Abstract

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is the most common elective orthopedic surgery performed in the United States. Following surgery patients experience significant lower extremity swelling that is related to poor satisfaction with surgery and is hypothesized to contribute to functional decline. However, in practice, precise and reliable methods for measuring lower extremity swelling do not exist. The purpose of this study was to provide reliability and precision parameters of an innovative approach, single frequency bioelectrical impedance assessment (SF-BIA), for measuring post-TKA lower extremity swelling. Swelling in 56 patients (64.3 ± 9.3 years; 29 males) was measured before and after TKA using SF-BIA and circumferential measures (CM). Reliability of the measures were calculated using Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC). Precision of the measures were provided using standard error of the measurement and minimal detectable change (MDC90). Change values between time points for SF-BIA and CM are provided. SF-BIA was found to have greater reliability following surgery compared to CM (ICC = 0.99 vs 0.68). SF-BIA was found to have a MDC90 = 2% following surgery, indicating improved ability to detect minute fluctuations in swelling compared to CM (MDC90 = 6%) following surgery. These results indicate that SF-BIA improves the precision and reliability of swelling measurement compared to CM.

Keywords: Bioelectrical Impedance Assessment, Precision, Psychometrics, Reliability, Swelling, Total Knee Arthroplasty

INTRODUCTION

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA), the most commonly performed elective orthopedic surgery in the United States (Kurtz et al, 2007), is regarded as a highly successful procedure for relieving pain in people with severe knee osteoarthritis (Choi and Ra, 2016; Tallon, Chard, and Dieppe, 2000). However, the procedure is highly invasive and the associated tissue damage causes a major inflammatory response (Arias, Aller, and Arias, 2009; Chovatiya and Medzhitov, 2014; Medzhitov, 2008). This tissue injury results in an effusion of blood, protein, immune cells, fluid, and other exudate into the extra cellular space (Gute, Ishida, Yarimizu, and Korthius, 1998). As the extracellular spaces of the lower extremity swell, a shift in the osmotic gradient causes intracellular swelling (Merrick, 2002; Muyskens et al, 2016). The result is a substantial amount of lower extremity swelling both between and within the cells.

Swelling of the lower extremity following TKA has been reported by patients to: negatively influence the perception of recovery (Noble, Conditt, Cook, and Mathis, 2006); is hypothesized to reduce quadriceps muscle function (Holm et al, 2010; Palmieri-Smith, Kreinbrink, Ashton-Miller, and Wojtys, 2007; Pua, 2015; Rice and McNair, 2010); contribute to declines in range of motion (ROM) (Ishida et al, 2011; Parvizi et al, 2014; Scranton, 2001); and is associated with higher pain (Chou et al, 2016). Despite evidence linking swelling to post-TKA impairments that contribute to functional limitations, this clinical target has been difficult to study due to limitations in the precision and reliability of measurement. However, evidence supporting the use of bioelectrical impedance spectroscopy (BIS) for the measurement of swelling in chronic lymphedema (Gerber, 1998; Hidding et al, 2016; Tiwari et al, 2003) and orthopedic conditions (Pichonnaz et al, 2013; Pua, 2015) has demonstrated its ability to quantify swelling.

Like BIS, single frequency bioelectrical impedance assessment (SF-BIA) can be used to accurately measure minute fluctuations in impedance. These fluctuations in impedance can be used to quantify increases and decreases in swelling across the entire lower extremity (Kyle et al, 2004a; Kyle et al, 2004b). However, SF-BIA may represent an affordable alternative to more expensive BIS units, but work must first be done to determine the reliability and precision of SF-BIA in lower extremity swelling measurement following TKA and compare these results to the more common method for measuring swelling, circumferential measurements (CM).

Performing CM only captures superficial changes in swelling, missing changes within deeper tissues and compartments (e.g. the knee joint capsule), meaning CM likely fail to detect small yet meaningful fluctuations that can be detected by BIS (Hidding et al, 2016). CM also fails to detect swelling known to occur across the entire leg following TKA (Nicholas, Taylor, Buckingham, and Ottonello, 1976), as it is typically only performed at one or two locations due to time restrictions (Hidding et al, 2016). On the other hand, BIS measures swelling throughout the entirety of the leg (Hidding et al, 2016).

To date, important metrics including standard error of the measurement, minimal detectable change, and expected interval change values have not been produced for SF-BIA. Furthermore, an assessment of how SF-BIA compares to CM will add context to the interpretation of SF-BIA measurement. Therefore, this study was designed to: 1) produce psychometric properties of SF-BIA and CM of swelling including the test-retest reliability, standard error of the measurement, and minimal detectable change (MDC90); and 2) examine how the psychometric properties of SF-BIA compare to those of CM. This evidence will provide essential information to clinicians and researchers as they interpret SF-BIA measurements of swelling post-TKA.

METHODS

Subjects

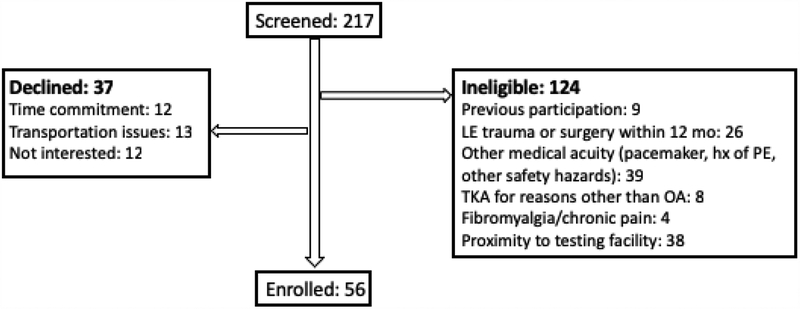

Data used in this analysis were collected from participants enrolled in a longitudinal, observational study. All participants were between 40–90 years of age, were scheduled to undergo primary, unilateral TKA, and had a primary diagnosis of osteoarthritis. Participant enrollment took place between December 2015 and April 2017. There were 224 participants screened and 56 were consented and enrolled (Figure 2). Exclusions included neurological conditions or unstable orthopedic conditions limiting participation, history of orthopedic surgery or trauma within one year of study enrollment, or diagnosis of a condition known to result in lower extremity edema (e.g. heart failure, lymph node resection, and primary lymphedema). All participants consented to and received study procedures approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (#15–1419).

Figure 2.

Consort diagram of those participants screened and enrolled in the study.

Study Design

Data used in this study were collected as part of a larger study examining swelling, quadriceps function, and patient functional performance before and after TKA. All enrolled participants were scheduled for surgery at the University of Colorado Hospital by one of three surgeons. Following surgery, all patients received standard of care rehabilitation in the hospital, including education on swelling management through cryotherapy and leg elevation. Upon discharge, patients were allowed to pursue therapy of their choice and no specific swelling interventions were provided. Pre-operative assessments were performed between 5 and 15 days prior to surgery. Post-operative assessments occurred at 7 discrete time points to allow for an accurate description of the trajectory of post-TKA swelling. For the purposes of this analysis, data from the pre-operative, 2 week, and 6 week assessments were used. These time points were chosen to assess responsiveness of the SF-BIA measure to changes in swelling, as it was important that we performed the assessments over a period that significant levels of increase and decrease were expected. Furthermore, the assessments performed at these three time points were performed in the laboratory with two assessors available to perform inter-rater reliability, all other intermediary assessments were performed by only one assessor. The six weeks following TKA is a window of time expected to have these changes.

Outcome Measures

SF-BIA was used to quantify lower extremity swelling at each assessment time point. Testing was performed using the RJL Systems Quantum® (Clinton Township, MI) bioelectrical impedance device, which delivers a 2.5 μA alternating current at a frequency of 50 kHz. The impedance to this current, is displayed in Ohms (Ω) and is recorded at a precision of 1 Ω. Using SF-BIA with a frequency of 50 kHz meant that the level of impedance detected reflected composition of the tissue and the presence of both intra and extracellular fluid. This differs from the use of BIS, which allows for measurements at much lower frequencies (nearing 0 Hz, i.e. direct current). At lower frequencies, bioelectrical impedance values are believed to represent only extracellular fluid levels (Altay et al, 2012; Ellis, Shypailo, and Wong, 1999; Ertürk et al, 2015; Kyle et al, 2004a; Pichonnaz et al, 2015). However, BIS devices are highly expensive and the authors believe that both intra- and extracellular fluid fluctuations represent important values when assessing whole limb swelling following TKA and therefore, SF-BIA provides an acceptable alternative to BIS.

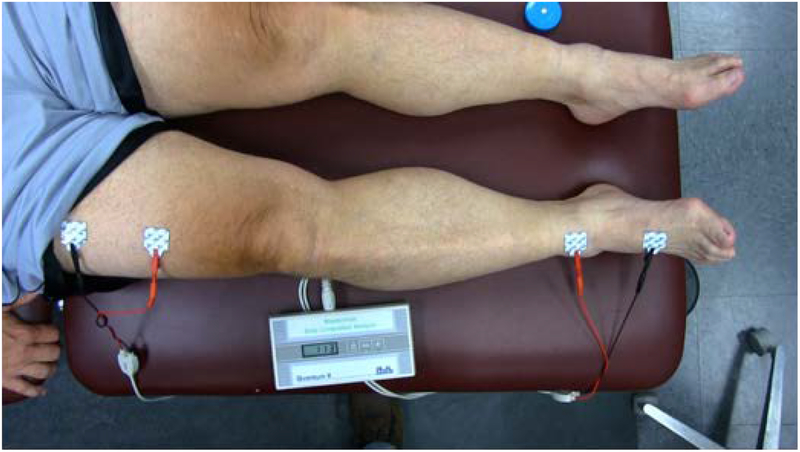

Testing was performed using a four-wire measurement method, consisting of two current-injecting electrodes represented by the red leads in Figure 1 and two measuring electrodes (black leads) that detect the voltage drop across the limb. No universally accepted method for the placement of the electrodes exists (Hidding et al, 2016), thus, a method was chosen that would focus specifically on swelling changes in the lower extremity, not influenced by visceral fluid changes. Before beginning each swelling assessment, participants were positioned in supine for 10 minutes to standardize the potential shift of fluid from the lower extremities. Four surface electrodes were then systematically placed on the lower extremity along the second ray on the dorsal surface of the foot separated by 10 cm and at 10 and 20 cm proximal to the superior pole of the patella on the anterior surface of the thigh (Figure 1). Lower levels of impedance represent the increased fluid content present with greater levels of swelling. Measuring the impedance of both the involved and uninvolved limb allows for calculation of a percent difference between limbs using the formula: 1-(Ω-involved limb: Ω-uninvolved limb)*100. The ratio of involved to uninvolved was used to normalize body composition, fluid shifts, and hydration status within each participant, increasing the likelihood that changes in impedance could be contributed to limb swelling.

Figure 1.

Demonstrating the set up for Single Frequency Bioelectrical Impedance Assessment (SF-BIA) of lower extremity swelling.

CM of swelling were taken at the superior pole of the patella (SPP) and 10 cm proximal to the SPP (10cmSPP), around the thigh, using a standard weighted retractable, medical tape measure. These locations were chosen based on past literature examining swelling using CM in various populations (Soderberg, Ballantyne, and Kestel, 1996). Measures were collected on the involved and uninvolved limb and recorded to the 10th of a cm (mm). Values were presented as a percent difference between the limbs calculated in the same way as SF-BIA.

Analysis

An a priori power analysis was not performed for this study, as a sample of convenience was used from a larger longitudinal study. Descriptive statistics including mean, SD, median, and quartiles were applied to summarize the patient population, including, age, height, weight, BMI. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC 2,1) and 95% CI were calculated to describe test-retest reliability of SF-BIA and CM of swelling (Shrout and Fleiss, 1979). Standard error of the measurement (SEM), calculated using SEM= SD *√(1-r), where r is the ICC, and the associated 95% CI were used to quantify the measurement error in the same units as the baseline measurement (Stratford and Goldsmith, 1997). The error associated with the measured value was calculated at a 90% CI by multiplying the point estimate for the SEM by the z-value associated with the 90% CI. The result of this error calculation was used to calculate the MDC90%, by using the following formula: MDC90= SEM* 1.65 * √2. A change greater than MDC90 is often interpreted as a true change in the measure (Beaton, Bombardier, Katz, and Wright, 2001; Kennedy et al, 2005). Change scores from baseline to 2 weeks and 2 weeks to 6 weeks were calculated for SF-BIA and both CM. Standardized response means were calculated from these changes scores using the formula: mean change/SD of the change.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the participants including mean age, BMI, height, weight, sex frequency, baseline swelling, baseline quadriceps strength, and comorbidity information are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information for participants included in the study (N=56)

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or N (%) | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 64.3 (9.3) | 65 (57, 71.5) |

| Male | 29 (52%) | - |

| Height (cm) | 171.9 (11.0) | 172.7 (162.6, 180.3) |

| Weight (kg) | 94.4 (21.3) | 91.3 (77.8, 107.6) |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 31.8 (5.5) | 30.9 (26.9, 37.7) |

| Pre-TKA SF-BIA swelling | 1.7 (6.8) | |

| Pre-TKA Strength (Nm) | ||

| Involved | 105.7 (55.8) | |

| Uninvolved | 125.2 (54.3) | |

| Comorbidity (Frequency %) | ||

| HBP | 29/56 (52%) | |

| Diabetes | 7/56 (13%) | |

| Cancer | 4/56 (7%) |

Table 2 provides the results of the reliability analysis (ICC) and estimates of the SEM and MDC90. SF-BIA was found to be highly reliable with ICC values higher than 0.8 before and after surgery, while CM were much lower. The MDC90 estimates were lower at all time points for SF-BIA than for CM at the SPP and 10 cm proximal (Table 2). It should be noted that ICC and MDC90 values for CM should be interpreted with caution due to small sample sizes.

Table 2.

Reliability, standard error of the measurement (SEM), and minimal level of detectable change (MDC90) for SF-BIA, SPP CM, and 10cmSPP CM measures of swelling. Pre-op values were taken prior to surgery and follow-up was performed at either the two or six-week follow-up visit.

| Variable | Time | N | ICC (95% CI) | SEM (95% CI) | MDC90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-BIA (Ratio) | Pre-op | 12 | 0.82 (0.51, 0.94) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03) | 0.04 |

| Follow-up | 11 | 0.99 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01) | 0.02 | |

| Circumference SPP (Ratio) | Pre-op | 6 | 0.19 (−0.76, 0.83) | 0.03 (0.02, 0.07) | 0.07 |

| Follow-up | 11 | 0.69 (0.21, 0.90) | 0.03 (0.02, 0.05) | 0.06 | |

| Circumference 10cmSPP (Ratio) | Pre-op | 6 | 0.30 (−0.44, 0.85) | 0.02 (0.02, 0.06) | 0.05 |

| Follow-up | 11 | −0.10 (−0.67, 0.51) | 0.08 (0.05, 0.14) | 0.18 |

Table 3 presents the mean and median scores for each measure of swelling at all three time points. Table 4 provides the change scores and standardized response means for each measure over the two intervals. The information presented in table 4 demonstrates that when measured by tape measure or SF-BIA, patients experience a measurable increase in swelling from baseline to 2-weeks post-TKA, followed by a decrease or return toward baseline from 2-weeks to 6-weeks post-TKA.

Table 3.

Mean (SD) and Median (IQR) for SF-BIA, SPP CM, and 10cmSPP CM of swelling. (*N=45)

| Measure | Pre-op (N=56) | 2-week (N=50) | 6-week (N=46) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |

| SF-BIA (Ratio) | 0.99 (0.08) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.02) | 0.72 (0.09) | 0.73 (0.66, 0.79) | 0.79 (0.08) | 0.80 (0.74, 0.84) |

| Circumference SPP (Ratio) | 1.02 (0.08) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) | 1.12 (0.07) | 1.13 (1.09, 1.15) | 1.06* (0.06) | 1.06* (1.04, 1.09) |

| Circumference 10cmSPP (Ratio) | 0.99 (0.04) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 1.03 (0.07) | 1.03 (0.99, 1.07) | 1.01* (0.03) | 1.02*(0.99, 1.03) |

Table 4.

Mean (SD) change scores and standardized response means (SRM) for SF-BIA, SPP CM, and 10cmSPP CM of swelling over interval 1 and 2. Change was calculated as 2 week minus pre-TKA (interval 1) and 6 week minus 2 week (interval 2).

| Measure | Preop to 2 Week | 2 week to 6 Week | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean Change (SD) | SRM | N | Mean Change (SD) | SRM | |

| SF-BIA (Ratio) | 50 | −0.26 (0.09) | −2.86 | 46 | 0.06 (0.07) | 0.92 |

| Circumference SPP (Ratio) | 50 | 0.10 (0.07) | 1.50 | 45 | −0.055 (0.06) | −0.97 |

| Circumference 10cm SPP (Ratio) | 50 | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.16 | 45 | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.54 |

Negative values indicate increase in swelling when measured using SF-BIA, while negative values for CM indicate decreases in swelling.

DISCUSSION

This study has characterized the psychometric parameters of SF-BIA, an innovative method of measuring lower extremity swelling, and compared it to a more commonly used approach of CM. As we hypothesized, SF-BIA was found to be a precise and reliable measurement of swelling and performed better than CM in capturing post-TKA lower extremity swelling.

To validate BIS as a useful tool for measuring post-TKA swelling, Pichonnaz et al. (2015) showed that BIS had inter-rater reliability as high as 0.98 and intra-rater reliability as high as 0.99. They also found that BIS significantly correlated with volumetric (Spearman = 0.73) and CM (Spearman = 0.75) of swelling. Unfortunately, the interpretation of these findings in clinical practice and clinical research require an understanding of the sensitivity to change and error associated with the measure. Therefore, we have expanded upon the findings from Pichonnaz et al. (2015) and produced psychometric properties we feel are critical to the implementation of the more affordable SF-BIA for the measurement of post-TKA lower extremity swelling.

The high level of reliability in combination with small levels of error in the measurement (SEM), demonstrates the ability of SF-BIA to detect relatively small amounts of change in swelling. MDC90 is an important metric as it provides information regarding what is considered a “true” change. Because the SEM is calculated from the standard deviation of the measure and the test-retest reliability, the MDC90 reflects the reliability and error of the measure. Using this information, clinicians are able to make informed decisions on the effectiveness of an intervention. For example, when a patient attends physiotherapy two weeks following TKA and receives an intervention to reduce swelling, pre- and post- treatment measurements are likely taken to determine the effectiveness of the intervention. If using SF-BIA, the clinician could consider a percent reduction in swelling greater than or equal to 2% a true detectable change in swelling. Within session MDC90 values presented here are critical to clinical decision-making, but data demonstrating how swelling is expected to change over time is also necessary.

Mean and median values at the baseline assessment demonstrate the presence of negligible amounts of swelling. At two and six weeks following surgery, large increases in swelling from baseline are observed. The observed mean change is indicative of the expected trajectory of swelling following TKA characterized by a rapid increase in swelling from pre-TKA through two weeks post-TKA and the slower reduction of swelling from two weeks to six weeks post-TKA. This is a period when patients are likely to be seen in rehabilitation and accurately measuring and monitoring swelling is critical. In future work, aimed at producing a clinical reference chart for the trajectory of post-TKA swelling, the mean (SD), median (IQR), and MDC90 data will be critical for interpreting an individual patient’s trajectory in relation to the reference chart.

When comparing the findings from SF-BIA to that of CM, interesting observations were made. Specifically, the differences in reliability and MDC90 of the measures. ICC values for CM were wide ranging and less useful than those from SF-BIA, due to the presence of a confidence interval that included negative values. This is a result of greater within-subject variability than between-subject variability and demonstrates the challenges in reliably performing CM. Interestingly, despite the differences in reliability and MDC90, SF-BIA and the CM identified the same trends in swelling fluctuation. Both measures detected minimal swelling pre-TKA, the highest levels at the 2-week time point, and slightly lower levels at 6 weeks. However, the magnitude of swelling change detected was different. The similarity in trend supports the idea that the same construct (i.e. lower extremity swelling) is being collected by both SF-BIA and CM, while the much larger magnitude (% swelling) found with SF-BIA supports the hypothesis that it is more sensitive to changes throughout the limb. Previous studies have similarly shown larger amounts of swelling detected with BIS compared to CM (Cornish et al, 2002; King, Clamp, Hutchinson, and Moran, 2007; Pichonnaz et al, 2016). However, it is worth noting that methods using repeated CM, such as the truncated cone, may have produced values more similar to those seen with SF-BIA, but the time and mathematical restraints of this method reduce its clinical feasibility (Sitzia, 1995).

This study has limitations. First, this study was conducted using data from a larger ongoing trial and, therefore, no power analysis was conducted for the specific outcomes tested in this trial. Secondly, the reliability testing done in this study was limited to a much smaller sample than the total number of participants tested. Only one tester was available during a large proportion of testing, preventing the use of all patient assessments and ultimately limiting the interpretability of the ICC, MDC90, and SEM values. Third, this study was only designed to examine swelling over the first six weeks following TKA, as this period was hypothesized to be the most critical window for swelling change and likely to avoid significant influence of muscle atrophy. At six weeks post-TKA, quadriceps and hamstring atrophy is typically minimal, but should still be noted as a possible confounder to CM (Mizner et al, 2005). Fourth, this study only examined the comparison of SF-BIA to CM. This study did not look at the use of other measures including: water submersion (Pasley and O’Connor, 2008); MRI (Lu, Xu, and Liu, 2010); or diagnostic ultrasound (Mandl et al, 2012). These measures are less commonly used clinically due to cost (i.e. MRI) and may be contraindicated early after surgery (i.e. water submersion); future work should examine how SF-BIA assessment compares to other methods. Lastly, this manuscript examined the use of SF-BIA and not BIS. BIS is potentially more accurate, but is much more expensive and time consuming to perform.

CONCLUSIONS

Increasing prevalence of TKA procedures requires work be done to improve recovery for patients and to streamline rehabilitation practices. Swelling of the lower extremity often occurs at a large magnitude following TKA, management of this swelling can assist in patient recovery and influence other important outcomes. However, methods for measurement that are clinically feasible, accurate, and reliable are not commonly used. This study found that SF-BIA is reliable and sensitive to minute fluctuations in swelling. Thus, it is able to provide accurate assessments of swelling and track changes in lower extremity swelling following TKA. It improves on the more commonly performed method of CM through greater reliability, improved sensitivity, and assessment of swelling across the entire lower extremity, including deeper tissues. Psychometric properties presented here will allow the use of SF-BIA in other investigations of lower extremity swelling. They will also provide clinicians with an understanding of how SF-BIA data can be interpreted for an individual patient’s swelling in respect to an anticipated recovery.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Altay MA, Ertürk C, Sert C, Oncel F, Işikan UE 2012. Bioelectrical impedance analysis of basal metabolic rate and body composition of patients with femoral neck fractures versus controls. Eklem Hastalik Cerrahisi 23: 77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias JI, Aller MA, Arias J 2009. Surgical inflammation: A pathophysiological rainbow. Journal of Translational Medicine 7: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Katz JN, Wright JG 2001. A taxonomy for responsiveness. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 54: 1204–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YJ, Ra HJ 2016. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surgery and Related Research 28: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, Rosenberg JM, Bickler S, Brennan T, Carter T, Cassidy CL, Chittenden EH, Degenhardt E 2016. Management of postoperative pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, executive commi. Journal of Pain 17: 131–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chovatiya R, Medzhitov R 2014. Stress, inflammation, and defense of homeostasis. Molecular Cell 54: 281–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish BH, Thomas BJ, Ward LC, Hirst C, Bunce IH 2002. A new technique for the quantification of peripheral edema with application in both unilateral and bilateral cases. Angiology 53: 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis KJ, Shypailo RJ, Wong WW 1999. Measurement of body water by multifrequency bioelectrical impedance spectroscopy in a multiethnic pediatric population. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 70: 847–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertürk C, Altay MA, Sert C, Levent A, Yaptı M, Yüce K 2015. The body composition of patients with knee osteoarthritis: Relationship with clinical parameters and radiographic severity. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 27: 673–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber LH 1998. A review of measures of lymphedema. Cancer 83: 2803–2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gute DC, Ishida T, Yarimizu K, Korthius RJ 1998. Inflammatory responses to ischemia, and reperfusion in skeletal muscle. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 179: 169–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidding JT, Viehoff PB, Beurskens CH, van Laarhoven HW, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW, van der Wees PJ 2016. Measurement properties of instruments for measuring of lymphedema: Systematic review. Physical Therapy 96: 1965–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm B, Kristensen MT, Bencke J, Husted H, Kehlet H, Bandholm T 2010. Loss of knee-extension strength is related to knee swelling after total knee arthroplasty. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 91: 1770–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida K, Tsumura N, Kitagawa A, Hamamura S, Fukuda K, Dogaki Y, Kubo S, Matsumoto T, Matsushita T, Chin T 2011. Intra-articular injection of tranexamic acid reduces not only blood loss but also knee joint swelling after total knee arthroplasty. International Orthopaedics 35: 1639–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DM, Stratford PW, Wessel J, Gollish JD, Penney D 2005. Assessing stability and change of four performance measures: A longitudinal study evaluating outcome following total hip and knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 6: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RJ, Clamp JA, Hutchinson JW, Moran CG 2007. Bioelectrical impedance: A new method for measuring post-traumatic swelling. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 21: 462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M 2007. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Am) 89: 780–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Deurenberg P, Elia M, Gomez JM, Heitmann BL, Kent-Smith L, Melchior JC, Pirlich M, Scharfetter H, Schols A; ESPEN 2004a. Bioelectrical impedance analysis--part I: Review of principles and methods. Clinical Nutrition 23: 1226–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Deurenberg P, Elia M, Gomez JM, Heitmann B Lilienthal, Kent-Smith L, Melchior JC, Pirlich M, Scharfetter H, Schols A; ESPEN 2004b. Bioelectrical impedance analysis-part II: Utilization in clinical practice. Clinical Nutrition 23: 1430–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Xu J, Liu N 2010. Chronic lower extremity lymphedema: A comparative study of high-resolution interstitial MR lymphangiography and heavily T2-weighted MRI. European Journal of Radiology 73: 365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandl P, Brossard M, Aegerter P, Backhaus M, Bruyn GA, Chary-Valckenaere I, Iagnocco A, Filippucci E, Freeston J, Gandjbakhch F, Jousse-Joulin S, Moller I, Naredo E, et al. 2012. Ultrasound evaluation of fluid in knee recesses at varying degrees of flexion. Arthritis Care and Research 64: 773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R 2008. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 454: 428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick MA 2002. Secondary injury after musculoskeletal trauma: A review and update. Journal of Athletic Training 37: 209–217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizner RL, Petterson SC, Stevens JE, Vandenborne K, Snyder-Mackler L 2005. Early quadriceps strength loss after total knee arthroplasty: The contributions of muscle atrophy and failure of voluntary muscle activation. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Am) 87: 1047–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muyskens JB, Hocker AD, Turnbull DW, Shah SN, Lantz BA, Jewett BA, Dreyer HC 2016. Transcriptional profiling and muscle cross-section analysis reveal signs of ischemia reperfusion injury following total knee arthroplasty with tourniquet. Physiological Reports 4: e12671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas JJ, Taylor FH, Buckingham RB, Ottonello D 1976. Measurement of circumference of the knee with ordinary tape measure. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 35: 282–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble PC, Conditt MA, Cook KF, Mathis KB 2006. The John Insall award: Patient expectations affect satisfaction with total knee arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 452: 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri-Smith RM, Kreinbrink J, Ashton-Miller JA, Wojtys EM 2007. Quadriceps inhibition induced by an experimental knee joint effusion affects knee joint mechanics during a single-legged drop landing. American Journal of Sports Medicine 35: 1269–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi J, Nunley RM, Berend KR, Lombardi AV, Ruh EL, Clohisy JC, Hamilton WG, Della Valle CJ, Barrack RL 2014. High level of residual symptoms in young patients after total knee arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 472: 133–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasley JD, O’Connor PJ 2008. High day-to-day reliability in lower leg volume measured by water displacement. European Journal of Applied Physiology 103: 393–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichonnaz C, Bassin JP, Currat D, Martin E, Jolles BM 2013. Bioimpedance for oedema evaluation after total knee arthroplasty. Physiotherapy Research International 18: 140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichonnaz C, Bassin JP, Lécureux E, Christe G, Currat D, Aminian K, Jolles BM 2016. Effect of manual lymphatic drainage after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 97: 674–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichonnaz C, Bassin JP, Lécureux E, Currat D, Jolles BM 2015. Bioimpedance spectroscopy for swelling evaluation following total knee arthroplasty: A validation study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 16: 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pua YH 2015. The time course of knee swelling post total knee arthroplasty and Its associations with quadriceps strength and gait speed. Journal of Arthroplasty 30: 1215–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice DA, McNair PJ 2010. Quadriceps arthrogenic muscle inhibition: Neural mechanisms and treatment perspectives. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 40: 250–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scranton PE 2001. Management of knee pain and stiffness after total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty 16: 428435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL 1979. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin 86: 420428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitzia J 1995. Volume measurement in lymphoedema treatment: Examination of formula. European Journal of Cancer Care 4: 11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderberg GL, Ballantyne BT, Kestel LL 1996. Reliability of lower extremity girth measurements after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Physiotherapy Research International 1: 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratford PW, Goldsmith CH 1997. Use of the standard error as a reliability index of interest: An applied example using elbow flexor strength data. Physical Therapy 77: 745–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallon D, Chard J, Dieppe P 2000. Exploring the priorities of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Care and Research 13: 312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari A, Cheng KS, Button M, Myint F, Hamilton G 2003. Differential diagnosis, investigation, and current treatment of lower limb lymphedema. Archives of Surgery 138: 152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]