Abstract

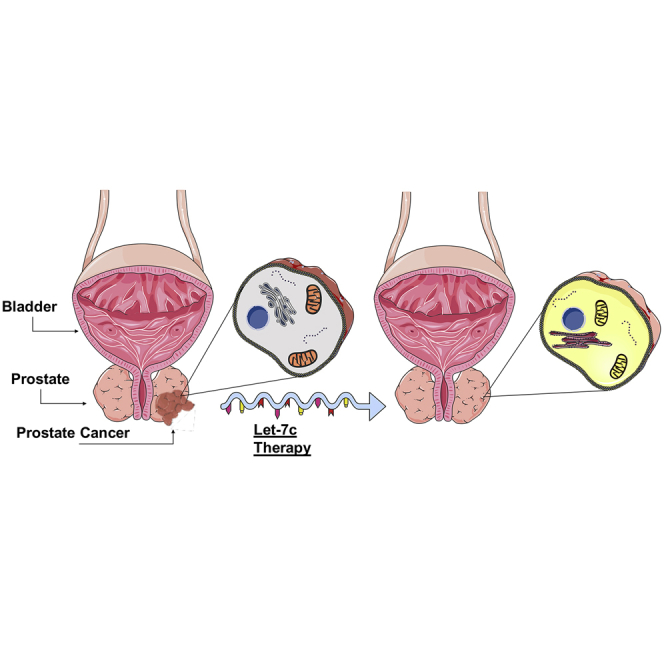

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide and often presents with aberrant microRNA (miRNA) expression. Identifying and understanding the unique expression profiles could aid in the detection and treatment of this disease. This review aims to identify miRNAs as potential therapeutic targets for PCa. Three bio-informatic searches were conducted to identify miRNAs that are reportedly implicated in the pathogenesis of PCa. Only hsa-Lethal-7 (let-7c), recognized for its role in PCa pathogenesis, was common to all three databases. Three further database searches were conducted to identify known targets of hsa-let-7c. Four targets were identified, HMGA2, c-Myc (MYC), TRAIL, and CASP3. An extensive review of the literature was undertaken to assess the role of hsa-let-7c in the progression of other malignancies and to evaluate its potential as a therapeutic target for PCa. The heterogeneous nature of cancer makes it logical to develop mechanisms by which the treatment of malignancies is tailored to an individual, harnessing specific knowledge of the underlying biology of the disease. Resetting cellular miRNA levels is an exciting prospect that will allow this ambition to be realized.

Keywords: CASP3, Let-7, microRNA, prostate cancer, gene therapy

Graphical Abstract

Main Text

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the most prominent causes of cancer-related mortality in developed countries and accounts for around 8% of all malignancies, affecting ∼15% of the male population.1, 2, 3 In the United Kingdom, PCa is the most common cancer in males, accounting for 26% of all new diagnoses.4 It is characterized by slow growth, and the majority of patients survive >10 years, but there is also a substantial reduction in quality of life.2

The prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was first discovered in 1979 and has subsequently developed into a valuable marker not only in the diagnosis of the disease but also in monitoring treatment response and residual disease.5,6 Screening for atypical levels of PSA within the serum has allowed for early detection of this disease and has led to a 20% decrease in mortality.7 However, it is also associated with both over-diagnosis and under-diagnosis, as well as over-treatment of men with low-risk disease.7,8

The European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines for the treatment of PCa include non-targeted and invasive treatments such as radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy, hormonal therapy, and chemotherapy.9 Taxane-based therapeutics such as docetaxel have proved effective; however, constant efforts are made to overcome limitations of water insolubility10 and drug resistance.11 In 10%–15% of patients, the cancer presents as an aggressive form that is characterized by metastases in the lymphatic system and bone sites.12 Androgen deprivation is the standard clinical therapy for advanced PCa and is employed to hinder further growth.2 Androgen deprivation therapy is effective for 1–2 years, after which the disease becomes resistant and is known as castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC).2 For those with CRPC, the standard of care is palliative.2

It is therefore crucial to identify novel, non-invasive, potent therapies to overcome the limitations of the current standard of care.13 As PCa is a heterogeneous disease, it is rational to consider utilizing molecular markers that can be both predictive and prognostic, as well as conferring stage-dependent, customized treatments.14 This review, therefore, will explore the role of miRNAs in prostate cancer with a focus on Lethal-7c (Let-7c), which was identified through the literature and computational analysis as being highly downregulated in PCa. Further computational analysis will explore the identification of let-7c target genes and use therefore as a biomarker, as well as a therapeutic and prognostic agent.

MiRNA Biogenesis

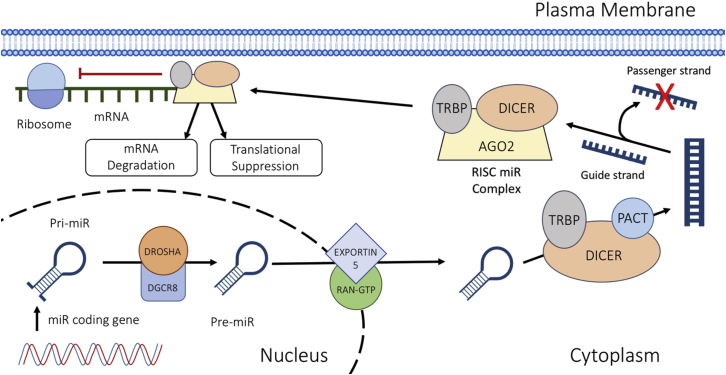

MiRNAs are a group of highly conserved, non-coding RNAs that are approximately 18–22 nt in length.1,15 They operate post-transcriptionally by attaching to the 3′ UTR of mRNAs via complementary base pairing, to instigate mRNA degradation and/or translational suppression.1 Various cellular processes involve the action of miRNAs, including cellular proliferation and apoptosis.16 The process of miRNA maturation and mechanisms of action are detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

miRNA Biogenesis

The miRNA is translated by RNA polymerase II to form a pri-miRNA. The RNase III enzyme DROSHA cuts the single-stranded RNA/double-stranded RNA (ssRNA/dsRNA) junction to create a pre-miRNA. The pre-miRNA is transported to the cytoplasm via EXPORTIN 5/RAN-GTP. It then undergoes modification by DICER. The guide strand is then incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), where it leads the complex toward target mRNA transcripts.

MiRs in Cancer

The human genome encodes for more than 1,917 miRNAs that can target multiple genes (http://www.mirbase.org/).17 Around 40% of miRNA genes are either intronic or exonic and are situated within coding mRNAs.18 Intergenic miRNAs are positioned in non-coding regions and are transcribed by unidentified promoters.19 Around 50% of these genes are located in chromosomal sites that are susceptible to rearrangement or deletion in cancer.14,18,20 Mutations in the stem region of miRNAs may affect the processing abilities of DGCR8 and DICER. However, mutations that occur in the loop region of pre-miRNAs do not affect processing capabilities.20 Hanahan and Weinberg21 suggested 10 essential modifications that occur within a cell’s physiology that ultimately determine malignant growth: self-sufficiency in growth signals, insensitivity to growth suppressors, evasion of apoptosis, unlimited replicative potential, persistent angiogenesis, tissue invasion and metastasis, avoidance of immune destruction, genomic instability and mutation, deregulated cellular energetics, and tumor-promoting inflammation. Within all these processes, miRNA dysregulation can lead to advancing of the disease.

Novel miRNA targets are now being identified that may have a role in driving the oncogenic processes of PCa.22 In identifying miRNAs involved in PCa pathogenesis, light may be shed upon pathogenic processes such as cellular proliferation, epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), and the emergence of androgen independence.3 Specific miRNAs have also been implicated in the development of chemoresistance in a number of malignancies, where modulation resulted in enhanced therapeutic sensitivity.23,24 In PCa specifically, Liu et al.25 showed that miR-34a plays a role in chemosensitivity to paclitaxel. This is achieved through regulation of the JAG1/Notch1 axis. The authors postulated therefore that miR-34a therapy could be used to overcome chemoresistance in PCa.

MiRNA Expression in Prostate Cancer

Significant advancement has been made in the identification of miRNA target genes in cancer through validation using wet-lab experimentation. A literature search was performed using the miRCancer, Web of Science, and PubMed repositories for miRNAs associated with PCa. Table 1 presents a selection of aberrantly expressed PCa miRNAs, alongside associated targets identified from the literature.

Table 1.

miRNA Expression in PCa Alongside Respective mRNA Target Transcripts Identified in the Literature

| PCa miR | Expression (PCa versus Control) | Target | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-let-7c | down | MYC, RAS, HMGA2 | 47,48 |

| hsa-miR-21 | up | MARKS, PDCD4, TPM1 | 83 |

| hsa-miR-32 | up | BTG2 | 84 |

| hsa-miR-34a | down | CD44, Cyclin D1, CDK4, CDK6, c-MET, ZEB1 | 85,86 |

| hsa-miR-96 | up | RAD51, REV1 | 87 |

| hsa-miR-100 | down | MYC, Oct4, KLF4 | 88 |

| hsa-miR-105 | down | CDK6 | 89 |

| hsa-miR-124 | down | TLN1 | 90 |

| hsa-miR-125b | up | EIF4EBP1, p14ARF | 91 |

| hsa-miR-130b | down | MMP2 | 92 |

| hsa-miR-133b | down | EGFR | 93 |

| hsa-miR-141 | up | SHP | 94 |

| hsa-miR-143 | down | GOLM1 | 95 |

| hsa-miR-146a | down | Rac1 | 96 |

| hsa-miR-153 | up | PTEN, FOXO1 | 97 |

| hsa-miR-154 | down | CCND2 | 98 |

| hsa-miR-155 | down | STAT3 | 99 |

| hsa-miR-181b | up | MLK2 | 100 |

| hsa-miR-181c | up | DAX-1 | 101 |

| hsa-miR-181d | up | DAX-1 | 101 |

| hsa-miR-182 | up | NDRG1 | 102 |

| hsa-miR-183 | up | DKK-3, SMAD4 | 103 |

| hsa-miR-187 | down | ALDH1A3 | 104 |

| hsa-miR-200b | down | ZEB1, ZEB2 | 105 |

MARKS, myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; NDRG1, N-myc downstream regulated gene 1; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; SHP, small heterodimer partner; TLN1, talin 1; TPM1, tropomyosin 1; ZEB, zinc-finger E-box binding homeobox.

Comparison of Prostate Cancer-Associated MiRNAs

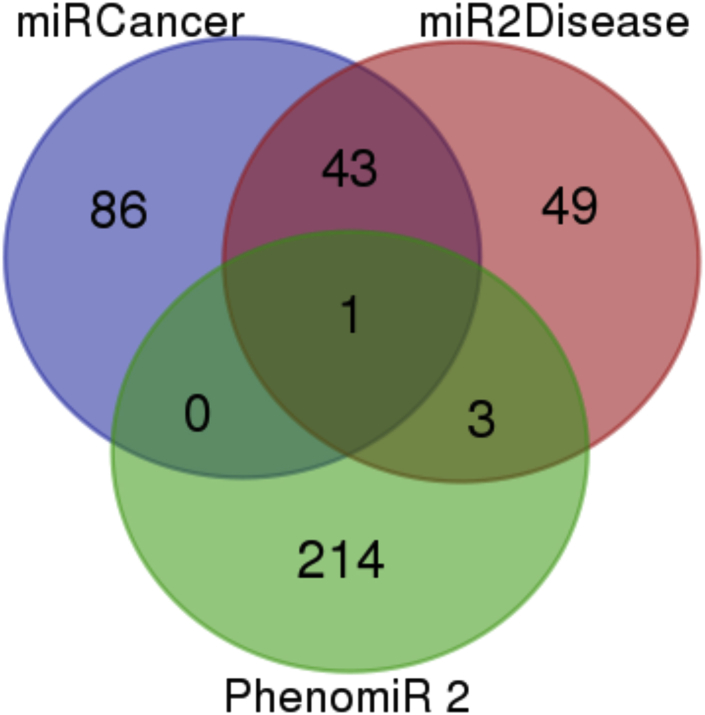

Computational methods for miRNA gene target identification are an auspicious tool to aid in building a complete picture of miRNA networks.26 With a single miRNA having the potential to regulate such a wide variety of genes, it is often unrealistic to depend solely on wet-lab experimentation. Therefore, dry-lab approaches can be utilized as low-cost alternatives for the identification of miRNA in disease.27 Three database searches were compared to identify PCa-associated miRNAs that were common to all. The three miRNA databases used were miRCancer, mir2Disease, and PhenomiR2.0.28, 29, 30 Results of this search are included in Figure 2 and Table 2. Only hsa-let-7c was common to all three databases.

Figure 2.

A Venn Diagram Displaying Database Analysis Results Using miRCancer, miR2Disease, and PhenomiR2 Databases

One target, hsa-let-7c, was common to all three databases.

Table 2.

Database Analysis Results Using Predictive Databases

| Database | Shared miRNAs | Total |

|---|---|---|

| miRCancer miR2Disease PhenomiR 2.0 | hsa-let-7c | 1 |

| miRCancer miR2Disease | hsa-miR-146a; hsa-miR-16; hsa-miR-125b | 43 |

| hsa-miR-22; hsa-miR-503; hsa-miR-222 | ||

| hsa-miR-221; hsa-miR-195; hsa-miR-96 | ||

| hsa-miR-27a; hsa-miR-23b; hsa-miR-101 | ||

| hsa-miR-31; hsa-miR-143; hsa-miR-199b | ||

| hsa-miR-330; hsa-miR-449a; hsa-miR-223 | ||

| hsa-miR-141; hsa-miR-194; hsa-miR-30c | ||

| hsa-miR-224; hsa-miR-205; hsa-miR-103 | ||

| hsa-miR-24; hsa-miR-100; hsa-miR-182 | ||

| hsa-miR-30b; hsa-miR-345; hsa-miR-25 | ||

| hsa-miR-23a; hsa-miR-181b; hsa-miR-21 | ||

| hsa-miR-15a; hsa-miR-20a; hsa-miR-183 | ||

| hsa-miR-145; hsa-miR-26b; hsa-miR-497 | ||

| hsa-miR-218; hsa-miR-26a; hsa-miR-34a | ||

| hsa-miR-29b | ||

| mir2Disease PhenomiR 2.0 | hsa-let-7d; hsa-let-7g; hsa-let-7b | 3 |

The let-7 Family of MiRNAs in Cancer

Lethal-7 (let-7) was the second family of miRNAs discovered in Caenorhabditis elegans and was subsequently the first discovered in humans.31 This family encompasses 13 members (let-7-a1, let-7a-2, let-7a-3, let-7b, let-7c, let-7d, let-7e, let-7f-1, let-7f-2, let-7g, let-7i, miR-98, and miR-202) that are spread across nine chromosomes.31 Each of these members represents a different isoform of the let-7 gene.32 These highly conserved miRNAs have been implicated as mediators of cellular differentiation throughout the development of different species, from nematodes to Homo sapiens.31

The let-7 genes are commonly found in regions that are altered or deleted in human malignancies, signifying a potential role as tumor suppressors.33 Lin28A and Lin28B, two closely related RNA binding oncogenes that have a prominent role in suppressing let-7 biogenesis, are upregulated in >15% of malignancies.34 Lin28 attaches to the hairpin precursor of pri-let-7 and pre-let-7, and blocks DROSHA-mediated processing of pri-let-7.35 This appears to be very selective for the let-7 family because this phenomenon is not observed in other miRNAs.35

Interestingly, Zhou et al.36 validated claims of significantly higher levels of Lin28B in lung cancer tissues and established a link between miR-203, Lin28B, and let-7. The authors showed that overexpression of miR-203 was followed by significant upregulation of let-7. Moreover, apoptosis was promoted as a result of miR-203-induced suppression of Lin28B and let-7 biogenesis.36

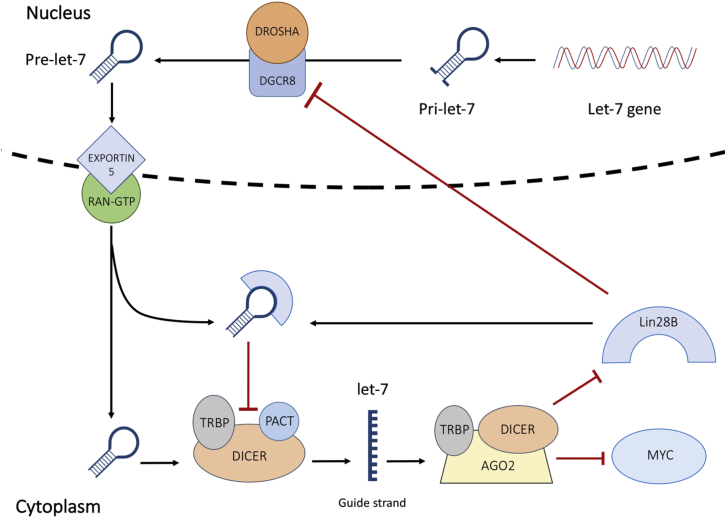

Targeting Lin28B in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) inhibited proliferation and induced cell-cycle arrest.37 Conversely, overexpression of Lin28B stimulated proliferation in AML.37 Lin28B was also found to be correlated with MYC, a prominent driver of multiple myeloma (MM) progression.38 Manier et al. demonstrated that MYC expression is under the control of the Lin28B/let-7 axis, and that induced overexpression of let-7 repressed tumor growth by mediating the expression of MYC. Chang et al.39 then demonstrated that MYC prompts Lin28B expression in many human and mouse tumors (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic Diagram of the Lin28B/MYC/Let-7 Interaction

Let-7 maturity blocks the transcription of Lin28B and MYC. In the presence of Lin28B, pri-let-7 and pre-let-7 processing is inhibited. Repression of mature let-7 triggers an upsurge in MYC and Lin28B expression.

The Role of let-7 in Cancer Stem Cells

Embryonic stem cells continually replicate and divide, differentiating into organs under the guidance of transcription factors at certain points in time.40 Conversely, adult stem cells exist in a passive state, waiting for environmental cues such as tissue damage before the activity is stimulated.40 Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are a rare population that have similar characteristics to regular stem cells, yet can to resist treatment and act as a source of tumor recurrence.41

Prostate CSCs exhibit aberrant gene expression patterns and can be used in identification and targeting.40,42 Although surgical resection is a viable treatment option in PCa, it does not ensure that the disease has been eradicated, because thousands of cells may have escaped into the bloodstream as the lesion ruptures the basal lamina.43 Any CSCs within this population have the capabilities of interacting with other microenvironments to safeguard survival and propagate recurring neoplasms.43

The survival of CSCs may be dependent on post-transcriptional gene regulation, including that carried out by let-7.44 Lin28A and Lin28B are highly expressed within stem cells, where they suppress let-7 biogenesis in embryonic stem cells and CSCs to preserve stem cell characteristics.34,38,44 Lin28 suppression and subsequently let-7 upregulation are correlated with a less aggressive phenotype in PCa.45 Acquired resistance to a number of taxanes and platinum-based cancer therapeutics is also a product of the deregulated Lin28/let-7 axis.34 Not surprisingly, Lin28 expression correlates to a poor prognosis.34 Albino et al.46 forced the overexpression of Lin28A and Lin28B in RWPE-1 cells (normal prostate epithelial cell line). They found significantly higher colony formation in soft agar, suggesting that both Lin28A and Lin28B endorsed tumorigenic and CSC activity.46

The Role of let-7c in Prostate Cancer

Let-7c functions as a tumor suppressor and is downregulated in PCa.47 Downregulation of let-7c has a positive effect on cellular proliferation and anchorage-independent growth of PCa cells in vitro, whereas overexpression of let-7c induced the opposite effect.47 The androgen receptor (AR) plays a crucial role in PCa pathogenesis and the progression to castrate resistance following androgen deprivation therapy.48 Let-7c was shown to regulate AR transcription via MYC.48 PCa specimens reveal that AR expression is positively correlated to Lin28 expression and negatively correlated to let-7c expression.48 Interestingly, let-7c suppression improved the ability of androgen-sensitive PCa cells to grow in an androgen-deprived environment in vitro.47 Table 3 summarizes let-7 expression profiles in a host of malignancies.

Table 3.

A Summary of the let-7 Expression Profile in Various Malignancies

| Cancer | Cell Line Tested | Expression | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | MCF10A-HER2/3, BT474, SKBR3, MCF10A-NeuNT, SUM159, SUM1315 | ↑ SHP2 | 106 |

| ↑ ZEB1 | |||

| ↑ MYC | |||

| ↑ Lin28B | |||

| ↑ RAS | |||

| ↓ Let-7 | |||

| Lung | NSCLC | ↑ Lin28B | 107 |

| ↓ Let-7 | |||

| Multiple myeloma | MOLP-8, KMS12BM, RPMI8226, KMM-1 | ↑ Lin28B | 38 |

| ↑ MYC | |||

| ↓ Let-7 | |||

| Neuroblastoma | BE(2)-C, SMS-KCNR, CHLA90 | ↑ Lin28B | 108 |

| ↑ MYCN | |||

| ↓ Let-7 | |||

| Oral | OSCC | ↑ Lin28B | 109 |

| ↑ ARID3B | |||

| ↑ HMGA2 | |||

| ↑ OCT4 | |||

| ↑ SOX2 | |||

| ↓ Let-7 | |||

| Ovarian | ES-2 | ↑ Lin28 | 110 |

| ↑ IGF2BP1 | |||

| ↑ HMGA2 | |||

| ↓ Let-7 | |||

| Pancreatic | PDAC | ↑ Lin28B | 111 |

| ↓ SIRT6 | |||

| ↓ Let-7 | |||

| Prostate | PrEC, RWPE-1, LNCaP, DU145, PC3 | ↑ Lin28A | 46 |

| ↑ Lin28B | |||

| ↓ ESE3/EHF | |||

| ↓ Let-7 |

ARID3B, AT-rich interactive domain 3B; IGF2BP1, insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung carcinoma; OSCC, oral squamous cell carcinoma; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; SIRT6, sirtuin 6.

Let-7c Targets

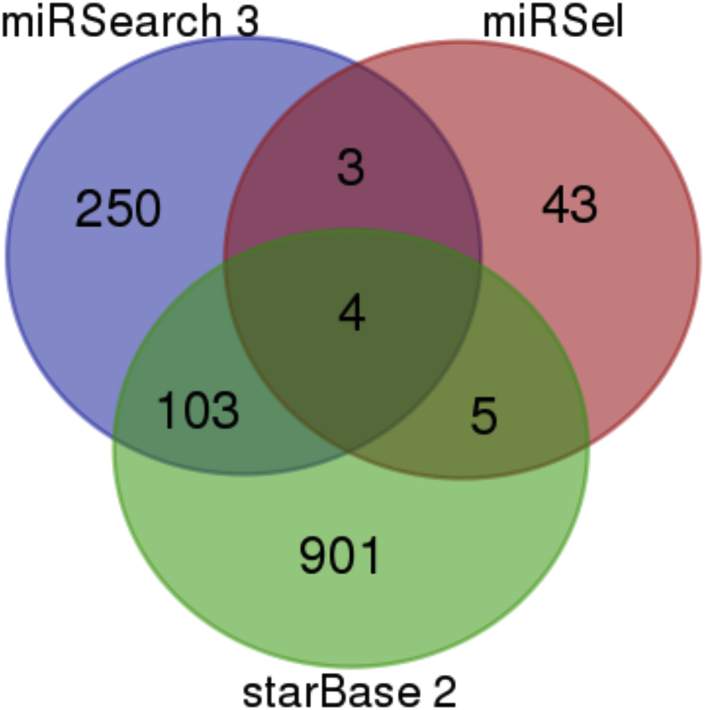

A computational search was conducted to identify let-7c target genes that are common to three databases: miRSearch 3.0, miRSel (validated and predicted), and starBase 2.0 (predicted).49, 50, 51 The results of this search are included in Figure 4 and Table 4. The four hsa-let-7c targets common to all three databases include HMGA2, MYC, TNFSF10, and CASP3.

Figure 4.

A Venn Diagram Displaying let-7c Database Targets Using miRSearch 3, miRSel, and starBase 2 Databases

In total, four hsa-let-7c targets were identified as being common to all three databases.

Table 4.

Hsa-let-7c Common Targets from Database Results

| Database Comparison | Target Genes Identified | Total |

|---|---|---|

| miRSearch 3.0 miRSel starBase 2.0 | HMGA2; MYC; TNFSF10; CASP3 | 4 |

| miRSearch 3.0 miRSel | BCL2; BCL2L1; TRIM71 | 3 |

| miRSearch 3.0 starBase 2.0 | VPS33A; PRTG; QARS; PXT1; BTN2A1; TAF9B; IGF2BP3; RNF170; C8orf58; CEP135; DDX19B; ABL2; YOD1; GDF6; DPH3; C14orf28; SMUG1; FAS; ZNF232; RICTOR; CLP1; COIL; DCUN1D3; ZCCHC9; IFT80; NRAS; ZNF275; ARHGAP28; CDK6; LIN28B; SUB1; ARPP19; SCD; ZNF792; MAP4K3; TBKBP1; TGFBR1; ZBTB26; ACVR1C; DNA2; E2F5; ADRB2; SOCS4; AHCTF1; PPAPDC1B; POLQ; MAP3K1; ABT1; PARS2; MBD2; NPHP3; DOT1L; PEX11B; POLR2D; CCR7; NAP1L1; USP38; CLDN12; STX3; DDX19A; FAM103A1; DVL3; DUSP3; MAPK6; RNFT1; CD80; SENP2; SFT2D3; CCNJ; HAND1; DOK3; RRM2; EIF3J; ABCC5; C15orf39; ZFYVE26; XRN1; ERCC6; ARID3B; MRS2; CDV3; SEMA4F; GJC1; CYB561D1; CDC34; USP12; C9orf40; CTPS2; PCTP; BRF2; TMEM2; TNFSF9; KCTD21; GALNT1; BCAT1; PBX2; NEK3; RGPD6; C18orf21; PDE12; LIPT2; CDC25A; KHNYN | 103 |

| miRSel starBase 2.0 | MECP2; DHDDS; VIM; CDK4; PPARA | 5 |

HMGA2

High mobility group, A2 (HMGA2) is a long-established target of the let-7 family.52 The 3′ UTR of HMGA2 contains many potential let-7 binding sites and is suppressed during let-7 upregulation in embryogenesis.31 According to the reversed embryogenesis model, HMGA2 levels should be primarily upregulated in tumorigenesis.53 HMGA2 expression in PCa correlates with this model because the HMGA2 expression was found to be significantly higher in PCa tissues than in normal prostate tissues.54

Cancer cells share three main characteristics with embryonic cells: proliferation, invasion, and immortality.53 Epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a mechanism that occurs during embryonic development that allows for tissue morphogenesis.55 However, evidence now suggests that EMT arises in malignant cells via signals from the tumor microenvironment, leading to metastatic potential.55 During EMT, epithelial cells lose characteristic features and adopt features that are typical of mesenchymal cells.56 Epithelial (E)-cadherin is a distinctive feature of epithelial cells, with expression lost during the transition to a mesenchymal phenotype.56 Watanabe et al.57 highlighted the responsibility of HMGA2 in reversibly maintaining the EMT process in pancreatic cancer. An inverse correlation exists between HMGA2 and E-cadherin expression because HMGA2 directly activates SNAIL, a transcriptional repressor of E-cadherin.57 Suppression of HMGA2 in PC3 and DU145 PCa cells caused a marked reduction in proliferation, cell migration, and invasion, as well as diminishing the occurrence of EMT in both cell lines.58

MYC

There are three members in the Myc family, c-Myc (MYC), n-Myc (MYCN), and l-Myc (MYCL).59 MYC is a proto-oncogene that encodes for a transcription factor that mediates cellular proliferation, growth, and apoptosis.60 Aberrant expression of MYC is a common feature of cancer in humans.60 MYC is frequently overexpressed in PCa61 through the activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways.62 MYC suppression through JMJD1A knockdown in PCa cells inhibited cell proliferation and cell survival.63

The role of MYCN has been reported alongside HMGA2, Lin28B, and Let-7 in high-grade serous ovarian cancer.64 Helland et al.64 verified that overexpression of MYCN was correlated with amplification of Lin28B and HMGA2, and inversely correlated with let-7 expression. MYC is also associated with the strong angiogenic promoter, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).65 Zhao et al.65 demonstrated that VEGF drives the renewal of lung and breast CSCs via upregulation of MYC and SOX2. VEGF was found to trigger STAT3-mediated MYC expression and was ultimately associated with a poor prognostic outcome.65

TNFSF10/Apo2L/TRAIL

The tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TNFSF10/Apo2L/TRAIL) can trigger apoptosis when bound to receptors (TRAIL-R1/R2), preferentially targeting malignant cells.66 Gang et al.67 demonstrated the insensitivity of PC3 cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Moreover, Anees et al.68 discovered that 99.5% of 200 PCa tissue samples exhibited either reduced expression of pro-apoptotic TRAIL receptors, increased FLICE inhibitory protein expression, or both. Elevated TRAIL presence in the tumor microenvironment was also positively correlated with recurrence-free survival in PCa tissues.68

However, TRAIL/TRAIL-R has also been shown to promote metastasis through activation of PI3K and Rac1.69 Intriguingly, Haselmann et al.66 discovered that TRAIL-R2 interacted with DROSHA and DGCR8 within the nuclei of pancreatic tumor cells. Upon investigation, they found that TRAIL-R2 inhibited DROSHA/DGCR8 activity, and subsequent knockdown of TRAIL-2 resulted in an upregulation of pri-let-7 processing and levels of mature let-7.66 Mature let-7 levels were inversely correlated with Lin28B and HMGA2 levels, and thus cellular proliferation was inhibited.66 Hartwig et al.69 revealed how TRAIL is responsible for cytokine secretion in TRAIL-resistant tumor cells. CCL2 is a cytokine that promotes aggregation of the tumor-supportive M2 macrophage phenotype in the tumor microenvironment.69 CCL2 and TRAIL presence correlated with M2 markers in lung adenocarcinoma patients.69 This evidence suggests that TRAIL also has a cancer-promoting role in the tumor microenvironment.

Caspase-3

Caspase-3 (CASP3) is part of the caspase family, with a prominent role in mediating apoptosis upon cellular exposure to cytotoxic drugs and radiotherapy.70 A large cohort study (N = 1,902) performed by Pu et al.71 showed that there is a significant association between CASP3 expression and breast cancer-specific survival in breast cancer patients. An interesting study by Wang et al.72 demonstrated that T47D breast cancer cells highly expressing Lin28B were much more resistant to radiation. As radiotherapy is known to trigger apoptosis in breast cancer, Wang et al.72 investigated this effect on SK-BR-3 cells, discovering that stable Lin28B expression caused a significant reduction in radiation-induced apoptosis compared with that of the control. Furthermore, they noted lower levels of CASP3 activation in SK-BR-3 cells with stable Lin28B expression, signifying Lin28B as a mediator of the CASP3 apoptotic pathway.72

CASP3 expression was found to be significantly lower in moderately and poorly differentiated prostatic tumors when compared with well-differentiated prostate adenocarcinomas and normal prostate specimens.73 Furthermore, pro-CASP3 and cleaved CASP3 expression were assessed in radical prostatectomy samples as prognostic indicators.74 Patients who presented with negative pro-CASP3 and cleaved CASP3 expression had a significantly worse prognosis.74 Therefore, pro-CASP3 and cleaved CASP3 expression may serve to identify PCa patients at risk for disease progression.74

However, recent evidence supports the idea that CASP3 plays a role in tumor angiogenesis and tumor relapse. Zhou et al.70 presented evidence showing that CASP3 knockout (CASP3KO) HCT116 colon cancer cells were significantly less invasive and exhibited increased sensitivity to radiation and the chemotherapeutic agent, mitomycin C. Furthermore, CASP3KO HCT116 cells showed reduced EMT characteristics by displaying higher E-cadherin expression and reduced SNAIL and ZEB1 expression compared with the control.70 Figure 5 illustrates let-7 targets and the potential implications of target upregulation.

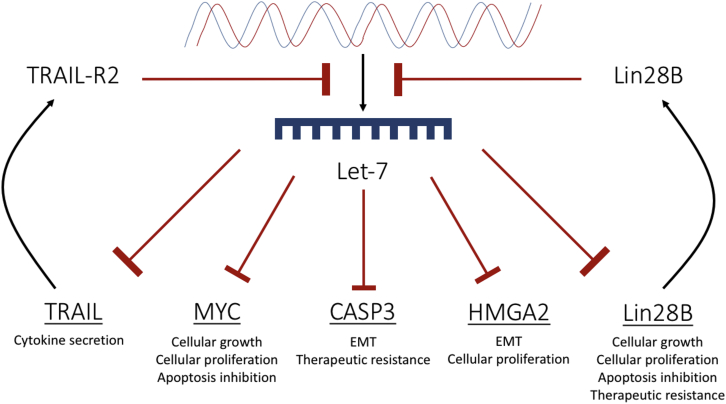

Figure 5.

A Schematic Diagram Showing Targets of let-7 in Cancer

Let-7 causes translational suppression of HMGA2, MYC, TRAIL, CASP3, and Lin28B. Blockage of let-7 biogenesis will consequently result in an upregulation of each of these targets. Lin28B and TRAIL-receptor 2 further contribute to the inhibition of let-7 biogenesis. Collectively, upregulation of these targets results in a proliferative, invasive, and therapeutically resistant phenotype.

Modes of Let-7c Upregulation

The introduction of miRNA into tissues can come in many forms, for example, plasmid DNA that encodes for specific miRNA, or indeed antagomirs could be utilized for silencing expression.75 For this, a plethora of delivery systems for genetic cargo is currently being used in research, of which viral vectors are most efficient.76 For example, Nadiminty et al.47 utilized a lentivirus system that encoded for a GFP-tagged let-7c precursor to explore its potential in PCa treatment. The treatment’s efficacy was tested using xenografts in nude male mice injected subcutaneously with either C4-2B, PC456C, or DU145 cells. Once tumors had reached a size of 0.5 cm3, the mice were randomized into two groups. The experimental mice were treated with a single intratumoral injection (1 × 107 ifu) of let-7c encoding lentivirus, and control mice received a single injection of GFP encoding lentivirus. After 3 weeks the mice were sacrificed, and the tumors were excised for RNA isolation, to assess the levels of let-7c. It was seen that in all xenograft models injected with let-7c encoding lentivirus, a significant upregulation in gene expression (*p < 0.05) was observed. Indeed, the mice treated with let-7c encoding lentivirus showed significant tumor growth inhibition in all cell line groups compared with the control. These findings propose that overexpression of let-7c can suppress PCa growth, making it an attractive therapeutic option to explore.47 Yet, there are trepidations around the use of viral vectors as gene carriers due to toxicity, mutagenesis, and the hampered capacity for genetic cargo.76 There are many examples of non-viral vectors that can be utilized for these applications, including cationic polymers, peptides, and liposomes, all of which exhibit the skill to package and deliver genetic cargo to the nucleus of cells.77 Liposomes are made of a membrane composed of lipids, in which nucleic acids can be encapsulated. Liposomes come in three forms: cationic, neutral, and anionic. Cationic liposomes are the most frequently used form because of this heightened interaction with cell membranes.78 Piao et al.79 utilized a cationic liposome system for the delivery of pre-miR-107 in the treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. The miRNA-based treatment was delivered systemically in 8-week-old female athymic nude mice that had been implanted with human tongue squamous cell carcinoma (CAL27) cells. The systemic delivery of the miRNA-based treatment resulted in a significant (*p < 0.05) stunt in tumor growth compared with the pre-miRNA-control group.79 For cancer therapy, the ideal non-viral delivery system must be non-toxic and non-immunogenic, so as not to compromise healthy tissue in the process.

Conclusions and Future Prospects

PCa is characterized by aberrant expression of several tumor suppressor or oncogenic miRNAs.47 These miRNAs have the potential to serve as biomarkers for PCa identification,80 as well as therapeutic targets for the treatment of PCa. MiRNA also has the potential to serve as a prognostic indicator in PCa.81 This technology may be utilized in the era of personalized medicine for patient stratification and treatment.

Over the past number of years, miRNA expression has been profiled in a range of malignancies. Future experimental studies will shed light on the function and the contributory status of each miRNA in PCa pathogenesis. Each miRNA acts on and regulates many target genes. Aberrant and seemingly chaotic gene expression may be a result of dysregulation in only a very small number of miRNAs. Each aberrantly expressed miRNA presents a potential therapeutic target that can be used as a tool to normalize target gene expression. By normalizing gene expression, the expectation is that the cellular characteristics of malignancy can be halted or even reversed. Studies have shown that dysregulated miRNA expression leads to cellular proliferation, EMT, and therapeutic insensitivity, which can be abrogated.

This review has identified members of the let-7 family, in particular, let-7c, as possible therapeutic targets in PCa. It was concluded that let-7c is typically downregulated in PCa, and targets include HMGA2, MYC, TNFSF10 (TRAIL), and CASP3. Therefore, let-7c suppression may lead to enhanced metastatic capabilities and a heightened stem-like tumor cell population.

Rather than attempting to highlight and treat each blockage, let-7c replacement therapy circumvents the obstruction and artificially restores let-7c to pre-malignant levels. This treatment aims to restore functionality to the cell rather than triggering cell death. This is, of course, an ideal scenario, where artificial replacement or suppression of miRNAs results in a restoration of functionality. In reality, however, it is more plausible that this therapy is used in conjunction with already established therapies to improve sensitivity.

Conventional therapeutics such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy aim to create intolerable endogenous levels of reactive oxygen species within the malignant cells in an attempt to trigger apoptosis. Surgical resection, meanwhile, seeks to remove the affected tissue to prohibit further growth. Personalized miRNA therapy aims to treat cancer from a new standpoint. By using miRNA replacement or antagomiRNAs, the goal is to reset cellular miRNA levels. The exciting prospect for this therapy is that the initial blockage that triggered the miRNA dysregulation is bypassed allowing levels to be restored artificially. RNA therapeutics are gaining much momentum. For example, Onpattro, an RNAi therapy developed by Alnylam Pharmaceuticals for the treatment of adult patients with polyneuropathy of hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis, is the first of its kind. Onpattro contains a small interfering RNA (siRNA) formulated with a lipid complex and is termed patisiran. The drug works by binding to the TTR protein, thus preventing deformation through the RNAi. The reduction in TTR protein levels in the liver results in a decrease in subsequent amyloid deposits. Onpattro was approved by the FDA (August 2018) based on the highly positive outcome of a global phase III clinical trial. This trial was termed APOLLO and was a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind evaluation of the efficacy and safety of Onpattro in patients. In total, 225 patients were enrolled in APOLLO and treated over the course of 18 months. Within the trial 148 patients received Onpattro once every 3 weeks (0.3 mg/kg body weight), whereas the remaining received the placebo. Patients receiving the therapy showed improvements, with 51% of patients exhibiting an improved quality of life, as measured by the Norfolk Quality of Life Diabetic Neuropathy (QoL-DN), as opposed to only 10% in the placebo control.82

Of course, the efficacy of any miRNA therapy is reliant on an effective delivery system. This system must be designed in a way that would overcome both extracellular and intracellular obstacles, ensuring the successful shipment of the cargo resulting in the desired effect without eliciting an immune response. It would also be beneficial for such a vector to be specific to the site of action as not to elicit any off-target effects elsewhere in the body.

References

- 1.Ayub S.G., Kaul D., Ayub T. Microdissecting the role of microRNAs in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer. Cancer Genet. 2015;208:289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalanqui M.J., O’Doherty M., Dunne N.J., McCarthy H.O. MiRNA 34a: a therapeutic target for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2016;20:1075–1085. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2016.1162294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun T., McKay R., Lee G.-S.M., Kantoff P. The role of miRNAs in prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2015;68:589–590. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cancer Research UK Prostate cancer statistics. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/prostate-cancer#heading-Zero

- 5.Thompson I.M., Pauler D.K., Goodman P.J., Tangen C.M., Lucia M.S., Parnes H.L., Minasian L.M., Ford L.G., Lippman S.M., Crawford E.D. Prevalence of prostate cancer among men with a prostate-specific antigen level < or =4.0 ng per milliliter. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:2239–2246. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang M.C., Valenzuela L.A., Murphy G.P., Chu T.M. Purification of a human prostate specific antigen. Invest. Urol. 1979;17:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schröder F.H., Hugosson J., Roobol M.J., Tammela T.L., Ciatto S., Nelen V., Kwiatkowski M., Lujan M., Lilja H., Zappa M., ERSPC Investigators Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1320–1328. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saarimäki L., Hugosson J., Tammela T.L., Carlsson S., Talala K., Auvinen A. Impact of Prostatic-specific Antigen Threshold and Screening Interval in Prostate Cancer Screening Outcomes: Comparing the Swedish and Finnish European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer Centres. Eur. Urol. Focus. 2019;5:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Association of Urology EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. https://uroweb.org/guideline/prostate-cancer/

- 10.Du W., Hong L., Yao T., Yang X., He Q., Yang B., Hu Y. Synthesis and evaluation of water-soluble docetaxel prodrugs-docetaxel esters of malic acid. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:6323–6330. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu Y., Liu C., Nadiminty N., Lou W., Tummala R., Evans C.P., Gao A.C. Inhibition of ABCB1 expression overcomes acquired docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013;12:1829–1836. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luu H.N., Lin H.-Y., Sørensen K.D., Ogunwobi O.O., Kumar N., Chornokur G., Phelan C., Jones D., Kidd L., Batra J. miRNAs associated with prostate cancer risk and progression. BMC Urol. 2017;17:18. doi: 10.1186/s12894-017-0206-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bharali D.J., Sudha T., Cui H., Mian B.M., Mousa S.A. Anti-CD24 nano-targeted delivery of docetaxel for the treatment of prostate cancer. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2017;13:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fabris L., Ceder Y., Chinnaiyan A.M., Jenster G.W., Sorensen K.D., Tomlins S., Visakorpi T., Calin G.A. The Potential of MicroRNAs as Prostate Cancer Biomarkers. Eur. Urol. 2016;70:312–322. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao C., Liu J., Wu X., Tai Z., Gao Y., Zhu Q., Li J., Zhang L., Hu C., Gu F. Reducible self-assembling cationic polypeptide-based micelles mediate co-delivery of doxorubicin and microRNA-34a for androgen-independent prostate cancer therapy. J. Control. Release. 2016;232:203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werner T.V., Hart M., Nickels R., Kim Y.J., Menger M.D., Bohle R.M., Keller A., Ludwig N., Meese E. MiR-34a-3p alters proliferation and apoptosis of meningioma cells in vitro and is directly targeting SMAD4, FRAT1 and BCL2. Aging (Albany N.Y.) 2017;9:932–954. doi: 10.18632/aging.101201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.miRBase: the microRNA database. http://www.mirbase.org/summary.shtml?org=hsa.

- 18.Catto J.W.F., Alcaraz A., Bjartell A.S., De Vere White R., Evans C.P., Fussel S., Hamdy F.C., Kallioniemi O., Mengual L., Schlomm T., Visakorpi T. MicroRNA in prostate, bladder, and kidney cancer: a systematic review. Eur. Urol. 2011;59:671–681. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulholland E.J., Dunne N., McCarthy H.O. MicroRNA as Therapeutic Targets for Chronic Wound Healing. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2017;8:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khanmi K., Ignacimuthu S., Paulraj M.G. MicroRNA in prostate cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2015;451(Pt B):154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aakula A., Kohonen P., Leivonen S.-K., Mäkelä R., Hintsanen P., Mpindi J.P., Martens-Uzunova E., Aittokallio T., Jenster G., Perälä M. Systematic Identification of MicroRNAs That Impact on Proliferation of Prostate Cancer Cells and Display Changed Expression in Tumor Tissue. Eur. Urol. 2016;69:1120–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong C.M., Liu C., Lou W., Lombard A.P., Evans C.P., Gao A.C. MicroRNA-181a promotes docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2017;77:1020–1028. doi: 10.1002/pros.23358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu G., Wang J., Chen G., Zhao X. microRNA-204 modulates chemosensitivity and apoptosis of prostate cancer cells by targeting zinc-finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017;9:3599–3610. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X., Luo X., Wu Y., Xia D., Chen W., Fang Z., Deng J., Hao Y., Yang X., Zhang T. MicroRNA-34a Attenuates Paclitaxel Resistance in Prostate Cancer Cells via Direct Suppression of JAG1/Notch1 Axis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018;50:261–276. doi: 10.1159/000494004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ekimler S., Sahin K. Computational Methods for MicroRNA Target Prediction. Genes (Basel) 2014;5:671–683. doi: 10.3390/genes5030671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang W., Le T.D., Liu L., Zhou Z.-H., Li J. Predicting miRNA Targets by Integrating Gene Regulatory Knowledge with Expression Profiles. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0152860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie B., Ding Q., Han H., Wu D. miRCancer: a microRNA-cancer association database constructed by text mining on literature. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:638–644. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang Q., Wang Y., Hao Y., Juan L., Teng M., Zhang X., Li M., Wang G., Liu Y. miR2Disease: a manually curated database for microRNA deregulation in human disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D98–D104. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruepp A., Kowarsch A., Schmidl D., Buggenthin F., Brauner B., Dunger I., Fobo G., Frishman G., Montrone C., Theis F.J. PhenomiR: a knowledgebase for microRNA expression in diseases and biological processes. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R6. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-1-r6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyerinas B., Park S.-M., Hau A., Murmann A.E., Peter M.E. The role of let-7 in cell differentiation and cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2010;17:F19–F36. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roush S., Slack F.J. The let-7 family of microRNAs. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson C.D., Esquela-Kerscher A., Stefani G., Byrom M., Kelnar K., Ovcharenko D., Wilson M., Wang X., Shelton J., Shingara J. The let-7 microRNA represses cell proliferation pathways in human cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7713–7722. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balzeau J., Menezes M.R., Cao S., Hagan J.P. The LIN28/let-7 Pathway in Cancer. Front. Genet. 2017;8:31. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2017.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Büssing I., Slack F.J., Grosshans H. let-7 microRNAs in development, stem cells and cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 2008;14:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou Y., Liang H., Liao Z., Wang Y., Hu X., Chen X., Xu L., Hu Z. miR-203 enhances let-7 biogenesis by targeting LIN28B to suppress tumor growth in lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:42680. doi: 10.1038/srep42680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou J., Bi C., Ching Y.Q., Chooi J.Y., Lu X., Quah J.Y., Toh S.H., Chan Z.L., Tan T.Z., Chong P.S., Chng W.J. Inhibition of LIN28B impairs leukemia cell growth and metabolism in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017;10:138. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0507-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manier S., Powers J.T., Sacco A., Glavey S.V., Huynh D., Reagan M.R., Salem K.Z., Moschetta M., Shi J., Mishima Y. The LIN28B/let-7 axis is a novel therapeutic pathway in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2017;31:853–860. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang T.-C., Zeitels L.R., Hwang H.-W., Chivukula R.R., Wentzel E.A., Dews M., Jung J., Gao P., Dang C.V., Beer M.A. Lin-28B transactivation is necessary for Myc-mediated let-7 repression and proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:3384–3389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808300106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vira D., Basak S.K., Veena M.S., Wang M.B., Batra R.K., Srivatsan E.S. Cancer stem cells, microRNAs, and therapeutic strategies including natural products. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012;31:733–751. doi: 10.1007/s10555-012-9382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Archer L.K., Frame F.M., Maitland N.J. Stem cells and the role of ETS transcription factors in the differentiation hierarchy of normal and malignant prostate epithelium. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017;166:68–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Birnie R., Bryce S.D., Roome C., Dussupt V., Droop A., Lang S.H., Berry P.A., Hyde C.F., Lewis J.L., Stower M.J. Gene expression profiling of human prostate cancer stem cells reveals a pro-inflammatory phenotype and the importance of extracellular matrix interactions. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R83. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-5-r83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oskarsson T., Batlle E., Massagué J. Metastatic stem cells: sources, niches, and vital pathways. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:306–321. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Degrauwe N., Schlumpf T.B., Janiszewska M., Martin P., Cauderay A., Provero P., Riggi N., Suvà M.L., Paro R., Stamenkovic I. The RNA Binding Protein IMP2 Preserves Glioblastoma Stem Cells by Preventing let-7 Target Gene Silencing. Cell Rep. 2016;15:1634–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang M., Lee K.H., Lee H.S., Jeong C.W., Ku J.H., Kim H.H., Kwak C. Concurrent treatment with simvastatin and NF-κB inhibitor in human castration-resistant prostate cancer cells exerts synergistic anti-cancer effects via control of the NF-κB/LIN28/let-7 miRNA signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albino D., Civenni G., Dallavalle C., Roos M., Jahns H., Curti L., Rossi S., Pinton S., D’Ambrosio G., Sessa F. Activation of the Lin28/let-7 Axis by Loss of ESE3/EHF Promotes a Tumorigenic and Stem-like Phenotype in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:3629–3643. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nadiminty N., Tummala R., Lou W., Zhu Y., Shi X.B., Zou J.X., Chen H., Zhang J., Chen X., Luo J. MicroRNA let-7c Is Downregulated in Prostate Cancer and Suppresses Prostate Cancer Growth. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nadiminty N., Tummala R., Lou W., Zhu Y., Zhang J., Chen X., eVere White R.W., Kung H.J., Evans C.P., Gao A.C. MicroRNA let-7c suppresses androgen receptor expression and activity via regulation of Myc expression in prostate cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:1527–1537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.278705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Exiqon miR Search. https://www.exiqon.com/miRSearch.

- 50.Naeem H., Küffner R., Csaba G., Zimmer R. miRSel: automated extraction of associations between microRNAs and genes from the biomedical literature. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li J.-H., Liu S., Zhou H., Qu L.-H., Yang J.-H. starBase v2.0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D92–D97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Copley M.R., Babovic S., Benz C., Knapp D.J., Beer P.A., Kent D.G., Wohrer S., Treloar D.Q., Day C., Rowe K. The Lin28b-let-7-Hmga2 axis determines the higher self-renewal potential of fetal haematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:916–925. doi: 10.1038/ncb2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park S.-M., Shell S., Radjabi A.R., Schickel R., Feig C., Boyerinas B., Dinulescu D.M., Lengyel E., Peter M.E. Let-7 prevents early cancer progression by suppressing expression of the embryonic gene HMGA2. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2585–2590. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.21.4845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cai J., Shen G., Liu S., Meng Q. Downregulation of HMGA2 inhibits cellular proliferation and invasion, improves cellular apoptosis in prostate cancer. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:699–707. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3853-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh A., Settleman J. EMT, cancer stem cells and drug resistance: an emerging axis of evil in the war on cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:4741–4751. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thiery J.P., Sleeman J.P. Complex networks orchestrate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:131–142. doi: 10.1038/nrm1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watanabe S., Ueda Y., Akaboshi S., Hino Y., Sekita Y., Nakao M. HMGA2 maintains oncogenic RAS-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human pancreatic cancer cells. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;174:854–868. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shi Z., Wu D., Tang R., Li X., Chen R., Xue S., Zhang C., Sun X. Silencing of HMGA2 promotes apoptosis and inhibits migration and invasion of prostate cancer cells. J. Biosci. 2016;41:229–236. doi: 10.1007/s12038-016-9603-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cole M.D., McMahon S.B. The Myc oncoprotein: a critical evaluation of transactivation and target gene regulation. Oncogene. 1999;18:2916–2924. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Donnell K.A., Wentzel E.A., Zeller K.I., Dang C.V., Mendell J.T. c-Myc-regulated microRNAs modulate E2F1 expression. Nature. 2005;435:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nature03677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gurel B., Iwata T., Koh C.M., Jenkins R.B., Lan F., Van Dang C., Hicks J.L., Morgan J., Cornish T.C., Sutcliffe S. Nuclear MYC protein overexpression is an early alteration in human prostate carcinogenesis. Mod. Pathol. 2008;21:1156–1167. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang J., Kobayashi T., Floc’h N., Kinkade C.W., Aytes A., Dankort D., Lefebvre C., Mitrofanova A., Cardiff R.D., McMahon M. B-Raf activation cooperates with PTEN loss to drive c-Myc expression in advanced prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4765–4776. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fan L., Peng G., Sahgal N., Fazli L., Gleave M., Zhang Y., Hussain A., Qi J. Regulation of c-Myc expression by the histone demethylase JMJD1A is essential for prostate cancer cell growth and survival. Oncogene. 2016;35:2441–2452. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Helland Å., Anglesio M.S., George J., Cowin P.A., Johnstone C.N., House C.M., Sheppard K.E., Etemadmoghadam D., Melnyk N., Rustgi A.K. Deregulation of MYCN, LIN28B and LET7 in a Molecular Subtype of Aggressive High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancers. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao D., Pan C., Sun J., Gilbert C., Drews-Elger K., Azzam D.J., Picon-Ruiz M., Kim M., Ullmer W., El-Ashry D. VEGF drives cancer-initiating stem cells through VEGFR-2/Stat3 signaling to upregulate Myc and Sox2. Oncogene. 2015;34:3107–3119. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haselmann V., Kurz A., Bertsch U., Hübner S., Olempska-Müller M., Fritsch J., Häsler R., Pickl A., Fritsche H., Annewanter F. Nuclear death receptor TRAIL-R2 inhibits maturation of let-7 and promotes proliferation of pancreatic and other tumor cells. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:278–290. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gang X., Wang Y., Wang Y., Zhao Y., Ding L., Zhao J., Sun L., Wang G. Suppression of casein kinase 2 sensitizes tumor cells to antitumor TRAIL therapy by regulating the phosphorylation and localization of p65 in prostate cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2015;34:1599–1604. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Anees M., Horak P., El-Gazzar A., Susani M., Heinze G., Perco P., Loda M., Lis R., Krainer M., Oh W.K. Recurrence-free survival in prostate cancer is related to increased stromal TRAIL expression. Cancer. 2011;117:1172–1182. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hartwig T., Montinaro A., von Karstedt S., Sevko A., Surinova S., Chakravarthy A., Taraborrelli L., Draber P., Lafont E., Arce Vargas F. The TRAIL-Induced Cancer Secretome Promotes a Tumor-Supportive Immune Microenvironment via CCR2. Mol. Cell. 2017;65:730–742.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou M., Liu X., Li Z., Huang Q., Li F., Li C.-Y. Caspase-3 regulates the migration, invasion and metastasis of colon cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2018;143:921–930. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pu X., Storr S.J., Zhang Y., Rakha E.A., Green A.R., Ellis I.O., Martin S.G. Caspase-3 and caspase-8 expression in breast cancer: caspase-3 is associated with survival. Apoptosis. 2017;22:357–368. doi: 10.1007/s10495-016-1323-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang L., Yuan C., Lv K., Xie S., Fu P., Liu X., Chen Y., Qin C., Deng W., Hu W. Lin28 Mediates Radiation Resistance of Breast Cancer Cells via Regulation of Caspase, H2A.X and Let-7 Signaling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Winter R.N., Kramer A., Borkowski A., Kyprianou N. Loss of caspase-1 and caspase-3 protein expression in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rodríguez-Berriguete G., Torrealba N., Ortega M.A., Martínez-Onsurbe P., Olmedilla G., Paniagua R., Guil-Cid M., Fraile B., Royuela M. Prognostic value of inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) and caspases in prostate cancer: caspase-3 forms and XIAP predict biochemical progression after radical prostatectomy. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:809. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1839-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jin H.Y., Gonzalez-Martin A., Miletic A.V., Lai M., Knight S., Sabouri-Ghomi M., Head S.R., Macauley M.S., Rickert R.C., Xiao C. Transfection of microRNA Mimics Should Be Used with Caution. Front. Genet. 2015;6:340. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wilson J.M. Lessons learned from the gene therapy trial for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2009;96:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tros de Ilarduya C., Sun Y., Düzgüneş N. Gene delivery by lipoplexes and polyplexes. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010;40:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang N. An overview of viral and nonviral delivery systems for microRNA. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2015;5:179–181. doi: 10.4103/2230-973X.167646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Piao L., Zhang M., Datta J., Xie X., Su T., Li H., Teknos T.N., Pan Q. Lipid-based nanoparticle delivery of Pre-miR-107 inhibits the tumorigenicity of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol. Ther. 2012;20:1261–1269. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen Z.-H., Zhang G.-L., Li H.-R., Luo J.D., Li Z.X., Chen G.M., Yang J. A panel of five circulating microRNAs as potential biomarkers for prostate cancer. Prostate. 2012;72:1443–1452. doi: 10.1002/pros.22495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schaefer A., Jung M., Mollenkopf H.-J., Wagner I., Stephan C., Jentzmik F., Miller K., Lein M., Kristiansen G., Jung K. Diagnostic and prognostic implications of microRNA profiling in prostate carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer. 2010;126:1166–1176. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Clinical Trials Arena.Onpattro (patisiran) for the treatment of polyneuropathy of hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis in adults. https://www.clinicaltrialsarena.com/projects/onpattro-for-hereditary-transthyretin-mediated-amyloidosis/.

- 83.Li T., Li D., Sha J., Sun P., Huang Y. MicroRNA-21 directly targets MARCKS and promotes apoptosis resistance and invasion in prostate cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;383:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jalava S.E., Urbanucci A., Latonen L., Waltering K.K., Sahu B., Jänne O.A., Seppälä J., Lähdesmäki H., Tammela T.L., Visakorpi T. Androgen-regulated miR-32 targets BTG2 and is overexpressed in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31:4460–4471. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu C., Kelnar K., Liu B., Chen X., Calhoun-Davis T., Li H., Patrawala L., Yan H., Jeter C., Honorio S. The microRNA miR-34a inhibits prostate cancer stem cells and metastasis by directly repressing CD44. Nat. Med. 2011;17:211–215. doi: 10.1038/nm.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang G., Tian X., Li Y., Wang Z., Li X., Zhu C. miR-27b and miR-34a enhance docetaxel sensitivity of prostate cancer cells through inhibiting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;97:736–744. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.10.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang Y., Huang J.-W., Calses P., Kemp C.J., Taniguchi T. MiR-96 downregulates REV1 and RAD51 to promote cellular sensitivity to cisplatin and PARP inhibition. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4037–4046. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang M., Ren D., Guo W., Wang Z., Huang S., Du H., Song L., Peng X. Loss of miR-100 enhances migration, invasion, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stemness properties in prostate cancer cells through targeting Argonaute 2. Int. J. Oncol. 2014;45:362–372. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Honeywell D.R., Cabrita M.A., Zhao H., Dimitroulakos J., Addison C.L. miR-105 inhibits prostate tumour growth by suppressing CDK6 levels. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang W., Mao Y.-Q., Wang H., Yin W.-J., Zhu S.-X., Wang W.-C. MiR-124 suppresses cell motility and adhesion by targeting talin 1 in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2015;15:49. doi: 10.1186/s12935-015-0189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ozen M., Creighton C.J., Ozdemir M., Ittmann M. Widespread deregulation of microRNA expression in human prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:1788–1793. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen Q., Zhao X., Zhang H., Yuan H., Zhu M., Sun Q., Lai X., Wang Y., Huang J., Yan J., Yu J. MiR-130b suppresses prostate cancer metastasis through down-regulation of MMP2. Mol. Carcinog. 2015;54:1292–1300. doi: 10.1002/mc.22204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tao J., Wu D., Xu B., Qian W., Li P., Lu Q., Yin C., Zhang W. microRNA-133 inhibits cell proliferation, migration and invasion in prostate cancer cells by targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor. Oncol. Rep. 2012;27:1967–1975. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Xiao J., Gong A.-Y., Eischeid A.N., Chen D., Deng C., Young C.Y., Chen X.M. miR-141 modulates androgen receptor transcriptional activity in human prostate cancer cells through targeting the small heterodimer partner protein. Prostate. 2012;72:1514–1522. doi: 10.1002/pros.22501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kojima S., Enokida H., Yoshino H., Itesako T., Chiyomaru T., Kinoshita T., Fuse M., Nishikawa R., Goto Y., Naya Y. The tumor-suppressive microRNA-143/145 cluster inhibits cell migration and invasion by targeting GOLM1 in prostate cancer. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;59:78–87. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2013.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sun Q., Zhao X., Liu X., Wang Y., Huang J., Jiang B., Chen Q., Yu J. miR-146a functions as a tumor suppressor in prostate cancer by targeting Rac1. Prostate. 2014;74:1613–1621. doi: 10.1002/pros.22878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wu Z., He B., He J., Mao X. Upregulation of miR-153 promotes cell proliferation via downregulation of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in human prostate cancer. Prostate. 2013;73:596–604. doi: 10.1002/pros.22600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhu C., Shao P., Bao M., Li P., Zhou H., Cai H., Cao Q., Tao L., Meng X., Ju X. miR-154 inhibits prostate cancer cell proliferation by targeting CCND2. Urol. Oncol. 2014;32:31.e9–31.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cha Y.J., Lee J.H., Han H.H., Kim B.G., Kang S., Choi Y.D., Cho N.H. MicroRNA alteration and putative target genes in high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostate cancer: STAT3 and ZEB1 are upregulated during prostate carcinogenesis. Prostate. 2016;76:937–947. doi: 10.1002/pros.23183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.He L., Yao H., Fan L.H., Liu L., Qiu S., Li X., Gao J.P., Hao C.Q. MicroRNA-181b expression in prostate cancer tissues and its influence on the biological behavior of the prostate cancer cell line PC-3. Genet. Mol. Res. 2013;12:1012–1021. doi: 10.4238/2013.April.2.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tong S.J., Liu J., Wang X., Qu L.X. microRNA-181 promotes prostate cancer cell proliferation by regulating DAX-1 expression. Exp. Ther. Med. 2014;8:1296–1300. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liu R., Li J., Teng Z., Zhang Z., Xu Y. Overexpressed microRNA-182 promotes proliferation and invasion in prostate cancer PC-3 cells by down-regulating N-myc downstream regulated gene 1 (NDRG1) PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e68982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ueno K., Hirata H., Shahryari V., Deng G., Tanaka Y., Tabatabai Z.L., Hinoda Y., Dahiya R. microRNA-183 is an oncogene targeting Dkk-3 and SMAD4 in prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2013;108:1659–1667. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Casanova-Salas I., Masiá E., Armiñán A., Calatrava A., Mancarella C., Rubio-Briones J., Scotlandi K., Vicent M.J., López-Guerrero J.A. MiR-187 Targets the Androgen-Regulated Gene ALDH1A3 in Prostate Cancer. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0125576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Williams L.V., Veliceasa D., Vinokour E., Volpert O.V. miR-200b inhibits prostate cancer EMT, growth and metastasis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e83991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Aceto N., Sausgruber N., Brinkhaus H., Gaidatzis D., Martiny-Baron G., Mazzarol G., Confalonieri S., Quarto M., Hu G., Balwierz P.J. Tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 promotes breast cancer progression and maintains tumor-initiating cells via activation of key transcription factors and a positive feedback signaling loop. Nat. Med. 2012;18:529–537. doi: 10.1038/nm.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yin J., Zhao J., Hu W., Yang G., Yu H., Wang R., Wang L., Zhang G., Fu W., Dai L. Disturbance of the let-7/LIN28 double-negative feedback loop is associated with radio- and chemo-resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lozier A.M., Rich M.E., Grawe A.P., Peck A.S., Zhao P., Chang A.T., Bond J.P., Sholler G.S. Targeting ornithine decarboxylase reverses the LIN28/Let-7 axis and inhibits glycolytic metabolism in neuroblastoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:196–206. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chien C.-S., Wang M.-L., Chu P.-Y., Chang Y.L., Liu W.H., Yu C.C., Lan Y.T., Huang P.I., Lee Y.Y., Chen Y.W. Lin28B/Let-7 Regulates Expression of Oct4 and Sox2 and Reprograms Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells to a Stem-like State. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2553–2565. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Busch B., Bley N., Müller S., Glaß M., Misiak D., Lederer M., Vetter M., Strauß H.G., Thomssen C., Hüttelmaier S. The oncogenic triangle of HMGA2, LIN28B and IGF2BP1 antagonizes tumor-suppressive actions of the let-7 family. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:3845–3864. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kugel S., Sebastián C., Fitamant J., Ross K.N., Saha S.K., Jain E., Gladden A., Arora K.S., Kato Y., Rivera M.N. SIRT6 Suppresses Pancreatic Cancer through Control of Lin28b. Cell. 2016;165:1401–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]