Abstract

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are common among Hajj pilgrims, but risk factors for RTIs and respiratory pathogen acquisition during the Hajj are not clearly identified. Based on previous studies, most frequent pathogens acquired by Hajj pilgrims were investigated: rhinovirus, human coronaviruses, influenza viruses, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. 485 pilgrims were included. 82.1% presented with RTIs. Respiratory chronic diseases were associated with cough, Influenza-like illness (ILI) and the acquisition of H. influenzae. Vaccination against invasive pneumococcal diseases (IPD) and influenza was associated with a decrease in the acquisition of S. pneumoniae and prevalence of ILI (aRR = 0.53, 95%CI [0.39–0.73] and aRR = 0.69, 95%CI [0.52–0.92] respectively). Individuals carrying rhinovirus and H. influenzae-S. pneumoniae together were respectively twice and five times more likely to have respiratory symptoms. Individual with H. influenzae-K. pneumoniae carriage were twice (p = 0.04) as likely to develop a cough. The use of disposable handkerchiefs was associated with a decrease in the acquisition of S. aureus (aRR = 0.75, 95%CI [0.57–0.97]). Results could be used to identify pilgrims at increased risk of RTIs and acquisition of respiratory pathogens. Results also confirm the effectiveness of influenza and IPD vaccinations in reducing ILI symptoms and acquisition of S. pneumoniae carriage respectively.

Subject terms: Risk factors, Molecular biology

Introduction

The Hajj is one of the largest annual religious mass gatherings in the world. Each year, Saudi Arabia attracts over 2 million pilgrims from over 180 countries, including about 2,000 from Marseille, France1. The Hajj presents major challenges in public health and infection control as the crowding conditions favor the acquisition, dissemination and transmission of pathogenic microorganisms2. Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are particularly frequent during the pilgrimage and are responsible for most causes of hospitalization, with community-acquired pneumonia being a major cause of serious illness among pilgrims3. Many studies have been conducted among Hajj pilgrims over the last decade, demonstrating the high prevalence of respiratory symptoms and the frequent acquisition of respiratory pathogens3–7. The viruses most commonly acquired after the Hajj are human rhinovirus (HRV), human coronaviruses (HCoV) and influenza A virus (IAV). The most frequently acquired respiratory bacteria are Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae)3. However, the etiology of RTIs at the Hajj is likely multifactorial and complex. The potential effects of vaccination against influenza and pneumococcus8,9, of non-pharmaceutical preventive measures including face-mask use and hand hygiene practice10–12 have been investigated, mostly based on clinical criteria, but results of studies are contradictory.

So far, to our knowledge, risk factors for pathogen acquisition during the Hajj are not clearly identified. Relationship between respiratory symptoms and carriage of respiratory pathogens at the Hajj also remain poorly understood making it difficult distinguishing between infection and colonization. We conducted this study to identify risk factors for respiratory symptoms and respiratory pathogens carriage at the Hajj, including socio-demographics, vaccination against influenza and invasive pneumococcal diseases (IPD) and adherence to non-pharmaceutical preventive measures using data collected from 2014 to 2017. We also evaluated the relationship between pathogen carriage, including multiple carriage and respiratory symptoms.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

The study enrolled 485 pilgrims, 96.5% of whom filled both the pre- and post-travel questionnaires. The study population had a median age of 61.5 years (interquartile = (52 – 68 years), min = 21, max = 96 years) and a male:female ratio of 1:1.3 (Table 1). The majority (88.4%) of the pilgrims were from North Africa. 66.3% had an indication for vaccination against IPD according to the French recommendation at the time of inclusion13–20. Diabetes (28.6%) and hypertension (29.5%) were the most common comorbidities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population, Hajj pilgrims 2014-2017 (N = 485).

| Variables | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pilgrimage year | 2014 | 98 | 20.2 |

| 2015 | 119 | 24.6 | |

| 2016 | 117 | 24.1 | |

| 2017 | 151 | 31.1 | |

| Gender | Male | 212 | 43.7 |

| Female | 273 | 56.3 | |

| Age* | Median | 61.5 | |

| Interquartile | 52–68 | ||

| Min - max | 21–96 | ||

| Age ≥ 60 years* | 269 | 56.0 | |

| Place of birth | France | 40 | 8.5 |

| North Africa | 419 | 88.4 | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 13 | 2.7 | |

| Others | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Comorbidities* | Diabetes mellitus | 136 | 28.6 |

| Hypertension | 140 | 29.5 | |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 56 | 11.8 | |

| Chronic heart disease | 32 | 6.7 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5 | 1.1 | |

| Immunodefiency | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Indication for vaccination against IPD1 | 315 | 66.3 | |

| BMI2 | Normal | 130 | 26.8 |

| Underweight | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Overweight | 220 | 45.4 | |

| Obesity | 132 | 27.2 | |

1Indication for vaccination against invasive pneumococcal diseases: Age superior or equal to 60 years, diabetes mellitus, chronic respiratory disease, chronic heart disease, chronic kidney disease and immunodeficiency, (n = 475, 10 missing data).

2Body mass index. Normal weight: BMI: 18.5 – 24.9, Underweight: BMI <18.5, Overweight: BMI: 25.0 – 29.9, Obesity: BMI ≥30.

*n = 480, 5 mission data.

With regard to preventive measures, 96 (20.2%) pilgrims reported having been vaccinated against pneumococcal (PCV-13) in the last 5 years, representing 30.5% of pilgrims with an indication for IPD. 26.7% (127/466) were vaccinated against influenza before their travel or in the past year. Two hundred sixty-one (56.0%) pilgrims reported using face masks during the Hajj. Also, 42.1% (196/466), 50.4% (235/466) and 73.6% (343/466) pilgrims declared washing their hands during the Hajj more often than usual, using hand gel, and using disposable handkerchiefs during their stay in Saudi Arabia, respectively.

Clinical features

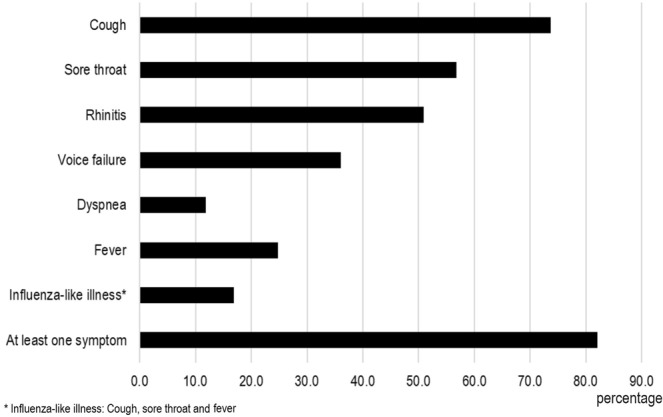

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of respiratory symptoms among pilgrims during the Hajj. More than 80% of the pilgrims presented at least one respiratory symptoms, cough, sore throat and rhinitis being the most frequent. Influenza-like illness (ILI) was present in 16.9% of pilgrims. None suffered from pneumonia or other IPD, and only one was hospitalized during the 2017 Hajj season. Time between arrival in Saudi Arabia and onset of symptoms was 9.5 ± 4.8 days (min = 0, max = 22 days).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of respiratory symptoms among pilgrims during the Hajj 2014–2017.

Detection of respiratory pathogens by qPCR

Pre- and post-Hajj specimens were collected from 456 (94.0%) and 451 (93.0%) participants, respectively. Furthermore, 32.6% (125/384) ill pilgrims were sampled at onset of respiratory symptoms. At total of 433 (89.3%) pilgrims had paired samples.

The prevalence of respiratory pathogens carriage increased after a participation in Hajj, compared to pre-Hajj status, and differences were significant for all bacterial pathogens and all viruses with the exception of HCoV-HKU1 (Table 2). Overall, 33.0% of pilgrims acquired at least one respiratory virus, notably RHV (26.9%), HCoV (8.0%) and influenza viruses (3.7%). A similar proportion (35.3%) acquired at least one respiratory bacterium after the Hajj, mainly H. influenzae (31.7%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) (20.9%), S. pneumoniae (17.9%) and S. aureus (14.0%). Overall, viral-bacterial acquisition proportion in returned Hajjes was 26.9%, the most common being H. influenzae-virus dual carriage (Table 2). Among the 125 pilgrims sampled at symptom onset, a high prevalence of HRV (47/125, 37.6%), S. aureus (35/125, 28.0%) and H. influenzae (49/125, 39.2%) carriage was observed.

Table 2.

Acquisition of respiratory pathogens during the Hajj.

| Pathogens | Pre-Hajj | Per-Hajj | Post-Hajj | Acquisition | p* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 456 | % | n = 125 | % | n = 451 | % | n | % | ||

| Viruses | |||||||||

| At least one virus | 20 | 4.4 | 54 | 43.2 | 147 | 32.6 | 147 | 33.9 | <10−4 |

| All influenza viruses | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4.8 | 11 | 2.4 | 16 | 3.7 | <10−4 |

| Influenza A | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4.0 | 8 | 1.8 | 12 | 2.8 | 5.10−4 |

| Influenza B | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.7 | 4 | 0.9 | 0.05 |

| Rhinovirus | 18 | 4.0 | 47 | 37.6 | 117 | 25.9 | 120 | 27.7 | <10−4 |

| All coronaviruses | 2 | 0.4 | 17 | 13.6 | 29 | 6.4 | 36 | 8.3 | <10−4 |

| Coronavirus 229E | 2 | 0.4 | 11 | 8.8 | 20 | 4.4 | 27 | 6.2 | <10−4 |

| Coronavirus HKU1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.31 |

| Coronavirus NL63 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2.4 | 5 | 1.1 | 6 | 1.4 | 0.01 |

| Coronavirus OC43 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3.2 | 3 | 0.7 | 6 | 1.4 | 0.01 |

| Bacteria | |||||||||

| At least one bacterium | 217 | 47.6 | 78 | 62.4 | 344 | 76.3 | 159 | 36.7 | <10−4 |

| S. aureus | 68 | 14.9 | 35 | 28.0 | 97 | 21.5 | 63 | 14.5 | 3.10−3 |

| S. pneumoniae | 18 | 4.0 | 5 | 4.0 | 89 | 19.7 | 80 | 18.5 | <10−4 |

| H. influenzae | 127 | 27.9 | 49 | 39.2 | 232 | 51.4 | 144 | 33.3 | <10−4 |

| K. pneumoniae | 58 | 12.7 | 15 | 12.0 | 115 | 25.5 | 94 | 21.7 | <10−4 |

| Bacteria co-infections | |||||||||

| H. influenzae-S. pneumoniae | 9 | 2.0 | 2 | 1.6 | 49 | 10.9 | 47 | 10.9 | <10−4 |

| H. influenzae-K. pneumoniae | 30 | 6.6 | 6 | 4.8 | 63 | 14.0 | 62 | 14.3 | <10−4 |

| H. influenzae-S. aureus | 8 | 1.8 | 14 | 11.2 | 47 | 10.4 | 52 | 12.0 | <10−4 |

| S. pneumoniae-K. pneumoniae | 4 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.8 | 23 | 5.1 | 24 | 5.5 | 2.10−4 |

| S. pneumoniae-S. aureus | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 1.6 | 21 | 4.7 | 22 | 5.1 | <10−4 |

| K. pneumoniae-S. aureus | 6 | 1.3 | 4 | 3.2 | 21 | 4.7 | 23 | 5.3 | 3.10−4 |

| Bacteria-virus co-infections | |||||||||

| At least one virus-bacteria combinaison | 6 | 1.32 | 29 | 23.2 | 113 | 25.1 | 120 | 27.7 | <10−4 |

| S. pneumoniae-virus | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 1.6 | 37 | 8.2 | 37 | 8.5 | <10−4 |

| K. pneumoniae-virus | 1 | 0.2 | 8 | 6.4 | 34 | 7.5 | 41 | 9.5 | <10−4 |

| S. aureus-virus | 2 | 0.4 | 13 | 10.4 | 36 | 8.0 | 39 | 9.0 | <10−4 |

| H. influenzae-virus | 4 | 0.9 | 16 | 12.8 | 76 | 16.9 | 83 | 19.3 | <10−4 |

*p value: pre-Hajj versus per-Hajj and/or post-Hajj, McNemar’s Test.

To compare between pre- and per-Hajj specimens, 122 ill pilgrims have had paired samples. The acquisition proportion of HRV, S. aureus and H. influenzae was 39/122 (32.0%), 14/122 (11.5%) and 43/122 (35.3%) respectively (data not show).

Risk factors for respiratory symptoms

The Supplementary Table 1 and Table 3 show univariate and multivariate analyses results for factors associated with respiratory symptoms during the Hajj. Reporting of at least one respiratory symptom was twice as frequent and five times more frequent in rhinovirus carriers (adjusted relative risk (aRR): 1.98, 95%CI [1.03–3.78]) or H. influenzae-S. pneumoniae carriers, respectively (aRR: 4.75, 95%CI [1.17–19.35]) (Table 3). Coughing was twice as frequent in pilgrims suffering from chronic respiratory disease and among those carrying H. influenzae-K. pneumoniae together (aRR: 1.98, 95%CI [1.03–3.78]). Pilgrims who coughed were also more likely to use disposable handkerchiefs. Finally, ILI was more frequent in females, in pilgrims with chronic respiratory disease and among those carrying S. aureus or an association of virus and bacteria. In addition, pilgrims suffering ILI were more likely to use face mask. Influenza virus was not significantly associated with ILI. No significant association was observed between symptoms and vaccination against IPD. However, influenza vaccination was associated with a decrease in the prevalence of ILI (aRR: 0.69, 95%CI [0.52–0.92]).

Table 3.

Risk factor for respiratory symptoms during the Hajj (multivariate analysis).

| Variables | Cough | ILI† | At least one symptom | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aRR [95%CI] | p | aRR [95%CI] | p | aRR [95%CI] | p | |

| Male gender | — | 0.75 [0.58–0.96] | 0.02 | — | ||

| Chronic respiratory disease | 2.24 [1.04–4.82] | 0.04 | 1.47 [1.01–2.16] | 0.05 | — | |

| Prevention measures | ||||||

| Mask | — | 1.42 [1.10–1.82] | 0.007 | — | ||

| Disposable handkerchiefs | 1.71[1.17–2.50] | 0.006 | — | — | ||

| Vaccination against influenza | — | 0.69 [0.52–0.92] | 0.012 | — | ||

| Pathogens carriage during the Hajj | ||||||

| Human rhinovirus | — | — | 2.03 [1.14–3.61] | 0.02 | ||

| S. aureus | — | 1.34 [1.01–1.82] | 0.044 | — | ||

| H. influenzae – K. pneumoniae | 1.98 [1.03–3.78] | 0.04 | — | |||

| H. influenzae – S. pneumoniae | — | — | 4.75 [1.17–19.35] | 0.03 | ||

| At least one virus-bacteria combinaison | — | 1.33 [1.01–1.74] | 0.04 | — | ||

†ILI: influenza-like illness.

aRR: adjusted relative risk, CI: confidence interval, p: p value.

We found no significant association between persistence of respiratory symptoms at return and pathogen carriage with the exception of H. influenzae carriage in association with viral carriage (aRR: 1.65, 95%CI [1.07–2.53], p = 0.02).

Risk factors for respiratory pathogens acquisition among pilgrims

The Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 show the univariate risk factors analysis for respiratory virus and bacteria acquisition, respectively. In multivariate analysis (Table 4), male gender was associated with decreased acquisition of HCoV and K. pneumoniae (aRR: 0.76, 95%CI [0.58–0.99]). Older age (≥60 years) was associated with an increased acquisition of influenza viruses, HCoV and S. pneumoniae (aRR: 1.39, 95%CI [1.01–1.93], aRR: 1.53, 95%CI [1.16–2.01] and aRR: 1.28, 95%CI [1.01–1.63] respectively). Chronic respiratory disease was associated with increased acquisition of H. influenzae (aRR: 1.69, 95%CI [1.14–2.50]). No effect of vaccination against influenza was found. By contrast, vaccination against IPD was associated with a decrease in the acquisition of S. pneumoniae (aRR: 0.53, 95%CI [0.39–0.73]). Of note, IPD vaccination did not significantly influenced S. pneumoniae carriage at baseline (in pre-Hajj samples) (RR: 0.47, 95%CI [0.11–1.99], p = 0.29). Acquisition of HRV was higher among pilgrims who reported using facemasks (aRR = 1.30, 95%CI [1.03–1.65]). The use of disposable handkerchiefs has been associated with a decrease in the acquisition of S. aureus (aRR: 0.75, 95%CI [0.57–0.97]). Hand hygiene and the use of a disinfectant gel do not have a significant effect on the acquisition of pathogens.

Table 4.

Risk factor for acquisition of respiratory pathogens during the Hajj (multivariate analysis).

| Variables | Influenza viruses | Human rhinovirus | Human coronaviruses | S. aureus | S. pneumoniae | H. influenzae | K. pneumoniae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aRR [95%CI] p | aRR [95%CI] p | aRR [95%CI] p | aRR [95%CI] p | aRR [95%CI] p | aRR [95%CI] p | aRR [95%CI] p | |

| Socio-demographics characteristic | |||||||

| Male gender | 0.76 [0.58 – 0.99] 0.05 | 0.78 [0.62 – 0.98] 0.04 | |||||

| Age ≥60 years | 1.39 [1.01 – 1.93] 0.04 | 1.53 [1.16 – 2.01] 0.003 | 1.28 [1.01 – 1.63] 0.05 | ||||

| Chronic respiratory disease | 1.69 [1.14 – 2.50] 0.01 | ||||||

| Preventive measures | |||||||

| Vaccination against IPD | 0.53 [0.39 – 0.73] < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Mask | 1.30 [1.03 – 1.65] 0.03 | ||||||

| Handkerchief | 0.75 [0.57 – 0.97] 0.03 | ||||||

aRR: adjusted relative risk, CI: confidence interval, p: p value, IPD: invasive pneumococcal diseases.

Discussion

Our results confirm that respiratory infections were very common among French Hajj pilgrims, with more than 80% of them reporting at least one symptom during the 2014–2017 Hajj seasons. Our result is in line with the previous results obtained from cohort studies conducted among French pilgrims21 and from a large cohort study enrolling pilgrims from 13 different countries22. We also document the significant acquisition of almost all viral and bacterial pathogens included in our survey, following participation to the Hajj, as reported previously3,23.

We found that male gender was independently associated with a decreased risk for ILI and for the acquisition of coronaviruses and K. pneumoniae. We have no explanation for this unexpected observation. Older age (≥60 years) was associated with the acquisition of influenza viruses, HCoV and S. pneumoniae. Although older age was not correlated with the increase in the proportion of respiratory symptoms in our study, our results support the current French recommendations that indicate influenza vaccination for all pilgrims and IPD vaccination for pilgrims aged ≥60 years old (or with chronic conditions)24,25. Furthermore, we showed that influenza vaccination was significantly associated with a lower prevalence of ILI in our survey. Similarly, in a meta-analysis, Alfelali et al. have shown that, influenza vaccine decreases the prevalence of ILI26. We also demonstrate here that vaccination against IPD with a decrease in the acquisition of S. pneumoniae, but had no effect on respiratory symptoms. A protective effect of pneumococcal vaccination against S. pneumoniae post-Hajj carriage was observed in only one out of 5 studies so far9. However, all studies showing no effect of pneumococcal vaccination were conducted on small groups of pilgrims (ranging 55 to 107 individuals), while in the two studies showing a protective effect, the number of pilgrims was much higher (1178 and 468) which may indicate that small surveys lacked statistical power. Finally, as expected, patients suffering from chronic respiratory diseases were more likely to suffer from cough and ILI but also to acquire H. influenzae. Our results confirm the need for influenza and IPD vaccination among the identified pilgrim populations at risk of RTIs and acquisition of respiratory pathogens. Vaccination rates in our cohort were clearly sub-optimal: 26.7% of pilgrims were vaccinated against influenza and 30.5% against IPD among those with an indication.

With regard to non-pharmaceutical preventive measures, the use of masks, especially in crowded areas, frequent hand washing with water and soap or disinfectant, especially after coughing and sneezing, and the use of disposable handkerchiefs are recommended by the Saudi Ministry of Health to Hajj pilgrims27. In a meta-analysis including 13 surveys of Hajj pilgrims, significant protection of face masks was found against RITs, but the end points varied considerably12. We found that there was a higher prevalence of ILI and rhinovirus acquisition among pilgrims who reported wearing face masks. Similarly, a higher prevalence of cough was observed among pilgrims who reported using disposable handkerchiefs. It is likely that such results indicate the higher willingness of symptomatic pilgrims to wear a face mask and use disposable handkerchiefs, with the aim of avoiding spreading diseases. In addition, the use of disposable handkerchiefs appears to be correlated with a decrease in the acquisition of S. aureus carriage, which may reflect a better elimination of organisms by cleaning the nasopharynx. We found that increased hand hygiene was not associated with reduced respiratory pathogens acquisition or a lower prevalence of respiratory symptoms. In a recent review paper, it was shown that while hand hygiene using non-alcoholic products was generally well accepted by Hajj pilgrims, there was no conclusive evidence of its effectiveness, which is consistent with our results11.

Relationship between respiratory symptoms and carriage of respiratory pathogens at the Hajj are unclear. Because of the high frequency of respiratory symptoms, the distinction between infection and colonization is difficult to assess. Furthermore, asymptomatic carriage of potential pathogens is also observed among Hajj pilgrims28. Nevertheless, in the final model of multivariate analysis, the acquisition of S. aureus was associated with ILI and the acquisition of rhinovirus was associated with respiratory symptoms. Many studies showed that S. aureus and rhinovirus were among the predominant pathogens isolated from the Hajj pilgrims suffering RTIs9,11,12,21,23–32. Most cases of infections due to HRV are benign, self-limited cold-like illnesses. Nevertheless, HRV is also responsible for severe pneumonia in the elderly and immunocompromised patients, as well as exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma33. HRV spreads mostly via direct contact or contact with a fomite, with inoculation to the eye or nose from fingertips34. The human-to-human transmission of rhinovirus among pilgrims may have been favored by the crowded conditions at pilgrim accommodations or during performing the Hajj rites.

S. aureus is also often part of the human microbiome in the anterior nares35. However, persistent S. aureus nasal carriage is associated with secondary staphylococcal respiratory infection, predisposing to invasive disease, especially in the case of detection of IAV36–38. To date, few studies addressed virus-bacteria carriage in relation with RTIs at the Hajj4,28. In our study, overall carrying virus-bacteria was associated with ILI. Dual H. influenzae-K. pneumoniae carriage was associated with twice the risk of coughing and H. influenzae-S. pneumoniae carriage with 5 times the risk for respiratory symptoms. Further works aiming at better understanding the role of overall carrying virus and bacteria in the pathogenesis of the RTIs at the Hajj are needed.

Our study had some limitations. The study was conducted among French pilgrims only and cannot be generalized to all pilgrims. Observance with individual preventive measures was self-reported and frequency of changing face mask and exact quantification of hand hygiene practice were not assessed. qPCR used to detect respiratory pathogens does not distinguish between dead and living micro-organisms. S. pneumoniae serotypes were not investigated. Moraxella catarrhalis that was recently shown to be relatively frequently acquired by Hajj pilgrims39 was not included in our study. Finally, we did not to be any long-term follow-up to determine what infections might have had delayed presentation after return from the pilgrimage. Nevertheless, our study included a large samples size of pilgrims spanning four Hajj seasons giving it a stronger statistical power. A number of risk factors have been identified to recognize pilgrims at increased risk of RTIs and of acquisition of most common respiratory pathogens encountered in this setting. Also, the study confirmed the effectiveness of vaccination against influenza in reducing ILI symptoms and that of vaccination against IPD in reducing acquisition of S. pneumoniae. Given the limitations of the current study, the use of face mask and a reinforced hand hygiene should still be recommended for Hajj pilgrims until large-scale controlled studies are conducted to truly assess the effectiveness of these measures in the context of Hajj. The use of disposable handkerchief is, de facto, highly frequent among ill pilgrims and at least allows decreasing the acquisition of S. aureus.

Methods

Participants and study design

A convenience sample of pilgrims participating in the Hajj from 2014 to 2017 was surveyed. Potential adult participants were recruited at a private specialized travel agency from Marseille, France, organizing journeys to Mecca, Saudi Arabia and invited to participate in the study. They were included and followed-up by a medical bilingual (Arabic and French) doctor who traveled with the group. Upon inclusion before departing from France, the pilgrims were interviewed using a standardized pre-Hajj questionnaire that collected items about demographic characteristics (age, sex, place of birth), immunization status (vaccination against influenza and IPD) and medical history (chronic medical conditions, immunodeficiency, body mass index (BMI)). Pilgrims were considered to have been vaccinated immunized against influenza when they had been vaccinated within the last year, but before 10 days of the date of travel. Pilgrims were considered immune to IPD when they had been vaccinated with the 13-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (PCV-13) in the past 5 years13–20. Clinical events occurring during the travel (type of respiratory symptoms, date of onset, duration of symptoms, antibiotic treatment provided) and persistence of respiratory symptoms at return were collected by a medical doctor using a post-Hajj questionnaire at 2 days before the pilgrims’ return to France. The information on compliance with face masks use as well as hand washing, use of hand gel disinfectant and disposable handkerchiefs was documented. Ill pilgrims, who spontaneously consulted the accompanying medical doctor at the time of onset during the Hajj, underwent a complementary nasopharyngeal swab (per-Hajj specimens). ILI was defined as the presence of cough, sore throat and subjective fever40. Based on the WHO classification, underweight was define as a BMI below 18.5, normal with a BMI from 18.5 to less than 25, overweight with a BMI greater ≥25 and obesity with a BMI greater ≥3041.

The protocol was approved by the Aix-Marseille University institutional review board (July 23rd, 2013; reference no. 2013-A00961-44). The study was performed according to the good clinical practices recommended by the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. All participants provided an informed written consent.

Respiratory specimen

Nasopharyngeal swabs were obtained from each pilgrim, transferred to Sigma-Virocult® medium and stored at −80 °C until processing. Pre-Hajj and post-Hajj nasopharyngeal swabs were systematically collected at enrollment, prior traveling to Saudi Arabia and two days prior returning to France, respectively. In addition, nasopharyngeal swabs were collected at symptom onset when possible.

Respiratory specimens

DNA and RNA were extracted from the respiratory samples using the EZ1 Advanced XL (Qiagen, Hilden, German) with the Virus Mini Kit v2.0 (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Quantitative real-time PCRs were conducted using a C1000 Touch™ Thermal Cycle (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Negative control (PCR mix) and positive control (DNA from bacterial strain or RNA from viral strain) were included in each run. Positive results of bacteria or virus amplification were defined as those with a cycle threshold (CT) value ≤35.

Identification of respiratory virus

One-step duplex quantitative RT-PCR amplifications of HCoV/HPIV-R Gene Kit (REF: 71–045, Biomérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) was used to detect HCoV and human para-influenza viruses according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. One-step simplex real-time quantitative RT-PCR amplifications were performed using the Multiplex RNA Virus Master Kit (Roche Diagnostics, France) for HRV, IAV, influenza B and internal controls MS2 phage42.

Identification of respiratory bacteria

Real-time PCR amplifications were carried out using the LightCycler® 480 Probes Master kit (Roche diagnostics, France) according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. The SDD gene of H. influenzae, nucA gene of S. aureus, phoE gene of Klebsiella pneumoniae, lytA CDC gene of S. pneumoniae, were amplified with internal DNA extraction controls TISS, as previously described22.

The respiratory viruses and bacteria tested in this study were the most frequent microorganism detected among French pilgrims, according to previous studies28,29. All other pathogens (adenovirus, bocavirus, metapneumovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza viruses, Bordetella pertussis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis) with prevalence <1% were not included in this study.

The acquisition of respiratory bacteria and viruses was defined as negative before travel and positive during the Hajj and/or when returning to France.

Statistical analysis

STATA software version 11.1 (Copyright 2009 StataCorp LP, http://www.stata.com) was used for statistical analysis. Differences in the proportions were tested by Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests when appropriate. In order to evaluate the potential acquisition of respiratory pathogens in Saudi Arabia, we used the McNemar’s Test to compare their prevalence before leaving France and in Saudi Arabia (during and after the Hajj). Unadjusted associations between multiple factors and prevalence of respiratory pathogen acquisition and prevalence of respiratory symptom during the Hajj were examined by univariable analysis. The results were presented by percentages and risk ratio with 95% confidence interval (95%CI). Results with a p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Only the variables with a prevalence ≥5.0% were considered for statistical analysis. Variables with p values <0.2 in the univariable analysis were included in the multivariable analysis. Log-binomial regression was used to estimate factor’s adjusted risk ratios regarding respiratory symptoms and respiratory pathogens acquisition43.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire (IHU) Méditerranée Infection, the National Research Agency under the program ≪ Investissements d’avenir ≫, reference ANR-10-IAHU-03, the Région Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur and European funding FEDER PRIMI.

Author contributions

V.T.H., V.P.S. and P.G. contributed to experimental design, data analysis, statistics, interpretation and writing. V.T.H. and S.A.S. conducted the qPCR technique, K.B., M.M. and D.S. administered questionnaires, followed patients and collected samples, T.D.A.L., T.L.D. and L.N. provided technical assistance. S.Y., B.A., D.R. and P.P. contributed to critically reviewing the manuscript. P.G. coordinated the work.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-54370-0.

References

- 1.Gautret P, et al. Pilgrims from Marseille, France, to Mecca: demographics and vaccination status. J Travel Med. 2007;14:132–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Memish, et al. Hajj: infectious disease surveillance and control. Lancet. 2014;383:2073–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60381-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoang VT, Gautret P. Infectious Diseases and Mass Gatherings. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2018;20:44. doi: 10.1007/s11908-018-0650-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Tawfiq JA, Benkouiten S, Memish ZA. A systematic review of emerging respiratory viruses at the Hajj and possible coinfection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2018;23:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benkouiten S, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA, Albarrak A, Gautret P. Clinical respiratory infections and pneumonia during the Hajj pilgrimage: A systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2019;28:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gautret P, Benkouiten S, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Hajj-associated viral respiratory infections: A systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14:92–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Tawfiq JA, Zumla A, Memish ZA. Respiratory tract infections during the annual Hajj: potential risks and mitigation strategies. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:192–7. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835f1ae8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alfelali M, et al. Changes in the prevalence of influenza-like illness and influenza vaccine uptake among Hajj pilgrims: A 10-year retrospective analysis of data. Vaccine. 2015;33:2562–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edouard S, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA, Yezli S, Gautret P. Impact of the Hajj on pneumococcal carriage and the effect of various pneumococcal vaccines. Vaccine. 2018;36:7415–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benkouiten S, Brouqui P, Gautret P. Non-pharmaceutical interventions for the prevention of respiratory tract infections during Hajj pilgrimage. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2014;12:429–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alqahtani, A. S. et al. Hand hygiene compliance and effectiveness against respiratory infections among Hajj pilgrims: a systematic review. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 10.2174/1871526518666181001145041 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Barasheed O, et al. Uptake and effectiveness of facemask against respiratory infections at mass gatherings: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;47:105–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haut Conseil de la santé publique. Bull Epidemiol Hebdo. Recommandations sanitaires pour les voyageurs, http://opac.invs.sante.fr/doc_num.php?explnum_id=9478 (2014).

- 14.Direction Générale de la Santé. Ministère des Affaires sociales, de la Santé et des Droits des femmes. Paris. Calendrier des vaccinations et recommandations vaccinales 2014, https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Calendrier_vaccinal_ministere_sante_2014.pdf (2014).

- 15.Haut Conseil de la santé publique. Bull Epidemiol Hebdo. Recommandations sanitaires pour les voyageurs, http://invs.santepubliquefrance.fr/beh/2015/reco/pdf/2015_reco_1.pdf (2015).

- 16.Direction Générale de la Santé. Ministère des Affaires sociales, de la Santé et des Droits des femmes. Paris. Calendrier des vaccinations et recommandations vaccinales 2015, http://solidaritessante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Calendrier_vaccinal_2015.pdf (2015).

- 17.Haut Conseil de la santé publique. Bull Epidemiol Hebdo. Recommandations sanitaires pour les voyageurs http://opac.invs.sante.fr/doc_num.php?explnum_id=10383 (2016).

- 18.Direction Générale de la Santé. Ministère des Affaires sociales, de la Santé et des Droits des femmes. Paris. Calendrier des vaccinations et recommandations vaccinales 2016 https://www.mesvaccins.net/textes/Calendrier_vaccinal_2016.pdf (2016).

- 19.Haut Conseil de la santé publique. Bull Epidemiol Hebdo. Recommandations sanitaires pour les voyageurs http://opac.invs.sante.fr/doc_num.php?explnum_id=10785 (2017).

- 20.Direction Générale de la Santé. Ministère des Affaires sociales, de la Santé et des Droits des femmes. Paris. Calendrier des vaccinations et recommandations vaccinales 2017 https://www.mesvaccins.net/textes/calendrier_vaccinations_2017.pdf (2017).

- 21.Gautret P, Benkouiten S, Griffiths K, Sridhar S. The inevitable Hajj cough: Surveillance data in French pilgrims, 2012-2014. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2015;13:485–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Memish ZA, et al. Mass gathering and globalization of respiratory pathogens during the 2013 Hajj. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;6(571):e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Razavi SM, Mardani M, Salamati P. Infectious Diseases and Preventive Measures During Hajj Mass Gatherings: A Review of the Literature. Arch Clin Infect Dis. 2018;13:e62526. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haut Conseil de la santé publique. Bull Epidemiol Hebdo. Recommandations sanitaires pour les voyageurs https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/determinants-de-sante/voyage/documents/magazines-revues/bulletin-epidemiologique-hebdomadaire-25-mai-2018-n-hors-serie-recommandations-sanitaires-pour-les-voyageurs-2018 (2018).

- 25.Direction Générale de la Santé. Ministère des Affaires sociales, de la Santé et des Droits des femmes. Paris. Calendrier des vaccinations et recommandations vaccinales 2018, https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/calendrier_vaccinations_2018.pdf (2018).

- 26.Alfelali, M., Khandaker, G., Booy, R. & Rashid, H. Mismatching between circulating strains and vaccine strains of influenza: Effect on Hajj pilgrims from both hemispheres. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 12709–15 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health. Health Requirements and Recommendations for Travelers to Saudi Arabia for Hajj and Umrah – 2018/1439H, http://www.moh.gov.sa/en/hajj/pages/healthregulations.aspx (2018).

- 28.Benkouiten S, et al. Respiratory viruses and bacteria among pilgrims during the 2013 Hajj. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1821–7. doi: 10.3201/eid2011.140600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benkouiten S, et al. Comparison of nasal swabs with throat swabs for the detection of respiratory viruses by real-time reverse transcriptase PCR in adult Hajj pilgrims. J Infect. 2015;70:207–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atabani SF, et al. Active screening and surveillance in the United Kingdom for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in returning travellers and pilgrims from the Middle East: a prospective descriptive study for the period 2013-2015. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;47:10–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Abdallat MM, et al. Acute respiratory infections among returning Hajj pilgrims-Jordan, 2014. J Clin Virol. 2017;89:34–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marglani OA, et al. Acute rhinosinusitis during Hajj season 2014: Prevalence of bacterial infection and patterns of antimicrobial susceptibility. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14:583–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Royston Léna, Tapparel Caroline. Rhinoviruses and Respiratory Enteroviruses: Not as Simple as ABC. Viruses. 2016;8(1):16. doi: 10.3390/v8010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Musher DM. How contagious are common respiratory tract infections? N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1256–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wertheim HF, et al. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:751–62. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wertheim HF, et al. Risk and outcome of nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in nasal carriers versus non-carriers. Lancet. 2004;364:703–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16897-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corne P, Marchandin H, Jonquet O, Campos J, Bañuls AL. Molecular evidence that nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus plays a role in respiratory tract infections of critically ill patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3491–3. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3491-3493.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mulcahy, M. E. & McLoughlin, R. M. Staphylococcus aureus and Influenza A Virus: Partners in Coinfection. MBio., 10.1128/mBio.02068-16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Momenah AM. Moraxella catarrhalis as a Respiratory Tract Pathogen during Umrah and Hajj Seasons. Egyptian Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2018;27:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rashid H, et al. Influenza and the Hajj: defining influenza-like illness clinically. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:102–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.WHO. Body mass index – BMI http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi (2018).

- 42.Ninove N, et al. RNA and DNA bacteriophages as molecular diagnosis controls in clinical virology: a comprehensive study of more than 45,000 routine PCR tests. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:940–3. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.