Abstract

Adenocarcinoma in situ and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma are the pre-invasive forms of lung adenocarcinoma. The genomic and immune profiles of these lesions are poorly understood. Here we report exome and transcriptome sequencing of 98 lung adenocarcinoma precursor lesions and 99 invasive adenocarcinomas. We have identified EGFR, RBM10, BRAF, ERBB2, TP53, KRAS, MAP2K1 and MET as significantly mutated genes in the pre/minimally invasive group. Classes of genome alterations that increase in frequency during the progression to malignancy are revealed. These include mutations in TP53, arm-level copy number alterations, and HLA loss of heterozygosity. Immune infiltration is correlated with copy number alterations of chromosome arm 6p, suggesting a link between arm-level events and the tumor immune environment.

Subject terms: Cancer, Genetics

The genomic and immune landscape of pre-invasive lung adenocarcinoma is poorly understood. Here, the authors perform exome and transcriptome sequencing on precursor legions and invasive lung adenocarcinomas, identifying recurrently mutated genes in pre/minimally invasive cases, and arm level alteration events linked to immune infiltration.

Introduction

Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most common histological subtype of lung cancer, with an average 5-year survival rate of 15%1,2. In contrast, the pre-invasive stages of LUAD, such as adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA), are associated with a nearly 100% survival rate, after surgical resection3–5. AIS is defined as a ≤3 cm adenocarcinoma lacking invasion, while MIA is a ≤3 cm adenocarcinoma with ≤5 mm invasion6. Although some focused studies have identified mutations in lung cancer drivers in AIS and MIA7–10, there remains a lack of deep insight into the molecular events driving progression of these lesions to invasive LUAD. To address this gap in our knowledge of AIS/MIA pathogenesis, we undertook a systematic investigation of the genomic and immune profiles of pre/minimally invasive lung lesions. Known driver mutations are present in the lung precursors. T cell and B cell responses to the AIS/MIA samples are observed. By comparing the genomic landscapes of the pre-invasive and invasive samples, we suggest the potential molecular events underlying the invasiveness of LUAD.

Results

The landscape of somatic alterations in AIS and MIA

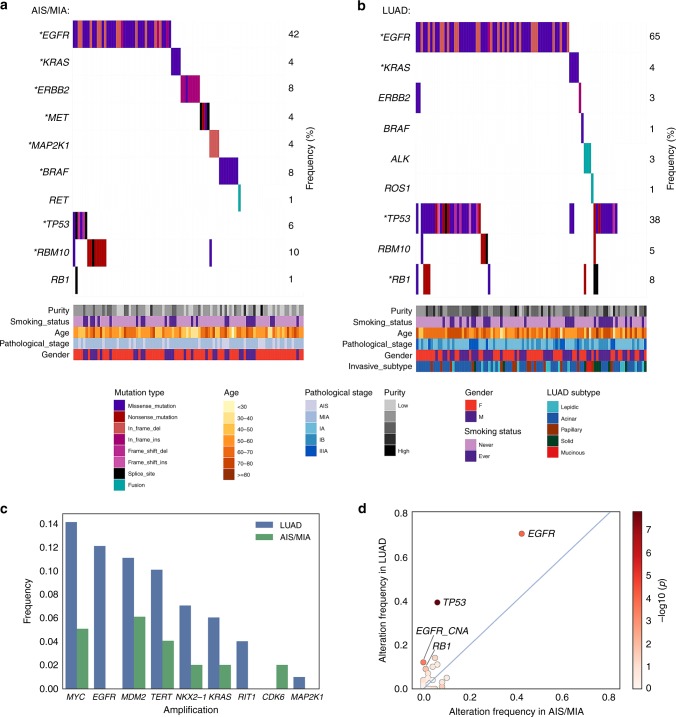

We performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) and RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) on tumor and matched adjacent normal tissue of 24 AIS, 74 MIA, and 99 invasive LUAD samples (Supplementary Table 1), obtained from patients who underwent surgery at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (FUSCC). We identified eight significantly mutated genes in AIS and MIA specimens, including EGFR, RBM10, BRAF, ERBB2, TP53, KRAS, MAP2K1, and MET, all previously reported as recurrently mutated in LUAD from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort11,12. EGFR, TP53, RB1, and KRAS were significantly mutated in the tested LUAD cases (Fig. 1a, b). Amplified regions that included MDM2, MYC, TERT, KRAS, NKX2-1, and CDK6 were observed in the AIS or MIA samples (Fig. 1c). Novel amplifications of RIT1 were identified in the FUSCC LUAD cohort (Supplementary Fig. 1). RNA-seq analysis revealed a RET fusion in an MIA sample (Fig. 1a), and ALK and ROS1 fusions in LUAD (Fig. 1b). When testing significantly mutated genes, TP53 mutations were the most enriched alteration in the invasive stage (38%) compared to pre/minimally invasive stages (6%), followed by EGFR and RB1 mutations (Fig. 1d). When testing all mutated genes in the pre/minimally invasive lung lesions, only TP53 mutations significantly increased in frequency through malignancy, after false discovery rate correction.

Fig. 1.

Somatic alterations in pre-invasive and invasive lung adenocarcinomas. a Co-mutation plots for AIS/MIA and b LUAD. Stars indicate significantly mutated genes in each group. c Lung cancer genes with focal amplification in AIS/MIA and LUAD. d Somatic alterations with higher frequencies in LUAD, compared to AIS and MIA. Color bar represents log10-transformed p value calculated from two-sided Fisher’s exact test. Source data are provided as a source data file.

The relatively simpler genomes in AIS and MIA than LUAD

Tumor mutation burden (TMB) was significantly lower in AIS and MIA, compared to stage I LUAD (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Mutational signature analysis identified aging, smoking, APOBEC, and DNA mismatch repair signatures in our cohort. The APOBEC signature was higher in MIA compared to LUAD, although the smoking signature activity did not differ among the three groups (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c). Arm-level copy-number alteration (CNA) was less common in the pre/minimally invasive stages, with a median of 5, 11, and 26 events in AIS, MIA, and LUAD, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Similarly, focal CNA increased from MIA to LUAD (Supplementary Fig. 3b). TMB, arm-level CNA and focal CNA were all correlated with advancing malignant potential, controlling for specimen purity (linear regression, p < 0.001, Methods, Supplementary Fig. 4a, b).

Molecular mechanism underlying the invasive progression

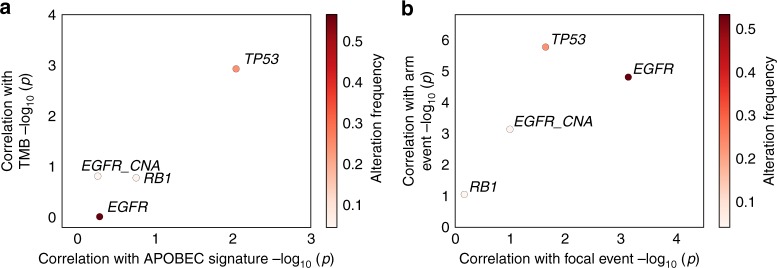

Next, we tested the association of genes with increased alteration frequency from AIS/MIA to LUAD and genomic features that distinguish LUAD from AIS/MIA (increased TMB, APOBEC signature, and focal and arm-level CNAs). Notably, TP53 mutations were strongly correlated with arm-level and TMB, but marginally correlated with focal CNA events (Fig. 2a, b). These data suggest that, in contrast to oncogenic mutations, which occurred frequently in pre/minimally invasive lung tumors, TP53 mutations were highly involved in the invasiveness during tumor development.

Fig. 2.

Correlation of somatic alterations with genomic features. TP53, EGFR, RB1 mutations and EGFR amplification in correlation with a TMB and APOBEC signature, and b arm and focal CNA. Student’s t test was used to calculate the log10-transformed p value. Samples in all stages were included to calculate the alteration frequency. Source data are provided as a source data file.

Immune characterization of AIS and MIA

In the analysis of T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire and B cell receptor (BCR) repertoire, we observed a tendency that the highest-frequency T cell clones or B cell clones in the tumors were represented as lower frequency clones in the matched normal tissues (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). However, neither T cell nor B cell clonality was increased from normal samples to AIS/MIA or LUAD (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b).

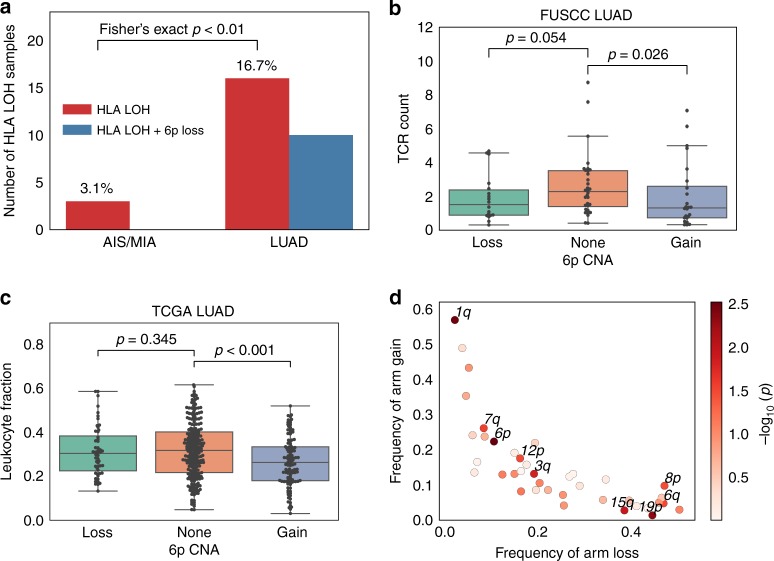

Loss of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles has been identified as a potential immune escape mechanism in lung cancers13,14 and can be observed as a subclonal event in LUADs14. In our study, we noted HLA loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in 3.1% of AIS/MIA and 16.7% of LUAD specimens (Fig. 3a). The significantly increased frequency of HLA LOH in the invasive group compared to the pre-invasive group (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.01) suggested the potential role of loss of HLA alleles during tumor development. The frequency of germline HLA homozygosity, however, was similar in all three stages (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Approximately 60% of the HLA LOH events in LUAD were related to loss of chromosome 6p. Interestingly, we found that 6p gain was significantly anti-correlated with T cell abundance (Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.038, Fig. 3b), and this trend was also observed when analyzing B cell infiltration in correlation with 6p CNA (Supplementary Fig. 7b–d). We subsequently tested the correlation of immune infiltration with large-scale chromosome alterations, using samples from the TCGA LUAD cohort. We observed the most significant correlation of leukocyte fraction15 with chromosome 6p CNA (p = 0.0030, coef. = −0.74, 95% CI: −1.23 to −0.25), followed by 1q (p = 0.0033, coef. = −0.60, 95% CI: −1 to −0.2) and 19p CNA (p = 0.0047, coef. = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.16 to 0.9), after controlling for TMB and the degree of overall aneuploidy (see Methods, Fig. 3c, d). 6p and 1q CNA showed significantly increased frequency from AIS/MIA to LUAD in the FUSCC cohort (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 7e).

Fig. 3.

Tumor immune environment in association with arm-level CNA. a Frequency of loss of HLA heterozygosity and the co-occurrence of HLA LOH with 6p loss. Significantly more HLA LOH events are found in the LUAD group compared to the AIS/MIA group. b Comparison of inferred T cell infiltration in FUSCC LUAD samples and c leukocyte infiltration15 in TCGA LUAD samples with 6p CNA loss, gain, or no change. P values are calculated from Mann–Whitney U test. Significantly decreased level of T cell or leukocyte infiltrations are found in 6p gain samples compared to 6p neutral samples. In the box plots, the upper and lower hinges represent the first and third quartile, the whiskers span the first and third quartile, and center lines represent the median. d Correlation of arm-level CNA with leukocyte infiltration for the TCGA LUAD samples. P values are calculated from multivariate linear regression, while each arm is assigned 1 if gained, −1 if lost and 0 if unchanged, and adding the aneuploidy score18 and TMB as covariates. Source data are provided as a source data file.

Discussion

We have interrogated the genomic and immune features of pre/minimally invasive lung cancers. Seventy-one percent of AIS and MIA patients carried at least one mutation in previously identified cancer genes in the RTK/RAS/RAF pathway, similar to the oncogenic driver events found in LUAD. In addition, we showed an overall high frequency of EGFR mutations (65% in LUAD), which may reflect the enrichment of never smoking patients with East Asian origin in our cohort. APOBEC-related mutations are contributors to lung cancer heterogeneity16, and might be involved in the progression from AIS/MIA to LUAD10. We found that genomic aberrations including TMB, APOBEC signature, and arm and focal CNA were increased from the pre-invasive to invasive stage. Mutations in TP53 and HLA LOH also increased in frequency in the aggressive stage .

Our work reveals TP53 as a key mediator in the invasiveness of lung cancer. Previous studies in Barrett’s esophagus suggested that TP53 occurred early in esophageal adenocarcinoma precursors followed by oncogenic amplifications17. TP53 was also frequently mutated in lung carcinoma in situ, which is the precursor form of squamous cell carcinoma18. We have shown the high frequency of oncogenic driver mutations, but low frequency of TP53 mutations in the LUAD precursors. Previous studies have suggested the functional association of TP53 mutations with invasive potential in cancers19. Our findings also demonstrate a strong association of TP53 mutations with aneuploidy, in line with recent work from TGCA20. Given previous reports of aneuploidy in association with decreased immune infiltration20,21, our data raise the possibility that copy-number changes in specific chromosomes may influence the tumor microenvironment. Our work provides new insights into the biology of lung pre-malignancy, with implications for disease monitoring and prognosis, and future therapeutic intervention.

Methods

Patient cohort and pathological review

One hundred and ninety-seven patients who underwent surgery between September 2011 and May 2016 at the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center were enrolled in this study. No patient received neoadjuvant therapy. Preoperative tests, including contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) scanning, were performed to determine the clinical stage of the disease. Fiber optic bronchoscopy was routinely performed. When necessary, CT-guided hook-wire localization was performed before surgery, to define the resection area. Tumor specimens were initially sent for intraoperative frozen section diagnosis after they were removed. The specimen was sliced at the largest diameter of the tumor for sampling. Usually two sections of each specimen were made for intraoperative diagnosis. After surgery, the tumor specimens were sent to be reviewed by two pathologists independently to confirm the clinical stage and determine the histological classification. Stage IIIA patients in this study cohort were those with initial clinical stage I diagnosis, but mediastinal lymph node metastasis was found by postsurgical pathological review. Usually 3–5 sections of each specimen were used to determine the final pathological diagnosis. Tumors were classified into AIS, MIA, and invasive adenocarcinoma, according to the LUAD classification of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society1. For invasive adenocarcinomas, the occupancy of each one of these several patterns, namely, lepidic, acinar, papillary, micropapillary, solid, and invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma, was recorded in a 5% increment, and the subtype with the highest percentage was considered as the predominant subtype. This study was approved by the Committee for Ethical Review of Research (Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center Institutional Review Board No. 090977-1). Informed consents of all patients for donating their samples to the tissue bank of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center were obtained from patients themselves or their relatives. Source data are provided as a source data file.

Whole-exome sequencing

Genomic DNA from tumors and paired adjacent normal tissues was extracted and prepared using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Exon libraries were constructed using the SureSelect XT Target Enrichment System. A total amount of 1–3 µg genomic DNA for each sample was fragmented into an average size of ~200 bp. DNA was captured using SureSelect XT reagents and protocols to generate indexed, target-enriched library amplicons. Constructed libraries were then sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform and 150 bp paired-end reads were generated.

RNA-sequencing

Total RNA from tumors and paired adjacent normal tissues was extracted and prepared using NucleoZOL (Macherey-Nagel) and NucleoSpin RNA Set for NucleoZOL (Macherey-Nagel) following the manufacturer’s instructions. A total amount of 3 µg RNA per sample was used as initial material for RNA sample preparations. Ribosomal RNA was removed using Epicenter Ribo-Zero Gold Kits (Epicenter, USA). Subsequently, the sequencing libraries were generated using the NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, Ipswich, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were then sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform and 150 bp paired-end reads were generated.

Alignment and mutation calling

Sequencing reads from the exome capture libraries were aligned to the reference human genome (hg19) using BWA-MEM22. The Picard tools (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) was used for marking PCR duplicates. The Genome Analysis Toolkit23 was used to perform base quality recalibration and local indel re-alignments. SNVs were called using MuTect and MuTect224. Indels were called using MuTect2 and Strelka v2.0.1325. Variants were filtered if called by only one tool. Oncotator v1.9.126 was used for annotating somatic mutations. Significantly mutated genes were identified using MutSig2CV27. TMB was calculated as the total number of nonsynonyous SNVs and indels per sample divided by 30, given coverage of ~30 MB. Linear regression was used to test the correlation of TMB with disease stages, while coding AIS, MIA, and LUAD as 0, 1, and 2, respectively, and adding purity as a covariate.

Mutational signature and copy-number changes

Mutational signature was called using SignatureAnalyzer28 with SNVs classified by 96 tri-nucleotide mutation. Read coverage was calculated at 50 kb bins across the genome and was corrected for GC content and mappability biases using ichorCNA v0.1.029. The copy-number analysis was performed using TitanCNA v1.17.130. GISTIC 2.0.2231 was used to identify amplification peaks and to separate arm and focal level CNA using ichorCNA generated segments. Arm-level event was defined by log2-transformed copy-number ratio >0.1 or <−0.1. Focal level events were defined by log2-transformed copy-number ratios of >1 or <−1. For EGFR and KRAS in the AIS/MIA samples, we lowered the amplification threshold to 0.8, and did not detect additional events. Purity and ploidy were calculated by the ABSOLUTE algorithm32. Linear regression was used to test the correlation of focal and arm-level CNA with disease stages, while coding AIS, MIA, and LUAD coded as 0, 1, and 2, respectively, and adding purity as a covariate.

Analysis of expression and fusion

RNA-seq reads were aligned to the reference human genome (hg19) with STAR v2.5.333. Expression values were normalized to the transcripts per million (TPM) estimates using RSEM v1.3.034. The log2-transformed TPM values were used to measure gene expression. Fusion events were called using STAR-fusion35. We focused on known lung cancer fusions (ALK, ROS1, NTRK2, RET, and MET) with read count supporting the fusion event >10, and visually inspected the BAM files to ensure accuracy.

TCR, BCR, and HLA analysis

TCR or BCR sequences were analyzed using MiXCR 2.1.1136 based on the RNA-seq data. The reads per million (RPM) value was used to normalize the total TCR or BCR count to the total reads aligned in sample. Infiltration was inferred by the RPM of TCR or BCR count. T cell or B cell diversity is inferred by the Shannon entropy score. Samples that have at least 10 clones with clone count >5 were used in the entropy test. For each sample, we calculated the entropy score based on the top 10 clones. Samples with purity <0.2 and >0.8 were excluded. Samples with possible contamination (top clones found in more than one samples) were excluded. HLA types were called with POLYSOLVER37. Loss of HLA heterozygosity was called by LOHHLA14. An event of the copy number calculated with binned B-allele frequency <0.5 and the p value (Pval_unique) of allelic imbalance <0.1 was considered as HLA LOH for AIS or MIA, and 0.05 for LUAD. For the analyses with TCGA samples, we obtained the fraction of leukocytes, TMB, aneuploidy score, and arm-level CNA from Taylor et al.20. Linear regression was used to test the correlation of arm CNA with the leukocyte fraction, while coding loss, gain, and none as −1, 1, and 0, respectively, and adding TMB and aneuploidy score as covariates.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to first acknowledge the patients for their participation in this study. All patients had signed informed consent for donating their samples to the tissue bank of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center. This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81330056, 81930073, 81572253, 31720103909, 31471239, and 31671368), the National Human Genetic Resources Sharing Service Platform (2005DKA21300), National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC1311004, 2016YFC1201701, and 2016YFC0902302), Shanghai R&D Public Service Platform Project (12DZ2295100), Shanghai Shen Kang Hospital Development Center City Hospital Emerging Cutting-edge Technology Joint Research Project (SHDC12017102), National Key Research and Development Plan (2016YFC0902302), Chinese Minister of Science and Technology grant (2016YFA0501800 and 2017YFA0505501), the National Key R&D Project of China (2016YFC0901704, 2017YFC0907502, and 2017YFF0204600), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (2017SHZDZX01), and Shanghai Municipal Health Commission Key Discipline Project (2017ZZ02025 and 2017ZZ01019). M.M. receives a grant from Stand Up to Cancer (SU2C-AACR-DT23-17) and the Pre-Cancer Genome Atlas 2.0 (1U2CCA233238-01). J.C.-Z. has a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) fellowship. J.D.C. is funded by the LUNGevity Career Development award. We thank Galen Gao and Kar-Tong Tan for their helpful suggestions.

Source Data

Author contributions

H.C. and M.M. designed the study. J.C.-Z. led the computational analyses. Y.Z. led the experiments. H. Hu, S.Y., Yawei Zhang, J.X. and Y.S. collected samples. Y.Z., S.S.F., G.H., A.M.T., A.C.B., L.W., A.R., A.D.C., and J.D.C. provided critical input for the analyses. Q.Z, X.Z. and Y.L. performed pathological review. Y.Y., D.B., Y.H., X.L., and L.S. performed quality control of data. T.Y., Y.P, D.Z., S.Z., C.C., M.K., Yang Zhang, H.L., Y.M., Z.G., X.T. and H. Han collected clinical information. Y. Zheng, J.Z., J.S., and L.S. aided in study design. J.C.-Z wrote the original draft of the manuscript. Y.Z. provided text and figures. H.C., M.M., A.R., S.S.F, A.M.T., A.D.C. and J.D.C. edited the manuscript.

Data availability

Raw data from WES and RNA-seq of AIS/MIA and LUAD have been deposited at European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA) under the accession code EGAS00001004006. Source data underlying all figures are provided as a Source Data file.

Code availability

All custom code used in the analyses is available at https://github.com/jcarrotzhang/Code-for-preinvasive.

Competing interests

M.M. is the scientific advisory board chair of OrigiMed; an inventor of a patent licensed to LabCorp for EGFR mutation diagnosis; and receives research funding from Bayer. M.M. and A.M.T. receive research funding from Ono Pharmaceutical.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Haiquan Chen, Jian Carrot-Zhang, Matthew Meyerson.

These authors contributed equally: Haiquan Chen, Jian Carrot-Zhang, Yue Zhao.

Contributor Information

Haiquan Chen, Email: hqchen1@yahoo.com.

Jian Carrot-Zhang, Email: zhangj@broadinstitute.org.

Matthew Meyerson, Email: matthew_meyerson@dfci.harvard.edu.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-13460-3.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, et al. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016;66:115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yim J, et al. Histologic features are important prognostic indicators in early stage lung adenocarcinomas. Mod. Pathol. 2007;20:233–241. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borczuk AC, et al. Invasive size is an independent predictor of survival in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2009;33:462–469. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318190157c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maeshima AM, et al. Histological scoring for small lung adenocarcinomas 2 cm or less in diameter: a reliable prognostic indicator. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010;5:333–339. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c8cb95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Travis WD, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/American thoracic society/European respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011;6:244–285. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy SJ, et al. Genomic rearrangements define lineage relationships between adjacent lepidic and invasive components in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3157–3167. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izumchenko E, et al. Targeted sequencing reveals clonal genetic changes in the progression of early lung neoplasms and paired circulating DNA. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8258. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi Y, et al. Genetic features of pulmonary adenocarcinoma presenting with ground-glass nodules: the differences between nodules with and without growth. Ann. Oncol. 2015;26:156–161. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vinayanuwattikun C, et al. Elucidating genomic characteristics of lung cancer progression from in situ to invasive adenocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:31628. doi: 10.1038/srep31628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell JD, et al. Distinct patterns of somatic genome alterations in lung adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:607–616. doi: 10.1038/ng.3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489:519–525. doi: 10.1038/nature11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGranahan N, et al. Allele-specific HLA loss and immune escape in lung cancer evolution. Cell. 2017;171:1259–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorsson V, et al. The immune landscape of cancer. Immunity. 2018;48:812–830. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Bruin EC, et al. Spatial and temporal diversity in genomic instability processes defines lung cancer evolution. Science. 2014;346:251–256. doi: 10.1126/science.1253462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stachler MD, et al. Paired exome analysis of Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1047–1055. doi: 10.1038/ng.3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teixeira VH, et al. Deciphering the genomic, epigenomic, and transcriptomic landscapes of pre-invasive lung cancer lesions. Nat. Med. 2019;25:517–525. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0323-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goh AM, et al. The role of mutant p53 in human cancer. J. Pathol. 2011;223:116–126. doi: 10.1002/path.2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor AM, et al. Genomic and functional approaches to understanding cancer aneuploidy. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:676–689. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davoli T, et al. Tumor aneuploidy correlates with markers of immune evasion and with reduced response to immunotherapy. Science. 2017;355:eaaf8399. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997 (2013).

- 23.DePristo MA, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cibulskis K, et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saunders CT, et al. Bioinformatics. 2012. Strelka: accurate somatic small-variant calling from sequenced tumor-normal sample pairs; pp. 1811–1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramos AH, et al. Oncotator: cancer variant annotation tool. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:E2423–E2429. doi: 10.1002/humu.22771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawrence MS, et al. Discovery and saturation analysis of cancer genes across 21 tumour types. Nature. 2014;505:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature12912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim J, et al. Somatic ERCC2 mutations are associated with a distinct genomic signature in urothelial tumors. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:600–606. doi: 10.1038/ng.3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adalsteinsson VA, et al. Scalable whole-exome sequencing of cell-free DNA reveals high concordance with metastatic tuomrs. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1324. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00965-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ha G, et al. TITAN: inference of copy number architectures in clonal cell populations from tumor whole-genome sequence data. Genome Res. 2014;24:1881–1893. doi: 10.1101/gr.180281.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mermel CH, et al. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R41. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carter SL, et al. Absolute quantification of somatic DNA alterations in human cancer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:413–421. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brian, J. H. et al. STAR-Fusion: fast and accurate fusion transcript detection from RNA-seq. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/03/24/120295 (2017).

- 36.Bolotin DA, et al. MiXCR: software for comprehensive adaptive immunity profiling. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:380–381. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shukla SA, et al. Comprehensive analysis of cancer-associated somatic mutations in class I HLA genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:1152–1158. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data from WES and RNA-seq of AIS/MIA and LUAD have been deposited at European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA) under the accession code EGAS00001004006. Source data underlying all figures are provided as a Source Data file.

All custom code used in the analyses is available at https://github.com/jcarrotzhang/Code-for-preinvasive.