Abstract

Purpose:

An underlying cause of osteoarthritis (OA) is the inability of chondrocytes to maintain homeostasis in response to changing stress conditions. The purpose of this article was to review and experimentally evaluate oxidative stress resistance and resilience concepts in cartilage using glutathione redox homeostasis as an example. This framework may help identify novel approaches for promoting chondrocyte homeostasis during aging and obesity.

Materials and Methods:

Changes in glutathione content and redox ratio were evaluated in three models of chondrocyte stress: 1) age- and tissue-specific changes in joint tissues of 10 and 30-month old F344BN rats, including ex vivo patella culture experiments to evaluate N-acetylcysteine dependent resistance to an interleukin-1beta stress; 2) effect of different bout durations and patterns of cyclic compressive loading in bovine cartilage on glutathione stress resistance and resilience pathways; 3) time-dependent changes in GSH:GSSG in primary chondrocytes from wild-type and Sirt3 deficient mice challenged with the pro-oxidant menadione.

Results:

Glutathione was more abundant in cartilage than meniscus or infrapatellar fat pad, although cartilage was also more susceptible to age-related glutathione oxidation. Glutathione redox homeostasis was sensitive to the duration of compressive loading such that load-induced oxidation required unloaded periods to recover and increase total antioxidant capacity. Exposure to a pro-oxidant stress enhanced stress resistance by increasing glutathione content and GSH:GSSG ratio, especially in Sirt3 deficient cells. However, the rate of recovery, a marker of resilience, was delayed without Sirt3.

Conclusions:

OA-related models of cartilage stress reveal multiple mechanisms by which glutathione provides oxidative stress resistance and resilience.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, oxidative stress, glutathione, stress resistance, resilience, cartilage

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common musculoskeletal disease of synovial joints and a primary cause of disability worldwide (1). Painful knee OA in particular is associated with poorer health outcomes and an increased risk of early death (2). The likelihood of being diagnosed with symptomatic knee OA increases markedly with age, being greatest in adults between 55-64 years old (3). By 85 years of age, nearly 1 in 2 adults have symptomatic knee OA (4). Numerous factors increase this risk, such as gender (being female), a history of knee injury, and obesity (4). For example, obesity doubles the risk of developing symptomatic knee OA in individuals with a body mass index (BMI) >30 compared to those <25 (4). Despite these known risks, the underlying mechanisms that cause OA are incompletely understood, and there is no treatment to prevent the onset or progression of disease.

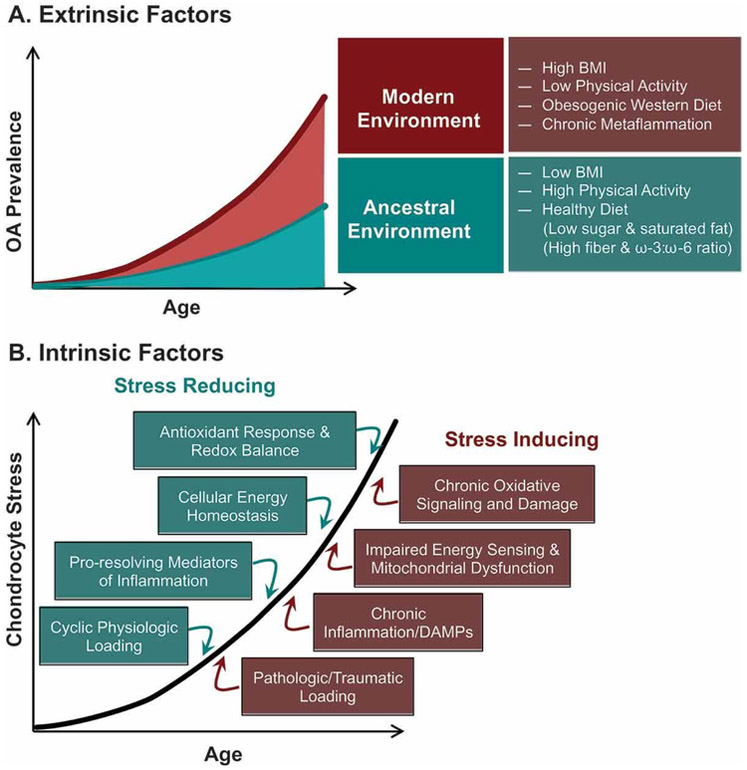

A better understanding of how aging interacts with these risk factors to increase the incidence of OA may provide clues for developing future disease-modifying therapies. For example, Wallace and colleagues showed that aspects of our modern environment and lifestyle, including but not solely obesity, provide substantial opportunities for reducing the prevalence knee OA in older adults. The investigators analyzed the skeletal remains of individuals who lived during the early and modern post-industrial era as well as archeological skeletons of prehistoric hunter-gatherers and early farmers for osteological evidence of knee OA (5). After statistically controlling for potential confounding variables, such as a higher occurrence of obesity and increased lifespan, the estimated prevalence of knee OA remained about 2-fold higher in post-industrial compared to pre-industrial era samples (Figure 1A) (5). This finding suggests that additional components of the modern environment beyond obesity and increased lifespan contribute to the current high risk of knee OA. In contrast to the modern post-industrial era, the lifestyle of prehistoric hunter-gathers and early farmers involved high levels of physical activity (6). The diets of pre-industrial populations were also relatively low in sugar and saturated fats and high in fiber and anti-inflammatory omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids compared to typical post-industrial Western diets (Figure 1A). Thus, from an evolutionary perspective, OA may be considered a ‘mismatch disease’ based on the apparent inability of genes inherited from prior populations to adequately adapt to the rapid changes in extrinsic environmental factors associated with OA pathogenesis, such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, dietary changes, and physical inactivity (7).

Figure 1. Extrinsic and intrinsic factors associated with increased risk of OA.

(A) Recent work by Wallace and colleagues (5) implicates numerous extrinsic behavioral and systemic biological factors that are common in our modern environment and may contribute to an observed increase in the prevalence of knee OA, even when adjusting differences in lifespan and obesity compared to pre-industrial human populations. Figure modified from (5). (B). Many ancestral environmental conditions are associated with intrinsic stress-reducing cellular and molecular processes; whereas, modern environmental factors may increase OA risk by stimulating intrinsic stress-inducing processes in chondrocytes.

We were inspired to consider how this evolutionary “mismatch” concept might extend to the molecular basis of OA risk. Many of the conditions that differ between ancestral and modern environments alter joint-level factors that modulate cellular stress positively or negatively (Figure 1B). For example, ancestral environmental conditions are associated with factors that reduce chondrocyte cellular stress, such as cyclic physiologic loading, omega-3 fatty acids, and low levels of pro-inflammatory adipokines. Conversely, obesity and sedentary behavior are associated with factors that increase chondrocyte stress, such as static and infrequent joint loading, pro-inflammatory lipids and adipokines, and pro-oxidant signaling and damage. In fact, many of these factors that induce chondrocyte stress, such as altered biomechanical loading and inflammation, do so in part by altering cellular redox signaling and homeostasis (8-10). Furthermore, oxidative stress is also considered a fundamental component of the age-related increase in the pathogenesis of OA (11, 12). Therefore, the initial purpose of this article is to conceptually review how chondrocytes maintain homeostasis in response to changing stress conditions. In doing so, we introduce the concepts of cellular stress resistance versus resilience. We then evaluate these concepts using three experimental models that focus on glutathione redox regulation as an example of oxidative stress resistance and resilience.

Cellular stress resistance and resilience

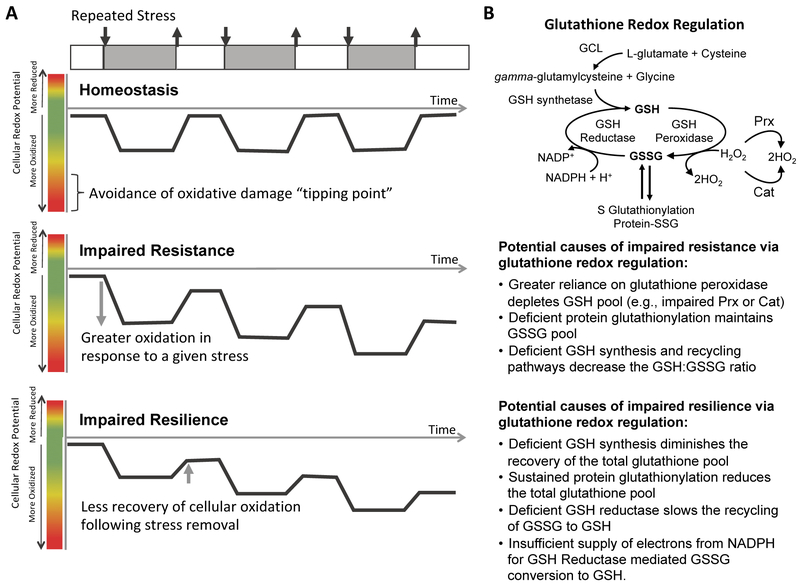

Stress adaptation is considered one of the pillars of healthy aging (13). Low dose stress can be positive by inducing protective “hormetic” responses; whereas, toxic stress exceeds a cellular “tipping point” and induces damage. The intrinsic genetic mechanisms that enable cells to adapt to changing environmental conditions that alter stress involve two related but distinct concepts of cellular stress homeostasis: stress resistance and stress resilience (Figure 2A) (14, 15). Stress resistance is defined as mechanisms that prevent a cell from exceeding a damage-inducing tipping point. Conversely, stress resilience is defined as the ability to repair damage and fully recover function after crossing the tipping point. Therefore, under conditions of increasing stress, such as occurs with obesity, cellular stress resistance mechanisms are chronically engaged to provide the primary means of protection against damage. However, under dynamic stress conditions, such as daily joint loading or following joint trauma, cellular stress resilience mechanisms may be more important and their failure might be more likely to determine the extent of progressive tissue damage.

Figure 2. Resistance and resilience to oxidative stress: conceptual framework and example with glutathione.

(A). Under pro-oxidant producing stress conditions, such as inflammation and biomechanical loading, cellular oxidation increases. During homeostasis, the cellular redox potential returns to baseline following the removal of the stress. However, under conditions of impaired oxidative stress resistance or resilience, the cellular redox potential does not recover to baseline levels. Figure modified from reference (16). (B) Glutathione is a major regulator of cellular redox potential and oxidative damage. Glutathione exists in either a reduced (GSH) or oxidized (GSSG) form. Multiple pathways determine glutathione synthesis and redox balance. Deficits in these pathways may lead to impaired oxidative stress resistance or resilience.

Theoretical models comparing mechanisms of stress resistance versus stress resilience have been described in the field of ecology (16) and have more recently been discussed in the context of aging (14) and neuropsychology (17). Theoretical and experimental approaches to differentiate between stress resistance and resilience have yet to be defined for the field of OA. This distinction is important because the cellular mechanisms that provide stress resistance and resilience are likely distinct and may even impede one-another (14). In vitro cell and tissue culture models of cartilage stress responses often evaluate outcomes immediately following the application of a stress. This approach provides a snapshot of cellular responses that can be sufficient to detect the presence or absence of cellular damage and therefore reflect differences in cellular resistance or resilience mechanisms. However, to differentiate between stress resistance and resilience, studies that incorporate time-dependent responses are required, ideally in response to different magnitudes or durations of repeated stress conditions. These types of studies have revealed important insight into mechanisms of stress adaptation in other biological systems such as drosophila and fibroblasts (18), but they have been underutilized in OA research. We propose that experimental approaches that differentiate between mechanisms of stress resistance and resilience in chondrocytes have the potential to reveal new insight into the pathophysiology of OA in the context of aging and our modern environment.

Glutathione and the regulation of cartilage oxidative stress

Several recent studies have reviewed the role of oxidative stress and altered redox signaling in OA pathophysiology, which includes greater levels of oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, and DNA in cartilage and other joint tissues (11, 12, 19). This pro-oxidant environment is traditionally attributed to insufficient oxidative stress resistance due to an imbalance between the production of free radicals and the ability of the body to detoxify their harmful effects through neutralization by antioxidants. However, emerging evidence shows that insufficient oxidative stress resistance can also apply to non-radical mechanisms since there are major thiol systems active under stable non-equilibrium conditions (20). These non-radical mechanisms involve 2-electron oxidants (e.g. H2O2) that disrupt thiol redox circuits, leading to pro-inflammatory and aberrant cell signaling (21),(22).

The application of cellular resistance and resilience concepts to redox biology is appropriate because there are numerous molecular mechanisms that either prevent or reverse oxidative modifications. For the purpose of this article, we will focus on the glutathione antioxidant system due to its prominent role maintaining cellular redox homeostasis (resistance) and protecting against chronic pro-inflammatory signaling and oxidative damage (resilience, Figure 2B). Glutathione acts as one of the major scavengers for hydroxyl radicals, singlet oxygen, and various electrophiles. It is a tripeptide (cysteine, glycine, and glutamic acid) that exists in either a reduced (GSH) or oxidized (GSSG) form. The oxidized form is generated after the thiol group of the cysteine donates an electron to neutralize a pro-oxidant molecule, such as H2O2, and reacts with another reactive glutathione to form glutathione disulfide (GSSG) (23). GSSG is then converted back to GSH by glutathione reductase, which utilizes NADPH as an electronic donor. Glutathione can also be generated by de novo synthesis. The total glutathione content and the ratio of GSH/GSSG present in the cell are key factors in maintaining cellular redox homeostasis and providing resistance to oxidative stress. Complete recovery of glutathione redox balance and the protection against irreversible oxidative damage via protein S-glutathionylation provides resiliency to oxidative stress (40).

Decreased GSH with aging has been observed in multiple cell types and species (24, 25). The ratio of GSH/GSSG is lower in chondrocytes from older human donors (≥ 50) compared with younger donors (18-49), and it was associated with a higher susceptibility to oxidant induced cell death (26). Similarly, the GSH/GSSG ratio was reduced with aging in articular cartilage of F344-BN F1 hybrid rats (27). The reduction in GSH/GSSG ratio with aging suggests that glutathione resistance to oxidative stress is impaired with aging. Indeed, the redox couples that provide reducing equivalents required for maintaining the GHS/GSSG ratio (i.e., NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH) are themselves reduced with aging and shifted in favor of oxidation (20, 21). Thus, impaired glutathione resilience may contribute to sustained biomechanical and pro-inflammatory-induced chondrocyte redox stress, especially during aging (8, 28, 29).

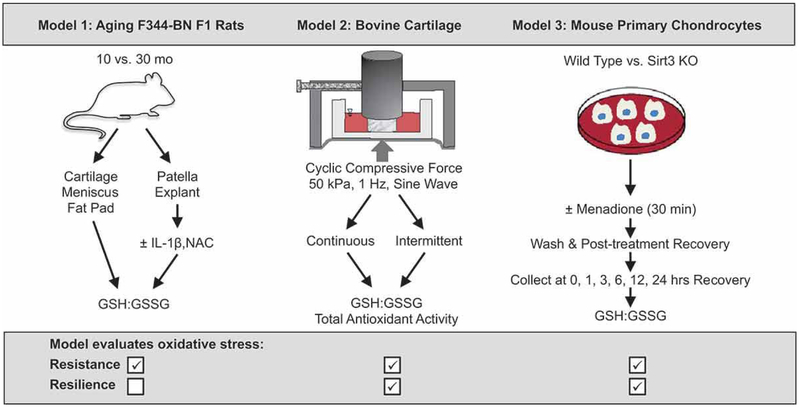

Therefore, to experimentally evaluate these oxidative stress resistance and resilience concepts in cartilage, we compared the changes in glutathione content and redox ratio in three different models of chondrocyte stress (Figure 3). In the first model, we analyzed glutathione in multiple joint tissues from young and old rats to better understand how cartilage compares to other joint tissues in terms of whole-joint age-related changes in glutathione content and redox ratio. We further evaluated glutathione oxidative stress resistance using an ex vivo patella culture model to challenge explants from adult and aged rats with the pro-inflammatory OA-associated cytokine interleukin-1beta (IL-1β). We also treated samples with the anti-oxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) to determine if age-related changes in anti-oxidant capacity impair glutathione stress resistance. In the second model, we applied different durations and “on - off” patterns of cyclic loading to bovine cartilage explants to evaluate how temporal variables contribute to glutathione stress resistance (GSH/GSSG ratio and content) and resilience (recovery of GSH/GSSG balance). In the third model, we evaluated time-dependent changes in oxidized and reduced glutathione content in chondrocytes challenged with the pro-oxidant chemical menadione. In this model, we incorporated an age-dependent feature by comparing outcomes in cells isolated from wild type (WT) and sirtuin 3 null (Sirt3 KO) mice. We used this model because Sirt3, which is an NAD+ dependent mitochondrial deacetylase, regulates mitochondrial antioxidant function and is reduced in aging cartilage. Thus, effects of Sirt3 and menadione on the ratio and content of GSH/GSSG and the time-dependent recovery of glutathione redox balance provide insight into the mechanisms of oxidative stress resistance and resilience mechanisms, respectively. We hypothesized that these three models would reveal multiple mechanisms by which stress resistance and stress resilience contribute to cartilage redox regulation and cellular homeostasis.

Figure 3. Experimental models to evaluate the role of glutathione in oxidative stress resistance and resilience in cartilage.

Model 1 compares multiple joint tissues from young and old rats to better understand how cartilage compares to other joint tissues in terms of whole-joint age-related changes in glutathione content and redox ratio. An ex vivo patella culture model was used to evaluate acute pro-inflammatory and anti-oxidant treatment effects on glutathione stress resistance. Model 2 compared different durations and "on - off" patterns of cyclic loading of cartilage explants to determine how temporal variables contribute to glutathione stress resistance and resilience concepts. Model 3 evaluated time-dependent changes in oxidized and reduced glutathione content in primary murine chondrocytes challenged with the pro-oxidant chemical menadione. The model compared wild type (WT) versus sirtuin 3 null (Sirt3 KO) mouse chondrocytes as an age-related feature because Sirt3 decreases with age in cartilage. We hypothesized that these three models would reveal multiple mechanisms by which stress resistance and stress resilience contribute to cartilage redox regulation and cellular homeostasis.

MATERIAL & METHODS

All procedures involving tissues collected from animals were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the OMRF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Data presented in Models 1 and 2 were conducted as ancillary experiments of previously published studies (8, 27, 30).

Model 1 - Aging F344-BN Rats

Male F344-BN F1 hybrid rats were purchased from the NIA Aging Rodent Colony at 7 and 26 mo of age. Animals were housed 1-2 per cage in OMRF’s vivarium with ad libitum access to NIH31 chow diet (Harlan) until they reached 10 and 30 mo of age. Joint tissues were collected from 3 animals per age. Animals were euthanized by decapitation between 8:30 AM - 11:00AM, and tissues were immediately prepared for glutathione measurements or ex vivo tissue culture. Tissue preparation for oxidized and reduced glutathione measurement was measured using an enzymatic recycling method (Cayman Chemicals) as previously described (27). Glutathione concentration was normalized to total protein content of each sample (BCA Protein Assay; Thermo Scientific). Ex vivo patella culture was conducted as previously described for ex vivo infrapatellar fat pad culture (30). Patellas were harvested by dissecting the patellar tendon unit distally using sterile forceps and scissors. The fat pad, tendon, and other connective tissue were carefully trimmed from the patella. Patellas were weighed, rinsed in sterile PBS, and cultured ex vivo for 2 hours in low glucose DMEM culture media, which included 1μM non-essential amino acids, 10mM HEPES, 100U/ml penicillin-streptomycin and 5% FBS (Gibco brand media reagents from Life Technologies). After 2 hours, the culture media were replaced with fresh media alone or containing 1ng/ml rhIL-1β (R&D), 2.5 mM N-acetylcysteine (NAC), or IL-1β + NAC. Samples were then cultured for an additional 24 hrs in an incubator maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. Sample-free culture media added to each culture plate served as background controls. Samples were immediately frozen and stored at −80°C until homogenized for glutathione measurement (27).

Model 2: Bovine Cartilage Cyclic Compression

Young adult (8-30 mo) bovine metacarpophalangeal (fetlock) joints were obtained from a local abattoir within 4 hours of death. 4-mm macroscopically healthy cartilage explants were excised from load-bearing regions and cultured under free-swell conditions for 3 days. Site-matched explants were then transferred to free-swell control plates or 6-well loading plates modified for use with a Flexcell FX5000 system (Flexcell International) where explants were subject to a compressive 10-gram (8 kPa) tare pre-load. An additional 50 kPa compressive force was applied dynamically using a sine waveform at a frequency of 1 Hz continuously or in alternating 12-hr bouts for up to 60 hrs. Following the completion of the experiment, explants were briefly blotted on tissue paper, weighed, placed in a cryotube, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for later analysis. Oxidized and reduced glutathione were measured in two cryo-pulvarized explants per animal using a DTNB based Glutathione Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical) following manufacturer instructions. Total antioxidant capacity was measured in two separate cryo-pulvarized explants using a total antioxidant capacity assay kit per manufacturer instructions (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), and catalase activity was measured in an additional pair of explants using a previously described method (31). Additional general experimental details are provided in Issa et al. (8). All results were expressed as a percent of animal and site-matched free-swell control cartilage explant values to control for variation and increase statistical power.

Model 3: Mouse Primary Chondrocyte Oxidative Stress Challenge

Primary murine chondrocytes were isolated from 6-8 day old male or female Sirt3flox/flox wild type (WT, n=5) and Sirt3 deficient Sox2-cre;Sirt3flox/flox (KO, n=5) mice according to previously published protocols (32). Cells were cultured and expanded in 6-well plates before reaching confluency in complete DMEM media (Life Technology, 10567014) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were then trypsinized and seeded at 125,000 cells per well in 24-well plates for treatment. To optimize the treatment condition, adherent cell number and cell viability were tested after 1 and 2 hours of menadione (SIGMA-ALDRICH, M5625) treatment at multiple concentrations (0, 10, 25, 50, 100, and 200μM). One full-color brightfield image of cells per well was obtained at 20x using a Zeiss Axiovert 200m Inverted Fluorescent Microscope. Adherent cell number and cell viability (percent of non-trypan blue positive cells) were then determined in a blinded fashion. The effect of Sirt3 on basal reduced and oxidized glutathione levels was measured 24 hrs following a media change using an enzymatic recycling as previously described (Glutathione Assay Kit [703002], Cayman Chemicals) (27). Additional experiments were conducted in a separate set of primary cells harvested from WT and Sirt3 deficient animals (n=3 each) to test time-dependent effect of menadione treatment on glutathione redox balance. Menadione treatments 10μM or 25μM were added to complete media for 30 min. After 30 min the cells were washed with PBS and further cultured in complete media. Cells were collected for reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and electrochemical (HPLC) analysis in 5% meta-phosphoric acid (SIGMA-ALDRICH, 239275) in PBS buffer on ice. The levels of glutathione (GSH) and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) were determined using HPLC (33). All glutathione results were normalized to protein concentration measured by BCA assay.

RESULTS & DISCUSSION:

Model 1: Joint Tissue-Specific Changes in Glutathione Redox Balance in Aging F344-BN Rats

Oxidative stress is considered a fundamental component of the age-related pathological changes in cartilage (11). We recently reported that cartilage undergoes increased glutathione oxidation in aging F344-BN F1 hybrid rats (27). These data were consistent with a prior study by Del Carlo and Loeser who showed that glutathione oxidation increased with age in chondrocytes isolated from young and old human donors that did not have a history of joint disease (26). The authors also showed that chondrocytes depleted of intracellular glutathione were more susceptible to cell death induced by SIN-1, a potent producer of peroxynitrite (ONOŌ). In addition to chondrocytes, synovial fluid glutathione levels have also been reported to decline with age (34), suggesting that glutathione deficiency may be pervasive throughout the joint with aging and associated with compromised stress resistance or resilience and increased in OA risk.

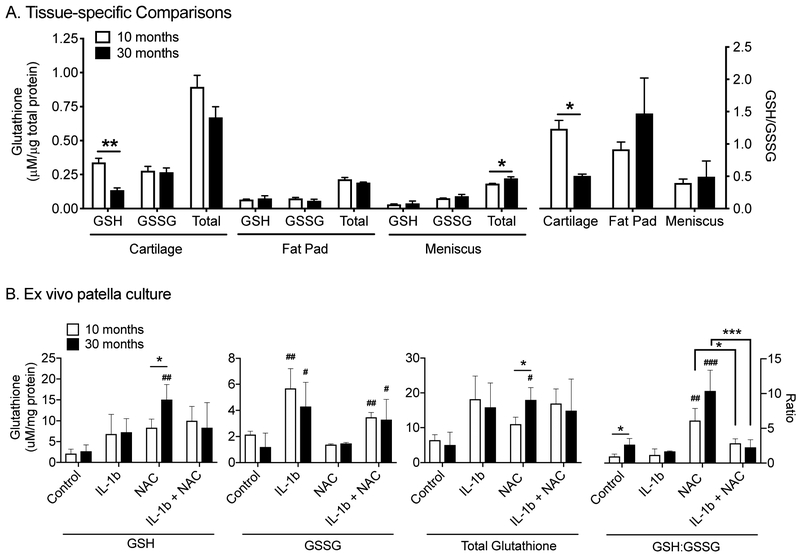

To better understand the whole-joint age-related changes in glutathione, we measured the reduced and oxidized glutathione content in the infrapatellar fat pad and meniscus of adult and aged F344-BN F1 hybrid rats (Figure 4A). Unlike cartilage, neither the fat pad nor meniscus glutathione content became more oxidized with age, suggesting more potential to resist oxidative stress. However, the protein-specific content of glutathione was substantially lower in both fat pad and meniscus compared to cartilage, which would decrease the overall capacity of glutathione to resist cellular oxidation. Aging caused a modest significant increase in total glutathione content of the meniscus without altering the GSH:GSSG ratio, which remained in a more oxidized state (Figure 4A). This change may represent in adaptive response to increase glutathione antioxidant capacity and stress resistance in response to age-related pro-oxidant increases. Overall, these data indicate that glutathione is particularly enriched in cartilage compared to other joint tissues. However, the depletion of reduced glutathione with age reduces its cellular resistance to oxidative stress in cartilage. The observation that total glutathione content was greatest in cartilage in 10-month old animals suggests that the high tissue-specific content is not an age-associated adaptive response to increased cartilage oxidation, although it may indicate a distinct role for glutathione redox regulation in cartilage oxidative stress resistance.

Figure 4. Effect of aging on glutathione redox balance and content in rat joint tissues.

(A) Comparison of reduced (GSH), oxidized (GSSG), and total (GSH+GSSG) glutathione content normalized to protein in knee joint tissues from adult and aged F344BN F1 hybrid rats (left Y-axis). Ratio of reduced:oxidized glutathione content in knee joint tissues of adult and aged rats (right Y-axis). Values are mean ± sem, n=3 per age. *p<0.05, **p<0.01; unpaired, two-tailed t-test (Prism 8). (B) The same glutathione measurements in patella explant cultures treated with interleukin-1beta (IL-1b) and/or N-acetylcysteine (NAC) for 24 hrs. Values are mean ± sem, n=3 per age. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 for age or treatment comparisons; #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 for within age treatment effects versus control; 2-way ANOVA with Tukey's Multiple Comparisons test (Prism 8).

Aging may increase joint stress by up-regulating pro-inflammatory paracrine mediators (i.e., “inflammaging” (35)). To gain further insight into age-related changes in joint tissue stress resistance, we challenged the patella with IL-1β and NAC under experimentally controlled ex vivo culture conditions. Our goal was to understand the effect of aging on changes in glutathione content and redox homeostasis under inflammaging-like conditions and therapeutic anti-oxidant conditions. NAC’s anti-oxidant functions are primarily attributed to its role as a cysteine donor for glutathione synthesis (36). In settings where glutathione is not limiting, the anti-oxidant role of NAC treatment is expected to be less effective. Thus, NAC treatment would reduce glutathione oxidation to a greater extent in patella explants from 30- versus 10-month-old animals if aging limits glutathione synthesis.

NAC treatment significantly increased reduced glutathione content, although the effect was only observed in explants from 30-month-old animals (>5-fold increase, p=0.0031) (Figure 4B, left panel). This suggests that glutathione synthesis was limiting in aged patellas and that NAC can increase glutathione resistance to oxidative stress. In contrast, IL-1β treatment significantly increased GSSG compared to control conditions in both 10- and 30-month old samples (p=0.0056 and p=0.015, respectively). NAC treatment did not significantly reduce the increase in GSSG caused by IL-1β treatment in either young or old samples, and NAC alone did not alter GSSG content. When total glutathione content was evaluated, it was only significantly increased in 30-month-old samples with NAC treatment in part because the majority of glutathione was detected as GSH. Interestingly, the ratio of GSH:GSSG showed significant treatment, age, and interaction effects (p<0.0001, p=0.0199, and p=0.0458, respectively, by 2-factor ANOVA; Figure 4B, right panel). The primary effects occurred with NAC treatment, which significantly increased the ratio of GSH:GSSG in young and old samples. These findings support a role for NAC in oxidative stress resistance in young and old animals. Samples treated with both IL-1β and NAC, however, did not show the same increase. The only significant age-related differences were observed under basal culture conditions where glutathione was more reduced in patella explants from aged animals. Interestingly, this is the opposite of what was observed for cartilage (Figure 4B). These findings support the view that aging significantly alters the role of glutathione as a stress-resistance mediator. However, in the patella, which is composed of multiple joint tissues (e.g., cartilage, bone, ligament, bone marrow), oxidative stress resistance appears to be greater under basal conditions with increasing age and more amenable to NAC treatments. Under inflammatory conditions, however, NAC did not increase glutathione oxidative stress resistance.

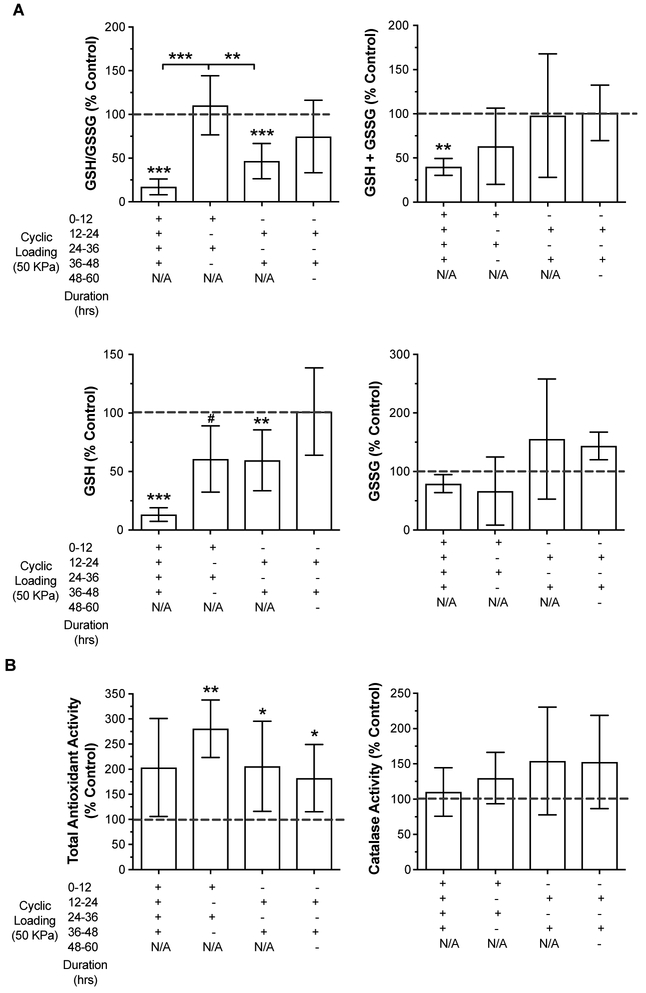

Model 2: Time-dependent Biomechanical Regulation of Bovine Cartilage Antioxidant Networks

The stress resistance-resilience framework predicts that the ability of cells to mitigate stress is dependent on the duration of applied stress and the time period of relief between applied stresses (Figure 2A). In the context of cartilage oxidative stress, we previously investigated the effect of different magnitudes and frequencies of compressive biomechanical loading on bovine cartilage antioxidant mechanisms (8). We hypothesized that physiologic cyclic loading would increase chondrocyte oxidative stress resistance by upregulating the expression and activity of endogenous antioxidants. We compared intermittent cyclic and continuous static loading at physiologic (50 kPa) and supraphysiologic (300 kPa) levels and found that only intermittent cyclic physiologic loading showed a positive effect. This loading condition upregulated total glutathione content, increased mRNA levels of superoxide dismutase 1 (Sod1), and increased protein levels of peroxiredoxin 3 (PRDX3) (8).

Our experimental design for physiologic loading in this prior study was broadly modeled after the circadian pattern of physical activity in which a period of sustained loading is followed by a period of sustained rest. As such, cyclic loads were applied for 12 hrs followed by a period of rest for 12 hrs. Samples were collected after two sequential loading-rest cycles (i.e., 48 hrs total). Therefore, in the current context of cellular resistance and resilience, we wanted to know how removing the rest cycle would affect our results. In other words, is a period of unloading necessary for cyclic compressive loading to increase oxidative stress resistance (i.e., total glutathione content)? For these experiments, we also tested the effect of continuous cyclic loading versus reversed load-rest and rest-load intermittent loading patterns.

We found that the presence and pattern of load-rest cycles significantly altered glutathione redox balance and content (Figure 5A). Cartilage that was continuously loaded under physiologic cyclic conditions for 48 hrs without rest underwent a significant net oxidation of glutathione. This net oxidation would reduce the ability of glutathione to resist future bouts of oxidative stress. Moreover, total glutathione levels were reduced >50% because of a loss of reduced glutathione content, further impairing stress resistance capacity. The reason for such a substantial reduction in total glutathione is not known. This level of loading may be expected to cause up to 20% cell death (8), although greater cell death cannot be ruled out and may contribute to these findings. The addition of a rest period, regardless of the order of load-rest periods prior to tissue collection (i.e., load-rest or rest-load), prevented the loss of total glutathione content. Interestingly, the order of load and rest periods altered the glutathione redox balance. Intermittent-loaded samples that were collected immediately at the end of a period of loading were more oxidized compared to those that were collected after a period of rest. This finding indicates that physiologic loading induces a state of glutathione oxidation that recovers after an equal period of rest. Altering the magnitude of loading, duration of loading, or period of rest could help define the limit of articular cartilage resiliency for maintaining glutathione redox balance. This information could be useful for establishing defined “stress test” conditions to test how OA risk factors, such as aging and inflammation, affect cartilage biomechanical redox resiliency.

Figure 5. Effect of continuous versus intermittent bouts of compressive cyclic loading on endogenous cartilage antioxidants.

(A) Healthy bovine cartilage explants were compressed with a 50 kPa 1Hz cyclic loading pattern continuously or in 12-hr "on-off" bouts for up to 60 hrs as indicated along the X-axis. Reduced (GSH), oxidized (GSSG), and total (GSH+GSSG) glutathione content and the GSH/GSSG ratio were plotted as percentages of unloaded site and animal-matched control explants. Values are mean ± sd, n=4-8 per loading group. #p=0.052, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 versus unloaded controls (one-sample t-test) or between two groups as indicated by bars (1-way ANOVA with Tukey's Multiple Comparisons test) (Prism 8). (B). Total antioxidant activity and catalase activity from cartilage explants harvested from the same joints and loading experiments as presented in panel A. Values are mean ± sd, n=4-8 per loading group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, versus unloaded control value (one-sample t-test) (Prism 8).

The additional stress resistance outcomes we tested were not sensitive to the different load-rest patterns (Figure 5B). The total antioxidant activity assay, which tests the ability to scavenge an ABTS+ radical cation (37), increased significantly in all intermittent cyclic loading conditions. Antioxidant activity also increased with continuous loading, although the change was not significant, and there was increased variability compared to intermittent loading. Unlike total antioxidant activity, catalase activity was not altered with loading. The intermittent loading conditions tended to show an increase in catalase activity, but variability was quite large and there were no significant differences across the groups. Thus, these findings indicate that different patterns of cyclic biomechanical stress cause specific changes to different antioxidant networks. Overall, the results presented here indicate that the glutathione antioxidant defense system is sensitive to the “on-off” durations of cyclic stress, which affects how glutathione contributes to oxidative stress resistance and resilience in articular cartilage.

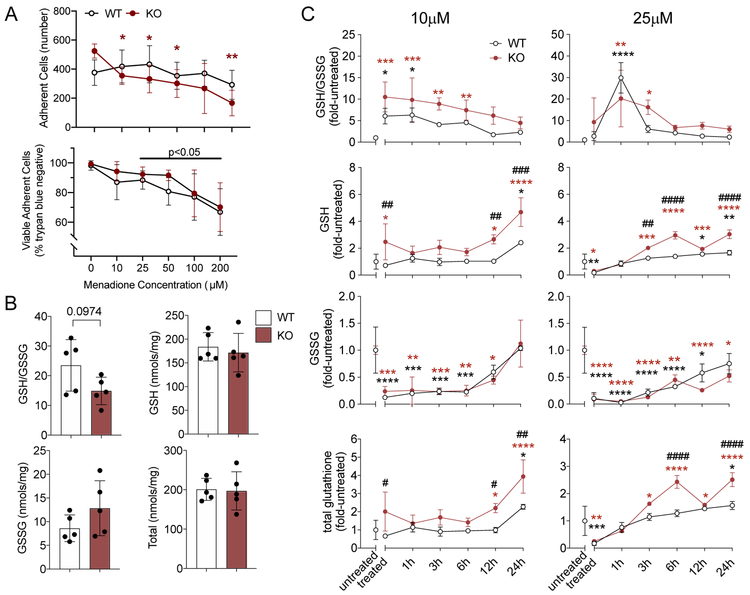

Model 3: Time and Dose Dependent Changes in Glutathione Redox Balance in Primary Mouse Chondrocytes Following a Pro-oxidant Challenge

In this third model, we examined how the magnitude of a pro-oxidant stress affected the recovery of glutathione redox homeostasis in primary mouse chondrocytes. We incorporated an age-dependent feature by comparing outcomes in cells isolated from wild type (WT) and sirtuin 3 null (Sirt3 KO) mice. Sirt3 is a critical regulator of cellular metabolism and anti-oxidant defense pathways (38). It does so by removing post-translational acetylated lysines on hundreds of mitochondrial proteins at multiple sites per protein (39). We previously showed that SIRT3 protein decreased in cartilage with aging and that this decrease was associated with increased SOD2 acetylation and impaired enzyme specific activity (27). Isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2) acetylation was also increased in cartilage with aging (27), which may contribute to the decrease in cartilage GSH/GSSG ratio in aged cartilage. IDH2 activity is required for reducing GSSG to GSH through its role in synthesizing a critical cofactor, NADPH. Thus, SIRT3 deficient chondrocytes may serve as an age-related model of impaired resistance to oxidative stress.

To test this prediction, we challenged primary chondrocytes isolated from WT and Sirt3 KO mice with menadione, which induces a pro-oxidative stress by producing intra-cellular H2O2 in an oxidation-reduction cycle employing the endogenous NAD+ pool. We first evaluated the cellular toxicity of menadione using a range of concentrations (0 - 200μM) and dosing durations of 1 and 2 hrs. Compared to the untreated control, 1 hour of menadione treatment reduced the adherent cell number only at a concentration of 200 μM (data not shown). Following 2 hours of treatment, there was a significant dosage (p=0.0004) and dosage x genotype interaction (p=0.008) on adherent cell numbers (Fig. 6A). A post-hoc analysis showed that the reduction in adherent cells was only significant in KO cells. Of those cells that remained adherent, cell viability was reduced in both WT and KO cells at menadione concentrations ≥25 μM (Fig. 6A). Treatment for 1 hour caused <10% change in cell viability at concentrations ≤25 μM. Thus, in our subsequent experiment, we treated chondrocytes with 10 and 25μM of menadione for 0.5 hour to minimize cell death as a confounding factor.

Figure 6. Effect of Menadione Pro-oxidant Challenge on Glutathione Redox Homeostasis in Wild-type and Sirt3 KO Primary Mouse Chondrocytes.

(A) Menadione treatment concentration was optimized by evaluating cell adherence and viability following a range of menadione treatments for 2 hrs. Cell adherence was reduced in Sirt3 KO cells, and the viability of adherent cells was reduced in WT and KO cells at ≥25 μM menadione. Values are mean ± sd in n=5 independent biological replicates per genotype (*p<0.05, **p<0.01; Dunnett’s posthoc test versus untreated condition, 2-way repeated-measures anova). (B) Comparison of reduced:oxidized glutathione ratio and protein normalized glutathione content in WT and Sirt3 KO cells under basal culture conditions. Values are mean ± sd for n=5 independent biological replicates. Statistical analysis used an unpaired two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction. (C) GSH/GSSG ratio and GSH, GSSG and total glutathione levels normalized to average genotype-specific untreated value. Treated samples were collected immediately after 30 min menadione treatment. Additional time points indicate the duration (hrs) since menadione was removed. For data points where GSSG was not detected, the lowest limit of detection value was imputed for statistical purposes. Statistical analyses were evaluated by two-way ANOVA, with Dunnett’s posthoc test used to compare the effects of treatment (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001) and genotype (#p<0.05, ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001, ####p<0.0001). Values are mean ± sd for n=3 independent biological replicates per genotype with the following exceptions where n=2 due to a technical issue with sample processing (KO untreated, WT treated, KO treated). The same cell sources were used for all treatment conditions.

Under basal conditions, reduced and oxidized glutathione levels were similar in Sirt3 KO and WT chondrocytes although the GSH/GSSG ratio trended lower in Sirt3 KO chondrocytes (Figure 6B). This finding suggests that resistance to oxidative stress may be reduced in Sirt3 KO chondrocytes. To further test oxidative stress resistance and resilience, WT and Sirt3 KO cells were challenged with 10 and 25μM of menadione for 30 minutes and then followed for up to 24 hours post-treatment. Menadione treatment significantly increased the GSH/GSSG ratio at both treatment concentrations and in both genotypes (fold-change versus untreated; Figure 6C), although the increase was delayed with the 25μM treatment. From a stress resistance perspective, this finding indicates that chondrocytes are able to rapidly increase oxidative stress resistance through the glutathione pathway when challenged with an intra-cellular pro-oxidant stress.

Following the removal of menadione-generated oxidant stress, the GSH/GSSG ratio decreased over time, trending towards basal values. The GSH/GSSG ratio returned to basal (untreated) values by 3 hrs in the WT cells and 6-12 hrs in the Sirt3 KO cells, indicating an effect of Sirt3 on chondrocyte glutathione resilience. The initial GSH/GSSG increase was primarily driven by a decrease GSSG in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6C). Notably, 25μM menadione treatment lowered the GSSG concentration to non-detectable levels 1 hr after treatment. Within 24 hrs of a 10μM menadione challenge, GSSG returned to basal levels in WT and Sirt3 KO cells. However, 24 hrs following a 25μM menadione challenge, GSSG only returned to basal levels in WT cells. This delay suggests that Sirt3 deficiency reduces time-dependent glutathione resilience to oxidative stress. Interestingly, after an initial decrease in GSH following the 25μM menadione treatment, both WT and Sirt3 KO cells gradually up-regulated GSH above basal levels, consistent with an increase in stress resistance. In fact, relative to basal levels, Sirt3 KO chondrocytes up-regulated GSH and total glutathione levels more than WT cells 24 hrs after 10μM and 25μM treatments. Thus, these results suggest that Sirt3 KO cells generate a more robust stress resistance response to oxidative stress.

The observed time-dependent changes in reduced and oxidized glutathione in WT and Sirt3 KO cells raise intriguing questions about glutathione redox regulation in oxidative stress resilience and resistance. The increase in post-treatment GSH levels in Sirt3 KO cells might be explained by enhanced oxidant-sensitive regulatory mechanisms. For example, the activity of the rate-limiting enzyme for GSH synthesis, glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL, Fig. 2B), is positively regulated by pro-oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide. Sirt3 deficiency may increase hydrogen peroxide-dependent signaling by inhibiting the production of NADPH due to an increase in the acetylation of isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (40). NADPH protects against cellular redox stress by providing reducing equivalents to thioredoxin reductase, which regulates thiol/disulfide couples and hydrogen peroxide metabolism via thioredoxin-1 and peroxiredoxins, respectively (20). NADPH is also required for providing reducing equivalents to convert GSSG back to GSH via glutathione reductase. If this is impaired in Sirt3 KO cells or more generally with aging, it might increase the dependence on de novo GSH synthesis via glutamate-cysteine ligase and thereby alter the cellular stress resistance response.

Furthermore, a decrease in GSSG following menadione treatment may indirectly indicate an increase in cellular resilience mechanisms via protein S-glutathionylation. There are two main protein S-glutathionylation pathways in response to oxidative stress (41). One pathway involves protein cysteine sulfenate formation and subsequent S-glutathionylation by GSH. Alternatively, in response to a more severe oxidative stress, S-glutathionylation occurs via direct reaction of the cysteine (P-SH) with GSSG. Thus, our findings suggest that acute menadione treatment triggered the direct reaction of proteins with GSSG. This reaction would consume the GSSG pool and lead to a decrease of both GSSG and total glutathione levels, as observed in our experiments. Thus, while increasing the GSH:GSSG ratio appears to improve stress resistance, it may also indirectly indicate stress resilience by glutathionylating proteins to protect them from oxidative damage and improve the recovery of protein function.

Summary

Knee OA has recently been described as an evolutionary ‘mismatch disease’ based on the apparent inability of genes inherited from prior populations to adequately adapt to the rapid changes in factors associated with OA pathogenesis, such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, dietary changes, and physical inactivity (7). We were inspired to consider how these changes might increase the risk of OA by impairing molecular mechanisms that promote cellular stress resistance and resilience. Stress adaptation is considered one of the pillars of healthy aging, and factors associated with modern lifestyles, such as obesity and physical inactivity, may weaken these cellular stress response mechanisms. The concepts of stress resistance and resilience have been central to the evaluation of human-induced changes to ecological systems for decades. However, the distinction of these concepts is just beginning to be evaluated in biomedical studies. By definition, cellular stress resistance involves mechanisms that prevent a cell from exceeding a damage-inducing tipping point. In contrast, cellular stress resilience emphasizes the ability to repair damage and fully recover function after crossing the tipping point.

We evaluated these concepts by focusing on glutathione redox homeostasis in three different experimental models of OA-related stress. The different types of stressors included aging, inflammation, biomechanical loading, and pro-oxidant stimuli. In each of these models, glutathione content and redox balance was affected. In some cases, glutathione content was diminished or became more oxidized, which indicated a reduced capacity for oxidative stress resistance (i.e., aging, continuous biomechanical loading, and acute pro-oxidant stress). However, some stress conditions increased total glutathione content and increased the GSH:GSSG ratio, indicating a improved capacity to resist oxidative stress. The conditions that improved stress resistance included repeated “on-off” bouts of cyclic compressive loading, NAC treatment in aged joint tissue, and the prior exposure to a pro-oxidant stimulus.

Stress resilience was evaluated by focusing on time-dependent outcomes that improved the recovery of glutathione oxidation. In these cases, we observed that glutathione oxidation recovers in a time-dependent manner in different ways between compressive loading and a pro-oxidant stimulus. Compressive loading depleted the pool of reduced glutathione, which recovered during unloading. In contrast, menadione treatment depleted the pool of oxidized glutathione, which may indicate increased protein glutathionylation under these conditions. These differences suggest that glutathione functions through multiple stress-dependent pathways to promote cellular oxidative stress resistance and resilience. It is also important to note, however, that while stress resistance and resilience concepts are distinct, it can be difficult to distinguish the concepts experimentally since overlapping mechanisms contribute to resistance and resilience. This was the case for Sirt3 deficiency where basal oxidative stress susceptibility was also associated with an enhanced response to acute stress. Nevertheless, the two concepts may be useful for evaluating therapeutic approaches to improve chondrocyte health during aging. At younger ages, stress resistance may help prevent the accumulation of cellular damage; whereas, at older ages, resilience mechanisms may be more important for recovering function after damage has already occurred.

In this article we focused on the glutathione redox system as an example to experimentally elucidate both oxidative stress resistance and resilience in chondrocytes. A similar approach could be applied to other cellular homeostasis networks, such as proteostasis, metabolism, and cell cycle regulation. Hopefully with an improved understanding of the molecular mechanisms that improve cellular stress resistance and resilience, it will be possible to develop more targeted therapies that can overcome our current evolutionary “mistmatch” that has led to increased rates of OA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge Drs. Yao Fu, Rita Issa, and Michael Boeving for their work in generating the data used for experimental models 1 and 2. The authors also thank Dr. Erika Lopes, Melinda West, Joanna Hudson, and Pavithra Premkumar for their assistance with animal care, tissue collection, and data analysis.

FUNDING

Supported by the NIH (R01AG049058 and P30AG050911), Oklahoma Center for Adult Stem Cell Research (OCASCR, a program of TSET), the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (OCAST). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, OCASCR, or OCAST.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kluzek S, Sanchez-Santos MT, Leyland KM, Judge A, Spector TD, Hart D, et al. Painful knee but not hand osteoarthritis is an independent predictor of mortality over 23 years follow-up of a population-based cohort of middle-aged women. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(10):1749–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Losina E, Weinstein AM, Reichmann WM, Burbine SA, Solomon DH, Daigle ME, et al. Lifetime risk and age at diagnosis of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(5):703–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy L, Schwartz TA, Helmick CG, Renner JB, Tudor G, Koch G, et al. Lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(9):1207–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace IJ, Worthington S, Felson DT, Jurmain RD, Wren KT, Maijanen H, et al. Knee osteoarthritis has doubled in prevalence since the mid-20th century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(35):9332–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakravarthy MV, and Booth FW. Eating, exercise, and “thrifty” genotypes: connecting the dots toward an evolutionary understanding of modern chronic diseases. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2004;96(1):3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berenbaum F, Wallace IJ, Lieberman DE, and Felson DT. Modern-day environmental factors in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14(11):674–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Issa R, Boeving M, Kinter M, and Griffin TM. Effect of biomechanical stress on endogenous antioxidant networks in bovine articular cartilage. J Orthop Res. 2018;36(2):760–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman MC, Brouillette MJ, Andresen NS, Oberley-Deegan RE, and Martin JM. Differential Effects of Superoxide Dismutase Mimetics after Mechanical Overload of Articular Cartilage. Antioxidants (Basel). 2017;6(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman MC, Ramakrishnan PS, Brouillette MJ, and Martin JA. Injurious Loading of Articular Cartilage Compromises Chondrocyte Respiratory Function. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(3):662–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolduc JA, Collins JA, and Loeser RF. Reactive oxygen species, aging and articular cartilage homeostasis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;132:73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loeser RF, Collins JA, and Diekman BO. Ageing and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(7):412–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennedy BK, Berger SL, Brunet A, Campisi J, Cuervo AM, Epel ES, et al. Geroscience: linking aging to chronic disease. Cell. 2014;159(4):709–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller BF, Seals DR, and Hamilton KL. A viewpoint on considering physiological principles to study stress resistance and resilience with aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;38:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleshner M, Maier SF, Lyons DM, and Raskind MA. The neurobiology of the stress-resistant brain. Stress. 2011;14(5):498–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nimmo DG, Mac Nally R, Cunningham SC, Haslem A, and Bennett AF. Vive la resistance: reviving resistance for 21st century conservation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2015;30(9):516–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu H, Zhang C, Ji Y, and Yang L. Biological and Psychological Perspectives of Resilience: Is It Possible to Improve Stress Resistance? Front Hum Neurosci. 2018;12:326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pickering AM, Vojtovich L, Tower J, and KJ AD. Oxidative stress adaptation with acute, chronic, and repeated stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;55:109–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drevet S, Gavazzi G, Grange L, Dupuy C, and Lardy B. Reactive oxygen species and NADPH oxidase 4 involvement in osteoarthritis. Exp Gerontol. 2018;111:107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones DP. Redefining oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8(9-10):1865–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones DP. Radical-free biology of oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295(4):C849–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins JA, Wood ST, Bolduc JA, Nurmalasari NPD, Chubinskaya S, Poole LB, et al. Differential peroxiredoxin hyperoxidation regulates MAP kinase signaling in human articular chondrocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;134:139–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pompella A, Visvikis A, Paolicchi A, De Tata V, and Casini AF. The changing faces of glutathione, a cellular protagonist. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66(8):1499–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piccinini G, Minetti G, Balduini C, and Brovelli A. Oxidation state of glutathione and membrane proteins in human red cells of different age. Mech Ageing Dev. 1995;78(1):15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stohs SJ, Lawson T, and Al-Turk WA. Changes in glutathione and glutathione metabolizing enzymes in erythrocytes and lymphocytes of mice as a function of age. Gen Pharmacol. 1984;15(3):267–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlo MD, Jr., and Loeser RF. Increased oxidative stress with aging reduces chondrocyte survival: correlation with intracellular glutathione levels. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(12):3419–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fu Y, Kinter M, Hudson J, Humphries KM, Lane RS, White JR, et al. Aging Promotes Sirtuin 3-Dependent Cartilage Superoxide Dismutase 2 Acetylation and Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(8):1887–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson R, Golub SB, Rowley L, Angelucci C, Karpievitch YV, Bateman JF, et al. Novel Elements of the Chondrocyte Stress Response Identified Using an in Vitro Model of Mouse Cartilage Degradation. J Proteome Res. 2016;15(3):1033–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCutchen CN, Zignego DL, and June RK. Metabolic responses induced by compression of chondrocytes in variable-stiffness microenvironments. J Biomech. 2017;64:49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu Y, Huebner JL, Kraus VB, and Griffin TM. Effect of Aging on Adipose Tissue Inflammation in the Knee Joints of F344BN Rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71(9):1131–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rindler PM, Plafker SM, Szweda LI, and Kinter M. High dietary fat selectively increases catalase expression within cardiac mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(3):1979–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gosset M, Berenbaum F, Thirion S, and Jacques C. Primary culture and phenotyping of murine chondrocytes. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(8):1253–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLain AL, Cormier PJ, Kinter M, and Szweda LI. Glutathionylation of alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase: the chemical nature and relative susceptibility of the cofactor lipoic acid to modification. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;61:161–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Regan EA, Bowler RP, and Crapo JD. Joint fluid antioxidants are decreased in osteoarthritic joints compared to joints with macroscopically intact cartilage and subacute injury. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(4):515–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franceschi C, and Campisi J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69 Suppl 1:S4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rushworth GF, and Megson IL. Existing and potential therapeutic uses for N-acetylcysteine: the need for conversion to intracellular glutathione for antioxidant benefits. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;141(2):150–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller NJ, and Rice-Evans CA. Factors influencing the antioxidant activity determined by the ABTS.+ radical cation assay. Free Radic Res. 1997;26(3):195–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verdin E, Hirschey MD, Finley LW, and Haigis MC. Sirtuin regulation of mitochondria: energy production, apoptosis, and signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35(12):669–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carrico C, Meyer JG, He W, Gibson BW, and Verdin E. The Mitochondrial Acylome Emerges: Proteomics, Regulation by Sirtuins, and Metabolic and Disease Implications. Cell Metab. 2018;27(3):497–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu W, Dittenhafer-Reed K E, and Denu JM. SIRT3 protein deacetylates isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2) and regulates mitochondrial redox status. J Biol Chem, 2012;287(17), 14078–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grek CL, Zhang J, Manevich Y, Townsend DM, and Tew KD. Causes and consequences of cysteine S-glutathionylation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(37):26497–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]