Abstract

Background

To better understand the process of osteoarthritic degenerative meniscal lesions (DMLs) formation, this study analyzed the dataset GSE52042 using bioinformatics methods to identify the pivotal genes and pathways related to osteoarthritic DMLs.

Material/Methods

The GSE52042 dataset, comprising diseased meniscus samples and healthier meniscus samples, was downloaded and the differentially-expressed genes (DEGs) were extracted. The reactome pathways assessment and functional analysis were performed using the “ClusterProfiler” package and “ReactomePA” package of Bioconductor. The protein–protein interaction network was constructed, followed by the extraction of hub genes and modules.

Results

A set of 154 common DEGs, including 64 upregulated DEGs and 90 downregulated DEGs, were obtained. GO analysis suggested that the DEGs primarily participated in positive regulation of the mitotic cell cycle and extracellular matrix organization. Reactome pathway analysis showed that the DEGs were predominantly enriched in TP53, which regulates transcription of genes involved in G2 cell cycle arrest and extracellular matrix organization. The top 10 hub genes were TYMS, AURKA, CENPN, NUSAP1, CENPM, TPX2, CDK1, UBE2C, BIRC5, and CCNB1. The genes in the 2 modules were primarily associated with M Phase and keratan sulfate degradation.

Conclusions

A series of pivotal genes and reactome pathways were identified elucidate the molecular mechanisms involved in the formation of osteoarthritic DMLs and to discover potential therapeutic targets.

MeSH Keywords: Gene Expression Profiling; Menisci, Tibial; Molecular Biology

Background

The meniscus is an important structure of the knee, playing a pivotal role in shock absorption, joint lubrication and nutrition, proprioception, load transmission, joint congruity, and stability [1]. A meniscus lesion, predisposing to knee osteoarthritis (OA), is a frequent knee joint injury with high incidence rate, found in 60% of patients with asymptomatic osteoarthritis [2–4]. There is a high interdependency between degenerative meniscal lesions (DMLs) and knee OA [5,6]. DMLs can be a feature of knee OA and are conducive to joint space narrowing [7–9]. The best treatment of DMLs is still debated. Although arthroscopic surgery is still widely performed in the management of DMLs [10], guidelines and research recommend against surgery due to the non-superiority of arthroscopic surgery over non-operative treatment [11–13]. Biological therapies such as platelet-rich plasma intrameniscal injection may be promising treatments for DMLs [14]. Therefore, better understanding of biological properties and molecular mechanisms in progression of DMLs may promote development of more effective therapeutic strategies.

Recently, microarray technology, which is an effective and high-throughput molecular technique for simultaneously analyzing expression of multiple genes, has been pervasively used in a range of research areas to discover the differentially-expressed genes within molecular mechanisms, distinct pathways, and protein–protein interactions (PPI), and to reveal connections between disease and genes [15–20]. Sun et al. detected many differentially-expressed genes (DEGs) between osteoarthritic meniscal cells and normal meniscal cells [21]. Brophy et al. found the transcripts and biological processes in OA menisci were different from non-OA menisci [22]. Rai et al. revealed a correlation of body mass index to gene expression in ruptured menisci and a biologic association between obesity and knee osteoarthritis [23]. Microarray analysis combined with bioinformatics provides a novel and effective method to investigate the comprehensive molecular mechanisms in meniscus injuries [24], and may be useful to improve understanding of the connections between DEGs and DMLs.

To explore the molecular mechanisms of DMLs in OA patients, the present study aimed to identify the key DEGs and functional pathways in OA DMLs by use of comprehensive bioinformatics methods. As OA menisci have unique biological properties, we reanalyzed the gene expression profile of GSE52042, which identified the DEGs between diseased or severe degenerative tear OA menisci and healthier OA menisci. Subsequently, extensive bioinformatics analysis was carried out for gene ontology (GO) analysis, reactome pathways identification, PPI network screening, and modules extraction. The results of this work may provide further insights into the pathogenesis of OA DMLs at the molecular level and help explore potential biotherapeutic targets for it. To the best of our knowledge, there is no previously published bioinformatics analysis of this database.

Material and Methods

Microarray data

The GSE52042 dataset in Gene Expression Omnibus (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) was downloaded for subsequent analysis. GSE52042 was based on GPL17882 platform (Human MI ReadyArray™ 49K Human Genomic Array; Microarrays, Inc., Huntsville, AL, USA), including 4 diseased meniscus samples with thoroughly degraded surfaces and 4 healthier meniscus samples with integrated surfaces, which were obtained from late-stage of knee OA.

Identification of DEGs in diseased and healthier samples

The DEGs between diseased and healthier samples were screened by GEO2R (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/). P value <0.05 and log fold change (FC) <−1.0 or log FC >1.0 were defined as the cutoff criteria. A volcano plot and a heatmap were constructed using R software (version 3.6.0).

Functional and reactome pathway analysis of DEGs

GO enrichment analysis was carried out by the “ClusterProfiler” package of Bioconductor [25] to assess the potential functions of DEGs in molecular function (MF), cellular component (CC), and biological process (BP). Overrepresented enriched reactome pathways were searched for using the “ReactomePA” package of Bioconductor [26] to identify pathways that were strongly related to DEGs. The P value <0.05 and false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05 were set as the cutoff for criteria.

Construction of PPI network and modules analysis

All DEGs were uploaded to STRING (version 11.0; http://string-db.org/) to evaluate the PPI interactive relationships among DEGs. Confidence score >0.4 was defined as the cutoff criterion. Subsequently, the PPI network was visualized using Cytoscape software (version 3.6.1; www.cytoscape.org). The cytoHubba plugin (version 0.1) [27] was used to extract the hub genes. Then, the modules were extracted using the Molecular Complex Detection plugin (version 1.5.1) according to the criteria: Degree Cutoff=10, Max. Depth=100, K-Core=2, Mode Score Cutoff=0.2, and MCODE score ≥4 [28].

Results

Identification of DEGs

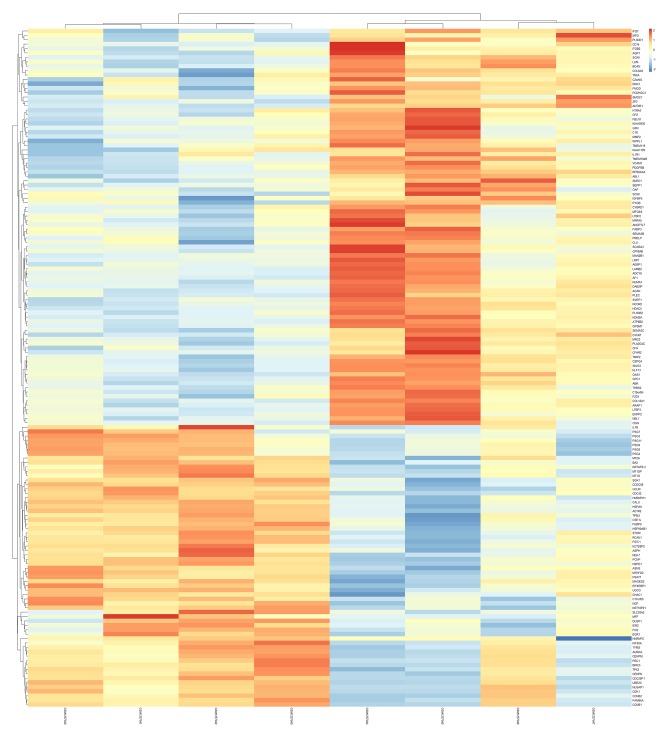

In comparing diseased samples to healthier samples, a total of 154 DEGs including 64 upregulated and 90 downregulated genes were identified from the GSE52042 dataset. The top 10 upregulated and downregulated DEGs are shown in Table 1. The heatmap and volcano plot for total DEGs are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

The top 10 upregulated and downregulated DEGs.

| Gene symbol | logFC | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Downregulated | FMOD | −2.396 | 0.000533 |

| MXRA5 | −2.255 | 0.021918 | |

| VCAM1 | −1.923 | 0.000582 | |

| LRP1 | −1.922 | 0.011987 | |

| CFH | −1.879 | 0.002062 | |

| TIMP2 | −1.878 | 5.67E-05 | |

| OAS1 | −1.844 | 0.000157 | |

| CSPG4 | −1.835 | 0.000205 | |

| LTBP3 | −1.804 | 0.002253 | |

| THBS2 | −1.726 | 0.007495 | |

| Upregulated | PSG9 | 2.081 | 0.003259 |

| PSG4 | 1.927 | 0.003893 | |

| PSG11 | 1.836 | 0.004486 | |

| FSTL1 | 1.776 | 0.001282 | |

| PSG8 | 1.774 | 0.000716 | |

| EGR1 | 1.739 | 9.56E-05 | |

| FOS | 1.732 | 0.000996 | |

| NEK7 | 1.728 | 0.015207 | |

| ACTR2 | 1.683 | 0.004529 | |

| KRT18P21 | 1.608 | 7.42E-06 |

Figure 1.

Heat map plot of total DEGs.

Figure 2.

Volcano plot of total DEGs.

GO terms enrichment analysis

In terms of BP, the upregulated DEGs were primarily participated in female pregnancy, positive regulation of cell cycle, multi-multicellular organism process, positive regulation of mitotic cell cycle, and chromosome segregation, and the downregulated DEGs were chiefly enriched in extracellular matrix (ECM) organization, extracellular structure organization, glycosaminoglycan catabolic process, aminoglycan catabolic process, and keratan sulfate catabolic process.

In terms of CC, the upregulated DEGs were mostly enriched in spindle, midbody, spindle pole, mitotic spindle, and condensed chromosome kinetochore, and the downregulated DEGs were predominantly enriched in collagen-containing extracellular matrix, extracellular matrix, lysosomal lumen, vacuolar lumen, and Golgi lumen.

In terms of MF, the upregulated DEGs were predominantly enriched in ubiquitin-like protein ligase binding. The downregulated DEGs were chiefly involved in extracellular matrix structural constituent, extracellular matrix structural constituent conferring compression resistance, growth factor binding, collagen binding, and glycosaminoglycan binding.

The top 5 BP, CC, and MF enrichment analyses of the DEGs are displayed in Table 2. The bubble charts of the DEGs are shown in Figures 3 and 4, which exhibit the overview of GO terms (the top 5 BP, CC, and MF enrichment analyses). The chord diagrams of the DEGs are illustrated in Figures 5 and 6, which display the relationship between DEGs and GO terms (the top 5 BP, CC, and MF enrichment analyses).

Table 2.

The top 5 BP, CC, and MF enrichment analyses of the upregulated and downregulated DEGs.

| Ontology | GO ID | Description | Count | Gene ratio | P value | Adjust p value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downregulated | |||||||

| BP | GO: 0030198 | Extracellular matrix organization | 18 | 0.22 | 9.33E-15 | 2.08E-11 | 1.57E-11 |

| BP | GO: 0043062 | Extracellular structure organization | 18 | 0.22 | 1.18E-13 | 1.31E-10 | 9.87E-11 |

| BP | GO: 0006027 | Glycosaminoglycan catabolic process | 8 | 0.10 | 3.29E-10 | 2.39E-07 | 1.80E-07 |

| BP | GO: 0006026 | Aminoglycan catabolic process | 8 | 0.10 | 4.29E-10 | 2.39E-07 | 1.80E-07 |

| BP | GO: 0042340 | Keratan sulfate catabolic process | 5 | 0.06 | 1.37E-09 | 4.85E-07 | 3.66E-07 |

| CC | GO: 0062023 | Collagen-containing extracellular matrix | 24 | 0.30 | 1.59E-21 | 2.83E-19 | 2.17E-19 |

| CC | GO: 0031012 | Extracellular matrix | 24 | 0.30 | 6.65E-20 | 5.92E-18 | 4.55E-18 |

| CC | GO: 0043202 | Lysosomal lumen | 10 | 0.13 | 6.91E-12 | 4.10E-10 | 3.15E-10 |

| CC | GO: 0005775 | Vacuolar lumen | 11 | 0.14 | 1.45E-10 | 6.43E-09 | 4.95E-09 |

| CC | GO: 0005796 | Golgi lumen | 8 | 0.10 | 1.13E-08 | 4.04E-07 | 3.10E-07 |

| MF | GO: 0005201 | Extracellular matrix structural constituent | 15 | 0.19 | 6.88E-16 | 1.64E-13 | 1.36E-13 |

| MF | GO: 0030021 | Extracellular matrix structural constituent conferring compression resistance | 5 | 0.06 | 3.94E-08 | 4.68E-06 | 3.89E-06 |

| MF | GO: 0019838 | Growth factor binding | 7 | 0.09 | 1.63E-06 | 0.000129 | 0.000107 |

| MF | GO: 0005518 | Collagen binding | 4 | 0.05 | 0.000195 | 0.011595 | 0.009641 |

| MF | GO: 0005539 | Glycosaminoglycan binding | 6 | 0.08 | 0.000353 | 0.016785 | 0.013956 |

| Upregulated | |||||||

| BP | GO: 0007565 | Female pregnancy | 8 | 0.14 | 1.43E-07 | 0.000172 | 0.000127 |

| BP | GO: 0045787 | Positive regulation of cell cycle | 10 | 0.18 | 2.06E-07 | 0.000172 | 0.000127 |

| BP | GO: 0044706 | Multi-multicellular organism process | 8 | 0.14 | 4.63E-07 | 0.000206 | 0.000151 |

| BP | GO: 0045931 | Positive regulation of mitotic cell cycle | 7 | 0.13 | 4.93E-07 | 0.000206 | 0.000151 |

| BP | GO: 0007059 | Chromosome segregation | 8 | 0.14 | 2.09E-06 | 0.000699 | 0.000513 |

| CC | GO: 0005819 | Spindle | 8 | 0.14 | 7.09E-06 | 0.001305 | 0.001105 |

| CC | GO: 0030496 | Midbody | 6 | 0.10 | 1.47E-05 | 0.001354 | 0.001146 |

| CC | GO: 0000922 | Spindle pole | 5 | 0.09 | 0.000108 | 0.006634 | 0.005617 |

| CC | GO: 0072686 | Mitotic spindle | 4 | 0.07 | 0.000234 | 0.009674 | 0.008191 |

| CC | GO: 0000777 | Condensed chromosome kinetochore | 4 | 0.07 | 0.000263 | 0.009674 | 0.008191 |

| MF | GO: 0044389 | Ubiquitin-like protein ligase binding | 6 | 0.12 | 0.000207 | 0.038328 | 0.031622 |

Figure 3.

Bubble chart of upregulated DEGs.

Figure 4.

Bubble chart of downregulated DEGs.

Figure 5.

Chord diagram of upregulated DEGs.

Figure 6.

Chord diagram of downregulated DEGs.

Reactome pathway analysis

The upregulated DEGs were chiefly enriched in TP53, which regulates transcription of genes involved in G2 cell cycle arrest, condensation of prometaphase chromosomes, nuclear pore complex (NPC) disassembly, resolution of sister chromatid cohesion, and Golgi cisternae pericentriolar stack reorganization, and the downregulated DEGs were predominantly enriched in diseases associated with glycosaminoglycan metabolism, extracellular matrix organization, keratan sulfate degradation, diseases of glycosylation, and keratan sulfate biosynthesis. Table 3 lists the top 10 reactome pathways of the DEGs.

Table 3.

The top 10 significantly enriched reactome pathways of the upregulated and downregulated DEGs.

| Reactome ID | Description | Count | P value | FDR | Gene symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downregulated | |||||

| R-HSA-3560782 | Diseases associated with glycosaminoglycan metabolism | 8 | 6.07E-11 | 1.10E-08 | FMOD, CSPG4, ACAN, LUM, PRELP, GPC1, OGN, BCAN |

| R-HSA-1474244 | Extracellular matrix organization | 15 | 9.43E-11 | 1.10E-08 | FMOD, VCAM1, TIMP2, LTBP3, ITGB2, COL8A2, ACAN, FBLN1, LUM, PLEC, LAMB2, COL12A1, BCAN, MMP2, LTBP2 |

| R-HSA-2022857 | Keratan sulfate degradation | 5 | 6.58E-09 | 5.10E-07 | FMOD, ACAN, LUM, PRELP, OGN |

| R-HSA-3781865 | Diseases of glycosylation | 9 | 1.08E-07 | 6.29E-06 | FMOD, CSPG4, THBS2, ACAN, LUM, PRELP, GPC1, OGN, BCAN |

| R-HSA-2022854 | Keratan sulfate biosynthesis | 5 | 4.70E-07 | 1.87E-05 | FMOD, ACAN, LUM, PRELP, OGN |

| R-HSA-1630316 | Glycosaminoglycan metabolism | 8 | 4.83E-07 | 1.87E-05 | FMOD, CSPG4, ACAN, LUM, PRELP, GPC1, OGN, BCAN |

| R-HSA-1638074 | Keratan sulfate/keratin metabolism | 5 | 1.30E-06 | 4.31E-05 | FMOD, ACAN, LUM, PRELP, OGN |

| R-HSA-71387 | Metabolism of carbohydrates | 10 | 6.05E-06 | 0.000176 | FMOD, CSPG4, ACAN, LUM, PRELP, GPC1, OGN, BCAN, PYGB, MAN2B1 |

| R-HSA-3000178 | ECM proteoglycans | 5 | 7.15E-05 | 0.001849 | FMOD, ACAN, LUM, LAMB2, BCAN |

| R-HSA-1474228 | Degradation of the extracellular matrix | 6 | 0.000144 | 0.003091 | TIMP2, COL8A2, ACAN, COL12A1, BCAN, MMP2 |

| Upregulated | |||||

| R-HSA-6804114 | TP53 regulates transcription of genes involved in G2 cell cycle arrest | 4 | 1.37E-06 | 0.000294 | AURKA, CDK1, BAX, CCNB1 |

| R-HSA-2514853 | Condensation of prometaphase chromosomes | 3 | 1.68E-05 | 0.001539 | CDK1, CCNB2, CCNB1 |

| R-HSA-3301854 | Nuclear pore complex (NPC) disassembly | 4 | 2.21E-05 | 0.001539 | CDK1, CCNB2, CCNB1, NEK7 |

| R-HSA-2500257 | Resolution of sister chromatid cohesion | 6 | 2.88E-05 | 0.001539 | CDK1, CENPM, CCNB2, CENPN, CCNB1, BIRC5 |

| R-HSA-162658 | Golgi cisternae pericentriolar stack reorganization | 3 | 3.66E-05 | 0.001564 | CDK1, CCNB2, CCNB1 |

| R-HSA-202733 | Cell surface interactions at the vascular wall | 6 | 4.62E-05 | 0.001645 | PSG7, PSG3, PSG8, PSG11, PSG4, PSG9 |

| R-HSA-6791312 | TP53 regulates transcription of cell cycle genes | 4 | 8.53E-05 | 0.002274 | AURKA, CDK1, BAX, CCNB1 |

| R-HSA-68886 | M phase | 9 | 9.46E-05 | 0.002274 | CDK1, CENPM, KIF20A, CCNB2, CENPN, UBE2C, CCNB1, BIRC5, NEK7 |

| R-HSA-176412 | Phosphorylation of the APC/C | 3 | 9.58E-05 | 0.002274 | CDK1, UBE2C, CCNB1 |

| R-HSA-2980766 | Nuclear envelope breakdown | 4 | 0.000108 | 0.002303 | CDK1, CCNB2, CCNB1, NEK7 |

Construction of PPI network and modules analysis

The PPI network was screened, comprising 124 nodes and 355 edges (Figure 7). The top 10 hub genes were identified by cytoHubba plugin using the Maximal Clique Centrality (MCC) method, including TYMS, AURKA, CENPN, NUSAP1, CENPM, TPX2, CDK1, UBE2C, BIRC5, and CCNB1 (Table 4, Figure 8). Among these genes, CDK1 and CCNB1 showed the highest node degree. Then, 2 eligible modules of the gene interaction network were screened using the Molecular Complex Detection plugin (Figure 9). Module 1, consisting of 14 nodes and 91 edges, had 14 scores, while module 2, including 4 nodes and 6 edges, had 4 scores. Reactome pathways analysis revealed that genes in module 1 were primarily associated with M Phase, Resolution of Sister Chromatid Cohesion, Cell Cycle Checkpoints, Mitotic Prometaphase, and Condensation of Prometaphase Chromosomes, while in module 2 they were keratan sulfate degradation, keratan sulfate biosynthesis, keratan sulfate/keratin metabolism, diseases associated with glycosaminoglycan metabolism, and extracellular matrix organization. The top 10 reactome pathways of these modules are listed in Table 5.

Figure 7.

PPI network of DEGs.

Table 4.

The top 10 hub genes.

| Gene symbol | Degree | MCC |

|---|---|---|

| CDK1 | 21 | 6.23E+09 |

| CCNB1 | 21 | 6.23E+09 |

| AURKA | 18 | 6.23E+09 |

| TPX2 | 15 | 6.23E+09 |

| UBE2C | 15 | 6.23E+09 |

| CENPM | 14 | 6.23E+09 |

| CENPN | 14 | 6.23E+09 |

| NUSAP1 | 14 | 6.23E+09 |

| BIRC5 | 14 | 6.23E+09 |

| TYMS | 14 | 6.23E+09 |

Figure 8.

The top 10 hub genes.

Figure 9.

(A, B) Two modules.

Table 5.

The top 10 significantly enriched reactome pathways of module 1 and 2.

| Reactome ID | Description | Count | P value | FDR | Gene symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Module 1 | |||||

| R-HSA-68886 | M Phase | 8 | 1.48E-09 | 4.09E-08 | CDK1, UBE2C, CCNB1, CCNB2, BIRC5, KIF20A, CENPN, CENPM |

| R-HSA-2500257 | Resolution of sister chromatid cohesion | 6 | 2.16E-09 | 4.09E-08 | CDK1, CCNB1, CCNB2, BIRC5, CENPN, CENPM |

| R-HSA-69620 | Cell cycle checkpoints | 7 | 7.98E-09 | 1.01E-07 | CDK1, UBE2C, CCNB1, CCNB2, BIRC5, CENPN, CENPM |

| R-HSA-68877 | Mitotic prometaphase | 6 | 3.48E-08 | 3.30E-07 | CDK1, CCNB1, CCNB2, BIRC5, CENPN, CENPM |

| R-HSA-2514853 | Condensation of prometaphase chromosomes | 3 | 1.81E-07 | 1.37E-06 | CDK1, CCNB1, CCNB2 |

| R-HSA-162658 | Golgi cisternae pericentriolar stack reorganization | 3 | 3.99E-07 | 2.52E-06 | CDK1, CCNB1, CCNB2 |

| R-HSA-6804114 | TP53 regulates transcription of genes involved in G2 cell cycle arrest | 3 | 8.91E-07 | 4.82E-06 | CDK1, CCNB1, AURKA |

| R-HSA-176412 | Phosphorylation of the APC/C | 3 | 1.06E-06 | 5.01E-06 | CDK1, UBE2C, CCNB1 |

| R-HSA-69275 | G2/M transition | 5 | 1.45E-06 | 5.61E-06 | CDK1, CCNB1, CCNB2, AURKA, TPX2 |

| R-HSA-453274 | Mitotic G2-G2/M phases | 5 | 1.53E-06 | 5.61E-06 | CDK1, CCNB1, CCNB2, AURKA, TPX2 |

| Module 2 | |||||

| R-HSA-2022857 | Keratan sulfate degradation | 3 | 5.73E-09 | 1.81E-08 | ACAN, FMOD, LUM |

| R-HSA-2022854 | Keratan sulfate biosynthesis | 3 | 6.56E-08 | 1.04E-07 | ACAN, FMOD, LUM |

| R-HSA-1638074 | Keratan sulfate/keratin metabolism | 3 | 1.20E-07 | 1.26E-07 | ACAN, FMOD, LUM |

| R-HSA-3560782 | Diseases associated with glycosaminoglycan metabolism | 3 | 2.13E-07 | 1.68E-07 | ACAN, FMOD, LUM |

| R-HSA-1474244 | Extracellular matrix organization | 4 | 6.33E-07 | 4.00E-07 | ACAN, FMOD, MMP2, LUM |

| R-HSA-3000178 | ECM proteoglycans | 3 | 1.40E-06 | 7.38E-07 | ACAN, FMOD, LUM |

| R-HSA-1630316 | Glycosaminoglycan metabolism | 3 | 6.16E-06 | 2.78E-06 | ACAN, FMOD, LUM |

| R-HSA-3781865 | Diseases of glycosylation | 3 | 9.47E-06 | 3.74E-06 | ACAN, FMOD, LUM |

| R-HSA-71387 | Metabolism of carbohydrates | 3 | 8.32E-05 | 2.92E-05 | ACAN, FMOD, LUM |

| R-HSA-1474228 | Degradation of the extracellular matrix | 2 | 0.001018 | 0.0003214 | ACAN, MMP2 |

Discussion

OA is a disease involving the whole joint, and DMLs plays a critical role in the process of knee OA [7–9,29–31]. However, the treatment of DMLs remains a conundrum. Meniscectomy has no benefit over non-operative treatments, while non-operative measures such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, exercise therapy, and rest are the mainstay of management for DMLs [32]. Therefore, better understanding of the underlying pathogenesis of DMLs is of pivotal importance for identification of therapeutic targets and may drive future studies to search for biological treatments of this disease. The high-throughput microarray technology combined with bioinformatics analysis has been widely used in various diseases to predict potential molecular therapeutic targets. In the present study, the microarray dataset GSE52042, comprising healthier and diseased meniscus samples, was obtained, and a bioinformatics analysis was completed. A total of 154 DEGs were identified, including 64 upregulated and 90 downregulated DEGs. Furthermore, in order to probe into the biological significances behind these DEGs, GO, Reactome pathway, and PPI analysis were performed.

In view of the results of GO terms enrichment analysis, we linked the downregulated DEGs with ECM organization, collagen-containing ECM, and ECM structural constituent, and observed the upregulated DEGs had a close relationship with positive regulation of mitotic cell cycle, spindle, and ubiquitin-like protein ligase binding. The meniscus ECM, which plays a crucial role in sustaining structural integrity and mechanical properties of meniscus, is primarily composed of water, collagen, proteoglycan, glycoprotein, elastin, and linking protein [33,34]. Histopathological analysis showed that degenerated menisci could result in a loss of ECM structure [35]. Herwig et al. demonstrated that the collagen and glycosaminoglycan contents (chondroitin 4-sulphate, dermatan sulphate, and keratan sulphate) declined with increasing meniscus degeneration [36]. Meniscus cells are composed by different cell types, which possess proliferation ability and hasten meniscus repair [37–41]. Positive regulation of mitotic cell cycle can result in cell proliferation [42]. Nishida et al. observed fibroblasts and fibrochondrocyte-like cells proliferated but glycosaminoglycans and the cell count decreased remarkably after experimental dog meniscus tearing, indicating that ECM disorder and cell proliferation could coexist in the degenerative meniscus tear [43]. Lopez-Franco et al. showed that decreased proteoglycan, cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, and cell population altered the ECM organization in degenerative menisci, and actively dividing cells were found in all recently injured menisci samples and in 1 degenerative menisci sample [44].

The downregulated DEGs reactome pathways were predominantly involved in diseases associated with glycosaminoglycan metabolism, extracellular matrix organization, keratan sulfate degradation, diseases of glycosylation, and keratan sulfate biosynthesis. These results indicated the disorder of ECM was present in DMLs. Reactome pathway analysis of the upregulated DEGs were predominantly enriched in TP53, which regulates transcription of genes involved in G2 cell cycle arrest, condensation of prometaphase chromosomes, nuclear pore complex (NPC) disassembly, resolution of sister chromatid cohesion, and Golgi cisternae pericentriolar stack reorganization, and these were related to cell proliferation, consistent with the results of GO terms enrichment analysis of upregulated DEGs.

The PPI network was screened to predict the connections of protein functions of DEGs, and the top 10 hub genes – TYMS, AURKA, CENPN, NUSAP1, CENPM, TPX2, CDK1, UBE2C, BIRC5, and CCNB1 – were presented. Some hub genes are closely associated with osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1), a highly conserved small protein, is a member of the cyclin-dependent kinase family that serves as a serine/threonine kinase and the catalytic subunit of mitosis-phase promoting factor, playing a pivotal role in controlling cell cycle, such as mitotic onset and driving G2-M transition [45–49]. CDK1 was detected in human and rat osteoarthritic chondrocytes [50]. Saito et al. demonstrated that overexpression of CDK1 could cause chondrocyte proliferation, and its low expression could result in chondrocyte differentiation and maturity, indicating CDK1 was essential for chondrocytes proliferation and differentiation [51]. Cyclin B1 (CCNB1) is one of cell cycle proteins which are essential regulators of cell division, and complexes with CDK1 to form a mitosis-phase-promoting factor that promotes mitosis [46,47]. Zhou et al. found that platelets could upregulate the proliferation of rat osteoarthritic chondrocytes via stimulation of the ERK/CDK1/CCNB1 pathway [52]. Baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis repeat-containing 5 (BIRC5), also called survivin, is a protein that belongs to the inhibitor of apoptosis family, which localizes to the spindle, expressed in the G2/M phase, and plays a key role in the regulation of mitosis and protection of cells from apoptosis [53,54]. BIRC5 was detected in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes, and its suppression expression can lead to reduced rates of chondrocyte proliferation and G2/M blockade [55]. Aurora kinase A (AURKA) is a type of Aurora kinase and is crucial for the successful execution of mitosis [56]. AURKA was highly expressed in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes and overexpression of AURKA could contributes to the development of knee osteoarthritis [57]. In the present study, AURKA, CDK1, BIRC5, and CCNB1 were upregulated in diseased menisci compared to healthier menisci in late-stage knee OA, indicating diseased meniscus cells tended to cell proliferation.

Two modules were extracted from the PPI network. Most of the genes presented in module 1 are the aforementioned hub genes. The genes in module 2 relate to ECM metabolism. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP2) is a matrix metalloproteinase with ECM-degrading components [58]. Stone observed that late-stage OA meniscus cell cultures secreted more MMP2 than normal meniscus cell cultures when stimulated by pro-inflammatory factors [59]. Cook et al. found that when stimulated by interleukin-1β, MMP2 expression was decreased, but other matrix metalloproteinases were increased in canine meniscus cell cultures [60]. James et al. found that co-culture of meniscus and the infrapatellar fat pad, which is a major sources of pro-inflammatory factors, increased sulfated glycosaminoglycan degeneration but decreased MMP2 production [61]. In the present study, MMP2 was downregulated in diseased menisci compared to healthier menisci. Lumican (LUM) and fibromodulin (FMOD) are Class II small leucine-rich proteoglycans and are components of tendon and cartilage, with effects on collagen fibril structure and tissue stiffness [62,63]. Önnerfjord et al. found that LUM and FMOD were highly expressed in menisci, and the relative content between them in different tissues was negatively correlated [64]. Melrose et al. found that the expression of LUM and FMOD in menisci were consistent in late-stage knees OA versus age-matched normal knee joints [65]. Endo et al. observed that LUM was upregulated in menisci in early-phase knee OA [66]. Hellio observed that the FMOD expression was downregulated in the lateral meniscus at 3 weeks after anterior cruciate ligament transection for experimental OA in rabbits, but returned to normal at 8 weeks after surgery [67]. Aggrecan (ACAN) is a macromolecular proteoglycan and a crucial component of meniscus ECM, helping to maintain biomechanical properties of ECM [68–71]. Favero et al. found that OA meniscus and synovium could release inflammatory molecules to induce meniscus ACAN degradation and ECM loss [72]. Freymann et al. observed that human serum could stimulate meniscal cells obtained from advanced degenerative menisci in end-stage OA patients to express aggrecan [73]. In the present study, LUM, FMOD, and ACAN were downregulated in diseased menisci compared to healthier menisci in late-stage knee OA, indicating the ECM structure was impaired in diseased menisci.

According to the present results, some of the genes promoting cell proliferation were upregulated, while some of the genes constituting meniscus ECM were downregulated in the diseased meniscus samples, indicating that cell repair and ECM degradation may coexist in the process of osteoarthritic DMLs, which reflected the disorder of cell proliferation and the impairment of ECM integrality in osteoarthritic DMLs. Better understanding of these unique biological features may help develop potential therapies for osteoarthritic DMLs.

Conclusions

We conducted a comprehensive bioinformatics analysis on gene expression profile of OA meniscus. Key genes and pathways were identified to provide more detailed molecular mechanisms for the process of osteoarthritic DMLs and shed light on potential therapeutic targets. Nevertheless, further experiments are needed to further validate the identified genes and pathways.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

Source of support: The present study was supported by the Zhejiang Chinese Medicine Technology Project (grant no. 2018ZB140) and the Medical and Health Science and Technology Plan Project of Zhejiang Province (grant no. 2017KY725).

References

- 1.Fox AJ, Wanivenhaus F, Burge AJ, et al. The human meniscus: A review of anatomy, function, injury, and advances in treatment. Clin Anat. 2015;28:269–87. doi: 10.1002/ca.22456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Englund M, Guermazi A, Gale D, et al. Incidental meniscal findings on knee MRI in middle-aged and elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1108–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Englund M, Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS. Patient-relevant outcomes fourteen years after meniscectomy: Influence of type of meniscal tear and size of resection. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:631–39. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.6.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL, Roos EM. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: Osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1756–69. doi: 10.1177/0363546507307396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hellio LGM, Vignon E, Otterness IG, Hart DA. Early changes in lapine menisci during osteoarthritis development: Part I: Cellular and matrix alterations. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9:56–64. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Englund M, Roos EM, Lohmander LS. Impact of type of meniscal tear on radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: A sixteen-year followup of meniscectomy with matched controls. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2178–87. doi: 10.1002/art.11088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett LD, Buckland-Wright JC. Meniscal and articular cartilage changes in knee osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional double-contrast macroradiographic study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:917–23. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.8.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JY, Bin SI, Kim JM, et al. Tear gap and severity of osteoarthritis are associated with meniscal extrusion in degenerative medial meniscus posterior root tears. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019;105:1395–99. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2019.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunter DJ, Zhang YQ, Niu JB, et al. The association of meniscal pathologic changes with cartilage loss in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:795–801. doi: 10.1002/art.21724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rongen JJ, van Tienen TG, Buma P, Hannink G. Meniscus surgery is still widely performed in the treatment of degenerative meniscus tears in The Netherlands. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26:1123–29. doi: 10.1007/s00167-017-4473-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siemieniuk R, Harris IA, Agoritsas T, et al. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee arthritis and meniscal tears: A clinical practice guideline. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:313. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-j1982rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorlund JB. Deconstructing a popular myth: Why knee arthroscopy is no better than placebo surgery for degenerative meniscal tears. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:1630–31. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rongen JJ, Rovers MM, van Tienen TG, et al. Increased risk for knee replacement surgery after arthroscopic surgery for degenerative meniscal tears: A multi-center longitudinal observational study using data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaminski R, Maksymowicz-Wleklik M, Kulinski K, et al. Short-term outcomes of percutaneous trephination with a platelet rich plasma intrameniscal injection for the repair of degenerative meniscal lesions. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(4) doi: 10.3390/ijms20040856. pii: E856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li PC. Overview of microarray technology. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1368:3–4. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3136-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L, Cui Y, Fu F, et al. An insight into the key genes and biological functions associated with insulin resistance in adipose tissue with microarray technology. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:1963–67. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Wei B, Cao S, et al. Identification by microarray technology of key genes involved in the progression of carotid atherosclerotic plaque. Genes Genet Syst. 2014;89:253–58. doi: 10.1266/ggs.89.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Zheng T. Screening of hub genes and pathways in colorectal cancer with microarray technology. Pathol Oncol Res. 2014;20:611–18. doi: 10.1007/s12253-013-9739-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu K, Fu Q, Liu Y, Wang C. An integrative bioinformatics analysis of microarray data for identifying hub genes as diagnostic biomarkers of preeclampsia. Biosci Rep. 2019;39(9) doi: 10.1042/BSR20190187. pii: BSR20190187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng M, Liu J, Yang W, et al. Multiple-microarray analysis for identification of hub genes involved in tubulointerstial injury in diabetic nephropathy. J Cell Physiol. :2019. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28313. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun Y, Mauerhan DR, Honeycutt PR, et al. Analysis of meniscal degeneration and meniscal gene expression. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brophy RH, Zhang B, Cai L, et al. Transcriptome comparison of meniscus from patients with and without osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26:422–32. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rai MF, Patra D, Sandell LJ, Brophy RH. Relationship of gene expression in the injured human meniscus to body mass index: A biologic connection between obesity and osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2152–64. doi: 10.1002/art.38643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang P, Gu J, Wu J, et al. Microarray analysis of the molecular mechanisms associated with age and body mass index in human meniscal injury. Mol Med Rep. 2019;19:93–102. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16:284–87. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu G, He QY. ReactomePA: An R/Bioconductor package for reactome pathway analysis and visualization. Mol Biosyst. 2016;12:477–79. doi: 10.1039/c5mb00663e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chin CH, Chen SH, Wu HH, et al. cytoHubba: Identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol. 2014;8(Suppl 4):S11. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-8-S4-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bader GD, Hogue CW. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldring MB, Goldring SR. Osteoarthritis. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:626–34. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samuels J, Krasnokutsky S, Abramson SB. Osteoarthritis: A tale of three tissues. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2008;66:244–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun Y, Mauerhan DR, Honeycutt PR, et al. Calcium deposition in osteoarthritic meniscus and meniscal cell culture. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R56. doi: 10.1186/ar2968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matar HE, Duckett SP, Raut V. Degenerative meniscal tears of the knee: Evaluation and management. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2019;80:46–50. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2019.80.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez-Franco M, Gomez-Barrena E. Cellular and molecular meniscal changes in the degenerative knee: A review. J Exp Orthop. 2018;5:11. doi: 10.1186/s40634-018-0126-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen S, Fu P, Wu H, Pei M. Meniscus, articular cartilage and nucleus pulposus: A comparative review of cartilage-like tissues in anatomy, development and function. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;370:53–70. doi: 10.1007/s00441-017-2613-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pauli C, Grogan SP, Patil S, et al. Macroscopic and histopathologic analysis of human knee menisci in aging and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:1132–41. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herwig J, Egner E, Buddecke E. Chemical changes of human knee joint menisci in various stages of degeneration. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984;43:635–40. doi: 10.1136/ard.43.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verdonk PC, Forsyth RG, Wang J, et al. Characterisation of human knee meniscus cell phenotype. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:548–60. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakata K, Shino K, Hamada M, et al. Human meniscus cell: Characterization of the primary culture and use for tissue engineering. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(391 Suppl):S208–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melrose J, Smith S, Cake M, et al. Comparative spatial and temporal localisation of perlecan, aggrecan and type I, II and IV collagen in the ovine meniscus: An ageing study. Histochem Cell Biol. 2005;124:225–35. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hellio LGM, Ou Y, Schield-Yee T, et al. The cells of the rabbit meniscus: Their arrangement, interrelationship, morphological variations and cytoarchitecture. J Aant. 2001;198:525–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19850525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mauck RL, Martinez-Diaz GJ, Yuan X, Tuan RS. Regional multilineage differentiation potential of meniscal fibrochondrocytes: implications for meniscus repair. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2007;290:48–58. doi: 10.1002/ar.20419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Golias CH, Charalabopoulos A, Charalabopoulos K. Cell proliferation and cell cycle control: a mini review. Int J Clin Pract. 2004;58:1134–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishida M, Higuchi H, Kobayashi Y, Takagishi K. Histological and biochemical changes of experimental meniscus tear in the dog knee. J Orthop Sci. 2005;10:406–13. doi: 10.1007/s00776-005-0916-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lopez-Franco M, Lopez-Franco O, Murciano-Anton MA, et al. Meniscal degeneration in human knee osteoarthritis: In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136:175–83. doi: 10.1007/s00402-015-2378-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crncec A, Hochegger H. Triggering mitosis. FEBS Lett. 2019;593:2868–88. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strauss B, Harrison A, Coelho PA, et al. Cyclin B1 is essential for mitosis in mouse embryos, and its nuclear export sets the time for mitosis. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:179–93. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201612147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lim S, Kaldis P. Cdks, cyclins and CKIs: Roles beyond cell cycle regulation. Development. 2013;140:3079–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.091744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nigg EA. Mitotic kinases as regulators of cell division and its checkpoints. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:21–32. doi: 10.1038/35048096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Santamaria D, Barriere C, Cerqueira A, et al. Cdk1 is sufficient to drive the mammalian cell cycle. Nature. 2007;448:811–1. doi: 10.1038/nature06046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gomez-Camarillo MA, Kouri JB. Ontogeny of rat chondrocyte proliferation: Studies in embryo, adult and osteoarthritic (OA) cartilage. Cell Res. 2005;15:99–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saito M, Mulati M, Talib SZ, et al. The indispensable role of cyclin-dependent kinase 1 in skeletal development. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20622. doi: 10.1038/srep20622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou Q, Xu C, Cheng X, et al. Platelets promote cartilage repair and chondrocyte proliferation via ADP in a rodent model of osteoarthritis. Platelets. 2016;27:212–22. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2015.1075493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shojaei F, Yazdani-Nafchi F, Banitalebi-Dehkordi M, et al. Trace of survivin in cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2019;28:365–72. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sah NK, Khan Z, Khan GJ, Bisen PS. Structural, functional and therapeutic biology of survivin. Cancer Lett. 2006;244:164–71. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lechler P, Balakrishnan S, Schaumburger J, et al. The oncofetal gene survivin is re-expressed in osteoarthritis and is required for chondrocyte proliferation in vitro. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:150. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bertolin G, Tramier M. Insights into the non-mitotic functions of Aurora kinase A: More than just cell division. Cell Mol Life Sci. :2019. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03310-2. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang Q, Zhou Y, Cai P, et al. Up-regulated HIF-2alpha contributes to the Osteoarthritis development through mediating the primary cilia loss. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;75:105762. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Henriet P, Emonard H. Matrix metalloproteinase-2: Not (just) a “hero” of the past. Biochimie. 2019;166:223–32. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2019.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stone AV, Loeser RF, Vanderman KS, et al. Pro-inflammatory stimulation of meniscus cells increases production of matrix metalloproteinases and additional catabolic factors involved in osteoarthritis pathogenesis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22:264–74. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cook AE, Cook JL, Stoker AM. Metabolic responses of meniscus to IL-1beta. J Knee Surg. 2018;31:834–40. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1615821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nishimuta JF, Bendernagel MF, Levenston ME. Co-culture with infrapatellar fat pad differentially stimulates proteoglycan synthesis and accumulation in cartilage and meniscus tissues. Connect Tissue Res. 2017;58:447–55. doi: 10.1080/03008207.2016.1245728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. Proteoglycan form and function: A comprehensive nomenclature of proteoglycans. Matrix Biol. 2015;42:11–55. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chakravarti S. Functions of lumican and fibromodulin: Lessons from knockout mice. Glycoconj J. 2002;19:287–93. doi: 10.1023/A:1025348417078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Onnerfjord P, Khabut A, Reinholt FP, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of eight cartilaginous tissues reveals characteristic differences as well as similarities between subgroups. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:18913–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.298968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Melrose J, Fuller ES, Roughley PJ, et al. Fragmentation of decorin, biglycan, lumican and keratocan is elevated in degenerate human meniscus, knee and hip articular cartilages compared with age-matched macroscopically normal and control tissues. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:R79. doi: 10.1186/ar2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Endo J, Sasho T, Akagi R, et al. Comparative analysis of gene expression between cartilage and menisci in early-phase osteoarthritis of the knee – an animal model study. J Knee Surg. 2018;31:664–69. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hellio LGM, Vignon E, Otterness IG, Hart DA. Early changes in lapine menisci during osteoarthritis development: Part II: molecular alterations. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9:65–72. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hodax JK, Quintos JB, Gruppuso PA, et al. Aggrecan is required for chondrocyte differentiation in ATDC5 chondroprogenitor cells. PLoS One. 2019;14:e218399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kiani C, Chen L, Wu YJ, et al. Structure and function of aggrecan. Cell Res. 2002;12:19–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vanderploeg EJ, Wilson CG, Imler SM, et al. Regional variations in the distribution and colocalization of extracellular matrix proteins in the juvenile bovine meniscus. J Anat. 2012;221:174–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01523.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McAlinden A, Dudhia J, Bolton MC, et al. Age-related changes in the synthesis and mRNA expression of decorin and aggrecan in human meniscus and articular cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9:33–41. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Favero M, Belluzzi E, Trisolino G, et al. Inflammatory molecules produced by meniscus and synovium in early and end-stage osteoarthritis: A coculture study. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:11176–87. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Freymann U, Degrassi L, Kruger JP, et al. Effect of serum and platelet-rich plasma on human early or advanced degenerative meniscus cells. Connect Tissue Res. 2017;58:509–19. doi: 10.1080/03008207.2016.1260563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]