Abstract

Objectives:

To determine whether the trajectory of preclinical lap time variability from a 400-meter walk differentiates participants with future mild cognitive impairment (MCI)/Alzheimer’s disease (AD) from matched controls.

Design:

A case-control retrospective study embedded in a large longitudinal cohort study, the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA).

Setting:

In the BLSA, participants were scheduled for clinical visits, including mobility and cognitive assessments. Data reported here were collected between April 2007 and September 2017 (average follow-up 5.2±2.4 years).

Participants:

67 participants developed MCI/AD and 134 age-and sex-matched controls remained cognitively normal.

Measurements:

Diagnoses of MCI and AD were adjudicated at a consensus conference. The rate of change in lap time variability between MCI/AD cases prior to symptom onset and controls were compared using mixed effects linear regression, adjusted for baseline executive function, memory, gait speed, and changes in gait speed.

Results:

Compared to controls, eventual MCI/AD cases had a greater rate of increase in lap time variability prior to symptom onset (β=0.059, p=0.009). This association was independent of baseline cognition, gait speeds at baseline or change over time from a 6-meter or 400-meter walk.

Conclusion/Implications:

Independent of other early indicators and gait slowing, a greater rate of increase in lap time variability from a 400m walk differentiates individuals who eventually develop MCI/AD from controls, suggesting that early pathology affects the automaticity of walking. Lap time variability can be administered during routine clinical practice over time and might help identify individuals at risk for future MCI/AD.

Keywords: gait, automaticity, Alzheimer’s disease, early diagnosis, epidemiology

Article summary:

Independent of gait slowing, a greater increase in lap time variability differentiates eventual MCI/AD cases from cognitively normal controls. Assessing lap time variability routinely might help identify individuals at risk for AD.

Introduction

Intra-individual variability in speed-related motor performance increases with aging and is related to cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases.1,2 Increased intraindividual variability in motor performance can reflect brain abnormalities and may indicate early brain pathology and provides additional predictive value for future brain health beyond mean performance. Prior studies have shown that higher baseline lap time variability, which is the variability in lap time across ten laps from the well–established 400-meter walk, is strongly associated with poorer cognition and worse neuroimaging markers and predicts future age-related cognitive decline and mortality.3–7 Whether a longitudinal change in lap time variability, independent of mean performance, is associated with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease (MCI/AD), has not been studied.

In older adults, a rich body of research shows that higher step-to-step gait variability, such as stride time variability and stride length variability, is associated with worse neuroimaging markers of damage in brain areas important for sensorimotor integration, and is found in individuals with MCI and AD.8 Whether the longitudinal trajectory of gait variability, over and beyond gait speed, is associated with future MCI/AD is unclear. A recent study has shown that individuals in early MCI experienced a greater increase in gait speed variability compared to cognitively normal individuals, suggesting a period of functional reserve compensating early neuropathology.9 Whether this longitudinal increase in gait variability can be observed before the onset of clinical symptom is unknown.

Although it is unclear whether lap time variability reflects gait variability or another construct, such as gait automaticity, lap time variability may be an important mobility marker and predictor of brain health, especially in executive function, and may be of great clinical relevance as it can be easily accessed in clinical settings without the need for gait mats or other high-tech equipment. Since it has been proposed that interventions aimed at preventing cognitive impairment and AD are probably most effective when administered early in the asymptomatic, preclinical phase of AD, the availability of simple behavioral markers of increased risk of MCI/AD can help target individuals most likely to respond to preventive treatments.

In this case-control study, we used pre-diagnosis longitudinal data to identify individuals who ultimately were diagnosed with MCI or AD and compared them with controls matched for sex, age at the beginning and the end of the observation period, which for the cases corresponded to the time at the onset of clinical symptom. We evaluated the longitudinal trajectory of lap time variability across the ten 40-meter laps of the 400-meter walk test.7 We further tested the hypothesis that differences in the trajectory of lap time variability between the two groups are not accounted for by other early behavioral markers including initial cognitive function, gait speed, and rate of gait slowing over time. In order to examine the relationship between lap time variability and step-to-step variability, we further report the cross-sectional relationship between lap time variability and step-to-step gait variability in participants with available data from the greater sample available in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA).

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This study is a case-control retrospective study embedded in a large longitudinal cohort study, the BLSA. The BLSA is a continuous enrollment, population-based study that began in 1958. The frequency of study visits depends on age; every four years for those younger than 60, every two years for those aged between 60 and 79, and annually for those aged 80 and older. Because participants are scheduled to return at different intervals depending on their age, the follow-up time varies and their age at the initial assessment of lap time variability as well as the most recent visit also vary. A case-control design was used to match variables affecting lap time variability, such as age and follow-up intervals.

The 400-meter walk test was introduced in April 2007. Among those who completed the 400-meter walk test, 67 cases with MCI (n=35) and AD (n=32) had 400-meter walk test data prior to the onset of clinical symptoms. Cognitively normal controls were matched 2 to 1 to cases, based on sex, age at case symptom onset (within 5 years, average=0 years), age (within 5 years, average=0 years) at the initial assessment of the 400-meter walk test, as well as the follow-up interval between the initial assessment of the 400-meter walk and the onset of clinical symptoms. Controls had lap time variability measured on a minimum of two separate visits.

At each assessment, participants provided written informed consent. The BLSA protocol was approved by the relevant Institutional Review Board.

Diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease

Clinical and neuropsychological data from BLSA participants were reviewed at a consensus conference if participants screened positive on the Blessed Information Memory Concentration score10 (i.e. score ≥4), if their Clinical Dementia Rating score was ≥0.5 using subject or informant report,11 or if concerns were raised about their cognitive status. In addition, all participants were evaluated by case conference upon death or withdrawal. Diagnoses of dementia and AD were based on DSM-III-R12 and the National Institute of Neurological and Communication Disorders and Stroke —Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria13, respectively. MCI was based on the Petersen criteria14 and diagnosed when (1) cognitive impairment was evident for a single domain (typically memory) or (2) cognitive impairment in multiple domains occurred without significant functional loss in activities of daily living. Date of symptom onset was estimated for MCI/AD and was synonymous with the date of onset of MCI.

Lap time variability and mobility measures

Lap time variability is derived from the 400-meter walk test. Details of the 400-meter walk test are described previously.15 In brief, participants are instructed to walk for ten 40-meter laps continuously as quickly as possible, without running. At the end of each lap, they receive verbal feedback and encouragement from the examiner, and lap time is recorded using a stopwatch. Among those who successfully completed the 400-meter test, lap time variability was computed as standard deviation of residuals.6 Because participants walked continuously for ten laps, an increasing trend of lap time may exist due to fatigue-related slowing. Therefore, lap time variability was obtained as “detrended” standard deviation, or in other terms by eliminating from the calculation of variability the progressive slowing down that may be due to fatigue. First, individual trajectories of lap time across ten laps were computed using a participant-specific linear regression. Second, residual from each lap was computed as the vertical distance between observed and predicted lap time based on individual trajectories. Finally, the standard deviation of residuals (i.e. lap time variability) was obtained across ten laps.

Gait speed measures at baseline were considered as covariates, including fast gait speed over the 400-meter walk, 6-meter usual gait speed, and 6-meter rapid gait speed. We also examined the contribution of gait slowing in the same period of time as lap time variability. The change in gait speed at each visit was computed as a relative change to the baseline gait speed value and was examined as a time-varying covariate.

Cognitive measures

Executive function and memory are domains of interest because they are known to be associated with gait and mobility. Executive function was measured using delta TMT, the difference between Trail Making Test part B and part A.16,17 Delta TMT is considered a more accurate measure of executive function than Trail Making Test part B alone, because it controls for the speed component in part A. Verbal memory was measured using the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT).18 The CVLT immediate recall score was used in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of cases and controls were compared using independent t-tests or chi-square tests as appropriate. We first compared the trajectories of lap time variability between cases and controls using mixed effects linear regression, including a “group * interval” interaction term, where the interval was calculated as the time in years between the initial assessment of 400-meter walk and each follow up visit. The significance of this interaction term reflected whether the rate of change in lap time variability over time differed between cases and controls. We also tested for non-linearity by adding an “interval * interval” term. The interval square term was dropped from the model if it was not significant.

To examine the contributions of baseline gait speed and cognition to this relationship, models were adjusted for baseline fast gait speed over 400 meters, 6-meter usual gait speed, 6-meter rapid gait speed, TMT part B, delta TMT, and CVLT immediate recall score one at a time. Baseline covariates and interaction terms between baseline covariates and interval were included in the model.

To examine the contribution of gait slowing to this relationship, models were further adjusted for changes in gait speed, including fast gait speed over 400 meters, 6-meter usual gait speed, and 6-meter rapid gait speed. Baseline gait speed was also included in the model.

We further tested the strength of the association by adjusting for sample demographics (i.e. race) that, despite the matching, remained different between cases and controls at baseline. We performed sensitivity analyses limited to the 53 cases who had lap time variability measured on at least two separate visits during the preclinical phase and their matched controls (n=106).

We also examined the cross-sectional association between lap time variability and step-to-step gait variability obtained from a 3D motion system19 in 597 participants with available data in the BLSA. The association was examined using partial correlation analysis, after controlling for age, sex, height, body mass index, and mean gait speed.

To obtain an optimal cut-off value of lap time variability trajectory, we performed ROC analyses. The corresponding sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were also reported.

Results

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. At baseline, an average of 5 years prior to symptom onset or equivalent in the controls, there were no significant differences in age, sex, body mass index, and years of education between MCI/AD cases and matched controls (Table 1). Compared to controls, cases were more likely to be black (Table 1). At baseline, cases had slower gait speed over 400 meters, slower usual and rapid gait speeds over 6 meters, and poorer CVLT scores than controls. Cases and controls did not differ in baseline lap time variability or delta TMT performance. There was no difference between cases and controls in average follow-up time, although the mean number of visits was lower in cases compared to controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline sample characteristics

| Mild cognitive impairment/Alzheimer’s disease (n=67) |

Age- and sex- matched controls (n=134) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean [SD] or No. (%) | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 79.3 [6.3] | 79.3 [6.2] | 0.999 |

| Women | 31 (46) | 62 (46) | 0.999 |

| Black | 17 (25) | 14 (10) | 0.012* |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.9 [3.9] | 25.7 [3.3] | 0.728 |

| Education, years | 17 [3] | 17 [3] | 0.890 |

| Average number of visits | 3 [2] | 4 [2] | <0.001* |

| Average years of follow-up † | 5.3 [2.4] | 5.2 [2.4] | 0.775 |

| Age at symptom onset ‡ | 84.6 [6.3] | 84.5 [6.1] | 0.911 |

| Lap time variation, sec | 0.933 [0.428] | 0.843 [0.391] | 0.135 |

| Covariates | |||

| Fast gait speed over 400m, m/sec | 1.33 [0.25] | 1.43 [0.21] | 0.003* |

| 6-meter usual gait speed, m/sec | 1.02 [0.20] | 1.09 [0.18] | 0.013* |

| 6-meter rapid gait speed, m/sec | 1.52 [0.34] | 1.66 [0.29] | 0.003* |

| Delta TMT, sec | 66.7 [37.5] | 59.0 [44.3] | 0.227 |

| CVLT immediate recall | 44.2 [13.2] | 48.6 [12.2] | 0.021* |

Footnote:

p<0.05.

from the initial assessment of 400m to the time of symptom onset for cases and to the most recent visit for controls.

age at the most recent visit for controls.

TMT=Trail Making Test. CVLT=California Verbal Learning Test.

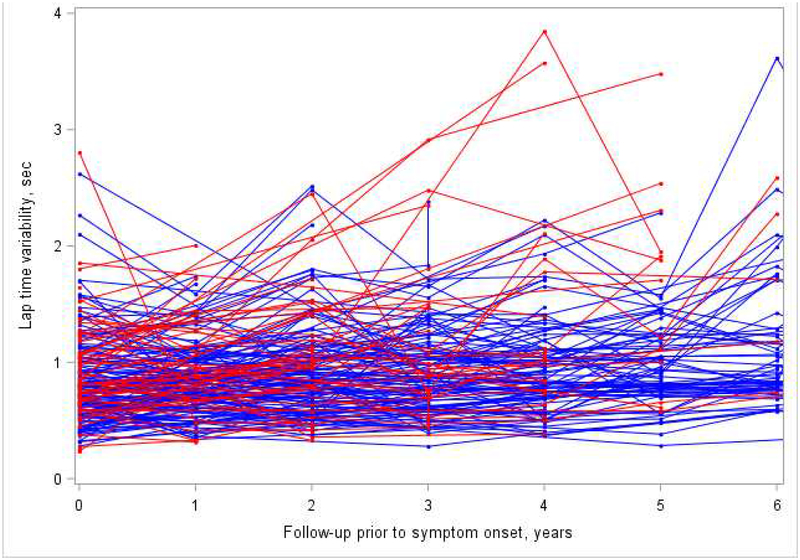

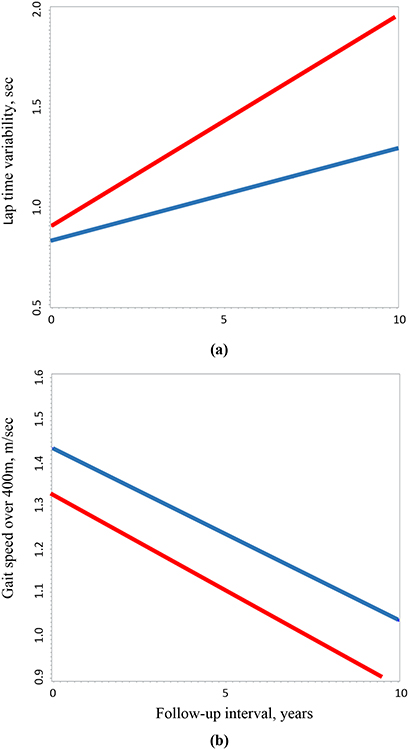

Prior to symptom onset, compared to controls, MCI/AD cases had an annual 0.059 m/sec greater rate of increase in lap time variability (Table 2, Model 1; Appendix Figure A1). Databased group average trajectories of lap time variability in cases and controls were shown in Figure 1a. This association remained significant after adjustment for baseline gait speed from the 400-meter walk (Table 2), 6-meter usual gait speed, 6-meter rapid gait speed, TMT part B, delta TMT performance, or CVLT scores (Table A1, Models 2–6). The interval * interval term to test for nonlinearity was not significant and was dropped from the model.

Table 2.

The longitudinal association of lap time variation over time with MCI/AD

| Model 1: Unadjusted | Model 2: Model 1+ fast gait speed over 400m walk | Model 3: Model 2+ Δ fast gait speed over 400m walk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case-control | 0.075 (−0.034, 0.184) 0.176 |

0.022 (−0.080, 0.123) 0.676 |

−0.009 (−0.112, 0.094) 0.864 |

| Case-control*interval | 0.059 (0.015, 0.103) 0.009* |

0.042 (0.0001, 0.084) 0.049* |

0.046 (0.008, 0.084) 0.018* |

| Fast gait speed over 400m, sec | - | −0.645 (−0.850, −0.440) <0.001* |

−0.680 (−0.887, −0.473) <0.001* |

| Fast gait speed*interval | - | −0.161 (−0.237, −0.086) <0.001* |

−0.877 (−1.355, −0.400) <0.001* |

| Δ in fast gait speed over 400m walk | - | - | −0.877 (−1.355, −0.400) <0.001* |

| Δ in fast gait speed*interval | - | - | −0.105 (−0.189, −0.021) 0.014* |

Footnote:

p<0.05.

Figure 1. Trajectories of lap time variability (a) and fast gait speed over 400m (b) in cases (red) prior to symptom onset and controls (blue).

data-based group average trajectories of lap time variability (A) and gait speed over 400m (B) in cases prior to symptom onset and controls using linear mixed effects models.

Compared to controls, MCI/AD cases had persistently slower gait speed over 400-meter walk during the preclinical phase (β=−0.106, p=0.002), but the rate of change did not differ between groups (β=−0.006, p=0.249). Data-based group average trajectories of gait speed over 400m walk in cases and controls were shown in Figure 1b. The interval * interval square term was significant and was retained in the model, indicating that gait speed declined in a non-linear fashion.

We further adjusted for changes in gait speed. The association between change in lap time variability and MCI/AD remained significant including after adjustments for changes in fast gait speed over 400m walk (Table 2), in 6-meter usual gait speed, and in 6-meter rapid gait speed (Appendix Table A2, Models 2–3). Results remained similar limited to cases with at least two visits during the preclinical phase and their matched controls (Appendix Table A3–A4). Adjustment for race did not substantially alter these associations (data not shown).

In those with available data on lap time variability and step-to-step gait variability in the BLSA, higher lap time variability was associated with higher levels of stride length variability (r=0.133, p=0.001), step length variability (r=0.100, p=0.015), and stride time variability (r=0.091, p=0.027).

The optimal cut-off value for annual change in lap time variability was 0.4 seconds. Its corresponding sensitivity was 75% and specificity was 52%. The positive predictive value was 43% and negative predictive value was 80%.

Discussion

The rate of increase in lap time variability is steeper in persons who subsequently develop MCI/AD than in matched controls who remain cognitively normal, and the effect is independent of initial gait speed and cognition and is also independent of gait slowing over time. Change in lap time variability may provide additional predictive value beyond gait slowing or other behavioral markers of future MCI/AD risk. We note that our study sample was drawn from a population-based study. Findings need to be replicated in clinical studies and we expect that findings of positive predictive value and negative predictive value may be stronger in clinical populations. Prior research demonstrating increased gait speed variability in patients with early MCI supports this notion.9 It has been postulated that interventions aimed at preventing or slowing down the clinical course of MCI/AD are likely to be most effective in the preclinical phase. Given that lap time variability is a simple and inexpensive measure that can be obtained clinically with a stopwatch and 20-meter walking path, it can be administered during routine clinical practice over time. It might be used as a first-line screening tool to identify individuals at risk for future MCI/AD, or possibly for new clinical trials of preventive therapy. This approachis most effective when repeated measures are obtained in the same individuals. To the best of our knowledge, this study provides the first empirical evidence that the rate of change in gait variability, independent of preclinical gait speed, cognition or rate of gait slowing, differentiates older adults with future MCI/AD from cognitively normal older adults.

This study extends prior research by examining the longitudinal change in gait variability during the preclinical phase, by applying a clinically accessible measure of lap time variability from the 400-meter walk test, and by examining the contribution of the initial gait speed, cognition and gait slowing over time. In addition, we confirm that lap time variability is associated with more common indicators of step-to-step gait variability.

Our longitudinal findings during the preclinical phase are consistent with the hypothesis that gait speed shows wide fluctuations in early MCI.9 Dodge et al. reported differing trajectories of in-home gait speed variability over 3 years in patients with adjudicated MCI versus cognitively normal older adults. Those with MCI were more likely to have trajectories with an initial increase in gait speed variability followed by a decrease or with a continuous decrease in gait variability. The mechanism underlying increased fluctuations in performance during the preclinical or early symptomatic phase of a disease may be explained by compensatory processes.1 Increased fluctuations may represent a phase where functional reserve attempts to compensate for initial deficits or dysfunction. Fluctuations decrease when functional reserve fails to compensate. Our findings also show that the steeper increase in lap time variability in cases compared to controls was not accounted for by concurrent gait slowing. A non-linear pattern of gait speed decline is consistent with prior findings. Our findings suggest that trajectories of lap time variability may provide additional predictive value for MCI/AD beyond gait slowing.

Our study has novel aspects. We focused on a well-functioning sample during the preclinical phase of AD. Despite this, we demonstrated that gait variability increased on average 5 years prior to symptom onset in individuals with subsequent impairment. The adjudication of MCI/AD was rigorously established during the clinical conference using criteria widely validated. Controls are well matched to the age of onset. We used a performance-based measure of lap time variability from the 400-meter walk, which is feasible in clinical settings compared to gait variability assessed in a gait lab or with special equipment. We show that the association between gait variability and MCI/AD is not affected by initial gait speed or gait slowing. We demonstrate that the longitudinal rate of increase in gait variability distinguishes individuals who eventually develop MCI/ID even after accounting for the parallel decline in walking speed.

This study has limitations. The number of cases of MCI/AD is modest. Participants in the BLSA tend to be healthier and have more education and higher socioeconomic status than the general population. The average number of visits was slightly higher in controls compared to cases, although the interval between the initial assessment and symptom onset did not differ. Because a few MCI/AD cases had only one assessment of lap time variability prior to onset, the relationship between the rate of change in lap time variability and MCI/AD may have been underestimated. Nonetheless, results remained largely unchanged when limited to cases with at least two visits and their matched controls. We did not compare trajectories of gait variability between MCI/AD and non-AD dementia due to an insufficient sample size of non-AD dementia. We were not able to test longitudinal trajectories of step-to-step gait variability in relation to MCI/AD due to limited longitudinal data. Future studies are needed to examine longitudinal trajectories of step-to-step gait variability in relation to future MCI/AD. Future studies are also needed to compare the predictive value of gait variability, gait speed, and dual-task cost to MCI/AD.

Conclusion/Implications

The rate of increase in lap time variability, derived from the clinically accessible 400-meter walk, differentiates future MCI/AD compared to matched cognitively normal controls and is independent of other behavioral markers. Assessing lap time variability longitudinally may help to identify individuals identify individuals at risk for future MCI/AD, or possibly for new clinical trials of preventive therapy.

Acknowledgments:

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. Grant number: 03-AG-0325.

Figure A1. Observed lap time variability in cases (red) prior to symptom onset and controls (blue).

Table A1.

The longitudinal association of lap time variation over time with MCI/AD with adjustment for baseline covariates of interest

| Model 1: Unadjusted | Model 2: Model 1+ usual gait speed | Model 3: Model 1+ rapid gait speed | Model 4: Model1 +TMT part B | Model 5: Model 1+ TMT | Model 6: Model 1+ CVLT immediate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI), p-value | ||||||

| Case-control | 0.075 (−0.034, 0.184) 0.176 |

0.063 (−0.046, 0.173) 0.256 |

0.059 (−0.051, 0.169) 0.289 |

0.066 (−0.043, 0.175) 0.234 |

0.057 (−0.053, 0.166) 0.308 |

0.066 (−0.044, 0.176) 0.239 |

| Case-control*interval | 0.059 (0.015, 0.103) 0.009* |

0.049 (0.006, 0.092) 0.026* |

0.048 (0.005, 0.091) 0.029* |

0.057 (0.013, 0.102) 0.011* |

0.061 (0.016, 0.106) 0.008* |

0.059 (0.014, 0.103) 0.010* |

| Usual gait speed, m/s | - | −0.216 (−0.475, 0.042) 0.101* |

- | - | - | - |

| Usual gait speed*interval | - | −0.152 (−0.240, −0.063) <0.001* |

- | - | - | - |

| Rapid gait speed, m/s | - | - | −0.131 (−0.291, 0.030) 0.110 |

- | - | - |

| Rapid gait speed*interval | - | - | −0.100 (−0.157, −0.043) <0.001* |

- | - | - |

| TMT-B, sec | - | - | - | 0.001 (−0.000, 0.002) 0.128 |

- | - |

| TMT-B*interval | - | - | - | 0.000 (−0.000, 0.001) 0.302 |

- | - |

| Delta TMT, sec | - | - | - | - | 0.000 (−0.0007, 0.002) 0.438 |

- |

| TMT*interval | - | - | - | - | 0.000 (−0.0003, 0.001) 0.530 |

- |

| CVLT immediate recall | - | - | - | - | - | −0.002 (−0.006, 0.002) 0.324 |

| CVLT*interval | - | - | - | - | - | −0.001 (−0.002, 0.001) 0.362 |

Footnote:

p<0.05.

Table A2.

The longitudinal association of lap time variation over time with MCI/AD with further adjustment for gait slowing

| Model 1: Unadjusted | Model 2: Model 1+ Δ in usual gait speed | Model 3: Model 1+ Δ in rapid gait speed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case-control | 0.075 (−0.034, 0.184) 0.176 |

0.043 (−0.067, 0.153) 0.440 |

0.048 (−0.063, 0.159) 0.393 |

| Case-control*interval | 0.059 (0.015, 0.103) 0.009* |

0.044 (0.005, 0.084) 0.029* |

0.047 (0.004, 0.090) 0.031* |

| Δ in usual gait speed | - | −0.338 (−0.722, 0.045) 0.084 |

- |

| Δ in usual gait speed*interval | - | −0.107 (−0.201, −0.014) 0.024* |

- |

| Δ in rapid gait speed | - | - | −0.102 (−0.393, 0.190) 0.493 |

| Δ in rapid gait speed*interval | - | - | −0.043 (−0.114, 0.027) 0.230 |

Footnote:

p<0.05.

In Model 2 and Model 3, baseline gait speed and baseline gait speed*interval were included (not shown).

Table A3.

Baseline sample characteristics in cases with at least 2 visits and their matched controls

| Mild cognitive impairment/Alzheimer’s disease (n=53) |

Age- and sex- matched controls (n=106) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean [SD] or No. (%) | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 79.4 [6.0] | 79.5 [5.9] | 0.955 |

| Women | 24 (45) | 58 (45) | 0.999 |

| Black | 10 (19) | 11 (10) | 0.144 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.9 [3.9] | 25.7 [3.3] | 0.655 |

| Education, years | 17 [4] | 17 [3] | 0.418 |

| Average number of visits | 3.6 [1.4] | 4.5 [1.8] | <0.001* |

| Average years of follow-up † | 5.8 [2.2] | 5.6 [2.4] | 0.681 |

| Age at onset ‡ | 85.2 [5.7] | 85.1 [5.5] | 0.912 |

| Lap time variation, sec | 0.945 [0.444] | 0.846 [0.404] | 0.161 |

| Covariates | |||

| Fast gait speed over 400m, m/sec | 1.34 [0.26] | 1.43 [0.20] | 0.024* |

| 6-meter usual gait speed, m/sec | 1.03 [0.21] | 1.08 [0.19] | 0.150 |

| 6-meter rapid gait speed, m/sec | 1.55 [0.36] | 1.65 [0.28] | 0.059 |

| Delta TMT, sec | 63.8 [31.6] | 61.7 [46.3] | 0.735 |

| CVLT immediate recall | 44.8 [13.2] | 48.3 [12.4] | 0.102 |

Footnote:

p<0.05.

from the initial assessment of 400m to the time of symptom onset for cases and to the most recent visit for controls.

age at the most recent visit for controls.

TMT=Trail Making Test. CVLT=California Verbal Learning Test.

Table A4.

The longitudinal association of long-term lap time variation with MCI/AD with adjustment for baseline gait speed and change in gait speed in cases with at least 2 visits and their matched controls

| Model 1: Unadjusted model | Model 2: Model 1+ baseline fast gait speed over 400m | Model 3: Model 2 + A in fast gait speed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case-control | 0.075 (−0.049, 0.198) 0.233 |

0.026 (−0.091, 0.142) 0.665 |

−0.004 (−0.121, 0.114) 0.952 |

| Case-control*interval |

0.062 (0.017, 0.108) 0.008* |

0.043 (−0.000, 0.086) 0.051 |

0.044 (0.004, 0.084) 0.030* |

| Baseline fast gait speed | −0.621 (−0.859, −0.383) <0.001* |

−0.661 (−0.903, −0.419) <0.001* |

|

| Fast gait speed*interval | −0.174 (−0.254, −0.095) <0.001* |

−0.151 (−0.221, −0.080) <0.001* |

|

| Δ fast gait speed | −0.808 (−1.326, −0.290) 0.002* |

||

| Δ fast gait speed*interval | −0.099 (−0.194, −0.004) 0.041* |

Footnote:

p<0.05.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References:

- 1.MacDonald SW, Nyberg L, Backman L. Intra-individual variability in behavior: links to brain structure, neurotransmission and neuronal activity. Trends in neurosciences. 2006;29(8):474–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams BR, Hultsch DF, Strauss EH, et al. Inconsistency in reaction time across the life span. Neuropsychology. 2005;19(1):88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tian Q, Ferrucci L, Resnick SM, et al. The effect of age and microstructural white matter integrity on lap time variation and fast-paced walking speed. Brain imaging and behavior. 2016;10(3):697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian Q, Resnick SM, Ferrucci L, Studenski SA. Intra-individual lap time variation of the 400-m walk, an early mobility indicator of executive function decline in high-functioning older adults? Age. 2015;37(6):115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tian Q, Resnick SM, Landman BA, et al. Lower gray matter integrity is associated with greater lap time variation in high-functioning older adults. Experimental gerontology. 2016;77:46–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tian Q, Simonsick EM, Resnick SM, et al. Lap time variation and executive function in older adults: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Age and ageing. 2015;44(5):796–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vestergaard S, Patel KV, Bandinelli S, et al. Characteristics of 400-meter walk test performance and subsequent mortality in older adults. Rejuvenation research. 2009;12(3):177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tian Q, Chastan N, Bair WN, et al. The brain map of gait variability in aging, cognitive impairment and dementia-A systematic review. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2017;74(Pt A):149–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dodge HH, Mattek NC, Austin D, et al. In-home walking speeds and variability trajectories associated with mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2012;78(24):1946–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuld PA. Psychological testing in the differential diagnosis of the dementias. Alzheimer’s disease: senile dementia and related disorders. 1978;7:185–193. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. Fourth Edition ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Archives of neurology. 1999;56(3):303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simonsick EM, Montgomery PS, Newman AB, et al. Measuring fitness in healthy older adults: the Health ABC Long Distance Corridor Walk. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49(11):1544–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corrigan JD, Hinkeldey NS. Relationships between parts A and B of the Trail Making Test. Journal of clinical psychology. 1987;43(4):402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.M.D. L. Neuropsychological Assessment. 3rd Ed ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delis D, Kramer J, Kaplan E, Ober B. California Verbal Learning Test. Research edition ed. New York, NY: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian Q, Bair WN, Resnick SM, et al. beta-amyloid deposition is associated with gait variability in usual aging. Gait & posture. 2018;61:346–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]