Abstract

Screening for HIV in Emergency Departments (EDs) is recommended to address the problem of undiagnosed HIV. Serosurveys are an important method for estimating the prevalence of undiagnosed HIV and can provide insight into the effectiveness of an HIV screening strategy. We performed a blinded serosurvey in an ED offering non-targeted HIV screening to determine the proportion of patients with undiagnosed HIV who were diagnosed during their visit. The study was conducted in a high-volume, urban ED and included patients who had blood drawn for clinical purposes and had sufficient remnant specimen to undergo deidentified HIV testing. Among 4,752 patients not previously diagnosed with HIV, 1,403 (29.5%) were offered HIV screening and 543 (38.7% of those offered) consented. Overall, undiagnosed HIV was present in 12 patients (0.25%): six among those offered screening (0.4%), and six among those not offered screening (0.2%). Among those with undiagnosed HIV, two (16.7%) consented to screening and were diagnosed during their visit. Despite efforts to increase HIV screening, more than 80% of patients with undiagnosed HIV were not tested during their ED visit. Although half of those with undiagnosed HIV were missed because they were not offered screening, the yield was further diminished because a substantial proportion of patients declined screening. To avoid missed opportunities for diagnosis in the ED, strategies to further improve implementation of HIV screening and optimize rates of consent are needed.

Keywords: HIV screening, Emergency Department, Serosurvey, Undiagnosed HIV

INTRODUCTION

Increased HIV screening in Emergency Departments (EDs) has been a public health goal since 2006 when the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released revised recommendations for HIV screening in healthcare settings. These revisions included a recommendation to screen all patients between the ages of 13 and 64 regardless of risk at least once (Branson et al., 2006). The rationale was that screening strategies focusing on those perceived to be at high-risk for HIV had, as implemented, failed to diagnose a substantial proportion of those who are HIV-infected. Those who are infected but undiagnosed do not have the opportunity to enter care and receive antiretroviral therapy, leading to adverse health outcomes for themselves (Chadborn, Delpech, Sabin, Sinka, & Evans, 2006; Palella et al., 2003) and disproportionate onward transmission of the virus. EDs have been a focus of expanded screening efforts because they are thought to serve populations that, for multiple reasons, may be at risk for HIV and may not undergo recommended preventive health screenings in non-emergency settings (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2006; Liddicoat et al., 2004).

Many different strategies have been employed to expand HIV screening in EDs. Variations in the components of these strategies include how consent for screening is obtained (e.g. opt-in vs. opt-out), type of screening performed (e.g. point of care oral swab vs. blood specimen processed in central laboratory), staff responsible for offering screening (e.g. dedicated counselor vs. native ED staff), and use of ancillary technology to augment screening rates (e.g. informational videos and self-serve kiosks). Increased rates of HIV screening have been seen across a variety of strategies using different combinations of these components (Calderon et al., 2009; Hankin, Freiman, Copeland, Travis, & Shah, 2016; Haukoos et al., 2010; Hsieh et al., 2014; Montoy, Dow, & Kaplan, 2016; Signer et al., 2016; Walensky et al., 2011; White, Scribner, & Huang, 2009).

Few of the studies evaluating expanded ED-based HIV screening strategies, however, have accounted for the underlying prevalence of undiagnosed HIV when addressing the effectiveness of these different strategies for identifying previously undiagnosed individuals. A fundamental challenge is that, because this target population is undiagnosed, the prevalence of undiagnosed HIV in the population exposed to a particular HIV screening strategy is rarely known. Understanding the effectiveness of a strategy is critical for making evidence-based decisions regarding allocation of resources, change-of-course, scale-up, and dissemination.

Methods to estimate the prevalence of undiagnosed HIV include evaluations of “missed opportunities” in which healthcare interactions of patients preceding an HIV diagnosis are assessed for whether HIV testing could have been performed at this earlier time. Blinded serosurveys are another important method for determining the prevalence of HIV, whether diagnosed or undiagnosed (Trepka, Davidson, & Douglas, 1996). Because most states require patient consent either via opt-in or opt-out models prior to performing any HIV test, a strength of using a blinded serosurvey is that by testing only deidentified specimens for the presence of HIV, this method allows for an estimate of HIV prevalence unbiased by patient willingness to consent (CDC, n.d.). The prevalence of undiagnosed HIV can be further clarified if methods are applied to distinguish cases of HIV that have been previously diagnosed from those that have not.

In this study, we used the results of a blinded serosurvey to assess the effectiveness of an ED-based expanded HIV screening strategy for detecting patients with previously undiagnosed HIV. In addition, we describe the points in the screening strategy where those who remained undiagnosed were missed.

METHODS

Study Design

We used the data obtained in a blinded HIV serosurvey of ED patients to determine how many of the patients identified with undiagnosed HIV by the serosurvey were also screened for HIV as part of the care they received while in the ED. The Institutional Review Boards of Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH) deemed the study to be non-human subjects research and public health surveillance, respectively.

Setting

The study was performed in one adult ED of the Montefiore Health System (MHS), the largest health system in the Bronx, NY, a borough of New York City which has an estimated HIV prevalence of 2.0% (NYC DOHMH, 2017). The ED serves patients who are at least 21 years old and has an annual census of approximately 110,000 visits.

Population

All patients who presented to the ED from March 8 to May 8, 2015 were eligible for inclusion in the serosurvey. The first 4,990 consecutive patients who had blood drawn for clinical purposes in the ED and had sufficient remnant specimen to undergo HIV testing for the serosurvey were included in this analysis.

Methods for the serosurvey

The serosurvey methods and results have been previously described (Torian et al., 2018). The size of the serosurvey was powered to detect differences in the prevalence of HIV according to key demographic characteristics. Remnant specimens from blood drawn for clinical purposes were salvaged from the central laboratory. Identifiers attached to the specimen were matched to the source patient’s clinical and demographic data from the EMR. Each patient and the associated specimen were assigned a unique serosurvey ID. Before being stripped of all identifying information, this dataset was matched to the New York City HIV surveillance registry to identify patients already known to be HIV-positive. The registry includes all HIV-positive patients who are diagnosed with or receiving HIV care in NYC based on the required named reporting of HIV-related laboratory tests. After deidentification, specimens were sent to a commercial laboratory for HIV testing using a fourth-generation screening assay (Abbott Laboratories, Lake Bluff, IL) supplemented, for all repeatedly reactive results, by a second-generation type differentiation assay (BioRad Laboratories, Redmond, WA). Specimens that were repeatedly reactive on fourth-generation screening but negative or indeterminate on supplemental confirmatory testing also underwent qualitative testing for the presence of HIV-1 RNA (Hologic Laboratories, Bedford, MA).

Expanded HIV Screening in the ED during the serosurvey

During the serosurvey, the HIV screening strategy in the ED relied on a non-targeted, opt-in approach in which, after being triaged, patients were offered HIV screening by either their primary nurse or provider. Patients triaged to the main area of the ED (where the majority of patients have blood drawn for other purposes) who were offered and consented to HIV screening were tested using a fourth-generation assay (Abbott Laboratories, Lake Bluff, IL) on a blood specimen processed in the central laboratory. Preliminarily reactive results were confirmed using a second-generation differentiation assay (BioRad Laboratories, Redmond, WA) or, for those with nonreactive or indeterminate results on the differentiation assay, by qualitative viral load assay (Hologic Laboratories, Bedford, MA). Less acute patients triaged to the ED’s “Fast Track” (where a minority of patients have blood drawn for other purposes) who were offered and consented to HIV screening were tested using a second-generation oral swab (OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem, PA) collected by a provider and processed in the central lab. Reactive oral swabs were confirmed with the fourth-generation protocol described above. All orders for HIV tests or documentation that the patient declined HIV screening when offered were entered by the ED nurse or provider in the EMR. During this period, there was no systematic reminder integrated into the workflow to prompt providers to offer HIV screening, nor was there a uniform script for how the offer was delivered by different providers.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was whether a patient identified as having undiagnosed HIV by the serosurvey was screened for HIV as part of their care in the ED. Secondary outcomes included whether patients with undiagnosed HIV were offered and consented to HIV screening while in the ED.

Data sources, variables, and definitions

The de-identified dataset contained clinical and demographic data extracted from the MHS EMR and was linked with the results of the HIV serosurvey. A patient was considered to have been offered HIV screening during their ED visit if there was a completed HIV test from the ED visit or there was documentation in the EMR that the patient was offered and declined HIV screening.

Statistical analyses

The unit of analysis was unique patients. Patients with multiple visits during the study period were included at the time of their earliest visit in which an adequate specimen for the serosurvey was obtained. Descriptive statistics are presented as frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables.

RESULTS

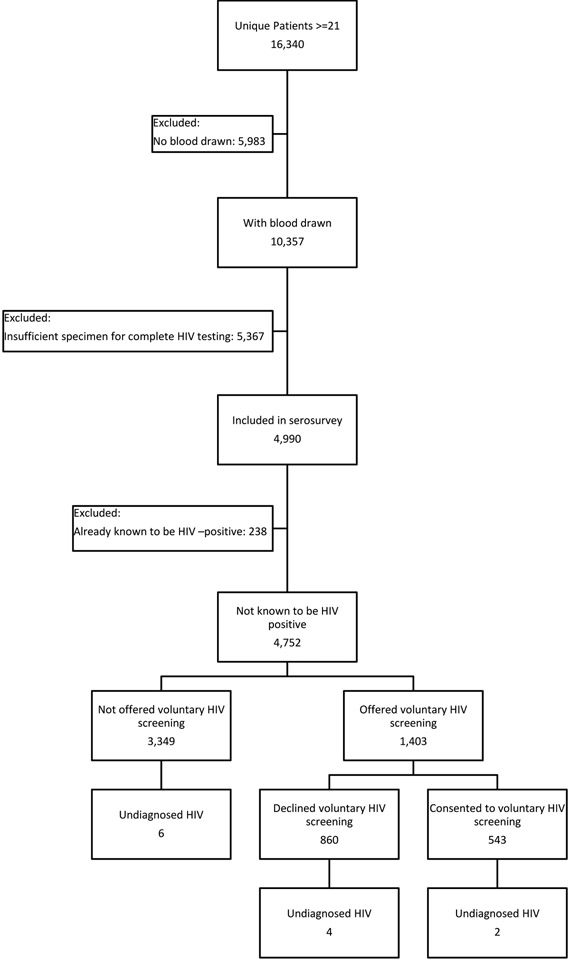

Among 16,340 unique patients presenting to the ED during the study period, 10,357 (63.0%) had blood drawn as part of their clinical care. The first 4,990 specimens with sufficient leftover serum to complete the 2- or 3-step HIV testing algorithm were selected for the serosurvey Among this group, 238 (4.8%) were found to have previously diagnosed HIV according to the match with the NYC HIV registry (Figure).

Figure 1.

Study flow.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 4,752 patients included in the serosurvey who did not match to the NYC HIV registry are detailed in Table 1. The majority (62.2%) were female, 85.3% were non-Hispanic black or Hispanic, and the median age was 55 years (IQR 35–65). A total of 12 patients (0.3%) with undiagnosed HIV were included in the serosurvey.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study patients by whether they were offered voluntary HIV screening during ED visit‡

| Total (n= 4,752) |

Not Offered HIV test (n= 3,349) |

Offered HIV test (n= 1,403) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 2,957 (62.2) | 2,067 (61.7) | 890 (63.4) |

| Male | 1,795 (37.8) | 1,282 (38.3) | 513 (36.6) |

| Age (years, category) | |||

| 21–29 | 777 (16.4) | 447 (13.4) | 330 (23.5) |

| 30–39 | 742 (15.6) | 470 (14.0) | 272(19.4) |

| 40–49 | 733 (15.4) | 457 (13.7) | 276 (19.7) |

| 50–59 | 898 (18.9) | 602 (18.0) | 296 (21.1) |

| 60–64 | 409 (8.6) | 315 (9.4) | 94 (6.7) |

| 65+ | 1,193 (25.1) | 1,058 (31.6) | 135 (9.6) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 2,557 (53.8) | 1,781 (53.2) | 776 (55.3) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1,495 (31.5) | 1,063 (31.7) | 432 (30.8) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 309 (6.5) | 238 (7.1) | 71 (5.1) |

| Other† | 296 (6.2) | 203 (6.1) | 93 (6.6) |

| Unknown/Missing | 95 (2.0) | 64 (1.9) | 31 (2.2) |

| Discharge disposition | |||

| Discharged home | 2,801 (58.9) | 1,857 (55.5) | 944 (67.3) |

| Admitted to hospital | 1,759 (37.0) | 1,358 (40.6) | 401 (28.6) |

| Other± | 192 (4.0) | 134 (4.0) | 58 (4.1) |

| Consented to HIV voluntary screening in ED* | |||

| No | -- | -- | 860 (61.3) |

| Yes | -- | -- | 543 (38.7) |

| Undiagnosed HIV identified in serosurvey | |||

| No | 4,740 (99.8) | 3,343 (99.8) | 1,397 (99.6) |

| Yes | 12 (0.3) | 6 (0.2) | 6 (0.4) |

Excluding those with previously diagnosed HIV

Only patients offered an HIV test had the opportunity to consent

Includes Asian, Multiracial, American Indian and Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, or other

Includes those who eloped, left against medical advice, expired, were admitted to psychiatric unit, or transferred to adult home or skilled nursing facility

Table 1 also displays patient characteristics according to whether the patient was offered HIV testing during the ED visit. Overall, 1,403 (29.5%) of patients were offered HIV testing during their ED visit, and 3,349 (70.5%) were not offered. Among those offered, 543 (38.7%) consented and were tested. Undiagnosed HIV was present in six (0.2%) who were not offered testing and six (0.4%) who were offered testing, two of whom consented and were tested. Therefore, among the 12 patients with undiagnosed HIV in the study, two (16.7%) were diagnosed during their visit.

DISCUSSION

Our ED-based expanded HIV screening strategy failed to diagnose more than 80% of the patients with undiagnosed HIV who presented for care. This finding reinforces the ongoing need for strategies to increase the likelihood that those with undiagnosed HIV are offered and consent to HIV screening when accessing care in the ED. Furthermore, our study demonstrates the value of pairing an assessment of the prevalence of undiagnosed HIV with an HIV screening strategy in order to evaluate the effectiveness of that strategy.

By performing an HIV serosurvey on deidentified remnant specimens and matching the ED census to a public health registry of known HIV-positive individuals, we were able to estimate the prevalence of undiagnosed HIV among patients in our ED unbiased by patient willingness to undergo HIV screening or willingness to disclose HIV status. By situating these results within the context of an active expanded HIV screening strategy, we are able to trace where in the process of that strategy the patients with undiagnosed HIV were effectively excluded from being diagnosed with HIV during their ED visit.

The earliest consequential point in the process, in which half of those with undiagnosed HIV lost the opportunity to undergo HIV screening, was at the point of offering. In contrast to strategies in which the default option is that screening will be performed, our expanded screening strategy relied on a proactive offer of screening by an ED nurse or provider. The second consequential point in the process, in which an additional one-third of those with undiagnosed HIV lost the opportunity for screening, was at the point of consent. Although New York State (NYS) has recently revised the regulations governing HIV testing to minimize the chances that pre-test counseling and consent act as barriers to routine screening (NYS Department of Health, n.d.), as in most states (CDC, n.d.), explicit consent from the patient is still required. Notably, the overall proportions of patients offered (29.5%) and consenting (38.7% of those offered, 11.4% of total patients) to HIV screening under our strategy are only slightly lower than the averages for other ED-based opt-in strategies in the published literature (Haukoos, Lyons, White, Hsieh, & Rothman, 2014).

Our finding that only a modest proportion (16.7%) of those with undiagnosed HIV was identified through our screening strategy is consistent with prior literature that has included assessments of undiagnosed HIV as part of an evaluation of ED-based HIV screening strategies. Studies either reporting or allowing for an extrapolation of the proportion of cases of undiagnosed HIV identified by the screening strategy have found the following: by testing 17.7%, 7.2% , 40.7% , and 64.3% of those eligible, 2.7% (Hsieh et al., 2016), 33.3% (Goggin, Davidson, Cantril, O’Keefe, & Douglas, 2000), 35.2% (Lyons et al., 2013), and 39.5% (Czarnogorski et al., 2011) of those with undiagnosed HIV were identified, respectively. When considering these results, it is critical to note significant heterogeneity among these studies that were performed at different points in the HIV epidemic, in ED settings with differing underlying estimates of undiagnosed HIV, evaluated a variety of different screening strategies, differentiated diagnosed and undiagnosed cases of HIV differently, and used different definitions of the population considered eligible for testing.

In addition to serosurveys, “missed opportunity” studies are another way to estimate the effectiveness of screening strategies for identifying patients with undiagnosed HIV. These studies retrospectively review the healthcare interactions of HIV-positive patients preceding their diagnosis for opportunities when an earlier diagnosis of HIV could have occurred. This method assumes that the patient was already infected (but undiagnosed) during the earlier visit. Using this method, White et al. describe that among 95 patients testing positive for HIV via an ED-based screening program in which testing occurred in fewer than 10% of ED visits, 66 (69.5%) were diagnosed during their first visit while 29 (30.5%) required at least one subsequent visit to the ED prior to being diagnosed (2009). While these results suggest that, compared tour own study and the studies using serosurveys described above, the ED-screening program under review more effectively identified those with undiagnosed HIV, it must be noted that “missed opportunity” studies likely underestimate the prevalence of undiagnosed HIV because they cannot account for those cases which are yet to be identified.

Our study has limitations. First, the estimated prevalence of undiagnosed HIV is limited to those who had blood drawn during their ED visit. Although nearly two-thirds of patients during the study period had blood drawn, they tended to be older than the general population seeking care in the ED and therefore may misrepresent the actual prevalence of undiagnosed HIV in this population. Second, although matching to a robust public health registry to distinguish patients with diagnosed from undiagnosed HIV may be the most accurate option available, it is possible that patients who were diagnosed and/or receiving HIV care outside of public health authority’s jurisdiction were misclassified as having undiagnosed HIV. Finally, although our outcome of interest was the proportion of patients with undiagnosed HIV who were screened while in the ED, it is possible that some of those not screened in the ED may have been admitted to inpatient units where there are further opportunities to make a diagnosis. We have previously shown that approximately half of patients who decline HIV screening in the ED will consent if offered after their admission (Felsen, Cunningham, & Zingman, 2016).

By pairing our expanded HIV screening strategy with an objective measure of undiagnosed HIV, we demonstrated that merely implementing the strategy, even if it performs similarly to comparable programs in the literature, may be insufficient to effectively identify patients with undiagnosed HIV presenting for care in the ED. To minimize the likelihood that patients with undiagnosed HIV will be missed, further strategies to increase the proportions of patients with undiagnosed HIV who are offered and consent to screening are needed. Future studies evaluating screening strategies that address these deficiencies should include an assessment of undiagnosed HIV in order to demonstrate their effectiveness towards increasing the proportion of those with HIV who are aware of their status, a prerequisite for ending the epidemic.

Funding:

This study was supported in part by NIH K23MH106386 [URF], and K24DA036955 [COC].

Disclosure statement: BSZ has received research grants from Cepheid to evaluate HIV viral load assays, as well as from Gilead to study antiretroviral agents. DCF has received unrestricted educational and clinical trial grants from Gilead. However, none of this funding is related to the work presented in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, … Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2006). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep, 55(RR-14), 1–17; quiz CE11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon Y, Leider J, Hailpern S, Chin R, Ghosh R, Fettig J, … Bauman L (2009). High-volume rapid HIV testing in an urban emergency department. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 23(9), 749–755. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). State HIV Laws. Retrieved April 18, 2018. from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/law/states/index.html

- CDC. (2006). Missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis of HIV infection--South Carolina, 1997–2005.MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 55(47), 1269–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2015). National HIV Prevention Progress Report. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies/progressreports/cdc-hiv-nationalprogressreport.pdf

- Chadborn TR, Delpech VC, Sabin CA, Sinka K, & Evans BG (2006). The late diagnosis and consequent short-term mortality of HIV-infected heterosexuals (England and Wales, 2000–2004). AIDS, 20(18), 2371–2379. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801138f7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnogorski M, Brown J, Lee V, Oben J, Kuo I, Stern R, & Simon G (2011). The Prevalence of Undiagnosed HIV Infection in Those Who Decline HIV Screening in an Urban Emergency Department. AIDS research and treatment, 2011, 879065. doi: 10.1155/2011/879065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsen UR, Cunningham CO, & Zingman BS (2016). Increased HIV testing among hospitalized patients who declined testing in the emergency department. AIDS Care, 28(5), 591–597. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1120268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goggin MA, Davidson AJ, Cantril SV, O’Keefe LK, & Douglas JM (2000). The extent of undiagnosed HIV infection among emergency department patients: results of a blinded seroprevalence survey and a pilot HIV testing program. J Emerg Med, 19(1), 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin A, Freiman H, Copeland B, Travis N, & Shah B (2016). A Comparison of Parallel and Integrated Models for Implementation of Routine HIV Screening in a Large, Urban Emergency Department. Public Health Rep, 131 Suppl 1, 90–95. doi: 10.1177/00333549161310S111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Conroy AA, Silverman M, Byyny RL, Eisert S, … Heffelfinger JD (2010). Routine opt-out rapid HIV screening and detection of HIV infection in emergency department patients. JAMA, 304(3), 284–292. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haukoos JS, Lyons MS, White DA, Hsieh YH, & Rothman RE (2014). Acute HIV infection and implications of fourth-generation HIV screening in emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med, 64(5), 547–551. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh YH, Gauvey-Kern M, Peterson S, Woodfield A, Deruggiero K, Gaydos CA, & Rothman RE (2014). An emergency department registration kiosk can increase HIV screening in high risk patients. J Telemed Telecare, 20(8), 454–459. doi: 10.1177/1357633X14555637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh YH, Kelen GD, Beck KJ, Kraus CK, Shahan JB, Laeyendecker OB, … Rothman RE (2016). Evaluation of hidden HIV infections in an urban ED with a rapid HIV screening program. Am J Emerg Med, 34(2), 180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddicoat RV, Horton NJ, Urban R, Maier E, Christiansen D, & Samet JH (2004). Assessing missed opportunities for HIV testing in medical settings. J Gen Intern Med, 19(4), 349–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21251.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, Ruffner AH, Wayne DB, Hart KW, Sperling MI, … Fichtenbaum CJ (2013). Randomized comparison of universal and targeted HIV screening in the emergency department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 64(3), 315–323. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a21611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoy JC, Dow WH, & Kaplan BC (2016). Patient choice in opt-in, active choice, and opt-out HIV screening: randomized clinical trial. BMJ, 532, h6895. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.(2017). New York City HIV/AIDS Annual Surveillance Statistics. Retrieved March 3,2018 from http://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/data/datasets/hiv-aids-annual-surveillance-statistics.page

- New York State Department of Health. Frequently asked questions regarding the HIV testing law. Retrieved April 3, 2018. from https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/aids/providers/testing/law/faqs.htm

- Palella FJ Jr., Deloria-Knoll M, Chmiel JS, Moorman AC, Wood KC, Greenberg AE, … Investigators, HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. (2003). Survival benefit of initiating antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected persons in different CD4+ cell strata. Ann Intern Med, 138(8), 620–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signer D, Peterson S, Hsieh YH, Haider S, Saheed M, Neira P, … Rothman RE (2016).Scaling Up HIV Testing in an Academic Emergency Department: An Integrated Testing Model with Rapid Fourth-Generation and Point-of-Care Testing. Public Health Rep, 131 Suppl 1, 82–89. doi: 10.1177/00333549161310S110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torian LV, Felsen UR, Xia Q, Laraque F, Rude EJ, Rose H, … Zingman BS (2018).Undiagnosed HIV and HCV Infection in a New York City Emergency Department, 2015. Am J Public Health, 108(5), 652–658. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trepka MJ, Davidson AJ, & Douglas JM Jr. (1996). Extent of undiagnosed HIV infection in hospitalized patients: assessment by linkage of seroprevalence and surveillance methods. Am J Prev Med, 12(3), 195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walensky RP, Reichmann WM, Arbelaez C, Wright E, Katz JN, Seage GR 3rd, … Losina E (2011). Counselorversus provider-based HIV screening in the emergency department: results from the universal screening for HIV infection in the emergency room (USHER) randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med, 58(1 Suppl 1), S126–132 e121–124. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DA, Scribner AN, & Huang JV (2009). A comparison of patient acceptance of fingerstick whole blood and oral fluid rapid HIV screening in an emergency department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 52(1), 75–78. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181afd33d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DA, Warren OU, Scribner AN, & Frazee BW (2009). Missed opportunities for earlier HIV diagnosis in an emergency department despite an HIV screening program. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 23(4), 245–250. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]