Abstract

Social–ecological memory (SEM) is an analytical construct used to consider the ways by which people can draw upon biological materials and social memory to reorganize following a disturbance. Since its introduction into the literature, there have been few cases that have considered its use. We use ethnographic methods to study Bribri people’s commercial crops that have been invaded by different fungal pathogens and have undergone several disturbance recovery cycles. We show how the Bribri have used social memory and ecological memory together, dynamic interactions of legacies and reservoirs, and the role of mobile links for reorganization following the impact of fungal diseases. Insights from the Bribri indicate that protection of biodiversity, management practices, and adoption of new species and varieties are all crucial. The SEM concept extends the understanding of Indigenous knowledge, to include linkages to other peoples’ memory and to landscapes as reservoirs of SEM. An understanding of how people use SEM to respond to disturbances is necessary as biodiversity changes are expected to become more pronounced in the future.

Keywords: Bribri Indigenous people, Fungal pathogens, Resilience, Social–ecological memory

Introduction

Changes in biodiversity, such as the invasion of fungal pathogens in tropical agricultural lands, are occurring at an ever-faster pace (Mace et al. 2005), as many drivers that result from globalization and environmental factors interact (Leichenko and O’Brien 2008). The study of agricultural biodiversity change is challenging in many ways. The invasions of fungal pathogens in tropical agricultural lands are complex, nonlinear, and multi-scalar and have the potential to lead to livelihood transformations (Zimmerer et al. 2015). Here we use resilience thinking (Gunderson and Holling 2002) and aim to understand how sources of resilience can be identified and nurtured (Folke et al. 2005).

We deal with agricultural systems in our study area as complex social–ecological systems—the integrated concept of humans in nature in which the social and ecological systems are in a two-way feedback relationship (Berkes and Folke 1998). We consider that the memory in these social–ecological systems enables change in response to perturbations (Folke et al. 2003) and define social–ecological memory (SEM) as the accumulated experiences and history of ecosystem management collectively held by a community in an social–ecological system (Barthel et al. 2010; Nykvist and Von Heland 2014).

In the Talamanca region of Costa Rica, multiple cycles of fungal pathogen invasions, such as Panama disease (Fusarium oxysporum Schlecht f. sp. cubense), Black Sigatoka (Mycosphaerella fijiensis M. Morelet), and Monilia (Moniliophthora roreri (Cif.)), have affected banana (Musa sp.), plantain (Musa sp.), and cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) yields. They have also affected the livelihoods of the Bribri people who have traditionally relied on these crops to sustain their families (Borge and Villalobos 1994). While the commercialization of these crops provides monetary income to Bribri people, plantains, which are starchy and are typically cooked before eating, as well as bananas, are major staples for the Bribri diet. The cacao tree plays an important role in the Bribri worldview (Borge 2011). Little is known about the mechanisms of Bribri people’s historical responses to biodiversity change resulting from the invasion of fungal pathogens in their commercial crops.

A better understanding of how Bribri people have historically responded to fungal pathogens in their commercial crops is necessary, as some of these changes are expected to become more pronounced in the future. For example, Witches Broom (Crinipellis perniciosa Stahel Aime & Phillips-Mora) and Panama disease Tropical Race four have the potential of affecting cacao (Meinhardt et al. 2008) and banana production worldwide (Marquardt 2001). Here, we use the concept of SEM to analyze how the Bribri have dealt with multiple cycles of pathogen invasions and still retained the resilience of their commercial crops.

The Holling notion of resilience is the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedbacks (Walker et al. 2004). Used in resilience thinking, SEM is considered crucial in providing the basic material and memory by which a social–ecological system reorganizes following a disturbance. SEM includes both ecological memory and social memory in the system and provides alternatives for re-organization after a disturbance or crisis (Folke et al. 2003). Indigenous knowledge (IK) or traditional ecological knowledge (Berkes 2018) is part of SEM.

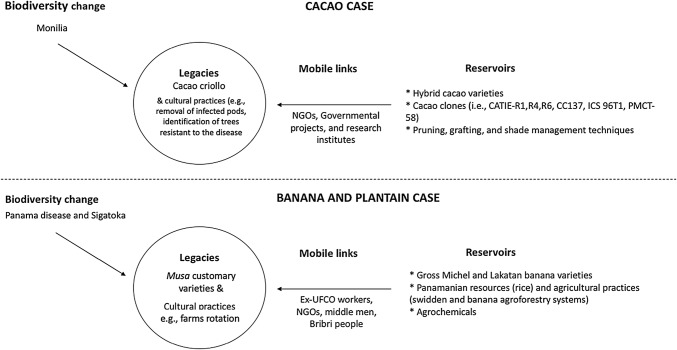

The conceptual approach used in this research was based on the following considerations about SEM from Fig. 14.3 of Folke et al. (2003). First, we assumed that the ability of communities to rebuild after a disruption (or disturbance or crisis) is partly dependent on the use and management of the species richness available in a given area (Davidson-Hunt and Berkes 2010; Davidson-Hunt et al. 2016). Second, we examined the idea that locally available biodiversity richness is a function of biological and social legacies (species, knowledge, practice, institutions and beliefs/worldview that persist in the area despite the disruption). Third, we considered that the use of biodiversity in the area after the disruption is also a function of reservoirs, both of ecological and social memory. These are reservoirs of biodiversity from support areas, and knowledge/practice for resource use that are transmitted from one area to another. Memories of other groups and landscapes can function as reservoirs of SEM (Turner et al. 2003; Crona and Bodin 2006).

Transmission of knowledge takes place by internal processes, such as the participation of individuals of a cultural group in activities and rituals, elders’ teachings and stories (e.g., Turner et al. 2003). Transmission also takes place by external processes, such as linkages and exchanges of information through social networks (Barthel et al. 2010; Nykvist and Von Heland 2014). Legacies and reservoirs are connected by mobile links, agents that provide the connections. The dynamic interactions of legacies and reservoirs provide the potential for renewal and reorganization after being affected by changes in biodiversity. More broadly, SEM is crucial for the resilience of the system, its ability to change and persist in the face of disturbance (Gunderson and Holling 2002). The relationship between resilience and SEM has received limited attention in the literature, considering its importance. Exceptions include Nazarea (2006), Barthel et al. (2010), Nykvist and Von Heland (2014), Wilson et al. (2017), and Kim et al. (2017).

The primary objective of this article is to understand the role of SEM in peoples’ responses to biodiversity change. Specifically, we consider how Bribri people in Yorkin have used their SEM to respond to the impact of invasive pathogens in their commercial crops. Seen through the SEM lens, we should expect that (1) the practices nurturing the SEM of a community will be a combination of internal processes (e.g., diversification, protection of biodiversity) and external processes (e.g., transmitted memory from other communities), and (2) the knowledge for the use of biodiversity is produced and reproduced through Bribri engagement with disruptions, and their actions in reconfiguring their commercial crops at different points in time. These processes suggest that SEM is not a static corpus of biological organisms, skill, practice, and values but something that is continuously constructed through the creativity and skill of people living within dynamic environments (Bateson 1972; Ingold 2000). At times, however, this is punctuated by significant events like new incursions of pathogens, leading people to draw upon both the legacies and reservoirs of biodiversity in their responses.

The next part of the article begins by providing a background on the study area and the research context. Next, we present the methods used in the 9 months of fieldwork in Yorkin. We then present the results of the fieldwork, where we focus on how people have drawn upon their SEM to respond to the impact of invasive pathogens in the three commercial crops that currently sustain the Bribri livelihoods, cacao, banana, and plantain. In the last section, we discuss the implications of our approach and findings for further inquiry into the role of SEM and biodiversity change.

Research context and methodology

Our study area is located in the Talamanca Indigenous Reserve (TIR). The TIR is located in the Province of Limón in the southeastern region of Costa Rica (Fig. 1). It has a tropical climate, with two short dry seasons per year and the average annual rainfall of 2370 mm (Instituto Meteorológico Nacional, IMN 2016). The TIR is one of 22 national indigenous reserves established in 1977 by the Costa Rican Government to protect the national native lands and cultures, including the Bribri (Borge and Villalobos 1994). The Bribri are the second largest indigenous group in Costa Rica with a population of nearly 7772 (Costa Rican Census 2011). Since pre-colonial times, the Bribri have had interactions with Indigenous people from South America and North America (Stone 1961). The Bribri contact with these groups influenced the Bribri production system, religion, oral tradition, and mythology (Stone 1961). Bribri livelihoods have evolved in many ways in recent years. However, the production of cacao, banana, and plantain has been the primary source of income in the region in the last 50 years (Borge 2011).

Fig. 1.

Approximate location of Yorkin

The community of Yorkin is located in the transboundary area of Costa Rica and Panama (Fig. 1). In 2016, the population of Yorkin was 232 people (Rodríguez field notes July 26, 2016). As well as in many places of Talamanca, the Bribri are traditional cacao–banana agroforesters, along with subsistence fishing, hunting, cultural tourism, and the commercial production of plantain.

The Yorkin landscape can be described as a mix of different land patches (Rodríguez and Davidson-Hunt 2018). In the floodplains, people produce plantain for their consumption and commercial purposes. In the foothills, people grow banana and cacao in agroforestry systems. Likewise, people produce rice, corn, and beans in swidden plots, harvest medicinal plants and hunt wildlife from the forestry areas that surround the community.

This research was undertaken with the acknowledgment of the Bribri local authority “Asociación de Desarrollo Integral del Territorio Indígena Bribri” (Development Association of the Indigenous Territory Bribri, Costa Rica) and obtained ethics approval from the Joint Faculty Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba (Protocol #J2015:093 HS 18831).

We used ethnographic approaches to draw upon the memory of participants to identify how people have responded to the invasion of pathogens in their commercial crops. This information was obtained by conducting participant observation, life history interviews, unstructured interviews, and transect walks. Participant observation (Bernard 2006) (September–December 2015 and March–August 2016), undertaken by Rodríguez, allowed her to generate trust relationships with the participants of this study by being part of the community’s daily life activities. Participant observation activities also allowed her to understand the land use context and the primary management strategies used to prevent and control the pathogens affecting cacao, banana, and plantain farms. Unstructured interviews (Bernard 2006) were conducted with representatives of research institutes (N = 1), development organizations (N = 2), and government organizations (N = 1). These interviews covered the goals and activities of the primary conservation and development projects applied in Yorkin in the last 30 years. Life history interviews (Brannen 2013) were applied to an equal number of male and female Yorkin residents (14 in total), with the intention of understanding the main changes in biodiversity in their farms, as well as people’s responses to the disruptions. Transect walks (De Leon and Cohen 2005) were conducted in the cacao, banana, and plantain farms of 11 households to document the biodiversity richness of their farms. We used a qualitative approach because we were interested in having an in-depth understanding of the role of SEM as a source for re-organization following the outbreak of fungal pathogens in the Bribri farms (Creswell 2009).

The information documented during the fieldwork was transcribed and coded by theme (e.g., biodiversity change events, farmers’ responses, memories about resources used in the past) (Creswell 2009). The use of computer software, NVivo, supported qualitative analysis. We identified relevant patterns regarding changes in biodiversity, such as the invasion of crop pathogens, as well as the responses to mitigate and control them. To validate the interpretation of the findings, Rodríguez conducted verification sessions in May 2017.

Results

The cacao case

… And my dad taught me because I was a kid, he helped me to take care of his cacao farm… he taught me how to prune and to weed the cacao trees, all of that he taught me. It is an education I learned on my parent’s farm. Then there was a project that started with the establishment of some nurseries, and we decided to grow hybrid cacao trees… Later on, ANAI (development organization) came and gave us a technique of how to prune, to check the shape of the tree, the orientation of the branches, and I went somewhere else to study. They trained us on how to manage the farms, new ways and different types of pruning… APPTA (cacao cooperative in Talamanca) offered me many workshops, and I learned not only about my farm but also about how to work with the people of my community. I also saw how the cacao was managed, the importance of the organic cacao production. Then we got the organic certification. I learned about the quality of the cacao. (Longino Celles interview July 13, 2016)

The Bribri people have produced and harvested cacao since time immemorial (Borge 2011). Before 1950, Bribri people mainly used the cacao for subsistence, medicinal, and ritual purposes (Borge 2011). People in Yorkin remember producing this crop for commercial purposes around 1950 as the Costa Rican Government built a road that connected Yorkin to other towns, and there were several intermediaries in the area buying this crop (Rodríguez and Davidson-Hunt 2018). The production of cacao became the primary livelihood activity for Yorkin families in 1960–1979.

In 1979, the cacao industry shrunk as the cacao farms in Costa Rica were hit by M. roreri. This is a fungal pathogen that causes frosty pod rot, or monilia, in several species of the genus Theobroma and Herrania (Phillips-Mora 2003). This disease had been confined to South America until 1950. However, it caused an outbreak in Costa Rica in 1979 because of human-mediated dispersion (Phillips-Mora 2003). The prevention and control of monilia are complicated because the pathogen survives under different environmental conditions, has rapid dispersal, and affects several cacao commercial genotypes (Phillips-Mora and Wilkinson 2007).

After the impact of monilia, Bribri people remember using several immediate strategies to get rid of the pathogen (Rodríguez and Davidson-Hunt 2018). Some of the strategies included the removal of infected pods and the elimination of the trees that used to provide shade for the cacao (e.g., Dipteryx oleifera, Virola koschnyi). The farmers’ objective was to promote an environment that would stop the spread of the pathogen. These actions were costly and labor-intensive, discouraging producers to continue growing cacao. Therefore, people searched for alternative approaches.

One of the alternatives mentioned by the interviewees consisted of finding cacao trees resistant to monilia. This was done in two different ways. On the one hand, people requested the help of the Asociación de Nuevos Alquimistas (ANAI) to support them in finding cultivars that showed resistance (Rodríguez field notes June 26, 2016). On the other hand, people identified the trees that produced healthy pods in their farms, despite being affected by monilia, and protected them by controlling their shade, by weeding them, and pruning them. ANAI supported Yorkin farmers by buying from the Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza (CATIE) hybrids and by distributing these trees in the community in the late 1990s. CATIE produced hybrids by placing the pollen of a parental stock on the stigma of a flower of a different cultivar (Young 2007), and people in Yorkin used these trees to start new farms or to substitute the cacao trees they identified as being nonresistant to monilia.

Yorkin farmers not only adopted the hybrid cacao varieties, but also adopted new management practices. For instance, some residents learned to graft and used this knowledge to control the incidence of the disease. Others mastered other techniques such as different pruning techniques (e.g., cutting back old trees and removal of suckers), weeding, and the control of excessive shade.

Currently, people categorize the cacao trees in their farms as criollos, hybrids, or “injertos” (cloned germplasm). The criollo trees are the ones that were grown by the Bribri people during the cacao boom (1955–1979). The hybrid trees are the ones that ANAI distributed in Talamanca during the 1990s, and the injerto ones are the latest trees adopted in the area. The injerto cacaos were the result of a research program conducted by the CATIE whose objective was to select productive cacao clones resistant to monilia (Phillips-Mora et al. 2012).

In Yorkin, the criollo cacao is appreciated for the amount of butter in the seeds. The hybrid trees are noted for their productivity, and the injerto ones are preferred as they mature and produce fruit in a very short period (ca. 2 years). Although the seeds of all the trees are mixed and sold to intermediaries, people prefer to harvest the seeds of the criollo variety to extract its butter which is used by the Bribri for medicinal and ritual purposes (Rodríguez field notes July 14, 2016).

Bribri knowledge of criollo seeds, cultural practices to control the incidence of the monilia (e.g., removal of infected pods), as well as the adoption of new cacao germplasm and new management strategies, have allowed Yorkin farmers to continue producing cacao after the impact of the monilia (Table 1). The yields might not be as high as they used to be during the cacao boom, but cacao still sustains a part of their livelihoods. For example, an interviewee remembers harvesting 30–60 sacs (1 sac = 40 kg) of raw cacao in a 2 ha farm before the monilia arrived into the area. Currently, he harvests between 2 and 8 sacs from the same area. In 2015, the income received by the producers was US$ 0.66 per kg of raw cacao (Rodríguez field notes June 05, 2016).

Table 1.

Types of cacao germplasm and local management practices recorded during a nine-months fieldwork in Yorkin

| Spanish and folk name | Number of households with cacao germplasm in 2016 (N = 11) | Uses | Local management practices utilized for the three types of cacao germplasm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criollo | 9 | Commercial, subsistence, medicinal and ritual | Control of shade. Weeding and pruning practices. Removal of infected pods. Selection of trees resistant to monilia by observation and by grafting resistant germplasm into old cacao trees |

| Hybrid | 5 | Commercial and subsistence | |

| Clones | 7 | Commercial and subsistence |

According to the circumstances, the area designated to grow cacao has varied over the years, increasing in some periods while declining in others. Cacao farms have been as large as 14 ha in periods without pests (1935–1979) and as small as half a hectare when the incidence of pests has not been manageable (1979–1985). In the latter case, people grew other commercial crops to substitute for the lost income. The commercial production of banana and plantain has been an alternative to the production of cacao.

The banana and plantain case

Well, there are many banana varieties. We have Gros Michel, Lacatan alto, congo -alto called Lacatan bajo-, chopo morado y chopo verde, primitivo, cocoquí, and yurchumo. The Yurchumo variety is very similar to the chopo verde. Yurchumo is a Bribri word that in Spanish means banana from the river. We also have one that is very similar to congo, but it is not, and I got it from… well, I can’t remember. But that information is not important; the point is that we have it here. We also have the cuadrado and filipita. The cuadrado is an ancient type of banana, and the filipita recently arrived into the community. There are many plantains too, but we don’t have them all. We have the common one, the small one - one for patacones (fried banana)-. The newest one is producing very large plantains, and the fruits are heavy. I don’t know how this plantain ended up in Yorkin. I believe one neighbor brought it from Las Delicias (Panama). There used to be a small dominico, but I haven’t seen it in a long time. Conversation with Don Cirilo (Rodríguez field notes July 29, 2016)

In Talamanca, the Gros Michel banana variety has been produced since 1900 by corporate agricultural enterprises, as well as by small-scale farmers (Boza Villarreal 2014). Before 1920, the Chiriqui Land Company, a subsidiary of the United Fruit Company (UFCo), occupied the traditional lands of the Bribri Indigenous people to produce bananas in monocultures and export them to several countries in North America and Europe (Marquardt 2001).

In 1916, the UFCo realized that their plantations were affected by the Panama disease (Mal de Panama in Spanish) (Marquardt 2001). The Panama disease is a pathogen that infects Gros Michel bananas (Waller and Brayford 1990). The origin of the pathogen is unknown but widely believed to be from Central America. It quickly spread to other countries because of the substantial movement of workers and tools throughout the UFCo operations (Marquardt 2001).

The UFCo tried controlling the Panama disease by using several strategies. For example, it (1) invested in creating drainage infrastructure, (2) flooded infected soils, (3) changed the acidity of the soils, and (4) expanded its operations into forestry areas (Marquardt 2001). None of these management strategies were successful and the UFCo closed its operations in Talamanca in the late 1920s (Boza Villarreal 2014). Some of the workers who lost their UFCo jobs decided to stay in the region, married Bribri women, and became commercial agroforesters.

During this reorganization, the livelihood of the Yorkin residents was a combination of the Bribri subsistence and the ex-UFCo workers’ economic practices (Rodríguez and Davidson-Hunt 2018). According to the interviewees, the livelihoods of the Yorkin households relied on Bribri resource management such as hunting (Mazama americana, Ramphastos sp., Tayassu tajacu), fishing (Joturus pichardi, Sicydium spp.), harvesting (Licania platypus, Phytolacca rivinoides) local resources, and growing several types of bananas in agroforestry systems (Table 2). The livelihoods of the Yorkin households relied as well on the new residents’ agricultural practices that consisted of growing different landraces of rice (Oryza sativa L.) in swidden plots. The consumption of rice, several types of bananas, plantains, and other plants became an essential part of the interviewee’s livelihoods after the UFCo ceased its operations in Talamanca (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of plants and animals used by the Yorkin residents after the withdraw of the UFCo. This list was generated by analyzing the life history interviews applied to 14 community members. The species marked with (*) were shared by the Panamanian residents to Yorkin

| English names | Spanish names | Bribri names | Scientific names | Use | Presence in the community in 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice* | Arroz | - | Oryza sativa L. | Food | Yes |

| Banana | Banano | Mát | Musa acuminata Colla | Food | Yes |

| Bobo mullet | Bobo | Namà ichö́́k | Joturus pichardi Poey | Food | Yes |

| Cocoa | Cacao | Tsuru’ | Theobroma cacao L. | Food | Yes |

| Coffee* | Café | Kápi | Coffea arabica L. | Food and trade | Yes |

| Squash | Calabaza | Mè | Cucurbita sp. | Food | Yes |

| Shrimp | Camarón | Só | Cryphiops spp. | Food | Yes |

| Sugarcane* | Caña de azucar | Páköl | Saccharum officinarum L. | Food | Yes |

| Pig | Chancho | Kö̀̀chi | Sus sp. | Food and trade | Yes |

| Collard peccary | Chancho de monte | Kásir’ | Tayassu tajacu L. | Food | Yes |

| Nettle flower | Ortiga (flor) | Sànalwö (para ortiga) y para flor: chi’ | Urera baccifera (L.) Gaudich. ex Wedd. | Food | Yes, but the flower is not consumed |

| Beans | Frijol | Átu | Phaseolus vulgaris L. | Food | Yes |

| Hens | Gallinas | Krò | Gallus sp. | Food | Yes |

| Rubber tree | Hule | Tsìni |

Castilla elastica Sessé ex Cerv |

Food and trade | Yes, but it is not currently harvested |

| Corn | Maíz | Ikuwö̀ | Zea mays L. | Food | Yes |

| Central American Agouti | Ñeque | Shulë̀̀ | Dasyprocta punctate Gray | Food | Yes, but it is not consumed |

| Peach palm | Pejibaye | Dikó | Bactris gasipaes Kunth | Food | Yes |

| - | Platanilla | Ppṍ | Heliconia sp. | Food | Yes |

| Plantain | Plátano | Kalö́́m | Musa acuminata Colla | Food | Yes |

| Fiddleheads | Rabo de mono | Shpö́́ | Cyathea sp. | Food | Yes |

| Atlantic grunt | Ronco | Sichík | Pomadasys crocro Cuvier | Food | Yes |

| - | Titi | Nés | Sicydium spp. | Food | Yes |

| Adlay | Trigo | - | Coix lacryma-jobi L. | Food | Yes |

| Toucan | Tucan | Tsíö | Ramphastos sp. | Food | Yes, but it is not consumed |

| Red Brocket | Cabro de monte | Sülï mát | Mazama americana Erxleben | Food | Yes |

| Cassava | Yuca | Ali’ | Manihot esculenta Crantz | Food | Yes |

| - | Cabeza de mono | - | Licania platypus (Hemsl.) Fritsch | Food | Yes |

| Venezuela Pokeweed | Calalú | - | Phytolacca rivinoides Kunth & C.D. Bouché | Food and medicine | Yes |

In the early 1990s people started to produce plantains and bananas to compensate for reduced cacao income due to monilia. People decided to grow plantains because intermediaries from Nicaragua were buying the product. Also, the Wilombe Foundation supported Bribri farmers to create a cooperative to market two banana varieties, and new buyers arrived into the area. Since then, the Bribri people of Yorkin have produced plantain, the banana Gros Michel and the banana Lacatan. The Lacatan banana is a variety resistant to Panama disease and was introduced to solve the problem of this pathogen (Marquardt 2001). However, the Lacatan banana, as well as the plantain, are affected by the Black Sigatoka disease.

The Black Sigatoka is a fungal disease caused by M. fijiensis M. Morelet. This disease was first reported in Fiji in 1963 and has spread in the last 55 years to several countries worldwide (e.g., Tahiti, Hawai’i, Bhutan). In Latin America, the fungus has been reported in Guatemala, Belize, Mexico, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia (Arango-Isaza et al. 2016). It is believed that the movement of infected plants throughout banana farms, as well as the spread of spores by wind, disseminates the Black Sigatoka fungus (Mourichon et al. 1997).

People responded to the impact of the Sigatoka fungus in diverse ways. In the case of the plantain, which is usually grown in monocultures along the shores of rivers and creeks, people have tried to control the disease by using two types of fungicide: propiconazole and difenoconazole (Polidoro et al. 2007). However, not all the farmers use them as they are relatively expensive. This is the main reason why people stopped growing plantains for commercial purposes in the 1990s. Other reasons mentioned by the interviewees included land erosion, lack of access to buyers, and peoples access to banana buyers. The production of plantains started again around 2010 as new buyers from Panama arrived in the area. Yorkin residents like to grow plantain as the price is higher than the price for cacao beans or banana. Yet, the number of people engaged in the commercialization of plantain in the first semester of 2015 was approximately three times lower than the number of people selling bananas during the same period of time (Rodriguez field notes October 14, 2015).

In the banana case, buyers had suggested using compost and other techniques to control the fungal pathogen (Rodríguez field notes December 9, 2015). People in Yorkin have not adopted these practices; instead, they have opted to use their knowledge to manage the incidence of the Sigatoka disease. This included building drainage systems in each plot, cleaning their tools before and after they work in the plots, and starting new plots when the ones they are using are infected (Table 3). Intercropping bananas and cacao in the same area has also been a strategy to manage the pathogen and to supplement livelihoods. In the latter case, people not only keep the commercial varieties of bananas and plantains but also other customary cultivars that allow them to satisfy their household food needs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Musa varieties and local management practices documented in the study area

| Spanish and folk names | Bribri names | Number of households with varieties (N = 11) | Uses | Management practices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banano Chopo Morado | Mát | 3 | Subsistence. Consumed cooked (grilled) |

For all banana varieties: Intercropping banana other plant species in the same area Weeding & pruning practices (e.g., (removal of infected plants) Additionally, for commercial varieties (Banano Gros Michel and Lacatan): Disinfection of tools with chlorine Disinfection of shoots planted with limestone Construction of draining systems |

| Banana Chopo Verde | Mát | 4 | Subsistence. Consumed cooked (boiled) | |

| Banano Cocoqui | 3 | Subsistence. Consumed cooked. It is used to make “picadillo.” Picadillo is a dish made with chopped vegetables mixed with banana | ||

| Banano Cuadrado | Shòo | 8 | Subsistence. Consumed cooked (boiled and fried). It can also be dried, grind, and used to prepare beverages | |

| Banano Congo | Chãmu | 4 | Subsistence. Consumed cooked (boiled) | |

| Banano Manzano | 1 | Subsistence. Consumed fresh. It needs to be ripe | ||

| Banano Primitivo | 7 | Subsistence/consumed cooked (boiled and fried) | ||

| Banano Chirique | 0 | Subsistence/consumed fresh and cooked, delicate flavor/some people consider it plantain, other people consider it banana | ||

| Banano Gros Michel |

Chamù Surùri |

11 | Commercial and subsistence/consumed raw | |

| Banano Lacatan | 11 | Commercial and subsistence. Consumed fresh | ||

| Plantain Filipita | 2 | Subsistence/consumed cooked |

For all plantain varieties: Weeding & pruning practices (e.g., (removal of infected plants) Shade control (It does not require lots of shade) Additionally, for commercial varieties: Use of pesticides Crop rotation when the disease is not manageable |

|

| Plantain Tapona | 1 | Subsistence/consumed cooked | ||

| Plantain Azul/Morado | 0 | Subsistence/sweet and delicate flavor | ||

| Plátano Dominico | 1 | Consumed cooked (boiled and grilled). It has a delicate flavor. It is used to feed the household’s animals (pigs, hens, turkeys) | ||

| Plátano/Curaré | 11 | Commercial and subsistence/consumed cooked (boiled and grilled). It is used to prepare beverages. Since it is a tall plant, some residents use it to provide shade to cacao trees. The fruits are used to feed the household’s animals (pigs, hens, turkeys) |

The Bribri of Yorkin keep growing non-commercial banana and plantain cultivars for several reasons. The first reason is that these plants require little care. The second reason is that these cultivars produce large quantities of bananas that can be used to feed the hens and pigs raised by the households. Moreover, some cultivars produce fruits with a delicate and sweet flavor, making it an ideal fruit to complement the Bribri diet on a daily basis. Finally, the leaves of non-commercial Musas are used to provide shade to cacao, to get fibers (e.g., Musa textilis is locally used to make ropes and string fibers), and as wrappers. The use of cultural practices to manage the incidence of fungal pathogens in the banana farms has allowed Yorkin farmers to obtain organic certification, and to sell their products on the international market. In 2015, households in Yorkin were selling between 20 and 520 kg of banana biweekly (Rodriguez field notes October 14, 2015). In 2016, around 46 households were selling on average 10 000 kg of banana biweekly to two of the three main intermediaries buying banana in the community (Rodríguez field notes July 4, 2016). The income received in 2016 by the producers was US$ 0.11 per banana kg (Rodríguez field notes July 4, 2016) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Social–ecological memory involved in the cacao case and banana and plantain case, indicating the reservoirs of SEM, the mobile links involved, and the legacies

Discussion

Focusing on cacao, banana, and plantain of the Bribri, and the impact of fungal pathogens on them, we find resilient agroforestry systems that change in a cyclic way and persist. Given the rapid change in biodiversity and the environment, and the ever-increasing pace of fungal pathogen invasions in tropical agricultural lands (Mace et al. 2005), it is important to identify and nurture sources of resilience that enable these systems to persist (Folke et al. 2005).

Using the resilience concept of SEM helps understand how the people react to changes: first by using their own knowledge, and second by learning from the outside, often through their social networks. The dynamic interactions of legacies and reservoirs that serve as a repository of choices have provided for the Bribri the potential for re-organization following the impact of fungal diseases on their crops. The continuous use of some crop varieties, such as the criollo ones and non-commercial ones, seems to be sustained, among other factors, by (1) the knowledge to produce these plants in agroforestry systems, (2) the knowledge to control the incidence of fungal pathogens (with cultural practices), and (3) the knowledge to transform these plants into food for the table (e.g., fried, grilled plantains, chocolate beverages) (Table 3), medicines (e.g., cacao butter) and food for animals (several types of bananas and plantains) (Table 3). The accumulated experience and history of ecosystem management collectively held by the community (Barthel et al. 2010), have allowed the Bribri to use their biocultural diversity to respond to a complex, unpredictable and variable environment.

Second, the Bribri have also responded to the changing environment by drawing on the “archived memory” of other communities, “to the extent of copying” (Nazarea 2006), and the use of the biodiversity located outside the immediate borders of Yorkin. These responses have included:

the adoption of new management practices (e.g., grafting) and new crop varieties (e.g., cacao hybrids and several types of banana and plantain, see Tables 1, 3) to enrich their agroforestry systems through their networks with other Bribri groups, and non-Bribri people from other communities (e.g., Panama), as well as with associations/foundations, and research institutes;

the adoption and substitution of new biological species for other plants with similar characteristics. Species that were not needed for cash income during certain periods (e.g., banana Gros Michel) became significant after the impact of disturbance such as the monilia, demonstrating the idea that particular species that seem ecologically unimportant may become important following a disturbance (Holling et al. 1995; Sylvester et al. 2016).

The use of biodiversity richness in Yorkin has been continuous but also flexible (Rodríguez and Davidson-Hunt 2018). As our data show, for example, the Bribri have relied on cacao, which diminished due to new pathogens but then when responses were found to those pathogens, they turned to cacao again. Likewise, with plantain. The use of some biological species varies over the years (Rodríguez and Davidson-Hunt 2018). The SEM associated with specific biological resources are not fixed in time but are emergent from the environment where people live and continuously make an agricultural livelihood for families and communities.

Measuring the use of a particular species at a point in time and comparing that to use in the past does not account for the possibility of future use from the legacies and reservoirs of biodiversity (Davidson-Hunt et al. 2016). Bribri knowledge is not a diminishing resource but one that is actively being produced over time (Rodríguez and Davidson-Hunt 2018). In this regard, the concept of SEM is silent on the agency of people in elaborating new knowledge, institutions, and relationships. The potential for using SEM in responding to environmental change should not just focus on what is being used at a given point in time. We should also pay attention to the access and availability that people have to their reservoirs of SEM transmitted across generations (e.g., Cristancho and Vining 2009; Calvet-Mir et al. 2015), as well as the reservoirs of knowledge of their neighbors (species and management knowledge shared through different mobile links: neighbors, associations/foundations, and networks in general) (Turner et al. 2003; Crona and Bodin 2006; Barthel et al. 2010), and the creativity of people to solve problems by accessing these legacies and reservoirs.

Use of biodiversity emerges through creative responses of people as they experience dynamic environments and pursue their livelihoods. By considering how the Bribri people of Yorkin have responded to biodiversity change, we find some loss (e.g., absence of some banana/plantain cultivars within the community, see Table 2) but also an active and intentional reconfiguration in the use of biodiversity.

Conclusion

Using resilience thinking and the concept of SEM, we have focused on how Bribri people draw upon their knowledge saved in their collective memory and external reservoirs (including networks) in their responses to pathogens in their commercial crops. Biodiversity is continuously changing, and new fungal pathogens in Bribri agroforestry systems appear from time to time and require creative responses. As people rely more and more on specific crops, as crop densities increase, and as the genetic variability of commercial crops decreases, agricultural systems become more susceptible to disease outbreaks, affecting livelihoods (Zimmerer 2010). It is important to keep in mind both the potential of SEM and the factors that may reduce its potential use over time as a source of creative responses to biodiversity change.

The study of Yorkin residents’ SEM illuminates our understanding of how people respond to biodiversity change. Our results suggest that SEM is a dynamic process through which biological resources, and people’s traditional knowledge, practices, values, and skills (legacies), and when needed their networks (to access reservoirs of outside knowledge), are creatively used to respond to an ever-changing environment. Yorkin responses to biodiversity change are nonlinear and complex, enabling them to stay resilient and not to abandon their farms. Resilience in this case includes people’s capacity to resist, or to adapt, and/or to transform their social–ecological systems, depending on the circumstances (Béné et al. 2014).

Understanding people’s responses to biodiversity change in a specific context is vital, as changes are expected to accelerate in the future (Mace et al. 2005). Insights from SEM in Yorkin indicate that the protection of preferred species (criollo, non-commercial plants, and commercial plants), diversification processes (growing different banana, plantain, and cacao germplasm), and networks that provide access to new species and management practices, are all crucial. This approach has allowed Bribri people in Yorkin to respond to the impact of pathogens and sustain their livelihoods. Use of the SEM concept extends the understanding of IK and allows us to consider how other peoples’ memory and landscapes act as reservoirs of SEM, and how linkages (mobile links) allow biological materials and associated information from a reservoir to become part of IK and, through this process, become a legacy for future generations. Given potential future challenges from biodiversity change, more engagement is needed across literature studies considering knowledge and adaptation and the possible contribution that using an analytical framework like SEM can provide in supporting community responses.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Bribri people that participated in this research. Especial thanks to Ali García who supported this research with the Bribri names of the biological species reported in this paper. This work was carried out with the aid of a Doctoral Fellowship awarded to Rodriguez Valencia from the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (Conacyt 209590/313551), by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Awards 435-2015-1478 and 410-2010-1817 (PI Davidson-Hunt), and the Canada Research Chairs Program (Berkes).

Biographies

Mariana Rodríguez Valencia

is a Doctoral Candidate at the Natural Resources Institute of the University of Manitoba. Her research interests include the study of human–environment relationships with a focus on ethnobiology, resilience thinking, and biocultural design.

Iain Davidson-Hunt

is an Associate Professor at the Natural Resources Institute of the University of Manitoba. His research interests include ethnobotany, ethno-ecology, and biocultural design.

Fikret Berkes

is Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the Natural Resources Institute, University of Manitoba. His research interests include community-based resource management and social–ecological resilience.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mariana Rodríguez Valencia, Phone: 204-474-8373, Email: rodrig13@myumanitoba.ca.

Iain Davidson-Hunt, Phone: 204-474-8373, Email: iain.davidson-hunt@umanitoba.ca.

Fikret Berkes, Phone: 204-474-6731, Email: fikret.berkes@umanitoba.ca.

References

- Arango-Isaza R, Diaz-Trujillo C, Dhillon B, Aerts A, Carlier J, Crane C, Jong T, Vries I, et al. Combating a global threat to a clonal crop: Banana Black Sigatoka pathogen Pseudocercospora fijiensis (synonym Mycosphaerella fijiensis) genomes reveal clues for disease control. PLoS Genetics. 2016;12:e1006365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthel S, Folke C, Colding J. Social–ecological memory in urban gardens—Retaining the capacity for management of ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change. 2010;20:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bateson G. Steps to an ecology of mind; collected essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution, and epistemology. San Francisco: Chandler Pub. Co.; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Béné C, Newsham A, Davies M, Ulrichs M, Godfrey-Wood R. Resilience, poverty and development. Journal of International Development. 2014;26:598–623. doi: 10.1002/jid.2992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berkes F. Sacred ecology. 4. London: Routledge; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes F, Folke C, editors. Linking social and ecological systems. Management practices and social mechanisms for building resilience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Oxford: Altamira Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Borge, C., and V. Villalobos. 1994. Talamanca en la encrucijada [Talamanca at the crossroads]. San José: Universidad Estatal a Distancia (in Spanish).

- Borge, C. 2011. El policultivo indígena de Talamanca y la conservación de la naturaleza [The indigenous polyculture of Talamanca and the conservation of nature]. San José: Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (in Spanish).

- Boza Villarreal, A. 2014. La frontera indígena de la gran Talamanca:1840–1930 [The indigenous frontier of the great Talamanca: 1840–1930]. Cartago: Editoriales Universitarias Públicas Costarricenses (in Spanish).

- Brannen J. Life story talk: Some reflections on narrative in qualitative interviews. Sociological Research Online. 2013;18:15. doi: 10.5153/sro.2884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calvet-Mir L, Riu-Bosoms C, González-Puente M, Ruiz-Mallén I, Reyes-García V, Molina J. The transmission of home garden knowledge: Safeguarding biocultural diversity and enhancing social–ecological resilience. Society and Natural Resources. 2015;29:1–16. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2015.1094711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa Rican Census. 2011. Características Sociales. Población total en territorio indígena, auto identificación étnica, lengua indígena, pueblo, territorio indígena; [Social characteristics. Total population in the indigenous territory, self-identification, indigenous language, people, indigenous territory]. http://www.inec.go.cr/sites/default/files/documentos/inec_institucional/estadisticas/resultados/repoblaccenso2011-12.pdf.pdf. Accessed 22 Aug 2018 (in Spanish).

- Creswell J. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. London: SAGE; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristancho S, Vining J. Perceived intergenerational differences in the transmission of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) in two indigenous groups from Colombia and Guatemala. Culture and Psychology. 2009;15:229–254. doi: 10.1177/1354067x09102892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crona B, Bodin Ö. What you know is who you know? Communication patterns among resource users as a prerequisite for co-management. Ecology and Society. 2006;11:7. doi: 10.5751/es-01793-110207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson-Hunt IJ, Berkes F. Journeying and remembering: Anishinaabe landscape ethnoecology from northwestern Ontario. In: Johnson LM, Hunn ES, editors. Landscape ethnoecology: Concepts of biotic and physical space. New York: Berghahn Books; 2010. pp. 222–239. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson-Hunt I.J., Suich H., Meijer S.S., Olsen N., editors. People in nature: Valuing the diversity of interrelationships between people and nature. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- De Leon JP, Cohen JH. Object and walking probes in ethnographic interviewing. Field Methods. 2005;17:200–204. doi: 10.1177/1525822x05274733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folke C, Colding J, Berkes F. Synthesis: Building resilience and adaptive capacity in social and ecological systems. In: Berkes F, Colding J, Folke C, editors. Navigating social–ecological systems. Building resilience for complexity and change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 352–387. [Google Scholar]

- Folke C, Hahn T, Olsson P, Norberg J. Adaptive governance of social–ecological systems. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 2005;30:441–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson LH, Holling CS, editors. Panarchy: Understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Holling CS, Schindler DW, Walker BW, Roughgarden J. Biodiversity in the functioning of ecosystems: An ecological synthesis. In: Perrings CA, Mäler KG, Folke C, Holling CS, Jansson BO, editors. Biodiversity loss: Economic and ecological issues. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 44–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold T. The perception of the environment: Essays in livelihood, dwelling and skill. London: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Meteorológico Nacional, IMN. 2016. Boletín meteorológico [Weather bulletin]. https://www.imn.ac.cr/27. Accessed 5 Dec 2017 (in Spanish).

- Kim G, Vaswani RT, Lee D. Social–ecological memory in an autobiographical novel: Ecoliteracy, place attachment, and identity related to the Korean traditional village landscape. Ecology and Society. 2017;22:27. doi: 10.5751/es-09284-220227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leichenko R, O’Brien KL. Environmental change and globalization: Double exposures. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mace G, Masundire H, Baillie J, Ricketts T, Brooks T, Hoffmann M, Stuart S, Balmford A, et al. Biodiversity—Current sate and trends: Findings of the Condition and Trends Working Group. Ecosystems and human well-being. Millennium ecosystem assessment. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt S. “Green havoc”: Panama disease, environmental change, and labor process in the central American banana industry. American Historical Review. 2001;106:49–80. doi: 10.2307/2652224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt L, Rincones J, Bailey B, Aime M, Griffith G, Zhang D, Pereira G. Moniliophthora perniciosa, the causal agent of witches’ broom disease of cacao: What’s new from this old foe? Molecular Plant Pathology. 2008;9:577–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2008.00496.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourichon, X., J. Carlieret, and E. Foure. 1997. Sigatoka leaf spot diseases. https://www.bioversityinternational.org/fileadmin/user_upload/online_library/publications/pdfs/699.pdf. Accessed 1 Aug 2018.

- Nazarea VD. Local knowledge and memory in biodiversity conservation. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2006;35:317–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nykvist B, Von Heland J. Social–ecological memory as a source of general and specified resilience. Ecology and Society. 2014;19:47. doi: 10.5751/es-06167-190247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Mora, W. 2003. Origin, biogeography, genetic diversity and taxonomic affinities of the cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) fungus Moniliophthora roreri (Cif.) Evans et al. as determined using molecular, phytopathological and morphophysiological evidence. PhD Thesis. University of Reading, Reading.

- Phillips-Mora, W., A, Arciniegas-Leal, A. Mata-Quirós, and J.C. Motamayor-Arias. 2012. Catalogo de clónes de cacao seleccionados por el CATIE para siembras comerciales [Catalog of cocoa clones selected by CATIE for commercial fields]. http://www.worldcocoafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/files_mf/phillipsmora2012clones4.64mb.pdf. Accessed 8 Aug 2016 (in Spanish).

- Phillips-Mora W, Wilkinson MJ. Frosty pod of cacao: A disease with a limited geographic range but unlimited potential for damage. Phytopathology. 2007;97:1644–1647. doi: 10.1094/phyto-97-12-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polidoro BA, Dahlquist RA, Castillo LE, Morra MJ, Somarriba E, Bosque-Pérez. NA. Pesticide application practices, pest knowledge, and cost–benefits of plantain production in the Bribri–Cabécar Indigenous Territories, Costa Rica. Environmental Research. 2007;108:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez M, Davidson-Hunt IJ. Resilience and the dynamic use of biodiversity in a Bribri Community of Costa Rica. Human Ecology. 2018;46:923–931. doi: 10.1007/s10745-018-0033-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stone, D. 1961. Las tribus talamanqueñas de Costa Rica [The Talamanca tribes of Costa]. San José: Editorial Antonio Lehmann (in Spanish).

- Sylvester O, Segura AG, Davidson-Hunt IJ. Wild food harvesting and access by household and generation in the Talamanca Bribri Indigenous Territory, Costa Rica. Human Ecology. 2016;44:449–461. doi: 10.1007/s10745-016-9847-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner NJ, Davidson-Hunt IJ, O’Flaherty M. Living on the edge: Ecological and cultural edges as sources of diversity for social–ecological resilience. Human Ecology. 2003;31:439–461. doi: 10.1023/A:1025023906459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B, Holling CS, Carpenter SR, Kinzig A. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society. 2004;9:5. doi: 10.1103/physrevlett.95.258101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waller J, Brayford D. Fusarium diseases in the tropics. Tropical Pest Management. 1990;36:181–194. doi: 10.1080/09670879009371470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson G, Kelly CL, Briassoulis H, Ferrara A, Quaranta G, Salvia R, Detsis V, Curfs M, et al. Social memory and the resilience of communities affected by land degradation. Land Degradation and Development. 2017;28:383–400. doi: 10.1002/ldr.2669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young A. The chocolate tree: A natural history of cacao. Gainesville: University Press of Florida; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerer KS. Biological diversity in agriculture and global change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 2010;35:137–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-040309-113840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerer KS, Carney JA, Vanek SJ. Sustainable smallholder intensification in global change? Pivotal spatial interactions, gendered livelihoods, and agrobiodiversity. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 2015;14:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2015.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]