Abstract

Sea scorpions (Eurypterida, Chelicerata) of the Lower Devonian (~400 Mya) lived as large, aquatic predators. The structure of modern chelicerate eyes is very different from that of mandibulate compound eyes [Mandibulata: Crustacea and Tracheata (Hexapoda, such as insects, and Myriapoda)]. Here we show that the visual system of Lower Devonian (~400 Mya) eurypterids closely matches that of xiphosurans (Xiphosura, Chelicerata). Modern representatives of this group, the horseshoe crabs (Limulidae), have cuticular lens cylinders and usually also an eccentric cell in their sensory apparatus. This strongly suggests that the xiphosuran/eurypterid compound eye is a plesiomorphic structure with respect to the Chelicerata, and probably ancestral to that of Euchelicerata, including Eurypterida, Arachnida and Xiphosura. This is supported by the fact that some Palaeozoic scorpions also possessed compound eyes similar to those of eurypterids. Accordingly, edge enhancement (lateral inhibition), organised by the eccentric cell, most useful in scattered light-conditions, may be a very old mechanism, while the single-lens system of arachnids is possibly an adaptation to a terrestrial life-style.

Subject terms: Palaeontology, Taxonomy, Visual system, Animal physiology, Marine biology

Introduction

Eurypterids, popularly known as sea scorpions, possess conspicuously large compound eyes. Indeed, Jaekelopterus rhenaniae (Jaekel, 1914) (Fig. 1a) from the Early Devonian of Germany was perhaps the largest aquatic arthropod ever with a body length approximating 2.5 meters1. A fully grown Jaekelopterus (Fig. 1a) was a giant even when compared to other large arthropods such as the well-known Cambrian Anomalocaris (~1 m long2), or the meganeurid griffenflies (~75 cm wing span) of the Permo-Carboniferous1,3,4, or Hibbertopterus, another eurypterid, which probably was about 1.60 m long5. It was only the Late Carboniferous giant millipede Arthropleura, which perhaps attained comparable proportions6.

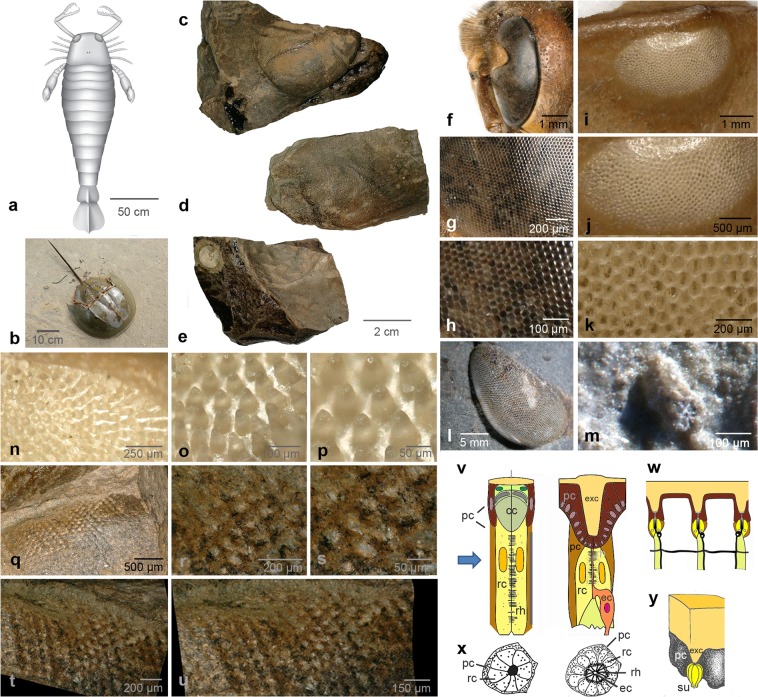

Figure 1.

Examples of eurypterid and limulid morphology and comparison of Jaekelopterus lateral eyes to other arthropod compound eyes. (a) Reconstruction of Jaekelopterus rhenaniae (Jaekel, 1914) (modified from Braddy et al. 2008; drawing by S. Powell, with permission. (b) Tachypleus gigas (Müller, 1785), Limulida [© Subham Chatterjee/CC BY-SA 3.0 (via Wikimedia Commons)]. (c–e) Examples of specimens (c: GIK 186, d: GIK 188, e: GIK 190). (f–h) Compound eye of a hornet Vespa crabro germana Christ, 1791. (i–k) Compound eye of Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda (Latreille, 1802), Limulida, exuviae. (l) Compound eye of the trilobite Pricyclopyge binodosa (Salter, 1859), Ordovician, Šárka formation, Czech Republic. (m) Ommatidium of the trilobite Schmidtiellus reetae Bergström 1973, base of the Lower Cambrian, Lükati Fm., Estonia. (n–p) Cones (lens cylinders) of the internal side of the compound eye of C. rotundicauda (exuvia). (q) Impressions of the exocones in Jaekelopterus rhenaniae (Jaekel, 1914), (GIK 186a). (r–t) Exocones of J. rhenaniae (GIK 186), note the regular arrangement compared to (i). (u) Schematic drawing of the ommatidium of an aquatic mandibulate (crustacean), and of the ommatidium of a limulid. (w) schematic drawing of several ommatidia of a limulide. (x) Schematic drawing of crossections of (v), the limulide after73. (y) Visual unit of a limulide (redrawn and changed after51). cc, crystalline cone; ec, eccentric cell; exc exocone; l, lens; p, pigment; pc, pigment cells; rc, receptor cells; rh, rhabdom; su sensory unit.

Eurypterids appeared during the Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian, 467.3 Mya7), but probably originated earlier, and having been already severely affected by the late Devonian environmental changes, they vanished before the end of the Permian (252 Mya)8), when up to 95% of all marine species died out9,10.

Most eurypterids were predators, as indicated by morphological attributes such as gnathobasic coxae. Some species were equipped with spinose legs and/or highly effective grasping chelicerae or claws. In J. rhenaniae these claws reached an impressive size of 46 cm1. Forms lacking such specialized morphology, probably nectobenthic, walking on or swimming close to the sea floor. As opportunistic feeders, they dug in the mud as do modern horseshoe crabs, grabbing and shredding whatever they found to eat11. While earlier eurypterids were marine, among the later, younger forms some were living in brackish or even fresh water (e.g.12–15). In addition to book gills comparable to those of modern Limulus, ancillary resiratory organs known as Kiemenplatten16 may have allowed the animals to make short visits to the land17, but work currently in progress suggest that these may have aided gas exchange in aquatic settings18. Some eurypterids were ambush predators, e.g., the large pterygotid Acutiramus, based on analyses of functional morphology of its chelicerae19 and its visual capabilities20. On the other hand, the ecological requirements of eurypterids were apparently quite diverse and results based on analysis of a particular taxon (or species) may not apply to other clades21,22.

At least some eurypterids were effective predators, and most of such predators are, and were, equipped with an excellent visual system. Not much, however, has so far been understood about eurypterid eyes. In systematic terms, Tollerton23 defined nine different shapes of eurypterid eyes, ranging from small lunar shaped examples to domed ovoid types, of which some even had a frontally overlapping visual field (e.g., J. rhenaniae). The latter is typical for predators, allowing stereoscopic vision, which is imperative for the estimation of distances, volumes etc. Assuming that there is an optimal trade-off in compound eyes working at threshold perception between maximal acuity (demanding a high number of facets) and a high sensitivity (requiring large lenses) it has been possible to assign different eurypterid species to their light-ecological environments20–22. The results show a transition in lateral eye structure in eurypterids as a whole, and furthermore reflect a niche differentiation in co-occurring (Rhenish) eurypterids, thus avoiding competition for food in their marginal to delta plain habitats22.

Nothing, however, has been documented about the internal structure of the eurypterid visual system, which might tell us about function and phylogenetic context.

Systematic Position of Eurypterida Burmeister, 1843

Soon after the first eurypterid fossils were described, they were regarded as close relatives of xiphosurans24 and the two groups were united in the taxon Merostomata Dana, 185225. Traditionally, the major arthropod clade Chelicerata Heymons, 1901 has been divided into the aquatic Merostomata (Xiphosura + Eurypterida) and the terrestrial Arachnida, but today, most arthropod workers consider Merostomata a paraphyletic grade of aquatic chelicerates26–28 and the term is no longer used. On the other hand, eurypterids have long been considered as closely allied to arachnids27–29, and scorpions have been regarded in some analyses as the closest relatives of eurypterids30–32. For further morphological evidence of the close relationship between scorpions and eurypterids, a recent study of cuticle microstructure found similarities between scorpions, eurypterids, and horseshoe crabs33. Versluys and Demoll34 emphasized the similar body segmentation in scorpions and eurypterids, and Dunlop & Selden29 later pointed out that the 5-segmented postabdomen can be regarded as a synapomorphic trait shared by scorpions and eurypterids. Kamenz et al.35 interpreted organs found in exceptionally well-preserved specimens of Eurypterus as structures equivalent to spermatophore-producing organs in the genital tracts of some modern arachnids. In concert with the supposed mating behaviour of eurypterids via transfer of a spermatophore36, these findings offered support for a Eurypterida + Arachnida clade, for which the name Sclerophorata has been proposed34. Following the Sclerophorata concept, Lamsdell37 again supported the view that the eurypterids are more closely related to arachnids than to xiphosurans, which would necessitate their removal from Merostomata sensu Woodward24 and ultimately renders the latter taxon a junior synonym of Xiphosura. However, the question of whether eurypterids are more closely allied to arachnids or to xiphosurans is still far from settled (see discussion in11). Recent phylogenomic analyses of chelicerate relationships even strengthen the concept that the Arachnida are polyphyletic, and also a nested placement of Xiphosura within Arachnida (38 and references therein). Thus, understanding the internal structure and function of eurypterid eyes not only sheds light on the origins of chelicerate eyes, but may also offer further insights into the ecology, behaviour, and relationships of these extinct invertebrates.

The Eyes of Mandibulates, Arachnids and Horseshoe Crabs

The oldest compound eye known at present, is that of the lower Cambrian trilobite Schmidtiellus reetae Bergström, 1973 Figs. 1m, 2e), which has a typical apposition compound eye (Fig. 1f–h,m,v,x), not dissimilar to that of modern bees, dragonflies and many crustaceans39, and there is strong evidence for a common origin of insect and crustacean eyes40–42. These eyes consist of repeated identical visual units, the ommatidia, appearing externally as facets. Each ommatidium contains ~8 receptor cells, grouped around a central axis, the rhabdom. The rhabdom is part of the sensory cells, and contains the visual pigments. With light energy these are changed in their sterical configuration, and a small electrical signal is sent to the nervous system. The incident light is focused onto the tip of this rhabdom by a dioptric apparatus, consisting of a cuticular lens and a cellular crystalline cone, while in modern aquatic visual systems the latter typically takes over the function of refraction. All ommatidia are isolated optically from each other by screening pigment cells, and thus over the whole compound eye a mosaic-like image is formed. In the ancient system of the trilobite S. reetae, however, a lens and a crystalline cone are not very evident, and the sensory unit sits in a kind of basket, isolating the ommatidia against each other. Principally, among other factors, the acuity of vision depends on the number of facets, and the apposition eye is typically found in animals active when the light is bright43. Adaptations of such eyes to dimmer light conditions, systems such as superposition eyes, are not known before the Devonian44.

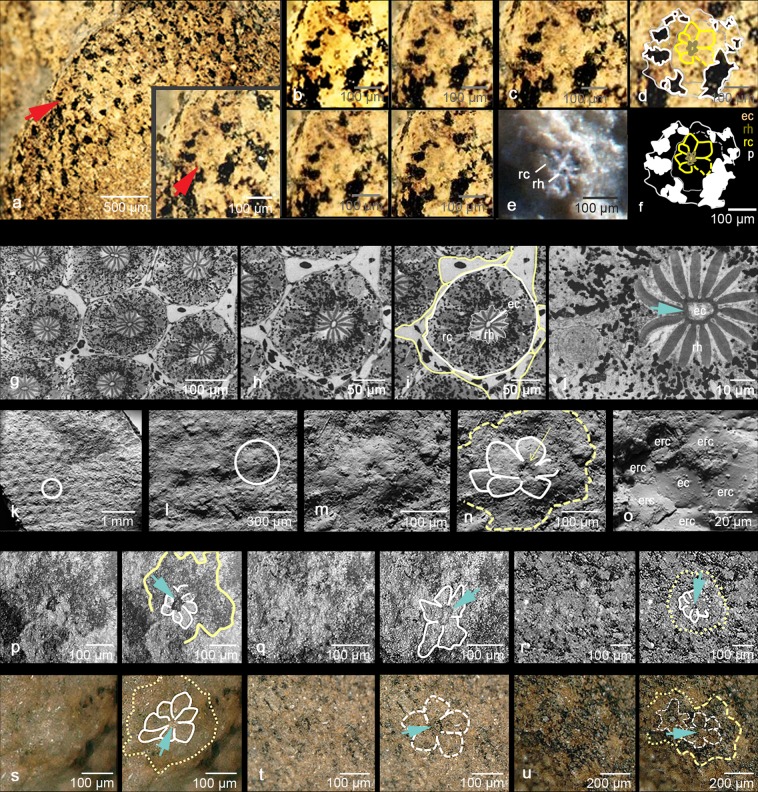

Figure 2.

The ommatidium of Jaekelopterus rhenaniae (Jaekel, 1914). (a–d) The specimen, where the first ommatidium was discovered (red arrow), d: brown: rhabdom with eccentric cell dendrite in the centre, yellow: receptor cells, black spots: possibly screening pigments. (b) shows the rosette of the ommatidium in crossection under different contrasts. Note the bright spot of the presumed eccentric cell in the centre of the rhabdom. (c,d,f) Rosette of (a) magnified, and its schematic drawings. (e) Ommatidium of the trilobite Schmidtiellus reetae Bergström 1973 and its homogenous rhabdom. (g–j) Cross sections of ommatidia of Limulus (quoted from69 Figs. 2 and 3)), [white circle indicates the rosette, yellow circle the pigmental periphery, blue arrow the situation of the rhabdom, (j). (k–o) SEM of the compound eye of Jaekelopterus rhenaniae (Jaekel, 1914), total aspect (k) to one rosette (m–o) and individual rhabdom (o), [white circle indicates the rosette of receptor cells, yellow circle the pigmental periphery, yellow arrow the situation of the rhabdom, (n)]. (p–u) Different sensory rosettes of J. rhenaniae (Jaekel, 1914) and their interpretative drawings. Note the bright patch in the centre of the rhabdom, comparable to (a–d), and (g–j). (q–r) In black and white to show contrasts different from (s–u) in colour, [white circle indicates the rosette of receptor cells, yellow circle the pigmental periphery, blue arrow the situation of the rhabdom]. p, q GIK 188; (r–t), w, u GIK 190; ec eccentric cell; exc exocone, erc, element of receptor cell forming the outer part of the rhabdom; p, pigment cells; rc, receptor cells; rh, rhabdom; su sensory unit. Blue arrows indicate the dark rhabdomeric ring with the relics of the presumed dendrite of the eccentric cell inside.

Differences in the ontogenetic development of the compound eyes in xiphosurans and Pancrustacea/Tetraconata (crustaceans and hexapods including insects) exclude a common origin for both systems; they evolved convergently45. The xiphosurans such as Limulus are well known as descendants of a bradytelic lineage (evolving at a rate slower than the standard), exhibiting only little morphologic change since the Mesozoic46 and with roots that can be traced back in time at least to the Early Ordovician47. Even, if horseshoe crabs have changed their ecological requirements numerous times in the course of their evolution48, the extant species still seem to retain an ancient visual system. Ommatidial facets of living xiphosurans (Figs. 1b,i–k,n–u,v–y, 2g–j), namely Limulus, are up to 320 microns49 in diameter (among the largest known in the animal kingdom49), make the eye a superb light collector49, and shows characteristic differences to those of Tetraconata. The dioptric apparatus of the xiphosurans is formed by a cuticular lens cylinder50, while in Tetraconata a cuticular lens focuses the light through a cellular crystalline cone. The latter, in water, takes over, by physical reasons, the function of refraction. The number of receptor cells per ommatidium in Limulus varies from 4 to 20, (8 to 15) (51,52). As in many apposition compound eyes of tetraconates the rhabdomeres of the receptor cells are fused in the centre. In xiphosurans the retinular cells are electrically coupled to one another, especially by the so-called eccentric cell, which sits at the base of the sensory unit. This configuration is not found in the tetraconate system. The rhabdom, which is built by microvillar arrays along the central part of the receptor cells appears like an asterisk with a central ring occupied by the dendrite of the eccentric cell when viewed along the light path (ref. 52, p. 112). The eccentric cell takes over first processings among the receptor cells, and coupled to its neighbours it contributes to processes such as lateral inhibition53, enhancing edges and boundaries in the perceived visual image. This is beneficial especially in the scattered light-conditions of the water column. In contrast, the fused tetraconate rhabdom is uniform (Figs. 1m,x, 2e). The visual units of both, Tetraconata and xiphosurans, are embraced by pigment cells, screening them against each other and isolating them optically. Thus the mode of the dioptric apparatus and the structure of the rhabdom is the crucial point here for distinguishing the eurypterid ommatidium, and to confirm that it is an ancient chelicerate system and similar to those of xiphosurans, rather than a tetraconate system, or even of a totally different structure.

In spiders and their terrestrial relatives (e. g., phalangids and extant scorpions) the eyes are not compound eyes but all are of the simple corneal type (ref. 54, p. 527, for a detailed review see55). True spiders (Araneae) usually have 6–8 eyes, the so-called principal eyes (main eyes), homologous to the mandibulate median eyes and looking forward, being adapted to look at objects nearby; the lateral eyes (secondary eyes) cover the more peripheral fields of view. Based on the rhabdomeric pattern of the retina Paulus56 supposed that the scorpion eye has evolved from the facet eye by fusion of corneae, and interpreted the secondary eyes of Arachnida as dispersed and reduced former compound eyes (ref. 56, p. 311–313). This idea has been taken up to be investigated with modern molecular methods by Morehouse57. Miether & Dunlop55 documented compound lateral eyes of fossil scorpions and other arachnids. The Triassic (about 220 Mya) scorpions Mesophonus opisthophthalmus Wills, 1947 and Mesophonus perornatus Wills, 1910 bear at least 28 and 35 facets respectively, the Late Carboniferous (~309 Mya) scorpion Kronoscorpio danielsi Petrunkevitch, 1913 (~309 Mya) shows 25–29 individual facets. Also revealing is a specimen from the Lower Devonian Rhynie Chert of Scotland (~410 Mya, Palaeocharinus sp.), which belongs to the Trigonotarbida, an extinct group of spider-like arachnids, and possibly closely related to scorpions58. It shows three larger lenses, and a horizontal row between them of 10–11 smaller facets - a system which may indicate a transition from the compound to a single-lens eye. Thus the single-lens eyes of modern arachnids including scorpions appear to be highly derived systems, their ancestral structure, however, remains unclear.

Arthropodean eyes of Cambrian age (541–485 Mya, Palaeozoic) are of the compound type59,60 and were found e.g. in radiodonts and in great appendage or megacheiran arthropods. While in a single radiodont eye at least 16,000 hexagonally packed facets may be observed59, the pattern of the fossil scorpion eyes is much less regular and the single less numerous. The arrangement resembles those of modern xiphosurans. One may keep in mind that the most optimal packing of numerous originally round elements as a matter of principle is that of a hexagonal arrangement, as evident in honeycombs for example. Thus a hexagonal pattern would be expected in high resolution compound eyes with many facets, while for less acute compound eyes the pattern may become more or less irregular, as can be observed in almost all smaller compound or aggregate eyes. Thus it is not the external pattern that may be crucial for phylogenetic discussion, because it is so constructed for functional reasons. This functional pattern from an evolutionary point of view can be developed very quickly, as the now classic model by Nilsson & Pelger61 shows. It is the internal structure, namely the organisation of the dioptric and sensory apparatus that is relevant here, or the organisation of the optical lobes (for this see60). In principle, under each facet of a compound eye any kind of structure might reside, any mode of ommatidium, a small retina, a singular receptor cell or anything else. The phylogenetic context, however, gives certain constraints.

Likewise, it has been discussed that the myriapod ocellar single-lens eyes had arisen by disintegration of former compound eyes62. Each unit consists of a big lens floored by up to several hundreds of cells63,64. Harzsch and colleagues showed that during eye growth in Myriapoda new elements are added to the side of the eye field, extending rows of previously generated optical units, which is suggested to contradict the above assumption64. Only one group of Chilopoda, the Scutigeromorpha, shows hexagonal facets and their ommatidia possess cone cells65, similar to those of Pancrustacea/Tetraconata (hexapods + crustaceans). Their compound eyes, however, must be considered as secondarily reorganized lateral myriapodan ocelli62.

Results

To decide to which type the eyes of eurypterids belong, one has to consider two questions. The first concerns the structure of the dioptric apparatus. If the eye is constructed similarly to that of an aquatic tetraconate as in marine crustaceans, one would expect a distal thin cuticle, not functioning as a lens, which would be typical just for terrestrial arthropods. Instead one might expect a distinct crystalline cone forming the dioptric apparatus. In contrast, in the xiphosuran compound eye, less ordered than a typical tetraconate compound eye, the dioptric apparatus consists of cuticular, cone-shaped lens-cylinders (exocones), which form a pattern of separated domes, visible if the cuticle is removed from the receptors (Fig. 1n–p).

Exocones in eurypterid eyes

Figure 1r–u clearly shows the relicts of a eurypterid visual surface, appearing much more regular than that of a xiphosuran (Fig. 1j,k,n–p). The units are regularly arranged in a squared pattern. Specimen GIK 186 clearly shows the lower surface of the cuticle covering the eye (Fig. 1c,r–u), exposing clear exocones, very similar to those of xiphosurans (Fig. 1n–p). In the detached part of the fossil they are indicated by tapering cavities (GIK 186a, Fig. 1q). These exocones, like their negatives, remain quite separated from each other, rather than being densely packed as are the facets of a honey bee, hornet, a dragon fly or of many trilobites (Fig. 1f–h,l,m). Our results clearly show that the typical shape of exocones in the eurypterid eye is similar to those of Limulus (Fig. 1n–u) and these exocones may have functioned in the same way as lens cylinders.

Mode of preservation and receptor system

The second question that has to be considered is the construction of the receptor system. This is a much more difficult problem, because the relics of soft (labile) tissues, such as nervous or sensory cells, are very rarely found in the fossil record, and then only as a result of special kinds of preservation, such as phosphatisation, or at particular Konservat-Lagerstätten sensu Seilacher et al.66. Such exceptional preservation of soft tissue has not hitherto been known from eurypterid fossils. The grain size of the host sediment, in most cases a clayey siltstone, lies between silt (0.002–0.063 mm) and clay (<0.002 mm), in the range that would preserve the traces of cellular structures very well because the size of the receptor cells is larger than the grain-size. There is another adverse effect: In many eurypterid fossils no facets can be observed, the eyes appear as covered by relicts of a pellucid membrane, probably the cuticle21. Thirdly, most eurypterid fossils are moults13 and it is only in dead individuals (carcasses) that preservation of the internal structure of fossil eyes can be expected.

Sublensar rosettes

Only a few examples of microstructures of visual systems in fossils have been reported so far39,67–69. Thus the following analysis should be understood as just a first attempt to explore the sensory concept and likely in consequence the relationship of the eurypterids to other arthropod groups based on the comparison of visual systems. This may provide insights into the evolution of compound eye systems in general.

All specimens illustrated here (Fig. 1c–e) reveal a typical pattern of an ommatidium in cross section, which results from an overhead view, when the overlying parts of the eye have been lost during the course of time. In most of these a zone of former pigment (cells) can be distinguished round the periphery, sometimes even having a dark appearance, possibly due to relicts of the carbon formerly contained in the pigment cells. More centrally traces of sensory cells can be made out, each arranged like a rosette and of different number among the systems (5–9 cells, Fig. 2a–d,f,k–u). In diameter of ~70 µm the units are very similar in size to the receptor cells of adult Limulus (~70 µm70,71). The most important part, the centre, repeats the pattern mentioned above in describing the Limulus rhabdomeric structure. Though the fine individual microvillar structures themselves have not been preserved, we find a comparable wide dark ring with a more or less circular bright structure in the centre. It is quite remarkable to find such a central structure in a fossilised rhabdom, but very clearly it is evident in Fig. 2a–f,o,p–r, and indicated as a central dot inside of the rhabdom in Fig. 2s–u.

There is a good case for assuming (see below) that the dark ring represents the relics of the rhabdomeric/microvillar arrays, the bright centre the dendrite of an eccentric cell. This is a recurrent pattern in all examples we found, illustrated in Fig. 2. It strongly suggests that the eurypterid system is of the xiphosuran type.

Discussion

The results above clearly show that in terms of their ordering, the lens cylinders (exocones) and the internal structure of the underlying visual unit (variable number of receptor cells, very probably the existence of an eccentric cell as an element of the ommatidium), the eurypterid eyes are almost identical to xiphosuran compound eyes.

While in highly resolving mandibulate apposition compound eyes the facets are ordered normally in a hexagonal pattern, in Limulus the ommatidia are irregularely positioned50. The xiphosurans investigated here show a regular, squared pattern of the facets. Squared arrangements of lenses are typical for superposition eyes of mandibulates, namely among decapod crustaceans54. To find a squared pattern in J. rhenaniae indicates an autonomous character, perhaps suggesting a specialised visual system.

There is an important issue to discuss at this juncture, the relatively enormous size of the receptors in the compound eyes of Jaekelopterus rhenaniae. Figure 2m–u show the conspicuously large relics of the eurypterid receptor cells, which reach sizes of ~70 µm. In human retinas, the receptor size lies at the limit of any physically possible dimension - at about 1 µm, the lower limit of arthropod receptor diameters consequently also lies at 1–2 µm, while the diameter of normal ommatidia as a whole achieves between 5–50 µm72. The diameter of rhabdoms often reaches between 1.5–3.5 µm43, consequently the size of a normal receptor cell is smaller or around 10 µm. In particular, the photoreceptors of Limulus, however, are among the largest in the animal kingdom73. Limulus, as the benchmark needed here, the size of the rhabdom lies at about 60 µm (diameter69), equal to those as found in J. rhenaniae (~60 µm, Fig. 2o), the size of the entire ommatidium at 170–~250 µm73,74, are identical to the diameters of our material (~250 µm, all examples of Fig. 2). Thus, the sizes of the ommatidia of J. rhenaniae match absolutely those of Limulus. Consequently, the size of these photoreceptors is the ~70-fold of the human or common arthropodan receptor size.

At this point some more references may be cited to support this important issue. Firstly, the present classic reference about the morphology of the Limulus compound eye is that of Fahrenbach 1969, p. 25270. He describes how the body of the ommatidium is formed by primary receptor cells with 70 µm in diameter, the retinula. They are grouped like orange slices about the central tapering dendrite of the secondary receptor, the eccentric, cell. The eccentric cell, a modified receptor cell, also measures about 70 µm. Fahrenbach notes that the number of retinula cells per ommatidium averages between 10 and 13 for different individuals, the observed range covering 4 to 20 cells. (70, p. 252), in the eurypterid we find 5 to 9 cells. These descriptions of the Limulus-eye were confirmed by other authors, such as Batelle 2016, p. 81075: [photoreceptor cells: about 150 µm long and 70 µm wide in adults, furthermore74, p. 26176, p. 416, Fig. 2, and many others.] The enormous size of the Limulus photoreceptors gave rise to the first electrophysiological intracellular recordings in the nineteen-sixties - seventies (e.g.77,78, and other research) discovering the ionic mechansims of transduction and the discrete waves (quantum bumps) as responses to single photons (79–82, and others). As a whole, these investigations, based on the exceptionally large photoreceptors of Limulus established an important part of modern electrophysiology.

Since Exner in 189150 described the fascinating physical properties of the lens cylinders in the compound eye of the xiphosuran Limulus, this system has been subject of intense research, morphologically and physically (for an overview see52,83,84). It is now evident that this eye is, not just in consideration of its dioptric apparatus, very different from any tetraconate compound eye, such as that of a bee or dragonfly, but also in its entire morphology. In the eye of the horseshoe crab the receptor cells are coupled directly in the rhabdom, namely by the central dendrite of the eccentric cell. The function of the eccentric cells, probably among others, is to enhance contrasts and edge-perception, important especially for an organism active at low light conditions and in the scattered light conditions of the water column. The similarly structured rhabdom in the eurypterid Jaekelopterus rhenaniae investigated here, allows to assume that the same function already existed at least since the Lower Devonian.

The earliest horseshoe crab-fossils come from the Early Ordovician (more than 470 Mya old)47, and the family Limulidae, comprising all extant species, dates back to the Triassic, about 240 Mya85. Today there exist four species of three genera. Many of the common characteristics of eurypterids and xiphosurans have been considered to be symplesiomorphic or convergent due to a shared aquatic life style. As mentioned before, the eyes of modern arachnids, however, are not compound eyes, but single-lens eyes, and probably developed by partition of compound eyes and fusion of their ommatidia55–57. They must be understood as highly derived systems, while their ancestral structure, for example the existence of eccentric cells, can no longer be perceived. As mentioned above, Palaeozoic and Mesozoic scorpions, also possessed compound eyes, in outer appearance not dissimilar to eurypterid eyes55. Very probably, according to the results presented here, their internal compound eye-structures also may have been similar.

Most recently Fleming et al.86 analysed a large-scale data set of ecdysozoan opsins; comparing this with morphological analyses of key Cambrian fossils with preserved eye structures. They found that multi opsin vision evolved in a period of 35–71 million years through a series of gene duplications. They show that while Chelicerata have 4 opsins, Pancrustacea (crustaceans and hexapods) already possess 585. Consequently this may indicate an earlier origin of the chelicerate visual system, because to develop the fifth opsine takes time (principle of genetic clocks). Bitsch and Bitsch87, referring to Fahrenbach51,70,88,89 considered the eccentric cell to be autapomorphic to xiphosurans (ref. 87, p. 188). If, however, the eurypterids possessed an eccentric cell as well, this structure may be plesiomorphic to Chelicerata. Fahrenbach described that double eccentric cells are not uncommon in Limulus (ref. 70, p. 452). A single eccentric cell, however, is typical, and a further reduction during evolution in the context of changing ecological constrains and along phylogeny can be imagined easily. This element may not belong to the oldest form of any compound eye, its form and occurrence lies still in the dark.

Functionally, with several thousands of facets (>3545 facets/eyes and >747.235 mm² eye area)22, and probably being equipped with a contrast enhancing neuronal system due to the eccentric cells, the giant sea scorpion Jaekelopterus rhenaniae from the Early Devonian of Germany had a very effective visual capacity for high acuity and sensitivity, excellently adapted to an efficient, visually guided, aquatic predatory life-style.

In summary our results suggest a close similarity between the xiphosuran and the eurypterid eye, confirming the basal phylogenetic connection between both forms and lending support for a close relationship as indicated by some phylogenetic analyses (e.g.90). Convergent eye evolution, generating more or less identical sophisticated visual systems in xiphosurans and eurypterids as found here, seems rather improbable. This means, that the visual system equipped with lens cylinders and an eccentric cell with all its functions, is very basal. If so, this furthermore implies that the Palaeozoic arachnid visual system also possessed an eccentric cell. This primordial arachnid eye may then have given rise to the eyes of modern arachnids in the course of terrestrialisation.

This is also supported by the notion that the oldest known arachnids, the Silurian scorpions, had compound lateral eyes58,91–93, while the lateral eyes of extant crown group scorpions consist of two to five pairs of lateral lenses86. Perhaps in relation to a ground-dwelling terrestrial life-style extant arachnids mostly seem to rely on non-visually sensory systems such as mechanoreceptors (trichobothria, pectines and highly sensitive setae) or chemosensory systems, which seem to be metabolically much less expensive than visual systems94,95; so eyes may become reduced or disappear. One may remember here, that many of the arthropods appearing with the Cambrian explosion, were benthic, requiring a visual system quite sensitive to light, and taking advantage of any contrast enhancing system such as lateral inhibition, which is tied up to the eccentric cells. Even if the evidence of the lens cylinders in the eurypterid eye, as strong indications of the existence of eccentric cells, represented by their dendrites in the centres of the rhabdoms, is given here, future findings of better preserved material may confirm these findings by the use of synchrotron radiation or computer tomography. Appropriate material is, to our knowledge, still lacking, and thus the application of these methods is not possible, perhaps will never be, and consequently the evidence given here may remain all that is attainable at present.

Material and Methods

The macrophotograps of Figs. 1c–l,n–u, 2q–u were taken with a Keyence digital microscope (VHX-700F, objective VH-Z20T and at the Institute of Biology Education (Zoology), University of Cologne. The specimens were not submerged in isopropanol in order to retain the contrasts of the edges. The pictures were processed and arranged to figures with Adobe Photoshop CS3 and Adobe Photoshop Elements.

The macrophotographs of Fig. 2a–d were taken with the specimens submerged in isopropanol using a Canon EOS 600D SLR camera equipped with a Canon MP-E 65 mm macro lens. Free image stacking software (CombineZM by Alan Hadley) was then employed to produce composites with enhanced depth of field using photographs with differing focal planes. These were processed and arranged into figures using Adobe Photoshop CS3.

The SEM photographs were taken at the Biocentre Cologne, (FEI -Quanta FEG 250, Thermo Fischer Scientific).

The eurypterid eyes figured in this contribution are stored in the Geological Institute of the University of Cologne, leg. E. Evangelou (Figs. 1c–e,q–u, 2). They were collected from Siegenian (possibly lowermost Emsian in terms of the international stratigraphic frame) strata of the Jaeger Quarry near Frielingshausen/Bergisches Land, Germany.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank M. Amler (Geological Institute of the University of Cologne) for access to material in his care, H.P. Bollhagen for taking the SEMs of Fig. 2k–o, A. Büschges for the allowance to use the SEM at the Zoology Department of the University of Cologne, and E. Möhlmann and A. Germund for their help with the schematic drawings of Fig. 1u and v., P. Gensel, Weimar for providing Carcinoscorpius exuviae, S. Powell (Bristol) for permitting to reproduce his reconstruction of Jaekelopterus, S. Chatterjee for the free access to his photograph (Fig. 1c) of a red listed species, and G. Gauvry, Dover, Delaware and C. Etgen, Annapolis, Maryland for their helpful discussions.

Author contributions

B.S. wrote the main manuscript with input of M.P. and E.C., conceived the investigation, took the photographs and prepared the figures, except photographs in 1b and 2a-d, which were taken by M.P. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Braddy SJ, Poschmann M, Tetlie OE. Giant claw reveals the largest ever arthropod. Biol. Lett. 2008;4:106–109. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conway Morris, S. The crucible of creation: the Burgess Shale and the rise of animals. (Oxford University Press, 1998).

- 3.Briggs DEG. Gigantism in Palaeozoic arthropods. Spec. Pap. Palaeontol. 1985;33:157. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunlop JA. Gigantism in arthropods. Am. Tarantula Soc. 1995;4:145–147. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whyte MA. Palaeoecology: a gigantic fossil arthropod trackway. Nature. 2005;438(7068):576. doi: 10.1038/438576a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider JW, Werneburg R. Arthropleura, der größte landlebende Arthropode der Erdgeschichte - neue Funde und neue Ideen. Semana. 2010;25:61–86. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamsdell JC, Briggs DEG, Liu HP, Witzke BJ, McKay RM. The oldest described eurypterid: a giant Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian) megalograptid from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa. BMC Evol. Biol. 2015;15:169. doi: 10.1186/s12862-015-0443-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamsdell JC, Braddy SJ. Cope’s rule and Romer’s theory: patterns of diversity and gigantism in eurypterids and Palaeozoic vertebrates. Biol. Lett. 2010;6:265–269. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benton M. J. When Life Nearly Died: The greatest mass extinction of all time. (Thames & Hudson, 2005).

- 10.Bergstrom C. T. & Dugatkin L. A. Evolution. (Norton, 2012).

- 11.Brandt, D. S. & McCoy, V. E. Modern analogs for the study of eurypterid paleobiology in Experimental approaches to understanding fossil organisms (eds Hembree, D. I., Platt, B. F. & Smith, J. J.) 73–88 (Springer, 2014).

- 12.Braddy SJ. Eurypterids from the Early Devonian of the Midland Valley of Scotland. Scott. J. Geol. 2000;36:115–122. doi: 10.1144/sjg36020115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tetlie OE, Brandt DS, Briggs DEG. Ecdysis in sea scorpions (Chelicerata: Eurypterida) Palaeogeogr.Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2008;265:182–194. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamsdell JC, Selden PA. From success to persistence: identifying an evolutionary regime shift in the diverse Paleozoic aquatic arthropod group Eurypterida, driven by the Devonian biotic crisis. Evolution. 2017;71:95–110. doi: 10.1111/evo.13106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamsdell, J. C., Lagebro, L., Edgecombe, G. D., Budd, G. E. & Gueriau, P. Stylonurine eurypterids from the Strud locality (Upper Devonian, Belgium): new insights into the ecology of freshwater sea scorpions. Geol. Mag. 1–7 (2019).

- 16.Manning PL, Dunlop JA. The respiratory organs of eurypterids. Palaeontology. 1995;38:287–297. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selden PA. Eurypterid respiration. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond B-Biol. Sci. 1985;269:1195–1203. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamsdell JC. Breathing life into an extinct sea scorpion: revealing the gill structure of a three-dimensionally preserved eurypterid through microCT scanning. PALASSNewsletter. 2018;98:88–91. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laub RS, Tollerton VP, Berkof RS. The cheliceral claw of Acutiramus (Arthropoda: Eurypterida): functional analysis based on morphology and engineering principles. Bull. Buffalo Soc. Nat. Sci. 2010;39:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson RP, McCoy VE, McNamara ME, Briggs DEG. What big eyes you have: The ecological role of giant pterygotid eurypterids. Biol. Lett. 2014;10:20140412. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCoy VE, Lamsdell JC, Poschmann M, Anderson RP, Briggs DEG. All the better to see you with: eyes and claws reveal the evolution of divergent ecological roles in giant pterygotid eurypterids. Biol. Lett. 2015;11:20150564. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poschmann M, Schoenemann B, McCoy V. Telltale eyes: The lateral visual systems of Rhenish Lower Devonian eurypterids (Arthropoda, Chelicerata) and their palaeobiological Implications. Palaeontology. 2016;59:295–304. doi: 10.1111/pala.12228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tollerton VP. Morphology, Taxonomy, and Classification of the Order Eurypterida Burmeister, 1843. J. Paleont. 1989;63:642–657. doi: 10.1017/S0022336000041275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woodward H. On a new genus of Eurypterida from the Lower Ludlow rocks of Leintwardine, Shropshire. Q. J. Geol. Soc. 1865;21:490–492. doi: 10.1144/GSL.JGS.1865.021.01-02.54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Størmer, L., Petrunkevitch, A., & Hedgpeth, J. W. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology: Part P, Arthropoda 2. (Geological Society of America and University of Kansas, Lawrence (Kansas), 1955).

- 26.Kraus O. Zur phylogenetischen Stellung und Evolution der Chelicerata. Ent. Germ. 1976;3:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weygoldt P, Paulus HF. Untersuchungen zur Morphologie, Taxonomie und Phylogeny der Chelicerata. Z. Zool. Syst. Evol. Forsch. 1979;17:85–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0469.1979.tb00694.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shultz JW. Evolutionary Morphology and Phylogeny of Arachnida. Cladistics. 1990;6:1–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1990.tb00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunlop, J. A. & Selden, P. A. The early history and phylogeny of the chelicerates in Arthropod relationships (eds Fortey, R. A. & Thomas, R. H.) 221–235 (Springer, 1998).

- 30.Braddy SJ, Aldridge RJ, Gabbot SE, Theron JN. Lamellate book-gills in a late Ordovician eurypterid from the Soom Shale, South Africa: support for a eurypterid-scorpion clade. Lethaia. 1999;32:72–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1502-3931.1999.tb00582.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunlop JA. A review of chelicerate evolution. Bol. Soc. Entomol. Aragonesa. 1999;26:255–272. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunlop JA, Webster M. Fossil evidence, terrestrialization and arachnid phylogeny. J. Arachnol. 1999;27:86–93. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubin M, Lamsdell JC, Prendini L, Hopkins MJ. Exocuticular hyaline layer of sea scorpions and horseshoe crabs suggests cuticular fluorescence is plesiomorphic in chelicerates. J. Zool. 2017;303:245–253. doi: 10.1111/jzo.12493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Versluys J, Demoll R. Die Verwandtschaft der Merostomata mit den Arachnida und den anderen Abteilungen der Arthropoda. Proc. Kon. Akad. Wetensch. Amsterdam. 1921;23:739–765. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamenz C, Staude A, Dunlop JA. Sperm carriers in Silurian sea scorpions. Naturwissenschaften. 2011;98:889–896. doi: 10.1007/s00114-011-0841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braddy SJ, Dunlop JA. The functional morphology of mating in the Silurian eurypterid, Baltoeurypterus tetragonophthalmus (Fischer, 1839) Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 1997;121:435–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1997.tb01282.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamsdell JC. Revised systematics of Palaeozoic ‘horseshoe crabs’ and the myth of monophyletic Xiphosura. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2013;167:1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00874.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ballesteros, J. A. & Sharma, P. P. A critical appraisal of the placement of Xiphosura (Chelicerata) with account of known sources of phylogenetic error. Syst. Biol. 1–14, (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Schoenemann, B., Pärnaste, H. & Clarkson, E. N. Structure and function of a compound eye, more than half a billion years old. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 201716824 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Osorio D, Bacon JP. A good eye for arthropod evolution. BioEssays. 1994;16:419–424. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osorio D, Bacon JP, Whitington PM. The Evolution of Arthropod Nervous Systems: Modern insects and crustaceans diverged from an ancestor over 500 million years ago, but their neural circuitry retains many common features. Am. Sci. 1997;85:244–253. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Melzer RR, Diersch R, Nicastro D, Smola U. Compound eye evolution: Highly conserved retinula and cone cell patterns indicate a common origin of the insect and crustacean ommatidium. Naturwissenschaften. 1997;84:542–544. doi: 10.1007/s001140050442. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cronin, T. W., Johnsen, S., Marshall, N. J. & Warrant, E. J. Visual ecology. (Princeton University Press, 2014).

- 44.Gaten E. Optics and phylogeny: Is there an insight? The evolution of superposition eyes in the Decapoda (Crustacea) Contrib. Zool. 1998;67:223–236. doi: 10.1163/18759866-06704001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harzsch S, et al. Evolution of arthropod visual systems: development of the eyes and central visual pathways in the horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus Linnaeus, 1758 (Chelicerata, Xiphosura) Dev. Dyn. 2006;235:2641–2655. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kin A, Błażejowski B. The Horseshoe Crab of the Genus Limulus: Living Fossil or Stabilomorph? PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e108036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Roy P, et al. Ordovician faunas of Burgess Shale type. Nature. 2010;465:215–218. doi: 10.1038/nature09038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamsdell JC. Horseshoe crab phylogeny and independent colonizations of fresh water: ecological invasion as a driver for morphological innovation. Palaeontology. 2016;59:181–194. doi: 10.1111/pala.12220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herzog ED, Barlow RB. The Limulus-eye view of the world. Vis. Neurosci. 1992;9:571–580. doi: 10.1017/S0952523800001814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Exner, S. Die Physiologie der facettirten Augen von Krebsen und Insecten: eine Studie. (Franz Deuticke, 1891).

- 51.Fahrenbach WH. The morphology of the eyes of Limulus, I Cornea and epidermis of the compound eye. Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat. 1968;87:279–291. doi: 10.1007/BF00319725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chamberlain SC. Circadian rhythms in the horseshoe crab lateral eye: signal transduction and photostasis. Bioelectrochem. Bioenerg. 1998;45:111–121. doi: 10.1016/S0302-4598(98)00077-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hartline HK, Wagner HG, Ratliff F. Inhibition in the eye of Limulus. J. Gen. Physiol. 1956;5:651–671. doi: 10.1085/jgp.39.5.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Land, M. F. Optics and vision in invertebrates. Handbook of sensory physiology Vol VII/6B (ed. Autum H.) 471-592 (Springer, 1981).

- 55.Miether ST, Dunlop JA. Lateral eye evolution in the arachnids. Arachnology. 2016;17:103–119. doi: 10.13156/arac.2006.17.2.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paulus, H. F. Eye structure and the monophyly of the arthropod eye in Arthropod phylogeny (ed. Gupta, A. P.) 299–383 (van Nostrand, 1979).

- 57.Morehouse NI, Buschbeck EK, Zurek DB, Steck M, Porter ML. Molecular Evolution of Spider Vision: New Opportunities, Familiar Players. Biol. Bull. 2017;23:21–38. doi: 10.1086/693977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Howard RJ, Edgecombe GD, Legg DA, Pisani D, Lozano-Fernandez J. Exploring the evolution and terrestrialization of scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones) with rocks and clocks. Org. Divers. Evol. 2019;19:71–86. doi: 10.1007/s13127-019-00390-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paterson JR, et al. Acute vision in the giant Cambrian predator Anomalocaris and the origin of compound eyes. Nature. 2011;480:237. doi: 10.1038/nature10689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strausfeld NJ, et al. Arthropod eyes: The early Cambrian fossil record and divergent evolution of visual systems. Arthr. Str. & Dev. 2016;45:152–172. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nilsson DE, Pelger S. A pessimistic estimate of the time required for an eye to evolve. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B - Biol. Sci. 1994;256:53–58. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paulus HF. Phylogeny of the Myriapoda–Crustacea–Insecta: a new attempt using photoreceptor structure. J. Zoological. Syst. Evol. Res. 2000;38:189–208. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0469.2000.383152.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Müller CHG, Meyer-Rochow VB. Fine structural description of the lateral ocellus of Craterostigmus tasmanianus Pocock, 1902 (Chilopoda: Craterostigmomorpha) and phylogenetic considerations. J. Morphol. 2006;267:850–865. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harzsch S, Melzer RR, Müller CHG. Mechanisms of eye development and evolution of the arthropod visual system: The lateral eyes of myriapoda are not modified insect ommatidia. Org. Divers. Evol. 2007;7:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ode.2006.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Müller CH, Rosenberg J, Richter S, Meyer-Rochow VB. The compound eye of Scutigera coleoptrata (Linnaeus, 1758)(Chilopoda: Notostigmophora): an ultrastructural reinvestigation that adds support to the Mandibulata concept. Zoomorphology. 2003;122:191–209. doi: 10.1007/s00435-003-0085-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seilacher A, Reif W-E, Westphal F. Sedimentological, ecological and temporal patterns of fossil Lagerstätten. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B - Biol. Sci. 1985;311:5–23. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1985.0134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schoenemann B, Clarkson EN. Discovery of some 400 million year-old sensory structures in the compound eyes of trilobites. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1429. doi: 10.1038/srep01429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vannier J, Schoenemann B, Gillot T, Charbonnier S, Clarkson E. Exceptional preservation of eye structure in arthropod visual predators from the Middle Jurassic. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10320. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scholtz G, Staude A, Dunlop JA. Trilobite compound eyes with crystalline cones and rhabdoms show mandibulate affinities. Nat. comm. 2019;10:2503. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10459-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fahrenbach WH. The morphology of the eyes of Limulus. II Ommatidia of the compound eye. Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat. 1969;93:451–483. doi: 10.1007/BF00338531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Battelle BA. Opsins and Their Expression Patterns in the Xiphosuran Limulus polyphemus. Biol Bull. 2017;233:3–20. doi: 10.1086/693730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Land MF. Visual acuity in insects. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 1997;42:147–177. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Battelle BA. The eyes of Limulus polyphemus (Xiphosura, Chelicerata) and their afferent and efferent projections. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2006;35:261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Passaglia CL, Dodge FA, Barlow RB. Cell-based model of the Limulus lateral eye. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1800–1815. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.4.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Battelle BA. Simple eyes, extraocular photoreceptors and opsins in the American horseshoe crab. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2016;56:809–819. doi: 10.1093/icb/icw093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miller, W. H. Mechanisms of photomechanical movement in Photoreceptor Optics (eds Snyder, A. W. & Menzel, R. I.) 415–428 (Springer, 1974).

- 77.Fuortes MGF, Yeandle S. Probability of occurrence of discrete potential waves in the eye of Limulus. J. Gen. Physiol. 1964;47:443–463. doi: 10.1085/jgp.47.3.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Barlow RB, Kaplan E. Properties of visual cells in the lateral eye of Limulus in situ: intracellular recordings. J. Gen. Physiol. 1977;69:203–220. doi: 10.1085/jgp.69.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Borsellino A, Fuortes MGF. Responses to single photons in visual cells of Limulus. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1968;196:507–539. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fuortes, M. G. F. & O’Bryan, P. M. Generator potentials in invertebrate photoreceptors in Physiology of Photoreceptor Organs (d. Fuortes M. G. F.) 279–319 (Springer, 1972).

- 81.Fuortes M. G. F. & O’Bryan, P. M. Responses to single photons in Physiology of Photoreceptor Organs in Handbook of Sensory Physiology. Vol. VII/2 (ed. Fuortes, M. G. F.) 321–338 (Springer, 1972).

- 82.Laughlin, S. Neural principles in the peripheral visual systems of invertebrates In. Handbook of Sensory Physiology. Vol VII/6b. (ed. Autrum H. J.) 133–280 (Springer, 1981).

- 83.Hartline, H. K. & Ratliff, F. Inhibitory interaction in the retina of Limulus in Physiology of Photoreceptor Organs (ed. Fuortes, M. G. F.) 381–447 (Springer, 1972).

- 84.Stavenga, D. G. & Hardie, R. C. Facets of vision. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

- 85.Lamsdell JC, McKenzie SC. Tachypleus syriacus (Woodward)–a sexually dimorphic Cretaceous crown limulid reveals underestimated horseshoe crab divergence times. Org. Divers. Evol. 2015;15:681–693. doi: 10.1007/s13127-015-0229-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fleming JF, et al. Molecular palaeontology illuminates the evolution of ecdysozoan vision. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2018;285(1892):20182180. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2018.2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bitsch, C. & Bitsch, J. Evolution of eye structure and arthropod phylogeny in Crustacea and Arthropod Relationships (eds Koenemann, S. & Jenner, R.A.) 185–214 (Taylor & Francis, 2005).

- 88.Fahrenbach WH. The visual system of the horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus. Int. Rev. Cyt. 1975;41:285–349. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)60970-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fahrenbach, W. H. Merostomata in Microscopic Anatomy of Invertebrates (eds Harrison, W. F. & Locke, M.) 21–115 (Wiley-Liss, 1999).

- 90.Garwood RJ, Dunlop J. Three-dimensional reconstruction and the phylogeny of extinct chelicerate orders. PeerJ. 2014;2:e641. doi: 10.7717/peerj.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jeram, A. J. Phylogeny, classification and evolution of Silurian and Devonian scorpions in Proc. 17th European Colloquium of Arachnology, Edinburgh, UK (ed. Selden, P.A.) 17–31 (1998).

- 92.Waddington J, Rudkin DM, Dunlop JA. A new mid-Silurian aquatic scorpion - one step closer to land? Biol. Lett. 2015;11:20140815. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dunlop JA, Tetlie OE, Prendini L. Reinterpretation of the Silurian scorpion Proscorpius osborni (Whitfield): integrating data from Palaeozoic and Recent scorpions. Palaeontology. 2008;51:303–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00749.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Laughlin SB, van Steveninck RRDR, Anderson JC. The metabolic cost of neural information. Nat. neurosci. 1998;1:36. doi: 10.1038/236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schoenemann Brigitte. Evolution of Eye Reduction and Loss in Trilobites and Some Related Fossil Arthropods. Emerging Science Journal. 2018;2(5):272. doi: 10.28991/esj-2018-01151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]