevated in soft tissue chondromas harbouring the FN1-FGFR1 fusion. The mutual exclusivity of ACVR2A rearrangements observed in synovial chondromatosis and FGFR1/2 in soft tissue chondromas suggests these represent separate entities. There have been no reports of malignant soft tissue chondromas, therefore differentiating these lesions will potentially alter clinical management by allowing soft tissue chondromas to be managed more conservatively.

Introduction

Synovial chondromatosis is a rare benign neoplasm associated with the synovium of a joint, tendon sheath or bursa. The presence of endochondral ossification in up to 50% of cases led to the synonym synovial osteochondromatosis (1). Any synovial joint can be involved, but it is commoner in larger joints including the knee, hip and elbow. The lesion presents most commonly over 40 years of age and there is a male predominance (2:1). Histologically, synovial chondromatosis is characterised by multiple hyaline cartilage nodules intimately related to the synovium. These may be embedded within the subsynovial tissue but may also lie in the synovial fluid either attached to the synovium or as ‘floating’ bodies.

The recent findings of FN1-ACVR2A and ACVR2A-FN1 in-frame fusions in a case of chondrosarcoma arising secondary to synovial chondromatosis and in one of seven cases of synovial chondromatosis (2), indicate that these lesions represent neoplasms, and that they rarely transform into secondary chondrosarcoma (3–6). However, the findings by Totoki et al., to the best of our knowledge, have not been yet validated. Since peripheral and central chondrosarcoma, chondroblastoma, phosphaturic mesenchymal tumour and extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma are among the potential differential diagnoses of synovium-related cartilage tumours, a reliable biomarker could aid significantly in the diagnostic accuracy of these lesions, particularly in needle core biopsies (7–10).

Soft tissue chondromas occur most commonly in the hands and feet and share histological features with synovial chondromatosis, hence it is one of the main differential diagnoses at these sites. Such lesions are considered to represent distinct entities (11–14) and soft tissue chondromas are by definition not related to the synovial lining. Nevertheless, even with the use of high-resolution radiological imaging in individual cases, it can be practically impossible to unequivocally exclude an association to a tendon-sheath, a bursa lining or synovium in the hands and feet. A specific biomarker would therefore aid in rendering the correct diagnosis (15).

In this study we set out to determine the prevalence of FN1 and ACVR2A gene rearrangements in a larger set of synovial chondromatosis, and secondary synovial chondrosarcoma, and to search for recurrent genetic alterations in soft tissue chondromas.

Materials and Methods

Cases were identified by searching the histopathology files at the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital (RNOH), UK, The Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital (RJAH) and the Basel Bone Tumour Reference Centre, Switzerland. The RNOH Biobank was approved by the National Research Ethics Committee of the Health Research Committee (reference 15/YH/0311: Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) project identifier: 18309). This specific project was approved by the National Research Ethics Committee approved UCL/UCLH Biobank Ethics Committee (specific project reference no. EC17.14). This biobank was licensed by the Human Tissue Authority under number 12073). Cases from the RJAH biobank were approved by the National Research Ethics Committee of the Health Research Committee (reference 17/YH/0108; Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) project identifier: 217446 and licensed by the HTA under number 12073). Ethical approval was also given by the Ethikkommission bei der Basel (reference 274/12).

All samples were diagnosed by specialist bone tumor pathologists (A.M.F., D.B., F.A., R.T.) according to the World Health Organization classification 2013 (13, 14). When available cases were correlated with clinical and imaging data. All samples were fixed in 10% formal saline, decalcified in EDTA or in nitric acid (5%) and processed in paraffin: tissue sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

FISH was carried out as described previously (16). In brief, sections were marked by a specialist histopathologist to target tumour-rich area, then deparaffinised and pre-treated by pressure-cooking following incubated in pepsin solution at 37°C for 50 minutes. Probes were added to tissue sections, denatured at 72°C and hybridised overnight at 37°C. Thereafter, the sections were washed and counterstained with 4', 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and mounted with coverslips.

Probes used for FISH included Agilent SureFISH custom-designed FN1 and ACVR2A, break-apart probes (Agilent, Cheshire, United Kingdom) (Table S1) and commercially available break-apart probes for FGF1 (CytoTest, Rockville, USA), FGFR1 (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany), FGFR2 (ZytoVision, Bremerhaven, Germany), and p16/CDKN2A (9p21) (Vysis, Abbott Molecular, Illinois USA). A positive result was obtained when at least 15% of the nuclei analysed reveal an aberrant signal on counting a minimum of 50 consecutive non-overlapping nuclei. Assessment of p16/CDKN2A FISH was undertaken as previously reported (17). Samples previously known to have rearrangement for FGFR1, FGF1 and FGFR2 by FISH and/or RNA sequencing were employed as controls.

RNAscope

The expression of FGF23 was assessed using the RNAscope™ assay (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Hayward, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sections were hybridised with a probe specific for FGF23 (Hs-FGF23, Cat. No. 557241), and for the endogenous control Ubiquitin C (Hs-UBC, Cat No. 310041). Hybridisation signals were amplified and visualised with RNAscope® 2.5 HD Detection Kit (Brown; Cat# 322360).

Quantitative real time PCR (qPCR)

RNA was extracted from FFPE sections using Ambion RecoverAll™ Total Nucleic Acid Isolation kit (Ambion,Austin, TX, USA) and reverse transcribed into cDNA with the Invitrogen™ SuperScript™ IV First-Strand Synthesis System with random hexamers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, Leicestershire, UK) according to manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was carried out using TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific): FGF23 (Cat. Hs00221003_m1), and the endogenous control G6PD (Cat. Hs00166169_m1). For analysis, the means of cycle thresholds (Ct) (n=2) were calculated. Based on the ΔCt between the gene and G6PD, the fold increase of gene expression was determined.

RNA extraction, library preparation, RNA sequencing

RNA sequencing was performed on cases that were retrieved from the operating theatres immediately after excision. A portion from each of the tumours was snap frozen. Frozen sections were cut and those that were at least 60% tumour-rich were homogenised in 1ml Trizol followed by extraction using the DirectZol purification kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality was assessed on the TapeStation 2200 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA): a RIN value of greater than 7 was obtained in each case. Poly(A) RNA was selected from 200ng total RNA using the NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA selection module (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA), and first-strand libraries constructed with the NEBNext Ultra Directional RNAseq library preparation kit (NEB) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were pooled and sequenced with 2x 101bp reads on a Hiseq 1500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) in rapid run mode. Fusion genes were identified from sequenced RNA with Fusion Catcher using default settings with Bowtie, BLAT and STAR used as the aligners and GRCh37 as the reference genome (18).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed in the Leica Bond 3 fully automated immunohistochemistry stainer (Leica Microsystems, Milton Keynes, UK) using the rabbit monoclonal histone H3F3 K36M mutant antibody (clone RM193; RevMAb Biosciences USA, San Francisco, CA, USA). Leica epitope retrieval 2 solution was used for 20 min. The antibody was diluted 1:400 (8).

Results

116 samples from the same number of patients were analysed by FISH for FN1 and ACVR2A gene rearrangement including 90 synovial chondromatoses, seven synovial chondrosarcomas and 19 soft tissue chondromas. Of these, 80 samples (69%) gave informative results (Table 1, Table S2). The percentage of break-apart samples in this study varied from 20 to 80% of the cells in the cases in which a rearrangement was found.

Table 1. Rearrangement of FN1 and ACVR2A.

| FN1 and ACVR2A rearrangement | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any FN1/ACVR2A rearrangement | Both FN1 and ACVR2A | FN1 only | ACVR2A only | No rearrangement | |

| Synovial chondromatosis (n=58) | 33 (56.9%) | 11 | 8 | 14 | 25 (43.1%) |

| Synovial chondrosarcoma (n=4) | 3 (75%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 (25%) |

| Soft tissue chondroma (n=18) | 9 (50%) | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 (50%) |

Synovial chondromatosis (n=90) showed an almost equal gender ratio (1.14M:1F) and presented between the ages of nine and 94 years of age (mean 48). The knee was the most frequently affected site (47 cases, 52%) followed by hand/wrist (11), hip (11), elbow (8), foot/ankle (8) and shoulder (5). Tumour size was available from 57 patients and ranged from 4 – 170 mm (mean 49 mm). Of the 40/89 patients whose tumours were resected and for whom follow-up information was available, 15 (38%) developed a local recurrence between 6 to 236 months (mean 45 months). Three of these 15 patients developed a second recurrence at 11, 12 and 90 months following surgery for their first relapse. The follow-up period of the 25 patients (63%) who did not develop a recurrence ranged from 1 to 57 months (mean 18 months).

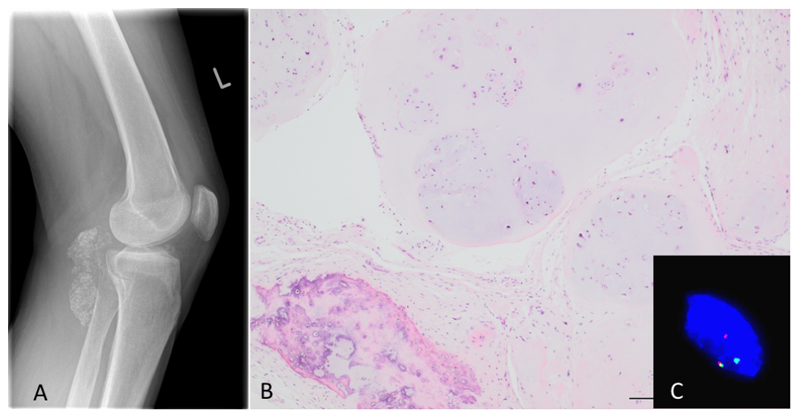

Histological assessment revealed multinodular tumours, connected to the synovium and composed of chondrocytes often arranged in clusters (clonal pattern of arrangement) with mild to moderate variation in cell size. The matrix frequently demonstrated enchondral ossification and/or calcification to a varying extent. No histological differences were detected in cases with or without gene rearrangement (Figure 1).

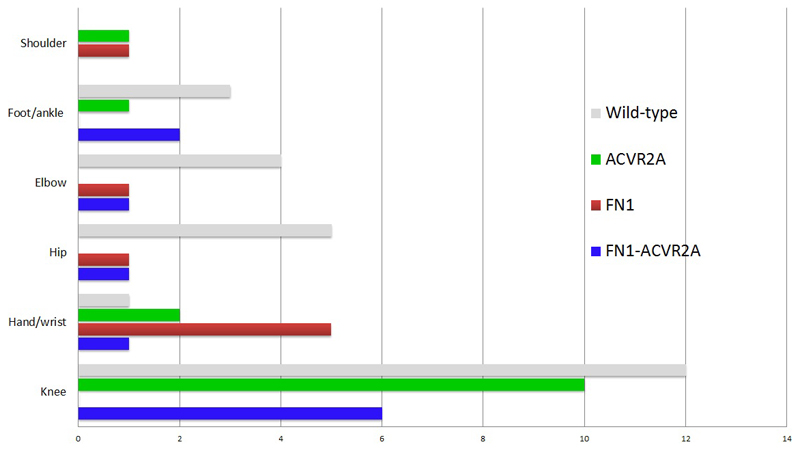

Of the 90 synovial chondromatosis, 58 gave informative FISH results for FN1 and/or ACVRA2 gene rearrangements (Table 1, Table S2), 57% (33/58) of which revealed a rearrangement involving either one or both genes. The genes involved in the rearrangements by anatomical site are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Synovial chondromatosis: Rearrangement type by site in the informative cases.

Synovial chondrosarcoma was diagnosed in seven patients from whose samples were available for analysis representing 7% (7/97) of the combined benign and malignant cohort. Four of the seven cases gave informative FISH results: 3 of these showed a FN1 and / or ACVRA2 gene rearrangement (Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of synovial chondrosarcoma cases.

| Case | Site | Grade | Primary/Local Recurrence | FISH | Clinical Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FN1 | ACVR2A | CDKN2A | |||||

| 1 | Hand | III | Primary | + | - | Homozygous deletionc | Lost to FU |

| 2 | Knee | II | Primarya | + | + | Homozygous deletion | Died of disease |

| 3 | Wrist | I | Local Recurrence | - | - | Disomic* | Disease free |

| 4 | Hip | III | Local Recurrence | NI | NI | NI | Died of disease |

| 5 | Elbow | II | Local Recurrenceb | NI | NI | NI | Lost to FU |

| 6 | Hip | II | Local Recurrenceb | NI | NI | NI | Lost to FU |

| 7 | Knee | III | Primary | - | + | Copy number gain | Disease free |

FISH performed on benign synovial chondromatosis; tissue for FISH was not available from the malignant synovial chondrosarcoma.

Histological evidence of benign disease abutting chondrosarcoma

Tissue at first diagnosis not available for review

Loss of 2 copies of CDKN2A in the presence of one or 2 centromeric signals

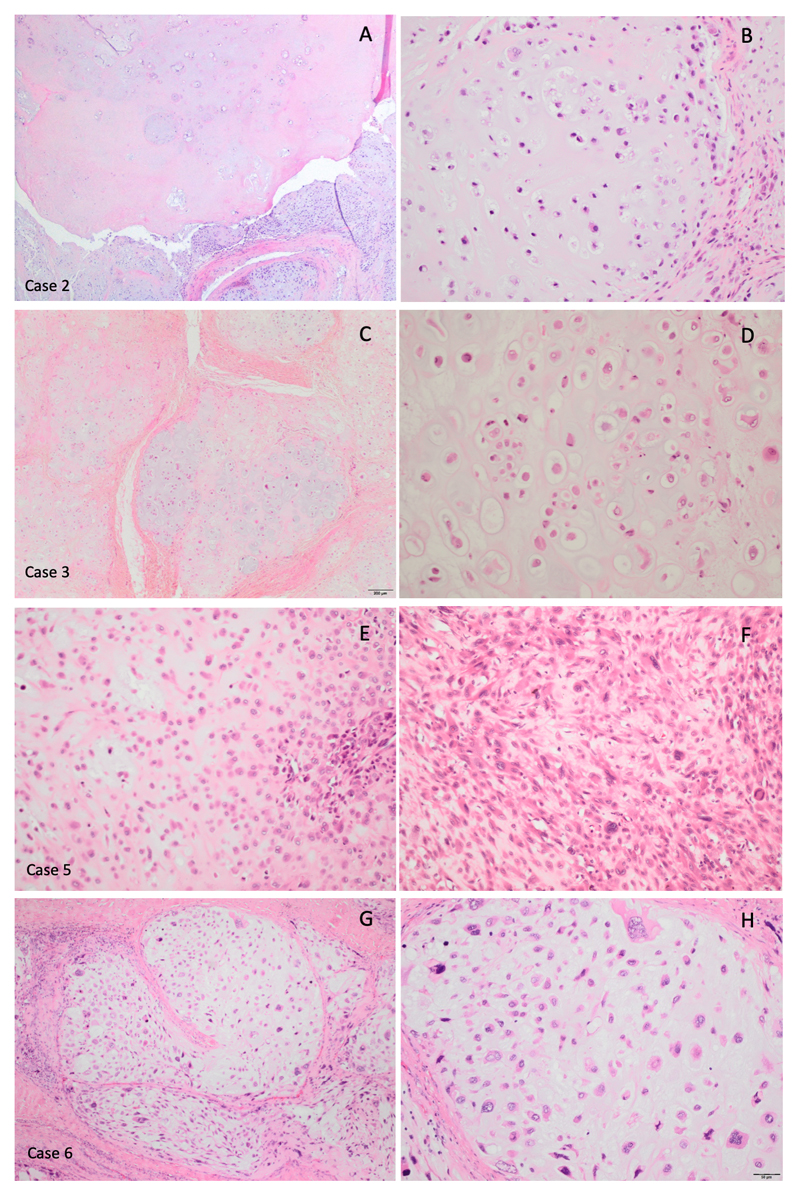

In three of the seven cases (cases 1, 2, and 7) synovial chondrosarcoma presented de novo, without a history of conventional synovial chondromatosis. The other (cases 3-6) had a history of benign synovial chondromatosis prior to the diagnosis of secondary chondrosarcoma (Figure 3; Table 2).

CDKN2A copy number in synovial chondromatosis and secondary chondrosarcoma

As CDKN2A copy number alterations are commonly seen in high grade conventional chondrosarcoma (17, 19), we investigated CDKN2A copy number by FISH (Table 2). Four of the seven cases were informative: two showed homozygous deletion, one copy number gain and, one (case 3), showed a disomic pattern in the synovial chondromatosis component, but the area showing features of chondrosarcoma was not available for analysis (Table 2). 18 cases of synovial chondromatoses revealed disomy for CNKN2A.

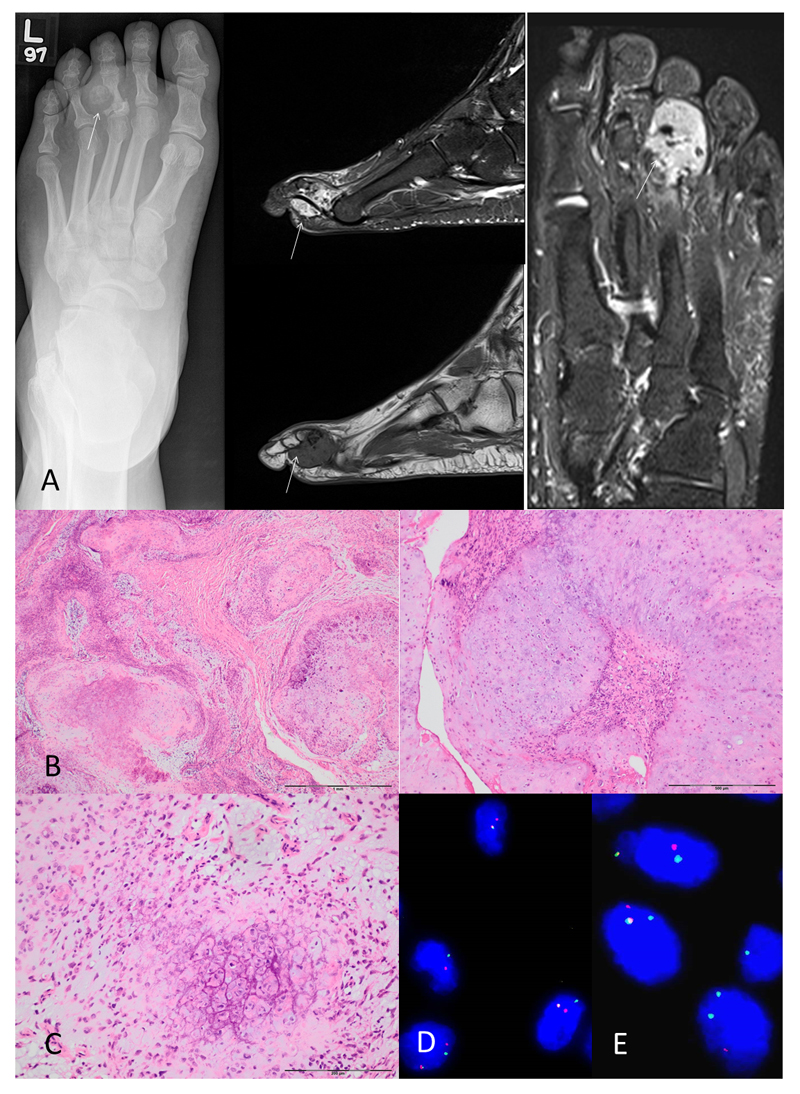

Soft tissue chondroma samples were obtained from 19 patients (10F:9M) ranging from 15 to 83 years of age at presentation (mean 56.5 years). Nine tumours were sited in the foot, nine in the hand/wrist and one in the forearm. Tumour size was available from 14 patients and ranged from 4 to 85 mm (mean 30 mm). Clinical follow up was available for 8 patients: one tumour was not resected and the other seven have not recurred at the time of analysis (follow up 0 - 19 months: mean six months).

Histologically, 12/19 soft tissue chondromas showed grungy matrix calcification, five of which exhibited chondroblastoma-like features (11) (Figure 4). Two other cases showed hyaline matrix without evidence of calcification, and the remaining five cases exhibited a predominantly myxoid cartilaginous matrix. Two of the cases with grungy calcification were associated with calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease.

Informative FISH results for FN1 and ACVR2A were obtained in 18/19 cases. Nine (50%) of the cases exhibited a FN1 gene rearrangement: all nine belonged to the group with grungy matrix calcification, three of which were classified as the chondroblastoma-like variant (Figure 4). None of the cases with a predominantly myxoid or hyaline cartilaginous matrix without calcification showed a FN1 gene rearrangement. ACVR2A rearrangements were not detected in any of the informative cases. Seven of the nine cases in which an FN1 gene rearrangement was detected were sited in the foot, the other two occurred in the hand.

In view of five cases showing features of chondroblastoma-like soft tissue chondroma, we analysed these samples for H3.3 K36M expression, an alteration seen in 98% of conventional chondroblastomas (8). None exhibited expression, thereby essentially excluding the possibility of H3F3A/B K36M mutation.

RNA sequencing of synovial chondromatosis/chondrosarcoma

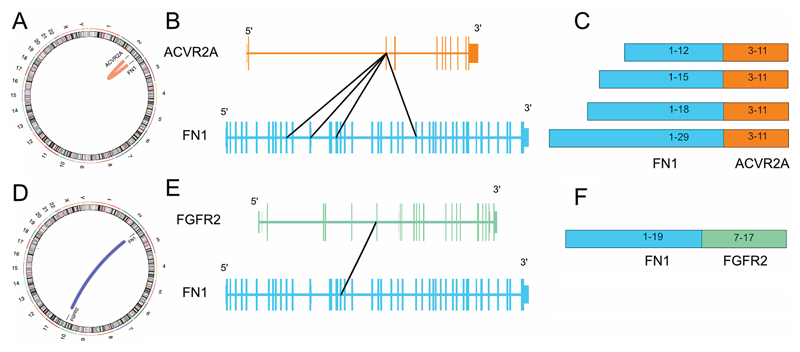

As ACVR2A and/or FN1 rearrangements were detected in 33/58 (57%) cases of synovial chondromatosis and in 9/18 (50%) soft tissue chondromas we next sought other rearrangements by RNA sequencing. A FN1 to ACVR2A fusion, likely as the result of a 70MB inversion of chromosome 2, was detected in all three cases of synovial chondromatosis, and the single case of secondary chondrosarcoma studied (the whole exome of which has been reported previously) (20) (Figure 5). As FN1 and AVCR2A are located on opposite genomic strands, the inversion resulted in a fusion in which both genes are in the same sense as each other and in every tumour in which the fusion was present, the predicted protein product was also in frame. The location of the breakpoint within FN1 was different in each tumour studied whereas the breakpoint in ACVR2A always occurred between the second and third exon. The chromosomal inversion therefore results in the entire protein-coding length of ACVR2A being appended to a truncated N-terminus of FN1. In all four cases, a transcript representing the reciprocal arrangement with ACVR2A at the 5’ end and FN1 at the 3’ end was also formed, and the resulting fusion protein was predicted to be in-frame (Table S3).

Previous studies of synovial chondromatosis have revealed a number of karyotypic aberrations including abnormalities of chromosome 6 and a (3;14) translocation (3). No direct evidence of these abnormalities was detected by RNA sequencing, however in the absence of a fusion gene being generated, RNA sequencing is not the modality of choice for investigating genomic structural variations.

A novel recurrent FN1-FGFR2 fusion was identified in cases of soft tissue chondroma

RNA sequencing of a soft tissue chondroma revealed a (2;10) translocation in which the 5’ end of FN1 was fused to Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2 (FGFR2) (Figure 5). Five different FN1-FGFR2 transcripts were detected in which only the FN1 segment was constant whereas there were different FGFR2 components. These different transcripts likely originated from a single genomic event and were resulted in alternative splicing of the pre-mRNA. Only one of the observed FN1-FGFR2 transcripts formed an in-frame fusion that could potentially result in a functional chimeric-protein. Additional fusions involving FN1 and genes on chromosome 10 were also seen, although they were detected at much lower expression levels compared to FN1-FGFR2. A summary of the genetic changes observed in soft tissue chondroma is presented in supplementary table 4.

Extended study of FGFR2 rearrangements

We confirmed the FGFR2 rearrangement detected on RNA sequencing using break-apart FISH probes. We next screened by FISH all cases of synovial chondromatosis, soft tissue chondroma and synovial chondrosarcoma, in which break-apart signals were not detected for either ACVR2A and/or FN1: cases where only one of these genes was detected by FISH were also analysed for the FGFR2 rearrangement. Of the 15 soft tissue chondroma cases tested, nine had a FN1 rearrangement, and six were wild-type for FN1 and ACVR2A. Remaining tissue for analysis was not available from three of the initial cohort tested (leaving 18 informative cases). Six of the nine cases with a FN1 gene rearrangement revealed additional FGFR2 rearrangements, indirectly confirming a FN1-FGFR2 fusion (Table S4).

FGFR2 gene rearrangements were not found in any case of synovial chondromatosis and synovial chondrosarcoma (Suppl Table S2).

Extended study of FGFR1 rearrangements

Finally, driven by our impression that soft tissue chondroma with grungy calcification shared histological similarities with phosphaturic mesenchymal tumours, known to harbour FN1-FGFR1, and FN1-FGF1 fusion genes (9), we speculated that both genes represented candidate fusion genes partners in soft tissue chondromas. We screened the cases of soft tissue chondromas where tissue was available material (n=15) for FGF1 and FGFR1 using break apart FISH probes: in three cases a FGFR1 gene rearrangement was detected. A FN1 gene rearrangement was also identified in these three cases by FISH thereby indirectly confirming a FN1-FGFR1 fusion in these cases. A FGF1 gene rearrangement was not observed in soft tissue chondromas. (Table S4). None of the cases of synovial chondromatosis (n=18) and synovial chondrosarcoma (n=1) where material was available exhibited either a FGF1 or FGFR1 gene rearrangement.

FGF23 mRNA levels in soft tissue chondromas

In view of an FN1-FGFR1 fusion gene being characteristic of phosphaturic mesenchymal tumour and typically expressing high levels of FGF23 we investigated the gene expression using RNA in situ hybridisation (RNAscope) and qPCR in eight soft tissue chondromas eight cases showing a FN1 break-apart signal of our series. None of the cases studied revealed significant levels of FGF23 by either test (Supplementary Figure 1).

Discussion

The current study demonstrates that at least 57% of synovial chondromatosis cases show a rearrangement involving FN1 and/or ACVR2A as detected by FISH. The true prevalence of cases harbouring these alterations is likely to be higher on the basis that only one of three synovial chondroma/chondromatosis cases that revealed a FN1-ACVR2A fusion gene by RNA sequencing demonstrated break-apart signals involving both genes. This discrepancy could be explained by the proximity of both genes on chromosome 2 and the limitation of designing appropriate FISH probes to detect such a paracentric inversion event. The one case, which was not informative for FN1 on FISH highlights the finding that possibly around 30% of cases are non-informative by FISH, demonstrating the need to improve tissue processing of calcified samples.

We have also confirmed the previously reported occurrence of a FN1 and ACVR2A gene rearrangement in the malignant variant of synovial chondromatosis (2). As 7% of our cohort was represented by synovial chondrosarcoma our data support previous reports that approximately 10% of synovial chondromatosis undergo malignant transformation (21, 22). The presence of a FN1-ACVR2 fusion did not distinguish between benign and malignant disease, but we showed that copy number alteration of CDKN2A appears to be a valuable predictor of malignancy, similarly to conventional cartilaginous tumours (17, 20) where copy number alterations of CDKN2A appear exclusively in chondrosarcomas.

We report for the first time that soft tissue chondromas harbour recurrent FN1-FGFR1 and FN1-FGFR2 gene fusions demonstrating conclusively that they represent neoplasms. The mutual exclusivity in detection of FGFR1 and FGFR2 fusion genes in soft tissue chondromas and ACVR2A fusions in synovial chondromatosis is supportive of them being distinct pathological entities (13, 14). The ability to distinguish reliably between these two entities is clinically relevant since soft tissue chondromas have a very low risk of local recurrence, and malignant transformation has not yet been described. As a consequence, they can be managed more conservatively than synovial chondromatosis.

Remarkably we found no difference in the histological appearance between synovial chondromatosis with and without FN1-ACVR2A rearrangements. In contrast, all the soft tissue chondromas harbouring FN1 alterations exhibited ‘grungy calcification’, a finding that in some cases is reminiscent of chondroblastomas, and led to the description of the chondroblastoma-like variant (11). Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumours typically also show this particular type of mineralisation and are characterised by FN1-FGFR1 fusions in 42% of cases (9), and it was this which prompted us to test our set of soft tissue chondromas for FGFR1 alterations. However, in contrast to phosphaturic mesenchymal tumours in which FGF23 expression is detected in approximately 95% of cases (23), we did not detect high levels of FGF23 mRNA expression in the soft tissue chondromas. Further study is needed to understand the distinct biological consequences of FN1-FGFR1 fusions in these tumour types and to explain the expression of FGF23 in PMT but not soft tissue chondroma. The presence of the same translocation in two tumours of mesenchymjal origin is suggestive that there exists some commonality in the pathogenesis of both entities. Explanations for the difference between the two tumour types could reside in different cells of origin in which the translocation occurred or in the epigenetic composition of the cells. Irrespective of the mechanism, we consider that it would be prudent to measure the serum phosphate levels in patients whose tumours harbour a FN1 fusion to ensure that any metabolic disturbances can be identified and addressed. Soft tissue chondromas without FN1 rearrangements exhibited a distinctive myxo-chondroid morphology and might represent a different entity. Indeed, it may be that these cases represent a result of a degenerative / reparative process.

In the single case of soft tissue chondroma that was subjected to RNA sequencing, there were several other gene fusions involving chromosome 10 resulting in predicted in-frame fusions with both FGFR2 and CRTAC1, in addition to the FN1-FGFR2 fusion. Fusions being formed with two genes in close proximity to each other on chromosome 10 cannot be explained by a simple single translocation and imply that further genomic rearrangements of the region have also occurred.

Of the four synovial chondromatosis/synovial chondrosarcoma cases subjected to RNA sequencing in our study, all revealed the presence of fusions involving FN1 and ACVR2A as previously demonstrated, thereby supporting the findings in the larger number of our cases probed by FISH. However, it is not possible to state which of these structurally altered genes drives tumour progression as both FN1-ACVR2A and ACVR2A-FN1 are predicted to be in-frame. Both FN1 and ACVR2A have been implicated in the development of neoplasia. ACVR2A encodes a receptor to Activin A, a protein that is part of the large family of transforming growth factor B genes and is involved in regulating multiple cellular processes. ACVR2A is commonly mutated in colorectal carcinoma and as well as hepatocellular and cholangiocellular (24, 25). FN1 is involved in a number of cell processes including adhesion and migration, the aberrant regulation of which could contribute to a neoplastic process. In addition to phosphaturic mesenchymal tumours discussed above, FN1 fusions with ALK have been described in gastrointestinal leiomyomas (26), and EGF fusions in calcifying aponeurotic fibromas (27).

In terms of explaining the mechanism of action of the fusion genes in synovial chondromatosis and soft tissue chondromas, it is noteworthy that FN1 is found as the 5’ fusion partner of both ACVR2A and FGFR2, and that the 3’ fusion partners have not been found with other 5’ partners. This implies that the FN1 component of the fusion plays an important biological role in the pathogenesis of these tumours and is not acting simply through driving the expression of the 3’ partner through an active promoter. The FN1-FGFR2 fusion identified by RNA sequencing in the soft tissue chondroma in our study reveals a similar domain structure of the resultant proteins to that found previously involving the FN1-FGFR1 fusion in phosphaturic mesenchymal tumour (9). In both cases, the N-terminal region of FN1 is attached to a truncated extracellular region of an FGF receptor leaving the transmembrane and intracellular domains intact. As previously hypothesised by Lee et al, the presence of the N-terminal region of FN1 may aid the dimerisation of the fused FGF receptor through the fibronectin domain leading to signal activation (9). This same mechanism may explain the action of the FN1-ACVR2A fusion, namely that FN1 may facilitate dimerisation of ACVR2A inducing activin signaling. In those cases in which FISH did not identify a fusion, it is possible that activation of the FGF pathway has been achieved through other mechanisms or that the disease is being driven by a mechanism that have yet to be discovered.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant to Dr Luis Casanova by The Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland, the RNOH NHS Trust R&D Office, and Skeletal Action Trust. The Bone Cancer Research Trust provided funding for biobanking to AMF and PC. AMF is a NIHR senior investigator and is supported by the National Institute for Health Research, UCLH Biomedical Research Centre and the UCL Experimental Cancer Centre. Maia Rocha is funded by the Tom Prince Cancer Trust. Nischalan Pillay is a Cancer Research UK-funded Clinician Scientist. We are grateful to the RNOH Musculoskeletal Pathology Biobank team for consenting patients and accessing samples, to the UCL Cancer Research UK Cancer Centre core Sequencing and Pathology facilities. We thank patients for participating in our research and the clinical teams involved in their care.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Walker EA, Murphey MD, Fetsch JF. Imaging characteristics of tenosynovial and bursal chondromatosis. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40:317–25. doi: 10.1007/s00256-010-1012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Totoki Y, Yoshida A, Hosoda F, et al. Unique mutation portraits and frequent COL2A1 gene alteration in chondrosarcoma. Genome Res. 2014;24:1411–20. doi: 10.1101/gr.160598.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buddingh EP, Krallman P, Neff JR, et al. Chromosome 6 abnormalities are recurrent in synovial chondromatosis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003;140:18–22. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(02)00636-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mertens F, Jonsson K, Willen H, et al. Chromosome rearrangements in synovial chondromatous lesions. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:251–4. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sciot R, Dal Cin P, Bellemans J, et al. Synovial chondromatosis: clonal chromosome changes provide further evidence for a neoplastic disorder. Virchows Arch. 1998;433:189–91. doi: 10.1007/s004280050235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tallini G, Dorfman H, Brys P, et al. Correlation between clinicopathological features and karyotype in 100 cartilaginous and chordoid tumours. A report from the Chromosomes and Morphology (CHAMP) Collaborative Study Group. J Pathol. 2002;196:194–203. doi: 10.1002/path.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amary MF, Bacsi K, Maggiani F, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent events in central chondrosarcoma and central and periosteal chondromas but not in other mesenchymal tumours. J Pathol. 2011;224:334–43. doi: 10.1002/path.2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amary MF, Berisha F, Mozela R, et al. The H3F3 K36M mutant antibody is a sensitive and specific marker for the diagnosis of chondroblastoma. Histopathology. 2016;69:121–7. doi: 10.1111/his.12945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JC, Su SY, Changou CA, et al. Characterization of FN1-FGFR1 and novel FN1-FGF1 fusion genes in a large series of phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:1335–46. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Motoi T, Khanin R, et al. Identification of a novel, recurrent HEY1-NCOA2 fusion in mesenchymal chondrosarcoma based on a genome-wide screen of exon-level expression data. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:127–39. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cates JM, Rosenberg AE, O'Connell JX, Nielsen GP. Chondroblastoma-like chondroma of soft tissue: an underrecognized variant and its differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:661–6. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200105000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lichtenstein L, Goldman RL. Cartilage Tumors in Soft Tissues, Particularly in the Hand and Foot. Cancer. 1964;17:1203–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196409)17:9<1203::aid-cncr2820170917>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sciot R, Bridge JA. Synovial chondromatosis. In: Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PC, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2013. p. 261. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg AE, Mandahl N. Soft-tissue chondroma. In: Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PC, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2013. pp. 160–1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damato S, Alorjani M, Bonar F, et al. IDH1 mutations are not found in cartilaginous tumours other than central and periosteal chondrosarcomas and enchondromas. Histopathology. 2012;60:363–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amary MF, Berisha F, Bernardi Fdel C, et al. Detection of SS18-SSX fusion transcripts in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded neoplasms: analysis of conventional RT-PCR, qRT-PCR and dual color FISH as diagnostic tools for synovial sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:482–96. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amary MF, Ye H, Forbes G, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutations (IDH1) and p16/CDKN2A copy number change in conventional chondrosarcomas. Virchows Arch. 2015;466:217–22. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1685-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicorici D, Satalan M, Edgren H, et al. FusionCatcher - a tool for finding somatic fusion genes in paired-end RNA-sequencing data. bioRxiv. 2014 011650. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schrage YM, Lam S, Jochemsen AG, et al. Central chondrosarcoma progression is associated with pRb pathway alterations: CDK4 down-regulation and p16 overexpression inhibit cell growth in vitro. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:2843–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00406.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarpey PS, Behjati S, Cooke SL, et al. Frequent mutation of the major cartilage collagen gene COL2A1 in chondrosarcoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:923–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertoni F, Unni KK, Beabout JW, Sim FH. Chondrosarcomas of the synovium. Cancer. 1991;67:155–62. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910101)67:1<155::aid-cncr2820670127>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biazzo A, Confalonieri N. Synovial chondrosarcoma. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:280. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.06.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carter JM, Caron BL, Dogan A, Folpe AL. A novel chromogenic in situ hybridization assay for FGF23 mRNA in phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:75–83. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuza K, Nagahashi M, Watanabe S, Takabe K, Wakai T. Hypermutation and microsatellite instability in gastrointestinal cancers. Oncotarget. 2017;8:112103–15. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang A, Wu L, Lin J, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals the origin and evolution of hepato-cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Commun. 2018;9 doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03276-y. 894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panagopoulos I, Gorunova L, Lund-Iversen M, et al. Recurrent fusion of the genes FN1 and ALK in gastrointestinal leiomyomas. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:1415–23. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puls F, Hofvander J, Magnusson L, et al. FN1-EGF gene fusions are recurrent in calcifying aponeurotic fibroma. J Pathol. 2016;238:502–7. doi: 10.1002/path.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.