Abstract

Objective.

A diversity of United States health professional disciplines provide services for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We conducted a systematic review examining the availability, distribution and competencies of the U.S. workforce for autism-related child healthcare services, and assess studies’ strength of evidence.

Method.

We searched PubMed, PsychINFO, Embase and Google Scholar from 2008–2018 for relevant US-based studies. Two investigators independently screened and evaluated studies against a set of pre-specified inclusion criteria and evaluated strength of evidence (SOE) using a framework designed to integrate a mixed-methods research.

Results.

Of 754 records identified, 33 studies—24 quantitative, 6 qualitative and 3 mixed-methods—were included. Strength of evidence associated was low-to-moderate, with only 8 studies (24%) satisfying criteria for strong SOE. Geographies and provider cadres varied considerably: The most common specialties studied were: pediatricians (n=13), occupational therapists (n=12), speech therapists (n=11), physical therapists (n=10), and child psychiatrists (n=8). Topical areas included provider availability by service area and care delivery model, qualitative assessments of provider availability and competency, the role of insurance mandates in increasing access to providers, and disparities in access. Across provider categories, we found workforce availability for autism-related services was limited—in terms of overall numbers, time available and knowledgeability. Greatest unmet need was observed among minorities and in rural settings. Most studies were short-term, limited in scope, and used convenience samples.

Conclusion.

There is limited evidence to characterize availability and distribution of the U.S. workforce for autism-related child healthcare services. Existing evidence to-date indicates significantly restricted availability.

Keywords: autism, autism spectrum disorder, healthcare access, healthcare availability, health disparities

INTRODUCTION

In 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released its most recent estimate on the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the United States: 1 in 59 children, equating to 1.3 million individuals under age 18.1 This estimate was up from the CDC’s 2008 estimate (1 in 88), which itself was an upward revision. Best practices for clinical care have emphasized a team-based approach for addressing the diverse clinical needs of children with ASD.2,3 Specific clinical services include medical and behavioral healthcare provided by pediatricians, child psychiatrists and psychologists;4 training on social cognitive skills through applied behavioral analysis (ABA) and occupational therapy;5,6 instruction on language and communication skills through speech therapy;7 and school-based supports including school social workers and counselors to navigate the educational environment.8

Taken together, the increasing recognition and complexity of healthcare needs associated with ASD underscore the urgency for a diverse health workforce to support care for children with this disorder. Yet, recent studies have found substantial unmet needs in this population,9,10 despite an increase in Medicaid waivers,11 state insurance mandates and other initiatives intended to improve access for autism-related care.12 Ongoing barriers include a continuing shortage of specific provider groups, such as child psychiatrists,9,13 and a pediatric workforce that is unevenly distributed throughout the U.S.14—reflected in large disparities in service utilization among minority communities.15

To date, there remains a paucity of literature that synthesizes findings on the scope and scale of the U.S. health workforce to provide services for children with ASD. This study aims to fill this gap through a systematic review on the availability and distribution of the health workforce for supporting autism-related care for children, extended across provider groups and geographic regions of the United States. We also include studies reporting on provider competencies, or lack thereof, as indicative of unavailability of services. Specifically, we synthesize peer-reviewed publications on the topic over the past ten years (2008–2018), focusing on nine provider types commonly involved in providing care to children with ASD: child psychiatrists, pediatricians and primary care providers (PCPs), child psychologists, social workers, behavioral analysis therapists, speech therapists, occupational therapists, physical therapists and mental health counselors.16 We assess strength of evidence among the identified publications, and discuss directions for future research.

METHOD

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We conducted a systematic review of academic literature, in accordance with PRISMA guidelines,17 targeting peer-reviewed publications. Inclusion criteria were as follows:

Topically focused on availability and/or distribution of health workforce, including health workforce ability and competency to provide autism-related health services

Included one or more of the following nine health workforce provider categories: child psychiatrists, child psychologists pediatricians, child social workers, occupational therapists, speech therapists, physical therapists, applied behavioral analysis therapists, and mental health counselors.

Patient population of interest defined as children ages 0–18 with autism spectrum disorder residing in the United States.18

Publication date between August 2008 and July 2018, along with a study period that includes data from 2008 or more recent.

We focused on service availability for children diagnosed with ASD, and excluded studies focused solely on availability of screening and diagnostic services for children with potential ASD. We also excluded literature reviews and commentaries. Following inclusion criteria, we implemented a Boolean search procedure based on key words under four domains: (1) workforce terminology, (2) provider classifications, (3) topical content of interest, and (4) autism-related terminology to identify the target population (see Table 1). Studies needed to include at least one term from Category 3 and one term from Category 4 in Table 1, as well as one term from either Category 1 or 2. This framework was intended to be as flexible as possible in terms of individual search terms. For example, the term “social worker” allowed us to capture a range of terms that may have been utilized by authors, such as “child social worker”, “clinical social worker” and “licensed social worker.”

TABLE 1.

Search Term Categories

| Category 1 | Category 2 | Category 3 | Category 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workforce | Provider groups | Topical area of study | Patient population |

| Provider* | Psychologist* | Distribution | Autism* |

| Personnel | Social worker* | Allocation | Autism spectrum disorder* |

| Labor force | Occupational therapist* | Access | ASD* |

| Work force | Behavioral analysis* | Availability | Pervasive developmental disorder |

| Workforce | Pediatrician* | PDD* | |

| Worker* | Mental health counselor* | Asperger* | |

| Physician*; PCP* | Williams Syndrome | ||

| Speech therap* | |||

| Physical therap* | |||

| BCBA* |

Note: Asterisk (*) denotes truncation search terms: all terms that begin with a given string of text. For example, “Asperger*” could return “Asperger’s”, “Asperger”, “Asperger Syndrome”, etc. ASD = autism spectrum disorder; BCBA = board certified behavioral analyst; PCP = primary care providers; PDD = pervasive developmental disorder.

To identify relevant literature, we searched PubMed, PsychInfo, Embase and Google Scholar. Google Scholar was limited to the first 100 returns for each search entry. In addition, we searched trial registration websites, including ClinicalTrials.gov, the Cochrane Central Register, and Scopus. We also examined bibliographies of highly-cited articles identified in this process.

We considered all published, peer-reviewed articles written in English. After identification of articles based on the above search procedures, we inspected titles, abstracts, and report summaries to determine whether the source addressed topical content consistent with study inclusion criteria. Returns were screened independently by two research team members. In the event that a discrepancy arose regarding inclusion criteria, the two members met together in person to deliberate and (when necessary) approached remaining members of the research team to render a verdict.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Following screening, we abstracted information from full-length texts, classifying whether the inclusion criteria were met. For each article that met the inclusion criteria, we abstracted author(s); journal; year; title; provider cadre; geographic scope; patient diagnostic classification; patient age range; topical area examined; key findings. Where available, we documented descriptive measures, such as percentages and means, as well as odds ratios and p-values. Using this information, research team members conceptually grouped articles into thematic categories based on emergent patterns in the data. These were then used as a framework by which to present results.

Assessment of Study Strength of Evidence

To evaluate strength of evidence (SOE), we applied Pluye and colleagues’ (2009)19 scoring system designed to appraise blended research: i.e. primary studies that variously employ quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods approaches. The widely utilized framework provides for direct comparability across all included studies by quantifying the presence of a set of SOE criteria specific to study type, including risk of bias, and then dividing this by the total number of criteria applicable. For qualitative studies, this includes criteria such as utilization of an appropriate qualitative approach and discussion of researchers’ reflexivity (i.e. the interpretive nature of the researchers’ work), while for quantitative studies this includes criteria such as justification of measures and control for confounding variables.

Two research team members independently scored studies based on presence/absence SOE criteria, and then reviewed ratings to arrive at consensus. When consensus was not achieved, the study was presented to the full research team for evaluation. Studies were classified into low (*), medium (**), and strong (***) SOE based on whether they met 0–33% of SOE criteria, 34–66% of SOE criteria, or 67–100% of SOE criteria, respectively. By way of example, if two of six SOE criteria were satisfied for a quantitative study, the manuscript would be scored 33% (2/6=33%) and classified as low SOE based on this schema. A full overview of SOE content is provided in the source methodology of Pluye and colleagues’ 2009 manuscript.19

RESULTS

Study Inclusion

After the search procedures, we reviewed 867 records: 861 from database searches, and an additional six from bibliographic reviews. There was a high degree of inter-rater reliability (93%) between screeners regarding inclusion of articles for full-text review, and all discrepancies were reconciled.

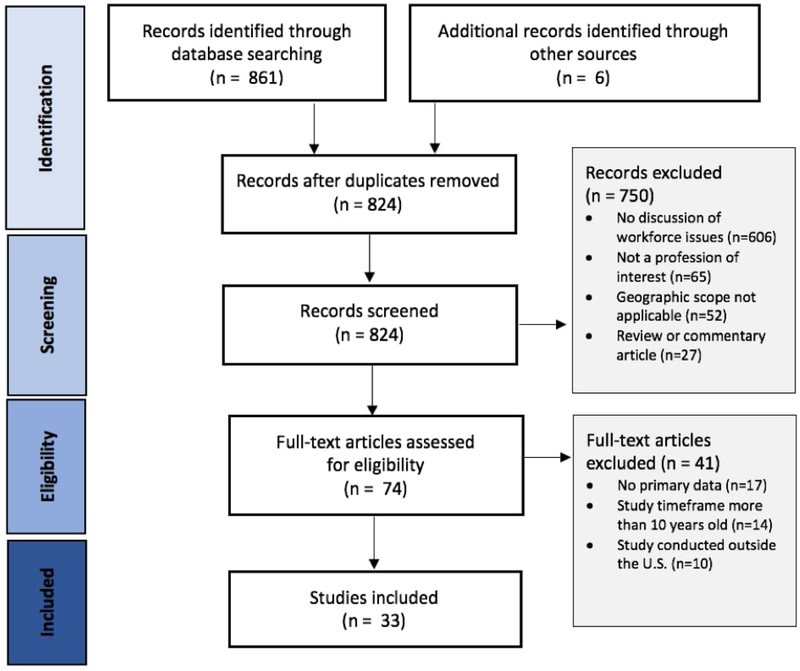

Following screening, 74 studies were identified for full-text inspection of eligibility. We excluded 750 studies using a stepwise assessment to eliminate studies in the following order: (i) studies that didn’t discuss distribution or availability of the human workforce for autism-related care (81%), (ii) studies that didn’t focus on a profession of interest as defined above (9%), (iii) studies conducted outside the United States (7%), and (iv) the article did not include primary data (4%). See Flow Diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram

Of the 74 studies that received full-text inspection, 33 met eligibility. Studies were most often excluded at this stage either because the study period examined was more than 10 years old (n=14; 34%), the study was conducted outside the United States (n=10; 24%), or the study was a review or perspective piece that did not present new data (n=17; 41%).

Characteristics of Included Studies

Fourteen of the 33 studies had a geographic scope that extended throughout the United States, three (9%) examined multi-state regions, seven (21%) examined a single state, and eight (24%) studied metropolitan areas and districts within a state (or states). The age range of children with ASD studied also varied considerably, with the most common being 0–17 or 0–18 years (n=8; 24%). Six (18%) studies did not report the age range, but explicitly stated that the focus was on children and adolescents.

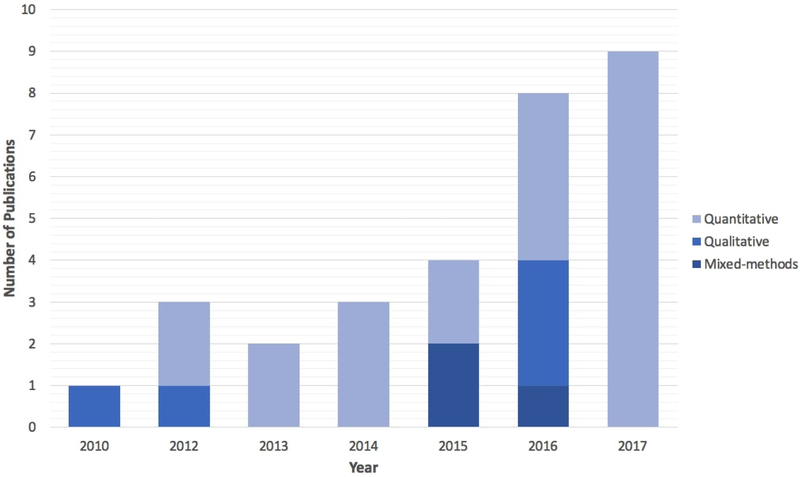

Six (18%) studies were qualitative, 24 (73%) studies were quantitative, and three (9%) utilized mixed-methods. Among the nine studies that involved a qualitative component, six conducted key informant interviews with parents and/or providers, and three conducted focus groups. Among the 27 studies involving a quantitative component, 17 were cross-sectional surveys, while 10 were longitudinal—using either a repeated cross-sectional design (n=5) or a retrospective cohort design (n=5). Figure 2 depicts the time trend of publications, separated by methodological approach.

Figure 2. Methodological Approach of Included Studies by Year.

Note: Publications in 2018 are excluded from this figure in order to show time trends in publications. Data analysis was conducted part-way through 2018.

The majority of provider groups studied were stated broadly. For example, 22 (67%) studies used terms such as “mental health providers”, “primary care providers”, or “health care providers”. This was most often the case when the focus of the study was on access to healthcare writ-large, rather than examining access to a specific portfolio of services. Among studies providing further specificity, the most commonly referenced groups of providers were pediatricians (n=13; 39%), occupational therapists (n=12; 36%), speech therapists (n=11; 33%), physical therapists (n=10; 30%), and psychiatrists (n=8; 24%).

The overall strength of evidence associated with studies was generally low-to-moderate. Eight (24%) studies were low strength of evidence, 17 (52%) studies were moderate strength of evidence, and the remaining eight (24%) were high strength of evidence. In general, those at the lower end of this spectrum had a number of conceptual and methodological issues such as a lack of justification for the research question examined or study design employed, low response rate and sample size for surveys that were suggestive of selection bias, and lack of control for potential confounding variables. On the higher end of this spectrum were studies with clear justification of approach, more sophisticated longitudinal designs that leveraged claims data and national research studies, and analyses that accounted for an array of potential confounders.

We organized results into five topical areas that emerged across studies. They were: (i) qualitative assessments of provider availability and competency, (ii) availability of providers to offer specific models of care in accordance with best practices, (iii) quantitative assessments looking broadly at availability of providers by service type, (iv) the role of insurance mandates in increasing access to providers, and (v) disparities in access to providers—by demographic characteristics. Below, we summarize the key takeaways from each of these, with further details outlined in Tables 2–4.

TABLE 2.

Qualitative Studies

| Authors | Provider Categories | Clinical Populations | Respondents | Sample Size | Study Design | Study Period | Patient Age Range | Geographic Scope | Key Findings | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brookman-Frazee et al., 201220 | Mental health professionals, PhD and MA-level therapists; psychiatrists | Autism spectrum disorders | Parents | N=23 | Semi-structured key informant interviews | Unspecified | 6–19 years old | Southern California | Parents reported that accessing services was stressful, impacted family functioning (eg, led to marital discord and guilt) and was a financial burden. The most-reported barrier to effective services was provider knowledge about treating children with ASD. Some parents reported that providers would admit their lack of skill and refer them elsewhere. | ++ |

| Carbone et al., 201023 | Mental health professionals; pediatricians; primary care providers; psychiatrists; psychologists | Autism spectrum disorders | Parents; pediatricians | N=5; N=9 | Focus group discussions (N=2) | Unspecified | 5–14 years old | Salt Lake City, Utah | Parents reported that primary care providers were too busy to support a medical home. They stated that providers needed more expertise in ASDs, particularly with respect to screening tools and medication prescriptions. Pediatricians cited lack of time, awareness and expertise in supporting a medical home model, as well as lack of up-to-date knowledge as barrier for prescribing medicines. | + |

| Elder et al, 201621 | Primary care providers; service providers; pediatricians; specialists | Autism spectrum disorders | Individuals with ASD, family members, health care providers, educators, and service providers | N=35 | Focus group discussions (N=4), with participatory action research framework | 2014–2016 | Unspecified (children) | North Central Florida | Respondents reported an insufficient number of services and providers for autism care, in addition to difficulty traveling to services, as barriers to early treatment of ASD in rural areas. Another reported barrier was lack of provider knowledge of treatments. To reduce barriers to early treatment, participants suggested increasing funding to train local professionals. | + |

| Levy et al, 20162 | Pediatricians; pediatric subspecialists; therapists | Autism spectrum disorders | Pediatricians; English Speaking parents | N=20; N=20 | Semi-structured key informant interviews | 2011–2012 | 2–5 years old | Greater Philadelphia | Parents reported that many pediatricians were not knowledgeable about traditional treatments and complementary and alternative medicine for ASDs. Due to poor knowledge of diagnosis and treatment pediatricians described themselves as being “more likely to refer patients to subspecialists” despite subspecialists having long waitlists. Pediatricians were also unsure about the scope of their role in making treatment recommendations. | +++ |

| Nolan et al, 201627 | Primary care providers; pediatricians; developmental behavioral pediatricians | Autism spectrum disorders | Primary care providers | N=25 | Focus group discussion (N=4) | 2013 | Unspecified (“children”) | Colorado | PCPs described a lack of knowledge about the medical home model and about current treatments, including medications, for children with ASDs. They also expressed a lack of knowledge of alternative treatments. Other challenges included a lack of time during visits, long wait lists for specialty services, and a lack of qualified personnel in some geographic areas. | ++ |

| Van Cleave et al 201826 | Primary care providers; pediatricians; primary care nurses; neurologists, developmental behavioral pediatricians | Autism spectrum disorders | Primary care providers; health care staff; parents | N=18; N=5; N=6 | Semi-structured key informant interviews | 2015 | Unspecified (“children”) | Northeastern, Midwestern and Western United States | Parents stated that specialty providers didn’t have time to fully review their children’s medical records. Support staff acknowledged a lack of familiarity with various autism-related needs. Specialists felt that pediatricians often didn’t have experience prescribing medicines for autism-related needs, and this created a barrier to care. | ++ |

Note: Strength of evidence: + = weak; ++ = moderate; +++ = strong.

TABLE 4.

Mixed-Methods Studies

| Authors | Provider Categories | Clinical Populations | Respondents | Sample Size | Study Design | Study Period | Patient Age Range | Geographic Scope | Key Findings | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hidalgo et al, 201524 | Pediatricians; primary care providers | Autism spectrum disorders | Primary caregivers | N=46 | Semi-structured key informant interviews and paper-based survey | Unspecified | 2–7 years old | Northwestern United States | 20% of families identified a challenge with limited services and/or types of services available. Several parents noted a need for at-home services. Families above the poverty line were more likely to mention too few services available than those below the poverty line (p = 0.04). | ++ |

| Russell and McCloskey, 201622 | Primary care providers; therapists; ABA therapists; specialists | Autism spectrum disorders | Parents | N=11 | Semi-structured key informant interviews and paper-based survey | Unspecified | 4–17 years old | Upstate New York | Parents described their interactions with primary care providers as narrowly restricted to physical health, and stated that the medical home was strictly for medical needs. Several parents connected this to knowledgeability of providers regarding autism. Parents also articulated that specialty services for ASDs were too far away to be conveniently accessed. | + |

| Taylor and Henninger, 201524 | Mental health counselors; speech therapists; occupational therapists; social works; physical therapists | Autism spectrum disorders | Parents | N=39 | Semi-structured key informant interviews and paper-based survey | Unspecified | 17–22 years old | Unspecified | 43.6% of youth received mental health services or counseling, with 15.4% stating an unmet need. 35.9% received speech therapy or communication services, with 10.3% stating an unmet need. 25.6% received occupational/life skills therapy or training, while 30.8% stated an unmet need. 33.3% of parents described the location of services as a barrier, and 25.6% described lack of service availability as a barrier. | ++ |

Note: Strength of evidence: + = weak; ++ = moderate; +++ = strong.

Qualitative Assessments of Provider Availability and Competency

Among the nine articles that included a qualitative component, eight contained information obtained from parents, caregivers and legal guardians about provider availability and competence—typically with the focus on a certain portfolio of needs, such as behavioral healthcare (Table 2).2,20–26 Across studies, parents reported that providers often lacked the knowledge to address autism-specific needs,2,20–22 particularly in the area of prescribing,23 that providers lacked time to adequately address autism-related needs,23,26 that there was insufficient availability of providers to meet their needs,21,24 that distance traveled was a significant barrier to care—especially for specialty care,21,22 and at-home services could potentially be utilized as a mechanism to address this.24

Four qualitative studies contained interviews with health providers and medical staff2,23,26,27—most often pediatricians (n=3) who cited a lack of time and knowledge to fully support the needs of children with ASD,23,27 and described being unsure about the scope of their role in making treatment recommendations,2 largely corroborating the views of parents. Specialists likewise stated that pediatricians often don’t have experience prescribing medication for autism-related needs.26

Availability of Providers to Offer Care in Accordance with Best Practices

Three frameworks of autism-related healthcare services were examined in papers that addressed provider adoption of healthcare delivery models: family-centered care, the medical home model, and transitional care for adolescents. Four studies addressed family-centered care.3,28–30 One of these, relying on a national sample from the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (NS-CSHCN; 2009), found that children with ASD who lacked family-centered care (49% of the sample) were 1.9-times more likely to experience unmet need for specialty services (p<0.001).3 A second, also using NS-CSHCN (2009), found that White children with ASD were more likely to have access to family-centered care (54%) compared to non-White respondents (42%; p<0.001).29 These estimates were similar to a third, web-based study, which concluded only 47% of respondents had access to family-centered care.30 However, a fourth study using NS-CSHCN (2009) found a larger percentage of parents (75%−83%) reported care as family-centered and compassionate.28 Most likely, methodology accounts for this, as the final study relied on a composite of four measures that only partially overlapped with those used by others.

Six studies, three qualitative,22,23,27 examined provider care through the lens of the medical home. A focus group study with parents in Utah, described that PCPs were too busy to support a medical home.23 Another, in upstate New York, reported that PCPs restricted the medical home framework to direct medical needs.22 The third study, consisting of focus group discussions with PCPs in Colorado, concluded that physicians lacked familiarity with the medical home model.27

Limited availability of support for the medical home model, as outlined in the qualitative research, was corroborated by evidence from quantitative surveys. One, a national web-based survey of parents, found that only 19% of respondents’ reported that their children had access to all components of a medical home.30 A web-based survey of Kentucky parents studying components of the medical home model found that a sizable percentage of parents (41%) felt their doctor’s ability to discuss autism care was poor.31 Lastly, a survey completed by pediatricians in California identified common barriers to providing a medical home for children with ASD. Most common barriers were: a lack of time to conduct administrative tasks, a lack of administrative staff, and a lack of time for office visits.32

Two studies looked at transitional care among children with ASD. The first, a cross-sectional, web-based survey largely conducted in Missouri found that only 15% of respondents reported receiving adequate healthcare transition services, with 62% reporting unmet need to discuss transition to adulthood healthcare needs.33 The second, comprising in-person interviews (geographic scope unspecified), found similar unmet need for transitional care services: for example, only 26% of youth had received occupational or life skills training.25

Quantitative Assessments of Provider Availability, by Service Type

Eleven studies examined availability of providers for autism-related services (Table 3).3,28,34–42 Three focused on questions of unmet and perceived need.3,34,35 Two, by the same team, utilized NS-CSHCN data to examine this question and found that parents reported that 25% of children with ASD had unmet need for therapy services in 2009 (compared to 16% for individuals with other special needs; p<0.001),35 and that unmet therapy needs were 1.5-times greater in 2009 compared to 2005 (p=0.006).34 The third, using NS-CSHCN cross-sectional data (2009), found that unmet need varied by type of service: ranging from 13% for a specialty doctor to 29% for home healthcare. 36% of respondents expressed at least one unmet specialty service need.3

TABLE 3.

Quantitative Studies

| Authors | Provider Categories | Clinical Populations | Respondents | Sample Size | Study Design | Study Period | Patient Age Range | Geographic Scope | Key Findings | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austin et al, 201642 | Registered nurses; developmental behavioral pediatricians; psychiatrists | Autism spectrum disorders | Medical centers | N=2 | Repeated cross-sectional study implemented at two medical centers | 2012–2013 | 0–14 years old | Cincinnati, Ohio; Columbus, Ohio | An intervention to streamline autism services at two medical centers reduced the number of children 3–5 years old on their waitlist from 330 (pre-intervention) to 0 (post-intervention), and reduced the number of children 614 years old from 866 to 387. Delay in care also declined. Statistical significance not reported. | ++ |

| Barry et al, 201712 | Healthcare providers of autism-related services; behavioral therapists; speech therapists; occupational therapists; physical therapists | Autism spectrum disorders | Primary care providers | N=106,977 | Retrospective cohort study | 2008–2012 | 0–21 years old | United States | Across 46 states with an insurance mandate covering autism-related services, the monthly probability of utilizing autism-specific health care services was 27.9%, versus 25.0% in non-mandate states (p<0.05). For ASD-specific outpatient services, the probability was 27.7% versus 24.9% (p<0.05), and for behavioral and functional therapy services it 20.8% versus 18.2% (p<0.05), respectively. | +++ |

| Becerra et al, 201736 | ABA therapists; family physicians; occupational therapists; physical therapists; speech therapists | Autism spectrum disorders | Parents | N=1,155 | Cross-sectional paper-based survey | 2012 | 0–17 years old | California; Northwestern United States; Georgia | 37% of patients reported ever using ABA; 77% reported family physician visits; 55% reported OT visits; 25% reported PT visits; 60% reported speech therapy visits. Additional categories also discussed, including school-based supports. | ++ |

| Benevides et al, 201635 | Physical therapists; speech therapists; occupational therapists | Autism spectrum disorders | Caregivers and legal guardians | N=5,113 (ASDs); N=71,294 (other Special needs) | Repeated cross-sectional telephone-based survey, using pooled estimates (NS-CSHCN, 2005–2006, 2009–2010) | 2005–2006; 2009–2010 | 3–17 years old | United States | Caregivers of children with ASDs were 1.4 times more likely to report an unmet need for therapy compared to caregivers of children with other special needs (p<0.05)—24.7% v 16.3%. This unmet need was greater in 2009–2010 than 2004–2005 (p<0.05). | ++ |

| Benevides et al, 201734 | Physical therapists; speech therapists; occupational therapists | Autism spectrum disorders | Caregivers and legal guardians | N=5,178 (ASDs); N=20,566 (ADHD); N=1,183 (cerebral palsy) | Repeated cross-sectional telephone-based survey, using pooled estimates (NS-CSHCN, 2005–2006, 2009–2010) | 2005–2006; 2009–2010 | 0–18 years old | United States | More than 75% of children with either ASD or cerebral palsy (CP) had a perceived therapy need across time points. Unmet need was greater among children with ASD compared to ADHD (OR: 1.66, p<0.001), but not different from those with CP (p=0.08). Across all three groups, unmet therapy needs were greater in 2009 than 2005 (OR: 1.41, p<0.001). | ++ |

| Broder-Fingert et al, 201315 | GI/nutrition Specialty providers; neurologists; psychiatrists; psychologists | Autism | NA - Electronic health records of patients | N=3,615 | Retrospective cohort study | 2000–2011 | 2–21 years old | Massachusetts | 43% of children in care had a subspecialty care visit over the 11-year study period. Among African American children, 29.8% had a subspecialty visit, compared to 36.9% of white children. Adjusted odds ratios were significant for all categories: Gl/nutrition (OR: 0.32), neurology (OR: 0.52), and psychology/psychiatry (OR: 0.44). A similar pattern was observed when comparing Hispanic children to white children. | ++ |

| Cheak-Zamora and Farmer, 20153 | Primary care providers; specialty doctors; mental health counselors; physical therapists; occupational therapist; speech therapists | Autism spectrum disorders | Parents | N=3,055 | Cross-sectional telephone-based survey (NS-CSHCN, 2009–2010) | 2009–2010 | 0–17 years old | United States | Among children with ASD, 25% had an unmet need for physical, occupational, or speech therapy, 13% for a specialty doctor, 29% for home health, 22% for mental health services, and 26% for substance abuse treatment/counseling. Parents who reported their children lacked access to family-centered care were 1.86 times more likely (p<.001) to experience at least one unmet need for specialty services. | +++ |

| Cheak-Zamora et al, 201433 | Health care providers | Autism spectrum disorders | Caregivers and legal guardians | N=101 | Cross-sectional web-based survey | 2009–2010 | 12–17 years old | United States; Missouri | Only 14.9% of youth with ASD received adequate health care transition services. 56% of respondents reported an unmet need to discuss health insurance retention; 62% reported an unmet need to discuss transition to adulthood health care needs. 64% of youth with ASDs in the Northeast were encouraged to take appropriate responsibility for their health care needs--compared to 20% in the Midwest, 29% in the South, and 36% in the West; p < 0.05. | ++ |

| Doshi et al, 201729 | Primary care providers; specialty care providers; physical therapists; occupational therapists; speech therapists; mental Health counselors | Autism spectrum disorders | Parents | N=4,967 | Repeated cross-sectional telephone-based survey (NS-CSHCN, 2005–2006, 2009–2010) | 2005–2010 | 0–17 years | United States | In 2005–2006, 53.4% of White respondents and 38.5% of nonWhite respondents reported their children had access to family-centered care (p<0.001). In 20092010, these figures rose to 53.6% and 41.9%, respectively (p<0.001). | +++ |

| Farmer et al, 201430 | Primary care providers; specialty doctors; mental health counselors; physical therapists; occupational therapist; speech therapists | Autism spectrum disorders | Parents | N=371 | Cross-sectional web-based survey | 2009–2010 | 0–17 years old | United States; Missouri | 19% of respondents stated their child with ASD had access to all components of a medical home: almost all (96%) had a personal doctor or nurse; 92% had a usual source for both sick and well care; 47% had access to family-centered care; 30% had access to coordinated care. 42% reported an unmet need for speech therapy, 31% for specialty care, 46% for occupational or physical therapy, 65% for behavioral therapy, and 41% for mental health services. | ++ |

| James et al, 201448 | Occupational therapists; occupational therapist assistants | Autism spectrum disorders | Occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants | N=1,396 | Cross-sectional web-based survey | Unspecified | 0–6 years old | United States | 58% of occupational therapy practitioners felt “most prepared” to discuss current research evidence about autism with families; 52% felt “most prepared” to explain information about autism to families of “differing” cultures. | + |

| Kalb et al, 201740 | Mental health professionals; psychiatrists, psychologists; social workers | Autism spectrum disorders | Psychiatrists | N=866 | Cross-sectional web-based survey | 2015 | Unspecified (“children”) | United States | 43% of reporting child psychiatrists stated that 0–5% of their patient population comprised individuals with ASDs. 24% of respondents did not “often” or “frequently” accept a child with a history of mental health crisis. Psychiatrists who treated youths with ASDs >5% of the time were more likely to keep an appointment open in the event a child had a mental health crisis (p < 0.05). | ++ |

| Lin and Yu, 201544 | Primary care providers | Autism spectrum disorders | Caregivers and legal guardians | N=3,840 (English primary language); N=138 (non-English primary language) | Cross-sectional telephone-based survey (NS-CSHCN, 2009–2010) | 2009–2010 | 2–17 years old | United States | Among English-speaking households, 11.3% did not have usual sources for sick and well care, and 6.6% did not have a personal doctor or nurse. Among non-English speaking households, these figures were 10.9% and 2.4%, respectively (p > 0.05). | ++ |

| Magaña et al, 201346 | Physical therapists; speech therapists; occupational therapists; autism therapists; mental health providers | Autism spectrum disorders | Autism spectrum disorders | N=48 (ASD, Latino); N=56 (ASD, White) | Cross-sectional telephone-based survey | Unspecified | 2–22 years old | Wisconsin | Among White respondents, unmet services need was 16.1% for physical therapy, 14.3% for occupational therapy, 12.5% for speech therapy, 10.7% for psychological services and 23.2% for intensive autism therapy. Among Latino respondents, these figures were 18.8%, 20.8%, 18.8%, 27.1% and 43.8%, with the latter two rates being significantly higher (p<0.05) compared to White respondents. | + |

| Mclaughlin et al, 201839 | Pediatricians; primary care physicians; developmental pediatricians; neurologists; psychologists; psychiatrists | Autism spectrum disorders | Parents | N=1,454 | Cross-sectional web-based survey | 2016 | 4–18 years old | United States | 33.3% of parents of children with ASDs who had a history of elopement (wandering) reported having ever received guidance for elopement behavior from a health professional: 11.1% from a primary care provider, 12.1% from a developmental pediatrician or neurologist, and 10.1% from a psychologist or psychiatrist. | ++ |

| Okumura et al, 201732 | Primary care pediatricians and non-primary care/subspecialist pediatricians (hospitalists, urgent care providers, and “‘other’”) | Autism spectrum disorders; neurofibromatosis | Pediatricians | N=1,163 | Cross-sectional email- and paper-based survey | 2014 | Unspecified (“children”) | California | There was no association between having a social worker or case manager on-site at health clinics and pediatricians reporting they were comfortable treating a child with an ASD. The top three barriers among pediatricians to providing a medical home to a child with autism or neurofibromatosis are a lack of time to conduct administrative tasks, a lack of administrative staff, and a lack of time for office visits. Over 90% of primary care pediatricians said they felt comfortable or somewhat comfortable providing a medical home to both an autistic child whose family had high social resources and to an autistic child whose family had low social resources. | ++ |

| Pickard and Ingersoll, 201647 | Therapists, doctors; ABA, alternative therapies, higher quality services, in-home services, integrated services/case management, occupational therapy, parent training, respite care, social skills, speech therapy | Autism spectrum disorders | Parents | N=244 | Cross-sectional web-based survey | Unspecified | 2–17 years old | United States | Parents of children with ASDs who reported high socioeconomic status (SES) more frequently stated service needs for ABA therapy (25.0%), alternative therapies (20.2%) and occupational therapy (15.5%)—compared to those with low SES, who stated these needs 23.9%, 24.6% and 10.0% of the time, respectively. Statistical significance was not reported. Qualitative evidence indicated that socioeconomic differences in stated service needs may relate to parent knowledge about service options. | + |

| Roizen et al, 201741 | Developmental pediatricians (comprised of neuro developmental disabilities and developmental—behavioral physicians) | Autism; ADHD | Developmental pediatricians | N=50 | Cross-Sectional paper-based survey | 2013–2014 | Unspecified (“children”) | Philadelphia | 90% of developmental pediatricians reported interest or expertise (I/E) in treating autism spectrum disorders (autism and Asperger syndrome). Those out of fellowship for 10 or fewer years vocalized greater I/E in treating ASD compared to those out of fellowship for greater than 10 years (p < 0.05). | + |

| Saloner and Barry, 201743 | Pediatricians; psychiatrists; healthcare providers | Autism spectrum disorders | NA - Claims data of children with ASDs | N=1,772 | Repeated cross-sectional study | 2009–2013 | 0–18 years old | Kansas | In 2009, prior to a 2011 law mandating coverage of ASD treatments under the state employee health plan (SEHP) in Kansas, the mean number of claims for ASD treatment was 8.9 per year among a SEHP enrollees and 5.5 among other private insurances. After implementation of the mandate (2013), this figure increased markedly to 35.3 claims among SEHP enrollees while only increasing to 6.4 among others (p < 0.05). | +++ |

| Sobotka and Vander Ploeg Booth, 201628 | Primary care providers; health care providers | Autism spectrum disorders | Parents | N=2,859 | Cross-sectional telephone-based survey (NS-CSHCN, 2009–2010) | 2009–2010 | 2–17 years old | United States | 95% of parents reported that their child with ASD had a primary care provider. 71% reported that primary care was usually or always comprehensive; 87% found care to be culturally effective, and 75% found care to be family-centered and compassionate. Among those reporting a need for care coordination, only 14% were usually or always satisfied. | ++ |

| St Amant et al, 201845 | ABA therapists; therapists | Autism spectrum disorders | NA - Electronic health records of patients | N=152 | Retrospective cohort study | 2009–2011 | 3–21 years old | Los Angeles, California | Children eligible for California Development Disability Services (CA DDS) received an average of 3 hours of services a week. Children of parents whose primary language was English were 4.8 times more likely to have a social skills goal on their IEP (p = 0.001) and 11 times more likely to have a communication skill goals (p = 0.007). They also received 0.24 more hours of services from the CA DDS. | +++ |

| Stein et al, 201238 | Mental health professionals | Autism spectrum disorders | NA - Claims data of children with ASDs enrolled in Medicaid | N=8,064 | Retrospective cohort study | 2006–2010 | 0–18 years old | Pennsylvania | Between 2009–2010, 44.7% of Medicaid-enrolled children with ASD used outpatient mental health services, 5.4% used inpatient mental health services, and 86.2% used community-based services. | +++ |

| Stuart et al, 201737 | Mental health professionals; speech therapists; occupational therapists; physical therapists | Autism spectrum disorders | NA - Claims data of children with ASDs | N=38,928 | Retrospective cohort study | 2007–2012 | 0–18 years old | United States | Between 2010 and 2012, 2.4% of children with ASDs in the sample used inpatient mental health services on an annual basis. 69.7% used outpatient mental health services on an annual basis, 17.5% used outpatient psychotropic medication management services, 46.5% used outpatient psychotherapy services, 11.3% used speech therapy services, and 6.3% used occupation or physical therapy services. | +++ |

| Williams et al, 201231 | Primary care providers; pediatricians; psychiatrists; developmental pediatricians; neurologists | Autism spectrum disorders | Physicians; parents | N=25; N=114 | Cross-sectional web-based survey | Unspecified | 2–35 years old | Kentucky | 83% of parents reported their physician provided enough time with their child; 69% reported that physicians did not provide adequate information about community services; 41% felt their doctor’s ability to discuss treatment options for ASDs was poor. 68% of physicians reported good/excellent ability providing preventative care for children with ASDs; only 16% reported good/excellent ability supporting alternative interventions. | + |

Note: Strength of evidence: + = weak; ++ = moderate; +++ = strong. ABA = applied behavioral analysis; ASD = autism spectrum disorder.

Five studies investigated utilization of services by provider type.28,36–39 One cross-sectional study, using NS-CSHCN (2009), concluded 95% of children with ASD had a PCP, though frequency of interactions was not reported.28 By contrast, a cross-sectional regional study of Kaiser Permanente clients found that 77% of clients had ever received a family physician visit, compared to 60% for speech therapy, 55% for occupational therapy, 37% for ABA and 25% for physical therapy.36 A third study, a retrospective cohort study looking nationally at employer-based claims, found 70% of children with ASD in the sample had utilized outpatient mental health services for ASD-related care annually between 2010–2012, after the introduction of a mental health parity law.37 Lower rates of service utilization were found for speech therapy (11%) and occupational or physical therapy (6%). A similar study using Pennsylvania Medicaid-enrollees claims from 2009–2010, found that 45% of children with ASD had utilized outpatient mental health services, while 86% had utilized community-based services such as home-based behavioral therapy over this period.38 Lastly, one cross-sectional, web-based survey looked specifically at provider availability and competency to address the issue of elopement (wandering) among children with ASD nationally, and found that only one-third of parents had received any guidance from a health professional on the issue.39

A final subset of studies examined availability of services from the provider perspective.40–42 In one web-based survey of child psychiatrists throughout the U.S., 43% reported that < 5% of their patient population comprised children with ASD.40 Another web-based study of developmental pediatricians in the greater Philadelphia area found that 90% reported interest or expertise in treating ASD, with graduates in the past 10 years more likely to express such expertise.41 Lastly, a repeated cross-sectional study in Ohio looked at delays in autism-related services at two medical centers, before and after introducing a new quality improvement protocol, and found that once the protocol was in place, the number of children with ASD on a waitlist to receive care declined from 99 individuals pre-intervention to 12 post-intervention.42

Role of Insurance Mandates in Increasing Access to Providers

While a number of studies discussed insurance mandates by states that require private health insurers to cover healthcare services for children with ASD, only four articles satisfied inclusion criteria: meaning they contained empirical evidence regarding the effect of insurance mandates on outcomes of interest, such as increased service utilization. While insurance mandates are designed to increase the ability for families to receive autism-related services, over the long-run this has the downstream effect of drawing a greater workforce into states with such mandates. As such, we focused on those outcomes reporting availability of health workforce and associated services after mandates went into effect.

One of these studies, a national-level retrospective cohort analysis, compared utilization of autism-related services in mandate versus non-mandate states, and found non-significant differences.12 The second, using a similar approach but looking specifically at the state of Kansas, found that a state-wide insurance mandate disproportionately increased claims for ASD treatment among state employees (from 8.9 claims per year to 35.3) compared to those with other forms of insurance (5.5 to 6.4) (p<0.01), a finding consonant with the mandate’s focus on the public sector.43 A third study, looking retrospectively at the number of children receiving Medicaid services for ASD in Pennsylvania, found a 54% increase in those using services from 2006–2007 (N=5,221) to 2009–2010 (N=8,064), an interval over which a state-wide insurance mandate was introduced.38 Lastly, a longitudinal study using repeated cross-sectional data from NS-CSHCN found that racial disparities in access to family-centered care were unaffected by the introduction of insurance mandates at a national level.29

Disparities in Access to Autism-Related Service Providers

A final set of studies examined disparities in access to specific types of autism-related services for children.15,24,29,44–48 Two studies investigated racial and ethnic differences in service utilization.15,46 One of these, a retrospective cohort study in Massachusetts, examined utilization of subspecialty care within Massachusetts General Hospital’s health system over an 11-year period and found that 29.8% of African American children had a subspecialty visit compared to 36.9% of White children (p<0.05). A similar pattern emerged when comparing Hispanic and non-Hispanic White children.15 The second, a telephone-based survey in Wisconsin, found that unmet need for psychological services and intensive autism therapy was higher among Hispanic children (27.1% and 43.8%, respectively) compared to non-Hispanic White children (10.7% and 23.2%; p<0.05).46

Prior studies also investigated language-related disparities. In a national examination of NS-CSHCN data, authors found no significant differences (p>0.05) between households for whom English was the primary language versus not in terms of having a usual source of sick care, and having a personal doctor or nurse.44 By contrast, a California-based study examining electronic medical records from 2009–2011 concluded that children with ASD in primary English speaking households received, on average, 0.24 more hours of services per week from CA Development Disability Services compared to households in which English wasn’t the primary language (p=0.03).45

Two additional studies examined socio-economic (SES) disparities in access to autism-related services. The first, a series of semi-structured and structured interviews in the Northwestern U.S., found that families above the poverty line were more likely to mention too few services available for autism care for children, compared to families below the poverty line (p=0.04).24 The second found divergent trends at a national level: those of lower SES more frequently reported service needs for ABA (25%) and occupational therapy (16%) compared to those of higher SES (24% and 10% respectively), and less frequently reported ‘no needs’ (0% versus 8%).47

DISCUSSION

The 33 studies included in this review identify a number of workforce related challenges for families seeking treatment for children with ASD—including lack of preparation of primary care providers (PCPs) to serve children with ASD, lack of availability of specialty providers, and disparities in access to ASD services by sociodemographic and geographic factors. Each of these underscores key areas for progress in provider training and deployment.

With regard to the role of PCPs, the evidence indicates a large majority of children with ASD have an identified PCP,28 and that a slightly smaller majority seeks primary care on a consistent basis.36 However, qualitative studies indicate that parents feel the quality of the services they receive from PCPs is inadequate, apart from addressing narrow medical needs,22 and that PCPs lack familiarity with issues confronting children with ASD.20 Against this backdrop, there have been several recent initiatives seeking to further enhance the care PCPs provide for children with ASD—including telementoring initiatives like Project ECHO,50 and guided curricula like the Autism Case Training (ACT) curriculum advanced by the CDC49 and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. More information is needed, however, about the uptake of these initiatives and their impact on the care being received by children with ASD.

Weak workforce suitability was also reflected in terms of best practices for service provision from PCPs: including family-centered care, transitional care, and the medical home model. Access to family-centered care was generally at or below 50%, with less availability among minorities.29 The single nationally-representative study on utilization of the medical home model found that only one in five children had access to all components.30 Both quantitative and qualitative studies elucidated reasons for this—including lack of provider time and familiarity and weak support staff.27,32 These findings are consistent with a broader pool of evidence tracing challenges in PCPs’ ability to meet their patients’ mental health needs. Findings from demonstration projects that have successfully implemented comprehensive family-centered care—such as the Pediatric Alliance for Coordinated Care in Boston51—may offer insights as to ways these trends could be reversed.52

Studies that included analyses on more specialized cadres of providers offered a similar picture. For example, among those that discussed occupational therapy services, unmet need varied from 14–46%, depending on geography and timeframe.30,46 Similar findings were reported for speech therapy, physical therapy, ABA and other forms of home-based care—with unmet needs reported as high as 65%.30 Such wide-ranging estimates highlight two points. First, there is marked heterogeneity in estimates—contingent on the geography and demographic characteristics of those studied. While studies have outlined similar gaps in unmet need for children with special needs more broadly,53–55 the levels of unmet needs for autism-related care are particularly disconcerting. Second, more research is needed to fill in missing details. For example, several factors may contribute to the observed disparities in unmet need among African American, Hispanic, and immigrant families15,44,46—such as lower levels of access and community awareness surrounding autism, lack of cultural competence in care delivery on the part of providers, and limited ability to pay for diagnostic and therapeutic services.56,57

Our findings highlight two potential directions for future research. First, with the exception of a few qualitative investigations, studies have focused almost exclusively on the quantity rather than the quality of providers. Second, we found virtually no quantitative studies on the geographic distribution of services within the catchment areas that authors examined. Only one study utilized geospatial analysis, but was excluded due to the older study period (2002–2008) and a focus on autism identification rather than service provision. Both seem promising for further exploration, as the underlying data structures could be used as a valuable tool for consumers seeking to identify local providers offering autism-related services.58

This study includes several limitations. While this review aimed to identify studies that explore health workforce issues regarding autism-related healthcare for children, it is likely that some studies were not captured by search criteria. By way of example, studies on state insurance mandates for autism services are only related to workforce concerns insofar as they report on uptake of services following a demand-side intervention. Wherever possible, we tried to be expansive in our inclusion of studies that may report on statistics of interest. Second, and relatedly, we acknowledge that there are additional health provider specialties, such as speech-language pathologists, that are beyond the scope of what we investigated and also support autism care for children. We explicitly focused on cadres for which there is broad consensus about the integral role they play in providing health services for children with ASD.

Third, while we elected to restrict inclusion to those studies utilizing data sources within the previous 10 years, there were several studies published between 2008 and 2018 that utilized methodologically-rigorous approaches with older data sources. Lastly, the evidence we review includes quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods research. Synthesizing evidence from these domains is inherently challenging, given that they are often designed to answer different sets of research questions. We felt that—to holistically summarize the existing body of evidence on workforce issues—it was necessary to incorporate all three; and the methodological framework selected explicitly accounts for this.

In summary, we find—where evidence is available—that the health workforce for autism-related health services for children needs greater investment, both in terms of the number of providers as well as the competencies of those that currently serve children with ASD. While we find that there is a growing literature exploring the dynamics of workforce availability and distribution, the current strength of evidence is weak-to-moderate. The magnitude of need for autism care should continue to motivate further research in this area. Hopefully, the knowledge gained will allow stronger advocacy for an improved workforce to support children with ASD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Aaron Kofner, MS, of the RAND Corporation, for his involvement in the early conceptualization of this manuscript. We would also like to thank those authors who made the construction of this manuscript possible by conducting research on the availability and quality of autism-related child healthcare services in the U.S.

Financial Disclosure Statement

Dr. McBain has received research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Health Resources and Services Administration, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, and Department of Defense. He is a member of the advisory board of Water Ecuador. Ms. Kareddy has received research support from the United States – India Educational Foundation. Dr. Cantor has received research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, National Cancer Institute, The Pew Charitable Trusts, Los Angeles County, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Department of Defense, and Social Security Administration. Dr Stein has received support from the National Institute of Mental Health, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Dr. Yu has received support from the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities, and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. All authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH112760).

Dr. McBain served as the statistical expert for this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.CDC. Data and Statistics | Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | NCBDDD | CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html. Published April 26, 2018. Accessed July 2, 2018.

- 2.Levy SE, Frasso R, Colantonio S, et al. Shared Decision Making and Treatment Decisions for Young Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(6):571–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheak-Zamora NC, Farmer JE. The impact of the medical home on access to care for children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(3):636–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolko DJ, Perrin EC. The Integration of Behavioral Health Interventions in Children’s Health Care: Services, Science, and Suggestions. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43(2):216–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roane HS, Fisher WW, Carr JE. Applied Behavior Analysis as Treatment for Autism Spectrum Disorder. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2016;175:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Case-Smith J, Arbesman M. Evidence-based review of interventions for autism used in or of relevance to occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 2008;62(4):416–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):e17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Social Skills Interventions for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders - Bellini Scott, Peters Jessica K., Benner Lauren, Hopf Andrea, 2007. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/07419325070280030401. Accessed July 2, 2018.

- 9.Thomas CR, Holzer CE. The continuing shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(9):1023–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiri G, Warfield ME. Unmet need and problems accessing core health care services for children with autism spectrum disorder. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(5):1081–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leslie DL, Iskandarani K, Velott DL, et al. Medicaid Waivers Targeting Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder Reduce The Need For Parents To Stop Working. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(2):282–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barry CL, Epstein AJ, Marcus SC, et al. Effects Of State Insurance Mandates On Health Care Use And Spending For Autism Spectrum Disorder. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(10):1754–1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basco WT, Rimsza ME, Committee on Pediatric Workforce, American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrician workforce policy statement. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):390–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalkbrenner A, Daniels J, Emch M, Morrissey J, Poole C, Chen J-C. Geographic Access to Health Services and Diagnosis with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(4):304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broder-Fingert S, Shui A, Pulcini CD, Kurowski D, Perrin JM. Racial and ethnic differences in subspecialty service use by children with autism. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children With Disabilities, Duby JC. Role of the medical home in family-centered early intervention services. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):1153–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.PRISMA. PRISMA Statement. http://www.prisma-statement.org/. Published 2015. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- 18.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub; 2013.

- 19.Pluye P, Gagnon M-P, Griffiths F, Johnson-Lafleur J. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in Mixed Studies Reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(4):529–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brookman-Frazee L, Baker-Ericzén M, Stadnick N, Taylor R. Parent Perspectives on Community Mental Health Services for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Child Fam Stud. 2012;21(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elder JH, Brasher S, Alexander B. Identifying the Barriers to Early Diagnosis and Treatment in Underserved Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) and Their Families: A Qualitative Study. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2016;37(6):412–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell S, McCloskey CR. Parent Perceptions of Care Received by Children With an Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31(1):21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carbone PS, Behl DD, Azor V, Murphy NA. The Medical Home for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Parent and Pediatrician Perspectives. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(3):317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hidalgo NJ, McINTYRE LL, McWHIRTER EH. Sociodemographic differences in parental satisfaction with an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2015;40(2):147–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor JL, Henninger NA. Frequency and correlates of service access among youth with autism transitioning to adulthood. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(1):179–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Cleave J, Holifield C, Neumeyer AM, et al. Expanding the Capacity of Primary Care to Treat Co-morbidities in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. July 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nolan R, Walker T, Hanson JL, Friedman S. Developmental Behavioral Pediatrician Support of the Medical Home for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2016;37(9):687–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sobotka SA, Francis A, Vander Ploeg Booth K. Associations of family characteristics with perceptions of care among parents of children with autism. Child Care Health Dev. 2016;42(1):135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doshi P, Tilford JM, Ounpraseuth S, Kuo DZ, Payakachat N. Do Insurance Mandates Affect Racial Disparities in Outcomes for Children with Autism? Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(2):351–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farmer JE, Clark MJ, Mayfield WA, et al. The relationship between the medical home and unmet needs for children with autism spectrum disorders. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(3):672–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams PG, Tomchek S, Grau R, Bundy MB, Davis DW, Kleinert H. Parent and physician perceptions of medical home care for children with autism spectrum disorders in the state of Kentucky. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51(11):1071–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okumura MJ, Knauer HA, Calvin KE, Takayama JI. Pediatricians’ Comfort Level in Caring for Children With Special Health Care Needs. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(6):678–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheak-Zamora NC, Farmer JE, Mayfield WA, et al. Health care transition services for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Rehabil Psychol. 2014;59(3):340–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benevides TW, Carretta HJ, Ivey CK, Lane SJ. Therapy access among children with autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, and attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder: a population-based study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(12):1291–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benevides TW, Carretta HJ, Lane SJ. Unmet Need for Therapy Among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Results from the 2005–2006 and 2009–2010 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(4):878–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Becerra TA, Massolo ML, Yau VM, et al. A Survey of Parents with Children on the Autism Spectrum: Experience with Services and Treatments. Perm J. 2017;21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stuart EA, McGinty EE, Kalb L, et al. Increased Service Use Among Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder Associated With Mental Health Parity Law. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(2):337–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stein BD, Sorbero MJ, Goswami U, Schuster J, Leslie DL. Impact of a private health insurance mandate on public sector autism service use in Pennsylvania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(8):771–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLaughlin L, Keim SA, Adesman A. Wandering by Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Key Clinical Factors and the Role of Schools and Pediatricians. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2018;39(7):538–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalb LG, Stuart EA, Mandell DS, Olfson M, Vasa RA. Management of Mental Health Crises Among Youths With and Without ASD: A National Survey of Child Psychiatrists. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(10):1039–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roizen N, Stein REK, Silver EJ, High P, Augustyn MC, Blum NJ. Academic Developmental-Behavioral Pediatric Faculty at Developmental-Behavioral Pediatric Research Network Sites: Changing Composition and Interests. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2017;38(9):683–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Austin J, Manning-Courtney P, Johnson ML, et al. Improving Access to Care at Autism Treatment Centers: A System Analysis Approach. Pediatrics. 2016;137 Suppl 2:S149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saloner B, Barry CL. Changes in spending and service use after a state autism insurance mandate. Autism. November 2017:1362361317728205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin SC, Yu SM. Disparities in Healthcare Access and Utilization among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder from Immigrant Non-English Primary Language Households in the United States. Int J MCH AIDS. 2015;3(2):159–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.St Amant HG, Schrager SM, Peña-Ricardo C, Williams ME, Vanderbilt DL. Language Barriers Impact Access to Services for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(2):333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Magaña S, Lopez K, Aguinaga A, Morton H. Access to diagnosis and treatment services among latino children with autism spectrum disorders. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2013;51(3):141–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pickard KE, Ingersoll BR. Quality versus quantity: The role of socioeconomic status on parent-reported service knowledge, service use, unmet service needs, and barriers to service use. Autism. 2016;20(1):106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.James LW, Pizur-Barnekow KA, Schefkind S. Online survey examining practitioners’ perceived preparedness in the early identification of autism. Am J Occup Ther. 2014;68(1):e13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.CDC. Autism Case Training: A Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics Cirriculum. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/autism/case-modules/index.html. Accessed November 8, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Autism Speaks. Distance training improves autism care, shortens diagnosis time. Autism Speaks. https://www.autismspeaks.org/science-news/distance-training-improves-autism-care-shortens-diagnosis-time. Published 2018. Accessed March 18, 2019.

- 51.Palfrey JS, Sofis LA, Davidson EJ, et al. The Pediatric Alliance for Coordinated Care: evaluation of a medical home model. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5 Suppl):1507–1516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gabovitch E, Curtin C. Family-Centered Care for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review. Marriage & Family Review. 2009;45:469–498. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skinner AC, Slifkin RT, Mayer ML. The Effect of Rural Residence on Dental Unmet Need for Children With Special Health Care Needs. The Journal of Rural Health. 2006;22(1):36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeVoe JE, Krois L, Stenger R. Do Children in Rural Areas Still Have Different Access to Health Care? Results from a Statewide Survey of Oregon’s Food Stamp Population. J Rural Health. 2009;25(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McManus BM, Lindrooth R, Richardson Z, Rapport MJ. Urban/Rural Differences in Therapy Service Use Among Medicaid Children Aged 0–3 With Developmental Conditions in Colorado. Academic Pediatrics. 2016;16(4):358–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi L, Stevens GD. Disparities in access to care and satisfaction among U.S. children: the roles of race/ethnicity and poverty status. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(4):431–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Campinha-Bacote J The Process of Cultural Competence in the Delivery of Healthcare Services: A Model of Care. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13(3):181–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daniels J, Schwartz J, Albert N, Du M, Wall DP. The GapMap project: a mobile surveillance system to map diagnosed autism cases and gaps in autism services globally. Mol Autism. 2017;8:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.