The first sorbent with high CO2 selectivity and poor water affinity addresses need for trace CO2 remediation in confined spaces.

Abstract

CO2 accumulation in confined spaces represents an increasing environmental and health problem. Trace CO2 capture remains an unmet challenge because human health risks can occur at 1000 parts per million (ppm), a level that challenges current generations of chemisorbents (high energy footprint and slow kinetics) and physisorbents (poor selectivity for CO2, especially versus water vapor, and/or poor hydrolytic stability). Here, dynamic breakthrough gas experiments conducted upon the ultramicroporous material SIFSIX-18-Ni-β reveal trace (1000 to 10,000 ppm) CO2 removal from humid air. We attribute the performance of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β to two factors that are usually mutually exclusive: a new type of strong CO2 binding site and hydrophobicity similar to ZIF-8. SIFSIX-18-Ni-β also offers fast sorption kinetics to enable selective capture of CO2 over both N2 (SCN) and H2O (SCW), making it prototypal for a previously unknown class of physisorbents that exhibit effective trace CO2 capture under both dry and humid conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Ever-increasing carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the atmosphere represent a global challenge for mankind (1, 2). CO2 contributes to climate change (3), but atmospheric CO2 is not only relevant to climate change but also a major health issue in confined spaces such as meeting rooms, aircraft, submarines, and spaceships, which can also suffer from elevated CO2 concentrations. Whereas the specific concentrations of CO2 that cause impairment of higher-order decision-making or long-term health risks remain uncertain (4), CO2 capture (C-capture) devices are routinely deployed in spacecraft and submarines to control CO2 concentration (5). Further, very recently, it was suggested that chronic exposure to levels as low as 1000 parts per million (ppm) can be harmful (6).

Generally, C-capture devices are the most expensive aspect of a C-capture, transport, and sequestration system because they exhibit high regeneration energy, require large equipment size, and result in equipment corrosion (7). While traditional C-capture technologies are suitable for large anthropogenic point sources where CO2 levels are high, different approaches are required for mobile sources (8). C-capture using solid sorbents offers an energy-efficient alternative to traditional processes (9), but the challenge of C-capture is exacerbated for trace CO2 removal from air [~400 ppm for direct air capture (DAC) and 1000 to 10,000 ppm for confined spaces] under variable conditions (gas composition, humidity level, and temperature). The sorbents currently used in indoor air quality (IAQ) control involve the use of activated carbon impregnated with MgO and/or CaO; C-capture occurs via chemical fixation of CO2 as metal oxides transform to metal carbonates (10). A downside of this process lies with declined performance over repeated cycles (11). Further, the fact that CO2 binding must be highly selective over atmospheric N2 (SCN ≥ 2500) and H2O (SCW ≥ 100) disqualifies all known physisorbent materials from consideration (12, 13). Chemisorbents, on the other hand, are limited by poor sorption kinetics, energy-intensive regeneration, and chemical/thermal degradation on cycling (14).

The demand for energy-efficient solutions to trace gas separations has spurred research into porous metal-organic materials (MOMs) (15), also known as porous coordination polymers (16), or metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) (17). Unlike traditional classes of porous sorbents, these materials can be designed from first principles to afford control over pore size and chemistry. Unfortunately, MOFs, such as zeolites, typically lack the high selectivity and fast kinetics required for the removal of trace CO2, in general, and from humid air, in particular (13). Many MOFs and zeolites are negatively affected by moisture (18, 19). Hybrid ultramicroporous materials (HUMs) (20), the current benchmarks for trace gas capture including C-capture (21) and acetylene capture (22), are also affected by humidity (18). The fact that the introduction of alkyl groups into pores can reduce the water affinity of MOMs (23) prompted us to study whether such an approach in HUMs might address the need for a porous material that combines (i) high affinity for CO2 and (ii) low affinity for H2O. Here, we report the first example of such a material.

RESULTS

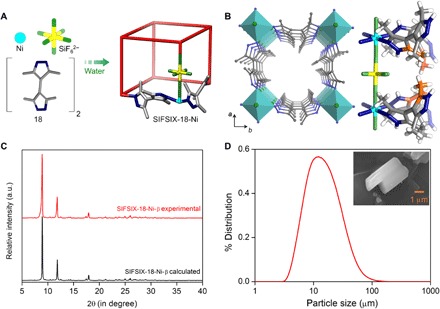

[Ni(L)2(SiF6)]n, L = 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethyl-1H,1′H-4,4′-bipyrazole, was prepared by hydrothermal reaction of L with NiSiF6∙6H2O to afford a light blue powder, SIFSIX-18-Ni-α (Fig. 1A), an analog of SIFSIX-18-Cd (24). Heating SIFSIX-18-Ni-α to 85°C under vacuum induced a phase transition to SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (Fig. 1, B and C) and a 13.4% reduction in unit cell volume (see the Supplementary Materials for full details). Both forms of SIFSIX-18-Ni are primitive cubic (pcu) nets composed of two-dimensional layers of Ni(II) nodes cross-linked by organic linkers that are pillared by inorganic anions (SiF62−). The resulting square channels are lined with inorganic anions, weakly basic nitrogen atoms, and methyl groups (Fig. 1B). After confirming bulk phase purity and crystallinity (Fig. 1C), particle size distribution analysis revealed a relatively uniform mean diameter of ca. 14 μm (Fig. 1D and fig. S6). Scanning electron microscopy revealed block-shaped morphology (Fig. 1D, inset).

Fig. 1. Structure description, synthesis, and characterization.

(A) Schematic illustration of the building blocks and pcu network topology of SIFSIX-18-Ni. (B) Left: View of the ultramicropore in SIFSIX-18-Ni-β along the crystallographic c axis (C, gray; N, blue; Si, yellow; F, green; Ni, cyan). Right: Illustration of the hydrophobic cavity (orange) decorated by methyl groups, amines, and inorganic pillars. (C) Experimental and calculated powder x-ray diffractograms of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β. (D) Particle size analysis and scanning electron microscopy image of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β crystals (inset). a.u., arbitrary units.

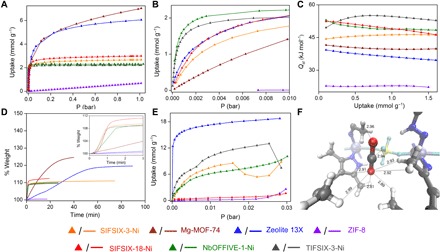

The sorption properties of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β were first examined using single-component isotherms (Fig. 2A and figs. S8 to S11). For comparative purposes, six additional physisorbent materials representing three classes of sorbents with strong potential for IAQ control were also evaluated: two MOFs [Mg-MOF-74, the benchmark MOF for C-capture (25), and ZIF-8, a hydrophobic MOF (26)], a zeolite that is known both as a desiccant and as a C-capture sorbent [Zeolite 13X (27)], and three HUMs that are known for their high CO2 selectivity versus both N2 and CH4 [NbOFFIVE-1-Ni (28), TIFSIX-3-Ni (29), and SIFSIX-3-Ni (18, 19)] (Fig. 2, A and B, and figs. S13 to S18). The pure gas isotherms at CO2 partial pressures relevant to DAC (ca. 500 ppm) and IAQ control (CO2, 0.005 to 0.01 bar) reveal that only the HUMs exhibit strong C-capture performance. At 1000 ppm, CO2 uptakes were as follows: NbOFFIVE-1-Ni and TIFSIX-3-Ni, 1.8 and 1.7 mmol g−1, respectively; SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, SIFSIX-3-Ni, and Zeolite 13X, ca. 0.8 mmol g−1; Mg-MOF-74 and ZIF-8, negligible. The HUMs were found to exhibit similar CO2 sorption performance between 0.005 and 0.01 bar with near-full loading at 0.01 bar. Mg-MOF-74 and Zeolite 13X exhibited CO2 uptakes of 0.9 (~13% loading) and 1.7 mmol g−1 (~28% loading) at 0.005 bar CO2 and 298 K, respectively. No sorbent was observed to exhibit substantial N2 uptake at 1.0 bar and 298 K (Table 1 and figs. S10 and S13 to S18).

Fig. 2. Single-component sorption, kinetic studies, and “sweet spot” for CO2 binding.

(A and B) Low-pressure CO2 isotherms at 298 K. (C) Isosteric heat of adsorption profiles for CO2. (D) Gravimetric CO2 uptake (1.0 bar) versus time at 303 K. (E) Dynamic vapor sorption (DVS) isotherms for H2O at 298 K. (F) CO2 binding sites in SIFSIX-18-Ni-β determined by ab initio periodic computation. Dashed lines indicate CO2--HUM internuclear distances from 2.81 to 2.99 Å. Color code: C, gray; H, white; O, red; N, sapphire; Si, yellow; F, cyan; Ni, light blue.

Table 1. Isosteric heat of adsorption, gas sorption, and selectivity data.

| Material |

CO2Qst (kJ mol−1)* |

CO2 uptake (298 K) (mmol g−1) |

N2 (298 K, 1 bar) mmol (g−1) |

H2O (298 K, 95% RH) (mmol g−1)† |

IAST selectivity‡ | |||||

|

500 ppm |

1000 ppm |

3000 ppm |

5000 ppm |

10,000 ppm |

SCN§ | SCW|| | ||||

| Mg-MOF-74 | 42 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.85 | ~33.33¶ | 238 | N/A |

| Zeolite 13X | 39 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.42 | 18.76 | 562 | N/A |

| SIFSIX-18-Ni-β | 52 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 0.04 | 1.64/0.96# | N/A** | 16.2‡‡ |

| SIFSIX-3-Ni | 45 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 0.16 | 8.80 | 1438 | N/A†† |

| NbOFFIVE-1-Ni | 54 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 0.15 | 10.09 | 6528 | 0.03‡‡ |

| TIFSIX-3-Ni | 49 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 0.18 | 7.46 | 8090 | N/A†† |

| ZIF-8 | 27 | ~0.0006 | <0.005 | <0.005 | 0.006 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1.44# | 3.1 | 0.08 |

*Virial fitting of CO2 sorption data collected between 0 and 10 mbar.

†Data collected on surface measurement systems vacuum DVS unless otherwise stated.

‡Selectivity for sorbents was determined by interpolation of raw isotherm data points (see the Supplementary Materials for further details).

§Selectivity based upon 500 ppm CO2 concentration.

||Selectivity based upon 500 ppm CO2 concentration/74% RH.

¶Water uptake for Mg-MOF-74 was acquired from (30).

#Water uptake based upon surface measurement systems intrinsic DVS data.

**IAST selectivity suggests partial sieving (see the Supplementary Materials).

††IAST cannot be calculated due to negative adsorption observed as a result of phase change in the presence of water.

‡‡Calculated at 74% RH and 500 ppm.

With respect to H2O sorption, Zeolite 13X (18.8 mmol g−1), TIFSIX-3-Ni (7.5 mmol g−1), NbOFFIVE-1-Ni (10.1 mmol g−1) and SIFSIX-3-Ni (8.8 mmol g−1) were found to exhibit high uptake at 95% relative humidity (RH). Conversely, ZIF-8 (2.6 mmol g−1) and SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (1.6 mmol g−1) exhibited low H2O uptake consistent with surface sorption. Under ambient pressure, SIFSIX-18-Ni-β adsorbed 0.96 mmol g−1 at 95% RH (Fig. 2E) accompanied by a phase transition to SIFSIX-18-Ni-α [in situ powder x-ray diffraction (PXRD); fig. S5], however regenerable by temperature swing. Mg-MOF-74 was not studied due to its hydrolytic instability (18, 30).

The isosteric heat of adsorption (Qst) values for CO2 are generally flat across the range of loading and decrease in line with the low pressure uptakes reported above: NbOFFIVE-1-Ni (54 kJ mol−1) > SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (52 kJ mol−1) > TIFSIX-3-Ni (50 kJ mol−1) > SIFSIX-3-Ni (45 kJ mol−1) > Mg-MOF-74 (42 kJ mol−1) > Zeolite 13X (39 kJ mol−1) > ZIF-8 (26.7 kJ mol−1) (Fig. 2C, Table 1, figs. S19 and S20, and tables S2 and S3) (29). Gravimetric CO2 adsorption at 1 bar/303 K revealed that whereas SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, NbOFFIVE-1-Ni, TIFSIX-3-Ni, and SIFSIX-3-Ni exhibit lower CO2 uptake than Mg-MOF-74 and Zeolite 13X, they offer superior kinetics, reaching 90% of their equilibrium loading within ca. 1 min of exposure versus 20 to 40 min (Fig. 2D). Under dry/wet trace CO2/N2 mixtures, the C-capture kinetics of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β even outperforms the benchmark silica chemisorbent TEPA-SBA-15 (figs. S53 and S54) (31). Selectivity determined via ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST) (32) revealed that, at 298 K, SIFSIX-18-Ni-β in effect serves as a partial sieve for SCN (figs. S9 and S45). The IAST selectivity for SCW, which was calculated at 74% RH and 500 ppm CO2, is 16.2, with higher SCW values of 54.0 and 173.1 at 0.005 and 0.01 bar CO2, respectively (table S1 and figs. S25 and S26). These SCW values are not corrected for surface sorption and are likely to be even higher. In summary, SIFSIX-18-Ni-β is, to our knowledge, the first physisorbent that combines strong C-capture performance and low water uptake.

To understand its unexpectedly strong C-capture properties, we modeled the CO2 binding site in SIFSIX-18-Ni-β by ab initio and empirical simulations. The empirically modeled structure of a 2 × 2 × 2 box of unit cells of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (fig. S57) revealed a series of CH…O interactions supplementing the expected C…F binding between the electropositive carbon atoms of CO2 and fluorine moieties of SIFSIX (Fig. 2F). The initial binding site for CO2 from ab initio periodic computation resembles that in other SIFSIX systems in that there is an interaction with a SIFSIX moiety (CCO2 – FSIFSIX = 2.94 Å; Fig. 2F). However, the binding site is otherwise distinct in that there are also electrostatic attractions between the partially negative O atoms of CO2 and partially positive methyl hydrogen atoms of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β. In addition, empirical simulations revealed a CCO2 – FSIFSIX distance of as low as 2.54 Å at 298 K. Concurrent OCO2 – HHUM interactions of 2.81, 2.89, 2.91, 2.92, 2.93, 2.96, 2.99, and 3.09 Å were also found in the optimized structure (see the Supplementary Materials for full details). This binding site more resembles the type of binding site typically found in enzymes than that of other HUMs.

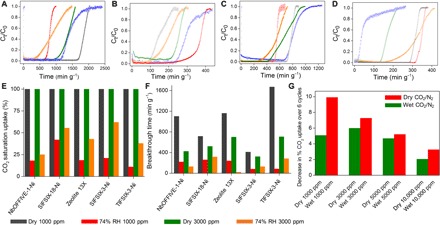

Real-time trace C-capture performance for each physisorbent was examined via fixed-bed column breakthrough experiments (Fig. 3, A to F; figs. S27 to S40; and table S4) using binary CO2/N2 mixtures that mimic indoor CO2 concentrations: 1000/3000 ppm, 298 K, dry/74% RH (4). The dry 1000 ppm CO2 saturation uptake of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β was observed to be 0.7 mmol g−1 with a breakthrough retention time of 715 min g−1 (Fig. 3A and fig. S27). TIFSIX-3-Ni offered the best dry 1000 ppm CO2 saturation uptake and breakthrough retention time of the sorbents studied (1.6 mmol g−1 and 1670 min g−1, respectively) (Fig. 3A). However, at 74% RH, SIFSIX-18-Ni-β was found to be the top performing material with CO2 saturation uptake of 0.3 mmol g−1 and a breakthrough time of ca. 260 min g−1; the performance of the other sorbents studied was degraded by >80% humidity (Fig. 3B). For the dry 3000 ppm CO2/N2 experiments, the CO2 sorption performances of TIFSIX-3-Ni and Zeolite 13X are comparable with saturation uptakes and breakthrough retention times of ca. 2.1 mmol g−1 and 700 min g−1, respectively (Fig. 3C and table S4). Under the same conditions, CO2 saturation uptakes for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (ca. 1.5 mmol g−1), NbOFFIVE-1-Ni (ca. 1.9 mmol g−1), SIFSIX-3-Ni (ca. 1.6 mmol g−1), and ZIF-8 (ca. 0.002 mmol g−1) (retention times for the first three: ca. 520, 425, and 322 min g−1, respectively) were observed. However, at 74% RH, the performance of both NbOFFIVE-1-Ni and Zeolite 13X deteriorated with CO2 saturation uptakes of only 0.5 and 0.1 mmol g−1, respectively (retention times: ca. 128 and 20 min g−1, respectively) (Fig. 3D). Under the same conditions, SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, TIFSIX-3-Ni, and SIFSIX-3-Ni stand out from Zeolite 13X and NbOFFIVE-1-Ni with CO2 saturation uptakes of 0.8, 0.8, and 0.9 mmol g−1, respectively. Notably, the CO2 retention time for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (ca. 316 min g−1) was greater than those of SIFSIX-3-Ni and TIFSIX-3-Ni (ca. 187 and 283 min g−1, respectively).

Fig. 3. Dynamic gas breakthrough and recyclability tests.

Dynamic gas breakthrough tests for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (red), NbOFFIVE-1-Ni (green), Zeolite 13X (blue), SIFSIX-3-Ni (orange), TIFSIX-3-Ni (gray), and ZIF-8 (purple) using (A) dry 1000 ppm, (B) 74% RH 1000 ppm, (C) dry 3000 ppm, and (D) 74% RH 3000 ppm CO2/N2 [v/v = 0.1/99.9% for (A) and (B) and v/v = 0.3/99.7% for (C) and (D)] gas mixtures (298 K; 1 bar; flow rate, 20 cm3 min−1). (E) Bar diagram exhibiting the relative decline in CO2 saturation uptakes (%) of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β versus other physisorbents (dry/74% RH, 1000/3000 ppm CO2/N2). (F) Bar diagram of CO2 retention times (min g−1) under dry/74% RH, 1000/3000 ppm CO2/N2. (G) Decrease in % CO2 uptakes over six consecutive adsorption-desorption cycles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (CO2/N2 dry/wet gas mixtures of the following composition: 1000, 3000, 5000, and 10,000 ppm CO2, without/with 74% RH, saturated with N2).

NbOFFIVE-1-Ni and SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, the top performing sorbents, were further subjected to 5000 ppm/99.5% and 10,000 ppm/99% CO2/N2 breakthrough experiments (figs. S39 and S40). For SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, CO2 saturation uptakes (dry/wet) were found to be 1.7/1.2 mmol g−1 at 5000 ppm (retention times, 735/532 min g−1, respectively) and 2.0/1.7 mmol g−1 at 10,000 ppm (retention times, 440/410 min g−1, respectively). For NbOFFIVE-1-Ni, the CO2 saturation uptakes were lower under dry conditions and much lower under wet conditions: 1.5/0.7 mmol g−1 at 5000 ppm (retention times, ca. 650/333 min g−1, respectively) and 1.8/1.1 mmol g−1 at 10,000 ppm (retention times, ca. 340/255 min g−1, respectively). The performance of NbOFFIVE-1-Ni at 0.01 bar (10,000 ppm) is consistent with a previous report (28). Table S4 tabulates the breakthrough results at all CO2 levels and reveals that SIFSIX-18-Ni-β is much less affected by the presence of moisture than the other C-capture sorbents at all levels from 1000 to 10,000 ppm.

The stability of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β was evaluated using an accelerated stability protocol adopted by the pharmaceutical industry (storage at 40°C and 75% RH) (33). PXRD data revealed that SIFSIX-18-Ni-β reverted to the α polymorph after 14 days, but it is regenerable (fig. S42) with negligible change in BET surface area and CO2 sorption performance (figs. S43 and S44). To further examine recyclability of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, we conducted 100 adsorption/desorption cycles in the presence of 1.0 bar CO2 at 308 K (fig. S52). Full loading was achieved in each cycle after ca. 1 min; desorption experiments were performed at 348 K to ensure regeneration. SIFSIX-18-Ni-β exhibited no loss in performance over 100 cycles under these conditions. Similar results under dry and wet (74% RH) CO2/N2 mixtures with CO2 concentrations of 1000, 3000, 5000, and 10,000 ppm (Fig. 3G and figs. S48 to S51) further validated the trace C-capture performance. The fact that effluent CO2 levels are <50 ppm across all trace C-capture conditions (table S4) qualifies SIFSIX-18-Ni-β as a sorbent suitable for IAQ needs.

DISCUSSION

Whereas the use of physisorbents for trace C-capture offers a potentially superior alternative to traditional processes (34), even the top performing physisorbents such as zeolites and MOFs lack the selectivity and/or kinetics needed for trace C-capture under dry conditions. Further, the performances of NbOFFIVE-1-Ni and Mg-MOF-74 are degraded by their strong affinity for H2O. Conversely, hydrophobic MOFs such as ZIF-8 exhibit low H2O uptake but suffer from very low CO2 uptake and/or selectivity. In essence, a Catch-22 situation exists: Pore surfaces with the requisite thermodynamics and kinetics to address trace level C-capture tend to also have binding sites that enable high water uptake (e.g., NbOFFIVE-1-Ni; figs. S21, S22, S29, and S30) (29, 35); hydrophobic pore surfaces that offer low water uptake tend to also exhibit low CO2 affinity (e.g., ZIF-8). In this context, SIFSIX-18-Ni-β represents a paradigm shift in terms of both properties and pore design. With respect to properties, SIFSIX-18-Ni-β combines unexpectedly strong affinity for CO2 along with the hydrophobicity that we anticipated from its methyl-decorated pores (36). With respect to design, the CO2 binding site presents two synergistic features: a relatively strong C···F interaction to a SIFSIX moiety and six weak C-H···O interactions from methyl groups. This “pocket” (Figs. 1B and 2F and fig. S57) for CO2 enables a binding interaction (52 kJ mol−1) that approaches that of the leading physisorbents, NbOFFIVE-1-Ni and TIFSIX-3-Ni, but offers only weak interactions with O2, N2 and notably, H2O.

The mechanism of C-capture in SIFSIX-18-Ni-β is therefore unlike other physisorbents that offer strong C-capture performance, which tend to bind CO2 through open metal sites or strong electrostatic environments or via chemical reaction with amine groups (37). Rather, the binding site in SIFSIX-18-Ni-β has enzyme-like features that result in a tight CO2 binding. A similar situation exists in [Zn2(Atz)2(ox)]n, which exploits supramolecular interactions that offer a strong interaction with CO2 (40.8 kJ mol−1) but weak interactions toward N2, H2, and Ar (38). SIFSIX-18-Ni-β teaches a further message that is also offered by nature’s predominant carbon-fixing enzyme, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCo), which must also sequester CO2 in humid environments. The key to RuBisCo’s C-capture performance is thought to lie with its small hydrophobic side chains that enable a cavity that concentrates CO2 (39). Nevertheless, despite the critical role that RuBisCo plays in the global carbon cycle, it suffers from relatively inefficient performance that would render it ineffective for industrial C-capture: low density of CO2 binding sites, competitive binding by O2, and slow kinetics (40). SIFSIX-18-Ni-β also presents a hydrophobic pocket that addresses the need for weak H2O binding, but it otherwise offers key performance advantages over RuBisCo: very high CO2/O2 selectivity (molar SCO ~ 2079 for 10,000 ppm CO2/99% O2, fig. S11; IAST SCO > 3 × 104 suggested sieving, fig. S46), fast CO2 sorption kinetics (Fig. 2D), and a relatively high density of binding sites. Further, in situ PXRD (fig. S4), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) measurement (fig. S47), and cycled kinetic adsorption experiments (Fig. 3G and fig. S52) reveal that CO2 sorption in SIFSIX-18-Ni-β is facile, as temperature swing recycling can be conducted at 348 K (figs. S23 and S41). These features mean that, unlike existing benchmark physisorbent materials, the C-capture performance of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β is retained even at high RH in 0.005 bar (0.5% CO2) and 0.01 bar (1% CO2) CO2 gas mixtures (figs. S39 and S40).

CONCLUSIONS

A crystal engineering approach to pore size (ultramicroporosity) and pore chemistry (coupling of strong electrostatic interactions from inorganic anions and hydrophobicity from methyl groups) control has resulted in a HUM, SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, with binding sites that exhibit exceptional CO2 selectivity from wet CO2/N2 gas mixtures. SIFSIX-18-Ni-β thereby offers highly effective C-capture performance under conditions that mimic C-capture from air in confined spaces and presents an energy-efficient potential solution to IAQ control. The nature of the binding site in SIFSIX-18-Ni-β is key to its performance and provides insight into how to generally improve the performance of physisorbents with respect to C-capture when CO2 is present at trace levels in humid gas mixtures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gas sorption measurements

Ultrahigh-purity gases, as received from BOC Gases [research-grade He (99.999%), CO2 (99.995%), O2 (99.999%), and N2 (99.998%)], were used for gas sorption experiments. Adsorption experiments (up to 1 bar) for different pure gases were performed using a Micromeritics 3Flex 3500 surface area and pore size analyzer. Before sorption measurements, activation of SIFSIX-18-Ni was achieved by degassing the methanol-exchanged sample on a SmartVacPrep using dynamic vacuum and heating for 4 hours (sample was heated from room temperature to 348 K with a ramp rate of 5°C). Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface areas were determined from the N2 adsorption isotherms at 77 K using the Micromeritics Microactive software except for NbOFFIVE-1-Ni and TIFSIX-3-Ni, whose BET surface areas were calculated from their 298 K CO2 adsorption isotherms. About 200 mg of activated samples was used for the measurements. Very low pressure CO2 measurements were performed using a Micromeritics 3Flex surface area and pore size analyzer at 273, 283, and 298 K. A Julabo temperature controller was used to maintain a constant temperature in the bath throughout the experiment. Bath temperatures of 273, 283, and 298 K were precisely controlled with a Julabo ME (v.2) recirculating control system containing a mixture of ethylene glycol and water. The low temperatures at 77 and 195 K were controlled using a 4-liter Dewar flask filled with liquid N2 and dry ice/acetone, respectively. O2 adsorption isotherm at 77 K was measured up to ∼146 mmHg, because the saturation vapor pressure (P0) of O2 at 77 K is 147.8 mmHg.

Breakthrough experiments

In typical breakthrough experiments, ~0.3, 0.33, and 0.24 g of preactivated SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, NbOFFIVE-1-Ni, and ZIF-8, respectively, and ~0.31 g of Zeolite 13X and TIFSIX-3-Ni were placed in quartz tubing (8 mm diameter) to form a fixed bed. First, the adsorbent bed was purged under a 25 cm3 min−1 flow of He gas at 333 K for 30 min before breakthrough experiment. Upon cooling to room temperature, the gas flow was switched to the desired gas mixture at a particular flow rate (the respective flow rates are mentioned in the figure captions and in table S4). Here, trace CO2/N2 (~1000, 3000, 5000, and 10,000 ppm)/(99.9, 99.7, 99.5, and 99%, respectively) breakthrough experiments were conducted at 298 K. The outlet composition was continuously monitored using a Hiden HPR-20 quartz inert capillary mass spectrometer until complete breakthrough was achieved. After each dry and wet breakthrough experiment, the packed column bed was regenerated at 403 K (SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, NbOFFIVE-1-Ni, ZIF-8, and TIFSIX-3-Ni) and 573 K (Zeolite 13X) with constant He flow (25 cm3 min−1) for 120 min to ensure complete sample regeneration. Experiments in the presence of 74% RH were performed by passing the gas stream through a water vapor saturator at 298 K.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank T. Curtin (University of Limerick, 07/SRC/B1160) for cooperation. Funding: M.J.Z. acknowledges the Science Foundation Ireland (awards 13/RP/B2549 and 16/IA/4624). D.M.F. and B.S. acknowledge the National Science Foundation (award no. DMR-1607989), including support from the Major Research Instrumentation Program (award no. CHE1531590). Computational resources were made available by XSEDE (grant TG-DMR090028) and by Research Computing at the University of South Florida. B.S. also acknowledges support from the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund grant (ACS PRF 56673-ND6). Author contributions: S.M. and M.J.Z. contributed to design the project. S.M. synthesized all compounds, and N.K. helped scale up. N.S., S.M. and D.G.M. collected and interpreted the experimental breakthrough data. D.O. performed crystallographic studies. S.M. and A.K. collected the gas adsorption data. S.M., and D.O. calculated IAST selectivities. S.M. performed kinetic experiments and recyclability tests with single- and multicomponent gases. D.M.F. and B.S. conducted the molecular modeling. V.G. collected the water sorption data. A.K. carried out particle size distribution analysis. D.O. and A.K. carried out electron microscopy. P.E.K. planned and H.S.S. performed organic synthesis. S.M., N.S., D.O., D.G.M., and M.J.Z. wrote the paper, and all authors contributed to revising the paper. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data materials and availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from M.J.Z. (xtal@ul.ie).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/11/eaax9171/DC1

Supplementary Materials and Methods

Supplementary Text

Fig. S1. PXRD of SIFSIX-18-Ni.

Fig. S2. Variable temperature PXRD of SIFSIX-18-Ni.

Fig. S3. Comparison of experimental PXRD profiles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-α, SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, and SIFSIX-18-Ni-γ with their calculated patterns and related polymorphs (24) (all recorded at 298 K).

Fig. S4. Comparison of experimental PXRD profiles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (activated, before dosing CO2), and SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (dosed with 1 bar CO2 at 303 K) with the calculated pattern of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Fig. S5. Comparison of experimental PXRD profiles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-α, SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, and SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (activated, before dosing H2O).

Fig. S6. Particle size distribution around the mean diameter (~13.94 μm) range of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Fig. S7. Thermogravimetric analysis profiles of SIFSIX-18-Ni.

Fig. S8. CO2 sorption isotherms for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β; inset: low pressure range until 0.01 bar.

Fig. S9. Low-temperature CO2, N2, and O2 sorption isotherms for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Fig. S10. CO2 and N2 sorption isotherms for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Fig. S11. CO2 and O2 sorption isotherms for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Fig. S12. CO2 sorption isotherms at 298 K for SIFSIX-18-Ni-α (only subjected to evacuation after MeOH washing of precursor, i.e., no heating), SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, and SIFSIX-18-Ni-γ.

Fig. S13. CO2 and N2 sorption isotherms for Mg-MOF-74.

Fig. S14. CO2 and N2 sorption isotherms for Zeolite 13X.

Fig. S15. CO2 and N2 sorption isotherms for SIFSIX-3-Ni.

Fig. S16. CO2 and N2 sorption isotherms for NbOFFIVE-1-Ni.

Fig. S17. CO2 and N2 sorption isotherms for TIFSIX-3-Ni.

Fig. S18. CO2 and N2 sorption isotherms for ZIF-8.

Fig. S19. Fitting of the isotherm data for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β to the virial equation.

Fig. S20. Fitting of the isotherm data for ZIF-8 to the virial equation.

Fig. S21. H2O sorption isotherms for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β compared with other HUMs (all recorded at 298 K).

Fig. S22. Sorption isotherms (298 K) for CO2 and H2O for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β compared with other HUMs; pressure range until 0.03 bar i.e. saturation pressure of H2O at 298 K.

Fig. S23. H2O sorption isotherms (298 K) of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β for vacuum DVS and intrinsic DVS experiments.

Fig. S24. H2O sorption isotherms of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β recorded at different temperatures by intrinsic DVS experiments.

Fig. S25. Humidity-dependent CO2/H2O selectivities (SCW) for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β at 298 K.

Fig. S26. CO2/H2O selectivities (SCW) for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β under different CO2 concentrations at 298 K.

Fig. S27. 0.1/99.9 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for SIFSIX-18-Ni-b under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S28. 0.3/99.7 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for SIFSIX-18-Ni-b under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S29. 0.1/99.9 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for NbOFFIVE-1-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S30. 0.3/99.7 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for NbOFFIVE-1-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S31. 0.1/99.9 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for Zeolite 13X under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S32. 0.3/99.7 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for Zeolite 13X under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S33. 0.1/99.9 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for SIFSIX-3-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S34. 0.3/99.7 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for SIFSIX-3-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S35. 0.1/99.9 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for TIFSIX-3-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S36. 0.3/99.7 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for TIFSIX-3-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S37. 1000 ppm CO2/N2 (v/v = 0.1/99.9%) breakthrough profiles for ZIF-8 under dry condition, flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S38. 3000 ppm CO2/N2 (v/v = 0.3/99.7%) breakthrough profiles for ZIF-8 under dry condition, flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S39. 0.5/99.5 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β and NbOFFIVE-1-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 10 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S40. 1/99 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β and NbOFFIVE-1-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 10 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S41. Temperature-programmed desorption plot of DAC of CO2 experiment for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Fig. S42. PXRD profiles for SIFSIX-18-Ni before and after accelerated stability test.

Fig. S43. BET surface areas as obtained from 77 K N2 adsorption isotherms for SIFSIX-18-Ni and other adsorbents, after accelerated stability test.

Fig. S44. CO2 adsorption isotherms (298 K) for SIFSIX-18-Ni after accelerated stability test.

Fig. S45. IAST selectivity comparison for benchmark physisorbents at CO2 (500 ppm): N2 binary mixture; results for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β not included as partial sieving effect is observed.

Fig. S46. IAST selectivities found in SIFSIX-18-Ni-β for CO2/O2 binary mixtures with varying CO2 concentrations.

Fig. S47. FTIR spectra of SIFSIX-18-Ni: as-synthesized, activated (β), after CO2 sorption, after H2O sorption, and after 1-hour CO2 dosing at 1 bar.

Fig. S48. 0.1/99.9 (v/v) CO2/N2 adsorption-desorption recyclability over 6 consecutive cycles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β under dry and 74% RH conditions.

Fig. S49. 0.3/99.7 (v/v) CO2/N2 adsorption-desorption recyclability over 6 consecutive cycles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β under dry and 74% RH conditions.

Fig. S50. 0.5/99.5 (v/v) CO2/N2 adsorption-desorption recyclability over 6 consecutive cycles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β under dry and 74% RH conditions.

Fig. S51. 1/99 (v/v) CO2/N2 adsorption-desorption recyclability over 6 consecutive cycles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β under dry and 74% RH conditions.

Fig. S52. CO2 adsorption-desorption recyclability over 100 cycles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (1.0 bar CO2; desorption at 348 K): for each cycle, 60 min of isothermal (303 K) gravimetric CO2 uptake recorded on the activated sample.

Fig. S53. Comparison of gravimetric C-capture kinetics in SIFSIX-18-Ni-β and TEPA-SBA-15 under dry conditions.

Fig. S54. Comparison of gravimetric C-capture kinetics in SIFSIX-18-Ni-β and TEPA-SBA-15 under wet conditions.

Fig. S55. Diffractograms for the Le Bail refinement of SIFSIX-18-Ni-α.

Fig. S56. Diffractograms for the Rietveld refinement of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Fig. S57. Equilibrated structure of CO2 molecules residing in the cavity of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β corresponding to a loading of 2 CO2 per formula unit.

Fig. S58. Scheme of the coupled gas mixing system, TGA-based gas uptake analysis, and breakthrough separation analysis unit.

Table S1. Calculated SCW at 74% RH.

Table S2. Fitting parameters for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Table S3. Fitting parameters for ZIF-8.

Table S4. Dynamic breakthrough experiment details of CO2/N2 at 298 K and 1 bar.

Table S5. Crystallographic data for SIFSIX-18-Ni.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.The NOAA Annual Greenhouse Gas Index (AGGI) (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2017); https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/aggi/aggi.html.

- 2.International Energy Agency, Global Energy & CO2 Status Report (International Energy Agency, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacDowell N., Fennell P. S., Shah N., Maitland G. C., The role of CO2 capture and utilization in mitigating climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 243 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Research Council, The Airliner Cabin Environment and the Health of Passengers and Crew (The National Academies Press, 2002), p. 344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.A. Stankovic, D. Alexander, C. M. Oman, J. Schneiderman, A Review of Cognitive and Behavioral Effects of Increased Carbon Dioxide Exposure in Humans 2016–2017 (NASA/TM-2016-219277, NASA, 2016).

- 6.Jacobson T. A., Kler J. S., Hernke M. T., Braun R. K., Meyer K. C., Funk W. E., Direct human health risks of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide. Nat. Sustain. 2, 691–701 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boot-Handford M. E., Abanades J. C., Anthony E. J., Blunt M. J., Brandani S., Mac Dowell N., Fernández J. R., Ferrari M. C., Gross R., Hallett J. P., Haszeldine R. S., Heptonstall P., Lyngfelt A., Makuch Z., Mangano E., Porter R. T. J., Pourkashanian M., Rochelle G. T., Shah N., Yao J. G., Fennell P. S., Carbon capture and storage update. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 130–189 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith P., Davis S. J., Creutzig F., Fuss S., Minx J., Gabrielle B., Kato E., Jackson R. B., Cowie A., Kriegler E., van Vuuren D. P., Rogelj J., Ciais P., Milne J., Canadell J. G., McCollum D., Peters G., Andrew R., Krey V., Shrestha G., Friedlingstein P., Gasser T., Grübler A., Heidug W. K., Jonas M., Jones C. D., Kraxner F., Littleton E., Lowe J., Roberto Moreira J., Nakicenovic N., Obersteiner M., Patwardhan A., Rogner M., Rubin E., Sharifi A., Torvanger A., Yamagata Y., Edmonds J., Yongsung C., Biophysical and economic limits to negative CO2 emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 42–50 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 9.DʼAlessandro D. M., Smit B., Long J. R., Carbon dioxide capture: Prospects for new materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 6058–6082 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu S.-C., Shiue A., Chang S.-M., Chang Y.-T., Tseng C.-H., Mao C.-C., Hsieh A., Chan A., Removal of carbon dioxide in the indoor environment with sorption-type air filters. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 12, 330–334 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blamey J., Anthony E. J., Wang J., Fennell P. S., The calcium looping cycle for large-scale CO2 capture. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 36, 260–279 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanz-Pérez E. S., Murdock C. R., Didas S. A., Jones C. W., Direct capture of CO2 from ambient air. Chem. Rev. 116, 11840–11876 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oschatz M., Antonietti M., A search for selectivity to enable CO2 capture with porous adsorbents. Energ. Environ. Sci. 11, 57–70 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heydari-Gorji A., Sayari A., Thermal, oxidative, and CO2-induced degradation of supported Polyethylenimine Adsorbents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51, 6887–6894 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry Iv J. J., Perman J. A., Zaworotko M. J., Design and synthesis of metal–organic frameworks using metal–organic polyhedra as supermolecular building blocks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1400–1417 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitaura R., Seki K., Akiyama G., Kitagawa S., Porous coordination-polymer crystals with gated channels specific for supercritical gases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 428–431 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.M. Schroeder, Functional Metal–Organic Frameworks: Gas Storage, Separation and Catalysis (Springer-Verlag, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madden D. G., Scott H. S., Kumar A., Chen K.-J., Sanii R., Bajpai A., Lusi M., Curtin T., Perry J. J., Zaworotko M. J., Flue-gas and direct-air capture of CO2 by porous metal-organic materials. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 375, 20160025 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar A., Direct air capture of CO2 by physisorbent materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 14372–14377 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott H. S., Bajpai A., Chen K.-J., Pham T., Space B., Perry J. J., Zaworotko M. J., Novel mode of 2-fold interpenetration observed in a primitive cubic network of formula [Ni(1,2-bis(4-pyridyl)acetylene)2(Cr2O7)]n. Chem. Commun. 51, 14832–14835 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nugent P., Belmabkhout Y., Burd S. D., Cairns A. J., Luebke R., Forrest K., Pham T., Ma S., Space B., Wojtas L., Eddaoudi M., Zaworotko M. J., Porous materials with optimal adsorption thermodynamics and kinetics for CO2 separation. Nature 495, 80–84 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cui X., Chen K., Xing H., Yang Q., Krishna R., Bao Z., Wu H., Zhou W., Dong X., Han Y., Li B., Ren Q., Zaworotko M. J., Chen B., Pore chemistry and size control in hybrid porous materials for acetylene capture from ethylene. Science 353, 141–144 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen J. G., Cohen S. M., Moisture-Resistant and Superhydrophobic Metal−Organic Frameworks Obtained via Postsynthetic Modification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 4560–4561 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponomarova V. V., Komarchuk V. V., Boldog I., Krautscheid H., Domasevitch K. V., Modular construction of 3D coordination frameworks incorporating SiF62− links: Accessing the significance of [M(pyrazole)4{SiF6}] synthon. CrstEngComm 15, 8280–8287 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Britt D., Tranchemontagne D., Yaghi O. M., Metal-organic frameworks with high capacity and selectivity for harmful gases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 11623–11627 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park K. S., Ni Z., Cote A. P., Choi J. Y., Huang R., Uribe-Romo F. J., Chae H. K., OʼKeeffe M., Yaghi O. M., Exceptional chemical and thermal stability of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 10186–10191 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cavenati S., Grande C. A., Rodrigues A. E., Adsorption equilibrium of methane, CARBON dioxide, and nitrogen on zeolite 13X at high Pressures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 49, 1095–1101 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhatt P. M., Belmabkhout Y., Cadiau A., Adil K., Shekhah O., Shkurenko A., Barbour L. J., Eddaoudi M., A Fine-Tuned Fluorinated MOF Addresses the Needs for Trace CO2 Removal and Air Capture Using Physisorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 9301–9307 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar A., Hua C., Madden D. G., O’Nolan D., Chen K. J., Keane L. A. J., Perry J. J., Zaworotko M. J., Hybrid ultramicroporous materials (HUMs) with enhanced stability and trace carbon capture performance. Chem. Commun. 53, 5946–5949 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burtch N. C., Jasuja H., Walton K. S., Water stability and adsorption in metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 114, 10575–10612 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao A., Samanta A., Sarkar P., Gupta R., carbon dioxide adsorption on amine-impregnated mesoporous SBA-15 Sorbents: Experimental and kinetics study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 6480–6491 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myers A. L., Prausnitz J. M., Thermodynamics of mixed-gas adsorption. AIChE J. 11, 121–127 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- 33.K. C. Waterman, Understanding and predicting pharmaceutical product shelf-life, in Handbook of Stability Testing in Pharmaceutical Development (Springer, 2009), pp. 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitagawa S., Porous materials and the age of gas. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 10686–10687 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.OʼNolan D., Kumar A., Zaworotko M. J., Water vapor sorption in hybrid pillared square grid materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 8508–8513 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jasuja H., Burtch N. C., Huang Y., Cai Y., Walton K. S., Kinetic water stability of an isostructural family of zinc-based pillared metal–organic frameworks. Langmuir 29, 633–642 (2013).23214448 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J., Wei Y., Zhao Y., Trace carbon dioxide capture by metal–organic frameworks. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 82–93 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaidhyanathan R., Iremonger S. S., Shimizu G. K. H., Boyd P. G., Alavi S., Woo T. K., Direct observation and quantification of CO2 Binding within an amine-functionalized nanoporous solid. Science 330, 650–653 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whitney S. M., Houtz R. L., Alonso H., Advancing our understanding and capacity to engineer nature’s CO2-sequestering enzyme, Rubisco. Plant Physiol. 155, 27–35 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Lun M., Hub J. S., van der Spoel D., Andersson I., CO2 and O2 distribution in Rubisco suggests the small subunit functions as a CO2 reservoir. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 3165–3171 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Guideline, ICH Q1A (R2): Stability Testing of New Drug Substances and Drug Products (European Medicines Agency, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kruger P. E., Moubaraki B., Fallon G. D., Murray K. S., Tetranuclear copper(II) complexes incorporating short and long metal–metal separations: Synthesis, structure and magnetism. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2000, 713–718 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hutter J., Iannuzzi M., Schiffmann F., VandeVondele J., cp2k: Atomistic simulations of condensed matter systems. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 4, 15–25 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rappe A. K., Casewit C. J., Colwell K. S., Goddard W. A., Skiff W. M., UFF, a full periodic table force field for molecular mechanics and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114, 10024–10035 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mullen A. L., Pham T., Forrest K. A., Cioce C. R., McLaughlin K., Space B., A polarizable and transferable PHAST CO2 potential for materials simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 5421–5429 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/11/eaax9171/DC1

Supplementary Materials and Methods

Supplementary Text

Fig. S1. PXRD of SIFSIX-18-Ni.

Fig. S2. Variable temperature PXRD of SIFSIX-18-Ni.

Fig. S3. Comparison of experimental PXRD profiles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-α, SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, and SIFSIX-18-Ni-γ with their calculated patterns and related polymorphs (24) (all recorded at 298 K).

Fig. S4. Comparison of experimental PXRD profiles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (activated, before dosing CO2), and SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (dosed with 1 bar CO2 at 303 K) with the calculated pattern of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Fig. S5. Comparison of experimental PXRD profiles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-α, SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, and SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (activated, before dosing H2O).

Fig. S6. Particle size distribution around the mean diameter (~13.94 μm) range of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Fig. S7. Thermogravimetric analysis profiles of SIFSIX-18-Ni.

Fig. S8. CO2 sorption isotherms for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β; inset: low pressure range until 0.01 bar.

Fig. S9. Low-temperature CO2, N2, and O2 sorption isotherms for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Fig. S10. CO2 and N2 sorption isotherms for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Fig. S11. CO2 and O2 sorption isotherms for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Fig. S12. CO2 sorption isotherms at 298 K for SIFSIX-18-Ni-α (only subjected to evacuation after MeOH washing of precursor, i.e., no heating), SIFSIX-18-Ni-β, and SIFSIX-18-Ni-γ.

Fig. S13. CO2 and N2 sorption isotherms for Mg-MOF-74.

Fig. S14. CO2 and N2 sorption isotherms for Zeolite 13X.

Fig. S15. CO2 and N2 sorption isotherms for SIFSIX-3-Ni.

Fig. S16. CO2 and N2 sorption isotherms for NbOFFIVE-1-Ni.

Fig. S17. CO2 and N2 sorption isotherms for TIFSIX-3-Ni.

Fig. S18. CO2 and N2 sorption isotherms for ZIF-8.

Fig. S19. Fitting of the isotherm data for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β to the virial equation.

Fig. S20. Fitting of the isotherm data for ZIF-8 to the virial equation.

Fig. S21. H2O sorption isotherms for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β compared with other HUMs (all recorded at 298 K).

Fig. S22. Sorption isotherms (298 K) for CO2 and H2O for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β compared with other HUMs; pressure range until 0.03 bar i.e. saturation pressure of H2O at 298 K.

Fig. S23. H2O sorption isotherms (298 K) of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β for vacuum DVS and intrinsic DVS experiments.

Fig. S24. H2O sorption isotherms of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β recorded at different temperatures by intrinsic DVS experiments.

Fig. S25. Humidity-dependent CO2/H2O selectivities (SCW) for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β at 298 K.

Fig. S26. CO2/H2O selectivities (SCW) for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β under different CO2 concentrations at 298 K.

Fig. S27. 0.1/99.9 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for SIFSIX-18-Ni-b under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S28. 0.3/99.7 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for SIFSIX-18-Ni-b under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S29. 0.1/99.9 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for NbOFFIVE-1-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S30. 0.3/99.7 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for NbOFFIVE-1-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S31. 0.1/99.9 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for Zeolite 13X under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S32. 0.3/99.7 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for Zeolite 13X under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S33. 0.1/99.9 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for SIFSIX-3-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S34. 0.3/99.7 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for SIFSIX-3-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S35. 0.1/99.9 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for TIFSIX-3-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S36. 0.3/99.7 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for TIFSIX-3-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S37. 1000 ppm CO2/N2 (v/v = 0.1/99.9%) breakthrough profiles for ZIF-8 under dry condition, flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S38. 3000 ppm CO2/N2 (v/v = 0.3/99.7%) breakthrough profiles for ZIF-8 under dry condition, flow rate = 20 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S39. 0.5/99.5 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β and NbOFFIVE-1-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 10 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S40. 1/99 (v/v) CO2/N2 breakthrough profiles and CO2 effluent purities for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β and NbOFFIVE-1-Ni under dry and 74% RH conditions; flow rate = 10 cm3 min−1.

Fig. S41. Temperature-programmed desorption plot of DAC of CO2 experiment for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Fig. S42. PXRD profiles for SIFSIX-18-Ni before and after accelerated stability test.

Fig. S43. BET surface areas as obtained from 77 K N2 adsorption isotherms for SIFSIX-18-Ni and other adsorbents, after accelerated stability test.

Fig. S44. CO2 adsorption isotherms (298 K) for SIFSIX-18-Ni after accelerated stability test.

Fig. S45. IAST selectivity comparison for benchmark physisorbents at CO2 (500 ppm): N2 binary mixture; results for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β not included as partial sieving effect is observed.

Fig. S46. IAST selectivities found in SIFSIX-18-Ni-β for CO2/O2 binary mixtures with varying CO2 concentrations.

Fig. S47. FTIR spectra of SIFSIX-18-Ni: as-synthesized, activated (β), after CO2 sorption, after H2O sorption, and after 1-hour CO2 dosing at 1 bar.

Fig. S48. 0.1/99.9 (v/v) CO2/N2 adsorption-desorption recyclability over 6 consecutive cycles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β under dry and 74% RH conditions.

Fig. S49. 0.3/99.7 (v/v) CO2/N2 adsorption-desorption recyclability over 6 consecutive cycles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β under dry and 74% RH conditions.

Fig. S50. 0.5/99.5 (v/v) CO2/N2 adsorption-desorption recyclability over 6 consecutive cycles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β under dry and 74% RH conditions.

Fig. S51. 1/99 (v/v) CO2/N2 adsorption-desorption recyclability over 6 consecutive cycles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β under dry and 74% RH conditions.

Fig. S52. CO2 adsorption-desorption recyclability over 100 cycles for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β (1.0 bar CO2; desorption at 348 K): for each cycle, 60 min of isothermal (303 K) gravimetric CO2 uptake recorded on the activated sample.

Fig. S53. Comparison of gravimetric C-capture kinetics in SIFSIX-18-Ni-β and TEPA-SBA-15 under dry conditions.

Fig. S54. Comparison of gravimetric C-capture kinetics in SIFSIX-18-Ni-β and TEPA-SBA-15 under wet conditions.

Fig. S55. Diffractograms for the Le Bail refinement of SIFSIX-18-Ni-α.

Fig. S56. Diffractograms for the Rietveld refinement of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Fig. S57. Equilibrated structure of CO2 molecules residing in the cavity of SIFSIX-18-Ni-β corresponding to a loading of 2 CO2 per formula unit.

Fig. S58. Scheme of the coupled gas mixing system, TGA-based gas uptake analysis, and breakthrough separation analysis unit.

Table S1. Calculated SCW at 74% RH.

Table S2. Fitting parameters for SIFSIX-18-Ni-β.

Table S3. Fitting parameters for ZIF-8.

Table S4. Dynamic breakthrough experiment details of CO2/N2 at 298 K and 1 bar.

Table S5. Crystallographic data for SIFSIX-18-Ni.