Abstract

We report a case of a 52-year-old man with drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy, with post-ictal violent aggressive behaviors. Postictal violent outbursts would occur 3–4 times per year following clusters of seizures or generalized tonic–clonic convulsions. The violent outbursts were traumatizing for his family, and lead to multiple emergency department presentations as well as conflicts with police over the course of nine years. After initiation of pindolol the patient has had no episodes of violent behavior in two years despite experiencing the same frequency and severity of seizures as before pindolol. The abrupt cessation of postictal violent outbursts after introduction of pindolol in this case provides a novel management option for the treatment of postictal violence in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy and supports the importance of the beta adrenergic and potentially serotonergic systems in postictal violent behavior.

Highlights

-

•

Control of postictal violence in a patient with drug resistant temporal lobe epilepsy was achieved with pindolol.

-

•

The presumed mechanisms of pindolol on aggression are central beta adrenergic blockade and activation of serotonin receptors

-

•

Consistent control over postictal aggression and violence was achieved with pindolol despite unchanged seizure frequency and severity.

1. Case report

A 52-year-old male with a history of focal epilepsy was diagnosed at the age of 14. He has no history of febrile seizures, meningitis, encephalitis, significant head trauma or developmental delay. The patient does not have a history of violent behavior independent of his seizures.

The patient has two types of seizures. He experiences focal seizures with alteration of awareness associated with a sense of deja vu followed by an unpleasant feeling in his stomach, inability to speak and alteration in awareness with post-ictal fatigue. In addition, he experiences focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures with post-ictal fatigue lasting for several hours.

In 2008, he was noted to have an increase in seizure frequency, up to one convlsive seizure a month, and began experiencing aggressive outbursts associated with violence in the post-ictal period. At that time, he was taking valproic acid and lamotrigine for seizure management. The first aggressive outburst presented with aggressive behavior and suicidal delusions. During this event he assaulted his neighbor and threatened to harm his children. He was found to have Enterococcus faecium bacteremia and it was assumed that his aggressive behavior was related to delirium asscoiated with infection. Later that year; however, he presented to medical attention with a second event. He had experienced three seizures in one day and soon after became psychotic with delusional thinking and combative behavior which lasted for several hours. Since this time the patient continued to have episodic aggressive behavior which was consistently observed in the post-ictal period. Aggression and violence were typically observed after clusters of multiple seizures or tonic–clonic seizureswithin hours after the seizures lasting for several hours. During one episode of postictal violence, he presented to the Emergency Room. An EEG performed at this time documented a brief right temporal electrographic seizure which was not associated with any obvious ictal clinical manifestations, aside from the agitated state as the reason that the patient presented to the Emergency Room. A formal psychiatric evaluation was performed during the admission with the psychiatrist providing an axis 1 diagnosis of post-ictal psychosis.

During the following two years, his valproic acid dose and lamotrigine were increased, yet he still had inadequate seizure control. The patient was subsequently trialed on lacosamide which was not associated with any improvement in seizure control.

In 2010, he was admitted to the University of Alberta epilepsy monitoring unit for prolonged video-EEG telemetry. During that time, he demonstrated seizures associated with alteration of awareness arising from the right temporal lobe. Neuropsychological assessment demonstrated normal intelligence with intact verbal memory and mild to moderately impaired figural memory consistent with right mesial temporal lobe dysfunction. MRI of the brain did not show any obvious structural abnormality. Specifically, there was no evidence of hippocampal sclerosis or any other temporal lobe structural lesions. Based on the absence of an obvious structural lesion, intracranial EEG evaluation was suggested; however, the patient declined this investigation due to reluctance for surgical intervention.

From 2010 to 2015 carbamazepine and clobazam were introduced without any improvement in seizure control. The change in the patient's antiseizure drugs was not associated with any psychiatric symptoms. He continued to experience seizures two to three times a month despite medical therapy associated with prominent agitation and aggressive behavior leading to frequent trips to the emergency room. It was noted that his aggressive behavior was undirected and unintentional but was exacerbated when attempts were made to restrain or control him. During one of these aggressive episodes, he got into a conflict with the police assaulting an officer and was subsequently arrested.

Based on the ongoing issues with postictal aggression, he reconsidered the option of epilepsy surgery and in 2016 he was admitted to the epilepsy monitoring unit for intracranial video-EEG monitoring. Bitemporal depth electrodes were implanted with the deepest contacts targeted at the amygdala and hippocampus (Fig. 1). Interictal EEG demonstrated independent interictal epileptifrom discharges from the amygdala and hippocampus bilaterally. Ictal onset was documented independently from the deepest electrode contacts (amygdala and hippocampus) of both the right and left temporal electrodes (Fig. 2). During the 16-day intracranial video-EEG evaluation, twenty seizures were recorded. Twelve focal seizures with alteration in consciousness were recorded with focal ictal onset in the right amygdala and hippocampus and six were recorded originating from the left amygdala and hippocampus (Fig. 2). The remaining two seizures associated with focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures demonstrated bitemporal ictal EEG activity at onset without clear evidence of lateralization. With regard to seizure semiology, with the exception of ictal aphasia indicating left temporal seizures, most of the patient's recorded seizures were not associated with lateralizing ictal semiology. During one seizure, the patient had significant post-ictal agitation and pulled the depth electrodes out. Based on the demonstration of independent bitemporal ictal onset along with the lack of clear lateralization for two focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures, the patient was deemed to be a poor surgical candidate. He continued to experience extreme events with postictal rage and aggressive behavior occurring every two to three months.

Fig. 1.

Axial (A and B) and coronal (C and D) MRI (MPRAGE) demonstrating placement of bilateral depth electrodes. The deepest contacts of the anterior electrodes are located in the amygdala (C) and posterior electrodes located in the hippocampus (D).

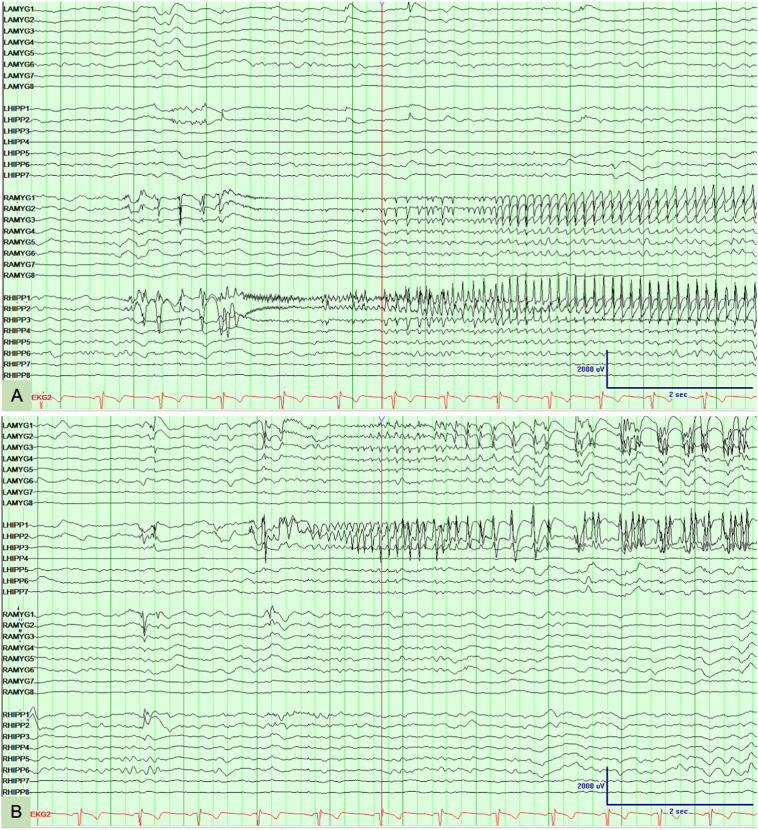

Fig. 2.

EEG depth electrode recordings. (A) Seizure onset is observed in the right amygdala (electrode contacts RAMYG1 and RAMYG2) and right hippocampus (electrode contacts RHIPP1 and RHIPP2). (B) Seizure onset is observed in the left amygdala (electrode contacts LAMYG1 and LAMYG2) and left hippocampus (LHIPP1 and LHIPP2).

As the episodes of violence continued to be a major problem, having led to charges of assaulting a police officer and marital discord, psychiatry was consulted regarding possible pharmacological approaches to manage the violent behavior independent of seizure control. Based on the successful use of beta blockers in management of violent behavior in patients with brain injury [1,2], pindolol was trialed at 10 mg twice daily dosing assuming that this patient's postictal violence could have a similar underlying pathogenesis. Following the introduction of pindolol the patient has continued to experience seizures on a monthly basis including convulsions occurring at a similar rate compared to before pindolol was started. Despite experiencing similar seizure frequency and severity, the patient has not experienced any episodes of postictal aggression and violence in over two years since pindolol was initiated.

2. Discussion

While uncommon, several studies reported violence and rage in seizure patients as a post-ictal phenomenon [3,4]. It has been described as a subacute presentation hours-to-days after seizures with patients developing aggressive behavior during post-ictal psychosis [3]. Post-ictal psychosis has been described in the literature as frank visual and auditory hallucination, paranoid delusions, thought disorder, and mood symptoms occurring after seizures [3,5]. These behaviors are generally out of character for the patient, most often occur in males and typically occur after a cluster of seizures [6]. Reported risk factors for these postictal psychoses include bilateral interictal epileptiform discharges, similar to our patient, as well as other factors such as: an aura of ictal fear, a longstanding history of epilepsy prior, and brain structural lesions [4]. Post-ictal state violence is usually non-directed, and resistive violence, such as in our patient [3].

Neural circuits for aggression have been widely described in the literature. On a structural level several regions have been described in pathophysiology of aggression, including the prefrontal cortex as well as the temporal lobes. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is where threat response analysis takes place. Thus, its dysfunction can increase aggression susceptibility through failure of risk assessment and response planning [6]. Serotonergic hypofunction in the aforementioned PFC has been associated with impulsive aggression in human studies. In the case of our patient's seizures, they originate from the temporal lobes, specifically from the amygdala and hippocampus bilaterally. The role of temporal lobe in aggression was first described when Kluver and Bucy performed bilateral temporal lobectomy in rhesus monkeys and reported enhanced aggressive behavior [7]. The amygdala and hippocampus have been implicated in ictal aggression. This can be elucidated by the role of stereotactic amygdalotomy in control of aggression in epilepsy patients with treatment-refractory aggression [8]. In addition, several animal studies described enhanced post-ictal defensive rage behavior in response to superkindling these limbic structures [9]. This concept of kindling the limbic structures in our case is a possible explanation as to why our patient only experienced aggressive events years after his initial presentation. Furthermore, metabolic studies at the time of induced aggression [10] and postictal psychosis in TLE patients [11] show excessive temporal and frontal hypermetabolism, suggesting increase activation in these areas during behavioral disturbances. This excessive cortical excitation may reflect a rebound phenomenon from a previous inhibition during the seizure [12]. This cortical hyperactivation in the setting of genetic predisposition, personality traits and emotional dysregulation may lead to postictal psychosis and behavioral outbursts.

Aggression is modulated through various neurotransmitters interplay (Table 1). GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter and it is critical in control of aggression. In adults with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) GABA-A receptor function and expression is altered [13]. How that results in aggression is less clear given the complex relationship between GABA receptors and aggression. Preclinical data suggest that pharmacologic measures enhancing GABAergic transmission inhibits aggressive behavior in mice. Human studies showed the inhibitory effect of GABA on aggression. Through direct modulation of these receptors an inverse relationship between plasma GABA levels and measures of aggression has been reported [14]. Nonetheless indirect allosteric modulation of these receptors has been shown to paradoxically induce aggression and this explains how barbiturates, alcohol, and benzodiazepines can increase aggression in some individuals [15]. Other neurotransmitters involved include serotonin, dopamine, catecholamines and glutamate. Serotonin deficiency hypothesis has been widely described in the literature based on studies reporting a negative correlation between low CSF concentration of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (a serotonin metabolite) and aggressive behavior [16]. There is evidence of the dissociation between serotonin and dopamine release in nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex in rats with aggressive behavior. This is reflected by the increased dopamine activity in nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex with reduced cortical serotonin after an aggressive encounter in rats [17]. The involvement of the dopaminergic system in aggression has been utilized pharmacologically with antipsychotic agents targeting the D2 receptors showing efficacy in aggression management [18]. Glutamate is another neurotransmitter that has been implicated in impulsive aggression with evidence suggesting a positive correlation between CSF glutamate levels and measures of impulsive aggression in healthy individuals and those with personality disorder [19]. The role of the adrenergic system in potentiating aggression is well described. Plasma norepinephrine has been associated with induced aggressiveness in healthy individuals [20].

Table 1.

The neurotransmitters implicated in aggression, and impact of various anti-aggression medications on these neurotransmitters. ⁎Indirect allosteric modulation of GABA receptors has been shown to paradoxically induce aggression.

| Neurotransmitters |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D2 | 5-HT1A | Beta adrenergic | Alpha 2 adrenergic | GABA | Glutamate | ||

| Mechanism in aggression | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓⁎ | ↑ | |

| Medications | |||||||

| Beta blockers | Pindolol | – | ↑ | ↓ | – | – | – |

| Propranolol, nadolol, alprenolol | – | – | ↓ | – | – | – | |

| First generation antipsychotics (FGA) | Haloperidol, chlorpromazine, fluphenazine | ↓↓ | – | – | – | – | – |

| Second generation antipsychotics (SGA) | Quetiapine lurasidone amisulpride | ↓ | ↑ | – | ↓ | – | – |

| Olanzapine paliperidone, iloperidone clozapine risperidone | ↓ | – | – | ↓ | – | – | |

| Ziprasidone aripiprazole, brexiprazole, cariprazine | ↓ | ↑ | – | – | – | – | |

| Benzodiazepines | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | |

These neurotransmitters provide the clue to crucial pharmacologic targets for aggression. The various neurotransmitters have been explored as targets for variety of medications described in managing aggression (Table 1). While many medications have been described, we used pindolol based on successful data from brain injury trials [1,2]. Some of its action on aggression is likely mediated by its central beta adrenoreceptor blockade. Catecholamines play a permissive role and potentially stimulate aggressive responses [21] and thus beta adrenoreceptor blockade is crucial for aggression treatment. Furthermore, pindolol is among a group of beta blockers that have been described as neuronal membrane stabilizers [22]. In turn this could silence some of the sensitive neurons and affect neuronal networks, potentially the aggression network included. Pindolol, as well as other beta blockers, has been described to have affinity for non-adrenergic centrally located serotonin 5-HT1A receptors [23] leading to increased serotonin availability, which could also potentially play a role in the successful treatment of aggression.

Pindolol has pronounced intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (ISA). Beta-blockers with intrinsic sympathomimetic activities (ISA) have partial agonist properties on beta receptors, in addition to it's beta blocking effects. Clinically the advantage of the intrinsic sympathomimetic activity use is to reduce the potential dose limiting side effects expected from the major beta receptor blockade such as bradycardia and ultimately lead to better resting sympathetic tone. Ultimately, the impact it has on reducing heart rate and forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) depends on the pretreatment sympathetic tone. Other beta-blockers that lacks these sympathomimetic properties have been described in the treatment of aggression, for instance propranolol and nadolol. This feature does not impact CNS penetration as that largely depends on lipophilicity of these drugs. As such propranolol, alprenolol, as well as pindolol cross the blood–brain barrier whereas practalol (a betBB with ISA features) has poor CNS penetration [24]. However, it is unclear if central blockade is necessarily beneficial in treating aggression [25].

First and second-generation antipsychotics have been widely used for acute treatment of aggression especially in psychiatry patients. However, their use is;,limited by a wide range of side effect [26]. First generation antipsychotics are very potent D2 receptor blockers and as such have high risk of extrapyramidal symptoms such as acute akathisia, acute dystonias and dyskinesias as well as Parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia along other side effects. Second generation antipsychotics have a lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms when compared to first generation anitpsychotics. Other reported side effects include weight gain, hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia with resultant type 2 diabetes mellitus, and worsening cardiovascular effects with elevated blood pressure, and prolongation of the QT interval on the ECG. Given this broad side effect profile their usage can be limiting [27]. Aggression in epilepsy patients in the form of post-ictal rage does necessitate a medication with high tolerability and limited side effects. Some beta-blockers have been widely described in literature in aggression management namely propranolol [29], nadolol [30], pindolol [1,2] and metoprolol [31]. Beta-blocker's can cause increase airway resistance and facilitate hypoglycemia. They may also alter lipid metabolism, blood pressure, and heart rate to variable degree. The latter effects are more commonly encountered with beta-blocer that lacks the intrinsic sympathomimetic activity [28].

3. Conclusion

In summary we demonstrate dramatic control of post-ictal violence in a patient with drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy with pindolol which provides a novel treatment option for patients with disabling postictal violence (in particular for those in whom seizures cannot be controlled with medication). The successful management of violent post-ictal behavior in our subject with pindolol suggests similar mechanisms of action could be responsible for patients with post-ictal violence and violence in the setting of traumatic brain injury with the presumed mechanisms involving the beta adrenergic and serotonergic systems.

Contributor Information

Wasan Abd Wahab, Email: abdwahab@ualberta.ca.

Kathy Collinson, Email: kc21@ualberta.ca.

Donald W Gross, Email: donald.gross@ualberta.ca.

References

- 1.Greendyke R.M., Kanter D.R. Therapeutic effects of pindolol on behavioral disturbances associated with organic brain disease: a double blind study. . 1986;47:423–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greendyke R.M., Berkner J.P., Webster J.C., Gulya A. Treatment of behavioral problems with pindolol. 1989;30:161–165. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(89)72297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marsh L., Krauss G.L. Aggression and violence in patients with epilepsy. 2000;1:160–168. doi: 10.1006/ebeh.2000.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leutmezer F., Podreka I., Asenbaum S. Postictal psychosis in temporal lobe epilepsy. 2003;44:582–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.32802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerard M.E., Spitz M.C., Towbin J.A., Shantz D. Subacute postictal aggression. 1998;50:384–388. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosell D.R., Siever L.J. Neurobiology of aggression and violence. 2008;165:429–442. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kluver H., Bucy P. Preliminary analysis of functions of the temporal lobes of monkeys. 1939;42:979–1000. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.4.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mpakopoulou M., Gatos H., Brotis A., Paterakis K.N., Fountas K.N. Stereotactic amygdalotomy in the management of severe aggressive behavioral disorders. 2008;25:E6. doi: 10.3171/FOC/2008/25/7/E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andy O.J., Velamati S. Limbic system seizures and aggressive behavior (superkindling effects) 1978;13:251. doi: 10.1007/BF03002262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dierckx Rudi A.J.O. 2014. PET and SPECT in psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leutmezer F., Podreka I., Asenbaum S. Postictal psychosis in temporal lobe epilepsy. 2003;44:582–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.32802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devinsky O. Postictal psychosis: common, dangerous, and treatable. 2008;8:31–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2008.00227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loup F., Wieser H., Yonekawa Y., Aguzzi A., Fritschy J. Selective alterations in GABAA receptor subtypes in human temporal lobe epilepsy. 2000;20:5401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05401.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bjork J.M., Moeller F.G., Kramer G.L. Plasma GABA levels correlate with aggressiveness in relatives of patients with unipolar depressive disorder. 2001;101:131–136. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miczek K., Fish E., de Bold J., de Almeida R. Social and neural determinants of aggressive behavior: pharmacotherapeutic targets at serotonin, dopamine and γ-aminobutyric acid systems. 2002;163:434–458. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown G.L., Ebert M.H., Gover P.F. 1982. Aggression in humans correlates with cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites; pp. 131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Erp Annemoon M.M., Miczek K.A. Aggressive behavior, increased accumbal dopamine, and decreased cortical serotonin in rats. 2000;20:9320–9325. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09320.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brizer D.A. Psychopharmacology and the management of violent patients. 1988;11:551–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coccaro E.F., Lee R., Vezina P. Cerebrospinal fluid glutamate concentration correlates with impulsive aggression in human subjects. 2013;47:1247–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerra G., Zaimovic A., Avanzini P. Neurotransmitter-neuroendocrine responses to experimentally induced aggression in humans: influence of personality variable. 1997;66:33–43. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(96)02965-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miczek K.A., Fish E.W., Monoamines G.A.B.A. glutamate, and aggression. In: Nelson R.J., editor. Biology of aggression. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2005. pp. 114–149. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koella W.P. Vol. 28. 1985. CNS-related (side-)effects of ?-blockers with special reference to mechanisms of action; pp. 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caspi N., Modai I., Barak P. vol. 16. 2001. Pindolol augmentation in aggressive schizophrenic patients: A double-blind crossover randomized study; pp. 111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Middlemiss D.N., Buxton D.A., Greenwood D.T. vol. 12. 1981. Beta-adrenoceptor antagonists in psychiatry and neurology; pp. 419–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alpert M., Allan E.R., Citrome L., Laury G., Sison C., Sudilovsky A. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adjunctive nadolol in the management of violent psychiatric patients. 1990;26(3):367–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mauri M.C., Paletta S., Maffini M. Clinical pharmacology of atypical antipsychotics: an update. 2014;13:1163–1191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Schalkwyk G.I., Beyer C., Johnson J., Dealb M., Blocha M. 2018. Antipsychotics for aggression in adults: A meta-analysis; p. 81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aellig W. Pindolol a beta-adrenoceptor blocking drug with partial agonist activity: clinical pharmacological considerations. 1982;13:187S–192S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1982.tb01909.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greendyke R.M., Kanter D.R., Schuster D.B., Verstreate S., Wootton J. Propranolol treatment of assaultive patients with organic brain disease. A double-blind crossover, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1986;174(5):290–294. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198605000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connor D.F., Ozbayrak K.R., Benjamin S., Ma Y., Fletcher K.E. A pilot study of nadolol for overt aggression in developmentally delayed individuals. 1997;36:826–834. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kastner T.A., Burlingham K., Friedman D.L. Metoprolol for aggressive behavior in persons with mental retardation. Am Fam Physician. 1990;42:1585–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]