Abstract

Our study demonstrated for the first time that bacterial extracellular DNA (eDNA) can change the thermal behavior of specific human plasma proteins, leading to an elevation of the heat-resistant protein fraction, as well as to de novo acquisition of heat-resistance. In fact, the majority of these proteins were not known to be heat-resistant nor do they possess any prion-like domain. Proteins found to become heat-resistant following DNA exposure were named “Tetz-proteins”. Interestingly, plasma proteins that become heat-resistant following treatment with bacterial eDNA are known to be associated with cancer. In pancreatic cancer, the proportion of proteins exhibiting eDNA-induced changes in thermal behavior was found to be particularly elevated. Therefore, we analyzed the heat-resistant proteome in the plasma of healthy subjects and in patients with pancreatic cancer and found that exposure to bacterial eDNA made the proteome of healthy subjects more similar to that of cancer patients. These findings open a discussion on the possible novel role of eDNA in disease development following its interaction with specific proteins, including those involved in multifactorial diseases such as cancer.

Subject terms: Cancer, Pathogens

Introduction

The role of microbiota is being revisited due to its emerging role in pathologies that were previously considered non-microbial1,2. For instance, bacteriophages have been recently found to be associated with the development of specific human diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease and type 1 diabetes3–5. Moreover, particular attention has been paid to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), mainly represented by components of microbial biofilms, including those of the gut microbiota6. One example is bacterial extracellular DNA (eDNA). Bacteria produce large amounts of eDNA that plays a multifunctional role in microbial biofilms, as a structural component, a nutrient during starvation, a promoter of colony spreading, and a pool for horizontal gene transfer7–9. eDNA is also known to affect bacterial protein modification in biofilm matrix, as exemplified by its role in the conversion of bacterial water-soluble proteins into extracellular insoluble β-sheet-rich amyloid structures, such as self-propagation and resistance to proteases and heat10–12. Heat resistance is a hallmark of prion proteins, although its biological significance is not clear. Notably, heat resistance is not an exclusive property of prion proteins or proteins implicated in heat-shock events, but can also be due to the occurrence of specific mutations in mammalian proteins that are normally not thermo-resistant, which makes this phenomenon even more puzzling13,14.

The properties of bacterial eDNA have been poorly investigated, except for its actions in the context of microbial biofilms. On the other hand, the chances that the eDNA secreted from microbial communities interacts with human proteins are relatively high. For example, eDNA released during biofilm spreading or lytic bacteriophage infection can enter the systemic circulation by different pathways, also facilitated by the altered intestinal permeability that accompanies the increased absorption of PAMPs15–17. Increasing evidence shows that impaired gut barrier dysfunction is an important determinant for the increase in circulating bacterial DNA that is associated with different diseases. Indeed, increased levels of both bacterial eDNA and human cfDNA characterize various pathological human conditions including cancer, stroke, traumas, autoimmune disorders, and sepsis18–21.

Another way by which PAMPs can enter biological fluids is their release from bacteria localized within the “internal environment” such as brain or placenta22–25. Moreover, DNA can be released into eukaryotic cells from obligate and facultative intracellular bacteria26,27.

Thus, despite the fact that interactions between bacterial eDNA and humans are very likely to occur, the effects of bacterial eDNA within body fluids are poorly studied, except for the CpG motif-induced activation of proinflammatory reactions through Toll-like receptor 928. In this study, we evaluated a novel effect of bacterial eDNA on blood plasma proteins, which resulted in the alteration of the heat resistance of these proteins.

Results

eDNA-induced alteration of protein heat resistance in the plasma of healthy controls

We first studied the effects of DNA on the thermal behavior of proteins from the plasma of healthy individuals. Most proteins were aggregated after boiling, and the supernatant contained heat-resistant fractions of over 100 proteins. The identified heat-resistant proteins had a molecular weight ranging between 8 kDa and 263 kDa. Treatment with bacterial and human buffy coat DNA altered the composition of the heat-resistant protein fraction. We first verified which plasma proteins, among those that were heat-resistant before treatment with DNA, exhibited an increased level following DNA exposure in at least one healthy control (Table 1).

Table 1.

Heat-resistant proteins of healthy controls whose amount increased following treatment with different DNAs.

| N | Accession No UniProt | Uniprot Accession | Protein name |

|---|---|---|---|

| eDNA of P. aeruginosa | |||

| 1 | P02768 | ALBU_HUMAN | Serum albumin |

| 2 | P02751 | FINC_HUMAN | Fibronectin |

| 3 | B4E1Z4 | B4E1Z4_HUMA | cDNA FLJ55673, highly similar to Complement factor B |

| 4 | P02774 | VTDB_HUMAN | Vitamin D-binding protein |

| 5 | P01859 | IGHG2_HUMAN | Immunoglobulin heavy constant gamma 2 |

| 6 | P00747 | PLMN_HUMAN | Plasminogen |

| 7 | Q14624 | ITIH4_HUMAN | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4 |

| 8 | Q5T987 | ITIH2_HUMAN | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H2 |

| 9 | P04114 | APOB_HUMAN | Apolipoprotein B-100 |

| 10 | O14791 | APOL1_HUMAN | Apolipoprotein L1 |

| 11 | P19652 | A1AG2_HUMAN | Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 2 |

| 12 | P20851 | C4BPB_HUMAN | C4b-binding protein beta chain |

| 13 | P01857 | IGHG1_HUMAN | Immunoglobulin heavy constant gamma 1 |

| eDNA of S.aureus | |||

| 1 | P02652 | APOA2_HUMAN | Apolipoprotein A-II |

| eDNA of S.mitis | |||

| 1 | P02652 | APOA2_HUMAN | Apolipoprotein A-II |

| eDNA of E.coli | |||

| 1 | P19652 | A1AG2_HUMAN | Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 2 |

| 2 | P04114 | APOB_HUMAN | Apolipoprotein B-100 |

| 3 | P20851 | C4BPB_HUMAN | C4b-binding protein beta chain |

*Significant fold change in the level of heat-resistant proteins between normal plasma and plasma treated with eDNA for the proteins with spectrum counts <200 and over 30% increase for the proteins with spectrum counts >200*.

We next measured the increase in heat-resistant protein fractions following the treatment of plasma with bacterial eDNA. The highest increase in heat-resistant fractions of different unrelated proteins was registered after incubation with the eDNA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Interestingly, eDNA from different bacteria produced distinct effects. Indeed, the exposure to eDNA from the gram-positive bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus mitis resulted in a selective increase in heat-resistant APOA2, which was not observed after treatment with eDNA from gram-negative bacteria. Under the same conditions, E. coli eDNA increased the heat-resistant fractions of A1AG2, APOB, and C4BP; however, the latter heat-resistant fractions were also increased after exposure to P. aeruginosa eDNA.

Intriguingly, specific proteins that did not exhibit a heat-resistant fraction in untreated plasma samples became heat-resistant following eDNA exposure. Table 2 lists the proteins that displayed such a behavior in at least one of the plasma samples.

Table 2.

Proteins that became heat-resistant following eDNA treatment but had no heat resistant fractions before.

| N | Accession No UniProt | Uniprot Accession | Protein name |

|---|---|---|---|

| eDNA of P.aeruginosa | |||

| 1 | P69905 | HBA_HUMAN | Hemoglobin subunit alpha |

| 2 | Q03591 | FHR1_HUMAN | Complement factor H-related protein 1 |

| 3 | P01031 | CO5_HUMAN | Complement C5 |

| 4 | A0M8Q6 | IGLC7_HUMAN | Immunoglobulin lambda constant 7 |

| 5 | O43866 | CD5L_HUMAN | CD5 antigen-like |

| 6 | P49908 | SEPP1_HUMAN | Selenoprotein P |

| 7 | P0DOY3 | IGLC3_HUMAN | Immunoglobulin lambda constant 3 |

| 8 | P63241 | IF5A1_HUMAN | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A-1 |

| 9 | P04264 | K2C1_HUMAN | Cluster of Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 1 |

| 10 | P35527 | K1C9_HUMAN | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 9 |

| 11 | P13645 | K1C10_HUMAN | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 10 |

| 12 | A0A075B6S5 | KV127_HUMAN | Immunoglobulin kappa variable 1–27 |

| eDNA of E.coli | |||

| 1 | Q9P2D1 | CHD7_HUMAN | Chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein 7 |

| 2 | Q9UGM5 | FETUB_HUMAN | Fetuin-B |

| 3 | P01857 | IGHG1_HUMAN | Immunoglobulin heavy constant gamma 1 |

| 4 | P01861 | IGHG4_HUMAN | Immunoglobulin heavy constant gamma 4 |

| 5 | P01718 | IGLV3–27 | Immunoglobulin lambda variable 3–27 |

| 6 | P20151 | KLK2 | Kallikrein-2 |

| 7 | Q8TBK2 | SETD6_HUMAN | N-lysine methyltransferase SETD6 |

| 8 | P18583 | SON_HUMAN | Protein SON |

| 9 | O95980 | RECK_HUMAN | Reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs |

| 10 | P02787 | TRFE_HUMAN | Serotransferrin |

| 11 | P49908 | SEPP1_HUMAN | Selenoprotein P |

| 12 | P0DOY3 | IGLC3_HUMAN | Immunoglobulin lambda constant 3 |

| 13 | P63241 | IF5A1_HUMAN | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A-1 |

| 14 | P13645 | K1C10_HUMAN | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 10 |

| Human DNA | |||

| 1 | P04264 | K2C1_HUMAN | Cluster of Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 1 |

| 2 | P35527 | K1C9_HUMAN | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 9 |

| 3 | P13645 | K1C10_HUMAN | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 10 |

These findings clearly demonstrated that human DNA and eDNA from different bacteria had a distinct influence on the generation of heat-resistant protein fractions. Notably, we did not detect any proteins with decreased heat-resistance following the exposure to eDNA.

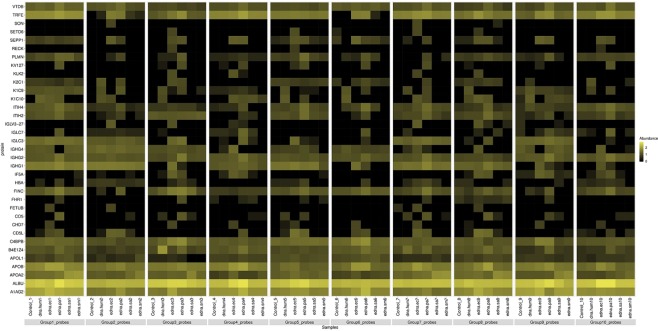

To further analyze the correlation between DNA exposure and acquisition of heat resistance, we constructed a heat map summarizing the impact of different DNAs on the thermal behavior of proteins (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Heatmap of proteins of normal plasma samples that altered their heat resistant characteristics following the treatment with different DNA. The heat map represents the relative effects of DNA from different sources on the proportion of heat-resistant proteins in normal plasma. The colour intensity is a function of protein spectrum counts, with bright yellow and black indicating maximal counts and lack of detection, respectively.

Plasma exposure to the eDNA of P. aeruginosa resulted in the formation of 12 heat-resistant proteins. Notably, only a subset of these proteins, namely K1C10, SEPP1, IGLC3, and IF5A1, also acquired heat resistance after treatment with the DNA of another gram-negative bacteria, E. coli. The latter, in turn, changed the heat resistance profile of distinct proteins in the same plasma samples.

Whereas bacterial eDNA induced heat resistance of a broad spectrum of unrelated proteins, plasma exposure to human DNA only affected the thermal behavior of a specific group of proteins, i.e., cytoskeletal keratins.

Since prion domains may be responsible for protein heat resistance, we next employed the prion-prediction PLAAC algorithm to verify the presence of PrDs in proteins exhibiting changes in thermal behavior following DNA treatment.

PrDs were only found in CHD7 and K1C10, which became heat-resistant following the exposure to E. coli eDNA, and keratins (K2C1, K1C9, K1C10), which acquired heat resistance upon treatment with both P. aeruginosa eDNA and human DNA (Table 3). Notably, the above keratins were the only proteins undergoing thermal behavior alterations following exposure to human DNA.

Table 3.

Log-likelihood ratio (LLR) score for PrD predictions in plasma proteins that became heat-resistant following DNA treatment.

| Protein | LLR Score |

|---|---|

| CHD7 | 29.081 |

| K2C1 | 21.301 |

| K1C9 | 22.663 |

| K1C10 | 21.453 |

We next analyzed the association between DNA-induced changes in protein thermal behavior and human diseases. Surprisingly, the majority of these proteins were previously found to be associated with cancer progression, and some of them are used as a tumor markers (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association between proteins exhibiting DNA-induced changes in thermal behavior and human diseases

| Disease | Proteins | References |

|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic cancer |

• Serotransferrin • Complement factor H-related protein • Plasma protease C1 inhibitor • Fibronectin • Immunoglobulin lambda constant 7 • C4b-binding protein alpha chain • Selenoprotein P |

45,46,63–71 |

| Colorectal cancer |

APOB SETD6 Reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs (RECK) |

72–74 |

| Ovarian cancer |

Hemoglobin-α Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A-1 Fibronectin Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4 fragment |

75–78 |

| Breast cancer | Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4 fragment | 78 |

| Lung Cancer |

ITIH4 Complement Factor H Plasma protease C1 inhibitor Immunoglobulin lambda constant 7 CD5L |

51,79–82 |

| hairy cell leukemia. | Immunoglobulin kappa variable 1–27 | 83 |

| melanoma |

CD5 antigen-like Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 9 |

84,85 |

| Prostatic cancer |

Selenoprotein P kallikrein 2 apolipoprotein A-II |

47,86–89 |

| Bladder cancer |

SETD6 Complement factor H-related protein |

90,91 |

| Thalassemia | HBA | 92 |

Intriguingly, some of these cancer-related proteins are also known to be associated with other multifactorial diseases. For example, ITIH4 is associated with schizophrenia and CHD7 is implicated in autism29–31.

Comparison of heat-resistant proteome profile in normal, DNA-treated, and pancreatic cancer plasma

We then examined the changes in protein thermal behavior induced by DNA in normal plasma and compared the resulting pattern with the heat-resistant proteome of patients with pancreatic cancer (Table 5).

Table 5.

Characteristics of subjects and plasma samples.

| Probe | Gender | Age | Tumour Stage | Tumour site | Tumour type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control 1 | F | 64 | NA | NA | NA |

| Control 2 | F | 55 | NA | NA | NA |

| Control 3 | M | 57 | NA | NA | NA |

| Control 4 | M | 62 | NA | NA | NA |

| Control 5 | M | 58 | NA | NA | NA |

| Control 6 | F | 61 | NA | NA | NA |

| Control 7 | F | 66 | NA | NA | NA |

| Control 8 | M | 66 | NA | NA | NA |

| Control 9 | M | 63 | NA | NA | NA |

| Control 10 | F | 60 | NA | NA | NA |

| Pancreatic cancer 1 | F | 63 | T3N1M1 | Head | Adenocarcinoma |

| Pancreatic cancer 2 | M | 57 | T3N1M1 | Head | Adenocarcinoma |

| Pancreatic cancer 3 | F | 56 | T3N1M1 | Head | Adenocarcinoma |

| Pancreatic cancer 4 | F | 69 | T3N1M1 | Head | Adenocarcinoma |

| Pancreatic cancer 5 | M | 61 | T3N1M1 | Head | Adenocarcinoma |

| Pancreatic cancer 6 | M | 52 | T3N1M1 | Head | Adenocarcinoma |

| Pancreatic cancer 7 | F | 59 | T2N1M1 | Head | Adenocarcinoma |

| Pancreatic cancer 8 | M | 72 | T3N1M1 | Head | Adenocarcinoma |

| Pancreatic cancer 9 | F | 64 | T2N1M1 | Head | Adenocarcinoma |

| Pancreatic cancer 10 | F | 71 | T3N1M1 | Head | Adenocarcinoma |

After boiling, the plasma samples of patients with pancreatic cancer were characterized for the presence of heat-resistant proteins. The majority of these proteins were the same that became heat-resistant in normal plasma exposed to DNA treatment. This suggested that DNA exposure was responsible for cancer-related alterations in the thermal behavior of specific proteins.

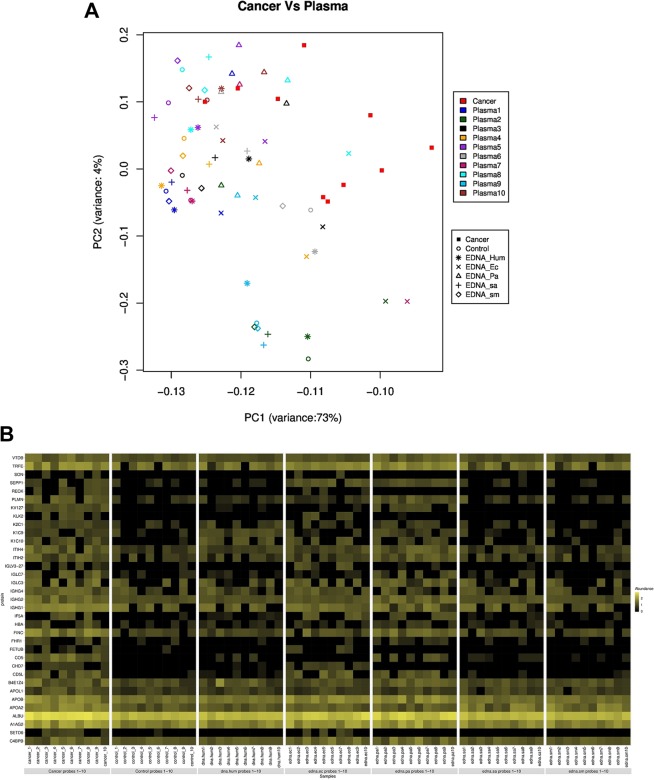

To further explore the relationship between the heat-resistant proteome of patients with pancreatic cancer and the proteome changes induced by DNA in the plasma of healthy individuals, we analyzed the scaled spectral counts of the identified heat-resistant proteins in both groups by principal component analysis (PCA) (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis (PCA) and heat map of proteome data. (A) Principal component analysis reflecting the similarities between the heat-resistant proteome of pancreatic cancer plasma and that of plasma from healthy controls following treatment with different DNAs (eby LC/MS). The strongest similarity trend between the plasma of cancer patients and that of healthy subjects after exposure to the eDNA of P. aeruginosa are shown. (B) Heat map showing the mean spectrum counts of heat-resistant proteins in normal plasma samples following DNA treatment, and in the plasma of patients with pancreatic cancer. Black colour and yellow colours represent low and high spectral counts, respectively.

The PCA projection demonstrated that the exposure to bacterial DNA (especially the eDNA of P. aeruginosa), induced, in the proteome of normal plasma, changes in thermal behavior.

A heat map based on the highest spectral counts relative to heat-resistant proteins confirmed that treatment of normal plasma with eDNA of P. aeruginosa induced a heat-resistant proteome with a higher degree of similarity to that of plasma from cancer patients, compared to that of untreated plasma (Fig. 2B).

Discussion

This study is the first to demonstrate that bacterial eDNA alters the thermal behavior of specific proteins in human plasma, leading to an increase in the heat-resistant fraction, as well as to the acquisition of heat resistance by proteins that did not exhibit such property prior to DNA exposure.

We discovered that bacterial eDNA or human DNA led to the appearance of different heat-resistant proteins, depending on the DNA source.

Furthermore, we identified a differential effect of eDNA from various gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria on the thermal behavior of plasma proteins. In fact, we surprisingly found that eDNA from different bacteria interacted with distinct plasma proteins (Table 1).

Notably, among the 35 identified proteins with increased heat-resistance following DNA exposure, according to literature data and BindUP tool, only 3 have been previously reported to be able to bind nucleic acids, namely, fibronectin, chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein 7, and SON32–34.

Heat resistance was previously described only for complement factor H and fibronectin, whereas the other proteins found to contain heat-resistant fragments in this study were not known to possess this property35–37.

Previous studies have shown that one possible mechanism responsible for the acquisition of heat resistance is the formation of β-structures, which confer increased stability to chemical and physical agents38–42.

Within this framework, we studied the presence of PrDs in proteins that were found to acquire heat resistance upon DNA exposure and predicted the presence of PrDs only in cytoskeletal and microfibrillar keratins I and II, and in chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein 743. These proteins exhibited a high likelihood ratio (LLR between 21 to 29), and therefore were highly probable to display a prion-like behavior, since the lowest LLR value reported for a known prion-forming protein of budding yeast is ~21.044.

Interestingly, PrD-containing K2C1, K1C9, and K1C10 were the only proteins that were found to acquire heat resistance following treatment with human DNA. In addition, the eDNA from P. aeruginosa and E. coli induced heat resistance in these PrDs-containing proteins.

The majority of proteins undergoing eDNA-dependent changes in heat resistance identified in the current study did not contain PrDs. This suggested that eDNA caused a PrD-independent induction of heat resistance in these proteins. Therefore, we named proteins undergoing DNA-dependent changes in thermal behavior, in the absence of prion-like structure, “Tetz-proteins”.

Next, we analyzed the association between proteins that acquired DNA-induced heat resistance and human pathologies. According to the literature, many of them were related to a variety of diseases, predominantly cancers. Consistently, some of them are known as tumor biomarkers and participate in tumor progression45–48.

Our findings suggested a novel role of bacterial eDNA in disease development, and cancer development in particular, consistent with its reported presence of eDNA in the systemic circulation in association with cancer and other human diseases20,49. Indeed, recent studies have shown that patients with non-infectious early-onset cancer display elevated plasma levels of eDNA from bacteria, particularly Pseudomonas spp., and Pannonibacter spp.20. Therefore, for the treatment of plasma samples we used a fixed concentration of bacterial or human DNA, 1 µg/mL, which was selected based on previous studies reporting the presence of similar concentrations of circulating cfDNA in patients with cancer21,50.

We next studied the presence and composition of heat-resistant proteins in the plasma of patients with pancreatic cancer. This type of cancer was selected because the majority of proteins that became heat-resistant following bacterial eDNA exposure had been found to be associated with this pathology.

The heat-resistant proteome of cancer patients was compared with that of control plasma, before and after the exposure to eDNA. PCA revealed that, after treatment with different DNAs, the proteome from control plasma acquired non-statistically significant changes in heat resistance that made it more similar to that of plasma samples from cancer patients. We believe that studies on larger sample cohorts may yield statistically significant results. CD5L, EIF5A1, FINC, and SEPP1 particularly attracted our attention as, according to the literature, they are associated with tumorigenesis46,51–53. In the present study, heat-resistant fractions of these proteins were identified in pancreatic cancer plasma, but not in normal plasma, and formed only after eDNA treatment, suggesting a role of this conversion in tumorigenesis.

It is tempting to speculate that DNA, including bacterial eDNA, may function as a virulence factor through the interaction with (and the alteration of) Tetz-proteins, including those associated with tumor growth. Therefore, it is possible that under certain conditions, eDNA elevation triggers alterations in plasma proteins that, in turn, may be relevant for tumorigenesis or other pathologies. We also found an effect of eDNA on proteins implicated in neurodegeneration and psychotic disorders. Experiments aimed at the characterization of the pathogenic role of different types of bacterial eDNA are in progress.

Methods

Plasma samples

Human plasma samples from 10 healthy donors (age: 55–66 years, 50% females) and 10 patients with clinically diagnosed pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (age: 52–72 years, 50% females) were obtained from Bioreclamation IVT (NY, USA), Discovery Life Sciences (Los Osos, CA), Human Microbiology Institute (NY, USA). All patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma had been diagnosed by histological examination and had not undergone surgical treatment, preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The basic demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 4. All samples were obtained with prior informed consent at all facilities. Plasma samples were stored at −80 °C until use. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Human Microbiology Institute (114–40) and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Extracellular DNA

DNA was extracted from the extracellular matrix of P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, E. coli ATCC 25922, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Streptococcus mitis VT-189. All bacterial strains were subcultured from freezer stocks onto Columbia agar plates (Oxoid Ltd., London, England) and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. To extract the extracellular DNA, bacterial cells were separated from the matrix by centrifugation at 5000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was aspirated and filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size cellulose acetate filter (Millipore Corporation, USA). eDNA was extracted by using a DNeasy kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer, or by the phenol-chloroform method54. Human genomic DNA (0.2 g/L in 10 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, Cat. No. 11691112001) was purchased from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich) and consisted of a high molecular weight >50.000 bp genomic DNA isolated from human blood according to the protocol described by Sambrook55.

Plasma exposure to eDNA

DNA was added to plasma samples at the final concentration of 1 µg/mL, incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, and boiled in a water bath at 100 °C for 15 min (by that time all the samples formed clods of coagulated proteins). Samples were cooled at room temperature for 30 min and centrifuged at 5000 g for 10 min at room temperature. The supernatant was aspirated and filtered through a 0.2-μm pore size cellulose acetate filter (Millipore Corporation, USA).

Protein identification by LS-MS

The filtered protein-containing supernatant was diluted in a final volume of 100 µL using 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8, and quantified using a Nanodrop OneC Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cysteine residues were reduced using 5 mM dithiothreitol at room temperature for 1.5 h and alkylated with 10 mM iodoacetamide at room temperature for 45 min in the dark. Proteins were then digested using modified trypsin (Promega, P/N V5113) at a 1:20 (w/w) enzyme:protein ratio for 16 h at 22 °C. After digestion, peptides were acidified to pH 3 with formic acid and desalted using Pierce Peptide Desalting Spin Columns (P/N 89852), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Eluted, desalted peptides were dried down to completion using a Labconco speedvac concentrator, resuspended in 0.1% formic acid and quantified again using a Nanodrop OneC Spectrophotometer56. For sample injection and mass analysis, peptides were diluted to a final concentration of 500 ng/µL using 0.1% formic acid in water to provide a total injection amount of 500 ng in a 1 µL of sample loop. Peptides were separated and their mass analyzed using a Dionex UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano ultra-high performance liquid chromatograph (UPLC) coupled to a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive HF hybrid quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometer (MS). A 1.5 hr reversed-phase UPLC method was used to separate peptides using a nanoEASE m/z peptide BEH C18 analytical column (Waters, P/N 186008795). The MS method included top 15 data-dependent acquisition for interrogation of peptides by MS/MS using HCD fragmentation. All raw data were searched against the human Uniprot protein database (UP000005640, accessed Apr 22, 2017) using the Andromeda search algorithm within the MaxQuant suite (v 1.6.0.1)57,58. The search results were filtered to a 1% FPR and visualized using Scaffold (v4, Proteome Software).

A cut-off of at least 5 spectral counts per probe was applied for protein selection59–61.

The obtained data were used to generate a heatmap. The abundance values were log converted (zero values were replaced with infinitely small number “1”) and plotted with R-statistical computing (https://www.r-project.org/), using the “levelplot” package. The color key indicates a range between the lowest (black) and the highest (yellow) values.

Principal components analysis was performed using the prcomp function with default parameters (zero values were replaced with 1) of the R software (https://www.r-project.org/).

Identification of prion-like domains (PrDs) in proteins

The presence of prion-like domains in the proteins was assessed using the PLAAC prion prediction algorithm, which establishes the prionogenic nature on the basis of the asparagine (Q) and glutamine (N) content, using the hidden Markov model (HMM)43,62. The output probabilities for the PrD states in PLAAC were estimated based on the amino acid frequencies in the PrDs of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Here, we used Alpha = 0.0, representing species-independent scanning, to identify the PrDs.

Acknowledgements

All mass spectrometry experiments were conducted by Dr. Jeremy L. Balsbaugh, Director of the Proteomics & Metabolomics Facility, a laboratory which is part of the University of Connecticut’s Center for Open Research Resources & Equipment.

Author contributions

V.T. designed and conducted the experiments. V.T. and G.T. analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

The other sequencing datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cryan J, Dinan T. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behavior. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2012;13:701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clemente J, Ursell L, Parfrey L, Knight R. The Impact of the Gut Microbiota on Human Health: An Integrative View. Cell. 2012;148:1258–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tetz, G. et al. Bacteriophages as potential new mammalian pathogens. Sci. Rep. 7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Tetz G, Brown SM, Hao Y, Tetz V. Type 1 Diabetes: an Association Between Autoimmunity the Dynamics of Gut Amyloid-producing E. coli and Their Phages. BioRxiv. 2018;1:433110. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46087-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tetz, G., Brown, S., Hao, Y. & Tetz, V. Parkinson’s disease and bacteriophages as its overlooked contributors. Scientific Reports8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Gąsiorowski K, Brokos B, Echeverria V, Barreto G, Leszek J. RAGE-TLR Crosstalk Sustains Chronic Inflammation in Neurodegeneration. Molecular Neurobiology. 2017;55:1463–1476. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0419-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitchurch C. Extracellular DNA Required for Bacterial Biofilm Formation. Science. 2002;295:1487–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.295.5559.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molin S, Tolker-Nielsen T. Gene transfer occurs with enhanced efficiency in biofilms and induces enhanced stabilisation of the biofilm structure. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2003;14:255–261. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(03)00036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinberger R, Holden P. Extracellular DNA in Single- and Multiple-Species Unsaturated Biofilms. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71:5404–5410. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5404-5410.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz K, Ganesan M, Payne D, Solomon M, Boles B. Extracellular DNA facilitates the formation of functional amyloids in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Molecular Microbiology. 2015;99:123–134. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rambaran RN, Serpell LC. Amyloid fibrils: abnormal protein assembly. Prion. 2008;2:112–117. doi: 10.4161/pri.2.3.7488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tursi SA, et al. Bacterial amyloid curli acts as a carrier for DNA to elicit an autoimmune response via TLR2 and TLR9. PLoS pathogens. 2017;13:e1006315. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galea C, et al. Large-Scale Analysis of Thermostable, Mammalian Proteins Provides Insights into the Intrinsically Disordered Proteome. Journal of Proteome Research. 2009;8:211–226. doi: 10.1021/pr800308v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narasimhan D, et al. Structural analysis of thermostabilizing mutations of cocaine esterase. Protein Engineering, Design and Selection. 2010;23:537–547. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, et al. Methods to determine intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation during liver disease. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2015;421:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tetz G, Brown SM, Hao Y, Tetz V. Type 1 Diabetes: an Association Between Autoimmunity the Dynamics of Gut Amyloid-producing E. coli and Their Phages. Scientific reports. 2019;9:9685. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46087-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santis A. Intestinal Permeability in Non-alcoholic Fatty LIVER Disease: The Gut-liver Axis. Reviews on Recent. Clinical Trials. 2015;9:141–147. doi: 10.2174/1574887109666141216104334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swarup V, Rajeswari M. Circulating (cell-free) nucleic acids - A promising, non-invasive tool for early detection of several human diseases. FEBS Letters. 2007;581:795–799. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snyder M, Kircher M, Hill A, Daza R, Shendure J. Cell-free DNA Comprises an In Vivo Nucleosome Footprint that Informs Its Tissues-Of-Origin. Cell. 2016;164:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang, Y. et al. Analysis of microbial sequences in plasma cell-free DNA for early-onset breast cancer patients and healthy females. BMC Medical Genomics11 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Wu T, et al. Cell-free DNA: measurement in various carcinomas and establishment of normal reference range. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2002;321:77–87. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(02)00091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emery, D. et al. 16S rRNA Next Generation Sequencing Analysis Shows Bacteria in Alzheimer’s Post-Mortem Brain. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Zhao W, Liu D, Chen Y. Escherichia coli hijack Caspr1 receptor to invade cerebral vascular and neuronal hosts. Microbial Cell. 2018;5:418–420. doi: 10.15698/mic2018.09.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dominy S, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Science Advances. 2019;5:eaau3333. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amarasekara R, Jayasekara R, Senanayake H, Dissanayake V. Microbiome of the placenta in pre-eclampsia supports the role of bacteria in the multifactorial cause of pre-eclampsia. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2014;41:662–669. doi: 10.1111/jog.12619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mydock-McGrane L, et al. Antivirulence C-Mannosides as Antibiotic-Sparing, Oral Therapeutics for Urinary Tract Infections. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2016;59:9390–9408. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dikshit N, et al. Intracellular Uropathogenic E. coli Exploits Host Rab35 for Iron Acquisition and Survival within Urinary Bladder Cells. PLOS Pathogens. 2015;11:e1005083. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalpke A, Frank J, Peter M, Heeg K. Activation of Toll-Like Receptor 9 by DNA from Different Bacterial Species. Infection and Immunity. 2006;74:940–946. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.940-946.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crawley J, Heyer W, LaSalle J. Autism and Cancer Share Risk Genes, Pathways, and Drug Targets. Trends in Genetics. 2016;32:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper, J. et al. Multimodel inference for biomarker development: an application to schizophrenia. Translational Psychiatry9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.La Y, et al. Decreased levels of apolipoprotein A-I in plasma of schizophrenic patients. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2006;114:657–663. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0607-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan I, et al. The SON gene encodes a conserved DNA binding protein mapping to human chromosome 21. Annals of Human Genetics. 1994;58:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1994.tb00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paz I, Kligun E, Bengad B, Mandel-Gutfreund Y. BindUP: a web server for non-homology-based prediction of DNA and RNA binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Research. 2016;44:W568–W574. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Si J, Zhao R, Wu R. An Overview of the Prediction of Protein DNA-Binding Sites. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015;16:5194–5215. doi: 10.3390/ijms16035194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kask L, et al. Structural stability and heat-induced conformational change of two complement inhibitors: C4b-binding protein and factor H. Protein Science. 2004;13:1356–1364. doi: 10.1110/ps.03516504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Privalov P, Dragan A. Microcalorimetry of biological macromolecules. Biophysical Chemistry. 2007;126:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kopp A, Hebecker M, Svobodová E, Józsi M. Factor H: A Complement Regulator in Health and Disease, and a Mediator of Cellular Interactions. Biomolecules. 2012;2:46–75. doi: 10.3390/biom2010046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saverioni D, et al. Analyses of Protease Resistance and Aggregation State of Abnormal Prion Protein across the Spectrum of Human Prions. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288:27972–27985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.477547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abd-Elhadi, S. et al. Total and Proteinase K-Resistant α-Synuclein Levels in Erythrocytes, Determined by their Ability to Bind Phospholipids, Associate with Parkinson’s Disease. Scientific Reports5 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Zheng, Z. et al. Structural basis for the complete resistance of the human prion protein mutant G127V to prion disease. Scientific Reports8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Schwartz K, Ganesan M, Payne D, Solomon M, Boles B. Extracellular DNA facilitates the formation of functional amyloids inStaphylococcus aureusbiofilms. Molecular Microbiology. 2015;99:123–134. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gallo P, et al. Amyloid-DNA Composites of Bacterial Biofilms Stimulate Autoimmunity. Immunity. 2015;42:1171–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lancaster A, Nutter-Upham A, Lindquist S, King O. PLAAC: a web and command-line application to identify proteins with prion-like amino acid composition. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2501–2502. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.An, L., Fitzpatrick, D. & Harrison, P. Emergence and evolution of yeast prion and prion-like proteins. BMC Evolutionary Biology16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Sogawa K, et al. Identification of a novel serum biomarker for pancreatic cancer, C4b-binding protein α-chain (C4BPA) by quantitative proteomic analysis using tandem mass tags. British Journal of Cancer. 2016;115:949–956. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barrett C, Short S, Williams C. Selenoproteins and oxidative stress-induced inflammatory tumorigenesis in the gut. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2016;74:607–616. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2339-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guerrico A, et al. Roles of kallikrein-2 biomarkers (free-hK2 and pro-hK2) for predicting prostate cancer progression-free survival. Journal of Circulating Biomarkers. 2017;6:184945441772015. doi: 10.1177/1849454417720151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanjurjo, L. et al. CD5L Promotes M2 Macrophage Polarization through Autophagy-Mediated Upregulation of ID3. Frontiers in Immunology9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Meisel M, et al. Microbial signals drive pre-leukaemic myeloproliferation in a Tet2-deficient host. Nature. 2018;557:580–584. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0125-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tomochika S, et al. Increased serum cell-free DNA levels in relation to inflammation are predictive of distant metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2010;1:89–92. doi: 10.3892/etm_00000016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li Y, et al. Api6/AIM/Sp /CD5L Overexpression in Alveolar Type II Epithelial Cells Induces Spontaneous Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Research. 2011;71:5488–5499. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mathews M, Hershey J. The translation factor eIF5A and human cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 2015;1849:836–844. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Han S, Roman J. Fibronectin induces cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in human bronchial epithelial cells: pro-oncogenic effects mediated by PI3-kinase and NF-κB. Oncogene. 2006;25:4341–4349. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Armstrong K. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. T. Maniatis, E. F. Fritsch, J. Sambrook. The Quarterly Review of Biology. 1983;58:234–234. doi: 10.1086/413230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sambrook, J., Russell, D.W. Isolation of high-molecular-weight DNA from mammalian cells using formamide. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols1, pdb-rot3225 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Dayon L, Kussmann M. Proteomics of human plasma: A critical comparison of analytical workflows in terms of effort, throughput and outcome. EuPA Open Proteomics. 2013;1:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.euprot.2013.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cox J, et al. Andromeda: A Peptide Search Engine Integrated into the MaxQuant Environment. Journal of Proteome Research. 2011;10:1794–1805. doi: 10.1021/pr101065j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Research45, D158–D169 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Sigdel T, et al. Shotgun proteomics identifies proteins specific for acute renal transplant rejection. Proteomics - Clinical Applications. 2010;4:32–47. doi: 10.1002/prca.200900124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tu C, et al. Depletion of Abundant Plasma Proteins and Limitations of Plasma Proteomics. Journal of Proteome Research. 2010;9:4982–4991. doi: 10.1021/pr100646w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li M, et al. Comparative Shotgun Proteomics Using Spectral Count Data and Quasi-Likelihood Modeling. Journal of Proteome Research. 2010;9:4295–4305. doi: 10.1021/pr100527g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eddy S. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:755–763. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takata T, et al. Characterization of proteins secreted by pancreatic cancer cells with anticancer drug treatment in vitro. Oncology Reports. 2012;28:1968–1976. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bloomston M, et al. Fibrinogen γ Overexpression in Pancreatic Cancer Identified by Large-scale Proteomic Analysis of Serum Samples. Cancer Research. 2006;66:2592–2599. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maehara S, et al. Selenoprotein P, as a predictor for evaluating gemcitabine resistance in human pancreatic cancer cells. International Journal of Cancer. 2004;112:184–189. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seldon C, et al. Chromodomain-helicase-DNA binding protein 5, 7 and pronecrotic mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein serve as potential prognostic biomarkers in patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinomas. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 2016;8:358. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i4.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pan S, et al. Protein Alterations Associated with Pancreatic Cancer and Chronic Pancreatitis Found in Human Plasma using Global Quantitative Proteomics Profiling. Journal of Proteome Research. 2011;10:2359–2376. doi: 10.1021/pr101148r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Crnogorac-Jurcevic T, et al. Molecular alterations in pancreatic carcinoma: expression profiling shows that dysregulated expression of S100 genes is highly prevalent. The Journal of Pathology. 2003;201:63–74. doi: 10.1002/path.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao J, Simeone D, Heidt D, Anderson M, Lubman D. Comparative Serum Glycoproteomics Using Lectin Selected Sialic Acid Glycoproteins with Mass Spectrometric Analysis: Application to Pancreatic Cancer Serum. Journal of Proteome Research. 2006;5:1792–1802. doi: 10.1021/pr060034r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nie S, et al. Quantitative Analysis of Single Amino Acid Variant Peptides Associated with Pancreatic Cancer in Serum by an Isobaric Labeling Quantitative Method. Journal of Proteome Research. 2014;13:6058–6066. doi: 10.1021/pr500934u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cecconi D, Palmieri M, Donadelli M. Proteomics in pancreatic cancer research. Proteomics. 2011;11:816–828. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martín-Morales L, et al. SETD6 dominant negative mutation in familial colorectal cancer type X. Human Molecular Genetics. 2017;26:4481–4493. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oshima, T. et al. Clinicopathological significance of the gene expression of matrix metalloproteinases and reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs in patients with colorectal cancer: MMP-2 gene expression is a useful predictor of liver metastasis from colorectal cancer. Oncology Reports, 10.3892/or.19.5.1285 (2008) [PubMed]

- 74.Borgquist S, et al. Apolipoproteins, lipids and risk of cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2016;138:2648–2656. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Woong-Shick A, et al. Identification of hemoglobin-alpha and -beta subunits as potential serum biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of ovarian cancer. Cancer Science. 2005;96:197–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang J, et al. EIF5A1 promotes epithelial ovarian cancer proliferation and progression. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2018;100:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang J, Hielscher A. Fibronectin: How Its Aberrant Expression in Tumors May Improve Therapeutic Targeting. Journal of Cancer. 2017;8:674–682. doi: 10.7150/jca.16901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mohamed E, et al. Lectin-based electrophoretic analysis of the expression of the 35 kDa inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4 fragment in sera of patients with five different malignancies. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:2645–2650. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Heo S, Lee S, Ryoo H, Park J, Cho J. Identification of putative serum glycoprotein biomarkers for human lung adenocarcinoma by multilectin affinity chromatography and LC-MS/MS. Proteomics. 2007;7:4292–4302. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ajona D, et al. Expression of Complement Factor H by Lung Cancer Cells. Cancer Research. 2004;64:6310–6318. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sun Y, et al. Systematic comparison of exosomal proteomes from human saliva and serum for the detection of lung cancer. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2017;982:84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zeng X, et al. Lung Cancer Serum Biomarker Discovery Using Label-Free Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2011;6:725–734. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31820c312e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Forconi F, et al. Selective influences in the expressed immunoglobulin heavy and light chain gene repertoire in hairy cell leukemia. Haematologica. 2008;93:697–705. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Darling V, Hauke R, Tarantolo S, Agrawal D. Immunological effects and therapeutic role of C5a in cancer. Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 2014;11:255–263. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2015.983081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen N, et al. Cytokeratin expression in malignant melanoma: potential application of in-situ hybridization analysis of mRNA. Melanoma Research. 2009;19:87–93. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3283252feb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cooper M, et al. Interaction between Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in Selenoprotein P and Mitochondrial Superoxide Dismutase Determines Prostate Cancer Risk. Cancer Research. 2008;68:10171–10177. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Persson-Moschos M, Stavenow L, Åkesson B, Lindgärde F. Selenoprotein P in Plasma in Relation to Cancer Morbidity in Middle-Aged Swedish Men. Nutrition and Cancer. 2000;36:19–26. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC3601_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Darson M, et al. Human glandular kallikrein 2 (hK2) expression in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and adenocarcinoma: A novel prostate cancer marker. Urology. 1997;49:857–862. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Huizen I. Establishment of a Serum Tumor Marker for Preclinical Trials of Mouse Prostate Cancer Models. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11:7911–7919. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Malik G, et al. Serum levels of an isoform of apolipoprotein A-II as a potential marker for prostate cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11:1073–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Raitanen M, et al. Human Complement Factor H Related Protein Test For Monitoring Bladder Cancer. Journal of Urology. 2001;165:374–377. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200102000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Origa R. β-Thalassemia. Genetics in Medicine. 2016;19:609–619. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The other sequencing datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.