Abstract

Aim

The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether pharmacologic treatments or genotypes shown to prolong murine lifespan ameliorate the severity of age-associated osteoarthritis.

Materials and Methods

Male UM-HET3 mice were fed diets containing 17-α-estradiol, acarbose, nordihydroguaiaretic acid, or control diet per the National Institute on Aging Interventions Testing Program (ITP) protocol. Findings were compared to genetically long-lived male Ames dwarf mice. Stifles were analyzed histologically with articular cartilage structure (ACS) and safranin O scoring as well as with quantitative histomorphometry.

Results

Depending on the experimental group, ITP mice were between 450–1150 days old at the time of necropsy and 12–15 animals were studied per group. Two age groups (450 and 750 days) with 16–20 animals per group were used for Ames dwarf studies. No differences were found in the ACS or safranin O scores between treatment and control groups in the ITP study. There was high variability in most of the histologic outcome measures. For example, the older UM-HET3 controls had ACS scores of 6.1±5.8 (mean±SD) and Saf O scores of 6.8± 5.6. Nevertheless, 17-α-estradiol mice had larger areas and widths of subchondral bone compared to controls, and dwarf mice had less subchondral bone area and width and less articular cartilage necrosis than non-dwarf controls.

Conclusions

UM-HET3 mice developed age-related OA but with a high degree of variability and without a significant effect of the tested ITP treatments. High variability was also seen in the Ames dwarf mice but differences in several measures suggested some protection from OA.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, healthspan, lifespan, aging, cartilage

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA), a disease of the synovial joints, is an important cause of disability worldwide and its prevalence increases with age 1;2;3. Modern therapies palliate symptoms of OA, but treatments that alter the natural history of the disease are lacking 4. Due to the lack of interventions that alter the disease process and the increasing prevalence of OA, the incidence of joint arthroplasty is rising in the United States 5;6. However, prosthetic joints have associated concerns including the requirement for surgery, limited longevity, and a risk of devastating complications 7;8. Thus, treatments that stop or delay the progression of OA are desperately needed. Given the close association and shared mechanisms between aging and the development of OA, interventions that target aging pathways could potentially benefit OA as well.

The Interventions Testing Program (ITP) is a multi-site collaborative project funded by the National Institute on Aging, the goal of which is identifying compounds that promote healthy aging and thereby extend lifespan in a genetically heterogeneous mouse model 13. Stage I of the ITP program uses age as the primary outcome in order to screen a large number of compounds that could potentially increase longevity. Stage II of the ITP utilizes the compounds from stage I that extended longevity but investigates further whether these compounds also delay the global process of aging at the end organ level and, if so, their underlying biological effects.

Acarbose, nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA), and 17-α-estradiol extended median lifespan by 8–22%, depending on the test agent, dose, and testing site, in genetically heterogeneous male mice evaluated in stage I of the ITP 14;15. Acarbose, an intestinal α-glucosidase inhibitor, is FDA-approved to treat diabetes and acts by inhibiting digestion of complex carbohydrates to reduce postprandial hyperglycemia. It is considered to be a potential dietary restriction mimetic. NDGA is a botanical with lipoxygenase and antioxidant properties while 17-α-estradiol is an estrogenic compound with reduced affinity for estrogen receptors relative to its optical isomer, 17-β-estradiol 14;15.

Because OA is a disease in which incidence and associated disability increase with age, the presence and severity of OA is an important outcome when considering the efficacy of compounds that extend age by targeting pathways that may also contribute to the development of OA. Thus, the purpose of this study was to determine the severity of age-associated OA in genetically heterogeneous male mice and determine if the severity of age-associated OA was reduced in mice treated with selected agents in the ITP study that were found to increase life span. Findings were compared to Ames dwarf mice, which are deficient in growth hormone and are genetically long-lived16.

Methods

Animals

Stifles were collected from male UM-HET3 mice that had been in the ITP lifespan extension study at the University of Michigan site as previously described 17;18;19. Briefly, these animals were generated via a four-way cross using CByB6F1 mothers (JAX stock #100009) and C3D2F1 fathers (JAX stock #100004). Stock mice purchased from The Jackson Laboratory were bred at each of the three ITP sites over 6–8 months to minimize cohort effects. Stifles were obtained from mice fed diets containing acarbose (n=15), high dose NDGA (n=14), 17-α-estradiol (n=12), or a control diet (n=15 for acarbose and NDGA study, n=12 for 17- α-estradiol study). The number of mice per group was chosen based on the results from a study performed by our group using the same histologic outcome measures as the present study. That study used 12-month old and 22-month old wild type controls and mice with a deletion of the gene for the cytokine MIF that had been shown to increase longevity in male mice23. In that study, an n of 13–16 mice per group was sufficient to detect significant differences between the controls and MIF−/− mice.

Treatment diets started at 4 months of age with the exception of 17-α-estradiol, which started at 10 months of age to reduce the risk of isomerization to 17-β-estradiol, which has been reported to occur only in younger rodents 20. Mice were inspected daily, and death was recorded when animals either were found dead or were euthanized for humane reasons if they were considered to be so severely moribund that they were unlikely to survive another 48 hours. For the present study, stifles were provided from mice of similar ages in the intervention and control groups so that the effects of the interventions on the development of OA could be determined independent of age (Supplementary Table 1). The mean age of the mice at death was 1150 ± 89 (standard deviation, SD) days for the NDGA, acarbose, and age-matched control mice, and 950 ± 160 days for the 17-α-estradiol and their age-matched control mice. Another group of mice was treated with an intermediate dose of NDGA (n=15) or control diet (n=5) for a mean of 660 ± 7 days and then sacrificed. Finally, two groups of Ames Dwarf Mice, one that was sacrificed at a mean age of 450 ± 19 days (n=20) and one that was sacrificed at a mean age of 750 ± 45 days (n=16), were compared to age-matched sibling controls (n=22 and n=18, respectively). Stifles from these latter mice were kindly provided by Dr. Andrzej Bartke (Southern Illinois University, Springfield, IL).

Tissue Preparation

Intact knee (stifle) joints, one from each animal, were isolated by surgical dissection, fixed in 10% formalin with the joint angle at approximately 120 degrees, decalcified in 10% EDTA for three weeks, and processed for histology as previously described 12. Joints were embedded intact into paraffin with the patella down and the femur and tibia forming equal angles to the rim of the embedding cassette, ensuring that the joint was not rotated medially or laterally. The joints were then serially sectioned in the coronal plane using previously described anatomic landmarks and 4 to 5 representative midcoronal 4-μm-thick sections spanning approximately 100 μm were stained with hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) and Safranin O (Saf O) 12.

Histologic Analysis

Specimens were relabeled and randomized to ensure that the histological evaluations were done by observers blinded to group assignment. A single representative section from each stifle was chosen for analysis based on ideal alignment. The medial tibial plateau (MTP) was analyzed from each joint because this is the site that most frequently develops age-related OA 12. The lateral tibial plateau (LTP) was also evaluated in the acarbose, NDGA, and respective control mice; however, due to the fact that minimal lesions were present at this site, this analysis was not included for the other groups. Sections were evaluated by articular cartilage structure scoring (ACS) (range, 0–12) and safranin O scoring (Saf O) (range, 0–12) as previously described 21;12. Abaxially located osteophytes were semi-quantitatively assessed (0–3) in the acarbose, NDGA, and control mice for the MTP and the LTP as previously described 22;23; osteophyte formation was evaluated in the 17-α-estradiol and control mice in the MTP only. Synovitis was also semi-quantitatively evaluated (0–3) in the acarbose, NDGA, and control mice as previously described 24;23. Saf O scoring was not performed in the 17-α-estradiol mice and synovitis was not graded in 17-α-estradiol or dwarf mice given the lack of synovitis seen in any of the other groups of aging mice.

Areas and thicknesses of articular cartilage, calcified cartilage, and subchondral bone, chondrocyte number, and percent area of articular cartilage necrosis were measured using the OsteoMeasure bone histomorphometry system in all mice as previously described 21. Measurement of tissue area was performed at 20x magnification using a 600 μm x 800 μm grid centered on the tibial plateau. Articular cartilage area was defined as the area between the superficial surface of articular cartilage and the most superficial tidemark; calcified cartilage area was the area between the most superficial tidemark and the calcified cartilage-subchondral bone junction; and subchondral bone (SCB) area was the area between the calcified cartilage-subchondral bone junction and the most superficial boundary of the marrow spaces. Total area of cartilage necrosis was measured by tracing and summing all areas within which two or more chondrocytes were dead, as determined by visual assessment of loss of nuclear staining or a pyknotic nuclear morphology with H&E. Articular cartilage, calcified cartilage, and subchondral bone width and area were calculated from perimeter measurements. The percentage of articular cartilage necrosis was computed by dividing the area of necrosis by the total area of the articular cartilage. Additionally, abaxial osteophytes were measured histomorphometrically, as has been previously described, in both old and young dwarf mice and their respective controls 25.

Statistics

Data were collected in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and analyzed in SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY) and R. Treatment groups were initially analyzed relative to their age-matched controls with single-factor ANOVA or two-tailed T test depending on the number of groups compared. A p < 0.05 was considered significant in all analyses. For significant ANOVA results, Tukey’s honest significant difference test (alpha 0.05) was used for post-hoc analysis to determine significance between individual groups. These experiments were intended to be hypothesis generating; thus, the results were not corrected for multiple comparisons.

Results

Histologic changes of osteoarthritis in ITP and Ames Dwarf mice

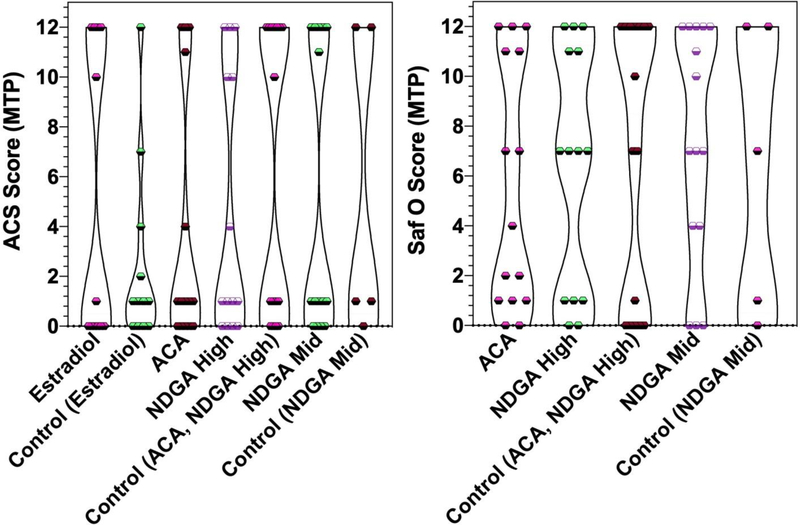

In the ITP mice (acarbose, NDGA, 17-α-estradiol and age-matched controls), animals within all groups were noted to have histologic signs of cartilage damage in the medial tibial plateaus (examples shown in Figure 1). When measured by ACS and Saf-O scoring, a wide range of scores was found and there were no significant differences among the controls and intervention groups (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 2).

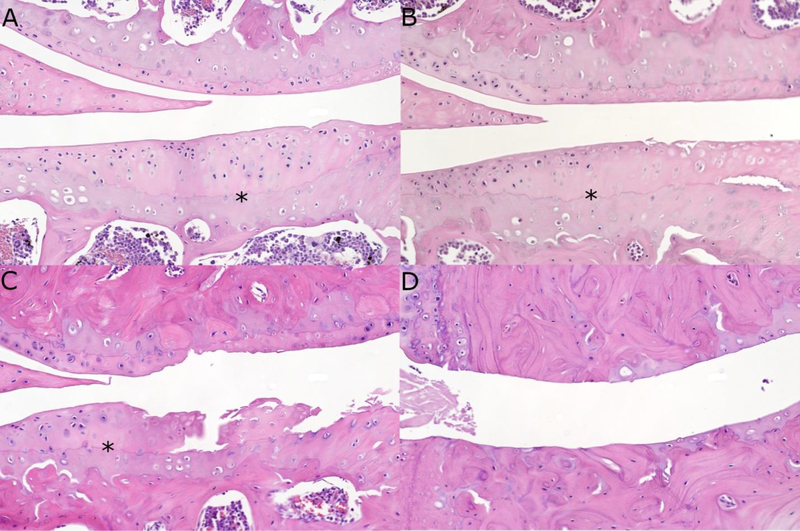

Figure 1: Examples of H&E histology representative of the spectrum of Articular Cartilage Structure (ACS) scores in the tibiae (lower half of each image) of Intervention Testing Program mice.

Black asterisks delineate the tidemark. A. Section from acarbose treatment group, age 1221 days, ACS score = 0. B. Section from acarbose treatment group, age 1216 days, ACS score = 4, despite a large clef superficial to the tidemark with necrotic overlying articular cartilage. C. Section from control group, age 1182 days, ACS score = 11. D. Section from middle dose NDGA group, age 659 days, ACS score = 12. Articular cartilage completely denuded from medial tibial plateau and medial femoral condyle with remnants of calcified cartilage overlying subchondral bone. NDGA, nordihydroguaiaretic acid.

Figure 2: Violin plot of Articular Cartilage Structure (ACS) scores (range 0–12) and Safranin O (Saf O) scores (range 0–12) for the Medial Tibial Plateau (MTP) by treatment group.

Results are shown as individual data points and violins with widths proportional to the probability of a given value in its respective group. Estradiol, 17-α-estradiol; ACA, acarbose; NDGA High, nordihydroguaiaretic acid high-dose; NDGA Mid, nordihydroguaiaretic acid middle-dose.

In the LTP, the incidence of OA changes was much lower than in the MTP. Only 1 animal, in the high-dose NDGA group, had an ACS score ≥6. Differences in ACS and Saf-O scores for the LTP were not significantly different between treatment and control groups (Supplementary Table 2).

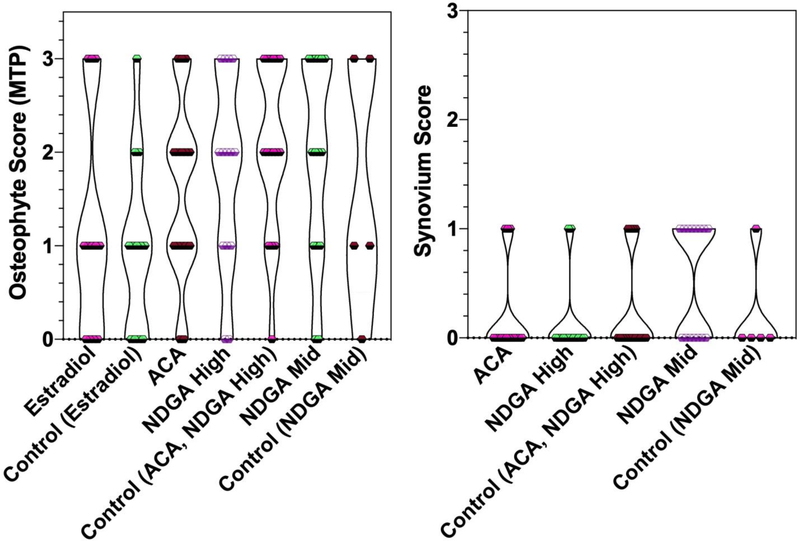

Osteophytes were detected but semi-quantitative osteophyte scoring did not reveal any significant differences in the MTP or the LTP of mice in the ITP study (Figure 3). There was little to no evidence of synovitis or synovial hyperplasia in these mice and no differences in semi-quantitative synovium scoring were observed among the groups (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Violin plot of osteophyte scores (range 0–3) for the Medial Tibial Plateau (MTP) and synovium scores (range 0–3) by treatment group.

Results are shown as individual data points and violins with widths proportional to the probability of a given value in its respective group. Estradiol, 17-α-estradiol; ACA, acarbose; NDGA High, nordihydroguaiaretic acid high-dose; NDGA Mid, nordihydroguaiaretic acid middle-dose.

The younger mice fed an intermediate-dose NDGA or control diet and sacrificed at a mean age of 660 days did not have significant differences in either the ACS or Saf O scores for either the MTP or the LTP (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 2). Further, because they were younger, they were compared to their older counterparts that were fed acarbose, high-dose NDGA, or control diet. ACS and Saf O scores were not significantly different between older and younger animals (data not shown). Differences in semi-quantitative osteophyte scores for the MTP and LTP or for synovium scores also were not statistically significant between these groups of animals (Figure 3).

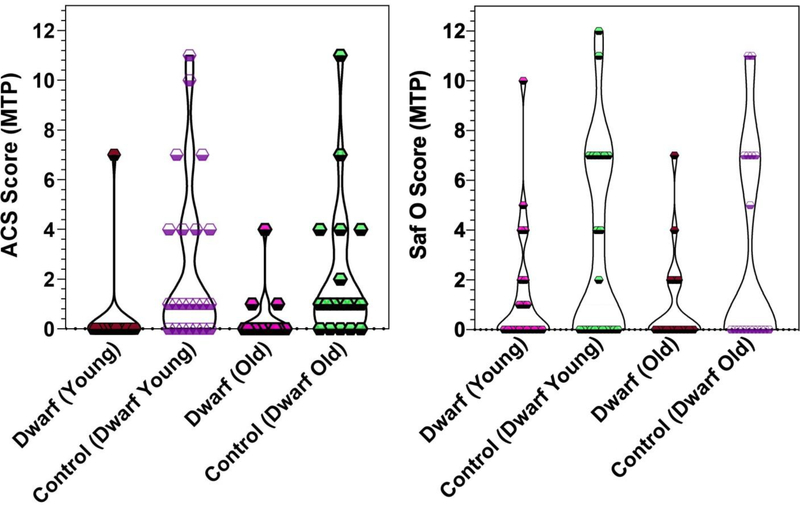

Compared to age-matched littermate controls, neither the older dwarf mice (average age 750 days) nor the younger dwarf mice (average age 450 days) exhibited significant differences in ACS scores or Saf O scores (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Violin plot of Articular Cartilage Structure (ACS) scores (range 0–12) and Safranin O (Saf O) scores (range 0–12) for the Medial Tibial Plateau (MTP) in dwarf mice of two ages and controls.

Results are shown as individual data points and violins with widths proportional to the probability of a given value in its respective group.

Histomorphometry

For the MTP, there were no significant differences in any of the histomorphometric variables measured between treatment (acarbose and NDGA) and control animals (Table 1). Although there was a trend towards benefit of treatment, the results were not statistically significant. The same was true for the LTP in these animals, except that generally no trend towards more or less severe OA was present at this site (data not shown). As noted for the ACS and Saf-O scores, there was very little histomorphometric evidence of OA in the LTP. The younger mice fed a diet of middle-dose of NDGA or control diet and sacrificed at a mean age of 660 days did not exhibit significant differences in either the MTP (Table 1) or LTP (data not shown) in any histomorphometric measurements.

Table 1.

Histomorphometry for Medial Tibial Plateau in mice fed ACA, high-dose NDGA, mid-dose NDGA, or control diet.

| Average Age = 1150 days | Average Age = 660 days | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ACA | NDGA Hi | P-Value | Control | NDGA Mid | P-Value | |

| N=16 | N=15 | N=14 | N=5 | N=15 | |||

| AC Area μ2 | |||||||

| Mean | 30453 | 49497 | 48750 | 0.226 | 31885 | 35266 | 0.999 |

| Std Dev | 28502 | 26828 | 28250 | 29376 | 27651 | ||

| AC Thickness μ | |||||||

| Mean | 28 | 45 | 45 | 0.184 | 30 | 33 | 0.998 |

| Std Dev | 24 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 24 | ||

| CC Area μ2 | |||||||

| Mean | 27362 | 39883 | 48750 | 0.253 | 31885 | 35266 | 0.986 |

| Std Dev | 28502 | 21482 | 28250 | 29376 | 27651 | ||

| CC Thickness μ | |||||||

| Mean | 28 | 31 | 36 | 0.256 | 35 | 37 | 0.997 |

| Std Dev | 13 | 15 | 12 | 14 | 13 | ||

| Chondrocyte # | |||||||

| Mean | 56 | 75 | 82 | 0.752 | 66 | 69 | 1.000 |

| Std Dev | 54 | 48 | 51 | 63 | 57 | ||

| SCB Area μ2 | |||||||

| Mean | 117326 | 97715 | 84037 | 0.218 | 164000 | 161000 | 0.937 |

| Std Dev | 52822 | 56559 | 44462 | 67351 | 65535 | ||

| SCB Thickness μ | |||||||

| Mean | 80 | 77 | 56 | 0.521 | 190 | 160 | 0.660 |

| Std Dev | 52.1 | 80.7 | 43.6 | 172.2 | 114.5 | ||

| Necrosis Area μ2 | |||||||

| Mean | 6912 | 11381 | 7764 | 0.339 | 5839 | 5382 | 0.872 |

| Std Dev | 7575 | 10665 | 7751 | 5579 | 5353 | ||

| % Necrosis | |||||||

| Mean | 49% | 45% | 27% | 0.331 | 29% | 40% | 0.559 |

| Std Dev | 37% | 57% | 25% | 16% | 38% | ||

AC, articular cartilage; CC, calcified cartilage; SCB, subchondral bone; ACA, acarbose; NDGA, nordihydroguaiaretic acid.

In the 17-α-estradiol experiment, histomorphometric variables were measured for the MTP only. Differences in articular and calcified cartilage were not statistically significant, however mean subchondral bone area and width in the 17-alpha-estradiol treated mice was larger than in the animals fed a control diet (Table 2).

Table 2.

Histomorphometry for Medial Tibial Plateau in mice fed 17-α-estradiol or control diet.

| Average Age = 950 days | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 17-α-Estradio | Control | P-Value | |

| AC Area μ2 | |||

| Mean | 32834 | 46431 | 0.136 |

| Std Dev | 25390 | 16819 | |

| AC Width μ | |||

| Mean | 42 | 60 | 0.134 |

| Std Dev | 33 | 22 | |

| CC Area μ2 | |||

| Mean | 588 | 771 | 0.188 |

| Std Dev | 397 | 244 | |

| CC Width2 | |||

| Mean | 737 | 1013 | 0.132 |

| Std Dev | 502 | 349 | |

| SCB Area μ2 | |||

| Mean | 102000 | 55623 | 0.033 |

| Std Dev | 61861 | 33593 | |

| SCB Width μ | |||

| Mean | 107.1 | 55.91 | 0.037 |

| Std Dev | 69.3 | 39.9 | |

AC, articular cartilage; CC, calcified cartilage; SCB, subchondral bone.

In dwarf mice and their controls, which were generally younger than the mice from the ITP study, there were few severe lesions in the articular cartilage (Figure 4). The youngest group of dwarves had a smaller AC area than age-matched controls, while in the older group, dwarves had increased AC width relative to controls (Table 3). Of note, the two stifles in the older mice and one in the younger mice that had severe changes were in control mice. Mean subchondral bone area was lower in the dwarf mice than controls in both age groups of mice (Table 3). In the 450-day-old group, the mean subchondral bone width was also lower in dwarf mice than controls. In both age groups, the percent of articular cartilage necrosis was lower in dwarf mice than controls, and in the younger group, the area of measured necrosis was lower in dwarf mice than controls. There was no significant difference in the histomorphometrically measured size of abaxial osteophytes between dwarf mice of either age and their respective controls (Table 3).

Table 3.

Histomorphometry for the Medial Tibial Plateau in dwarf mice and controls.

| Average Age = 450 days | Average Age = 750 days | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dwarf | Control | P-Value | Dwarf | Control | P-Value | |

| N=20 | N=22 | N=16 | N=18 | |||

| AC Area μ2 | ||||||

| Mean | 3330 | 4052 | 0.020 | 3624 | 3781 | 0.751 |

| Std Dev | 620 | 1218 | 704 | 1838 | ||

| AC Width μ | ||||||

| Mean | 56 | 49 | 0.088 | 60 | 46 | 0.040 |

| Std Dev | 11 | 15 | 12 | 22 | ||

| SCB Area μ2 | ||||||

| Mean | 4098 | 8084 | 0.001 | 3997 | 7527 | 0.047 |

| Std Dev | 1814 | 4607 | 1954 | 6757 | ||

| SCB Width u | ||||||

| Mean | 53.0 | 74.2 | 0.026 | 50.9 | 72.7 | 0.179 |

| Std Dev | 20.7 | 36.6 | 19.8 | 63.0 | ||

| % Necrosis | ||||||

| Mean | 6% | 23% | 0.002 | 13% | 30% | 0.032 |

| Std Dev | 7% | 21% | 14% | 28% | ||

| Necrosis Area μ2 | ||||||

| Mean | 226.4 | 754 | 0.0002 | 509.8 | 758.6 | 0.181 |

| Std Dev | 256.1 | 521 | 554.6 | 506.2 | ||

| Chondrocyte # | ||||||

| Mean | 106.2 | 92.86 | 0.118 | 99 | 79.39 | 0.114 |

| Std Dev | 18.58 | 33.59 | 26.97 | 40.96 | ||

| Osteophyte Area μ2 | ||||||

| Mean | 0 | 1528 | 0.063 | 0 | 470 | 0.146 |

| Std Dev | 0 | 3481 | 0 | 1259 | ||

AC, articular cartilage; SCB, subchondral bone.

Post-hoc power calculation and sample sizes

The observed variability in the results and the finding that very few of the measures, particularly those pertaining to the articular cartilage, were significantly different between treatment and control groups was not as expected. Utilizing our data, we performed a post-hoc power analysis to determine the number of mice required to detect a 50% effect size of the ITP treatments on the ACS and Saf O scores with an 80% power and an alpha of 5%. This revealed that 57 mice per group would be required for ACS scoring and 43 mice per group for Saf O scoring indicating that the current study was only powered to detect a very large effect of the interventions.

Discussion

Although acarbose, NDGA, and 17-α-estradiol extended the lifespan of genetically heterogeneous male mice in the ITP study 14, we failed to detect an effect of these interventions on the development of age-related OA changes in the knee assessed by a range of histological measures that evaluated the cartilage, subchondral bone, osteophytes and synovium. Unlike previous studies that have evaluated age-related OA using highly inbred strains of mice such as C57BL/6, the mice used in the ITP study were four-way cross offspring generated by crossing CByB6F1 and C3D2F1 mice, resulting in much greater genetic diversity. Similar to previous mouse studies of naturally occurring age-related OA, the male UM-HET3 mice developed typical cartilage lesions and osteophytes with additional changes in bone and cartilage histomorphometry that were not accompanied by significant changes in the synovium. Also similar to most previous studies in aging mice, the vast majority of lesions were located in the MTP with little or no involvement in the LTP. The variability in the various histologic measures reduced our ability to detect anything other than large effects of the interventions on OA severity.

Mice develop naturally occurring OA with age, but significant variability in disease severity and age of onset among mouse strains has been observed 22;23. STR/Ort mice, a well described murine model of spontaneous OA, show histologic signs of OA by 18 weeks of age and often have late-stage disease by 40 weeks of age 24. In contrast, CBA mice have little histologic evidence of OA by 40 weeks of age 24. Male STR/Ort mice have been reported to have more severe histologic changes than their similarly aged female counterparts 23. Male C57BL/6 mice also naturally develop OA with aging, manifested as increased articular cartilage chondrocyte cell death and decreased articular cartilage thickness at 23 months of age compared to 4.5 months of age 25.

Use of genetically heterogeneous mice, such as the UM-HET3 mice, for aging studies has many advantages over highly inbred strains of mice and many measures in other organ systems have been found to be less variable in these mice 26. Some of the OA measures such as the ACS score used in the present study gave dichotomous results such that mice either had moderately severe to severe lesions or very little to no disease. We observed trends towards protection from OA in ITP treatment groups in some measures but the differences in the frequency and severity of OA were not significant, indicating that the effects of the ITP interventions were not large. A significant difference in some of the histomorphometric measures and a trend towards a difference in several other measures were detected between the long-lived Ames dwarf mice and age-matched sibling controls, suggesting a partial protective effect of the Ames dwarf genotype on the development of OA. The mechanism of this protection warrants further investigation.

A study from our group reported the extent of histologic OA in 12-month old and 22-month-old MIF−/− mice and littermate controls on a (B6 × 129)F2 genetic background23. In that study, we detected significantly less OA in similarly sized experimental groups of mice as used in the present study. However, it should be noted that the effects of MIF deletion on OA severity were relatively large, with the 22-month old MIF −/− mice exhibiting ACS scores of 1±0.97 (mean ± SD) compared to 6.2±5.0 in the controls. The ACS scores in the controls used for the MIF study were actually quite close to the older UM-HET3 control mice used in the ACA and high-dose NDGA study that had ACS scores of 6.1 ±5.8. A study from another group examining the interleukin 6 knockout (IL6 KO) mouse, on the C57BL/6 background, demonstrated increased incidence of age-associated OA in the knockout mice, but only in the males 27. The number of mice in each group ranged from 24–39 in the male IL6 KO group and the mean age was 20 months. Together these studies suggest that the number of aged mice needed for OA studies, in particular when the effects of an intervention are not large, is higher than the numbers used for surgically-induced OA studies which commonly range from 6–15 mice per group. Given that genetics contributes to the risk of OA, it may be of interest in future studies to use the UM-HET3 mice in a genetic analysis to determine genes associated with OA severity.

We observed increased subchondral bone area and width in mice treated with 17-alpha-estradiol relative to controls. In OA, the subchondral bone has been demonstrated as having increased turnover and altered states of mineralization among multiple species, including rodents 28. It is possible that 17-alpha-estradiol, a non-feminizing estrogen-receptor-independent estrogen, has metabolic or biochemical effects on the subchondral bone with prolonged exposure.

Genetically long-lived Ames dwarf mice were distinguishable from their control counterparts by some histologic measures of OA. In addition to the Saf O scores, mean subchondral bone area was lower in the dwarf mice than controls in both age groups of mice. In the 450 day old group, the mean subchondral bone width was also lower in dwarf mice than controls. In both age groups, the percent of articular cartilage necrosis was lower in dwarf mice than controls and, in the younger group, the area of measured necrosis was lower in dwarf mice than controls. In other studies of OA in mice including surgically-induced OA, we have found cartilage necrosis to be a sensitive measure of OA severity.

Ames dwarf mice are physically quite different from control mice. They weigh 1/3 of their normal siblings, have reduced body proportions, and appear less active 29. Little is known about the changes in the synovial joints of Ames dwarfs, but a prior study of Snell dwarf mice showed less age-associated osteoarthritis compared to controls 30. In that study, mean age was 31 months in 43 dwarf mice and 25 months in 51 control mice. Similar differences in areas of cartilage necrosis and subchondral bone were observed in both males and females relative to non-dwarf controls. Osteoarthritis is well recognized to have multiple risk factors, including body weight. It is thus plausible that the small size of the dwarf animals contributed to the differences in some histologic measures independent of the biology behind their longevity.

In summary, the present study did not detect a significant effect of acarbose, NDGA, or 17-α-estradiol on the development of age-related OA in older mice, while some measures of OA severity were reduced in Ames dwarf mice relative to age-matched controls. Historically, histologic scoring and histomorphometry have most commonly been performed in younger mice relative to older mice or in mice with surgically-induced OA, both of which feature a more clear differentiation of disease states that allows analysis of therapies targeted at the underlying pathophysiology of OA development and progression. Should future investigators choose to pursue the effects of interventions on the histologic lesions present in age-associated OA in equivalently-aged and genetically heterogeneous mice, numbers of mice in the order of 50 or more per group or an intervention with a large effect on the severity of OA will be needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Andrzej Bartke from Southern Illinois University for mouse hindlimbs from Ames dwarf and age-matched control mice.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (RO1 AG044034 and U01 AG022303) as well as the Glenn Medical Foundation.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

No authors have competing interests.

References

- 1.Guccione AA, Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Anthony JM, Zhang Y, Wilson PW, Kelly-Hayes M, Wolf PA, Kreger BE, Kannel WB. The effects of specific medical conditions on the functional limitations of elders in the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health. 1994. 84(3):351–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felson DT, Zhang Y. An update on the epidemiology of knee and hip osteoarthritis with a view to prevention. Arthritis Rheum. 1998. 41(8):1343–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arden N, Nevitt MC. Osteoarthritis: epidemiology. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2006. 20(1):3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Hochberg MC, McAlindon T, Dieppe PA, Minor MA, Blair SN, Berman BM, Fries JF, Weinberger M, et al. Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 2: treatment approaches. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2000. 133(9):726–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of Primary and Revision Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone and Joint Surgery. 2007. 89(4):780–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernstein J, Derman P. Dramatic increase in total knee replacement utilization rates cannot be fully explained by a disproportionate increase among younger patients. Orthopedics. 2014. 37(7):e656–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callahan CM, Drake BG, Heck DA, Dittus RS. Patient outcomes following tricompartmental total knee replacement: A meta-analysis. J Am Medical Association. 1994. 271(17):1349–1357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gioe TJ, Killeen KK, Grimm K, Mehle S, Scheltema K. Why Are Total Knee Replacements Revised?: Analysis of Early Revision in a Community Knee Implant Registry. Clin Ortho Related Research. 2004. 428:100–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warner HR, Ingram D, Miller RA, Nadon NL, Richardson AG. 2000. Program for testing biological interventions to promote healthy aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2000. 115(3):199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison DE, Strong R, Allison DB, Ames BN, Astle CM, Atamna H, Fernandez E, Flurkey K, Javors MA, Nadon NL et al. Acarbose, 17-alpha-estradiol, and nordihydroguaiaretic acid extend mouse lifespan preferentially in males. Aging Cell. 2014. 13(2):273–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strong R, Miller RA, Antebi A, Astle CM, Bogue M, Denzel MS, Fernandez E, Flurkey K, Hamilton KL, Lamming DW et al. Longer lifespan in male mice treated with a weakly estrogenic agonist, an antioxidant, an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor or a Nrf2-inducer. Aging Cell. 2016. 15(5):872–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartke A, Brown-Borg H, Mattison J, Kinney B, Hauck S, Wright C. Prolonged longevity of hypopituitary dwarf mice. Experimental Gerontology. 2001. 36(1):21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strong R, Miller RA, Astle CM, Floyd RA, Flurkey K, Hensley KL, Javors MA, Leeuwenburgh C, Nelson JF, Ongini, et al. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid and aspirin increase lifespan of genetically heterogeneous male mice. Aging Cell. 2008. 7(5): 641–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K, Nadon NL, Wilkinson JE, Frenkel K, Carter, et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 2009. 460(7253): 392–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller RA, Harrison DE, Astle C, Baur JA, Boyd AR, De Cabo R, Fernandez E, Flurkey K, Javors MA, Nelson JF, et al. Rapamycin, but not resveratrol or simvastatin, extends life span of genetically heterogeneous mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011. 66A(2): 191–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajek RA, Robertson AD, Johnston DA, Van NT, Tcholakian RK, Wagner LA, Conti CJ, Meistrich ML, Contreras N, Edwards CL, et al. During development, 17alpha-estradiol is a potent estrogen and carcinogen. Environ Health Perspect. 1997. 105(Suppl 3): 577–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNulty MA, Loeser RF, Davey C, Callahan MF, Ferguson CM, Carlson CS. A Comprehensive Histological Assessment of Osteoarthritis Lesions in Mice. Cartilage. 2011. 2(4):354–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamekura S, Hoshi K, Shimoaka T, Chung U, Chikuda H, Yamada T, Uchida M, Ogata N, Seichi A, Nakamura K et al. Osteoarthritis development in novel experimental mouse models induced by knee joint instability. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2005. 13(7):632–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowe MA, Harper LR, McNulty MA, Lau AG, Carlson CS, Leng L, Bucala RJ, Miller RA, Loeser RF. Reduced Osteoarthritis Severity in Aged Mice With Deletion of Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017. 69(2):352–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krenn V, Morawietz L, Burmester GR, Kinne RW, Mueller-Ladner U, Muller B, Haupl T. Synovitis score: discrimination between chronic low-grade and high-grade synovitis. Histopathology. 2006. 49(4):358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson EJ, Lindgren BR, Carlson CS. Effects of long-term estrogen replacement therapy on bone turnover in periarticular tibial osteophytes in surgically postmenopausal cynomolgus monkeys. Bone. 2008. 42(5):907–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jay GE Jr., Sokoloff L Natural history of degenerative joint disease in small laboratory animals. II. Epiphyseal maturation and osteoarthritis of the knee of mice of inbred strains. AMA Archives Pathology. 1956. 62(2):129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walton M Degenerative joint disease in the mouse knee; histological observations. J Pathology. 1977. 123(2):109–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poulet B, Ulici V, Stone TC, Pead M, Gburcik V, Constantinou E, Palmer DB, Beier F, Timmons JA, Pitsillides AA. Time-series transcriptional profiling yields new perspectives on susceptibility to murine osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012. 64(10):3256–3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNulty MA, Loeser RF, Davey C, Callahan MF, Ferguson CM, Carlson CS. Histopathology of naturally occurring and surgically induced osteoarthritis in mice. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2012. 20(8):949–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phelan JP, Austad SN. Selecting animal models of human aging: inbred strains often exhibit less biological uniformity than F1 hybrids. Journal of Gerontology. 1994. 49(1):B1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Hooge ASK, van de Loo FAJ, Bennink MB, Arntz OJ, de Hooge P, van den Berg WB. Male IL-6 gene knock out mice developed more advanced osteoarthritis upon aging. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2005. 13(1):66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karsdal MA, Leeming DJ, Dam EB, Henriksen K, Alexandersen P, Pastoureau P, Altman RD, Christiansen C. Should subchondral bone turnover be targeted when treating osteoarthritis? Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2008. 16(6):638–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartke A The Molecular Genetics of Aging. Delayed aging in Ames dwarf mice Relationships to endocrine function and body size. Results and problems in cell differentiation. 2000. 29:181–202. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silberberg R Articular Aging and Osteoarthrosis in Dwarf Mice. Pathobiology. 1972. 38(6):417–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.