Abstract

This study examines the association between sibship size and wealth in adulthood. The study draws on resource dilution theory and additionally discusses potentially wealth-enhancing consequences of having siblings. Data from the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP, N = 3502 individuals) are used to estimate multilevel regression models adjusted for concurrent parental wealth and other important confounders neglected in extant work. The main results of the current study show that additional siblings reduce wealth by about 38%. Parental wealth moderates the association so that sibship size is more negatively associated with filial wealth when parents are wealthier. Birth order position does not moderate the association between sibship size and wealth. The findings suggest that fertility in the family of origin has a systematic impact on wealth attainment and may contribute to population-level wealth inequalities independently from other socio-economic characteristics in families of origin such as parental wealth.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10680-018-09512-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Siblings, Wealth, Family of origin, Resource dilution

Introduction

The role of the sibship configuration, including aspects such as sibship size (i.e. the number of siblings) and birth order, for attainment processes throughout the life course has been studied since the nineteenth century (Galton 1874) and remains a contentious issue today (Black et al. 2010; Gibbs et al. 2016; Härkönen 2014; Jacob 2011). Questions of whether and how sibship size and other aspects of the sibship configuration may shape individuals’ life chances are important to address to understand the interplay between demographic processes and intra- and intergenerational processes of social stratification (Steelman et al. 2002). For instance, larger sibship sizes may be associated with lower economic wealth attainment—where wealth is the total amount of material possessions such as savings, investments, real estate and cash, less any debts and loans—as wealth directly and indirectly transferred from the parental generation is spread more thinly in larger sibships. This may have important long-term consequences for population-level wealth inequality if families with small sibship sizes can more successfully transmit their concentrated wealth across generations (Hansen 2014; Lawson et al. 2013). To understand whether having more siblings is associated with less wealth in adulthood is the central objective of the present study.

Previous studies examined sibship size and wealth, and they found negative associations [for the most comprehensive studies, see Keister (2003, 2004); Parr (2006)]. Further study of this association is justified because of empirical limitations and important gaps in current knowledge. First, it is important to re-assess the association between sibship size and wealth, because of potential omitted variable bias in prior studies. To this end, data for the current study are drawn from the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP), which includes parents and children who live in separate households. This allows examining the association between sibship size and wealth for adult children, while controlling for important characteristics in the parental generation, such as the concurrent parental wealth and psychological characteristics, which have been mostly unobserved in prior research. In particular, parental wealth can be expected to be an important confounder. Wealthier parents may be less likely to have more children leading to a spurious relationship between sibship size and wealth.

Second, the current study contributes empirically to the literature, which is almost exclusively focussed on the USA, by adding evidence from Germany as a new institutional context. Germany is a low-fertility country with relatively generous family policies. In this context, the association between sibship size and children’s wealth may be weaker than in the USA.

Third, it is not well understood whether having additional siblings is universally harmful to wealth attainment. The current study is the first to examine how the relationship between sibship size and wealth varies by parental wealth and birth order. Examining variation by parental wealth is important to understand how between-family inequality in wealth is shaped by family size. Examining variation by birth order is relevant to understand how within-family wealth inequality between siblings may arise in differently sized families.

Fourth, previous studies mainly examined linear associations between sibship size and wealth. In these studies, the expectation was that each additional sibling similarly reduces wealth. Based on resource dilution theory and prior research on positive outcomes of having siblings, however, this expectation may be overly simplified. The present study derives new expectations based on relevant theory and scrutinizes potential nonlinearity in the association between sibship size and wealth. Taken together, these contributions help to better understand if and for whom more siblings may reduce wealth attainment.

In the next sections, previous studies are briefly reviewed and resource dilution theory is discussed together with alternative theoretical perspectives on the wealth-enhancing consequences of having siblings to derive several hypotheses. The SOEP data are analysed with multilevel regression models to test these hypotheses. In the analysis, it is found that additional siblings reduce wealth by about 38%. Sibship size is more negatively associated with filial wealth when parents are wealthier. Birth order position is negatively associated with wealth, but does not moderate the association between sibship size and wealth. Most results remain robust to a range of alternative model specifications. Finally, the implications of these findings are discussed.

Background

Previous Empirical Evidence and Its Limitations

A number of studies have examined the association between sibship size and wealth in adulthood—albeit often in passing using sibship size as a control variable (see Table 1 for an overview). These studies mostly find larger sibship sizes to be linearly negatively associated with wealth. However, the studies have important limitations. First, previous studies mostly only control for few parental characteristics such as occupational status and income during respondents’ childhood. They mostly do not directly control for parental wealth and other parental characteristics such as risk preferences, which may simultaneously affect fertility and filial wealth (Brown et al. 2013; Donkers and van Soest 1999; Jokela 2014; Schmidt 2008). Furthermore, previous studies in most cases do not account for other aspects of sibship configuration such as birth order position, which may be conflated with sibship size (Black et al. 2005; Rodgers et al. 2000). Taken together, these empirical limitations may result in a serious overestimation of the association between sibship size and wealth in prior studies. At the same time, previous studies often include a wide range of adult children’s characteristics such as education and marital status, many of which can be expected to mediate the effect of having siblings on wealth. This may lead to an underestimation of the sibling effect on wealth by over-controlling intervening mechanisms.

Table 1.

Previous evidence on the association between sibship size and wealth

| Study | Country (data) | Outcome | Linear sibship size coefficient | Controlled for parental resources and parental psychological characteristics | Controlled for sibship configuration | Controlled for intervening mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hansen (2014) | Norway (register data) | Being in top 1% in wealth distribution | − 0.06 (logit) | Parents’ wealth | No | No |

| Keister (2003) | USA (NLSY 1979) | Net household wealth (started log) | − 2.71 | Family income, parents’ education | No | Yes |

| Keister (2004) | USA (NLSY 1979) | Net household wealth (started log) | − 3.76 | Family income, parents’ education | No | Yes |

| Keister (2007) | USA (NLSY 1979) | Net household wealth (started log) | − 3.63 | Parents’ income, parents’ education, parents worked full-time | No | No |

| Keister (2008) | USA (NLSY 1979) | Net household wealth (raw) in USD 1000 (?) | − 2.37 | Parents’ income, parents’ education | No | Yes |

| Killewald (2013) | USA (PSID) | Net household wealth (log with replacement for negative values and 0) | − 0.09 | Parents’ income, parents’ education, welfare receipt, parents’ occupational prestige, parents’ wealth | No | Yes |

| Parr (2006) | Australia (HILDA) | Net household wealth (raw) in AUD |

Women: − 16,702 Men: − 16,659 |

Mother’s occupation | Whether eldest sibling | Yes |

| Yamokoski and Keister (2006) | USA (NLSY 1979) | Net household wealth (raw) in USD 1000 | Women: − 2.27 | Family income, parents’ education | No | Yes |

I report the coefficient from the most comprehensive (but if possible without controls for intervening mechanisms) multivariate model excluding interactions. All studies use linear specifications for sibship size

Second, previous evidence is almost exclusively from the USA a context with relatively high fertility and limited public support for families (Park 2008). These contextual conditions may amplify associations between sibship size and children’s wealth. There are only two studies from outside the USA [on Australia Parr (2006) and Norway Hansen (2014)], which are limited as described above.

Third, it remains unclear whether additional siblings are universally harmful to wealth attainment and which conditions moderate the association between additional siblings and wealth to create within- and between-family inequality. Keister (2004) finds sibship size to be more negatively related to wealth attainment in non-poor families compared to poor families, where income poverty status is only a coarse proxy for parental wealth. No other research examined likely moderators such as parental wealth or birth order position.

Fourth, previous studies do not consider potential nonlinearity in the association between sibship size and wealth. The only exception is Keister (2004) who shows that the estimated negative effect of siblings decreases with larger sibships in non-poor families by testing a quadratic term for sibship size. This approach may conceal more complex nonlinearity in the association under study, however, in particular with regard to only children. At the descriptive level, Parr (2006) finds nonlinearity between the number of siblings and wealth, e.g. female only children have less wealth than women with one sibling, but the author does not further examine this nonlinear relationship in a multivariate framework.

Wealth Attainment

Wealth is accumulated from surplus income, i.e. incomes less consumption, and through wealth transfers, mostly from parents to their children. The relative importance of both sources of wealth is contested (Spilerman 2000), but during early stages of the life course surplus income can be expected to be more important for wealth attainment as large intergenerational wealth transfers through bequests mostly occur when recipients are older due to the long life expectancy in current parental generations (Charles and Hurst 2003). The family of origin may affect wealth attainment from surplus income beyond direct wealth transfers, however. For instance, the transmission of education across generations affects labour incomes in the offspring generation, which determines surplus income that may be saved (Charles and Hurst 2003). Because the current study mainly draws on a sample of relatively young respondents, wealth attainment from surplus income can be assumed to be the main source of wealth for these respondents. However, limited inter vivos transfers also occur in early adulthood, for instance at marriage (Leopold and Schneider 2011).

Sibship Size and Wealth Attainment: A Resource Dilution Perspective

The dominant theory to explain the effects of sibship size on attainment outcomes such as wealth or education is the resource dilution model (Anastasi 1956; Blake 1989: 10ff). Building on a human capital perspective, the basic assumption is that parental investment of resources such as attention and money produces positive outcomes in children, such as more wealth and higher educational attainment. Resource dilution theory argues that with increasing sibship size, finite parental resources are spread more thinly across siblings so that fewer resources can be invested which negatively affects children’s outcomes.

Resource dilution theory suggests that sibship size may affect wealth attainment from both sources, reduced savings from surplus income and reduced intergenerational financial transfers (Keister 2003), where the former can be expected to play a more important role in early phases of the life course. First, through exposure to diluted resources in families of origin during childhood and adolescence, educational attainment may be hampered, which leads to lower lifetime earnings and reduced savings. Empirical evidence supports a negative association between, on the one hand, sibship size and, on the other hand, cognitive ability and educational attainment (for an overview, see Steelman et al. 2002 and more recently Black et al. 2010; Gibbs et al. 2016). However, there are also null findings, in particular from studies using more advanced methods to account for endogeneity (Guo and Vanwey 1999; Workman 2017). The association between sibship size and education is also found to vary across countries, for instance, because education costs and family policies differ (Park 2008). There is only little empirical evidence for a negative association between sibship size and employment outcomes such as earnings (Angrist et al. 2010; Black et al. 2005), but even small earning differences may accumulate to substantial wealth differences over time. Additionally, lower educational attainment may also negatively affect wealth independent of income, because less education is associated with less successful financial investment strategies (Cavapozzi et al. 2011).

Second, with larger sibship size, smaller direct wealth transfers from parents to each child may occur over children’s life courses as the transfers are divided between more siblings (Keister 2003). Evidence shows that in most cases financial transfers are reduced with increasing sibship size. There is mixed evidence regarding within-family inequality in transfer receipt; some studies find equal receipt (e.g. Kalmijn 2013), while others find first-born children to be advantaged (Emery 2013). Unequal giving of parents is found to be more likely with large sibship size (Mechoulan and Wolff 2015).

Two nuances in the resource dilution model are relevant for the current study. First, not all resources may be equally diluted. Some resources such as parental wealth can be expected to be “more finite”, and thus more likely diluted, than other resources such as parents’ attention (Downey 1995). Downey (2001) additionally distinguishes base and surplus resources. Base resources include those necessary for survival such as food, while surplus resources are additional investments in children’s human capital such as reading to a child. In post-industrialized countries with developed welfare states, base resources are unlikely to be diluted.

Second, resource dilution may take different forms. Previous literature has often tested for linear relationships between sibship size and attainment outcomes. According to a strict reading of resource dilution theory, however, nonlinear dilution processes with decreasing marginal effects are more likely than linear relationships. For instance, comparing a family with one child to a family with two children, parental resources that can be invested into each child would be halved, but in a family with three children, one-third of parental resources may be invested. Such a nonlinear relationship may be particularly likely for “more finite” and dividable resources such as parental wealth (Downey 1995). However, social processes such as compensation strategies of parents may (partly) override such a strict resource dilution.

A nonlinear pattern may also arise because positive consequences of having siblings may counterbalance the negative consequences of sharing some resources with siblings (for a similar argument regarding health, see Baranowska-Rataj et al. 2016). These positive consequences are most likely to affect wealth attainment from surplus income rather than wealth transfers. Theoretical perspectives such as the confluence model (Zajonc and Markus 1975) suggest that only children may miss important developmental inputs from interacting with siblings.1 For instance, older siblings may benefit in their development from tutoring younger siblings (Härkönen 2014). While many aspects of the confluence model have been empirically rejected (Retherford and Sewell 1991; Steelman et al. 2002), there is some evidence that only children may have personality traits such as being less competitive and having fewer social skills that are negatively related to wealth attainment (Cameron et al. 2013; Downey and Condron 2004).

There are additional reasons to think that siblings may positively affect wealth attainment. For example, due to efficiency gains and because particular parental resources such as reading out loud can be considered public goods, additional siblings may have the counterintuitive consequence of increasing some resources for each sibling during childhood (Osmanowski and Cardona 2016). In addition, siblings increase the likelihood of getting married early and increase the stability of marriage (Angrist et al. 2010; Bobbitt-Zeher et al. 2016). Thus, those with siblings may be married for longer, which should positively affect wealth attainment (Wilmoth and Koso 2002)—although the negative selection of low socio-economic background couples into early marriage may run counter to this (Wiik 2009).

Generally, a partner in the household may positively contribute to wealth accumulation through shared investments such as homeownership that may be difficult to achieve as a single (Mulder and Wagner 1998). For women, the role of a partner may be more important than for men—at least in the gender-unequal context of Germany, where 32% of partnered women only earn up to 10% of the household income in 2006–2010 (Klesment and van Bavel 2017), on average—because women may (partly) benefit from their partners’ surplus income.

Between- and Within-Family Inequality in Resource Dilution and Wealth Attainment

The consequences of growing up with a larger number of siblings may be contingent on the resources available to the parents such as wealth, which may contribute to between-family inequality. There are two contrasting positions regarding the moderating role of parental wealth for resource dilution. First, it is argued that resource dilution may be weaker in wealthy families (Blake 1989: 67). There may be an upper limit to the benefits of investments into children. Wealthy families may be able to provide this limit for all their children. Thereby, the negative effect of large sibship sizes may be attenuated (Blake 1989: 88). Thus, sibship size may be most influential in less wealthy families, where investment remains below the limit of benefits (Phillips 1999).

Regarding wealth, it is questionable whether there is an upper limit to intergenerational wealth transfers, however, so that it is likely that resource dilution also occurs in wealthy families. Even more, resource dilution may be stronger in wealthy families (Lawson and Mace 2009). There is empirical evidence that sibship size is more negatively related to wealth attainment in non-poor families compared to poor families [based on family income: Keister (2004)]. These findings may be explained by considering base and surplus resources separately (Downey 2001). Relatively poor families may not be able to provide any surplus resources such as financial wealth. Only in families with surplus resources, these resources may be diluted leading to “floor effects” (Bernardi and Radl 2014: 1657) at the lower end of the wealth distribution.

Several studies show that family characteristics such as sibship size do not uniformly affect all children in the family contributing to within-family inequality (Conley and Glauber 2006; Hanushek 1992). In other words, children are in different positions to access scarce resources within the family. In particular, birth order position is an important aspect of the sibship configuration which may contribute to within-family inequality (Steelman et al. 2002). In general, first-born children have been found to do better on a number of outcomes such as educational attainment and earnings compared to later-born children (Black et al. 2005).

One explanation for this advantage is that first-born, and more generally earlier-born, children benefit from a period with less resource dilution before later-born children enter the family (Härkönen 2014; Iacovou 2008). This implies that negative effects of large sibships should be attenuated for earlier-born children compared to later-born children. Regarding wealth attainment, earlier-born children may have an advantage in their educational attainment in large sibships which increases their saving potential later in life. There is also evidence that earlier-born children receive inter vivos transfers from their parents more often (Emery 2013). However, while in the past unequal bequests at the death of the parents based on birth order were the norm, such inequality is very rare in modern societies (Lawson et al. 2013). Overall, advantages of earlier-born children may be amplified by reinforcing strategies of parents to maximize children’s outcomes (Becker and Tomes 1976; Grätz and Torche 2016).

There are also theoretical arguments for why later-born children may be advantaged. First, later-born (and in particular last-born) children may be less negatively affected by sibship size because they may benefit from their older siblings having left the parental household. Second, last-born children may benefit from their parents’ progress in their careers resulting in higher incomes (Iacovou 2008). Third, parents may aim to compensate for initial disadvantages of later-born children by adjusting their investments (Behrman et al. 1982; Grätz and Torche 2016). However, empirical evidence shows little advantage for later-born children (e.g. Black et al. 2005). One reason may be that even those siblings who have left the household may further drain relevant parental resources, e.g. if parents pay tuition fees or make inter vivos transfers.

Hypotheses

With regard to the association between the number of siblings and wealth in adulthood, the following hypotheses are derived. The first set of hypotheses is based on a strict reading of resource dilution theory and emphasizes the negative consequences of siblings on wealth. According to such a reading, I expect that additional siblings are generally negatively associated with individuals’ wealth in their adulthood (Dilution Hypothesis). Because of decreasing marginal effects predicted by resource dilution theory, I hypothesize that the negative association between additional siblings and net wealth tapers off with increasing sibship size, but remains significant even at large sibship sizes (Decreasing Effect Hypothesis). The next hypothesis, which partly competes with the previous two hypotheses, draws on the potentially wealth-enhancing consequences of having siblings. I expect that only children have less wealth compared to individuals with one sibling (Only Child Hypothesis). The last set of hypotheses deals with additional aspects of the association between the number of siblings and wealth. As wealth is a surplus resource, I expect that the association between additional siblings and wealth is more negative with more parental wealth (Parental Wealth Hypothesis). Earlier-born individuals may be less affected by large sibships, so that the negative association between the number of siblings and net wealth is more negative for later-born children (Birth Order Hypothesis). Thus, in the empirical part it will be first tested whether there is an association between sibship size and wealth and which form this association has accounted for parental characteristics. Then hypotheses about the variation in this association across families are tested.

While I expect the hypothesis to generally hold for both genders, the association between sibship size and wealth may vary to some degree because the underlying processes are not equally relevant for women and men. Because partnered women’s labour market participation remains limited compared to men in Germany (Trappe et al. 2015), women’s wealth accumulation may be less closely linked to their own employment. Instead, women wealth accumulation may be more closely linked to their partnership choices and, thereby, to the characteristics of their partners. It is noteworthy, however, that previous research has not found gender differences in intergenerational wealth transfers in Germany (Szydlik 2004).

German Context

The hypotheses are tested in the German context. Germany is among the lowest-fertility countries in the world. Since 1975, the total fertility rate was below 1.5 in West Germany. East Germany was characterized by higher fertility rates until reunification, but fertility rates in both parts of Germany had converged by 2008 (Goldstein and Kreyenfeld 2011). The total fertility rate has increased in the most recent years and has reached almost 1.6 in 2016 (Statistisches Bundesamt 2018). Education is mostly free in Germany reducing the direct costs of having children. The German educational system does not seem to moderate the consequences of sibship configuration for educational attainment (Härkönen 2014). Germany is a conservative welfare state centred on the family. Germany spent about 3.0% of GDP on family benefits (compared to 1.1 in US and 3.6 in Sweden) in 2013 (OECD 2017). Intergenerational wealth transfers between parents and children are only marginally taxed in Germany (Bach and Thiemann 2016). Wealth inequality is high in Germany (Gini of 0.76) in a European comparison (HFCN 2016), and there is marked inequality in wealth between women and men in Germany (Sierminska et al. 2010). Overall, these contextual factors, in particular lower fertility and weaker family support, may attenuate the relationship between sibship size and wealth compared to contexts such as the USA, but there is no reason to expect sibship size to be irrelevant in Germany [see, for instance, for negative sibship size effects on education in Germany Härkönen (2014); Jacob (2011)].

Data and Empirical Strategy

Data and Sample

Data are drawn from the Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP; version 33.1; 10.5684/soep.v33.1). The SOEP commenced in 1984 and is an ongoing, nationally representative, multi-purpose household panel survey for Germany (Wagner et al. 2007). The SOEP includes all members of a sampled household. Children that grow up in a sampled household are followed once they leave the parental home and from this point onwards the parental household and the child household are interviewed (genealogical design). The analysis combines wealth data from 2002, 2007 and 2012 waves of the SOEP with retrospective and prospective information about the total number of siblings of a respondent derived from all survey years from 1984 to 2016.2 For other analytical variables, the complete survey waves are used when possible.

Missing values are a concern in all studies of wealth (Riphahn and Serfling 2005). In the current sample, in about 32% of cases at least one wealth component of total net wealth is missing, which is comparable to other surveys such as the Panel Study of Income Dynamics [for 2007: 26% (Institute for Social Research 2015)]. For sibship size only 1% of cases have missing values. To maximize sample size, the data are multiply imputed under the assumption of missing at random (50 imputed sets; see Section 9.1 in Online Appendix for details on the imputation). Results are similar when excluding imputed values in the outcome variable (Table S.1 in Online Appendix).

Respondents aged 18–59 in private households are selected for the analysis if they were interviewed at least once in 2002, 2007 and/or 2012 and their parents also participated in the survey.3 Respondents living with their parents are excluded. Only very few respondents beyond age 59 have parents who are observed in the survey. The focal respondents examined in the analysis are relatively young (median age 33), because they must have been observed as children in the SOEP from 1984 onwards. (For instance, a 15-year-old child in a SOEP household in 1984 can be interviewed again in a separate household in 2002 at age 33.) Most previous studies, which are based on the NLSY 1979 data, have a similarly young sample. Because of their young age, respondents will have accumulated comparatively little wealth and will mostly not have received substantial wealth transfers (yet). In supplementary analysis further described below, older respondents are included at the cost of not directly observing their parents in the data. For the main analysis of younger respondents, 6388 observations from 3502 respondents nested in 2628 families are considered. For 642 families of origin (24%), more than one sibling is directly observed in the data.

Measures

The outcome variable is personal net wealth (see Table 2 for descriptive statistics). Personal net wealth is the sum of all wealth of an individual including real and financial assets, life insurances, private pension plans, business assets and valuable assets such as jewellery. I sum the total value of all these assets that an individual personally owns. For jointly owned assets, I sum the personally owned share of that asset. From this sum, individual assets, debts and loans and the personal share of joint liabilities are subtracted, so that respondents may have negative net wealth. An inverse hyperbolic sine (IHS) transformation is applied to adjust the positively skewed wealth distribution which includes negative and 0 values (Friedline et al. 2015). In a supplementary analysis, aggregate measures of household-level net wealth (the sum of personal wealth in the household) are examined (further discussed below). Arguably, sibship size should be more directly associated with personal than with household-level wealth.

Table 2.

Summary statistics

| M | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net wealth | 5.94 | 7.26 | − 14.57 | 16.13 |

| Sibship size | 1.84 | 1.38 | 0.00 | 6.00 |

| Birth order index | − 0.08 | 0.37 | − 0.85 | 0.82 |

| Close birth spacing (less than 2 years) | 0.27 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Mother’s age at birth of respondent | 26.64 | 5.51 | 14.00 | 49.00 |

| Sex composition of siblings | 0.51 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Any step siblings | 0.12 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Parental wealth | 10.59 | 5.20 | − 12.37 | 17.91 |

| Parents in homeownership | 0.66 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| At least one parent has university degree | 0.24 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Occupational status of parents (ISEI) | 45.81 | 16.36 | 16.00 | 90.00 |

| Parental risk preferences | 3.86 | 1.70 | 0.00 | 9.00 |

| Parental impulsiveness | 4.89 | 1.60 | 0.00 | 10.00 |

| At least one grandparent has university degree | 0.08 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Not lived with both parents until age 15 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| At least one parent died | 0.24 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Age (centred at age 18) | 15.98 | 8.33 | 0.00 | 41.00 |

| Women | 0.52 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Immigrant | 0.23 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Lived in East Germany in 1989 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| N Observations | 6388 | |||

| N Individuals | 3502 | |||

| N Families | 2628 | |||

Data: SOEP version 33.1 (2002, 2007, 2012); multiply imputed; unweighted

The main explanatory variable is sibship size which captures the total number of siblings individuals ever had. This variable is top-coded at six siblings, because of the very few number of respondents with more than six siblings. The variable will be used as a continuous and as a categorical variable to determine the appropriate specification for the association with wealth.

The moderator variable parental wealth captures the average observed net wealth (as described above) of both parents. If only one parent is observed, for instance because one parent has died, the single parent’s wealth is considered. Parental wealth is measured concurrent with the adult children’s wealth, because wealth has not been measured (comparably) in the SOEP before 2002. This is less than ideal, but I assume that concurrent parental wealth is a good proxy for parental wealth during childhood. Parental homeownership (1—yes, 0—no) captures whether parents are ever observed living in an owner-occupied home as another important aspect of parental wealth. The second moderator variable birth order index captures the birth order position of a respondent. The birth order index is constructed as the ratio of a respondents’ birth order positions relative to the average birth order positions in their sibships (Booth and Kee 2008).4 The variable is centred at 0. A higher value indicates a later birth order position. This index is orthogonal to sibship size and thereby avoids multicollinearity problems.

While the focus in the current study is on sibship size and birth order, other aspects of the sibship configuration are controlled for. To control for birth spacing, close birth spacing is a binary variable that equals 1 if any two siblings in the family are born within 2 years from each other, otherwise 0 (Powell and Steelman 1993). Age of mother at birth of respondent is used to capture the timing of fertility in the family of origin. Sibship sex composition indicates the share of men and women among all siblings. The variable ranges from 0 (only men) to 1 (only women). Any step siblings is a binary variable which is 1 if the respondent reports to have at least one step or half sibling, 0 otherwise. To capture the parental background (also during childhood) beyond parental wealth, the following variables are included: not lived with both parents until age 15 (yes—1; no—0), at least one parent died (yes—1; no—0), at least one parent has university degree (yes—1; no—0), highest occupational status of parents measured with the International Socio-Economic Index (ISEI) and at least one grandparent has university degree (yes—1; no—0). The concurrent risk preferences of parents and the impulsiveness of parents are also controlled for, as both psychological characteristics may be related to wealth accumulation and fertility at the same time.5,6 Both variables are based on 11-point scales, and values are averaged across observed time points and across mothers and fathers. Finally, all models are controlled for age and age squared, women (yes—1; no—0), immigrant (first and second generation; yes—1; no—0), lived in East Germany in 1989 (yes—1; no—0), survey year and origin of sample, but the related coefficients are not presented (Table S.2 in Online Appendix shows complete estimation results).

Empirical Strategy

Initially, the unadjusted, bivariate association between sibship size and wealth is examined. Then, the association between sibship size and wealth is modelled in a multivariable framework to formally test the hypotheses. For this, the appropriate specification for sibship size is tested by comparing a fully flexible specification of sibship size categories with a linear specification. I use the D3 statistics based on the likelihood ratio test for multiply imputed data suggested by Meng and Rubin (1992) to compare model fit. For the multivariable analyses, the following multilevel model for repeated observations of individuals nested within families is used to account for the hierarchical data structure:

where ytif is the net wealth of person i in year t from family f, which is transformed using an IHS function. α is the constant. is a vector of dummy variables capturing the sibship size or a linear term for sibship size, and are the related coefficients. Xif contains other characteristics of the sibship configuration including the birth order index as introduced above, Zif contains parental characteristics including parental wealth, and Wtif includes additional control variables such as age and period. uf is a random term at the level of families, and vif is a random term at the level of individuals. εtif is a random disturbance term across t, i and f. All random terms are assumed to be mutually independent, to have a mean of 0 and to be normally distributed. The model is estimated using full maximum likelihood within Stata’s “mixed” procedure (version 15.1). Heteroscedasticity–robust Huber–White standard errors are estimated (White 1980).

In the multivariable analysis, the coefficients in are used to test the Dilution Hypothesis, Decreasing Effect Hypothesis and Only Child Hypothesis about the association between sibship size and wealth. Models that exclude Xif (other characteristics of sibship configuration) and Zif (parental characteristics) are also presented to evaluate the importance of controlling for these variables. To test the Parental Wealth Hypothesis and the Birth Order Hypothesis about the moderation by parental wealth and birth order, respectively, these variables are interacted with the sibship size.

This multilevel regression only yields unbiased estimates of , the association between sibship size and wealth, under the assumption that uf, vif and εtif are not correlated with the number of siblings. Previous research has argued that most importantly parental wealth and psychological characteristics of parents may simultaneously affect the number of siblings and wealth (Keister 2003; more generally Sandberg and Rafail 2014). The current study is among the first to include a direct measure of concurrent parental wealth and additionally a measure of parental homeownership to rule out such a spurious association. In addition, risk preferences and impulsiveness of parents as two relevant psychological characteristics are controlled for. However, these parental characteristics are not measured during childhood of respondents in the current data. The potential bias induced by remaining unobservables (such as an effect of parental wealth during childhood that is not captured by concurrent parental wealth) may be addressed by instrumental variable regression using sibling sex composition or twin births as instruments in future research drawing on register data as has been done for other outcomes such as education or earnings in the past (Angrist et al. 2010; Black et al. 2005). In the context of the current study, this approach is not feasible as the sample size is too limited to estimate the model outlined above including instrumented variables with precision.7

A number of supplementary analyses are conducted for which results are presented following the main results. First, the model described above is re-estimated on a sample of respondents aged 18–79. For this sample including older respondents, direct measures of parental wealth and psychological characteristics are not available. These analyses help to investigate whether findings are sensitive to wealth transfers that may occur later in life. Second, instead of personal net wealth, an alternative measure of household net wealth is examined, which allows to probe whether household composition may contribute to the relationship between sibship size and wealth. Third, the main analyses are rerun stratified by gender to additionally test the hypotheses separately for women and men.

Results

Bivariate Results

Figure 1 shows the mean net wealth by sibship size. An omnibus test indicates that net wealth varies statistically significantly across sibship size categories at the 99.9% confidence level. The mean net wealth for only children is about 7.10 points on the IHS-transformed scale. With each additional sibling up to three siblings, net wealth decreases. The relationship seems largely linear. Those with one sibling have about 6.00 IHS-transformed points of wealth, which is statistically not significantly different from only children. Those with two siblings (5.49) have significantly less wealth compared to only children, but have similar wealth compared to those with one sibling. Those with three siblings have about 4.09 net wealth. The differences by sibship size then taper off and those with four or five siblings do not have less wealth than those with three siblings. The average wealth of those with six and more siblings is slightly higher than for those with five siblings, but the difference is statistically non-significant and the confidence interval becomes relatively large. Thus, the bivariate evidence suggests that having additional siblings is negatively associated with wealth, but the negative relationship seems to hold only up to having three siblings. However, only about 10% of individuals have more than three siblings.

Fig. 1.

Mean net wealth by sibship size. Data: SOEP version 33.1 (2002, 2007, 2012); multiply imputed; weighted. Note: Whiskers indicate 95% confidence interval; graph scheme provided by Bischof (2017)

Multivariate Results

Before further examining this relationship in a multivariable framework, I first compare the model fit of a linear specification with a flexible dummy specification of sibship size to evaluate the appropriate functional form of the relationship between the number of siblings and net wealth. The D3 statistic is negative (− 5.23) indicating that the model fit of the more parsimonious linear specification is to be preferred. Thus, the following analysis mostly focusses on the linear relationship between sibship size and net wealth, but I show additional evidence for a categorical sibship size indicator below.

Table 3 shows the estimation results from multilevel regression models for the outcome net wealth accounting for the hierarchical data structure. Model 1 uses a linear sibship size specification and only adjusts for general control variables such as age and period. In Model 2, other aspects of the sibship configuration such as birth order position are introduced to isolate the association with sibship size. These variables are jointly significantly related to individuals’ net wealth (F[5, 2222.88] = 6.85, p < 0.001). Model 3 is additionally adjusted for parental background variables, most importantly parental wealth. Again, these variables are jointly significantly related to individuals’ net wealth (F[9, 3882.75] = 14.03, p < 0.001). Adding the parental background variables also substantially reduces the unexplained between-family variance as indicated by the reduction in the variance estimate for families between Models 2 and 3. While adding other aspects of the sibship configuration magnifies the estimated differences by sibship size by about 13%, entering the parental background characteristics to the model sharply reduces the estimated coefficient for sibship size by about 29%. This underlines the importance of adjusting for both set of variables when studying the association between sibship size and wealth.

Table 3.

Multivariate regression of net wealth with the number of siblings

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | |

| Sibship size | − 0.60*** | − 0.68*** | − 0.48*** | |

| (0.09) | (0.11) | (0.11) | ||

| Sibship size (ref.: only child) | ||||

| One sibling | − 0.87* | |||

| (0.39) | ||||

| Two siblings | − 1.39*** | |||

| (0.42) | ||||

| Three siblings | − 2.06*** | |||

| (0.54) | ||||

| Four siblings | − 2.05** | |||

| (0.70) | ||||

| Five siblings | − 3.26*** | |||

| (0.85) | ||||

| Six or more siblings | − 2.27** | |||

| (0.87) | ||||

| Birth order index | − 0.93* | − 0.79* | − 0.78* | |

| (0.37) | (0.37) | (0.37) | ||

| Close birth spacing (less than 2 years) | 0.37 | 0.20 | 0.23 | |

| (0.30) | (0.29) | (0.29) | ||

| Mother’s age at birth of respondent | 0.14*** | 0.11*** | 0.11*** | |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | ||

| Sex composition of siblings | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.31 | |

| (0.46) | (0.45) | (0.45) | ||

| Any step siblings | − 0.94* | − 0.60 | − 0.57 | |

| (0.46) | (0.49) | (0.49) | ||

| Parental wealth | 0.14*** | 0.14*** | ||

| (0.03) | (0.03) | |||

| Parents in homeownership | 1.95*** | 1.94*** | ||

| (0.32) | (0.32) | |||

| At least one parent has university degree | 0.23 | 0.26 | ||

| (0.37) | (0.37) | |||

| Occupational status of parents (ISEI) | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | |||

| Parental risk preferences | 0.06 | 0.06 | ||

| (0.10) | (0.10) | |||

| Parental impulsiveness | − 0.23* | − 0.23* | ||

| (0.10) | (0.10) | |||

| At least one grandparent has uni. degree | 0.59 | 0.58 | ||

| (0.42) | (0.42) | |||

| Not lived with both parents until age 15 | − 0.43 | − 0.45 | ||

| (0.45) | (0.45) | |||

| At least one parent died | 0.23 | 0.25 | ||

| (0.31) | (0.31) | |||

| Constant | 4.11*** | 0.48 | − 1.65 | − 1.24 |

| (0.50) | (0.85) | (1.13) | (1.18) | |

| Variance components | ||||

| Variance family | 5.55*** | 5.15*** | 3.59*** | 3.39** |

| (1.38) | (1.35) | (1.27) | (1.30) | |

| Variance individual | 13.63*** | 13.47*** | 13.03*** | 13.11*** |

| (1.76) | (1.74) | (1.67) | (1.69) | |

| Variance residuals | 27.77*** | 27.76*** | 27.72*** | 27.74*** |

| (1.26) | (1.26) | (1.25) | (1.25) | |

| N Observations | 6388 | 6388 | 6388 | 6388 |

| N Individuals | 3502 | 3502 | 3502 | 3502 |

| N Families | 2628 | 2628 | 2628 | 2628 |

Data: SOEP version 33.1 (2002, 2007, 2012); multiply imputed; unweighted

Linear multilevel regression with outcome variable personal net wealth (IHS-transformed); Huber–White robust standard errors in parentheses; all models include control variables for age, age squared, women, immigrant, lived in East Germany in 1989, period and sample origin; full estimation results in Table S.2 in Online Appendix; *p < .05; **p < .01, ***p < .001 (two-tailed tests)

Model 3 is the preferred model to test hypotheses on the association between sibship size and net wealth (Table 3). Once all control variables are included in Model 3, the estimated effect of an additional sibling is − 0.48 points on the IHS-transformed scale. This coefficient’s interpretation is similar to a regression with a logged outcome (Pence 2006). Thus, each additional sibling reduces wealth by about 38% (= 100*[exp(− 0.48) − 1]). To put this further in perspective, the average yearly increase in wealth over the life course from Model 3 is 0.20. Thus, individuals need to accumulate wealth for about two more years to offset the disadvantage of having an additional sibling. When only considering the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval of the coefficient for sibship size (− 0.26), the difference in years of accumulation is about 1.3 years. The lower bound of the confidence interval is − 0.70.

Model 4 includes sibship size as a categorical variable and the estimated difference are similar to the descriptive results shown in Fig. 1. Again, the results tentatively suggest that the negative relationship between sibship size and net wealth tapers off in large sibships, but the evidence is not strong given that this model fits worse than Model 3. For up to three siblings, the association is close to being linear. With more than three siblings, the association is relatively constant with a larger negative association for five siblings. Again, less than 10% of the sample has more than three siblings. There is no evidence for the nonlinear association that would follow from strict resource dilution, where each additional sibling would have a smaller negative effect on wealth. Model 4 also provides no evidence that only children have less wealth than those with at least one sibling. In contrast, those with one sibling have statistically significantly less wealth. For the remainder of the analysis, I focus on the linear relationship between sibship size and wealth.

Overall, these results provide evidence for the Dilution Hypothesis about a general, negative association between additional siblings and wealth. There is only weak evidence in line with the Decreasing Effect Hypothesis, which expected decreasing marginal effects of additional siblings on wealth. The results further suggest that if at all such a decrease in effects only occurs in larger sibship sizes. The results are inconsistent with the Only Child Hypothesis about only children having less wealth than individuals with one sibling.

In Model 3, most aspects of the sibship configuration are not significantly associated with net wealth with two exceptions: First, individuals’ birth order position is statistically significantly negatively associated with net wealth. Later-born children are less wealthy on average. Second, the older the mother was at the birth of the respondent, the more wealth the respondent accumulates later in life. Each year in mothers’ age increases wealth by about 12% (= 100*[exp(0.11) − 1]). When considering parental characteristics, a one-point increase in parental wealth increases individuals’ wealth by about 0.14 points. This coefficient can be interpreted as an elasticity and, thus, an increase in parental wealth of 1% increases children’s wealth by 0.14%. Parental homeownership is also strongly associated with more wealth in the filial generation (1.95). Parental impulsiveness has a small but statistically significant, negative estimated effect on adult children’s wealth (− 0.23). Other parental characteristics are not significantly associated with net wealth.

Model 5 in Table 4 is used to test the Parental Wealth Hypothesis. In this hypothesis, it was expected that parental wealth compounds the negative association between sibship size and wealth, so that additional siblings are more negatively associated with individuals’ wealth at higher levels of parental wealth. The estimated negative and statistically significant interaction between parental wealth and sibship size provides evidence in favour of this hypothesis. With a one-unit increase in IHS-transformed parental wealth, the estimated negative effect of sibship size becomes 0.04 points more negative. When parents have no wealth, the estimated main effect of sibship size suggests that additional siblings are not statistically significantly associated with filial wealth. The main effect of parental wealth indicates a positive and statistically significant association between parental and filial wealth for only children.

Table 4.

Multivariate regression of net wealth with the number of siblings and interactions with birth order index and parental wealth

| Model 5 | Model 6 | |

|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | b (SE) | |

| Sibship size | − 0.12 | − 0.45*** |

| (0.20) | (0.11) | |

| Parental wealth | 0.23*** | 0.14*** |

| (0.05) | (0.03) | |

| Sibship size × Parental wealth | − 0.04* | |

| (0.02) | ||

| Birth order index | − 0.81* | − 1.39* |

| (0.37) | (0.63) | |

| Sibship size × Birth order index | 0.26 | |

| (0.22) | ||

| Constant | − 2.64* | − 1.74 |

| (1.24) | (1.13) | |

| Variance components | ||

| Variance family | 3.47*** | 3.63*** |

| (1.25) | (1.27) | |

| Variance individual | 13.02*** | 12.97*** |

| (1.67) | (1.67) | |

| Variance residuals | 27.74*** | 27.72*** |

| (1.25) | (1.25) | |

| N Observations | 6388 | 6388 |

| N Individuals | 3502 | 3502 |

| N Families | 2628 | 2628 |

Data: SOEP version 33.1 (2002, 2007, 2012); multiply imputed; unweighted

Linear multilevel regression with outcome variable household net wealth (IHS-transformed); Huber–White robust standard errors in parentheses; all models include control variables for close birth spacing, mother’s age at birth of respondent, sex composition of siblings, parents in homeownership, one parent has university degree, occupational status of parents, parental risk preferences, parental impulsiveness, not lived with both parents until age 15 age, at least one parent died, one grandparent has university degree, age squared, women, immigrant, lived in East Germany in 1989, period and sample origin; full estimation results in Table S.2 in Online Appendix; *p < .05; **p < .01, ***p < .001 (two-tailed tests)

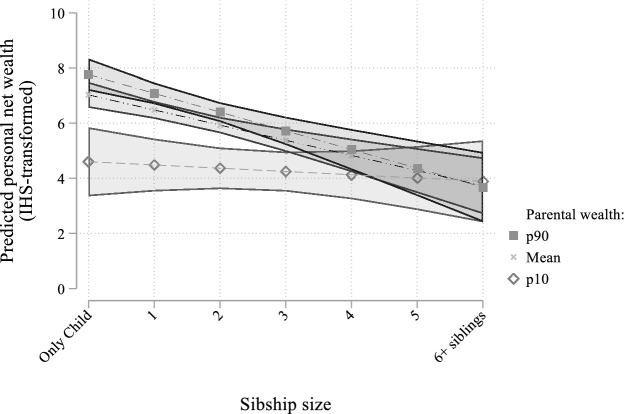

The moderation of the relationship between sibship size and net wealth by parental wealth is further illustrated in Fig. 2. The figure shows predicted net wealth by sibship size for three values of parental wealth: mean parental wealth (= 10.75 IHS-transformed net wealth) and at the 10th (= 0) and 90th percentile (= 13.99) of the parental wealth distribution. The figure shows a steeper reduction in predicted net wealth by sibship size for those with wealthier parents compared to less wealthy parents. For those at the bottom of the parental wealth distribution, sibship size is not associated with net wealth. The figure also shows that the parental wealth advantage in the filial generation vanishes in larger sibships. While individuals with wealthier parents have more net wealth if they are only children or have one or two siblings compared to those at the bottom of the distribution, these differences are no longer statistically significant once individuals have at least three siblings. For those with six and more siblings, net wealth is estimated to be virtually the same irrespective of parental wealth.

Fig. 2.

Predicted net wealth by sibship size and parental wealth. Data: SOEP version 33.1 (2002, 2007, 2012); multiply imputed; unweighted. Note: Prediction based on Model 5 in Table 4; all other variables at their means; areas indicate 95% confidence interval

To test the Birth Order Hypothesis, Model 6 in Table 4 is used. Here, the expectation was that children with a higher birth order position are more negatively affected by additional siblings leading to less wealth. Birth order position is negatively associated with wealth, i.e. later-born siblings have less wealth, on average. Against the expectation, no evidence is found for a moderation of the association between sibship size and wealth by birth order position in the data. The estimated coefficient for the interaction has an unexpected positive sign. In additional analyses, interactions between sibship size and being the first-born or last-born sibling are analysed, but the interaction terms are statistically insignificant (see Table S.3 in Online Appendix).

Supplemental Results

The main analysis is based on a relative young sample—similar to most previous studies—for which parental characteristics are directly observed in the SOEP. To probe the potential role of transfers in later life, the analysis is repeated with samples including older individuals (age 18–79), for whom, however, parental characteristics are not directly observed in the data. When including older individuals, the estimated effect of sibship size on net wealth is reduced but remains statistically significant and substantial (Model 8, Table 5). Each additional sibling is found to reduce net wealth by about 27% (= 100*[exp(− 0.31) − 1]). Results are similar when using the age restriction of the main analysis without controlling for parental wealth and parental psychological characteristics (Model 7). I find no statistically significant interaction between sibship size and birth order.

Table 5.

Supplementary model results for older sample and household net wealth

| Older sample | Household net wealth | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 18–59 | Age 18–79 | |||||

| Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 | |

| b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | |

| Sibship size | − 0.37*** | − 0.31*** | − 0.30*** | − 0.35** | 0.00 | − 0.31* |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.13) | (0.20) | (0.13) | |

| Birth order index | − 0.32 | − 0.26 | − 0.71* | − 0.83 | − 0.85 | − 1.59* |

| (0.17) | (0.15) | (0.27) | (0.44) | (0.44) | (0.70) | |

| Parental wealth | Not included | 0.16*** | 0.24*** | 0.15*** | ||

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.05) | ||||

| Sibship size × parental wealth | − 0.04* | |||||

| (0.02) | ||||||

| Sibship size × birth order index | 0.18 | 0.33 | ||||

| (0.10) | (0.25) | |||||

| N Observations | 37,032 | 53,513 | 53,513 | 6388 | 6388 | 6388 |

| N Individuals | 21,268 | 28,894 | 28,894 | 3502 | 3502 | 3502 |

| N Families | 20,369 | 27,990 | 27,990 | 2628 | 2628 | 2628 |

Data: SOEP version 33.1 (2002, 2007, 2012); multiply imputed; unweighted

Linear multilevel regression with outcome variable personal (household in Model 10-Model 12) net wealth (IHS-transformed); Huber–White robust standard errors in parentheses; full model results in Table S.4 and S.5 in Online Appendix; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 (two-tailed tests)

In a second supplemental analysis, personal net wealth is replaced with household net wealth, which was mostly used in previous research, to probe how household composition may contribute to sibship effects. Results are similar to the main analysis (Model 10-Model 12, Table 5), but the estimated coefficient of sibship size is slightly smaller (− 0.35 in Model 10). This may suggest that household composition partly compensates the negative consequences of having siblings for individuals. For instance, a smaller negative association at the household level may be because those with siblings are more likely to form partnerships (Bobbitt-Zeher et al. 2016) and benefit from the wealth of their partners.

Finally, the main analysis is stratified by gender (Table 6). For both genders, the sibship size is negatively associated with personal net wealth (Model 13 and Model 16). The effect size for men is with − 0.61 almost twice as large as for women (− 0.33). However, both coefficients are not statistically significantly different from each other at conventional levels [z value of 1.04 based on Paternoster et al. (1998)]. The interaction between parental wealth and sibship size is only statistically significant for men, but the estimated interaction effect for women is also negative and similar in size to the estimated effect in the pooled model (which was significant). For women and men, the interaction between sibship size and birth order is not statistically significant in line with the results from the pooled model. Interestingly—although not in the focus of the present study—birth order is only significantly associated with wealth for women. Within the birth order, earlier-born women have more wealth than later-born women. This is not the case for men.

Table 6.

Supplementary model results stratified by gender

| Women | Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 13 | Model 14 | Model 15 | Model 16 | Model 17 | Model 18 | |

| b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | |

| Sibship size | − 0.33* | − 0.04 | − 0.30 | − 0.61*** | − 0.15 | − 0.58*** |

| (0.15) | (0.25) | (0.15) | (0.15) | (0.27) | (0.16) | |

| Birth order index | − 1.63** | − 1.64** | − 2.18* | 0.16 | 0.12 | − 0.34 |

| (0.52) | (0.52) | (0.85) | (0.51) | (0.52) | (0.87) | |

| Parental wealth | 0.14*** | 0.21** | 0.14*** | 0.12** | 0.24** | 0.12** |

| (0.04) | (0.07) | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.08) | (0.05) | |

| Sibship size × parental wealth | − 0.03 | − 0.05* | ||||

| (0.02) | (0.02) | |||||

| Sibship size × birth order index | 0.25 | 0.22 | ||||

| (0.29) | (0.32) | |||||

| N Observations | 3337 | 3337 | 3337 | 3051 | 3051 | 3051 |

| N Individuals | 1821 | 1821 | 1821 | 1681 | 1681 | 1681 |

| N Families | 1568 | 1568 | 1568 | 1430 | 1430 | 1430 |

Data: SOEP version 33.1 (2002, 2007, 2012); multiply imputed; unweighted

Linear multilevel regression with outcome variable personal net wealth (IHS-transformed); Huber–White robust standard errors in parentheses; full model results in Table S.6 in Online Appendix; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 (two-tailed tests)

Conclusion

Using data from the German SOEP, this study examines the association between sibship size and wealth in adulthood building on resource dilution theory and considering potential wealth-enhancing consequences of having siblings. The study finds a mostly linear association between sibship size and wealth, which is robust to different model specifications. Each additional sibling reduces wealth by about 38%. Parental wealth is a strong predictor of net wealth and the analysis shows that parental wealth compounds the negative association between having more siblings and wealth in Germany. Having more siblings is more negatively related to net wealth when individuals have wealthy parents. Birth order position is negatively associated with wealth, but does not moderate the association under study.

This study is among the first to consider heterogeneity in the association between sibship size and net wealth to better understand between- and within-family inequalities. Regarding the moderating role of parental wealth, I show that—in line with theoretical expectations (Lawson and Mace 2009)—resource dilution through siblings seems to be stronger in wealthy families in Germany. This may be explained through “floor effects” (Bernardi and Radl 2014: 1657) at the lower end of the wealth distribution, because only in families with sufficient surplus resources such as parental wealth, these resources may be diluted. In contrast, relatively poor families may not be able to provide any surplus resources which would then be diluted. Similar arguments have also been made to explain larger educational penalties for children after parental separation when parents are highly educated compared to less educated parents (Bernardi and Boertien 2017; Bernardi and Radl 2014). Previously, there was only tentative evidence for such a moderating role by parental resources through family income in the case of wealth attainment (Keister 2004). The present study underlines the relevance of distinguishing surplus and base resources when considering resource dilution.

Parental wealth is not only a moderator of the relationship between sibship size and net wealth, but can also be expected to be an important confounder. Wealthier parents may be less likely to have more children leading to a spurious relationship between sibship size and wealth. The current study is among the first to adjust for concurrent parental wealth and additionally controls for parental psychological characteristics. Thereby and by adjusting for additional parental characteristics, the estimated association between sibship size and parental wealth is reduced by more than one fourth. The estimated association is substantially smaller than previously estimated for the USA without controlling for parental wealth (see Table 2). The association is substantially larger than previously estimated in models which controlled for parental wealth but also controlled for intervening mechanisms with data from the USA (Killewald 2013, see Table 1).

This study carefully considered potential nonlinearity in the association between sibship size and net wealth as suggested by resource dilution theory and by the potentially wealth-enhancing consequences of having siblings. Weak evidence suggests that the negative association between sibship size and net wealth tapers off in large sibships, but even here the evidence points towards no additional effects rather than decreasing effects; and only about 10% of individuals have such large sibships. Having one sibling is by far the most frequent sibship size category in many post-industrialized countries (Goldstein and Kreyenfeld 2011). Overall, evidence prevails that the relationship between sibship size and net wealth is mostly linear. Thus, this study suggests that the common assumption in previous literature of a linear relationship between the number of siblings and wealth is justified.

It may be surprising that decreasing marginal effects were not observed given that parental wealth is a highly dividable resource for which a decreasing marginal effect of additional siblings seems likely even for the first sibling (Downey 1995). It is, however, important to note that decreasing negative marginal effects are especially likely when considering the second mechanism through which siblings may reduce wealth: less directly transmitted wealth from parents. This mechanism may be less relevant in the current data due to the relative young sample used in the main analysis. However, also in supplemental analyses with an older sample, generally negative consequences of siblings for wealth are found. Despite compelling theoretical arguments for wealth-enhancing consequences of having siblings, which may counterbalance some of the resource dilution through siblings, the results of the current study by and large do not point in this direction. If there are any wealth-enhancing consequences, they are clearly dominated by resource dilution.

Because partnership choices and employment outcomes may relate sibship size and wealth differently for women and men, the analysis was also stratified by gender. While the conclusions regarding the hypothesis are generally similar for women and men, the results tentatively suggest that sibship size is less strongly associated with women’s wealth than with men’s wealth. One potential explanation is that women benefit more from the positive association between having siblings and being in a partnership, because for women their partners’ economic resources are relatively more important than their own labour market outcomes for accumulating wealth. This explanation needs further analysis and, more generally, the gender-specific results need to be corroborated with larger samples.

The estimated effect sizes in the current study are mostly smaller compared to previous estimates for the USA, which may be due to more supportive family policies (3.0% of GDP on family benefits in 2013) and overall smaller families (total fertility rate of 1.6 in 2016) in Germany. In addition, education is mostly free in Germany, which considerably reduces the direct costs of children. More comprehensive comparative studies are needed to identify how the association between sibship size and wealth may systematically vary across institutional contexts as has been done for sibship size and educational attainment (Park 2008).

Some limitations of the current study are noteworthy. First, the association between sibship size and wealth found here can only be interpreted as causal under the assumption that no unobserved variables are simultaneously correlated with sibship size and wealth. The current study is among the first to directly adjust for concurrent parental wealth and other parental characteristics which would be the most likely candidates for such unobserved variables. However, the measurement of parental wealth and psychological characteristics is concurrent to adult children’s outcomes. No measurement of these characteristics before individuals are born is available in the data, which would be problematic if concurrent characteristics were not strongly associated with parental characteristics before birth. Further analyses with alternative identification strategies, e.g. instrumenting sibship size with the sex composition of the sibship using register data, are needed. Second, wealth is prone to measurement error (Riphahn and Serfling 2005). This error may lead to attenuation bias, so that estimated effects are biased towards 0. Finally, very wealthy respondents are underrepresented in survey data such as the SOEP and so the current results cannot be generalized to the top of the wealth distribution.

In sum, the results underline the important role of the family of origin and more particularly of the number of siblings for wealth attainment. The findings suggest that fertility in the family of origin has a systematic impact on wealth attainment and may contribute to population-level wealth inequalities independently from other socio-economic characteristics such as parental wealth. At the same time, the association between the number of siblings and wealth is shaped by parental wealth in Germany, where additional siblings are more adverse for wealth attainment when parents are wealthier. The relevance of fertility in the family of origin may increase in the coming years because for several years now the unprecedented wealth accumulated during the economic prosperous post-war period in many Western European countries including Germany is transferred to the following generations (Bach and Thiemann 2016), and this is not yet fully captured in the current data. In this context of large direct transfers, for which dilution is most likely, the association between sibship size and wealth may become more critical.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Marita Jacob, Reinhard Schunck, seminar participants at the University of Cologne and University of Duisburg-Essen and participants at the ECSR Workshop “Demography and Inequality” for helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. All errors remain those of the author. The computer code for the empirical analysis is available at https://osf.io/s62ed/.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

The informed consent of the interview participants was acquired by the SOEP and BHPS survey teams. The data are available through DIW Berlin and the UK Data Archive.

Footnotes

The confluence model states that the average intellectual environment in a family is important for child development. Young children reduce the “intellectual average”, and therefore, larger sibship sizes have negative developmental consequences (especially for first-born children). At the same time, interaction between siblings and tutoring of younger siblings by older siblings may improve outcomes for older siblings (Härkönen 2014; Zajonc and Markus 1975).

Full, half, step and adopted siblings are all included, as resource dilution may occur through all these different types of siblings. A control variable for half and step siblings is included in multivariate models.

Respondents from booster samples added in 2012 and thereafter are dropped as they have not participated in the wealth module in 2012 or they provide too few cases where parents and children are observed in separate households.

The birth order index is constructed as follows: Birth order index = (Birth order position of individual/((Number of siblings + 1)/2)) − 1. For instance, an only child has the value 0.000 (= [1/1] − 1), the first-born child in a two-child family has the value − 0.333 (= [1/1.5] − 1), and the second-born child in a two-child family has the value 0.333 (= [2/1.5] − 1).

The question regarding risk preferences is: “Are you generally a person who is fully prepared to take risks or do you try to avoid taking risks?" with answer categories (11-point scale) from “risk averse” to “fully prepared to take risks”. This question has been fielded in 2004, 2006 and then annually since 2008 until 2016. The question regarding impulsiveness is: “Do you generally think things over for a long time before acting—in other words, are you not impulsive at all? Or do you generally act without thinking things over for long, in other words, are you very impulsive?” with answer categories (11-point scale) from “not at all impulsive” to “very impulsive”. The question has been fielded in 2008 and 2013.

It is assumed that these characteristics do not change after a childbirth.

Family fixed-effects models cannot be estimated as the sibship size is a family-level characteristic.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Anastasi A. Intelligence and family size. Psychological Bulletin. 1956;53(3):187–209. doi: 10.1037/h0047353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angrist JD, Lavy V, Schlosser A. Multiple experiments for the causal link between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Labor Economics. 2010;28(4):773–824. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, S., Thiemann, A. (2016). Inheritance tax revenue low despite surge in inheritances. DIW Economic Bulletin 4/5 2016. Berlin: Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung. https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.525511.de/diw_econ_bull_2016-04-1.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2016.

- Baranowska-Rataj A, de Luna X, Ivarsson A. Does the number of siblings affect health in midlife? Evidence from the Swedish prescribed drug register. Demographic Research. 2016;35(43):1259–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS, Tomes N. Child endowments and the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy. 1976;84:S143–S162. [Google Scholar]

- Behrman JR, Pollak RA, Taubman P. Parental preferences and provision for progeny. Journal of Political Economy. 1982;90:52–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi F, Boertien D. Explaining conflicting results in research on the heterogeneous effects of parental separation on children’s educational attainment according to social background. European Journal of Population. 2017;33:243–266. doi: 10.1007/s10680-017-9417-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi F, Radl J. The long-term consequences of parental divorce for children’s educational attainment. Demographic Research. 2014;30:1653–1680. [Google Scholar]

- Bischof D. New graphic schemes for Stata: Plotplain and plotting. Stata Journal. 2017;17:748–759. [Google Scholar]

- Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG. The more the merrier? The effect of family size and birth order on children’s education. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2005;120(2):669–700. [Google Scholar]

- Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG. Small family, smart family? Family size and the IQ scores of young men. Journal of Human Resources. 2010;45(1):33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Blake J. Family size and achievement. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bobbitt-Zeher D, Downey DB, Merry J. Number of siblings during childhood and the likelihood of divorce in adulthood. Journal of Family Issues. 2016;37:2075–2094. doi: 10.1177/0192513X14560641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth AL, Kee HJ. Birth order matters: The effect of family size and birth order on educational attainment. Journal of Population Economics. 2008;22(2):367–397. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Garino G, Taylor K. Household debt and attitudes towards risk. Review of Income and Wealth. 2013;59(2):283–304. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron L, Erkal N, Gangadharan L, Meng X. Little emperors: Behavioral impacts of China’s one-child policy. Science. 2013;339(6122):953–957. doi: 10.1126/science.1230221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavapozzi D, Fiume A, G C, Weber G. Human capital accumulation and investment behaviour. In: Börsch-Supan A, Brandt M, Hank K, Schröder M, editors. The individual and the welfare state: Life histories in Europe: 45–66. Berlin: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Charles KK, Hurst E. The correlation of wealth across generations. Journal of Political Economy. 2003;111(6):1155–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Conley D, Glauber R. Parental educational investment and children’s academic risk: Estimates of the impact of sibship size and birth order from exogenous variation in fertility. Journal of Human Resources. 2006;51(4):722–737. [Google Scholar]

- Donkers B, van Soest A. Subjective measures of household preferences and financial decisions. Journal of Economic Psychology. 1999;20(6):613–642. [Google Scholar]

- Downey DB. When bigger is not better: Family size, parental resources, and children’s educational performance. American Sociological Review. 1995;60(5):746–761. [Google Scholar]

- Downey DB. Number of siblings and intellectual development: The resource dilution explanation. American Psychologist. 2001;56(6–7):497–504. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.6-7.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey DB, Condron DJ. Playing well with others in kindergarten: The benefit of siblings at home. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66(2):333–350. [Google Scholar]

- Emery T. Intergenerational transfers and European families: Does the number of siblings matter? Demographic Research. 2013;29(10):247–274. [Google Scholar]

- Friedline T, Masa RD, Chowa GA. Transforming wealth. Using the inverse hyperbolic sine (IHS) and splines to predict youth’s math achievement. Social Science Research. 2015;49:264–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galton F. English men of science: Their nature and nurture. London: Macmillan; 1874. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs BG, Workman J, Downey DB. The (conditional) resource dilution model: State- and community-level modifications. Demography. 2016;53(3):723–748. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0471-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JR, Kreyenfeld M. Has east germany overtaken west Germany? Recent trends in order-specific fertility. Population and Development Review. 2011;37(3):453–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grätz M, Torche F. Compensation or reinforcement? The stratification of parental responses to children’s early ability. Demography. 2016;53:1883–1904. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0527-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, Vanwey LK. Sibship size and intellectual development: Is the relationship causal? American Sociological Review. 1999;64(2):169–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MN. Self-made wealth or family wealth? Changes in intergenerational wealth mobility. Social Forces. 2014;93(2):457–481. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek EA. The trade-off between child quantity and quality. Journal of Political Economy. 1992;100(1):84–117. [Google Scholar]