Abstract

The transition to academic leadership entails learning to utilize an enormous new collection of skills. Executive leadership coaching is a personalized training approach that is being increasingly used to accelerate the onboarding of effective leaders. Vanderbilt University Medical Center has invested in a robust coaching strategy that is offered broadly to institutional leaders. This case study details the early transformational learning of leadership skills by one new institutional leader in the first two years in an academic leadership role, telling the first-person account of the experience of being coached while independently leading a division of hematology and oncology at a highly ranked medical center. Over two years’ time, assessed in 6-month intervals, the academician transitions into the role, and using scenarios from regular practice in this position, learns to incorporate core leadership principles into the daily activities of running a division. The transition to academic leadership involves a transformation; a conversion that can be accelerated, guided, and applied with a greater deal of sophistication through intentional coaching, and the application of principles of behavioral science and psychology. Much like the process of coaching a high performing athlete, an elite academician can be trained in skills that enhance their game and succeed in creating a winning team.

The academic medical center (AMC) is an interesting social organization, made up of highly accomplished and well-educated people, brought together around a variety of missions and motivations: education, patient service, research, community building, financial margins, and citizenship to name a few. Moreover, the leadership of AMCs almost entirely comes from within this community, drawing people with talents in science, teaching, clinical research, and service into roles that industries reserve usually for MBAs, lawyers, and other professionals who undergo rigorous guided training. Fortunately, academics are well-equipped with skills in lifelong learning, focused curiosity, and tend to be ambitious to a fault. Thus, there is a steady pipeline of budding leaders in AMC’s eager to tackle new challenges that will further their missions. Like major industries in the public and private sectors, the demands of leadership are significant. How to navigate the transitions from physician, teacher, or scientist to academic leader is not covered easily in any text.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center has adopted a model of Leadership Coaching, akin to the Trusted Leadership Advisor model (Wasylyshyn, 2017). This case study details the experience of one new leader (first author), freshly plucked from the medical science proving ground. Accounts and description of the experiences and intentions of the leadership coach, Dick Kilburg, provide insight into the processes applied in facilitating this transition. Finally, observations of the transition from the vantage point of the primary supervisor (Department Chair, Nancy Brown) provide a further description of the coaching effect on the early development of an AMC leader. The experience of the client, Kimryn Rathmell (Kim), is told in first person narrative format—fitting for the intense and personal experience that accompanies the transition to a leadership role.

Keywords: Executive Coaching, Trusted Leadership Advisor, Leadership, Management, Academic Medical Centers

Introduction

By way of background, I was recruited to the position of Division Director for a medium/large division of hematology and oncology (~90 faculty and staff) from a position as an academic physician scientist, with experience in graduate and medical school education. This position offered a chance to develop a uniquely blended clinical/translational/basic science unit around cancer, in an environment that seemed supportive and well-aligned with my world view. I didn’t want to leave my prior institution, but I was at the 12-year point in my academic career, and feeling restless. I considered that this might be a chance to learn something really new, and be a part of something much bigger than my own research. Over the course of my first two years in the position, that was proven to me to be definitely true.

I had requested a coach in my initial negotiation, realizing early that there was a lot I didn’t know. However, I wasn’t sure about having a coach that was picked for me. When I learned that Vanderbilt provided coaching services to many people in the leadership structure, including people I admired greatly, I quickly assented. The idea to have a central person simultaneously working with a large number of academic clients who interact on many levels is either brilliant or incredibly foolish. I am now convinced it is the former.

Armed with a strong recruitment package, a phenomenally detailed binder of everything a division director needs to know (well, what you need the first day, not what gets you through the tough parts that come later), and a new and enthusiastic division administrator, I embarked on this journey. The division at the time had a faculty skewed toward junior, but with some notable heavyweights. There was a lack of structure following a rapid series of transitions in the past few years. Fortunately, the division seemed to be making money, or wasn’t losing ground anyway. But the reputation of the division had slipped. Institutionally, all the pieces were there, the motivation to be leaders in the fields of hematology and oncology was still clearly felt by many of the faculty. Nancy undoubtedly saw this division as one with real potential and put a remarkable amount of faith in me. She met with me regularly in the first months, but largely left me to my own devices—providing more guidance than instruction. She provided a lifeline and was never dismissive when I needed to call to get clarification or direction. I felt fully supported, while simultaneously completely empowered to do what needed to be done-within reason. It was terrifying.

The First Six Months – Finding My Feet

from the perspective of Kim, the client

First big rodeo

I was armed with some good advice from Nancy going into the start, which was to read The First 90 Days (Watkins, 2005). This was my guidebook, and if nothing else, it gave me a framework with which to approach the transition, and what to even do the first days. I set about making some basic organizational structure (my first day was a Tuesday, the first day of September—we had a faculty meeting, and that first Tuesday of the month at 8 am became the time for faculty meetings going forward). At that point, the atmosphere of this division was tense and guarded. The communication and body language leading up to the first meeting suggested I would first have to earn their trust. We opened the faculty meeting with me sitting down in front. I channeled my mother (a great lover of ice breaker party games) and asked everyone to introduce themselves, how many years they had been at Vanderbilt, and to tell us all what was their favorite snack. My mother’s gimmick worked. People visibly relaxed, and it turns out that snacks reveal some interesting and quite complex insights into people. Mine is cheese.

I tried to meet with everyone I could, people inside the division and outside, to ask structured sets of questions: what worked well, what wasn’t working, what was the first thing they thought I should do. I took detailed notes. I was struck by the things I learned, having done what I thought was a thorough kicking of the tires in the interview process. It felt like every day one of my queries was unearthing something new and messy.

I met Dick about a month into my new role, so I was still unsteady, still exploring, but starting to get the picture of the work that lay ahead for me. The timing was perfect, since the enormity of what I needed to integrate was already overwhelming. This visit, lasting nearly two hours, covered a huge amount of territory. The first question posed to me was probably intended to develop an immediate close space—the opening salvo “tell me when you first realized you were special.” This question made me uncomfortable, and set me up to be comfortable being uncomfortable in that room. The session continued with him taking down details of my personal and professional history and probing each episode a little deeper to understand how I had experienced it. This served the multiple purposes of giving him the perspective of what my background was, the experiences I would likely draw from in making leadership decisions, as well as creating an expectation going forward that this was a place where it was safe to be candid. Moreover, it was the first realization for me that I could recognize and potentially utilize these life experiences in my leadership, which previously had been purely instinctive.

His comment after the initial introduction: “So, this is your first big rodeo!” That nailed it, and more importantly he followed that up with: “Well, don’t worry, this isn’t mine.” Although I was being called out for the novice that I was, I was also thrust into a space where it was clear the expectation would be for me to quickly get this figured out, and I had a guide. Many of the probing questions of that first visit hit me straight in the gut, showing me how much of a novice I really was, yet simultaneously telling me that the leadership of the AMC had an enormous level of confidence in me. One of many questions that exposed my naivety was if I could give him a statement of my “leadership point of view.” I couldn’t. Why on earth was I entrusted with this task, and how did I know if people would grant me the privilege to lead them, if I couldn’t even draft such a simple statement. I tried for weeks to come up with something acceptable, even though he said in time, it would be natural to do.

Coaching is such an accurate term for what I would go on to get in working with Dick. As a high school basketball player, I had wanted to be a guard. But I was 6’1” and slow. It wasn’t hard for Dick to figure out that he needed to train me to catch, pivot, and shoot. No matter what other skills I brought to the team, I was destined to be an under the basket forward, and we needed a good center. Same principles applied here—starting from this first session Dick had essentially done a skills assessment, and would help me identify my strengths, train me in the proficiencies I needed working with the assets and starting material I had to offer (catch, pivot, shoot).

Establishing ground rules

Another set of important lessons emerged in the first meeting. Some might seem like they should be intuitive or obvious, but putting them out in the open, stated as essential ground rules certainly made them more present and considered in my early days getting started. The first was the “doctrine of no surprises.” I’ve always felt like I did a good job of keeping my superiors in the loop on critical issues, but this was more. I learned to consciously think about whether I needed assistance (direct or indirect), whether it would be better for my department chair or others to have had a heads up before going too far down a specific path, or whether inadvertently hearing about something from someone not me would be detrimental. Definitely critical, and a lesson I’ve since learned to apply in my own group, with important effect, so that I am also in the loop on activities going on in my unit, can help people achieve their goals, or steer them in a more productive direction, or just be ready to provide support as a situation evolves.

The second lesson that I learned explicitly in this setting was to know how to test and know my domain. This may seem like it would be obvious, but it wasn’t. Early on, I was finding myself handicapped by previously established procedures, which routed many key decisions through a few individuals (none of which was me), and people who had either filled a space in the vacuum that preceded my arrival, or who were using the transition as an opportunity to extend their own influence. I was finding myself up against a wall constantly, and on issues that I couldn’t routinely take to the Department Chair. In those early weeks I learned how to use the doctrine of no surprises to also get myself the information, audiences, and assurances that I needed to be able to make key decisions and to execute some of my plans.

Here, having a coach who was extremely knowledgeable of the organization was critical. Rather than focusing on a specific blockade or difficult interaction, this higher-level knowledge base allowed me to learn important names of people I should get to know, and made it possible for me to get the advice (along with permission) that allowed me to expand my reach, and ultimately to achieve goals more quickly. More importantly, when I would bring a vexing problem I’d discovered—I would often learn the key questions to ask. Why do we do it this way? Who is responsible? When do you meet to make decisions? If I was having trouble communicating with a unit outside of my division, I learned to invite myself to a meeting, to learn who was in charge, who was responsible, why they were responsible, and to find some common interest or shared goal.

Coaching also helped me quickly learn how to set my own expectations for myself, the faculty, and the division. I learned right away that my view of how things work needed some refinement given the wide range of professional paths, career stages, and personalities that were represented in the division. But, everything couldn’t just take a pass, either. In some instances, I needed to quickly set rules that had no room for negotiation (Providers have to write notes on time. We don’t use profanity, ever. When I set a meeting, it starts on time.). For others I had to check myself. My standards are pretty high, and one of my better attributes is that I can really take a beating. I found it was incredibly important to know the faculty well, to know who would rise to the occasion, and who would crumble. Storms that were to come later would really exemplify this.

Do some experiments

As I reached the end of the first 90 days, which flew by, I needed a new plan. I’d reveled in the familiar line of investigation that structured inquiry offered. I’d gained an immeasurable level of new knowledge about the division and its people, but I hadn’t made many major changes. People were looking for me to do exactly that, but I was finding it hard to prioritize the problems, to decide what changes would be most accepted, readily adopted, and have durable impact. One of the most helpful pieces of advice Dick gave me early on, was to view this whole adventure like a research project. “Do experiments,” he said. What? In the early months I wondered how I could do experiments with people’s careers, with the multimillion dollar budget I suddenly oversaw, and with an enterprise that provides care for thousands of patients with cancer and blood disorders? He said it again, “you are a scientist, how else will you learn how this place works? You need to test conditions; you need to put things together in ways that haven’t been done before; and, you need to learn what works here and what doesn’t work.” As I began to get a sense of the enormity of the task at hand, doing some experiments began to make sense.

That advice was golden, so early on, because it allowed me to try things that I might have overthought, and thought better of. Like so many students I’ve had in my lab that couldn’t get started because they were trying to design the perfect experiment, it would have been easy to get trapped in a status quo that I might never break out of. Instead, this advice gave me the permission to fail. Like training a student at the bench, I had to learn to do bigger and bigger experiments. There is a literature on this (Campbell, 1969), that brilliantly nails why this approach is effective, and as an approach appealed to me at a fundamental level. To be able to risk negative outcomes in an environment that was so foreign to me, I needed to have the confidence to have an experiment result in an unexpected and possible undesirable outcome. Knowing that even “failed” experiments are usually instructive—teaching you about conditions, interactions, or uncovering unexpected data, this has for me continued to be a highly valuable mindset. Even when one of my experiments “fails” I learn about the capacity of an individual to perform, about how the university system responds to my intervention, or gives me insight into a process that may continue to be opaque, but a little less so.

I brought him an example in the first six months. I came in breathless running from a meeting that had run over, and told him “Well, I just did an experiment that might have failed badly.” For weeks I’d been hearing about the disintegrating relationship between a group of inpatient providers, and an outpatient team. Finally, I invited all the stakeholders to a meeting to come to discuss these issues face-to-face. It went poorly from the start. The inpatient team led with a list of demands and accusations that the primary team was poorly managing their patients and not following guidelines. The outpatient team members were heavy handed and condescending in their responses. Much as we tried to direct the conversation to making forward progress on how to manage patients, the atmosphere kept getting worse. Some of the participants burst into tears, others assumed disengaged body postures, one faculty leader started trying to find a middle ground, but wasn’t going very far, certainly not far enough—mostly being defensive about the function of the clinic, which was highly regarded in the institution as a successful program.

When I shared with Dick that I’d just walked out of this storm of my making, he smiled broadly and told me all the reasons I should be thrilled. I think he even started with “Congratulations.” 1) they came to the meeting; 2) they were comfortable airing grievances in my presence and talking candidly; 3) they showed that they all really care about what they are doing; and 4) we had in one hour learned so much about each other, the system, and the weak links in our program, that we had created a much bigger experiment.

It was all true. By the end of the meeting we had learned that the tension was largely around a few patients who never made it into the outpatient setting. These patients are medically difficult to manage, have social issues that cloud their medical problems, and several had developed strategies to play the inpatient team against the outpatient team. At the point of this breakthrough, there was a brief moment when the groups were on the same side—realizing they were BOTH being manipulated. I had left them with a challenge: that I would support a project of their choosing to address the unique needs of this small list of patients, that they had to tackle together. Believe me, the meeting didn’t end with anyone smiling. They were emotionally spent, and I gave them work. They weren’t pleased with me or each other. But in the end, they did take on this project, and when implemented, the program was viewed as successful on many fronts. Although all of the issues are not completely resolved, we continue to make progress. Most importantly they have evolved to function as a fluid team between the inpatient and outpatient experiences, and have learned to be creative in solving some of their own problems—making a truly unique integrated clinic/inpatient medical care program that I would argue rivals any care program in the U.S. This didn’t happen overnight, and the current state involved changes in our management of urgent care, creative structuring of the inpatient service, modifications in compensation models, and innumerable other small revisions. I’m getting ahead of myself. However, I never would have dreamed that experiments in month 3 and beyond would so rapidly lead to us growing one of the most successful and innovative programs of this kind in the country (in my humble opinion).

Every encounter, a new learning opportunity

After a couple of sessions that set the stage, and created a confidential and non-judgmental environment, knowing that we could work through any issue no matter how big or how small, we started to tackle some of my major leadership growth areas—using ongoing issues in the division in our meetings as an abundant source of learning material. I’d come into each session with a small list of ongoing problems. Usually, in the weeks leading up to the meeting, I’d jot down some thoughts about topics, settling on one or two gems to bring to our session. Unfailingly, one would emerge as the winner, and inevitably provided us more than an hour’s worth of material.

Hot topics included establishing myself as the leader, reigning in wayward faculty, balancing the many components of fairness, understanding the fragility of faculty, and the value in structured role definitions. All of these lessons, learned through analyzing the real world scenarios I’d bring to discuss, equipped me with abilities to assess situations and to have language and concepts at the ready for unfamiliar conversations that were to come, but would later be assimilated into a normal day. More importantly, Dick worked from the foundations of that original session, and subsequent knowledge about my values, beliefs, and motivators, to give me skills that I could use while simultaneously drawing from my own personality traits and personal experiences. The result, at the end of 6 months, I felt ready to tackle hard problems, and was having more comfort in the role than I could have ever imagined, because I could step into many foreign situations, able to be me.

What were the special leadership goals I attained in the first six months? I learned who was who, and what the major issues were. I learned to use skills I had in observation, investigation, and experimentation to apply them in different scenarios as I figured out who the key individuals were in the institutions (some with titles, but some of the most influential, without), what strengths they had as well weaknesses, when I would be able to make progress or would be stymied, where I could turn for assistance, and how to use my own personality to be able to gain early footing. The next step of developing my voice and abilities would have been impossible without this foothold.

Coaching Observations and Strategies, First Six Months

From the perspective of Dick, the coach

I have been very fortunate to work at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in various capacities for approximately 25 years. I’ve grown to both know the institution and its people fairly well for an external consulting psychologist. I also have the advantage of having been a faculty member at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and at the Carey Business School at Johns Hopkins University. Between those appointments, I had almost continuous contact with and worked in AMCs. Those decades of experience have enabled me to develop a type of expertise very specific to these institutions. Between program leaders, division directors, department chairs, and deans at various levels of management, I would estimate I’ve helped to onboard hundreds of highly talented faculty into leadership positions. The description of our work together has been insightful, creative, and pushed me to think structurally about what is by now a pretty intuitive type of work in these engagements.

I would highlight several issues in relationship to the summary of the first six months:

First, I’ve learned how to do an intensive, intuitively based, and rapid initial assessment of a new client based largely on a semi-structured set of interview questions. I’m intensely interested in the major professional landmarks in the person’s history as well as key aspects of his/her personal life. The underlying purposes of those questions as Kim described so well are to formulate as good an initial Theory of Mind of the Other (Malle and Hodges, 2005) as possible in a couple of hours. That type of mental model enables me to both empathize effectively with the individual as a person and as a leader in a specific phase and stage of development. If I do it well, it simultaneously serves as the initial foundation of our working alliance. There is nothing as effective in building a human relationship as having the experience of being understood by another person. Virtually every individual who has such an experience is much more likely to grant the other more trust, be more candid in revealing personal and professional challenges, and to be open to listening to new ideas. Understanding and using the well-researched aspects of “common factors” (Stevens, et. al., 2000) in formulating therapeutic relationships provides substantial structure and process support for these openings in coaching engagements.

Second, for the majority of onboarding assignments, I’ve come to expect that the client may not have thought consistently and thoroughly about leadership in general or their specific approaches to it. Although every human has had decades of exposure to leadership theory and practice in their families of origin, educational and acculturation experiences, professional lives, and in their own personal lives, for the most part, this knowledge, skill, and ability resides as a type of intuitive complex that is consulted and used as the situation demands. It’s exceedingly rare in my experience that new leaders have developed a consistent, coherent, and effective personal approach to the way they do the work of management. Tichy and Cohen, (1997) and others refer to this as having “a leadership point of view.”

This squares very closely to my own experiences as a leader, consultant, and coach. As a result, I’ve learned to probe this issue very specifically and often in my first meeting with a client. If the person can articulate such a view, it helps me to understand the ways in which they are likely to move in their work in the organization and even highlights potential areas of vulnerability based on what s/he believes and articulates is important. For the most part however, the reaction described by Kim is pretty typical to the question “can you describe what we could call as your leadership point of view?”

Since it is likely that the query exposes some gaps in the client’s education, training, and experience, I assume that I will be challenging their self-esteem pretty significantly and very early in our relationship. The reaction I get most often is either a slight shake of the head or a couple of descriptive terms that reflect papers or books that s/he has read and remembered. To provide both emotional support for the potential experiences of both performance-based anxiety and shame, I am always prepared with a set of materials I’ve developed to share with new clients. These consist of a couple of papers I tend to vary depending on who the client is as well as a formal exercise I’ve developed for creating a leadership point of view (Kilburg, 2012), a summary of many of the most significant errors a manager can make (Levinson, 1994), a copy of types of mastery involved in becoming a leader (Kilburg, 1998, and another handout listing approximately a dozen of the most important considerations in building and managing an organization. These materials are always received with a combination of curiosity, relief, and gratitude by clients. The entire exercise is meant to both challenge and support the individual. I try to make clear that s/he has chosen to do something both important and valuable with their lives and careers. And that the work of leadership is never to be underestimated in its importance and complexity.

Finally, as described above, the ongoing work of executive coaching involves a co-created experience. With an effective working alliance started early, clients are much more willing to expose their most important issues and needs. The case material they bring to sessions provides deeply moving, vitally interesting, and truly meaningful situations that stretch inductive reasoning. From these inductive cases, sessions then can be easily turned toward the deductive principles of good leadership and management. Working back and forth between the real work of the client and the ideas, methods, and research from the combination of the leadership, management, organization development, and coaching literatures always results in a rich dialogue. I nearly always strive during these exchanges to provide both good support by letting the client describe what they are doing, trying to accomplish, or struggling to comprehend. I’m prepared to criticize when necessary, congratulate always, point out strengths being deployed or weaknesses being exposed, and to render concrete and specific advice when necessary. When I provide data, insight, or recommendations, I’m always careful to use the language of could, encourage the individual to work the case with me as a simulation, or to imagine our way into reconsidering the facts that have been presented. These summaries of some of our early work together are both insightful as to what she and I were trying to do together and highly illustrative of the duality of the working relationship in an effective coaching engagement.

Second Six Months - Defining my style (Finding my voice)

From the perspective of Kim, the client

Developing intimacy

A theme emerged early that I needed to work on, and continue to work to develop, which is developing intimacy. I was raised in the heart of the Midwest—Iowa. The perceptions that Midwesterners are friendly, but private, is absolutely true. I am naturally reserved, and was raised in a home where privacy was protected at the highest levels from all but the innermost circles. It works for my highly introverted family. We understand the distance and the quiet moments, and in true Iowan fashion, we would never intrude upon the natural social order— more is often assumed than ever said.

I learned long ago as a physician to adopt a different level of connection when I walk into a patient room than I maintain with even the nurses and other colleagues with whom I may have worked for years. But putting that level of familiarity into place in my leadership structure and style was definitely foreign. I’d learned the trick before to “check in” at the start of a meeting. I’ll be honest, this seemed nice, but it has felt highly contrived, and even a little intrusive, and also time wasting. Mostly it is counter to my sensibilities to focus on a task and get it done— without need for frivolities.

Working with Dick, I learned more about the need to allow for and even create moments of intimacy that established a foundation going forward that enabled stronger working relationships. His initial inquiry about “when did I know I was special” did that. I’ve since seen it used in various iterations over and over successfully, and am gradually becoming better at rapidly engaging on that level. I still struggle with using relational leadership, often reverting instead to transactional styles. One early week, I brought him my usual list of issues where I was running into roadblocks—several involved people resisting change (a common theme of the first year was “we’ve always done it this way”). He stopped me and asked, what did I know about this person—where they grew up, what was their motivation to be in academic medicine, what guides them spiritually? (Kilburg, 2000, 2006, 2012). I knew none of that, and frankly, didn’t see how that was any of my business or was relevant. He encouraged me to be a scientist again, and ask questions, peel back the layers and figure out who I’m dealing with. It doesn’t matter what the situation was—he was right, and just asking a few questions allows you to connect more quickly (rather than slow down the transaction), helps you understand the situation (and maneuver to more mutual advantage), and the magic I hadn’t appreciated—creates a tiny invisible bond that deepens a relationship in the longer term so that transaction is easier the next time.

It seems simple, but I still find it exhausting. I have to consciously engage this way with new people, and yes, maintain that with people I have now been working with for years. Yet, every time I have established that connection, it’s been positive. More than being a scientist, I equate this strategy to asking the family history and social history in a new patient encounter. Far more than half the time, the actual information is irrelevant. In my clinic, for what I’m making decisions on, I only need to know if they have a family history of lots of kidney cancer, and if they have an addiction or social situation that will be problematic to their treatment. But the rich history and the moment when a patient stops and tells you about their mother with Parkinson’s or their child with Down’s syndrome, or the struggle they had to quit smoking five years ago—is a treasured part of the history and physical for me. Now I know why.

Developing Style

I was helped tremendously by learning to recognize what style I was using, and what voice I was drawing from. It had not consciously occurred to me that in different situations I revert to strategies I’d adapted from my parents, colleagues, mentors. Much like as a parent I’ve on numerous occasions suddenly heard my mother’s voice coming from my mouth, I learned to recognize which voice I was drawing from, whether it was a former mentor, Dick, often my department chair, or increasingly my own new set of voices. I learned to recognize the different times and situations I would instinctively draw on unique voices. My intuitions weren’t always right either, and learning how to anticipate situations and use a more conscious approach was incredibly liberating. While my fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants approach was mostly working, it was stressful, and disorganized, and probably confusing to people who were trying to figure me out as a leader—it was at least to me.

In the months that followed, the effort spent in paying attention to my style, and recognizing which style was effective, which ones emerged when I was stressed, and learning to select styles that were more likely to be successful, was an important step in making me comfortable in this role. Drawing with intent which voice to apply to a situation is a skill that is highly underappreciated. It’s like having a set of tools, which you can use more effectively if you match the tool specifically designed for the task in the way it was invented to be used. Challenges that arose in the second period were harder, and I found times that I’d pick the wrong hammer, but over the next few months I learned that each interaction is an experiment, too. Sometimes testing my own abilities, or trying out a new range in my voice.

Shame

During this time I talked a lot about shame in my sessions with Dick. I have a strong sense of shame hardwired, and had to learn two important things. First, that most people react strongly to shame, and second, that the extent of their response varies, so this powerful tool has to be applied with caution. Applying just the right amount can help elicit some insight that was lacking previously, but too much, and the results can be dramatic and negative. I had not anticipated how much my approval would matter to people. It may be that this is somehow more true for women leaders than men, but using authoritarian language and body posture often backfires for me—resulting in overly defensive responses from colleagues, or worse. I similarly struggle with conveying anger, or frustration, without it being perceived as something more judgmental than I intend. A little bit of disappointment can go a long way. I learned to practice the kind of questions and communications that can help people see where their actions or behaviors have negative consequences, so we can get to the next step, and achieve solutions that are better for everyone.

I also learned that people are not as fragile as they sometimes look when challenged and simultaneously treated with respect (Goleman 1995; Kilburg, 2012: Woodruff, 2001; Wurmser, 1981, 2000;). I’ll give an example. I was working on an operational alignment problem with two units outside of the department. In order to remediate the problem, and ensure cooperation going forward, I had to come to the meetings prepared with documentation and willing to disclose gaps in compliance publicly. This naturally elicited a type of public embarrassment, but I delivered it not in a “gotcha” kind of way, but with an approach that valued the contribution of the other parties to achieve a mutually beneficial goal. The result was a strong partnership, where we all feel like we invested in making this program a success. The approach allowed all of us to metabolize the amount of shame that was appropriate to the need to recognize we all owned pieces of the problems and helped us mobilize constructive as opposed to defensive reactions to the data and our responses to it.

Developing Structure, and my Identity

After 6 months being in many ways an observer, it was time to get busy. We had put in place a structured faculty meeting, with an agenda, and had settled into some recurring meetings that moved beyond the dyads of me meeting with individual people. First up, I had discovered several of the meetings that existed before were essentially gripe sessions. Although I wanted to listen, things were becoming repetitive, and it was depressing to allow these diatribes to go on. In at least one session with Dick, we talked about meeting strategy—developing the agenda, directing the conversation, shutting down unproductive discourse. This toolkit was a big help, as my meeting tolerance is generally low. Knowing: Why are we having the meeting, what do I want to gain, whose opinion do I want, and what are the action items, were key elements I hadn’t always planned before each meeting. I came from running lab meetings where the goal is always the same—interrogate the data and offer advice to enhance the science. Most meetings now were different, and I needed to have a style that was predictable. What worked for me: focusing on a small number of items mature enough for discussion; short discussions arriving at consensus (often starting from a limited menu of options); seeing and establishing value in creative suggestions, and in the absence of consensus, the decision is mine—and I own it.

In the second six-month period two important things happened that changed the way I organized meetings. The first was an international meeting I had arranged months earlier, before even coming to Vanderbilt. The goal of the meeting was to orchestrate a global community around a rare cancer—a lofty ideal, and when I mentioned this to Dick, he knew immediately I was in over my head and gave me a load of strategies for setting ground rules, checklists for meeting enhancement, and strategies to encouraging active participation. More than that, we discussed the schedule of the day, the seating arrangement, the strategy to draw in discussion, and tools to guide discussions toward achieving a set of tangible goals by the end of the meeting. It was a wild success, and launched the founding of an organized alliance for this rare tumor. In our second meeting, we saw abundant new research on this cancer type, the first clinical trials for patients with this cancer, and a committed level of enthusiasm as a burgeoning field that would not have happened had I run the meeting lab meeting style.

With so many faculty, and only 24 hours in the day, it was clear we needed to build some more teams. One team already had a strong section chief. I agreed with his continuing in the role, and after a few minor skirmishes over authority, we developed a good working relationship. The RACI tool (responsibility charting) (Center for Applied Research, 1994) that I learned about early in my coaching worked wonders. But no one was effectively overseeing other sections. In addition, the clinic structure was in need of physician input, and there was minimal opportunity for any communication between staff and physicians or physician leadership. When I was in my fact-finding mode early on, one person told me in no uncertain terms that I was not to speak to nurses about anything other than patient issues without nursing leadership presence, even to ask questions about how things work. Later on, I knew better than to accept that dictum, but early on, I hesitated.

Here, Dick provided a resource that was absolutely invaluable. He was a sounding board as I went through the mental machinations of who would fit where. He helped me assess individuals’ strengths and weaknesses, and guided me in providing proving ground opportunities for people I was considering in my leadership structure. I also learned about patience, discretion, and how hard it is to effect change, when there are known and unknown expectations and biases among individuals with vested interests (even when I thought individuals had no specific investments in various issues). I learned about the power in changing an organizational chart as well, and that inadvertent slights can lead to longstanding wounds when a line is drawn one way, and not another.

As in the first six months, any interaction, maneuver, or challenge was valuable fodder for these training sessions. Whether the situation was with a faculty member, an ancillary unit, a recruit, training programs, or risk management, I learned not just to pivot and shoot, but to use position, timing, accuracy, and flexibility as I perfected my jump shot. The practice was terrific, and as I transitioned further, I found I could execute these skills with less effort and more muscle memory… so that I could focus on more important parts of the game.

Second Six Months Coaching Observations: Style Management

From the perspective of Dick, the coach

What should be obvious now in the self-report is how clearly the new leader depicts the development of leadership expertise. It is well known that across domains of human activity, expertise emerges as a result of the interaction of four primary components: the inherent talent and ability of the person; the motivation to work hard to grow; dedicated practice to improve performance (not the same as gaining experience); and, effective coaching and training at key intervals (Ericcson, 2009; Kilburg, 2000, 2016). In addition, it takes thousands of trials/hours of effort to rise from being naive through the novice, apprentice, journeyperson, expert, master, and sage phases of expertise creation. After her first year, this leader had accumulated another 2000 plus hours of dedicated practice and her observations here demonstrate that very well.

The case also demonstrates several other key aspects of leadership development. Most approaches to coaching and management training tend largely to ignore the basic fact that the epicenter of effecting organizational performance comes as a result of the qualities of the working relationships among the people employed. Leaders who struggle with developing and managing intimate working relationships are often doomed to suboptimal performance. Kim came to see very quickly just how important and useful relationship expertise is to a leader (Gergen, 2009). In addition, classic components of management practice such as situational leadership (Hersey and Blanchard, 1977) and developing subordinates (Peterson and Hicks, 1996) tend to be assumed rather than specifically taught. Kim’s attention to and capacity to exercise these core competencies steadily improved during her first year in office after being exposed to these concepts and skills in coaching sessions.

The emphasis on shame in this section, really the management of negative emotions at work, also points to a key and often under emphasized issue. Leaders must be masters of emotional management, their own and their colleagues. And while positive emotions are vital (Fredrickson, 2009) in creating and maintaining productive work places, leaders also must be true artists in the constructive employment of negative emotions. When, where, how, and how much to stimulate appropriate levels of performance related anxiety, shame, sadness, and anger are key to the continuous creation of expert performance. Not being able to anticipate and taste such negative experiences tends to create complacency and a lack of commitment to improve. Knowing how to touch people in ways that will both remind them they are not doing their best work and that they need to strive harder is challenging for both leaders and their coaches. Throughout the narrative, readers can see some of the points on which I chose to push Kim emotionally. She seldom needed to be reminded that her performance had to improve. But pushing her to understand how, why, when, and how much produced both more focused experiments as well as significant jumps in her motivation to try new approaches. The sections of each of the six month intervals also demonstrate how well she metabolized my interventions and used them in her own ways to her and her division’s advantage.

What you can also see here in the second six month interval is how rapidly she began to accept the requirement to exercise authority, use various approaches to influence in her organization, and to experiment with these core elements of leadership in a number of ways and in different settings. This included her progressively becoming aware of her individual style and approach to using these competencies. Putting structures and processes in place that improved accountability, clarified role expectations, led groups to innovate, and breaking, challenging, and deploying existing and new teams of people are all in evidence. Her continuing use of her historical experience in learning how to be a competitive basketball player is also quite instructive. By the end of her first year, she understood the difference between basic leadership and management play and what more advanced expertise required.

Months 12–18: Implementing a structure that works for me

From the perspective of Kim, the client

Mentoring leaders

Two of the things that had attracted me to the job were the opportunities for growth in the fellowship program, and the group of junior faculty in the division. Mentoring fellows and junior faculty came naturally from my prior experience, and issues in developing a junior faculty member that prompted discussion with Dick were usually situational, or involved logistical considerations. These were easy problems, as these are individuals actively seeking guidance, like a freshman JV player, still building skills and finding their place on the team. It’s fun, and refreshing, and the impact can be immediate and rewarding.

However, I hadn’t given a lot of thought before to the mentoring of midlevel and senior faculty. It turned out to be a lot harder. They are jockeying to hold their position in the starting lineup, looking for MVP opportunities, and sometimes single-minded in anticipating their future. Dick prepped me that I would need to actively mentor individuals much my senior, telling me not to worry, they would learn from me if I was willing to teach them.

At the start of the second year, I’d finally assembled a structural organization that I thought would work. I had rallied the support of appropriate institutional leaders for some seismic shifts that needed to take place. It was hardly a surprise then that not everyone knew what to do in their new roles. I’d described the experience, strengths, and perceived weaknesses of team members, and been given the recommendation not to let them function independently until I was sure of what they were doing. What golden advice. I worked individually with these new key leaders in the division, developing projects for them to tackle, enabling them to score some early wins, helping pace them to balance a manageable number of active tasks, and giving them the model for success, while letting them execute their ideas. It worked, and would have failed utterly had I pointed them in directions and just said “go”.

I’m not trying to take credit for these people’s success, because they are individually brilliant. Looking back on those meetings, however, they didn’t know at first how to mesh their ideas with my style. They met with resistance in their work that I could sometimes assist with dismantling, and many of them had periods of self-doubt or mental exhaustion. Any number of issues might have derailed the structure we had put in place and the autonomy of each of these leaders. All of them are now managing their programs beautifully. Over and over again, I have found the coaching guidance of: insert myself in the situation, be engaged and present, and apply skill mentoring to all levels of individual, and then step back, to be invaluable.

These are the midcareer and senior level faculty who early on were rising to the surface, or were already in positions of some authority. Other members of the division at midcareer were also in need of guidance. The attention that I can individually provide is less, but I learned from Dick that there are specific skills I can identify in my annual meetings or hallway interactions with faculty that can benefit from coaching. He warned me not to be surprised by underdeveloped skills in negotiation, staff communication, email etiquette, and project development. This awareness helped me tremendously and allowed me not to simply criticize an individual who has a key professional deficiency, but rather to focus right on that and work to develop that skill. I have on numerous occasions taken the opportunity to say “let me tell you how you could negotiate for that XX that you need” (even when the negotiation is with me), or to deliberately place someone on a committee with a specific charge that may take them out of their comfort zone just a little, but that opens their eyes to the complexities of the system that supports them.

It is my place to judge

In one pivotal session with Dick, I brought up doing my annual reviews. I was still feeling intimidated about the process and wanted to make it a valuable experience for me and my colleagues. Since I’d be spending something like 50–100 hours doing this, I figured it better be worthwhile. My main missions were to get feedback from the faculty, and to try to hear in a closed door setting what their impressions were of Vanderbilt and where the division was headed. Apparently, that was not what I was really supposed to be doing.

Dick asked me if I could rank them all, right now, top to bottom—best to worst. This appealed nicely to my INTJ personality, and I said, sure I could. Then I’m so glad I said what I was really thinking: “but who am I to judge?” That launched one of the most pivotal discussions (of many) that I had with Dick. His message and words were loud and clear. “Your chairman pays you to judge.”

Wow!

Of course, I did judge (privately), and I had in the first 12 months learned quickly the art of having difficult conversations. In fact, these weren’t so hard. When someone isn’t writing their notes, is showing up late to meetings, or is using derogatory language in staff interactions— I can handle those conversations now in my sleep. But that is different from the annual review. In the encounters referenced above I am letting them know where the division standard is—and in general those conversations are incident focused and not individual focused. I’m very comfortable with moving on as well, and if the behavior is corrected, there isn’t any residual harsh feeling or social alienation on my part. But pointing out their individual weaknesses is another level of judgment altogether.

As I made my way through these reviews, Dick and I talked about how to me they seem so fragile—to which I had to learn that if I don’t build their resiliency then I’ve failed them again. I was afraid if they thought I didn’t generally approve of them that they’d leave—and the number of people leaving was more than I had coming in, which was disheartening to say the least. He wondered why I would want someone who didn’t want honesty and candor from their chief. I wasn’t a shrinking violet, and I told lots of people that they weren’t as ready for promotion as they thought, or that I thought they should be more X (X=visible, productive, friendly to staff), but by and large I told them how much I liked what they were doing (they were all doing something good), and used them for feedback about how they felt the division was going. Basically, I wanted them to like me. Big mistake, and while I held them accountable for the big ticket items in the first year, I held back on some of the things that could make a real difference.

It wasn’t until I really confessed to Dick that I still felt incompetent at doing these annual reviews that I made progress. Here’s why, and it felt obnoxious to say, although again I’m glad I did, and I learned again from opening my mouth... I said, “I don’t know what these meetings should really be like since I’ve never gotten negative feedback in an annual review “. This raised 2 points.

1. Negative feedback shouldn’t be unexpected. Dick didn’t say that explicitly, but saying that out loud made me realize my basic error. He let me squirm in a little shame on my own for a minute, and the point was made. I wasn’t doing a good job, and he was giving me negative feedback. Going forward I applied his original advice—mentally rank each faculty member going into the meeting. I looked at each person’s file before the meeting, and decided if based on their rank and years of service if they were meeting my imaginary bar for a faculty member—and if not, we discussed those quantitative deficiencies. Then I thought about my “division chief” expectations, and whether they were meeting them. This is a little more subjective and isn’t highly data driven—but it’s about visibility at meetings and conferences, helping with fellows, and service to the division. Then I defined in my own mind if there were any major flaws we should address. So far so good—more people wanted me to tell them this than were insulted… and some said thank you for giving them candid feedback, or some that even surprised me—saying “yes, I know I need to work on that”.

2. I’d been receiving expert negative feedback for a long time, just not in the form I had immediately recognized. His response, and those of others, have many times been designed to re-orient or recalibrate my actions. Because—right there, he was telling me that I wasn’t doing a good job. I was letting my fear of cracking some fragile ego, or of alienating my faculty members, stop me from doing the job I’m here to do, which is to develop them each to the fullest extent of their potential.

Now I recognize that letting people know I have higher expectations, and figure out on their own where they need to focus skill-building, is actually more potent than me spelling out their failings to them. They know what they are doing, and except for the most junior faculty, they know they aren’t on course. They want me to say “it’s fine, it will be all right” But it won’t be, and I’m not doing them any kind of a service in maintaining a charade. And if they are off course, then bringing it out in the open is really better for everyone.

Now I look forward to these meetings as another opportunity to get closer to each of the faculty. As a chance to set the bar, to push the faculty to be a little more insightful to their own behavior and career path, and to develop the best faculty I can possibly have.

6 HAT thinking

One of harder parts of the job is having the right attitude for the work at hand. I’d learned early on as a junior faculty member two mantras that served me well: Never let them see you sweat, and always find the positive side of any situation. In the lab, this works to create an environment where it is ok to question dogma, and to know that the best experiment is one that proves you were wrong. For students and postdocs, they need to know it’s ok to show you the data that just killed your hypothesis. Plus, if you can learn from any well-designed experiment, even if it wasn’t what you wanted to learn, then the glass is always half full. Even more so in the clinic, putting the right face on a grim situation, steering a novice resident into finding the pearl in a challenging interaction, or helping a patient understand a complex decision ahead, requires some skill at adapting methods of response. Some of this is innate, but it turns out using deliberate approaches to thinking can have a big impact on a leader’s management of a situation, both internally and to the group. However, it wasn’t always easy as I encountered situations that had broad impact on the institution.

The specific challenge that focused this for me was the following: After many years of being recruited to high profile jobs across the country, our most senior and well-respected faculty member finally took one. I had to keep the news to myself for months, so it should have been a relief when he finally made his announcement. It wasn’t. Everyone I saw asked me: What was I going to do? How would we manage without him? How would I ever replace him? What’s going wrong at Vanderbilt? It got to me, and I took it to a coaching session. His response—always to turn around to his computer and print out a chapter from one of his books or a handout he had created. This one was golden. Six Hat thinking—choosing how to approach a situation using the mood and viewpoint appropriate to the moment (De Bono, 1999). Turns out, I was unnecessarily wearing a black hat. In reacting to others—I was assuming the only response was to see the situation for what it had to represent: an unrecoverable setback, a major loss, and a black mark on my division, and therefore on my leadership. I was focusing on potential losses to reputation, our mentoring pool, and grant portfolio—constantly re-analyzing the risks, and considering how we could weather this storm.

However, what I learned in that discussion was that while this black hat thinking has value in many scenarios - when it is important to get deadly serious and figure out the path forward with minimal casualties in high risk situations - this was actually a white hat scenario: a time to take a neutral approach to the risks and collect facts, and an opportunity to shake some things up in the division. The situation soon turned to a green hat: cause to celebrate the success of one of our faculty and consider how new opportunities could be applied. I am trying to wear my blue hat more often on a daily basis—staying above the fray, and controlling the way I think about the problems. That handout stays on my desk—so I can consciously choose my hat, especially on days when it needs changing.

Now, looking back, this period allowed me to learn to focus, avoid distraction, and keep my eye on the ball. Applying the same drills as I’d had the first year, I was learning how to play the whole game, and with my team be ready for a tight game in the final minutes. Cool, calm, and aggressive, and deaf to the roar of the crowd as you tie the game with a few seconds to go.

Coaching Observations into the Second Year, Months 12–18

From the perspective of Dick, the coach

When working with a new leader, there comes a point in the exchanges when you get the sense that the person has begun an existential struggle with becoming a true authority figure, a person with real power in an organization. Most humans only come to see and understand this through their interpersonal relationships; when they say or do something that moves another person to think, feel, or behave differently. For folks that have formal position power, acknowledging and truly accepting that they have been given the authority to dramatically influence the lives of the people who report to them is a critical phase in adapting to being a leader. This leader describes both her acclimation to this reality and her use of our coaching relationship to explore these issues with great sensitivity.

Our discussion of recognizing and learning to use judgment realistically and effectively enabled her to become much more comfortable with what she really had to do to manage her faculty and staff. The combination of creative inquiry on my part and constructive confrontation that creatively challenged rather than simply pushed her around is embedded in what she remembered about these discussions. Many approaches and conceptualizations about leadership and management behaviors emphasize focusing on strengths, using empathy, and maintaining constructive working relationships. All are very important, but if subordinates do not perform well or do not work hard to improve their knowledge and skill, they absolutely must find themselves in a constructive, challenging, and truthful conversation about the need for concrete and significant change and the consequences if it does not happen. Reminding Kim that her boss expected her to make such judgments and no one else took immediate and creative root in her approach to management. It was not that she was unable to do this. She had decades of experience with mentors, coaches, teachers, parents, etc. who had provided great examples of how to do it well and poorly. It was mostly her accepting not only that she could do this, but most importantly, she had to do it and do it well for her organization and people to continue to grow and thrive.

There are many such moments in a coaching relationship when metaphorically, a coach puts his/her arm around the client’s shoulder and says something like, “let’s look at this together. Do you think your approach is working? If not, then what are you going to do about it?” When clients change their behavior as a result of such a dialogue, there is often what I call behavioral evidence presented at subsequent sessions that the approach has indeed changed and results are moving in the right direction. Such moments of truthful confrontation and active engagement are sometimes difficult to recognize diagnostically, and they are always challenging to implement in ways that move both the client and the working relationship with him/her forward constructively.

The description of our discussion of De Bono’s work further illustrates that coaches must have an array of methods, ideas, experiences, and resources to apply when clients demonstrate the limitations of their own knowledge, skill, ability, and experience. Most people have not been formally exposed to cognitive theory, research on decision making, problem solving, conflict management, or a host of other managerial challenges. Having resources at the ready when these scenarios arise can very often significantly and rapidly move a client in a better direction or to find an answer that they knew existed but just did not possess. I frequently use De Bono’s work to enhance discussions of ways of thinking about problems in leadership. It’s quite natural for me as I’ve been interested in human cognition for over fifty years. And I can heartily recommend De Bono’s small paperback book as an easily accessible entry point to help leaders think about the quality of their thinking. This is an issue publicly and privately on display every minute of every coaching session.

Months 18–24: Recreating my mojo in a national arena

From the perspective of Kim, the client

Mastering the juggle

One of the hardest parts of the new job, was the expectation that I could continue to excel in the lab. In some ways this was easier than it looked. I had to be structured in my laboratory— consistent in meeting with people in the lab weekly, committed to attending lab meetings and other meetings where my attendance served a clear purpose, and keeping up with papers, abstracts, and grants. Fortunately, the lab had benefitted from the move and the new connections and collaborations that come from opening the doors again to fresh ideas. I’d also attracted a strong group of students and postdocs, who joined knowing they were working for a mentor whose time and attention was divided. They generally thrived. I, however, had never felt more disconnected from my research. I like to keep at least a step ahead, and was finding myself more often 2 steps behind, learning about papers from the lab, agreeing with ideas, but not bringing them. Struggling in the wee hours to develop the lab narrative that I could coherently deliver at meetings and seminars, these are the vital forms of communication that develop a laboratory program, and I was wondering if I was really keeping up. Talking through this new reality with Dick, I learned new styles and reset some expectations. However, recreating my mojo involved prioritizing the research again, and learning to enjoy it from a different vantage point, as the mentor who gets the opportunity to delight in the finding, rather than guide the mentee to the discovery, and then brainstorm together on the next steps. I had to come to the realization that my lab research is really what defines me personally, and having an outlet for basic discovery and mechanism-based investigation is really fundamental to my core. But it had to happen differently, and my lab staff had to learn to be more independent, and as a result, they flourished.

Harder yet, was the new role I was expected to play in the clinic. I love being a doctor, and I found my niche early on being a sub-specialist in kidney cancer. Due to several departures around the time of my arrival, I was left as the senior clinician in my section. In order to keep up with demands, I took on a new role—leading the clinical effort in my specialty, serving as site PI for over 20 clinical trials, and expanding my clinic to accommodate a large influx of new patients, some with kidney cancer, but also bladder, prostate, testis. I saw more patients in a year than I had seen in probably the prior five. I can say without question that this was the hardest part of the new job. And it was probably the best thing that happened to me.

That exposure let me view from the front lines the challenges that I had heard about in the clinic. “Fix the clinic” had been the number one request on my initial tour. By seeing first-hand how the clinic operated, I could both identify concrete ways to help, and empathize with the day-to-day lives of providers in the facilities. The same was true for the clinical trials exposure. Finding myself at the center of the clinical research program, I used the same venue to observe the challenges to the administrative design of this essential mission. Acknowledging that the division is broader than any one person can really experience fully, this was a remarkable gift to be able to witness up close how the primary operations of the division worked. It was exhausting, and invaluable, and I learned to incorporate it into my daily routine, along with so many other new tasks.

The search for truth

While many things in the first two years inspired me to want to make change, one of the most challenging things in the job was the many facets of the AMC that impacted my unit but did not report to me. Aligning goals was often hard, and sometimes others were not interested in even starting a dialogue. Trying to effect change from a personal level to an institutional level, sometimes seemed nearly impossible, and the politics varied from obvious to covert. Working through yet another vexing problem, Dick asked me to articulate the trait that I valued most— easily that’s fact, honesty, truth. I think the search for truth is a virtue that strikes me straight to my core, and drives my focus as a scientist, steers my fundamental decisions, and guides my inner compass. I can’t lie, cheat, or deceive. That sounds like an idealized view of myself, but it’s true. I can’t. I have an incredibly bad poker face—deceit feels so uncomfortable that I can’t contain it for more than minutes or hours.

It’s not like I can’t be socially aware. But I don’t hold my cards very close. One of the things I’ve found very hard in the new position is to keep secrets. Just to be clear—I don’t violate confidentiality - I don’t tell people other people’s business, I don’t blurt out what I’m planning at the drop of a hat. But I had trouble initially with the many conversations that might be needed in orchestrating a complex maneuver. Having no poker face, I get fewer chances to explore the situation.

Dick took a look at me as I put into words what I’d only ever felt and used as an intangible guiding principle. He understood and articulated explicitly what I experience—that experiencing untruth is like a punch in the gut. Our conversation came back around to the issue I was dealing with, and how I dealt with the covert nature of politics in the AMC. I learned that I need to know my own areas of blindness and vulnerability. Although we discussed strategies to get around this complex, I still have to consciously manage this aspect of my leadership style. On my side, I rely on my naturally quieter nature. Being able to keep my own counsel is a huge virtue. I also find that maintaining a publicly uncommitted pose, and allowing silence to fill more voids, I learn more than I thought possible. I don’t lie, but I’m not as forthcoming as I once might have been. And I am learning to use my own discomfort with deception as a way to create a working environment where transparency is valued at all levels.

Being the voice of reason

In addition to the Vanderbilt day job, I was also serving on numerous committees nationally in organizations in my field. Serving on these committees is a great way to be in touch with the decisions, trends, and messages being conveyed on a broader level, and as a member, is relatively low stress, with defined tasks, and clear reporting duties. I hadn’t realized how different and difficult it was to function at the higher levels in these organizations. As I began working in more leadership roles, I found myself sometimes stunned by the extent of ego, politics, and indecision at the higher ranks. I also observed clear acts of bravery, brilliant tactical strategy, and steady leadership. It was clear that strong leadership was essential for navigating in these organizations

A few of these challenges were unsettling enough to me that I sought advice from Dick, who showed me how his experience in having long been a student of human behavior was an incredible asset. He was able to help me anticipate emerging catastrophes, to enable me to be prepared to keep groups functioning in an orderly way (even from a position not high in leadership), and to recognize group dynamics in a way I had not before. Here and in the division was an ideal classroom for learning organizational culture (Levi, 2001; Schein, 1990; Wheelan, 2005). Simple strategies of listening, being observant, verbalizing rules, and following other doctrines we had covered in my home leadership role, such as limiting surprises, including everyone, and enlisting allies were equally valuable here. I found myself resolving in my own mind the issues I was most passionate about and clarifying my fundamental commitment to these organizations.

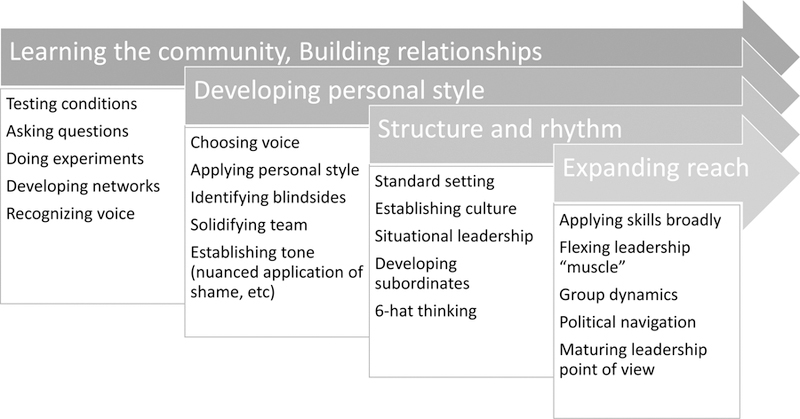

The same drills followed here, with situations where I learned to anticipate where the other players would be, what the opposing team would be doing, and where I could make the biggest impact. This experience unfolded in discrete developmental stages, although the lessons learned early were repeated in increasingly sophisticated ways as time went on, as depicted graphically in Figure 1. Transitioning to academic leadership involved intense training, with coaching sessions month in and month out, that allowed me to build up a set of skills and a team, ready to move on to the next round of the tournament.

Figure 1. Timeline of developmental stages and key lessons in the transition to academic medical leadership.

The topics and skill developmental processes of transitioning into a leadership role emerge in a highly individualized way. However, this reflection reveals the stepwise development of increasingly sophisticated skills, and the continuum in which these skills are practiced, maintained, and further honed.

The path forward

Early on, I puzzled over the question that had been posed by Dick about defining my leadership point of view. Months and then a couple of years went by with no specific words that fit the bill for me, or offered the description that I could hold as uniquely my own. I now realize that this statement is one of the most straightforward descriptions of who I am. Here it is:

“I lead through example, and I reflect high moral and ethical standards. I value integrity and transparency, and relish in sharing ideas and exploring new territory. I tolerate failure, as long as the effort was honest and rigorous. I value people and organizations who want to work together to achieve a common goal. My expectations for information sharing are high, and my meeting tolerance is low, so I appreciate direct and efficient communications. Finally, I perceive mentorship in an organization as a core value. Ultimately, I want every member of my team to succeed to the very best of their capacity and potential, and that desire drives all of my leadership decisions.”

I am regularly queried about “my vision” for the division, and I will be honest here, that the question always challenged me. When candidates or faculty would ask me that, I often wondered what kind of answer they are looking for, since my vision is really just to be exceptionally good at as many things as we can. But I recently realized why I struggled with this question, which Dick probably figured out on day 1. I am a scientist, and no self-respecting scientist knows what the story is completely when they develop the hypothesis and do the first experiments. The results guide the outcome, and the better the results, the more unexpected the outcome will be. I have no idea what my team will look like in five or ten years, but I know we will have grown in exponential ways, that we will continue to test conditions to find the optimal parameters for success, and that we will experiment together until we can look back and see what we learned, and what a phenomenal legacy we built.

Coaching Observations at the Completion of Two Years (24 Sessions)

From the perspective of Dick, the coach

This last section of Kim’s report enables us to look at several additional issues. Most importantly, as leaders continue to develop and succeed they most often get opportunities to be involved in higher and higher levels of organizational work and more complex problems. This always means s/he inevitably is drawn deeper and more comprehensively into the matters of politics and influence in organizations. This is a subject much discussed and written about (Kilburg, 2000, 2006, 2012; Pfeffer, 1992). Suffice it to say that in my experience, it is the rare human being who comes to any new managerial or leadership position thoroughly prepared to face the appallingly complex and difficult matters involved in getting individuals and groups of people to agree, align, and move together to accomplish something together. Helping someone develop political acumen and influencing skills is among the most difficult areas of coaching.

Many individuals come to their leadership positions not only undereducated and underdeveloped in these areas, they often possess a set of attitudes, values, beliefs, and biases that explicitly put them in a position in which they deny or denigrate the importance of these processes in human affairs. Such clients often experience precarious adjustments to their new positions and institutions until they actually learn that they cannot avoid politics, power, and influence. Once that happens, they then begin the even more difficult tasks in learning how to develop expertise in these arenas. Again, the fundamental principles involved in creating manageable experiments serve clients and coaches well.

Involvement in national organizations allowed us to peer into these processes and structures with such penetrating clarity that there was never a problem with either denial or denigration. The work was immediately focused on diagnosing what was happening, creating useful maps of the group dynamics, organizational challenges, and interpersonal landscapes that allowed us to discuss various tactics and strategies she was experiencing along with those that she believed she needed to employ herself. As in the other sections of the paper, what is on display here is how rapidly Kim came not only to understand what she faced but also how adept she became at reading, reacting to, and influencing these situations. This included several discussions about the desirability of acquiring more power and influence by running for higher office in these organizations. All of the lessons learned in these settings, she was able to generalize back to her home institution and to the work she did every day.

Kim ends her report on her first two years with a succinct description of her leadership point of view and how she has integrated who she is as a person, as a scientist, as a practicing academic physician, and now as an increasingly effective and confident executive. Being able to articulate these insights is a reflection on the quality and depth of her learning. It also demonstrates clearly how expertise develops through time, with focused and dedicated practice, with real zeal for what must be learned, and with the integration of useful and timely coaching through the process. As I’ve said in many different settings, leadership is the most complex thing humans have learned to do. And the arts of strategic influence and political navigation are among the most difficult to learn.

It has truly been a pleasure working with Kim during her first years as a division director at a major AMC. We both hope that this case study can inform both coaches and their clients about the processes, challenges, and rewards involved in becoming a leader and with helping those who are motivated to do so.

Observations from the Primary Supervisor

From the perspective of Nancy, the Department Chair

Kim and Dick have asked me to add my observations from the vantage point of the primary supervisor, as her Department Chair. The first observation is that it has been uplifting to read this. Kim has done a remarkable job of capturing the developmental stages of someone who has taken on a major leadership role, as well as the value of having as a sounding board an expert who understands those developmental stages and organizational behavior.