Abstract

Background

It is increasingly being recognized that the elimination of HCV requires a multidisciplinary approach and effective cooperation between primary and secondary care.

Objectives

As part of a project (HepCare Europe) to integrate primary and secondary care for patients at risk of or infected with HCV, we developed a multidisciplinary educational Masterclass series for healthcare professionals (HCPs) working in primary care in Dublin and Bucharest. This article aims to describe and evaluate the series and examine how this model might be implemented into practice.

Methods

GPs and other HCPs working in primary care, addiction treatment services and NGOs were invited to eight 1 day symposia (HCV Masterclass series), examining the burden and management of HCV in key populations. Peer-support sessions were also conducted, to give people affected by HCV and community-based organizations working with those directly affected, an update on the latest developments in HCV treatment.

Results

One hundred percent of participants ‘strongly agreed’ or ‘agreed’ that the Masterclass helped them to appreciate the role of integrated services in ‘the management of patients with HCV’. One hundred percent of participants indicated the importance of a ‘designated nurse to liaise with hospital services’. An improvement of knowledge regarding HCV management of patients with high-risk behaviour was registered at the end of the course.

Conclusions

Integrated approaches to healthcare and improving the knowledge of HCPs and patients of the latest developments in HCV treatment are very important strategies that can enhance the HCV care pathway and treatment outcomes.

Introduction

Addressing the challenge of developing new models of integrated care for HCV requires effective cooperation between primary and secondary care involving multidisciplinary approaches to care. The HepCare Europe project1 is an EU-supported service innovation project and feasibility study at four European sites (Dublin, London, Seville and Bucharest) to develop, implement and evaluate interventions to enhance identification and treatment of HCV among key populations [people who inject drugs (PWID), the homeless and prisoners].

A large number of healthcare professionals (HCPs) and social care professionals (SCPs) have a key role to play in the treatment pathway for hepatitis C. Therefore, education of the patient as well as HCPs and community service provider organizations working with those at risk of acquiring hepatitis C is extremely important in order to optimize treatment outcomes. Previous studies identified that educating patients about HCV increased their knowledge of HCV, increased screening rates, increased treatment uptake,2 reduced infection-related risk behaviour3 and promoted access to care.4 Therefore, linking them to an appropriate and efficient multidisciplinary team can enhance HCV patient care.

Shared decision making within a multidisciplinary team is a vital component of effective hepatitis C treatment. The proportion of PWID who accept referral to weekly HCV peer-support groups to be assessed for HCV is higher than the proportion of those accepting hospital-based referral for HCV clinical care, underlining the positive effect the presence of a multidisciplinary team has, as they integrate general health, addiction and HCV treatment in an available, acceptable and predictable manner.5 The current literature highlights the use of group activities, didactic lectures, workshops, case studies, demonstrations and small group discussions as well as other instructional and activity-based methods when educating HCPs around the world in integrative, cooperative healthcare.6 The duration of different symposiums, their frequency and the variation of techniques utilized depend on a variety of factors, such as the respective topic, the target professionals and the clinical domains.7

By educating all HCPs and SCPs playing a key role in the hepatitis C care pathway, the success of multidisciplinary care for hepatitis C would expand beyond addressing the narrow scope of the virological disease alone, to incorporate the bigger picture of any accompanying common and complex health issues that may have been overlooked, such as pain, asthma, substance use disorders (including alcohol), mental health issues, cardiac conditions, rheumatological conditions and others. By distributing resources and increasing the competency and role of primary care and other healthcare/non-healthcare professionals, more patients would be able to access treatment while minimizing the pressure placed on scarce speciality care.8

Hence, as part of the HepCare project to integrate primary and secondary care for patients at risk of or infected with HCV, we developed a series of educational symposia at the Dublin and Bucharest sites, aimed at HCPs and community service provider organizations involved in the hepatitis C care pathway. This article aims to evaluate a series of educational symposia that examined how to integrate treatment of HCV in primary and secondary care and to identify how this model might be achieved in practice. We describe participants’ appraisal of the Masterclasses and their feedback on implementing a multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of hepatitis C.

Methods

Ethics

The study was approved by the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital Research Ethics Committee in Dublin (1/378/1722) and the Victor Babes Clinical Hospital for Infectious and Tropical Diseases Research Ethics in Bucharest (3/06.01.2016).

Study design and setting

From local general practices, NGOs and addiction treatment services, GPs/other HCPs working in primary care were invited to eight HCV symposia (HCV Masterclass series) in Dublin, Ireland, and Bucharest, Romania, to examine the burden of HCV and how to optimize HCV care. In Bucharest HCPs from three opioid substitution therapy (OST) centres, two high-security prisons, two night shelters and two NGOs, and GPs working in districts from Bucharest with a high burden of vulnerable people were invited. In Dublin invitations to attend the HCV Masterclasses were sent to all HCPs (infectious disease consultants, GPs, pharmacists, nurses, community service providers) and organizations involved in the HCV care pathway in the Dublin area. The delivery method included a series of short PowerPoint presentations delivered by a multidisciplinary range of healthcare professionals (Appendices E and F, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online). Information on how to prevent new infections, why/how to screen, new approaches to diagnosis and treatment as well as treating coexisting problem alcohol use were addressed. In Bucharest the presentations were focused mainly on the complex problems of people who inject drugs, people using new psychoactive drugs and on HIV/HCV-coinfected patients. In Dublin, PowerPoint presentations were delivered by a range of HCPs involved in the HCV care pathway (infectious disease consultants, GPs, pharmacists, nurses, community service providers). Each presenter chose the content for their presentation based on how best to inform the audience of their role and priorities in an integrated HCV care pathway. Attendees received no funds for attending and the pharmaceutical industry was not involved in the organization of HCV Masterclasses.

Key outcomes were analysed across the Masterclass series, including the effectiveness of the method of delivery, the usefulness of the Masterclass symposium and the usefulness of the support provided by the HepCare Europe programme when implemented into practice.

Data collection

Dublin

Each Masterclass was delivered to all participants and evaluation occurred immediately post-session. Following each symposium, a questionnaire was distributed among the participants, who were asked to rate, using a five-point Likert scale (where 4=strongly agree, 0=strongly disagree), how useful the Masterclass had been, the effectiveness of information delivery and how the programme could best be implemented in practice (Appendix A). Participants were also asked to rate, using a four-point Likert scale (where 4=very useful, 0=not at all useful), how useful they thought the support provided by the HepCare Europe programme would be when implemented in their practice/organization (Appendix A). Finally, participants were asked an open-ended question about what other support/activity would help them manage patients with HCV and also asked to provide ‘any other comments’ relating to the Masterclass (Appendix A). Seven peer-support educational sessions were also conducted in Dublin to give people affected by HCV and community-based organizations working with those directly affected an update on the latest developments in HCV treatment.

Bucharest

In Bucharest, as well as the Masterclass questionnaire (Appendix B), a pre/post Masterclass evaluation instrument (Appendices C and D) was used to measure participants’ general knowledge about HCV management in key populations in Bucharest. This allowed an evaluation of the improvement of participants’ knowledge of current HCV care as a result of the Masterclass. The post-intervention questionnaire also asked for participants’ views about the usefulness of the session and the implementation of a multidisciplinary approach to HCV management.

In addition to the Masterclass series, 11 peer-support sessions were also conducted for patients from key populations in Bucharest (homeless people and PWID) as training day programmes. The participants received flyers and a booklet, containing information about modes of HCV acquisition, HCV diagnosis, prevention methods and treatment with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs). They also had the opportunity to ask questions, to learn from the experience of peers and to share their fears and social problems.

The written materials were also distributed in waiting rooms of GPs/primary care facilities, in emergency rooms of hospitals and, with the help of social workers, to individuals who inject drugs who were living on the streets. The booklets were distributed to peers, social workers from NGOs, psychologists and other HCPs involved in HCV management.

Analysis

The percentage of participants choosing a particular item on the Likert scale was calculated for each Masterclass. Content analysis of responses to open-ended questions was conducted; similar responses were grouped and numbers of participants were counted for each group.

Results

Over 200 participants involved in HCV care in the community from participating countries attended the Masterclass series. The results show the variation in percentage scores on an item across the Masterclass series.

Dublin (see Table 1 for summary of responses)

Table 1.

Summary of responses from Masterclasses (Dublin)

| Category | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither | Agree | Strongly agree | Total number of responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As a result of the seminar, I am better able to: | ||||||

| Appreciate the role of primary care in the management of patients with HCV | 0% | 0% | 0% | 62% | 38% | 58 |

| Appreciate the role of secondary care in the management of patients with HCV | 0% | 0% | 0% | 57% | 43% | 58 |

| Describe new approaches to assessment for patients with HCV (e.g. FibroScan) | 0% | 0% | 5% | 48% | 47% | 58 |

| Describe new approaches to treatment for patients with HCV | 0% | 0% | 14% | 52% | 34% | 58 |

| Understand the importance of integrating services to better treat patients | 0% | 0% | 2% | 58% | 40% | 58 |

| Understand that patients have multiple co- morbidities | 0% | 0% | 0% | 32% | 68% | 58 |

| Better understand complications of untreated HCV infection | 0% | 15% | 30% | 35% | 20% | 57 |

| Interact with the Mater Hospital Infectious Diseases Department | 0% | 0% | 20% | 40% | 40% | 56 |

|

| ||||||

| The following were useful in helping me achieve these outcomes: | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Presentations | 0% | 0% | 5% | 60% | 35% | 54 |

|

| ||||||

| Support | Not at all useful | Somewhat useful | Useful | Very useful | Total number of responses | |

|

| ||||||

| In implementing the new ‘HepCare’ programme in your practice, how useful would you find the following supports? | ||||||

| Audit and feedback | 0% | 19% | 56% | 25% | 48 | |

| Educational programmes | 0% | 0% | 71% | 29% | 49 | |

| Computerized decision-making support | 0% | 12% | 41% | 47% | 48 | |

| A designated nurse to liaise with hospital services | 0% | 0% | 11% | 89% | 52 | |

| Academic detailing (i.e. practice visits by team) | 0% | 6% | 18% | 76% | 46 | |

108 participants attended three Masterclasses; 58 participants completed evaluation forms.

The most highly rated outcome was that the Masterclass helped participants ‘appreciate the role of primary care’ and ‘secondary care’ in the ‘management of patients with HCV’ (100% of participants ‘strongly agreed’ or ‘agreed’). Ninety-seven to 100 percent of participants ‘strongly agreed’ or ‘agreed’ they were better able to ‘describe new approaches to assessment (FibroScan)’ and ‘new approaches to treatment’ (88%–96%) of patients with HCV. In regard to making an integrated model of care happen in practice, 100% of participants acknowledged the importance of a ‘designated nurse to liaise with hospital services’. Some expanded on this topic in the open question section, saying it would be ‘vital’ as nurse liaison would be able to ‘join the dots’ of a patient’s treatment and ‘ease communication’. Participants thought that that ‘educational programmes’ (91%–100%) and ‘computerized-decision making’ (88%–92%) would be ‘useful’ or ‘very useful’ support in their everyday management of hepatitis C.

However, despite positive appraisal of the Masterclass symposiums, some participants commented on a need to ‘link up with health’, gain ‘feedback from teams’ and receive ‘letters of progress’ on ‘treatment plans’, all of which point to a need to enhance communication between HCPs.

Bucharest (see Table 2 for summary of responses)

Table 2.

Summary of responses from Masterclasses (Bucharest)

| Category | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither | Agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As a result of the seminar, I am better able to: | ||||||

| Understand the impact of alcohol use in clinical evolution of hepatitis C (HCV) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 2% | 98% | |

| Describe why alcohol use is an important issue among problem drug users | 0% | 0% | 2% | 73% | 25% | |

| Approach the conversation about alcohol with patients | 0% | 0% | 1% | 37% | 62% | |

| Understand the high burden of HIV/HCV coinfection among prisoners | 0% | 0% | 0% | 23% | 77% | |

| Understand the importance of HIV/HCV/TB coinfection treatment among prisoners | 0% | 0% | 0% | 15% | 85% | |

| Appreciate the complex management of HIV/HCV/TB coinfected injecting drug users | 0% | 0% | 3% | 33% | 64% | |

| Understand the new approaches regarding HCV treatment | 0% | 0% | 0% | 37% | 73% | |

| Describe the ‘treatment as prevention’ method regarding HCV treatment for patients from vulnerable groups | 0% | 0% | 0% | 10% | 90% | |

| Describe the barriers patients from vulnerable groups have to face in order to access healthcare services | 0% | 0% | 0% | 12% | 88% | |

| Appreciate the difficulties faced by injecting drug users in the process of social reintegration | 0% | 0% | 2% | 5% | 93% | |

| Appreciate the importance of integration of primary and secondary care for HCV management | 0% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 97% | |

| Improve my collaboration with medical staff from Victor Babes Hospital | 0% | 0% | 0% | 6% | 94% | |

|

| ||||||

| The following were useful in helping me achieve these outcomes: | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Presentations | 0% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 97% | |

| Workshops | 0% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 95% | |

|

| ||||||

| Support | Not at all useful | Somewhat useful | Useful | Very useful | ||

|

| ||||||

| In implementing the new ‘Hepcare’ programme in your practice, how useful would you find the following supports? | ||||||

| Educational programmes | 0% | 0% | 4% | 96% | ||

| A designated trained person to liaise with hospital services | 0% | 0% | 10% | 90% | ||

| Academic detailing (i.e. practice visits by team) | 0% | 0% | 20% | 80% | ||

| Peer support meetings for patients | 0% | 0% | 7% | 93% | ||

| Informational materials for patients | 0% | 0% | 4% | 96% | ||

| Contact with mobile teams responsible for HCV screening among vulnerable patients | 0% | 0% | 4% | 96% | ||

| Would any other support/activity help you manage patients with HCV? | 0% | 0% | 8% | 92% | ||

| Any other comments? | ||||||

The total number of participants was 143; the total number of respondents was 105.

When asked ‘Please give a brief appreciation of the seminar, scoring the following aspects from 1 (min) to 5 (max):’, the responses were: Importance of the information for daily practice, 5; Agenda of the seminar, 5; Support materials, 5; Interaction between the lecturers and the attendees, 5; Perspectives for collaboration between GPs and medical staff from the hospital for a better management of patients from vulnerable groups, 4.

When asked whether the participants would recommend the course to a colleague, 97% answered ‘Strongly agree’ and 3% ‘Agree’.

Almost all participants reported that the main reason for attending the Masterclass was to improve their knowledge about HCV management in patients with high-risk behaviour, as they were not satisfied with their current level of knowledge about this subject.

At the end of the sessions 95%–100% of HCPs agreed that the Masterclass improved their knowledge on the impact of alcohol on the clinical evolution of HCV, the increasing prevalence of HCV among prisoners, the difficulties in the management of HIV/HCV/TB-coinfected patients and the extrahepatic manifestations of HCV. They were also informed about the social and disease barriers faced by Bucharest patients in order to access DAA treatment and they acknowledged the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to the management of HCV in patients with high-risk behaviour.

A high percentage (90%–95%) agreed that a mobile team responsible for HCV screening and linkage to care for patients from key populations would be very useful for better management of HCV. In addition, they also considered that peer-support sessions and informative materials and booklets for patients are very useful in order to improve adherence to treatment and the follow-up process.

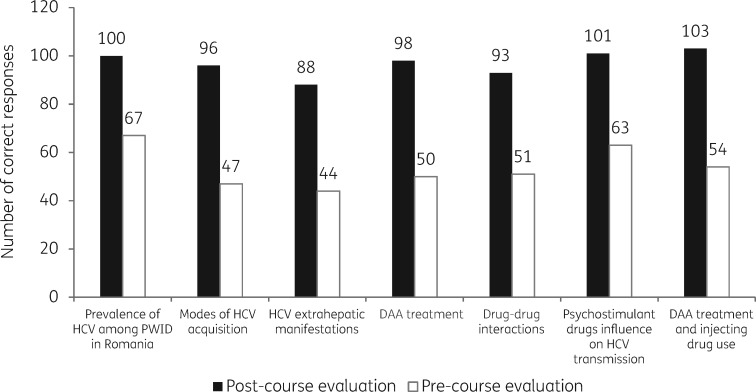

The pre/post evaluations revealed an improvement in the knowledge of HCPs regarding the prevalence of HCV among PWID in Bucharest, modes of HCV acquisition, extrahepatic manifestations, DAA treatment and drug–drug interactions (up from 42.5% to 97%). More than half of the participants agreed that the social conditions of the patients and their addiction and comorbidities, as well as the high costs of the DAA treatment and poor involvement of local authorities, are important barriers and challenges for HCPs in HCV management and for patients to access adequate medical services (Table 3 and Figure 1).

Table 3.

Summary of the results of the pre- and post-course knowledge evaluation tests for HCV Masterclasses, Bucharest

| Masterclass 1 (n=54) |

Masterclass 2 (n=51) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic | pre-course | post-course | pre-course | post-course |

| Prevalence of HCV among PWID in Romania | 33 (61.1) | 52 (96.2) | 34 (70.8) | 48 (94.1) |

| Modes of HCV acquisition | 23 (42.5) | 48 (88.9) | 24 (47.0) | 48 (94.1) |

| HCV extrahepatic manifestations | 23 (42.5) | 45 (83.3) | 21 (41.1) | 43 (84.3) |

| DAA treatment | 27 (50.0) | 49 (90.7) | 23 (45.1) | 49 (96.0) |

| Drug–drug interactions | 27 (50.0) | 47 (87.0) | 24 (47.0) | 46 (90.1) |

| Influence of injectable psychoactive drugs on HCV transmission | 33 (61.1) | 52 (96.2) | 30 (58.9) | 49 (96.0) |

| Injecting drug use and DAA treatment | 25 (46.3) | 53 (98.1) | 29 (56.9) | 50 (98.0) |

Results shown are n (%).

Figure 1.

Results of the pre and post evaluation questionnaires used in HCPs who attended the HCV Masterclass in Bucharest.

Discussion

Key findings

The Hepcare Europe Masterclass Symposium series highlights the benefits of educational seminars as a way of delivering current best practice in the treatment of hepatitis C to a multidisciplinary audience in an efficient and cost-effective way.

In Bucharest, the pre-skills assessment and post-skills assessment showed an improvement in knowledge of HCV care related to HCV modes of transmission, drug use and HCV/DAA treatment, as well as extrahepatic manifestations of HCV and HCV prevalence among patients with high-risk behaviours. Almost all participants concluded that socio-economic conditions and poor involvement of local authorities are the main barriers to treatment and underlined the importance of a multidisciplinary approach. Owing to the cumulative efforts of the HepCare team and other physicians involved in HCV management, structural barriers (disease and laboratory) to HCV treatment were removed in Romania in September 2018.

In Dublin 100% of participants ‘strongly agreed’ or ‘agreed’ that the Masterclass helped them ‘appreciate the role of primary care’ and ‘secondary care’ in the ‘management of patients with HCV’. In regard to making an integrated model of care happen in practice, 100% of participants acknowledged the importance of a ‘designated nurse to liaise with hospital services’.

Comparison with existing literature

The feedback from the Masterclass series highlights the need for multidisciplinary cooperation in optimizing HCV care. Data from the literature indicate the success of multidisciplinary models in enhancing treatment outcomes in the field of diabetes,9 HIV/HCV comorbidiy10 and oncology.11 The pivotal role of a liaison nurse in the HCV cascade of care was highlighted in the feedback forms from the Masterclasses, and this is supported in previous research outlining the central role of liaison nurses in HCV treatment to enhance patient access to treatment, and improve adherence rates to treatment.12 Furthermore, research evaluating the effectiveness of a nurse model in caring for prison inmates with HCV witnessed a 69% sustained virological response rate amongst prisoners on treatment.13

The findings associated with the Masterclass series are consistent with current literature, underlining how the use of didactic video, presentations, discussions and workshops have great potential in educating HCPs, improving knowledge and enhancing collaboration.11,14,15 Research indicates that a key barrier to the implementation of a variety of medical educational interventions is a lack of time;16 in contrast, however, the engagement with educational sessions tends to be more positive.17 The educational sessions were concise and brief, with the aim of delivering a maximum amount of relevant, up-to-date information within a minimum time, increasing acceptability and accessibility of the seminar for professionals.

Research suggests that cost-effectiveness, efficiency and optimal delivery of educational seminars to HCPs and SCPs can be further developed by the use of webinars to amalgamate information on an electronic platform that is accessible to medical students and professionals.15,18 As such, based on the feedback from the Masterclass series in Dublin, an online educational webinar was developed aimed at enhancing a multidisciplinary approach to hepatitis C treatment (available at http://www.ucd.ie/medicine/hepcare/oureducation/resources/).

The Bucharest team also created a video containing the most important messages from their Masterclass presentations, the activities performed by mobile teams, as well as the printed educational materials for both patients and HCPs involved in HCV management (available at http://www.spitalulbabes.ro/hepcare-europe-video-heped-d-6-1/).

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is that it highlights the benefits of educational seminars as a way of enhancing knowledge of current best practice in HCV care to a multidisciplinary audience of HCPs and patients in an efficient and cost-effective way. However, the study is also limited in several ways. The findings cannot be generalized over a large group of different HCPs involved in hepatitis C treatment. A formal invitation was sent out to the participants but non-attendance rates were not measured, hence, only ‘enthusiasts’ were likely to have been recruited and participated in the educational symposiums. Furthermore, owing to time constraints a pre-Masterclass skills evaluation did not take place in Ireland, and this should be included in future Masterclasses. Finally, to date no follow-up data have been collected as to whether attendees have put what they learned into practice.

Conclusions

In both Dublin and Bucharest, where DAAs became recently available, there are still important challenges to overcome to ensure patients adhere to treatment pathways right through to elimination of their HCV. Therefore, treatment of HCV needs to incorporate more than just medication; it requires a more holistic approach and recognition of existing barriers such as housing, social support, mental health issues, alcohol and substance use and incarceration.19 This underlines the importance of integrated care that makes use of an efficient and cooperative multidisciplinary team in order to optimize care in the community.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Petre Calistru, Emanoil Ceausu, Simin Florescu, Alma Kosa, Ionut Popa, George Gherlan, Andreea Cazan and Ioan Petre, who helped facilitate the symposia.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Commission through its EU Third Health Programme (Grant Agreement Number 709844) and Ireland’s Health Services Executive.

Transparency declarations

C.O. has served as a paid speaker for Janssen, BMS and Abbvie; has served as an advisory board member for Teva, ViiV, and Gilead, and as a principal investigator on clinical trials supported by ViiV, and as a co-investigator on clinical trials supported by Abbvie and Tibotec. J.S.L. has received non-restricted grants from Gilead, Abbvie and MSD for hepatitis C related educational and research activities. W.C. has been a principal investigator on research projects funded by the Health Research Board of Ireland, the European Commission Third Health Program and Ireland’s Health Services Executive. W.C. has also been a co-investigator on projects funded by Gilead and Abbvie. J.M. has served as an investigator in clinical trials supported by Bristol Myers-Squibb, Gilead and MSD. J.M. has also served as a paid lecturer for Gilead, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, and MSD, and has received consultancy fees from Bristol Myers-Squibb, Gilead and MSD. J.M. has received a grant from the Servicio Andaluz de Salud de la Junta de Andalucia. All other authors: none to declare.

This article is part of a Supplement sponsored by the HepCare Europe Project.

Authors’ contributions

G.M., C.O., W.C. and B.A. led the development of the manuscript with other co-authors contributing specific components. C.O. is principal investigator and conceived the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1. Swan D, Cullen W, Macias J. et al. Hepcare Europe—bridging the gap in the treatment of hepatitis C: study protocol. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 12: 303–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arain A, De Sousa J, Corten K. et al. Pilot study: combining formal and peer education with FibroScan to increase HCV screening and treatment in persons who use drugs. J Subst Abuse Treat 2016; 67: 44–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mateu-Gelabert P, Gwadz MV, Guarino H. et al. The Staying Safe intervention: training people who inject drugs in strategies to avoid injection-related HCV and HIV infection. AIDS Educ Prev 2014; 26: 144–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lubega S, Agbim U, Surjadi M. et al. Formal hepatitis C education enhances HCV care coordination, expedites HCV treatment and improves antiviral response. Liver Int 2013; 33: 999–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grebely J, Knight E, Genoway KA. et al. Optimizing assessment and treatment for hepatitis C virus infection in illicit drug users: a novel model incorporating multidisciplinary care and peer support. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 22: 270–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bluestone J, Johnson P, Fullerton J. et al. Effective in-service training design and delivery: evidence from an integrative literature review. Hum Resour Health 2013; 11: 51.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Légaré F, Politi MC, Drolet R. et al. Training health professionals in shared decision-making: an international environmental scan. Patient Educ Couns 2012; 88: 159–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G. et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 2199–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singh K, Ranjani H, Rhodes E. et al. International models of care that address the growing diabetes prevalence in developing countries. Curr Diab Rep 2016; 16: 69.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Klein SJ, Wright LN, Birkhead GS. et al. Promoting HCV treatment completion for prison inmates: New York State's hepatitis C continuity program. Public Health Rep 2007; 122 Suppl 2: 83–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Widger K, Friedrichsdorf S, Wolfe J. et al. Protocol: evaluating the impact of a nation-wide train-the-trainer educational initiative to enhance the quality of palliative care for children with cancer. BMC Palliat Care 2016; 15: 12.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meyer JP, Moghimi Y, Marcus R. et al. Evidence-based interventions to enhance assessment, treatment, and adherence in the chronic hepatitis C care continuum. Int J Drug Policy 2015; 26: 922–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lloyd AR, Clegg J, Lange J. et al. Safety and effectiveness of a nurse-led outreach program for assessment and treatment of chronic hepatitis C in the custodial setting. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56: 1078–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McCluskey A, Lovarini M.. Providing education on evidence-based practice improved knowledge but did not change behaviour: a before and after study. BMC Med Educ 2005; 5: 40.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Borgerson D, Dino J.. The feasibility, perceived satisfaction, and value of using synchronous webinars to educate clinical research professionals on reporting adverse events in clinical trials: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2012; 29: 316–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Windt J, Windt A, Davis J. et al. Can a 3-hour educational workshop and the provision of practical tools encourage family physicians to prescribe physical activity as medicine? A pre-post study. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e007920.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Klimas J, Lally K, Murphy L. et al. Development and process evaluation of an educational intervention to support primary care of problem alcohol among drug users. Drugs Alcohol Today 2014; 14: 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- 18.ePrePP (Preparation for Professional Practice): Collaborative Creation of a Suite of Digital Tools to Prepare Healthcare Students for Professional Practice,2015. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UClbc8S_kWkZBBuI_F0y3Jrw/videos.

- 19. Mason K, Dodd Z, Sockalingam S. et al. Beyond viral response: a prospective evaluation of a community-based, multi-disciplinary, peer-driven model of HCV treatment and support. Int J Drug Policy 2015; 26: 1007–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.