Abstract

Background

Children who are securely attached to at least one parent are able to be comforted by that parent when they are distressed and explore the world confidently by using that parent as a 'secure base'. Research suggests that a secure attachment enables children to function better across all aspects of their development. Promoting secure attachment, therefore, is a goal of many early interventions. Attachment is mediated through parental sensitivity to signals of distress from the child. One means of improving parental sensitivity is through video feedback, which involves showing a parent brief moments of their interaction with their child, to strengthen their sensitivity and responsiveness to their child's signals.

Objectives

To assess the effects of video feedback on parental sensitivity and attachment security in children aged under five years who are at risk for poor attachment outcomes.

Search methods

In November 2018 we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, nine other databases and two trials registers. We also handsearched the reference lists of included studies, relevant systematic reviews, and several relevant websites

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs that assessed the effects of video feedback versus no treatment, inactive alternative intervention, or treatment as usual for parental sensitivity, parental reflective functioning, attachment security and adverse effects in children aged from birth to four years 11 months.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

This review includes 22 studies from seven countries in Europe and two countries in North America, with a total of 1889 randomised parent‐child dyads or family units. Interventions targeted parents of children aged under five years, experiencing a wide range of difficulties (such as deafness or prematurity), or facing challenges that put them at risk of attachment issues (for example, parental depression). Nearly all studies reported some form of external funding, from a charitable organisation (n = 7) or public body, or both (n = 18).

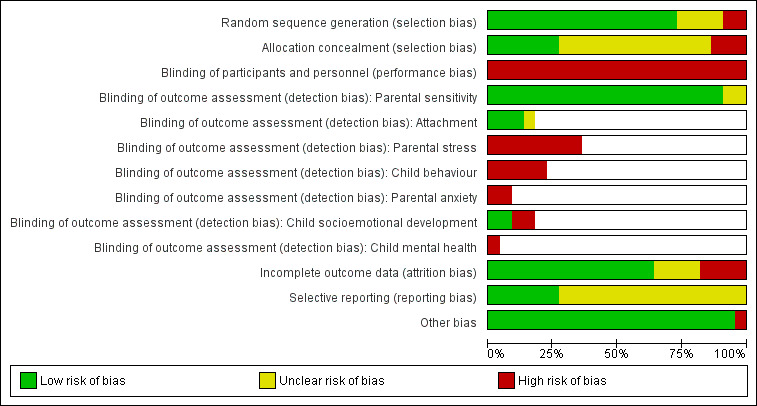

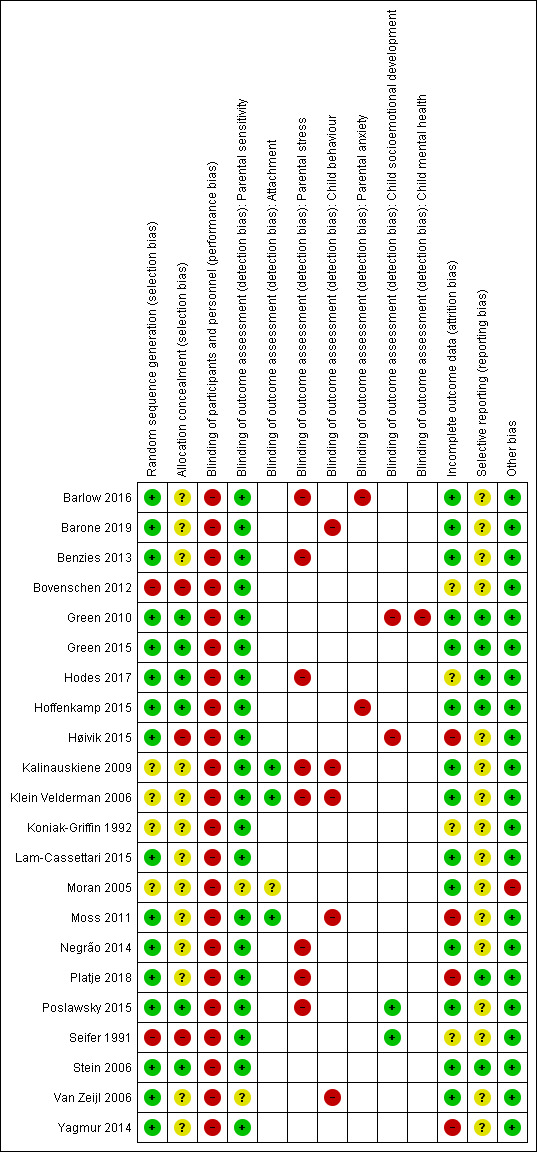

We considered most studies as being at low or unclear risk of bias across the majority of domains, with the exception of blinding of participants and personnel, where we assessed all studies as being at high risk of performance bias. For outcomes where self‐report measures were used, such as parental stress and anxiety, we rated all studies at high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessors.

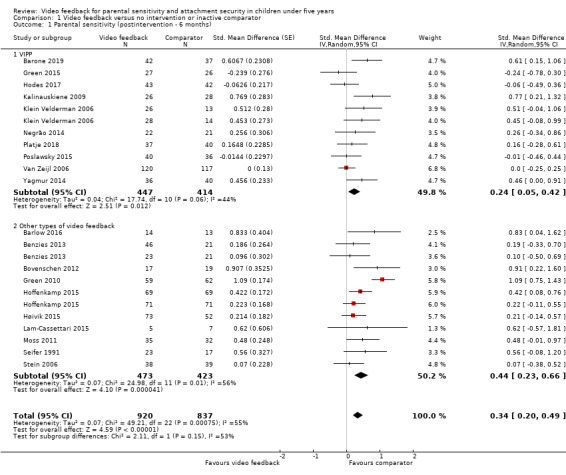

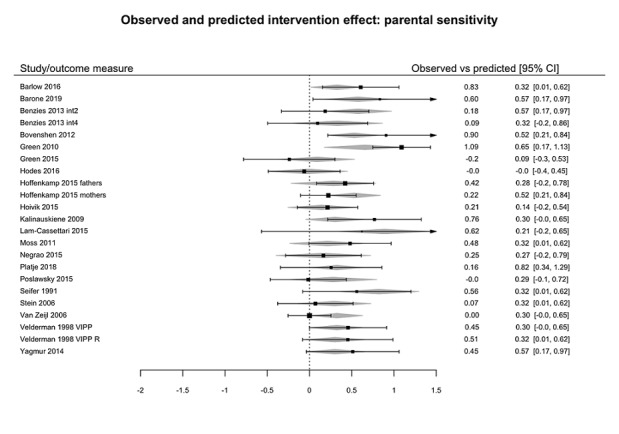

Parental sensitivity. A meta‐analysis of 20 studies (1757 parent‐child dyads) reported evidence of that video feedback improved parental sensitivity compared with a control or no intervention from postintervention to six months' follow‐up (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.34, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.20 to 0.49, moderate‐certainty evidence). The size of the observed impact compares favourably to other, similar interventions.

Parental reflective functioning. No studies reported this outcome.

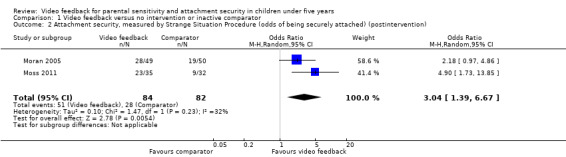

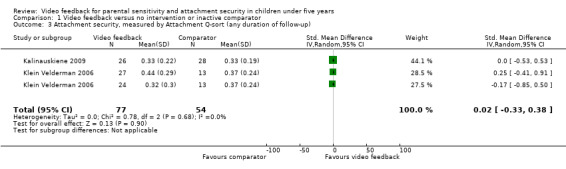

Attachment security. A meta‐analysis of two studies (166 parent‐child dyads) indicated that video feedback increased the odds of being securely attached, measured using the Strange Situation Procedure, at postintervention (odds ratio 3.04, 95% CI 1.39 to 6.67, very low‐certainty evidence). A second meta‐analysis of two studies (131 parent‐child dyads) that assessed attachment security using a different measure (Attachment Q‐sort) found no effect of video feedback compared with the comparator groups (SMD 0.02, 95% CI −0.33 to 0.38, very low‐certainty evidence).

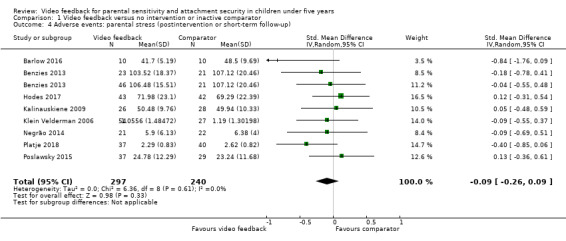

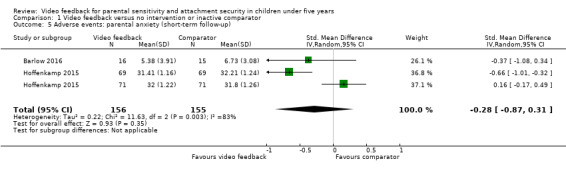

Adverse events. Eight studies (537 parent‐child dyads) contributed data at postintervention or short‐term follow‐up to a meta‐analysis of parental stress, and two studies (311 parent‐child dyads) contributed short‐term follow‐up data to a meta‐analysis of parental anxiety. There was no difference between intervention and comparator groups for either outcome. For parental stress the SMD between video feedback and control was −0.09 (95% CI −0.26 to 0.09, low‐certainty evidence), while for parental anxiety the SMD was −0.28 (95% CI −0.87 to 0.31, very low‐certainty evidence).

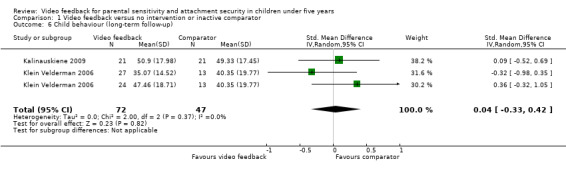

Child behaviour. A meta‐analysis of two studies (119 parent‐child dyads) at long‐term follow‐up found no evidence of the effectiveness of video feedback on child behaviour (SMD 0.04, 95% CI −0.33 to 0.42, very low‐certainty evidence).

A moderator analysis found no evidence of an effect for the three prespecified variables (intervention type, number of feedback sessions and participating carer) when jointly tested. However, parent gender (both parents versus only mothers or only fathers) potentially has a statistically significant negative moderation effect, though only at α (alpha) = 0.1

Authors' conclusions

There is moderate‐certainty evidence that video feedback may improve sensitivity in parents of children who are at risk for poor attachment outcomes due to a range of difficulties. There is currently only little, very low‐certainty evidence regarding the impact of video feedback on attachment security, compared with control: results differed based on the type of measure used, and follow‐up was limited in duration. There is no evidence that video feedback has an impact on parental stress or anxiety (low‐ and very low‐certainty evidence, respectively). Further evidence is needed regarding the longer‐term impact of video feedback on attachment and more distal outcomes such as children's behaviour (very low‐certainty evidence). Further research is needed on the impact of video‐feedback on paternal sensitivity and parental reflective functioning, as no study measured these outcomes. This review is limited by the fact that the majority of included parents were mothers.

Plain language summary

Video feedback for parental sensitivity and child attachment

Background

Children who are securely attached to at least one parent are able to be comforted by that parent when they are distressed and more able to explore the world confidently by using that parent as a 'secure base'. Research suggests that a secure attachment enables children to function better across all aspects of their development. Promoting secure attachment, therefore, is a goal of many programmes that aim to support children and families in the first few years of the child's life. Video feedback involves showing a parent brief moments of videotaped interaction between them and their baby, in order to strengthen their sensitivity to signals from their baby, with the aim of improving attachment.

Review question

To assess the effects of video feedback on parental sensitivity and attachment security in children under five years old who are at risk of poor outcomes, compared to no intervention (no treatment), a mock treatment (such as a phone call) or treatment as usual.

Included studies

This review included 22 studies, made up of 1889 randomised parent‐child pairs or family units. Not all of these could be combined in a meta‐analysis (a statistical method of combining data from several studies to reach a single, more robust conclusion). We combined data from 20 studies (made up of 1757 parent‐child pairs) to examine the effects of video feedback on parental sensitivity. We combined data from fewer studies to look at attachment security, parental stress, parental anxiety and child behaviour.

The included studies were mostly conducted in Canada, the Netherlands, UK and USA. Single studies were conducted in Italy, Germany, Lithuania, Norway and Portugal.

Almost all studies reported some form of external funding, from either a charitable organisation (n = 7) and/or public body (n = 18).

Results

The results show evidence of an improvement in parental sensitivity following the use of video feedback. The results for attachment security were mixed: one meta‐analysis showed that the intervention group were more securely attached, while the second meta‐analysis, which measured the strength of attachment in a different way, showed no evidence of impact. There was no evidence of impact on parental anxiety or stress. No studies measured parental reflective functioning. There was no evidence of impact on child behaviour.

Study certainty

We rated the overall certainty of the evidence (the extent to which we believe that the results are correct or adequate) as moderate for parental sensitivity, and low or very low for the other outcomes. This means that we are reasonably certain that video feedback improves parental sensitivity in the short term, but we are not very certain of its impact on our other findings.

Authors' conclusions

Video feedback may be a helpful method of improving parental sensitivity, but there is currently little or no evidence that it improves child attachment security, parental stress, parental anxiety or child behaviour. More research is needed on the effects of video feedback on other outcomes, including parental reflective functioning, and in fathers.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Video feedback versus no intervention or inactive alternative intervention for parental sensitivity and attachment.

| Video feedback versus no intervention or inactive alternative intervention for parental sensitivity and attachment | ||||||

| Patient or population: parent‐child dyads (including foster or adoptive carers), where the child was aged between birth and four years 11 months (inclusive), and where problems had been identified that were impacting or might impact on the parent's sensitivity Setting: community, hospital outpatient and hospital inpatient Intervention: video feedback Comparison: no intervention or inactive alternative intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no intervention or inactive alternative intervention | Risk with video feedback | |||||

|

Parental sensitivity Follow‐up: postintervention or short‐term follow‐up |

‐ | The mean parental sensitivity score in the intervention group was 0.34 standard deviations higher (0.20 higher to 0.49 higher) | ‐ | 1757 dyads (20 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | Higher scores indicate a better outcome. Effect size of 0.33 standard deviations compares favourably to other similar interventions. |

| Parental reflective functioning | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome. |

|

Attachment security Measured by: Strange Situation Procedure (odds of being securely attached) Follow‐up: postintervention |

Study population | OR 3.04 (1.39 to 6.67) | 166 dyads (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c,d | Higher scores indicate a better outcome. | |

| 341 per 1000 | 612 per 1000 (419 to 776) | |||||

|

Attachment security Measured by: Attachment Q‐sort Follow‐up: postintervention |

The mean attachment security score across control groups ranged from 0.33 to 0.37 (scores can range from + 1.00 to −1.00) | The mean attachment security score in the intervention group was0.02 standard deviations higher (0.33 lower to 0.38 higher) | ‐ | 131 dyads (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c,d | Effect size of 0.02 standard deviations indicates no evidence of effectiveness. |

|

Adverse events: parental stress Follow‐up: postintervention or short term |

‐ | The mean parental stress score in the intervention group was 0.09 standard deviations lower (0.26 lower to 0.09 higher) | ‐ | 537 dyads (8 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | Higher scores indicate a worse outcome. Effect size of 0.09 standard deviations indicates no evidence of effectiveness. |

|

Adverse events: parental anxiety Follow‐up: short term |

‐ | The mean parental anxiety score in the intervention group was0.28 standard deviations lower (0.87 lower to 0.31 higher) | ‐ | 311 dyads (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,d,e | Higher scores indicate a worse outcome. Effect size of 0.28 compares favourably to other similar interventions. |

|

Child behaviour Follow‐up: long term |

‐ | The mean child behaviour score in the intervention group was 0.04 standard deviations higher (0.33 lower to 0.42 higher) | ‐ | 119 dyads (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c,d | Higher scores indicate a worse outcome. Effect size of 0.04 standard deviations indicates no evidence of effectiveness. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to inconsistency: moderate heterogeneity, which was not explained by our subgroup analysis. bDowngraded one level for risk of bias: we rated most domains in the 'Risk of bias' assessment at high or uncertain risk of bias. cDowngraded one level due to imprecision: low number of participants, leading to wide confidence interval. dDowngraded one level due to publication bias: few studies in this review reported this outcome. eDowngraded one level due to inconsistency: high heterogeneity.

Background

Description of the condition

Attachment

A child’s relationship with his or her primary carer is the first, and arguably the most important, relationship formed following birth. The primary carer is normally, but not always, the child's birth mother or father. This emotional bond between a child and their primary caregiver is known as a 'selective attachment' relationship. Attachment is a biobehavioural system that has evolved over time. It is intended to bring about protection in the face of both perceived danger as well as the fear that comes with it (Bowlby 1969). When a child is distressed, he or she is programmed to seek and secure proximity to, and contact with, the primary caregiver (Bowlby 1969). Attachment behaviour may be activated by circumstances internal to the child such as illness, hunger or pain; by separation from the primary caregiver such as when a mother leaves the room or discourages proximity; or by external events that cause distress such as frightening events or rejection by others (Bowlby 1969). Depending on the intensity of the threat, the attachment behaviour may be terminated by the appearance of the caregiver or physical contact with them. The younger the child, or the more serious the threat, the more likely that only physical reassurance and containment will provide comfort. The attachment relationship, therefore, is a dynamic one, in which the child plays an active part (see Shin 2008). It has been described by Zeanah and colleagues as a reciprocal relationship of seeker (child) and provider (parent), the purpose of which is to comfort children when they are upset, support the development of emotional regulation, and offer security (Zeanah 1993).

Children whose caregivers provide sensitive and responsive care develop secure attachments to those carers. Children who experience insensitive, unpredictable or intrusive parenting develop attachments that are insecure, putting them at risk of adverse consequences for a range of aspects of their psychosocial development, including being more reliant on teachers; showing less positive affective expression and impaired social problem‐solving skills; showing more frustration and less persistence; more negative responses to others and less overall social competence (Sroufe 2005). In addition to children being classified as either secure or insecure, they may also be classified as disorganised, when there is evidence of a conflict between wanting to approach and wanting to avoid the caregiver when the attachment system is activated (Main 1990a). Disorganised attachment occurs when children are frightened of the caregiver and have been exposed to a range of anomalous, atypical parent‐child interactions (Madigan 2006). Disorganised attachment is associated with predictors of later psychopathology, including externalising behaviours (Fearon 2010), and personality disorders (Steele 2010). Many studies consider only secure and insecure attachment patterns when classifying children, as these were the attachment patterns that were first described (Weinfield 2004). These studies (carried out in the general population) typically find that approximately 60% of children are securely attached, and the remainder (40%) are insecurely attached (Moullin 2014). For insecurely attached children, 25% learn to avoid their parent when they are distressed (avoidant attachment) and 15% learn to resist the parent, often because the parent responds unpredictably or amplifies their distress (resistant attachment; Moullin 2014). In studies where disorganised attachment has been included, around 40% of disadvantaged children are classified as disorganised (Weinfield 2004), and as many as 80% of abused children receive this classification (Cyr 2010).

Although children usually have a particularly strong bond with one primary caregiver, most have more than one attachment relationship, often with fathers, siblings and grandparents as well as with mothers (see, for example, Hallers‐Haalboom 2014). As such, children can be securely attached to one parent but insecurely attached to another. The role of early relationship experiences and the development of child self‐regulatory skills have been linked to the child’s ability to control behavioural and physiological responses such as anger (Gilliom 2002), aggression (Alink 2009), and anxiety (Hannesdottir 2007).

Caregiver sensitivity

One key predictor of child attachment status is the parent's attachment status (Van Ijzendoorn 1995). The impact of the parent's attachment status on the child's attachment appears to be mediated by parental sensitivity to child cues.

Ainsworth and colleagues defined sensitivity as a mother’s ability to attend and respond to her child in ways that accurately match her child's needs (Ainsworth 1978). Sensitive and responsive parents do the following: notice a child’s signals; interpret these signals correctly; and respond to signals in a timely and appropriate manner (Ainsworth 1974). The concept of sensitivity, therefore, refers not to a specific set of maternal behaviours but to something much more dynamic and relational.

Parental sensitivity can be compromised by a variety of factors. These include social influences such as social isolation (Belsky 2002; Kivijärvi 2004), or domestic violence (Levendosky 2006); psychological factors such as maternal depression (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network 1999; Karl 1995; Murray 1997), or personality disorder (Laulik 2013); maternal history of maltreatment (Pereira 2012), substance dependence (Eiden 2014), low self‐esteem (Leerkes 2002; Shin 2008); or cognitive factors such as maternal preconceptions about parenting (Kiang 2004; Leerkes 2010). Child characteristics can also impact negatively on parental sensitivity, including child prematurity (Singer 1999); the presence of excessive negative child behaviour, such as general distress (Leerkes 2002); and the child's proneness to anger (Ciciolla 2013), and irritability (Van den Boom 1991). Some studies have examined father involvement as a mediator of maternal sensitivity (see, for example, Stolk 2008), whilst others have examined the role of the father as caregiver (see, for example, Pelchat 2003). Comparative research on the relative sensitivity of mothers and fathers is scarce and therefore the findings are somewhat inconclusive; some studies report fathers as less sensitive than mothers (see Hallers‐Haalboom 2014; Heerman 1994; Lovas 2005), while others have found no difference (Pelchat 2003).

Although parental sensitivity has been found to be an important predictor of child attachment security, a systematic review of the antecedents to attachment security suggests that it explains around only one third of the variance (De Wolff 1997). Research has also highlighted the importance of mid‐range contingency (Beebe 2010), and maternal reflective functioning (Slade 2005), or mind‐mindedness (Meins 2001). Mid‐range contingency refers to the ability of the parent to regulate flexibly both their own internal emotional states and their interaction with the baby, and is characterised by moments of synchrony or attunement, followed by rupture and then repair. A study by Beebe 2010 found that interaction that occurred outside this mid‐range, resulting from the parent’s preoccupation either with self‐regulation (e.g. depressed parents) or interactive regulation (e.g. anxious parents), was associated with an insecure or disorganised attachment).

Reflective functioning is a term that describes a parent's ability to comprehend their child's behaviour with regards to their internal mental states (Slade 2005). High reflective functioning correlates with positive maternal parenting traits, such as flexibility and responsiveness. Low reflective functioning can be seen in tandem with negative maternal behaviours, such as withdrawal and intrusiveness (Kelly 2005; Slade 2005). Similarly, mind‐mindedness, which refers to the parent's ability both to understand a young child's state of mind and to respond appropriately, has been associated with behavioural sensitivity and interactive synchrony (Meins 2001), and to better predict attachment security of the child at one year of age than maternal sensitivity (Lundy 2003; Meins 2001; Meins 2012).

Other studies have identified the importance of a range of atypical or anomalous parent‐child interactions characterised as ‘Fr‐behaviours’, which are the behaviours of parents who are either frightened or frightening, or both (Jacobvitz 1997; Main 1990b), or who are hostile and helpless (Lyons‐Ruth 2005). Fr‐behaviours have been described as subtle (e.g. periods of being dazed and unresponsive) or more overt (deliberately frightening children; Lyons‐Ruth 2005), and are strongly associated with disorganised attachment (Madigan 2006).

Description of the intervention

Video feedback is a generic term that refers to the use of videotaped interactions of the parent and child to promote parental sensitivity; it has other names, including Video Interaction Guidance (VIG), Interaction Guidance (IG), Video Home Training (VHT) and Video Feedback Intervention to Promote Positive Parenting (VIPP). Developed by Harrie Biemans and colleagues in the 1980s, video feedback is a relationship‐based parenting intervention that aims to enhance maternal sensitivity at the behavioural level (Kennedy 2010). The core aspects of interventions based on video feedback are as follows.

Video‐recording the parent‐child interaction during play or aspects of daily caregiving.

Editing the recording to select micro‐moments of interaction that demonstrate the child's contact initiatives and examples of the parent's attuned response to these signals.

Parent and 'guider' (the person responsible for the therapy) jointly reviewing the recordings, with the guider providing praise to the parent, not for the attunement per se but for engaging in the evaluation of the interactions being viewed.

The intervention model is underpinned by two core concepts: intersubjectivity and mediated learning. Intersubjectivity, or 'shared moments of attunement', is modelled by the therapist (or 'guider') in their relationship and interactions with the parent, as well as being identified in the video recordings of the parent‐child interaction. Mediated learning, or 'scaffolding', refers to the role adults play in helping children learn how to do things that they might not otherwise manage alone. Mediated learning is also modelled by the guider in his or her relationships with the parent, as the guider helps the parent to describe what is happening in the clips being viewed, and what the parent and child in the video might be thinking or feeling, and to identify the consequences for the parent and the child (Kennedy 2011).

Video feedback may be delivered on a one‐to‐one (e.g. VIPP, VIG) or group (e.g. Circle of Security (CS)) basis, and has been used with first‐time mothers (Klein Velderman 2006); hard‐to‐reach families (Kennedy 2010); parents of premature infants (Hoffenkamp 2015); parents with mental health problems, including postpartum depression (Vik 2006); parents of autistic children (Poslawsky 2015), maltreated children (Moss 2011), and adopted children (Juffer 1997); parents of children with atopic dermatitis (Cassibba 2015); ethnic‐minority parents (Yagmur 2014); and parents with an eating disorder (Stein 2006). Although video feedback is usually delivered in the home environment, it has also been used in clinical settings, such as hospital environments with mothers of preterm babies (Hoffenkamp 2015), and residential treatment centres (Kennedy 2010). It is now used in over 15 countries by practitioners who work in a range of helping professions (e.g. social work, education and health; Kennedy 2010).

How the intervention might work

In terms of the underpinning theoretical model, most forms of video feedback are attachment‐based in the sense that they aim to enhance maternal sensitivity, and promote optimal child social and emotional development (Klein Velderman 2006a), with the longer‐term goal of promoting improved child attachment (Juffer 2008). However, the presumed mechanisms by which this is achieved vary across the different models of video feedback. All video‐feedback interventions primarily target the behavioural level using video‐recorded episodes of the parent‐child interaction. The guider provides an opportunity for the caregiver to experience attuned interactions with a sensitively attuned adult (Kennedy 2011), and also to view themselves in interaction with their child and observe positive responses from them. Together, these are hypothesised to bring about a range of meta‐cognitive changes that result from the discrepancy between their own beliefs about their ability to parent and what they can see on the video, in addition to an increase in feelings of empowerment and self‐efficacy, and their ability for self‐reflection (Kennedy 2011).

Some models of video‐feedback intervention include additional components that may provide a more explicit focus on representational issues. For example, Video Feedback Intervention to Promote Positive Parenting with Discussions on the Representational Level (VIPP‐R; Juffer 2008), involves the therapist addressing the mother's representations and attachment using discussions that may, for example, focus explicitly on the mother's own experiences of separation in early childhood and those experienced with her own child (Klein Velderman 2006a).

Other models involve the inclusion of teaching about sensitive discipline techniques, such as Video Feedback Intervention to Promote Positive Parenting ‐ Sensitive Discipline (VIPP‐SD). There is evidence that suggests the effectiveness of video feedback may vary with factors at both the level of the parent and of the child. For example, Klein Velderman 2006 reported that amongst mothers with insecure attachments, those classed as 'insecure dismissing' (who idealise their own parents or minimise the importance of attachment relationships in their own lives) benefited most from video feedback, whilst those classed as 'insecure preoccupied' benefited most when they participated in video feedback together with further discussions about their individual experiences of attachment in childhood.

Why it is important to do this review

Improvement of the health and well‐being of children is part of a global agenda. While the basic needs of children (e.g. food, sanitation, health care) are paramount to survival and development, living with an adult who is responsive to their needs is also important (Jones 2003). UNICEF 2008 highlights that a loving, stable and stimulating relationship with caregivers in the earliest months and years of life are critical for every aspect of a child’s development. Specifically, the empirical literature shows that maternal sensitivity is a key predictor of child attachment security (De Wolff 1997), and that a secure attachment promotes more optimal childhood development (Sroufe 2005), while an insecure or disorganised attachment predicts later behaviour problems (Fearon 2010), and psychopathology (Steele 2010). Research suggests that early, targeted interventions are potentially an effective means of increasing parental sensitivity (Bakermans‐Kranenburg 2003), and although there have been a number of reviews of the impact of video feedback on a range of outcomes including maternal sensitivity (Balldin 2018; Fukkink 2008; Juffer 2018; NICE 2016; Van den Broek 2017), only two conducted meta‐analyses. Fukkink 2008 concluded that video feedback was an effective means of improving parenting behaviour and attitudes, and child development. However, the report did not provide the search dates for the review, which was submitted in June 2008; did not search a wide range of databases; and was very broad in its scope, including all uses of video feedback with no age limits on the children (who ranged in age from birth to seven years, with an average age of 2.4 years (standard deviation (SD) 2.7 years). More importantly, the study authors paid little attention to the quality of included studies (that is, there were no 'Risk of bias' assessments) and included studies without random assignment. Juffer 2018 looked only at studies using one type of video feedback known as 'Video Interaction to promote Positive Parenting' (VIPP) and found that VIPP was effective in improving parental sensitivity.

This systematic review of current best evidence addresses the methodological weakness of Fukkink 2008 and has a broader scope than Juffer 2018. It will be of interest to policy makers and practitioners internationally.

Objectives

To assess the effects of video feedback on parental sensitivity and attachment security in children aged under five years who are at risk for poor attachment outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (in which the allocation to study arms is not truly random; for example, allocation is done through a form of alternation such as days of the week or by date of birth). We included cluster‐ and cross‐over RCTs.

We excluded studies that had an alternative treatment but no control group. Alternative treatment controls are not appropriate when seeking to investigate the effectiveness of an intervention, which was the aim of this review (this is in accordance with advice from Cochrane Developmental, Pyschoscial and Learning Problems).

Types of participants

We included parent‐child dyads (including foster or adoptive carers) or family units, where the child was aged between birth and four years 11 months (inclusive), and where problems had been identified that might impact or were impacting the parent's sensitivity (e.g. poor bonding, depression, eating disorders, maltreatment) or child attachment (e.g. behaviour problems, challenging temperament, preterm birth). The majority of studies looked at parent‐child dyads.

If studies included a proportion of participants aged above four years 11 months, we endeavoured to obtain data on the sample aged up to four years 11 months; where this was not possible, we used outcome data that included children outside our target age group in the meta‐analysis (e.g. Moss 2011; Poslawsky 2015).

We excluded studies in which the intervention was used with a population group where neither parents nor children had any risk factors for attachment problems.

Types of interventions

We included video‐feedback interventions delivered in any setting, in which the parent and child were filmed and then feedback was provided to the parent either on a one‐to‐one basis or in groups, with the aim of improving the sensitivity of their interactions with the child, child attachment, or the reflective functioning of the parent.

We included interventions that, in addition to video feedback, also provided a small number of additional sessions related to the primary aim of the intervention; for example, VIPP‐R or VIPP‐SD.

We included studies in which the intervention was compared with no treatment, an inactive alternative intervention or treatment as usual. Examples of control treatment included a sequence of telephone calls with a parent (Barone 2019; Kalinauskiene 2009; Negrão 2014; Van Zeijl 2006; Yagmur 2014); a limited number of home visits with (1) video recordings between parent and child with no feedback (Benzies 2013; Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Moran 2005); (2) by a play and development service (Green 2010); (3) discussions about parenting (Poslawsky 2015); standard hospital care (Hoffenkamp 2015) or routine care at well baby units (Høivik 2015).

We excluded studies comparing video feedback with other interventions, as well as:

interventions in which video feedback was used as part of a wider set of methods of working with the family and in which we could not differentiate the effect of video feedback, and

programmes that used videotape modelling or videotaped vignettes of parents and their children (e.g. Webster‐Stratton 2015).

Types of outcome measures

We excluded studies that did not measure parental sensitivity or did not do so in an objective way; for example, studies relying on self‐report measures, such as the Parent‐Child Dysfunctional Interaction (PCDI) subscale of the Parenting Stress Index (Abidin 1995).

Primary outcomes

Parental sensitivity, measured by, for example, the Ainsworth Sensitivity Scale (ASS; Ainsworth 1974), the Child‐Adult Relationship Experimental Index (CARE‐Index; Crittenden 2001), the Parental Sensitivity Assessment Scale (PSAS; Hoff 2004), Coding Interactive Behaviour (CIB; Feldman 1998), the Emotional Availability (EA) scales (Biringen 2000a), Global Ratings Scales (GRS) of mother‐infant interaction (Murray 1996), Maternal Behaviour Q‐sort (MBQS; Pederson 1999), or Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS; Sumner 1994).

Parental reflective functioning, measured by, for example, the Parent Development Interview (PDI; unpublished manuscript by Aber 1985), or the PDI‐Revised (PDI‐R; unpublished manuscript by Slade 2004).

Attachment security, measured by, for example, the Attachment Q‐sort (AQS; Waters 1985; Waters 1987), or the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP; Ainsworth 1978).

Adverse effects. We acknowledge that a worsening of any of our primary outcomes listed above would be considered an adverse effect. However, we also considered the effects of the intervention on parental anxiety and stress, measured by, for example, the Parenting Stress Index (PSI; Abidin 1995), or the Parenting Stress Scale (PSS; Berry 1995).

Secondary outcomes

Child mental health, measured by behavioural assessments of emotional disorders, hyperactivity and conduct disorders.

Child physical and socioemotional development, measured through, for example, the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (Bayley‐III; Bayley 2006), or the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman 1997).

Child behaviour, measured by, for example, the Child Behaviour Assessment Instrument (CBAI; Samarakkody 2010).

Costs, measured by direct costs stated by studies.

Timing of outcome assessment

We collected outcome data at time points provided within the included studies and grouped these as postintervention (immediately upon completion of the intervention), short term (up to six months), medium term (up to one year) and long term (over one year).

Search methods for identification of studies

We ran the first database searches in August and September 2016 (Electronic searches) followed by searches of other resources in July 2017 (Searching other resources). In November 2018 we updated the searches, including bibliography screening, and ran further searches of other resources in July 2019. We did not apply any date or language restrictions to the electronic searches and had two papers translated into English (Bovenschen 2012; Kalinauskiene 2009).

Electronic searches

We searched the electronic databases and trials registers listed below.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 11), in the Cochrane Library and which includes the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems' Specialised Register (searched 10 November 2018)

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to November Week 1 2018)

Embase Ovid (1974 to 2018 Week 44)

CINAHL Plus EBSCOhos (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1937 to 10 November 2018)

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to 2018 Week 44)

Sociological Abstracts ProQuest (1952 to 10 November 2018)

Social Sciences Citation Index Web of Science (SSCI; 1970 to 10 November 2018)

Social Services Abstracts ProQuest (1979 to 10 November 2018)

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Social Science & Humanities Web of Science (CPCI‐SS&H; 1990 to 10 November 2018)

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database; 1985 to current; lilacs.bvsalud.org/en; searched 10 November 2018).

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR; 2018; Issue 11), part of the Cochrane Library (searched 10 November 2018)

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; 2015; Issue 2. Final issue), part of the Cochrane Library (searched 10 November 2018)

Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD; www.ndltd.org; searched 10 November 2018)

WorldCat (limited to dissertations and theses; www.worldcat.org; searched 10 November 2018)

Clinicaltrials.gov (Clinicaltrials.gov; searched 10 November 2018)

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; www.who.int/ictrp/en; searched 10 November 2018)

Searching other resources

Two review authors (ES and LOH) screened the bibliographies of included studies (Barlow 2016; Barone 2019; Benzies 2013; Bovenschen 2012; Green 2010; Green 2015; Hodes 2017; Hoffenkamp 2015; Høivik 2015; Kalinauskiene 2009; Klein Velderman 2006; Koniak‐Griffin 1992; Lam‐Cassettari 2015; Moran 2005; Moss 2011; Negrão 2014; Platje 2018; Poslawsky 2015; Seifer 1991; Stein 2006; Van Zeijl 2006; Yagmur 2014) and relevant reviews (Balldin 2018; Fukkink 2008; Juffer 2018; NICE 2015; Van den Broek 2017), to identify any additional relevant publications. They also searched the websites of the following relevant organisations and government departments: United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) Global Evaluation Database (unicef.org/evaldatabase); National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) Impact and Evidence Hub (nspcc.org.uk/services‐and‐resources/impact‐evidence‐evaluation‐child‐protection); and the Association for Video Interaction Guidance UK (AVigUK; videointeractionguidance.net) (see Appendix 1). One review author (ES) visited the websites of research groups we knew to be conducting work in this area to screen their listed publications (see Appendix 1). Another review author (LOH) also used Google Scholar to search the internet for unpublished work (see Appendix 1).

Although originally planned (O'Hara 2016), we did not contact experts to enquire about other published work or unpublished work (Table 2).

1. Methods for use in future updates of this review.

| Issue | Method |

| Searching other resources | We will draft a list of included studies to send to experts in the field and ask them to forward to us any published, unpublished or ongoing work that we may have missed. |

| Measures of treatment effect |

Continuous outcome data If necessary, we will compute effect estimates from P values, T statistics, analysis of variance (ANOVA) tables or other statistics, as appropriate. |

| Measures of treatment effect |

Multiple outcomes When a study provides multiple, interchangeable measures of the same construct at the same point in time (e.g. multiple measures of maternal sensitivity), we will calculate the average SMD across these outcomes and the average of their estimated variances. This strategy aims to avoid the need to select a single measure and to avoid inflated precision in meta‐analyses (i.e. preventing studies that report on more outcome measures receiving more weight in the analysis than comparable studies that report on a single outcome measure). |

| Unit of analysis issue |

Cluster‐RCTs In the event that we identify relevant cluster‐RCTs that meet the inclusion criteria of the review, we will deploy appropriate statistical methods based on the guidance provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Where study authors have dealt appropriately with the clustered design in their analyses, we will try to obtain direct estimates of the effect (e.g. an OR with its CI). Where study authors have not dealt appropriately with the cluster design in their analyses, we will extract or calculate effect estimates and their SEs as for a parallel‐group trial, and adjust the SEs to account for the clustering (Donner 1980). To do this, we will need to identify an appropriate ICC, which describes the relative variability in outcome within and between clusters (Donner 1980). Where available, we will look for this information in the reports of relevant trials. If this is unavailable, we will try to obtain the information from the study authors. If this proves unsuccessful, we will use external estimates obtained from similar studies. We will find closest‐matching scenarios (regarding both outcome measures and types of clusters) from existing databases of ICCs. If we are unable to identify any matches, we will perform sensitivity analyses using a high ICC of 0.1, a moderate ICC of 0.01 and a small ICC or 0.001, to cover a broader range of plausible values while still allowing for strong design effects for smaller studies (see Sensitivity analysis). Furthermore, we will combine these estimates and their corrected SEs from the cluster‐RCTs with those from parallel designs using the generic inverse variance method in Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). |

| Dealing with missing data |

Data imputation Where it has not been possible to obtain any unreported data from authors of included studies, and there is reason to believe that it is not missing at random, we will follow the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011, Section16.1), and we will do the following:

|

|

Meta‐regression We will assess the sensitivity of any primary meta‐analyses to missing data using meta‐regression to test for any effect of missingness on the summary estimates (Higgins 2011, Section 16.1.2). | |

| Data synthesis | In the occurrence of severe funnel plot asymmetry, we will present both fixed‐effect and random‐effects analyses under the assumption that asymmetry suggests that neither model is appropriate. If both indicate a presence (or absence) of effect we will be reassured; if they do not agree we will report this. |

| Subgroup analyses | We will investigate heterogeneity using subgroup analyses or meta‐regression, if appropriate. We will group the included studies and analyse them according to the intervention approach, including the following.

|

| Sensitivity analysis | We will assess the robustness of findings to decisions made in obtaining them by conducting sensitivity analyses. We will perform sensitivity analyses by conducting the following reanalysis.

|

| CI: confidence interval; ICC: intra‐class correlation coefficient; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SD: standard deviation; SMD: standardised mean difference; VIG: Video Interaction Guidance; VIPP‐R: Video‐feedback to promote Positive Parenting ‐ Representational level; VIPP‐SD: Video‐feedback to promote Positive Parenting ‐ Sensitive Discipline | |

Data collection and analysis

For this section, we only report those methods used in this review. Other methods that were not relevant to the available data, or that we could not use for other reasons, are summarised in Table 2. One of the review authors (JB) is an author of an included study (Barlow 2016). JB was not involved in data extraction or assessment of risk of bias; the review authors involved in this did not need to seek any further advice on either of these areas with regards to this particular study.

Selection of studies

At least two review authors (from ES, LOH and NH) independently screened titles and abstracts yielded by the searches against the inclusion criteria for the review (Criteria for considering studies for this review). The review authors retrieved the full‐text reports of all studies selected for potential inclusion, or those where there was some uncertainty, and assessed the reports for eligibility. Where review authors could not agree, they further discussed the papers with JB or GM. In one case, Mendelsohn 2005, we wrote to the study authors for the purposes of clarifying whether or not the study met our inclusion criteria (Table 3). We list excluded studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables, together with the reason for their exclusion. We report the flow of studies in a PRISMA diagram (Liberati 2009).

2. Summary of contact with study authors.

| Study | Date contact initiated | Reason for contacting study authors | Response received |

| Barone 2019 | 9 July 2019 (Smith 2019a [pers comm]) | The study data for maternal sensitivity were reported in the published paper as part of a composite measure. We requested maternal sensitivity subscore. We also requested study data for overall child behaviour, as the published report only contained externalising behaviour. | The study author provided the maternal sensitivity and child behaviour data for inclusion in the meta‐analysis (Barone 2019 [pers comm]). They excluded children aged 5 years and over from the data sent over, as the original study did include these children. |

| Bovenschen 2012 | 12 January 2018 (Smith 2018b [pers comm]) | The reported data were not labelled sufficiently clearly in the published paper to be used in the meta‐analysis. We requested clarification from the study authors. | The study author provided the necessary, additional study data, so they could be included in meta‐analysis (Bovenschen 2019 [pers comm]). |

| Hodes 2017 | 2 June 2017 (Smith 2017a [pers comm]) | We requested study data relating to parental stress outcomes, reanalysed for children within included age range. | We received no response. As a result, we did not subsequently request the study data on Harmonious Parent‐Child Interaction to be analysed for children within included age range. |

| Hoffenkamp 2015 | 16 January 2017 (O'Hara 2017a [pers comm]) | We requested missing study data relating to parental sensitivity outcomes. | The study author provided the missing data so they could be included in the meta‐analysis (Van Bakel 2017 [pers comm]). |

| Høivik 2015 | 8 February 2018 (Smith 2018c [pers comm]) | The study data for maternal sensitivity were reported in the published paper as part of a composite measure. We requested maternal sensitivity subscore. | The study author provided maternal sensitivity data for inclusion in the meta‐analysis (Hoivik 2018 [pers comm]). |

| Klein Velderman 2006 | 21 February 2018 (Smith 2018g [pers comm]) | The outcomes data for maternal stress were not included in published studies. | The corresponding author provided us with the missing data for the purposes of meta‐analysis (Bakermans‐Kranenburg 2018 [pers comm]). |

| Koniak‐Griffin 1992 | 8 February 2018 (Smith 2018d [pers comm]) | The study data for maternal sensitivity were reported in the published paper as part of a composite measure. We requested maternal sensitivity subscore. | We received no response. |

| Lam‐Cassettari 2015 | 2 June 2017 (Smith 2017b [pers comm]) | The published study data for maternal sensitivity outcomes included children aged 5 years and over. We requested outcomes data with those children excluded. | The study author provided the data with those children aged 5 years and over excluded (Lam‐Cassettari 2018 [pers comm]). |

| Mendelsohn 2008 | 1 February 2018 (Smith 2018i [pers comm] | We requested a copy of the conference abstract. | We received no response. |

| Moran 2005 | 3 June 2017 (O'Hara 2017b [pers comm]) | The maternal sensitivity outcomes were reported as means without standard deviations or standard errors. We requested these data so they could be used in the meta‐analysis. | The corresponding author no longer had access to the data due to retirement, so could not provide the information (Moran 2017 [pers comm]). |

| Moss 2011 | 12 January 2018 Smith 2018h [pers comm] |

The published study data for maternal sensitivity outcomes included children aged 5 years and over, We requested outcomes data with those children excluded. | We received an initial response from the study authors but they did not subsequently provide the data (Dubois‐Comtois 2018 [pers comm]). |

| Negrão 2014 | 12 January 2018 (Smith 2018e [pers comm]) | The maternal stress outcomes data were not reported in the published paper, so we requested this information for the purposes of the meta‐analysis. | The study author provided these data for the purposes of meta‐analysis (Pereira 2018 [pers comm]). |

| Poslawsky 2015 | 12 January 2018 (Smith 2018f [pers comm]) | The reported outcomes included children aged 5 years or older. We requested outcomes data with those children excluded. We also requested means and standard deviations for the relevant 3‐month follow‐up outcome (daily hassles). | The corresponding author was unable to provide the requested data (Poswlawsky 2018 [pers comm]). |

| Seifer 1991 | 22 July 2019 (Smith 2019b [pers comm]) | We requested outcomes data for mental and psychomotor development | We received no response. |

| Stein 2006 | 22 May 2018 (Barlow 2018 [pers comm]) | The outcomes data for 'Verbal responses to infant cues' were reported as medians, so we requested the means and standard deviations. | The study authors provided us with these data for the purposes of meta‐analysis (Stein 2018 [pers comm]). |

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (from NH, LOH, ES) independently extracted data from each included study and recorded the following information on a pre‐piloted data extraction form.

Participant characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, location)

Intervention characteristics (including delivery, duration, outcomes and measures, and within‐intervention variability)

Comparison characteristics (including whether the study used an active or inactive comparison)

Study characteristics (study design, sample size, length of follow‐up, attrition or dropout, handling of missing data, methods of analysis, dates of study, funding sources, conflicts of interest)

Outcome data (relevant details on all primary and secondary outcome measures used, and summary data, including means, standard deviations (SDs), confidence intervals (CIs) and significance levels for continuous data and proportions for dichotomous data)

Review authors resolved disagreements through discussion. Where clarity was needed over whether an outcome in a study was relevant, the reviewer authors sought advice from JB.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (ES for all studies, with either LOH or NH) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included study using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2017). They assigned judgements of low, high or unclear risk of bias for each of the following domains, using the criteria set out in Appendix 2: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants and personnel; blinding of outcome assessment; incomplete outcome data; selective reporting and other bias. Where review authors did not agree after discussion, they discussed further with another author (JB or NL). We recorded the judgements in 'Risk of bias' tables.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated unadjusted treatment effects using Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) (Review Manager 2014).

Dichotomous outcome data

We calculated the odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI for dichotomous outcomes. For dichotomous outcomes that we included in the 'Summary of findings' tables, we expressed the results as absolute risks and used high and low observed risks among the control groups as reference points.

Continuous outcome data

For continuous outcomes, we calculated the mean difference (MD) if all included studies used the same measurement scale, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if studies used different measurement scales, and 95% CIs. We calculated SMD using Hedge's g. In one instance, we converted an SMD from Cohen's d to Hedge's g.

Economics issues

We reviewed studies for data on the costs of programmes within the included studies.

Unit of analysis issues

Studies with multiple treatment groups

In the primary analysis, we combined results across all eligible intervention groups and compared them with the combined results across all eligible control groups, and made single pair‐wise comparisons. Where studies compared more than one form of video interaction with a control group or groups, such that combining them prevented investigation of potential sources of heterogeneity, we analysed each video interaction group separately (against a common control group) but divided the sample size for common comparator groups proportionately across each comparison (Higgins 2011; Section 16.5.5). This simple approach allows the use of standard software and prevents inappropriate double counting of individuals. We applied this latter approach to three studies (Benzies 2013; Hoffenkamp 2015; Klein Velderman 2006).

Dealing with missing data

Where necessary, one review author (LOH or ES) contacted the authors of included studies requesting them to supply any unreported data such as missing outcome data (e.g. group means and SDs and details of number of dropouts). Details of which study authors we contacted and why are in the Characteristics of included studies tables and Table 3.

If we were not able to obtain unreported outcome data, we followed the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011, Section 16.1) and did the following:

Analysed the data available, as we assumed the data were missing at random.

Two studies had unreported outcome data on parental sensitivity that the study authors were unable to provide: Koniak‐Griffin 1992 reported a result for a scale with parental sensitivity as a subdomain, but did not report the subdomains; and Moran 2005 reported means but not SDs or standard errors (SE). We did not impute this unreported data, as we assumed the data were missing at random.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity across included studies by examining the distribution of important participant factors (e.g. age) and intervention characteristics (e.g. style, setting, personnel, context of delivery) among studies. The details of this information are included in the Characteristics of included studies tables, and discussed in the Results section.

We assessed methodological heterogeneity across included studies by comparing the distribution of study factors (e.g. allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, losses to follow‐up, treatment type, cointerventions). This information is contained in the Characteristics of included studies tables and 'Risk of bias' tables, and considered in the Discussion.

We described statistical heterogeneity by computing the I2 statistic (Higgins 2002), which describes approximately the proportion of variation in point estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error. In addition, we used the Chi2 test (P < 0.10) of homogeneity to detect the strength of evidence that heterogeneity is genuine (Deeks 2017).

Assessment of reporting biases

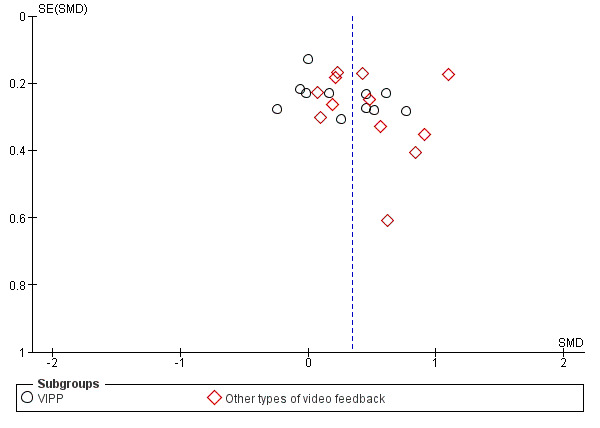

We drew a funnel plot (estimating differences in treatment effects against their standard error (SE)) when we identified 10 or more studies that provided data on an outcome; in this case, parental sensitivity. We assessed the funnel plot by visual inspection and also by Egger's regression test (Egger 1997). We redrew the funnel plot without an outlying study (Green 2010), to better assess the asymmetry.

We considered the reasons for any asymmetry. Asymmetry might be due to publication bias, but might also reflect a relationship between study size and effect size, such as when larger studies have lower compliance, and compliance is positively related to effect size. It may also be due to clinical variation between the studies (Sterne 2017, Section 10.4), for example the study population, reflecting true heterogeneity.

As a direct test for publication bias, we compared results extracted from published journal reports with results obtained from other sources for the two outcomes for which this was possible, parental sensitivity and parental stress. In these cases we obtained some outcome data directly from study authors that were not reported in the published papers (see Table 3).

Data synthesis

Where interventions were similar in terms of (1) the age of the child(ren), (2) parent gender and (3) intensity, frequency and duration of video feedback, we synthesised results in a meta‐analysis.

We used both fixed‐effect and random‐effects models and compared the results to assess the impact of statistical heterogeneity. Except where the model was contraindicated (e.g. if there was funnel plot asymmetry), we present the results from the random‐effects model. When we report the results of the random‐effects model, we include an estimate of the between‐study variance (Tau2).

We calculated all overall effects using inverse variance methods.

Where some primary studies reported an outcome as a dichotomous measure and others used a continuous measure of the same construct (as in the case of attachment security), we performed two separate analyses rather than converting the OR to a SMD. This was because we could not assume that the underlying measure had a normal or logistic distribution, as the nature of the populations in the two relevant studies means that the distribution of attachment patterns is likely to be skewed (teenage mothers in Moran 2005 and families where children had been subjected to maltreatment in Moss 2011).

Where a trial reported two outcomes within a time period covered by the same meta‐analysis, we combined the data from the time point nearest the end of the intervention. Where possible, we tried to combine outcomes measured at similar time points in the follow‐up period.

'Summary of findings' table

We created a 'Summary of findings' table for the following comparison: video feedback versus no intervention or inactive alternative intervention.

We followed the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2017), and included the following six elements in these tables.

A list of all outcomes

A measure of the typical burden of these outcomes

Absolute and relative magnitude of effect

Numbers of participants and studies that address these outcomes

A rating of the overall certainty of evidence for each outcome

Additional comments

Two review authors (LOH, ES) independently assessed the certainty of the evidence, using the following five GRADE considerations (Schünemann 2017).

Limitations in study design and implementation: for RCTs, for example, these included lack of allocation concealment, lack of blinding and large loss to follow‐up.

Indirectness of evidence: for example, if findings were restricted to indirect comparisons between two interventions. RCTs that met the eligibility criteria but that addressed a restricted version of the main review questions in terms of population, intervention, comparator or outcomes are another example of this and would also have been downgraded.

Unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results: we looked for robust explanations for heterogeneity in studies that yielded widely differing estimates of effect.

Imprecision of results: we downgraded the certainty of evidence for those studies that included few participants and few events and thus had wide CIs.

Publication bias: we downgraded the certainty of evidence level if investigators failed to report studies or outcomes on the basis of results.

We downgraded the ratings (from high to very low), depending on the presence of the five factors.

We used GRADEpro GDT to prepare the 'Summary of findings' table, and specifically, to enable us to produce relative effects and absolute risks associated with the interventions (GRADEpro GDT). We used all primary outcomes and one secondary outcome of interest to populate the ‘Summary of findings’ table (primary outcomes: parental sensitivity at postintervention to six months; reflective functioning; attachment security measured by Strange Situation Procedure at postintervention; attachment security measured by Attachment Q‐sort at postintervention; parental stress measured at postintervention and short‐term follow‐up; and parental anxiety at short‐term follow‐up; secondary outcome: child behaviour measured at long‐term follow‐up). We also used Ryan 2016 to guide our judgements.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We investigated heterogeneity by conducting moderator analyses for the outcome of 'parental sensitivity'. To perform this analysis, we used a random‐effects meta‐analysis with a Sidik‐Jonkman estimator, which is robust for small numbers of studies and provides improved CI (Veroniki 2019). We considered the following factors, some of which we decided post hoc.

Prespecified factors

Intervention dose: defined by number of video feedback sessions (zero to five versus six to 10 versus more than 10; grouping this factor in this way was a post hoc decision).

Participating carer: all mothers versus all fathers versus mix of mothers and fathers (we made a post hoc decision to include studies with a mix of parental genders along side those who were all fathers or all mothers).

Type of video feedback (VIPP versus non‐VIPP; grouping types of video feedback in this way was a post hoc decision).

Factors specified post hoc

Age of child (children under one year old versus children aged one year or older; using age of child as a factor was a post hoc decision).

Disability status of children (disability versus no disability; using disability status of the child was a post hoc decision).

In the first step, we assessed the moderators individually and reported their overall contribution to the reduction of heterogeneity (Q‐between). To assess whether moderation effects for study characteristics existed, we conducted a moderator analysis in which we included the three prespecified moderators (type of video feedback, duration of video feedback and participating carer) simultaneously, this accounts for potential correlations between moderators. Given the small number of studies, this analysis should be treated with caution, due to the relatively low power. Predicted values are reported alongside regression results. We did not impute missing data in line with the main analyses.

We conducted the moderator analyses in R version 3.6.1 (R 2018), using the metafor‐package 2.1.0 (Viechtbauer 2010); analysis syntax and data are available from the review authors on request.

Sensitivity analysis

We assessed the robustness of findings to decisions made in obtaining them by conducting the following sensitivity analyses (Deeks 2017).

Reanalysis excluding studies at high or unclear risk of bias

Reanalysis using different statistical approaches (comparing the use of a random‐effects model with a fixed‐effect model).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

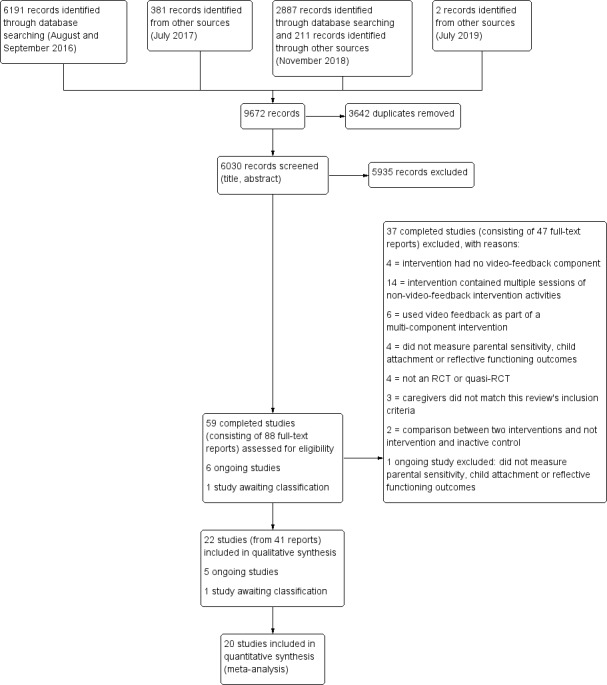

Our initial electronic searches (August to September 2016 and July 2017) identified 6191 records (see Figure 1). We identified an additional 381 records from other sources. After the removal of duplicates, we screened the titles and abstracts of 4368 records. We obtained and scrutinised 81 full‐text reports for eligibility, 47 of which (37 studies) did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded from the review with reasons (see Characteristics of excluded studies), and 34 (19 studies) that did and were included in the review.

1.

95 Study flow diagram

Our updated electronic searches (November 2018) identified 2887 records. We identified an additional 211 records through other sources in November 2018, and an additional two records in July 2019. After the removal of duplicates, we screened the titles and abstracts of 1662 records. During the title and abstract screening, we identified six ongoing studies, one of which we excluded, leaving five ongoing studies (Euser 2016; Firk 2015; ISRCTN92360616; NCT03052374; Schoemaker 2018), and one study awaiting classification (Mendelsohn 2008). We reviewed seven full‐text reports and added six reports pertaining to three new studies (Barone 2019; Platje 2018; Seifer 1991) and one report of a study identified during our initial search (Hodes 2017), to the review (see Figure 1).

Included studies

This review includes 22 studies (see Characteristics of included studies tables and Table 4), comprising a total of 41 reports and 1889 randomised parent‐child dyads or family units.

3. Type of video‐feedback intervention.

| Study | Aim | Content/delivery |

| Video‐feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting (VIPP; Juffer 2008) | ||

| Green 2015 | To test the effect of a parent‐mediated intervention for children at high risk of autism spectrum disorder | Video Interaction for promoting Positive Parenting (iBASIS‐VIPP), a modification for the autism prodome of the VIPP infancy programme. The intervention consisted of 12 sessions (an additional 6 booster sessions compared with VIPP).The intervention uses video feedback "to help parents understand and adapt to their infants' individual communication style to promote optimal social and communicative development" (quote). The study authors describe that "The therapist uses excerpts of parent‐child interactions in a series of developmentally sequenced home‐sessions focusing on interpreting the infant's behaviour and recognising their intentions; enhancing sensitive responding; emotional attunement and patterns of verbal and non‐verbal interaction." (quote) |

| Hodes 2017 | To test if a video‐feedback intervention to promote positive parenting and sensitive discipline reduces child‐related parental stress in parents with mild learning disabilities in comparison with care as usual | A Video‐feedback Intervention for Positive Parenting and Learning Difficulties (VIPP‐LD) where the original protocol of VIPP‐SD (Juffer 2008) was adapted for mild intellectual disabilities. For VIPP‐LD, in each session, the parent is videoed interacting with their child. The coach and parent review the footage together, drawing attention to instances of sensitive responsiveness and sensitive discipline, and the coach helps the parent look at the child from the child's perspective. The adaptation included shortening of each session, shorter video recordings and more real‐life practice. The study authors describe how "Parents also received a personal scrapbook with skills taken from video recordings and quotes from the parents representing the theme of the session." (quote) |

| Kalinauskiene 2009 | To evaluate the effectiveness of a short‐term, interaction‐focused video‐feedback intervention implemented in families with mothers rated low in maternal responsiveness | A Video‐feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting (VIPP). The intervention was applied as per protocol with the main goal "to reinforce mothers' sensitive responsiveness to their infants' signals focusing on different aspects of mother‐infant interactions" (quote). Mothers were also "provided with information on attachment‐related issues by giving them brochures about sensitive parenting." (quote) |

| Klein Velderman 2006 | To explore if a combination of attention to parental sensitivity and parental attachment representations might lead to firmer and more enduring changes in both parenting behaviour and children's attachment security | A Video‐feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting (VIPP). VIPP programs consisted of four home visits lasting 1.5 hours each, with 3‐4 weeks in between. Each session was focused around a specific theme. VIPP‐R included additional discussions on parental representations. |

| Negrão 2014 | To test the effectiveness of a video‐feedback intervention to promote positive parenting and sensitive discipline in a sample of poor Portuguese mothers and their 1‐4‐year old children | A sensitive discipline video‐feedback intervention to promote positive parenting (VIPP‐SD). The study authors state that "VIPP‐SD is a short term intervention programme that relies on video‐feedback technique to enhance parental sensitivity and positive discipline strategies. The intervention was applied through standardised protocols of six home visits...The VIPP‐SD working method is divided into three steps: (1) Sessions 1 and 2 main goals are building a relationship with the mother, focusing on child behaviour and emphasizing positive interactions in the video feedback; (2) Sessions 3 and 4 actively work on improving parenting behaviours by showing the mother when her parenting strategies work and to what other situations she could apply these strategies; and (3) Sessions 5 and 6 (booster) aim to review feedback and information from the previous sessions in order to strengthen intervention effectiveness." (quote) |

| Platje 2018 | To evaluate a video‐feedback intervention aimed at improving parent‐child interaction for parents of children with a visual or visual and intellectual disability | A Video‐feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting adapted to parents of children with a visual or visual and intellectual disability (VIPP‐V). The study authors state that the intervention was based on VIPP, but "this new intervention [is] applicable for use in families with a young child with a visual or visual‐and‐intellectual disability. Particular attention was devoted to increasing (safe) exploration, joint attention, and parent’s abilities to recognize and understand the signals and emotions of their child" (quote). The intervention consists of 7 home visits (5 primary visits plus 2 booster sessions). |

| Poslawsky 2015 | To evaluate the early intervention programme, video‐feedback intervention to promote positive parenting adapted to autism, with primary caregivers and their child with autism spectrum disorder | VIPP adapted to autism (VIPP‐AUTI). The intervention comprised 5 home visits lasting 60‐90 minutes every 2 weeks. Sessions included: (1) "Attachment and Exploration" (quote); (2) "Speaking for the Child" (quote); (3) "Sensitivity Chain" (quote); (4) "Sharing Emotions" (quote); (5) "Booster session" (quote). |

| Van Zeijl 2006 | To test the video‐feedback intervention to promote positive parenting and sensitive discipline in "a large sample of families screened for their children's relatively high scores on externalizing behaviour." (quote) | The study applied VIPP‐SD, aimed at parental sensitivity and sensitive parental discipline. The first four intervention sessions each had their own themes, (1) "exploration versus attachment" (quote); (2) "centered around speaking for the child" (quote); (3) "the intervener stressed the importance of adequate and prompt responses to the child’s signals" (quote); (4) "the importance of sharing—both positive and negative—emotions (sensitivity) and promoting empathy for the child" (quote); (5 & 6) "aimed at consolidating intervention effects by integrating—in video feed‐back and discussion—all tips and feedback given in the previous sessions" (quote). |

| Yagmur 2014 | "To test the effectiveness of the video feedback intervention to promote positive parenting and sensitive discipline adapted to the specific child‐rearing context of Turkish families (VIPP‐TM) in the Netherlands" (quote), including second‐generation Turkish immigrant families with toddlers at risk for the development of externalising problems | "The VIPP‐TM program is a culturally sensitive adaptation of the VIPP‐SD program for Turkish minority families in the Netherlands, but follows the general procedures of the original program...The VIPP‐SD program is described in a detailed protocol and consists of six home visits. The first four visits each have their own themes regarding sensitivity and discipline, and the last two sessions are booster sessions in which the themes from previous sessions are reviewed once more." (quote) |

| Video Interaction Guidance (VIG) | ||

| Barlow 2016 | "To assess the potential of video interaction guidance to increase sensitivity in parents of preterm infants." (quote) | The study authors report that "VIG is a strengths‐based form of video feedback in which parents are invited to jointly observe and reflect on their own successful interactions with their baby...The core aspects of the model involve three home visits comprising (a) video recording the parent‐infant interaction during play or other aspects of care giving, (b) editing of the recording to select micro‐moments of interaction that demonstrate the infant's contact initiatives and the parents attuned response to these signals and (c) joint reviewing of the recordings with the parent." (quote) |

| Hoffenkamp 2015 | To evaluate the effectiveness of hospital‐based video interaction guidance in parents with moderately and very preterm babies | "Video recordings of parent‐infant interactions and the feedback from a VIG professional provide an opportunity for parents to observe, analyse and discuss the infant's behaviour and contact initiatives" (quote). In this study "VIG consisted of three sessions during the first week after birth" (quote), and included "(1) video‐recording parent‐infant interaction; (2) editing the video recordings; (3) reviewing the edited recordings with parents." (quote) |

| Lam‐Cassettari 2015 | To examine "the effect of a family‐focused psychosocial video intervention program on parent‐child communication in the context of childhood hearing loss" (quote) | Parents completed three sessions: "(a) a goal setting session; (b) three filming sessions of parent–child interaction in the family home, and (c) three shared review sessions in which three short video clips (demonstrating attuned responses linked to the family’s goal) were played so families could microanalyze and discuss." (quote) |

| Video feedback of Infant‐Parent Interaction (VIPI) | ||

| Høivik 2015 | To investigate "in a heterogenic community sample of families with interactional problems, whether VIPI would be more effective than standard care (TAU) received in the community" (quote) | VIPI involves at least 6 consultation sessions over a maximum period of 3 months focusing on (1) "Initiative of the infants to contact caregivers and initiate pauses in the dyadic exchange" (quote); (2) "Responses of caregivers" (quote); (3) "Following the child" (quote); (4) "Naming" (quote); (5) "Step‐by‐step guidance" (quote); (6) "Directing attention towards social interaction and exploration" (quote). In this study, "families in the VIPI group received eight video feedback sessions, with the last two sessions tailored to meet the individual family needs regarding any of the six topics in the manual" (quote). |

| Video self‐modelling with feedback | ||

| Benzies 2013 | To explore if fathers of late, preterm children who received video self‐modelling with feedback intervention would have better father‐child interaction skills when the child was 8 months old than fathers who received information only | Self‐modelling "involves the father's active participation that increases his cognitive awareness of specific behaviours such as infant cues and how to stimulate development" (quote). The intervention involved video recording a father‐infant play interaction and providing positive feedback and suggestions to enhance the interaction and language development. |

| Video feedback (non‐specified or other) | ||

| Bovenschen 2012 | To assess "the effectiveness of an attachment‐based short term intervention using video‐feedback" (quote) | Up to 10 sessions of home‐based video feedback |

| Green 2010 | To test a parent‐child communication‐focused intervention in children with core autism | A parent‐mediated communication‐focused intervention: "The intervention consisted of one‐to‐one clinic sessions between therapist and parent with the child present. The aim of the intervention was first to increase parental sensitivity and responsiveness to child communication and reduce mistimed parental responses by working with the parent and using video‐feedback methods to address parent‐child interaction... incremental development of the child's communication was helped by the promotion of a range of strategies such as action routines, familiar repetitive language and pauses...After an initial orientation meeting, families attended biweekly 2 hour clinic sessions for 6 months followed by booster sessions for 6 months (total 18). Between sessions families were also asked to do 30 mins of daily home practice." (quote) |