Abstract

Background

GRAS gene is an important transcription factor gene family that plays a crucial role in plant growth, development, adaptation to adverse environmental condition. Sweet potato is an important food, vegetable, industrial raw material, and biofuel crop in the world, which plays an essential role in food security in China. However, the function of sweet potato GRAS genes remains unknown.

Results

In this study, we identified and characterised 70 GRAS members from Ipomoea trifida, which is the progenitor of sweet potato. The chromosome distribution, phylogenetic tree, exon-intron structure and expression profiles were analysed. The distribution map showed that GRAS genes were randomly located in 15 chromosomes. In combination with phylogenetic analysis and previous reports in Arabidopsis and rice, the GRAS proteins from I. trifida were divided into 11 subfamilies. Gene structure showed that most of the GRAS genes in I. trifida lacked introns. The tissue-specific expression patterns and the patterns under abiotic stresses of ItfGRAS genes were investigated via RNA-seq and further tested by RT-qPCR. Results indicated the potential functions of ItfGRAS during plant development and stress responses.

Conclusions

Our findings will further facilitate the functional study of GRAS gene and molecular breeding of sweet potato.

Keywords: GRAS, Transcription factor, Sweet potato, Ipomoea trifida, Expression

Background

GRAS proteins are a family of plant-specific transcription factors whose names are derived from the first three members: GIBBERELLIN ACID INSENSITIVE (GAI), REPRESSOR of GA1 (RGA) and SCARECROW (SCR) [1]. Typically, GRAS proteins consist of 400–770 amino acids residues with a variable N-terminal and a highly conserved C-terminal region [2, 3]. The highly conserved carboxyl terminal region is composed of several ordered motifs, including leucine rich region I, VHIID, leucine-rich region II, PFYRE and SAW, which are crucial for the interactions between GRAS and other proteins [1, 4]. According to the report in Arabidopsis thaliana, the GRAS family is classed into eight well-known subfamilies, including LISCL, PAT1, SCL3, DELLA, SCR, SHR, LAS and HAM [5]. However, Liu et al. (2014) classified the GRAS family into 13 branches. The subfamily identification of GRAS genes has a slight difference among diverse species.

In the recent 10 years, with increasing species having complete genome sequence, the genome-wide analyses of GRAS gene family were carried out in more than 30 species belonging to more than 20 genera, such as in A. thaliana [4], rice [4], maize [6], Chinese cabbage [7], tomato [8], Prunus mume [9] and Poplar [10]. GRAS proteins play diverse functions in regulating plant growth and development, which are involved in signal transduction, root radial patterning [11], male gametogenesis [12] and meristem maintenance [2]. GRAS genes are connected with plant disease resistance and abiotic stress response [13]. OsGRAS23 enhances tolerance to drought stress in rice [14]. The overexpression of poplar PeSCL7 in Arabidopsis increases its resistance to drought and salt stresses [15]. Likewise, Yang et al. (2011) reported that the overexpression BnLAS gene of Brassica napus in Arabidopsis can enhance the drought tolerance of plant [16]. DELLA proteins are involved in response to adverse environmental conditions such as low temperature and phosphorus deficiency [17, 18]. Moreover, NtGRAS1 in tobacco increases the ROS level under various stress conditions [19]. Although these genes play critical roles during plant growth, development and abiotic stress adaption, GRAS gene has not been studied in sweet potato and the other Ipomoea plant.

Sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.] is an important food crop, which ranks seventh in the world [20]. Due to its rich carbohydrates, dietary fibre, vitamins and low input requirements, it is widely grown in tropical areas, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Recently, a comprehensive phylogenetic study of all species closely related to the sweet potato was presented and strongly supported nuclear and chloroplast phylogenies demonstrating that Ipomoea trifida (Kunth.) G. Don (2n = 2x = 30) is the closest relative of sweet potato [21]. And I. trifida is one of the most important material for studying self-incompatibility, sweet potato breeding, sweet potato transgenic system construction and whole genome sequencing due to its small size, low ploidy, small chromosome number and simple genetic manipulation [21–23]. In 2017, the genome data of I. trifida were released (http://sweetpotato.plantbiology.msu.edu/), thus allowing the genome-wide identification and analysis of important gene families in I. trifida [23].

Therefore, we performed the genome-wide identification of GRAS transcription factors in I. trifida. We firstly investigated the phylogeny, chromosomal locations and exon/intron structure of GRAS transcription factors in I. trifida. Moreover, we checked the expression profiles of ItfGRAS genes in different tissue under various abiotic stress conditions by analysing RNA-Seq data and qRT-PCR experiment validation. Our work will provide evidence for further study of GRAS gene function and sweet potato breeding.

Methods

Identification of GRAS genes in I. trifida

All candidate ItfGRAS genes were derived from Sweetpotato Genomics Resource (http://sweetpotato.plantbiology.msu.edu/index.shtml). The Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/search) was used to identify all likely GRAS proteins containing GRAS domains. To further confirm amino acid sequences with GRAS domains, we used the NCBI Conserved Domain search and SMART to ensure the accuracy of these transcription factors. Only the sequences with full-length GRAS domain were used for further analyses. At the same time, the online software ExPASy (http://expasy.org/tools/) was used to obtain the molecular weight (MW), isoelectric point (pI) and amino acid numbers of ItfGRAS proteins. We predicted the subcellular locations of these GRAS proteins by using the online WoLF PSORT (http://wolfpsort.org/).

Chromosomal location and exon–intron structures analysis of GRAS members in I. trifida

The physical positions of all ItfGRAS genes were determined using GFF annotation file downloaded from Genomic Tools for Sweetpotato Improvement (GT4SP) project. We mapped the genetic linkage map of GRAS genes in the whole I. trifida genome by using MapDraw.

The web-based bioinformatics tool GSDS 2.0 (gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) [24] was used to identify information on the intron/exon structure by comparing the coding domain sequences and genomic sequences of ItfGRAS genes.

Phylogenetic analysis of GRAS proteins

We obtained Arabidopsis and rice GRAS amino acid sequences from plant TFDB (http://planttfdb.cbi.pku.edu.cn/). I. trifida GRAS proteins were aligned with the well-classified Arabidopsis rice GRAS proteins by using ClustalW to generate a phylogenetic tree. The phylogenetic analysis of the aligned sequences was then carried out by using the Maximum-Likelihood method. As a tool for building a phylogenetic tree, MEGA 7.0 [25] has parameters set to the P-distance model and pairwise deletion options with 1000 bootstrap replicates. During this construction, several ItfGRAS proteins with relatively less amino acid residues than the amino acid residues in typical GRAS domain were excluded.

Analysis of Cis-acting elements in ItfGRAS promoters

To determine cis-acting elements in the promoter regions of ItfGRASs, we first extracted the promoter sequences (2 kb) for every ItfGRAS gene from I. trifida genomic DNA, and then submitted the sequences to online tool PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) [26] to predict cis-acting elements in ItfGRAS promoters. And TBtools software (v0.6654) (https://github.com/CJ-Chen/TBtools) was used to visualize the final results.

Expression analysis of GRAS members

We downloaded the original RNA sequencing data from the GT4SP Project Download page to investigate the expression profiles of GRAS genes under abiotic stresses (drought, salt, heat and cold) and among various tissues (root, stem, leaf, flower and flower bud). Heat maps and hierarchical clustering for I. trifida GRAS genes based on fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) values were generated using MeV v4.8.1 [27]. The expressions of ItfGRASs in various tissues were normalized by Z-score, and all FPKM values of tissue specific expression and abiotic stresses are shown in Additional file 5-6: Table S4-S5.

Plant materials and stress treatments

I. trifida (2x) plants were collected from the Sweet Potato Research Institute, Xuzhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences, National Sweet Potato Industry System, China. I. trifida growing up to 4 weeks was used as experimental material in this study. The growth conditions of I. trifida were as follows: light/dark for 16/8 h at 28 °C day/ 22 °C night.

For cold treatment, the 4-week-old I. trifida was transferred into a light incubator at 10 °C. Under heat treatment, these plants were grown in a light incubator at 39 °C. A 250 mM NaCl was poured into the pots under salt treatment. For drought treatment, whole plants were perfused with 300 mM mannitol solution. For the above treatments, all plants were grown under a 16/8 h (light/dark) photoperiod. Each treatment group was set to a control (without any treatment, growing under normal conditions). Leaf and root samples for experiment were obtained at 0, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h after treatment. All samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C for subsequent use.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis

To validate the data of expression patterns based on RNA sequencing, we selected 10 genes with significantly high expression levels under stress and among tissues. The samples collected above include root, stem, mature leaf, young leaf and flower for tissue-specific expression and root and leaf samples for abiotic stresses. Total RNA was extracted from the frozen samples by using an RNAprep pure plant kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). The PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Dalian, China) was used to synthesize the first-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) with 1 μg of total RNA in a 20 μL volume according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The specific GRAS primers for qRT-PCR analysis were designed using Primer Premier 5 and are shown in Additional file 7: Table S6. The GAPDH gene was used as internal control gene. qRT-PCR analysis was performed using an ABI StepOnePlus instrument and the SYBR premix Ex Taq™ kit (TaKaRa, China). The thermal circulation conditions were set as follows: 95 °C for 5 min, 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 20 s followed by 40 cycles. The specificity of each primer pair was verified by melting curve analysis. We analysed the expression profiles by calculating the mean of the expression levels obtained from three independent experiments according to the 2 − ΔΔCt method reported by Livak et al. (2001) [28].

Statistical analysis

The qRT-PCR raw data were calculated according to the 2 − ΔΔCt method [28], and then subjected to ANOVA and means compared by the Dunnett’s test (“*” for P < 0.05). The SPSS software package (v.22) was used for statistical analysis. Microsoft Excel 2010 was used to calculate the standard errors (SEs). Graphpad prism 5.0 software was used to generate graphs.

Results

Identification and characterization analysis of GRAS genes in I. trifida

To identify the number of GRAS members in I. trifida, we used both Pfam and SMART databases with the default parameters. A total of 75 candidate ItfGRAS genes were identified. Among them, five ItfGRAS genes were excluded, because the GRAS domain region in those proteins contains less amino acid residues than the typical GRAS domain (Additional file 2: Table S1). Hence, only 70 ItfGRAS genes were finally kept and used for further analyses, and the result of 70 ItfGRAS protein sequence alignments are shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Basic information, such as the number of amino acids, MWs, theoretical pI and intron numbers, for the GRAS proteins in I. trifida is listed in Additional file 2: Table S1. The length and MW/kDa of 70 GRAS proteins were 178–957 aa and 20–103.9 kDa, respectively. The predicted pI of I. trifida ranged from 4.76–9.45 (Additional file 2: Table S1).

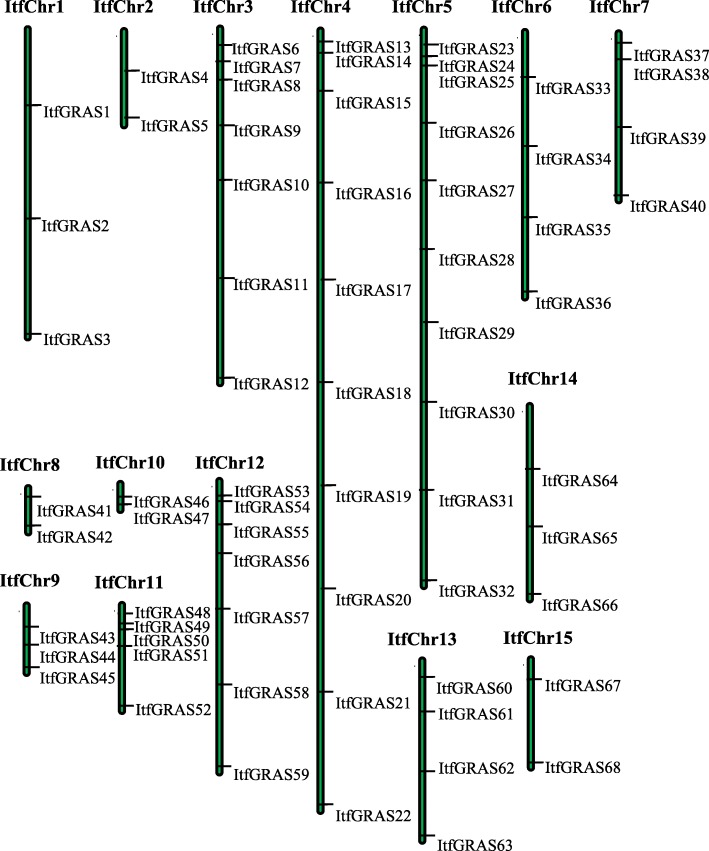

Chromosomal distributions of ItfGRAS genes

The identified GRAS genes were mapped to 15 I. trifida chromosomes according to the download GFF3 profile. However, two GRAS members were not obviously mapped onto any chromosomes but were located on unattributed scaffolds. ItfGRAS genes were unevenly distributed among chromosomes. Figure 1 shows that Chr4 and Chr5 containing 10 (14.7%) GRAS members were the most abundant. Chr2, Chr8, Chr10 and Chr15 contained only two genes (3%), while the number of genes located in the remaining chromosomes ranged from 3 to 7.

Fig. 1.

Chromosomal locations of GRAS genes in I. trifida along 15 chromosomes

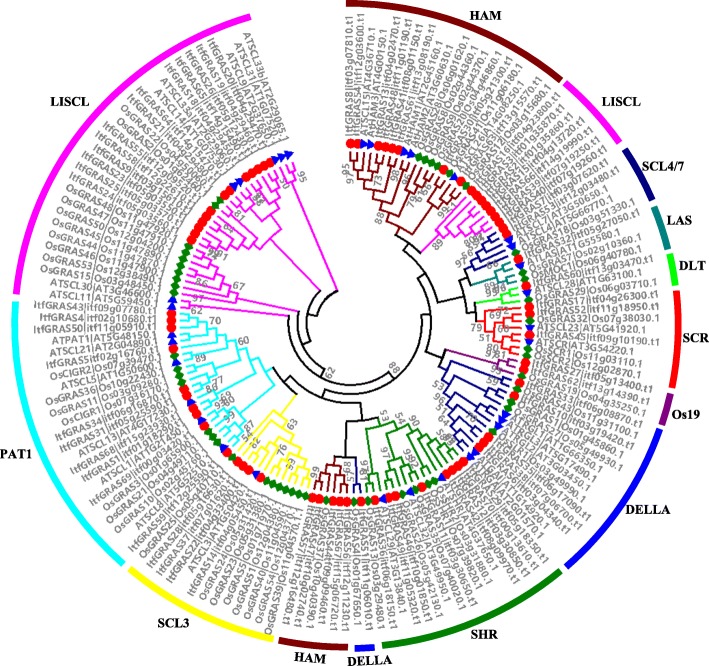

Evolutionary relationships of GRAS genes among three species

To investigate the GRAS protein evolutionary relationship between I. trifida and the other known species, we constructed a phylogenetic tree containing 70 GRAS proteins from I. trifida, 50 GRAS proteins from Oryza sativa and 33 proteins from Arabidopsis (Additional file 3: Table S2). Figure 2 showed us that the ItfGRAS proteins were classified into 11 subfamilies, namely, HAM, DELLA, SCL3, DLT, SCR, LAS, SCL4/7, SHR, PAT1, Os19 and LISCL according to the previous classification of GRAS families. The GRAS genes were very unevenly distributed in different subfamilies. For example, the LISCL subfamily containing 37 GRAS members formed the largest subfamily, including 20 I. trifida GRAS genes, seven Arabidopsis GRAS genes, and 10 rice GRAS genes, whereas the LAS, Os19 and SCL4/7 subfamilies were the relatively small subfamilies, and most of them contained only 3–5 GRAS members. Notably, only one GRAS gene in the DLT subfamily was found in those three species. The number of ItfGRAS genes was approximately 10 in the HAM, SHR and PAT1 subfamilies, whereas four and six were found in the SCL3 and DELLA subfamilies, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of GRAS proteins in Arabidopsis, Oryza sativa L and I. trifida. A phylogenetic tree of all the identified GRAS proteins among three species was constructed using MEGA 7.0 by the Maximum-Likelihood method analysis with 1000 bootstrap replications. The tree was classified into 11 different subfamilies indicated by different colored branches and outer rings. The red solid circles indicate the I. trifida GRAS proteins, the green solid diamonds represent the Arabidopsis GRAS proteins, and the blue solid triangles represent the O. sativa GRAS proteins. The bootstrap values > 50% are shown

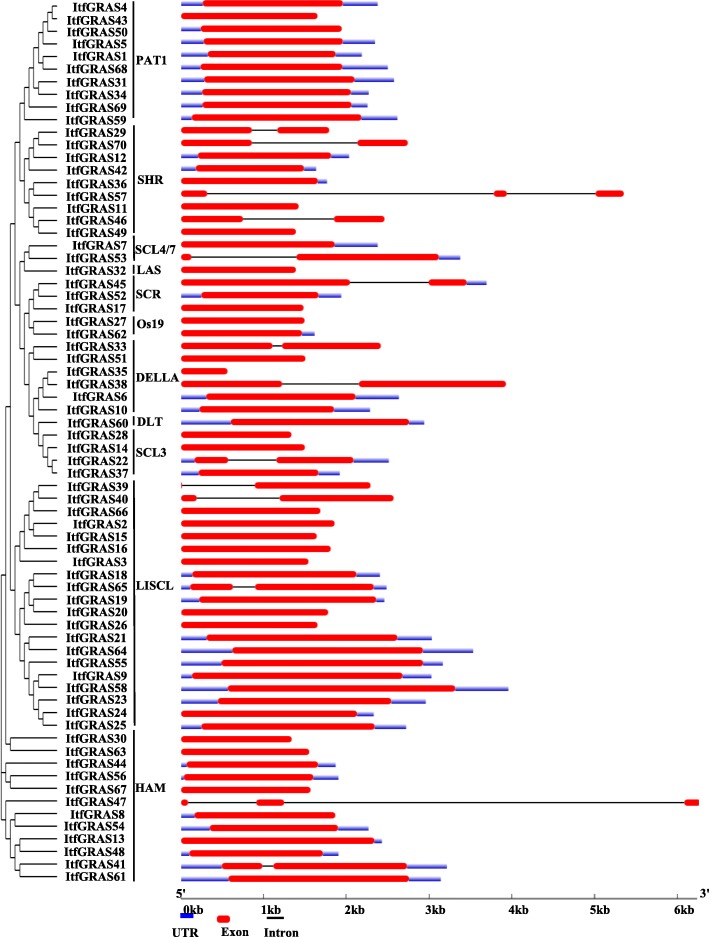

Gene structure analyses

To evaluate the likely diversity of GRAS transcription factors, we conducted an exon/intron analysis based on the sequence alignment between coding sequences and genomic sequences for each I. trifida GRAS gene (Fig. 3). Results showed that nearly 56 (80%) ItfGRAS transcription factors were intronless, which was consistent with previous reports, and only 14 of the 70 I. trifida GRAS genes had 1–2 introns. Among the genes, 12 contained just one intron, and two genes (ItfGRAS47 and ItfGRAS57) had two introns. Furthermore, the majority of GRAS genes in the same clade generally presented similar gene structures. Nevertheless, some GRAS transcription factors had exceptions in the same clade but with different gene structure, such as ItfGRAS46 and ItfGRAS57 in the clade SHR, and ItfGRAS7 and ItfGRAS53 in the clade SCL4/7.

Fig. 3.

Gene structure of GRAS members in I. trifida. The phylogenetic tree of ItfGRAS genes is shown on the left, which was divided into 11 clusters, including PAT1, SHR, SCL4/7, LAS, SCR, Os19, DELLA, DLT, SCL3, LISCL and HAM. Schematic diagram of exon/intron structure was displayed by the gene structure display server (GSDS) (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/). The exons, introns and UTR are represented by red solid boxes, black lines and blue boxes, respectively

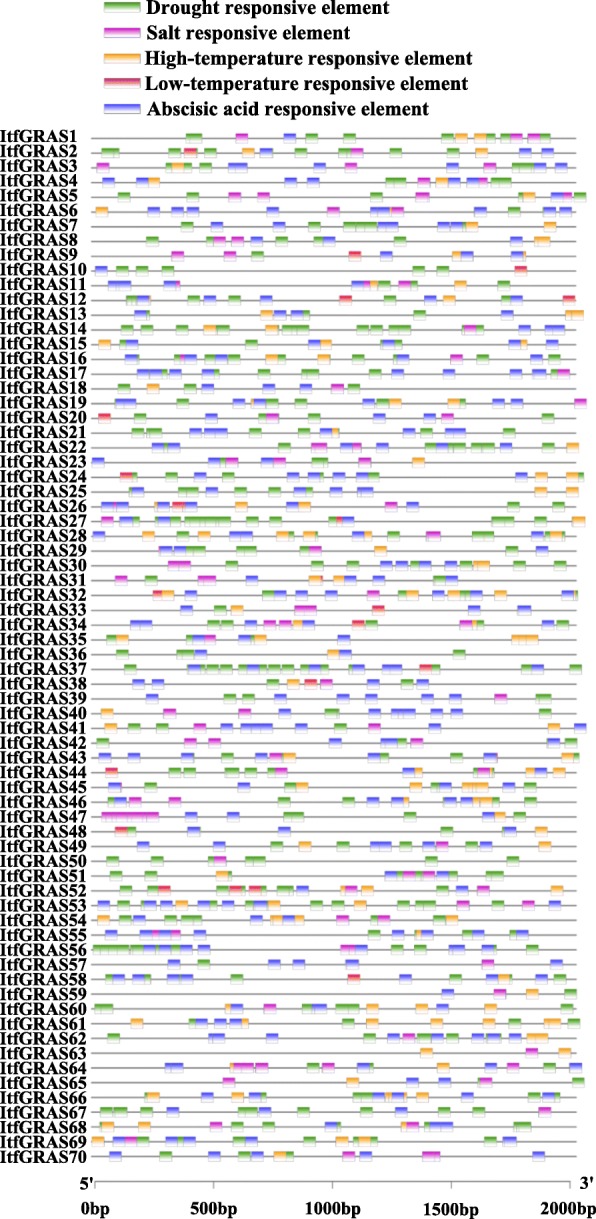

Stress-related cis-elements in ItfGRAS promoters

In order to further investigate the potential regulatory mechanisms of the ItfGRASs under abiotic stress, we obtained 2 kb upstream sequences from the translation initiation site of ItfGRASs and analyzed the cis-elements using online tool PlantCARE. Figure 4 showed all predicted different cis-elements in the promoter regions of ItfGRAS. The results showed that different cis-elements participated in various abiotic stresses and hormone responses (Additional file 4: Table S3). ItfGRASs excpect ItfGRAS63, contained more than one drought responsive elements (MBS, TC-rich repeats, MYB, DRE), indicating that they were involved in drought stress response (Fig. 4). Most ItfGRASs (85.7%) contained STRE element, which were associated with high-temperature stress response. About a quarter of these genes have LTR cis-element, implying that they might respond to cold stress. 27% of genes, such as ItfGRAS1, ItfGRAS9, and ItfGRAS20, etc., contained GT1-motif elements which were involved in salt stress response. In addition, the cis-acting regulatory element MYC found in 97.1% of ItfGRASs is related with drought early response and abscisic acid induction. And the drought as well as salt response element DRE was found in 18.6% of ItfGRSs, suggesting that these ItfGRASs may respond to both drought and salt stresses.

Fig. 4.

Predicted cis-elements in ItfGRAS promoters. Promoter sequences (− 2 kb) of 70 ItfGRAS genes are analyzed by PlantCARE. Rectangles with different colors indicate that different cis-elements participating in various abiotic stress regulation. Green, pink, orange and red bars indicate drought, salt, low- and high-temperaure responsive elements, respectively. And blue bar represents abscisic acid responsive element

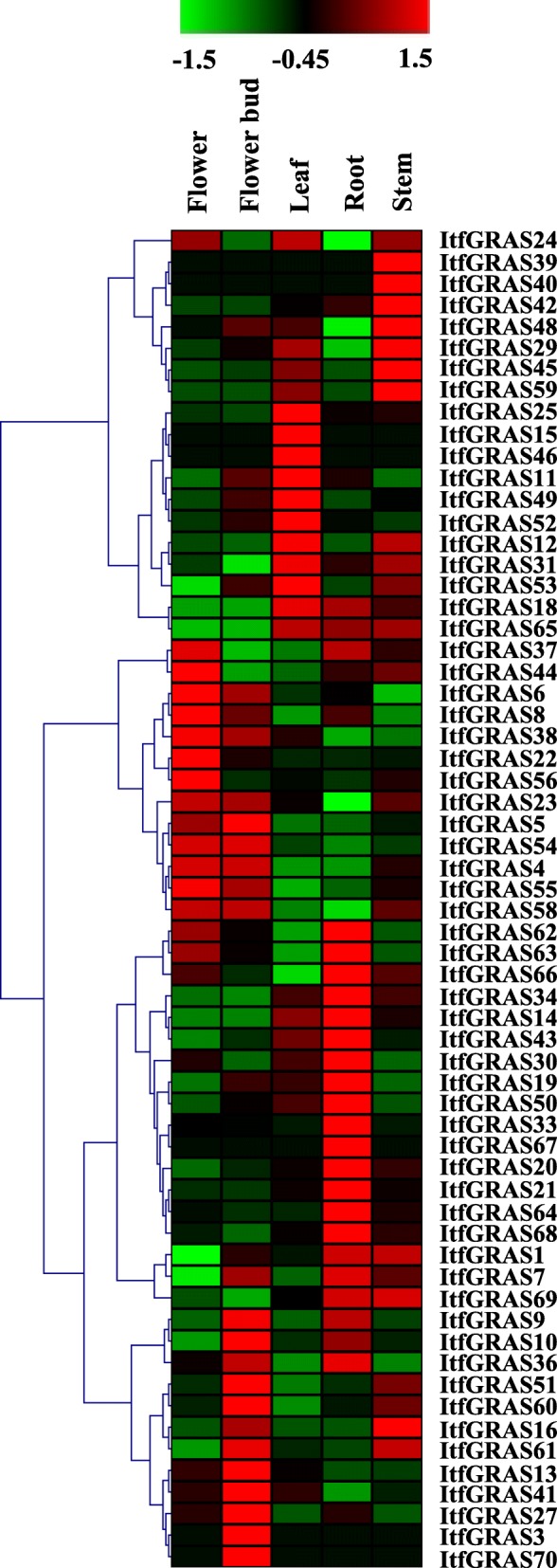

Expression profile of ItfGRAS among various tissues

Increasing evidence of the key role of GRAS genes in plant development are available. To investigate the biological functions of GRAS genes during different developmental stages, we analysed the transcript levels of GRAS genes in different tissues from the root, stem, leaf, flower and flower bud by using public data. A heatmap was generated, which exhibited the expression pattern of ItfGRAS transcription factors among five tissues based on the FPKM values normalized by Z-score (Fig. 5 and Additional file 5: Table S4). Among the ItfGRAS genes detected from RNA-seq, 14 (22.3%) GRAS genes had relatively higher levels across five tissues, whereas 15 (24.2%) GRAS genes were expressed at very low levels among these tissues. Nevertheless, some GRAS transcripts exhibited tissue-specific. For instance, ItfGRAS7 and ItfGRAS43 had a low expression in flower relative to those detected in the other tissues. Four GRAS genes (ItfGRAS12, ItfGRAS45 and ItfGRAS59) were expressed at higher levels in the leaf and stem than in the other tissues, except that ItfGRAS12 had no change in the flower. In addition, 28 (45.2%) and 34 (54.8%) GRAS genes were relatively highly expressed in the root and stem, respectively. Results suggested that the functions of ItfGRAS genes greatly changed in different tissues.

Fig. 5.

Expression profile of ItfGRAS genes among different tissues using RNA-seq. The FPKM values normalized by Z-score are used to measure the expression levels of ItfGRAS transcription factors among various tissues. These tissues include the root, stem, flower, flower bud and leaf. The coloured scale varying from green to red indicates relatively low or high expression. The values of these GRAS genes are listed in Additional file 5: Table S4

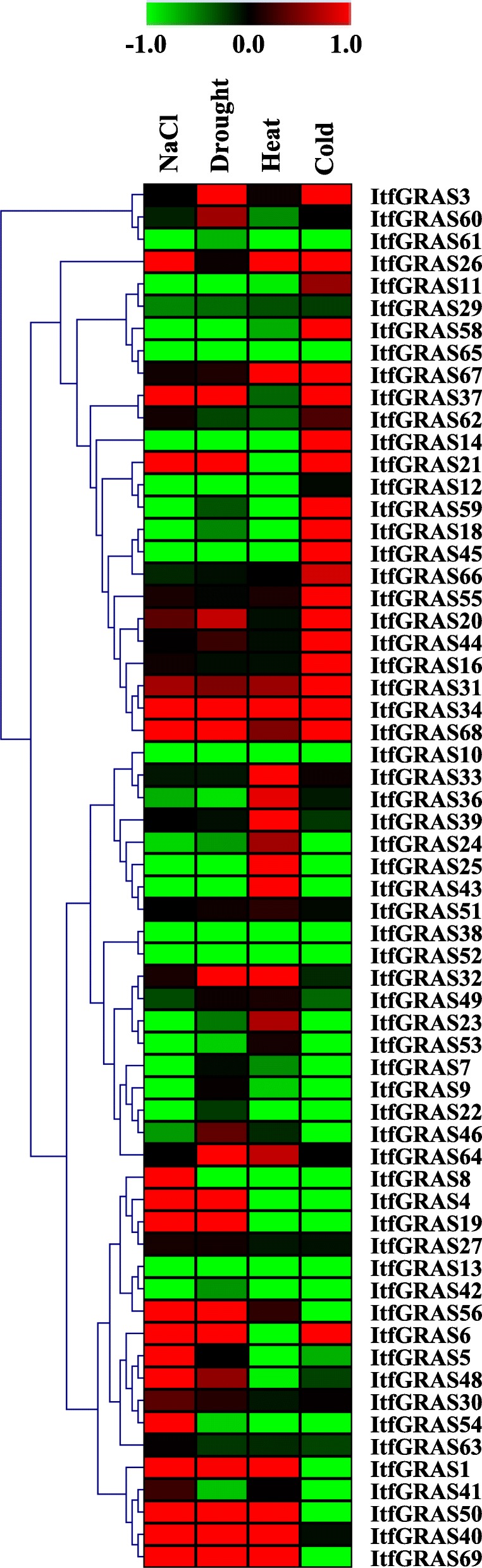

Responses of ItfGRAS genes to different stress treatments

To survey the possible role of ItfGRAS transcription factors during stress responses, we constructed the heatmap to show the expression profiles of ItfGRAS under various stress conditions (Fig. 6). Under four abiotic stresses, more than 15 ItfGRAS genes were expressed at relatively high levels, and the number of genes up-regulated in drought stress reached 20. Figure 6 shows that three genes (ItfGRAS31, ItfGRAS34 and ItfGRAS68) were all highly expressed under four abiotic stresses. In addition, some GRAS genes with high expression levels were found under three abiotic stresses but with low expression under another stress. For instance, ItfGRAS1, ItfGRAS50, ItfGRAS56 and ItfGRAS69 were significantly up-regulated under salt, drought and heat stresses but were down-regulated under cold stress. ItfGRAS6, ItfGRAS20, ItfGRAS21 and ItfGRAS37 were significantly up-regulated during drought, salt and cold stresses but were down-regulated under heat stress treatment. Some transcripts were certainly up-regulated under one stress condition but were down-regulated under other the three stress conditions (ItfGRAS8, ItfGRAS11, ItfGRAS23, ItfGRAS24, ItfGRAS25, ItfGRAS36, ItfGRAS43, ItfGRAS46, ItfGRAS54 and ItfGRAS58).

Fig. 6.

Expression analysis of ItfGRAS gene transcript levels under abiotic stresses. FPKM values were used to measure the expression levels of ItfGRAS genes in Drought, NaCl, Cold and Heat treatments. Green and red scales indicate relatively low or high expression, respectively. The FPKM values of abiotic stresses for GRAS genes are listed in Additional file 6: Table S5

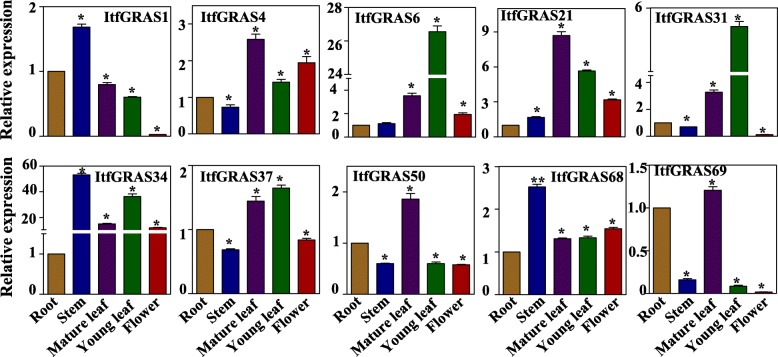

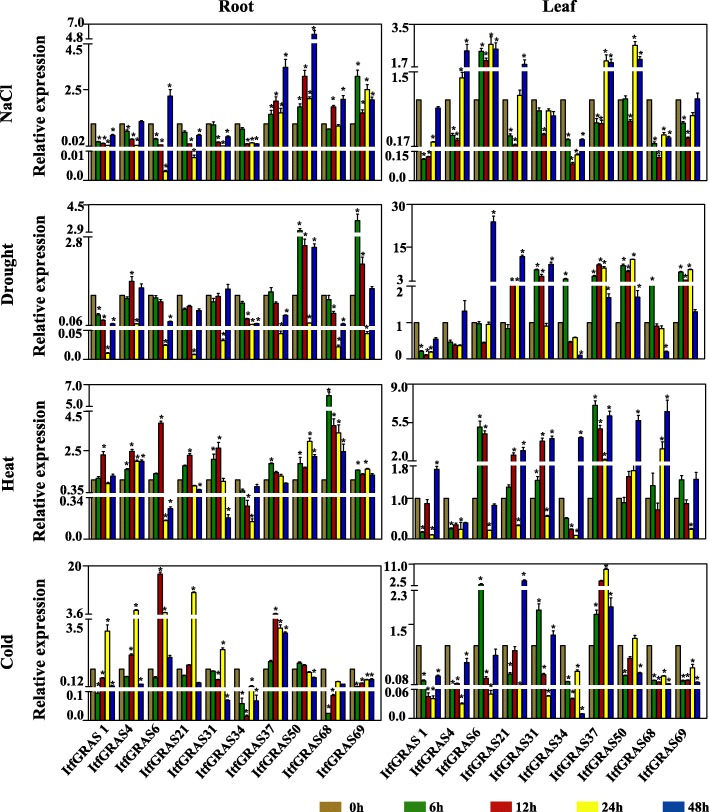

Confirmation of transcriptome data by qRT-PCR in different tissues and under various abiotic stress conditions

To further confirm the validity of transcriptome data, we conducted qRT-PCR to check expression pattern of 10 ItfGRAS genes (ItfGRAS1, ItfGRAS4, ItfGRAS6, ItfGRAS21, ItfGRAS31, ItfGRAS34, ItfGRAS37, ItfGRAS50, ItfGRAS68 and ItfGRAS69). We designed primers for these 10 selected genes (Additional file 7: Table S6) and firstly investigated their expression profiles among different tissues (root, stem, mature leaf, young leaf and flower). Some of the qRT-PCR results were not consistent with RNA-seq data, which may cause by the false positive effect of transcriptome. However, the results show that ItfGRAS6, ItfGRAS34, ItfGRAS37 and ItfGRAS68 exhibited a relatively high level across these tissues (Fig. 7). The expression levels for GRAS genes vary widely among different tissues. For instance, ItfGRAS21 and ItfGRAS50 were expressed at low levels in flower but were highly expressed in other three tissues, except that ItfGRAS50 was low in stem. ItfGRAS1 and ItfGRAS31 were weakly expressed in the flower but were highly expressed in other tissues. ItfGRAS69 showed relatively higher expression levels in root and mature leaf than in the other tissues. Finally, the expression levels of the selected four genes (ItfGRAS6, ItfGRAS21, ItfGRAS31 and ItfGRAS34) among these tissues were all higher than those of the other genes.

Fig. 7.

Tissue-specific expression patterns of 10 selected ItfGRAS genes by real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis. The y-axis stands for the relative expression of ItfGRAS genes. The x-axis represents different tissues including the root, stem, flower, mature leaf (ML), and young leaf (YL). The expression level is relative to root sample (1). GAPDH was used as an interval control, and standard errors (bar) stand for standard deviations for three replicates. The asterisk indicates that the expression level between other tissues and root is significantly different from the control values (P < 0.05)

In addition to the analysis of tissue specific expression pattern, the gene responses to abiotic stresses were also checked by qRT-PCR. We analysed the transcription levels of 10 selected ItfGRAS genes under salt, drought, cold and heat stress (Fig. 8). Under salt stress treatment, five genes (ItfGRAS6, ItfGRAS37, ItfGRAS50, ItfGRAS68 and ItfGRAS69) were significantly up-regulated in the root, while another ItfGRAS4 expression was slightly higher at 0 h. In the remaining genes, four genes (ItfGRAS1, ItfGRAS21, ItfGRAS31 and ItfGRAS34) were clearly down-regulated in the root. The expression of genes in leaves was basically the same as that in the roots under salt stress, except for the up-regulated expression of ItfGRAS21 and down-regulated expression of ItfGRAS68 and the substantially unchanged expression level of ItfGRAS69 compared with that at 0 h. For drought stress in the root, the expression of four GRAS members (ItfGRAS4, ItfGRAS31, ItfGRAS50 and ItfGRAS69) were up-regulated and that of the other six genes were obviously down-regulated with the lowest expression level at 24 h. Three other significantly up-regulated genes, namely ItfGRAS6, ItfGRAS21 and ItfGRAS37, were found in the leaf compared with drought stress in root. After heat treatment, five genes were up-regulated in the root, among which, ItfGRAS4, ItfGRAS50 and ItfGRAS68 exhibited an obvious increase. The rest of the genes (ItfGRAS6, ItfGRAS21, ItfGRAS31, ItfGRAS34 and ItfGRAS37) were down-regulated, including ItfGRAS21, ItfGRAS31 and ItfGRAS37 that had the lowest expression levels at 48 h. The expression levels of almost all genes were up-regulated in the leaf with the highest expression levels at 48 h. Only two genes, ItfGRAS4 and ItfGRAS6, were down-regulated in the leaf. Under cold treatment, most genes were down-regulated either in the root or leaf. Among which, the expression levels of four genes (ItfGRAS1, ItfGRAS4, ItfGRAS21 and ItfGRAS31) in the root increased at 24 h but decreased sharply at 48 h. Three genes (ItfGRAS1, ItfGRAS4 and ItfGRAS6) had the lowest expression levels at 24 h in the leaf, and the remaining genes (ItfGRAS34, ItfGRAS50, ItfGRAS68 and ItfGRAS69) showed the lowest expression levels at 48 h. In addition, two genes (ItfGRAS6 and ItfGRAS37 in root; ItfGRAS21 and ItfGRAS37 in leaf) were markedly up-regulated under cold stress, whereas the expression level of another gene, ItfGRAS31, was only relatively high in the leaf.

Fig. 8.

Relative expression levels of 10 selected ItfGRAS genes under abiotic stresses by qRT-PCR. The gene expression patterns of root and leaf of I. trifida plant were analysed at five time points (0, 6, 12, 24, 48 h) under four stress conditions (cold, heat, drought, and salt). The expression level at 0 h as control was normalised to 1. The expression level of control samples was relative to root sample (1). The error bars show the standard error with three biological replicates. The asterisk indicates a significant change of expression level between the other time period and control at p < 0.05

Discussion

The GRAS family is an important plant-specific transcriptional regulator that plays essential roles in regulating plant growth, development and stress responses. In recent years, with the rapid development of bioinformatics analysis, reports on the whole-genome identification of GRAS transcription factors in plants increased. So far, the characteristics of GRAS transcription factors in I. trifida remain unclear. Thus, we performed a comprehensive analysis of GRAS transcription factors in I. trifida genome, including their phylogenetic relationships, chromosome distribution and gene structure. We also analysed tissue-specific expression patterns and expression profiles in response to stresses.

In this investigation, 70 GRAS transcription factors in I. trifida were identified in total, which is higher than the number of A. thaliana (33) [4], Jatropha curcas (48) [29], P. mume (46) [9] and Chinese cabbage (46) [7] but lower than that in other species such as maize (86) [30] and Populus euphratica (106) [10]. The number of GRAS genes in I. trifida is larger, probably because its genome (462.0 Mb) is greater than those of A. thaliana (125.0 Mb), P. mume (280.0 Mb), and Brassica rapa (283.3 Mb). ItfGRAS genes were unevenly distributed on the 15 chromosomes of I. trifida with the most members (10) on chr4 and chr5 and relatively few members (2) on chr2, chr8, chr10 and chr15. Functions are more similar among diverse species when the proteins have high sequence similarities [31]. Phylogenetic analysis of GRAS proteins in I. trifida, Arabidopsis and rice was carried out to construct a phylogenetic tree with 11 major branches. Among these subfamilies, some I. trifida GRAS proteins are located in the same clade with that of Arabidopsis or rice, suggesting their similar functions among different species.

The overall pattern of intron position plays vital roles in the evolution of transcription factor families [32]. Most ItfGRAS genes lack introns (Fig. 3) similar to those in some species such as Arabidopsis, Medicago truncatula, P. mume, tomato and Populus [4, 7–9, 33]. These results suggested a close evolutionary relationship among GRAS proteins. Intronless genes are also found in the F-box transcription factor gene family [34] and DEAD box RNA helicase [35]. In addition, most GRAS members have similar exon–intron structure, indicating that the structures of GRAS genes are highly conserved.

The expression patterns of GRAS transcription factors differed across various tissues, consistent with those reported in other species such as tomato [8] and grapevine [36]. DELLA genes act as the major signalling hub for regulating plant growth and development processes [13, 37]. The three genes (ItfGRAS6, ItfGRAS10 and ItfGRAS38) of the DELLA subfamily were also highly expressed in multiple tissues, indicating their important roles in controlling various growth and development processes. ItfGRAS60 belonging to the DLT subfamily has a relatively higher expression in the bud than the other tissues, suggesting the function of this gene in bud development. All ItfGRAS genes in the PAT1 subfamily were highly expressed in the leaf except ItfGRAS4 and ItfGRAS5; this condition may be related to AtPAT1, AtSCL13 and AtSCL21 (the close evolutionary relationships to ItfGRAS genes in this subfamily) that are involved in phytochrome signal transduction [38].

GRAS members are related to regulating their biochemical activities in response to abiotic stresses [39]. Here, most ItfGRAS genes were influenced by various stress conditions, except that ItfGRAS3, ItfGRAS26 and ItfGRAS40 had no significant change under four abiotic stresses. We also analysed the expression of the selected ItfGRAS genes under four abiotic stresses with qRT-PCR, which was similar to the result of RNA-seq data. However, the expression levels of several genes from qRT-PCR showed opposite results compared with the public data. For instance, ItfGRAS34 was expressed at low levels in salt, drought and cold treatments in the qRT-PCR results, but public data showed their high expression under these stresses. DELLA protein plays an important role in regulating plant stress tolerance [40]. One of DELLA members, ItfGRAS6,was up-regulated under the salt, drought and cold treatments but was down-regulated under heat condition. By contrast, another DELLA member ItfGRAS51 was only up-regulated under heat treatment. In addition, Park et al. (2013) proved the significant up-regulation of BoGRAS gene during heat stress condition in Brassica oleracea [41]. All ItfGRAS members in the PAT1 subfamily were highly expressed under at least one abiotic stress. Among which, four members (ItfGRAS31, ItfGRAS34, ItfGRAS68 and ItfGRAS69) showed response to four abiotic stresses, suggesting their vital roles in response to adversity stresses, which is consistent with the report on VaPAT1 [42]. Overall, I. trifida GRAS genes have potential regulatory roles in plant development and response to adverse environmental stresses.

Conclusions

In this study, we identified 70 GRAS genes from I. trifida which is the closest relative of sweet potato. These GRAS genes were distributed on 15 chromosomes and divided into 11 subfamilies. The most genes lack introns and presented similar intron-exon structures, suggesting that the structures of GRAS gene were highly conserved. The stress-related cis-element analysis, RNA-Seq data and qRT-PCR results indicated the potential functions of ItfGRASs during plant development and stress responses. Our findings will further facilitate the functional study of GRAS genes and molecular breeding of sweet potato.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Multiple sequence alignment of 70 ItfGRAS genes. The most conserved motif of VHIID is underlined with a black solid line. (PPT 1462 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1. Detailed information of the ItfGRAS. (XLS 29 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S2. Arabidopsis and rice GRAS genes used for phylogenetic analysis. (XLS 26 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S3. Cis-elements associated with abiotic stresses within the ItfGRAS gene promoters.

Additional file 5: Table S4. The expression data of the ItfGRAS genes in various tissues. (XLS 32 kb)

Additional file 6: Table S5. The expression data of the GRAS genes under four abiotic stress conditions in I.trifida. (XLS 33 kb)

Additional file 7: Table S6. Gene-specific primers used for qRT-PCR analysis of the ItfGRAS genes. (XLS 20 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank the GT4SP project team for sharing the Ipomoea trifida genome annotation data (http://sweetpotato.plantbiology.msu.edu/).

Abbreviations

- AA

Amino acid

- FPKM

fragments per kilobase million

- GSDS

Gene structure display server

- MW

Molecular weights

- NJ

Neighbour-joining

- pI

Isoelectric points

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SMART

Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool

Authors’ contributions

TX and ZL conceived and designed this experiment. YC and PZ carried out the experiments and analyzed the data. SW, YL and JS helped to analyze the data. YC and PZ wrote the manuscript. TX and QC revised the manuscript. QC offered the plant material. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported jointly by the projects of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31701481), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (19KJA510010), Jiangsu Overseas Visiting Scholar Program for University Prominent Young & Middle-aged Teachers and Presidents, the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD), the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-10-B03) and National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFD1000705, 2018YFD1000700). These funding bodies supported this research from inception to completion; ie, the design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and the writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yao Chen and Panpan Zhu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yao Chen, Email: cytjghaohao@163.com.

Panpan Zhu, Email: zhupanpan311@126.com.

Shaoyuan Wu, Email: shaoyuanwu@outlook.com.

Yan Lu, Email: luyan306@126.com.

Jian Sun, Email: sunjian@jsnu.edu.cn.

Qinghe Cao, Email: cqhe75@yahoo.com.

Zongyun Li, Email: zongyunli@jsnu.edu.cn.

Tao Xu, Email: xutao_yr@126.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12864-019-6316-7.

References

- 1.Pysh LD, Wysocka-Diller JW, Camilleri C, Bouchez D, Benfey PN. The GRAS gene family in arabidopsis: sequence characterization and basic expression analysis of the SCARECROW-LIKE genes. Plant J. 2010;18(1):111–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolle C. The role of GRAS proteins in plant signal transduction and development. Planta. 2004;218(5):683–692. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1203-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun X, Xue B, Jones WT, Rikkerink E, Dunker AK, Uversky VN. A functionally required unfoldome from the plant kingdom: intrinsically disordered N-terminal domains of GRAS proteins are involved in molecular recognition during plant development. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;77(3):205–223. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9803-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian C, Wan P, Sun S, Li J, Chen M. Genome-wide analysis of the GRAS gene family in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;54(4):519–532. doi: 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000038256.89809.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch S, Oldroyd GED. GRAS-domain transcription factors that regulate plant development. Plant Signal Behav. 2009;4(8):698–700. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.8.9176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Zhao Y, Xiao H, Zheng Y, Yue B. Genome-wide identification, evolution, and expression analysis of RNA-binding glycine-rich protein family in maize. J Integr Plant Biol. 2014;56(10):1020–1031. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song X, Liu T, Duan W, Ma Q, Ren J, Wang Z, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the GRAS gene family in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis) Genomics. 2014;103(1):135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang W, Xian Z, Kang X, Tang N, Li Z. Genome-wide identification, phylogeny and expression analysis of GRAS gene family in tomato. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15(1):209. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0590-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu J, Wang T, Xu Z, Sun L, Zhang Q. Genome-wide analysis of the GRAS gene family in Prunus mume. Mol Gen Genomics. 2015;290(1):303–317. doi: 10.1007/s00438-014-0918-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X, Widmer A. Genome-wide comparative analysis of the GRAS gene family in populus, Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2014;32(6):1129–1145. doi: 10.1007/s11105-014-0721-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayrose M, Ekengren SK, Melech-Bonfil S, Martin GB, Sessa G. A novel link between tomato GRAS genes, plant disease resistance and mechanical stress response. Mol Plant Pathol. 2006;7(6):593–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2006.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morohashi K, Minami M, Takase H, Hotta Y, Hiratsuka K. Isolation and characterization of a novel GRAS gene that regulates meiosis-associated gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(23):20865–20873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301712200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolle C. Chapter 19-functional aspects of GRAS family proteins. Plant Transcr Factors. 2016;19:295–311. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800854-6.00019-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu K, Chen S, Li T, Ma X, Liu X, Luo L, et al. OsGRAS23, a rice GRAS transcription factor gene, is involved in drought stress response through regulating expression of stress-responsive genes. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15(1):141. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0532-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma H, Liang D, Shuai P, Xia X, Yin W. The salt- and drought-inducible poplar GRAS protein SCL7 confers salt and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot. 2010;61(14):4011–4019. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang M, Yang Q, Fu T, Zhou Y. Overexpression of the Brassica napus BnLAS gene in Arabidopsis affects plant development and increases drought tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 2011;30(3):373–388. doi: 10.1007/s00299-010-0940-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Achard P, Gong F, Cheminant S, Alioua M, Hedden P, Genschik P. The cold-inducible CBF1 factor-dependent signaling pathway modulates the accumulation of the growth-repressing DELLA proteins via its effect on gibberellin metabolism. Plant Cell. 2008;20(8):2117–2129. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang C, Gao X, Liao L, Harberd NP, Fu X. Phosphate starvation root architecture and anthocyanin accumulation responses are modulated by the gibberellin- DELLA signaling pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;145(4):1460–1470. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.103788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czikkel BE, Maxwell DP. NtGRAS1, a novel stress-induced member of the GRAS family in tobacco, localizes to the nucleus. J Plant Physiol. 2007;164(9):1220–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Q. Improvement for agronomically important traits by gene engineering in sweet potato. Breed Sci. 2017;67(1):15–26. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.16126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munoz-Rodriguez P, Carruthers T, Wood JRI, Williams BRM, Weitemier K, Kronmiller B, et al. Reconciling conflicting phylogenies in the origin of sweet potato and dispersal to Polynesia. Curr Biol. 2018;28(8):1246–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roullier C, Duputié A, Wennekes P, Benoit L, Bringas VMF, Rossel G, et al. Disentangling the origins of cultivated sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) lam.) PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e62707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu Y, Sun J, Yang Z, Zhao C, Zhu M, Ma D, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of glycine-rich RNA-binding protein family in sweet potato wild relative Ipomoea trifida. Gene. 2019;686:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo A, Zhu Q, Chen X, Luo J. GSDS: a gene structure display server. Hereditas. 2007;29(8):1023–1026. doi: 10.1360/yc-007-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA 7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lescot M, Déhais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, Rouzé P, et al. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elementsand a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saeed AI, Sharov V, White J, Li J, Liang W, Bhagabati N, et al. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 2003;34(2):374–378. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2DDCt method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Z, Wu P, Chen Y, Li M, Wu G, Jiang H. Genome-wide analysis of the GRAS gene family in physic nut (Jatropha curcas L.) Genet Mol Res. 2015;14(4):19211–19224. doi: 10.4238/2015.December.29.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo Y, We H, Li X, Li Q, Zhao X, Duan X, et al. Identification and expression of GRAS family genes in maize (Zea mays L.) PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0185418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen F, Mackey AJ, Vermunt JK, Roos DS. Assessing performance of orthology detection strategies applied to eukaryotic genomes. PLoS One. 2007;2(4):e383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bai Y, Meng Y, Huang D, Qi Y, Chen M. Origin and evolutionary analysis of the plant-specific TIFY transcription factor family. Genomics. 2011;98(2):128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang H, Cao Y, Shang C, Lie J, Wang J, Wu Z, et al. Genome-wide characterization of GRAS family genes in Medicago truncatula reveals their evolutionary dynamics and functional diversification. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0185439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jain M, Nijhawan A, Arora R, Agarwal P, Ray S, Sharma P, et al. F-box proteins in rice. Genome-wide analysis, classification, temporal and spatial gene expression during panicle and seed development, and regulation by light and abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. 2007;143(4):1467–1483. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.091900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aubourg S, Kreis M, Lecharny A. The DEAD box RNA helicase family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(2):628–636. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grimplet J, Agudelo-Romero P, Teixeira RT, Martinez-Zapater JM, Fortes AM. Structural and functional analysis of the GRAS gene family in grapevine indicates a role of GRAS proteins in the control of development and stress responses. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:353. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wild M, Daviere JM, Cheminant S, Regnault T, Baumberger N, Heintz D, et al. The Arabidopsis DELLA RGA-LIKE3 is a direct target of MYC2 and modulates jasmonate signaling responses. Plant Cell. 2012;24(8):3307–3319. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.101428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bolle C, Koncz C, Chua NH. PAT1, a new member of the GRAS family, is involved in phytochrome a signal transduction. Genes Dev. 2000;14(10):1269–1278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niu Y, Zhao T, Xu X, Li J. Genome-wide identification and characterization of GRAS transcription factors in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) PeerJ. 2017;5:e3955. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Achard P, Genschik P. Releasing the brakes of plant growth: how GAs shutdown DELLA proteins. J Exp Bot. 2009;60(4):1085–1092. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park HJ, Jung WY, Lee SS, Song J, Kwon SY, Kim H, et al. Use of heat stress responsive gene expression levels for early selection of heat tolerant cabbage (Brassica oleracea L.) Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(6):11871–11894. doi: 10.3390/ijms140611871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuan Y, Fang L, Karungo SK, Zhang L, Gao Y, Li S, et al. Overexpression of VaPAT1, a GRAS transcription factor from Vitis amurensis, confers abiotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2016;35(3):655–666. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1910-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Multiple sequence alignment of 70 ItfGRAS genes. The most conserved motif of VHIID is underlined with a black solid line. (PPT 1462 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1. Detailed information of the ItfGRAS. (XLS 29 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S2. Arabidopsis and rice GRAS genes used for phylogenetic analysis. (XLS 26 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S3. Cis-elements associated with abiotic stresses within the ItfGRAS gene promoters.

Additional file 5: Table S4. The expression data of the ItfGRAS genes in various tissues. (XLS 32 kb)

Additional file 6: Table S5. The expression data of the GRAS genes under four abiotic stress conditions in I.trifida. (XLS 33 kb)

Additional file 7: Table S6. Gene-specific primers used for qRT-PCR analysis of the ItfGRAS genes. (XLS 20 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.