Abstract

The esterase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus is a monomeric protein with a molecular weight of about 35.5 kDa. The enzyme is barely active at room temperature, displaying the maximal enzyme activity at about 80°C. We have investigated the effect of the temperature on the protein structure by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. The data show that between 20°C and 60°C a small but significant decrease of the β-sheet bands occurred, indicating a partial loss of β-sheets. This finding may be surprising for a thermophilic protein and suggests the presence of a temperature-sensitive β-sheet. The increase in temperature from 60°C to 98°C induced a decrease of α-helix and β-sheet bands which, however, are still easily detected at 98°C indicating that at this temperature some secondary structure elements of the protein remain intact. The conformational dynamics of the esterase were investigated by frequency-domain fluorometry and anisotropy decays. The fluorescence studies showed that the intrinsic tryptophanyl fluorescence of the protein was well represented by the three-exponential model, and that the temperature affected the protein conformational dynamics. Remarkably, the tryptophanyl fluorescence emission reveals that the indolic residues remained shielded from the solvent up to 80°C, as shown from the emission spectra and by acrylamide quenching experiments. The relationship between enzyme activity and protein structure is discussed. Proteins 2000;38:351–360.

Keywords: infrared, protein structure, thermophilic enzyme, frequency-domain fluorometry, anisotropy decays, protein stability

INTRODUCTION

The structural, functional features of enzymes isolated from thermophilic bacteria have attracted the interest of many researchers in the last two decades. Thermophilic enzymes possess unusual stability towards the denaturing action of heat and chemical protein denaturants. As a result, they can be used as biocatalysts under rather harsh environmental conditions.1 Moreover, their unusual properties prompted their use as protein models for addressing a number of fundamental problems in understanding the determinants of protein structure.2

Despite the many studies on thermophilic enzymes and proteins,3–5 relatively few studies have been carried out on the conformational dynamics of very stable enzymes. Evidence from hydrogen-deuterium exchange shows that at a given temperature, thermostable enzymes are less flexible than thermolabile ones, and more specifically that enzymes from thermophilic microorganisms are, at room temperature, less flexible than those from mesophiles.6–8 Moreover, recently Tang and Dill have studied the temperature-induced fluctuations in the lattice model, and concluded that proteins having greater stability tend to have fewer large fluctuations, and hence lower flexibility.9

Time-resolved fluorescence is one of the most common spectroscopic methods used to elucidate the structural and dynamic aspects of the protein structure.10 Tryptophan residues in proteins are often used as probes to monitor the structural changes of the macromolecules in solution.10 However, the photo-physics of indolic residues in proteins is complex, involving multiple non-radiative pathways, such as excited-state proton transfer, excited-state electron transfer and solvent quenching.10–12

The esterase gene from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus (AFEST), showing homology with the mammalian hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL)-like group of the esterase/lipase family,13 has been overexpressed in Escherichia coli as a monomeric protein with a molecular weight of about 35.5 kDa. The enzyme is scarcely active at temperature as low as 10°C where about 10% of the maximal activity at 80°C is displayed.14 Moreover, it contains three tryptophan residues, localized at the positions 139, 209, and 218 in the protein primary structure. A 3D model has been constructed (Manco G., personal communication) on the basis of the recently solved structure of the homologous protein from Bacillus subtilis15 which indicates that the enzyme possesses the α/β hydrolase fold typical of the esterase/lipase family.16

Here we report the effect of the temperature on the structural features of AFEST. In particular, we used Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) to gain information on the stability of the secondary structure of the protein. The conformational dynamics of AFEST were monitored by frequency-domain intensity and anisotropy decays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Deuterium oxide (99.9% 2H2O) was purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI). All the other chemicals were commercial samples of the purest quality.

Preparation and purification of AFEST

The purification of homogeneous AFEST was reported previously.14 Typically the specific activity of the homoge neous enzyme was approximately 3,000 U/mg at 80°C by using 0.2 mM p-nitrophenyl exanoate as substrate in a mixture of 40 mM Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4/ 0.09% (w/v) arabic gum/ 0.36% (v/v) Triton X-100/ 2% (v/v) propan-2-ol (pH 7.1). Protein samples were concentrated and placed in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT buffer, pH 7.1 by means of an Amicon ultrafiltration apparatus equipped with PM-30 membranes.

Protein Assay

The protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford,17 with bovine serum albumin as standard.

Preparation of Samples for Infrared Measurements

Typically, 1.5 mg of protein dissolved in 500 μl of buffer used for AFEST purification were centrifuged in a “30 K microsep” micro concentrator (Dasit) at 3000 × g and 4°C and concentrated into a volume of approximately 40 μl. Then 300 μl of 50 mM Tris-HCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT buffer, prepared in 1H2O pH 7.1 or 2H2O p2H 7.1, were added and the sample concentrated again. This procedure was repeated several times in order to completely replace the buffer, in which the protein was originally dissolved, with the Tris buffer. The washings took 24 hours, which is the time of contact of the protein with the 2H2O medium prior FT-IR analysis. In the last washing the protein sample was concentrated to a final volume of approximately 40 μl and used for the infrared measurements.

Infrared Spectra

The concentrated protein samples were placed in a thermostated Graseby Specac 20500 cell (Graseby-Specac Ltd, Orpington, Kent, UK) fitted with CaF2 windows and 6 or 25 μm spacers for measurements in 1H2O or 2H2O medium, respectively. FT-IR spectra were recorded by means of a Perkin-Elmer 1760-x Fourier transform infrared spectrometer using a deuterated triglycine sulphate detector and a normal Beer-Norton apodization function. At least 24 hr before, and during data acquisition the spectrometer was continuously purged with dry air at a dew point of −40°C. Spectra of buffers and samples were acquired at 2 cm−1 resolution under the same scanning and temperature conditions. Typically, 256 scans were averaged for each spectrum obtained at 20°C, while 16 scans were averaged for spectra obtained at higher temperatures. In the thermal-denaturation experiments, the temperature was raised in 5°C steps from 20°C to 95°C. Before the spectrum acquisition, samples were maintained at the desired temperature for the time necessary for the stabilization of temperature inside the cell (6 min). The deconvoluted parameters for the amide I band were set with the half-bandwidth at 18 cm−1 and a resolution enhancement factor of 2.5.18

Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Frequency-domain measurements were performed as previously described.19 The excitation source was a synchronously-pumped frequency-doubled rhodamine 6 G dye laser at 298 nm. The Trp emission was selected by a Corning 7–60 and 345 nm cut off filters. All intensity decay measurements were performed with magic angle polarizer conditions. Temperature of the sample compartment was stabilized with the precision better than ±0.5°C using Lauda RMT6 waterbath.

Intensity decays were analyzed in terms of the multiexponential model,

| (1) |

where a4 are the pre-exponential factors, τi the decay times, and Σαi = 1.0. The fractional intensity fi of each decay time is given by

| (2) |

and the mean lifetime is

The time fluorescence anisotropy was obtained by a least-squares analysis of the differential polarized phase and modulation ratio19,20

| (3) |

where gk are fractional amplitudes, rotational correlation times, and Σgk = 1.0. For calculations of the goodness-of-fit parameter the uncertainties in the differential phase angles and modulation ratios were assumed to be δΔ = 0.2 deg and δΔ = 0.005, respectively during the non-linear least square analysis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Absorbance Spectra

Figure 1 shows the original absorbance spectra of AFEST in H2O (continuous line) and in 2H2O (dashed line). The exchange of H2O with 2H2O causes a change of the shape of the amide I band and a downshift in wavenumber of its maximum from 1655 cm−1 to 1639.8 cm−1. The 1H/2H exchange also causes a decrease of the amide II band (1549.2 cm−1) intensity and the extent of exchange gives information on the accessibility of the solvent (2H2O) to the protein.21 Since the spectrum of the protein in 2H2O shows a residual amide II band (1551.3 cm−1) it is clear that, upon a contact of the protein with 2H2O for 24 hr at 4°C (see Materials and Methods), the amide hydrogens were not completely exchanged with deuterium. The 1580.9 cm−1 and 1515.6 cm−1 bands are due to amino acid side chain absorption.22

Fig. 1.

Original absorbance spectra of AFEST at 20°C upon subtraction of buffer. Continuous and dashed lines represent the spectra of protein in H2O and 2H2O, respectively. The spectra were normalized to the amide I band intensity.

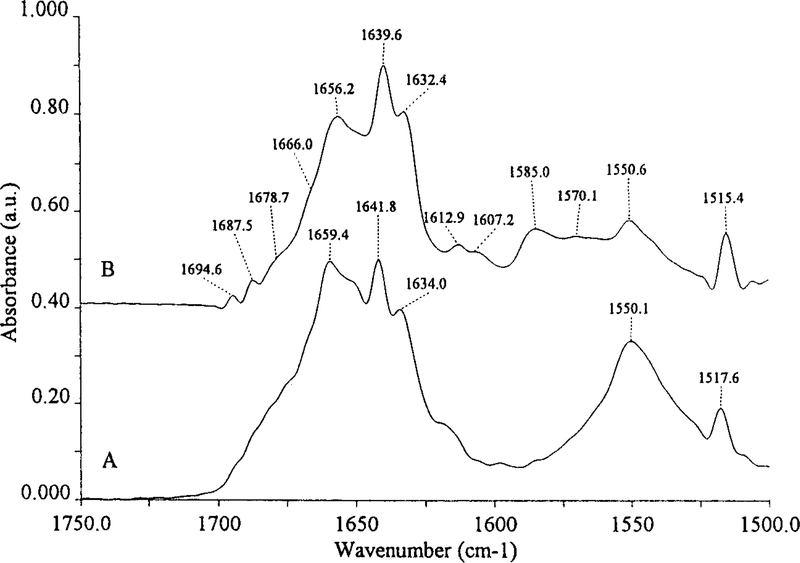

Deconvolved Spectra and Secondary Structure

The deconvolved spectra of AFEST in H2O and 2H2O are shown in Figure 2, traces A and B, respectively. These resolution-enhanced spectra show the amide I (1700–1600 cm−1 range) components due to a particular secondary structure. In H2O (spectrum A) three main bands are well visible. In the spectrum (B) these bands are located to a lower wavenumber and can be assigned to α-helix (1656.2 cm-1) and β-sheets (1639.6 cm−1 and 1632.4 cm−1).23 The asymmetry of the 1656.2 cm−1 band indicates the presence of another not well visible component close to 1647cm−1 due to unordered structures.23

Fig. 2.

Deconvolved spectra of AFEST at 20°C in H2O (A) and in2H2O (B).

The 1666 cm−1 and 1678.7 cm−1 bands can be assigned to turns, the 1694.6 cm−1 to β-sheets and the 1687.5 cm−1 to turns and/or β-sheets.24 The bands below 1615 cm−1 are due to amino acid side chain absorption22 while the 1550.6 cm−1 peak represents the residual amide II band.21

Thermal Denaturation

The increase in temperature caused changes in the amide I’ band reflecting different phenomena. In particular, Figure 3A shows that between 20°C and 60°C a small but significant decrease of the β-sheet bands (1639.6 cm−1 and 1632.4 cm−1 in Fig. 2) occurred, indicating a partial loss of β-sheets. This finding could suggest the presence of a temperature-sensitive β-sheet. The increase in temperature from 60°C to 98°C induced a decrease of α-helix and β-sheet bands which, however, are still visible at 98°C indicating that at this temperature the secondary structure elements of the protein are only partially lost. At 98°C the band close to 1618 cm−1 reflects protein intermolecular interactions (aggregation) brought on by the thermal denaturation.25 Keeping the protein at 98°C, for the time indicated in the Figure 3B (and Fig. 3 legend), results in a further protein denaturation as revealed by the decrease in intensity of the α-helix and β-sheet bands and by the increase in intensity of the band close to 1617 cm−1 due to aggregation. However, after 36 min at 98°C the spectrum still shows α-helix and β-sheet bands indicating an uncomplete denaturation. In order to check the loss of secondary structure at low temperatures, we calculated the difference spectra between two original absorbance spectra recorded at 5°C interval temperatures (Fig. 4). The negative bands between 1700–1600 cm−1 represent a lower content of a particular secondary structure in the sample recorded at higher temperature.26 In particular, the two negative bands at 1637.8 cm−1 and 1629.7 cm−1 in the spectrum (25–20°C) indicate that even the increase of temperature from 20°C to 25°C causes a loss of β-sheets. The loss of β-sheets belonging to the 1637.8 cm−1 and 1629.7 cm−1 bands is observed till at temperature of 50°C (spectrum 50–45°C) although at this temperature the negative 1637.8 cm−1 band is slightly visible. On the contrary the other β-sheet negative band (1631 cm−1) is visible till 60°C and then disappears in the spectra (6560), (70–65), and (75–70). These data support the idea of a domain with β-sheets particularly sensitive to temperature. On the other hand when the temperature is further raised a negative band close to 1640 cm−1, representing the unfolding of the more temperature resistant β-sheets, clearly appears in the (85–80°C) spectrum and becomes more intense at higher temperatures. Between 90–85°C a loss of turns starts to occur, as revealed by the negative 1664.4 cm−1 band. However, because of its broadness this band could also contain information on α-helix unfolding which is much more marked in spectra (95–90) and (98–95) as revealed by the negative bands at 1661.7 cm−1 and 1659.1 cm−1, respectively. The negative band at 1556.3 cm−1 in the (25–20°C) spectrum is shifted to 1544.6 cm−1 in the (98–95°C) spectrum and it mainly represents a further 1H/2H exchange caused by the increase of temperature and by protein unfolding.26 The positive peaks at 1618.4 cm−1 and 1684.3 cm−1 represent protein aggregation brought on by thermal denaturation21 that significantly starts at (90–85°C).

Fig. 3.

Deconvolved spectra of AFEST as a function of the temperature (A) and as a function of time at 98°C (B). The spectra, obtained in H2O, were collected from 20°C to 95°C in 5°C steps (see Materials and Methods). A reports the spectrum at 20°C and the spectra from 60 to 98°C. B: the protein was maintained at 98°C for 6 min and then the spectrum was collected. The other spectra were collected upon maintaining the protein at 98°C for a total time of 16, 26, and 36 min.

Fig. 4.

Difference spectra between two original absorbance spectra obtained in H2O at different temperatures. Difference spectra were originated by making the difference between two spectra obtained at the temperature reported in the Figure.

The thermal denaturation of the protein was also followed by monitoring the amide I’ bandwidth as a function of the temperature,27 and at 98°C as a function of the time. When a protein undergoes thermal denaturation, a sharp increase of the amide I band width is observed at Tm.27 Our results do not show such increase indicating that at 98°C the secondary structure of the protein is still stable. However, a small but continuous increase in the width was observed even at low temperatures (data not shown), indicating small conformational changes occurring at low temperatures, and further supporting the above mentioned findings.

Fluorescence Analysis

Figure 5 shows the fluorescence emission spectra of AFEST at 25°C, 45°C, 65°C and 80°C as well as the spectrum of N-acetyltryptophanylamide (NATA) at 25°C. The spectra were normalized to 1 as regard the fluorescence intensity. The AFEST emission spectrum at 25°C displays a maximum at 337 nm. The position of the emission maximum is blue-shifted compared with the emission maximum of NATA, suggesting that the protein fluorescence emission arises from indolic residues that are partially buried in the protein matrix.28 Figure 5 also shows AFEST spectra at 45°C, 65°C and 80°C. The spectra at 45°C and 65°C completely overlay the spectrum at 25°C, and the AFEST spectrum at 80°C still displays an emission maximum centered at 337 nm. Also shown for comparison is the emission spectrum of NATA, which displays an emission maximum near 353 nm. These spectra demonstrate that the tryptophan residues in AFEST remain in a protected environment even at 80°C. The inset of Figure 5 shows the effect of temperature on AFEST and NATA fluorescence intensity. Both the AFEST and NATA fluorescence intensities linearly decrease with temperature increase. The emission intensity of AFEST decreases with increasing temperature, but to a smaller extent than NATA, supporting our suggestion of a protected tryptophan environment from 25 to 80°C.

Fig. 5.

Fluorescence emission spectra of AFEST (at different temperatures) and NATA (at 25°C). The spectra were normalized to 1 as regard the fluorescence emission. The excitation was at 295 nm. The absorbance of the protein and NATA solutions was below 0.1. The protein concentration was 0.05 mg/ml.

In order to estimate the extent of tryptophan shielding from the solvent we examined collisional quenching by acrylamide. Acrylamide is a highly water soluble and polar substance which does not penetrate the hydrophobic interior of proteins. Figure 6 depicts the effect of acrylamide on AFEST fluorescence emission at 25°C, 65°C and 85°C. The addition of acrylamide to the protein solution at 25°C results in a Stern-Volmer plot curved downward, suggesting that at this temperature some of AFEST indolic residues might be almost completely buried in the protein matrix. The calculated KSV and kq are 3.5 M−1 and 1.1 × 10gM−1 sec−1, indicating that AFEST indolic residues are about 10% accessible to the solvent. The addition of acrylamide to the enzyme solution at 65°C and 85°C results in linear Stern-Volmer’s plots. The calculated KSV constants at 65°C and 85°C are about 3.5 M−1 at both temperatures. The quenching rate constants (kq) at 65°C and 85°C are 1.8 × 109 M−1 sec−1and 2.3 × 109 M−1 sec−1, respectively. These results indicate that the protein tryptophan residues are shielded from the solvent even at high temperature (about 20% of the AFEST indolic residues are accessible to the solvent at 85°C), suggesting that AFEST structure is still well conserved at 85°C.29–32

Fig. 6.

Effect of acrylammide on AFEST fluorescence emission at different temperatures. The Stern-Volmer plots were calculated according to Eftink.29,30

The intensity decays of the intrinsic fluorescence of AFEST were measured using the frequency-domain method.33 The data were analyzed in terms of the multiexponential models34 and are shown in Figure 7. Figure 8 shows the temperature dependence of AFEST fluorescence decay parameters. In all cases, the best fits were obtained using the three exponential model, characterized by reduced values that were much lower than those obtained with simpler models (data not shown). The mean lifetime values of AFEST at 25°C, 45°C, 65°C, and 85°C are 3.2 ns, 2.7 ns, 2.0 ns, and 1.4 ns, respectively. AFEST at 25°C displays three lifetime components at 0.72 ns (τ1), 2.5 ns (τ2) and 7.7 ns (τ3). The middle-lived component (τ2) is almost coincident with the typical lifetime value observed for the monomeric tryptophanyl residue,10 while the long-lived component (τ3) can be ascribed to tryptophan residues located in compact homogeneous, partly buried and/or unrelaxed interiors of protein matrix.10 Increasing the temperature to 45°C resulted in a decrease of the middle- and long-lived components to 2.1 ns and 7.0 ns, respectively. The short-lived component (τ1) shifted to 0.58 ns. A further temperature increase to 65°C caused a markedly decrease of the long-lived component to 5.9 ns, leaving the short and middle-lived components almost unchanged. Finally, at 85°C the protein displays the lifetime components at 0.55 ns 1.8 ns and 4.3 ns, whose fluorescence intensity fractions are 0.10, 0.33 and 0.57, respectively.

Fig. 7.

Frequency dependence of the phase shift and demodulation factors of AFEST fluorescence emission at the indicated temperatures. The solid lines represent the best triple-exponential fits. Fluorescence was excited by a frequency-doubled rhodamine 6G dye laser at 298 nm and the absorbance of the enzyme solution was below 0.1 at the excitation wavelength. Emission was selected by a Corning 7–60 and cut-off 345 nm filters. The protein concentration was 0.05 mg/ml.

Fig. 8.

Temperature dependence of AFEST fluorescence emission decay parameters. The experimental conditions were as described in Figure 7.

The frequency-domain anisotropy decays of AFEST are shown in Table I. The best fits were obtained by the two exponential model. At 25°C, the two-exponential anisotropy decays indicate both local motions of AFEST tryptophanyl residues and flexibility degree of the side chains of the macromolecule. The short correlation time at 0.17 ns is associated with the local freedom of the tryptophanyl residues, as described in several studies of anisotropy decays of proteins.35–38 The longer correlation time above 25 ns can be associated both to the overall rotation of the protein and to segmental motions of the side chains of AFEST. When the temperature is increased both the short and the long correlation times became shorter, suggesting a gradual increase of the overall flexibility of the protein structure. This conclusion is supported by the gradual increase in the fraction of the shortest correlation time.

TABLE I.

Fluorescence Anisotropy Decays of AFEST at Different Temperatures

The observed changes in the anisotropy decays induced by the temperature suggest that the protein structure is more flexible at high temperature, and in turn that the observed increase in the enzyme activity at elevated temperature can be related to an increase in the protein flexibility.

CONCLUSIONS

Understanding the dynamics features of proteins is of fundamental importance to shed light on the relationship structure-function in proteins, and in turn to determine the influence that the polypeptide chain exerts on the active site. Biological activity and native structure of a protein are strictly linked: small structural alterations in the macromolecule may result in profound effects on the protein activity.

In this study we have investigated the effect of temperature on the structure of the hyperthermophilic esterase from the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Usually, enzymes isolated from thermophilic microorganisms display the maximal enzymatic activity near to the temperature of the microorganism’s growth from which they have been isolated, being almost inactive at room temperature. It is therefore of interest to compare the properties of protein at ambient and elevated temperatures.

Taken together, our FT-IR and fluorescence data point out that the temperature affects both the secondary and the three-dimensional organization of AFEST. In particular, the FT-IR data show that between 20°C and 60°C a small but significant decrease of the β-sheet bands (1639.6 cm−1 and 1632.4 cm−1 in Fig. 2) occurred, indicating a partial loss of β-sheet structure. This finding could suggest the presence of a temperature-sensitive β-sheet involved in the functional features of the enzyme: the enzyme activity increases with the temperature increase, being the enzyme scarcely active at room temperature and displaying the maximal activity at 80°C.14

Additionally, the fluorescence and anisotropy decays data show that the protein structure is still well conserved at high temperature and that elevated temperature induces a more flexible protein structure which may be also responsible of the increased activity of the enzyme. Our results seem to support the conclusions of Tang and Dill on the lattice model,19 that is, protein flexibility may be correlated to enzyme activity. In other words, if greater stability implies less flexibility, then cooling a thermophilic enzyme to near room temperature may freeze out the fluctuations that are necessary for catalytic activity. Moreover, our data are also in good agreement with several investigations on the conformational dynamics of thermophilic enzymes. In particular, recently it has been suggested that the thermophilic β-glycosidase from the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus possesses a quite rigid structure at room temperature (at which it is almost inactive), and, on the contrary, it is quite flexible at the temperature at which it displays the maximal enzymatic activity.3–5 Moreover, Varley and Pain investigated the relationships between stability, dynamics, and activity in 3-phosphoglycerate kinases from yeast and the extreme thermophilic microorganism Thermus thermophilus.8 They found that while at a given temperature the thermophilic protein was more stable, its conformational dynamics as well as the specific activity were both lower than for mesophilic enzyme. As the temperature was increased, the thermodynamic stability of the thermophilic protein approached that of the mesophilic one at its working temperature. The conformational dynamics and the specific activity of the thermophilic enzyme increased up to the physiological operational temperature, and they became similar to those of the mesophilic enzyme at its operational temperature. These results suggested a direct relationship between thermodynamic stability, conformational dynamics and specific activity in globular proteins.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: European Community “Extremophiles”; Grant sponsor: National Center for Research Resource, National Institutes of Health; Grant number: RR-08119.

Sabato D’Auria’s present address is: Institute of Protein Biochemistry & Enzymology, C.N.R., Via Marconi, 10 Napoli, Italy.

Abbreviations:

- FT-IR

Fourier transform infrared

- Amide I’

amide I band in 2H2O medium

- NATA

N-acetyltryptophanylamide

- Tm

temperature of maximum denaturation

- AFEST

esterase from Archaeoglobus fulgidus

REFERENCES

- 1.Cowan DA. Enzymes from thermophilic archaebacteria: current and future applications in biotechnology. Biochem Soc Symp 1992;58:149–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van den Burg B, Vriend G, Veltman OR, Vemma G, Eijsink VGH. Engineering an enzyme to resist boiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1998;95:2056–2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Auria S, Moracci M, Febbraio F, Tanfani F, Nucci R, Rossi M. Structure-function studies on β-glycosidase from Sulfolobus solfataricus. Molecular bases of thermostability. Biochimie 1998;80: 949–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Auria S, Nucci R, Rossi M, et al. β-Glycosidase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus: structure and activity in the presence of alcohols. J Biochem 1999; 126:545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Auria S, Rossi M, Nucci R, Irace G, Bismuto E. Perturbation of conformational dynamics, enzymatic activity and thermostability of β-glycosidase from archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus by pH and sodium dodecyl sulfate. Proteins 1997;27:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniel RM, Dines M, Petach HH. The denaturation and degratation of stable enzymes at high temperature. Biochem J 1996;317:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiller R, Zhon ZH, Adams MMW, Englander SW. Stability and dynamics in a hyperthermophilic protein with melting point close to 200°C. Proc NatlAcad Sci 1997;94: 11329–11332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varley PG, Pain RH. Relation between stability, dynamics and enzyme activity in 3-phosphoglycerate kinases from yeast and Thermus thermophilus. J Mol Biol 1991;220:531–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang KES, Dill KA. Native protein fluctuations: the conformational motions temperature and the inverse correlation of protein flexibility with protein stability. J Biomol Struct Dyn 1998;16:397–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lakowicz JR. In: Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. New York: Plenum Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eftink MR, Jia Y, Hu D, Ghiron C. Fluorescence studies with tryptophan analogues: excited state interactions involving the side chain amino groups. J Phys Chem 1995;99:5713–5723. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong-Tao Y, Vela M, Fronczek F, Mc Laughim M, Barkley MD. Micro-environmental effects on the solvent quenching rate in constrained tryptophan derivates. J Am Chem Soc 1995;117:348–358. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manco G, Febbraio F, Rossi M. In: Ballesteros A, Plou FJ, Iborra JL, Halling PJ, editors. Progress in biotechnology Volume 15: Stability and stabilization of biocatalysts. New York: Elsevier Scientific; 1998. p 325–330. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manco G, Giosue’ E, D’Auria S, Herman P, Carrea G, Cloning Rossi M., expression and characterization of a thermophilic esterase from Archeoglobus fulgidus. Arch Bioch Biophys 1999; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei Y, Contreras JA, Sheffield P, Osterlund T, Derewenda U, Kneusel RE, Matern U, Holm C, Derewenda ZS. Crystal structure of brefeldina esterase, a bacterial homolog of the mammalian hormone-sensitive lipase. Nat Struct Biol 1999;6: 340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cygler M, Schrag JD, Sussman JL, Harel M, Silman I, Gentry MK, Doctor BP. Protein Sci 1993;2:366–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilising the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 1976;72:248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee DC, Haris PI, Chapman D, Mitchell R. Determination of protein secondary structure using factor analysis of infrared spectra. Biochemistry 1990;29:9185–9193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lakowicz JR, Gryczynski I. Frequency-domain fluorescence spectroscopy. In: Topics in fluorescence spectroscopy, Volume 1: Techniques. NewYork: Plenum Press; 1991. p 293–335. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lakowicz JR, Cherek H, Kusba J, Gryczynski I, Johnson ML. Review of fluorescence anisotropy decay analysis by frequency-domain fluorescence spectroscopy. J Fluoresc 1993;3: 103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osborne HB, Nabedryk-Viala E. Infrared measurements of peptide hydrogen exchange in rhodopsin. Methods Enzymol 1982;88: 676–680. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chirgadze YN, Fedorow OW, Trushina NP. Estimation of amino acid residue side-chain absorption in the infrared spectra of protein solutions in heavy water. Biopolymers 1975;14:679–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arrondo JLR, Muga A, Castresana J, Goni FM. Quantitative studies of the structure of proteins in solutions by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Prog Biophys Molec Biol 1993;59: 23–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krimm S, Bandekar J. Vibrational spectroscopy and conformation of peptides, polypeptides, and proteins. Adv Protein Chem 1986;38: 181–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Auria S, Barone R, Rossi M, Nucci R, Barone G, Fessas D, Bertoli E, Tanfani F. Effects of temperature and SDS on the structure of ß-glycosidase from the thermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus BiochemJ 1997;323:833–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banecki B, Zylicz M, Bertoli E, Tanfani, F. Structural and functional relationships in DnaK and DnaK756 heat-shock proteins from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 1992;267:25051–25058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanfani F, Kulawiak D, Kossowska E, Purzycka Preis J, Zydowo MM, Sarkissowa E, Bertoli E, Wozniak M. Structural-functional relationships in pig hearth AMP-deaminase in the presence of ATP, orthophosphate, and phosphatidate bilayers. Mol Genet Metabol 1998;65:51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gopalan V, Golbik R, Schreiber A, Fersth AR. Fluorescence properties of a tryptophan residue in an aromatic core of the protein subunit of ribonuclease P from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 1997;267:765–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eftink MR, Ghiron CA. Exposure of tryptophanyl residues in Proteins. Quantitative determination by fluorescence quenching studies. Biochemistry 1976;15:672–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eftink MR, Ghiron CA. Fluorescence quenching of indole and model micelle systems. J Phys Chem 1976;80:486–493. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eftink MR. In: LakowiczJR, editor Topicsin fluorescence spectroscopy, Volume III New York: Plenum Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 32.D’Auria S, Nucci R, Rossi M, Gryczniski I, Gryczniski Z, Lakowicz JR. The ß-glycosidase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus: enzyme activity and conformational dynamics at temperatures above 100°C. Biophys Chem 1999;81:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lackzo G, Gryczyniski I, Wiczk W, Malak H, Lakowicz JR. A 10 GHz frequency-domain fluorometer. Rev Sci Instrum 1990;61: 9231–9237. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lakowicz JR, Lackzo G, Cherek H, Gratton E, Limkeman H. Analysis of fluorescence decay kinetic from variable frequency phase shifts and modulation data. Biophys J 1984;46:463–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lakowicz JR, Cherek H, Maliwal B, Gratton E. Time-resolved fluorescence anisotropies of fluorophores in solvents and lipid bilayers obtained from frequency-domain phase modulation fluorometry. Biochemistry 1985;24:376–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lakowicz JR, Gryczniski I, Cherek H, Lackzo G. Anisotropy decays of indole, mellitin monomer and mellitin tetramer by frequency-domain fluorometry and multi-wavelength global analysis. Biophys Chem 1991;39:241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lakowicz JR, Gryczniski I, Szmacinski H, Cherek H, Joshi N. Anisotropy decays of single tryptophan proteins measured by GHz frequency-domain fluorometry with collisional quenching Eur J Biophys 1991;19:125–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eftink MR, Selvidge LA, Callis PR, Rehms AA. Photophysics of indole derivatives: experimental resolution of 1La and 1Lb transitions and comparison with theory. J Phys Chem 1990;94:3469–3479. [Google Scholar]