Abstract

Children seem to present a barrier to the gender revolution in that parents are more likely to divide paid and domestic work along traditional gender lines than childless couples are. However, the extent to which this is so varies between countries and over time. We used data on 35 countries from the 2012 International Social Survey Programme to identify the contexts in which parents and non-parents differ the most in their division of labour. In Central/South America, Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, Asia, and South Africa, labour sharing configurations did not vary as much with the presence of children as in Australia, Western Europe, North America, and Northern Europe. Our multilevel models helped explain this pattern by showing that children seem to present a greater barrier to the gender revolution in richer and, surprisingly, more gender equal countries. However, the relationship between children and couples’ division of labour can be thought of as curvilinear, first increasing as societies progress, but then weakening if societies respond with policies that promote men’s involvement at home. In particular, having a portion of parental leave reserved for fathers reduces the extent to which children are associated with traditional labour sharing in the domestic sphere.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10680-018-09515-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Male role, Female role, Labour force, Housework, Child care, Family policy, Gender revolution

Introduction

The massive gender revolution that is underway throughout the world appears to have two phases: women first join men in contributing labour in the public sphere by participating in market work; then men join women in contributing labour in the private sphere by participating in child care and housework (Goldscheider et al. 2015). Participating in both halves of the gender revolution presents a greater challenge to couples when they have children, given the time demands of caring for children and the strength of traditional parenting norms. However, the degree to which children strengthen a gender traditional division of paid and domestic work varies both across countries (Anxo et al. 2011; Craig and Mullan 2011; Neilson and Stanfors 2014) and over time (Craig et al. 2010; Neilson and Stanfors 2013, 2014; Kitterød and Rønsen 2013). The cultural, political, and economic context can influence the economic and subjective benefits of adopting the “male breadwinner/female caregiver” family model (Hook 2006; Treas and Lui 2013). Thus, the presence of children in the household and their effect on women’s participation in the labour force and on male involvement in the domestic sphere may be moderated by the greater social context.

The broader literature on couples’ division of labour has identified gender inequality, socioeconomic development, and work and family policies as important contextual variables (Fuwa 2004; Geist 2005; Campaña et al. 2015). Our question of whether children are barriers to the gender revolution stems from recognizing that these macro-level variables may condition the labour sharing of parents and childless couples differently. For instance, while an egalitarian division of housework is more common in advanced economies, children may present a greater barrier to egalitarian labour sharing where parents make heavy investments in child quality. The growing literature on variation in the relationship between parenthood and couples’ division of labour across countries and over time focuses mostly on the contextual effects of work and family policies (Craig et al. 2010; Anxo et al. 2011; Kitterød and Rønsen 2013; Neilson and Stanfors 2014). We explicitly modelled gender inequality and socioeconomic development simultaneously with family policies.

Further, research on the extent to which parenthood is linked with a traditional division of labour has focused mostly on Northern Europe (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden) with a handful of other countries represented (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, and the USA). We broadened the scope of this inquiry beyond Western societies using data from 35 countries from the 2012 International Social Survey Programme (ISSP). These data allowed us to describe how strongly the presence of children is associated with couples’ division of labour across world regions—Northern, Eastern, Western, and Southern Europe, North America, Australia, Asia, Central/South America, and South Africa. We expected children to be more weakly linked with a couples’ division of labour in (1) countries with greater public sphere gender equality, (2) lower-income countries, and (3) countries with supportive family policies. What we found suggests much greater complexity.

Background: The Gender Revolution

We follow Goldscheider et al. (2015) in positing that the massive gender revolution ongoing throughout the world has two distinct phases. During the first half, women joined men in contributing labour in the public sphere by participating in market work while maintaining their domestic roles, leaving women with a “second shift” (Hochschild and Machung 1989). Men’s family care roles evidently did not need to change for a while, as women were responding to new opportunities, electively adding new roles even as their commitment to home care remained (Baxter 1997; Stanfors and Goldscheider 2017). As life-long employment increasingly became normative for women, however, women’s second shift came to harm their quality of life, putting pressure on expectations and practices vis-à-vis the male role (Hochschild and Machung 1989). Hence, men began to respond to this asymmetry by joining women in contributing labour in the private sphere by participating in child care and housework, the second half of the gender revolution. This second phase normally occurs later than the growth of female labour force participation, because women’s earning an income provides more immediate and tangible rewards than men’s taking on unpaid tasks (Goldscheider et al. 2015), plus women are normally better prepared for paid employment through education than men are for taking on domestic tasks.

To understand gender specialization in family and work, scholars have tried to account for both the individual and macro-level mechanisms that underlie couples’ unequal division of paid and domestic labour (Bianchi and Milkie 2010). At the individual level, the main theoretical explanations refer to the role of time availability, relative resources between partners, and the doing gender paradigm (Fenstermaker 1985); there is evidence supporting each of these perspectives. Further, although most of the variation in the division of domestic labour is within and not between countries (Van der Lippe et al. 2011), cross-national variance is relevant and individual-level factors’ influence might be even declining in favour of the broader social and cultural context (Treas and Lui 2013), the focus of this paper.

The Problem of Children

Participating fully in the gender revolution presents a greater challenge to couples with children than those without children, given the time demands of caring for children and the strength of traditional gender norms vis-à-vis parenting. Children increase the expense and domestic workload of the household, which necessarily affects how couples organize their time. Children typically have a differential impact on men and women, who feel different pressures to provide and care, respectively (e.g. Anxo et al. 2011). As a result, parents tend to conform to more traditional gender roles than couples without children (Craig 2006; Fox 2009; Schober 2013; Cosp and Román 2014; Kitterød and Rønsen 2013) and become more traditional in their gender roles and attitudes after children are born (Morgan and Waite 1987; Barber and Axinn 1998; Berrington et al. 2008).

The gendered division of labour has been posited by functionalist theorists as natural and functional to the family (Parsons 1959), by economists as more efficient (Becker 1985), and by the followers of Freud as being essential to mental health (e.g. Strecker 1946). In contrast, the feminist perspective argues that these imposed gender scripts limit female development in other domains (Budig 2004). These cultural, political, and economic perspectives shape the contexts in which couples value and choose various options for dividing labour between them (Hook 2006; Treas and Lui 2013). Thus, the presence of children in the household and its association with women’s participation in labour force (first half of gender revolution) and with male involvement in the domestic sphere (second half of the revolution) are likely to be moderated by the greater social context, the focus of this analysis.

Children and Context

We focus on the same three contextual dimensions shown to be important in the general literature on couples’ labour sharing: overall gender equality, socioeconomic development, and public support for families (Fuwa 2004; Geist 2005; Campaña et al. 2015). Here, we discuss why these contextual dimensions might shape the labour sharing configurations of childless couples and couples with children differently.

Gender Equality Context

The gender revolution arose both from changing economies and lower fertility. As two incomes became increasingly necessary to support families in many countries (Oppenheimer 1997), the traditional division of labour with men’s earnings supporting the stay-at-home mothers of their children became less practical, and with fewer children, women had more time for paid employment in the jobs that emerged in these changing economies (Cherlin 2012). The stay-at-home maternal role may also have become less desirable in contexts where women as well as men are educated and socialized for market work and marital unions have become less stable. With more gender equality in the public sphere—legal equality and equal opportunity to participate in government, the marketplace, and educational institutions (McDonald 2000, 2013)—couples have become increasingly likely to renegotiate gender roles in the private sphere (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 1995; Gershuny 2003; Esping-Andersen and Billari 2015). Not surprisingly, egalitarian arrangements within families tend to be more common in countries with more gender equality in the public sphere (Fuwa 2004; Ruppanner 2010; Campaña et al. 2015). But is public sphere equality linked with a smaller impact of children on couples’ division of labour?

Increasing men’s involvement in work within the household—the second half of the gender revolution—often challenges prevailing notions of what is “men’s work” and what is “women’s work” (Kan et al. 2011; Blair-Loy et al. 2015). Cultural scripts for how gender is “done” tend to persist, even into the second generation after women enter the paid labour force in large numbers. Even though higher income and education are associated with more intensive parenting for both men and women (Sayer et al. 2004; Mannino and Deutsch 2007; Gimenez-Nadal and Molina 2013; Sullivan et al. 2014; Dotti Sani and Treas 2016), women still carry most of the work of parenting, especially when it comes to routine work and solo care. This is true even in countries with much gender equality in the public sphere like Denmark (Guryan et al. 2008; Craig and Mullan 2011; Miranda 2011). Nonetheless, we expect that the demands associated with childrearing may be more equally shared in countries with greater gender equality (Knudsen and Wærness 2008).

Socioeconomic Development

Per capita national income can be expected to condition the effect of children on couples’ division of labour because it reflects many dimensions of socioeconomic development, including women’s employment, fertility rates, and standards of education and parenting. In lower-income countries where informal sector jobs are more common and where relatives, usually grandmothers, are often available to care for children, children may not limit women’s paid work as much as in higher-income countries (Schkolnik 2004; Heisig 2011; Martínez Gómez et al. 2013; Craig and Baxter 2016). While these strategies would promote the first half of the gender revolution by making it easier for women to be employed, low-cost options for domestic work may impede the second half, because men may not be called upon to fill the void created by women having less time to devote to domestic work. Furthermore, the quantity/quality trade-off with respect to children (Becker and Lewis 1974) is also relevant in two distinct ways. First, where fewer women remain childless (and where more women have multiple children), the division of labour among childless couples may reflect future expectations for childbearing to a greater extent than where societal fertility levels are lower. If this were the case, couples with and without children could have more similar gender roles in more pronatalist (often lower income) societies. Second, investments in child quality universally include investments in education, but in higher-income countries they also frequently include intensive parenting norms. Overall, we expect that children present a more substantial barrier to the gender revolution in higher-income countries.

Family Policy

Finally, the second half of the gender revolution is also likely to be shaped by laws and institutions (Rao and Kelleher 2003; Kan et al. 2011). Family policy can either promote egalitarianism or reinforce traditional gender norms (e.g. Ruhm 2011). Policy that reduces the total domestic burden may make it less likely that one partner is overburdened in the domestic sphere. Even imagining that such programs exist has been shown to lead both young men and women to favour more egalitarian labour sharing arrangements (Pedulla and Thébaud 2015). Therefore, programs like subsidized universal preschool childcare and tax credits for hiring domestic employees (Raz-Yurovich 2016) might promote the second half of the gender revolution by decreasing the number of domestic work hours. Further, labour and social policies favouring female labour force participation reduce incentives for couples to split their roles in the traditional way (Tavora 2012; Boeckmann et al. 2015; Epstein et al. 2014; Pedulla and Thébaud 2015; Munsch 2016). Laws supporting equal pay for equal work are the most obvious example, but there are more. For instance, when part-time work carries rewards proportional to full-time work, it is a more viable alternative to specialization for both men and women than when its rewards are structurally limited (Lewis et al. 2008). Subsidized universal daycare or preschool also reduces the opportunity costs to having both partners in the paid labour force, making couples freer to negotiate the division of labour as they wish (Geist 2005; Lewis 2009; Korpi et al. 2013; Blofield and Martínez 2014).

However, family policy that encourages maternal caregiving can reinforce traditional gender roles, particularly if it is generous (Ray et al. 2010). Therefore, while we expect that the relationship between children and couples’ division of labour will be weaker in societies where there are strong state supports for children (Dribe and Stanfors 2009; Craig et al. 2010; Anxo et al. 2011; Neilson and Stanfors 2013, 2014; Kaufman et al. 2017), our measurement of family policies includes both the level of benefits and an indicator of whether gender equality is promoted.

Data, Measures, and Methods

Data

The ISSP has conducted annual, comparable, nationally representative surveys in a wide variety of countries since 1984. It is well known for developing questions that are meaningful in all of the countries, and for its care in translating survey items (Harkness and Schoua-Glusberg 1998). We used data from the 2012 survey on “Family and Changing Gender Roles” fielded in 41 countries; 35 had data suitable for our analysis (see Table 1 for explanations).

Table 1.

2012 ISSP countries

| Region | Countries |

|---|---|

| Western Europe | Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, (Great Britaina), Ireland, Netherlands, Switzerland |

| Northern Europe | (Denmarkb), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden |

| Southern Europe | Croatia, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain |

| Eastern Europe | (Bulgariaa), Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Slovakia |

| North America | USA, Canada |

| Oceania | Australia |

| Asia | (Chinac), India, Israel, Japan, Philippines, South Korea, (Taiwana), (Turkeyd) |

| Latin America | Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Venezuela |

| Africa | South Africa |

aExcluded because the question on the number of partner’s paid work hours was not used

bExcluded because the question identifying coresidential unions was not used

cExcluded because the hours worked question asked “did you work for more than 1 h last week?”; in other countries, the question was total hours worked in a typical week

dExcluded because questions on the number of children in the household were mistakenly omitted from the ISSP questionnaire

Although the countries included are relatively wealthy by world standards, the data set is unique in allowing all regions of the world to be at least minimally represented when describing how children are associated with the division of labour. Using it, we were able to explore how context shapes the association between children and couples’ labour sharing in countries with different combinations of national gender equity and family policy (e.g. Chile has lower national income than most countries offering paid parental leave).

There were 29,524 respondents living in coresidential unions (both married and cohabiting) in the original sample. We limited our analytic sample to the 18,663 couples in which the respondent was aged 18–55 to minimize the effects of selection into retirement.1 We further restricted the sample to couples that had a choice over how to divide labour by dropping those where at least one partner was permanently sick or disabled (484), unemployed but seeking work (2176), or in compulsory service (38). Respondents who were temporarily not working because of parental leave were asked to provide information about their normal work situation.

We dropped the 2471 respondents who did not give numeric responses for work hours (including non-response as well as answers like “varies” and “don’t know”). We also dropped the three that did not report their gender.2 This left 13,491 respondents across the 35 countries, with a range from 170 observations in Canada to 717 in France.

Measures

Dependent Variable

To measure how couples divided paid and domestic work, we used the number of hours per week the survey respondent reported spending (1) doing paid work, (2) caring for other household members, and (3) doing household work. Respondents also reported the number of hours their partner spent in the same domains. We added care hours to housework hours to obtain domestic work hours (top-coded at 60 per week, as was paid work). We considered a couple’s division of domestic or paid work to be equal if there was a difference of less than 7 h per week (less than 1 h per day) between his contribution and hers.

We then constructed a four-category variable for couples’ division of paid and domestic work (adapted from Moen 2003). In the first two categories, couples divided labour along traditional gender lines: she did more domestic work and he did more paid work. We called the couples “traditional” if she did not participate in paid labour at all, and “neotraditional” if she did, but her paid work hours were at least seven per week fewer than his. The third category, which we labelled “her second shift” (Hochschild and Machung 1989), was comprised of couples where both partners contributed similar paid hours, but she put in at least seven more hours of domestic work per week than he did. The first half of the gender revolution was apparent among couples in the “her second shift” category, but the second half was not as women still carried a heavier domestic burden. The final category was comprised of couples in which the second half of the gender revolution was apparent: his contribution to domestic work equalled or exceeded hers. Although over 70% of the couples in this fourth category practiced an egalitarian division of labour in both spheres, we labelled this category “modern” rather than “egalitarian” because it also included couples who divided paid and domestic work unequally, but not along traditional gender lines. See Table 2 for the distribution of these categories by region and country.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the dependent variable, couples’ division of labour, from the 2012 ISSP survey

| Region/country | n | % in category, weighted frequencies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Neotraditional | Her second shift | Modern | ||

| Western Europe | 3388 | 14.2 | 30.9 | 16.8 | 38.1 |

| Austria | 354 | 12.0 | 35.9 | 19.7 | 32.5 |

| Belgium | 643 | 7.2 | 28.9 | 22.3 | 41.7 |

| France | 717 | 8.3 | 23.4 | 21.0 | 47.3 |

| Germany | 548 | 19.7 | 35.6 | 11.3 | 33.4 |

| Ireland | 372 | 24.6 | 22.9 | 16.8 | 35.7 |

| Netherlands | 331 | 16.9 | 36.2 | 10.0 | 36.7 |

| Switzerland | 423 | 19.2 | 39.7 | 9.7 | 31.4 |

| Northern Europe | 1578 | 6.1 | 18.0 | 20.3 | 55.5 |

| Finland | 396 | 8.4 | 13.8 | 21.1 | 56.7 |

| Iceland | 368 | 7.9 | 28.0 | 18.8 | 45.4 |

| Norway | 487 | 2.9 | 14.4 | 21.6 | 61.2 |

| Sweden | 327 | 5.8 | 16.8 | 19.9 | 57.5 |

| Australia | 491 | 18.1 | 32.3 | 16.5 | 33.1 |

| North America | 577 | 19.9 | 15.3 | 17.4 | 47.4 |

| Canada | 170 | 12.5 | 15.7 | 18.0 | 53.8 |

| USA | 407 | 22.9 | 15.2 | 17.1 | 44.9 |

| Southern Europe | 1492 | 13.3 | 20.4 | 39.1 | 27.2 |

| Croatia | 274 | 10.3 | 17.0 | 46.7 | 26.1 |

| Portugal | 196 | 10.5 | 14.4 | 47.1 | 27.6 |

| Slovenia | 312 | 11.2 | 14.4 | 58.3 | 16.0 |

| Spain | 710 | 16.2 | 25.9 | 25.7 | 32.3 |

| Eastern Europe | 2210 | 19.0 | 19.5 | 34.7 | 26.9 |

| Czech Republic | 590 | 17.1 | 24.9 | 35.5 | 22.6 |

| Hungary | 241 | 23.2 | 12.8 | 44.0 | 20.1 |

| Latvia | 300 | 19.3 | 14.5 | 33.7 | 28.6 |

| Lithuania | 221 | 18.7 | 20.1 | 32.6 | 28.6 |

| Poland | 298 | 13.6 | 24.8 | 24.2 | 37.4 |

| Russia | 246 | 30.2 | 13.8 | 29.6 | 26.3 |

| Slovak Republic | 314 | 15.1 | 17.8 | 43.3 | 23.8 |

| South Africa | 337 | 24.5 | 14.2 | 26.7 | 34.6 |

| Asia | 2093 | 29.1 | 21.2 | 19.1 | 30.7 |

| India | 465 | 20.3 | 0.3 | 22.1 | 57.4a |

| Israel | 388 | 15.2 | 35.6 | 22.4 | 26.8 |

| Japan | 356 | 28.9 | 46.4 | 12.9 | 11.8 |

| Philippines | 493 | 42.2 | 12.5 | 14.9 | 30.4 |

| South Korea | 391 | 35.3 | 17.5 | 23.9 | 23.3 |

| Central/South America | 1325 | 34.5 | 13.6 | 20.4 | 31.5 |

| Argentina | 265 | 37.6 | 25.2 | 17.2 | 20.0 |

| Chile | 331 | 45.6 | 13.9 | 21.8 | 18.7 |

| Mexico | 458 | 32.3 | 11.6 | 18.3 | 37.8 |

| Venezuela | 271 | 18.3 | 5.6 | 24.9 | 51.2 |

| Total | 13,491 | 19.0 | 22.1 | 23.5 | 35.5 |

aOne-third of men with a child in the household said their partner spent an hour or less caring for other family members. This distorts the descriptive statistics, but is less consequential in the multivariate analyses that include a control for respondent’s gender (see also Sect. 5.1)

Individual-Level Independent Variables

Our key-independent variable was whether there was a child in the household. The coefficient on this variable measures the association between parenthood and labour configurations.3 We controlled for religiosity, because of its links with fertility (Adserà 2013) and gender traditionalism (Denton 2004). Those who attended services at least once a month were in fact the most likely to have a child in the house, but those attending less than once a year (including never) were also significantly more likely to have a child than infrequent attenders (several times per year or once a year).4 Because of the nonlinear relationship, we included religiosity as a categorical variable. We also added a separate category for missing religiosity that allowed us to retain Australia where the attendance question was not asked, as well as scattered cases from other countries (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics, individual-level independent variables, 2012 ISSP survey

| Region/country | Age | Education level | Male | Child in household | Preschool child | Two or more children | Attends frequently | Attends infrequently | Religiosity attends almost never | Missing | Urban residence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Western Europe | 40.1 | 4.1 | 46 | 60 | 29 | 36 | 16 | 30 | 53 | 1 | 56 |

| Austria | 40.0 | 2.8 | 46 | 41 | 18 | 23 | 20 | 48 | 31 | 1 | 67 |

| Belgium | 39.7 | 4.1 | 50 | 60 | 30 | 38 | 9 | 30 | 61 | 1 | 49 |

| France | 38.5 | 3.8 | 45 | 66 | 34 | 41 | 8 | 23 | 67 | 2 | 58 |

| Germany | 41.4 | 4.4 | 46 | 57 | 22 | 31 | 17 | 21 | 61 | 1 | 61 |

| Ireland | 39.1 | 4.5 | 48 | 72 | 46 | 47 | 40 | 34 | 25 | 1 | 65 |

| Netherlands | 41.8 | 4.5 | 39 | 59 | 27 | 37 | 14 | 39 | 45 | 1 | 54 |

| Switzerland | 42.1 | 4.2 | 49 | 57 | 26 | 34 | 19 | 33 | 48 | 0 | 41 |

| Northern Europe | 40.1 | 4.4 | 49 | 67 | 35 | 43 | 7 | 33 | 60 | 0 | 72 |

| Finland | 38.9 | 4.2 | 53 | 62 | 36 | 41 | 9 | 29 | 62 | 0 | 68 |

| Iceland | 39.1 | 4.4 | 53 | 74 | 41 | 50 | 4 | 35 | 60 | 1 | 91 |

| Norway | 40.9 | 4.7 | 49 | 69 | 32 | 45 | 7 | 39 | 53 | 1 | 64 |

| Sweden | 41.3 | 4.3 | 42 | 61 | 32 | 38 | 7 | 26 | 66 | 0 | 69 |

| Australia | 40.5 | 3.9 | 47 | 60 | 27 | 44 | 100 | 80 | |||

| North America | 41.6 | 3.9 | 45 | 50 | 20 | 32 | 42 | 22 | 23 | 13 | 90 |

| Canada | 45.9 | 4.5 | 44 | 50 | 13 | 32 | 23 | 19 | 12 | 45 | 91 |

| USA | 39.8 | 3.6 | 45 | 50 | 22 | 32 | 49 | 24 | 27 | 0 | 90 |

| Southern Europe | 42.0 | 3.4 | 46 | 60 | 28 | 30 | 23 | 30 | 46 | 1 | 59 |

| Croatia | 40.9 | 3.2 | 49 | 59 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 44 | 21 | 1 | 71 |

| Portugal | 40.9 | 3.1 | 45 | 64 | 28 | 28 | 24 | 31 | 45 | 0 | 75 |

| Slovenia | 42.1 | 3.3 | 45 | 60 | 23 | 29 | 23 | 38 | 38 | 1 | 40 |

| Spain | 42.6 | 3.7 | 45 | 59 | 29 | 29 | 18 | 22 | 58 | 2 | 59 |

| Eastern Europe | 38.9 | 3.6 | 48 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 22 | 28 | 44 | 5 | 69 |

| Czech Republic | 38.6 | 3.2 | 48 | 55 | 31 | 30 | 5 | 15 | 75 | 5 | 75 |

| Hungary | 39.6 | 2.9 | 46 | 64 | 28 | 34 | 8 | 30 | 61 | 1 | 64 |

| Latvia | 38.1 | 4.2 | 49 | 69 | 39 | 29 | 10 | 40 | 48 | 3 | 78 |

| Lithuania | 39.4 | 4.0 | 51 | 65 | 35 | 28 | 16 | 62 | 21 | 1 | 72 |

| Poland | 39.3 | 4.0 | 47 | 68 | 32 | 38 | 65 | 17 | 2 | 16 | 65 |

| Russia | 36.8 | 4.1 | 46 | 72 | 38 | 28 | 10 | 35 | 49 | 6 | 72 |

| Slovak Republic | 40.3 | 3.3 | 48 | 62 | 27 | 36 | 44 | 21 | 30 | 5 | 55 |

| South Africa | 39.4 | 2.8 | 37 | 64 | 53 | 41 | 65 | 17 | 5 | 14 | 72 |

| Asia | 38.3 | 3.2 | 44 | 81 | 47 | 57 | 43 | 31 | 26 | 0 | 64 |

| India | 31.9 | 2.1 | 54 | 87 | 58 | 60 | 52 | 40 | 8 | 0 | 50 |

| Israel | 38.9 | 3.6 | 36 | 84 | 53 | 66 | 29 | 30 | 40 | 1 | 74 |

| Japan | 42.0 | 3.8 | 42 | 66 | 29 | 41 | 7 | 70 | 23 | 1 | 70 |

| Philippines | 37.8 | 2.7 | 42 | 92 | 58 | 69 | 87 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 40 |

| South Korea | 41.9 | 4.0 | 46 | 72 | 32 | 44 | 26 | 18 | 55 | 0 | 88 |

| Central/South America | 37.9 | 2.6 | 50 | 79 | 51 | 51 | 48 | 22 | 24 | 6 | 79 |

| Argentina | 37.5 | 2.0 | 46 | 78 | 40 | 47 | 33 | 26 | 23 | 18 | 93 |

| Chile | 38.7 | 2.8 | 49 | 78 | 43 | 47 | 32 | 22 | 43 | 2 | 69 |

| Mexico | 37.3 | 2.6 | 52 | 76 | 58 | 53 | 69 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 73 |

| Venezuela | 38.0 | 2.8 | 52 | 87 | 63 | 59 | 51 | 29 | 20 | 0 | 93 |

| Total | 39.7 | 3.6 | 47 | 66 | 35 | 41 | 26 | 28 | 40 | 7 | 67 |

Other individual-level control variables were respondent’s age, education, gender, and place of residence (rural/urban). Our age groups are 18–25 (reference), 26–30, 31–35, 36–40, 41–45, 46–50, and 51–55. The ISSP standardizes completed categories of education across countries, and we used these categories as a continuous variable. The average education level was higher than postsecondary in Western and Northern Europe, higher than upper secondary in Australia, North America, Southern and Eastern Europe, and Asia, but somewhat less than upper secondary in Central/South America and South Africa. We included a control for respondent’s gender to capture differences in how men and women perceive and report work hours (see also Sect. 5.1).

Contextual Independent Variables

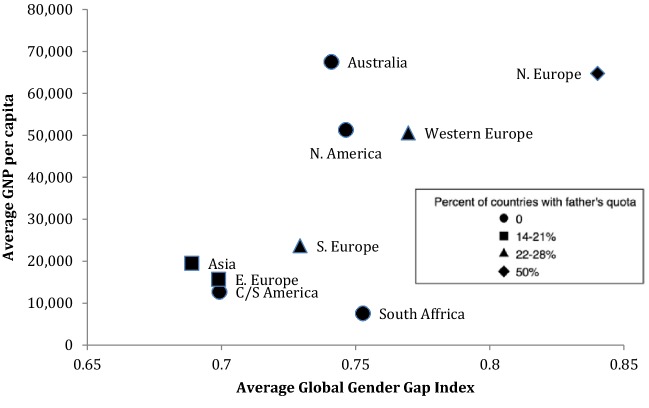

We measured the context of gender equality using the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index (GGG) (Hausmann et al. 2014). The GGG measures how much of men’s relative advantage has been closed in (1) health, (2) education, (3) economy, and (4) politics, and hence focuses entirely on the public sphere of the gender revolution (Table 4). We measured socioeconomic development using per capita gross national income (GNI) in 2012 (World Bank 2017). We employed two family policy variables: the number of weeks of paid parental leave (see “Supplementary material” Table S1), and whether there is a “fathers’ quota”, i.e. a portion of paid parental leave is reserved for fathers (Addati et al. 2014). The correlations among these contextual variables were low enough to be acceptable, with the greatest between per capita GNI and the GGG (0.59). Although having a fathers’ quota was more common in higher-income countries, the GNI range was wide in both countries that provided one ($13,947–$99,636) and countries that did not ($1485–$83,295). (See Sect. 5.2 for sensitivity analyses using alternative measures of the contextual variables.)

Table 4.

Contextual variables: variables in the main models in bold, variables used for robustness check in plain text

| Region/country | Gender equality | Family policy | National income in 10,000s | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Gender Gap Index | 1-Gender Inequality Index | 1-Gender Inequality Index with labour force component removed | Weeks of fully paid parental leave | Paid leave reserved for fathers? | Any leave reserved for fathers? | Weeks of paid maternity leave | Weeks of paid paternity leave | Index of preschool affordability | Weeks of vacation or sick leave | GNI per capita 2012 | GNI per capita PPP 2012 | |

| Western Europe | ||||||||||||

| Austria | 0.727 | 0.898 | 0.847 | 31.1 | No | No | 16.0 | 0.0 | 65.4 | 10.0 | 4.835 | 4.322 |

| Belgium | 0.781 | 0.932 | 0.922 | 12.8 | Yes | Yes | 11.7 | 1.7 | 78.5 | 9.3 | 4.708 | 4.332 |

| France | 0.759 | 0.917 | 0.873 | 13.6 | Yes | Yes | 16.0 | 2.2 | 76.6 | 24.5 | 4.093 | 3.646 |

| Germany | 0.778 | 0.925 | 0.889 | 34.8 | No | No | 14.0 | 0.0 | 66.6 | 29.7 | 4.393 | 4.137 |

| Ireland | 0.785 | 0.879 | 0.819 | 0.0 | No | Yes | 20.8 | 0.0 | 52.5 | 6.9 | 4.839 | 3.511 |

| Netherlands | 0.773 | 0.943 | 0.944 | 0.0 | No | Yes | 14.0 | 0.4 | 70.7 | 20.2 | 5.250 | 4.767 |

| Switzerland | 0.780 | 0.943 | 0.916 | 0.0 | No | No | 11.2 | 0.0 | 70.4 | 5.0 | 8.330 | 5.487 |

| Northern Europe | ||||||||||||

| Finland | 0.845 | 0.925 | 0.883 | 21.8 | No | No | 12.6 | 6.5 | 84.2 | 24.0 | 4.724 | 3.821 |

| Iceland | 0.859 | 0.911 | 0.857 | 5.6 | No | No | 10.4 | 14.4 | 82.6 | 36.0 | 4.422 | 3.355 |

| Norway | 0.837 | 0.935 | 0.898 | 49.0 | Yes | Yes | 36.0 | 1.4 | 92.4 | 28.1 | 9.964 | 6.403 |

| Sweden | 0.817 | 0.945 | 0.916 | 56.0 | Yes | Yes | 11.2 | 1.6 | 86.7 | 16.9 | 5.713 | 4.316 |

| Australia | 0.741 | 0.885 | 0.824 | 7.3 | No | No | 0.0 | 1.1 | 60.6 | 2.5 | 6.751 | 4.317 |

| North America | ||||||||||||

| Canada | 0.746 | 0.881 | 0.812 | 19.3 | No | No | 8.3 | 0.0 | 51.9 | 6.0 | 5.102 | 4.154 |

| USA | 0.746 | 0.744 | 0.613 | 0.0 | No | Yes | 0.0 | 0.0 | 63.0 | 0.0 | 5.150 | 5.061 |

| Southern Europe | ||||||||||||

| Croatia | 0.708 | 0.821 | 0.730 | 0.0 | No | No | 34.0 | 1.4 | 65.0 | 15.2 | 1.324 | 1.976 |

| Portugal | 0.724 | 0.884 | 0.797 | 20.4 | Yes | Yes | 17.0 | 4.0 | 53.0 | 10.5 | 2.115 | 2.645 |

| Slovenia | 0.744 | 0.920 | 0.877 | 33.3 | No | No | 15.0 | 5.3 | 52.5 | 12.2 | 2.249 | 2.647 |

| Spain | 0.733 | 0.897 | 0.849 | 0.0 | No | Yes | 16.0 | 3.0 | 60.6 | 22.5 | 2.899 | 3.178 |

| Eastern Europe | ||||||||||||

| Czech Republic | 0.674 | 0.878 | 0.823 | 109.2 | No | No | 19.6 | 0.0 | 66.5 | 28.0 | 1.967 | 2.455 |

| Hungary | 0.676 | 0.753 | 0.666 | 93.6 | No | No | 16.8 | 1.0 | 54.2 | 17.6 | 1.286 | 2.199 |

| Latvia | 0.769 | 0.784 | 0.670 | 109.2 | Yes | Yes | 12.8 | 1.6 | 60.0 | 8.4 | 1.395 | 2.102 |

| Lithuania | 0.721 | 0.843 | 0.753 | 73.0 | No | No | 18.0 | 6.0 | 77.6 | 4.8 | 1.417 | 2.276 |

| Poland | 0.705 | 0.860 | 0.793 | 52.0 | No | No | 26.0 | 2.8 | 56.5 | 13.2 | 1.288 | 2.092 |

| Russia | 0.693 | 0.688 | 0.540 | 29.6 | No | No | 20.0 | 0.0 | 36.0 | 6.4 | 1.409 | 2.276 |

| Slovak Republic | 0.681 | 0.829 | 0.744 | 45.8 | No | No | 22.1 | 0.0 | 59.0 | 8.0 | 1.715 | 2.437 |

| South Africa | 0.753 | 0.537 | 0.371 | 0.0 | No | No | 10.2 | 0.6 | 36.9 | 11.4 | 0.759 | 1.119 |

| Asia | ||||||||||||

| India | 0.646 | 0.390 | 0.264 | 0.0 | No | No | 12.0 | 0.0 | 19.5 | 6.4 | 0.149 | 0.384 |

| Israel | 0.701 | 0.856 | 0.774 | 0.0 | No | Yes | 14.0 | 0.0 | 58.8 | 3.6 | 3.252 | 2.807 |

| Japan | 0.658 | 0.869 | 0.814 | 52.0 | Yes | Yes | 9.3 | 0.0 | 57.2 | 5.2 | 4.668 | 3.632 |

| Philippines | 0.781 | 0.582 | 0.432 | 0.0 | No | No | 9.0 | 1.4 | 24.8 | 3.0 | 0.259 | 0.440 |

| South Korea | 0.640 | 0.847 | 0.781 | 20.8 | No | No | 13.0 | 0.0 | 64.0 | 5.0 | 2.464 | 3.089 |

| Central/South America | ||||||||||||

| Argentina | 0.732 | 0.620 | 0.480 | 0.0 | No | No | 13.0 | 0.4 | 39.4 | 5.0 | 1.468 | |

| Chile | 0.698 | 0.640 | 0.501 | 12.0 | No | No | 18.0 | 1.0 | 62.1 | 6.0 | 1.525 | 2.159 |

| Mexico | 0.690 | 0.618 | 0.492 | 0.0 | No | No | 12.0 | 0.0 | 36.3 | 2.8 | 0.982 | 1.663 |

| Venezuela | 0.685 | 0.534 | 0.371 | 0.0 | No | No | 26.0 | 2.0 | 68.0 | 4.0 | 1.273 | 1.312 |

Methods

Description: Individual-Level Regressions, Separately by World Region

We provide a descriptive picture of variation in how children are associated with couples’ division of labour using the nine world regions shown in Table 1 rather than the 35 individual countries.5 First, we used logistic regression models employing the individual-level controls listed above to predict the proportion of couples with and without children having a modern division of domestic work in each region. Next, we used multinomial logistic regression models predicting our four categories of work-family sharing [traditional, neotraditional, her second shift, and modern (reference)] to describe regional variation in the labour sharing arrangements that are more prevalent among couples with children.

Endogeneity

When using cross-sectional data like the ISSP, we cannot address, as others have (Morgan and Waite 1987; Barber and Axinn 1998; Berrington et al. 2008), whether couples change their labour sharing configurations when a child comes along; we only measure whether the presence of children is associated with a less modern division of labour and greater prevalence of the other arrangements. Our estimated coefficients may include a component contributed by endogeneity because the ability to implement fertility desires may be affected by the gendered division of labour. At the country level, the relationship between gender equality and fertility is curvilinear, with the lowest fertility at intermediate levels of gender equality (Arpino et al. 2015). At the individual level, a curvilinear relationship makes sense as well: in traditional and neotraditional couples, the couple may face relatively low opportunity costs to having a child because of the female partner’s low level of engagement with market work, but couples with a modern division of labour may also be more likely to have children when they want them because they anticipate taking on the demands of childrearing as a team rather than, for example, adding most of burden of childcare to the female partner’s second shift.

We attempted to estimate the net direction of reverse causation bias with a Two-Stage Least Squares regression, using an instrument based on ideal rather than achieved fertility; specifically, whether the number of children in the household was less than the respondent’s ideal family size. The differences in ideal fertility (preferences) across couples can be exploited as exogenous variation in the decision to have children. If the only way that couples’ labour configuration affected fertility were through fertility decisions given preferences, then we are correcting the bias introduced by reverse causality. We recognize, however, that ideal fertility itself may be influenced by the degree of difficulty in achieving work/family balance, which can be a threat to the identification strategy of this method. We therefore use this instrument only to assess the direction of bias introduced by reverse causation, but do not claim that the adjusted association between children and the division of labour is fully causal. A further discussion of our 2SLS method can be found in “Appendix”.

Multilevel Regressions

We fit a logistic 3-level null model with individuals (level 1) nested within countries (level 2) nested within world regions (level 3). No significant portion of the variance in labour sharing was explained at level 3, so we proceeded with 2-level models. Having unequal sample sizes for countries is not an issue when using multilevel random effects models with country-level variables (Thompson 2008). We added the country-level contextual variables (Sect. 3.2.3) and interactions between these and whether the couples had a child in the household to the individual-level variables. With this specification, the main effects of the contextual variables measure the links between national context and the division of labour for all couples, and the interaction terms indicate whether contextual factors have different associations with the division of labour if couples have children.

Results

Regional Patterns

Distribution of Modern Labour Sharing Across Regions

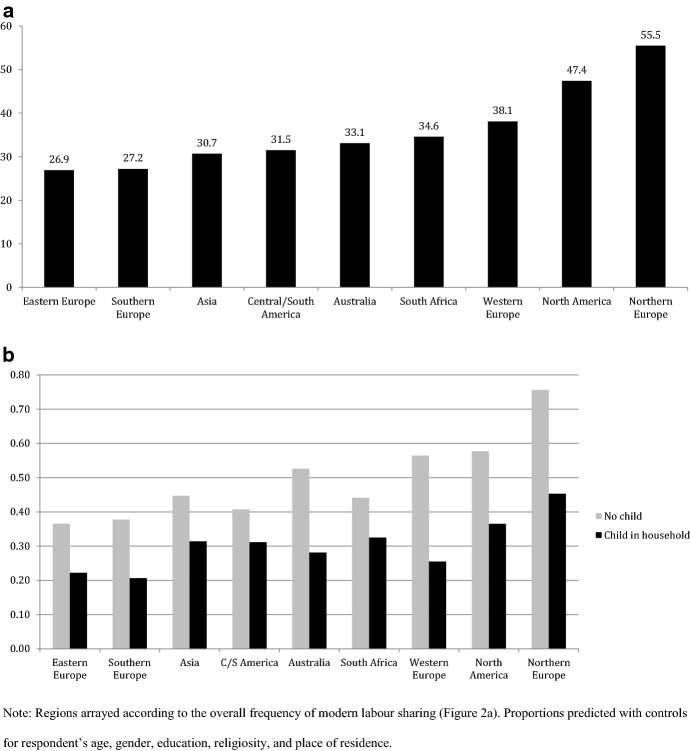

The share of couples reporting a modern work-family configuration, most of whom share approximately equally both time in the public and private spheres, was relatively low in seven of our nine regions, with most below a third. It ranged from 26.9% in Eastern Europe to 38.1% in Western Europe (Fig. 1a). Only two regions displayed levels close to half: North America (47.4%) and Northern Europe (55.5%). These comparisons do not control for individual-level factors likely to affect having a modern work-family configuration, most particularly the presence of children. The next section takes this further step.

Fig. 1.

a Percentage of couples with a “modern” work-family configuration, by Region. b Predicted probabilities of a modern division of labour for households with and without children

Regional Labour Sharing Differences Associated with Children: Predicted Probabilities

As described in Sect. 3.3.1, we used individual-level logistic regression models employing all the control variables described in Sect. 3.2.2 to predict the shares of couples with and without children practicing a modern division of labour in each region.6 These predictions, displayed in Fig. 1b, show that the proportion of couples in which the man does an at least equal share of domestic work is lower in every region of the world if there is a child in the household. The difference is statistically significant everywhere (“Supplementary material” Table S2), but the magnitude of the difference associated with children varies considerably across regions. It is relatively small in Eastern and Southern Europe, Asia, Central/South America, and South Africa. In these regions, a modern division of labour is 10–17% points lower among couples with children than those without, while it is 21–31% points lower in Australia, Western Europe, North America, and Northern Europe.

This pattern emerged not, however, because these latter regions exhibit traditional gender patterns, as we showed was not the case in Fig. 1a. Their greater gender equality turned out to be disproportionately among childless couples, whose predicted odds of choosing a modern division of labour exceeded 50% in all of the regions having large differences associated with children. Even with children, Northern Europe still had the highest proportion of couples with modern configurations; it is just that the proportion having a modern division of paid and domestic work did not exceed those of the less gender equal regions by as much when children were present than when they were not. Overall, there is much less variation between regions in the labour sharing arrangements among couples with children (the black bars in Fig. 1b; 21–45% modern) than among couples without children (the grey bars in Fig. 1b; 37–76% modern).

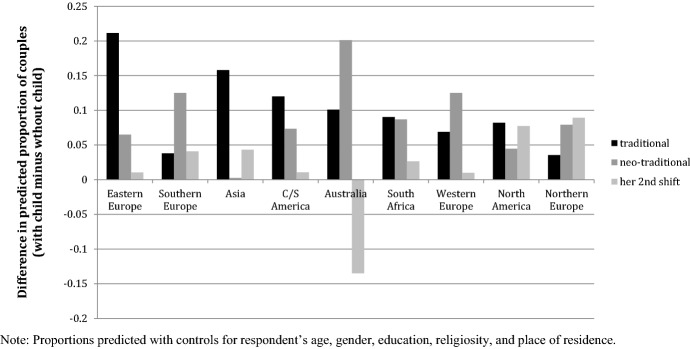

But which of the non-modern configurations is more common among couples with children? Do the less modern regions revert to the traditional configuration (women stay home)? Are the more modern regions likely to exhibit neotraditional patterns (women work part time), or even her second shift (each works full time but women do more of the extra work likely resulting from the child)? We used predictions from multinomial regressions using the same variables as in Fig. 1b, but expanded the set of outcomes to include these three configurations. We also standardized the size of the “retreat” from a modern division of labour to the average size for the whole sample, thus presenting the difference between childless couples and those with children in relative rather than absolute terms; this allowed for direct comparison between regions of the likelihood that specific alternatives to a modern division of labour would be favoured (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Standardized differences in the division of labour associated with having a child in the household

In Eastern Europe, Asia, Central/South America, and South Africa, couples with children were particularly likely to choose a traditional division of labour. These regions, along with Southern Europe, also showed less evidence of the second half of the gender revolution overall, in that their proportions of childless couples practicing a “modern” division of labour (Fig. 1b) was distinctly smaller (37–45%) than in the other regions (53–76%).

Southern Europe differed from the other four less modern regions in that children seemed to promote a neotraditional rather than fully traditional division of labour. In Asia, neotraditional arrangements were no more likely when couples had children. The presence of children was also generally associated with a greater likelihood of women carrying a second shift (maintaining equal paid work but doing at least 7 h more domestic work), but this effect was particularly small in Eastern Europe and Central/South America,

Turning to the four more modern regions, the most important contrast is in the “her second shift” category. Women are more likely to carry the second shift when children are present in North America and especially in Northern Europe, while in Western Europe children do not affect the likelihood of her second shift, and couples in Australia have a dramatically lower proportion of women carrying the second shift when they have children. Otherwise, the Australian pattern resembled that of the other three more modern regions. Couples in North America seem to favour traditional configurations when children are present, whereas in Australia, Western Europe, and Northern Europe, women with children are more likely to maintain some paid work. The factors producing the regional variations described in this section are unclear, and we turned to multilevel analysis to better understand how context shapes the patterns.

Testing for Endogeneity

We estimated the effect of having children on modern division of labour using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), and then we used Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) because of the concern that labour configurations help determine whether there is a child in the household. Our instrument is described in Sect. 3.3.2. The first column of Table 5 shows that, for the sample as a whole, there is a stronger negative association between children and modern labour sharing when we compare OLS (Panel A) to 2SLS (Panel B). This means that the association between children and the division of labour seems to be underestimated when using the baseline (OLS) regression. (Modern labour sharing seems to make couples more likely to follow through on desire to have children.)

Table 5.

Is the negative association between children and modern labour sharing exaggerated by reverse causation?

| Sample used | Dependent variable: modern division of labour | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Sample | North America | C&S America | North Europe | East Europe | West Europe | South Europe | Asia | South Africa | Australia | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

| Panel A. Ordinary least squares | ||||||||||

| Has Children | − 0.223*** (0.019) | − 0.215*** (0.042) | − 0.104** (0.033) | − 0.293*** (0.029) | − 0.151*** − (0.023) | − 0.327*** (0.017) | − 0.176*** (0.026) | − 0.129*** (0.026) | − 0.117* (0.059) | − 0.248*** (0.048) |

| Panel B. Two-stage 3 least squares | ||||||||||

| Has Children | − 0.275*** (0.039) | − 0.328*** (0.098) | − 0.238** (0.091) | − 0.203* (0.101) | − 0.160** − (0.058) | − 0.424*** (0.044) | − 0.294*** (0.072) | − 0.132† (0.068) | − 0.060 (0.165) | − 0.345** (0.112) |

| Indiv. controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| First stage F | 342.69 | 236.83 | 263.71 | 246.13 | 596.22 | 937.91 | 470.63 | 375.77 | 100.67 | 145.13 |

| Clusters | 35 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Observations | 13,404 | 577 | 1309 | 1564 | 2205 | 3376 | 1479 | 2083 | 330 | 481 |

The dependent variable is an indicator that takes the value of 1 when the male does equal or greater domestic work than the female. “Has Children” is an indicator that takes the value of 1 when the couple has at least one child. The control variables include respondent’s gender and education, age group, urban residence, and religiosity. Regressions include country-specific fixed effects, with the exception of Australia and South Africa. Standard errors are clustered at the country level for column 1, and the remaining columns show standard errors that are robust to heteroskedasticity. Coefficients that are significantly different from zero are denoted by the following system

†p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

This result, however, was not fully consistent across regions. Table 5 shows that in South Africa (column 9) and Northern Europe (column 4), the degree to which children exert a traditionalizing influence on household labour sharing is exaggerated in the baseline models. (Those with more traditional arrangements seem more likely to follow through on desire to have children.) More specifically, the estimated effect of children dropped from statistical significance in 2SLS regression in South Africa (n = 330), and its magnitude was reduced by just over 30% in Northern Europe. We proceeded without corrections in our subsequent models, but we return to the regional differences when discussing our conclusions.

Multilevel Analysis

Modern Division of Labour Versus All Others

In our multilevel analysis, we added country-level variables while employing the same individual-level controls as we did when predicting the labour sharing arrangements shown in Figs. 1b and 2. The first model in Table 6 estimates the effects associated with country context for childless couples and couples with children together. The second model adds interaction terms between the contextual variables and whether the couple has a child to test whether the association with context differs between these two groups.

Table 6.

Odds ratios from multilevel logistic regression predicting a modern division of labour

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Individual-level variables | ||

| Age (ref = 18–29) | ||

| 26–30 | 0.76** | 0.78* |

| 31–35 | 0.63*** | 0.65*** |

| 36–40 | 0.66*** | 0.69*** |

| 41–45 | 0.63*** | 0.67*** |

| 46–50 | 0.58*** | 0.62*** |

| 51–55 | 0.45*** | 0.47*** |

| Religiosity (ref = almost never) | ||

| Attends frequently | 0.81*** | 0.82*** |

| Attends infrequently | 0.77*** | 0.77*** |

| Attendance missing | 0.87 | 0.89 |

| Education | 1.16*** | 1.16*** |

| Residence (ref = rural) | 1.09† | 1.09† |

| Gender (ref = female) | 1.67*** | 1.68*** |

| Child in household | 0.35*** | 2.56 |

| Constant | ||

| Country-level variables | ||

| Global Gender Gap Index (GGG) | 42.54† | 197.14* |

| Gross national product per capita (GNP) | 0.97 | 1.05 |

| Paid parental leave | 0.99* | 0.99 |

| Fathers’ quota | 1.23 | 1.08 |

| Cross-level interactions | ||

| GGG*child in hh | 0.13* | |

| GNP*child in hh | 0.88*** | |

| Paid parental leave*child in hh | 1.00 | |

| Fathers’ quota* child in hh | 1.26* | |

| _cons | 0.07† | 0.01** |

| /lnsig2u | − 1.17 | − 1.21 |

| sigma_u | 0.56 | 0.55 |

| rho | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| LR test of rho = 0: chibar2(01) = | 681.53*** | 655.24*** |

| Log likelihood = | − 7856.51 | − 7823.31 |

| n, individuals | 13,404 | 13,404 |

| n, countries | 35 | 35 |

†p ≤ 0.10; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.00

Overall, couples are 35% as likely to have a modern labour sharing arrangement when children are present (Table 6, Model 1). As expected, modern labour sharing was also more likely in countries with more public sphere gender equity (p ≤ 0.10). The range on the Global Gender Gap Index (GGG) is from 0.64 (South Korea) to 0.86 (Iceland). With other variables at mean values, the predicted share of couples with modern labour sharing is 29% at the bottom of this range and 45% at the top of it. In contrast, couples in countries with more generous parental leave are less likely to have modern labour sharing, about 1% lower per paid week. This is probably because household specialization is encouraged when mothers take parental leave. Neither national income nor a father’s quota for parental leave had a significant effect on couples in general.

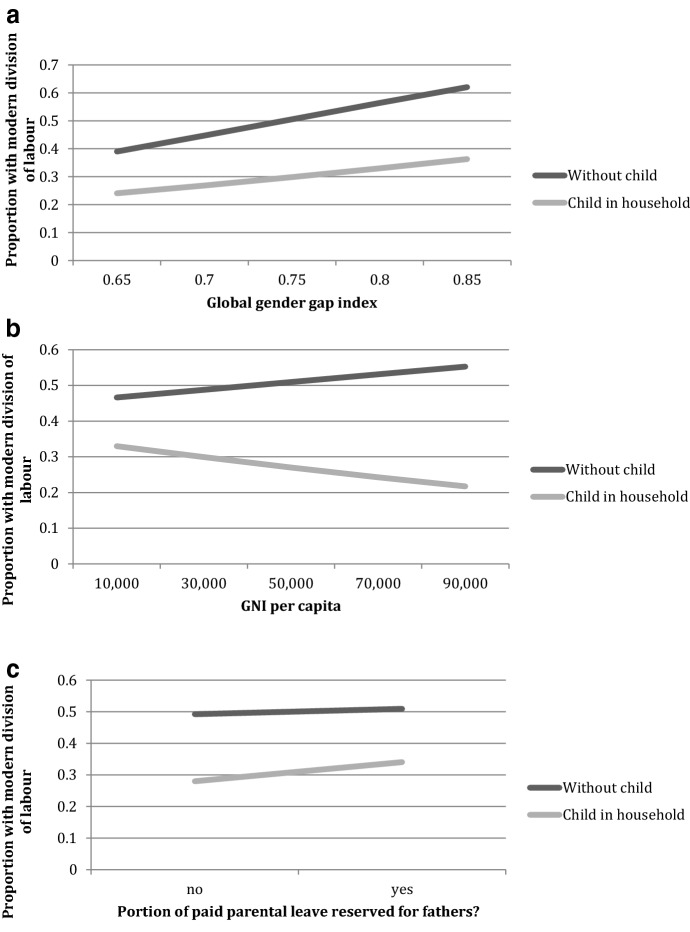

Model 2 confirms the effects of context are different when there are children in the household. Children are more strongly associated with a retreat from modern labour sharing arrangements in more gender equal countries and higher-income countries, but this association is attenuated in countries where a proportion of paid parental leave is reserved specifically for fathers. The magnitude of these results is expressed graphically in Fig. 3 and discussed below.

Fig. 3.

a Couples’ division of labour and national gender equality. b Couples’ division of labour and national income. c Couples’ division of labour and family policy

First, while all couples are more likely to participate in modern labour sharing in countries with greater gender equality, Fig. 3a shows that couples with children are less likely to have modern labour configurations everywhere, but the difference associated with children is the greatest in the most gender equitable countries. This runs counter to our hypothesis that the demands of childrearing would be more equally shared in countries with greater gender equality.

Figure 3b shows, as expected, that children seem to present a more substantial barrier to the gender revolution in higher-income countries. As with gender equality, the association between children and the division of labour is greater at more advanced levels of national income. In the case of national income, the effect associated with children swamps the main effect: couples with children are less likely to have a modern division of labour in higher-income countries than lower-income countries (the bottom line in Fig. 3b is sloped downward).

While the amount of paid parental leave does not affect childless couples and couples with children any differently, having a portion of paid leave reserved for fathers does (Fig. 3c). Among couples with children, 28% have modern configurations in countries without a father’s quota, while 34% do in countries that reserve a portion of parental leave for fathers.

We re-estimated model 2 of Table 6 controlling for country-specific fixed effects to address the concern that determinants of childlessness may vary greatly across our diverse sample.7 The only change in our results upon introducing country fixed effects was that the interaction between children and national gender equity became significant only at 0.059, but it remained substantively huge (odds ratio 0.14). We are therefore confident that our estimates of how context matters differently for couples with children are not driven by country-specific patterns of selection into childlessness.

Modern Division of Labour Compared to Specific Alternatives

Overall, the contextual variables that identified the settings in which children are most strongly associated with a retreat from modern labour sharing generally predicted the three other configurations in similar ways (results available upon request). There was, however, one important difference: the same fathers’ quota that was associated with lower likelihood of traditional and neotraditional labour sharing among couples with children was associated with a higher likelihood of the woman carrying the second shift. Traditional configurations were 45% as likely among couples with children in countries having a fathers’ quota than in countries without, and neotraditional arrangements were 68% as likely. In sharp contrast, the likelihood of the female partner carrying the second shift was 4% higher among couples with children when there was a father’s quota.

Sensitivity Analyses

Individual Data

We checked whether our results were sensitive to individual-level measurement issues: ages and numbers of children and proxy reporting. Our results did not depend much on the ages and numbers of children, except that the higher rates of modern labour sharing among parents in countries with a father’s quota obtained only if two or more children were in the household. Proxy reporting also had little impact on the results: men were more likely to report modern labour sharing than women (except in Australia), but differences associated with the presence of children were largely consistent across men’s and women’s reports.

Contextual Variables

We also checked whether the results for our contextual variables were consistent across different operationalizations of the same concepts. When we substituted the United Nation’s Gender Inequality Index (GII)8 for the GGG, the main effect of national gender equality was not statistically significant. The interaction terms, however, were not affected: the retreat from a modern division of labour among couples with children was still particularly pronounced in the more gender equal countries and wealthier countries, but less so if there were a fathers’ quota for parental leave. Our results were not sensitive to whether GNI per capita was measured using official exchange rates or using purchasing power parity, nor to whether national income (by either measure) was logged. We also implemented a model testing for non-linearity in the effect of national gender equality, including GGG2 and GGG2*child in household (see Arpino et al. 2015). The added terms were not statistically significant.

With respect to family policy measures, we experimented with including paid maternal leave, paid paternal leave (both from Addati et al. 2014), the amount of vacation and sick leave (OECD 2015), and the affordability of preschool (Economist Intelligence Unit 2012), adding these variables both individually and simultaneously. Having paid parental leave reserved for fathers was significantly and positively related to the odds of a modern division of labour among couples with children in all models. (the range of p values across models was from 0.008 to 0.067.) We tested whether the father’s quota continued to have this effect if it was unpaid, and it did not.

Discussion

Parents’ division of paid and domestic work is more similar across world regions than the division practiced by childless couples. Children used to be a barrier to the first half of the gender revolution (women’s paid labour force participation), but much less so in contemporary societies. We explored the extent to which children seem to present a barrier to the second half of the gender revolution (men’s participation in domestic work), and what contextual factors are associated with how much children matter. We found that where the division of labour among childless couples is more traditional, children do not seem to add much to traditionalism; where childless couples are more modern, children seem to present a greater challenge to maintaining modern labour sharing. Our work uncovered this general pattern, and in this section we (1) relate the contextual variables to the regional patterns and (2) discuss why the contextual variables have different associations with labour sharing patterns among parents than among couples without children in the household.

Do the Contextual Variables Explain Regional Patterns?

In our separate analyses by world region, we observed more similar labour sharing arrangements between parents and non-parents in Central/South America, Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, Asia, and South Africa, than in Australia, Western Europe, North America, and Northern Europe. The contextual variables from our analysis help explain this variation across regions.

Specifically, looking at Fig. 4, our multilevel results would predict that regions toward the bottom left corner with lower income and less gender equality would have smaller differences in labour sharing configurations between parents and non-parents, plus that father’s quotas would also be associated with smaller gaps (make regions look more like those further toward the bottom left corner). The five regions with smaller differences in labour sharing configurations associated with parenthood are in fact clustered toward the bottom left of Fig. 4. Further, policy reserving a portion of paid parental leave for fathers is absent in North America and Australia (except in Quebec, a province comprising about 23% of the 2012 Canadian population). Thus, it is not surprising that the proportion of parents practicing a modern division of labour turns out to be virtually identical among North America, Australia, and the five less modern regions. A larger share of parents have modern labour configurations in Northern Europe, despite its very high levels of gender equality and national income, and despite the association between children and labour sharing being exaggerated there by reverse causation (traditional labour sharing making it more likely that couples will achieve their ideal family size, Sect. 4.1.3). Father’s quotas are the most common in Northern Europe.

Fig. 4.

Contextual variables by region

The contextual variables also predict regional differences in fully traditional labour sharing associated with the presence of children, but they are less helpful predicting the contexts in which neotraditional or her second shift arrangements will be especially common among parents. For instance, neotraditional arrangements are no more common when there is a child in the household in Asia, and our multilevel model does nothing to explain why. The quality of available part-time work surely differs in ways not measured by these variables and may also help explain why neotraditional configurations are not more commonly chosen among parents in North America.

Similarly, Australian women with children are actually less likely to be burdened with the “second shift” than childless women are. Here, children seem to push back on the first half of the gender revolution (women’s participation in paid work), making traditional and neotraditional arrangements more likely than ones where paid work is equally shared. In contrast, Northern Europe stands out as the region where the presence of children is associated with a greatest likelihood of women carrying the second shift. Here, the chances of a modern division of paid labour are not strongly related to the presence of children, but domestic labour sharing is more gendered among parents, thus leaving many women with a second shift.

Understanding How Context Influences Parents

Why is the difference in labour sharing between parents and couples with children in the home greater in richer and more gender equal countries, particularly those that do not structure parental leave to encourage fathers’ involvement at home? One explanation is that in less equal societies, women commonly adopt traditional labour sharing patterns when they form unions (Anxo et al. 2011), so the arrival of children has little additional impact. Where equality is more normative, union formation alone does not present a substantial barrier to the gender revolution. Similarly, where childbearing is a less optional part of the adult life course, the division of labour among childless couples may reflect the expectation of future children to a greater degree than where remaining childless is a more socially acceptable option.

We further contend that egalitarian norms shape the behaviour of childless couples more forcefully than they shape the behaviour of couples with children. One simple reason for this is that it is easier to divide a small amount of domestic work in an egalitarian fashion than it is to equally divide the greater hours small children require. Further, home production may be favoured by parents as restaurant meals and commercial laundry become very expensive in high volume. By increasing the total amount of domestic work required, children encourage specialization. It is hardly surprising that such a force would push back toward more traditional gender roles during an incomplete gender revolution.

It is, of course, not necessary for more domestic work to fall disproportionately on women. It might seem that in the most gender equal countries, there would be the greatest chance that the additional time demands associated with children would be equally shared. Our results indicate that, at least at this point in the gender revolution, egalitarianism is less likely among couples with children (see Hart et al. 2017 who also discuss how couples with children have a more difficult time living up to the ideals of a modern relationship.)

Children also seem to affect the household division of labour more in higher-income countries, and we suspect that a large part of the explanation for this can be found in the intensive parenting norms that are common in higher-income countries (Coltrane 1997; Lareau 2011; Bianchi et al. 2012). The time demands associated with intensive parenting seem to have fallen more heavily on mothers than fathers. Investments in children generally increase with lower fertility (Becker and Lewis 1974), but the degree to which these investments include intensive parenting rather than being primarily investments in education also depends on context (Sayer and Gornick 2012).

The generosity of state supports for families did little to condition the differences in labour sharing configurations associated with having children in the household. Overall, the difference in the likelihood of a modern division of labour associated with children did not depend on the amount of paid parental leave, nor did it depend on overall benefits, nor on most specific benefits (Sect. 5.2). Thus while outsourcing can promote gender equality in the private sphere, it is not enough for welfare states to promote “de-familialization” by financially supporting alternatives to private care (Esping-Andersen 2000). The only policy we identified that seemed to support men being at least equally involved in domestic work was having a portion of paid parental leave reserved specifically for fathers. And even here, our results present a policy challenge: having a fathers’ quota in parental leave policy makes both traditional and neotraditional arrangements less likely, and it increases the probability of modern labour sharing among parents—but it also increases the probability that mothers will carry a second shift. In other words, a fathers’ quota seems to support mothers’ participation in the first half of the gender revolution, but it seems less effective in promoting the second half. It is, of course, possible that public support for policies supporting involved fatherhood is greater in countries where men are already more involved, but implementation of a father’s quota can create stronger norms for father involvement (Lappegård 2017, personal communication). Research from Canada supports the idea that it is combination of financial benefits and the labelling of “daddy-only” weeks that seems to evoke change in the division of domestic work: even though couples left some portion of paid parental leave “on the table” prior to the introduction of a father’s quota in Quebec, its introduction led to more fathers taking parental leave, and a more egalitarian division of domestic work (Patnaik 2016).

Limitations

Work such as ours based on cross-sectional data does not, of course, measure how much the division of labour changes when a child enters the family. When we compare couples with and without children, the estimates may be biased by selection and endogeneity. Couples that are more traditional in ways not controlled by our religiosity variable may be more likely to have children. We corrected for endogeneity bias introduced by differential preference implementation, but work/family balance issues may also influence fertility preferences (not just their implementation). Therefore, the link between children and labour configurations does not result solely from children having a causal impact.

In addition, time diaries would have provided superior measures of time allocation compared to the weekly recall data we used (especially given that respondents reported on partners’ time use). Another limitation is that we were unable to identify parents currently utilizing maternity, paternity, or parental leave—those whose current care work hours are likely higher than usual. This does not seem to be of great concern as we would expect this measurement error to disproportionately impact those with the youngest children, and yet our results were not sensitive to the age of children in the household (Sect. 5.1).

Conclusion

We started this investigation assuming that even though children increase mothers’ workload more than fathers’ at this point in an incomplete gender revolution, that children would likely present the least substantial barriers to the gender revolution in the most progressive countries. We found that children are more strongly associated with more traditional labour sharing in countries with higher national income and greater national gender equality.

Nonetheless, when family policy is structured so that couples lose a portion of paid parental leave if they do not share it, mothers are less likely to retreat from paid hours (see also Oláh et al. 2017). Unfortunately, the same policy is associated with a greater likelihood of mothers carrying a second shift at home. This highlights the fact that the second half of the gender revolution—equal participation in domestic work—is more difficult to achieve with children than the first half (equal participation in paid work). To the extent that the second half of the gender revolution promotes fertility (McDonald 2000; Neyer et al. 2013; Esping-Andersen and Billari 2015; Anderson and Kohler 2015), progress toward private sphere equality becomes more difficult as it goes along. Even though higher fertility seems to make egalitarianism more difficult, the countries of northern Europe have managed both to achieve the highest levels of gender sharing at work and at home and to maintain near-replacement fertility (Castles 2003; Rindfuss et al. 2016). This combination may be attainable more broadly through family policies that support men’s role as nurturers of children.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Electronic supplementary material 1 (DOCX 25 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by the Social Trends Institute (New York and Barcelona), the Institute for Family Studies, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Center for Child Health and Human Development grant R24-HD041041, Maryland Population Research Center. Earlier work using some of the same conceptualization as in this paper is available from http://worldfamilymap.ifstudies.org/2015/articles/essay-2.

Appendix: Implementation of Two-Stage Least Squares

We attempt to estimate the following model:

where is an indicator of whether respondent i has a modern configuration of labour, is an indicator of whether respondent i has children, and represents a vector of controls of respondent i. This equation has a causal interpretation and is known as the structural equation.

The problem, however, is that is most likely an endogenous regressor. That is, it may be correlated with the error term due to the fact that couples’ labour configurations can affect fertility decisions. A solution to this is to find an exogenous regressor, which in our case is , that is uncorrelated with but correlated with the endogenous variable . More specifically, for this instrument to be valid it must be correlated with the endogenous variable and is exogenous in the structural equation, i.e. it does not influence labour configurations except through fertility decisions given preferences.

If this variable satisfies those requirements, then it can be used to “cleanse” the endogeneity by using predicted values based on the exogenous variables only. In other words, we are decomposing the variation of into an exogenous and endogenous part. This is known as the first stage regression, which can be represented by the following equation:

The next step would be to estimate the structural equation using the predicted values of the first stage regression (). This is known as the second stage regression, which can be represented by the following equation:

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards”. Human subjects: this research involved human subjects, but is exempt from IRB review because it used only publically available data with no personal identifiers. (Exemption 4) Data available from: https://dbk.gesis.org/dbksearch/sdesc2.asp?ll=10¬abs=&af=&nf=&search=&search2=&db=e&no=5900.

Informed Consent

The original collectors of the data obtained informed consent.

Footnotes

Ideally, we would have imposed this age restriction on both partners in the couple, but the respondent’s partner’s age was not available in Austria, Hungary, the Philippines, Russia, or South Africa.

The respondent’s gender is known, but the respondent’s partner’s gender is not known. By assuming that all partners are opposite-sex partners, we might slightly underestimate the extent to which division of labour falls along gendered lines.

Number of children and their ages are considered in sensitivity analyses, Sect. 5.1. The sample includes biological parents as well as an unknown number of other families, e.g., step-parents and grandparents whose grandchildren live with them. We use the term “parents” for the sake of brevity to describe all those with a residential partner who also live with children.

This nonlinear relationship may reflect more follow through on fertility ideals among couples with modern labour sharing configurations, as described in Sect. 3.3.2: the least religious were the most likely to disagree with the statement “A man’s job is to earn money; a woman’s job is to look after the home and family”, and they were still more likely to have children than infrequent attenders.

We note that the Asian region is particularly heterogeneous (Japan, South Korea, India, The Philippines, and Israel).

The effects of the control variables are generally consistent with prior research (“Supplementary material” Table S2): age and frequent religious service attendance have negative effects on the odds of a modern work-family configuration; education and urban residence have positive effects; and men report a modern configuration more often than women. The effects are also generally similar across regions, with the exception of Asia, the most heterogeneous region.

Introducing fixed effects eliminated our ability to estimate the effects of national income and other contextual variables, because the country dummies used up all of the degrees of freedom available at the country-level. We nonetheless retained the ability to estimate the interaction between our contextual variables and individual-level variable for children in the household.

Because both the GGG and the GII incorporate measures of labour force participation, and are therefore potentially endogenous with couples’ division of labour, we also recalculated the GII using the UN’s methodology (UNDP 2013), but including only health and empowerment components. This did not affect the results.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Laurie F. DeRose, Email: Lderose@umd.edu

Frances Goldscheider, Email: frances_goldscheider@brown.edu.

Javiera Reyes Brito, Email: jreyesb@uandes.cl.

Andrés Salazar-Arango, Email: andres.salazar@unisabana.edu.co.

Paúl Corcuera, Email: paul.corcuera@udep.pe.

Paúl J. Corcuera, Email: paulj.corcuera@udep.pe

Montserrat Gas-Aixendri, Email: mgas@uic.es.

References

- Addati, L., Cassirer, N., & Gilchrist, K. (2014). Maternity and paternity at work: Law and practice across the world. Geneva: International Labour Office. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_242615.pdf. Accessed 22 April 2017.

- Adserà A. Fertility, feminism and faith: How are secularism and economic conditions influencing fertility in the West. In: Kaufmann E, Wilcox WB, editors. Whither the child? Causes and consequences of low fertility. Colorado: Paradigm Press; 2013. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson T, Kohler H-P. Low fertility, socioeconomic development, and gender equity. Population and Development Review. 2015;41(3):381–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anxo D, Mencarini L, Pailhé A, Solaz A, Tanturri ML, Flood L. Gender differences in time use over the life course in France, Italy, Sweden, and the US. Feminist Economics. 2011;17(3):159–195. [Google Scholar]

- Arpino B, Esping-Anderson G, Pessin L. How do changes in gender role attitudes towards female employment influence fertility? A macro-level analysis. European Sociological Review. 2015;31(3):370–382. [Google Scholar]

- Barber JS, Axinn WG. Gender role attitudes and marriage among young women. The Sociological Quarterly. 1998;39(1):11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter J. Gender equality and participation in housework: A cross-national perspective. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1997;28(3):220–247. [Google Scholar]

- Beck U, Beck-Gernsheim E. The normal chaos of love, trans. Mark Ritter and Jane Wiebel. Oxford: Polity Press; 1995. p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. Human capital, effort, and the sexual division of labor. Journal of Labor Economics. 1985;3(1):33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS, Lewis HG. Interaction between quantity and quality of children. In: Schultz TW, editor. Economics of the family: Marriage, children, and human capital. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1974. pp. 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Berrington A, Hu Y, Smith PW, Sturgis P. A graphical chain model for reciprocal relationships between women’s gender role attitudes and labour force participation. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 2008;171(1):89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Milkie MA. Work and family research in the first decade of the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(3):705–725. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Sayer LC, Milkie MA, Robinson JP. Housework: Who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Social Forces. 2012;91(1):55–63. doi: 10.1093/sf/sos120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair-Loy M, Hochschild A, Pugh AJ, Williams JC, Hartmann H. Stability and transformation in gender, work, and family: Insights from the second shift for the next quarter century. Community, Work & Family. 2015;18(4):435–454. [Google Scholar]

- Blofield M, Martínez F. Trabajo, familia y cambios en la política pública en América Latina: equidad, maternalismo y corresponsabilidad [Work, family, and changes in public policy in Latin America: Equity, mothering, and responsibility] CEPAL Review. 2014;114:107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Boeckmann I, Misra J, Budig MJ. Cultural and institutional factors shaping mothers’ employment and working hours in postindustrial countries. Social Forces. 2015;93(4):1301–1333. [Google Scholar]

- Budig Michelle. The Blackwell Companion to the Sociology of Families. Malden, MA, USA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007. Feminism and the Family; pp. 416–434. [Google Scholar]